1. Introduction

Collagen is the most abundant structural protein in the human body. It is made up of approximately 1000 amino acids which may be released either individually or in the form peptides through enzymatic hydrolysis to produce bioactive peptides. These compounds possess a wide array of biological activities including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties [

1]. Collagen hydrolysates (CH) or collagen peptides have been produced from a variety of sources including bovine hides and bones, porcine skin, eggshells, and other byproducts from terrestrial animals. However, in recent years, there has been an increasing interest in producing collagen and CH from marine sources due their health benefits as well as the increasing availability of commercial products focused on specific market segments [

2,

3]. In this regard, fish farming offers important advantages as a source of raw materials for collagen extraction since it offers a steady supply and uniform quality parameters.

Among the species currently being farmed in México,

Totoaba macdonaldi has gained importance in the last few years. This species is endemic to the Gulf of California in México and is considered an endangered species according to CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) [

4]. Totoaba was historically overfished for many years for its swim bladder (SB) and its meat and is still under strict surveillance in its natural fishing grounds. However, some farms have successfully produced significant quantities of Totoaba for the domestic market.

Commercial production of marine CH requires three stages: 1. Sample pretreatment to remove protein, fats, pigments, and other undesirable components; 2. Extraction, separation, and purification of collagen; and 3. Enzymatic hydrolysis to obtain the peptides which are then sterilized and dried. Thus, the process is lengthy and energy intensive. Several enzymes have been employed for the hydrolysis process, but bromelain has had the best results in terms of higher antioxidant and overall functional properties for industrial applications [

5]. Clearly, different processing treatments yield final peptides with considerably different amino acid sequences, molecular weights, and bioactive properties [

6,

7].

Previous reports have shown the effects of protein hydrolysates against different cancer cell lines, including breast cancer cells [

8]. Interestingly, recently Çevik et al. [

9] reported that proline-rich peptides, such as VPP (valine-proline-proline), induced cell death and restrained proliferation and migration in breast cancer cells, indicating their potential as therapeutic agents [

9]. Additionally, CH have been reported to have low toxicity to normal cells and produce no significant harmful side effects [

10,

11]. Also, CH have proven several beneficial effects on human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs), which are crucial for skin health and regeneration [

12].

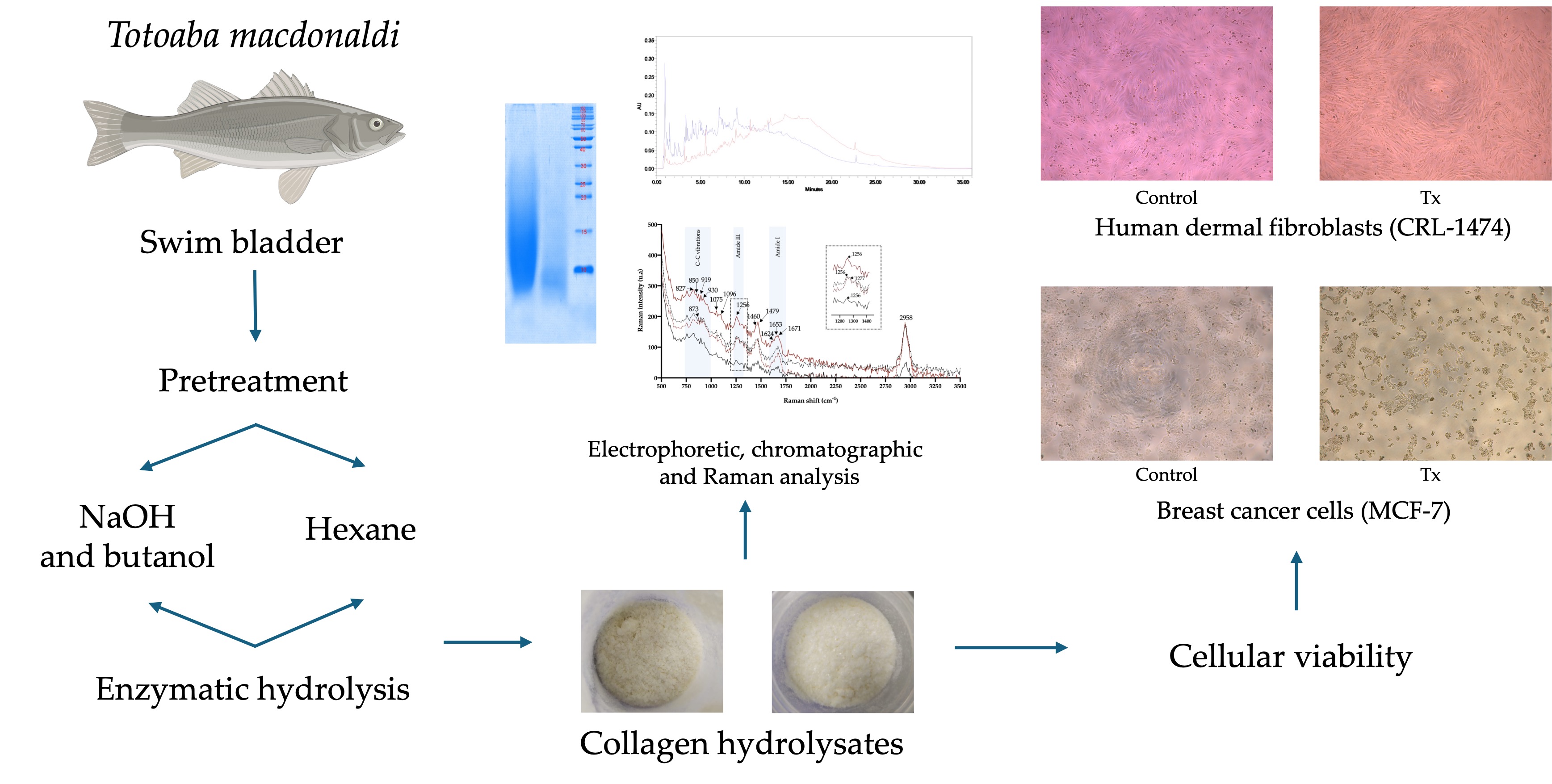

This work explored two pretreatment methods to process SB of

Totoaba macdonaldi: 1. Pretreatment with sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and defatting with butanol and 2. Defatting with hexane. After such treatments, direct hydrolysis was performed using bromelain.

Figure 1 shows the general procedure for producing CH. The CH produced through these processes were characterized and their biological activity on breast cancer cells and HDFs was assessed.

2. Results and Discussion

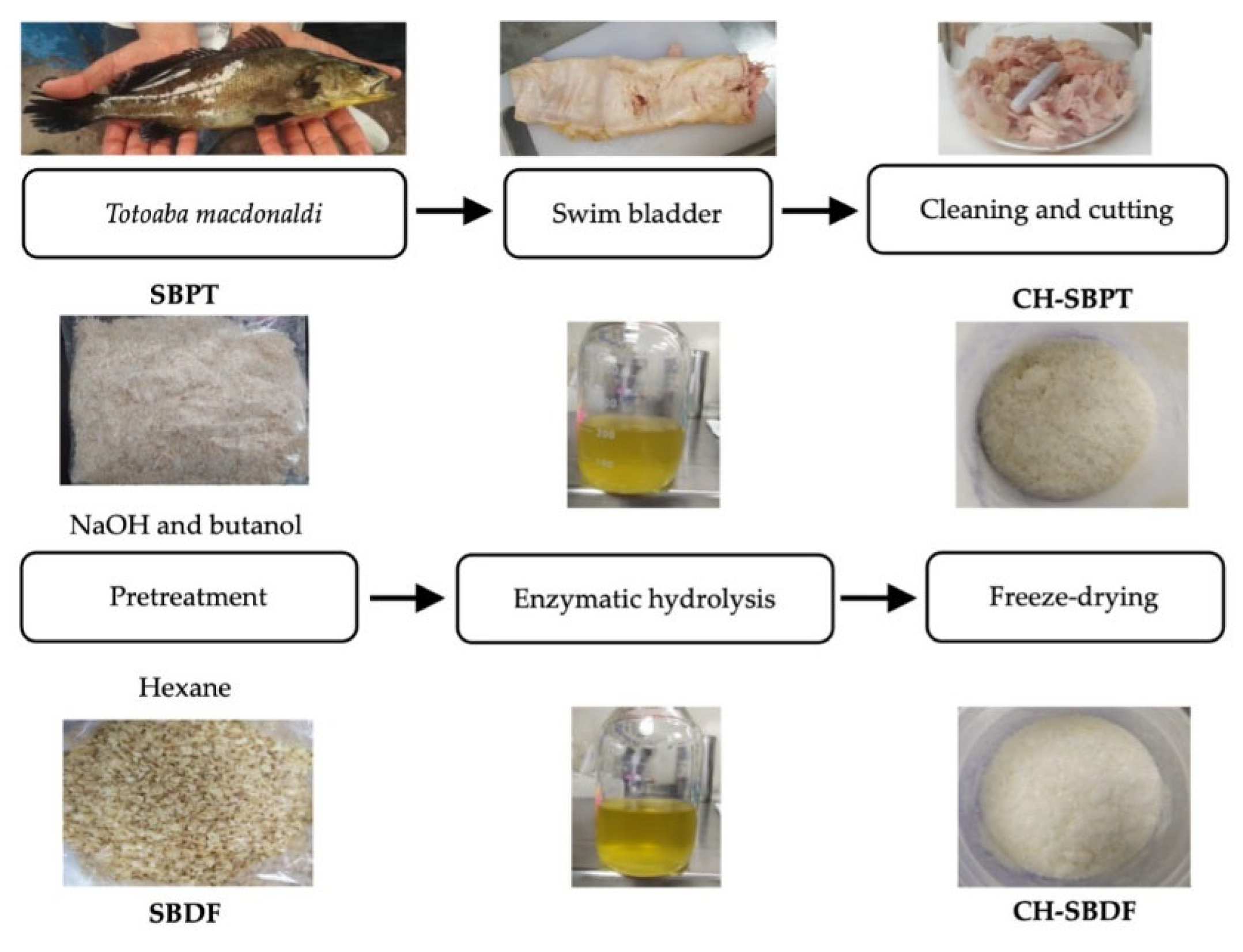

2.1. Pretreatment of Swim Bladders

The usual method to remove non-collagenous proteins is the use of NaOH. Its effectiveness depends on time, temperature and concentration [

13]. On the other hand, the removal of fats and pigments can be achieved using alcohols, namely butanol or ethanol. Thus, the pretreatment usually involves several washes with NaOH, followed by butanol fat extraction. This process can take anywhere from a few days to several weeks and requires multiple water washes to neutralize the pH of the sample at each stage. As an alternative to such pretreatment, in this work the SB was directly defatted using hexane and later hydrolyzed. This is less expensive and requires less processing time while producing the same yield (

Table 1).

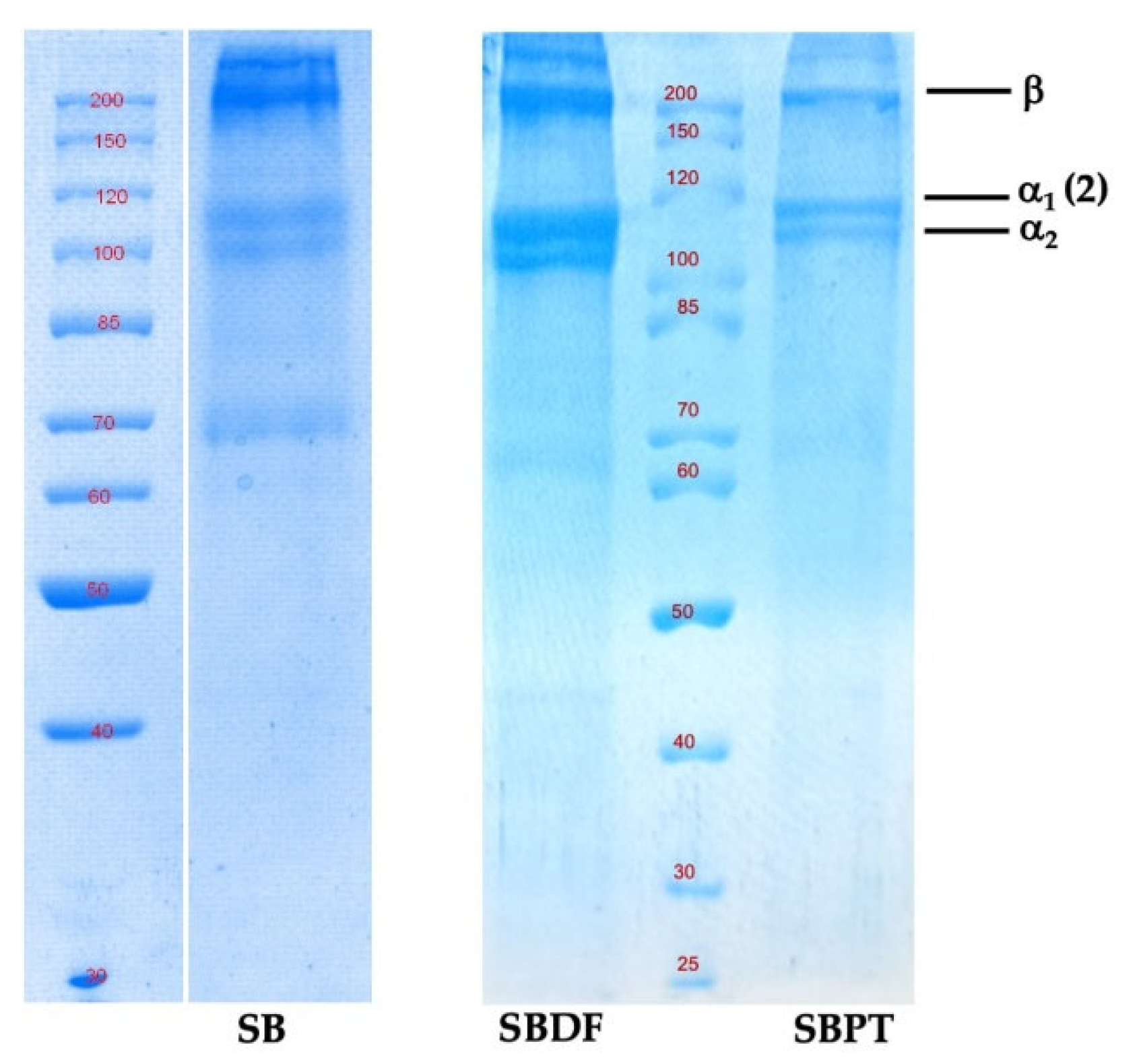

2.2. Electrophoretic Analysis of Pretreated Samples and Swim Bladder

The SDS-PAGE analysis showed that the SB of Totoaba samples subjected to the two extraction conditions displayed at least two different α bands and a β dimer (α

1, α

2, β), which suggests that it is a Type 1 collagen, a heterotrimer containing two identical α

1-chains and one α

2-chain in the molecular form of [α

1(I)]

2α

2(I). The two bands of the α

1 and α

2 chains occur in a 2:1 ratio, with molecular weight of α

1 and α

2 of approximately 118 kDa and 108 kDa, respectively.

Figure 2 shows the electrophoretic analysis of the two pretreated SB samples (SBPT and SBDF) and a total protein extract in RIPA buffer of the SB tissue before pretreatment. The patterns of the two α chains and one β dimer of SB with different pretreatment and SB before pretreatment were similar. Therefore, the conditions of pretreatment did not affect the native collagen structure. A previous study showed that pepsin-soluble collagen from SB of Totoaba was a type I collagen with α

1 and α

2 chains and a β dimer, in which the molecular weight of α

1 and α

2 was approximately 126 kDa and 116 kDa, respectively [

14]. These differences may be attributed to the growth conditions of the totoabas. In the study conducted by Cruz-López et al. [

14] the authors used SB from 3-year-old farmed totoaba cultivated under controlled conditions at the Wildlife Conservation Management Units (UMA, Unidad de Manejo Ambiental) of the Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Mexico. On the other hand, the totoabas used in this study were cultivated in the open sea in anchored cages.

2.3. Collagen Hydrolysates Yield

Following the pretreatment of the SB samples with NaOH-butanol and hexane, we proceeded directly to the enzymatic hydrolysis process using bromelain, bypassing the collagen extraction stage. Typically, the conventional method to prepare hydrolyzed collagen involves three steps: 1. Pretreatment to remove protein, fats, pigments, and other undesirable components; 2. Extraction, separation, and purification of collagen; and 3. Enzymatic hydrolysis. The extraction of collagen is usually performed with acetic acid and could take several days, and results in low yields [

15].

In this work, we observed the electrophoretic profile of the samples (

Figure 2) after both pretreatments. The profiles showed that the most abundant bands were of collagen, leading us to choose the direct enzymatic hydrolysis process with bromelain. This approach enabled a faster process and resulted in a high yield of hydrolysates. Bromelain is a plant protease with high specificity widely employed in the food industry and it has been used effectively for the hydrolysis of collagen and the production of peptides with high biological activity [

5,

16]. In this work, hydrolysis yields were 81 and 81% for CH-SBPT and CH-SBDF respectively, indicating that the type of pretreatment did not significantly impact the yield.

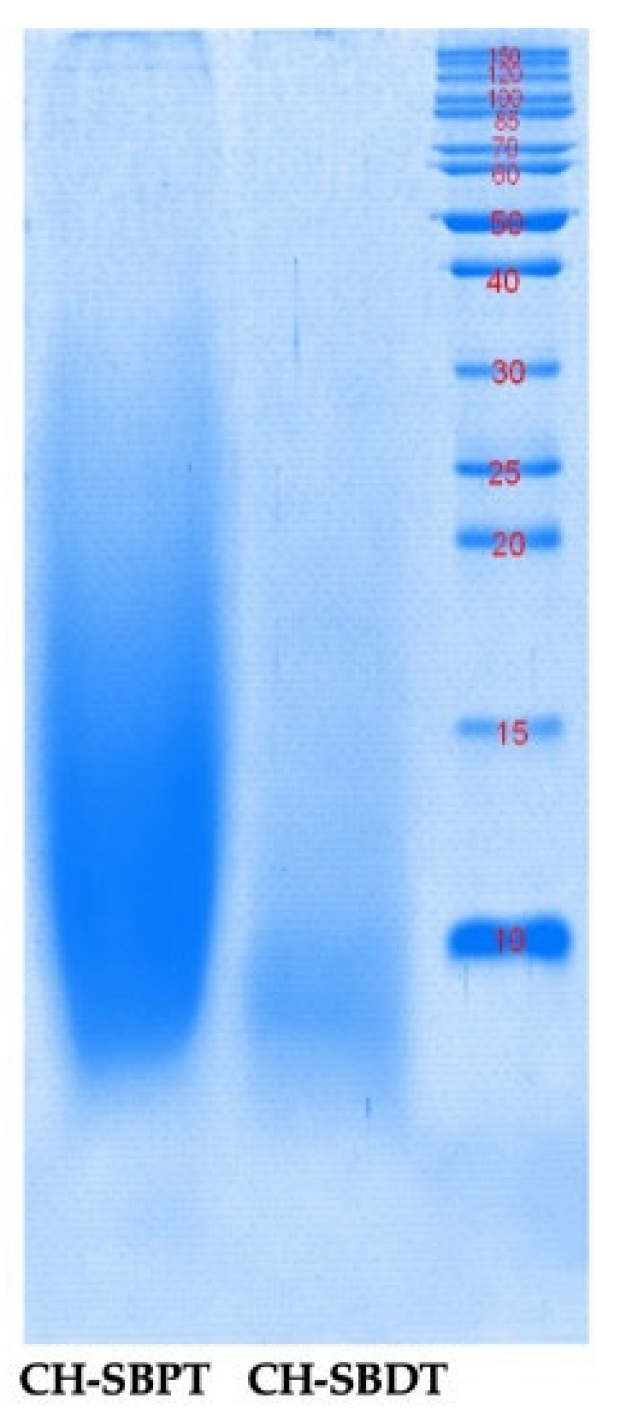

2.4. Electrophoretic Analysis of Collagen Hydrolysates

The CH-SBPT yielded molecular weights below 20 kDa while most of the CH-SBDF had lower than 10 kDa (

Figure 3). In both treatments, the same temperature and time combinations were used but there was a small difference in the pH of the initial solution. In the case of the SBPT the pH was 6.59 while in the SBDF it was 5.38. According to the scientific literature, bromelain is active at a pH range from 3 to 8 with an optimum value at 5 [

16,

17]. In this work it was decided to work with the resulting pHs in the mixture of SB in water since they were in the range of high enzyme activity. This approach avoided the formation of salts if neutralization was to be carried out and a subsequent dialysis as well. It is worth noting that the differences in the final pHs in the SBPT and SBDF mixtures could be attributed to the pretreatment process used. As described in the methods section, in the first case NaOH/butanol was used while for the SBDF only hexane was used for defatting. In the first case, NaOH traces may have contributed to the slight pH increase. As noted above, the CH-SBDF had a lower molecular weight than those of the CH-SBPT. This could be because the pH was closer to the optimum level for bromelain enzyme activity (pH value of 5) [

16]. The pH value significantly influences not only enzyme activity but also the stability of collagen molecules. This relationship, in turn, impacts the susceptibility of peptide bonds to enzymatic cleavage [

18,

19].

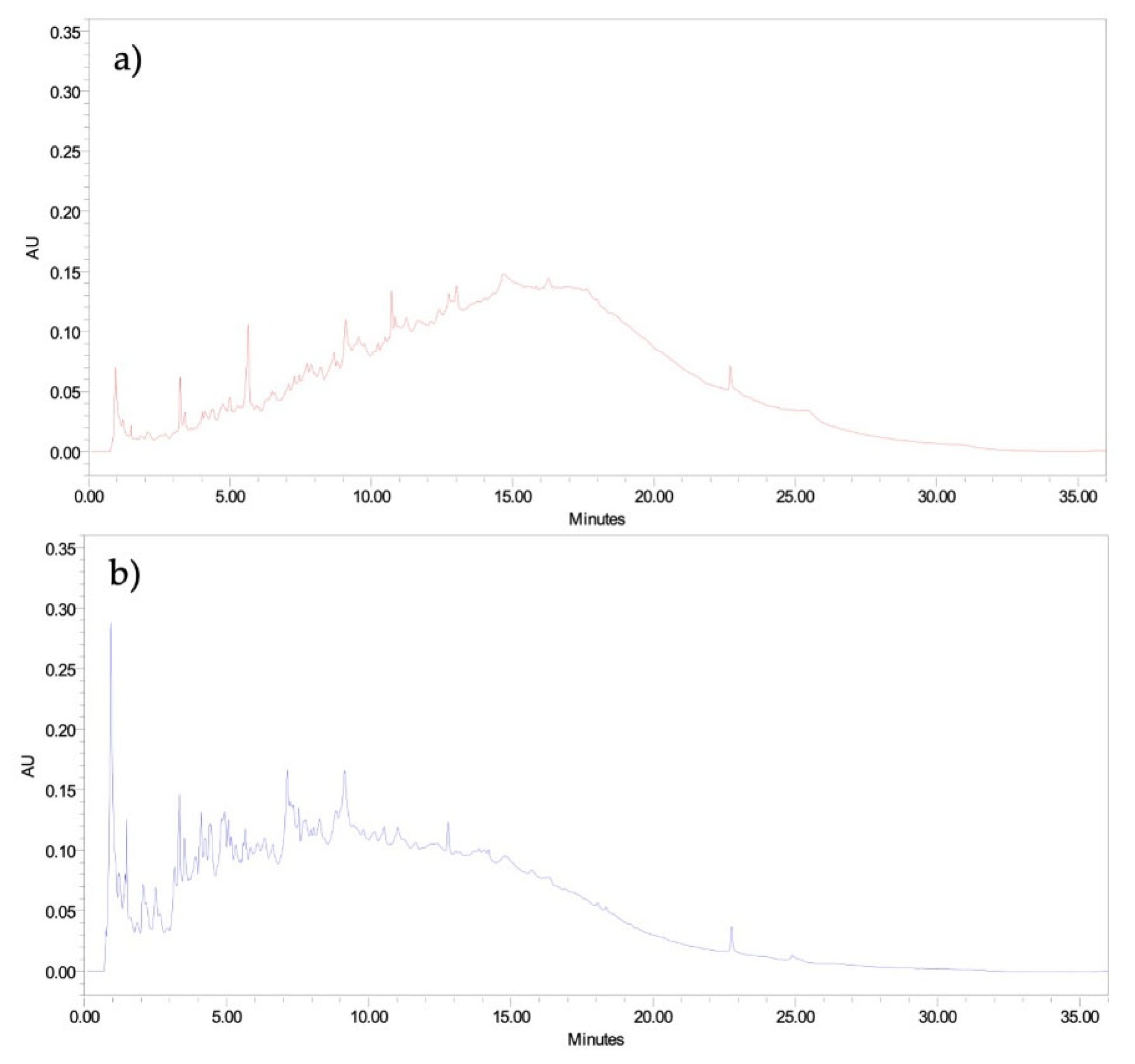

2.5. Chromatographic Profile of Collagen Hydrolysates

As observed from the electrophoretic pattern of the CH, there is a different chromatographic profile for the two CH samples. The chromatographic profile of the CH produced from SB showed that CH-SBDF has a higher number of peaks eluted from 0 to 10 minutes than those from CH-SBPT, so the peptides from CH-SBDF are more hydrophilic than those from CH-SBPT (

Figure 4). The hydrolysis process revealed ionizable amino acids and carboxyl group residues, which interact with water molecules to form hydrogen bonds, thereby enhancing solubility [

20].

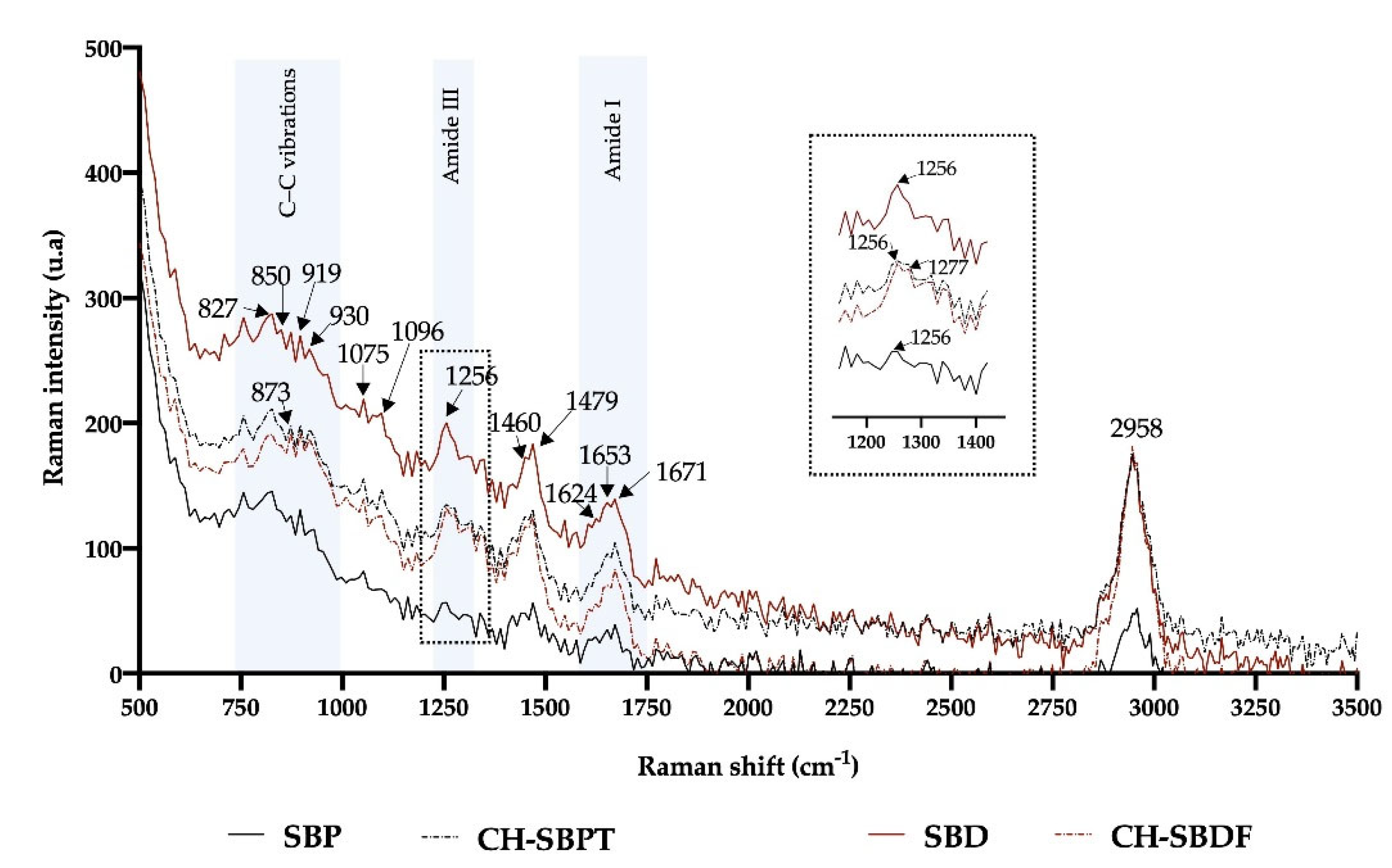

2.6. Raman Analysis

Raman spectroscopy was used because it offers valuable chemical insights while avoiding the need of a complex sample processing [

21].

Figure 5 shows the Raman spectra of the SBPT, SBDF, CH-SBPT and CH-SBDF along with the Raman bands signals. In the protein Raman spectra, the C–C and C–N vibrational bands in the polypeptide structure may be predominant because of the contribution of the COO

–, NH

3+ and OH

– functional groups.

Generally, the stretch vibration of amide I, amide III and C-C from collagens are in the regions from 1620-1680, 1235-1280 and 764-980 respectively [

21,

22,

23]. The peaks at 850, 873 and 919 cm

−1 are attributed of the presence of proline (Pro) and hydroxyproline (Hyp) from collagen. The band of 1256 may be assigned to secondary structures of the collagen α-helix. The peak at 1460 cm

−1 is often due to the movement of the protein CH

2 group. No significant changes were observed in the Raman spectra of the SB in the Amide I, Amide III and C-C regions. For the CH of the SB in the Amide III region a slight change was observed in the 1256 cm

−1 peak since a shoulder appears at 1277 cm

−1; this may reflect the conformational changes in the collagen secondary structure caused by the hydrolysis of the collagen peptide bonds.

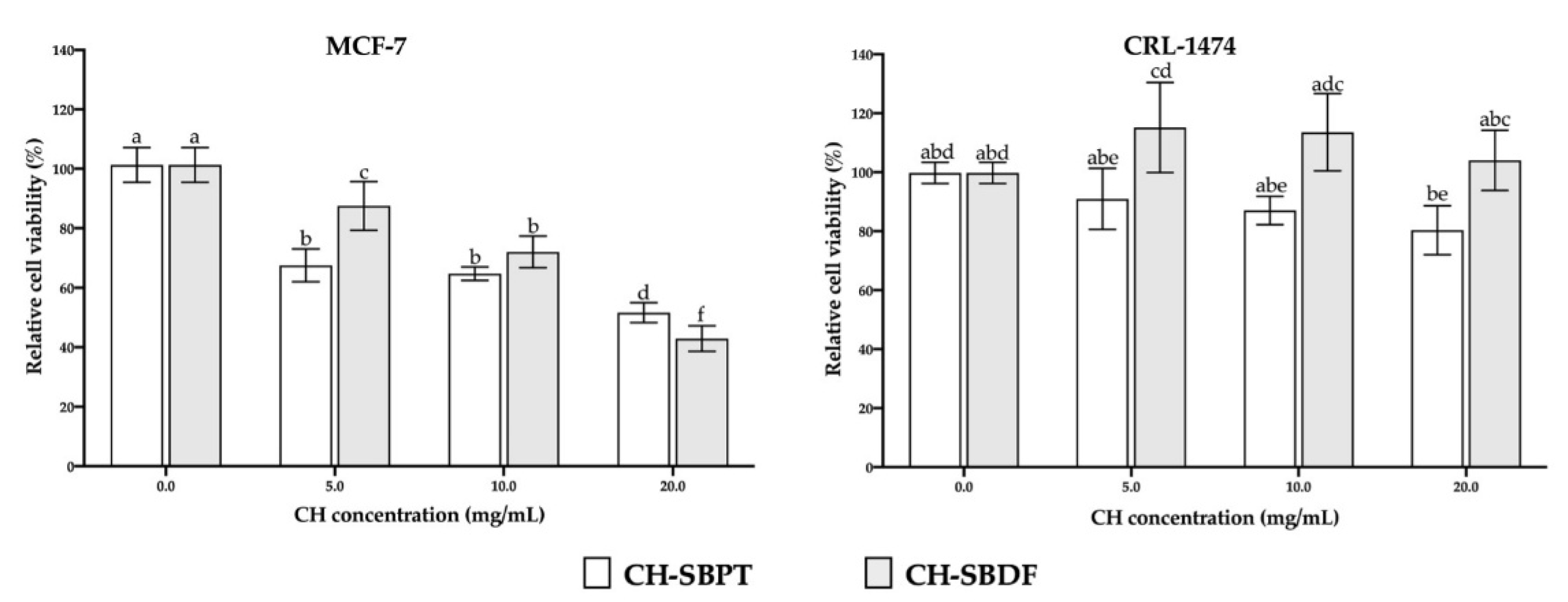

2.7. Cellular Viability Assay

There is great interest in the study of bioactive peptides isolated from various marine sources (sponges, tunicates, ascidians, mollusks, fish) with potential anticancer activity [

24]. Previous reports have shown the effects of protein hydrolysates on different cancer cell lines such as the U-937 of human lymphoma [

25]; HT1080 of human fibroid sarcoma, Hela of human cervix adenocarcinoma [

26]; MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells [

8], among others. It has also been reported that gelatin peptides from other animal species such as bovine, display activity against SKOV-3 human ovary carcinoma cells [

11].

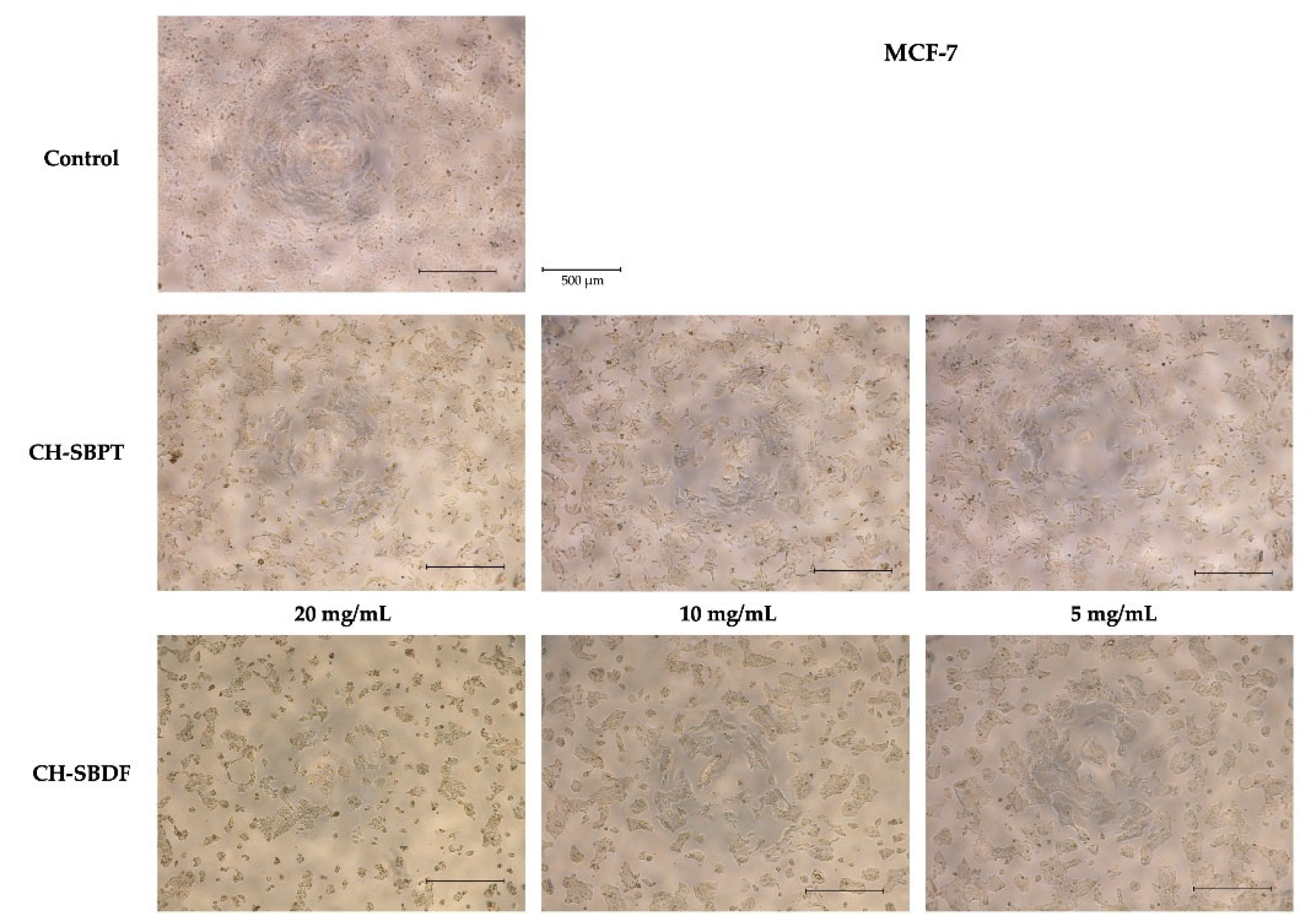

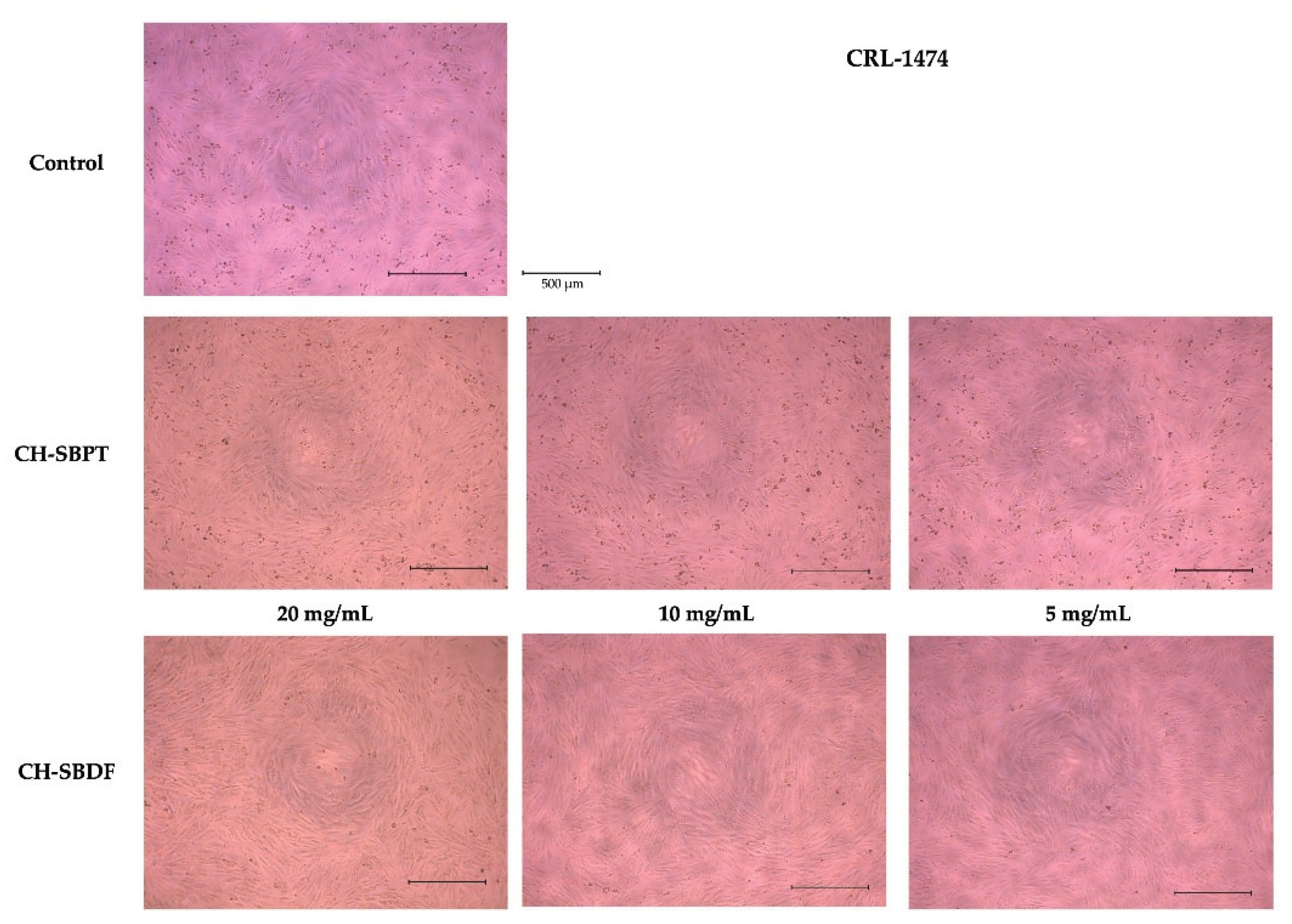

In this work, we report on the effect of CH from the Totoaba macdonaldi SB on breast cancer cells as well as their biocompatibility on non-malignat HDFs. Such hydrolyzates were assessed against the MCF-7 cell line at concentrations of 20, 15 and 10 mg/L. The concentrations studied of the two hydrolyzates produced an inhibition of cell viability which was significantly diferent from the control without treatment; nevertheless, the CH-SBDF showed a more consistent dose-response relationship since the concentration of 20 mg/mL presented a greater inihibition of cell viability as compared to the CH-SBPT (

Figure 6). This can be clearly seen in the micrographic images obtained at the end of the treatment where a lower cell density is observed for the CH-SBDF treatment at the concetration of 20 mg/mL compared to the untreated control. Changes in cell morphology can also be observed, i.e. decrease in size of cells and more compact cell clusters which may be indicative of cell death or apoptosis (

Figure 7).

Previous studies have reported that marine collagen peptides exhibit a range of bioactivities, making them promising candidates for various health and biomedical applications [

27,

28]. Indeed, some reports have informed about the ability of some SB collagen solutions to promote fibroblast viability [

15]. Such increase can accelerate the process of epithelial regeneration. In this work, the CH-SBPT presented only a slight inhibition of cell viability which was not significantly different from the control. On the other hand, the CH-SBDF displayed an increase in cell proliferation, particularly at a concentration of 5 mg/mL. For the remaining concentrations a small increase in cell viability was oberved but it was not statistically diferent from the control (

Figure 6). In the micrographs an increase in cell density can be observed in relation to the control, which is more evident for the CH-SBDF treatment (

Figure 8).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemical Reagents

Thiazolyl Blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT), Bromelain (B4882), phosphate buffered saline (PBS), Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), Ammonium Persulfate, β-Mercaptoethanol (β-Me), Tris base, glycine, Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) RIPA buffer, RMPI-1640, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium low glucose (DMEM), streptomycin-penicillin, trypsin 0.25% with EDTA, all were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. Coomassie blue G-250, 30% Acrylamide/Bis Solution 19:1 were purchased from BioRad Laboratories, Inc. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from Biowest USA Inc. All other reagents and solvents used were of analytical grade or better.

3.2. Swim Bladders Samples

Totoaba SB samples were provided by the Cygnus Ocean Farms company. This farm is located at the “La Manga” bay, San Carlos Nuevo Guaymas, Sonora, México (Latitude 27.9420° N, Longitude 111.0617° W). The SB were extracted from the fish under aseptic conditions, packed in polyethylene bags, and frozen and stored at -18°C until sent to the laboratory, where they were kept until processed. Before the pretreatment, the SB samples were cleaned manually to remove the blood vessels and fat and cut into small pieces (approximately 1 x 1 cm).

3.3. Total Protein Extract of the Swim Bladder in RIPA Buffer

Ten milligrams of SB tissue were suspended in 500 μL of RIPA and sonicated for 15 min. RIPA total protein extraction lysis buffer is a traditional lysate of cell and tissue protein extraction.

3.4. Pretreatment with NaOH and Defatting with Butanol

Treatment with NaOH is the most common process to remove non-collagenous proteins from raw material. The pretreatment was performed following the methodology described by Cruz-López et al. [

14] with slight modifications. 800 g of SB were submerged in a 0.1 M NaOH solution, kept at a 1:20 ratio (

w/v). The mixture was continuously stirred for 12 h a 4

oC, and the alkali solution was changed every 4 h. The treated SB was then washed with distilled water until all the alkaline solution was eliminated. Subsequently, the tissue was defatted with a 15% butanol solution in H

2O at a 1:20 ratio (

w/v) for 12 h a 4

oC, and for every 4 h, the butanol was replenished. The defatted sample was washed with distilled water several times and submerged in distilled water over night. Finally, the sample was freeze-dried and ground. This sample was labeled as SBPT and was further used for preparation of hydrolysates.

3.5. Straight Defatting with Hexane

A total of 500 g of SB was freeze-dried, then submerged in hexane for defatting, using a 1:3 ratio (w/v). The mixture was continuously stirred for 24 h at 22oC, and for every 8 h, the hexane was replenished. Subsequently, the extracted SB were filtered to remove excess hexane, and the residual hexane was removed evaporation. Finally, the sample was labeled as SBDF and used for the preparation of hydrolysates.

3.6. Electrophoretic Analysis

The molecular weight and type of collagen were determined by using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Electrophoretic patterns were determined according to Laemmli [

29] with slight modifications, using 8% separating gel and 4% staking gel for SB tissue in RIPA and SB sample pretreatment (SBPT and SBDF); and using 15% separating gel and 6% staking gel for CH-SBPT and CH-SBDF. The samples (10 mL) were mixed with the sample loading buffer at a 1:1 ratio (v/v) in the presence of β-Me and incubated at 95

oC for 5 min. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained in Coomassie blue G-250. A protein ladder marker of 10 kDa to 210 kDa (PageRuler

TM, Thermo Scientific) was used to estimate the molecular weight of collagen. The protein bands were visualized by the Image Lab Software (BIORAD Laboratories, Inc.).

3.7. Direct Hydrolysis with Bromelain

The enzymatic hydrolysis of SBPT and SBDF was prepared by mixing samples in ultrapure water at a 1:20 ratio (w/v) and adding 100 mg of bromalin enzyme for every 100 mL of solution. The pH of the SBPT mixture was 6.59 and for SBDF it was 5.38. The mixture was homogenized and hydrolyzed in a water bath using ultrasound at 50oC for 3 hours. Then, the enzyme was inactivated by heating the mixture at 95oC for 10 min, and later cooled and centrifuged at 7,000 rpm at 4oC for 20 min. The resulting supernatant was a hydrolysate. The samples were freeze-dried and labeled as CH-SBPT and CH-SBDF, respectively.

3.8. Chromatographic Profile of Hydrolyzed Collagens

Chromatographic profile of CH was performed using an Acquity Ultra Performance LC (Liquid chromatography) system with TUV Detector (Waters Inc.). Briefly, 10 μL of each CH (10 mg/mL) were directly injected into a C18 Column (1.6 μm, 2.1 x 100 mm). CH were eluted using water as mobile phase A and acetonitrile as mobile phase B. An elution gradient was performed as follows: 0-5 min, 100% to 95% B; 5-10 min, 95% to 90% B; 10-15 min, 90% to 85% B; 15-20 min, 85% to 80% B; 20-25 min, 80% to 75% B; 25-30 min, 75% to 70% B; 30-35 min, 70% to 100% B; 36 min, 100% B. Total run time was 36 min with a 0.3 mL/min flow rate. Column temperature was set at 37 o C and UV detection done at 215 nm.

3.9. Raman Analysis

Raman measurements were obtained in the range of 90 - 3100 cm-1, using a laser with a wavelength of 1064 nm and an output power of 800 mW as the excitation source (Ocean Optic Inc. Dunedin, FL).

3.10. Cellular Viability Assay

The MCF-7 (human breast cancer) cells were cultured in RMPI-1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 0.5% streptomycin-penicillin. The CRL-1474 cells (normal human dermal fibroblast) were cultured in DMEM–low glucose supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 0.5% streptomycin-penicillin. All line cells were cultured at 37

oC in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere in their growth media. Cell viability assay was evaluated using MTT assay with slight modifications [

30]. The cells were placed into 96-well microtiter plates at 1 x 10

4 each well and cultured for 24 h. Then, the medium was removed and substituted with 200 μL of medium-free FBS containing different concentrations (20, 10, 5 y 2.5 mg/mL) of CH-SBPT and CH-SBDF. The hydrolysates were exposed over 48 h. Controls consisted of untreated cells and incubated using the same conditions as treated cells. Then, 20 μL/well of MTT at 5 mg/mL were added, and the plates were returned to the incubation for 3.5 h. Afterwards, the 150 μL MTT solution was removed and 150 μL of DMSO:isopropanol was added. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm together with a reference of 690 nm using a microplate reader (Cytation 3 CYT3M, BioTek Instruments, Inc.). All experiments were carried out in triplicates and the cells were observed and photographed under an inverted microscope with a 5× objective lens (Leica, DMi1).

3.11. Statistical Analysis

The software Graphpad Prism (Boston, MA) was used to conduct statistical analysis. Two-way ANOVA was used to compare test groups to control groups. Data were presented as means ± SEM and the statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

4. Conclusions

This investigation shows that the pretreatment of the Totoaba macdonaldi SB with hexane can yield equal amounts of collagen-derived peptides, thus avoiding the protein extraction step with NaOH. Additionally, no differences were observed in the electrophoretic patterns of the native collagen structure between the two pretreatment methods. The enzymatic hydrolysis process was conducted directly using bromelain. The hydrolysis was verified through the SDS-PAGE, Raman spectroscopy, and chromatographic profile. CH from both pretreatments exhibited significant bioactivity against the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line, with a concentration of 20 mg/mL being the most effective for the CH-SBDF peptides.

This effect could be related to the lower molecular weight and higher hydrophilicity of such peptides, conferring them a more efficient penetration into the cells. On the other hand, peptides from both pretreatments stimulated the growth and proliferation of HDFs, thus showing their beneficial effect on normal human cells. Further research is needed to isolate and characterize the specific peptides responsible for such promising effects as well as to identify the molecular mechanisms involved.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.-B. and I.H.-C.; methodology, E.M.-B., A.M.V.-P., J.C.-M., J.L.P.-S., S.B.D., O.Y.L.-M., and H.S.G.; formal analysis, E.M.-B., A.M.V.-P., and I.H.-C; investigation, E.M.-B, A.M.V.-P., O.Y.L.-M., H.S.G., I.H.-C.; resources E.M.-B and I.H.-C; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.-B and I.H.-C.; writing—review and editing, E.M.-B., A.M.V.-P., J.C.-M., O.Y.L.-M., H.S.G., and I.H.-C.; supervision, E.M.-B. and I.H.-C.; project administration, E.M.-B., H.S.G and I.H.-C.; funding acquisition E.M.-B. and I.H.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Cygnus Ocean Farms for providing the Totoaba swim bladder samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CH |

Collagen hydrolysates |

| SB |

Swim bladder |

| SBPT |

Swim bladder pretreatment with NaOH and butanol |

| SBDF |

Swim bladder defatting with hexane |

| CH-SBPT |

Collagen hydrolysates from swim bladder pretreatment with NaOH and butanol |

| CH-SBDF |

Collagen hydrolysates from swim bladder defatting with hexane |

| CITES |

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora |

| NaOH |

Sodium hydroxide |

| HDFs |

Human dermal fibroblasts |

| MTT |

Thiazolyl Blue tetrazolium bromide |

| PBS |

phosphate buffered saline |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| SDS |

Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium low glucose |

| FBS |

Fetal bovine serum |

| SDS-PAGE |

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| LC |

Liquid chromatography |

References

- Nuñez, S.M.; Guzmán, F.; Valencia, P.L.; Almonacid, S.; Cárdenas, C. Collagen as a source of bioactive peptides: a bioinformatics approach. Electron J Biotechnol. 2020, 48, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felician, F.F.; Yu, R.H.; Li, M.Z.; Li, C.J.; Chen, H.Q.; Jiang, Y.; Tang, T.; Qi, W.Y.; Xu, H.M. The wound healing potential of collagen peptides derived from the jellyfish Rhopilema esculemtum. Chin J Traumatol. 2019, 22, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, H.; Lestre, G.M.; Solstad, R.G.; Cabral, A.E.; Botelho, A.; Helbig, C.; Coppola, D.; De Pascale, D.; Robbens, J.; Raes, K.; Lian, K.; Tsirtsidou, K.; Leal, M.C.; Scheers, N.; Calado, R.; Corticeiro, S.; Rasche, S.; Altintzoglou, T.; Zou, Y.; Lillebø, A.I. Current and expected trends for the marine chitin/chitosan and collagen value chains. Mar Drugs. 2023, 21, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CITES https://cites.org/eng/node/48556.

- Coscueta, E.R.; Brassesco, M.E.; Pintado, M. Collagen-Based bioactive bromelain hydrolysate from Salt-Cured cod Skin. Appl Sci. 2021, 11, 8538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Pino, F. Bioactive food-derived peptides for functional nutrition: effect of fortification, processing and storage on peptide stability and bioactivity within food matrices. Food Chem. 2023, 406, 135046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, N.T.P.; Hsu, J.L. Bioactive peptides: an understanding from current screening methodology. Processes. 2022, 10, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picot, L.; Bordenave, S.; Didelot, S.; Fruitier, A.I.; Sannier, F.; Thorkelsson, G.; Bergé, J.P.; Guérard, F.; Chabeaud, A.; Piot, J.M. Antiproliferative activity of fish protein hydrolysates on human breast cancer cell lines. Process Biochemistry. 2006, 41, 1217–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çevik, Z.B.Y.; Sönmez, B.B.; Karaman, O. Evaluation of the efficacy of proline rich VPPPVPPRRR Peptide (VPP) in MCF-7 cells. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2025, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Chia, C.H. Bioactive food peptides in health and disease. InTech Open. 2013, 278. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Tian, J.; Ping, H.; Sun, E.H.; Zhang, B.; Guo, Y. Peptides from bovine bone gelatin hydrolysate with anticancer activity against the human ovary carcinoma cell line and its possible mechanism. J Funct Foods. 2024, 114, 106061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zague, V.; do Amaral, J.B.; Teixeira, P.R.; Niero, E.L.O.; Lauand, C.; Machado-Santelli, G.M. Collagen peptides modulate the metabolism of extracellular matrix by human dermal fibroblasts derived from sun-protected and sun-exposed body sites. Cell Biol Int. 2017, 42, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.H.; Moreira-Silva, J.; Marques, A.L.P.; Domingues, A.; Bayon, Y.; Reis, R.L. Marine origin collagens and its potential applications. Mar Drugs. 2014, 12, 5881–5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-López, H.; Rodríguez Morales, S.; Enríquez Paredes, L.M.; Villareal Gómez, L.J.; True, C.; Olivera Castillo, L.; Fernández Velasco, D.A.; López, L.M. Swin bladder of Totoaba macdonaldi: a source of value-added collagen. Mar Drugs. 2023, 21, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Lv, J.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, J.; Lin, F.; Wen, X. Structural, physicochemical properties and function of swim bladder collagen in promoting fibroblasts viability and collagen synthesis. LWT. 2023, 173, 114294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cui, Y.; Wang, R.; Ma, J.; Sun, H.; Chen, L.; Yang, R. The hydrolysis of pigment-protein phycoerythrin by bromelain enhances the color stability. Foods. 2023, 12, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, P.; Nikhade, P.; Patel, A.; Mankar, N.; Sedani, S. Bromelain: A Potent Phytomedicine. Cureus. 2022, 14, e27876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, D.; Koomsap, P.; Lamichhane, A.; Sadiq, M.B.; Anal, A.K. Optimization of collagen extraction from chicken feet by papain hydrolysis and synthesis of chicken feet collagen based biopolymeric fibres. Food Biosci. 2018, 23, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hajj, W.; Salla, M.; Krayem, M.; Khaled, S.; Hassan, H.F.; El Khatib, S. Hydrolyzed collagen: Exploring its applications in the food and beverage industries and assessing its impact on human health – A comprehensive review. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e36433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Chang, B.; Huang, G.; Wang, D.; Gao, Y.; Fan, Z.; Sun, H.; Sui, X. Differential Enzymatic Hydrolysis: A Study on its impact on soy protein structure, function, and soy milk powder properties. Foods. 2025, 14, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synytsya, A.; Janstová, D.; Smidová, M.; Synytsya, A.; Petrtyl, J. Evaluation of IR and Raman spectroscopic markers of human collagens: insides for indicating colorectal carcinogenesis. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2023, 296, 122664. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, M.; Bora, T.; Ghaithi, A.A.; Thukral, S.; Dutta, J. Raman Spectroscopy detects changes in bone mineral quality and collagen cross-linkage in Staphylococcus infected human bone. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 9417. [Google Scholar]

- Bak, S.Y.; Lee, S.W.; Choi, C.H.; Kim, H.W. Assessment of the influence of acetic acid residue on type I collagen during isolation and characterization. Materials. 2018, 11, 2518. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Dong, C.; Li, X.; Han, W.; Su, X. Anticancer potential of bioactive peptides from animal sources (Review). Oncol Rep. 2017, 38, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.G.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, H.J. Induction of apoptosis in a human lymphoma cell line by hydrophobic peptide fraction separated from anchovy sauce. Biofactor. 2004, 21, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.Y.; Lin, W.J.; Lin, TL. A fish antimicrobial peptide, tilapia hepcidin TH2-3, shows potent antitumor activity against human fibrosarcoma cells. Peptides. 2009, 30, 1636–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Yang, P.; Zhou, C.; Li, S.; Hong, P. Marine collagen peptides from the skin of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): Characterization and wound healing evaluation. Mar Drugs. 2017, 15, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidi, F.; Saeid, A. Bioactivity of marine-derived peptides and proteins: A review. Mar Drugs. 2025, 23, 157. [Google Scholar]

- Laemmili, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar]

- Mossman, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).