Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Contingency to ERM

2.2. Contingency on Sustainability Firm Performance

2.3. ERM on Sustainability Firm Performance

2.4. Green Intellectual Capital (GIC), on Sustainability Firm Performance

2.5. Green Intellectual Capital Moderates the Effect of ERM on Sustainability Firm Performance

2.6. The Moderating Role of ERM in the Relationship of Contingency Factors to Sustainability Firm Performance

3. Method

| Variable | Measurements | References |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainability Firm Performance | Tobin's Q = (Market value of equity + Book value of liabilities) / Book value of assets |

(Gordon et al., 2009) ; (Hoyt & Liebenberg, 2011) ; |

| Enterprise Risk Management | a quantitative (score 2), qualitative (score 1), or no ERM (score 0) approach | (Pangestuti et al., 2024) |

| Green Intellectual Capital | MVAIC (Modified Value Added Intellectual Capital) = Human Capital Efficiency (HCE) + Structural Capital Efficiency (SCE) + Relational Capital Efficiency (RCE) | (Jirakraisiri et al., 2021; Yadiati et al., 2019). |

| Contigency Factors | ||

|

number of business segments | (Ge & McVay, 2005; Gordon et al., 2009) |

|

ratio of the book value of debt to the market value of equity | (Hoyt et al., 2009) |

|

natural logarithm of total assets | (Razali & Tahir, 2011) |

|

the Herfindahl-Hirschman index | (Chang & Yoo, 2023; Madobi & Umar, 2021). |

|

dichotomously (1 if there is international diversification, 0 if not) | (Capar et al., 2015; Espinosa-Méndez et al., 2021; Karthik, 2015). |

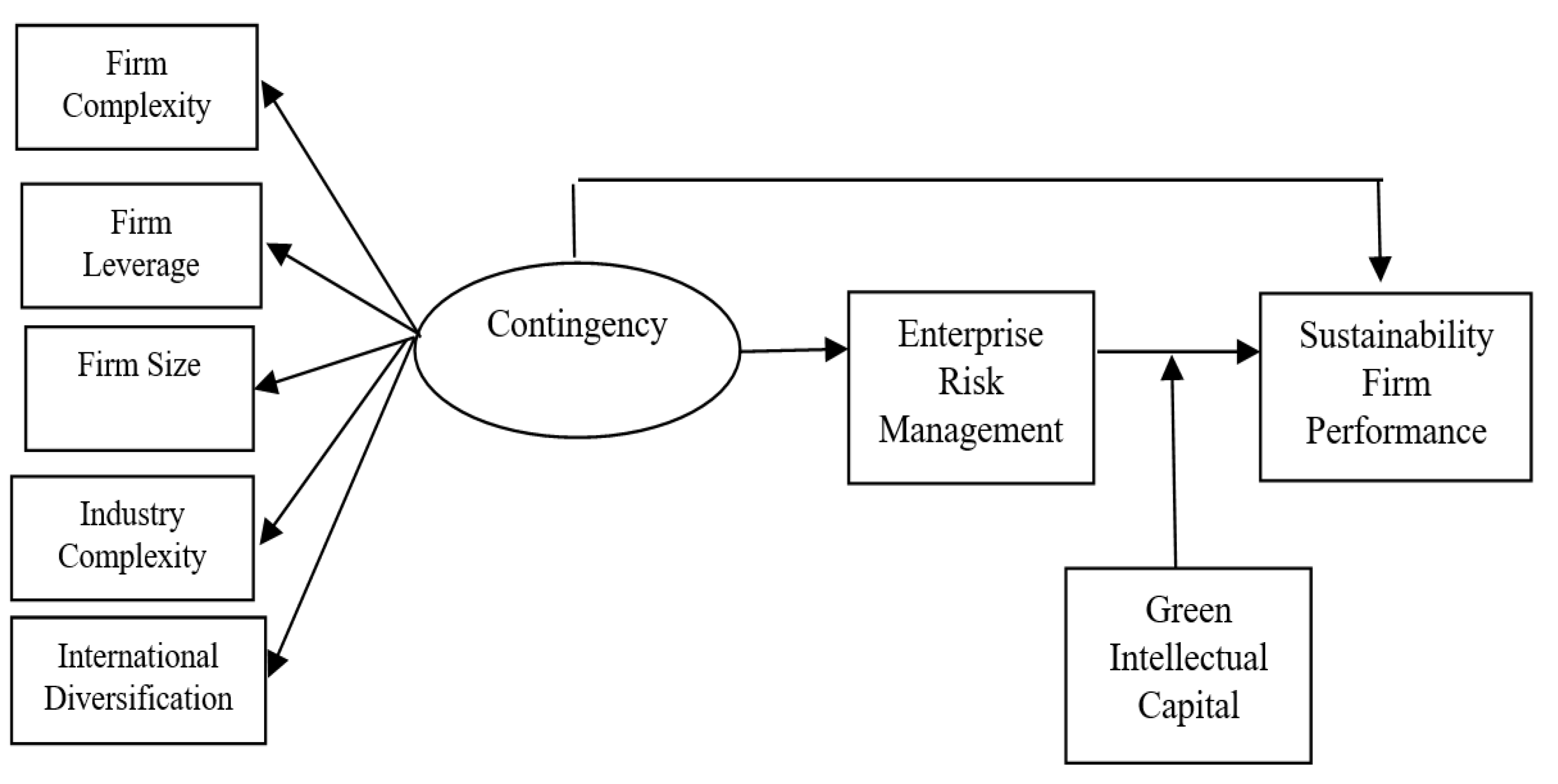

- Exogenous Variables (Independent Variables): Firm Complexity (FC), Firm Leverage (FL), Firm Size (FS), Industry Complexity (IC), International Diversification (ID)

-

Contingency (C):The central mediator that connects the exogenous variables to the dependent variables.Equation for Contingency (C):C = β1.FC + β2. FL + β3.FS + β4. IC + β5 .ID + ϵCWhere:

- -

- β1,β2,β3,β4,β5 are the coefficients to be estimated.

- -

- ϵC is the error term for the contingency variable.

-

Endogenous Variables (Dependent Variables): Sustainability Firm Performance (SFP), Enterprise Risk Management (ERM), and Green Intellectual Capital (GIC)The relationships can be formulated as:ERM=γ1⋅C+ϵERMSFP=γ2⋅C+γ3⋅GIC+ϵSFPGIC=γ4⋅C+ϵGICWhere:

- -

- γ1,γ2,γ3, are the coefficients to be estimated.

- -

- ϵERM,ϵSFP,ϵGIC are the error terms for each endogenous variable.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

| Variables | Mean | Median | Max | Min | Std. Dev. | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability Firm Performance | 1.218930 | 1.018572 | 5.331107 | 0.204720 | 0.742213 | 1640 |

| Enterprise Risk Management | 0.019919 | 0.020000 | 0.031250 | 0.003750 | 0.003252 | 1640 |

| Green Intellectual Capital | 15.62967 | 15.91114 | 23.83971 | 5.129380 | 3.465822 | 1640 |

| Contingency factor: | 1640 | |||||

| a. Firm Complexity | 2.937979 | 3.000000 | 10.00000 | 1.000000 | 1.211141 | 1640 |

| b. Financial Leverage | 1.715193 | 0.860262 | 22.74331 | 0.000650 | 2.648160 | 1640 |

| c. Firm Size | 17.12995 | 16.83968 | 25.60336 | 1.609438 | 4.177361 | 1640 |

| d. Industry Competition | 0.015813 | 0.004204 | 0.182923 | 0.000052 | 0.026769 | 1640 |

| e. International Diversification | 0.565157 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.495909 | 1640 |

| Variable | Singapura | Indonesia | Malaysia | Filipina | Thailand | Vietnam | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Deviasi | Mean | Std. Deviasi | Mean | Std. Deviasi | Mean | Std. Deviasi | Mean | Std. Deviasi | Mean | Std. Deviasi | |

| Sustainability Firm Performance | 1.29380 | 0.64236 | 1.28537 | 0.86521 | 1.14556 | 0.62131 | 1.08231 | 0.57111 | 1.07125 | 0.80116 | 1.05262 | 0.26532 |

| Enterprise Risk Management | 0.02087 | 0.00396 | 0.01975 | 0.00178 | 0.01949 | 0.00309 | 0.01692 | 0.00285 | 0.01969 | 0.00290 | 0.01668 | 0.00258 |

| Green Intellectual Capital | 18.44682 | 2.26274 | 16.19979 | 3.39349 | 17.86967 | 0.74554 | 13.25275 | 2.24093 | 14.10909 | 1.96921 | 11.01591 | 1.97871 |

| Contingency factor : | ||||||||||||

| a. Firm Complexity | 2.75862 | 1.01272 | 2.89237 | 1.40244 | 3.37912 | 1.33966 | 2.09524 | 1.18749 | 3.11290 | 0.84267 | 1.90476 | 0.82075 |

| b. Financial Leverage | 1.28537 | 1.48850 | 2.24372 | 3.46274 | 2.75468 | 3.26826 | 0.57457 | 0.77335 | 1.00865 | 1.27427 | 1.86974 | 1.87111 |

| c. Firm Size | 16.18664 | 1.77063 | 21.55927 | 1.71069 | 20.44412 | 0.80649 | 12.90114 | 3.80365 | 13.95157 | 1.70048 | 11.47333 | 1.39545 |

| d. Industry Competition | 0.02686 | 0.04114 | 0.01114 | 0.01709 | 0.01502 | 0.01760 | 0.03998 | 0.03869 | 0.00873 | 0.01958 | 0.05969 | 0.03345 |

| e. International Diversification | 0.81281 | 0.39103 | 0.75147 | 0.43259 | 0.32967 | 0.47139 | 0.73016 | 0.44744 | 0.35023 | 0.47759 | 0.09524 | 0.29710 |

4.2. Discussion

4.2.1. The Effect of Contingency on ERM

4.2.2. Effect of Contingency on Sustainability Firm Performance

4.2.3. The Effect of ERM on Sustainability Firm Performance

4.2.4. The Effect of Green Intellectual Capital on Sustainability Firm Performance

4.2.5. Moderate Green Intelectual Capital the Influence of ERM to Sustainability Firm Performance

4.2.6. Effect of Contingency to Sustainability Firm Performance Through ERM

5. Conclusion

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

Funding

References

- Abdul Razak, S. E. , Mustapha, M., Mohammed Shah, S., & Abu Kasim, N. A. Sustainability risk management: Are Malaysian companies ready? Heliyon 2024, 10, e24681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I. Influence of enterprise risk management framework implementation and board equity ownership on firm performance in Nigerian financial sector: An initial finding. IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, J. , & Brockett, P. L. (2014). Enterprise Risk Management. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online. Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Alnaim, M. , & Metwally, A. B. M. Green Intellectual Capital and Corporate Environmental Performance: Does Environmental Management Accounting Matter? Administrative Sciences 2024, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nimer, M. Unpacking the Complexity of Corporate Sustainability: Green Innovation’s Mediating Role in Risk Management and Performance. International Journal of Financial Studies 2024, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, P. , & Eweje, G. Organisational drivers and sustainability implementation in the mining industry: A holistic theoretical framework. Business Strategy and the Environment 2023, 32, 5602–5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andini, S. P. , & Harsono, M. The Effect of Green Intellectual Capital on Environmental Performance with Green Human Resource Management as a Mediating Variable. International Journal of Economics, Business and Management Research 2024, 8, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggraini, A. , & Hidayat, N. The Influence of Company Complexity and Risk Management on Sustainability Performance. International Journal of Social Science Humanity & Management Research 2025, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardian, A. , & Kumral, M. Enhancing mine risk assessment through more accurate reproduction of correlations and interactions between uncertain variables. Mineral Economics 2021, 34, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiaei, K. , Jusoh, R., Barani, O., & Asiaei, A. How does green intellectual capital boost performance? The mediating role of environmental performance measurement systems. Business Strategy and the Environment 2022, 31, 1587–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharum, M. R. , & Pitt, M. Determining a conceptual framework for green FM intellectual capital. Journal of Facilities Management 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barki, H. , Rivard, S., & Talbot, J. An integrative contingency model of software project risk management. Journal of Management Information 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. B. Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. Journal of Management 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, M. S. , Clune, R., & Hermanson, D. R. Enterprise risk management: An empirical analysis of factors associated with the extent of implementation. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 2005, 24, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capar, N. , Chinta, R., & Sussan, F. Effects of International Diversification and Firm Resources on Firm Performance Risk. Journal of Management and Strategy 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairani,; Siregar, S. V. Disclosure of enterprise risk management in ASEAN 5: Sustainable development for green economy. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 716, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y. J. , & Yoo, J. W. How Does the Degree of Competition in an Industry Affect a Company’s Environmental Management and Performance? Sustainability 2023, 15, 7675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlopecký, J. (2018). Strategic risk management of an enterprise depending on external conditions. In International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference Surveying Geology and Mining Ecology Management, SGEM (Vol. 18, Issue 1, pp. 855–861). [CrossRef]

- Daly, A. , Valacchi, G., & Raffo, J. (2019). Mining patent data: Measuring innovation in the mining industry with patents. In World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Economic Research Working Paper (Issue 56).

- Dashwood, H. S. Towards Sustainable Mining: The Corporate Role in the Construction of Global Standards. Multinational Business Review 2007, 15, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvinsson, L. , & Kivikas, M. Intellectual capital (IC) or Wissensbilanz process: some German experiences. Journal of Intellectual Capital 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericho, M. F. , & Amin, M. N. The Influence of Carbon Emission Disclosure Green Intellectual Capital and Environmental Performance on Firm Value With Moderation of Firm Size. Quantitative Economics and Management Studies 2024, 5, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERM. (2004). COSO. In Enterprise Risk Management – Integrated Framework. [CrossRef]

- Esmailikia, G., N. M., & G. A. The Relationship Between Contingency Factors and Non-Financial Sustainability Performance; the Moderating Role of Managers’ Behavioral Dimension. Journal Economic and Business 2023, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Méndez, C. , Araya-Castillo, L., Jara Bertín, M., & Gorigoitía, J. International diversification, ownership structure and performance in an emerging market: evidence from Chile. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja 2021, 34, 1202–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faedfar, S. , Özyeşil, M., Çıkrıkçı, M., & Benhür Aktürk, E. Effective Risk Management and Sustainable Corporate Performance Integrating Innovation and Intellectual Capital: An Application on Istanbul Exchange Market. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M. , & Gallagher, R. The valuation implications of enterprise risk management maturity. Journal of Risk and Insurance 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, J. D. , & Fisher, W. A. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Florio, C. , & Leoni, G. Enterprise risk management and firm performance: The Italian case. The British Accounting Review 2017, 49, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fremeth, A. R. , & Richter, B. K. Profiting from Environmental Regulatory Uncertainty: Integrated Strategies for Competitive Advantage. California Management Review 2011, 54, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, V. (2019). Investment risk management at mining enterprises. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 105). [CrossRef]

- Ge, W. , & McVay, S. The Disclosure of Material Weaknesses in Internal Control after the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Accounting Horizons 2005, 19, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, N. O. , Taib, F. Md., & Ma, Y. Firm-Level Attributes, Industry-Specific Factors, Stakeholder Pressure, and Country-Level Attributes: Global Evidence of What Inspires Corporate Sustainability Practices and Performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golshan, N. M. , & Rasid, S. A. (2012). Determinants of enterprise risk management adoption: An empirical analysis of Malaysian public listed firms. In International Journal of Social and Human Citeseer. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.308.6781&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- Gordon, L. A. , Loeb, M. P., & Tseng, C. Y. Enterprise risk management and firm performance: A contingency perspective. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 2009, 28, 301–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, A. , & Febriansyah, Y. Analisis Faktor yang Mempengaruhi Enterprise Risk Management. Optimal: Jurnal Ekonomi Dan Kewirausahaan 2023, 16, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanisch, B. , & Wald, A. A Bibliometric View on the Use of Contingency Theory in Project Management Research. Project Management Journal 2012, 39, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, J. , & Vachon, S. Linking Environmental Management to Environmental Performance: The Interactive Role of Industry Context. Business Strategy and the Environment 2018, 27, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M. A. , Bierman, L., Shimizu, K., & Kochhar, R. Direct and Moderating Effects of Human Capital on Strategy and Performance in Professional Service Firms: A Resource-Based Perspective. Academy of Management Journal 2001, 44, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M. A. , Xu, K., & Carnes, C. M. Resource based theory in operations management research. Journal of Operations Management 2016, 41, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang Thanh, N. , & Truong Cong, B. Investigating the mediating role of green performance measurement systems in the nexus between green intellectual capital and environmental performance. Social Responsibility Journal 2024, 20, 2237–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Z. A contingency model of the association between strategy, environmental uncertainty and performance measurement: impact on organizational performance. International Business Review 2004, 13, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvey, S. S. , & Odei-Mensah, J. The measurements and performance of enterprise risk management: a comprehensive literature review. Journal of Risk Research 2023, 26, 778–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossein Nezhad Nedaei, B. , Abdul Rasid, S. Z., Sofian, S., Basiruddin, R., & Amanollah Nejad Kalkhouran, A. A Contingency-Based Framework for Managing Enterprise Risk. Global Business and Organizational Excellence 2015, 34, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, Moore, & Liebenberg. The Value of Enterprise Risk Management: Evidence from the U.S. Insurance Industry. The Society of Actuaries ERM Monograph Paper 2009.

- Ibrahim, F. S. , & Esa, M. (2017). A study on enterprise risk management and organizational performance: developer’s perspective. In International Journal of Civil Engineering and …. researchgate.net.

- Ireland, R. D. , Hitt, M. A., & Sirmon, D. G. A model of strategic enterpreneurship: The construct and its dimensions. Journal of Management 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, M. , & Crawford, J. (2024). Enterprise Risk Management, Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Jirakraisiri, J. , Badir, Y. F., & Frank, B. Translating green strategic intent into green process innovation performance: the role of green intellectual capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital 2021, 22, 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, D. R., & S. C. International Diversification and Firm Performance: The Contingent Influence of Product Diversification. Research Papers in Economics 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. J. Why do firms adopt enterprise risk management (ERM)? Empirical evidence from France. Management Decision 2016, 54, 1886–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. N. , & Ali, E. I. E. The Moderating Role of Intellectual Capital Between Enterprise Risk Management and Firm Performance: A Conceptual Review. American Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 2017, 2, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W. , Asif, M., & Shah, S. Q. (2020). An Empirical Analysis of Enterprise Risk Management and Firm’s Value: Evidence from Pakistan. In Journal of Independent Studies & …. jisr.szabist.edu.pk. http://www.jisr.szabist.edu.pk/JISR-MSSE/Publication/2020/18/1/588/Article/An_Empirical_Analysis_of_Enterprise.pdf.

- Kianto, A. , Andreeva, T., & Pavlov, Y. The impact of intellectual capital management on company competitiveness and financial performance. Knowledge Management Research and Practice 2013, 11, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komara, A. , Ghozali, I., & Januarti, I. (2020). Examining the Firm Value Based on Signaling Theory. International Conference on Accounting, Management, and Entrepreneurship 2019, 123, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujansivu, P. , & Lonnqvist, A. How do investments in intellectual capital create profits? … Learning and Intellectual Capital 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamptey, E. K. , & S. R. P. Fraud Risk Management Over Financial Reporting: A Contingency Theory Perspective. Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, P. , & Gatzert, N. Determinants and value of enterprise risk management: empirical evidence from Germany. European Journal of Finance 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H. , Chen, R. C. Y., Hung, S.-W., & Yang, C.-X. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Value: The Mediating Role of Investor Recognition. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 2020, 56, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Liebenberg, A. P. , & Hoyt, R. E. The Determinants of Enterprise Risk Management: Evidence From the Appointment of Chief Risk Officers. Risk Management 2003, 6, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIU, X. , & LIU, H. Research on Influencing Factors for Implement of Enterprise-wide Risk Management——An Empirical Data Analysis of Listed Companies. Journal of Social Science of Hunan Normal en.cnki.com.cn. https://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-HNSS201401013.htm. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Madobi, S. , & Umar, S. Enterprise Risk Management Practices and Banks Value: Moderating Effect of Industry Competition. , Business and Economics Journal https://www.aambejournal.org/index.php/aambej/article/view/65. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Maharani, P. P. , & Pangestuti, D. C. The Role of Environmental Uncertainty, Firm Size, and Enterprise Risk Management to Improve Firm Performance. Formosa Journal of Sustainable Research 2024, 3, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. F. , Zaman, M., & Buckby, S. Enterprise risk management and firm performance: Role of the risk committee. Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, B. (2008). Impacting future value: how to manage your intellectual capital. cimaglobal.com. https://www.cimaglobal.com/Documents/ImportedDocuments/tech_mag_impacting_future_value_may08.pdf.pdf.

- Marr, B. , Gray, D., & Neely, A. Why do firms measure their intellectual capital? Journal of Intellectual Capital 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Falcó, J. , Sánchez-García, E., Marco-Lajara, B., & Zaragoza-Sáez, P. Green intellectual capital and sustainable competitive advantage: unraveling role of environmental management accounting and green entrepreneurship orientation. Journal of Intellectual Capital 2025, 26, 104–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikes, A. , & Kaplan, R. S. Managing Risks: Towards a Contingency Theory of Enterprise Risk Management. SSRN Electronic Journal Elsevier BV 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mikes, A. & Kaplan, R. S. (2015). When one size doesn’t fit all: Evolving directions in the research and practice of enterprise risk management. In Journal of Applied Corporate Finance. Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jacf.12102.

- Moeller, R. R. (2007). COSO Enterprise Risk Management: Understanding the New Integrated ERM Framework. In Internal Auditing. John Wiley & Sons.

- Natasha Nathania Ibrahim,; Ardiansyah Rasyid. Pengaruh Dewan Komisaris, Leverage, Kepemilikan Publik, Dan Firm Size Terhadap Pengungkapan ERM. Jurnal Paradigma Akuntansi 2022, 4, 1045–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. K. , & Vo, D. T. Enterprise risk management and solvency: The case of the listed EU insurers. Journal of Business Research https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0148296319305594. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Y. , & Cheng, Y. Do intellectual capitals matter to firm value enhancement ? Evidences from Taiwan. Journal of Intellectual Capital 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurcahyo, A. The Effect of Strategic Leadership and Environmental Management on Firm Performance Mediated by Competitive Advantage in The Mining Industry. Dinasti International Journal of Economics, Finance & Accounting 2024, 5, 1828–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otley, D. The contingency theory of management accounting and control: 1980-2014. Management Accounting Research 2016, 31, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagach, D. P. , & Warr, R. S. The effects of enterprise risk management on firm value. Journal of Finance 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pambudi Raharjo, T. , & Hasnawati, H. The Influence of Company Strategy, Enterprise Risk Management, Company Size and Leverage On Environmental Performance. Devotion : Journal of Research and Community Service 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangestuti, D. C. , Muktiyanto, A., Geraldina, I., & D, D. Modified of ERM Index for Southeast Asia. Cogent Business & Management 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangestuti, D. , Muktiyanto, A., Geraldina, I., & Darmawan, D. Optimizing firm performance through contingency factors, enterprise risk management, and intellectual capital in Southeast Asian mining enterprises. Investment Management and Financial Innovations 2024, 21, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radebe, N. , & Chipangamate, N. Mining industry risks, and future critical minerals and metals supply chain resilience in emerging markets. Resources Policy 2024, 91, 104887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, A. R. , & Tahir, I. M. The determinants of enterprise risk management (ERM) practices in Malaysian public listed companies. Journal of Social and Development 2011. https://ojs.amhinternational.com/index.php/jsds/article/view/645.

- Reid, R. D. (2005). FMEA—something old, something new. In Quality Progress. generalpurposehosting.com. http://www.generalpurposehosting.com/updates/dec08/FMEA%97Something Old Something New.PDF.

- Resende, S. , Monje-Amor, A., & Calvo, N. Enterprise risk management and firm performance: The mediating role of corporate social responsibility in the <scp>European Union</scp> region. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2024, 31, 2852–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A. , Cepel, M., Ferraris, A., Ashfaq, K., & Rehman, S. U. Nexus among green intellectual capital, green information systems, green management initiatives and sustainable performance: a mediated-moderated perspective. Journal of Intellectual Capital 2024, 25, 297–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rina Yuniarti, Noorlailie Soewarno,; Isnalita. Green innovation on firm value with financial performance as mediating variable: Evidence of the mining industry. Asian Academy of Management Journal 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A. , & Mustafa, A. Analysing the impact of green intellectual capital on environmental performance: the mediating role of green training and development. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 2024, 36, 3357–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, J. , & Andersen, T. J. Making Risk Management Strategic: Integrating Enterprise Risk Management with Strategic Planning. European Management Review 2019, 16, 719–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevil, A. , Cruz, A., Reyes, T., & Vassolo, R. When Being Large Is Not an Advantage: How Innovation Impacts the Sustainability of Firm Performance in Natural Resource Industries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. Q. A. , Lai, F.-W., Shad, M. K., Hamad, S., & Ellili, N. O. D. Exploring the effect of enterprise risk management for ESG risks towards green growth. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2025, 74, 224–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatnawi, S. A. , & Eldaia, M. The Factors Influencing The Enterprise Risk Management Practices and Firm Performance in Jordan and Malaysia. … Journal of Recent Technology and https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3568299. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shehzad, M. U. , Zhang, J., Dost, M., Ahmad, M. S., & Alam, S. Linking green intellectual capital, ambidextrous green innovation and firms green performance: evidence from Pakistani manufacturing firms. Journal of Intellectual Capital 2023, 24, 974–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. R. Enterprise Risk Management and Firm Value: Evidence from Brazil. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 2019, 55, 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohu, J. M. , Hongyun, T., Junejo, I., Akhtar, S., Ejaz, F., Dunay, A., & Hossain, M. B. Driving sustainable competitiveness: unveiling the nexus of green intellectual capital and environmental regulations on greening SME performance. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subaida, I. , Nurkholis, N., & Mardiati, E. Effect of Intellectual Capital and Intellectual Capital Disclosure on Firm Value. Jurnal Aplikasi Manajemen 2018, 16, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, N. , Wahyuni, D., Cooper, B. J., &... Integration of carbon risks and opportunities in enterprise risk management systems: evidence from Australian firms. Journal of Cleaner 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tongli, L. , Ping, E. J., & Chiu, W. K. C. International Diversification and Performance: Evidence from Singapore. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 2005, 22, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trần Thị Phương, T. , Đậu Thị Kim, T., Trần Anh, H., & Phạm Trà, L. Enterprise Risk Management, Information Technology Structure, and Firm Performance: Moderating Role of Competitive Advantage. Journal Of Asian Business And Economic Studies 2022, 33, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volberda, H. W. , van der Weerdt, N., Verwaal, E., Stienstra, M., & Verdu, A. J. Contingency fit, institutional fit, and firm performance: A metafit approach to organization-environment relationships. Organization Science 2012, 23, 1040–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. S. (2011). Intellectual capital and firm performance. In Annual Conference on Innovations in Business cibmp.org. https://www.cibmp.org/Papers/Paper566.pdf.

- Wang, T. The relationship between external financing activities and earnings management: Evidence from enterprise risk management. International Review of Economics and Finance 2018, 58, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadiati, W. , Nissa, N., Paulus, S., Suharman, H., & Meiryani, M. The Role Of Green Intellectual Capital And Organizational Reputation In Influencing Environmental Performance. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy 2019, 9, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, Y. M. , Omar, M. K., Zaman, M. D. K., & Samad, S. Do all elements of green intellectual capital contribute toward business sustainability? Evidence from the Malaysian context using the Partial Least Squares method. Journal of Cleaner 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zungu, S. , Sibanda, M., & Rajaram, R. The effect of the enterprise risk management quality on firm risks: A case of the South African Mining Sector. African Journal of Business and Economic Research 2018, 13, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P Value | R2 | Adj R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contingency -> ERM | 0.369 | 0.372 | 0.024 | 15.271 | 0.003 | ||

| Contingency -> SFP | 0.101 | 0.101 | 0.029 | 3.476 | 0.041 | ||

| ERM -> SFP | 0.146 | 0.146 | 0.027 | 5.498 | 0.027 | 0.728 | 0.753 |

| GIC -> SFP | 0.254 | 0.254 | 0.027 | 9.460 | 0.012 | ||

| GIC*ERM -> SFP | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.028 | 3.515 | 0.035 | ||

| Contingency -> ERM -> SFP | 0.054 | 0.054 | 0.010 | 5.217 | 0.034 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).