Introduction

In Mexico, the official statistics of the Secretary of Health reveals that the main causes of death in children under one year of age are asphyxia and trauma at birth (30.4%), lower airway acute respiratory infections (8.6%), newborn bacterial sepsis (8.5%), congenital heart malformations (7.2%), intestinal infectious diseases (4.1%), suffocation (3.7%), low birth weight and prematurity (3.6%), among others. In the same way, the report indicates that the main cause of death in children between one and four years of age is lower airway acute respiratory infections (9.7%) [

1]. In the management of premature apnea, the Diagnosis and Treatment of Premature Apnea Clinical Practice Guide (CPG) recommends a scheme of aminophylline or theophylline administration [

2]. Theophylline is a common drug employed in the treatment of wheezing, shortness of breath and asthma induced chest tightness, chronic bronchitis, emphysema and other lung diseases [

3]. It has effects on the Central nervous system by stimulating the respiratory center [

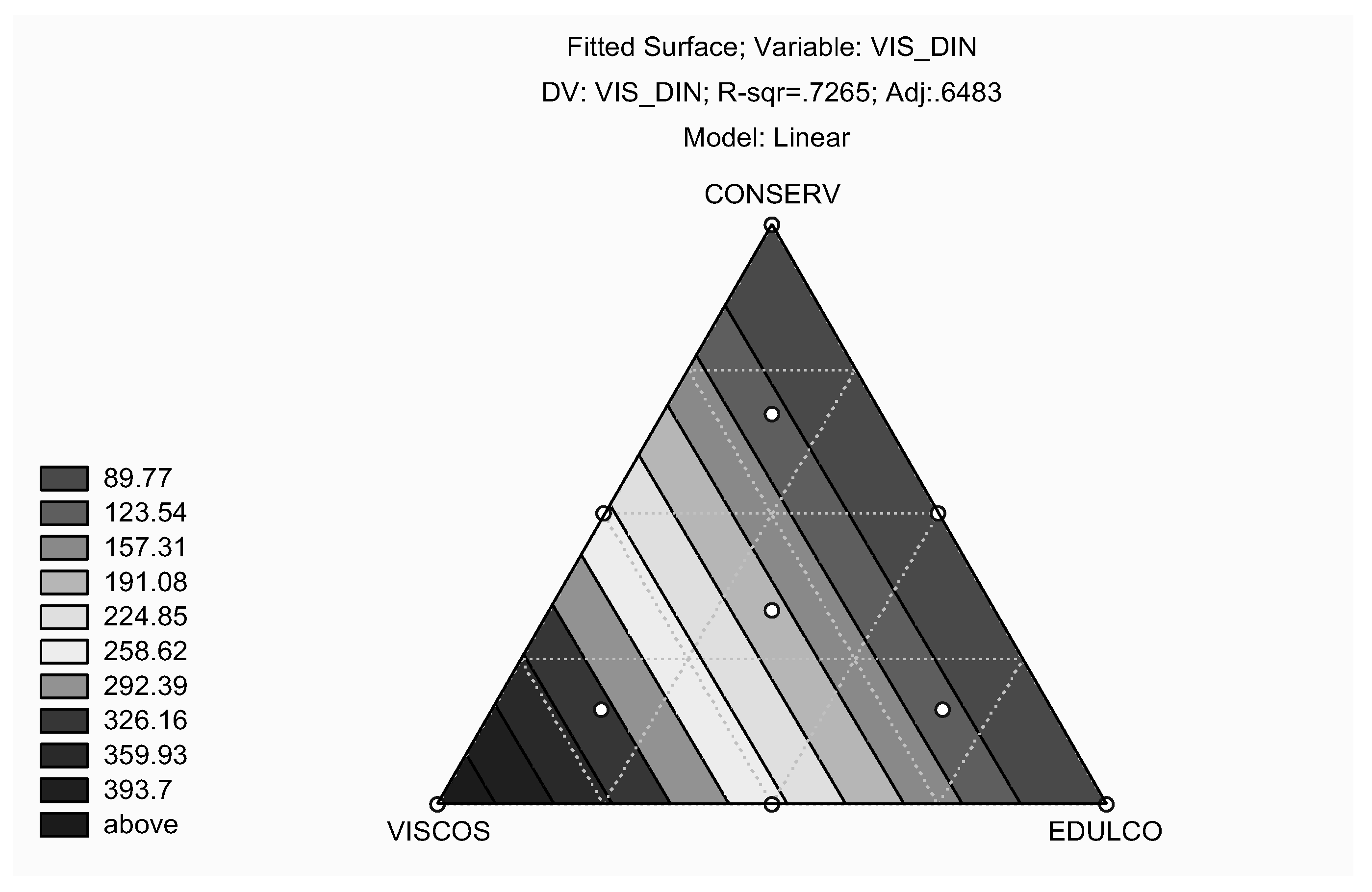

4]. Currently, the limitation in the use of theophylline in children is the lack of good pharmaceutical formulation. This has led to the development of oral theophylline solution (drops), in a concentration of 1mg/ml with adequate excipients that permit the correct dosage for pediatric patients (

Table 1). The new oral theophylline solution not only met the parameters of exact dose, rheology, compatibility, viscosity, pH, taste and stability; but also fulfills the specifications of the pharmacokinetic parameters.

Induced respiratory failure is also characterized by activating oxidative stress-responsive NF-κB pathway [

5]. One of the events in this pathway is cell susceptibility to oxidative damage due to excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) implicated in pathologic process [

6]. Free radicals (FR) are reactive species that possess unpaired electron. They are principally the products of nitrogen and oxygen metabolism, and are generated from normal metabolic reactions, as well as rom exogenous factors [

7]. These radicals are heavily involved in the damage of cell components, particularly the plasma membrane lipids [

8]. The central nervous system (CNS) mediates food consumption control and production of FR. In addition, it actively takes part in food metabolic functions [

9]. Studies have shown that membrane mechanical changes determine many biological processes. These mechanical changes involve the participation of different kinds of lipid components [

10]. In the brain, plasma membrane phospholipids are in direct contact with lipid bilayer structural proteins [

11]. The ionic interchanges occurring in this bilayer are as a result of the action of Na

+, K

+ ATPase [

12]. This enzyme stimulates Na

+ and K

+ flows through the bilayers.

Nitric oxide is a neuromodulator. At high concentrations, it induces cell damage via oxidative stress or by the formation of nitroso-glutathione (NOGSH). Moreover, mitochondrial ultrastructural alterations as well as DNA damage have been reported due to the action of nitric oxide- (NO-) dependent oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders [

13]. We studied the protective effect of a novel theophylline formulation on selected biomarkers of oxidative stress in brain and lung inflammation in a mouse model.

Material and Methods

Chemicals

Theophylline, cafeine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA) an d Sodium hydroxide, sodium phosphate monobasic and dibasic hydrate, trichloroacetic acid, perchloric acid, tris-HCl, potassium cyanide, potassium ferricyanide, formic acid, carbon tetrachloride was purchase from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) and methanol, acetonitrile (analytical grade) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). Water was purified in-house with Milli-Q® Millipore system (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

Biological Evaluation

A basic in vivo experimental study was performed using 100 Balb / c mice comprised of 50 male and 50 female animals. The animals were divided in five groups of 20 mice each consisting of 10 males and 10 females. The animal groups were treated as follows: group I, healthy mice with administration of intranasal isotonic saline solution (control); group II, sick animals without theophylline treatment; group III, sick mice in treatment with oral theophylline solution (2mg / ml); group IV, sick animals in treatment with intravenous theophylline solution (20mg / ml) and group V, healthy animals with administration of intraperitoneal isotonic saline solution (control). After one week of adaptation in laboratory conditions, the animals of groups II, III and IV were sensitized with two doses of 100 µg of ovalbumin (OVA), intraperitoneally administered on days 0 and 14 without the presence of adjuvants. Thereafter, nine intranasal doses of 500 µg OVA were given to each of the mice in these groups on days 14, 27, 28, 29, 47, 61, 73, 74 and 75.

Mouse was decapitated after the latest administration of the treatment and their cerebrum were immediately dissected and submerged in a solution of NaCl at 0.9% and maintained at 4°C. Besides, blood samples were obtained and used to assess the levels of hemoglobin and triglycerides. Each brain and lunge were homogenized with Teflon pestle (Bodine Electric, Danbury, CT) in 3ml of tris-HCl 0. 05M pH 7.2 and used to assay the peroxidation of lipids (TBARS), H

2O

2 and the glutathione (GSH) levels determination using previously validated methods. The samples were kept at –20°C until their analysis. Animals were maintained in a mass air displacement room with a 12-h light:12-h dark at 22 ± 2°C with a relative humidity of 50 ± 10%. Feeding was based on balanced food (Rodent diet 5001, Minnetonka, MN) and water ad libitum. Experiments were carried out under strict compliance with the Guidelines for Ethical Control and Supervision in the Care and Use of Animals. The measurement of hemoglobin was carried out at the end of treatment. Two blood samples of 20µl each were drawn from the tail-end without anticoagulant and placed on solution to measure in spectrophotometer UV-VIS (Beckman, model DU-650, Philadelphia, USA) the concentrations of hemoglobin reported in mg/dl [

14]. The levels of GSH were measured with spectrofluorometer (Perkin Elmer LS 55, Beaconsfield, England) from the supernatant of the homogenized tissue, which was obtained after centrifuging at 9000 rpm during 5 min (Hettich Zentrifugen, model Mikro 12-42, Tuttingen, Germany) based on a modified method of Hissin and Hilf [

15].

Lipid peroxidation

Thiobarbaturic acid reactive substance (TBARS) determination was carried out using the modified technique of Gutteridge and Halliwell [

8], as described below: From the homogenized brain in tris-HCl 0.05M pH 7.4, 1ml was taken and to it was added 2ml of thiobarbaturic acid (TBA) containing 1.25g of TBA, 40g of trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and 6.25ml of concentrated chlorhydric acid (HCL) diluted in 250ml of deionized H

2O. They were heated to boiling point for 30min. (Thermomix 1420, Craft, Mexico City, Mexico). The samples were later put in ice bath for 5min. and were centrifuged at 700g for 15min. (Sorvall RC-5B Dupont, Newton CT). The absorbances of the floating tissues were read in triplicate at 532nm in a spectrophotometer (Helios de UNICAM, Cambridge, England). The concentration of reactive substances to the thiobarbaturic acid (TBARS) was expressed in µM of Malondialdehyde/g of wet tissue.

The determination of H

2O

2 was made using the modified technique [

16]. Each brain region (cortex, hemispheres, cerebellum/medulla oblongata) was homogenized in 3 ml of tris-HCl 0.05M pH 7.4 buffer. From the diluted homogenates, 100µl was taken and added to 1ml of potassium dichromate solution 5% (K

2Cr

2O

7) and perchloric acid. The mixture was heat to boiling point for 15min. (Thermomix 1420, Craft, Mexico City, Mexico). The samples were later placed in an ice bath for 5 min and then centrifuged at 3,000g for 5min. (Sorvall RC-5B Dupont, Newton CT). The absorbances of the floating were read in triplicate at 570nm in a spectrophotometer (Heλios-α, UNICAM, Cambridge England). The concentration of H

2O

2 was expressed in µMoles.

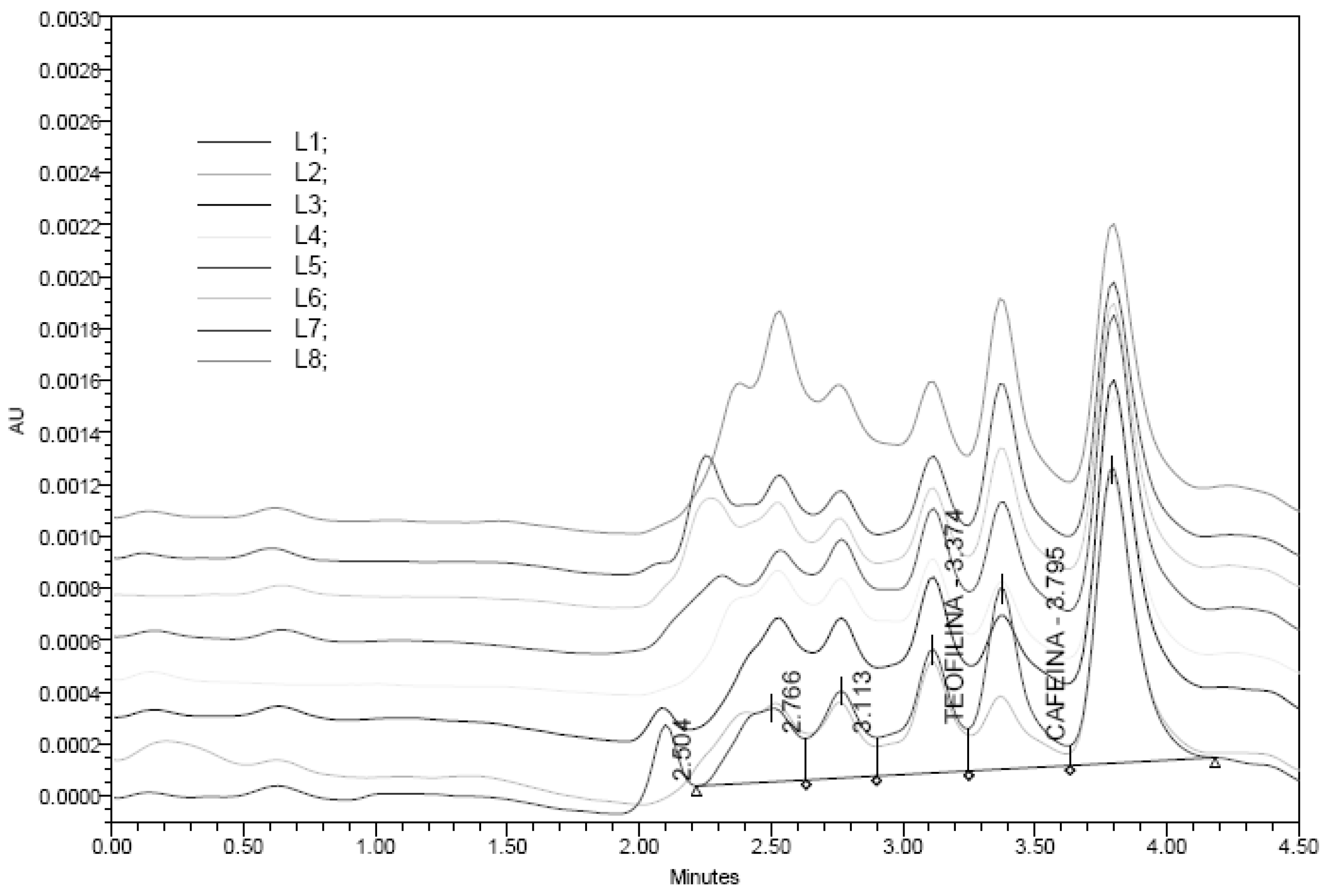

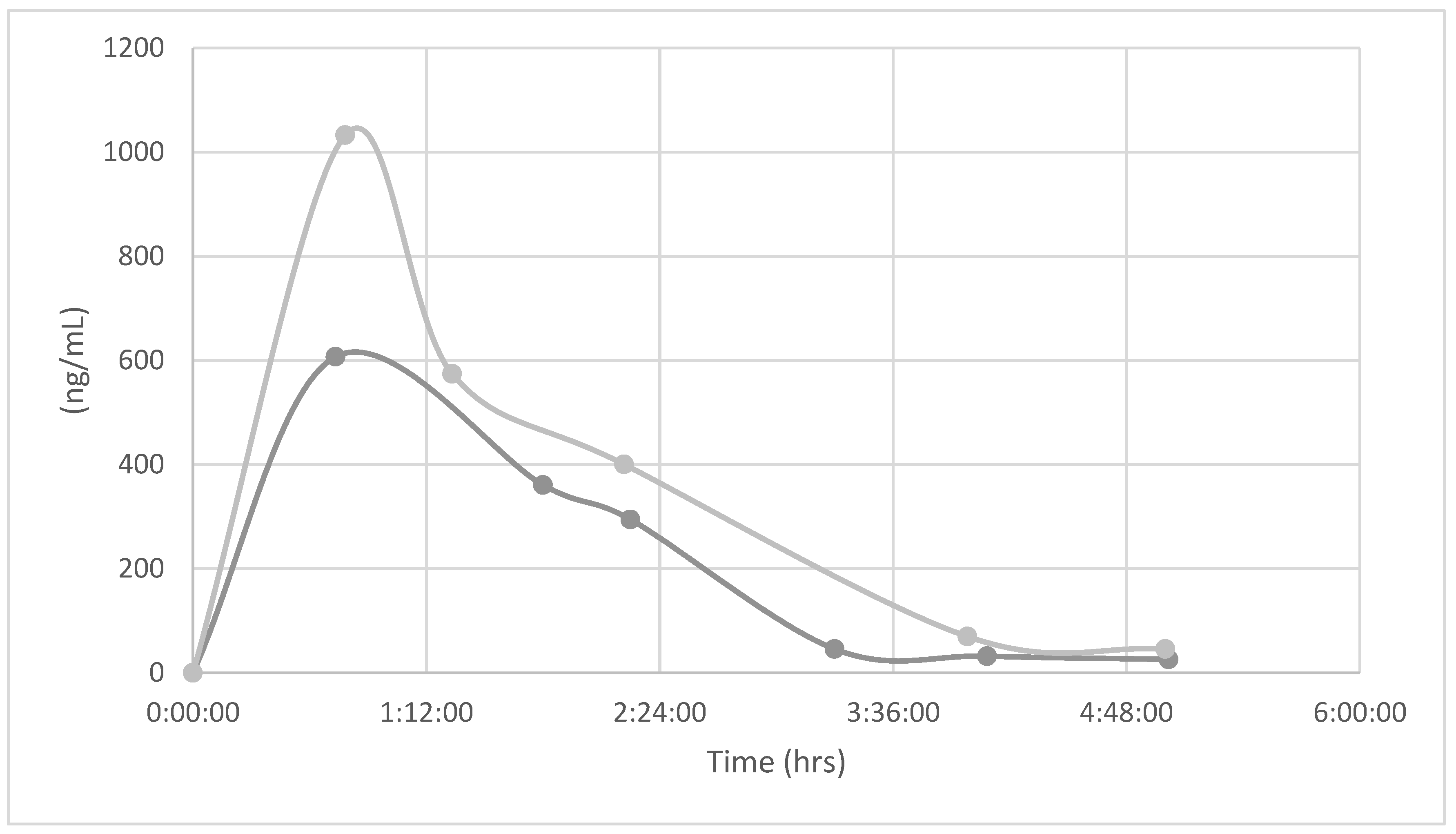

Theophylline in plasma

At the end of the study the animals were sacrificed and collected the blood to measure theophylline levels on plasma using an analytical method based on UPLC-Mass spectrometry system, (Waters, Massachussets USA) for quantification of theophylline in mouse plasma after oral administration [

17]. The analyte was extracted from plasma by protein precipitation with methanol using cafeine as internal standard (I.S). Chromatografic conditions: Detector UV, λ 273nm, C18-4D column using a gradient elution of acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid in water at a flow rate of 0.1 mL/min. Theophylline and I.S, 10µl in carbon tetrachloride. were detected and quantified using positive electrospray ionization. Total run time was finished in 4.5 min. The data suggested that the precision and accuracy of the method were sufficient for the quantification of theophylline in plasma of animals with oral theophylline treatment and previously sensitized with ovalbumin.

Statistical analysis of biological assay

Descriptive statistics include tables and graphs with measures of central tendency and dispersion. The strategy employed for inference analysis was a comparison of the levels of Hemoglobin (Hb), Glutathione (GSH), lipid peroxidation (Tbars) and Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) between the experimental groups using hypothesis-contrasting tests: Analysis of variance (ANOVA) or "t" for Student.

All tests were conducted with respect to the premises for the use of parametric statistical tests. Non-parametric tests i.e. Kruskall Wallis test or Wilcoxon test were used to verify the non-existence of homogeneous variances by Bartlett’s X2 test. The appropriate post-hoc test, i.e. Tukey or Dunnett test, was performed in cases where data allowed this [

18]. The JMP version 10.0 for academic was used.

Results

Levels of glutathione (GSH)

In the female animals, the concentration of GSH showed a significant increase. ANOVA (p <0.001) in the brain of the experimental groups (No / ovalbumin No / theophylline) when compared with the control groups. Comparison between the experimental groups (II – IV) does not show significant differences; however, it is worthy to note that the group II treated with only ovalbumin depicted similar behavior as the groups that received both oral and intravenous theophylline.

In the case of male animals in the group treated with only ovalbumin showed a significant increase in GSH with respect to the groups that received intravenous ovalbumin + theophylline. ANOVA (p<0.02), and the group that received oral theophylline and OVA. ANOVA (p< 0.01). The results showed a differential response to treatment with ovalbumin or theophylline in male animals in these groups.

Table 3.

Lipid peroxidation (TBARS)

In female’s animals, TBARS concentration showed significant differences. Wilcoxon (p=0.003) when the experimental groups (ovalbumin + oral theophylline and ovalbumin + intravenous theophylline) were compared with the control groups (No / ovalbumin No / theophylline).

Among the experimental groups, the statistical analysis revealed significant differences. Wilcoxon (p=0.0009) in TBARS concentration between the groups treated with only oral theophylline and those that were administered ovalbumin + oral theophylline. The same behavior was observed when this group of animals were compared with those to which only ovalbumin was administered. In male animals, no differences were observed in the levels of TBARS.

Table 3.

Levels of Hemoglobin (Hb)

The effect of the administration of albumin and theophylline on the hemoglobin concentration was only seen in the female animals in the groups that received these treatments. The administration of ovalbumin + theophylline increased Hb concentration in all groups, and this was statistically significant. Wilcoxon (p <0.03) only when the control groups (No / ovalbumin No / theophylline) was compared with the experimental groups (yes / ovalbumin + oral theophylline and yes / ovalbumin + theophylline iv). On comparing the experimental groups, a significant difference. Wilcoxon (p <0.05) was observed between the group yes / ovalbumin without theophylline vs the group yes / ovalbumin + oral theophylline. In the male animals in the groups, no difference was observed. (

Table 3)

The analysis of the data showed that the behavior of all the biochemical indicators evaluated was different for male and female animals.

GSH in the lung

The effect of the administration of the treatments on the concentration of GSH in the lung was only observed with a significant increase. ANOVA (p =0.02) in the male animals in the group treated with ovalbumin + oral theophylline. However, this observation holds the truth when this group is compared with the rest of the groups including the control groups. No statistically significant differences were observed among the female animals in the groups, even though the group treated with ovalbumin + oral theophylline also showed an increase in GSH levels.

Table 4.

Levels of H2O2

The statistical analysis of the data showed that for both the female and male animals, the administration of ovalbumin or theophylline did not show effects on the biochemical indicators evaluated. Although, an increase in H

2O

2 was observed in the male animals in the group that received only ovalbumin; however, this increase was not statisticaly significant. (

Table 5)

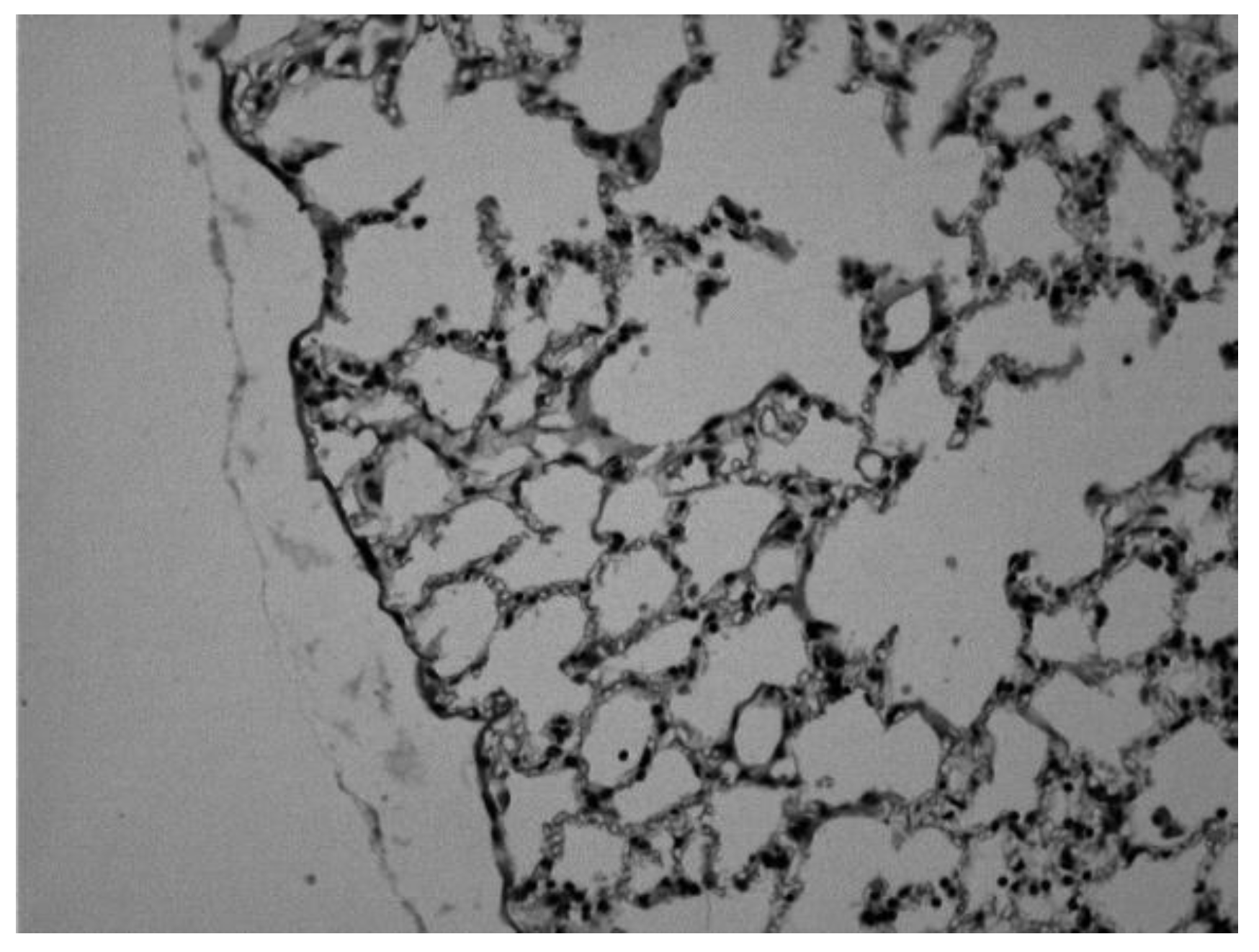

Histological analysis

Histological examination of the tissue was conducted after immediately following brain extraction. The tissues were gently rinsed with a physiological saline solution (0.9% NaCl) to remove blood and adhering debris. Lungs were taken and fixed in a 10% neutral-buffered formalin solution for 24 h. The fixed specimens were then trimmed, washed and dehydrated in ascending grades of alcohol. These specimens were cleared in xylene, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4–6 mm thickness and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and then examined microscopically in Microscope (Olympus BX-51, Shinjuku Tokyo, Japan) [

21].

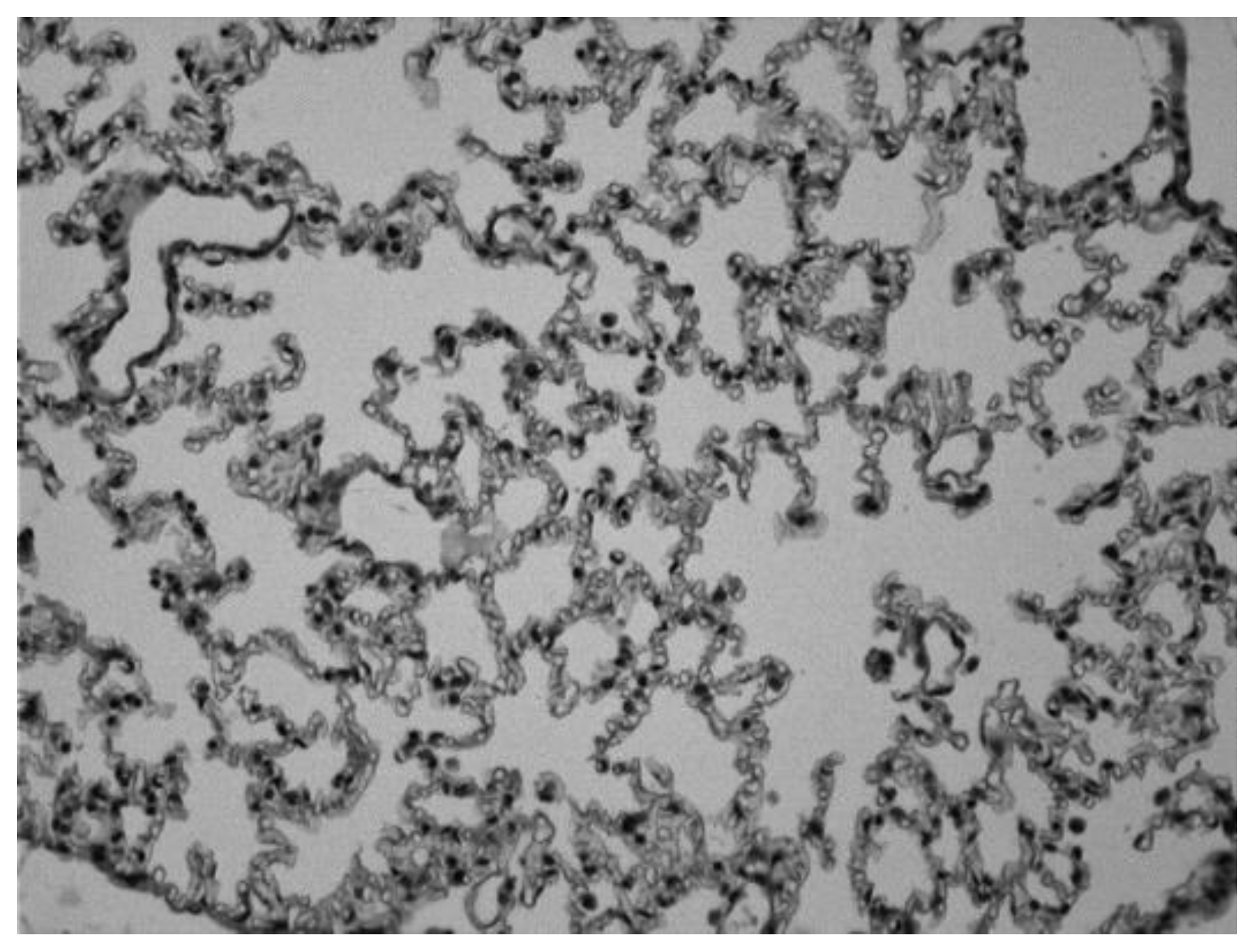

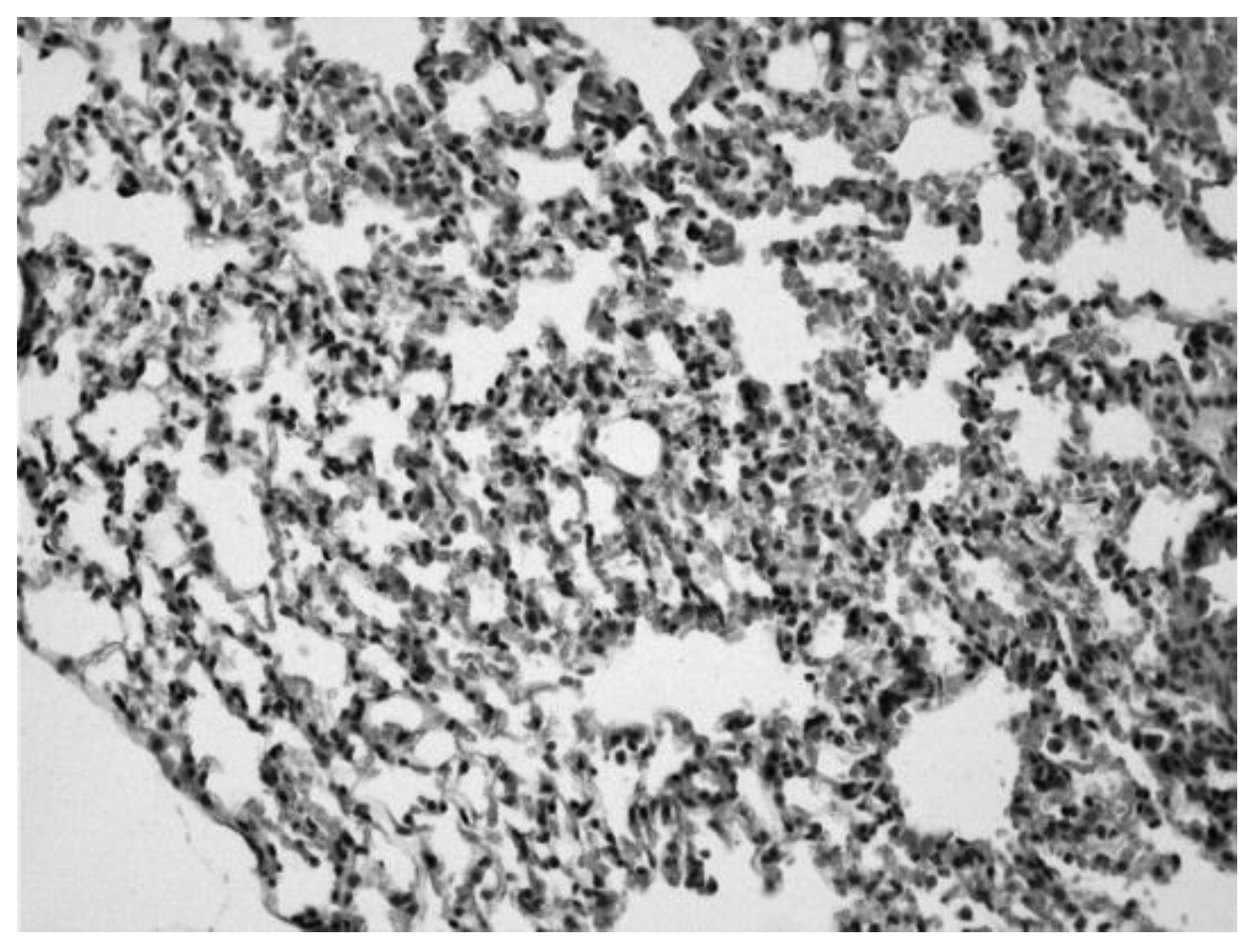

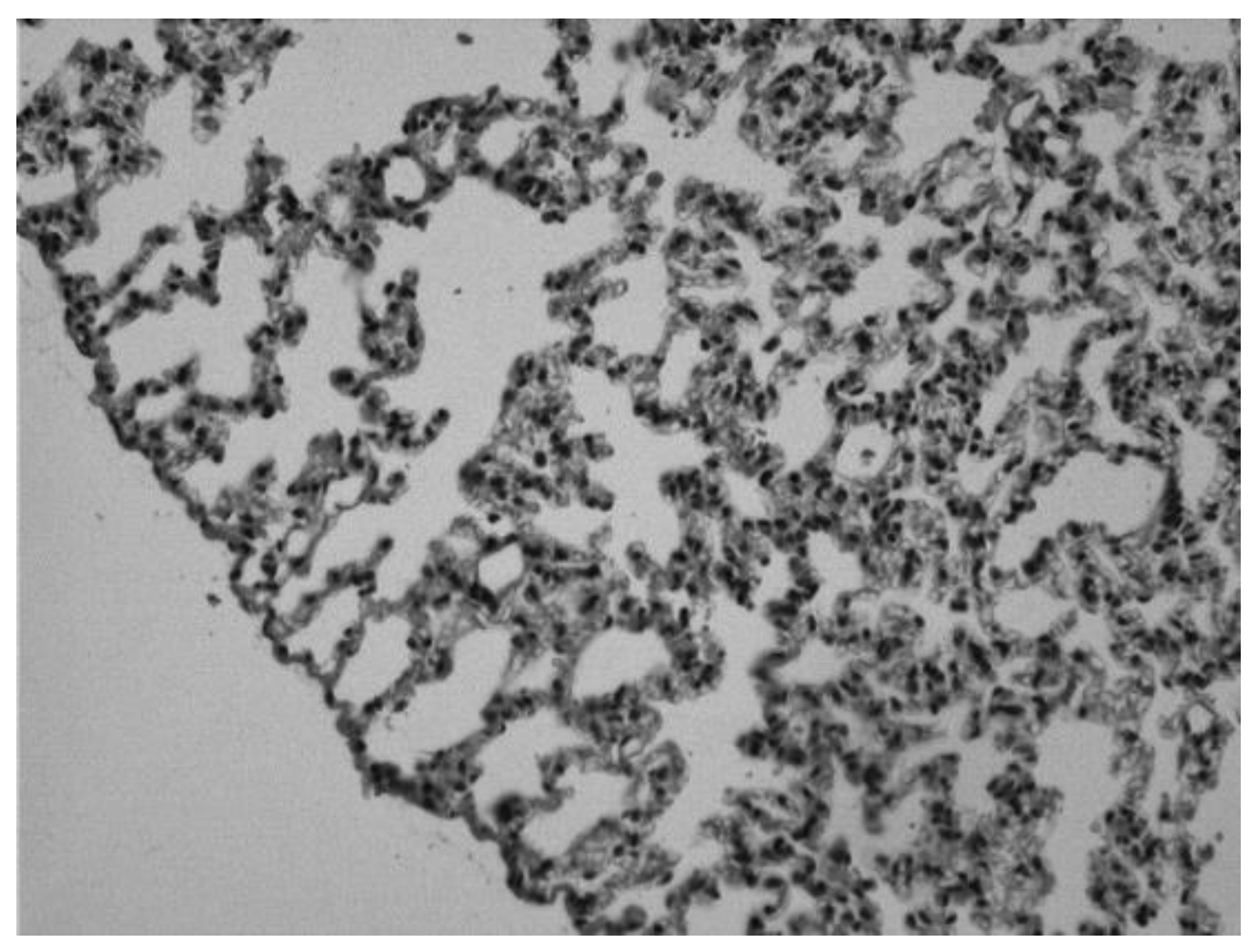

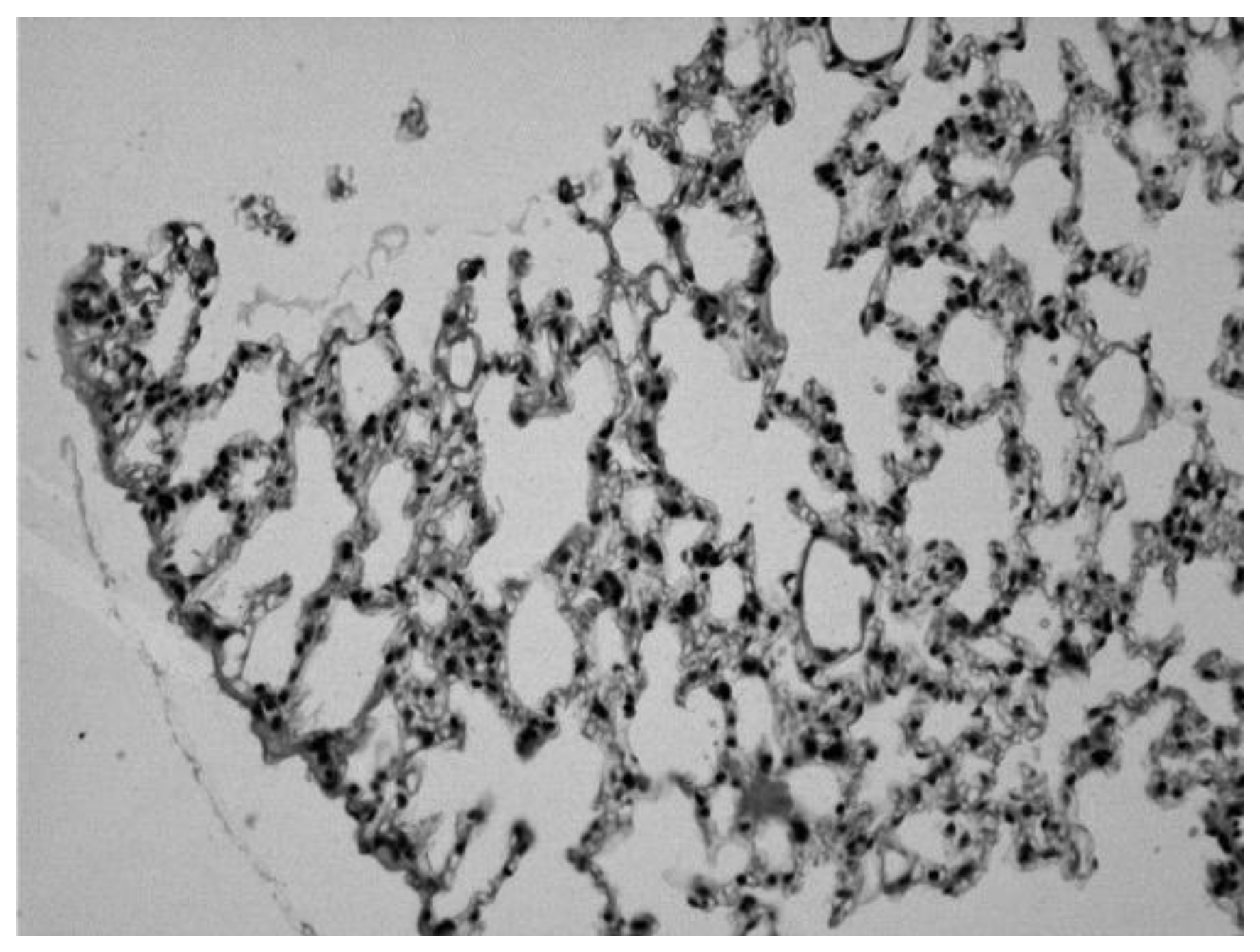

Histological changes observed in the lung of mouse sensitized with ovalbumin and treated with theophylline in oral and intravenous solution.

Image 1.

Lung of a control animal in which we can observe normal alveolar spaces (Hematoxylin-eosin 20x).

Image 1.

Lung of a control animal in which we can observe normal alveolar spaces (Hematoxylin-eosin 20x).

Image 2.

Lung of an animal sensitized with ovalbumin in which we can observe infiltrates of inflammatory cells and erythrocytes in the alveolar spaces (Hematoxylin-eosin 20x).

Image 2.

Lung of an animal sensitized with ovalbumin in which we can observe infiltrates of inflammatory cells and erythrocytes in the alveolar spaces (Hematoxylin-eosin 20x).

Image 3.

Lung of an animal sensitized with ovalbumin and treated with theophylline intraperitoneally. We can observe infiltrates of inflammatory cells and erythrocytes, but to a lesser degree than in the untreated diseased group (Hematoxylin-eosin 20x).

Image 3.

Lung of an animal sensitized with ovalbumin and treated with theophylline intraperitoneally. We can observe infiltrates of inflammatory cells and erythrocytes, but to a lesser degree than in the untreated diseased group (Hematoxylin-eosin 20x).

Image 4.

Lung of an animal sensitized with ovalbumin and treated with orally administered theophylline, in which we can observe normal alveolar spaces (Hematoxylin-eosin 20x).

Image 4.

Lung of an animal sensitized with ovalbumin and treated with orally administered theophylline, in which we can observe normal alveolar spaces (Hematoxylin-eosin 20x).

Image 5.

Lung of a control animal treated with saline solution, in which we can observe normal alveolar spaces (Hematoxylin-eosin 20x).

Image 5.

Lung of a control animal treated with saline solution, in which we can observe normal alveolar spaces (Hematoxylin-eosin 20x).

Discussion

The data suggested that the precision and accuracy of the method were sufficient for the quantification of theophylline in plasma of animals with oral theophylline treatment and previously sensitized with ovalbumin. Likewise, the specifications of the pharmacokinetic parameters validated suggest that novel theophylline formulation can meets requirements for clinical patients.

On the other hand, in asthma, airway remodeling is affected when there is an imbalance between oxidative stress and antioxidant defense system. Redox regulation is part of various cellular processes and a good example of this is in the immune response [

22]. In fact, protection against inflammatory damage is provided by specific redox proteins and particular enzyme activities. Nevertheless, it is reported that inflammation induced by asthma is not only restricted to the lung, but also may affect many remote organs and cause damages in them [

23]. This point is buttressed by the fact that in asthma, leukocytes invade the CNS and together with CNS-resident cells, generate excessive reactive oxygen species [

24].

In the present study, the concentration of GSH in the brain showed a significant increase in all the experimental groups with respect to the control group. In addition, an increase GSH concentration was observed in the lung of the male animals treated with oral ovalbumin + theophylline. These results coincide with the reports in the study of Wang et al [

25]. These authors found that oxidative stress plays an important role in the pathogenesis of asthma. Glutathione (GSH) is considered to be one of the most important antioxidants for its protective effect against oxidation of sulfhydryl groups. The administration of albumin + theophylline increased the concentration of Hb in all the female animals in the groups. This suggests airway hyper-responsiveness [

26].

On the other hand, lipoperoxidation levels decreased in females that received ovalbumin alone or in combination with theophylline. These results are contrary to what were reported by Liu et al [

27]. These authors reported an increase in malondialdehyde levels in asthmatic subjects with a high-fat diet. Probably, this may be due to the fact that obesity generates an increase in free radicals. Furthermore, the authors suggest that there was a positive correlation between MDA and NF-κB activation in the lung tissues in the asthma groups.

Conclusion

Based on the results of the present study, novel theophylline formulation not only met the parameters of exact dose, rheology, compatibility, viscosity, pH, taste and stability; but also fulfills the specifications of the pharmacokinetic parameters. Histological changes revealed lesions of lung cells in experimental animals treated with ovalbumin.

In fact, it is suggested that in OVA-induced allergic airway inflammation, theophylline novel formulation alleviates airway asthma induced inflammation, which likely occurs via the oxidative stress-responsive lipid peroxidation pathway; thus, highlighting its potential as a useful therapeutic agent for asthma management in children.

Author Contributions

EHGa,b,c,d, DCGb,c,d, NOBb,c,d, MOHc,d, AVPb,c,d, DSAb,c,d, JLCPb,c,d, ACHb,c,d, HJOb,c,d (a) Contributed to conception. (b) Critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. (c) Drafted manuscript. (d) Gave final approval. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics for Animal Committee of National Institute of Pediatrics. Project: 026/2022 on Sept 5, 2022.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Cyril Ndidi Nwoye, an expert translator and a native English speaker for reviewing and correcting the manuscript We thanks Monica Janette Cervantes Arellano, Lab Chemist. Irene Deyanira Herrerias Macias, Lab Technician. For assistence in the study. The authors express their profound gratitude to the National Institute of Pediatrics (INP) for the support in the publication of this article, derived from the project 044/2017

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that there have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tinoco Favila, M.; Guerrero Romero, F.; Rodriguez Moran, M. Early neonatal mortality in a secondary care center in newborns older than 28 weeks of gestational age and with a birth weight equal to or greater than 1000 g. [Mortalidad neonatal temprana en un centro de segundo nivel de atención en recién nacidos mayores de 28 semanas de edad gestacional y peso al nacer igual o mayor de 1000 g]. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex 2004, 61, 282–288. [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Apnea of Prematurity. [Diagnóstico y Tratamiento de Apnea del Prematuro]. México: Secretaría de Salud; 25 de septiembre de 2014. http://www.cenetec.salud.gob.mex/interior/catalogMaestroGPC.html.

- Vademecum.es. (revisado 06/02/2017) http://www.vademecum.es/principios-activos-teofilina-r03da04.

- Rodríguez, J.P. Apnea in the neonatal period. [Apnea en el periodo neonatal] Servicio Neonatología, Hospital Universitario la Paz, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, 2008, 32.

- Yong Pil Hwang; Sun Woo Jin; Jae Ho Choi; Chul Yung Choi; Hyung Gyun Kim; Se Jong Kim; Yongan Kim; Kyung Jin Lee; Young Chul Chung; Hye Gwang Jeong. Inhibitory effects of l-theanine on airway inflammation in ovalbumin-induced allergic asthma. Food Chem Toxicol 2007, 99, 162-169.

- Coyle, J.T.; Puttfarcken, P. Oxidative stress, glutamate and neurodegenerative disorders. Science 1993, 262, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.K.; Brzezinska-SIebodzinska, E.; Madsen, F.C. Oxidative stress, antioxidants, and animal function. J Dairy Sci 1993, 76, 2812–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutteridge, J.M.; Halliwell, B. The measurement and mechanism of lipid peroxidation in biological systems. Trends Biochem Sci 1990, 15, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driver, A.S.; Kodavanti, P.R.; Mundy, W.R. Age-related changes in reactive o.ygen species production in rat brain homogenates. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2000, 22, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamitko-Klingensmith, N.; Molchanoff, K.M.; Burke, K.A.; Magnone, G.J.; Legleiter, J. Mapping the mechanical properties of cholesterol-containing supported lipid bilayers with nanoscale spatial resolution. Langmuir 2012, 28, 13411–13422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swapna, I.; Sathya, K.V.; Murthy, C.R.; Senthilkumaran, B. Membrane alterations and fluidity changes in cerebral cortex during ammonia intoxication. Neurotoxicology 2005, 335, 70–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanello, F.M.; Chiarani, F.; Kurek, A.G. Methionine alters Na+, K+ ATPase activity, lipid peroxidation and nonenzymatic antioxidant defenses in rat hippocampus. Int J Develop Neurosci 2005, 23, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliev, G.; Obrenovich, M.E.; Tabrez, S.; Jabir, N.R.; Reddy, V.P.; Li, Y.; Burnstock, G.; Cacabelos, R.; Kamal, M.A. Link between cancer and Alzheimer disease via oxidative stress induced by nitric oxide-dependent mitochondrial DNA overproliferation and deletion. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013, 962984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rem, J.; Siggaard-Andersen, O.; Norgaard-Pedersen, B.; Sorensen, S. Hemoglobin pigments. Photometer for oxygen saturation, carboxyhemoglobin, and methemoglobin in capillary blood. Clin Chim Acta 1972, 42, 101–08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hissin, P.J.; Hilf, R. 1974. A fluorometric method for determination of oxidized and reduced glutathione in tissue. Anal Biochem 1974, 4, 214–226. [Google Scholar]

- Asru, K.S. Colorimetric assay of catalase. Anal Biochem 1972, 47, 389–394. [Google Scholar]

- Yi Zhang; Nitin Mehrotra; Nageshwar R Budha.; Michael L Christensen; Bernd Meibohm. A tandem mass spectrometry assay for the simultaneous determination of acetaminophen, caffeine, phenytoin, ranitidine, and theophylline in small volume pediatric plasma specimens. Clin Chim Acta 2008, 398(1-2), 105-12.

- Castilla-Serna, L. Manual Práctico de Estadística para las Ciencias de la Salud. Editorial Trillas. 2011, 1° Edición. México, D.F.

- Pharmacopoeia of the United Mexican States. [Farmacopea de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos] 10ª edición, México: Secretaría de Salud, Comisión Permanente de la Farmacopea de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 2013.

- Alok K Kulshreshtha; Singh O.G.; Michael Wall G. Pharmaceutical Suspensions: From Formulation Development to Manufacturing. Springer, USA, 2010.

- Luna, L.T. Manual of Histologic Staining Methods of the Armed Force Institute of Pathology. McGraw Hill Book Co., 1968, New York. pp: 1-39.

- Hanschmann, E.M.; Berndt, C.; Hecker, C.; Gran, H.; Bertrams, W.; Lillig, C.H.; Hudemann, C. Glutaredoxin 2 Reduces Asthma-Like Acute Airway Inflammation in Mice. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 561724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzaneh Kianian; Behjat Seifi; Mehri Kadkhodaee; Hamid Reza Sadeghipour; Mina Ranjbaran. Nephroprotection through Modifying the Apoptotic TNF-α/ERK1/2/Bax Signaling Pathway and Oxidative Stress by Long-term Sodium Hydrosulfide Administration in Ovalbumin-induced Chronic Asthma. Immunol Invest 2020, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Géssica Luana Antunes; Josiane Silva Silveira; Daniela Benvenutti Kaiber; Carolina Luft; Tiago Marcon Dos Santos; Eduardo Peil Marques; Fernanda Silva Ferreira; Felipe Schmitz; Angela Terezinha de Souza Wyse; Renato Tetelbom Stein; Paulo Márcio Pitrez; Aline Andrea da Cunha. Neostigmine treatment induces neuroprotection against oxidative stress in cerebral cortex of asthmatic mice. Metab Brain Dis 2020, 35(5), 765-774. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, A.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, P. Glutathione ethyl ester supplementation prevents airway hyper-responsiveness in mice. Ann Transl Med 2020, 8, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sano, K.; Haneda, K.; Tamura, G.; Shirato, K. Ovalbumin (OVA) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli cooperatively polarize anti-OVA T-helper (Th) cells toward a Th1-dominant phenotype and ameliorate murine tracheal eosinophilia. Am J Resp Cell Mol Biol 1999, 20(6), 1260–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiaomei Liu; Mingji Yi; Rong Jin; Xueying Feng; Liang Ma; Yanxia Wang; Yanchun Shan; Zhaochuan Yang; Baochun Zhao. Correlation between oxidative stress and NF-κB signaling pathway in the obesity-asthma mice. Mol Biol Rep 2020, 47(5), 3735-3744. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).