1. Introduction & State-of-the-Art (Chronological)

Hydrogen is central to deep decarbonization scenarios across chemicals, fuels, and heavy industry, yet the dominant route—steam methane reforming (SMR)—emits substantial CO₂ unless paired with capture and storage [

7,

8]. Methane pyrolysis (a.k.a. turquoise hydrogen) splits CH₄ directly to H₂ and solid carbon, eliminating process CO₂ formation at the reactor and creating a potential dual-product business model when carbon meets carbon-black specifications [

1,

4,

9,

22,

33]. Compared with electrolysis, pyrolysis targets high-temperature heat rather than electricity input to water splitting; when that heat is provided by low-carbon sources and carbon is valorized, levelized H₂ cost (LCOH) can be competitive [

1,

3,

9,

21,

29,

30,

31,

32].

Two technical hurdles define deployment readiness: (i) thermal supply and control at 600–900 °C to sustain conversion/selectivity without accelerating deactivation, and (ii) carbon separation/handling to protect downstream equipment and preserve co-product value [

1,

2,

4,

10,

12,

23,

24,

33]. To address (i), we consider hybrid geothermal–pyrolysis: use an enhanced geothermal system (EGS) for preheat and isothermal hold (baseload duty), and apply electrical or solar-thermal top-up for the final temperature approach and transients [

6,

10,

21,

26,

34]. To address (ii), we synthesize molten-media and gas-phase evidence on particle formation, disengagement, and polishing to meet carbon-black markets [

4,

12,

13,

21,

24,

33].

1.1. Why Turquoise Hydrogen Now

Recent field-scale integration studies and reviews highlight three levers that co-dominate LCOH: specific electric duty, carbon co-product price/specification, and methane price; policy credits and site heat resources modulate all three [

1,

2,

3,

4,

7,

9,

21,

22,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Geothermal preheat can reduce electric top-up and stabilize reactor temperature, thereby (a) mitigating coking/sintering dynamics and (b) narrowing particle size distributions upstream of cyclones/filters—both supportive of higher carbon value capture [

1,

4,

10,

12,

21,

24,

33]. Recent system analyses of baseload and flexible EGS power/thermal delivery provide the operating envelopes to ground heat-integration targets and capacity factors [

26], complemented by standard geothermal reservoir design practice [

29,

34].

1.2. State-of-the-Art — a Concise Chronology

2015–2017: Foundational demonstrations and the first economic framing.Liquid-metal / molten-media concepts advanced from theory to bubble-column experiments, elucidating gas–liquid mass transfer, reaction zones, and initial solid-carbon separation approaches [

13]. A landmark molten-metal catalysis demonstration showed direct CH₄-to-H₂ with separable carbon, igniting modern turquoise-H₂ interest [

6]. Early techno-economic work crystallized the sensitivity of costs to power demand and carbon value, setting baselines for later TEA templates [

9].

2019–2021: Kinetics, catalysts, and system comparisons mature.Reviews consolidated temperature windows (~600–900 °C), catalyst families (Ni/Fe/Co; doped systems), and deactivation modes, while drawing comparisons with SMR + CCS pathways for long-term roles of hydrogen [

5,

7,

8,

10,

12]. Process-level studies sharpened understanding of molten-salt and liquid-metal operation, carbon morphology, and implications for downstream handling [

12,

13,

15]. A broad industrial context emerged in which turquoise hydrogen complements rather than replaces other routes [

7,

8,

10].

2022–2023: Scale-relevant engineering, solar/electric heating, and carbon handling. Comprehensive reviews and mini-reviews emphasized molten-media advances and product-quality control [

1,

4,

10]. Comparative reactor studies contrasted gas-phase versus molten-tin bubbling systems under solar input, linking temperature uniformity to particle size and filtration load [

21]. Engineering studies explored plasma and H₂-combustion-heated pyrolysis concepts that simplify heat delivery while retaining CO₂-free operation [

23,

24]. In parallel, cyclone design literature from process engineering was tapped to specify disengagement and polishing trains suitable for carbon-laden off-gas [

24].

2024–2025: Integration, high-pressure kinetics, predictive modeling, and EGS coupling.High-pressure kinetics and modeling tightened scale-up envelopes and helped define pressure–temperature trade-offs for compact equipment and improved H₂ recovery [

16,

19]. Predictive catalytic models are emerging to bridge laboratory selectivity with pilot reactors [

19]. On the system side, power-supply characterization for EGS quantified baseload/flexible delivery relevant to hybrid heat trains [

26], while TEAs extended to ammonia contexts and dual-product revenue stacking (H₂ + carbon) [

25]. Across these strands, the integration narrative has shifted from proof-of-concept to site-coupled process engineering, making geothermal-assisted pyrolysis a concrete target for FEED-level design [

1,

2,

3,

4,

10,

16,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

1.3. This Paper’s Contribution

Building on that arc, this work contributes four things tailored to deployment:

Heat-integration blueprint grounded in real EGS operating envelopes (preheat/isothermality by EGS; last-mile ΔT by electric/solar), with duty splits and control strategy implications [

6,

10,

21,

26,

29,

34].

Scalability guidance for high-pressure reactor design, materials, and thermal-stress management; plus operating rules that minimize deactivation and preserve carbon value [

1,

2,

12,

15,

16,

21,

29,

31,

32].

A TEA scaffold that explicitly itemizes CAPEX/OPEX, includes carbon credit/value stacking, and quantifies dual-product economics using established process-design texts and turquoise-H₂ TEAs [

1,

2,

3,

4,

9,

21,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

Reporting guidelines (Methods) so others can reproduce integration choices—heat curves, reactor details, carbon QA/QC, and financial assumptions—in line with good engineering practice [

9,

21,

30,

31,

32].

2. Concept & Real-World Anchors (EGS → Pyrolysis)

2.1. Process Concept and Duty Split (see Fig. 1)

Dry methane is preheated using an enhanced geothermal system (EGS) loop to approach the catalytic window, then receives top-up heat (electric resistive or solar-thermal) to reach the reactor setpoint (typically 600–900 °C, depending on reactor/catalyst) [

1,

2,

10,

12,

21,

34]. The reactor can be either (a) a molten-media bubble column (Sn/Bi or molten salts) or (b) a packed/fixed bed. Effluent hydrogen is separated and compressed, and solid carbon is recovered, de-oiled/conditioned, and sent to classification for carbon-black (CB) and related markets [

4,

12,

13,

22,

33]. (see Fig. 2)

Heat-integration logic.

- ▪

Assign EGS to baseload sensible heat on the largest heat-capacity flows (fresh CH₄, recycle, and—where applicable—the molten medium’s isothermal hold).

- ▪

Reserve electric/solar for the last ΔT (typically the final 200–300 K into the catalytic window) and for transients (startup, ramping, turndown) [

10,

21,

26,

34].

- ▪

In composite/pinch terms, place EGS on the cold streams with highest

to maximize kWth captured per unit of geothermal temperature glide; use short, insulated trim-heater sections to avoid large hot inventories [

21,

26,

34].

Indicative split. While site-specific, a practical design target is EGS covering the majority of sensible preheat (e.g., 50–80 % of the total sensible duty to the reactor feed/recycle) with top-up supplying the final approach to setpoint and transient control [

1,

4,

10,

21,

26].

2.2. Why Geothermal Here?

Baseload preheat & isothermal hold. EGS delivers steady thermal duty, reducing electric top-up demand and smoothing the reactor temperature profile—mitigating coking swings, thermal shock, and catalyst stress [

6,

10,

12,

26,

34].

System reliability. Modern EGS analyses characterize both baseload and flexibility envelopes, allowing the geothermal loop to serve as a heat backbone with predictable capacity factors, supported by established reservoir engineering practice [

26,

34].

Carbon-quality management. A steadier wall/film temperature narrows particle-size distributions (PSD) and reduces agglomeration, which eases cyclone duty and porous-ceramic polishing, protecting compressors, membranes/PSA beds, and exchangers downstream [

12,

21,

23,

24,

33].

2.3. Reactor Options and Operating Envelopes

Molten-media bubble column (Sn/Bi/salts).

- ▪

Advantages: intense gas–liquid heat transfer; in-situ carbon disengagement (sump/rathole) and potential isothermal hold; tolerant to some feed/recycle swings [

12,

13,

21].

- ▪

Design notes: corrosion-resistant alloys; double containment; provision for melt make-up and conditioning; off-gas disengagement to protect downstream separation [

12,

13,

21,

24].

- ▪

Packed/fixed bed.

- ▪

Advantages: compact hardware, established catalyst practice; straightforward modularization for parallel train scale-up [

1,

2,

12].

- ▪

Design notes: strong emphasis on axial/radial thermal uniformity; manage pressure-drop and carbon removal cadence to avoid sintering/plugging; keep trim-heater residence short [

1,

2,

10,

12,

21].

Setpoint selection. The 600–900 °C window reflects kinetic/thermodynamic trade-offs and catalyst family (Ni/Fe/Co; molten salts/metals) [

1,

2,

10,

12]. Operation near the upper activity range improves conversion but raises the importance of isothermal control and carbon removal [

12,

21,

24].

2.4. Hydrogen Separation & Recycle

The H₂-rich stream is routed to PSA or membrane separation and then to compression. An off-gas recycle closes the carbon balance and lifts overall CH₄ conversion; a small purge maintains inert build-up control [

12,

21,

24,

33]. EGS-assisted preheat improves separator thermal stability and can reduce electric duty swings on compressors by smoothing reactor output [

10,

21,

26].

2.5. Carbon Handling and Value Preservation

Target handling that protects CB value and downstream assets:

- ▪

Primary disengagement: gravity sump for molten systems; or tempered quench followed by cyclone for gas-phase routes [

13,

21,

24].

- ▪

Polishing: porous-ceramic filters sized for PSD and target cut size before classification (air-jet/sieving) to CB specifications [

4,

22,

33].

- ▪

QA/QC: report PSD, BET surface area, volatile/ash content; minimize oxidation and high-temperature residence post-reactor to avoid surface chemistry changes that depress CB pricing [

4,

22,

33].

2.6. Controls, Start-Up, and Operability

- ▪

Dual-loop control: a slow loop on the EGS supply/return sets baseload preheat; a fast loop at the trim heater manages the final ΔT and transients (start, ramp, trip recovery) [

10,

21,

26,

34].

- ▪

Start-up: warm feed/recycle on EGS heat to a safe intermediate temperature, then bring trim heat online to the catalytic setpoint, minimizing overshoot that promotes coking/sintering [

10,

12,

21].

- ▪

Maintenance envelopes: schedule carbon removal (fixed bed) or sump clearing (molten media); maintain filter differential-pressure limits and compressor surge margins with conservative recycle control [

12,

21,

24,

33].

2.7. Site–EGS Coupling and Reporting Guidance

- ▪

Match EGS temperature and flow envelope to process composite curves; document capacity factor, expected seasonality, and any flex provision (e.g., curtailed electric top-up or thermal storage if used) [

26,

34].

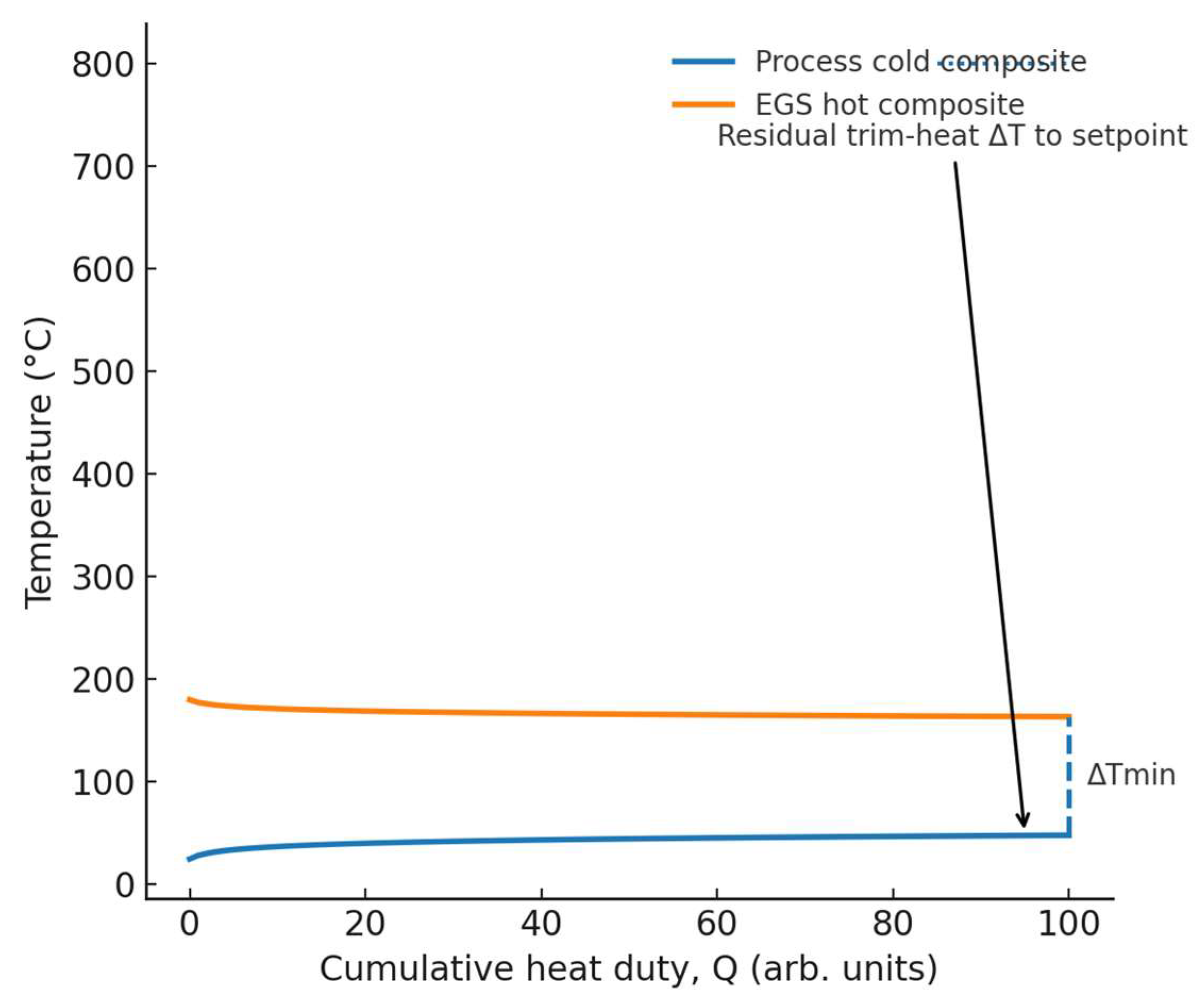

Figure 1.

Block flow — EGS loop → preheaters → pyrolysis reactor → H₂ separation → carbon handling.

Figure 1.

Block flow — EGS loop → preheaters → pyrolysis reactor → H₂ separation → carbon handling.

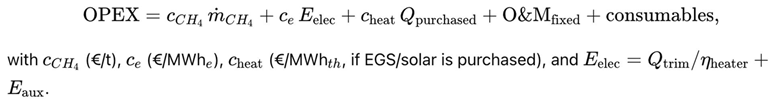

Figure 2.

Pinch-style heat map — match highest ṁcₚ streams to EGS; ΔTmin and residual trim-heat ΔT annotated.

Figure 2.

Pinch-style heat map — match highest ṁcₚ streams to EGS; ΔTmin and residual trim-heat ΔT annotated.

- ▪

For reproducibility, report heat-curves, major equipment sizes, duty splits (EGS vs. trim), catalyst/melt composition, carbon QA/QC metrics, and separation/pressure targets—aligned with best practice from recent turquoise-H₂ TEAs and standard process-design methodology [

1,

4,

9,

21,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

As a real-world anchor, Utah FORGE (Milford, UT) demonstrated engineered doublet performance in Apr–May 2024: injection into 16A(78)-32 up to 15 bpm (≈630 gpm) with production from 16B(78)-32 up to 8 bpm (≈344 gpm, ~70% recovery) and outflow ≈139 °C; the target reservoir exceeds ~175 °C at ~2–2.5 km depth—quantitatively defining a baseload EGS preheat window for our integration

3. Scalability: High-Pressure Design, Thermal Management, Carbon Separation

3.1. High-Pressure Reactor Design

Operating envelope and scale-up logic

- ▪

Why pressure? Higher pressure compacts hardware (smaller volumetric flows, smaller diameters/compressors) and improves downstream H₂ recovery (membranes/PSA utilization) at a given throughput [

1,

2,

16]. Because

increases gas moles, elevated pressure penalizes equilibrium conversion; you counterbalance with temperature and residence time. Practically, 10–25 bar with 600–900 °C is a workable FEED envelope, with setpoint chosen by catalyst/melt system and deactivation tolerance [

1,

2,

10,

12,

16,

21].

- ▪

-

Reactor choices at HP:

- ○

Molten-media bubble column (Sn/Bi/salts). HP raises gas density and bubble coalescence risk; keep superficial gas velocity in a churn-turbulent window that sustains fine bubbles without flooding. Use sparger hole velocities

and L/D ≈ 8–15 as starting points; confirm via hydrodynamic tests [

12,

13,

21].

- ○

Packed/fixed bed. HP increases ΔP; design

to stay within blower/compressor head while ensuring Da > 1 at setpoint. Use short trim-heater sections to avoid hot inventory and mitigate sintering/coking [

1,

2,

10,

12,

21].

- •

Kinetic/equilibrium guidance (design checks):

At a chosen pressure, push

high enough that

comfortably exceeds your per-pass target, then size residence time so

with margin. Recycle closes the gap to near-complete overall conversion [

1,

2,

10,

12].

Materials & containment (HP/HT)

- ▪

Codes & margins. Design to ASME VIII with transient thermal-cycling load cases and creep allowances at the upper temperature bound; specify testable corrosion allowances in hot zones and penetrations [

13,

21,

34].

- ▪

Molten-media compatibility. Sn/Bi and halide salts demand corrosion-resistant alloys, fully welded construction, and double-walled containment with leak detection. Provide melt make-up/conditioning loops and thermal buffers around nozzles to limit thermal shock [

12,

13,

21,

24].

- ▪

Hydrogen service. Avoid embrittlement-prone steels in high-

areas; prefer austenitic SS or high-Ni alloys in hot H₂ and at HP separators/compressors [

12,

21,

24,

34].

- ▪

Catalysts at scale (HP + thermal field)

- ▪

Formulation. Favor Fe/Co-rich systems for robustness and cost; Ni is highly active but requires tight temperature uniformity and carbon removal cadence to control sintering/coking [

1,

2,

12,

15,

21,

29].

- ▪

Geometry & loading. For beds, use radial/segmented distributors and graded particle sizes to limit hot spots and ΔP growth. In melts, add inert internals or controlled swirl to enhance gas–liquid heat transfer without excessive shear [

12,

13,

21].

- ▪

Deactivation playbook. Maintain isothermal operation, schedule carbon draw-off (sump clearance or bed skimming), and cap startup/shutdown dT/dt to protect active phases [

1,

2,

12,

21,

24].

3.2. Thermal Management

Duty split (EGS vs. trim)

- ▪

Principle. Assign EGS to the largest

streams for baseload sensible preheat and (for melts) isothermal hold; reserve electric/solar for the last-mile ΔT (≈ 200–300 K) and ramping [

1,

4,

6,

10,

21,

26,

34].

- ▪

Typical target. EGS covers ~50–80 % of the total sensible duty to the reactor feed/recycle; the trim heater provides the remaining ΔT to setpoint and manages transients [

1,

4,

10,

21,

26].

- ▪

Pinch framing. Choose

(e.g., 10–20 K for compact HX trains) and match EGS to the cold composite up to the pinch; the residual trim-heat ΔT (Fig. 2) is then a design variable that trades capex vs. electric intensity and carbon morphology stability [

21,

26,

34].

Control strategy (scale-ready)

- ▪

-

Dual-loop temperature control.

- ○

Slow loop: regulates EGS inlet/return to hold baseload duty (minutes-hours time constant).

- ○

Fast loop: trims reactor skin/bed temperature at H-101 to suppress hot spots that drive catalyst decay and PSD drift in the carbon product [

1,

12,

23,

24].

- ▪

Start/stop & turndown. Warm on EGS to an intermediate plateau, then step in trim heat to setpoint; on turndown, lead with trim reduction, hold EGS steady to avoid quenching through the strong coking regime [

10,

12,

21].

- ▪

Instrumentation. Redundant TC grids or IR pyrometry on hot surfaces; ΔP across filters; cyclone dP and classifier load; compressor surge margin monitoring. Tie trips to conservative limits on skin ΔT and filter dP [

12,

21,

24,

33].

3.3. Carbon Separation & Handling

Inside the reactor (primary solids management)

- ▪

Molten columns. Provide a gravity sump/rathole for agglomerates; skim settled carbon on cadence and keep interfacial shear low to preserve particle size [

13,

21,

24,

33].

- ▪

Gas-phase/heliostat routes. Apply a tempered quench (enough to freeze growth/sintering, not enough to oxidize) before solids capture to protect morphology and downstream equipment [

13,

21,

23,

24].

Primary separation & polishing

- ▪

Cyclone. Size for target cut size d₅₀ (typ. 2–10 µm for CB-value preservation) using a Stairmand-type geometry; expect ΔP ≈ 1–2 kPa at design flow. Keep Stokes number in the effective capture regime for the PSD of interest and allocate parallel cyclones to handle scale-out [

24,

33].

- ▪

Porous-ceramic polishing. Follow with a ceramic filter to capture fines and protect compressors/PSA/membranes/HEX. Design face velocity in the 1–3 cm s⁻¹ band and backpulse on ΔP; provide bypass/swing cartridges for continuous operation [

24,

33].

- ▪

Value preservation and product finishing

- ▪

Dry handling. Keep carbon dry, cool, and oxygen-limited post-reactor; over-oxidation or graphitization erases CB value unless you are intentionally targeting graphite/graphene markets [

4,

22,

33].

- ▪

Classification. Route to air-jet/sieve classifiers tuned to CB specifications; report PSD (D₁₀/D₅₀/D₉₀), BET area, volatiles/ash, and DBP oil absorption as QA/QC (see Fig. 3) [

4,

22,

33].

- ▪

Fugitive control. Enclose transfer points; maintain slight negative pressure; specify NFPA-conformant dust collection with conductive media in H₂ areas (materials to suit H₂ service) [

12,

21,

24,

33].

3.4. Practical Design Rules (Ready for the Methods Box)

- ▪

Pressure & T: Start FEED with 10–25 bar, 600–900 °C; verify ) and ; close with recycle.

- ▪

EGS split: target ≥ 50 % of sensible preheat from EGS; set

=10–20K; keep trim ΔT short to reduce electric intensity and morphology drift [

1,

4,

21,

26,

34].

- ▪

Thermal uniformity: cap skin–bulk ΔT and axial ΔT; limit dT/dt at startup/shutdown; instrument surfaces densely [

1,

12,

23,

24].

- ▪

Carbon PSD: cyclone

=2–10µmd_{50}=2–10

; filter face velocity = 1–3 cm s⁻¹; protect compressors/separators with polishing filters [

24,

33].

- ▪

Maintainability: design sump/bed clear-out operations; provide filter swing and cycler logic; spec spare spargers/distributors for quick changeover [

12,

21,

24,

33].

4. Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA)

4.1. Scope & Cases

Plant basis. Nameplate ~10 kt H₂·yr⁻¹ (≈ 1.25 t H₂·h⁻¹ at 8,000 h·yr⁻¹), EGS-assisted preheat, single site boundary from methane reception to H₂ product delivery and carbon product bins. Units included: methane conditioning, preheaters, trim heater, pyrolysis reactor(s), molten-media/salt inventory (if applicable), H₂ separation and compression, carbon handling (sump/tempered quench, cyclone, porous ceramic filters, classifier), HX trains, electrical and/or solar top-up, and plant controls/utilities. TEA framing follows molten-media/fixed-bed literature and reviews [

1,

2,

4,

9,

21]; costing follows standard process-economics methods [

30,

31,

32] with geothermal design context from [

34].

Comparison set.

- ▪

EGS + electric top-up: EGS supplies baseload sensible preheat/isothermal hold; electric provides last-mile ΔT and transients.

- ▪

Solar-thermal + electric: solar field (and, if used, thermal storage) supplies preheat; electric trims to setpoint.

- ▪

Electric-only: all duty from electric heaters (simplest hardware; highest kWh exposure).

Boundary notes. Owner’s costs, working capital, land, and grid interconnection fees can be carried as indirects; EGS can be owned (CAPEX for wells & tie-in) or contracted as purchased thermal duty (OPEX). Cases A–C share identical process hardware except for the heat-supply block.

4.2. Cost Structure

CAPEX (installed):

- ▪

Heat supply: EGS wells + surface HX + tie-in (or purchased-heat interface); solar collector field & thermal storage (case B); electric trim heaters and power distribution [

9,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

- ▪

Core process: pyrolysis reactor trains (molten-media column or packed/fixed bed), melt/salt inventory (if used), spargers/distributors, refractory/linings, structural steel [

1,

2,

12,

21].

- ▪

Separation & compression: PSA or membranes, H₂ compressors/dryers, product storage [

12,

21,

30,

31,

32].

- ▪

Carbon handling: sump/tempered quench, cyclones, porous-ceramic filters (swing/bypass), classifier and product bins [

24,

33].

- ▪

HX trains & balance of plant: feed/recycle exchangers, cooling water/air coolers, nitrogen, inerting, controls, analytics, safety systems [

30,

31,

32].

Cost estimation by Bare-Module / Lang-factor or equipment-factored methods per [

30,

31,

32]; EGS well costs and surface tie-ins follow geothermal practice [

34].

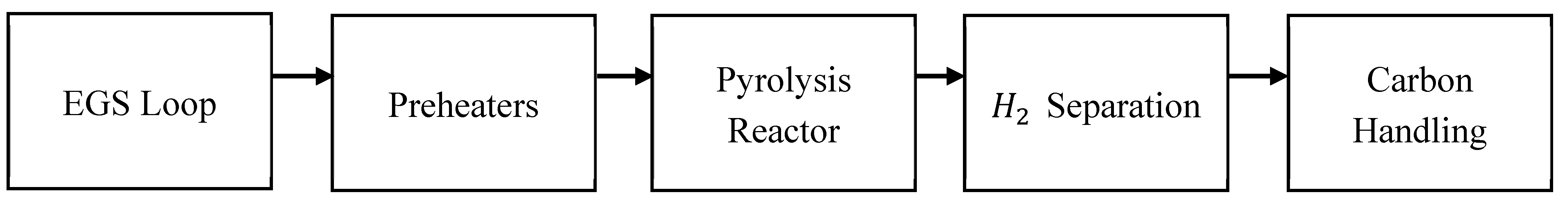

OPEX (annual):

- ▪

Feed & energy: CH₄ make (net of recycle), electric power for trim + auxiliaries; (B) solar O&M; (A) EGS O&M or purchased heat tariff [

1,

2,

9,

21,

30,

31,

32,

33].

- ▪

Consumables: catalyst/melt make-up, filtration media, inert gases; water for quench/utility.

- ▪

Fixed: labor, maintenance, insurance, compliance, waste solids (off-spec carbon fines), spare parts [

30,

31,

32].

Throughput-linked stoichiometry. For : 4 kg CH₄ per 1 kg H₂ at 100% overall conversion; 3 kg C per 1 kg H₂ formed. Let be overall CH₄-to-H₂ yield (after recycle); then:

with the saleable carbon-black fraction after classification.

Heat & power. Total duty per kg H₂ is the sum of reaction endotherm

and sensible preheat for feed/recycle (and melt hold, if used). Allocate EGS to high-

preheat; the residual trim duty

sets electric use

=

/

η [

1,

4,

21,

26,

34].

4.3. Revenue & Policy Levers

- ▪

H₂ product. Off-take price depends on delivery pressure/purity and contract tenor; compression costs scale with setpoint and pipeline/storage spec.

- ▪

Carbon co-product. Revenue rises with tighter PSD and low volatiles/ash; specialty CB grades command a premium vs commodity carbon [

4,

22,

33]. Use a grade mix:

with grade-specific price

and mass yield

.

- ▪

Carbon credits / policy. Stack production credits or market-based carbon prices where eligible; LCOH sensitivity is strong to this term when power carbon intensity (CI) is low and carbon sale value is high [

7,

8,

9,

27,

29]. Cases with EGS preheat reduce electric demand, improving both cost and CI exposure [

1,

4,

21,

26,

34].

4.4. Calculation Framework

Define the levelized cost of hydrogen:

where

is

the annual H₂ output (nameplate × capacity factor).

Capital recovery factor (annualization) per [

30,

31,

32]:

with discount rate iii and plant life nnn (years). For multi-block CAPEX, sum contributions (e.g., EGS, reactors, separation) before applying CRF, or annualize each block separately if lifetimes differ.

Case-specific heat terms (duty split):

- ▪

EGS + electric: covers preheat/isothermal hold, the last-mile ΔT and transients.

- ▪

Solar-thermal + electric: replace with ; storage adds CAPEX and reduces electric exposure.

- ▪

Electric-only: ≈ (highest kWh exposure; simpler CAPEX).

OPEX decomposition (per year):

Co-product treatment. Use a revenue credit (preferred for journals) or co-allocation if required by policy reporting:

depends on saleable mass (after classification) and grade pricing; document the grade split and QA/QC metrics supporting it [

4,

22,

33].

Emissions & CI. Compute plant CI from upstream CH₄, electricity CI, and any EGS/solar impacts; credit solid-carbon fixation where policy allows. Lower

in (A)/(B) typically yields favorable CI relative to (C) [

1,

4,

21,

26,

34].

4.5. Sensitivities & Expected Findings

Sensitivity set: CH₄ price, electricity price/CI, EGS (or solar) capacity factor, carbon sale price/grade split, overall conversion/selectivity, and discount rate. Prior TEA work shows carbon revenue and electric demand are the dominant levers [

9], consistent with the heat-split strategy that shifts duty to EGS/solar [

1,

4,

21,

26,

34].

Typical qualitative outcomes (at equal H₂ output):

- ▪

EGS + electric: lowest LCOH where EGS CF is high and purchased/owned geothermal heat is economical; strong resilience to power price/CI swings.

- ▪

Solar-thermal + electric: improved CI and reduced kWh exposure vs (C); CAPEX rises (field + storage) and economics hinge on solar CF and storage sizing.

- ▪

Electric-only: simplest CAPEX, highest LCOH variance with electric price/CI; a useful baseline for comparing A/B.

Implementation checklist (for your model workbook)

- ▪

Fix nameplate → annual H₂ via capacity factor; compute CH₄, C via stoichiometry × yields.

- ▪

Break CAPEX into blocks; apply CRF; add OPEX components.

- ▪

Calculate and from your heat-integration (Fig. 2); convert to electricity.

- ▪

Add revenues: H₂ off-take, carbon grade mix, policy credits.

- ▪

Run A/B/C and the sensitivity set; report tornado bars for LCOH and identify breakeven thresholds (e.g., carbon price vs. electricity price).

5. Methods (What to Report so Reviewers Can Reproduce)

5.1. Process Basis and Heat-Integration Data (see Fig. 2)

Report the system boundary, operating mode, and full composite-curve inputs so an independent team can rebuild the heat match.

Minimum items to publish (data table):

- ▪

Basis & boundary: nameplate H, capacity factor, overall yield after recycle, site ambient.

- ▪

EGS loop: production temperature/flow, reinjection temperature, supply/return variability (±σ or bands), and any thermal storage used [

21,

26,

34].

- ▪

Process cold streams (each): identification (fresh , recycle, melt hold if applicable), mass flow mean correlation, inlet/outlet T, allowable approach

- ▪

Process hot streams (each): if any internal hot utility is matched, provide , , T-in/T-out.

- ▪

Pinch reconstruction: composite curves (T vs. cumulative ) for EGS supply and process demand; annotated pinch and residual trim-heat pre-setpoint (Fig. 2).

- ▪

Duty split:

with heater efficiency used, plus ramp/turn-down envelopes [

21,

26,

34].

Calculation notes (publishable):

; show how was selected (e.g., 10–20 K) and how residual maps to electric load .

5.2. Reactor Details (Geometry, HP/HT Envelope, Internals)

Provide enough hardware and operating detail to permit a rate-based model and pressure-drop check.

Common to all reactor types:

- ▪

Type & flow scheme: molten-media bubble column vs. packed/fixed bed; co-current/counter-current arrangements.

- ▪

Geometry: ID/OD, effective height/length, L/D, number of parallel trains; nozzle sizes and sparger pattern (if molten).

- ▪

Operating points: pressure, reactor setpoint temperature (°C), axial/radial temperature uniformity targets, residence time τ\tauτ definition.

- ▪

Throughput: fresh CH₄, recycle ratio, total superficial velocity; pressure-drop targets and measured values.

Molten-media specifics:

- ▪

Medium: alloy/salt identity and composition, total inventory (kg), make-up/bleed, liquidus/solidus temperatures.

- ▪

Hydrodynamics: sparger hole size & count, gas superficial velocity, bubble size estimate or fit; internal features for heat transfer [

12,

13,

21].

- ▪

Materials/containment: alloy selection, double-wall/secondary containment, corrosion allowance, thermal-cycling design case, code stamping [

13,

21,

34].

- ▪

Packed/fixed-bed specifics:

- ▪

Catalyst: active metals (Fe/Co/Ni), promoter/support, pellet size & porosity; total loading (kg).

- ▪

Distribution: inlet distributor design, bed segmentation or grading, measures for radial uniformity; trim-heater residence minimization [

1,

2,

12,

15,

21,

29].

- ▪

Kinetics & performance reporting:

- ▪

Conversion, H₂ selectivity/yield, deactivation rate (e.g., %/100 h), carbon production rate and removal cadence; publish data as

- ▪

contours or time-on-stream plots.

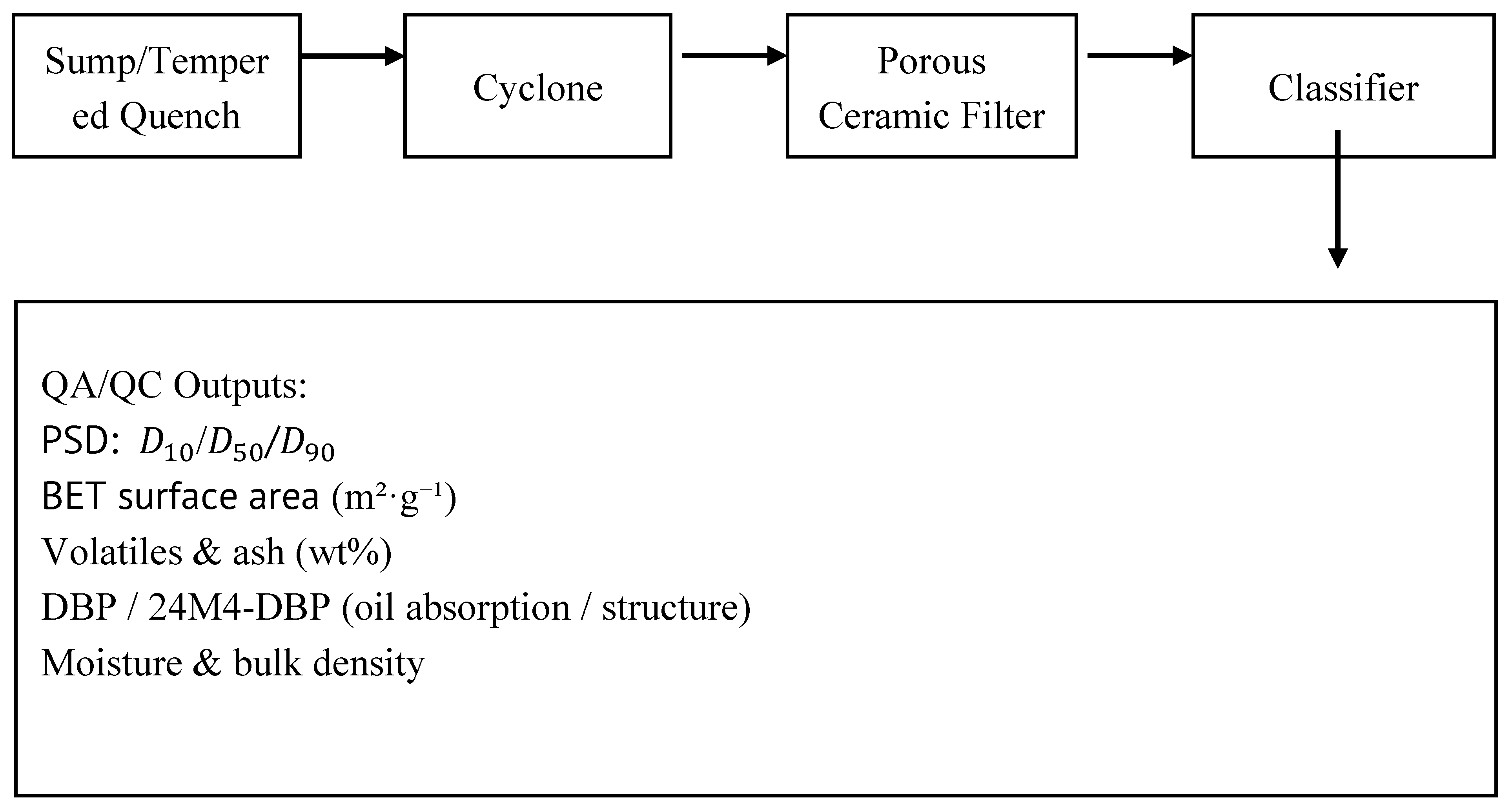

5.3. Carbon QA/QC (Methods That Tie to Economics) (see Fig. 3)

Report the exact analytical methods and sample handling—these drive co-product value.

Minimum QA/QC panel (with methods): (see Fig. 3)

- ▪

PSD: // by laser diffraction (report dispersant, sonication power/time, refractive index model).

- ▪

Surface area: BET (report degassing temp/time, model fit domain).

- ▪

Volatiles & ash: thermogravimetry or muffle procedure and temperatures/hold times; residual metals if relevant.

- ▪

Oil absorption (DBP) or alternative structure metric.

- ▪

Moisture and surface chemistry (if priced): elemental O/H, functional groups (e.g., Boehm titration or XPS).

- ▪

Sample handling: oxygen exposure limits, quench temperature, storage conditions—tie these to the value preservation arguments [

4,

22,

33].

Present a grade-mix table: mass fraction by grade vs. price used in TEA and link each grade to the QA/QC thresholds (see Fig. 3) [

4,

22,

33].

5.4. TEA Inputs (so the Numbers Are Reproducible)

Document parameters and models used for costs and finance; point to raw sources or date-stamped indices.

Costing framework (publish):

- ▪

Equipment costs & scaling: base costs (year & source), scaling exponents, installation factors; method (Bare-Module/Lang) per standard texts [

30,

31,

32].

- ▪

Indices & currencies: cost index used (e.g., CEPCI or equivalent), base year, currency, escalation method.

- ▪

WACC & finance: nominal/real WACC, tax rate, depreciation method (MACRS/SL), plant life nnn, discount rate iii; show CRF:

Figure 3.

Carbon-handling train — sump/tempered quench → cyclone → porous ceramic filter → classifier; QA/QC outputs. (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Carbon-handling train — sump/tempered quench → cyclone → porous ceramic filter → classifier; QA/QC outputs. (see Fig. 3).

- ▪

Operating assumptions: CH₄ price (range), power price & carbon intensity (CI), labor rates, maintenance factor, catalyst/melt makeup, EGS tariff or well O&M [

9,

30,

31,

32,

34].

- ▪

Policy/credit inputs: credit values or carbon price path; eligibility assumptions and allocation method [

7,

8,

9,

27,

29].

Model disclosure: upload the calculation workbook (tabs: Assumptions, Heat Split, CAPEX, OPEX, Revenues, LCOH, Sensitivity) and list equation references (e.g., LCOH definition in §4.4) with cell ranges.

5.5. Data & Code Availability

Provide (i) composite-curve data (.csv), (ii) anonymized TEA workbook, (iii) reactor performance dataset (time-on-stream), and (iv) QA/QC raw outputs. If a site-specific EGS dataset is non-public, include a synthetic but structurally equivalent trace plus bounds so others can rerun Fig. 2 [

21,

26,

34].

6. Conclusions

Geothermal-assisted methane pyrolysis couples a steady, low-carbon heat backbone (EGS) with a high-temperature catalytic conversion that thrives on isothermal stability. The integration:

Reduces electric top-up and exposure to power-price/CI volatility by assigning baseload sensible duty to EGS and keeping electric heat to the last-mile

[

1,

4,

21,

26,

34].

Stabilizes reactor temperatures, mitigating coking/sintering and tightening carbon PSD, which protects separations/compression and preserves carbon-black value [

12,

21,

23,

24,

33].

Enables a dual-product business case (H₂ + CB), with TEA indicating carbon revenue and electric demand as the dominant levers—precisely the levers improved by EGS heat-split [

1,

4,

9,

21,

26,

34].

Scales with HPHT-capable hardware: molten-media columns or fixed/packed beds at 10–25 bar and 600–900 °C, with Fe/Co-rich catalysts favored for robustness and Ni managed for hot-spot/sintering risk [

1,

2,

12,

15,

16,

21,

29,

34].

Immediate path to pilot. (i) Use EGS for preheat/isothermality; (ii) select an HPHT reactor/catalyst pair with proven thermal uniformity; (iii) design the carbon-handling train (sump → cyclone → ceramic filter → classifier) around CB specifications; (iv) structure TEA with transparent CAPEX/OPEX blocks, carbon credits, and carbon co-product revenues. With the curated literature and standard design texts [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34], the concept is sufficiently anchored to proceed to site-specific FEED and pilot demonstration.

References

- S. R. Patlolla, K. Katsu, A. Sharafian, K. Wei, O. E. Herrera, and W. Mérida, “A review of methane pyrolysis technologies for hydrogen production,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 181, p. 113323, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. McConnachie, M. Konarova, and S. Smart, “Literature review of the catalytic pyrolysis of methane for hydrogen and carbon production,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 48, no. 66, pp. 25660–25682, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Lotfollahzade Moghaddam, S. Hejazi, M. Fattahi, M. G. Kibria, M. J. Thomson, R. AlEisa, and M. A. Khan, “Methane pyrolysis for hydrogen production: Navigating the path to a net zero future,” Energy Environ. Sci., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 1034–1056, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Z. Lang, Z. Yanshaozuo, X. Shu, C. Ganming, and D. Huamei, “A mini-review on hydrogen and carbon production from methane pyrolysis by molten media,” Energy Fuels, vol. 38, no. 24, pp. 23175–23191, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Sánchez-Bastardo, R. Schlögl, and H. Ruland, “Methane pyrolysis for CO₂-free hydrogen production: A green process to overcome renewable energies unsteadiness,” Chem. Ing. Tech., vol. 92, no. 10, pp. 1596–1609, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Upham, V. Agarwal, A. Khechfe, Z. R. Snodgrass, M. J. Gordon, H. Metiu, and E. W. McFarland, “Catalytic molten metals for the direct conversion of methane to hydrogen and separable carbon,” Science, vol. 358, no. 6365, pp. 917–921, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. O. Abe, A. P. I. Popoola, E. Ajenifuja, and O. M. Popoola, “Hydrogen energy, economy and storage: Review and recommendation,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 44, no. 29, pp. 15072–15086, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Navas-Anguita, D. García-Gusano, J. Dufour, and D. Iribarren, “Revisiting the role of steam methane reforming with CO₂ capture and storage for long-term hydrogen production,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 771, p. 145432, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Parkinson, J. W. Matthews, J. B. McConnaughy, D. C. Upham, and E. W. McFarland, “Techno-economic analysis of methane pyrolysis in molten metals: Decarbonizing natural gas,” Green Chem., vol. 21, no. 17, pp. 4632–4640, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. I. Korányi, M. Németh, A. Beck, and A. Horváth, “Recent advances in methane pyrolysis: Turquoise hydrogen with solid carbon production,” Energies, vol. 15, no. 17, p. 6342, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Karayel, I. Dincer, and N. Javani, “Green hydrogen production potential in Turkey with wind power,” Int. J. Green Energy, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 129–138, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. F. Patzschke, J. Riemann, K. M. V. Abraham, P. J. Brown, and C. S. Adjiman, “Co-Mn catalysts for H₂ production via methane pyrolysis in molten salts,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 414, p. 128730, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Plevan, T. Geißler, A. Abánades, K. Mehravaran, R. K. Rathnam, C. Rubbia, and D. Salmieri, “Thermal cracking of methane in a liquid metal bubble column reactor: Experiments and kinetic analysis,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 40, no. 25, pp. 8020–8033, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Kang, N. Rahimi, and K. J. Smith, “Catalytic methane pyrolysis in molten MnCl₂-KCl,” Appl. Catal. B: Environ., vol. 254, p. 659, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Meloni, M. Martino, and V. Palma, “A short review on Ni-based catalysts and related engineering issues for methane steam reforming,” Catalysts, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 352, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Punia, L. Prat, and A. Ayache, “Analysis of methane pyrolysis experiments at high pressure: Goal-oriented estimations of kinetics,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 471, p. 144183, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Sorcar and B. A. Rosen, “Methane pyrolysis using a multiphase molten metal reactor,” ACS Catal., vol. 13, no. 15, pp. 10161–10166, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Palmer, A. S. Puckett, A. W. Behn, M. J. Gordon, and E. W. McFarland, “Methane pyrolysis with a molten Cu–Bi alloy catalyst,” ACS Catal., vol. 9, pp. 8337–8345, 2019. [CrossRef]

- U. Pototschnig, P. Yin, M. Sattler, M. C. Korać, and M. Koller, “A predictive model for catalytic methane pyrolysis,” J. Phys. Chem. C, Early Access, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Rosner, T. Bhagde, D. S. Slaughter, V. Zorba, and J. Stokes-Draut, “Techno-economic and carbon dioxide emission assessment of carbon black production,” J. Cleaner Prod., vol. 436, p. 140224, 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Msheik, S. Rodat, E. Villermaux, and S. Abanades, “Experimental comparison of solar methane pyrolysis in gas-phase and molten-tin bubbling tubular reactors,” Energy, vol. 260, p. 124943, 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. Daghagheleh, H. B. Karimipour, and M. H. Sarrafzadeh, “Feasibility of a plasma furnace for methane pyrolysis,” Energies, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 167, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Uehara, K. Takao, S. Sato, and Y. Takeno, “CO₂-free hydrogen production by methane pyrolysis using hydrogen combustion heat,” Energies, vol. 17, no. 2, p. 367, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, Y. Wang, B. Wang, X. Su, and F. Wang, “The secondary flows in a cyclone separator: A review,” Processes, vol. 11, p. 2935, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. R. G. Pangestu and U. Zahid, “Techno-economic analysis of integrating methane pyrolysis and reforming for low-carbon ammonia production,” Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 322, p. 119125, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Aljubran, A. G. Gandomi, A. Al-Aali, and H. A. Al-Khalidi, “Power supply characterization of baseload and flexible enhanced geothermal systems,” Sci. Rep., 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Sánchez-Bastardo, R. Schlögl, and H. Ruland, “Methane pyrolysis for zero-emission hydrogen production,” Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., vol. 60, no. 34, pp. 11855–11881, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim, H. Kim, S. Kim, S. Lee, and J. Kim, “Hydrogen production in methane decomposition reactor using solar thermal energy,” Appl. Sci., vol. 11, no. 21, p. 10333, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. DiPippo, Geothermal Power Plants: Principles, Applications, Case Studies and Environmental Impact, 4th ed. Oxford, U.K.: Butterworth–Heinemann (Elsevier), 2015.

- G. Towler and R. K. Sinnott, Chemical Engineering Design: Principles, Practice and Economics of Plant and Process Design, 3rd ed. Oxford, U.K.: Elsevier, 2022.

- D. W. Green and M. Z. Southard (eds.), Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook, 9th ed. New York, NY, USA: McGraw–Hill, 2019.

- M. S. Peters, K. D. Timmerhaus, and R. E. West, Plant Design and Economics for Chemical Engineers, 5th ed. New York, NY, USA: McGraw–Hill, 2003.

- J.-B. Donnet, R. C. Bansal, and M.-J. Wang, Carbon Black: Science and Technology, 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Marcel Dekker, 1993.

- M. Grant and P. Bixley, Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, 2nd ed. Burlington, MA, USA: Academic Press, 2011.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Figure 2. Pinch-style heat map — match highest ṁcₚ streams to EGS; ΔTmin and residual trim-heat ΔT annotated.Figure 2. Pinch-style heat map — match highest ṁcₚ streams to EGS; ΔTmin and residual trim-heat ΔT annotated.

Figure 2. Pinch-style heat map — match highest ṁcₚ streams to EGS; ΔTmin and residual trim-heat ΔT annotated.Figure 2. Pinch-style heat map — match highest ṁcₚ streams to EGS; ΔTmin and residual trim-heat ΔT annotated.