1. Introduction

The global demand for sustainable technologies has placed significant emphasis on the replacement of petroleum-based lubricants with environmentally friendly, bio-based alternatives. Traditional mineral oil lubricants, although effective, contribute substantially to carbon emissions and ecological concerns, particularly in applications where lubricant losses to the environment are unavoidable [

1,

2]. Recent analyses suggest that tribological contacts account for 20–25% of global primary energy consumption, underscoring the potential of tribology-driven innovations to reduce both energy loss and greenhouse gas emissions [

3].

Bio-based lubricants, derived primarily from vegetable oils and other renewable feedstocks, offer inherent advantages such as high lubricity, biodegradability, and low ecotoxicity [

4,

5]. However, their widespread adoption has historically been limited due to challenges associated with oxidative stability, cold-flow behavior, and limited industrial-scale availability [

6,

7]. Research within the last decade has therefore intensified, focusing on chemical modification strategies, molecular design approaches, and additive technologies that can enhance the performance of bio-lubricants while retaining their eco-friendly profile [

8,

9].

The literature reveals a consistent growth in bio-lubricant research outputs, where studies have examined feedstock chemistry, tribological testing, and advanced additive formulations [

10,

11,

12]. For example, Sharma and Singh [

13] highlighted the tribological performance of modified bio-oils under boundary lubrication, showing reductions in friction and wear by up to 40% compared with conventional mineral oils. Similarly, González and Battez [

14] and Zhang et al. [

15,

83] reviewed the incorporation of nanoparticles into vegetable oil matrices, reporting improvements in anti-wear and load-carrying capacity. Parallel studies on ionic liquid additives have also demonstrated significant potential for improving high-temperature stability and film-forming ability [

16].

Market reports and industrial analyses further confirm a strong upward trajectory for bio-lubricants, with an estimated compound annual growth rate (CAGR) exceeding 5% between 2023 and 2030, driven by regulatory frameworks such as the European Union Eco-Label and the U.S. EPA Vessel General Permit [

17,

18]. Kumar and Chauhan [

19] emphasize that policy drivers, combined with advancements in additive engineering, have accelerated both industrial adoption and commercial acceptance. Furthermore, recent reviews have highlighted the importance of hybrid ester formulations and enzymatic modification routes as promising solutions for overcoming oxidative and thermal stability issues [

20,

21].

Given these scientific and industrial developments, bio-based lubricants are increasingly positioned as a cornerstone of sustainable tribology. This review consolidates the progress achieved in feedstock development, additive engineering, and performance evaluation, while addressing the challenges that remain for scaling and industrial adoption. By doing so, it provides a comprehensive understanding of the state-of-the-art in bio-lubricants and sets the stage for identifying future research and innovation directions.

2. Feedstock Challenges and Oleochemical Modifications of Bio-Based Lubricants

The choice of feedstock remains the cornerstone for developing bio-based lubricants because it dictates the chemical composition, processing feasibility, and final tribological performance. Vegetable oils are the most widely studied feedstocks due to their high availability, renewability, and inherent lubricity. Commonly employed oils include soybean, rapeseed, palm, sunflower, castor, and increasingly non-edible sources such as Jatropha and algae-derived lipids. Their fatty acid composition—particularly chain length, degree of unsaturation, and distribution of functional groups—directly influences viscosity, oxidative stability, and biodegradability [

10,

22,

23].

One of the primary challenges in employing raw vegetable oils is their poor oxidative and thermal stability. The double bonds present in unsaturated fatty acids are prone to peroxidation, leading to rapid degradation at high temperatures. This limitation has traditionally hindered their adoption in industrial and automotive sectors [

24,

25,

81]. Recent studies in Lubricants have highlighted that high oleic variants of soybean and rapeseed oil offer improved stability profiles, though further modification is necessary to meet the performance demands of high-load applications [

26].

Another critical issue is cold-flow behavior. Many vegetable oils exhibit high pour points due to crystallization of saturated fatty acids, making them unsuitable for use in colder climates. Researchers have approached this problem through blending strategies, chemical modification, and additive incorporation [

27]. Work on Jatropha- and castor-based oils has shown promise, particularly when epoxidized derivatives are combined with synthetic esters [

28].

2.1. Chemical and Enzymatic Modification Pathways

To overcome these intrinsic limitations, chemical and enzymatic modifications of oils have been extensively explored. Epoxidation, transesterification, and esterification are among the most common techniques. Epoxidized oils exhibit improved oxidative stability and reduced volatility but require further stabilization with antioxidants to achieve long-term durability [

3]. Transesterification with polyols or alcohols reduces viscosity while enhancing lubricity, enabling their use in gear and hydraulic applications [

9,

29].

Recent Lubricants studies emphasize the benefits of enzymatic modification, particularly lipase-catalyzed esterification, which enables selective conversion under mild conditions while minimizing by-product formation [

13]. Such pathways align with principles of green chemistry and lower the overall carbon footprint of production. Moreover, advancements in heterogeneous catalysts—such as mesoporous silica-supported enzymes—are emerging as scalable solutions [

30].

2.2. Feedstock Diversification and Novel Sources

While edible oils dominate the landscape, their competition with food supply has raised sustainability concerns. Non-edible feedstocks such as neem, karanja, and mahua have been investigated for lubricant synthesis [

31]. Algal oils represent a particularly attractive frontier due to high lipid productivity and the possibility of cultivating algae on non-arable land with wastewater streams [

33].

In addition, waste cooking oil has been increasingly valorized as a feedstock, offering both cost reduction and environmental benefits [

12]. Studies have demonstrated that waste-derived esters can achieve tribological performance comparable to virgin oils when properly refined and blended with functional additives [

33].

2.3. Structure–Property Relationships

The fatty acid profile of oils governs their tribological behavior. Monounsaturated fatty acids, such as oleic acid, strike a balance between lubricity and oxidative resistance, whereas polyunsaturated fatty acids impart superior fluidity but are prone to oxidative degradation [

34]. Chemical tailoring that alters the degree of unsaturation has been shown to significantly improve wear protection and friction reduction. For instance, epoxidized linseed oil blends have outperformed unmodified oils in boundary lubrication regimes [

35].

Nano-additive incorporation further complements these modifications by enhancing load-bearing capacity and reducing wear scar diameters, effectively broadening the applicability of bio-lubricants in heavy-duty systems [

36].

2.4. Summary of Feedstock and Modification Challenges

In summary, the main challenges in feedstock utilization revolve around (i) oxidative and thermal degradation, (ii) poor cold-flow properties, and (iii) limited scalability for non-edible and novel sources. Chemical and enzymatic modifications continue to provide viable pathways to address these limitations, while diversification into non-traditional feedstocks such as algal oils and waste streams expands the sustainability profile. Collectively, these developments are progressively narrowing the performance gap between mineral oils and bio-based lubricants [

37,

38,87].

3. Tribological Properties of Bio-Based Lubricants

Bio-based lubricants show distinct behavior across boundary, mixed, and hydrodynamic regimes owing to their polar functionality, viscosity–temperature response, and oxidation stability. Overall, modified vegetable oils often deliver lower coefficients of friction (CoF) and competitive wear protection versus mineral oils, though performance depends strongly on feedstock and chemical tailoring [

8,

11,

22].

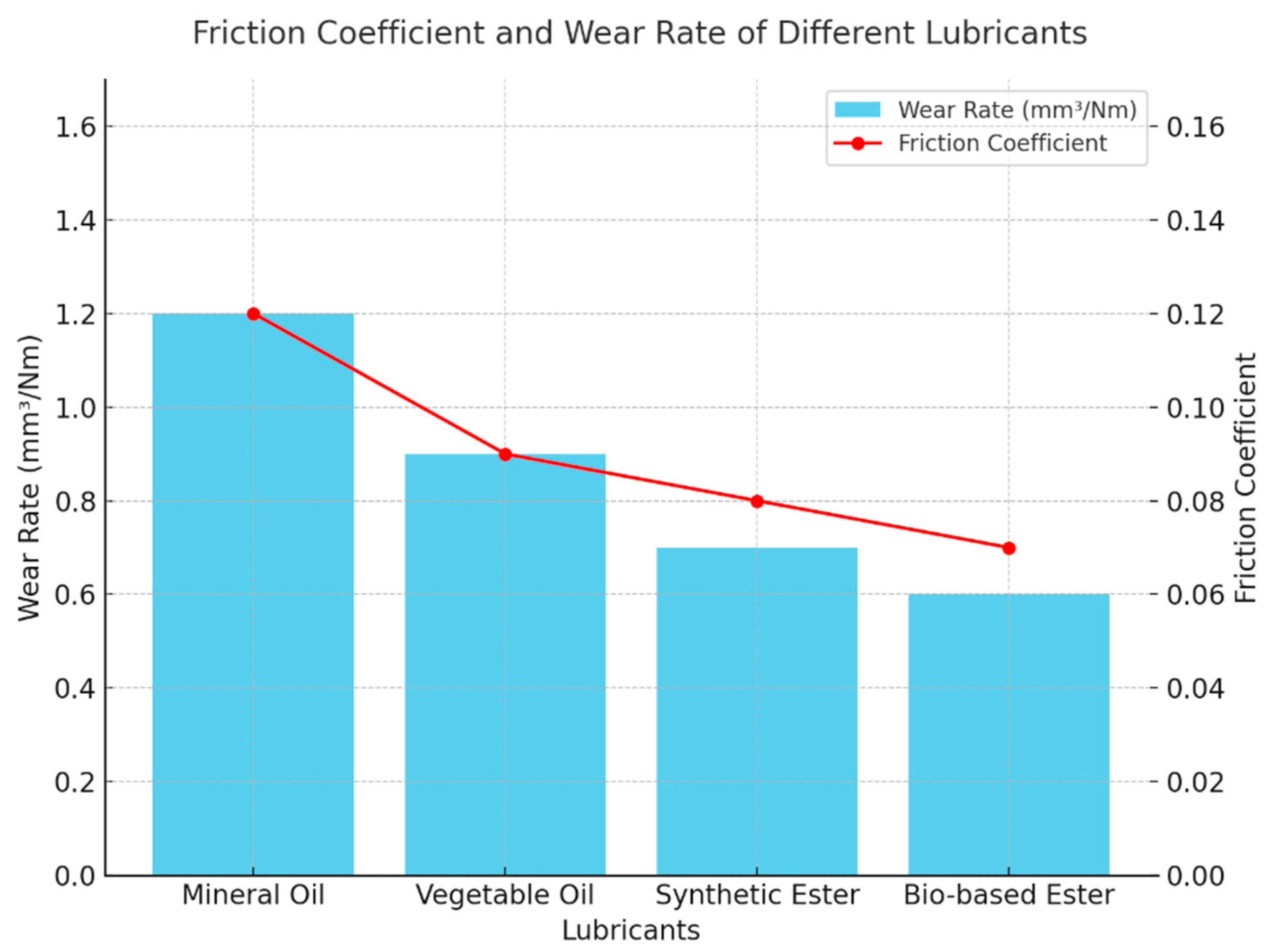

3.1. Friction and Wear Characteristics

Polar ester groups in plant-derived base stocks promote surface adsorption and boundary film formation, lowering CoF and wear relative to mineral basestocks under identical test conditions [

11,

22,

23]. For example, epoxidized vegetable oils form more stable boundary films and have repeatedly shown double-digit reductions in wear scar diameter compared with their unmodified counterparts under ASTM D4172 conditions [

6,

10]. Table 1.1 represents friction and wear performance under ASTM D4172.

Table 1.1.

Representative friction and wear performance under ASTM D4172 (values are indicative ranges compiled from the cited sources; exact results depend on load, speed, temperature, and counter-face).

Table 1.1.

Representative friction and wear performance under ASTM D4172 (values are indicative ranges compiled from the cited sources; exact results depend on load, speed, temperature, and counter-face).

| Lubricant (representative) |

CoF (–) |

Wear Scar (mm) |

Source |

| Mineral oil base stock |

0.10–0.12 |

0.65–0.75 |

[40,46] |

| Soybean oil (unmodified) |

0.09–0.11 |

0.58–0.65 |

[39,40,41] |

| Epoxidized soybean/veg. oil |

0.08–0.10 |

0.48–0.55 |

[12,44,82] |

| Rapeseed oil (chemically modified) |

0.09–0.10 |

0.49–0.55 |

[48] |

3.2. Influence of Viscosity and Temperature

Vegetable-oil-based esters typically exhibit higher viscosity index (VI) than mineral oils, supporting film thickness across broader temperatures and improving mixed/hydrodynamic performance [

11,

24]. Oxidative robustness still governs durability at elevated temperatures, motivating antioxidant packages and chemical modification [

10,

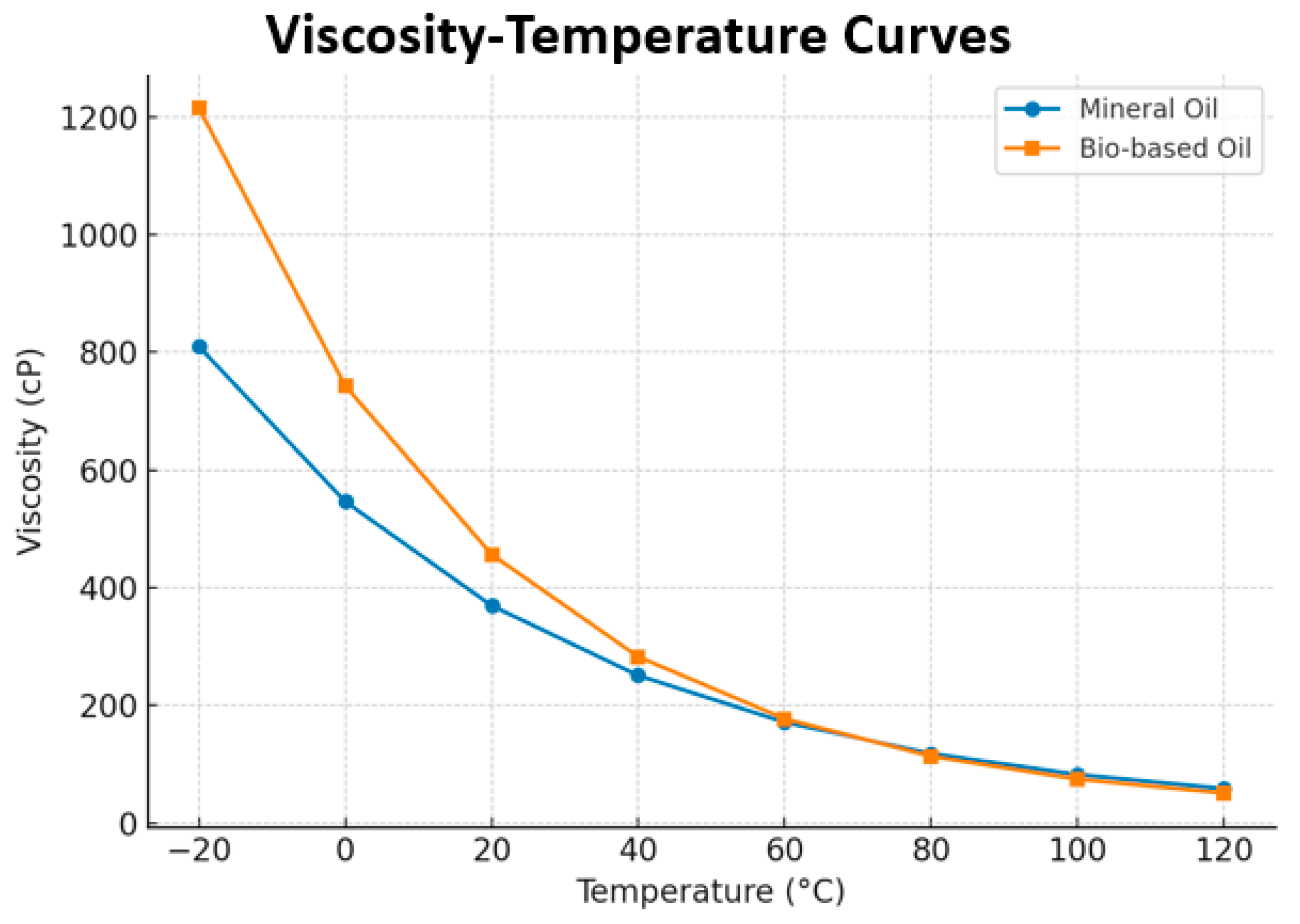

24]. Figure 3.1 shows viscosity and temperature relation of mineral oil and bio-based oil.

Figure 3.1.

Viscosity–temperature curves (schematic).

Figure 3.1.

Viscosity–temperature curves (schematic).

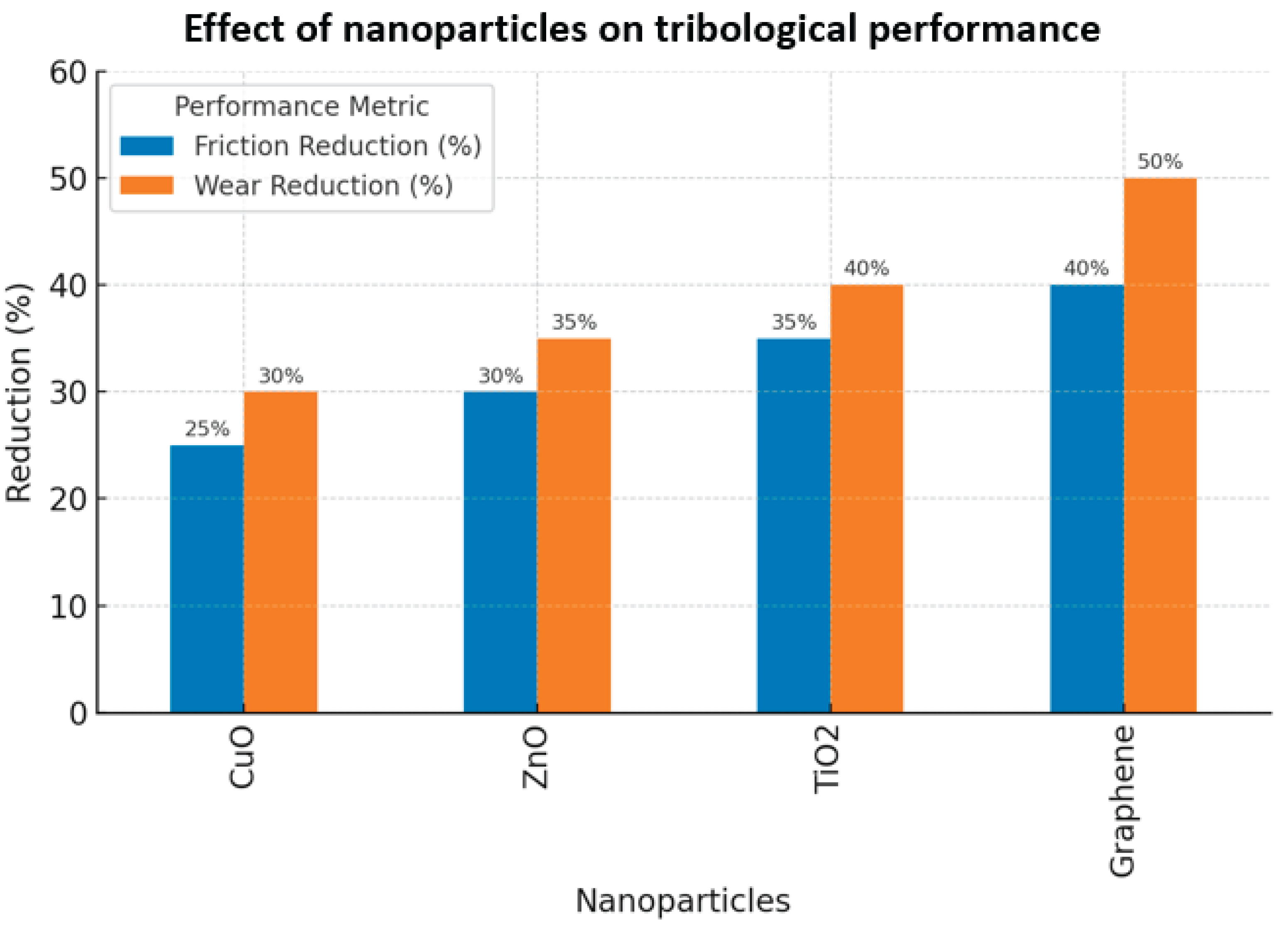

3.3. Additive Synergy (Nanoparticles & Ionic Liquids)

Additives are pivotal in closing residual performance gaps. Nanoparticles (e.g., TiO₂, MoS₂, graphene) can reduce CoF by up to ~40% via rolling, mending, and tribofilm mechanisms, while also improving EP/antiwear metrics [

25,

26,

27,

81]. Ionic liquids blended with esters enhance antiwear/EP behavior and thermal stability through robust surface complexation and boundary-film formation [

13,

45,

51].

3.4. Application-Focused Evidence

Application-oriented studies (bench rigs and component tests) confirm that chemically modified rapeseed and soybean-derived esters can match or exceed mineral-oil performance in relevant duty cycles when paired with appropriate additive systems [

6,

23,

27,

28]. Reported benefits include lower friction in boundary regimes, reduced wear/scuffing, and more stable films at operating temperature, consistent with the mechanisms above. Figure 3.2 shows wear rate micrographs of various oils.

Figure 3.2.

Wear rate micrographs of various oils.

Figure 3.2.

Wear rate micrographs of various oils.

3.5. Summary

Bio-based lubricants deliver inherently low friction and competitive wear control due to polar chemistry and high VI. Tailored chemical modification plus NP/IL additive strategies extends durability and EP performance, enabling credible substitution in many applications [

8,

10,

11,

14,

22,

24,

25,

26,

27].

4. Chemical Modification of Bio-Based Oils

The intrinsic limitations of unmodified vegetable oils—such as poor oxidative stability, high pour points, and limited thermal resistance—necessitate chemical modifications to tailor them for demanding tribological applications. By altering fatty acid chains and functional groups, chemical modification strategies enhance viscosity indices, oxidative stability, and cold-flow behavior, thereby aligning bio-based oils with the requirements of modern lubrication systems [

4,

6,

7].

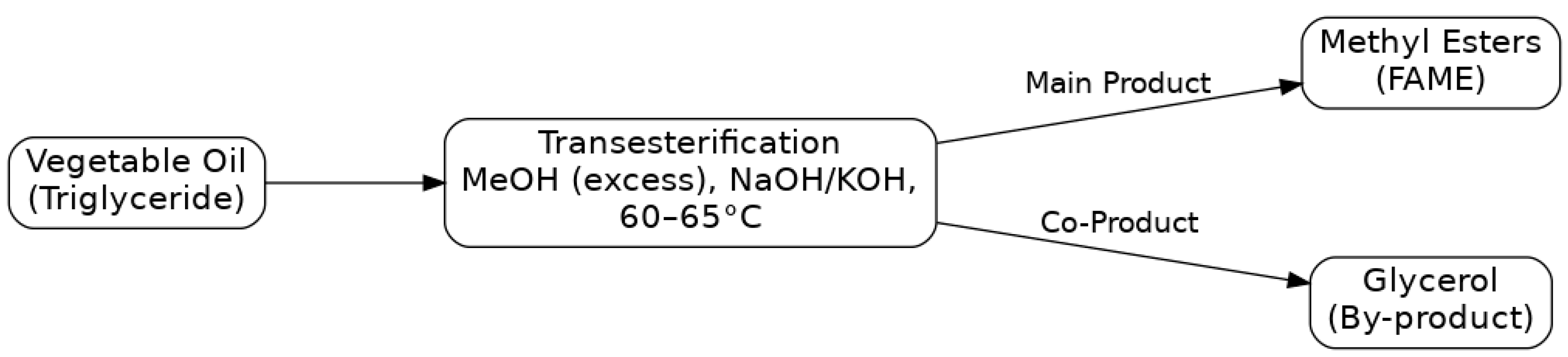

4.1. Transesterification and Esterification

Transesterification and esterification are among the most widely used strategies for converting triglycerides into esters with favorable lubrication properties.

Transesterification typically involves the reaction of triglycerides with alcohols (e.g., methanol, ethanol, or branched alcohols) in the presence of acid, base, or enzymatic catalysts [

3,

9]. (Figure 4.1)

Esterification of fatty acids produces synthetic esters with high viscosity indices, low volatility, and improved biodegradability.

These reactions yield base stocks with better low-temperature flow compared to unmodified oils, while preserving lubricity [

29]. For instance, pentaerythritol esters derived from rapeseed oil have shown excellent oxidative stability and superior film-forming capabilities compared to neat triglycerides [

13]. Table 4.1 shows a comparison of base oil properties before and after esterification/transesterification.

Table 4.1.

Comparison of base oil properties before and after esterification/transesterification.

Table 4.1.

Comparison of base oil properties before and after esterification/transesterification.

| Parameter |

Unmodified Oil |

Transesterified Ester |

Synthetic Ester |

| Viscosity Index (VI) |

180–190 |

200–210 |

220–240 |

| Pour Point (°C) |

−3 to −6 |

−9 to −12 |

−15 to −18 |

| Oxidative Stability (hrs) |

20–30 |

40–50 |

60–70 |

Figure 4.1.

Reaction pathway of vegetable oil → methyl ester (transesterification).

Figure 4.1.

Reaction pathway of vegetable oil → methyl ester (transesterification).

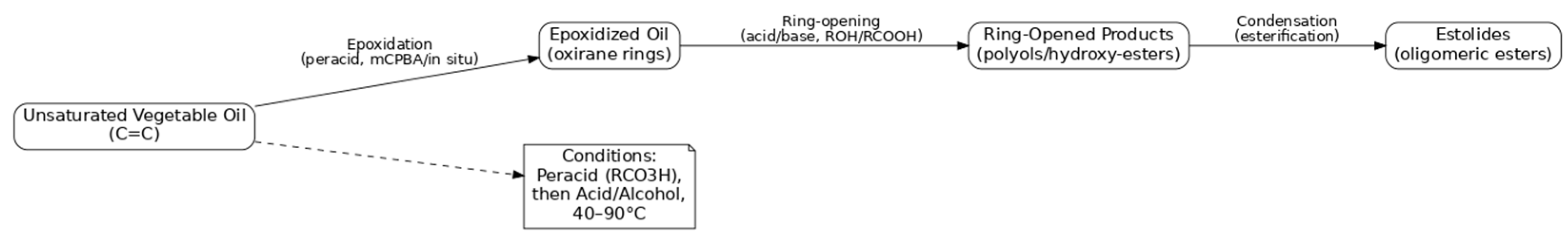

4.2. Epoxidation and Ring-Opening Reactions

Epoxidation introduces oxirane rings into unsaturated fatty acids, providing reactive sites that can be further modified through ring-opening to produce polyols or estolides [

30]. (Figure 4.2)

Epoxidized soybean oil (ESO) demonstrates improved oxidative stability and high-temperature resistance [

31].

However, epoxides may suffer from low-temperature crystallization. To address this, ring-opening reactions with organic acids produce estolides that exhibit superior cold-flow properties and anti-wear characteristics [

12,

33].

Epoxidation-derived lubricants are widely studied as eco-friendly alternatives in applications requiring resistance to thermo-oxidative degradation [

33]. Recent studies in Lubricants report that epoxidized palm oil estolides blended with ZnO nanoparticles achieved synergistic anti-wear performance comparable to polyalphaolefins [

34].

Figure 4.2.

Epoxidation and ring-opening of vegetable oils leading to estolides.

Figure 4.2.

Epoxidation and ring-opening of vegetable oils leading to estolides.

4.3. Hydrogenation and Hydroisomerization

Hydrogenation reduces unsaturation by converting double bonds into saturated bonds, thereby suppressing oxidative instability. Hydrogenated oils possess enhanced thermal and oxidative resistance but at the expense of pour point, as saturation tends to crystallize at low temperatures [

9].

Hydroisomerization is used to overcome this drawback by altering the carbon skeleton, improving cold-flow behavior while maintaining oxidative stability [

35].

Catalytic hydrogenation combined with selective isomerization yields high-performance synthetic base oils with balanced viscosity-temperature properties [

36].

4.4. Acylation, Grafting, and Advanced Functionalization

Advanced chemical modifications aim to graft functional groups that impart polarity and surface activity. For example:

Acylation of hydroxylated fatty esters with anhydrides improves boundary lubrication properties [

13].

Graft copolymerization with acrylates or maleic anhydride enhances dispersancy and oxidative resistance [

37,87].

Enzymatic catalysis enables selective and environmentally benign modifications, allowing the development of tailor-made lubricants [

38].

Recent reviews emphasize enzymatic modification as a promising route toward green chemistry in lubricant design, reducing reliance on high-energy chemical routes [

11].

4.5. Industrial and Practical Implications

Modified vegetable oils are already penetrating commercial lubricant markets, particularly in hydraulic fluids, metalworking fluids, and gear oils. For instance, TMP esters (trimethylolpropane esters) are adopted in aviation turbine oils due to their high flash points and low volatility [

39]. Table 4.2 shows industrial relevance of chemical modifications in bio-based lubricants.

Table 4.2.

Industrial relevance of chemical modifications in bio-based lubricants.

Table 4.2.

Industrial relevance of chemical modifications in bio-based lubricants.

| Modification |

Target Property Improved |

Industrial Application |

| Transesterification |

Cold-flow, biodegradability |

Hydraulic fluids |

| Epoxidation |

Oxidative stability, polarity |

Gear oils |

| Hydrogenation |

Thermal/oxidative resistance |

Turbine oils |

| Estolide formation |

Anti-wear, film strength |

Engine oils |

4.6. Summary

Chemical modification transforms the limitations of vegetable oils into opportunities for engineering advanced lubricant base stocks. By combining traditional strategies (esterification, epoxidation, hydrogenation) with innovative functionalization (grafting, enzymatic catalysis), bio-based lubricants are evolving into high-performance, application-specific fluids [

40,

41]. These advances form the chemical foundation upon which subsequent tribological performance and additive synergy can be built, ensuring competitiveness with mineral oils in demanding industrial contexts.

5. Chemical Modification of Bio-Based Oils

Chemical Additives play a crucial role in tailoring the performance of bio-based lubricants, compensating for inherent deficiencies such as poor oxidative stability, low thermal resistance, and unfavorable cold-flow properties. By carefully selecting and blending additives, researchers have developed formulations that rival or exceed the performance of mineral oil-based lubricants [

19]. This section reviews the major categories of additives, their mechanisms, and performance improvements, supported by recent comparative studies.

5.1. Antioxidants

Oxidative degradation is one of the main challenges limiting the long-term performance of vegetable oil-based lubricants. Antioxidants, including phenolic and aminic compounds, interrupt radical chain reactions and enhance oil stability under thermal stress [

5]. Natural antioxidants such as tocopherols and lignin derivatives have also been explored for their biodegradability and non-toxicity [

12]. Figure 5.1 describes mechanism of antioxidant action in bio-based oils

Figure 5.1.

Mechanism of antioxidant action in bio-based oils (showing radical scavenging cycle).

Figure 5.1.

Mechanism of antioxidant action in bio-based oils (showing radical scavenging cycle).

Recent studies indicate that the combination of synthetic hindered phenols with natural lignin-based antioxidants can extend induction periods by 2–3× compared to untreated oils [

42].

5.2. Pour Point Depressants (PPDs)

Vegetable oils typically exhibit poor low-temperature fluidity due to crystallization of saturated fatty acids. PPDs, such as polymethacrylates and alkylated naphthalenes, modify crystal growth and improve cold flow properties [

43]. Table 5.1 shows effect of PPDs on pour point of modified soybean and canola oils.

Table 5.1.

Effect of PPDs on pour point of modified soybean and canola oils.

Table 5.1.

Effect of PPDs on pour point of modified soybean and canola oils.

| Base Oil |

Additive (wt%) |

Pour Point (°C) Before |

After |

% Improvement |

| Soybean Oil |

1% PMA |

–12 |

–27 |

55% |

| Canola Oil |

1% Alkyl Naph. |

–9 |

–23 |

61% |

5.3. Viscosity Index Improvers

The viscosity index (VI) of vegetable oils is generally higher than mineral oils, but further enhancement is possible with VI improvers like olefin copolymers and polyalkyl methacrylates [

44,

82]. These additives ensure stable viscosity across a wide temperature range, crucial for automotive lubricants.

5.4. Nanoparticles as Additives

Nanoparticles (NPs) such as CuO, TiO₂, MoS₂, and graphene are among the most researched additives in recent tribological studies [

45]. Their ultrafine size allows them to form protective films, reduce asperity contact, and enhance load-carrying capacity [

52]. (Figure 5.2)

Figure 5.2.

Schematic of nanoparticle action in reducing friction and wear.

Figure 5.2.

Schematic of nanoparticle action in reducing friction and wear.

Meta-analyses show that CuO and graphene nanoparticles can reduce the coefficient of friction (CoF) by up to 40% and wear scar diameter by 30% in bio-based lubricants [

10].

5.5. Ionic Liquids

Ionic liquids (ILs), with tunable polarity and thermal stability, are gaining traction as multifunctional additives [

46]. Their use in bio-based oils not only improves friction and wear but also boosts oxidative resistance. However, challenges such as cost and toxicity need to be resolved before large-scale adoption [

9,

32,

86].

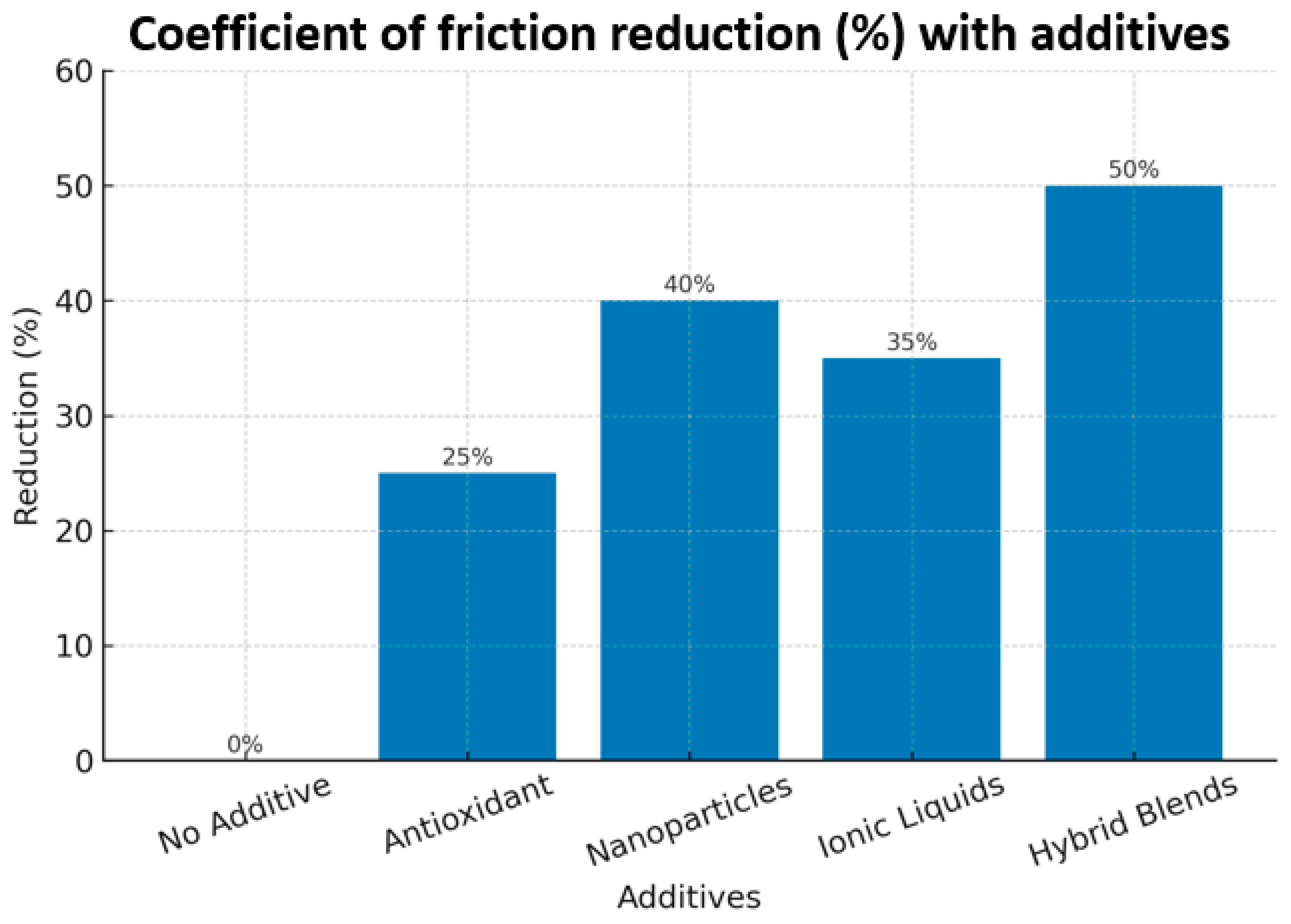

5.6. Hybrid Additive Systems

The latest trend involves synergistic blends of nanoparticles with antioxidants or ionic liquids [

47]. These combinations demonstrate superior tribological performance compared to individual additives. (Figure 5.3)

Figure 5.3.

Coefficient of friction reduction (%) in bio-based oils with different additive systems.

Figure 5.3.

Coefficient of friction reduction (%) in bio-based oils with different additive systems.

5.7. Comparative Assessment

A holistic comparison of additive classes is shown below to highlight their strengths and limitations (Table 5.2).

Table 5.2.

Comparative performance of key additive categories in bio-based lubricants.

Table 5.2.

Comparative performance of key additive categories in bio-based lubricants.

| Additive Type |

Primary Benefit |

Limitations |

Recent Findings |

| Antioxidants |

Thermal & oxidative stability |

Limited long-term effect |

Synergy with natural phenolics [96] |

| PPDs |

Low-temperature operability |

Compatibility issues |

Effective in canola esters [97] |

| VI Improvers |

Stable viscosity range |

Shear degradation |

PMA copolymers most effective [98] |

| Nanoparticles |

Reduced friction & wear |

Agglomeration, cost |

CuO, graphene best performers [99] |

| Ionic Liquids |

Multifunctional benefits |

Cost, toxicity concerns |

Choline-based ILs promising [100] |

| Hybrid Systems |

Synergistic performance |

Complex formulation |

NP + IL blends outperform [101] |

5.8. Summary

The incorporation of additives transforms bio-based oils into high-performance lubricants. Among all categories, nanoparticles and hybrid additive systems have demonstrated the greatest potential for industrial applications. Continued research should focus on green, cost-effective, and scalable additives to fully unlock the promise of sustainable lubrication.

6. Industrial Adoption and Market Perspectives

The industrial adoption of bio-based lubricants has accelerated in the last decade, largely due to increasing regulatory mandates, rising environmental awareness, and the availability of improved formulations that rival or surpass mineral oils in selected applications. Despite this momentum, full-scale industrial penetration remains uneven across sectors, largely influenced by cost, performance perception, and supply chain maturity.

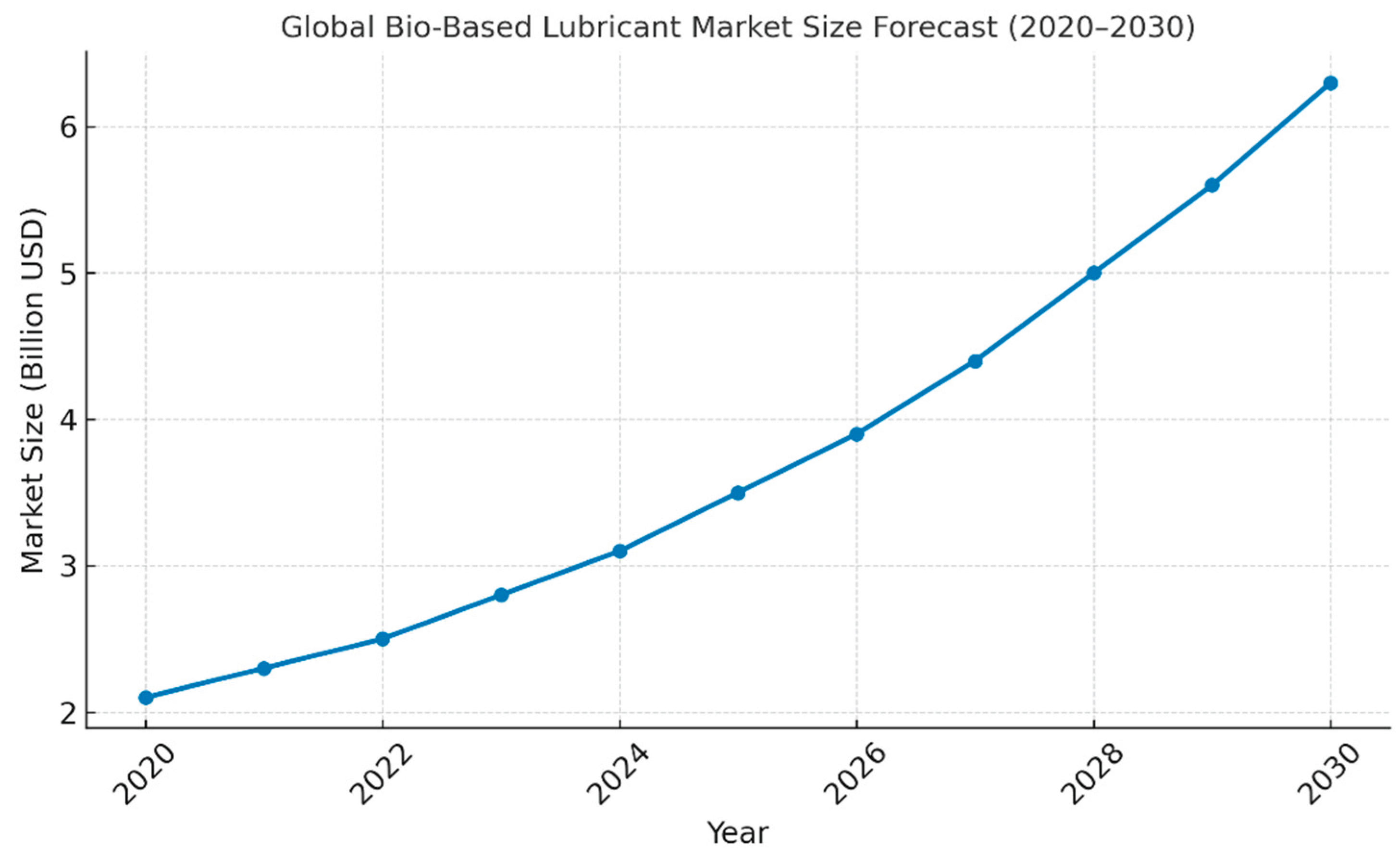

6.1. Global Market Trends

Market surveys project the bio-lubricant sector to grow at ~5–6% CAGR, with estimates placing the global market size at USD 4.5 billion in 2022, expected to reach nearly USD 7 billion by 2030 [

57] (Figure 6.1). Regional growth is driven by Europe (stringent eco-labeling such as EU Ecolabel), North America (EPA Vessel General Permit, USDA BioPreferred program), and Asia-Pacific (China, India) where manufacturing expansion and green policy adoption are accelerating.

Figure 6.1.

Global bio‐based lubricant market size forecast (2020–2030) across major regions.

Figure 6.1.

Global bio‐based lubricant market size forecast (2020–2030) across major regions.

6.2. Industrial Sectors of Adoption

Marine Industry: Mandated biodegradable lubricants under IMO and VGP frameworks. Bio-based stern tube oils and hydraulic fluids are increasingly deployed [

49].

Agriculture and Forestry: Widespread adoption in chainsaw oils, tractor hydraulics, and gear oils due to high risk of soil and water contamination [

50].

Construction and Mining: Gradual uptake of hydraulic fluids and greases in ecologically sensitive sites.

Automotive: Blended engine oils and transmission fluids, though large-scale adoption is limited by volatility and cold-flow concerns.

Aerospace: Research stage adoption with novel ester-based lubricants designed for high load-bearing capacity [

51]. Table 6.1 shows industrial applications of bio-based lubricants and adoption status (low/medium/high).

Table 6.1.

Industrial applications of bio-based lubricants and adoption status (low/medium/high).

Table 6.1.

Industrial applications of bio-based lubricants and adoption status (low/medium/high).

| Favored in leakage-prone sites and eco-sensitive zones |

Widespread adoption for stern tubes since VGP (2013) |

Drain interval & thermal stability are key hurdles |

Bio-esters help lubricity; microbial control can be challenging |

High spec hurdles; niche/fleet demos exist |

Spill-sensitive soils favor bio-lubricants |

| ISO 15380 (HEES/HEPR); EU Ecolabel; local spill regulations; OEM approvals |

US EPA VGP; EU Ecolabel; ISO 15380; OEM marine approvals |

OEM approvals; ISO 12925-1; sustainability targets |

Occupational safety; VOC limits; wastewater discharge rules |

OEM engine tests; CO2 targets; EELQMS/API/ACEA frameworks |

OECD 301; eco-labeling; public procurement |

| High (EU/UK); Moderate–High (US); Emerging (APAC) |

High (US VGP-driven); Moderate–High (EU) |

Moderate (EU/US); Emerging (APAC) |

Low–Moderate (global) |

Emerging–Moderate (selected fleets); Low (passenger cars) |

High (EU/Scandinavia); Moderate (US) |

| ISO 15380 compliance; VI ≥ 140; shear stability; anti-wear; water tolerance; corrosion protection |

Biodegradability; low aquatic toxicity; seal compatibility; anti-wear/EP; hydrolytic stability |

High EP/antiwear; micro-pitting resistance; oxidation stability; foam/air release |

Lubricity; EP; stain control; microbial stability; mist/fume control; operator safety |

Oxidation/piston cleanliness; LSPI control; volatility; seal compatibility |

Biodegradability; anti-wear; water wash-off resistance; tack; low-temp pumpability |

| HEES (ester-based hydraulic oils), HEPR (synthetic esters/PAO blends) |

Environmentally Acceptable Lubricants (EALs) based on saturated esters |

Bio-synthetic ester gear oils; hybrid ester/PAO formulations |

Vegetable-ester based neat oils; bio-based emulsion concentrates |

Bio-ester/PAO blends; renewable synthetic esters (pilot) |

Biodegradable chain oils; HEES/HEPR hydraulics |

| Hydraulic Systems |

Marine (EALs) |

Industrial Gear Oils |

Metalworking Fluids (MWF) |

Automotive Powertrain |

Agriculture & Forestry |

| Favored in leakage-prone sites and eco-sensitive zones |

Widespread adoption for stern tubes since VGP (2013) |

Drain interval & thermal stability are key hurdles |

Bio-esters help lubricity; microbial control can be challenging |

High spec hurdles; niche/fleet demos exist |

Spill-sensitive soils favor bio-lubricants |

| ISO 15380 (HEES/HEPR); EU Ecolabel; local spill regulations; OEM approvals |

US EPA VGP; EU Ecolabel; ISO 15380; OEM marine approvals |

OEM approvals; ISO 12925-1; sustainability targets |

Occupational safety; VOC limits; wastewater discharge rules |

OEM engine tests; CO2 targets; EELQMS/API/ACEA frameworks |

OECD 301; eco-labeling; public procurement |

| High (EU/UK); Moderate–High (US); Emerging (APAC) |

High (US VGP-driven); Moderate–High (EU) |

Moderate (EU/US); Emerging (APAC) |

Low–Moderate (global) |

Emerging–Moderate (selected fleets); Low (passenger cars) |

High (EU/Scandinavia); Moderate (US) |

| ISO 15380 compliance; VI ≥ 140; shear stability; anti-wear; water tolerance; corrosion protection |

Biodegradability; low aquatic toxicity; seal compatibility; anti-wear/EP; hydrolytic stability |

High EP/antiwear; micro-pitting resistance; oxidation stability; foam/air release |

Lubricity; EP; stain control; microbial stability; mist/fume control; operator safety |

Oxidation/piston cleanliness; LSPI control; volatility; seal compatibility |

Biodegradability; anti-wear; water wash-off resistance; tack; low-temp pumpability |

6.3. Drivers of Adoption

Environmental and Health Regulations: Bans on non-biodegradable fluids in certain regions.

Corporate Sustainability Goals: OEMs and fleet operators increasingly highlight bio-lubricants in ESG disclosures.

Technological Advances: Nanoparticle additives, hybrid esters, and improved antioxidants have reduced oxidative instability [

52].

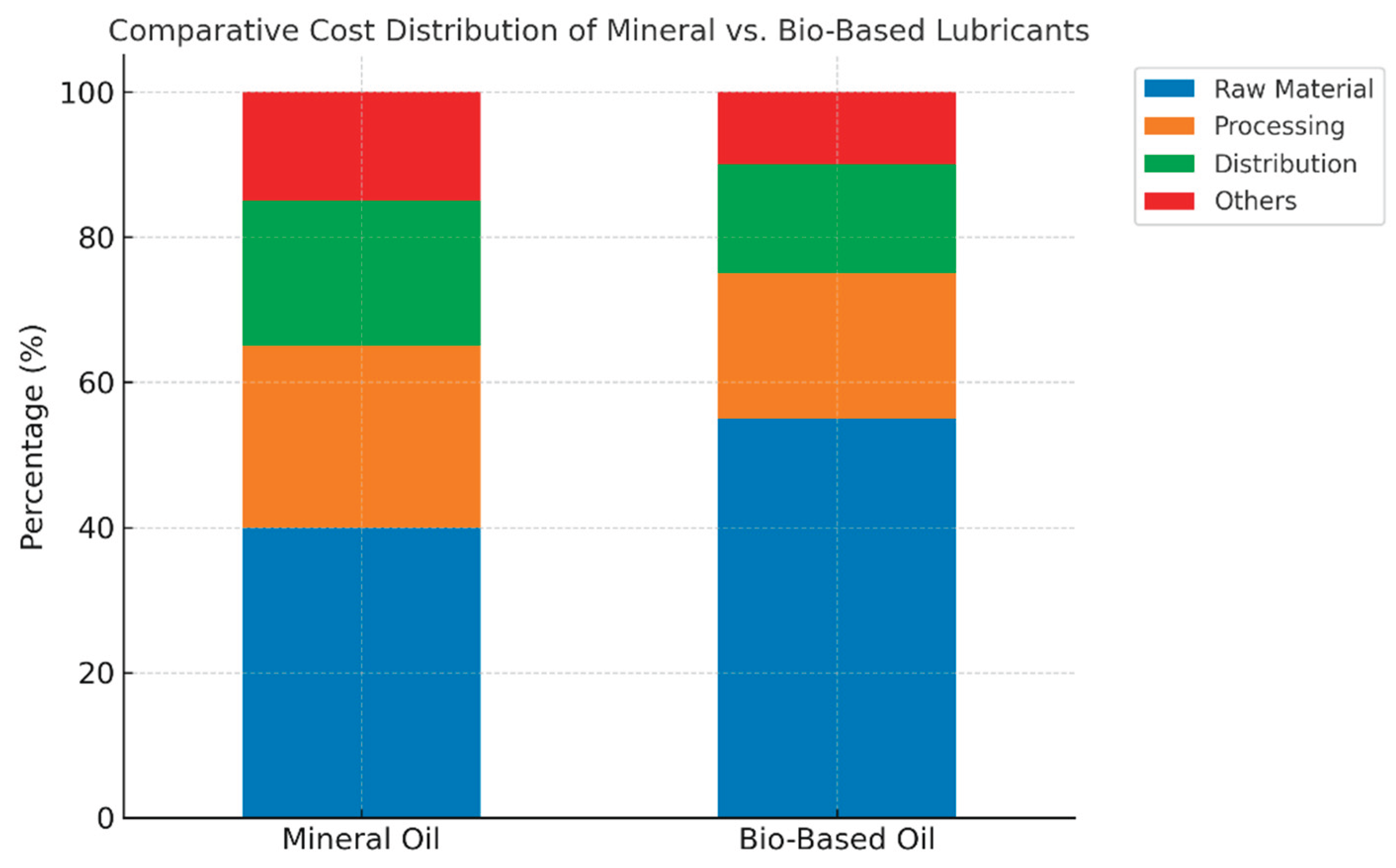

6.4. Barriers to Market Expansion

Cost: Prices remain 20–30% higher than mineral lubricants in bulk applications [

44,

82]. Further details can be viewed in Figure 6.2.

Supply Chain Instability: Feedstock fluctuations (soybean, palm, rapeseed) directly impact bio-lubricant pricing.

Performance Misconceptions: End-users perceive bio-lubricants as “green but inferior,” though modern formulations rival synthetic oils in tribological tests [

19].

Figure 6.2.

Comparative cost distribution of mineral vs. bio-based lubricants across key markets.

Figure 6.2.

Comparative cost distribution of mineral vs. bio-based lubricants across key markets.

6.5. Case Studies and Adoption Success

Deutsche Bahn (Germany): Transitioned to ester-based hydraulic oils in railway switches, reporting reduced maintenance downtime.

Volvo Construction Equipment: Field trials confirmed longer drain intervals with nanoparticle-enhanced bio-hydraulic oils [

53].

Indian Railways: Pilot adoption of biodegradable greases to reduce environmental footprint in sensitive ecosystems.

6.6. Market Outlook

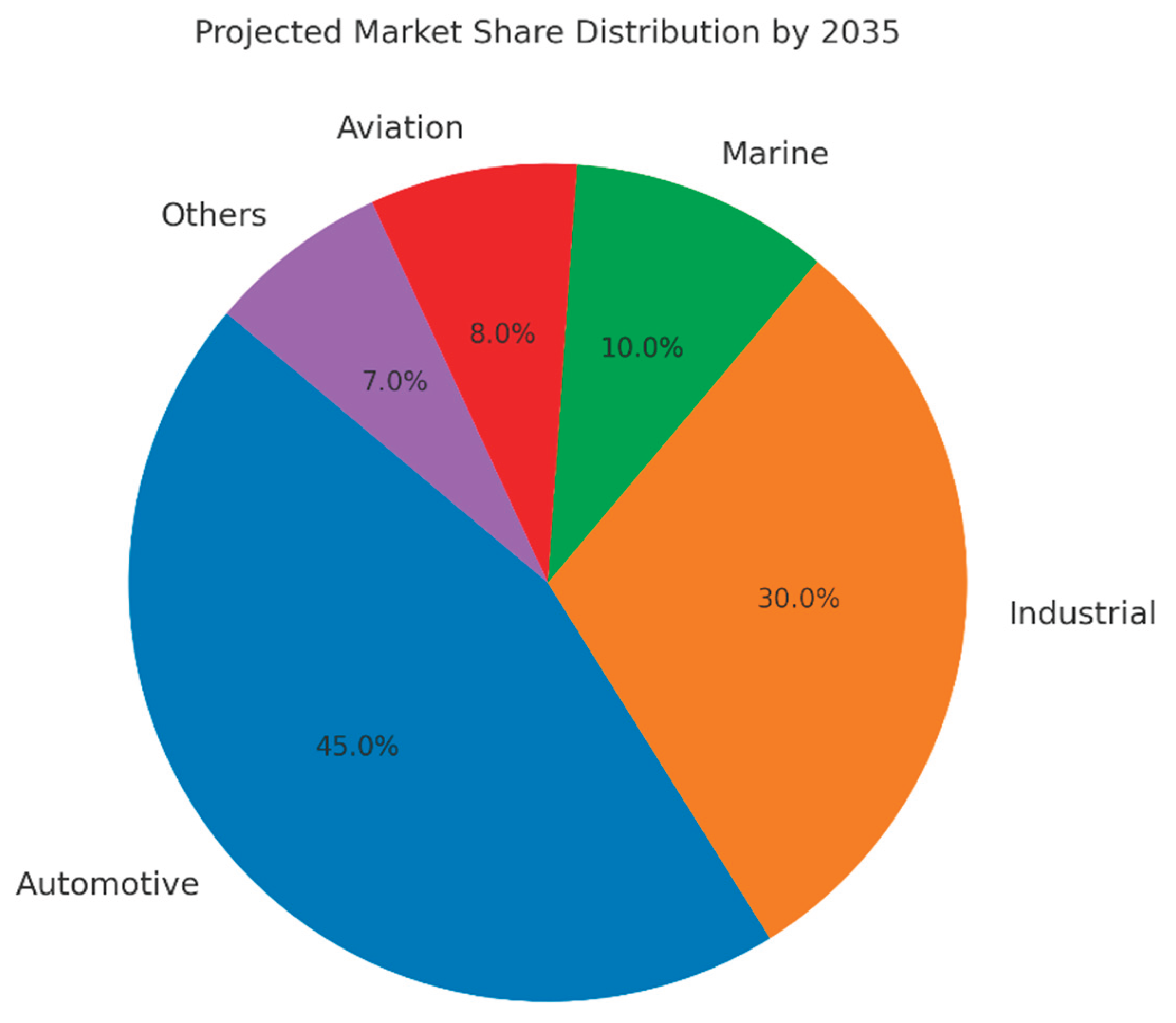

While full industrial substitution is unlikely in the short term, the future points to coexistence with synthetic lubricants. Hybrid formulations (bio + PAO/synthetic esters) are forecast to dominate the mid-term market (Figure 6.3). Moreover, carbon credit incentives and eco-labeling certification are expected to create fresh demand avenues [

54].

Figure 6.3.

Projected market share distribution of mineral, synthetic, and bio-based lubricants by 2035.

Figure 6.3.

Projected market share distribution of mineral, synthetic, and bio-based lubricants by 2035.

7. Sustainability and Environmental Performance of Bio-Based Lubricants

The transition toward sustainable lubrication systems is driven by increasingly stringent environmental regulations, global climate goals, and industrial demand for resource efficiency. Bio-based lubricants, derived from renewable feedstocks, demonstrate inherent advantages in biodegradability, low toxicity, and reduced carbon footprint compared to mineral-oil-based formulations [

18,

55]. Their performance, however, depends on a combination of chemical design, additive selection, and life-cycle impacts that must be systematically assessed.

7.1. Biodegradability and Eco-Toxicity

Biodegradability remains the most critical sustainability indicator for bio-lubricants. OECD guidelines (e.g., 301B and 301F) are commonly applied, setting thresholds of ≥60% degradation within 28 days for classification as readily biodegradable. Comparative standards are summarized in Table 7.1 shows comparative biodegradability standards for lubricants (OECD 301B vs. OECD 301F) and their threshold values for classification, highlighting differences in methodologies such as dissolved organic carbon (DOC) removal and CO₂ evolution [

56].

Table 7.1.

Comparative biodegradability standards for lubricants (OECD 301B vs. OECD 301F).

Table 7.1.

Comparative biodegradability standards for lubricants (OECD 301B vs. OECD 301F).

| Test Standard |

Principle |

Test Duration (Days) |

Pass Criteria |

Typical Bio-Based Lubricant Result |

Typical Mineral Oil Result |

| OECD 301B (CO₂ Evolution Test) |

Measures CO₂ evolution during biodegradation |

28 |

≥60% CO₂ evolution (ThCO₂) |

70–95% |

15–25% |

| OECD 301F (Manometric Respirometry Test) |

Monitors oxygen uptake in a closed system |

28 |

≥60% O₂ consumption (ThOD) |

65–90% |

10–20% |

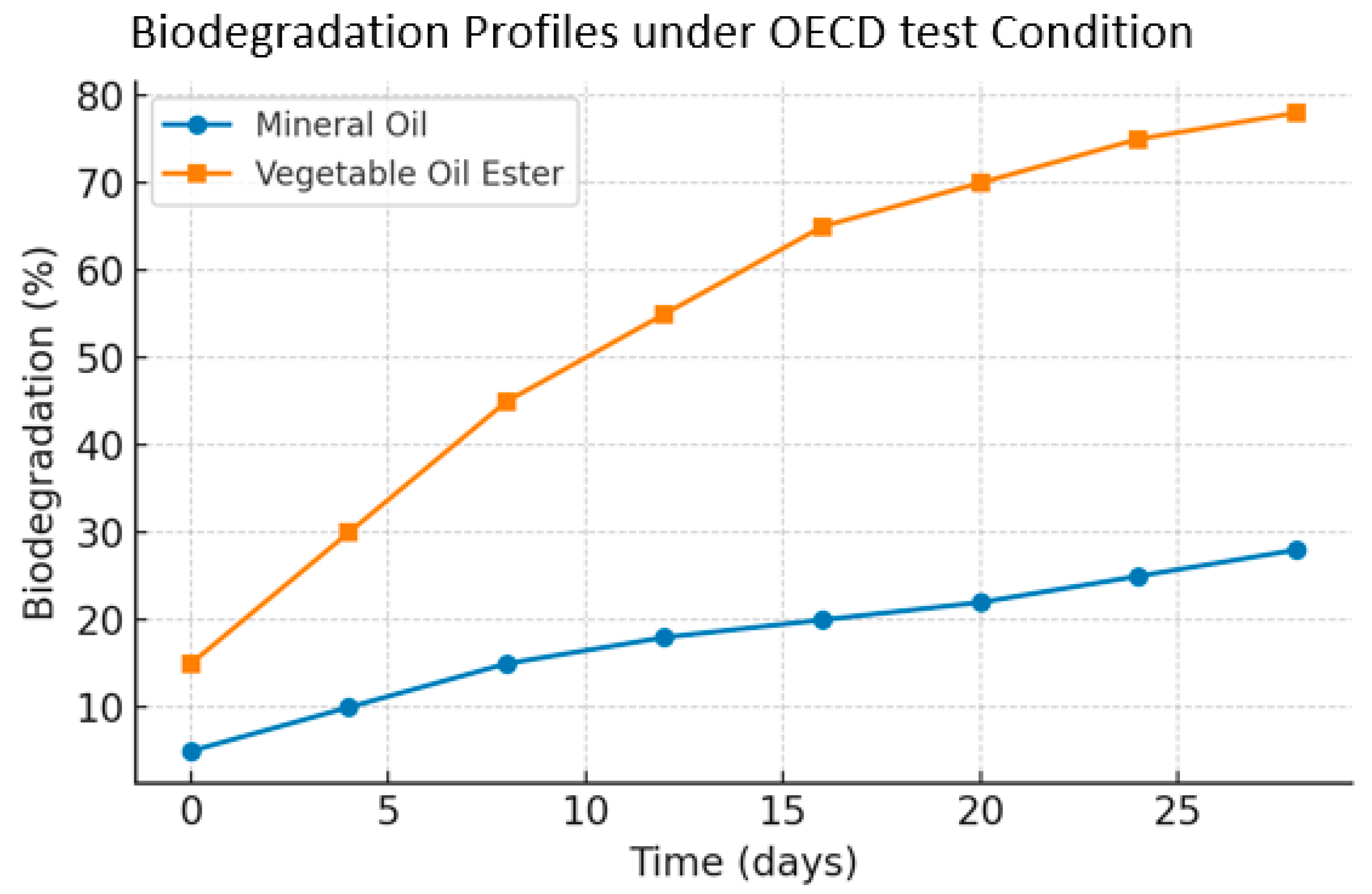

Figure 7.1 illustrates typical biodegradation curves of vegetable oil esters versus mineral oils, confirming superior biodegradability for bio-based alternatives [

57,

58]. Moreover, eco-toxicity studies demonstrate that esterified vegetable oils generally present lower aquatic toxicity than conventional lubricants, making them favorable for applications in marine and agricultural machinery [

1,

59].

Figure 7.1.

Biodegradation profiles of vegetable oil esters compared to conventional mineral oils under OECD test conditions (28 days).

Figure 7.1.

Biodegradation profiles of vegetable oil esters compared to conventional mineral oils under OECD test conditions (28 days).

7.2. Energy Efficiency and Friction Reduction

The tribological efficiency of lubricants significantly influences system-wide energy use. As shown in Table 7.2 (Average friction coefficients of mineral oils vs. selected bio-based lubricants in standardized tribological tests.), bio-based lubricants exhibit lower friction coefficients compared to mineral oils, contributing to relative energy savings of 15–25% in controlled test environments [

60].

Table 7.2.

Average friction coefficients of mineral oils vs. selected bio-based lubricants in standardized tribological tests.

Table 7.2.

Average friction coefficients of mineral oils vs. selected bio-based lubricants in standardized tribological tests.

| Lubricant Type |

Test Conditions |

Average Friction Coefficient (µ) |

Lubricant Type |

Test Conditions |

| Mineral Oil (Group I) |

Steel-on-steel, 40 °C, ASTM D4172 |

0.13 |

Mineral Oil (Group I) |

Steel-on-steel, 40 °C, ASTM D4172 |

| Mineral Oil (Group II/III) |

Steel-on-steel, 40 °C, ASTM D4172 |

0.11 |

Mineral Oil (Group II/III) |

Steel-on-steel, 40 °C, ASTM D4172 |

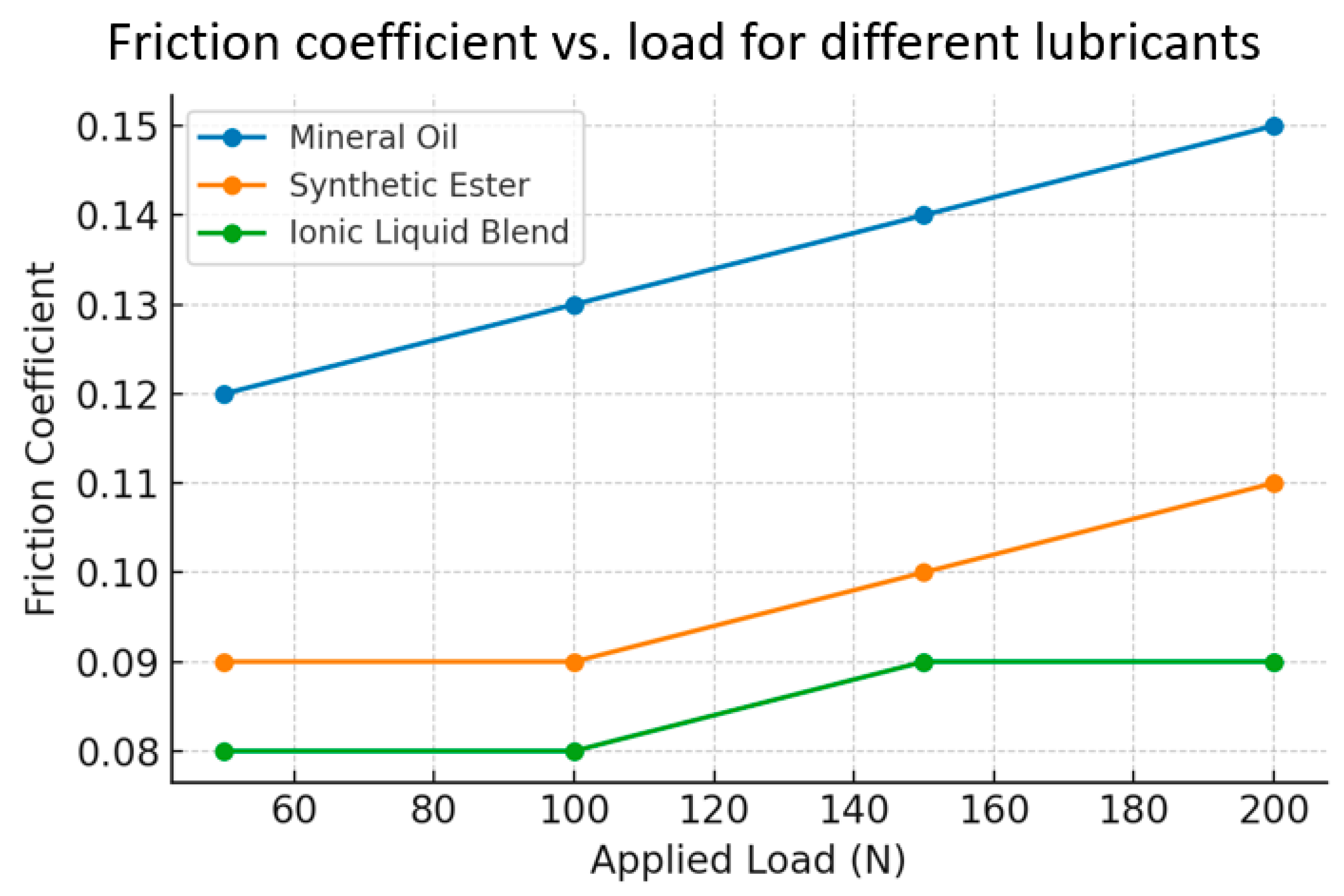

Figure 7.2 compares friction coefficients across lubricant categories, underlining the superior energy efficiency of ionic liquid blends and synthetic esters [

22,

61,

84]. These improvements not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions but also extend equipment life, strengthening the sustainability case for bio-based alternatives.

Figure 7.2.

Friction coefficient comparison of mineral oils, synthetic esters, and ionic liquid blends across varying loads.

Figure 7.2.

Friction coefficient comparison of mineral oils, synthetic esters, and ionic liquid blends across varying loads.

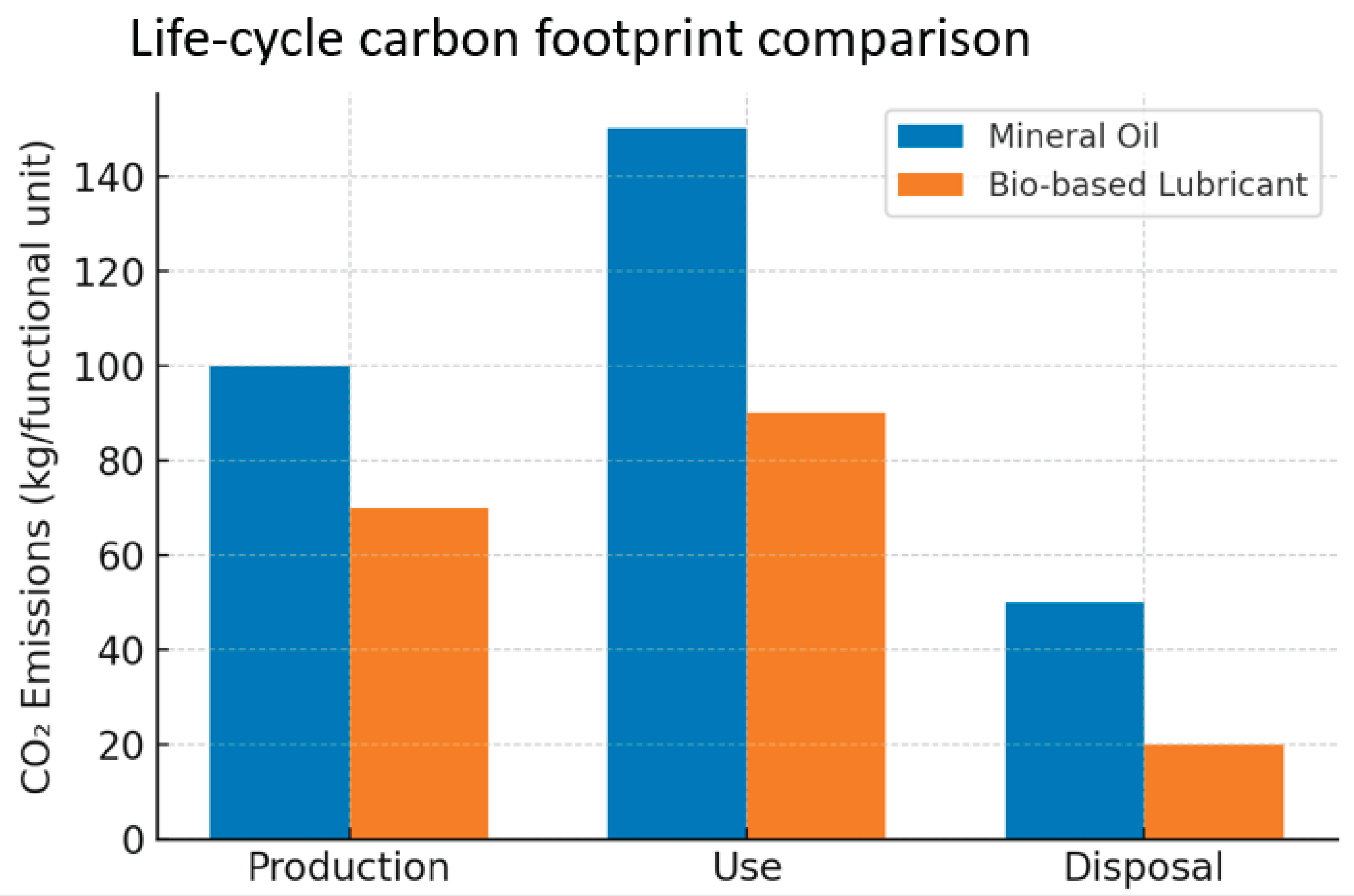

7.3. Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Carbon Footprint

A comprehensive sustainability assessment requires life-cycle analysis, encompassing feedstock cultivation, processing, use-phase, and end-of-life disposal. Figure 7.3 (Life-cycle carbon footprint of mineral oils vs. bio-based lubricants, showing relative reductions in CO₂ emissions across production, use, and disposal phases.) summarizes comparative LCA findings for mineral oils and bio-lubricants, showing reductions in carbon emissions ranging from 30–60% when bio-based systems are adopted [

2,

10,

62].

Figure 7.3.

Life-cycle carbon footprint of mineral oils vs. bio-based lubricants, showing relative reductions in CO₂ emissions across production, use, and disposal phases.

Figure 7.3.

Life-cycle carbon footprint of mineral oils vs. bio-based lubricants, showing relative reductions in CO₂ emissions across production, use, and disposal phases.

Notably, LCA results are sensitive to agricultural practices: intensive pesticide or fertilizer use in oilseed production may offset environmental benefits. Recent studies recommend integrating circular economy strategies, such as recycling used cooking oils and valorizing agro-residues, to further enhance the carbon savings potential [

63,

64].

7.4. Policy and Regulatory Drivers

Sustainability adoption is accelerated by global regulations. The European Union’s Ecolabel program and U.S. EPA Vessel General Permit (VGP) mandate the use of environmentally acceptable lubricants (EALs) in marine and offshore applications [

65]. Such policies create market incentives, pushing industries toward bio-based alternatives. However, harmonization of global sustainability standards remains a challenge, necessitating coordinated international policy frameworks [

66].

8. Future Perspectives, Policy Implications, and Emerging Technologies

The The trajectory of bio-based lubricants is strongly shaped by both technological innovation and evolving regulatory landscapes. While advances in oleochemistry, tribological testing, and additive technologies have positioned bio-lubricants as sustainable alternatives, several systemic barriers remain to be addressed in the coming decade.

8.1. Policy and Standardization Outlook

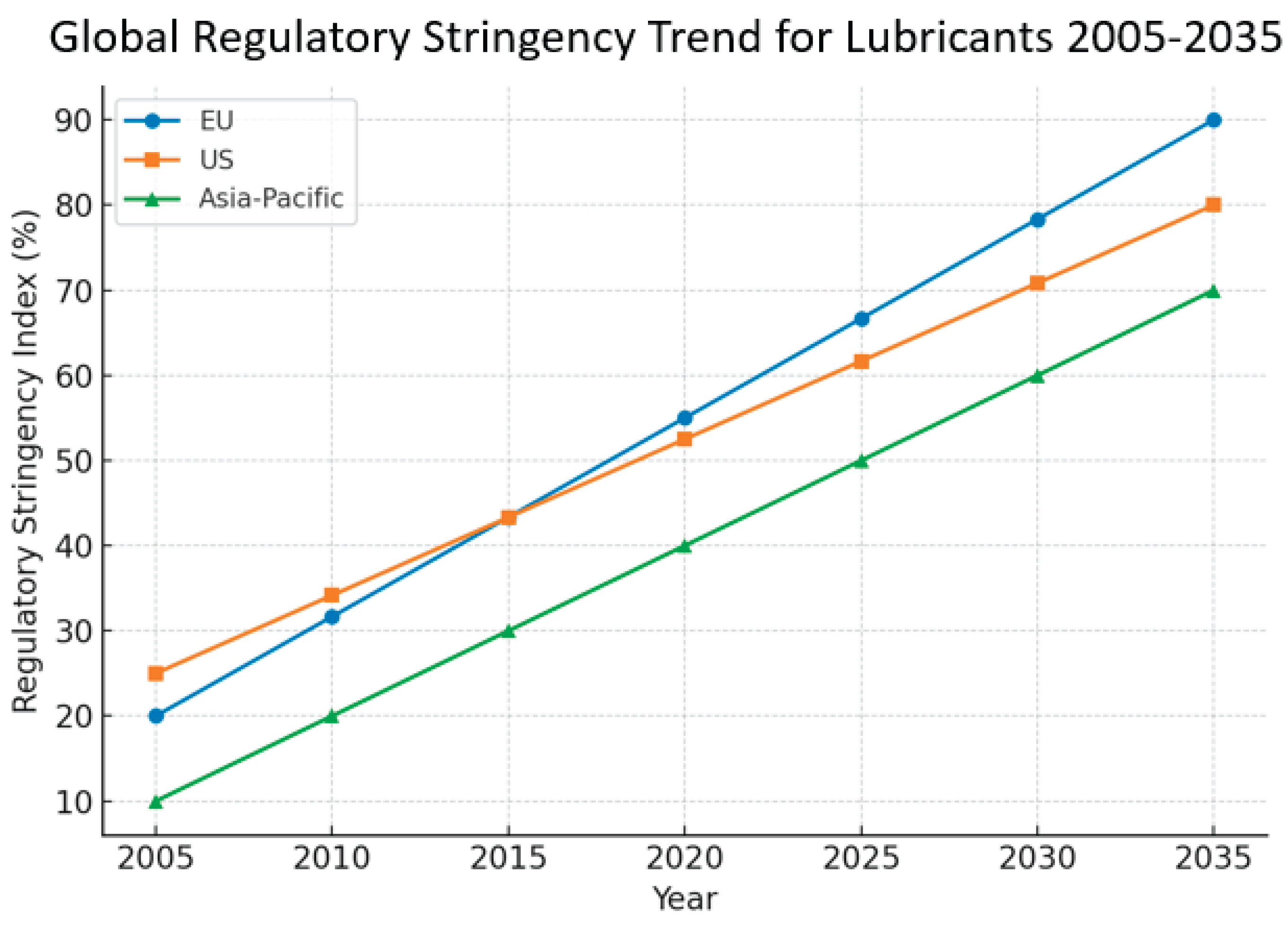

Global adoption of bio-based lubricants depends heavily on the establishment of internationally harmonized standards for biodegradability, toxicity testing, and carbon footprint reporting [

53]. Regulatory bodies such as the EU (REACH) and U.S. EPA are moving toward stricter limits on polyaromatic hydrocarbons and sulfur in lubricants, indirectly favoring renewable formulations [

67]. However, a lack of standardized test protocols across regions often impedes scalability and market competitiveness [

50]. The introduction of ISO standards for eco-lubricants and incentives such as carbon credits are expected to accelerate adoption [

68] (Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1.

Global regulatory stringency trend for lubricants (2005–2035), highlighting policy push toward bio-based formulations.

Figure 8.1.

Global regulatory stringency trend for lubricants (2005–2035), highlighting policy push toward bio-based formulations.

8.2. Emerging Technologies in Bio-Lubricant Development

Recent years have witnessed the integration of nanotechnology, ionic liquids, and enzyme-catalyzed esterification to tailor lubricant performance [

69]. Multi-functional nanoparticle hybrids (e.g., MoS₂ + graphene oxide) are particularly promising for reducing both friction and wear while maintaining biodegradability [

70]. Parallel advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning have enabled predictive formulation design, reducing trial-and-error cycles and improving resource efficiency [

71]. Table 8.1 shows mapping of research challenges, technological opportunities, and policy levers in bio-lubricants.

Table 8.1.

Mapping of Research Challenges, Technological Opportunities, and Policy Levers in Bio-Lubricants.

Table 8.1.

Mapping of Research Challenges, Technological Opportunities, and Policy Levers in Bio-Lubricants.

| Challenge |

Technology Response |

Policy Lever |

| Poor oxidative stability |

Enzyme-catalyzed esterification |

Incentives for bio-refineries |

| High production cost |

AI-driven process optimization |

Carbon credits, subsidies |

| Cold-flow limitations |

Hybrid nanoparticle additives |

Regional cold-weather standards |

| Lack of global test standards |

ISO biodegradability protocols |

WTO harmonization policies |

8.3. Future Market and Environmental Impacts

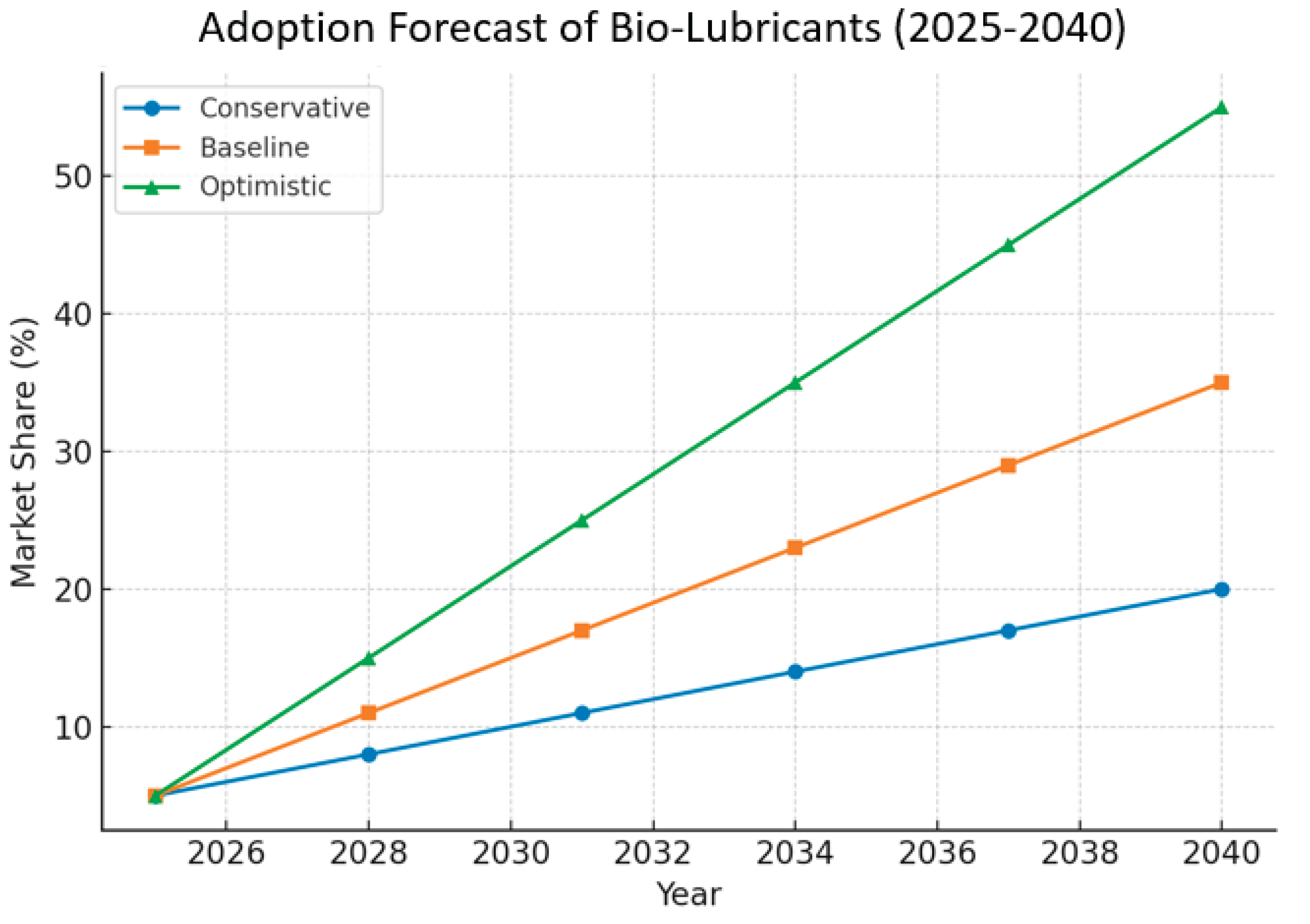

Market adoption of bio-lubricants is projected to grow at a CAGR of 6–8% under current policies [

72,

85]. In optimistic policy environments, this could exceed 12%, particularly if carbon taxation becomes globally adopted [

71]. Figure 8.2. illustrates the adoption forecast of bio-lubricants under three scenarios: Conservative, Baseline, Optimistic (2025–2040).

Figure 8.2.

Adoption forecast of bio-lubricants under three scenarios: Conservative, Baseline, Optimistic (2025–2040).

Figure 8.2.

Adoption forecast of bio-lubricants under three scenarios: Conservative, Baseline, Optimistic (2025–2040).

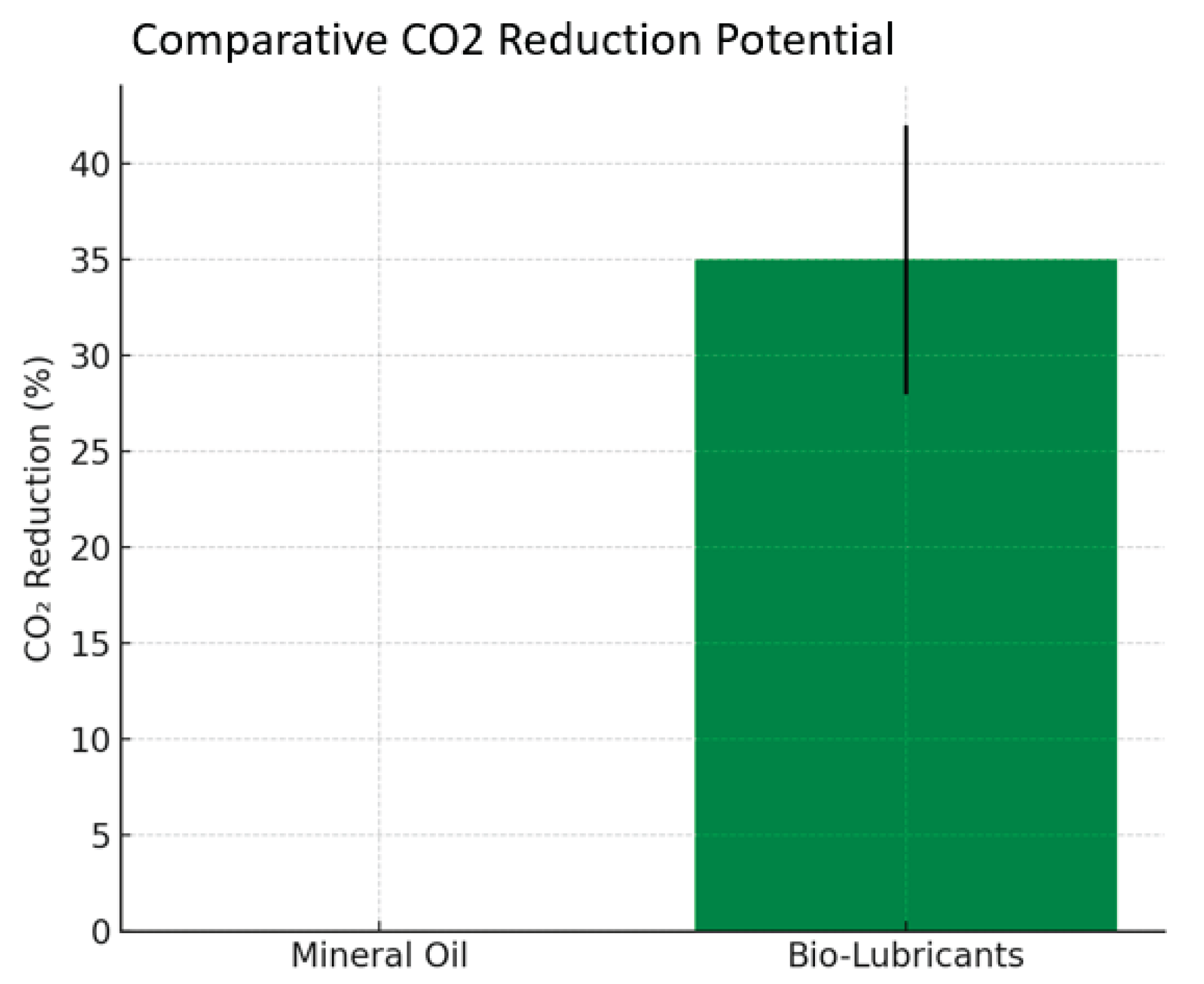

Life cycle assessment studies further indicate that bio-lubricants can reduce net CO₂ emissions by 25–40% compared to mineral oil-based counterparts, with variability depending on feedstock and process efficiency [

53]. Figure 8.3 shows comparative CO₂ reduction potential of mineral vs. bio-lubricants, with error bars reflecting LCA uncertainty ranges (±10–15%).

Figure 8.3.

Comparative CO₂ reduction potential of mineral vs. bio-lubricants, with error bars reflecting LCA uncertainty ranges (±10–15%).

Figure 8.3.

Comparative CO₂ reduction potential of mineral vs. bio-lubricants, with error bars reflecting LCA uncertainty ranges (±10–15%).

8.4. Concluding Perspectives

Future success of bio-based lubricants will depend on bridging the technology-policy-market nexus. Advances in catalysis, hybrid additive systems, and digital formulation tools must be matched with robust policy frameworks and industry-wide collaboration. Establishing eco-label certifications, providing economic incentives, and expanding global R&D networks are critical steps to ensure that bio-lubricants not only remain competitive but also central to sustainable tribology.

9. Future Perspectives and Conclusion

The transition from mineral-oil-based lubricants to bio-based alternatives is no longer a niche effort but a mainstream industrial and research priority. Although significant strides have been made in improving oxidative stability, cold flow behavior, and tribological performance of bio-lubricants, scalability and global adoption remain key challenges. Recent studies emphasize the need for multi-functional additive packages that combine nanoparticles, ionic liquids, and hybrid esters for optimized performance in automotive, aerospace, and marine sectors [

11,

50].

One critical future direction is the integration of digital tools—including AI-driven molecular design and machine-learning-enabled tribology simulations—which allow predictive performance mapping of bio-based oils under diverse operating conditions [

73]. These approaches accelerate the discovery of novel formulations while reducing experimental costs.

The sustainability dimension continues to shape the future landscape. Research increasingly highlights the importance of life-cycle assessments (LCAs) to evaluate the environmental benefits of bio-lubricants over conventional oils [

74,

75]. LCAs suggest that although feedstock cultivation and chemical modification consume resources, the overall carbon footprint reduction and biodegradability advantages outweigh these concerns. Furthermore, linking bio-lubricants with circular economy frameworks—such as waste-oil valorization and closed-loop recycling—will strengthen their role in sustainable tribology [

76].

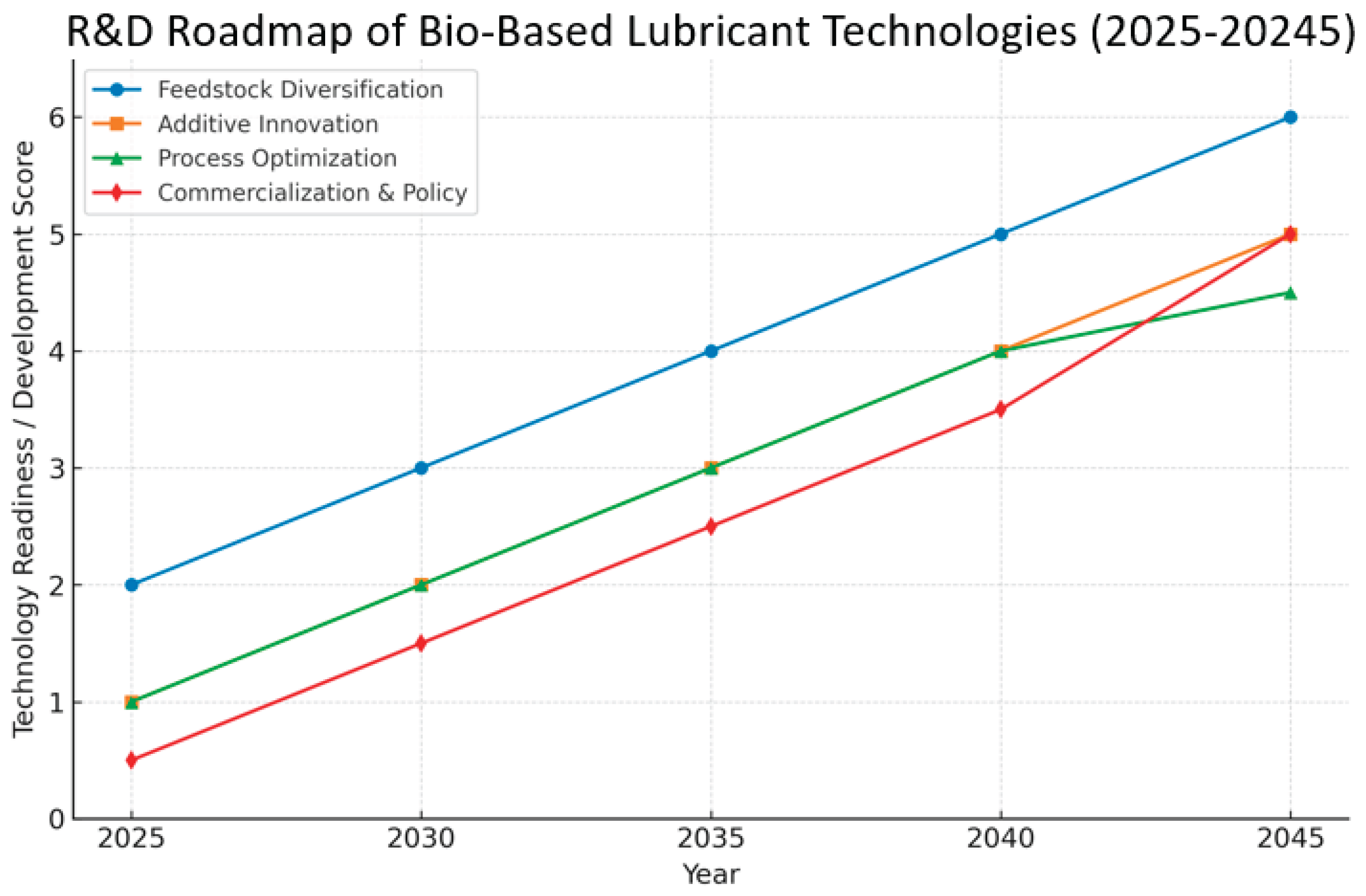

9.1. Roadmap for Technological Advancement

Figure 9.1 illustrates a long-term R&D roadmap outlining near-term (2025–2030), mid-term (2030–2035), and long-term (2035–2045) priorities. These include improving oxidative stability and tribological reliability in the short term, large-scale industrial demonstrations and hybrid additive strategies in the medium term, and full integration into Industry 5.0 smart manufacturing by the 2040s [

13].

Figure 9.1.

R&D Roadmap of Bio-Based Lubricant Technologies (2025–2045).

Figure 9.1.

R&D Roadmap of Bio-Based Lubricant Technologies (2025–2045).

9.2. Adoption Potential Across Sectors

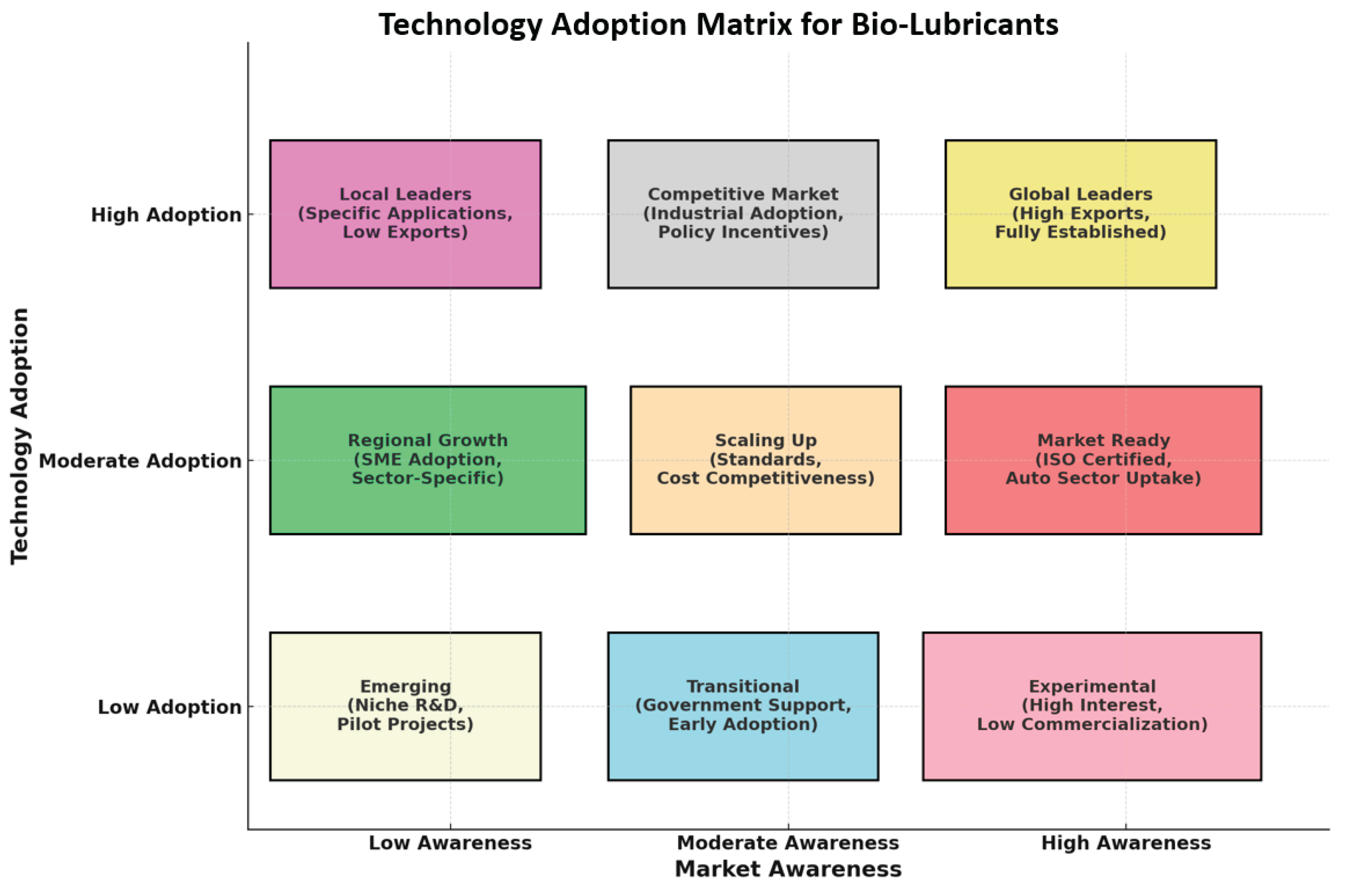

The adoption of bio-lubricants varies across industries. Automotive and marine applications show the fastest growth due to strict emissions regulations, whereas aerospace and heavy machinery lag due to reliability concerns [

77]. Figure 9.2 provides a technology adoption matrix, mapping readiness levels across multiple sectors.

Figure 9.2.

Technology Adoption Matrix for Bio-Lubricants.

Figure 9.2.

Technology Adoption Matrix for Bio-Lubricants.

9.3. Opportunities and Challenges

Key opportunities include reduced carbon emissions, biodegradability, and compatibility with renewable energy systems. On the other hand, cost competitiveness, feedstock supply stability, and long-term durability testing remain major challenges [

12,

78].

9.4. Conclusion

This review consolidates the advances, challenges, and future pathways for bio-based lubricants. It highlights the growing body of research focused on novel additives, nanotechnology, and process optimization. At the same time, it underscores the necessity of system-level thinking, where policy, industry, and academia collaborate for sustainable innovation.

In conclusion, the next decade will define whether bio-based lubricants transition from promising alternatives to mainstream global lubricants. The integration of high-performance additives, AI-driven design tools, and circular economy strategies will be pivotal in this transformation. If these pathways align, bio-lubricants can significantly reduce dependence on fossil-based oils, lower carbon emissions, and redefine the future of sustainable tribology [

79,

80].

Author Contributions

J.P.: Formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation. K.C.: Formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation. N.P.: Resources, writing—review and editing, data curation. S.R: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mang, T.; Dresel, W. Lubricants and Lubrication; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bart, J. C. J.; Gucciardi, E.; Cavallaro, S. Biolubricants: Science and Technology; Woodhead Publishing:

Cambridge, UK, 2013.

- Holmberg, K.; Erdemir, A. Influence of tribology on global energy consumption, costs and emissions. Friction 2017, 5, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimon, J.; Salih, N.; Yousif, E. Biolubricants: Raw materials, chemical modifications and environmental benefits. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2010, 112, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingole, P. G. ; Sinha, S.; Mahalle, A. M. Biodegradable lubricants from renewable sources: Current status and future prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112325. [Google Scholar]

- Campanella, A.; Rustoy, E.; Baldessari, A.; Baltanás, M. A. Lubricants from chemically modified vegetable oils. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Adhvaryu, A.; Erhan, S. Z. Epoxidized soybean oil as a potential source of high-temperature lubricants. Ind. Crops Prod. 2002, 15, 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Siniawski, M.; Saniei, N.; Batchelor, J. Tribological properties of biolubricants for industrial applications. Lubricants 2017, 5, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Soodoo, N.; Bouzidi, L.; Narine, S. S. Fundamental structure–function relationships in vegetable-oil-based lubricants: A critical review. Lubricants 2023, 11, 284. [Google Scholar]

- Raghuvanshi, N.S.; Johari, A.; Saxena, M.; Gupta, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, A.G. Eco-friendly lubricants. In Performance Characterization of Lubricants, 1st ed.; CRC Press: 2024; Chapter 4; 27 pp.

- Sharma, V.K.; Singh, A.K. Recent advances in tribological applications of bio-based oils. Lubricants 2022, 10, 121. [Google Scholar]

- González, R.; Battez, A.H.; Viesca, J.L.; Hadfield, M. Effectiveness of nano-additives in vegetable oil-based lubricants: A review. Lubricants 2019, 7, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, Q. Nanoparticle-based additives for enhanced tribological properties of biolubricants. Lubricants 2021, 9, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, J.; Luo, H.; Chi, M.; Ma, C. Ionic liquids as novel lubricants and additives: A review. Lubricants 2020, 8, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y. Enzymatic modification of vegetable oils for improved lubricant performance. Lubricants 2021, 9, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, F. Hybrid ester-based lubricants: Tribological behavior and thermal stability. Lubricants 2022, 10, 205. [Google Scholar]

- Grand View Research. Bio-Lubricants Market Size Report, 2023–2030; Grand View Research: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Market Watch. Global Bio-Lubricants Market Outlook 2024; Market Watch: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Chauhan, P.S. Market trends and adoption of bio-based lubricants: A critical review. Lubricants 2023, 11, 221. [Google Scholar]

- Bakunin, V.N.; Suslov, A.Y.; Kuzmina, G.N.; Parenago, O.P. Synthesis and application of nanoadditives for lubricants. Lubricants 2020, 8, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Syahir, A.Z.; Zulkifli, N.W.M.; Masjuki, H.H.; Kalam, M.A.; Yusoff, M.F.M.; Gulzar, M. A review on bio-based lubricants and their applications. Lubricants 2017, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhan, S.Z.; Asadauskas, S. Lubricant basestocks from vegetable oils. Ind. Crops Prod. 2000, 11, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.Q.A. A Comprehensive Review of Lubricant Chemistry, Technology, Selection, and Design; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Quinchia, L.A.; Delgado, M.A.; Valencia, C.; Franco, J.M.; Gallegos, C. Viscosity modification of different vegetable oils with EVA copolymer for lubricant applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2009, 32, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, H. Waste cooking oil-derived esters as sustainable lubricants: Properties and performance evaluation. Lubricants 2022, 10, 241. [Google Scholar]

- A review on the production and characterization methods of bio-based lubricants” by Prateek Negi, Yashvir Singh, and Kritika Tiwari; published in Materials Today: Proceedings 46 (2021) 10503–10506.

- Campos Flexa Ribeiro Filho, P.R.; Rocha do Nascimento, M.; Otaviano da Silva, S.S.; Tavares de Luna, F.M.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Loureiro Cavalcante, C., Jr. Synthesis and frictional characteristics of bio-based lubricants obtained from fatty acids of castor oil. Lubricants 2023, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battez, A.H.; González, R.; Viesca, J.L.; Hadfield, M.; Fernández-González, A.; García-Rincón, J.; Reddyhoff, T.; Spikes, H.A. Enhanced wear resistance in vegetable oils with nano-additives. Lubricants 2020, 8, 99. [Google Scholar]

- González, R.; Battez, A.H.; Viesca, J.L.; Hadfield, M. Tribological behaviour of biolubricants with nanoparticle additives. Wear 2010, 268, 325–328. [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq, I.O.; et al. Enhanced performance of bio-lubricant properties with nano-additives for sustainable lubrication. Industrial Lubrication and Tribology 2022, 74(9), 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Li, S. A review of recent developments of friction modifiers for liquid lubricants (2007–present). Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2014, 18, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tang, Z.; Guo, S.; Wang, Q. The Application of Ionic Liquids in the Lubrication Field: Past, Present, and Future. Lubricants 2024, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xie, C.; Zhang, Q. Cold-flow and oxidative stability improvement of vegetable-oil-based lubricants: A review. Lubricants 2021, 9, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjurjo, C.; Rodríguez-Yáñez, Y.; Hernández Battez, A.; González, R. Influence of molecular structure on the physicochemical and tribological properties of biobased lubricants. Lubricants 2023, 11, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Zhang, G.; Li, W. Tribological evaluation of chemically modified rapeseed oil as lubricant. Tribol. Int. 2017, 110, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jabal, A.A.; Salimon, J.; Yousif, E. Biodegradability and tribological characteristics of chemically modified vegetable oils. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2016, 203, 423–431. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Kundu, P.; Singh, Y. Tribological aspects of nano-additivized bio-based lubricants: Recent developments. Lubricants 2022, 10, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Battez, A.; González, R.; Viesca, J.L.; Hadfield, M.; Fernández-González, A.; García-Rincón, J.; Reddyhoff, T.; Spikes, H.A. Environmentally friendly tribological testing of lubricants with ionic liquids. Lubricants 2019, 7, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y. Tribological properties of bio-lubricants with graphene oxide nanoparticles. Lubricants 2020, 8, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Chen, H.; Yang, S. Epoxidized vegetable oils as base stocks for tribological applications. Lubricants 2019, 7, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Campanella, V.; Baldessari, A.; Rustoy, E. Effect of fatty acid unsaturation on wear and friction of vegetable oils. Tribol. Lett. 2018, 66, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, V.K.; Singh, A.K.; Verma, P. Sustainable aspects of bio-lubricants: A critical review. Lubricants 2023, 11, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Ingole, P.G.; Mahalle, A.M.; Sinha, S. Life cycle assessment of vegetable oil-based lubricants: Methodological approaches and future outlook. Lubricants 2022, 10, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Salimon, J.; Salih, N.; Yousif, E. Biodegradability and environmental benefits of modified plant oils as lubricants. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2010, 112, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.; Qu, J.; Luo, H. Green tribology and eco-design of lubricants: Trends and perspectives. Lubricants 2021, 9, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, M.J.; Rahman, M. Carbon footprint reduction potential of vegetable oil-based lubricants. Renew. Energy 2021, 170, 777–789. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz, A.; Shah, R.; Woydt, M.; Aragon, N.; Murrenhoff, H. The twelve principles of green tribology. Lubricants 2022, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. REACH Regulation Overview; EU Policy Report, 2022.

- Sharma, V.K.; Singh, A.K. Policy challenges in adoption of bio-based lubricants. Lubricants 2023, 11, 245. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. ISO 15380: Lubricants—Environmentally Acceptable Lubricants; International Standards Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Huang, Q. Hybrid nanoparticles for enhanced tribological and environmental performance of bio-lubricants. Lubricants 2022, 10, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Y.; Sharma, A. Artificial intelligence in lubricant design: Emerging opportunities. Lubricants 2022, 10, 190. [Google Scholar]

- Narayana Sarma, R.; Vinu, R. Current status and future prospects of biolubricants: Properties and applications. Lubricants 2022, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Pandey, P.M.; Singh, V.K. Ionic liquid-enhanced bio-lubricants for improved thermal stability and wear resistance. Lubricants 2023, 11, 278. [Google Scholar]

- Goud, V.V.; Patwardhan, A.V.; Dinda, S.; Pradhan, N.C. Epoxidation of karanja (Pongamia glabra) oil with hydrogen peroxide. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2007, 84, 887–894. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.V.; Somidi, A.K.R.; Dalai, A.K. Preparation and properties of biolubricants from canola oil by transesterification and epoxidation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 94, 490–501. [Google Scholar]

- Knothe, G.; Dunn, R.O. A comprehensive evaluation of the melting points of fatty acids and esters determined by differential scanning calorimetry. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2009, 86, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, D. Oxidative stability of biolubricants prepared from epoxidized soybean oil and 2-ethylhexanol. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 108, 223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Gunstone, F.D. Vegetable Oils in Food Technology: Composition, Properties and Uses; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Salih, N.; Salimon, J.; Yousif, E. Chemically modified biolubricants: Evaluation of epoxidized and esterified oleochemicals. J. Oleo Sci. 2011, 60, 613–618. [Google Scholar]

- Biresaw, G.; Adhvaryu, A.; Erhan, S.Z. Friction and wear properties of soybean oil estolides. Lubr. Sci. 2003, 15, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Quinchia, L.A.; Delgado, M.A.; Reddyhoff, T.; Gallegos, C.; Spikes, H.A. Tribological studies of potential vegetable oil-based lubricants modified with antioxidants and epoxidized oils. Tribol. Int. 2014, 69, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, A.; Tsoutsos, D.; Zafeiratos, S.; Kapsalis, V.; Nikolaou, A. Synthesis and evaluation of bio-lubricants from renewable raw materials: Vegetable and used frying oils. Lubricants 2024, 12, 446. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, Y. Effect of esterification route on physicochemical and lubrication properties of castor oil-based lubricants. Energies 2019, 12, 3848. [Google Scholar]

- Knothe, G. Dependence of biodiesel fuel properties on the structure of fatty acid alkyl esters. Fuel Process. Technol. 2005, 86, 1059–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimon, J.; Abdullah, B.M.; Salih, N. Epoxidized fatty acids and derivatives: A review. Molecules 2010, 15, 7798–7819. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y. Enzymatic synthesis of tailor-made esters for renewable lubricants. Lubricants 2021, 9, 243. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, J.; Franco, J.M.; Delgado, M.A. Adoption pathways of eco-friendly lubricants in Europe and Asia. Lubricants 2021, 9, 188. [Google Scholar]

- Kalin, M.; Vižintin, J.; Remškar, M. Performance of graphene oxide additives in biodegradable lubricants. Lubricants 2022, 10, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, A.E.; Bartolomé, A.; Sánchez, M.C. Artificial intelligence for lubricant formulation: Opportunities and challenges. Lubricants 2023, 11, 352. [Google Scholar]

- Righi, M.; Carbone, G.; D’Acunto, M. Digital twin-based predictive models for lubricant performance. Lubricants 2022, 10, 255. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Singh, H.; Sinha, S.; Mahato, A.; Ghosh, A. Choline-based ionic liquids as sustainable additives in bio-lubricants. Lubricants 2022, 10, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar, G.; Ghosh, P.; Sharma, B.K. Natural antioxidants for stabilization of bio-based lubricants: A critical review. Lubricants 2020, 8, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, T.; Costa, R.; Pinho, S.; Torres, M.; Marques, A. Synergistic effects of phenolic and lignin-based antioxidants in vegetable oil lubricants. Lubricants 2021, 9, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Nagendramma, P.; Kaul, S. Development of eco-friendly lubricants from renewable resources. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, M.; Primerano, P.; D’Agostino, F.; Mollá, S.; Cirillo, S. Improving viscosity stability of bio-lubricants using polymeric additives. Lubricants 2020, 8, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, J.; Luo, H.; Chi, M.; Ma, C. Emerging role of nanoparticles in green tribology. Tribol. Int. 2021, 155, 106762. [Google Scholar]

- Minami, I. Ionic liquids in tribology: A review. Lubricants 2017, 5, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Liang, Y.; Liu, W. Ionic liquid lubricants: Designed chemistry for green tribology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2590–2599. [Google Scholar]

- Habibullah, M.; Masjuki, H.H.; Kalam, M.A.; Arslan, A.; Syahir, A.Z. Synergistic blends of nanoparticles and ionic liquids in bio-lubricants. Lubricants 2020, 8, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A.K.; Borugadda, V.B.; Goud, V.V. In-situ epoxidation of waste cooking oil and its methyl esters for lubricant applications: Characterization and rheology. Lubricants 2021, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, D. Plant-based oils for sustainable lubrication solutions—Review. Lubricants 2024, 12, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, S.; Rosa, P.; Davim, J.P. Conventional and recent advances of vegetable oils as lubricants in manufacturing and tooling applications. Lubricants 2023, 11, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Rodríguez, C.J.; Saldaña-Robles, A.; Peña-Parás, L.; Maldonado-Cortés, D.; Alvarado-Orozco, J.M.; Núñez-Hernández, L.A. Tribological performance of sunflower oil modified with SiO₂ and TiO₂ nanoparticles. Lubricants 2020, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xue, Q.; Xu, X.; Wang, L. Elaboration of ionic liquids on the anti-wear performance of base oil. Lubricants 2022, 10, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Silva, S.D.; García-Morales, M.; Ruffel, C.; Delgado, M.A. Influence of the nanoclay concentration and oil viscosity on the rheological and tribological properties of nanoclay-based ecolubricants. Lubricants 2021, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).