Submitted:

03 September 2025

Posted:

04 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

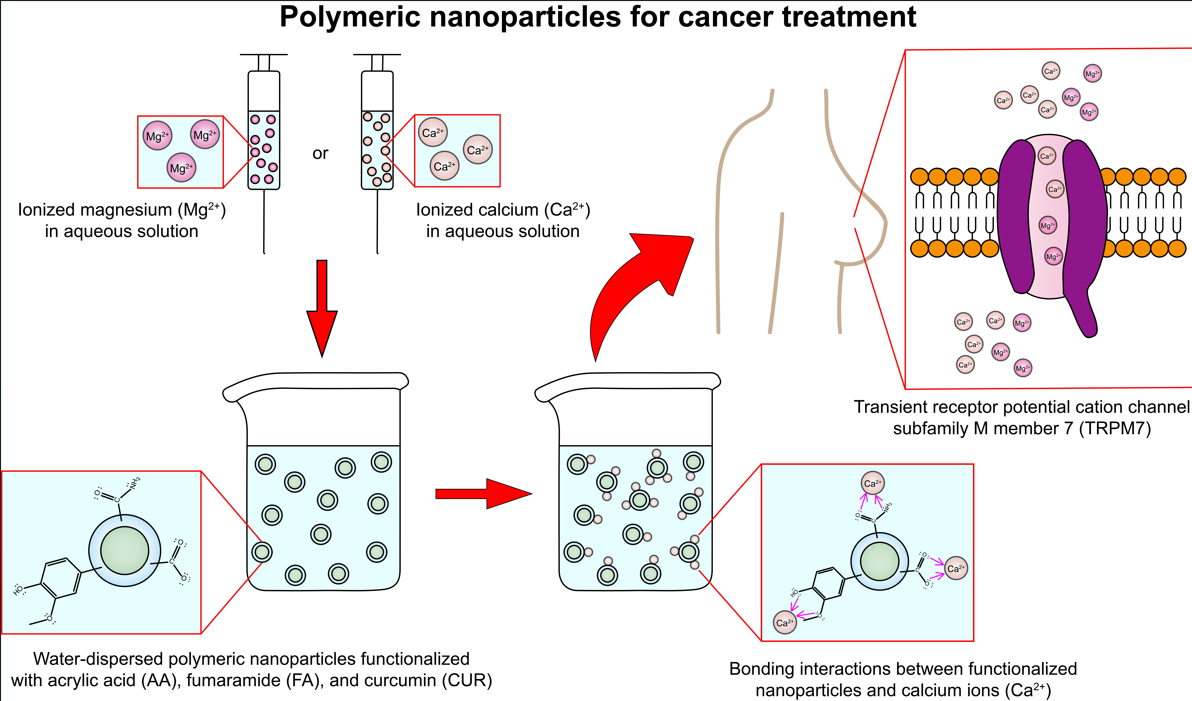

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

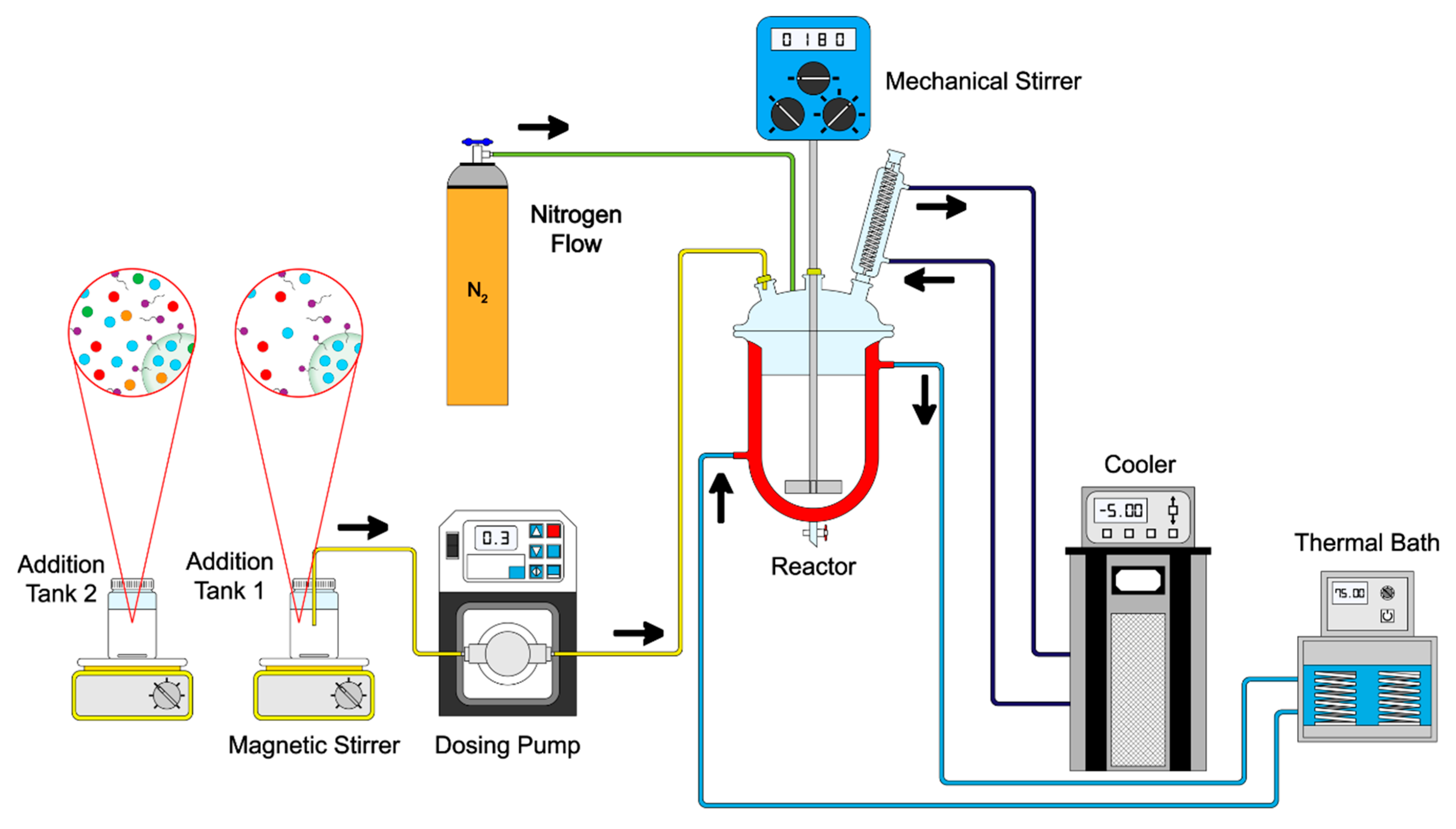

2.2. Synthesis of Functionalized Polymeric Nanoparticles

2.3. Characterization Techniques

2.3.1. Gravimetry

2.3.2. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Electrophoresis

2.3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

2.3.4. Ultraviolet–Visible Spectroscopy (UV-Vis)

2.3.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.3.6. Photoluminescence Spectroscopy (PL)

2.3.7. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.3.8. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and the Total Solid Content of Polymeric Nanoparticles with Different Ratios of Chelatings Agents

3.2. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Zeta Potential (ζ) of Polymeric Nanoparticles with Different Ratios of Chelatings Agents

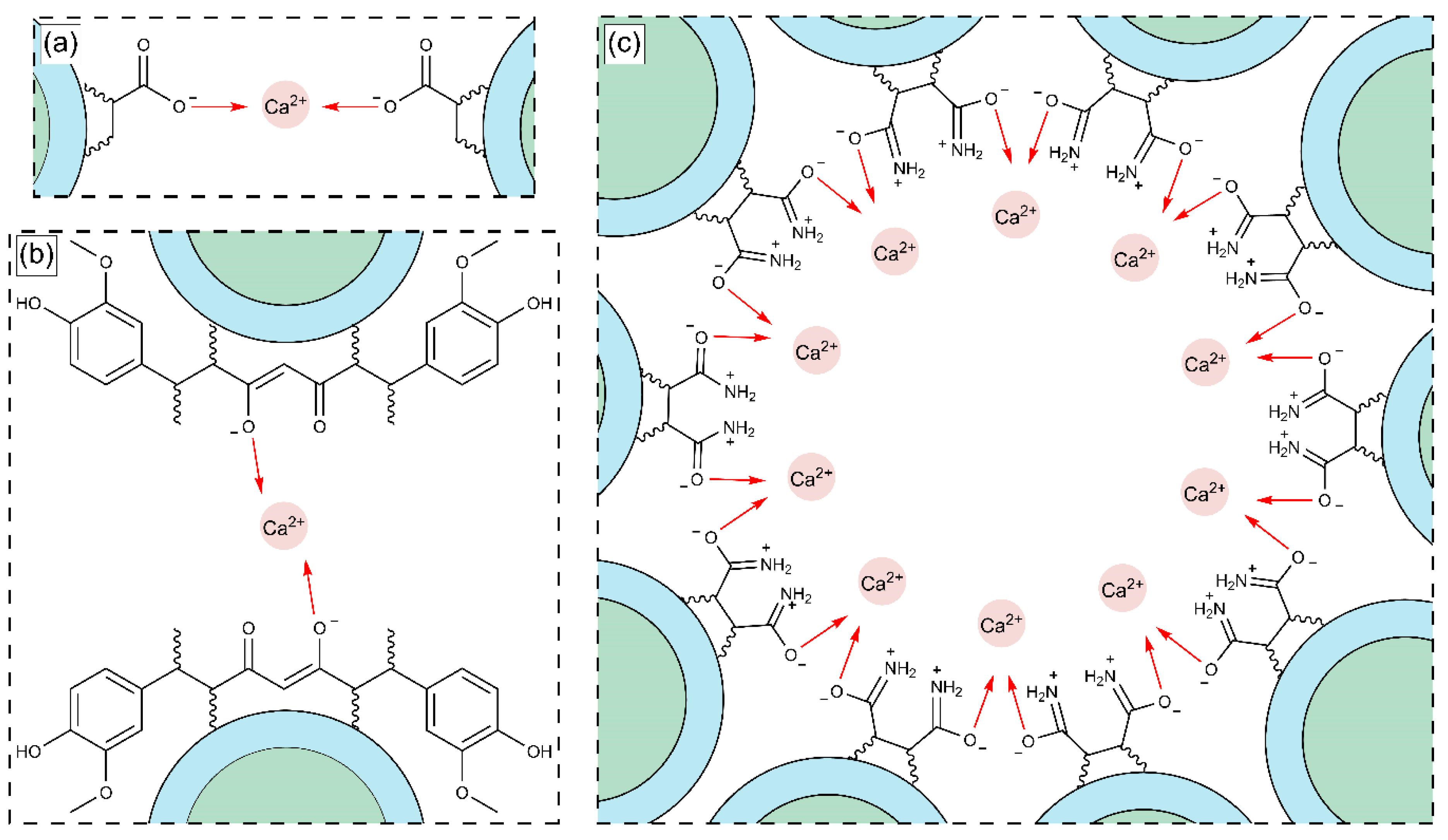

3.3. Interaction of Polymeric Nanoparticles with Different Ratios of Chelatings Agents and Calcium (Ca2+) and Magnesium (Mg2+) Ions

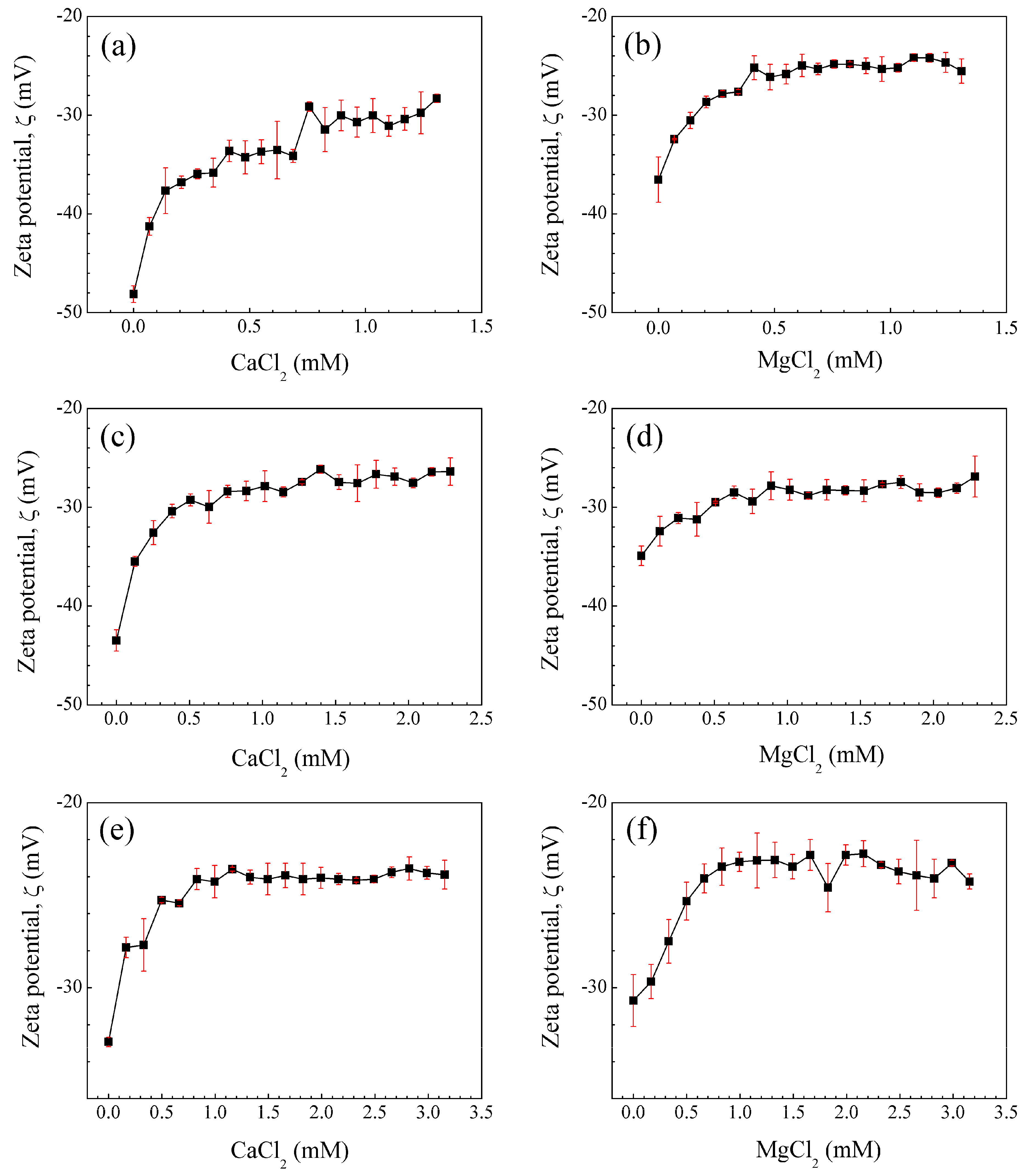

3.3.1. Zeta Potential (ζ) of Polymeric Nanoparticles with Different Ratios of Chelatings Agents

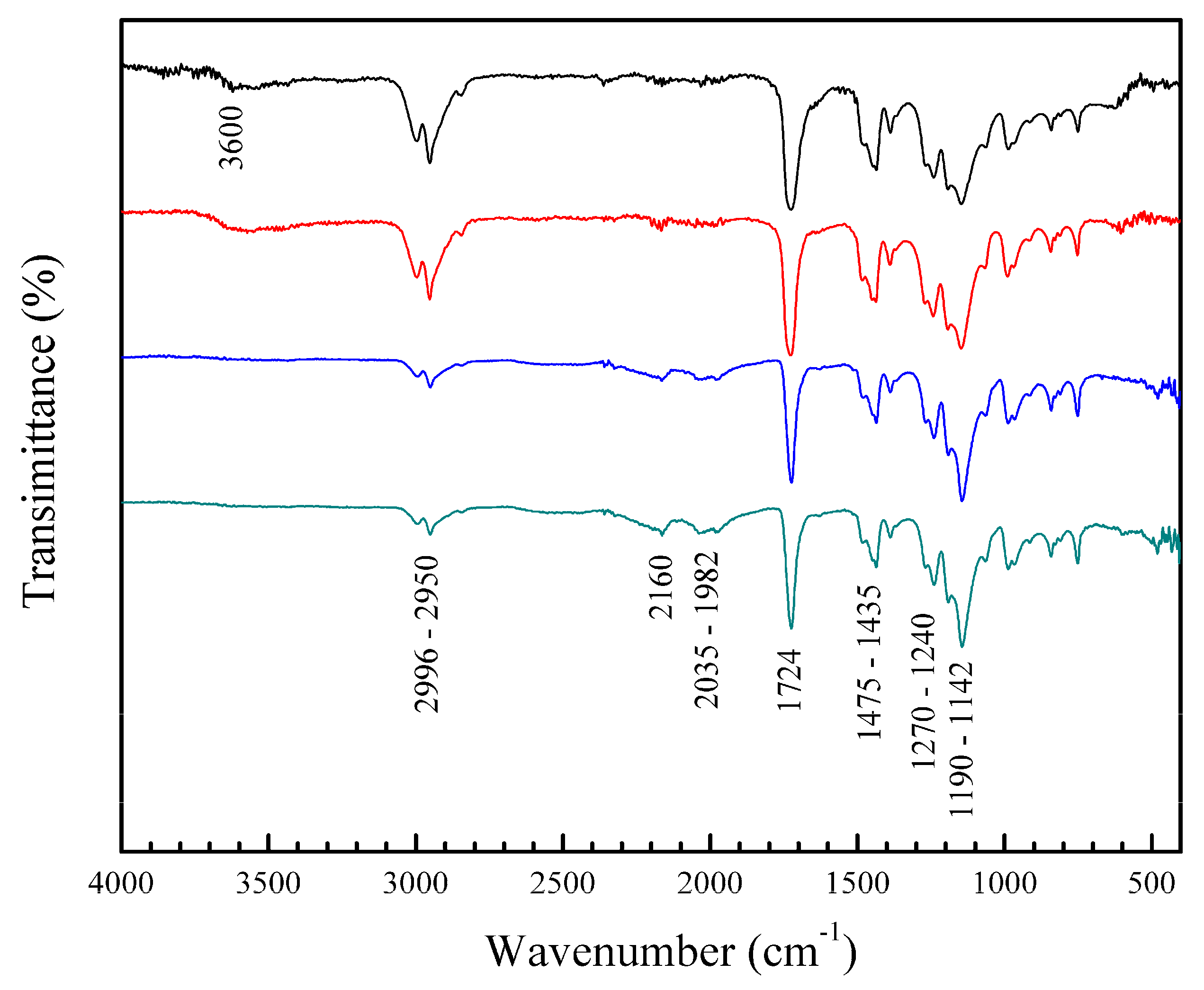

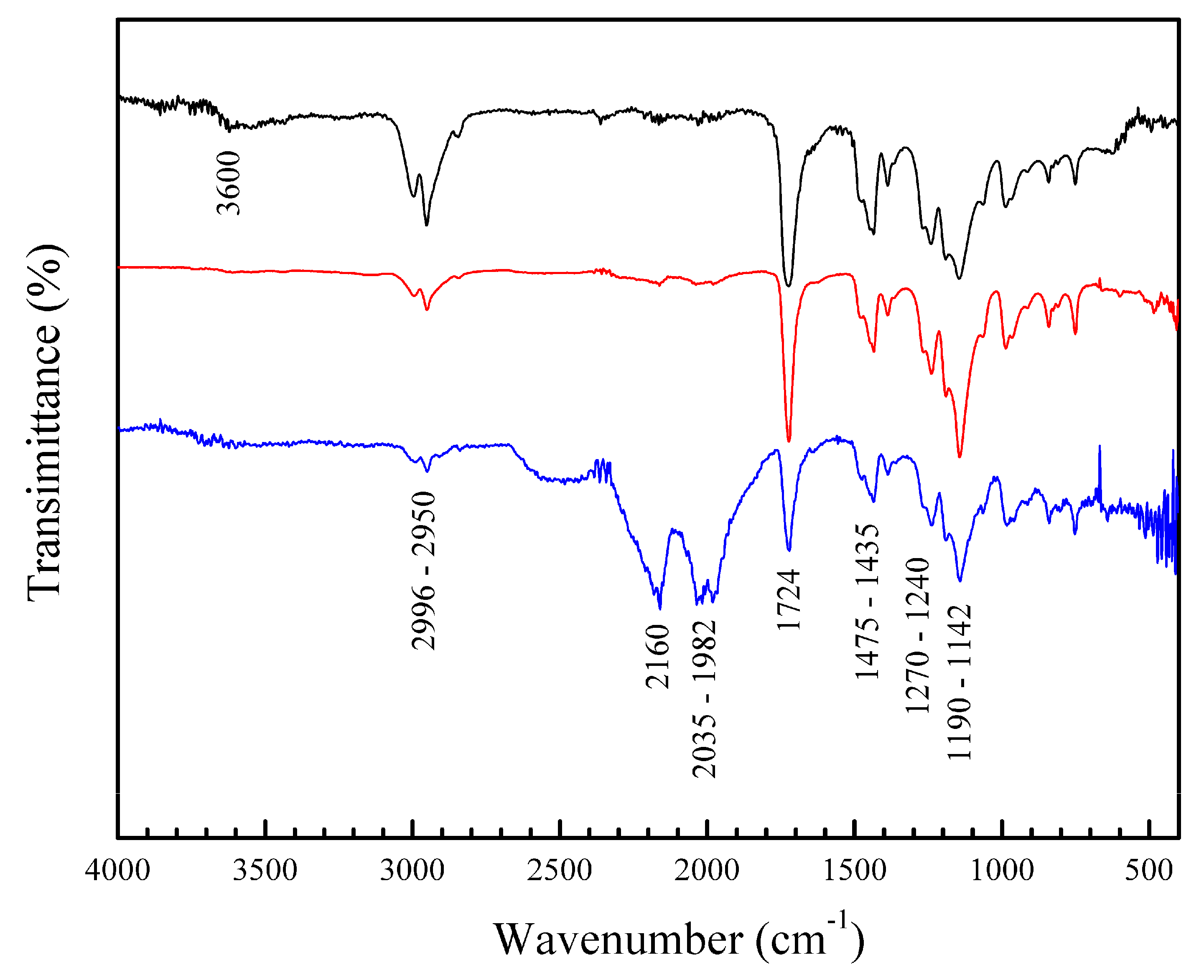

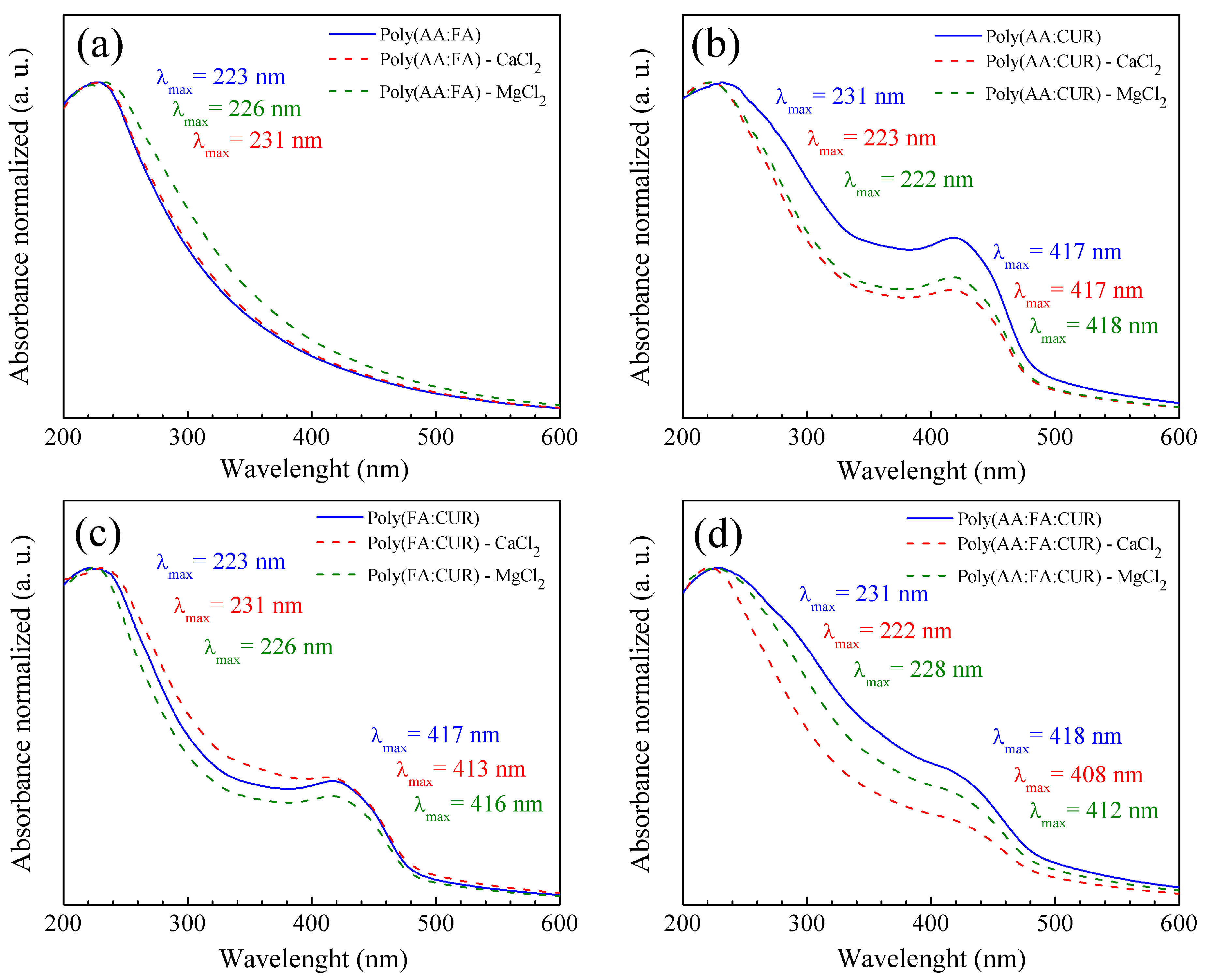

3.3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) and Ultraviolet–Visible (UV-VIS) Spectra of Polymeric Nanoparticles with Different Ratios of Chelatings Agents

3.3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of Polymeric Nanoparticles with Different Ratios of Chelatings Agents

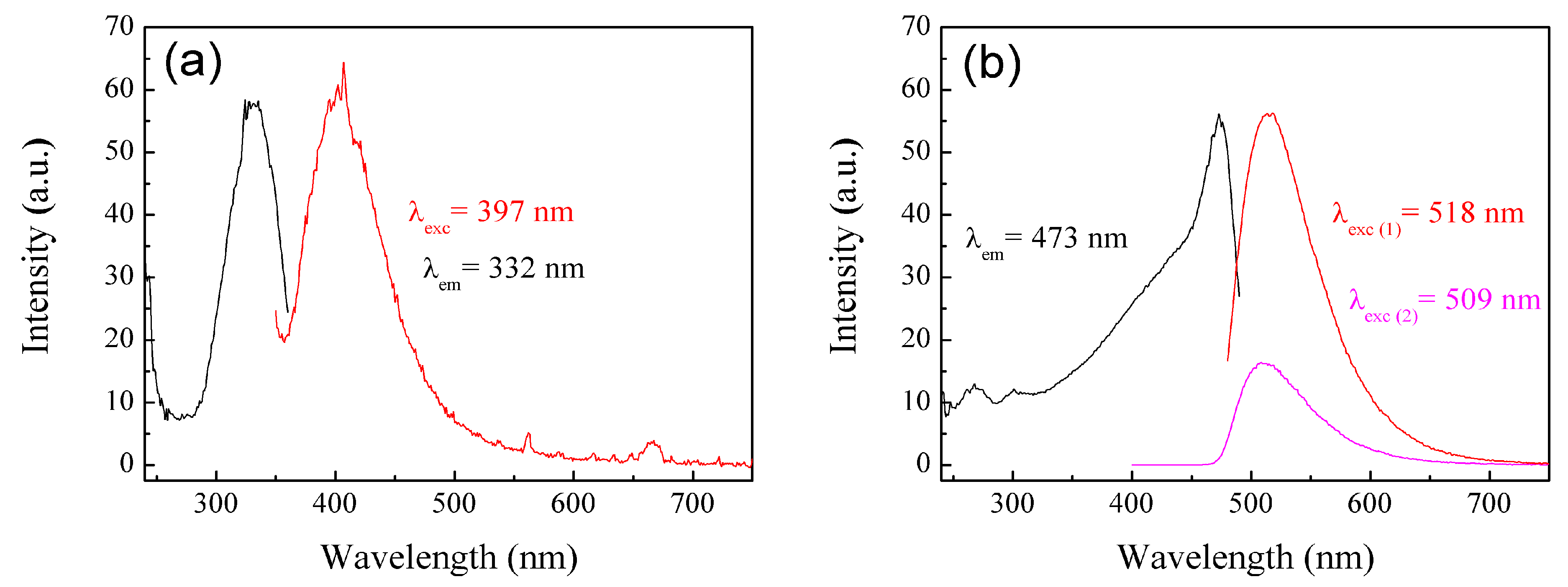

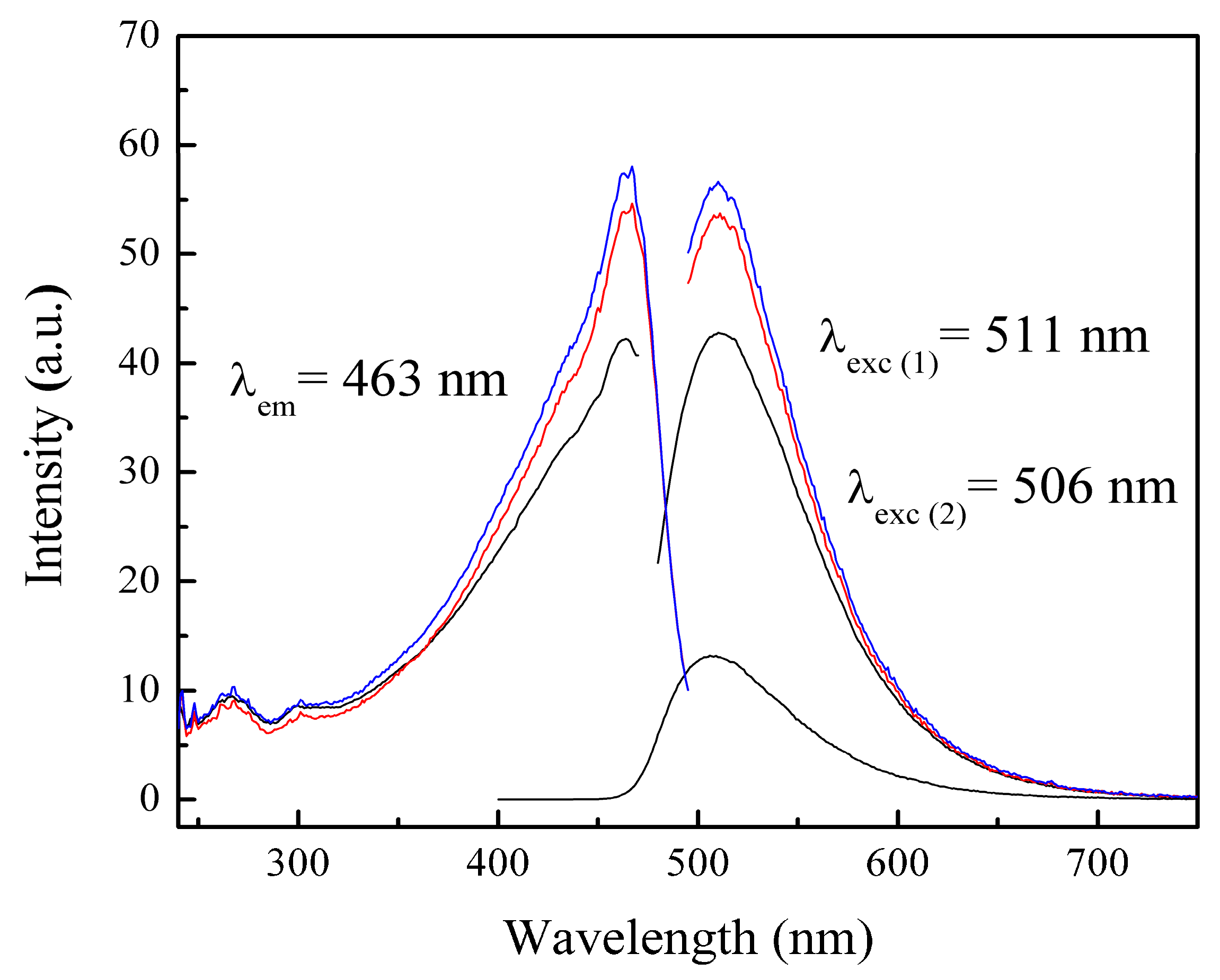

3.3.4. Photoluminescence (PL) Spectra of Polymeric Nanoparticles with Different Ratios of Chelatings Agents

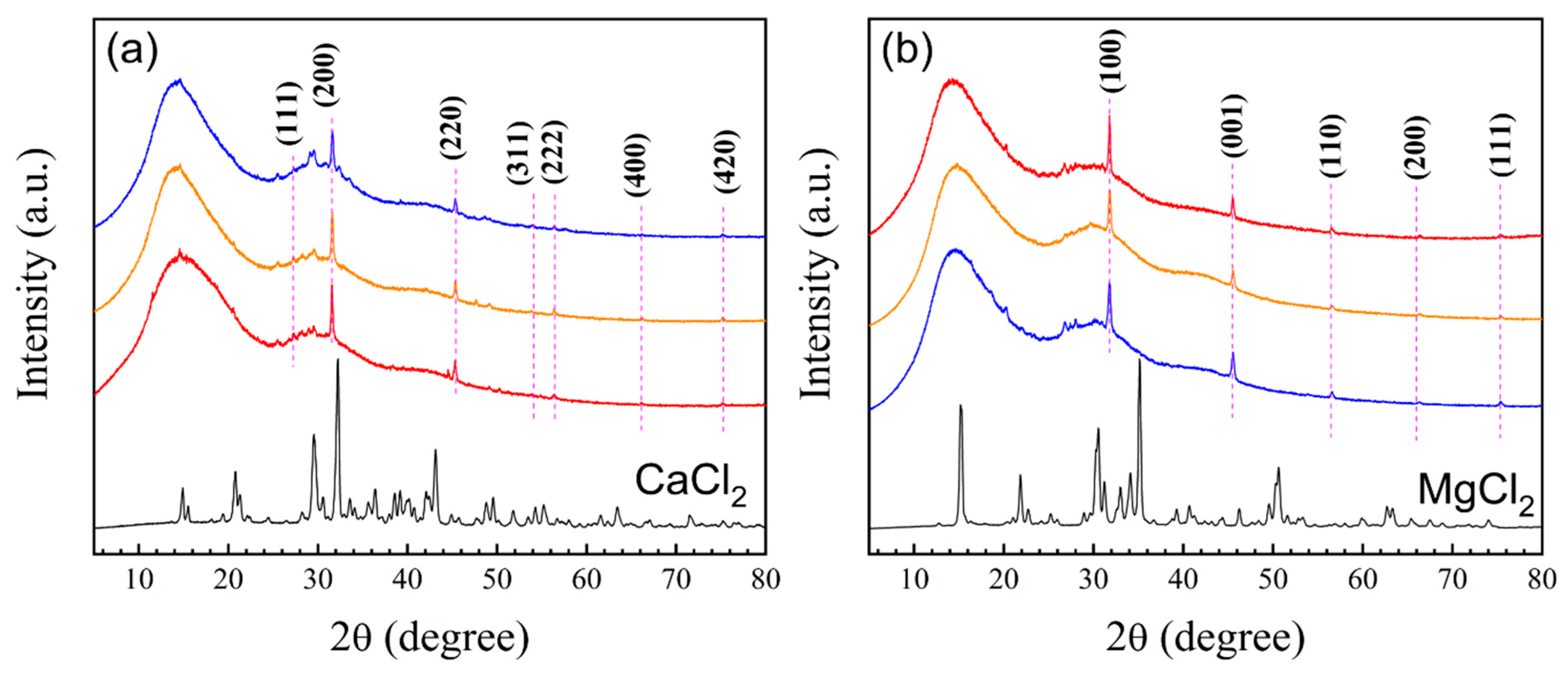

3.3.5. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Spectra of Polymeric Nanoparticles with Different Ratios of Chelatings Agents

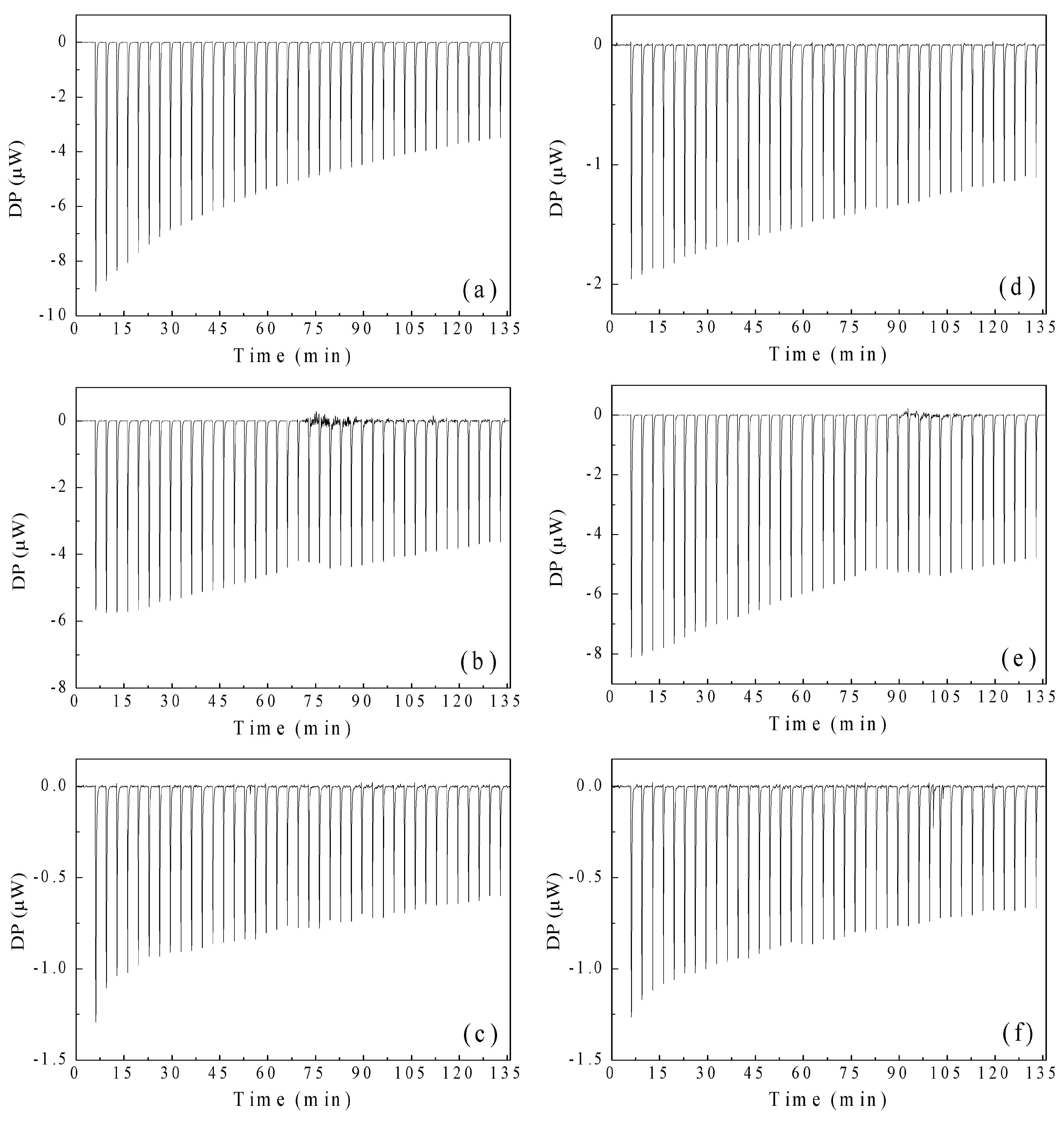

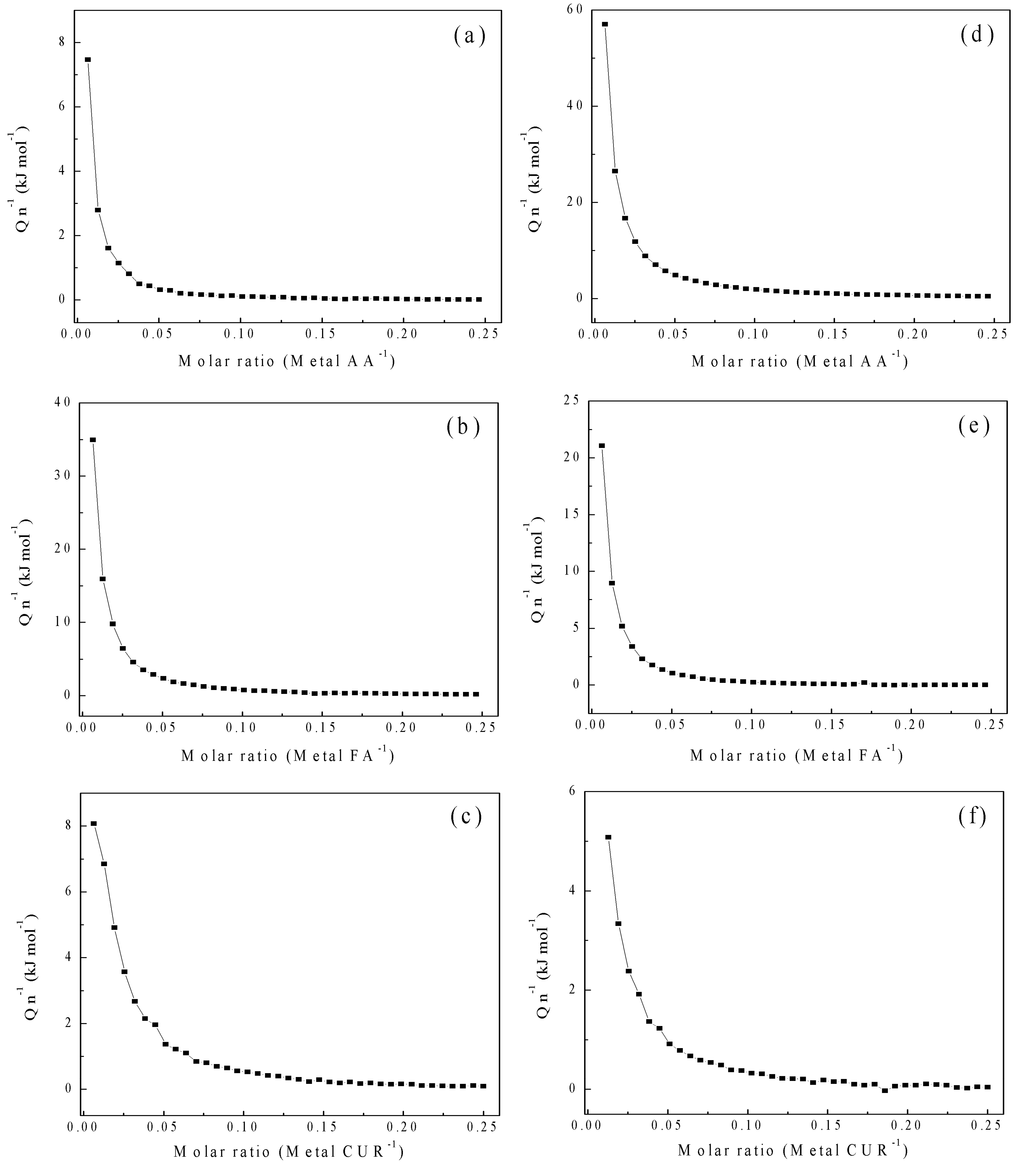

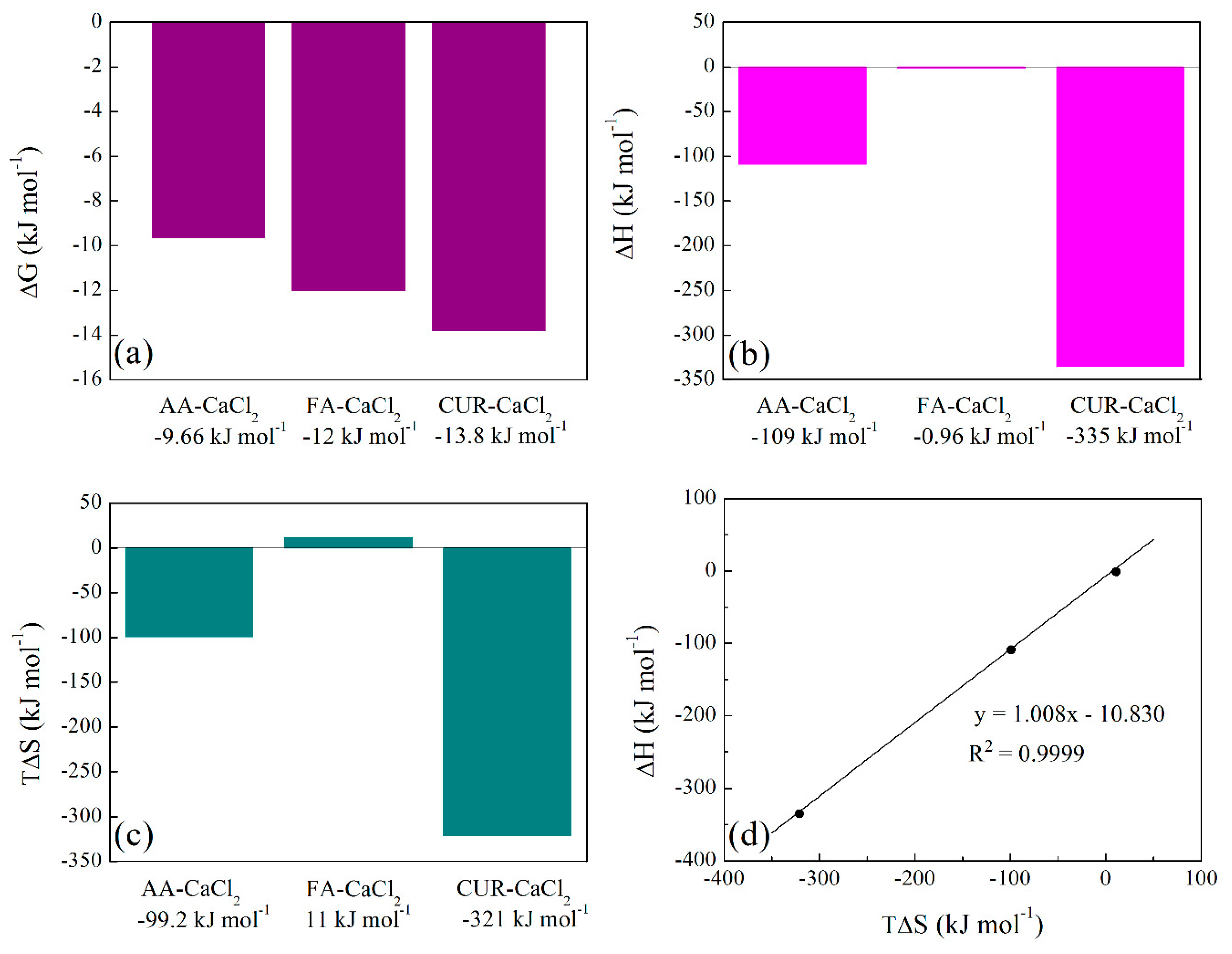

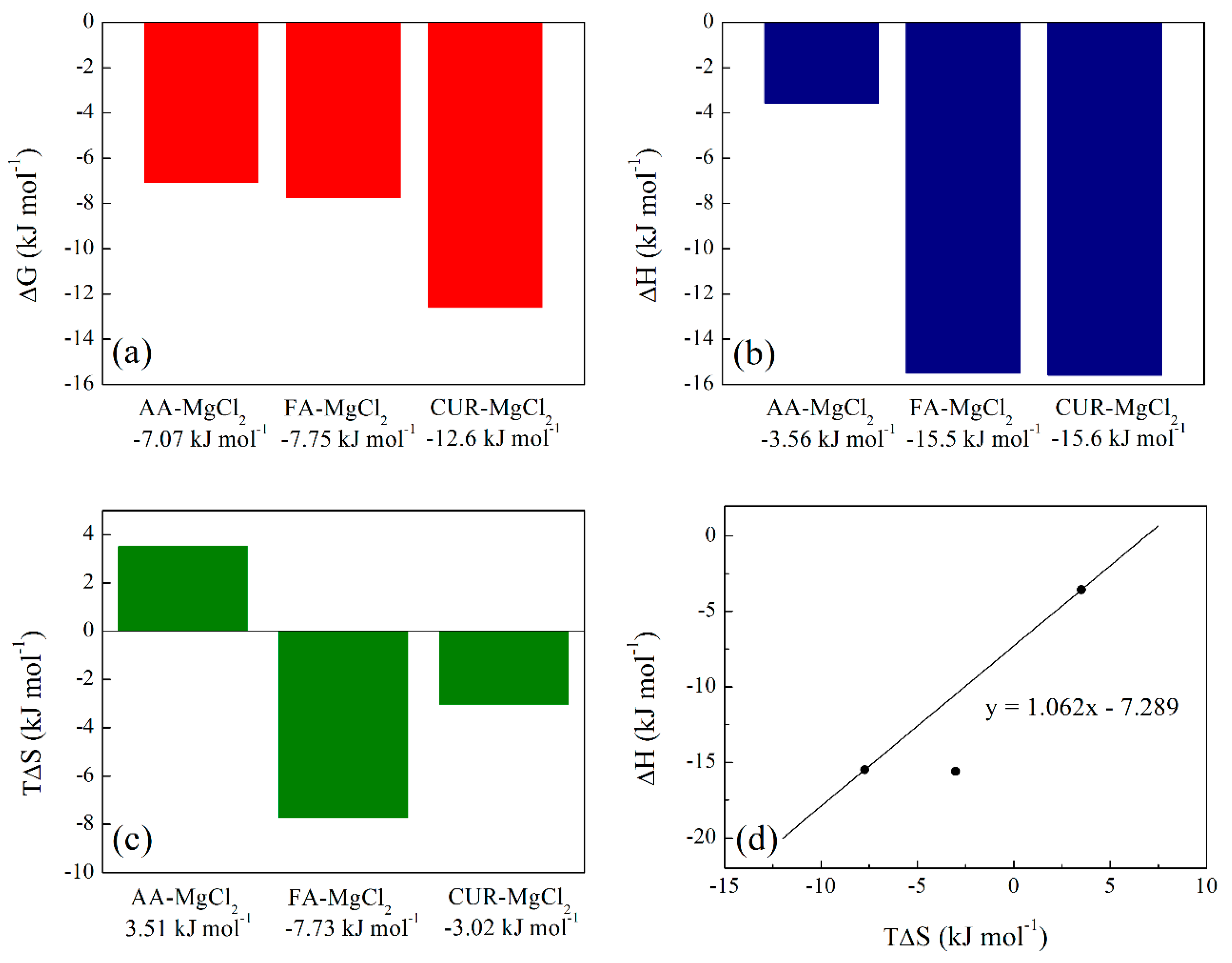

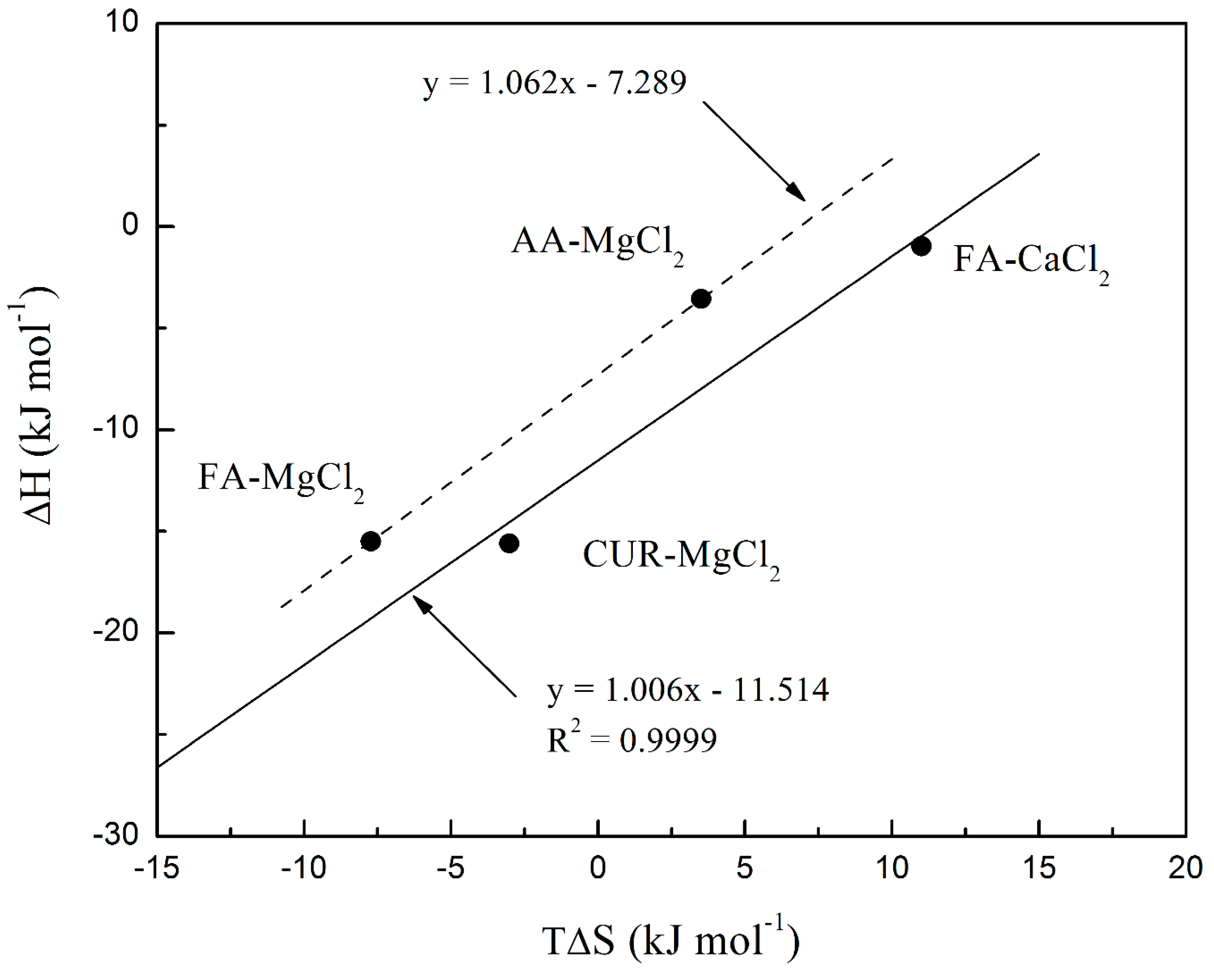

3.3.6. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) of Polymeric Nanoparticles with Different Ratios of Chelatings Agents

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, J.S; Amend, S.R.; Austin, R.H.; Gatenby, R.A.; Hammarlund, E.U.; Pienta, K.J. Updating the Definition of Cancer, Mol. Cancer. Res. 2023, 21, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnamte, M.; Pulikkal, A. K. Biocompatible polymeric nanoparticles as carriers for anticancer phytochemicals. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 202, 112637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer, World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cancer#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- Yang, F.; He, Q.; Dai, X.; Zhang, X.; Song, D. The potential role of nanomedicine in the treatment of breast cancer to overcome the obstacles of current therapies. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1143102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbeck, N.; Gnant, M. Breast cancer. Lancet. 2017, 389, 1134–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Yin, S.; Nie, J. Challenges and prospects in HER2-positive breast cancer-targeted therapy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 207, 104624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xue, L.; Han, C.; Wu, W.; Lu, N.; Lu, X. GnRHR inhibits the malignant progression of triple-negative breast cancer by upregulating FOS and IFI44L. Genomics 2025, 117, 111021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granados-Garcia, M.; Herrera-Gómez, A. Manual de oncología. Procedimientos médico quirúrgicos, 4th ed.; Mc Graw Hill interamericana editores, S.A. de C.V: CDMX, México, 2010; pp. 1–1315. [Google Scholar]

- Guanghui, R.; Xiaoyan, H.; Shuyi, Y.; Jun, C.; Guobin, Q. An efficient or methodical review of immunotherapy against breast cancer. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2019, 33, e22339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzaman, K.; Karami, J.; Zarei, Z.; Aysooda, H.; Kazemi, M.H.; Moradi-Kalbolandi, S.; Safari, E.; Farahmand, L. Breast cancer: Biology, biomarkers, and treatments. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 84, 106535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuerstlein, R.; Harbeck, N. Neoadjuvant Therapy for HER2-positive Breast Cancer, Rev. Recent. Clin. Trials. 2017, 12, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uttpal, A.; Abhijit, D.; Arvind, K.S.C.; Rupa, S.; Amarnath, M.; Devendra, K.P.; Valentina, F.; Arun, U.; Ramesh, K.; Anupama, C.; Jaspreet, K. D.; Saikat, D.; Jayalakshmi, V.; José, M.P.L. Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: Current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics. Genes Dis. 2023, 10, 1367–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariam, A.; Peter, K.; Martin, C.; Elizabeth, V.; Barbora, Z.; Pavol, Z.; Radka, O.; Peter, K.; Patrik, S.; Dietrich, B. Chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer: An update. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 101, 458–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsson, A.; Fugl-Meyer, K.; Bordas, P.; Åhman, J.; Von Wachenfeldt, A. Side Effects and Its Management in Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Breast Cancer: A Matter of Communication and Counseling. Breast Cancer: Basic and Clinical Research. 2023, 17, 117822342211454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.; Finikarides, L.; Freeman, A.L.J. The adverse effects of trastuzumab-containing regimes as a therapy in breast cancer: A piggy-back systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Domínguez, D.J.; López-Enríquez, S.; Alba, G.; Garnacho, C.; Jiménez-Cortegana, C.; Flores-Campos, R.; de la Cruz-Merino, L.; Hajji, N.; Sánchez-Margalet, V.; Hontecillas-Prieto, L. Cancer Nano-Immunotherapy: The Novel and Promising Weapon to Fight Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzaniga, M.E.; Capici, S.; Cordani, N.; Cogliati, V.; Pepe, F.F.; Riva, F.; Cerrito, M.G. Metronomic Chemotherapy for Metastatic Breast Cancer Treatment: Clinical and Preclinical Data between Lights and Shadows. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panthi, V.K.; Dua, K.; Singh, S.K.; Gupta, G.; Hansbro, P.M.; Paudel, K.R. Nanoformulations-Based Metronomic Chemotherapy: Mechanism, Challenges, Recent Advances, and Future Perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahire, S.A.; Bachhav, A.A.; Pawar, T.B.; Jagdale, B.S.; Patil, A.V.; Koli, P.B. The Augmentation of nanotechnology era: A concise review on fundamental concepts of nanotechnology and applications in material science and technology. Results Chem. 2022, 4, 100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhi, K.C.; Yadav, M. Synthesis of inorganic nanomaterials using carbohydrates. In Green Sustainable Process for Chemical and Environmental Engineering and Science, 1st. ed.; Inamuddin, Boddula, R., Ahamed, M.I., Asiri, A.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, D.; Das, K.P.; Deepak, K.S.; Das, B. Candidates of functionalized nanomaterial-based membranes, In Membranes with Functionalized Nanomaterials, 1st. ed.; Dutta, S., Hussain, C.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2022; pp. 81–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, L.R.; Parui, R.; Khatun, M.N.; Chanu, M.A.; Li, L.; Wang, S.; Iyer, P.K. Nanomaterials for sensors: Synthesis and applications, In Advanced Nanomaterials for Point of Care Diagnosis and Therapy. 1st. ed.; Dave, S., Das, J., Ghosh, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2022; pp. 121–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Virgen, L.; Hernandez-Martinez, M.A.; Martínez-Mejía, G.; Caro-Briones, R.; Herbert-Pucheta, E.; Del Río, J.M.; Corea, M. Analysis of Structural Changes of pH–Thermo-Responsive Nanoparticles in Polymeric Hydrogels. Gels 2024, 10, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Shen, X.; Nie, Z. Engineering interactions between nanoparticles using polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2023, 143, 101710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solangi, N.H.; Karri, R.R.; Mubarak, N.M.; Mazari, S.A. Mechanism of polymer composite-based nanomaterial for biomedical applications. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2024, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D.A. Review on Metal-Based Theranostic Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy and Imaging. TCRT 2023, 22, 15330338231191493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfi, M.; Ghomi, M.; Zarrabi, A.; Mohammadinejad, R.; Taraghdari, Z.B.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Zare, E.N.; Agarwal, T.; Padil, V.V.T.; Mokhtari, B. Functionalization of Polymers and Nanomaterials for Biomedical Applications: Antimicrobial Platforms and Drug Carriers. Prosthesis 2020, 2, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Titmuss, S. Polymer-functionalized nanoparticles: from stealth viruses to biocompatible quantum dots. Nanomedicine 2009, 4, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santillán, R.; Nieves, E.; Alejandre, P.; Pérez, E.; Del Río, J.M.; Corea, M. Comparative thermodynamic study of functional polymeric latex particles with different morphologies. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 444, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatankhah, Z.; Dehghani, E.; Salami-Kalajahi, M.; Roghani-Mamaqani, H. 2020. Seed’s morphology-induced core-shell composite particles by seeded emulsion polymerization for drug delivery. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2020, 191, 111008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabogo, I.T.; Nyamato, G.S.; Ogunah, J.; Maqinana, S.; Ojwach, S.O. Extraction of heavy metals from water using chelating agents: a comprehensive review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 8749–8792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sredojević, D.N.; Tomić, Z.D.; Zarić, S.D. Evidence of Chelate−Chelate Stacking Interactions in Crystal Structures of Transition-Metal Complexes. Cryst. Growth Des. 2010, 10, 3901–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhao, H.; Teasdale, P. R.; John, R.; Zhang, S. Synthesis and characterization of a polyacrylamide–polyacrylic acid copolymer hydrogel for environmental analysis of Cu and Cd. React. Funct. Polym. 2002, 52, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomida, T.; Hamaguchi, K.; Tunashima, S.; Katoh, M.; Masuda, S. Binding Properties of a Water-Soluble Chelating Polymer with Divalent Metal Ions Measured by Ultrafiltration. Poly(acrylic acid). Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2001, 40, 3557–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, J.A.; Roy, A.; Talukdar, P. Anion Selective Ion Channel Constructed from a Self-Assembly of Bis(cholate)-Substituted Fumaramide. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 5991–5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, B.; Vijaykumar, M.; Lokesh, B.R. Biological Properties of Curcumin-Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Action. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2004, 44, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amram, A.; Sukanta, D.; Ashish, P.; Kamia, P.; Sara, R. G.; William, L.; Kun-lun, H.; Krishnaswami, R. Green anchors: Chelating properties of ATRP-click curcumin-polymer conjugates. React. Funct. Polym. 2016, 102, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepler, P.K. The role of calcium in cell division. Cell Calcium. 1994, 16, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfa, F. I.; Cittadinia, A.R.M.; Maier, J.A.M. Magnesium and tumors: Ally or foe? Cancer. Treat. Rev. 2009, 35, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National library of Medicine. Magnesium and cancer: more questions than answers. Magnesium in the Central Nervous System [Internet]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507261/ (accessed on day month year).

- Kim, B.J.; Jeon, J.H.; Kim, S.J.; So, I.; Kim, K.W. Regulation of Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 7 (TRPM7) Currents by Mitochondria. Mol. Cells. 2007, 23, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, G. Recent advances in fluorescent probes for ATP imaging. Talanta 2024, 279, 126622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaudia, J.; Marianna, M.; Suliman, Y.A.; Saleh, H.A.; Eugenie, N.; Kamil, K.; Christopher, J.R.; Marian, V. Essential metals in health and disease. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2022, 367, 110173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Pullaguri, N.; Rath, S.N.; Bajaj, A.; Sahu, V.; Ealla, K.K.R. Dysregulation of calcium homeostasis in cancer and its role in chemoresistance. Cancer Drug Resist. 2024, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Virgen, L.; Hernandez-Martinez, M.A.; Martínez-Mejía, G.; Caro-Briones, R.; Del Río, J.M.; Corea, M. Study of Thermodynamic and Rheological Properties of Sensitive Polymeric Nanoparticles as a Possible Application in the Oil Industry. J. Solution Chem. 2024, 53, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Montoya, P.A.; Del Río, J.M.; Morales-Ramirez, A.J.; Corea, M. Europium recovery process by means of polymeric nanoparticles functionalized with acrylic acid, curcumin and fumaramide. J. Rare Earth. 2024, 42, 1950–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvern Instruments (Malvern, UK). Zetasizer Nano User Manual. Preprint 2017. (Phase: Unpublished work).

- Schork, F.J. Monomer Equilibrium and Transport in Emulsion and Miniemulsion Polymerization. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 3249–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.J.; Woo, M.R.; Choi, H.G.; Jin, S.G. Effects of Polymers on the Drug Solubility and Dissolution Enhancement of Poorly Water-Soluble Rivaroxaban. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 22, 9491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasztych, M.; Malamis-Stanowska, A.; Trafalski, M.; Musiał, W. Influence of Composition on the Patterns of Electrokinetic Potential of Thermosensitive N-(Isopropyl)Acrylamide Derivatives with Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Dimethacrylate and N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)Acrylamide. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhanvase, B.A.; Pinjari, D.V.; Sonawane, S.H.; Gogate, P.R.; Pandit, A.B. Analysis of Semibatch Emulsion Polymerization: Role of Ultrasound and Initiator. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2012, 19, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montes, C.; Villaseñor, M.J.; Ríos, A. Analytical control of nanodelivery lipid-based systems for encapsulation of nutraceuticals: Achievements and challenges. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 90, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biriukov, D.; Fibich, P.; Předota, M. Zeta Potential Determination from Molecular Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2020, 124, 3159–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarsini, K.I. The Chemistry of Curcumin: From Extraction to Therapeutic Agent. Molecules. 2014, 19, 20091–20112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, R.; Jacob, J. Design and synthesis of water-soluble chelating polymeric materials for heavy metal ion sequestration from aqueous waste. React. Funct. Polym. 2020, 154, 104687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Montaño, E.L.; Rodríguez-Laguna, N.; Sánchez-Hernández, A.; Rojas-Hernández, A. Determination of pKa Values for Acrylic, Methacrylic and Itaconic Acids by 1H and 13C NMR in Deuterated Water. J. Appl. Sol. Chem. Model. 2015, 4, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChemicalBook. Available online: https://www.chemicalbook.com/ChemicalProductProperty_EN_CB9402245.htm (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Painter, P.; Zhao, H.; Park, Y. Infrared spectroscopic study of thermal transitions in poly(methyl methacrylate). Vib. Spectrosc. 2011, 55, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, H.A.; Zichy, V.J.I.; Hendra, P.J. The laser-Raman and infra-red spectra of poly(methyl methacrylate). Polymer. 1969, 10, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.S.; Chen, Y.J.; Wei, T.C.; Ma, T.L.; Chang, C.C. Comparison of Antibacterial Adhesion When Salivary Pellicle Is Coated on Both Poly(2-hydroxyethyl-methacrylate)- and Polyethylene-glycol-methacrylate-grafted Poly(methyl methacrylate). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayyah, S.M.; El-Shafiey, Z.A.; Barsoum, B.N.; Khaliel, A.B. Infrared spectroscopic studies of poly(methyl methacrylate) doped with a new sulfur-containing ligand and its cobalt(II) complex during γ-radiolysis. Int. J. Polym. Mater. 2005, 54, 1937–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, C.M.; Gatti, F.; Leigh, D.A.; Rapino, S.; Zerbetto, F.; Rudolf, P. Adsorption of Fumaramide Rotaxane and Its Components on a Solid Substrate: A Coverage-Dependent Study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006, 110, 17076–17081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterley, A.S.; Laity, P.; Holland, C.; Weidner, T.; Woutersen, S.; Giubertoni, G. Broadband Multidimensional Spectroscopy Identifies the Amide II Vibrations in Silkworm Films. Molecules 2022, 27, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, K.D.C.; Weragoda, G.K.; Haputhanthri, R.; Rodrigo, S.K. Study of concentration dependent curcumin interaction with serum biomolecules using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy combined with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Square Regression (PLS-R). Vib. Spectrosc. 2021, 116, 103288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lin, Z.; Jiang, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, D.Y. Construction of chelation structure between Ca2+ and starch via reactive extrusion for improving the performances of thermoplastic starch. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 159, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Chen, S.; Rong, J.; Sui, Z.; Wang, S.; Lin, Y.; Xiao, J.; Huang, D. Improving the Ca(II) adsorption of chitosan via physical and chemical modifications and charactering the structures of the calcified complexes. Polym. Test 2021, 98, 107192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, B.P. Infrared (IR) spectroscopy. In Chemical Analysis and Material Characterization by Spectrophotometry, 1st ed.; Eryilmaz, K., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.T.; Zhang, N.; Li, M.R.; Zhang, F.S. Comparison of the ionic effects of Ca2+ and Mg2+ on nucleic acids in liquids. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 344, 117781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, J.N. Colouring materials. In Fundamentals and Practices in Colouration of Textiles, 1st ed.; Chakraborty, J.N., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing India Pvt. Ltd: New Delhi, India, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmouda, K.; Boudiafac, M.; Benhaouad, B. A novel study on the preferential attachment of chromophore and auxochrome groups in azo dye adsorption on different greenly synthesized magnetite nanoparticles: investigation of the influence of the mediating plant extract's acidity. Nanoscale Adv. 2022, 4, 3250–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, J. Handbook of Organic Compounds: NIR, IR, Raman, and UV-Vis Spectra Featuring Polymers and Surfactants. 1st. ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, USA, 2001; pp. 3–421. [Google Scholar]

- Hieu, T.Q.; Thao, D.T.T. Enhancing the Solubility of Curcumin Metal Complexes and Investigating Some of Their Biological Activities. J. Chem. 2019, 1, 8082195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhan, M.A.; Alam, K.; Rahaman, M.S; Rahman, M.A.; Awal, R. Synthesis and Characterization of Metal Complexes Containing Curcumin (C21H20O6) and Study of their Anti-microbial Activities and DNA-binding Properties. J. Sci. Res. 2014, 6, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Zhanga, S.; Wang, J. Advances in crosslinking strategies of biomedical hydrogels. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; El-Husseiny, E.A.; Mady, L.H.; Amira, A.; Kazumi, S.; Tomohiko, Y.; Takashi, T.; Aimi, Y.; Mohamed, E.; Ryou, T. Smart/stimuli-responsive hydrogels: Cutting-edge platforms for tissue engineering and other biomedical applications. Mater. Today Bio. 2022, 13, 100186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collini, H.; Jackson, M.D. Zeta potential of crude oil in aqueous solution. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 320, 102962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Lotina, A.; Portela, R.; Baeza, P.; Alcolea-Rodriguez, V.; Villarroel, M.; Ávila, P. Zeta potential as a tool for functional materials development. Catal. Today. 2023, 423, 113862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Dai, Y.; Xia, F.; Zhang, X. Role of divalent metal ions in the function and application of hydrogels. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 135, 101622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Huang, G.; Li, L.; Zhan, X.; Zhang, J.; Shao, J.; Hong, S.; Pan, S.T. A Mg2+-light double crosslinked injectable alginate hydrogel promotes vascularized osteogenesis by establishing a Mg2+-enriched microenvironment. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.; Baleizão, C.; Farinha, J.P.S. Functional Films from Silica/Polymer Nanoparticles. Materials 2014, 7, 3881–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; Jiang, L.; Shi, M.; Yangab, Z.; Zhang, X. The modification mechanism and the effect of magnesium chloride on poly(vinyl alcohol) films. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 1602–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, L.R. Preparation and Hygroscopic Property of the Polyacrylamide/MgCl2 Hybrid Hydrogel. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 550, 904–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, C.A.; Gottfried, J.L.; De Lucia, F.C.; McNesby, K.L.; Miziolek, A.W. Laser-based detection methods of explosives. In Counterterrorist Detection Techniques of Explosives, 1st ed.; Yinon, J., Ed.; Elsevier Science B.V.: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Venkataraman, M.; Wiener, J.; Militky, J. Photoluminescence PCMs and Their Potential for Thermal Adaptive Textiles. In Multifunctional Phase Change Materials; Pielichowska, K., Pielichowski, K., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 255–277. [Google Scholar]

- Kunghatkar, R.G.; Barai, V.L.; Dhoble, S.J. Synthesis route dependent characterizations of CaMgP2O7: Gd3+ phosphor. Results Phys. 2019, 13, 102295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenth, J. Principles of Protein X-ray Crystallography, 3er ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: Groningen, Netherlands, 2007; pp. 1–326. [Google Scholar]

- Abazari, M.; Jamjah, R.; Bahri-Laleh, N.; Hanifpour, A. Synthesis and evaluation of a new three-metallic high-performance Ziegler–Natta catalyst for ethylene polymerization: Experimental and computational studies. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 7265–7280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abasi, C.Y.; Wankasi, D.; Dikio, E.D. Adsorption study of Lead(II) ions on poly(methyl methacrylate) waste material. Asian J. Chem. 2018, 30, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayalakshmi, K.; Ismayil; Hegde, S.; Ravindrachary, V.; Sanjeev, G.; Mazumdar, N.; Sindhoora, K.M.; Masti, S.P.; Murari, M.S. Methyl cellulose-based solid polymer electrolytes with dispersed zinc oxide nanoparticles: A promising candidate for battery applications. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2023, 173, 111119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumry, R.; Rajender, S. Enthalpy–entropy compensation phenomena in water solutions of proteins and small molecules: A ubiquitous property of water. Biopolymers 1970, 9, 1125–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, F.; Graziano, G. On enthalpy–entropy compensation characterizing processes in aqueous solution. Entropy 2025, 27, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgelin, R.; Colin, J.J. Entropy, enthalpy, and evolution: Adaptive trade-offs in protein binding thermodynamics. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2025, 94, 103080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvern Panalytical. Dissociation constant. Accurate kinetic measurement of binding events. Available online: https://www.malvernpanalytical.com/en/products/measurement-type/dissociation-constant (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Astolfi-Rosado, L.; Bordin-Vasconcelos, I.; Palma, M.S.; Frappier, V.; Josef-Najmanovich, R.; Santiago-Santos, D.; Augusto-Basso, L. The mode of action of recombinant Mycobacterium tuberculosis shikimate kinase: Kinetics and thermodynamics analyses. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

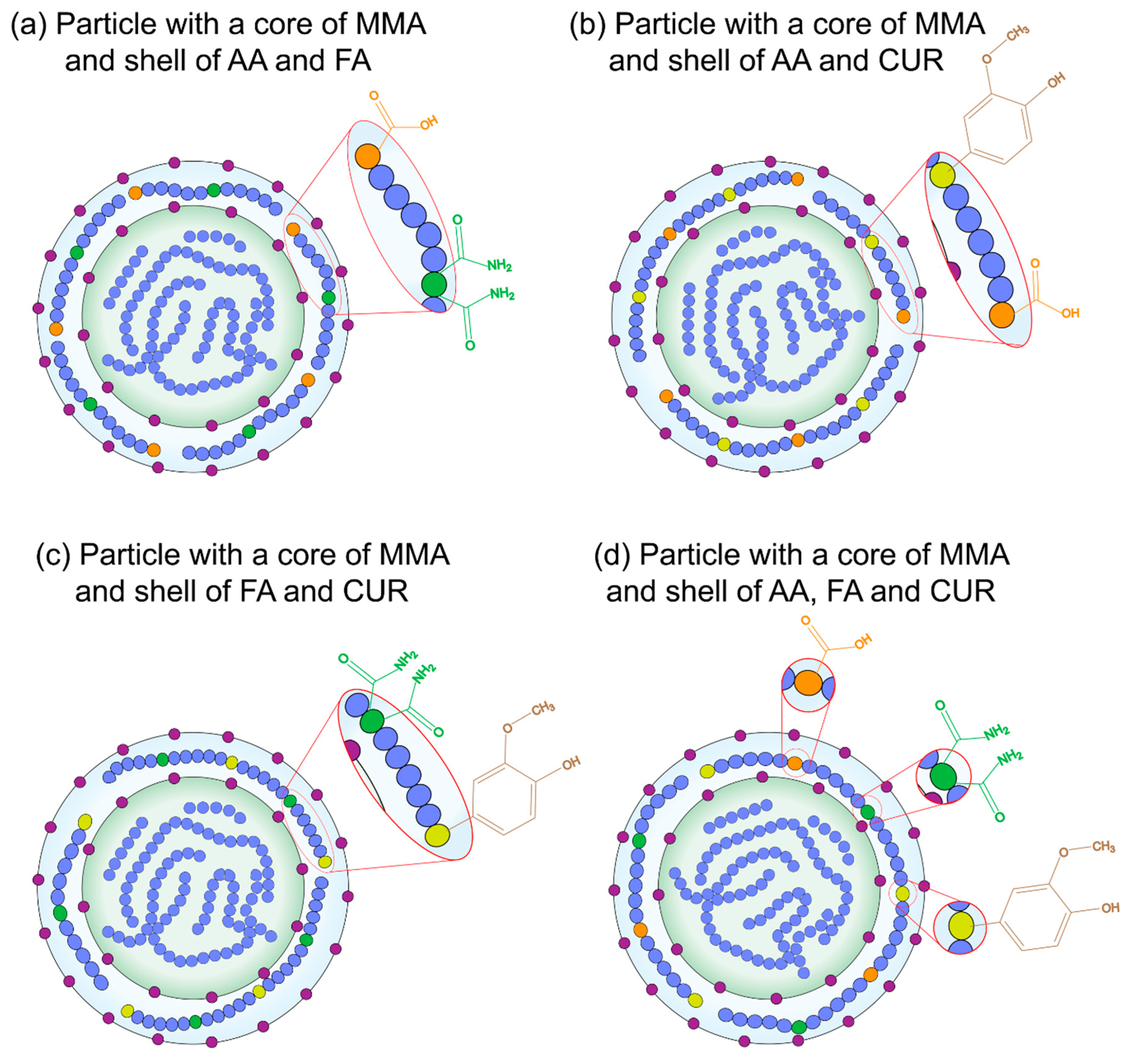

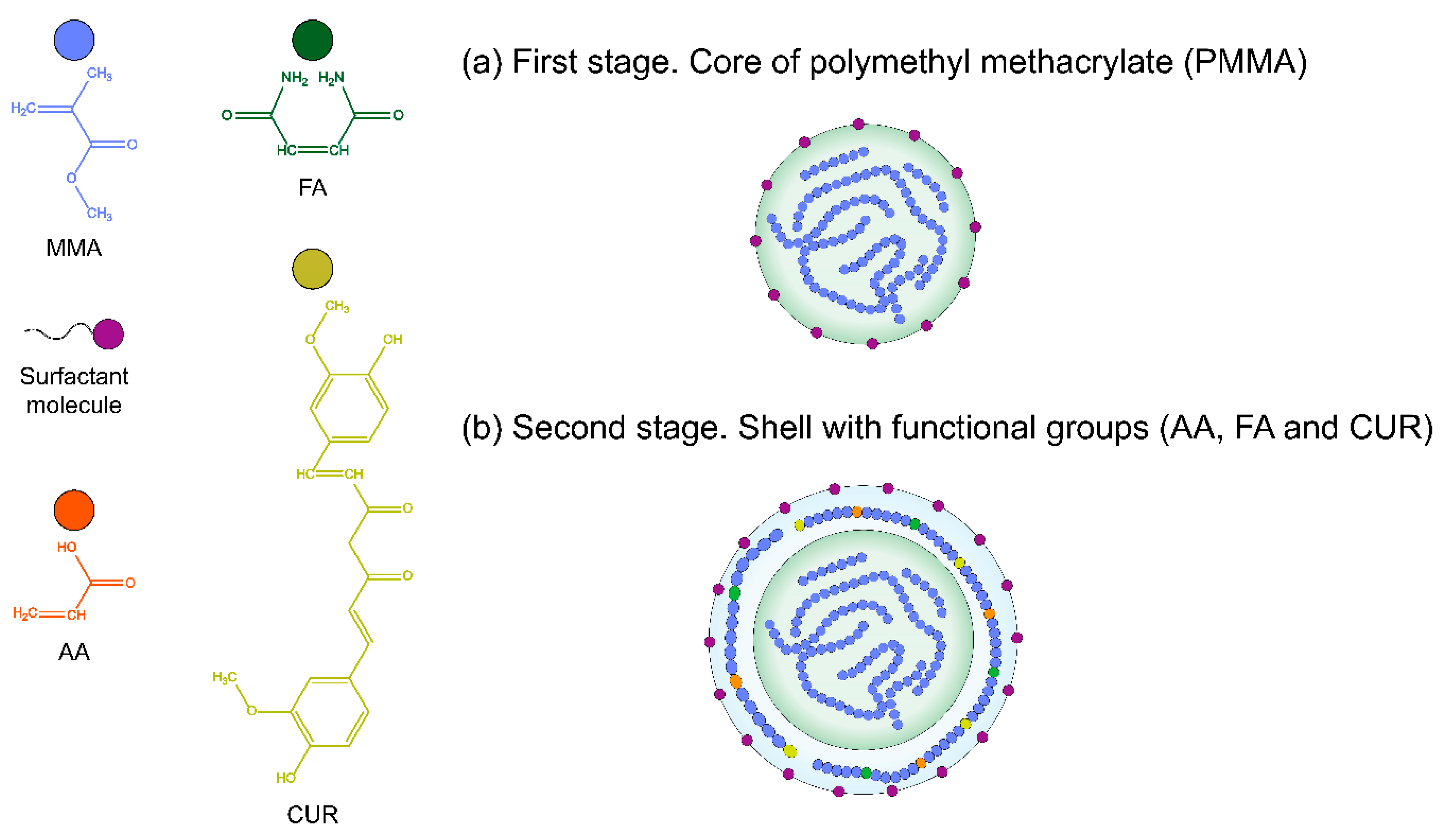

) methyl methacrylate MMA core and a shell of (

) methyl methacrylate MMA core and a shell of ( ) acrylic acid, AA; (

) acrylic acid, AA; ( ) fumaramide, FA and/or (

) fumaramide, FA and/or ( ) curcumin, CUR; respectively; where (

) curcumin, CUR; respectively; where ( ) is the surfactant molecules in the polymer chains.

) is the surfactant molecules in the polymer chains.

) methyl methacrylate MMA core and a shell of (

) methyl methacrylate MMA core and a shell of ( ) acrylic acid, AA; (

) acrylic acid, AA; ( ) fumaramide, FA and/or (

) fumaramide, FA and/or ( ) curcumin, CUR; respectively; where (

) curcumin, CUR; respectively; where ( ) is the surfactant molecules in the polymer chains.

) is the surfactant molecules in the polymer chains.

| Chemical name | CASRN | Source | Mass fraction purity |

| Methyl methacrylate (MMA) | 80-62-6 | Sigma–Aldrich, USA | ≥ 0.99a |

| Acrylic acid (AA) | 79-10-7 | Sigma–Aldrich, USA | ≥ 0.99a |

| Fumaramide (FA) | 627-64-5 | ChemCruz, USA | ≥ 0.96a |

| Curcumin (CUR) | 458-37-7 | Sigma–Aldrich, USA | ≥ 0.65b |

| Calcium chloride (CaCl2) | 10043-52-4 | Sigma–Aldrich, USA | ≥ 0.97a |

| Magnesium chloride (MgCl2) | 676-58-4 | Sigma–Aldrich, USA | ≥ 0.98a |

| Sodium persulfate (Na2S2O8) | 7775-27-1 | Sigma–Aldrich, USA | ≥ 0.98a |

| Nonylphenol ethoxylate ammonium sulfate (Abex® EP 120) | 7732-18-5 | Solvay, USA | —b |

| Double-distilled water (H2O) | — | Mizu Técnica, Mexico | —b |

| Reagents | Reactor (g) | Tank 1 (g) | Tank 2 (g) | ||

| 1 wt.% | 3 wt.% | 5 wt.% | |||

| Surfactant solution, 0.5 wt.% | 0.15 | - | - | - | - |

| Surfactant solution, 3.73 wt.% | - | 2.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Methyl methacrylate (MMA) | - | 6.9 | 3 | 2.8 | 2.6 |

| Acrylic acid (AA) | - | - | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| Fumaramide (FA) | - | - | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| Curcumin (CUR) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Initiator solution, 2 wt.% | 0.3 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Distilled water | 85 | 70 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Total solids content, (wt.%) | |||

| Material | 1 wt.% | 3 wt.% | 5 wt.% |

| Poly(AA:FA) | 4.16 ± 0.0002 | 4.58 ± 0.0006 | 4.38 ± 0.0002 |

| Poly(AA:CUR) | 4.46 ± 0.0006 | 4.27 ± 0.00008 | 3.31 ± 0.00003 |

| Poly(FA:CUR) | 4.45 ± 0.0006 | 5.15 ± 0.002 | 3.64 ± 0.0003 |

| Poly(AA:FA:CUR) | 4.48 ± 0.0002 | 4.25 ± 0.00005 | 4.26 ± 0.0001 |

| Average particle diameter, (nm) and polydispersity index, PDI | ||||||

| Material | 1 wt.% | 3 wt.% | 5 wt.% | |||

| (nm) | PDI | (nm) | PDI | (nm) | PDI | |

| Poly(AA:FA) | 108.9 ± 3.30 | 1.15 | 101.2 ± 0.522 | 1.10 | 121.1 ± 1.82 | 1.10 |

| Poly(AA:CUR) | 151.8 ± 1.80 | 1.12 | 133.0 ± 1.93 | 1.13 | 124.8 ± 0.817 | 1.11 |

| Poly(FA:CUR) | 151.4 ± 1.89 | 1.12 | 112.8 ± 1.63 | 1.11 | 121.1 ± 1.44 | 1.11 |

| Poly(AA:FA:CUR) | 128.2 ± 1.21 | 1.11 | 132.2 ± 1.53 | 1.12 | 123.3 ± 0.825 | 1.11 |

| pH | ||||||

| Material | 1 wt.% | 3 wt.% | 5 wt.% | |||

| Initial | Final | Initial | Final | Initial | Final | |

| Poly(AA:FA) | 2.6 ± 0.014 | 4.9 ± 1.1 | 2.5 ± 0.035 | 4.1 ± 0.19 | 2.6 ± 0.0071 | 4.3 ± 0.28 |

| Poly(AA:CUR) | 2.6 ± 0.000 | 3.8 ± 0.21 | 2.6 ± 0.000 | 3.8 ± 0.000 | 2.7 ± 0.0071 | 3.9 ± 0.11 |

| Poly(FA:CUR) | 2.5 ± 0.0071 | 3.8 ± 0.064 | 2.5 ± 0.0071 | 3.8 ± 0.18 | 2.7 ± 0.0071 | 4.2 ± 0.099 |

| Poly(AA:FA:CUR) | 2.7 ± 0.014 | 3.8 ± 0.078 | 2.4 ± 0.049 | 3.7 ± 0.021 | 2.7 ± 0.014 | 3.9 ± 0.078 |

| Miller indices (hkl) associated with 2θ values in cubic crystal systems | |||||

| 2θ (°) |

Calculated dhkl (Å) |

1 / d2 (Å-2) |

1/d2/0.09366 (Å-2) |

Common Factor (CF) divided by 0.03122 |

Calculated (hkl) |

| 27.26 | 3.268 | 0.09366 | 1.000 | 3.000 | 111 |

| 31.56 | 2.831 | 0.1247 | 1.332 | 3.995 | 200 |

| 45.36 | 1.997 | 0.2508 | 2.677 | 8.032 | 220 |

| 54.06 | 1.694 | 0.3483 | 3.719 | 11.16 | 311 |

| 56.38 | 1.630 | 0.3764 | 4.019 | 12.06 | 222 |

| 66.14 | 1.411 | 0.5022 | 5.362 | 16.09 | 400 |

| 75.16 | 1.263 | 0.6273 | 6.698 | 20.09 | 420 |

| Miller indices (hkl) associated with 2θ values in hexagonal close-packed systems | |||||

| 2θ (°) |

Calculated dhkl (Å) |

1 / d2 (Å-2) |

1/d2/0.1264 (Å-2) |

(h k l) |

Calculated dhkl (Å) |

| 31.78 | 2.812 | 0.1264 | 1.000 | 100 | 2.812 |

| 45.52 | 1.990 | 0.2524 | 1.997 | 001 | 1.990 |

| 56.56 | 1.625 | 0.3786 | 2.994 | 110 | 1.624 |

| 66.24 | 1.409 | 0.5035 | 3.983 | 200 | 1.406 |

| 75.34 | 1.260 | 0.6299 | 4.982 | 111 | 1.258 |

| System | n |

Kb (M-1) |

ΔG (kJ mol-1) |

ΔH (kJ mol-1) |

TΔS (kJ mol-1) |

| AA – CaCl2 | 0.1× 10-1 | 4.9 × 10 | -9.66 | -109 | -99.2 |

| FA – CaCl2 | 1.0 × 101 | 1.25 × 102 | -12.0 | -0.96 | 11.0 |

| CUR – CaCl2 | 8.7 × 10-3 | 3.9 × 102 | -13.8 | -335 | -321 |

| AA – MgCl2 | 18.7 × 10-1 | 1.73 × 102 | -7.07 | -3.56 | 3.51 |

| FA – MgCl2 | 14.1 × 10-1 | 2.27 × 10 | -7.75 | -15.5 | -7.73 |

| CUR – MgCl2 | 3.39 × 10-1 | 2.98 × 102 | -12.6 | -15.6 | -3.02 |

| Zeta potential,ζ (mV) | |||

| Material | 1 wt.% | 3 wt.% | 5 wt.% |

| Poly(AA:FA) | – 38.7 ± 0.606 | – 33.7 ± 0.130 | – 43.8 ± 0.296 |

| Poly(AA:CUR) | – 35.5 ± 0.435 | – 30.1 ± 0.730 | – 27.0 ± 0.224 |

| Poly(FA:CUR) | – 34.0 ± 1.00 | – 32.4 ± 1.38 | – 33.3 ± 0.482 |

| Poly(AA:FA:CUR) | – 35.1 ± 0.820 | – 41.5 ± 2.41 | – 32.9 ± 1.52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).