1. Introduction

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is the preferred substrate in thin organic and large-area electronic (TOLAE) devices due to the combination of its optical transparency and low price [

1,

2]. For applications such as organic light emitting diodes (OLEDs) and organic- or perovskite photovoltaics (OPVs or PSC) the deposition and annealing temperatures during processing require the use of heat-stabilized (bi-axially stretched) PET (150 °C). When process temperatures up to 220 °C are required, heat-stabilized PEN can be used [

3]. Since TOLAE devices are typically extremely sensitive to degradation by the ambient, the devices have to be encapsulated with a thin film barrier stack from both top and bottom side, since the water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) of the substrate itself is at least 6 orders of magnitude too high to protect the device with a sufficient life time [

4]. From a cost and practical point of view, an unstructured roll-to-roll (R2R) deposition of each layer is preferred, directly on top of a barrier film. After completion of the device, a second barrier foil can be laminated on top and, thereby, limiting the stack to contain 2 plastic films. Compared to the more conventional 3-film approach, where a separate PET or PEN substrate is used as base for device fabrication and after which the whole stack is sealed with 2 separate barrier films, the fabrication directly on the barrier film leads to a significant cost reduction and in fact a better performance, since PET/PEN substrates by themselves contain small amounts of residual water that will degrade the device over time. For the realization of R2R thin film electronics, the individual layers have to be structured separately with a stand-alone process, such as laser ablation.

Over the last decades, laser patterning of indium tin oxide (ITO) on glass and PET substrates [

5,

6,

7,

8] has been investigated intensively for photovoltaics (PV) and display applications [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Here, the main requirement is the complete removal of the transparent conductive (TC) material in the laser track and (partial) damage to the substrate underneath is largely inconsequential. Fewer studies have investigated laser ablation of functional layers deposited directly on top of barrier films [

15,

16,

17]. Direct laser structuring of layers on top of thin-film barriers is much more challenging as selective removal of the layers is required while barrier properties are to be maintained,

i.e., no damage should occur to the thin-film barrier underneath. In particular, when a transparent layer has to be structured on top of a transparent barrier layer and no clear wavelength-selective ablation can be performed, careful tuning of the laser ablation process parameters are required, possibly in combination with tuning of the optical properties of the layers. For example, Naithani

et al. reported that selective laser ablation can be achieved by changing the optical properties of the barrier film [

18].

In a previous study, we already reported on the investigations of direct laser structuring of TC layers, the so-called P1 scribe, deposited on top of R2R produced barrier films for its use as bottom electrode in R2R PV applications [

19]. In that report, the process window for laser structuring of the TC layer was performed in such a way that a) no damage is introduced to the barrier film and b) full electrical isolation in the TC layer is achieved. During these process investigations, irregular ablation of the TC layer was observed. In this report we investigate the origin of the irregular ablation quality.

Here, we used the same stack as previously reported [

19] with the most commonly used transparent electrode material, indium tin oxide (ITO) deposited on top of a state-of-the-art R2R produced barrier film, consisting of a heat-stabilized PET substrate with an organic planarization layer (OCP, organic coating for planarization) and a single hydrogenated amorphous silicon nitride (SiN) barrier layer;

i.e. PET/OCP/SiN. The barrier films have been extensively quantified using the optical Ca-test [

20] and show an overall WVTR < 10

-6 g.m

-2.day

-1, which is determined by the intrinsic properties of the SiN due to the extremely low pinhole density present, i.e. ~ 0.03 pinholes/cm

2 (determined from 1250 cm

2 barrier film per individual barrier test). Logically, any damage induced by laser ablation, resulting in pinholes or cracks in the SiN, will have detrimental effects on overall barrier performance, resulting in fast degradation of the device processed on top.

During the laser ablation process investigations, irregular ablation of the ITO was observed. These irregularities are best described as local changes in the ablation diameter and ablation depth within a single laser track. The pattern of irregularities seems to result from a large-scale effect originating in the samples since it spans multiple laser tracks over a large area and is independent of the ablation direction. The variations along the laser tracks have a significant effect as they lead to either unwanted local barrier damage by over-ablation or insufficient isolation due to non-removed TC layer by under-ablation. Furthermore, the variations in ablation quality hamper the precise determination of a process window for highly-selective laser ablation.

Comparable laser ablation studies do not show these strong variations along the laser track, which is likely due to the fact that all have been performed with the layers directly on top of plastic substrates or glass [

6,

21,

22,

23] and damage underneath the ablation track is non-critical. In literature, laser induced damage or patterns [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29] are either ripples on the surface with a period distance which is similar to the laser wavelength range or patterns induced by the biaxial stretching of the PET, so-called naps and walls [

30]. The periodicity of these wall structures is in the range of 1 µm up to 8 µm. The patterns we observed have a periodicity at a much larger scale, in the range of 1 mm up to 1 cm. Here, we focus on the long-range laser inconsistencies that appear during the TC laser ablation and provide solutions for uniform highly-selective ablation on top of plastic substrates and barrier foils.

2. Materials and Methods

The substrate used for laser ablation was a R2R produced barrier film (WVTR < 10-6 g.m-2.day-1) with ITO as transparent conductor. The barrier film consist of a heat stabilized PET of 125 µm thickness, an organic coating for planarization (OCP) of 22.3 µm thickness and a low-temperature hydrogenated silicon nitride (SiN) inorganic barrier layer of 150 nm thickness; PET/OCP/SiN. Samples from the roll-to-roll barrier film were cut out and a 135nm thick ITO layer is deposited on the barrier film by sputtering.

A 1064 nm picosecond laser (Talisker Ultra, Coherent) was used to laser structure ITO (P1 scribe) and stop on the SiN layer. A square area of 3x3 cm was fully covered with laser scribes of 3 cm in length, with a spacing of 100 µm. To look in detail at the optical properties of the barrier films and the emerged interference patterns upon ITO ablation, Raman spectroscopy was used.

A Raman spectroscopy setup was used with a laser with 633 nm wavelength exciting the sample through an optical microscope objective. The lateral resolution and depth specificity is determined by the choice of microscope objective. The light coming back from the sample, of which the majority will be reflected laser light, is passing a filter which eliminates all light with a wavelength ≤ 633 nm. All wavelengths longer than 633 nm are detected by the system and analyzed with dedicated software.

The accompanying software can analyze the spectrum with a mathematical method by splitting up the detected spectrum in several components (so called principal components, PCs) that build up the total spectrum. Each of these components can represent a physical property of the sample. The PCs are orthogonal functions that contain the most variance in the original spectrum. The equation of the PCs can be written as follows [

31];

where

is the original Raman spectroscopy data,

,

……

are the orthogonal principle components of the original data and

,

,……

are the coordinate values or scores that project the original Raman spectroscopy on the new orthogonal principle components. When an area of a sample is scanned by Raman, the changes in each of the principal components can be plotted in a mapping by giving a colour difference for the amount of change in component. Hence, for each element or property of the spectrum (physical or mathematical) a mapping can be made of the strength or variation of that component over the sample area and we can see if the large-scale pattern that we like to analyse appears as an optical effect in the detected signal.

3. Results and Discussion

The in-house developed methodology to obtain selective ablation settings for a specific laser in combination with a specific TC layer was previously described in detail [

19] and an overview for the currently used combination of a 1064 nm picosecond laser and ITO is provided in the Supporting Information. The optimized laser settings using a 1064 nm picosecond laser for ablation of ITO on SiN barrier films, were at a fluence level of 635 mJ/cm

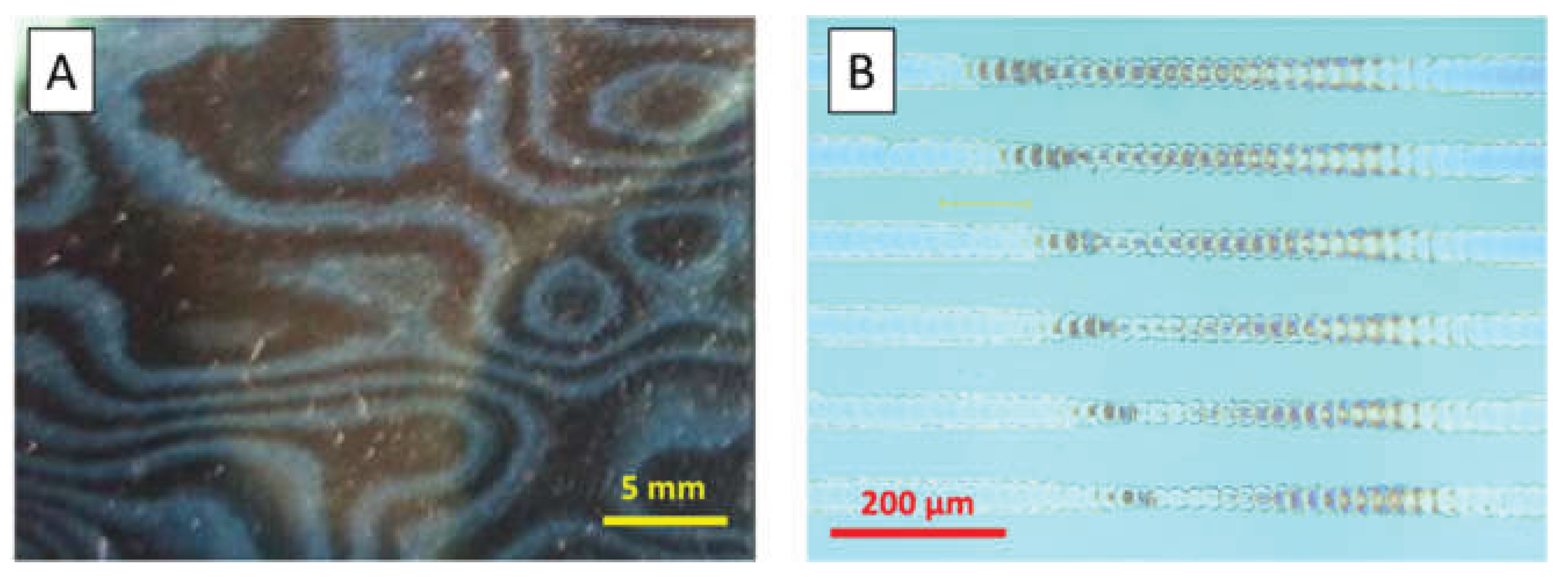

2 at 47 % pulse overlap (ablation speed 200 mm/s). When ablating at these settings an irregular ablation was observed along the laser track with locally over- and under ablation, where the SiN suffers from damage or the ITO has not been completely removed, respectively. The variable ablation behavior manifests as local changes in the ablation diameter and ablation depth within a single laser track, see

Figure 1B. The pattern of irregularities seems to result from a large-scale effect originating in the samples since it spans multiple laser tracks resulting in a large pattern, see

Figure 1A. A first assumption was that the pattern might originate due to thickness variations in the OCP coating on top of PET. The investigations by white light interferometry, see Supporting Information, clearly showed that the height variations in the samples and associated in- and out of focus of the laser spot, are not the cause for the irregular ablation quality.

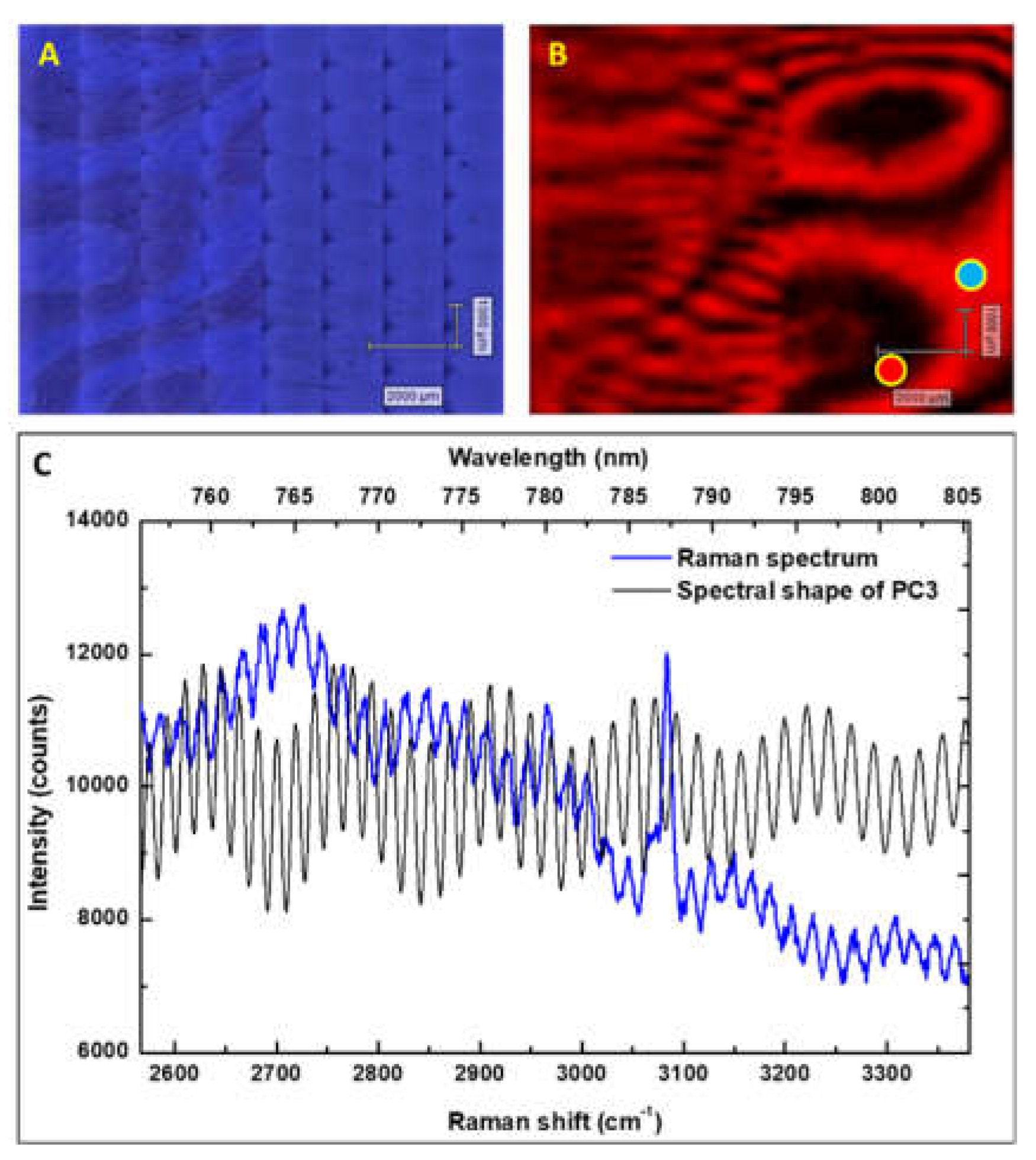

To investigate in detail the optical properties of the substrates, the laser structured samples were investigated by Raman spectroscopy. To compare a laser patterned area with the non-patterned area adjacent to it (see

Figure 2A), a large area mapping by Raman was carried out over the sample. Principal component analysis was applied to the obtained Raman spectrum.

Figure 2C shows the Raman spectrum detected from a single point (blue line). The majority of the spectrum is caused by a small fluorescence originating in the sample and the peak close to 3100 cm

-1 is a Raman peak originating from the PET substrate. The spectral shape of the principal component PC

3(λ), shown by the black line in

Figure 2C, represents the interference for the small amount of fluorescence present in the Raman spectrum. The stitched optical microscopy image obtained by the Raman setup is shown in

Figure 2A. Here, the stitched areas (repetitive dark areas) and the emerging fringe-pattern due to the laser scribing can be clearly identified. In

Figure 2B the same mapping is shown, but in this case each pixel has a colour defined by the variation observed in PC

3(λ) score. Albeit that the score mapping appears to be distorted in the laser scribed area due to the presence of laser tracks and associated rougher surface area, from the stitched optical microscopy image and the PC

3(λ) score mapping it can be observed that the emerging pattern present in the laser scribed area continues in the adjacent un-patterned area when looking at the score mapping of PC

3(λ), which is a component related to the interference in measured fluorescence.

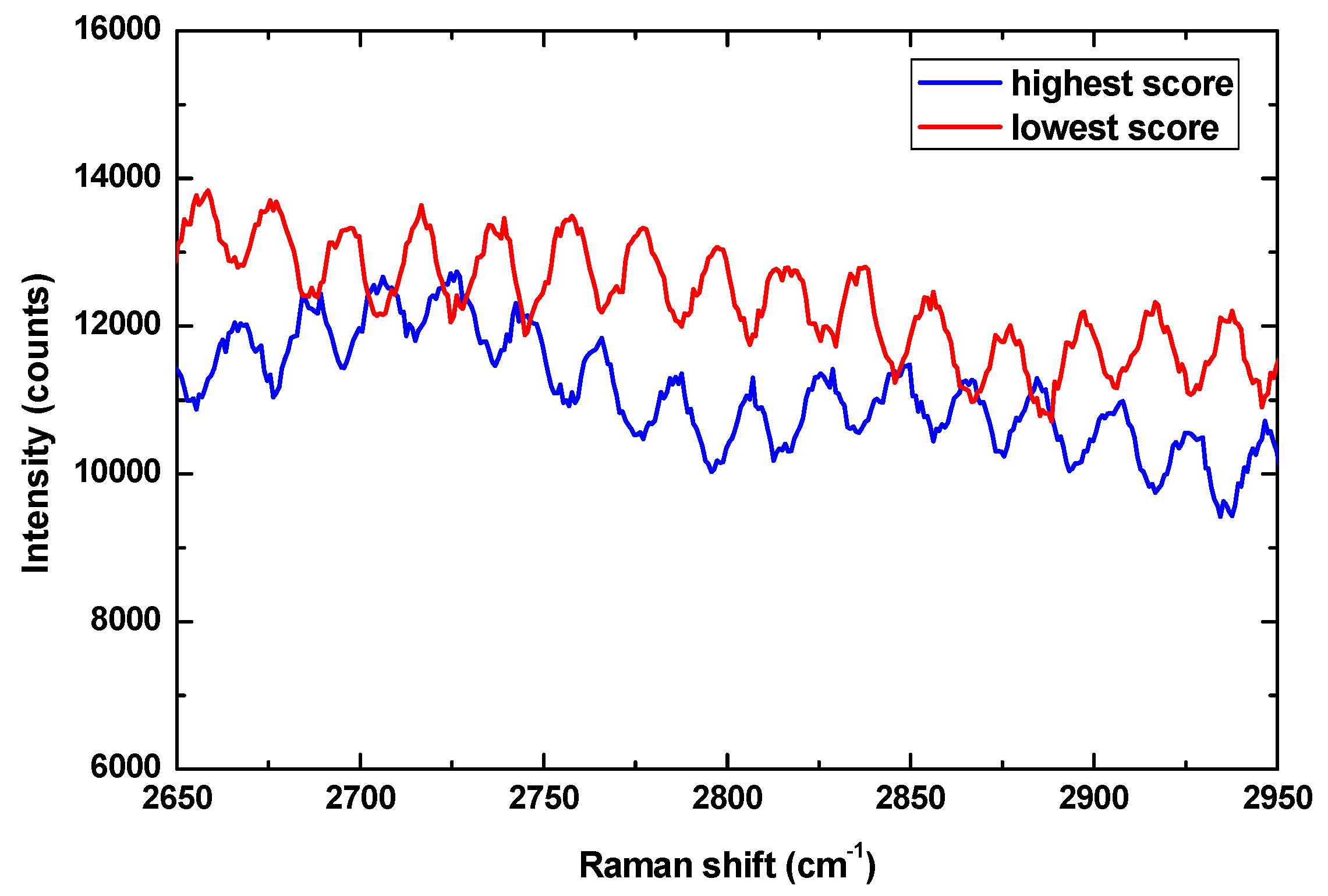

To understand the nature of the PC

3(λ) score value, the Raman spectrum was plotted for the maximum and minimum PC

3(λ) score location, shown in

Figure 3 and the actual locations on the sample are depicted by the blue and red dots in the previous

Figure 2B. In

Figure 3 only a part of the spectrum is plotted for the range 2650 – 2950 cm

-1 (corresponding to 760.6 – 778.3 nm). Besides the small difference in absolute value of the Raman spectrum at both locations, it can be observed that the interference pattern in fluorescence is present at both locations but has shifted with respect to each other. When we fit the derivative (to remove absolute value differences) of the interference pattern with a sine function, we obtain a wavelength of 20.01 +/- 0.02 cm

-1 and 20.00 +/- 0.02 cm

-1 for the highest and lowest PC

3(λ) score location, respectively. These wavelengths are identical within the error of measurement and, thereby, unrelated to the PC

3(λ) score. In fact, for the maximum and minimum location in the mapping, the shift of interference is exactly equal to half the wavelength (10 cm

-1) of the interference pattern, implying that the PC

3(λ) score gives a value for phase shift of the interference pattern in the fluorescence spectrum. More details are provided in Figure S5 and S6 in the Supporting Information .

The optical path length of a stack of layers is determined by a summation of the product of the refractive index (

n) and thickness (

d) of the individual layers:

From the number of fringes (

k) present between 2 chosen wavelengths (λ

1 and λ

2) in an interference spectrum, the

OPL can be determined by the Swanepoel method [

32], where:

For the range chosen in

Figure 3 between 2650 – 2950 cm

-1 (corresponding to

λ 1 = 760.6 nm and

λ2 = 778.3 nm) there are exactly 15 fringes (

k), resulting in an

OPL = 250.0 µm for the fluorescence. The difference in optical path length (

ΔOPL) to induce the shift in the interference spectrum can be calculated by the relative shift in wavelength of the spectrum between a peak and valley. The wavelength for the interference spectrum equals 20 cm

-1, corresponding to 1.18 nm. Hence, the difference between peak and valley is 0.59 nm and for the wavelength of 770 nm (2810.8 cm

-1) this equals to a

ΔOPL= 192 nm only, or a variation of 0.08 % in optical path length.

To determine where these variations in optical path length originate from, we also investigated bare PET substrates that were used in the fabrication of the barrier films. The Raman spectrum is provided in Figure S7 together with a spectrum of the full barrier stack with ITO. A similar large-area pattern in the PC3(λ) score mapping was obtained. As can be seen in Figure S7, the interference pattern has a slightly different periodicity due to the significant different optical path length. The wavelength for the fluorescence interference spectrum was 22.83 cm-1 (1.36 nm). By the Swanepoel method we find an optical path length for bare PET of OPLPET = 216.7 µm from the interference spectrum. When subtracting the OPLPET from that obtained on the full stack (OPL), the thickness of the OCP can be deduced using Equation 1. Using a measured refractive index of 1.50 for OCP, we obtain an OCP layer thickness of 21.9 µm, very close to the measured average value of 22.3 ± 0.1 µm (average of 72 measurements from 6 separate barrier films) and even more so when we take into account that the substrate is assumed to be exactly 125 µm in thickness based on the information provided by the supplier. The results clearly indicate that the origin of optical path length variations is present in the PET substrate.

The minute variations of 0.08% in optical path length present within the PET substrates can be the result of thickness variations (corresponding to 100 nm variations for a film of 125 µm in thickness), refractive index variations (corresponding to 0.001 variations for a refractive index of 1.58), or due to a combination of both parameters. We have determined the optical path length variation between the highest score value and lowest score value of the PC

3(λ) score mapping, which coincidentally happen to be continuously connected from a low to high value in the mapping in

Figure 2B. However, moving from the point with highest score value (blue dot,

Figure 2B) upwards, another low value ring is observed. Since the interference pattern can shift with multiple wavelengths, we cannot exclude that larger variations in the optical path length exist within the PET substrate, resulting in local minima and maxima in PC

3(λ) score mapping.

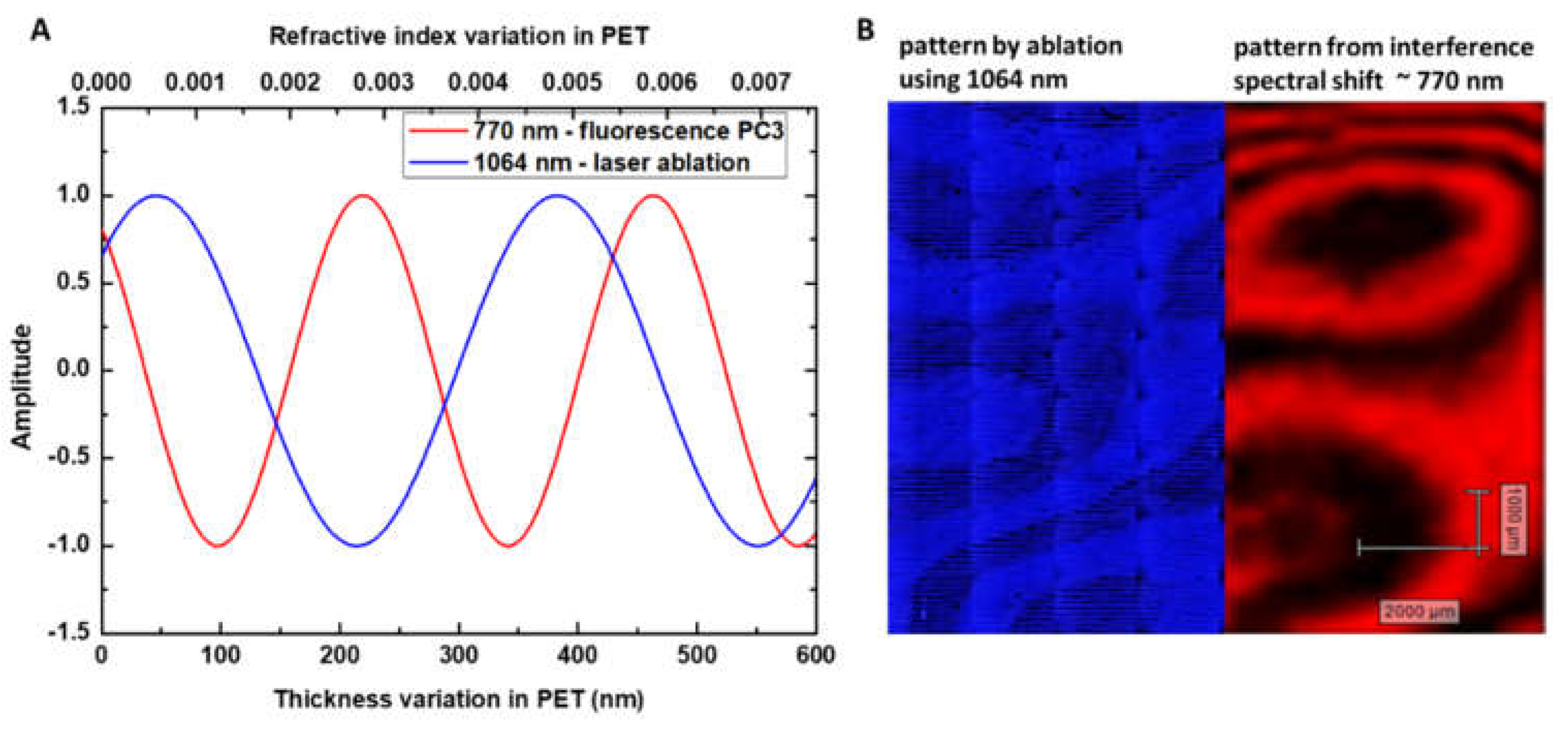

To understand how these small variations in the optical path length in the PET can influence the laser ablation uniformity, it is crucial to realize that the majority of the laser light is passing through the transparent layers and some of that light reflects from the rear of the substrate. The reflected light from the rear of the substrate can interfere with the incoming laser light of the same laser pulse (laser pulse duration is approximately 15 ps and duration for light to travel twice through the stack is about 1.5 ps). Logically, the locations where we observed maxima and minima in PC

3(λ) score from fluorescence at approximately 770 nm, will not be the same maxima and minima locations for the 1064 nm laser light source used for ablation due to the longer wavelength of the light. Furthermore, the

OPL (250.0 µm) that was determined from the interference spectrum is not identical to that of the light travelled through the stack, which can be determined using Equation 1 and resulting in 231.48 µm. Using these two wavelengths of 770 nm and 1064 nm and associated optical path lengths, we can model the phase shift of the light using a sine function provided in Equation S1 in the Supporting Information (see also Figure S6), which in case of 1064 nm resulted in constructive and destructive interference and associated variations in ablation quality. The obtained optical periodicity is represented in

Figure 4A, where the sine function for 770 and 1064 nm is plotted as a function of potential thickness variations or refractive index variations in the 125 µm PET substrate. Clearly, a different periodicity is present between the observed fluorescence interference around 770 nm and that expected for 1064 nm laser ablation, where the periodicity for 1064 nm is approximately 1.4 times larger. This also implies that the large area pattern observed by PC

3(λ) score mapping and that obtained by laser ablation are likely not identical. We verified this by combining the optical microscopy image of the 1064 nm laser patterned side of the sample in

Figure 2A with that of the ~770 nm interference shift (PC

3(λ) score) mapping at the un-patterned side in

Figure 2B. The combined image is provided in

Figure 4B. At the interface between the two images we can see that this is indeed the case; at some locations a dark area in the optical microscopy image (corresponding to more damage by ablation) lines up with low values in the PC

3(λ) score mapping and at other locations with a high value. In short, as expected, the periodicity in the large area pattern is different for both cases and the periodicity of the pattern emerging from laser ablation being larger compared to that seen in the PC

3(λ) score mapping. Albeit slightly different in periodicity, both patterns originate from the same variations in optical path length in the PET substrate.

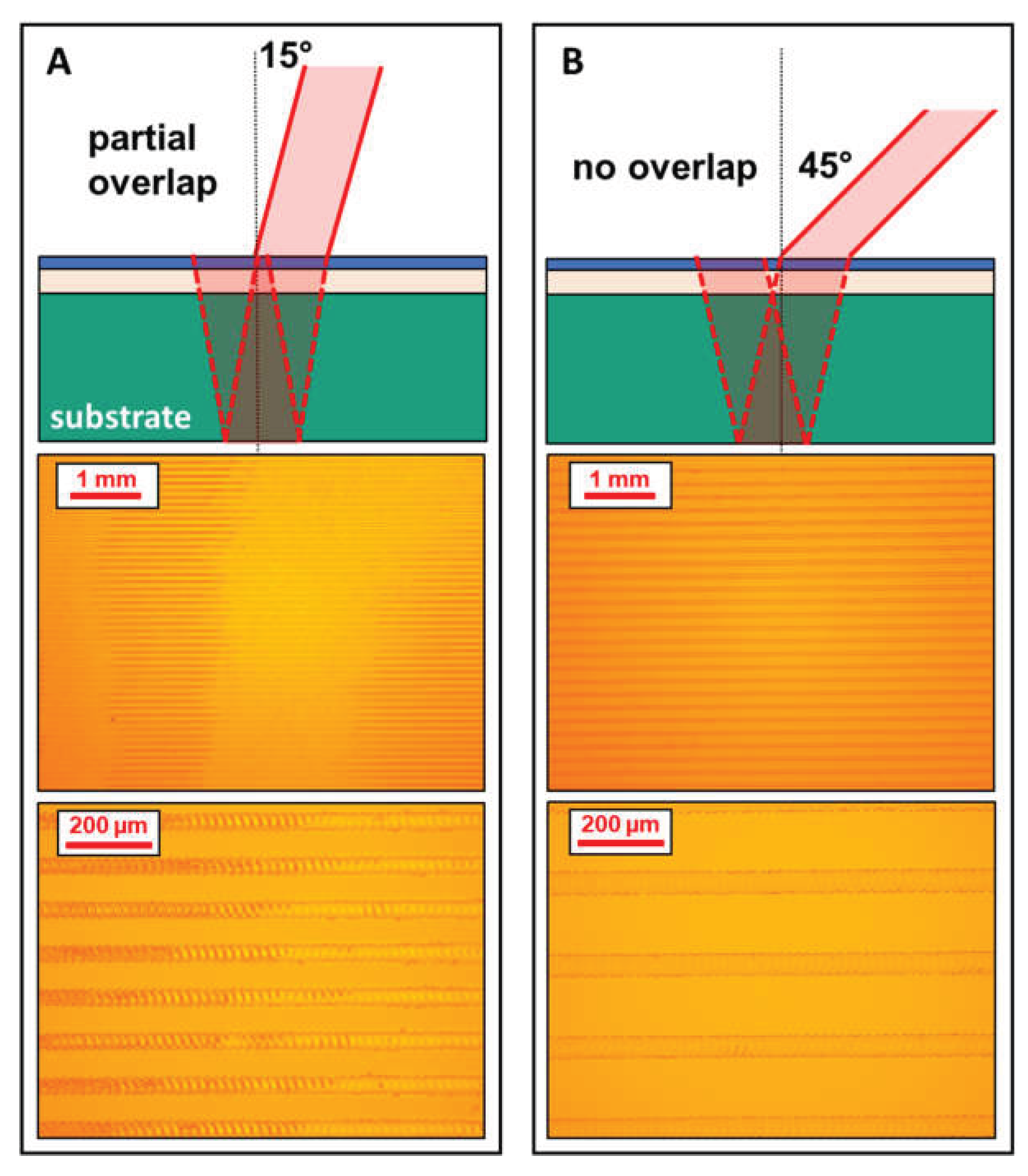

When the theory of constructive and destructive interference between incoming laser light and reflected laser light from the rear of the substrate is correct, we can try to minimize or eliminate this effect. For example, incorporating a near-infrared absorbing sacrificial layer underneath the transparent electrode could result in an optically selective ablation of the sacrificial layer together with the TC layer on top. The drawbacks for such a solution are the increased cost by increased complexity of the stack and limiting transparency in the near-infrared range for the PV application. Another possible solution could be to ensure that the light reflected from the back of the substrate is not overlapping with the incoming laser light. When this would be attempted with a scattering layer or higher substrate roughness, it would limit the transparency and possible solar cell performance, as well as the appearance of the PV product. We propose and performed a more basic solution that could be readily applied in the roll-to-roll production of PV; by performing laser ablation under an angle such that the reflected light from the back is not overlapping with the incoming laser spot. Using a 50 µm spot diameter of the laser and the thickness and refractive index of the individual layers, we can calculate the overlap at the substrate surface between incoming and reflected light. Below a 16° off-normal angle the spots overlap at the surface and above 16° no overlap is present. The results are shown in

Figure 5, where laser ablation was performed under an off-normal angle of 15°, with a partial overlap between the reflected light and incoming light, and at a 45° angle where no overlap is present. As can be seen from the optical microscopy images, the laser ablation at 15° off-normal still results in fluctuations in ablation diameter and depth, but less severe compared to the previous perpendicular ablation. At 45° the laser ablation is completely uniform over the full track and reproducible over larger areas with multiple tracks. These results not only confirm the constructive-destructive interference concept due to optical path length variations in the PET substrate, but also provide a solution that can be directly implemented for the laser patterning of roll-to-roll produced thin film stacks, without the additional need of changing the stack.