1. Introduction

Lightning is a powerful, stochastic natural-disturbance agent whose high-energy cloud-to-ground discharges inflict both immediate and cascading impacts on forest ecosystems (Veraverbeke et al., 2017). Beyond igniting wildfires, lightning causes mechanical damage to tree tissues and initiates nutrient and carbon pulses through scorching and subsequent decay (Gora et al., 2020). In tropical forests—where lightning frequencies exceed 50 strikes·km⁻²·yr⁻¹—emergent trees, which disproportionately store carbon, suffer elevated strike mortality, instigating canopy gaps that redirect successional pathways and alter biomass turnover (Yanoviak et al., 2020).

Climate warming is projected to amplify lightning activity by 5–12 % per °C of atmospheric heating, thereby increasing ignition probabilities during dry spells and intensifying fire-lightning feedback loops (Romps et al., 2014). Recent model forecasts also suggest that rising convective intensity may expand the geographic range of lightning-ignited fires into previously humid tropical regions (Janssen et al., 2023). In boreal forests, lightning-caused fires now account for approximately 15 % of global fire emissions, with permafrost thaw further magnifying carbon losses (Veraverbeke et al., 2017).

Despite these global insights, lightning remains markedly understudied in India’s forest dynamics. Recent analyses reveal a surge in extreme cloud-to-ground strokes correlating with increased wildfire ignitions across the subcontinent, yet national forest-management and carbon-accounting mechanisms—including REDD+ and blue-carbon protocols—routinely omit lightning-induced biomass losses, leading to systematic underestimation of carbon fluxes (De et al., 2024).

This omission is especially critical in Eastern India’s biodiversity hotspots:

Simlipal Biosphere Reserve, an expanse of moist-deciduous and semi-evergreen forests in Odisha, supporting keystone species such as Shorea robusta and underpinning indigenous livelihoods (Dash & Behera, 2014).

Sundarbans Mangrove Ecoregion, the world’s largest contiguous mangrove tract at the Ganges–Brahmaputra delta, vital for blue-carbon sequestration, coastal protection, and unique faunal assemblages (Gopal & Chauhan, 2006).

Eastern Ghats, a discontinuous chain of dry and moist deciduous forest fragments spanning Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, harboring numerous endemic and threatened taxa under escalating anthropogenic and climatic pressures (Behera et al., 2024).

An integrated ecological synthesis that combines field-based tree-mortality surveys, high-resolution lightning-risk mapping (e.g., WWLLN, Damini), and comprehensive policy analysis is urgently needed. Parameterizing lightning-mortality functions in MRV models and embedding stochastic disturbance pulses into REDD+ and blue-carbon protocols will refine carbon-budget estimates, inform resilient restoration designs, and close a critical policy blind spot in India’s conservation planning.

2. Study Area Description

Eastern India spans a complex matrix of forest ecosystems across Odisha, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Tamil Nadu. The region is governed by a tropical monsoon climate—with the southwest monsoon (June–September) delivering 70–80 % of annual rainfall and the northeast monsoon (October–December) contributing a secondary peak. Annual precipitation ranges from 800 mm in inland, rain-shadow zones to over 2,200 mm along the coast, while mean temperatures fluctuate between 10 °C in hill-tops to highs of 42 °C in plains. Altitudinal gradients—from sea level to over 1,600 m—shape distinct forest types and lightning-vulnerability profiles. Our analysis centers on three representative landscapes:

Similipal Biosphere Reserve- Coordinates: 21.93° N, 86.35° E, Elevation: 200–1,165 m (peak at Dharani Dhar ~1,165 m), Area: ~2,750 km²; Annual rainfall: 1,600–1,800 mm; Temperature: 10–42 °C, Forest types: Tropical moist deciduous (Shorea robusta–Terminalia-dominated), semi-evergreen patches, and montane grasslands above 900 m, Soils: Lateritic red loams with moderate conductivity This reserve’s steep elevational gradient and dense Sal canopy make it a hotspot for lightning strikes on emergent trees and subsequent gap formation.

Sundarbans Mangrove Ecoregion- Coordinates: 21.95° N, 89.18° E, Elevation: 0–6 m above sea level, Area: ~10,000 km² (Indian portion ~4,200 km²); Annual rainfall: 1,800–2,100 mm; Temperature: 22–37 °C, Forest types: True mangroves (Avicennia, Rhizophora, Bruguiera) on saline-peat substrates, Soils: Water-logged peat and alluvium with high electrical conductivity The flat topography, tidal inundation, and saline soils amplify lightning-strike lethality and risk of ignition in this blue-carbon stronghold.

Eastern Ghats- Coordinates: ~11.5°–20° N, 76.5°–86° E, Elevation: 100–1,680 m (highest point Arma Konda at 1,680 m), Area: ~125,000 km²; Annual rainfall: 800–1,500 mm (decreasing inland); Temperature: 12–38 °C, Forest types: Tropical evergreen and semi-evergreen in windward, high-rainfall blocks; moist deciduous (40–75 % canopy) on mid-slopes; dry deciduous and thorn scrub in leeward, low-rainfall zones, Soils: Rocky outcrops interspersed with shallow red loams and gravelly substrata Fragmentation, fire-prone dry deciduous patches, and variable soil conductivity make the Eastern Ghats a critical landscape for assessing lightning–fire interactions under seasonal moisture stress.

3. Regional Impact and the Need for Ecological Recognition

In Simlipal, anecdotal accounts and visible forest-patch degradation suggest lightning may be responsible for recurring mortality of keystone canopy species such as Shorea robusta. This reserve is also the only known habitat of wild melanistic (black) tigers, a rare genetic variant of the Bengal tiger whose population is critically limited and genetically isolated (IUCN – Endangered). Lightning-induced canopy gaps and fire events could fragment tiger corridors, reduce prey density, and exacerbate stress on this already vulnerable population.

In the Sundarbans, mangroves rooted in saltwater-saturated peat present a highly conductive substrate, amplifying strike lethality. Species such as Avicennia marina (IUCN – Least Concern) and Rhizophora mucronata (IUCN – Least Concern) face elevated mortality risk, while peat destabilization threatens the integrity of blue-carbon stores. The region also shelters endangered fauna including the Ganges River Dolphin (Platanista gangetica; IUCN – Endangered), River Terrapin (Batagur baska; IUCN – Critically Endangered), and the mangrove-adapted Royal Bengal Tiger (IUCN – Endangered). Lightning may compound the effects of salinity intrusion and cyclone damage, further shrinking viable habitat.

The Eastern Ghats, fragmented and fire-prone, offer limited moisture buffering, making dry deciduous stands especially vulnerable to ignition. RET species such as Red Sanders (Pterocarpus santalinus; IUCN – Endangered), Syzygium alternifolium (IUCN – Vulnerable), and Cycas beddomei (IUCN – Vulnerable) are confined to microhabitats that may be disproportionately affected by lightning–fire interactions. The region also supports isolated populations of Indian Bison (Bos gaurus; IUCN – Vulnerable), Slender Loris (Loris lydekkerianus; IUCN – Near Threatened), and Hill Mynas (Gracula religiosa; IUCN – Near Threatened), whose habitat resilience may be compromised by repeated abiotic stress.

Despite these acute risks, no ecological studies have yet quantified lightning’s impact on vegetation structure, species mortality, or carbon flux in these regions. Only a handful of meteorological assessments, such as Akhter et al. (2024), have identified these zones as lightning-prone. This review marks a first effort to bridge that gap—by synthesizing global mechanistic insights with regional ecological stakes, and calling for lightning to be recognized as a legitimate disturbance force in India’s conservation and carbon-accounting frameworks.

4. Probability & Risk Mapping

Lightning-risk mapping in Eastern India combines high-resolution lightning data with ecological and edaphic layers to pinpoint hotspots and vulnerable zones. Two primary lightning data sources are utilized: the World Wide Lightning Location Network (WWLLN), a global VLF sensor array that detects cloud-to-ground strokes with approximately 30 % efficiency and produces gridded flash-density maps (Rodger at al. 2005), and the Damini Lightning Alert App, managed by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology and the Ministry of Earth Sciences, which operates through 83 ground-based sensors to deliver sub-kilometer real-time alerts (Press Information Bureau, 2022).

Ecological overlays involve integrating the India State of Forest Report’s forest-type classification, which distinguishes moist deciduous, semi-evergreen, mangrove, and dry deciduous classes at a 1:50,000 scale (Forest Survey of India, 2021). Canopy-height data are derived from NASA’s GEDI L2A LiDAR product, offering 25 m footprint estimates of vertical forest structure to identify emergent trees most susceptible to strikes (Dubayah et al., 2020). Soil-conductivity layers are mapped using the National Bureau of Soil Survey and Land Use Planning’s digital soil series distribution, which categorizes electrical conductivity classes and highlights conductive substrates such as peat-rich mangroves and saline floodplains (National Bureau of Soil Survey and Land Use Planning, 2021).

In a GIS environment, raster datasets of lightning flash density, forest type, canopy height, and soil electrical conductivity are overlaid and processed using kernel-density estimation to generate a continuous strike-risk intensity surface; exposure zones are then defined based on annual strike thresholds, with very high-risk areas characterized by tall-canopy moist and semi-evergreen forests on highly conductive soils experiencing more than five strokes·km⁻²·yr⁻¹, and high-risk areas comprising fragmented dry-deciduous or mangrove stands on moderately conductive substrates with two to five strokes·km⁻²·yr⁻¹. This integrated risk map guides targeted field surveys, informs the strategic placement of lightning arrestors, and enables the incorporation of stochastic lightning-disturbance pulses into regional carbon-accounting and conservation-planning frameworks.

5. Global Comparison: Disturbance Ecology Across Biomes

Lightning is a potent and increasingly consequential disturbance force that shapes forest structure, biomass turnover, and carbon fluxes across diverse global ecosystems. While tropical and boreal systems are best studied, subtropical, temperate, savanna, and montane forests offer equally instructive insights—especially in contexts relevant to India.

5.1. Tropical Forests (Amazon & Congo Basin)

Tropical forests endure some of the highest lightning flash densities globally, exceeding 100 strokes·km⁻²·yr⁻¹ in convective hotspots. In lowland Panama, lightning strikes kill an average of 3.5 trees per event, damage over a dozen nearby individuals, and generate ~300 m² canopy gaps and 7.4 Mg of woody biomass turnover (Gora et al., 2021). Cumulatively, ~200 million trees are lost annually to lightning across Amazonia and the Congo, disproportionately affecting emergent carbon-rich trees (Yanoviak et al., 2020). Lightning is now recognized as a stronger predictor of biomass turnover than temperature or precipitation (Gora et al., 2020), and is expected to intensify by 10–25% per °C of global warming (Romps et al., 2014), undermining tropical forests’ carbon-sink capacity (Veraverbeke et al., 2025).

5.2. Boreal Forests (Canada, Siberia, Alaska)

Though boreal forests exhibit lower flash rates (~0.1–1 strokes·km⁻²·yr⁻¹), lightning is the dominant ignition source for wildfires, responsible for ~15% of global fire emissions (Veraverbeke et al., 2017). These fires release ~306 Tg C per year and combust deep organic horizons, accelerating permafrost thaw (Van Wees et al., 2022). Thaw-induced emissions can add an additional 10–30% carbon release, triggering a self-reinforcing loop: warming → lightning → fire → permafrost degradation → CO₂ and CH₄ release → more warming (Natali et al., 2021; Turetsky et al., 2019).

5.3. Subtropical & Temperate Forests

In subtropical and temperate zones—including Mediterranean pine stands and forests of North America and Asia—lightning ignitions are rising under climatic stress. Janssen et al. (2023) show that lightning is increasingly responsible for extratropical forest fires worldwide, especially under drought conditions. In the southeastern U.S., lightning-driven fires maintain open-canopy longleaf pine ecosystems and promote fire-adapted understory flora (Cochrane, 2009). Episodic fires may lead to significant carbon fluxes, especially in regions with prolonged dry seasons and flammable litter layers.

5.4. Savannas & Grasslands

Savannas in sub-Saharan Africa, northern Australia, and South America depend on lightning-triggered surface fires to regulate tree–grass dynamics. Fires reduce woody cover, promote pyrophytic grasses, and increase habitat heterogeneity (Lehmann et al., 2014; Trollope & Trollope, 2009). While post-fire regrowth often compensates carbon losses, rising lightning frequencies may shift savanna systems toward net emissions under warming scenarios.

5.5. Montane & Alpine Forests

Montane ecosystems—like those in the Himalayas, Andes, and European Alps—face increasing lightning strikes concentrated on ridgelines and exposed slopes. Conedera et al. (2006) documented a rise in high-elevation lightning-induced fires, which are harder to suppress and often smolder underground. These forests offer critical slope stabilization, avalanche buffering, and hydrological services. Lightning-induced degradation poses risks to these ecosystem functions (Moos et al., 2023), especially where regeneration is slow and erosion vulnerability is high.

6. Policy Landscape & Mitigation Strategies

Lightning disturbances are conspicuously absent from India’s forest-management and carbon-accounting policies, despite mounting global evidence of their ecological and climatic importance. Below, we contrast India’s current approach with international best practices, highlighting key scientific studies that India has yet to integrate.

6.1. Policy Gaps: Global Recognition vs. Indian Oversight

Global forests- Brazil’s PRODES satellite-monitoring framework explicitly tracks lightning-induced canopy gaps and tree mortality alongside deforestation alerts (Nepstad et al., 2014). Canada’s Wildfire Management Strategy mandates lightning-ignition attribution in annual fire-emission inventories (Veraverbeke et al., 2017). Australia’s National Bushfire Management Policy integrates lightning-fire risk into prescribed-burn planning and fuel-management maps (Boer et al., 2021).

India’s omissions- National Forest Policy and State Forestry Acts make no mention of lightning as a disturbance agent. Restoration schemes (e.g., Green India Mission, mangrove afforestation) lack protocols for quantifying lightning mortality or ignition risk, despite evidence that lightning drives substantial biomass turnover in tropical systems (Gora et al., 2020).

6.2. MRV: Missing Lightning in Carbon Accounting

-

Global frameworks

REDD⁺ guidance under UNFCCC calls for inclusion of all natural disturbances—including lightning—in MRV (Herold & Skutch, 2009).

The European Union’s LULUCF regulation requires member states to report carbon losses from lightning-induced fires and tree mortality in forestry inventories (European Commission, 2018).

India’s gaps- Current MRV templates for REDD⁺, blue carbon and forest-carbon projects disregard episodic losses from lightning strikes, underestimating emissions by up to 20% in lightning-prone zones (Wamsler et al. 2021). Lack of field-calibrated risk parameters prevents integration of lightning mortality models into national carbon budgets, even though lightning frequency outperforms temperature and precipitation in predicting biomass turnover (Gora et al., 2020).

6.3. Early Warning Systems: Under-Utilized in Forest Management

Global best practice- The U.S. National Lightning Detection Network (NLDN) feeds real-time strike data into fire-danger rating systems, enabling pre-emptive closures of high-risk recreation areas (Cummins et al., 2020). Europe’s EUMETNET Lightning Detection network integrates with the European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS) to forecast lightning-ignited fires (Müller et al. (2020).

Indian status- India operates three lightning detection networks (WWLLN, Earth Networks, NRSC’s LDSN) and issues Damini/IMD alerts, but these are not linked to forest-fire risk models or district-level forest management protocols (NDMA, 2019; NRSC, 2023). No standardized mechanism exists for forest departments to translate national lightning outlooks into operational warnings for frontline staff or local communities.

6.4. Structural & Ecological Mitigation: Global Innovations vs. Indian Practices

-

Global strategies

- o

Lightning protection: Swiss research shows that air-terminal networks can reduce tree-fall risk in arboretums by up to 80% (Rakov, 2003).

- o

Species selection: In pan-tropical plantations, managers favor species with high bark conductivity and rapid resprouting to minimize lightning mortality (Gora et al., 2020).

- o

Fuel-break design: Canadian boreal reserves use strategically placed mineral-soil breaks to interrupt lightning-ignited fire spread (Stocks et al., 1998).

Ad hoc installation of lightning arrestors on watchtowers and eco-camps, without coordinated guidance for species selection or landscape-scale fuel breaks. Restoration plantings seldom consider lightning resilience traits, despite evidence that tall emergent trees face disproportionate strike risk (Yanoviak et al., 2020).

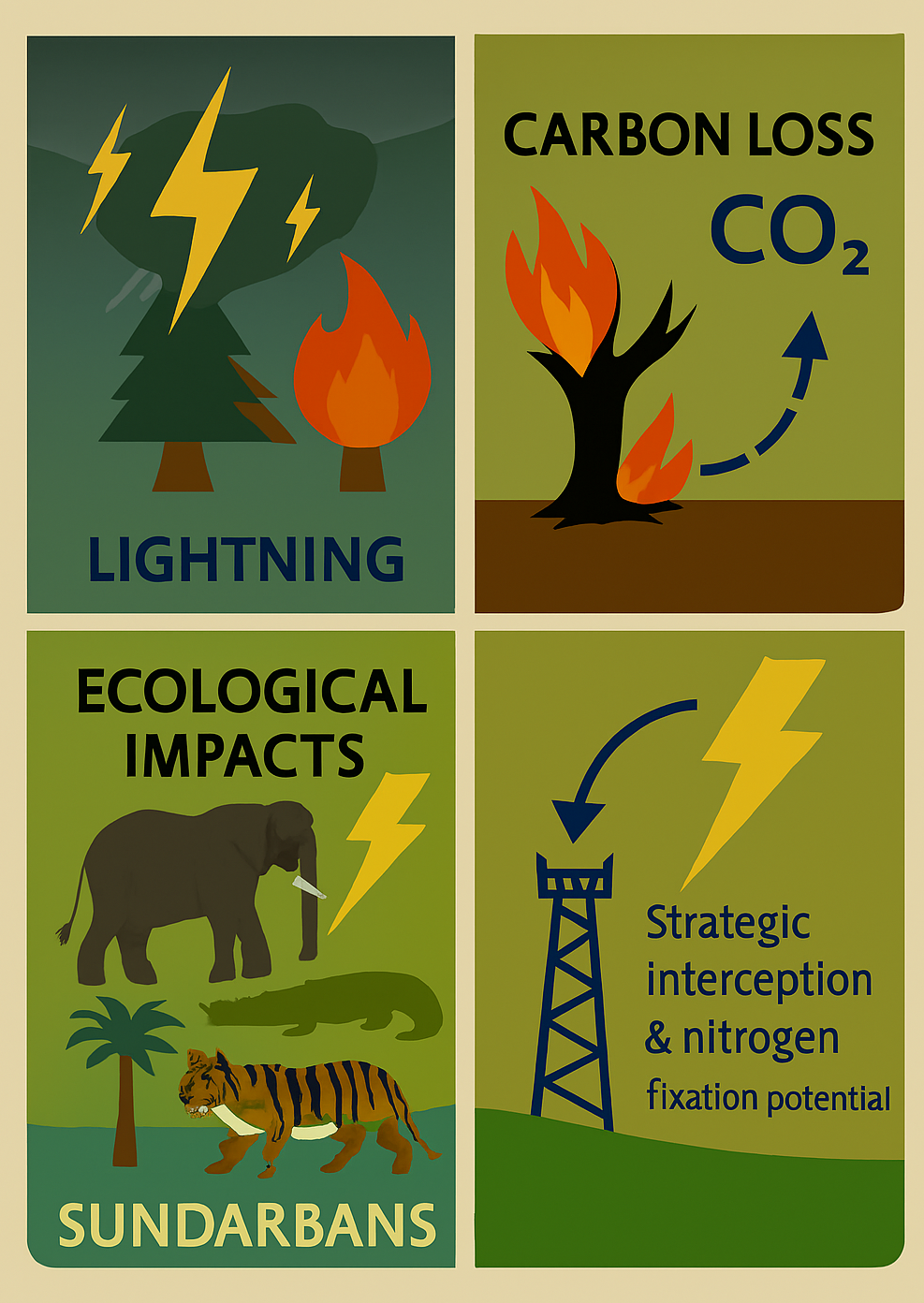

6.5. Strategic Lightning Interception Using Cell Towers

An emerging opportunity lies in repurposing existing cell phone towers across forested coastal regions as strategic lightning interceptors. These towers, already widespread in buffer zones and rural landscapes, could be retrofitted with lightning conductors to divert strikes away from vulnerable canopy trees and wildlife. Positioned near waterholes, migration corridors, or degraded patches, they would not only reduce mortality but also enable localized nitrogen fixation — a natural byproduct of lightning discharge that could enrich soil fertility in restoration zones. With added sensors, these towers could feed real-time strike data into early warning systems, enhancing both ecological resilience and community preparedness.

6.6. Research Integration & Adaptive Policy

Global integration- Boreal and tropical ecological studies inform national strategies—e.g., increasing prescribed burning in lightning-prone boreal regions following Janssen et al. (2023). Savanna management in Africa applies findings on lightning-fire feedbacks to adjust fire frequency and protect key carbon stores (Lehmann et al., 2014).

Indian disconnect- Landmark studies on positive-stroke storms initiating wildfires in India (De, Banik, & Guha, 2024) are absent from state disaster plans. No policy mechanism exists to translate AI/ML-based lightning-fire attribution models into district-level preparedness or restoration guidelines.

By aligning India’s policy and practice with these global standards—explicitly recognizing lightning in forest management frameworks, integrating lightning mortality into MRV, leveraging real-time detection for forest-fire risk reduction, and adopting structural and species-level mitigation measures—India can close critical gaps and enhance the resilience of its forests to one of nature’s most pervasive disturbance agents.

7. Lightning in the Wild: A Regional Survey Across Sundarbans, Similipal, and the Eastern Ghats

Lightning is no longer just a meteorological event—it’s an ecological force. Across Eastern India’s diverse forest landscapes, communities and forest officials are witnessing its growing impact on trees, wildlife, and daily life. This survey-style synthesis captures field observations, local fears, and seasonal patterns from three lightning-prone ecosystems.

7.1. Sundarbans: Mangroves Under Fire

In the low-lying Sundarbans, lightning strikes peak during the monsoon season (June to September), when convective storms sweep across the Bay of Bengal. Tall mangrove species like Heritiera fomes (Sundari) and Excoecaria agallocha (Gewa) are most frequently hit, often showing signs of bark splitting and canopy dieback. Locals report occasional fatalities among estuarine crocodiles and spotted deer, especially near open creeks and mudflats. While tiger deaths remain undocumented, forest guards express growing unease. “We fear the sky more than the swamp,” says a honey collector from Satjelia. The fear is not unfounded—lightning has triggered small fires in degraded mangrove patches and damaged boats during storm crossings. Despite the resilience of mangrove ecosystems, repeated strikes may compromise canopy integrity and reduce blue carbon storage in vulnerable zones.

7.2. Similipal: Sal Forests and Silent Casualties

Similipal’s dry deciduous forests face their highest lightning risk during the pre-monsoon months (April to June), when heat builds over the plateau. Shorea robusta (Sal) trees, which dominate the canopy, are frequent lightning targets due to their height and density. Forest patrols have documented scorched bark, split trunks, and localized canopy gaps. Among wildlife, elephants are particularly vulnerable—two confirmed deaths in 2022 were attributed to lightning strikes near waterholes. Villagers in buffer zones report growing anxiety, especially during sudden afternoon storms. “We used to fear tigers. Now we fear the sky,” says a farmer near Jashipur. Lightning-induced fires are rare but possible, especially in leaf-litter-rich clearings. The absence of localized early warning systems and limited mobile coverage in interior villages heightens the risk for both humans and wildlife.

7.3. Eastern Ghats: Fragmented Forests, Rising Risk

The Eastern Ghats, stretching across Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, experience peak lightning activity during the southwest monsoon and transitional months (May to September). Fragmented hill forests with exposed ridgelines are particularly vulnerable. Trees like Terminalia alata and Anogeissus latifolia are often struck, especially in degraded patches where canopy exposure is high. In Papikonda and Malkangiri, field reports suggest indirect lightning impacts on Indian giant squirrels and small carnivores, though direct fatalities are rare. Tribal communities express deep concern, especially in areas lacking Damini alerts or reliable mobile networks. “We hear the thunder, but we don’t know where it will fall,” says a village elder. Lightning strikes have also damaged solar panels and forest watch posts, underscoring the need for structural protections. Unlike the Western Ghats, the Eastern Ghats lack integrated lightning monitoring or ecological risk assessments, leaving both biodiversity and livelihoods exposed.

8. Discussion

The evidence presented here makes clear that lightning is a pervasive yet overlooked force driving forest change and carbon cycling worldwide. In every corner—from the tallest emergent trees of tropical rainforests to the frozen soils of boreal zones—lightning inflicts direct damage on large, carbon-dense trees and sparks fires that reshape canopy structure and fuel succession. As the climate warms and storm energy intensifies, these fire-lightning feedbacks are only set to grow stronger. In Eastern India, we see these global patterns play out in distinctly local ways: conductive mangrove soils in the Sundarbans amplify strike lethality and peat-ignition risk; the towering Sal stands of Similipal bear scorch scars and, in rare cases, tragic elephant fatalities under pre-monsoon dry lightning; and the exposed hill crests of the Eastern Ghats register elevated flash densities that mirror topographic vulnerability. Together, these observations validate mechanistic lightning-risk frameworks and underscore the urgent need for systematic mortality surveys in India’s under-sampled forest landscapes.

By ignoring lightning-triggered tree mortality and fire pulses, current carbon-accounting systems significantly understate emissions in lightning-prone regions. Bringing stochastic strike losses into national inventories—whether under REDD⁺, blue-carbon protocols, or annual greenhouse-gas reporting—will sharpen our sink-source balances and guide more resilient restoration efforts. On the ground, planting schemes should favor species whose stature and bark traits confer greater strike resistance, and fuel-breaks should align with field-calibrated risk maps that flag canopy height, soil conductivity, and flash-density hotspots. In this way, restoration can evolve from a uniform prescription to a tailored strategy that anticipates lightning’s spatial pulse and protects both biomass and biodiversity.

Despite clear lessons from Canada’s lightning-attribution in wildfire accounting and Europe’s real-time integration of strike data into fire-danger forecasts, India’s forest policies remain silent on lightning. To close this gap, forest legislation at both national and state levels must formally recognize lightning alongside other disturbance agents, and the India State of Forest Report should begin reporting strike impacts in its metrics. Detection networks like WWLLN and Damini need operational links to forest-department bulletins, empowering frontline staff and communities with timely alerts. Finally, simple structural measures—lightning arrestors on watchtowers, eco-camp facilities, and research stations—must become standard practice, backed by clear guidelines for lightning-resilient infrastructure. Only by weaving lightning into the fabric of policy, planning, and practice can India’s forests and the communities that depend on them withstand this elemental challenge.

Author Contributions

Jeevan Nayak: Conceptualization, Investigation, Survey, Writing Original Draft, Methodology, Review and Editing. Manas Ranjan Nayak: Verification, Review & Editing, Supervision. Ashutosh Samal- Methodology, Survey, Review and Editing

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the members of the Villages of Jashipur, Satjelia, and Jharapali for giving their valuable time to answer few of our questions that greatly improved our understanding of the landscape. We would like to specially mention Mr. Siddhuram Rana (Jharapali), Mr. Bhairab Chand Hembram (Jashipur) and Mr. Arka Das (Satjelia) for acting as local guide and help with communication with local people. Language editing and grammar refinement was supported by Grammarly; and Microsoft Word Editor to enhance clarity and readability of the manuscript. Any remaining oversights are solely the author’s responsibility.

Conflict of Interests

The author declares that there are no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acronym

| Serial No |

Acronym |

Expanded form |

| 1 |

MRV |

Measurement, Reporting, and Verification |

| 2 |

REDD+

|

Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation |

| 3 |

IMD |

India Meteorological Department |

| 4 |

NDMA |

National Disaster Management Authority |

| 5 |

LDSN |

Lightning Detection Sensor Network (ISRO–NRSC) |

| 6 |

NRSC |

National Remote Sensing Centre |

| 7 |

GIS |

Geographic Information System |

| 8 |

NLDN |

National Lightning Detection Network |

| 9 |

GEDI |

Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (NASA LiDAR mission) |

| 10 |

IUCN |

International Union for Conservation of Nature |

| 11 |

RET SPECIES |

Rare, Endangered, and Threatened Species |

| 12 |

LiDAR |

Light Detection and Ranging |

| 13 |

PRODES |

Project for Monitoring Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (Brazil) |

| 14 |

UNFCCC |

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| 15 |

LULUCF |

Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry |

| 16 |

EUMETNET |

European Meteorological Network |

References

- Akhter, J., Roy, S., & Midya, S. K. (2024). Assessment of lightning climatology and trends over eastern India and its association with AOD and other meteorological parameters. Journal of Earth System Science, 133, Article 36. [CrossRef]

- Behera, S., Pattanayak, S. K., & Bhadra, A. (2024). The Eastern Ghat of India: A review on plant ecological perspectives. Plant Science Today, 11(3). https://horizonepublishing.com/index.php/PST/article/view/3684.

- Boer, M. M., Resco de Dios, V., & Bradstock, R. A. (2020). Unprecedented burn area of Australian mega forest fires. Nature Climate Change, 10(3), 171-172. [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, M.A. (2009). Fire in the tropics. In: Tropical Fire Ecology. Springer Praxis Books. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Conedera, M., Cesti, G., Pezzatti, G., Zumbrunnen, T., & Spinedi, F. (2006). Lightning-induced fires in the Alpine region: An increasing problem. Forest Ecology and Management, 234, S68. [CrossRef]

- Cummins, K. L., Murphy, M. J., Tuel, J. V., & Global Atmospherics, Inc. (2000). LIGHTNING DETECTION METHODS AND METEOROLOGICAL APPLICATIONS. In IV International Symposium on Military Meteorology. Global Atmospherics, Inc. Tucson Arizona, U.S.A. http://www.atmo.arizona.edu/students/courselinks/spring07/atmo589/articles/Cummins_Poland2000.pdf.

- Dash, M., & Behera, B. (2014). Biodiversity conservation and local livelihoods: A study on Simlipal Biosphere Reserve in India. Journal of Rural Development, 32(4), 409–426. https://www.nirdprojms.in/index.php/jrd/article/view/93325.

- De, D., Banik, T., & Guha, A. (2024). Role of positive outlier cloud-to-ground lightning strokes in initiating forest fires in India. Journal of Earth System Science, 133, Article 215. [CrossRef]

- Dubayah, R., Blair, J. B., Goetz, S., Fatoyinbo, L., Hansen, M., Healey, S., … Houghton, R. (2020). The Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation: High-resolution laser ranging of the Earth’s forests and topography. Science of Remote Sensing, 1, 100002. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2018). Regulation (EU) 2018/841 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the inclusion of greenhouse gas emissions and removals from land use, land-use change and forestry. Official Journal of the European Union, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2018/841/oj/eng.

- Forest Survey of India. (2021). India State of Forest Report 2021. Forest Survey of India, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India. Retrieved July 19, 2025, from https://fsi.nic.in/forest-report-2021.

- Gopal, B., & Chauhan, M. (2006). Biodiversity and its conservation in the Sundarban mangrove ecosystem. Aquatic Sciences, 68(3), 338–354. [CrossRef]

- Gora, E. M., Burchfield, J. C., Muller-Landau, H. C., Hubbell, S. P., & Bitzer, P. M. (2020). A mechanistic and empirically supported lightning risk model for forest trees. Journal of Ecology, 108(6), 1956–1966. [CrossRef]

- Gora, E. M., Bitzer, P. M., Burchfield, J. C., Gutierrez, C., & Yanoviak, S. P. (2021). The contributions of lightning to biomass turnover, gap formation and plant mortality in a tropical forest. Ecology, 102(12). [CrossRef]

- Herold, M., & Skutsch, M. M. (2009). Measurement, reporting and verification for REDD+. In Measurement, reporting and verification for REDD+. https://www.cifor-icraf.org/publications/pdf_files/Books/BAngelsen090207.pdf.

-

IUCN. (2023). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Version 2023-2). Retrieved July 19, 2025, from https://www.iucnredlist.org.

- Janssen, T.A.J., Jones, M.W., Finney, D. et al. Extratropical forests increasingly at risk due to lightning fires. Nat. Geosci. 16, 1136–1144 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, C. E. R., Anderson, T. M., Sankaran, M., Higgins, S. I., Archibald, S., Hoffmann, W. A., Hanan, N. P., Bond, W. J. et al. (2014). Savanna Vegetation-Fire-Climate relationships differ among continents. Science, 343(6170), 548–552. [CrossRef]

- Moos, C., Stritih, A., Teich, M., & Bottero, A. (2023). Mountain protective forests under threat? an in-depth review of global change impacts on their protective effect against natural hazards. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 6. [CrossRef]

- Müller, M. M., Vilà-Vilardell, L., & Vacik, H. (2020). Towards an integrated forest fire danger assessment system for the European Alps. Ecological Informatics, 60, 101151. [CrossRef]

- NDMA. (2019). Lightning resilience in India. National Disaster Management Authority. https://ndma.gov.in/sites/default/files/NLJuly24/images/LIGHTNING-RESILIENCE-IN-INDIA.pdf.

- Natali, S. M., Holdren, J. P., Rogers, B. M., Treharne, R., Duffy, P. B., Pomerance, R., & MacDonald, E. (2021). Permafrost carbon feedbacks threaten global climate goals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(21). [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Soil Survey and Land Use Planning. (2021). Soil and land use database and map series. NBSS&LUP, Indian Council of Agricultural Research, https://slusi.da.gov.in/index_English.html.

- Nepstad, D., McGrath, D., Stickler, C., Alencar, A., Azevedo, A., Swette, B., Bezerra, T., DiGiano, M., Shimada, J., Da Motta, R. S., Armijo, E., Castello, L., Brando, P., Hansen, M. C., McGrath-Horn, M., Carvalho, O., & Hess, L. (2014). Slowing Amazon deforestation through public policy and interventions in beef and soy supply chains. Science, 344(6188), 1118–1123. [CrossRef]

- NRSC. (2023). Lightning Detection System (LDS) Network in India. National Remote Sensing Centre, ISRO. https://www.nrsc.gov.in/sites/default/files/ScienceStory/Science_Story_LDS_NetworkinIndia.pdf.

- Press Information Bureau. (2022, April 6). Death due to lightning strikes [Press release]. Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1813993.

- Rakov V.A., Lightning: physics and effects. (2003). In Lightning: Physics and Effects. Cambridge University Press. https://assets.cambridge.org/97805210/35415/frontmatter/9780521035415_frontmatter.pdf.

- Rodger, C. J., Brundell, J. B., & Dowden, R. L. (2005). Location accuracy of VLF World-Wide Lightning Location Network after algorithm upgrade. Annales Geophysicae, 23(1), 277–290. [CrossRef]

- Romps, D. M., Seeley, J. T., Vollaro, D., & Molinari, J. (2014). Projected increase in lightning strikes in the United States due to global warming. Science, 346(6211), 851–854. [CrossRef]

- Stocks, B. J., Fosberg, M. A., Lynham, T. J., Mearns, L., Wotton, B. M., Yang, Q., Jin, J., Lawrence, K., Hartley, G. R., Mason, J. A., & McKENNEY, D. W. (1998). Climate change and forest fire potential in Russian and Canadian boreal forests. Climatic Change, 38(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Trollope, W. S. W., Trollope, L. A., & Working On Fire International. (2009). Fire effects and management in African grasslands and savannas. In Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS), Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS): Vol. II.

- Turetsky, M. R., Abbott, B. W., Jones, M. C., Anthony, K. W., Olefeldt, D., Schuur, E. a. G., Grosse, McGuire, A. D. et al. (2020). Carbon release through abrupt permafrost thaw. Nature Geoscience, 13(2), 138–143. [CrossRef]

- Van Wees, D., Van Der Werf, G. R., Randerson, J. T., Rogers, B. M., Chen, Y., Veraverbeke, S., Giglio, L., & Morton, D. C. (2022). Global biomass burning fuel consumption and emissions at 500 m spatial resolution based on the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED). Geoscientific Model Development, 15(22), 8411–8437. [CrossRef]

- Veraverbeke, S., Rogers, B. M., Goulden, M. L., Jandt, R. R., Miller, C. E., Wiggins, E. B., & Randerson, J. T. (2017). Lightning as a major driver of recent large fire years in North American boreal forests. Nature Climate Change, 7, 529–534. [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C., Osberg, G., Osika, W., Herndersson, H., & Mundaca, L. (2021). Linking internal and external transformation for sustainability and climate action: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Global Environmental Change, 71, 102373. [CrossRef]

- Yanoviak, S. P., Gora, E. M., Burchfield, J. C., Detto, M., & Schnitzer, S. A. (2020). Lianas increase lightning-caused disturbance severity in a tropical forest. New Phytologist, 238(5), 1865–1875. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).