Submitted:

04 September 2025

Posted:

05 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

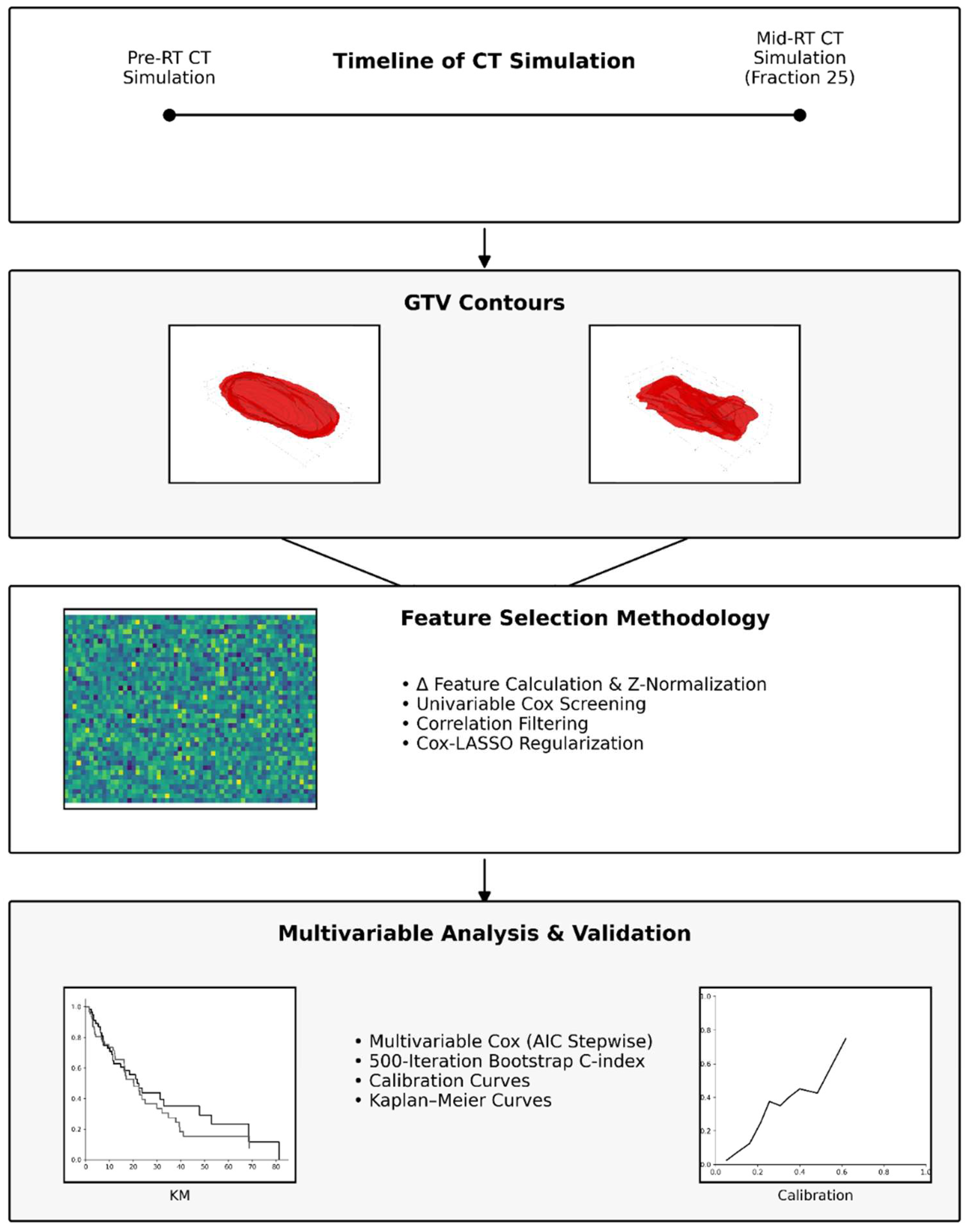

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Treatment, CT Acquisition Parameters and Segmentation

2.3. Radiomic Feature Extraction

2.4. DICOM Image and RT Structure Acquisition

2.5. ROI Mask Generation

2.6. Radiomic Feature Extraction

2.7. Calculation of Delta-Radiomics

2.8. Feature Selection for Survival Outcomes

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

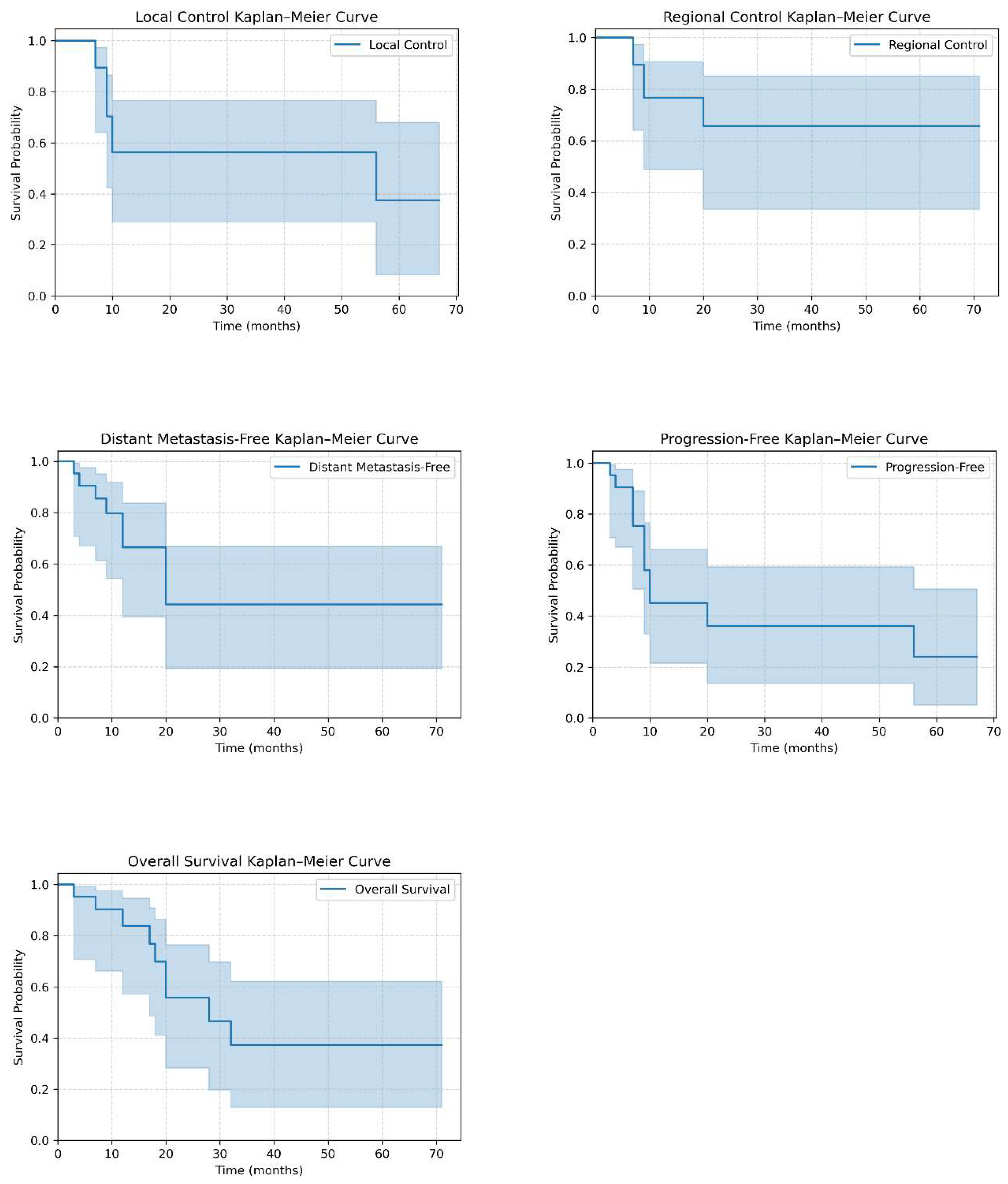

3.2. Treatment Outcomes

3.3. Univariable Analyses and Feature Selection

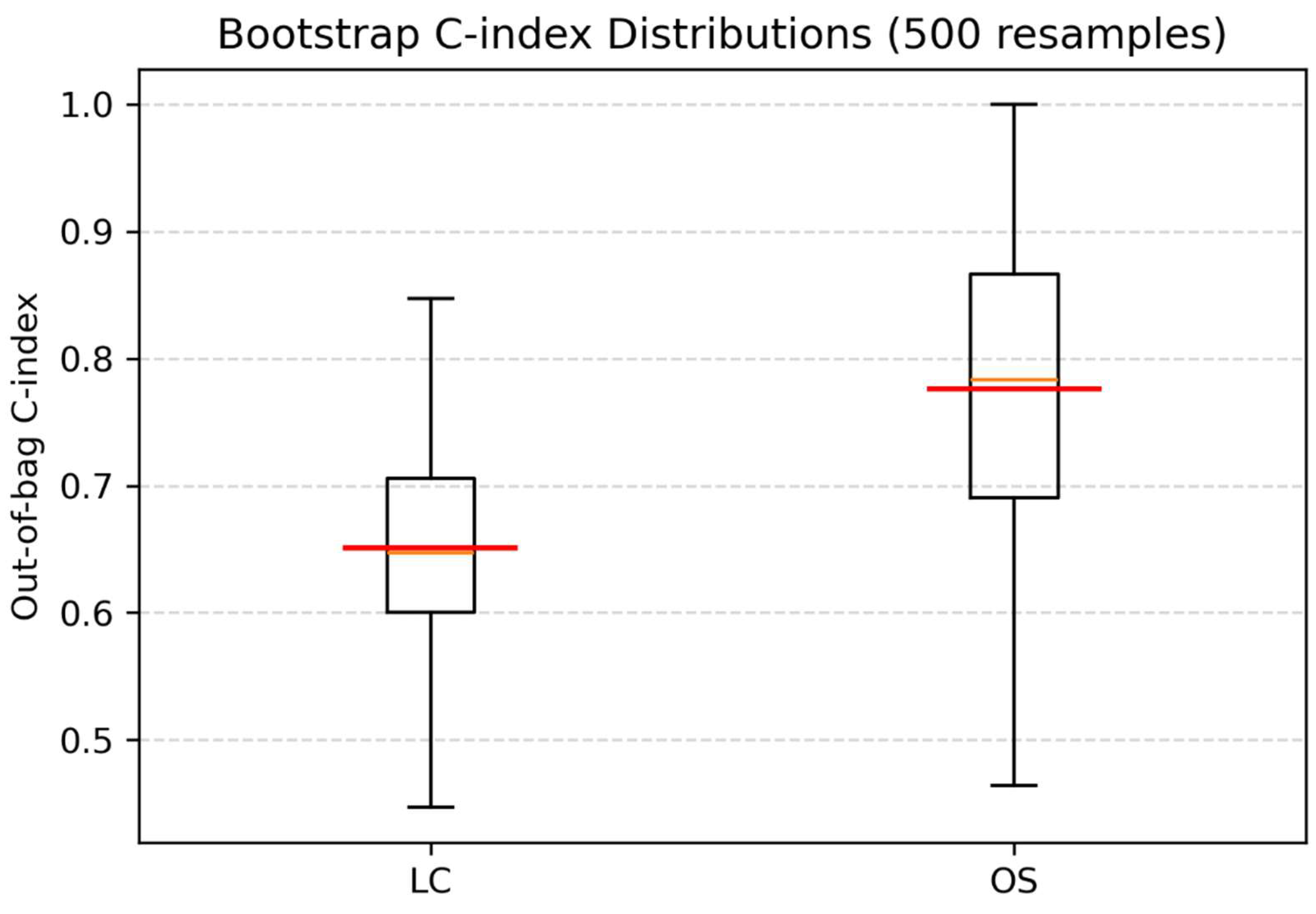

3.4. Multivariable Analyses and Internal Validation

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Ethics Approval

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [CrossRef]

- Buttmann-Schweiger, N.; Klug, S.J.; Luyten, A.; Holleczek, B.; Heitz, F.; du Bois, A.; Kraywinkel, K.; Grce, M. Incidence Patterns and Temporal Trends of Invasive Nonmelanotic Vulvar Tumors in Germany 1999-2011. A Population-Based Cancer Registry Analysis. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0128073. [CrossRef]

- Alkatout, I.; Schubert, M.; Garbrecht, N.; Weigel, M.T.; Jonat, W.; Mundhenke, C.; Günther, V. Vulvar cancer: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and management options. Int. J. Women’s Health 2015, 7, 305–313. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Yashar, C.M.; Arend, R.; Barber, E.; Bradley, K.; Brooks, R.; Campos, S.M.; Chino, J.; Chon, H.S.; Crispens, M.A.; et al. Vulvar Cancer, Version 3.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2024, 22, 117–135. [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.J.; Chin, R.-I.; Hui, C.; Mutch, D.G.; Powell, M.A.; Schwarz, J.K.; Grigsby, P.W.; Markovina, S. Improved survival with definitive chemoradiation compared to definitive radiation alone in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: A review of the National Cancer Database. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 146, 572–579. [CrossRef]

- Macchia, G.; Lancellotta, V.; Ferioli, M.; Casà, C.; Pezzulla, D.; Pappalardi, B.; Laliscia, C.; Ippolito, E.; Di Muzio, J.; Huscher, A.; et al. Definitive chemoradiation in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma: outcome and toxicity from an observational multicenter Italian study on vulvar cancer (OLDLADY 1.1). La Radiol. medica 2023, 129, 152–159. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y, Kim JY, Kim JY, Lee NK, Kim JH, Kim YB, et al. Treatment outcomes of curative radiotherapy in patients with vulvar cancer: results of the retrospective KROG 1203 study. Radiat Oncol J [Internet]. 2015 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Aug 7];33(3):198. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4607573/.

- Prieske K, Haeringer N, Grimm D, Trillsch F, Eulenburg C, Burandt E, et al. Patterns of distant metastases in vulvar cancer. Gynecol Oncol [Internet]. 2016 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Aug 7];142(3):427–34. Available from: https://www.gynecologiconcology-online.net/action/showFullText?pii=S0090825816308782.

- Salom, E.M.; Penalver, M. Recurrent vulvar cancer. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2002, 3, 143–153. [CrossRef]

- Zach, D.; Åvall-Lundqvist, E.; Falconer, H.; Hellman, K.; Johansson, H.; Rådestad, A.F. Patterns of recurrence and survival in vulvar cancer: A nationwide population-based study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 161, 748–754. [CrossRef]

- Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Velazquez, E.R.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Parmar, C.; Grossmann, P.; Carvalho, S.; Bussink, J.; Monshouwer, R.; Haibe-Kains, B.; Rietveld, D.; et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4006. [CrossRef]

- Manganaro, L.; Nicolino, G.M.; Dolciami, M.; Martorana, F.; Stathis, A.; Colombo, I.; Rizzo, S. Radiomics in cervical and endometrial cancer. Br. J. Radiol. 2021, 94, 20201314. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Hou, L.; Tang, X.; Liu, C.; Meng, Y.; Jia, H.; Yang, H.; Zhou, S. CT-based radiomics nomogram may predict who can benefit from adaptive radiotherapy in patients with local advanced-NSCLC patients. Radiother. Oncol. 2023, 183, 109637. [CrossRef]

- Kasai, A.; Miyoshi, J.; Sato, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Miyamoto, H.; Kawanaka, T.; Tonoiso, C.; Harada, M.; Goto, M.; Yoshida, T.; et al. A novel CT-based radiomics model for predicting response and prognosis of chemoradiotherapy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Nafchi, E.R.; Fadavi, P.; Amiri, S.; Cheraghi, S.; Garousi, M.; Nabavi, M.; Daneshi, I.; Gomar, M.; Molaie, M.; Nouraeinejad, A. Radiomics model based on computed tomography images for prediction of radiation-induced optic neuropathy following radiotherapy of brain and head and neck tumors. Heliyon 2024, 11, e41409. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wang, Y.; Shi, X.; Pang, H.; Li, Y. Computed tomography–based radiomics modeling to predict patient overall survival in cervical cancer with intensity-modulated radiotherapy combined with concurrent chemotherapy. J. Int. Med Res. 2025, 53. [CrossRef]

- Shur, J.D.; Doran, S.J.; Kumar, S.; ap Dafydd, D.; Downey, K.; O’cOnnor, J.P.B.; Papanikolaou, N.; Messiou, C.; Koh, D.-M.; Orton, M.R. Radiomics in Oncology: A Practical Guide. RadioGraphics 2021, 41, 1717–1732. [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.-R.; Zhou, Y.-M.; Xie, X.-Y.; Chen, J.-Y.; Quan, K.-R.; Wei, Y.-T.; Xia, X.-Y.; Chen, W.-J. Delta radiomics analysis for prediction of intermediary- and high-risk factors for patients with locally advanced cervical cancer receiving neoadjuvant therapy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Wagner-Larsen, K.S.; Lura, N.; Gulati, A.; Ryste, S.; Hodneland, E.; Fasmer, K.E.; Woie, K.; Bertelsen, B.I.; Salvesen, Ø.; Halle, M.K.; et al. MRI delta radiomics during chemoradiotherapy for prognostication in locally advanced cervical cancer. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Reade, C.J.; Eiriksson, L.R.; Mackay, H. Systemic therapy in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: Current status and future directions. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 132, 780–789. [CrossRef]

- Xia P, Murray E. 3D treatment planning system—Pinnacle system. Med Dosim [Internet]. 2018 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Aug 8];43(2):118–28. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29580933/.

- van Griethuysen, J.J.M.; Fedorov, A.; Parmar, C.; Hosny, A.; Aucoin, N.; Narayan, V.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Fillion-Robin, J.-C.; Pieper, S.; Aerts, H.J.W.L. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, e104–e107. [CrossRef]

- Limkin, E.J.; Sun, R.; Dercle, L.; Zacharaki, E.I.; Robert, C.; Reuzé, S.; Schernberg, A.; Paragios, N.; Deutsch, E.; Ferté, C. Promises and challenges for the implementation of computational medical imaging (radiomics) in oncology. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1191–1206. [CrossRef]

- Vallières, M.; Kay-Rivest, E.; Perrin, L.J.; Liem, X.; Furstoss, C.; Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Khaouam, N.; Nguyen-Tan, P.F.; Wang, C.-S.; Sultanem, K.; et al. Radiomics strategies for risk assessment of tumour failure in head-and-neck cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Atiya, H.I.; Gorecki, G.; Garcia, G.L.; Frisbie, L.G.; Baruwal, R.; Coffman, L. Stromal-Modulated Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer Cells. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1604. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Z.; Weng, Y.; Fang, Z.; Xiao, F.; Zhang, C.; Fan, Z.; Huang, K.; Zhu, Y.; et al. The progress of multimodal imaging combination and subregion based radiomics research of cancers. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 3458–3469. [CrossRef]

- Nooij, L.; Brand, F.; Gaarenstroom, K.; Creutzberg, C.; de Hullu, J.; van Poelgeest, M. Risk factors and treatment for recurrent vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2016, 106, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Woelber, L.; Eulenburg, C.; Kosse, J.; Neuser, P.; Heiss, C.; Hantschmann, P.; Mallmann, P.; Tanner, B.; Pfisterer, J.; Jückstock, J.; et al. Predicting the course of disease in recurrent vulvar cancer – A subset analysis of the AGO-CaRE-1 study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 154, 571–576. [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, D.K.; King, B.; Viswanathan, A.N.; Barkati, M.; Beriwal, S.; Eifel, P.; Erickson, B.; Fyles, A.; Goulart, J.; Harkenrider, M.; et al. Consensus Recommendations for Radiation Therapy Contouring and Treatment of Vulvar Carcinoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2016, 95, 1191–1200. [CrossRef]

- Collarino, A.; Garganese, G.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Arias-Bouda, L.M.P.; Ieria, F.P.; Boellaard, R.; Rufini, V.; de Geus-Oei, L.-F.; Scambia, G.; Olmos, R.A.V.; et al. Radiomics in Vulvar Cancer: First Clinical Experience Using18F-FDG PET/CT Images. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 60, 199–206. [CrossRef]

- Ger, R.B.; Wei, L.; El Naqa, I.; Wang, J. The Promise and Future of Radiomics for Personalized Radiotherapy Dosing and Adaptation. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2023, 33, 252–261. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Kadoya, N.; Sugai, Y.; Umeda, M.; Ishizawa, M.; Katsuta, Y.; Ito, K.; Takeda, K.; Jingu, K. A deep learning-based radiomics approach to predict head and neck tumor regression for adaptive radiotherapy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Abuhijla, F.; Salah, S.; Al-Hussaini, M.; Mohamed, I.; Jaradat, I.; Dayyat, A.; Almasri, H.; Allozi, A.; Arjan, A.; Almousa, A.; et al. Factors influencing the use of adaptive radiation therapy in vulvar carcinoma. Rep. Pr. Oncol. Radiother. 2020, 25, 709–713. [CrossRef]

- Gaffney DK, King B, Viswanathan AN, Barkati M, Beriwal S, Eifel P, et al. No Title. 2016 Jul 15 [cited 2025 Aug 8];95(4). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27130794/.

- Oonk, M.H.; Planchamp, F.; Baldwin, P.; Mahner, S.; Mirza, M.R.; Fischerová, D.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Guillot, E.; Garganese, G.; Lax, S.; et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Vulvar Cancer - Update 2023. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 1023–1043. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Median | IQR | |||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 57 | 17 | |||

| Total vulvar dose (Gy) | 65 | 2.6 | |||

| External-beam Radiotherapy dose in Gy | 45 | 5.4 | |||

| External-beam Radiotherapy number of fractions | 25 | 3 | |||

| Nodal dose (Gy) | 63 | 12 | |||

| EBRT Time (days) | 54 | 10 | |||

| Chemotherapy cycles | 5 | 1 | |||

| Variable | Category | Count | Percentage (%) | ||

| Grade | 1 | 1 | 4.8 | ||

| 2 | 15 | 71.4 | |||

| 3 | 4 | 19 | |||

| Missing | 1 | 4.8 | |||

| HPV Categories | Not associated | 12 | 57.1 | ||

| HPV-associated | 7 | 33.3 | |||

| Missing | 2 | 9.5 | |||

| FIGO Stage | II | 1 | 4.8 | ||

| IIIA | 1 | 4.8 | |||

| IIIB | 7 | 33.3 | |||

| IIIC | 1 | 4.8 | |||

| IVA | 2 | 9.5 | |||

| IVB | 6 | 28.6 | |||

| Missing | 3 | 14.3 | |||

| Concurrent Chemotherapy | Yes | 20 | 95.2 | ||

| No | 1 | 4.8 | |||

| Endpoint | Events (n) | Total (n) | Event rate (%) | Events ≤24 months (n) | ≤24 months (%) |

| Local Control | 8 | 21 | 38.1 | 7 | 87.5 |

| Regional Control | 5 | 21 | 23.8 | 5 | 100.0 |

| Distant Metastasis–Free | 9 | 21 | 42.9 | 9 | 100.0 |

| Progression–Free | 12 | 21 | 57.1 | 11 | 91.7 |

| Overall Survival | 9 | 21 | 42.9 | 7 | 77.8 |

| Endpoint | Selected Δ features |

| LC | GLCM Inverse Difference Moment (IDM) |

| GLRLM Run Length Non-Uniformity Normalized (RLNU_norm) | |

| GLRLM Run Percentage (RP) | |

| First-order Entropy | |

| GLCM Difference Entropy (DiffEnt) | |

| GLCM Cluster Prominence (ClusProm) | |

| RC | none retained |

| DMFS | none retained |

| PFS | none retained |

| OS | GLCM Difference Average (DiffAvg) |

| Shape Surface-Volume Ratio (SVR) | |

| GLCM Difference Variance (DiffVar) | |

| GLDM Large Dependence Low Gray-Level Emphasis (LDLGLE) | |

| GLSZM Size Zone Non-Uniformity (SZNU) | |

| GLSZM Gray-Level Non-Uniformity Normalized (GLNU_norm) | |

| GLSZM Zone Entropy (ZoneEnt) | |

| GLSZM Gray-Level Variance (GLVar) | |

| First-order Energy |

| Multivariable Cox model for LC (retaining one variable) | ||||

| Δ Feature | Coef | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

| GLRLM Run-Length Non-Uniformity Normalized (RLNU_norm) | 0.9625 | 2.618 | [1.05, 6.52] | 0.0388 |

| Multivariable Cox model for OS (time-varying) | ||||

| Feature | Coef | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

| GLCM Difference Average (DiffAvg) | –9.0097 | 0.00012 | [3×10−8, 0.48] | 0.0327 |

| Shape Surface-Volume Ratio (SVR) | 5.7666 | 319.45 | [1.74, 5.9×104] | 0.0302 |

| GLCM Difference Variance (DiffVar) | 5.7931 | 328.02 | [1.33, 8.1×104] | 0.0393 |

| GLDM Large Dependence Low Gray-Level Emphasis (LDLGLE) | –8.3732 | 0.00023 | [1×10−8, 5.28] | 0.1021 |

| GLSZM Gray-Level Non-Uniformity Normalized (GLNU_norm) | –9.2533 | 0.00010 | [3×10−8, 0.33] | 0.0259 |

| First-order Energy | –1.6158 | 0.1987 | [0.03, 1.22] | 0.0807 |

| Multivariable Cox model for LC (retaining one variable) | ||||

| Δ Feature | Coef | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

| GLRLM Run-Length Non-Uniformity Normalized (RLNU_norm) | 0.9625 | 2.618 | [1.05, 6.52] | 0.0388 |

| Multivariable Cox model for OS (time-varying) | ||||

| Feature | Coef | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

| GLCM Difference Average (DiffAvg) | –9.0097 | 0.00012 | [3×10−8, 0.48] | 0.0327 |

| Shape Surface-Volume Ratio (SVR) | 5.7666 | 319.45 | [1.74, 5.9×104] | 0.0302 |

| GLCM Difference Variance (DiffVar) | 5.7931 | 328.02 | [1.33, 8.1×104] | 0.0393 |

| GLDM Large Dependence Low Gray-Level Emphasis (LDLGLE) | –8.3732 | 0.00023 | [1×10−8, 5.28] | 0.1021 |

| GLSZM Gray-Level Non-Uniformity Normalized (GLNU_norm) | –9.2533 | 0.00010 | [3×10−8, 0.33] | 0.0259 |

| First-order Energy | –1.6158 | 0.1987 | [0.03, 1.22] | 0.0807 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).