Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

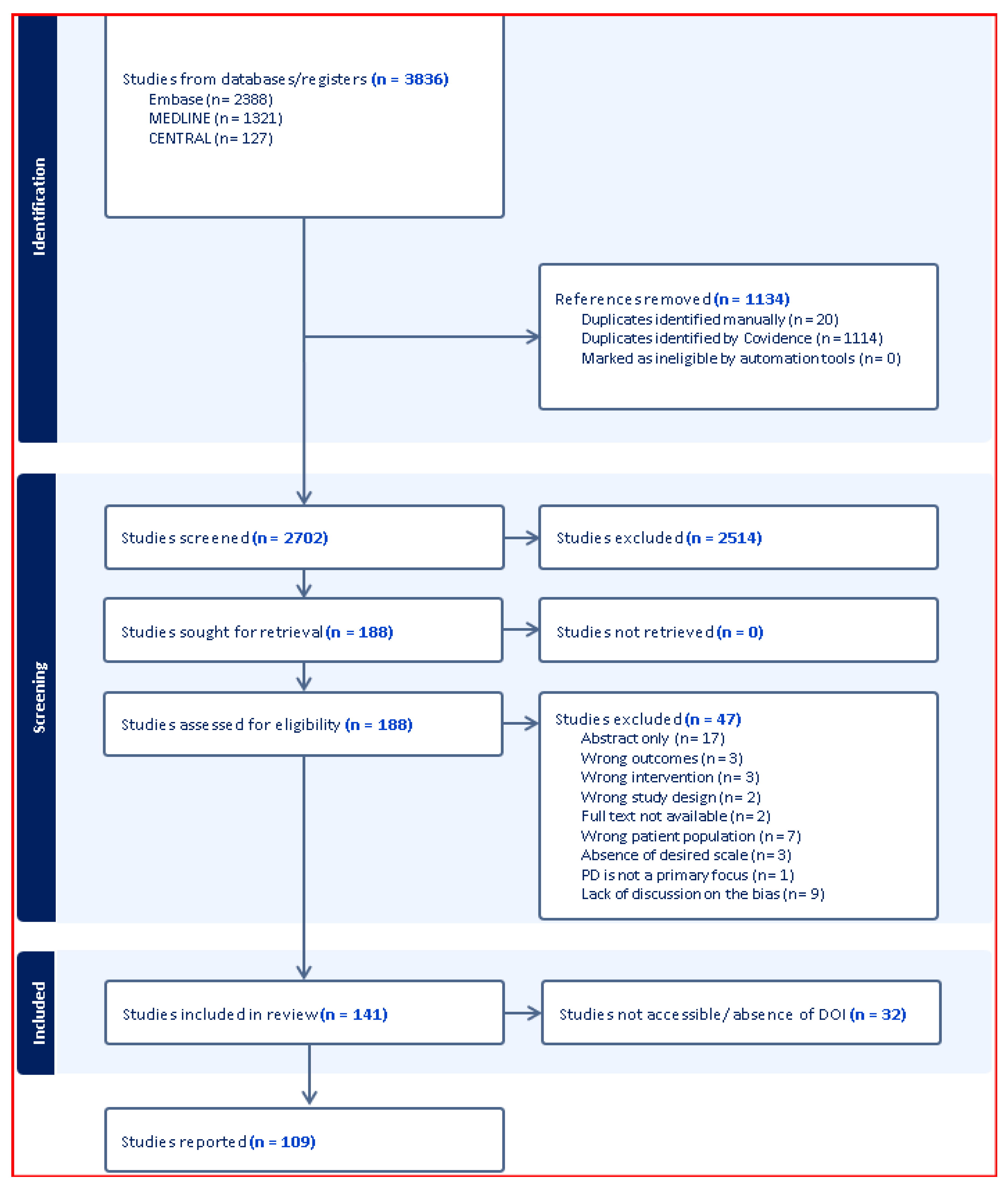

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Bias Assessment Framework

| Primary Bias Domains | Methodological Bias Domains |

| 1. Race/ethnicity data capture and analysis | 9. Assessment timing standardization |

| 2. Sex/gender distribution reporting and analysis | 10. Treatment effect controls |

| 3. Age-specific normative values utilization | 11. UPDRS ON/OFF state documentation |

| 4. Educational background adjustment | 12. Cognitive domain specification |

| 5. Geographic representation | 13. Institutional resource reporting |

| 6. Socioeconomic status consideration | 14. Underrepresented subgroup analysis |

| 7. Administrator training documentation | 15. Inclusion/exclusion criteria specification |

| 8. Digital literacy and technology access barriers | 16. Confounding variable control |

| 17. Sample size adequacy |

2.4. Bibliometric Analysis

- Publication trends over time

- Geographic distribution analysis

- Author collaboration networks

- Journal impact assessment

- Citation pattern analysis

- Keyword co-occurrence mapping

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

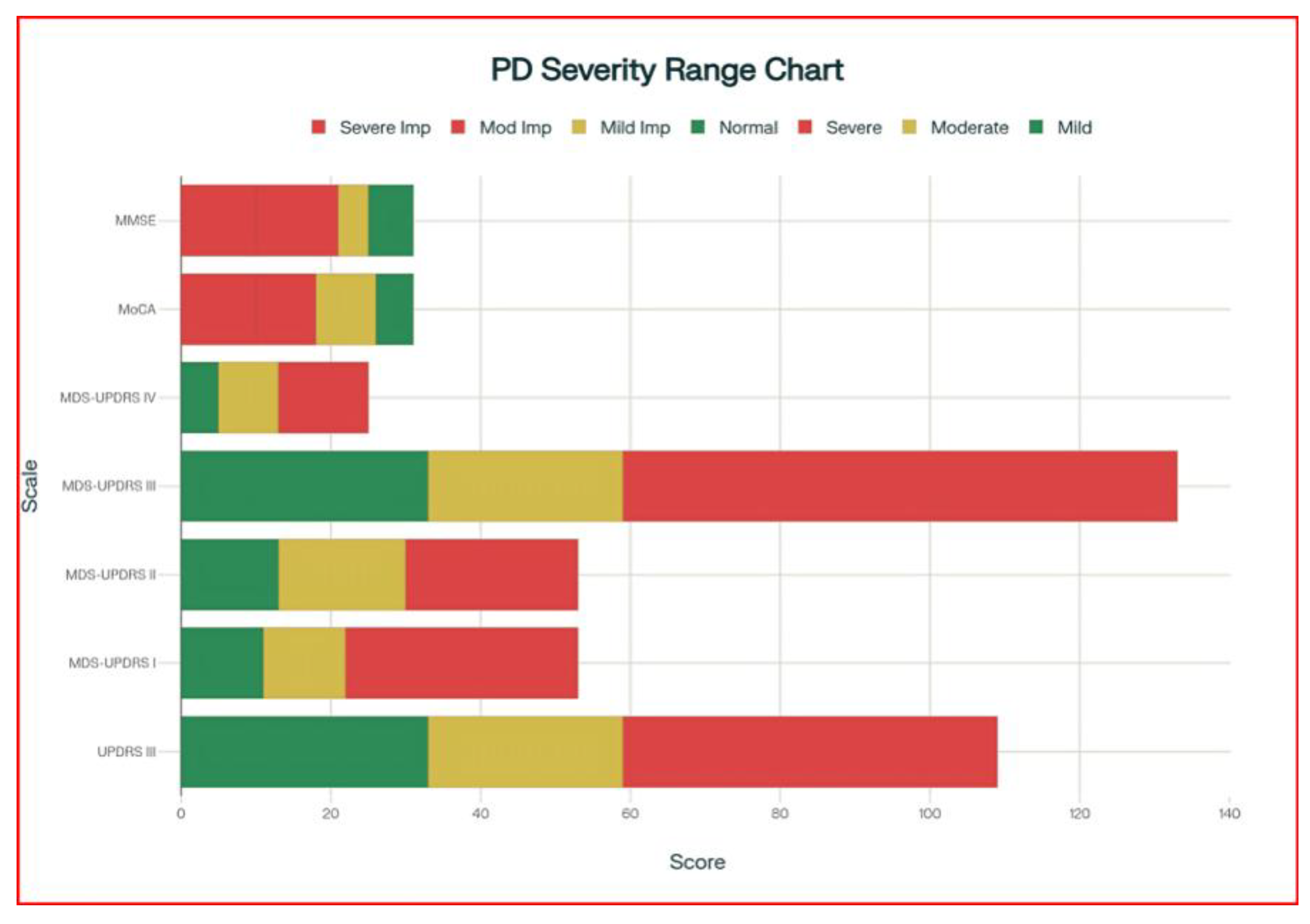

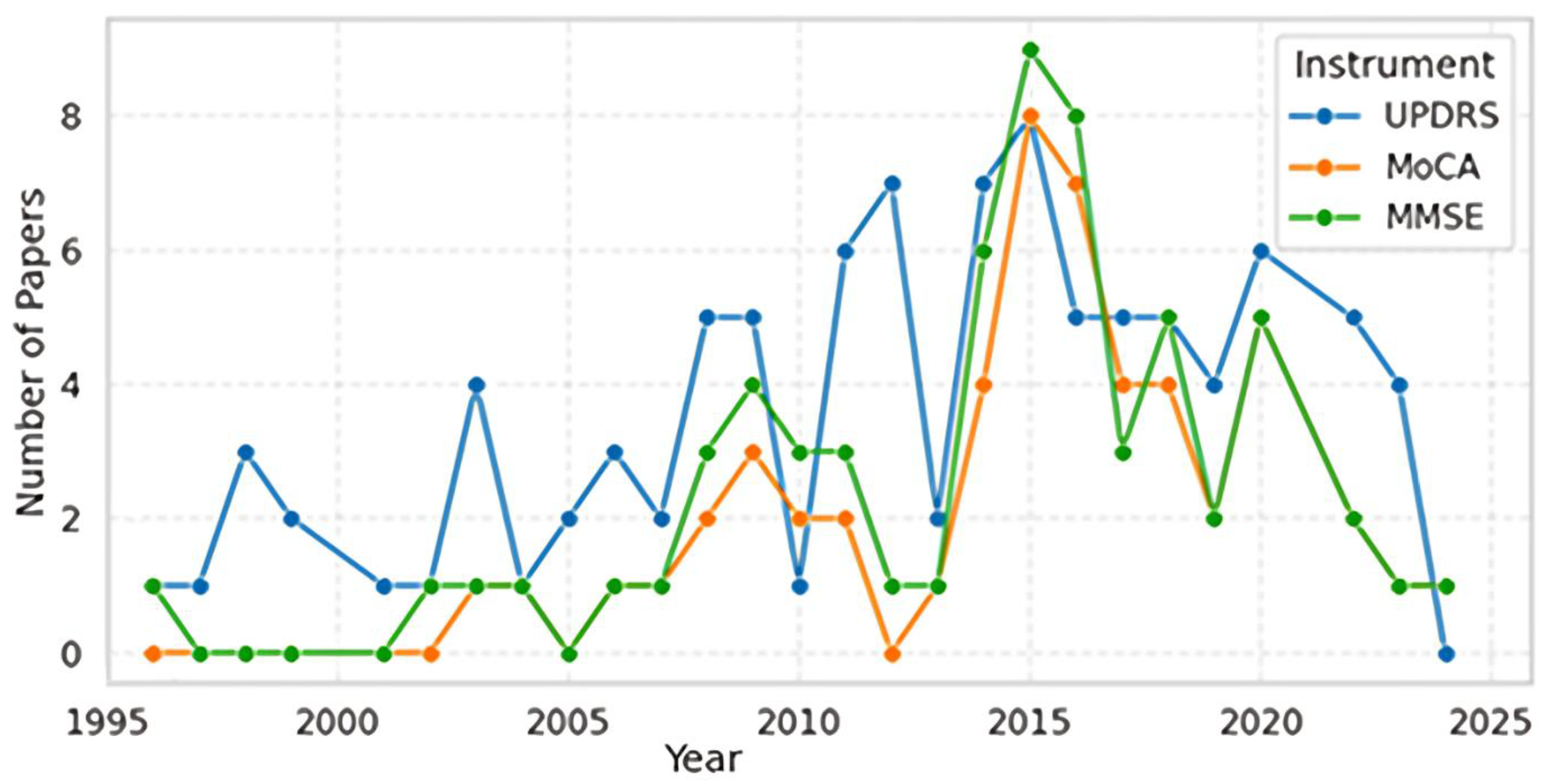

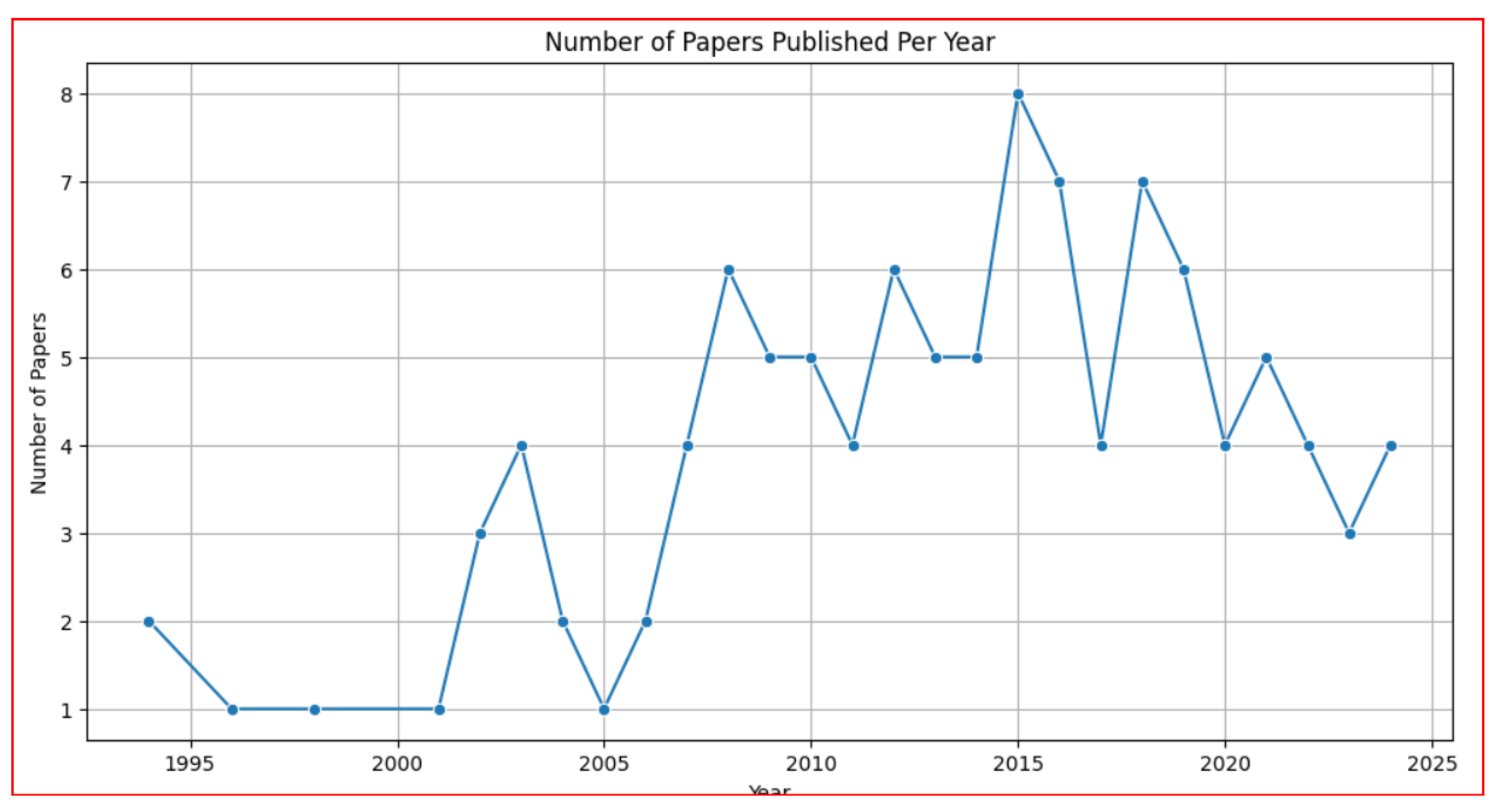

3.1. Publication Trends and Assessment Scale Development (1996-2024)

- Phase 1 (1996-2005) represents the establishment period with moderate UPDRS adoption and continued MMSE usage.

- Phase 2 (2006-2016) marks the innovation and validation period characterized by MoCA introduction and peak research activity across all scales.

- Phase 3 (2017-2024) shows the consolidation period with declining overall publication volumes, suggesting methodological maturity and established clinical utility.

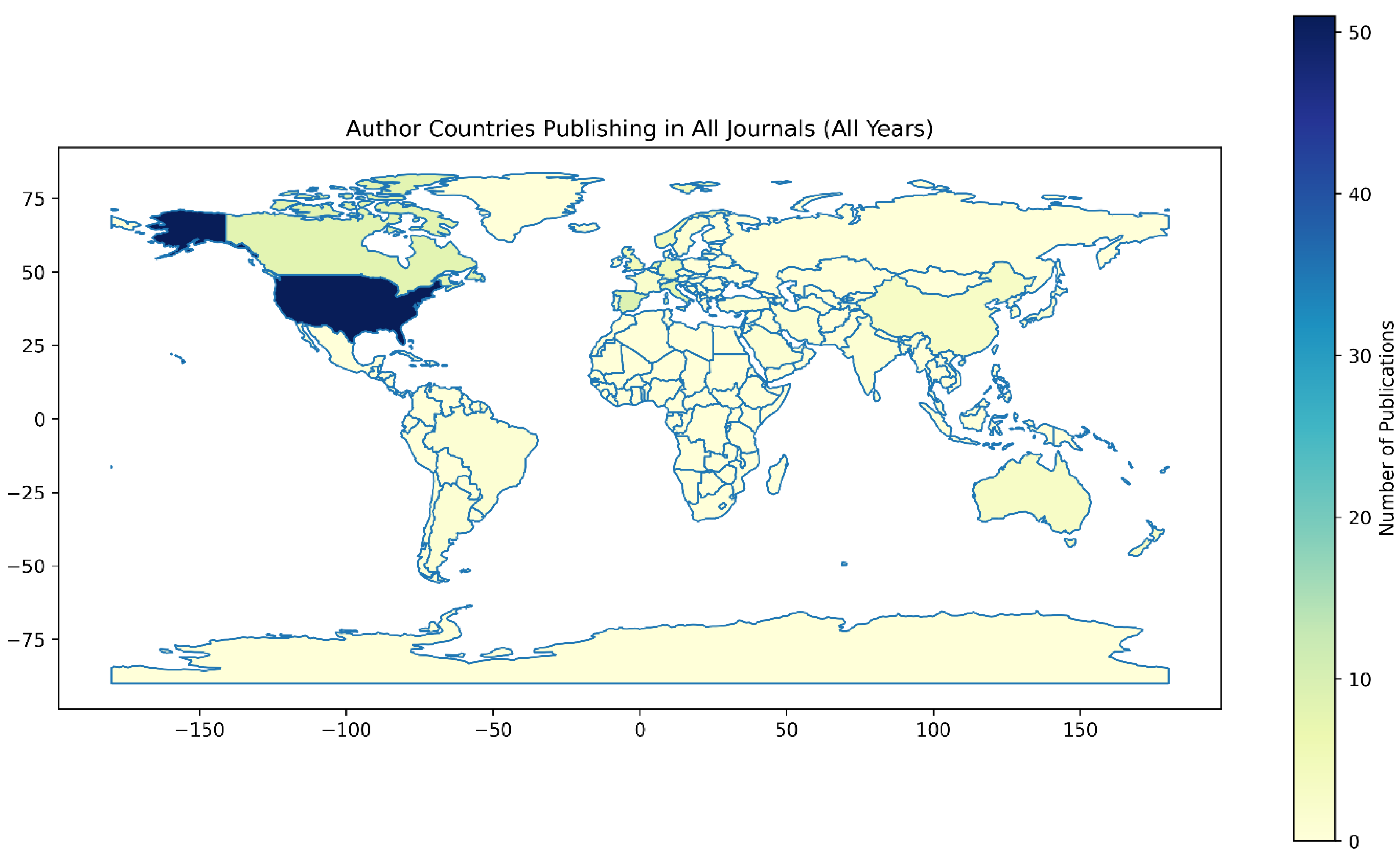

3.2. Geographic Distribution Analysis

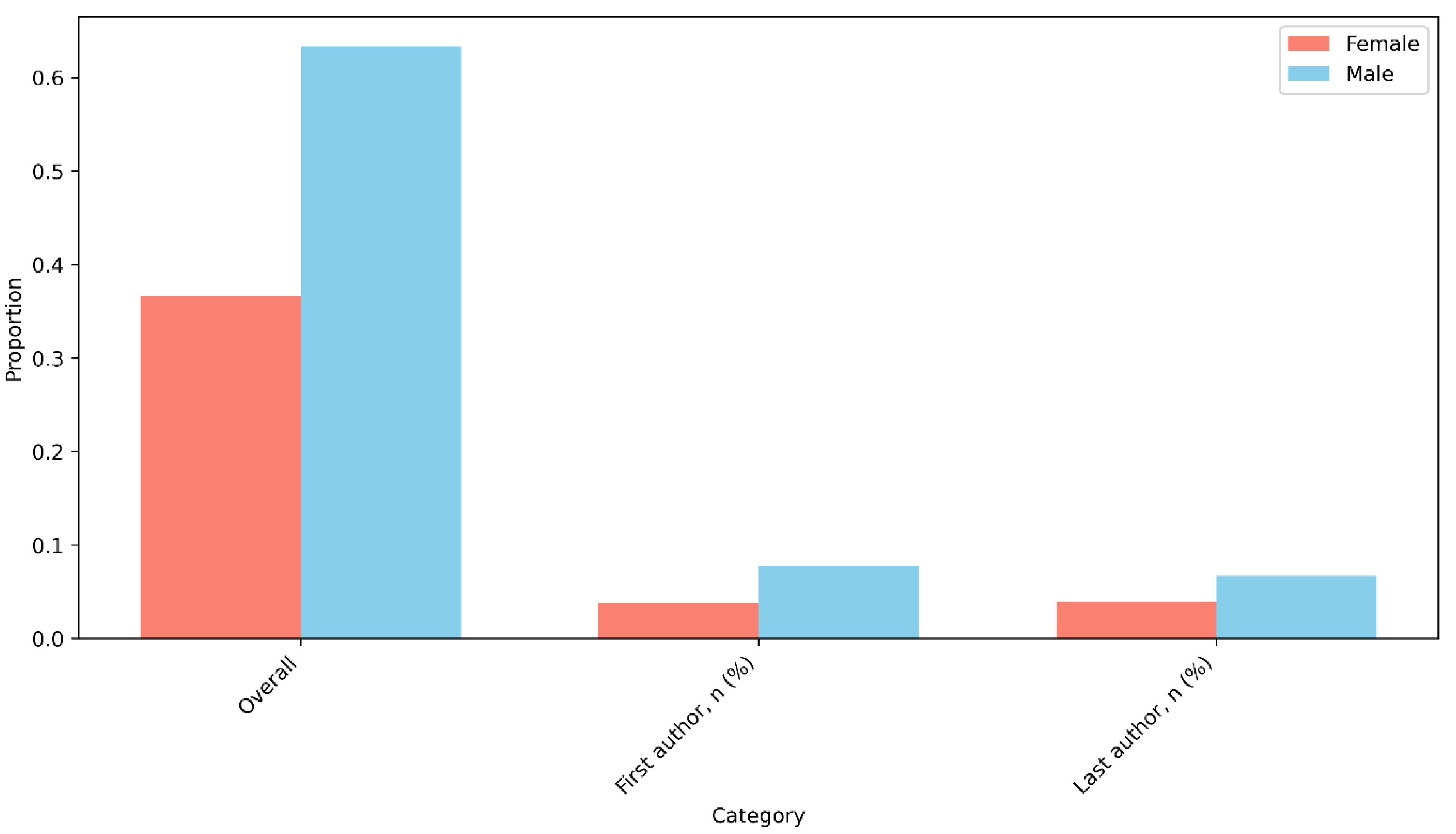

3.3. Authorship Patterns and Gender Distribution

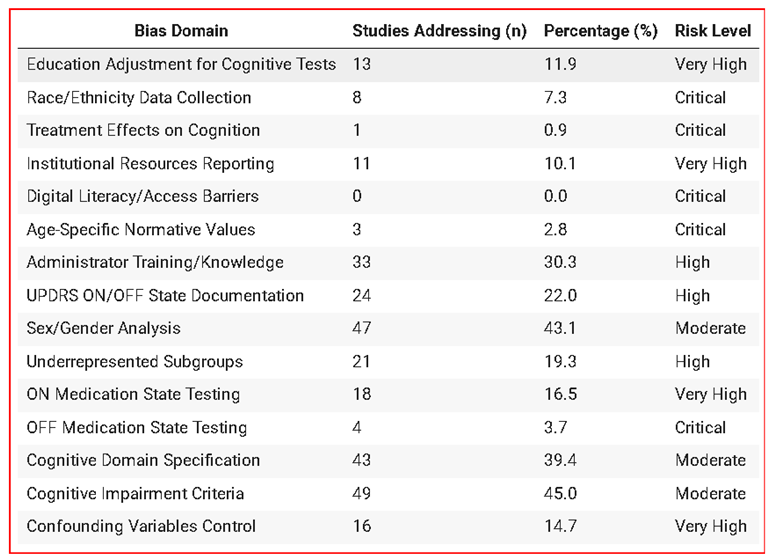

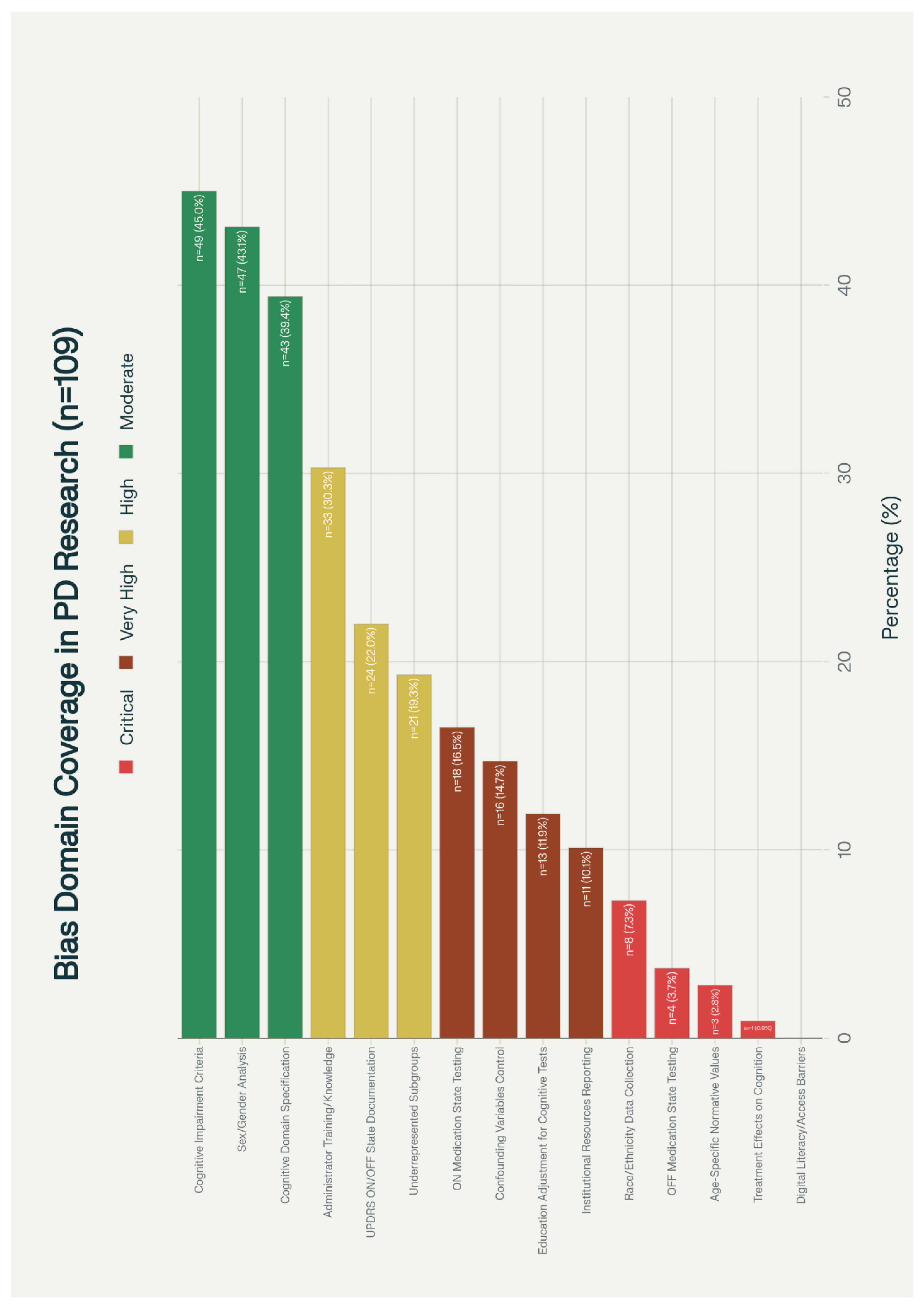

3.4. Bias Domain Assessment

3.5. Journal and Citation Analysis

3.6. Temporal Trends

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Geographic and Economic Disparities

4.3. Demographic Representation Gaps

4.4. Gender Disparities in Research Leadership

4.5. Methodological Bias Implications

4.6. Implications for Clinical Practice and Policy

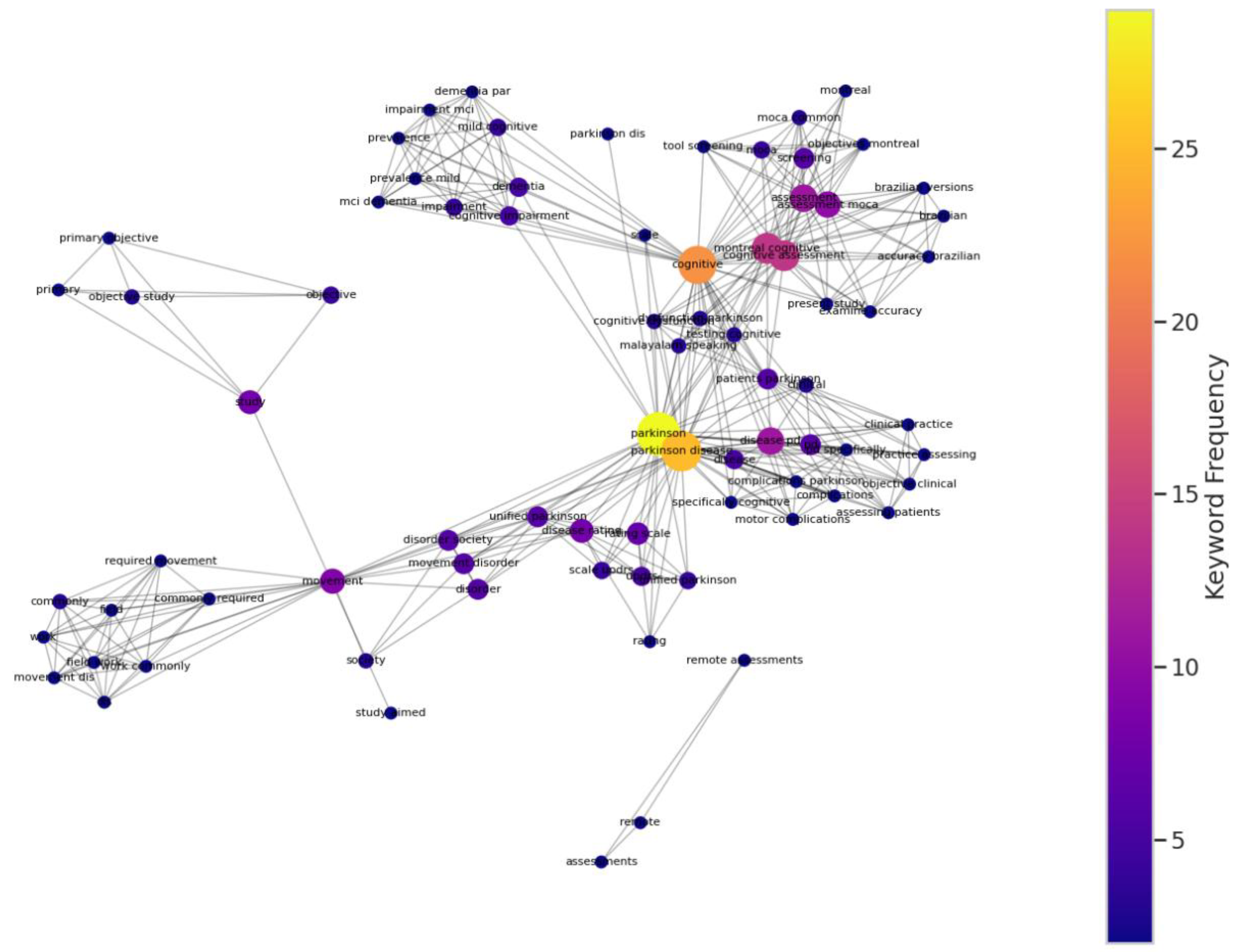

4.7. Keyword Co-occurrence Network Analysis

4.8. Future Research Directions

- Inclusive validation studies: Large-scale validation studies specifically designed to assess scale performance across diverse demographic groups are urgently needed.

- Cultural adaptation research: Systematic investigation of cultural and linguistic factors affecting scale performance should be prioritized, particularly for global implementation.

- Digital equity research: As assessment tools increasingly incorporate digital components, research addressing digital literacy and access barriers becomes essential.

- Bias mitigation strategies: Development and testing of specific interventions to reduce bias in clinical assessment should be prioritized.

4.9. Limitations

5. Conclusions

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Total papers analyzed | 109 |

| Publication period | 1996-2024 |

| Total authors examined | 655 |

| Countries represented | 34 |

| Journals represented | 47 |

| Most common assessment scales | UPDRS, MDS-UPDRS, MoCA, MMSE |

| JOURNAL TITLE | COUNTS | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Movement Disorders | 29 |

| 2. | Parkinsonism & Related Disorders | 11 |

| 3. | Movement Disorders Clinical Practice | 5 |

| 4. | Neurology | 5 |

| 5. | Neurological Sciences | 4 |

| 6. | Journal of Neurology | 4 |

| 7. | Journal of Parkinson’s Disease | 4 |

| 8. | International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry | 2 |

| 9. | American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Othe... | 2 |

| 10. | European Journal of Neurology | 2 |

| 11. | Revue Neurologique | 2 |

| 12. | The Clinical Neuropsychologist | 2 |

| 13. | Parkinson's Disease | 2 |

| 14. | Neurología (English Edition) | 2 |

| 15. | Aging Clinical and Experimental Research | 1 |

| 16. | Health Informatics Journal | 1 |

| 17. | Frontiers in Neurology | 1 |

| 18. | Digital Biomarkers | 1 |

| 19. | Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra | 1 |

| 20. | Clinical Parkinsonism & Related Disorders | 1 |

| 21. | Dementia & Neuropsychologia | 1 |

| 22. | Clinical Neuropharmacology | 1 |

| 23. | Brain and Cognition | 1 |

| 24. | Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders | 1 |

| 25. | Assessment | 1 |

| 26. | Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology | 1 |

| 27. | Applied Neuropsychology Adult | 1 |

| 28. | International Journal of Speech-Language Patho... | 1 |

| 29. | JAMA Neurology | 1 |

| 30. | IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabi... | 1 |

| 31. | Health and Quality of Life Outcomes | 1 |

| 32. | Journal of the Neurological Sciences | 1 |

| 33. | Journal of the American Geriatrics Society | 1 |

| 34. | Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery & Psychiatry | 1 |

| 35. | Journal of Movement Disorders | 1 |

| 36. | Journal of Clinical Neurology | 1 |

| 37. | Journal of Clinical Neuroscience | 1 |

| 38. | Journal of Advanced Nursing | 1 |

| 39. | Journal of Clinical Medicine | 1 |

| 40. | Ideggyógyászati Szemle | 1 |

| 41. | Neurological Research | 1 |

| 42. | Medical Image Analysis | 1 |

| 43. | NeuroRehabilitation An International Interdisc... | 1 |

| 44. | Neurologia i Neurochirurgia Polska | 1 |

| 45. | Neurology India | 1 |

| 46. | PLOS ONE | 1 |

| 47. | Value in Health | 1 |

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Data Availability Statement

Ethics Statement

References

- Antonini, A.; Abbruzzese, G.; Ferini-Strambi, L.; et al. Validation of the Italian version of the Movement Disorder Society--Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Neurological Sciences 2013, 34(5), 683–687. [CrossRef]

- Abdolahi, A.; Bull, M. T.; Darwin, K. C.; et al. A feasibility study of conducting the Montreal Cognitive Assessment remotely in individuals with movement disorders. Health Informatics Journal 2016, 22(2), 304–311. [CrossRef]

- Uc, E. Y.; McDermott, M. P.; Marder, K. S.; et al. Incidence of and risk factors for cognitive impairment in an early Parkinson disease clinical trial cohort. Neurology 2009, 73(18), 1469–1477. [CrossRef]

- Foley, T.; McKinlay, A.; Warren, N.; et al. Assessing the sensitivity and specificity of cognitive screening measures for people with Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation 2018, 43(4), 491–500. [CrossRef]

- Konstantopoulos, K.; Vogazianos, P.; Doskas, T. Normative data of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in the Greek population and parkinsonian dementia. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 2016, 31(3), 246–253. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J. L.; Coats, M. A.; Roe, C. M.; et al. Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale-Motor Exam: inter-rater reliability of advanced practice nurse and neurologist assessments. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2010, 66(6), 1382–1387. [CrossRef]

- Badrkhahan, S. Z.; Sikaroodi, H.; Sharifi, F.; et al. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA-P) scale among subjects with Parkinson’s disease. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult 2020, 27(5), 431–439. [CrossRef]

- Hoops, S.; Nazem, S.; Siderowf, A. D.; et al. Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2009, 73(21), 1738–1745. [CrossRef]

- Allison, K. M.; Hustad, K. C. Impact of sentence length and phonetic complexity on intelligibility of 5-year-old children with cerebral palsy. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 2014, 16(4), 396–407. [CrossRef]

- Goetz, C. G.; Choi, D.; Guo, Y.; et al. It is as it was: MDS-UPDRS part III scores cannot be combined with other parts to give a valid sum. Movement Disorders 2023, 38(2), 342–347. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martin, P.; Rodriguez-Blazquez, C.; Alvarez-Sanchez, M.; et al. Expanded and independent validation of the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS). Journal of Neurology 2013, 260(1), 228–236. [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Wong, D.; Alty, J. E.; et al. Parkinsonian hand or clinician’s eye? Finger tap bradykinesia interrater reliability for 21 movement disorder experts. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease 2023, 13(4), 525–536. [CrossRef]

- Goldman, J. G.; Stebbins, G. T.; Leung, V.; et al. Relationships among cognitive impairment, sleep, and fatigue in Parkinson’s disease using the MDS-UPDRS. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2014, 20(11), 1135–1139. [CrossRef]

- Rabey, J. M.; Klein, C.; Molochnikov, A.; et al. Comparison of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale and the Short Parkinson’s Evaluation Scale in patients with Parkinson’s disease after levodopa loading. Clinical Neuropharmacology 2002, 25(2), 83–88. [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, G. T.; Goetz, C. G. Factor structure of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale: Motor Examination section. Movement Disorders 1998, 13(4), 633–636. [CrossRef]

- Dalrymple-Alford, J. C.; MacAskill, M. R.; Nakas, C. T.; et al. The MoCA: well-suited screen for cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2010, 75(19), 1717–1725. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Oh, E.; Koh, S.-B.; et al. Evaluating the validity and reliability of the Korean version of the Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease-cognition. Journal of Movement Disorders 2024, 17(3), 328–332. [CrossRef]

- Roalf, D. R.; Moore, T. M.; Wolk, D. A.; et al. Defining and validating a short form Montreal Cognitive Assessment (s-MoCA) for use in neurodegenerative disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2016, 87(12), 1303–1310. [CrossRef]

- Parashos, S. A.; Elm, J.; Boyd, J. T.; et al. Validation of an ambulatory capacity measure in Parkinson disease: a construct derived from the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease 2015, 5(1), 67–73. [CrossRef]

- Pal, G.; Goetz, C. G. Assessing bradykinesia in parkinsonian disorders. Frontiers in Neurology 2013, 4, 54. [CrossRef]

- Siuda, J.; Boczarska-Jedynak, M.; Budrewicz, S.; et al. Validation of the Polish version of the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS). Neurologia i Neurochirurgia Polska 2020, 54(5), 416–425. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. R.; Cavanagh, J.; Sheridan, M.; et al. Factor structure of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in Parkinson disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2020, 35(2), 188–194. [CrossRef]

- Aarsland, D.; Brønnick, K.; Larsen, J. P.; et al. Cognitive impairment in incident, untreated Parkinson disease: the Norwegian ParkWest study. Neurology 2009, 72(13), 1121–1126. [CrossRef]

- Holroyd, S.; Currie, L. J.; Wooten, G. F. Validity, sensitivity and specificity of the mentation, behavior and mood subscale of the UPDRS. Neurological Research 2008, 30(5), 493–496. [CrossRef]

- Isella, V.; Mapelli, C.; Morielli, N.; et al. Validity and metric of MiniMental Parkinson and MiniMental State Examination in Parkinson’s disease. Neurological Sciences 2013, 34(10), 1751–1758. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martin, P.; Prieto, L.; Forjaz, M. J. Longitudinal metric properties of disability rating scales for Parkinson’s disease. Value in Health 2006, 9(6), 386–393. [CrossRef]

- Horváth, K.; Aschermann, Z.; Ács, P.; et al. Validation of the Hungarian Unified Dyskinesia Rating Scale. Ideggyogyaszati Szemle 2015, 68(5-6), 183–188. [CrossRef]

- Gülke, E.; Alsalem, M.; Kirsten, M.; et al. Comparison of Montreal cognitive assessment and Mattis dementia rating scale in the preoperative evaluation of subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 2022, 17(4), e0265314. [CrossRef]

- Grill, S.; Weuve, J.; Weisskopf, M. G. Predicting outcomes in Parkinson’s disease: comparison of simple motor performance measures and The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale-III. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease 2011, 1(3), 287–298. [CrossRef]

- Patrick, S. K.; Denington, A. A.; Gauthier, M. J.; et al. Quantification of the UPDRS rigidity scale. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2001, 9(1), 31–41. [CrossRef]

- Martignoni, E.; Franchignoni, F.; Pasetti, C.; et al. Psychometric properties of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale and of the Short Parkinson’s Evaluation Scale. Neurological Sciences 2003, 24(3), 190–191. [CrossRef]

- Ohta, K.; Takahashi, K.; Gotoh, J.; et al. Screening for impaired cognitive domains in a large Parkinson’s disease population and its application to the diagnostic procedure for Parkinson’s disease dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra 2014, 4(2), 147–159. [CrossRef]

- Hely, M. A.; Reid, W. G. J.; Adena, M. A.; et al. The Sydney multicenter study of Parkinson’s disease: the inevitability of dementia at 20 years. Movement Disorders 2008, 23(6), 837–844. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, W.; et al. Validation of neuropsychological tests to screen for dementia in Chinese patients with Parkinson’s disease. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias 2016, 31(4), 368–374. [CrossRef]

- Benge, J. F.; Kiselica, A. M. Rapid communication: Preliminary validation of a telephone adapted Montreal Cognitive Assessment for the identification of mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. The Clinical Neuropsychologist 2021, 35(1), 133–147. [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Zhao, Q.; Poston, K. L.; et al. Quantifying Parkinson’s disease motor severity under uncertainty using MDS-UPDRS videos. Medical Image Analysis 2021, 73, 102179. [CrossRef]

- Goetz, C. G.; Stebbins, G. T. Assuring interrater reliability for the UPDRS motor section: utility of the UPDRS teaching tape. Movement Disorders 2004, 19(12), 1453–1456. [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S. Comparison of self and proxy ratings for motor performance of individuals with Parkinson disease. Brain and Cognition 2016, 103, 62–69. [CrossRef]

- Movement Disorder Society Task Force on Rating Scales for Parkinson’s Disease. The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS): status and recommendations. Movement Disorders 2003, 18(7), 738–750. [CrossRef]

- Louis, E. D.; Levy, G.; Côte, L. J.; et al. Diagnosing Parkinson’s disease using videotaped neurological examinations: validity and factors that contribute to incorrect diagnoses. Movement Disorders 2002, 17(3), 513–517. [CrossRef]

- Post, B.; Merkus, M. P.; de Bie, R. M. A.; et al. Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale motor examination: are ratings of nurses, residents in neurology, and movement disorders specialists interchangeable? Movement Disorders 2005, 20(12), 1577–1584. [CrossRef]

- Vassar, S. D.; Bordelon, Y. M.; Hays, R. D.; et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of the motor unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Parkinson’s Disease 2012, 2012, 719167. [CrossRef]

- Abdolahi, A.; Scoglio, N.; Killoran, A.; et al. Potential reliability and validity of a modified version of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale that could be administered remotely. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2013, 19(2), 218–221. [CrossRef]

- Siderowf, A.; McDermott, M.; Kieburtz, K.; et al. Test-retest reliability of the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale in patients with early Parkinson’s disease: results from a multicenter clinical trial. Movement Disorders 2002, 17(4), 758–763. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, K. F.; Larsen, J. P.; Aarsland, D. Validation of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) section I as a screening and diagnostic instrument for apathy in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2008, 14(3), 183–186. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Justus, S.; Meluveettil, R.; et al. Validity of Montreal Cognitive Assessment in non-english speaking patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurology India 2015, 63(1), 63–67. [CrossRef]

- Hendershott, T. R.; Zhu, D.; Llanes, S.; et al. Comparative sensitivity of the MoCA and Mattis Dementia Rating Scale-2 in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2019, 34(2), 285–291. [CrossRef]

- Goetz, C. G.; Stebbins, G. T.; Tilley, B. C. Calibration of unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale scores to Movement Disorder Society-unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale scores. Movement Disorders 2012, 27(10), 1239–1242. [CrossRef]

- Aarsland, D.; Andersen, K.; Larsen, J. P.; et al. Prevalence and characteristics of dementia in Parkinson disease. Archives of Neurology 2003, 60(3), 387. [CrossRef]

- Ozdilek, B.; Kenangil, G. Validation of the Turkish Version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Scale (MoCA-TR) in patients with Parkinson’s disease. The Clinical Neuropsychologist 2014, 28(2), 333–343. [CrossRef]

- Kirsch-Darrow, L.; Zahodne, L. B.; Hass, C.; et al. How cautious should we be when assessing apathy with the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale? Movement Disorders 2009, 24(5), 684–688. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Martín, P.; Benito-León, J.; Alonso, F.; et al. Patients’, doctors’, and caregivers’ assessment of disability using the UPDRS-ADL section: are these ratings interchangeable? Movement Disorders 2003, 18(9), 985–992. [CrossRef]

- Lipsmeier, F.; Taylor, K. I.; Kilchenmann, T.; et al. Evaluation of smartphone-based testing to generate exploratory outcome measures in a phase 1 Parkinson’s disease clinical trial. Movement Disorders 2018, 33(8), 1287–1297. [CrossRef]

- Sulzer, P.; Becker, S.; Maetzler, W.; et al. Validation of a novel Montreal Cognitive Assessment scoring algorithm in non-demented Parkinson’s disease patients. Journal of Neurology 2018, 265(9), 1976–1984. [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.; Kasten, M.; May, M. T.; et al. Validation of conversion between mini-mental state examination and montreal cognitive assessment. Movement Disorders 2016, 31(4), 593–596. [CrossRef]

- Soares, T.; Vale, T. C.; Guedes, L. C.; et al. Validation of the Portuguese MDS-UPDRS: Challenges to obtain a scale applicable to different linguistic cultures. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice 2025, 12(1), 34–42. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P. D.; Ferris, S. H.; Cummings, J. L.; et al. Evaluation of dementia rating scales in Parkinson’s disease dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias 2010, 25(2), 142–148. [CrossRef]

- Nazem, S.; Siderowf, A. D.; Duda, J. E.; et al. Montreal cognitive assessment performance in patients with Parkinson’s disease with “Normal” global cognition according to mini-mental state examination score. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2009, 57(2), 304–308. [CrossRef]

- Nie, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. A pilot study of psychometric properties of the Beijing version of Montreal Cognitive Assessment in patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease in China. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2012, 19(11), 1497–1500. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Aldaajani, Z. F.; Aldughmi, M.; et al. Validation of the Arabic version of the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Movement Disorders 2022, 37(4), 826–841. [CrossRef]

- Raciti, L.; Nicoletti, A.; Mostile, G.; et al. Accuracy of MDS-UPDRS section IV for detecting motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease. Neurological Sciences 2019, 40(6), 1271–1273. [CrossRef]

- Metman, L. V.; Myre, B.; Verwey, N.; et al. Test-retest reliability of UPDRS-III, dyskinesia scales, and timed motor tests in patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease: an argument against multiple baseline assessments. Movement Disorders 2004, 19(9), 1079–1084. [CrossRef]

- Bezdicek, O.; Červenková, M.; Moore, T. M.; et al. Determining a short form Montreal Cognitive Assessment (s-MoCA) Czech version: Validity in mild cognitive impairment Parkinson’s disease and cross-cultural comparison. Assessment 2020, 27(8), 1960–1970. [CrossRef]

- Kleiner-Fisman, G.; Stern, M. B.; Fisman, D. N. Health-related quality of life in Parkinson disease: correlation between Health Utilities Index III and Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) in U.S. male veterans. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2010, 8(1), 91. [CrossRef]

- Starkstein, S. E.; Merello, M. The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale: validation study of the mentation, behavior, and mood section. Movement Disorders 2007, 22(15), 2156–2161. [CrossRef]

- Kasten, M.; Bruggemann, N.; Schmidt, A.; et al. Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2010, 75(5), 478; author reply 478–9. [CrossRef]

- Buck, P. O.; Wilson, R. E.; Seeberger, L. C.; et al. Examination of the UPDRS bradykinesia subscale: equivalence, reliability and validity. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease 2011, 1(3), 253–258. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Z.; Rajji, T. K.; Shulman, K. I. Brief cognitive screening instruments: an update. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2010, 25(2), 111–120. [CrossRef]

- Ruzafa-Valiente, E.; Fernández-Bobadilla, R.; García-Sánchez, C.; et al. Parkinson’s Disease--Cognitive Functional Rating Scale across different conditions and degrees of cognitive impairment. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2016, 361, 66–71. [CrossRef]

- Tumas, V.; Borges, V.; Ballalai-Ferraz, H.; et al. Some aspects of the validity of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for evaluating cognitive impairment in Brazilian patients with Parkinson’s disease. Dementia & Neuropsychologia 2016, 10(4), 333–338. [CrossRef]

- van Hilten, J. J.; van der Zwan, A. D.; Zwinderman, A. H.; et al. Rating impairment and disability in Parkinson’s disease: evaluation of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Movement Disorders 1994, 9(1), 84–88. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martin, P.; Chaudhuri, K. R.; Rojo-Abuin, J. M.; et al. Assessing the non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: MDS-UPDRS and NMS Scale. European Journal of Neurology 2015, 22(1), 37–43. [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, N.; Macleod, A. D.; Alves, G.; et al. Validation of a UPDRS-/MDS-UPDRS-based definition of functional dependency for Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2020, 76, 49–53. [CrossRef]

- Isella, V.; Mapelli, C.; Siri, C.; et al. Validation and attempts of revision of the MDS-recommended tests for the screening of Parkinson’s disease dementia. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2014, 20(1), 32–36. [CrossRef]

- Bugalho, P.; da Silva, J. A.; Cargaleiro, I.; et al. Psychiatric symptoms screening in the early stages of Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology 2012, 259(1), 124–131. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, S.; Simões, M. R.; Alves, L.; et al. Montreal cognitive assessment. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 2013, 27(1), 37–43. [CrossRef]

- Kremer, N. I.; Smid, A.; Lange, S. F.; et al. Supine MDS-UPDRS-III assessment: An explorative study. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12(9), 3108. [CrossRef]

- Goetz, C. G.; Tilley, B. C.; Shaftman, S. R.; et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Movement Disorders 2008, 23(15), 2129–2170. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Koh, S. B.; Kwon, K. Y.; et al. Validation study of the official Korean version of the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Journal of Clinical Neurology 2020, 16(4), 633–645. [CrossRef]

- Wissel, B. D.; Mitsi, G.; Dwivedi, A. K.; et al. Tablet-based application for objective measurement of motor fluctuations in Parkinson disease. Digital Biomarkers 2017, 1(2), 126–135. [CrossRef]

- Statucka, M.; Cherian, K.; Fasano, A.; et al. Multiculturalism: A challenge for cognitive screeners in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice 2021, 8(5), 733–742. [CrossRef]

- Stocchi, F.; Radicati, F. G.; Chaudhuri, K. R.; et al. The Parkinson’s Disease Composite Scale: results of the first validation study. European Journal of Neurology 2018, 25(3), 503–511. [CrossRef]

- Forjaz, M. J.; Ayala, A.; Testa, C. M.; et al. Proposing a Parkinson’s disease-specific tremor scale from the MDS-UPDRS. Movement Disorders 2015, 30(8), 1139–1143. [CrossRef]

- Hariz, G.-M.; Fredricks, A.; Stenmark-Persson, R.; et al. Blinded versus unblinded evaluations of motor scores in patients with Parkinson’s disease randomized to deep brain stimulation or best medical therapy. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice 2021, 8(2), 286–287. [CrossRef]

- Goetz, C. G.; Luo, S.; Wang, L.; et al. Handling missing values in the MDS-UPDRS. Movement Disorders 2015, 30(12), 1632–1638. [CrossRef]

- Morinan, G.; Hauser, R. A.; Schrag, A.; et al. Abbreviated MDS-UPDRS for remote monitoring in PD identified using exhaustive computational search. Parkinson’s Disease 2022, 2022, 2920255. [CrossRef]

- Regnault, A.; Boroojerdi, B.; Meunier, J.; et al. Does the MDS-UPDRS provide the precision to assess progression in early Parkinson’s disease? Learnings from the Parkinson’s progression marker initiative cohort. Journal of Neurology 2019, 266(8), 1927–1936. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, M. E.; Johnson, A. M.; Holmes, J. D.; et al. Predictive validity of the UPDRS postural stability score and the Functional Reach Test, when compared with ecologically valid reaching tasks. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2010, 16(6), 409–411. [CrossRef]

- Goetz, C. G.; Fahn, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Process, format, and clinimetric testing plan. Movement Disorders 2007, 22(1), 41–47. [CrossRef]

- Raciti, L.; Nicoletti, A.; Mostile, G.; et al. Validation of the UPDRS section IV for detection of motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2016, 27, 98–101. [CrossRef]

- Forjaz, M. J.; Martinez-Martin, P. Metric attributes of the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale 3.0 battery: part II, construct and content validity. Movement Disorders 2006, 21(11), 1892–1898. [CrossRef]

- Zitser, J.; Peretz, C.; Ber David, A.; et al. Validation of the Hebrew version of the Movement Disorder Society—unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2017, 45, 7–12. [CrossRef]

- Tosin, M. H. S.; Sanchez-Ferro, A.; Wu, R.-M.; et al. In-home remote assessment of the MDS-UPDRS part III: Multi-cultural development and validation of a guide for patients. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice 2024, 11(12), 1576–1581. [CrossRef]

- Benge, J. F.; Balsis, S.; Madeka, T.; et al. Factor structure of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment items in a sample with early Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2017, 41, 104–108. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, D. A.; Goetz, C. G.; Stebbins, G.; et al. Validation of the MDS-UPDRS Part I for nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2012, 27(1), 79–83. [CrossRef]

- Kenny, L.; Azizi, Z.; Moore, K.; et al. Inter-rater reliability of hand motor function assessment in Parkinson’s disease: Impact of clinician training. Clinical Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2024, 11, 100278. [CrossRef]

- de Deus Fonticoba, T.; Santos García, D.; Macías Arribí, M. Variabilidad en la exploración motora de la enfermedad de Parkinson entre el neurólogo experto en trastornos del movimiento y la enfermera especializada. Neurología (English Edition) 2019, 34(8), 520–526. [CrossRef]

- Dujardin, K.; Duhem, S.; Guerouaou, N.; et al. Validation in French of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment 5-Minute, a brief cognitive screening test for phone administration. Revue Neurologique 2021, 177(8), 972–979. [CrossRef]

- Tosin, M. H. S.; Stebbins, G. T.; Comella, C.; et al. Does MDS-UPDRS provide greater sensitivity to mild disease than UPDRS in DE Novo Parkinson’s disease? Movement Disorders Clinical Practice 2021, 8(7), 1092–1099. [CrossRef]

- De Deus Fonticoba, T.; Santos García, D.; Macías Arribí, M. Inter-rater variability in motor function assessment in Parkinson’s disease between experts in movement disorders and nurses specialising in PD management. Neurología (English Edition) 2019, 34(8), 520–526. [CrossRef]

- Kletzel, S. L.; Hernandez, J. M.; Miskiel, E. F.; et al. Evaluating the performance of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in early stage Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2017, 37, 58–64. [CrossRef]

- Gill, D. J.; Freshman, A.; Blender, J. A.; et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment as a screening tool for cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2008, 23(7), 1043–1046. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Martín, P.; Gil-Nagel, A.; Gracia, L. M.; et al. Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale characteristics and structure. The Cooperative Multicentric Group. Movement Disorders 1994, 9(1), 76–83. [CrossRef]

- Gasser, A.-I.; Calabrese, P.; Kalbe, E.; et al. Cognitive screening in Parkinson’s disease: Comparison of the Parkinson Neuropsychometric Dementia Assessment (PANDA) with 3 other short scales. Revue Neurologique 2016, 172(2), 138–145. [CrossRef]

- D’Iorio, A.; Aiello, E. N.; Amboni, M.; et al. Validity and diagnostics of the Italian version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in non-demented Parkinson’s disease patients. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 2023, 35(10), 2157–2163. [CrossRef]

- Evers, L. J. W.; Krijthe, J. H.; Meinders, M. J.; et al. Measuring Parkinson’s disease over time: The real-world within-subject reliability of the MDS-UPDRS. Movement Disorders 2019, 34(10), 1480–1487. [CrossRef]

- Louis, E. D.; Lynch, T.; Marder, K.; et al. Reliability of patient completion of the historical section of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Movement Disorders 1996, 11(2), 185–192. [CrossRef]

- Fiorenzato, E.; Weis, L.; Falup-Pecurariu, C.; et al. MoCA vs. MMSE sensitivity as screening instruments of cognitive impairment in PD, MSA and PSP patients. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2016, 22, e59–e60. [CrossRef]

| Region | Publications (n) | Percentage (%) | Income Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe (HIC) | 48 | 44.0 | High |

| North America (HIC) | 39 | 35.8 | High |

| Asia (HIC) | 9 | 8.3 | High |

| Asia (LMIC) | 4 | 3.7 | LMIC |

| Oceania (HIC) | 3 | 2.8 | High |

| South America (LMIC) | 3 | 2.8 | LMIC |

| Africa (LMIC) | 2 | 1.8 | LMIC |

| North America (LMIC) | 1 | 0.9 | LMIC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).