Submitted:

07 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

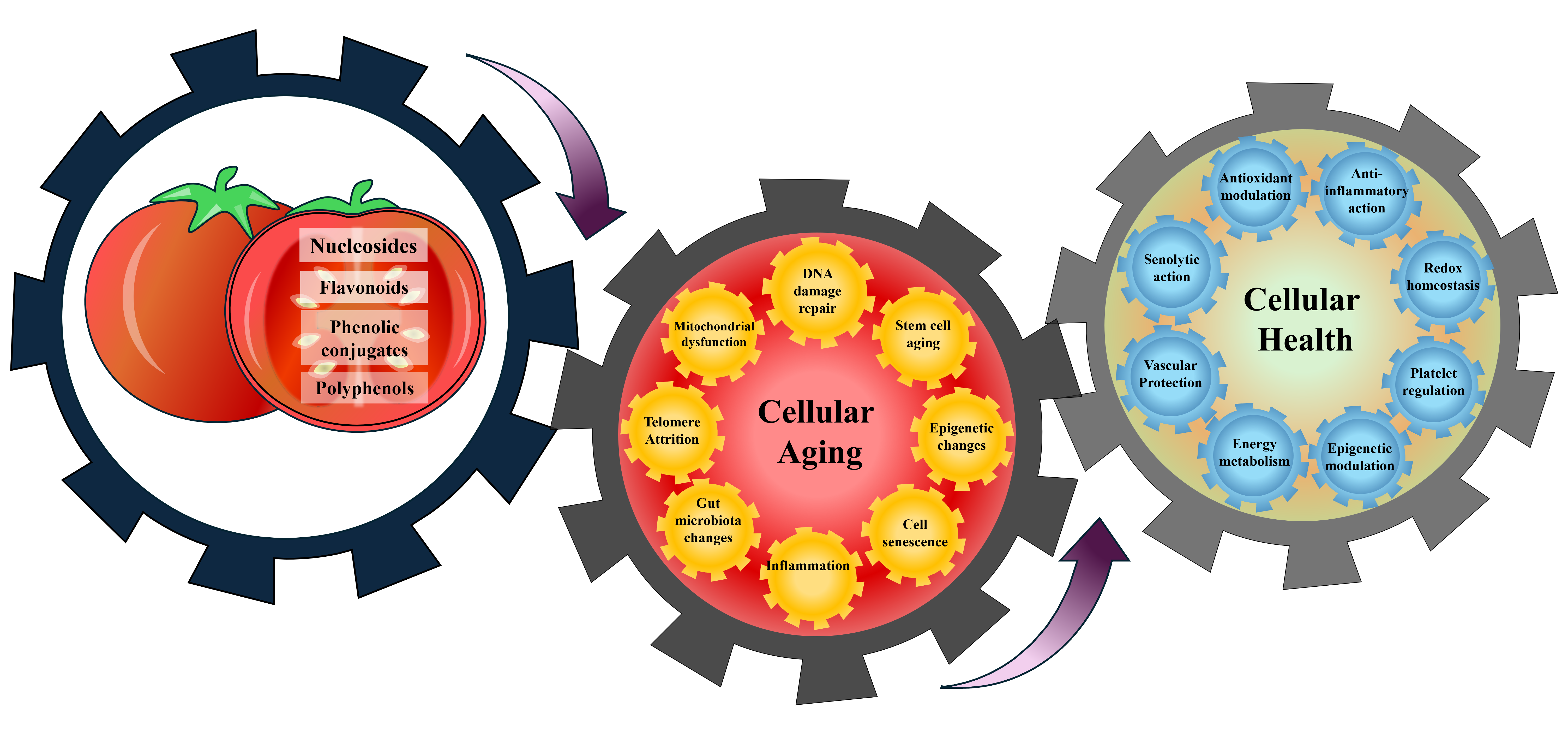

2. Fruitflow® and the Dietary–Molecular Interplay in Aging

2.1. Dietary Bioactive Compounds of Fruitflow® and Telomere Attrition

2.2. Modulatory Effects of Fruitflow® on Oxidative DNA Damage and Repair Pathways:

2.3. Countering Diet- and Age-Related Mitochondrial Stress with Fruitflow®

2.4. Role of Rutin, Quercetin, and CGA in Modulating Senescence and SASP-Related Aging

2.5. Cell Proliferation, Ageing and Fruitflow®

2.6. Fruitflow® Constituents in Regulating Cell Proliferation and Tissue Regeneration

2.7. Cell cycle, Oxidative Stress, and Fruitflow®

2.8. Age-Related Platelet Hyperactivity and Fruitflow®

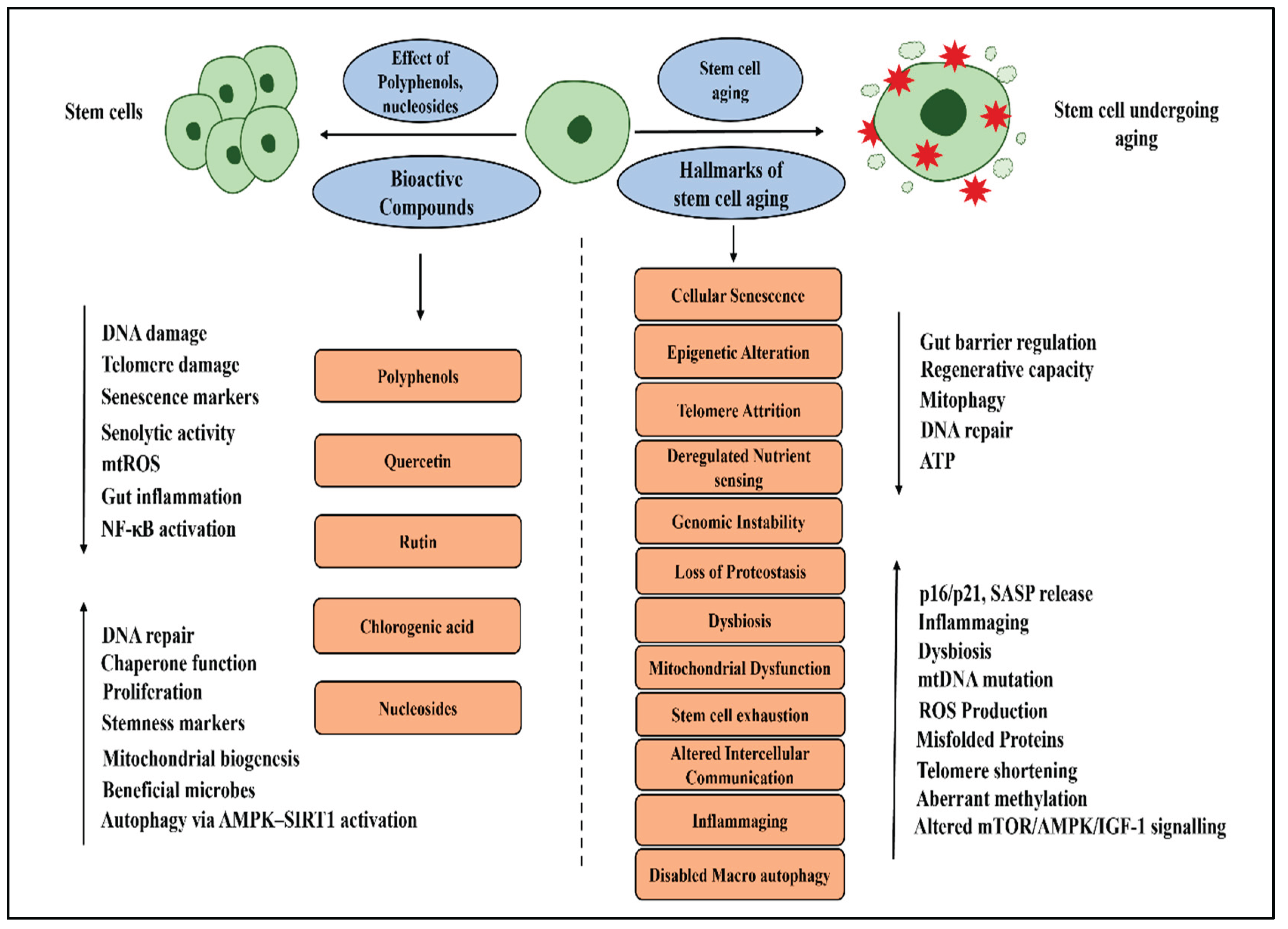

3. Modulatory Role of Fruitflow® in Stem Cell Aging

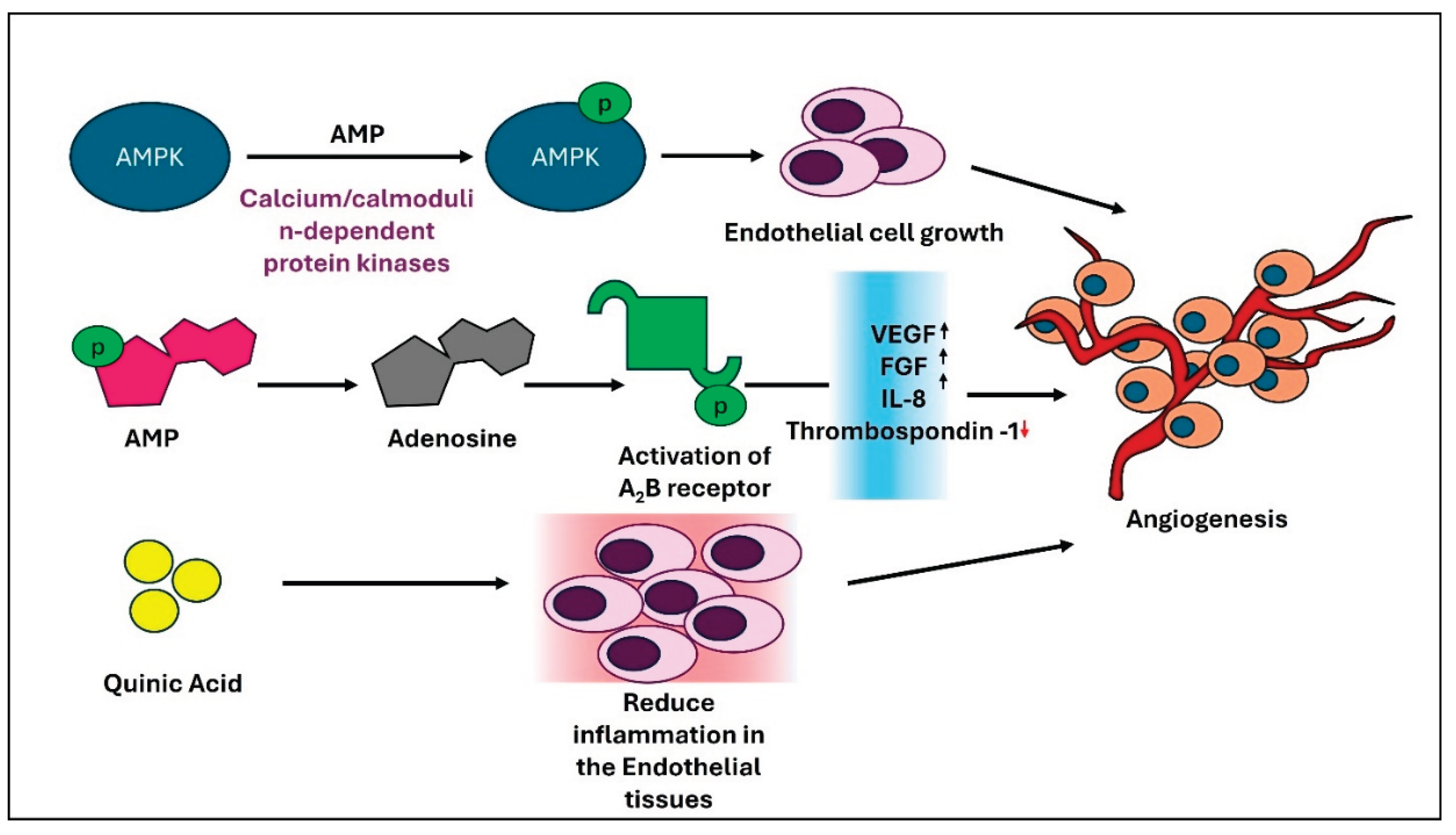

4. Regulation of Angiogenesis in the Context of Aging: Effects of Bioactive Compounds of Fruitflow®

5. Epigenetic Regulation of Bioactive Compounds of Fruitflow® in Aging

6. Gut Microbiota, Aging, and Fruitflow®

7. Conclusion and Future Perspective:

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Vijg, J.; Dong, X. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Somatic Mutation and Genome Mosaicism in Aging. Cell 2020, 182, 12–23. [CrossRef]

- Navarro Negredo, P.; Yeo, R.W.; Brunet, A. Aging and Rejuvenation of Neural Stem Cells and Their Niches. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27, 202–223. [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of Aging: An Expanding Universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka, E.; Napierała, P.; Podfigurna, A.; Męczekalski, B.; Smolarczyk, R.; Grymowicz, M. The World Health Organization (WHO) Approach to Healthy Ageing. Maturitas 2020, 139, 6–11. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, B.K.; Berger, S.L.; Brunet, A.; Campisi, J.; Cuervo, A.M.; Epel, E.S.; Franceschi, C.; Lithgow, G.J.; Morimoto, R.I.; Pessin, J.E.; et al. Geroscience: Linking Aging to Chronic Disease. Cell 2014, 159, 709–713. [CrossRef]

- Cory, H.; Passarelli, S.; Szeto, J.; Tamez, M.; Mattei, J. The Role of Polyphenols in Human Health and Food Systems: A Mini-Review. Front Nutr 2018, 5. [CrossRef]

- Baur, J.A.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic Potential of Resveratrol: The in Vivo Evidence. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006, 5, 493–506. [CrossRef]

- Vauzour, D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Corona, G.; Oruna-Concha, M.J.; Spencer, J.P.E. Polyphenols and Human Health: Prevention of Disease and Mechanisms of Action. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1106–1131. [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Tognolini, M.; Borges, G.; Crozier, A. Dietary (Poly)Phenolics in Human Health: Structures, Bioavailability, and Evidence of Protective Effects Against Chronic Diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013, 18, 1818–1892. [CrossRef]

- Diwan, B.; Sharma, R. Nutritional Components as Mitigators of Cellular Senescence in Organismal Aging: A Comprehensive Review. Food Sci Biotechnol 2022, 31, 1089–1109. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Hickson, L.J.; Eirin, A.; Kirkland, J.L.; Lerman, L.O. Cellular Senescence: The Good, the Bad and the Unknown. Nat Rev Nephrol 2022, 18, 611–627. [CrossRef]

- Meirow, Y.; Baniyash, M. Immune Biomarkers for Chronic Inflammation Related Complications in Non-Cancerous and Cancerous Diseases. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 2017, 66, 1089–1101. [CrossRef]

- Fekete, M.; Szarvas, Z.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Feher, A.; Csipo, T.; Forrai, J.; Dosa, N.; Peterfi, A.; Lehoczki, A.; Tarantini, S.; et al. Nutrition Strategies Promoting Healthy Aging: From Improvement of Cardiovascular and Brain Health to Prevention of Age-Associated Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 15, 47. [CrossRef]

- AlAli, M.; Alqubaisy, M.; Aljaafari, M.N.; AlAli, A.O.; Baqais, L.; Molouki, A.; Abushelaibi, A.; Lai, K.-S.; Lim, S.-H.E. Nutraceuticals: Transformation of Conventional Foods into Health Promoters/Disease Preventers and Safety Considerations. Molecules 2021, 26, 2540. [CrossRef]

- O’Kennedy, N.; Raederstorff, D.; Duttaroy, A.K. Fruitflow®: The First European Food Safety Authority-Approved Natural Cardio-Protective Functional Ingredient. Eur J Nutr 2017, 56, 461–482. [CrossRef]

- Das, R.K.; Datta, T.; Biswas, D.; Duss, R.; O’Kennedy, N.; Duttaroy, A.K. Evaluation of the Equivalence of Different Intakes of Fruitflow in Affecting Platelet Aggregation and Thrombin Generation Capacity in a Randomized, Double-Blinded Pilot Study in Male Subjects. BMC Nutr 2021, 7, 80. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Biswas, D.; Ghosh, A.; O’Kennedy, N.; Duttaroy, A.K. Consumption of Fruitflow ® Lowers Blood Pressure in Pre-Hypertensive Males: A Randomised, Placebo Controlled, Double Blind, Cross-over Study. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2018, 69, 494–502. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D.; Uddin, Md.M.; Dizdarevic, L.L.; Jørgensen, A.; Duttaroy, A.K. Inhibition of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme by Aqueous Extract of Tomato. Eur J Nutr 2014, 53, 1699–1706. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Bao, L.; Wu, W.; Qi, R. Fruitflow Inhibits Platelet Function by Suppressing Akt/GSK3β, Syk/PLCγ2 and P38 MAPK Phosphorylation in Collagen-Stimulated Platelets. BMC Complement Med Ther 2022, 22, 75. [CrossRef]

- Duttaroy, A.K. Functional Foods in Preventing Human Blood Platelet Hyperactivity-Mediated Diseases—An Updated Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3717. [CrossRef]

- Somasundaram, I.; Jain, S.M.; Blot-Chabaud, M.; Pathak, S.; Banerjee, A.; Rawat, S.; Sharma, N.R.; Duttaroy, A.K. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Its Association with Age-Related Disorders. Front Physiol 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Li, K.; Fan, D.; Gao, X.; Ma, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, D.; Liang, Y.; Ji, Q.; Chen, Y.; et al. Water-Soluble Tomato Concentrate, a Potential Antioxidant Supplement, Can Attenuate Platelet Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in Healthy Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Crossover Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3374. [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Adhikary, S.; Das, R.K.; Banerjee, A.; Radhakrishnan, A.K.; Paul, S.; Pathak, S.; Duttaroy, A.K. Bioactive Food Components and Their Inhibitory Actions in Multiple Platelet Pathways. J Food Biochem 2022, 46. [CrossRef]

- Keefe, D.L. Telomeres and Genomic Instability during Early Development. Eur J Med Genet 2020, 63, 103638. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.E.; Coody, T.K.; Jeong, M.-Y.; Berg, J.A.; Winge, D.R.; Hughes, A.L. Cysteine Toxicity Drives Age-Related Mitochondrial Decline by Altering Iron Homeostasis. Cell 2020, 180, 296-310.e18. [CrossRef]

- Heintz, C.; Doktor, T.K.; Lanjuin, A.; Escoubas, C.C.; Zhang, Y.; Weir, H.J.; Dutta, S.; Silva-García, C.G.; Bruun, G.H.; Morantte, I.; et al. Splicing Factor 1 Modulates Dietary Restriction and TORC1 Pathway Longevity in C. Elegans. Nature 2017, 541, 102–106. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Karpac, J.; Tran, S.L.; Jasper, H. PGRP-SC2 Promotes Gut Immune Homeostasis to Limit Commensal Dysbiosis and Extend Lifespan. Cell 2014, 156, 109–122. [CrossRef]

- Pousa, P.A.; Souza, R.M.; Melo, P.H.M.; Correa, B.H.M.; Mendonça, T.S.C.; Simões-e-Silva, A.C.; Miranda, D.M. Telomere Shortening and Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review. Cells 2021, 10, 1423. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tian, X.; Luo, J.; Bao, T.; Wang, S.; Wu, X. Molecular Mechanisms of Aging and Anti-Aging Strategies. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 285. [CrossRef]

- Galiè, S.; Canudas, S.; Muralidharan, J.; García-Gavilán, J.; Bulló, M.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Impact of Nutrition on Telomere Health: Systematic Review of Observational Cohort Studies and Randomized Clinical Trials. Advances in Nutrition 2020, 11, 576–601. [CrossRef]

- Kark, J.D.; Goldberger, N.; Kimura, M.; Sinnreich, R.; Aviv, A. Energy Intake and Leukocyte Telomere Length in Young Adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2012, 95, 479–487. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Jana, J.; Sengupta, P.; Jana, S.; Chatterjee, S. Myricetin Arrests Human Telomeric G-Quadruplex Structure: A New Mechanistic Approach as an Anticancer Agent. Mol Biosyst 2016, 12, 2506–2518. [CrossRef]

- Parekh, N.; Garg, A.; Choudhary, R.; Gupta, M.; Kaur, G.; Ramniwas, S.; Shahwan, M.; Tuli, H.S.; Sethi, G. The Role of Natural Flavonoids as Telomerase Inhibitors in Suppressing Cancer Growth. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 605. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.; Wang, Y.-J.; Zhong, J.-H.; Kosaraju, S.; O’Callaghan, N.J.; Zhou, X.-F.; Fenech, M. Grape Seed Polyphenols and Curcumin Reduce Genomic Instability Events in a Transgenic Mouse Model for Alzheimer’s Disease. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2009, 661, 25–34. [CrossRef]

- Sorrenti, V.; Ali, S.; Mancin, L.; Davinelli, S.; Paoli, A.; Scapagnini, G. Cocoa Polyphenols and Gut Microbiota Interplay: Bioavailability, Prebiotic Effect, and Impact on Human Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1908. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Honig, L.S.; Schupf, N.; Lee, J.H.; Luchsinger, J.A.; Stern, Y.; Scarmeas, N. Mediterranean Diet and Leukocyte Telomere Length in a Multi-Ethnic Elderly Population. Age (Omaha) 2015, 37, 24. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Tyree, S.M.; Fehlbaum, S.; DunnGalvin, G.; Panagos, C.G.; Guy, B.; Patel, S.; Dinan, T.G.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Duss, R.; et al. A Water-Soluble Tomato Extract Rich in Secondary Plant Metabolites Lowers Trimethylamine-n-Oxide and Modulates Gut Microbiota: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Cross-over Study in Overweight and Obese Adults. J Nutr 2023, 153, 96–105. [CrossRef]

- García-Calzón, S.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Razquin, C.; Arós, F.; Lapetra, J.; Martínez, J.A.; Zalba, G.; Marti, A. Mediterranean Diet and Telomere Length in High Cardiovascular Risk Subjects from the PREDIMED-NAVARRA Study. Clinical Nutrition 2016, 35, 1399–1405. [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.W.; Fung, T.T.; McEvoy, C.T.; Lin, J.; Epel, E.S. Diet Quality Indices and Leukocyte Telomere Length Among Healthy US Adults: Data From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2002. Am J Epidemiol 2018, 187, 2192–2201. [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.-Y.; Armanios, M.; Strong, M.A.; Karim, B.; Feldser, D.M.; Huso, D.; Greider, C.W. Short Telomeres, Even in the Presence of Telomerase, Limit Tissue Renewal Capacity. Cell 2005, 123, 1121–1131. [CrossRef]

- Gorbunova, V.; Seluanov, A.; Mita, P.; McKerrow, W.; Fenyö, D.; Boeke, J.D.; Linker, S.B.; Gage, F.H.; Kreiling, J.A.; Petrashen, A.P.; et al. The Role of Retrotransposable Elements in Ageing and Age-Associated Diseases. Nature 2021, 596, 43–53. [CrossRef]

- Coluzzi, E.; Leone, S.; Sgura, A. Oxidative Stress Induces Telomere Dysfunction and Senescence by Replication Fork Arrest. Cells 2019, 8, 19. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M.; Parvez, S.; Agrawala, P.K. Role of Some Epigenetic Factors in DNA Damage Response Pathway. AIMS Genet 2017, 04, 069–083. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Fu, Y.; He, C. Nucleic Acid Oxidation in DNA Damage Repair and Epigenetics. Chem Rev 2014, 114, 4602–4620. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.; O’Leary, C.; O’Byrne, K.J.; Burgess, J.; Richard, D.J.; Suraweera, A. Epigenetic Mechanisms in DNA Double Strand Break Repair: A Clinical Review. Front Mol Biosci 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Jones, K.; Burke, T.J.; Hossain, M.A.; Lariscy, L. Epigenetic Regulation of Nucleotide Excision Repair. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Sarkar, A.; Das, D.; Sengupta, A.; Kabiraj, A.; Mondal, P.; Nag, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Das, C. Epigenetic Orchestration of the DNA Damage Response: Insights into the Regulatory Mechanisms. In; 2024; pp. 99–141.

- Lin, X.; Kapoor, A.; Gu, Y.; Chow, M.J.; Peng, J.; Zhao, K.; Tang, D. Contributions of DNA Damage to Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1666. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.C.; Singh, K.K.; Yanagawa, B.; Teoh, H.; Verma, S. DNA Damage Repair and Cardiovascular Diseases. Can J Cardiol 2010, 26 Suppl A, 13A-16A. [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M.; Rakshit, G.; Singh, R.P.; Garse, S.; Khan, J.; Chakraborty, S. Dietary Polyphenols: Review on Chemistry/Sources, Bioavailability/Metabolism, Antioxidant Effects, and Their Role in Disease Management. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 429. [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M.; Khairnar, S.J.; Khan, J.; Dukhyil, A. Bin; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Palai, S.; Deb, P.K.; Devi, R. Dietary Polyphenols and Their Role in Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: Insights Into Protective Effects, Antioxidant Potentials and Mechanism(s) of Action. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.-L.; Jeong, W.-S. Cellular Defensive Mechanisms of Tea Polyphenols: Structure-Activity Relationship. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 9109. [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.M.; Burrows, C.J. On the Irrelevancy of Hydroxyl Radical to DNA Damage from Oxidative Stress and Implications for Epigenetics. Chem Soc Rev 2020, 49, 6524–6528. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2345. [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Toxicity, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Chronic Diseases and Aging. Arch Toxicol 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [CrossRef]

- Darband, S.G.; Sadighparvar, S.; Yousefi, B.; Kaviani, M.; Ghaderi-Pakdel, F.; Mihanfar, A.; Rahimi, Y.; Mobaraki, K.; Majidinia, M. Quercetin Attenuated Oxidative DNA Damage through NRF2 Signaling Pathway in Rats with DMH Induced Colon Carcinogenesis. Life Sci 2020, 253, 117584. [CrossRef]

- Weindel, C.G.; Martinez, E.L.; Zhao, X.; Mabry, C.J.; Bell, S.L.; Vail, K.J.; Coleman, A.K.; VanPortfliet, J.J.; Zhao, B.; Wagner, A.R.; et al. Mitochondrial ROS Promotes Susceptibility to Infection via Gasdermin D-Mediated Necroptosis. Cell 2022, 185, 3214-3231.e23. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Li, X.; Tian, Y. Mitochondrial-to-Nuclear Communication in Aging: An Epigenetic Perspective. Trends Biochem Sci 2022, 47, 645–659. [CrossRef]

- Traba, J.; Satrústegui, J.; del Arco, A. Transport of Adenine Nucleotides in the Mitochondria of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae: Interactions between the ADP/ATP Carriers and the ATP-Mg/Pi Carrier. Mitochondrion 2009, 9, 79–85. [CrossRef]

- Alfatni, A.; Riou, M.; Charles, A.-L.; Meyer, A.; Barnig, C.; Andres, E.; Lejay, A.; Talha, S.; Geny, B. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells and Platelets Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Circulating MtDNA in Cardiovascular Diseases. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 311. [CrossRef]

- Mottis, A.; Herzig, S.; Auwerx, J. Mitocellular Communication: Shaping Health and Disease. Science (1979) 2019, 366, 827–832. [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.; Li, T.Y.; Mottis, A.; Auwerx, J. Pleiotropic Effects of Mitochondria in Aging. Nat Aging 2022, 2, 199–213. [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, B.; Pothof, J.; Vijg, J.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.J. The Central Role of DNA Damage in the Ageing Process. Nature 2021, 592, 695–703. [CrossRef]

- Furlan, L.; Catala, A. Lipid Modifications of Microsomes Isolated from Villus and Crypt Zones of Bovine Intestinal Mucosa: Relationship with Fatty Acid Binding Protein. Arch Physiol Biochem 1997, 105, 86–91. [CrossRef]

- Belenky, P.; Bogan, K.L.; Brenner, C. NAD+ Metabolism in Health and Disease. Trends Biochem Sci 2007, 32, 12–19. [CrossRef]

- Gerner, R.R.; Klepsch, V.; Macheiner, S.; Arnhard, K.; Adolph, T.E.; Grander, C.; Wieser, V.; Pfister, A.; Moser, P.; Hermann-Kleiter, N.; et al. NAD Metabolism Fuels Human and Mouse Intestinal Inflammation. Gut 2018, 67, 1813–1823. [CrossRef]

- Kyriazis, I.; Vassi, E.; Alvanou, M.; Angelakis, C.; Skaperda, Z.; Tekos, F.; Garikipati, V.; Spandidos, D.; Kouretas, D. The Impact of Diet upon Mitochondrial Physiology (Review). Int J Mol Med 2022, 50, 135. [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Shruthi, N.R.; Banerjee, A.; Jothimani, G.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Pathak, S. Endothelial Dysfunction, Platelet Hyperactivity, Hypertension, and the Metabolic Syndrome: Molecular Insights and Combating Strategies. Front Nutr 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Jothimani, G.; Banerjee, A.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Pathak, S. The Cardioprotective Effects of Fruitflow® against Doxorubicin-Induced Toxicity in Rat Cardiomyoblast Cells H9c2 (2−1) and High-Fat Diet-Induced Dyslipidemia and Pathological Alteration in Cardiac Tissue of Wistar Albino Rats. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 180, 117607. [CrossRef]

- Degirmenci, U.; Lei, S. Role of LncRNAs in Cellular Aging. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Gasek, N.S.; Kuchel, G.A.; Kirkland, J.L.; Xu, M. Strategies for Targeting Senescent Cells in Human Disease. Nat Aging 2021, 1, 870–879. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.L.; Rowe, J.H.; Garcia-de-Alba, C.; Kim, C.F.; Sharpe, A.H.; Haigis, M.C. The Aging Lung: Physiology, Disease, and Immunity. Cell 2021, 184, 1990–2019. [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Zhang, L.; Gao, W.; Huang, C.; Huber, P.E.; Zhou, X.; Li, C.; Shen, G.; Zou, B. NAD+ Metabolism: Pathophysiologic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5, 227. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.B.; Sinclair, D.A. When Stem Cells Grow Old: Phenotypes and Mechanisms of Stem Cell Aging. Development 2016, 143, 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Bigot, A.; Duddy, W.J.; Ouandaogo, Z.G.; Negroni, E.; Mariot, V.; Ghimbovschi, S.; Harmon, B.; Wielgosik, A.; Loiseau, C.; Devaney, J.; et al. Age-Associated Methylation Suppresses SPRY1 , Leading to a Failure of Re-Quiescence and Loss of the Reserve Stem Cell Pool in Elderly Muscle. Cell Rep 2015, 13, 1172–1182. [CrossRef]

- Lukjanenko, L.; Karaz, S.; Stuelsatz, P.; Gurriaran-Rodriguez, U.; Michaud, J.; Dammone, G.; Sizzano, F.; Mashinchian, O.; Ancel, S.; Migliavacca, E.; et al. Aging Disrupts Muscle Stem Cell Function by Impairing Matricellular WISP1 Secretion from Fibro-Adipogenic Progenitors. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 24, 433-446.e7. [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.J.; Childs, B.G.; Durik, M.; Wijers, M.E.; Sieben, C.J.; Zhong, J.; A. Saltness, R.; Jeganathan, K.B.; Verzosa, G.C.; Pezeshki, A.; et al. Naturally Occurring P16Ink4a-Positive Cells Shorten Healthy Lifespan. Nature 2016, 530, 184–189. [CrossRef]

- Calubag, M.F.; Robbins, P.D.; Lamming, D.W. A Nutrigeroscience Approach: Dietary Macronutrients and Cellular Senescence. Cell Metab 2024, 36, 1914–1944. [CrossRef]

- Della Vedova, L.; Baron, G.; Morazzoni, P.; Aldini, G.; Gado, F. The Potential of Polyphenols in Modulating the Cellular Senescence Process: Implications and Mechanism of Action. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 138. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhou, M.; Ge, Y.; Wang, X. SIRT1 and Aging Related Signaling Pathways. Mech Ageing Dev 2020, 187, 111215. [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Pan, Y. Influence of Food Matrix and Food Processing on the Chemical Interaction and Bioaccessibility of Dietary Phytochemicals: A Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 6421–6445. [CrossRef]

- De Luca, F.; Gola, F.; Azzalin, A.; Casali, C.; Gaiaschi, L.; Milanesi, G.; Vicini, R.; Rossi, P.; Bottone, M.G. A Lombard Variety of Sweet Pepper Regulating Senescence and Proliferation: The Voghera Pepper. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1681. [CrossRef]

- Della Vedova, L.; Baron, G.; Morazzoni, P.; Aldini, G.; Gado, F. The Potential of Polyphenols in Modulating the Cellular Senescence Process: Implications and Mechanism of Action. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 138. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xu, Q.; Wufuer, H.; Li, Z.; Sun, R.; Jiang, Z.; Dou, X.; Fu, Q.; Campisi, J.; Sun, Y. Rutin Is a Potent Senomorphic Agent to Target Senescent Cells and Can Improve Chemotherapeutic Efficacy. Aging Cell 2024, 23. [CrossRef]

- Hada, Y.; Uchida, H.A.; Otaka, N.; Onishi, Y.; Okamoto, S.; Nishiwaki, M.; Takemoto, R.; Takeuchi, H.; Wada, J. The Protective Effect of Chlorogenic Acid on Vascular Senescence via the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 4527. [CrossRef]

- Zoico, E.; Nori, N.; Darra, E.; Tebon, M.; Rizzatti, V.; Policastro, G.; De Caro, A.; Rossi, A.P.; Fantin, F.; Zamboni, M. Senolytic Effects of Quercetin in an in Vitro Model of Pre-Adipocytes and Adipocytes Induced Senescence. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 23237. [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Xiang, L.; Xiao, L. Quercetin Alleviates Atherosclerosis by Suppressing Oxidized LDL-Induced Senescence in Plaque Macrophage via Inhibiting the P38MAPK/P16 Pathway. J Nutr Biochem 2023, 116, 109314. [CrossRef]

- Ragonnaud, E.; Biragyn, A. Gut Microbiota as the Key Controllers of “Healthy” Aging of Elderly People. Immunity & Ageing 2021, 18, 2. [CrossRef]

- Hoyles, L.; Jiménez-Pranteda, M.L.; Chilloux, J.; Brial, F.; Myridakis, A.; Aranias, T.; Magnan, C.; Gibson, G.R.; Sanderson, J.D.; Nicholson, J.K.; et al. Metabolic Retroconversion of Trimethylamine N-Oxide and the Gut Microbiota. Microbiome 2018, 6, 73. [CrossRef]

- Viola, J.; Soehnlein, O. Atherosclerosis – A Matter of Unresolved Inflammation. Semin Immunol 2015, 27, 184–193. [CrossRef]

- Landi, A.; Schoenhuber, R.; Funicello, R.; Rasio, G.; Esposito, M. Compartment Syndrome of the Scapula. Definition on Clinical, Neurophysiological and Magnetic Resonance Data. Ann Chir Main Memb Super 1992, 11, 383–388. [CrossRef]

- Raiola, A.; Rigano, M.M.; Calafiore, R.; Frusciante, L.; Barone, A. Enhancing the Health-Promoting Effects of Tomato Fruit for Biofortified Food. Mediators Inflamm 2014, 2014, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Rayes, J.; Jenne, C.N. Platelets: Bridging Thrombosis and Inflammation. Platelets 2021, 32, 293–294. [CrossRef]

- Lievens, D.; Hundelshausen, P. von Platelets in Atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost 2011, 106, 827–838. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wernly, B.; Cao, X.; Mustafa, S.J.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, Z. Adenosine and Adenosine Receptor-Mediated Action in Coronary Microcirculation. Basic Res Cardiol 2021, 116, 22. [CrossRef]

- Porkka-Heiskanen, T.; Kalinchuk, A. V. Adenosine, Energy Metabolism and Sleep Homeostasis. Sleep Med Rev 2011, 15, 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Meininger, C.J.; Schelling, M.E.; Granger, H.J. Adenosine and Hypoxia Stimulate Proliferation and Migration of Endothelial Cells. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 1988, 255, H554–H562. [CrossRef]

- Ugusman, A.; Zakaria, Z.; Chua, K.H.; Megat Mohd Nordin, N.A.; Abdullah Mahdy, Z. Role of Rutin on Nitric Oxide Synthesis in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. The Scientific World Journal 2014, 2014, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.G. de L.; de Oliveira, H.P. β-Cyclodextrin-Silver Nanoparticles Inclusion Complexes: Insights into Applications in Trace Level Detection (Light-Driven and Electrochemical Assays) and Antibacterial Activity. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 23943–23956. [CrossRef]

- Satari, A.; Ghasemi, S.; Habtemariam, S.; Asgharian, S.; Lorigooini, Z. Rutin: A Flavonoid as an Effective Sensitizer for Anticancer Therapy; Insights into Multifaceted Mechanisms and Applicability for Combination Therapy. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2021, 2021, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Nouri, Z.; Fakhri, S.; Nouri, K.; Wallace, C.E.; Farzaei, M.H.; Bishayee, A. Targeting Multiple Signaling Pathways in Cancer: The Rutin Therapeutic Approach. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 2276. [CrossRef]

- Zong, M.; Ji, J.; Wang, Q.; Cai, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Hou, W.; Li, X.; Kong, Q.; Zheng, C.; et al. Chlorogenic Acid Promotes Fatty Acid Beta-Oxidation to Increase HESCs Proliferation and Lipid Synthesis. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 7095. [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Cheng, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, W.; Li, B.; Fu, Y.; Wang, X.; Liao, C.; Chen, Y.; Yan, J. Chlorogenic Acid Alleviates Deoxynivalenol-Induced Damage in Porcine Trophectoderm Cells by Regulating the PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway. Biol Reprod 2025, 113, 466–477. [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, S.; Alarcón, M.; Palomo, I. Aqueous Extract of Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) and Ferulic Acid Reduce the Expression of TNF-α and IL-1β in LPS-Activated Macrophages. Molecules 2015, 20, 15319–15329. [CrossRef]

- Schwager, J.; Richard, N.; Mussler, B.; Raederstorff, D. Tomato Aqueous Extract Modulates the Inflammatory Profile of Immune Cells and Endothelial Cells. Molecules 2016, 21, 168. [CrossRef]

- Rayes, J.; Jenne, C.N. Platelets: Bridging Thrombosis and Inflammation. Platelets 2021, 32, 293–294. [CrossRef]

- Lievens, D.; Hundelshausen, P. von Platelets in Atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost 2011, 106, 827–838. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, F.; Palomo, I.; Fuentes, E. Platelet Oxidative Stress as a Novel Target of Cardiovascular Risk in Frail Older People. Vascul Pharmacol 2017, 93–95, 14–19. [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.Y.; Min, J.H.; Chae, Y.H.; Baek, J.Y.; Wang, S. Bin; Park, S.J.; Oh, G.T.; Lee, S.-H.; Ho, Y.-S.; Chang, T.-S. Reactive Oxygen Species Play a Critical Role in Collagen-Induced Platelet Activation via SHP-2 Oxidation. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014, 20, 2528–2540. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Q.C.; dos Santos, T.W.; Fortunato, I.M.; Ribeiro, M.L. The Molecular Mechanism of Polyphenols in the Regulation of Ageing Hallmarks. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 5508. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, M.; Tu, X.; Mo, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, B.; Wang, F.; Kim, Y.-B.; Huang, C.; Chen, L.; et al. Dietary Polyphenols as Anti-Aging Agents: Targeting the Hallmarks of Aging. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3305. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Fang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lin, P.; Wan, B.; Wang, M.; Deng, L.; Tang, X. Dietary Flavonoid Intake Is Negatively Associated with Accelerating Aging: An American Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Nutr J 2024, 23, 158. [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, S. Diet and Aging: The Role of Polyphenol-Rich Diets in Slow Down the Shortening of Telomeres: A Review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2086. [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.R.; Madiwale, S. V.; Saini, D.K. Clampdown of Inflammation in Aging and Anticancer Therapies by Limiting Upregulation and Activation of GPCR, CXCR4. NPJ Aging Mech Dis 2018, 4, 9. [CrossRef]

- Pallauf, K.; Rimbach, G. Autophagy, Polyphenols and Healthy Ageing. Ageing Res Rev 2013, 12, 237–252. [CrossRef]

- Wedel, S.; Manola, M.; Cavinato, M.; Trougakos, I.P.; Jansen-Dürr, P. Targeting Protein Quality Control Mechanisms by Natural Products to Promote Healthy Ageing. Molecules 2018, 23, 1219. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Luo, Y.; Yin, J.; Huang, M.; Luo, F. Targeting AMPK Signaling by Polyphenols: A Novel Strategy for Tackling Aging. Food Funct 2023, 14, 56–73. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Acuña, C.; Ferreira, J.; Speisky, H. Polyphenols and Mitochondria: An Update on Their Increasingly Emerging ROS-Scavenging Independent Actions. Arch Biochem Biophys 2014, 559, 75–90. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.E.; Wilgus, T.A. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Angiogenesis in the Regulation of Cutaneous Wound Repair. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2014, 3, 647–661. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, M.-J.; Kumar, A.; Lee, H.-W.; Yang, Y.; Kim, Y. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Signaling in Health and Disease: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Perspectives. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025, 10, 170. [CrossRef]

- Callahan, C.M.; Apostolova, L.G.; Gao, S.; Risacher, S.L.; Case, J.; Saykin, A.J.; Lane, K.A.; Swinford, C.G.; Yoder, M.C. Novel Markers of Angiogenesis in the Setting of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2020, 75, 959–969. [CrossRef]

- Damluji, A.A.; Alfaraidhy, M.; AlHajri, N.; Rohant, N.N.; Kumar, M.; Al Malouf, C.; Bahrainy, S.; Ji Kwak, M.; Batchelor, W.B.; Forman, D.E.; et al. Sarcopenia and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circulation 2023, 147, 1534–1553. [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, C.; Oprea, B.; Ciobanu, G.; Georgescu, M.; Bică, R.; Mateescu, G.-O.; Huseynova, F.; Barragan-Montero, V. The Angiogenic Balance and Its Implications in Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases: An Overview. Medicina (B Aires) 2022, 58, 903. [CrossRef]

- Auchampach, J.A. Adenosine Receptors and Angiogenesis. Circ Res 2007, 101, 1075–1077. [CrossRef]

- Teng, R.-J.; Du, J.; Afolayan, A.J.; Eis, A.; Shi, Y.; Konduri, G.G. AMP Kinase Activation Improves Angiogenesis in Pulmonary Artery Endothelial Cells with in Utero Pulmonary Hypertension. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 2013, 304, L29–L42. [CrossRef]

- Feoktistov, I.; Goldstein, A.E.; Ryzhov, S.; Zeng, D.; Belardinelli, L.; Voyno-Yasenetskaya, T.; Biaggioni, I. Differential Expression of Adenosine Receptors in Human Endothelial Cells. Circ Res 2002, 90, 531–538. [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.N.; Youkey, R.; Liu, X.; Jia, L.; Blatt, R.; Day, Y.-J.; Sullivan, G.W.; Linden, J.; Tucker, A.L. A 1 Adenosine Receptor Activation Promotes Angiogenesis and Release of VEGF From Monocytes. Circ Res 2007, 101, 1130–1138. [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.-A.; Park, D.W.; Kwon, J.E.; Song, H.S.; Park, B.; Jeon, H.; Sohn, E.-H.; Koo, H.J.; Kang, S.C. Quinic Acid Inhibits Vascular Inflammation in TNF-α-Stimulated Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2017, 96, 563–571. [CrossRef]

- Kuramoto, H.; Nakanishi, T.; Takegawa, D.; Mieda, K.; Hosaka, K. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester Induces Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Production and Inhibits CXCL10 Production in Human Dental Pulp Cells. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2022, 44, 5691–5699. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, B.J.; Kim, J.H.; Yu, Y.S.; Kim, K.-W. Anti-Angiogenic Effect of Caffeic Acid on Retinal Neovascularization. Vascul Pharmacol 2009, 51, 262–267. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Ashraf, G.M.; Sheikh, K.; Khan, A.; Ali, S.; Ansari, Md.M.; Adnan, M.; Pasupuleti, V.R.; Hassan, Md.I. Potential Therapeutic Implications of Caffeic Acid in Cancer Signaling: Past, Present, and Future. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Gong, M.; Yang, X.; Li, M.; Shao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, Q.; Sun, L.; Xuan, L.; et al. NAD+ Attenuates Cardiac Injury after Myocardial Infarction in Diabetic Mice through Regulating Alternative Splicing of VEGF in Macrophages. Vascul Pharmacol 2022, 147, 107126. [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Lin, L.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Tong, Y.; Xiao, D.; Ding, J. Quercetin, a Dietary-Derived Flavonoid, Possesses Antiangiogenic Potential. Eur J Pharmacol 2003, 459, 255–262. [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Rankin, G.O.; Liu, L.; Daddysman, M.K.; Jiang, B.-H.; Chen, Y.C. Kaempferol Inhibits Angiogenesis and VEGF Expression Through Both HIF Dependent and Independent Pathways in Human Ovarian Cancer Cells. Nutr Cancer 2009, 61, 554–563. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Klepin, S.; Tsimring, L.S.; Pillus, L.; Hasty, J.; Hao, N. Engineering Longevity—Design of a Synthetic Gene Oscillator to Slow Cellular Aging. Science (1979) 2023, 380, 376–381. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-H.; Hayano, M.; Griffin, P.T.; Amorim, J.A.; Bonkowski, M.S.; Apostolides, J.K.; Salfati, E.L.; Blanchette, M.; Munding, E.M.; Bhakta, M.; et al. Loss of Epigenetic Information as a Cause of Mammalian Aging. Cell 2023, 186, 305-326.e27. [CrossRef]

- Arora, I.; Sharma, M.; Sun, L.Y.; Tollefsbol, T.O. The Epigenetic Link between Polyphenols, Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11, 1094. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.S.; Shanahan, F.; O’Toole, P.W. The Gut Microbiome as a Modulator of Healthy Ageing. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 19, 565–584. [CrossRef]

- Mallick, R.; Basak, S.; Das, R.K.; Banerjee, A.; Paul, S.; Pathak, S.; Duttaroy, A.K. Roles of the Gut Microbiota in Human Neurodevelopment and Adult Brain Disorders. Front Neurosci 2024, 18. [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S.; Esmeeta, A.; Dey, A.; Banerjee, A.; Saha, B.; Gopan, P.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Pathak, S. Impacts of Gut Microbiota Alteration on Age-Related Chronic Liver Diseases. Digestive and Liver Disease 2024, 56, 112–122. [CrossRef]

- Odamaki, T.; Kato, K.; Sugahara, H.; Hashikura, N.; Takahashi, S.; Xiao, J.-Z.; Abe, F.; Osawa, R. Age-Related Changes in Gut Microbiota Composition from Newborn to Centenarian: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Microbiol 2016, 16, 90. [CrossRef]

- Biagi, E.; Franceschi, C.; Rampelli, S.; Severgnini, M.; Ostan, R.; Turroni, S.; Consolandi, C.; Quercia, S.; Scurti, M.; Monti, D.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Extreme Longevity. Current Biology 2016, 26, 1480–1485. [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Hua, Y.; Zeng, B.; Ning, R.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J. Gut Microbiota Signatures of Longevity. Current Biology 2016, 26, R832–R833. [CrossRef]

- Eckburg, P.B.; Bik, E.M.; Bernstein, C.N.; Purdom, E.; Dethlefsen, L.; Sargent, M.; Gill, S.R.; Nelson, K.E.; Relman, D.A. Diversity of the Human Intestinal Microbial Flora. Science (1979) 2005, 308, 1635–1638. [CrossRef]

- Claesson, M.J.; Cusack, S.; O’Sullivan, O.; Greene-Diniz, R.; de Weerd, H.; Flannery, E.; Marchesi, J.R.; Falush, D.; Dinan, T.; Fitzgerald, G.; et al. Composition, Variability, and Temporal Stability of the Intestinal Microbiota of the Elderly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 4586–4591. [CrossRef]

- Ragonnaud, E.; Biragyn, A. Gut Microbiota as the Key Controllers of “Healthy” Aging of Elderly People. Immunity & Ageing 2021, 18, 2. [CrossRef]

- Hoyles, L.; Jiménez-Pranteda, M.L.; Chilloux, J.; Brial, F.; Myridakis, A.; Aranias, T.; Magnan, C.; Gibson, G.R.; Sanderson, J.D.; Nicholson, J.K.; et al. Metabolic Retroconversion of Trimethylamine N-Oxide and the Gut Microbiota. Microbiome 2018, 6, 73. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).