Submitted:

03 September 2025

Posted:

04 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Callus Culture

2.2. Addition of Regulators to the Proliferation Medium

2.3. Addition of Regulators to the Somatic Embryo Induction Medium

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Regulators on Callus Proliferation and Morphology

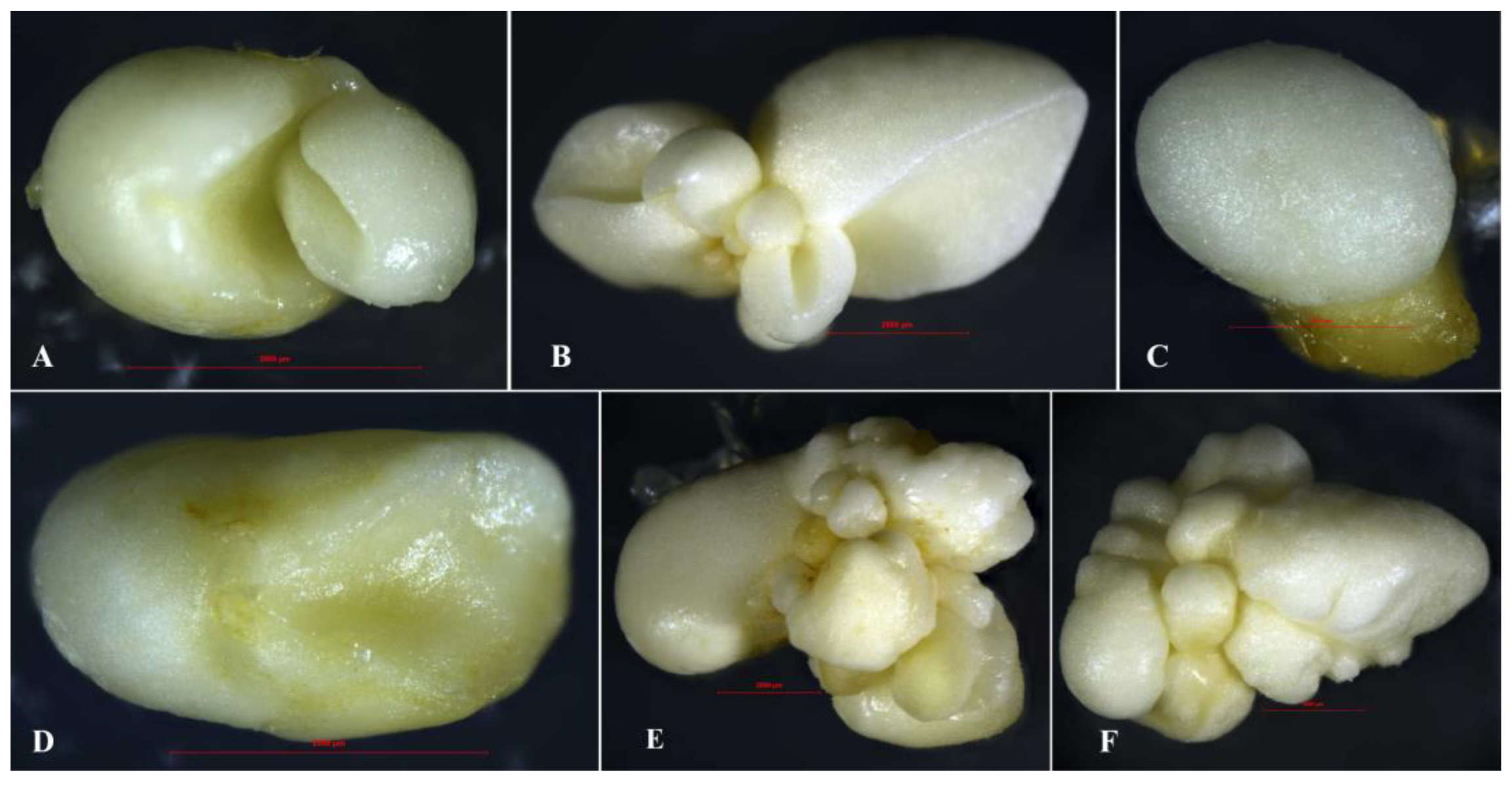

3.2. Somatic Embryogenesis and Regeneration

3.3. Effects of PAA/CPA/IPA Combined with KT or TDZ on Somatic Embryogenesis and Regeneration

3.3.1. PAA Combined with KT or TDZ

3.3.2. CPA Combined with KT or TDZ

3.3.3. IPA Combined with KT or TDZ

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hussain, S.Z.; Naseer, B.; Qadri, T.; Fatima, T.; Bhat, T.A. Litchi (Litchi chinensis): Morphology, taxonomy, composition and health beneffts. In Fruits grown in Highland regions of the himalayas: Nutritional and Health beneffts; Hussain, S.Z., Naseer, B., Qadri, T., Fatima, T., Bhat, T.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Litz, R.E. Somatic embryogenesis from cultured leaf explants of the tropical tree Euphoria longan Stend. J Plant Physiol. 1988, 132, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litz, R.E.; Raharjo, S. Dimocarpus longan longan and Litchi chinensis litchi. In Biotechnology of Fruit And Nut Crops; Litz, R.E., Ed.; CABI: Wallingford, 2005; pp. 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, K.R. Lychae. In Tropical Tree Fruits for Australia; Page, P.E., Ed.; Queensland Department of Primary Industries: Brisbane, 1984; pp. 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.Q.; Wang, D.; Fu, J.X.; Zhang, Z.K.; Qin, Y.H.; Hu, G.B.; Zhao, J.T. Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated hairy root transformation as an efficient system for gene function analysis in Litchi chinensis. Plant Methods. 2021, 17, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.Q.; Zhang, B.; Wang, S.Q.; Guo, W.Y.; Zhang, Z.K.; Qin, Y.H.; Zhao, J.T.; Hu, G.B. Establishment of somatic embryogenesis regeneration system and transcriptome analysis of early somatic embryogenesis in Litchi chinensis. Hort. Plant J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.Q.; Zhang, B.; Luo, X.L.; Wang, S.Q.; Fu, J.X.; Zhang, Z.K.; Qin, Y.H.; Zhao, J.T.; Hu, G.B. Development of an Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediate transformation system for somatic embryos and transcriptome analysis of LcMYB1’s inhibitory effect on somatic embryogenesis in Litchi chinensis. J. Integr. Agric. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Wang, G.; Li, H.L.; Li, F.; Wang, J.B. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of embryogenic callus and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in 'Feizixiao' litchi. Hort. Plant J. 2023, 9, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, H.L.; Wang, S.J.; Sun, J.H.; Zhang, X.C.; Wang, J.B. In vitro regeneration of litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 15, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.K.; Rahman, A.; Kumari, D.; Kumari, N. Synthetic seed preparation, germination and plantlet regeneration of Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Am. J. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1395–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.Q.; Guo, W.Y.; Wu, X.Y.; Qin, Y.Q.; Sabir, I.A.; Zhang, Z.K.; Qin, Y.H.; Hu, G.B.; Zhao, J.T. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration of Litchi chinensis Sonn. cv. 'Zili' from immature zygotic embryos. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 2024, 156, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.H.; Chen, Z.G.; Lu, L.X.; Lin, J.W. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration from litchi protoplasts isolated from embryogenic suspensions. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 2000, 61, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raharjo, S.H.T.; Litz, R.E. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration of litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) from leaves of mature phase trees. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 2007, 89, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.J.; Yi, G.J.; Zeng, J.W.; Zhang, Q.M.; Liu, W.G. Application of orthogonal experiment on induction of somatic embryogenesis in Litchi. Fujian Fruit. 2007, 141, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, H.L.; Wang, S.J.; Li, F.; Wang, J.B. Effects of different plant growth regulators on somatic embryogenesis of Litchi 'Xinqiumili' and the histological observation of the somatic embryos. Chinese J. Trop. Agricul. 2020, 40, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.Y.; Yi, G.J.; Huang, X.L. Leaf callus induction and suspension culture establishment in litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) cv. Huaizhi. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2009, 31, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Feng, J.; Xiang, X. Induction of embryogenic callus and subculture proliferation of Litchi chinensis leaves. Guangdong Agricultural Sciences 2021, 48, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Y.T.; Gao, Z.Y.; Li, H.L.; Wang, J.B. Effects of amino acids on callus proliferation and somatic embryogenesis in Litchi chinensis cv. ‘Feizixiao’. Horticulturae. 2023, 9, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giridhar, P.; Ramu, G.D.V.; Ravishankar, G.A. Phenyl acetic acidinduced in vitro shoot multiplication of Vanilla planifolia. Trop Sci. 2003, 43, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giridhar, P.; Vijayaramu, D.; Obulreddy, B.; Rajasekaran, T.; Ravashankar, G.A. Influence phenylacetic acid on clonal propagation of Decalepis hamiltonii Wight and Arn: An endangered shrub. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol-Plant. 2003, 39, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanti, S.K.; Sujata, K.G.; Rao, M.S. The effect of phenylacetic acid on bud induction, elongation and rooting of chickpea. Biol. Plant. 2009, 53, 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.R.; Li, H.Y.; Liu, M.Y.; Jiang, J.; Yin, Y.F.; Zhang, L.; Zhuo, R.Y. Callus induction and plant regeneration from anthers of Dendrocalamus latiflorus Munro. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol-Plant. 2013, 49, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, S.; Mashiguchi, K.; Tanaka, K.; Hishiyam, H. Distinct characteristics of indole-3-acetic acid and phenylacetic acid, two common auxins in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 1641–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumayo, M.S.; Son, J.S.; Ghim, S.Y. Exogenous application of phenylacetic acid promotes root hair growth and induces the systemic resistance of tobacco against bacterial soft-rot pathogen Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. Carotovorum. Funct. Plant Biol. 2018, 45, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.Y. Data processing system-experimental design, statistical analysis and data mining (second edition). 2010. Available online: www.sciencep.com.

- Das, D.K.; Rahman, A. Expression of a bacterial chitinase (ChinB) gene enhances antifungal potential in transgenic Litchi Chinensis Sonn. (Bedana). Curr. Trends Biotechnol. Pharm. 2010, 4, 820–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.F.; Tang, D.Y. Induction pollen plants of litchi tree (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Acta Genet. Sin. 1983, 10, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimmon, T.; Qureshi, J.A.; Saxena, P.K. Phenylacetic acid induced somatic embryogenesis in cultured hypocotyl explants of Geranium (Pelargonium × hortorum Bailey). Plant Cell Rep. 1991, 10, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.F.; Morris, D.A. Regulation of auxin transport in the pea (Pisum sativum L.) by phenylacetic acid: Effects on the components of transmembrane transport of indol-3yl-acetic acid. Planta 1987, 172, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregitzer, P.; Campbell, R.D.; Wu, Y. Plant regeneration from barley callus: Effects of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and phenylacetic acid. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult 1995, 3, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, S.D. An historical review of phenylacetic acid. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwase, A.; Takebayashi, A.; Aoi, Y.; Favero, D.S.; Watanabe, S.; Seo, M.; Kasahara, H.; Sugimoto, K. 4-Phenylbutyric acid promotes plant regeneration as an auxin by being converted to phenylacetic acid via an IBR3-independent pathway. J. Plant Biotechnol. 2022, 39, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchooa, D. In vitro regeneration of litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn. ). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2004, 3, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanida, K.; Shiota, H. Anise-cultured cells abolish 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in culture medium. Plant Biotechnol. 2019, 36, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayani, M.; Varsha, M.K.N.S.; Potunuru, U.R.; Beaula, W.S.; Rayala, S.K.; Dixit, M.; Chadha, A.; Srivastava, S. Production of bioactive cyclotides in somatic embryos of Viola odorata. Phytochemistry 2018, 156, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuła, A.; Tomaszewicz, W.; Dziurka, M.; Kaźmierczak, A.; Grzyb, M.; Sobczak, M.; Zdańkowski, P.; Rybczyński, J. The origin of the Cyathea delgadii Sternb. somatic embryos is determined by the developmental state of donor tissue and mutual balance of selected metabolites. Cells 2021, 10, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.R.; Fan, F.F.; Xu, Y.W.; Peng, Z.; Yu, C.X.; Liu, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.Z.; Duan, L.S. Effects of plant growth regulators on somatic embryo regeneration of Liriope spicata. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mayahi, A.M.W. The Efect of Phenyl Acetic Acid (PAA) on Micropropagation of Date Palm Followed by Genetic Stability Assessment. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41, 3127–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, R.; Trivedi, M. Effect of various growth hormone concentration and combination on callus induction, nature of callus and callogenic response of Nerium odorum. Appl. Biochem. Biotech. 2014, 172, 2562–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaka, N.; Kothari, S.L. Phenylacetic acid improves bud elongation and in vitro plant regeneration efficiency in Helianthus annuus L. Plant Cell Rep. 2002, 21, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | PGR concentration (mg·L−1) |

Callus proliferation (fold) |

No. somatic embryos (gFW−1) |

No. regenerated plantlets (gFW−1) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,4-D | PAA | CPA | IPA | ||||

| CK | 1 | 8.12 ± 0.19 f | 232 ± 9.61 f | 13 ± 4.50 b | |||

| P1 | 1 | 8.21 ± 0.18 f | 144 ± 11.93 i | 4 ± 0.39 ef | |||

| P2 | 5 | 8.09 ± 0.25 f | 225 ± 8.083 f | 2 ± 0.07 ef | |||

| P3 | 10 | 6.99 ± 0.18 f | 285 ± 5.86 de | 3 ± 0.73 ef | |||

| P4 | 20 | 6.18 ± 0.17 h | 366 ± 11.06 c | 3 ± 0.10 ef | |||

| P5 | 40 | 4.61 ± 0.18 j | 1131 ± 8.89 a | 11 ± 0.53 bc | |||

| P6 | 80 | 3.43 ± 0.22 k | 1028 ± 20.53 b | 13 ± 1.03 bc | |||

| C1 | 1 | 11.23 ± 0.00 c | 164 ± 1.00 h | 0 f | |||

| C2 | 5 | 10.94 ± 1.27 cd | 273 ± 6.08 e | 9 ± 0.20 cd | |||

| C3 | 10 | 12.24 ± 0.93 b | 131 ± 6.08 i | 6 ± 2.64 de | |||

| C4 | 20 | 13.25 ± 0.41 a | 289 ± 6.56 d | 0 f | |||

| C5 | 40 | 10.31 ± 0.12 d | 193 ± 1.73 g | 0 f | |||

| C6 | 80 | 3.94 ± 0.31 jk | 73 ± 4.58 k | 0 f | |||

| I1 | 1 | 9.38 ± 0.49 e | 238 ± 3.61 f | 6 ± 1.89 de | |||

| I2 | 5 | 9.46 ± 0.92 e | 293 ± 6.08 d | 46 ± 7.05 a | |||

| I3 | 10 | 6.45 ± 0.44 gh | 271 ± 6.25 e | 50 ± 5.11 a | |||

| I4 | 20 | 5.39 ± 0.67 i | 194 ± 8.72 g | 14 ± 0.88 b | |||

| I5 | 40 | 3.93 ± 0.59 jk | 106 ± 3.61 j | 5 ± 1.29 de | |||

| I6 | 80 | 1.90 ± 0.45 l | 70 ± 7.37 k | 0 f | |||

| PGR | PGR concentration (mg·L−1) |

No. somatic embryos (gFW−1) |

No. regeneration plantlets (gFW−1) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAA | KT | TDZ | PAA | CPA | IPA | |||

| CK (T3) | 0.1 | 5 | - | - | - | - | 227 ± 6.08 gh | 13 ± 2.37 e |

| PAA-KT1 | - | 5 | - | 1 | - | - | 320 ± 5.00 c | 53 ± 3.61 b |

| PAA-KT2 | - | 5 | - | 5 | - | - | 460 ± 4.00 a | 86 ± 3.61 a |

| PAA-KT3 | - | 5 | - | 10 | - | - | 215 ± 2.00 i | 29 ± 4.62 c |

| PAA-KT4 | - | 5 | - | 20 | - | - | 0 n | 0 g |

| PAA-TDZ1 | - | - | 0.5 | 1 | - | - | 0 n | 0 g |

| PAA-TDZ2 | - | - | 0.5 | 5 | - | - | 83 ± 1.00 m | 9 ± 1.53 ef |

| PAA-TDZ3 | - | - | 0.5 | 10 | - | - | 140 ± 2.00 l | 28 ± 3.46 c |

| PAA-TDZ4 | - | - | 0.5 | 20 | - | - | 340 ± 2.00 b | 85 ± 5.03 a |

| CPA-KT1 | - | 5 | - | - | - | 1 | 346 ± 15.62 b | 49 ± 7.12 b |

| CPA-KT2 | - | 5 | - | - | - | 5 | 307 ± 8.19 d | 19 ± 1.28 d |

| CPA-KT3 | - | 5 | - | - | - | 10 | 203 ± 11.27 j | 3 ± 4.99 fg |

| CPA-KT4 | - | 5 | - | - | - | 20 | 136 ± 9.54 l | 2 ± 2.71 g |

| CPA-TDZ1 | - | - | 0.5 | - | - | 1 | 227 ± 7.00 gh | 2 ± 3.34 g |

| CPA-TDZ2 | - | - | 0.5 | - | - | 5 | 215 ± 6.24 i | 2 ± 3.06 g |

| CPA-TDZ3 | - | - | 0.5 | - | - | 10 | 166 ± 5.29 k | 0 g |

| CPA-TDZ4 | - | - | 0.5 | - | - | 20 | 134 ±5.57 l | 0 g |

| IPA-KT1 | - | 5 | - | - | 1 | - | 291 ± 4.58 e | 31 ± 4.06 c |

| IPA-KT2 | - | 5 | - | - | 5 | - | 264 ± 7.00 f | 11 ± 3.80 e |

| IPA-KT3 | - | 5 | - | - | 10 | - | 217 ± 2.65 hi | 5 ± 4.17 fg |

| IPA-KT4 | - | 5 | - | - | 20 | - | 194 ± 7.00 j | 2 ± 3.33 g |

| IPA-TDZ1 | - | - | 0.5 | - | 1 | - | 231 ± 5.29 g | 3 ± 5.24 fg |

| IPA-TDZ2 | - | - | 0.5 | - | 5 | - | 195 ± 5.57 j | 2 ± 3.40 g |

| IPA-TDZ3 | - | - | 0.5 | - | 10 | - | 162 ± 5.29 k | 1 ± 2.43 g |

| IPA-TDZ4 | - | - | 0.5 | - | 20 | - | 138 ± 3.61 l | 1 ± 2.06 g |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).