1. Introduction

Rising demands in green energy generation, electric vehicles [

1], transportation, construction, consumer electronics and industrial automation are bolstering the need for high performance, robust and high quality motors. Direct Current (DC) motors, even though they are one of the oldest electric motor designs, are still more than relevant in modern industry. Their market is experiencing steady growth, attributed to a broad range of application areas such as as robotics, military, spacecrafts [

2], medical equipment, agriculture [

3], unmanned monitoring systems [

4]. The global push towards sustainable practices combined with the rising prevalence of electric vehicles are influencing the adoption of DC motors. Their main advantages in comparison with other types of motors are; small noise operation, low cost, better characteristics of speed and torque, good controllability, fast response in dynamic changes, high power-to-weight ratio, no requirement for current excitation and adequate performance for their cost.

Yet open loop method is being used for controlling brushed and brushless DC motors. Despite the simplicity of this approach, open loop systems lack of accuracy especially in dynamic or unpredictable applications. Another major disadvantage is the susceptibility to external factors. This vulnerability to variations and disturbances in load conditions leads to decreased system performance. The lack of feedback limits adaptability, since open loop systems are not adaptable to changing conditions. Meanwhile, wear and tear can not get compensated, hence manual tuning is required. Therefore, the aforementioned reasons in recent years have draw attention to closed loop control [

5]. The presence of feedback loop provides enhanced precision, accuracy and adaptability to varying conditions. Disturbances can get compensated and stable performance is maintained, even in dynamic environments. Additionally, robustness is achieved, which is essential in robotics, automation, electric vehicles, medical equipment, computer numerical control machines. Sensorless DC motor controllers offer simplicity and cost-effectiveness [

6,

7]. These controllers rely on motor’s back electromotive force (EMF) or other internal characteristics to estimate the position of the rotor, i.e. without using external sensors. However, sensorless controllers do not perform well at low speeds. The motor appears “jumpy” or “jittery”, which is also known as “cogging”. Additionally, during rapid load changes, the lack of sensor results in less precise control. In sensored operation, motor operation is smooth, while stuttering and vibrations are significantly reduced. Sensor feedback enhances stability, leading to better response to load variations. Due to these reasons, over the last few years a greater focus has been placed on sensored closed loop controllers [

8,

9]. Reliable performance is ensured, while accurate and precise control may be achieved even at low speeds.

Traditionally, the most common control methods, used in the majority of studies, are the PI and PID controllers [

10,

11,

12]. These conventional controllers are well known as common techniques for non-linear systems control, mainly due to their simple architecture and the easily managed control algorithm. However, PID controllers are sensitive to measurements errors and noise, causing crucial performance deterioration, instabilities and undesired oscillations [

13]. Additionally, derivative filtering is proposed in [

14,

15,

16], significantly enhancing robustness and improving stability. Parallel and coupling PID controllers were proposed in [

17], while in [

18] an approach using backstepping sliding mode control was demonstrated. Observer-based non linear controllers have also been employed in [

19,

20], providing immunity against measurement noise.

In recent years, much research has been performed on artificial intelligence (AI) control methods. Embedded artificial intelligence is impacting the future of every industry and every human being. Autonomous cars, robots, virtual nursing assistants, diagnosis of diseases, virtual tutors in education and customer services are some current and future applications. The main advantage of AI controllers is their robustness [

21], being capable of overcoming the uncertainty of conventional control methods and providing better system response [

22,

23]. Commonly implemented methods use structures based on neural networks, fuzzy logic, genetic algorithms or even hybrid approaches. Fuzzy logic controllers (FLC) for DC motor control has been employed in [

24,

25], towards improved controller’s performance. The problem of disturbances has been addressed in [

26]. FLC’s superiority over conventional PID controllers have been experimentally validated in [

27]. Novel neural network controllers were examined in [

28,

29,

30], while recently [

22,

31] genetic algorithm approaches were demonstrated. The robustness of neuro-adaptive controller was experimentally proved in [

32]. In [

33] a hybrid controller, consisting of a parallel combination of sliding mode and neurofuzzy controllers, was proposed.

Fuzzy logic controllers execute the control process by utilizing linguistic expressions along with the processes of fuzzification, rule base, and defuzzification [

34]. These controllers provide an excellent way of dealing with imprecision and nonlinearity in complex control situations [

35]. Despite the apparent advantages of Type-1 (IT1) FLC’s, it has been proved that they are not capable of fully handling the impact of uncertainties. [

36,

37]. In recent studies interval Type-2 (IT2) FLC’s outperformed IT1-FLC’s [

38,

39,

40] mainly attributed to the crisp values of their membership grades of IT1-FLC’s. While the membership functions of Type-1 FLCs are certain, the membership functions of Type-2 FLCs are fuzzy themselves. Type-2 FLC’s have primary membership functions (PMF’s), which might be any value in the interval [0, 1]. Moreover, in PMF’s there is a secondary membership functions (SMF), defining the probability of PMF’s. The latter leads to an increased computational burden and as a result zero or unity SMF’s are developed. The combination of a conventional PID and a fuzzy system led to the creation of Fuzzy PID (FPID) [

41,

42,

43]. Adaptive fuzzy controllers were presented in [

44,

45], providing robustness and improved control performance. In this paper, a composition of an interval Type-2 FLC and a PID controller is proposed to manage uncertainties in controlling the DC micro-motor under study. PID controller parameters are dynamically set by fuzzy sets, improving performance, robustness and systems response.

In recent literature numerous efforts in closed loop DC motor control development have been conducted, either by means of simulations [

46,

47,

48], or in experimental configurations [

49,

50,

51]. The former approaches, even though valuable to prove the conceptual design, use either low-cost development boards, which have hardware constraints and especially memory limitations, or expensive FPGA development boards which are considered as “overkill” for these type of applications. On the other hand, modern families of microcontrollers (e.g. like STM32 provided by STMicroelectronics), keep pace with emerging trends and remain at the forefront of embedded systems development, providing an ideal balance between cost, performance, scalability and dependability as presented in [

52,

53,

54].

Although, a few control algorithms applied on experimental setup have been suggested, the amount of research analyzing practical difficulties and limitations either in hardware or software level, while proposing a clear methodology and design optimization techniques, is limited. Considering cases, in which readymade solutions are costly or insufficient due to custom application specifications, a low cost, fully flexible, customizable and parametrised prototype should be build. Based on the aforementioned factors, the key contributions of this paper are:

Present refined hardware-in-the-loop approach, integrating real-time PSO directly on STM32 microcontroller, with comprehensive hardware-software co-design analysis highlighting constraints and trade-offs.

Develop novel optimized hybrid FT2-PID controller tailored for embedded platforms.

Validate the proposed FT2-PID controller against PI, PID, and PIDF controllers showing significantly faster settling times and reduced overshoot at higher reference speeds.r

Address critical hardware limitations, including processing time, memory constraints, and real-time execution challenges, being overlooked in theoretical studies.

It should be highlighted that -to the authors’ knowledge extend- in research literature, similar efforts offering valuable technical competence are not found. In this paper, an adaptive IT2-PID controller is especially designed and experimentally implemented for coreless DC micro-motor (though the procedure can be easily applied to other DC motor types). Prioritizing cost and simplicity, hardware limitations and components selection are detaily presented. This proposed controller is being compared with PI, PID and PID with D filtering controllers, all being tuned using embedded real time PSO algorithm [

55]. Discrete reference speed cases are being investigated not only to present the robustness of the controller under investigation but also to compare the microcontroller’s performance and resources needed. Emphasis is being given to microcontroller’s system-level characteristics and to hardware considerations for the prototype design. Parameters such as pulse width modulation (PWM) bit resolution, interrupt time selection for speed measurements, encoder’s resolution, experimental speed data filtering are also examined and pointed out. Finally, the design and the level of goodness of a microcontroller embedded adaptive IT2-PID is discussed.

The structure of this paper is as follows. A brief theory of DC micro-motor is presented in Section II, while the control strategies are discussed in Section III. Prototype design and development is described in Section IV. Section V presents the software development considering hardware limitations. The derived results are reported and commented in Section VI and ultimately Section VII serves to conclude the work.

2. Brief DC Micro-Motor Theory Overview

DC micro-motors represent a class of miniature motors that offer significant advantages over conventional DC motors, particularly in applications requiring compact size, high efficiency, and precise control. These motors are typically characterized by their small dimensions, with diameters ranging from a few millimeters to several centimeters, making them ideal for use in miniature devices and systems. They are known for their lightweight construction, which is often achieved by using specialized materials such as precious metals for the commutator and brush assembly, including platinum, silver, and gold. This contributes to reduced wear and tear, increased durability, and improved performance in high-speed applications. The design of these motors often incorporates permanent magnets in the stator, and their compact rotor design reduces energy losses while enhancing torque production. The small size of DC micro-motors allows for precise control over speed and positioning, making them particularly suitable for applications in robotics, medical devices, and embedded systems where space and efficiency are critical.

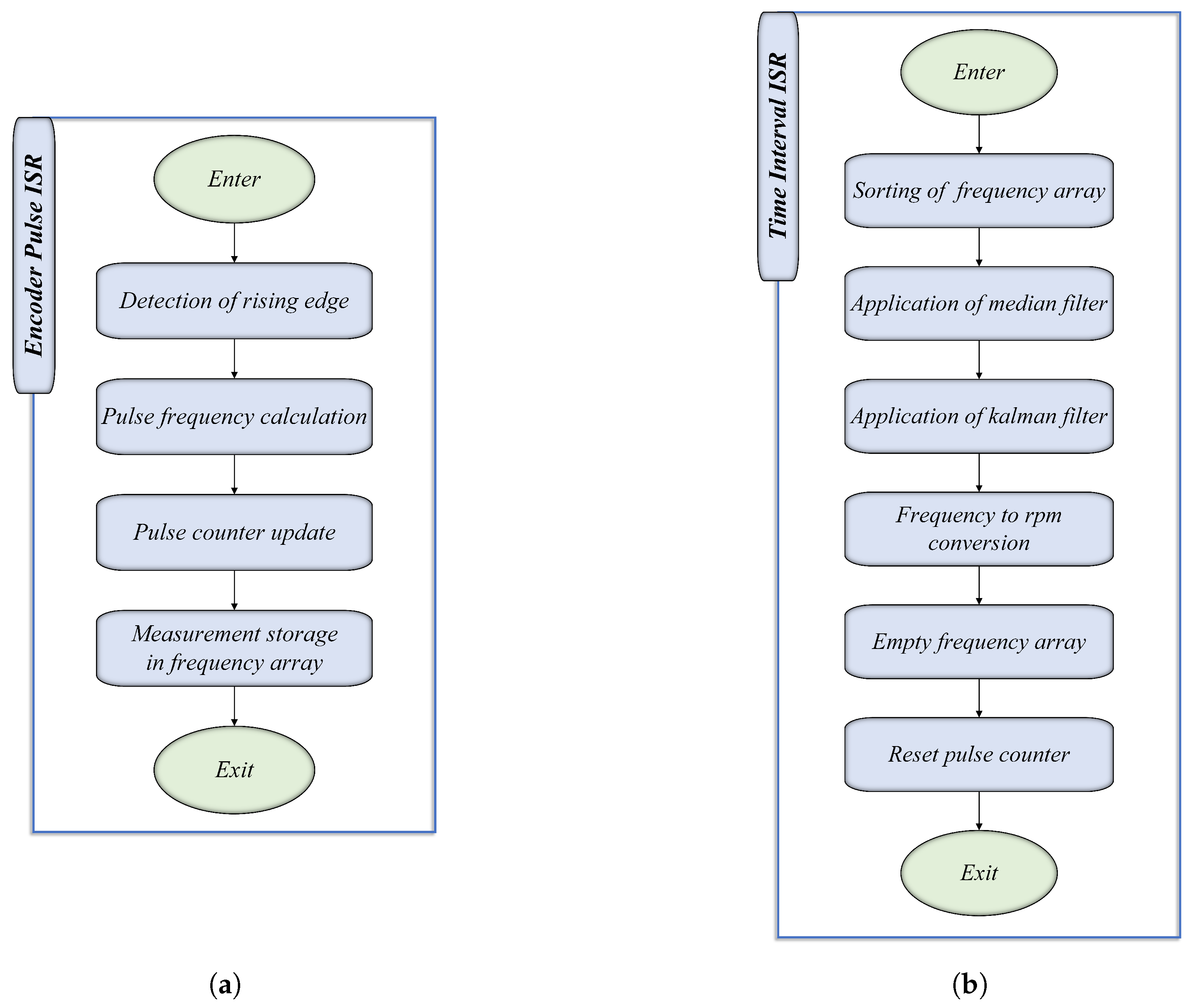

Figure 1 presents the equivalent circuit and the investigated micro-motor.

The DC micro-motor under study, along with its equivalent circuit, is shown in

Figure 1. The armature winding is characterized by its winding resistance (

) and inductance (

), where the supply voltage (

) is introduced. The back electromotive force (

) induced in the armature winding arises from the interplay of the armature’s motion with the magnetic field. As the armature rotates within the magnetic field, it cuts through magnetic flux lines, which induces a voltage that opposes the applied voltage. This back electromotive force maintains a direct proportionality to the magnetic flux (

) and to the angular velocity (

), which can be expressed as the rate of change in shaft position (

).

The rotational speed (

), expressed in revolutions per minute (rpm), is related to the angular velocity (

) using the equation below:

The back-emf coefficient (

) is a constant that represents the proportionality between the motor’s rotational speed and the induced electromotive force, reflecting the motor’s design and the strength of its magnetic field. This constant defines the relationship between the motor’s angular velocity (

) and the back electromotive force (

) generated. The back-emf is directly proportional to the motor’s rotational speed and the relationship is described by the following equation:

The armature current (

) is determined by the applied supply voltage (

), the armature winding resistance (

), its inductance (

), and the back-emf (

) generated. The total applied supply voltage must counteract the resistive losses in the armature winding (

), the inductive voltage drop caused by the time rate of change of the armature current (

), and the back-emf. This relationship can be expressed as follows:

The back-emf reflects the conversion of electrical energy into mechanical energy, with its magnitude being directly influenced by the motor’s speed. The magnetic flux (

) is related to the coefficient

, which governs the conversion between the armature current and the electromagnetic torque (

) generated by the motor. The mechanical dynamics of the motor are described by the following set of equations, where

is the viscous damping coefficient,

denotes the moment of inertia of the rotor, and

represents the load torque:

By combining the electrical and mechanical equations, the following differential equations are obtained, which fully describe the system dynamics:

Upon applying the Laplace transform to Equations (

7) and (

8), the transfer function of the motor is derived, which relates the motor speed to the applied input voltage:

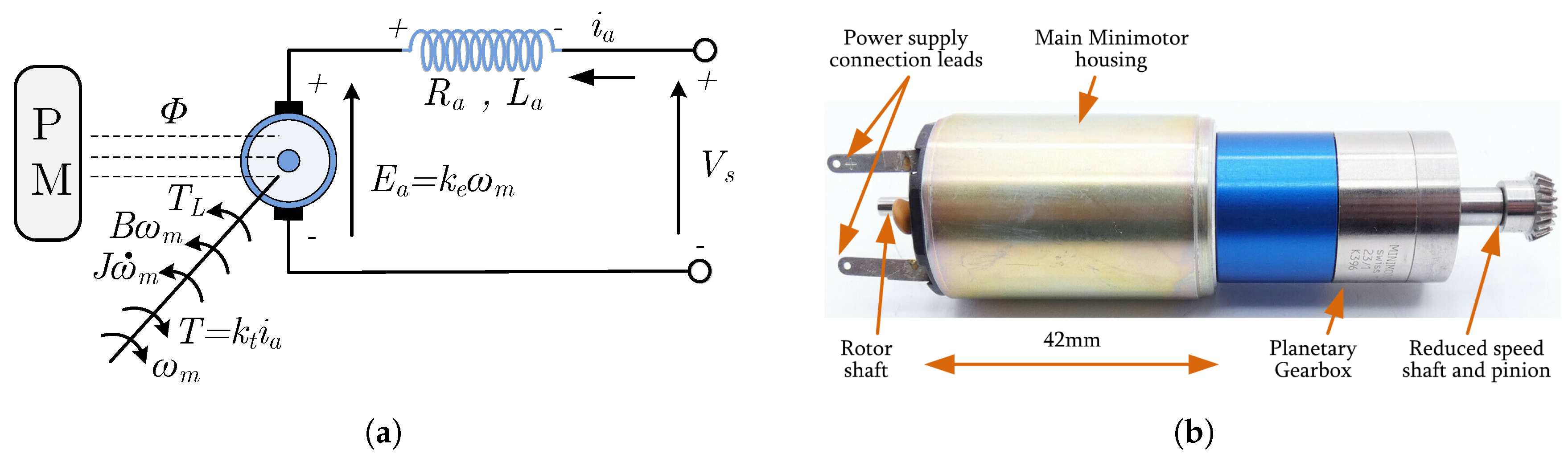

The transfer function is commonly depicted in block diagram form, as illustrated in

Figure 2. In this diagram, the supply voltage (

) serves as the input, while the micro-motor’s rotational speed (

) serves as the output. Accurate modeling of the motor necessitates identifying six parameters:

,

,

,

,

, and

. The specific parameter values for the DC micro-motor utilized in this work are provided in

Table A1.

3. Control Strategies

3.1. Closed-Loop Control for Micromotor Speed Regulation

The objective of the controller under study is to regulate the DC micro-motor speed to a specified reference value by employing a closed-loop negative feedback control system. In the context of this study, the controller employs two inputs to determine the control action: the error and the change in error. The error is expressed as the difference between the measured rotational speed (

) and the reference rotational speed (

).

Respectively, the change in error, which describes how the error changes over time, is calculated as:

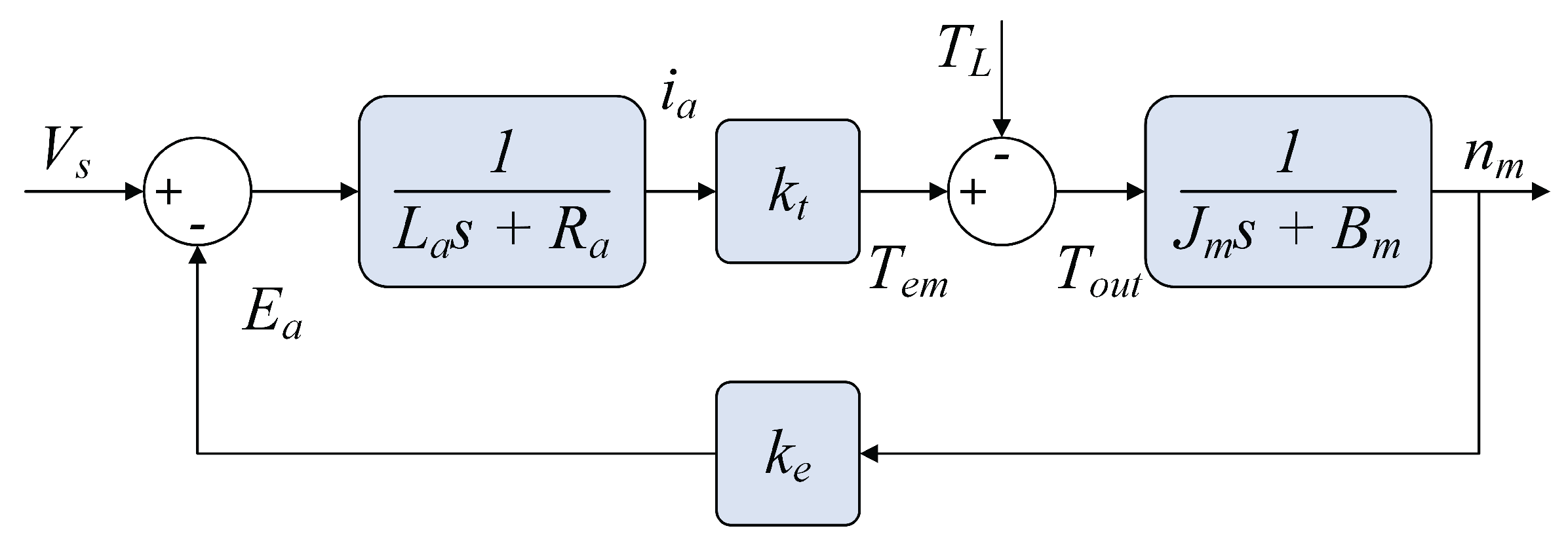

The controller processes the error signal to generate the control signal . To interface with the DC micro-motor, a converter is incorporated between the controller and the motor, translating the control signal into the appropriate input voltage . This converter reconciles the voltage and current mismatches, ensuring the control signals are properly scaled to to meet the power requirements and drive the micro-motor. The negative feedback structure dynamically adjusts the control action based on the deviation between the reference and measured micro-motor speed, thereby minimizing the error signal . This closed-loop mechanism compensates for external disturbances, system nonlinearities, and load variations, ensuring accurate and stable speed regulation. Additionally, the feedback system enhances the motor’s response to dynamic changes in speed, enhancing steady-state accuracy and robustness against fluctuations.

Figure 3 presents the schematic of the negative feedback control loop used. The diagram illustrates the interconnections between key system components, including the controller, converter, DC micro-motor, and speed sensor. This closed-loop configuration ensures motor speed control by continuously comparing the reference speed with the measured speed.

3.2. PI, PID, and PIDF Controllers

In industrial applications, proportional integral controllers (PI) are among the most widely adopted control strategies due to their simplicity and effectiveness in reducing steady-state error. The PI controller works by combining two fundamental control actions: proportional control and integral control. The proportional term addresses the current error in the system by generating an output directly proportional to the current error. The error signal is multiplied by a constant,

, known as the proportional gain. This relationship is given by:

The term

represents the Laplace transform of the error signal

. While the proportional term effectively reduces error in the short term, it does not address persistent, steady-state errors that may arise. To tackle this issue, the integral term is introduced. The integral action accumulates the error over time and provides corrective action to eliminate any steady-state offset. This action is represented as:

When combined, the overall output of the PI controller,

, is given by:

This combination of proportional and integral terms delivers balance between quick responsiveness and sustained accuracy. The PI controller is particularly effective in systems where the error changes slowly or remains constant over time. However, the PI controller faces limitations in systems where the error changes rapidly. Since it lacks a term that responds to the rate of change of the error, the controller may exhibit slower response times, higher overshoot, and longer settling times in dynamic systems. To enhance the performance of the PI controller in more dynamic systems, the proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controller is introduced. The PID controller builds on the PI controller by incorporating a derivative term that responds to the rate of change of the error. This term helps the controller anticipate future error trends, allowing it to adjust more quickly and precisely to changes in the system. The derivative term contributes to system stability by limiting overshoot and advancing transient response. It is mathematically expressed as:

Thus, the output of the PID controller becomes:

Conventional PID controllers frequently struggle to handle the intricate dynamics of DC motors, leading suboptimal performance [

56]. While the derivative term improves the system’s responsiveness and stability, it can also amplify high-frequency noise, resulting in oscillations or unwanted vibrations in the control signal. To address these challenges, a derivative filter can be introduced. This filter smooths the high-frequency components of the derivative term, reducing the controller’s sensitivity to noise and mitigating undesirable oscillations. The resulting controller, known as the Proportional-Integral-Derivative-Filter controller (PIDF), is mathematically expressed as:

Here,

N represents the filter coefficient, which determines how much high-frequency noise is filtered out from the derivative term in the PIDF controller. The filter is typically employed to avoid undesirable oscillations or instability caused by noise amplification in the derivative term. The value of

N creates a trade-off between noise suppression and the controller’s responsiveness.

Table 1 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of selecting small or large values of

N.

The PIDF controller is particularly effective in DC motor control applications where precise speed regulation is required despite fluctuations in load or noise in the feedback signal. By incorporating a derivative filter, it suppresses high-frequency noise that can otherwise destabilize the control loop. This controller strikes a balance between rapid error correction and maintaining stability, enabling the controller to achieve accurate motor operation while adapting to changes in reference speed or system disturbances.

Figure 4 shows the structure of the examined controllers.

3.3. FT2-PID Controller

Fuzzy logic is a computational model based on approximate reasoning rather than fixed, exact rules. It manages uncertainty and imprecision, making it effective in complex control systems. Unlike traditional controllers that require precise mathematical models, fuzzy logic handles ambiguity, imprecise measurements, and noisy data. Using linguistic variables and fuzzy rules, it adapts well to systems with nonlinearities and disturbances, where conventional methods like PID may falter.

In essence, fuzzy logic control operates through three key stages: fuzzification, inference, and defuzzification. During fuzzification, precise input values are transformed into fuzzy representations using membership functions (MFs) that describe the degree of membership within a given range, typically [0, 1]. Complete membership in a fuzzy set is denoted by 1, while 0 reflects no membership. In the inference stage, a rule base consisting of conditional relationships is applied to the fuzzified inputs. These relationships define how the inputs correspond to the outputs, with the inference engine processing them to generate the corresponding fuzzy outputs. In this work, the process follows the Mamdani fuzzy inference system, which combines these rules to derive fuzzy control actions. Finally, in the defuzzification phase, the fuzzy outputs are translated into a precise, crisp value, which serves as the final control signal, enabling accurate system control.

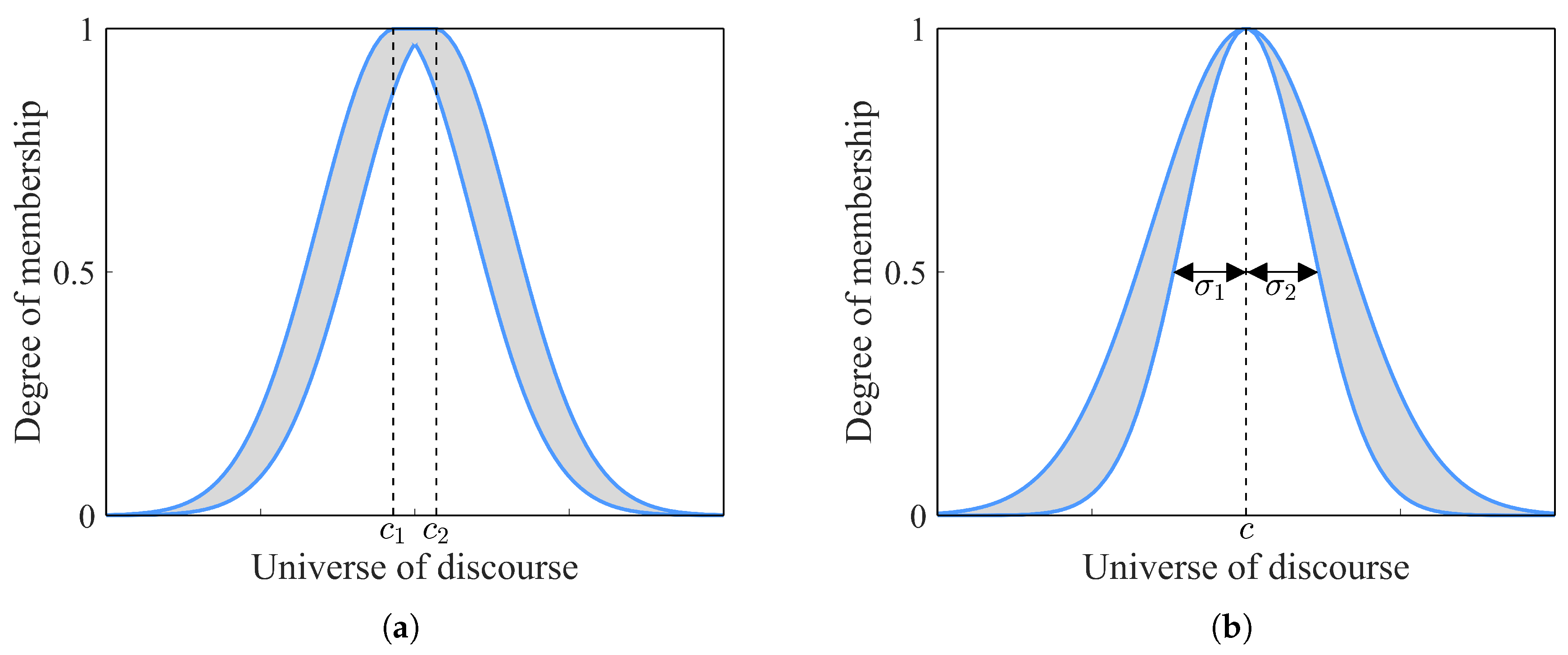

Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Logic (IT2-FL) extends traditional fuzzy logic by introducing an additional dimension of uncertainty within its membership functions. While Type-1 fuzzy logic employs precise membership grades to map input values to fuzzy sets, IT2-FL utilizes interval-valued membership functions to account for uncertainties inherent in real-world data. This framework captures both the primary membership values and their associated uncertainties, thereby enabling a more nuanced representation of vagueness and imprecision.

Uncertainty in these sets is characterized using key parameters. The mean (

) represents the central value of the membership function, serving as the core membership value around which the fuzzy set’s membership degrees vary. The standard deviation (

) quantifies the spread of membership values around the mean, with larger

indicating greater uncertainty. The delta (

) represents the uncertainty interval, describing the deviation in the mean membership value.

Figure 5 shows IT2 gaussian membership functions, with the left image representing uncertainty in the mean and the right image depicting uncertainty in the standard deviation.

In this work uncertainty in the mean is used, with the centers of each membership function expressed as:

where

and

represent the centers of each MF,

is the mean, and

is the uncertainty in the mean. The standard deviation

is assumed to remain the same across both membership functions. The membership function of an interval type-2 fuzzy set defined over the input domain

F and output domain

G can be expressed as:

where

and

are secondary membership intervals that account for the uncertainty in the primary memberships

and

, respectively. These fuzzy sets are defined over the domains

F and

G, which represent the input and output spaces, respectively. The relationship between inputs and outputs is governed by a set of fuzzy rules, commonly represented as

. A typical rule is formulated as:

where

are interval type-2 fuzzy sets associated with the inputs, and

represents the output fuzzy set. These rules form a rule base that enables the inference process, ultimately producing a fuzzy output that is defuzzified into a crisp control signal.

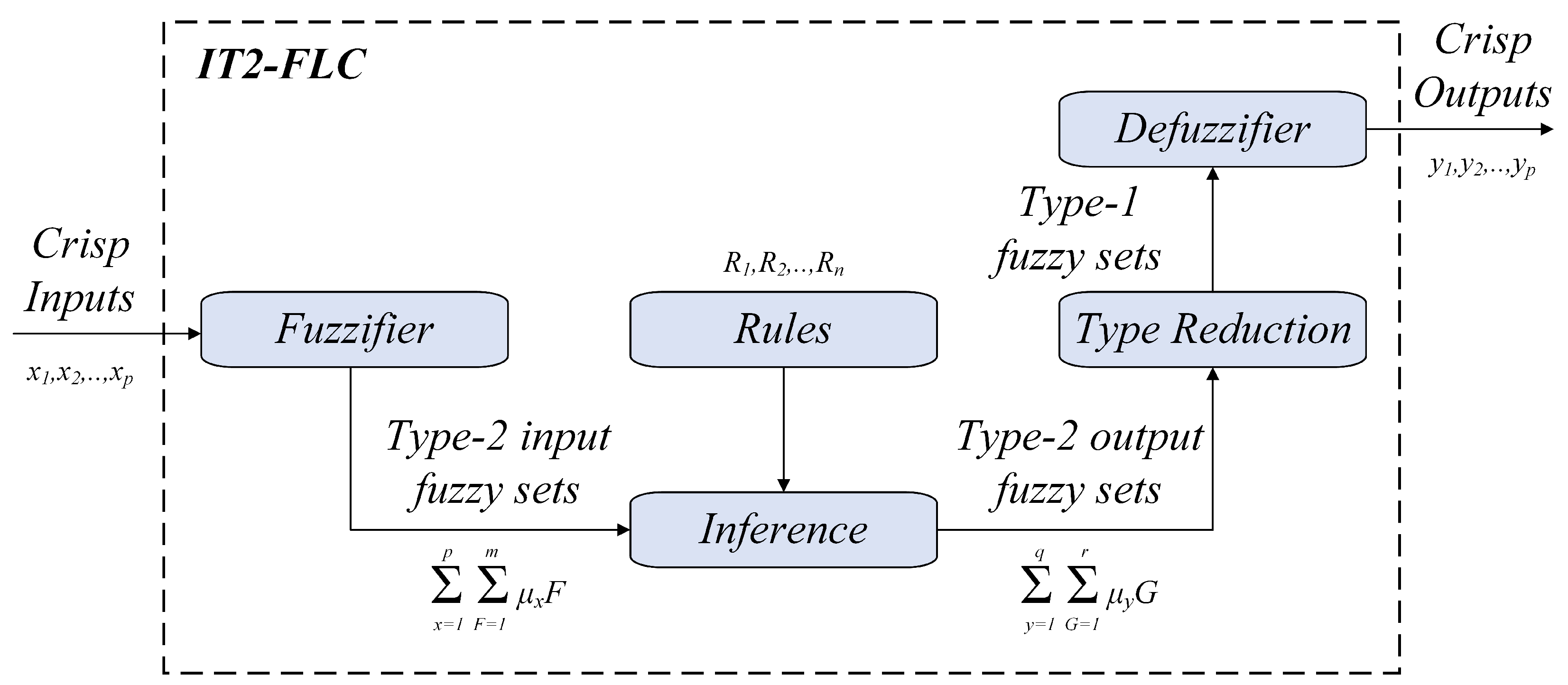

The IT2-FLC structure is illustrated in

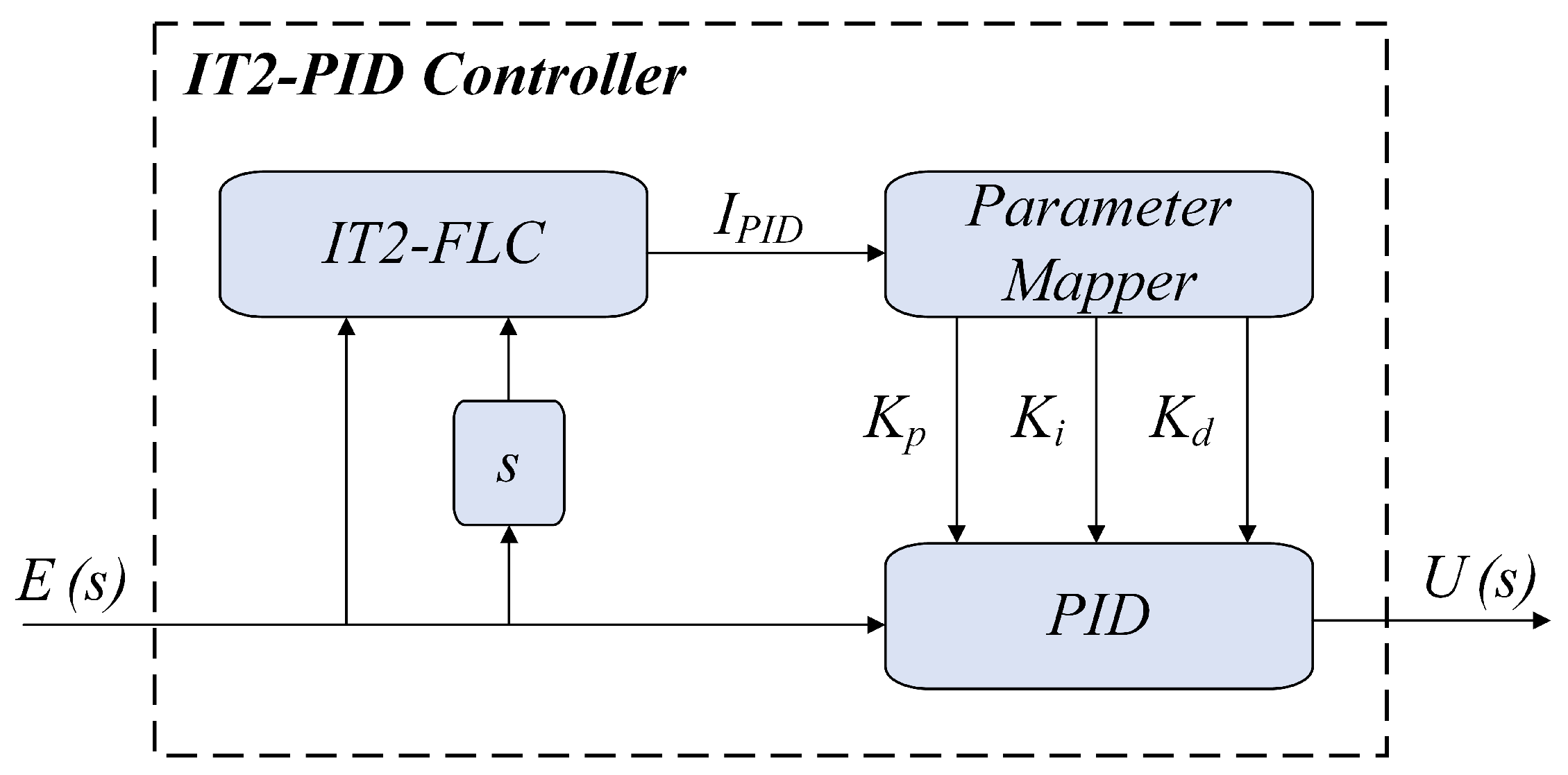

Figure 6. The diagram demonstrates the process by which crisp inputs are transformed into fuzzy values, processed through the inference system, and subsequently converted back into crisp outputs. The arrows illustrate the transfer of information across these stages. In this study, an Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Logic-based PID (IT2-PID) controller is implemented, integrating the adaptive capabilities of Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Logic (IT2-FL) with the proven effectiveness of the PID control framework. The IT2-PID controller dynamically adjusts the proportional (

), integral (

), and derivative (

) gains through a Type-2 fuzzy inference system. This enables real-time adaptation of the control parameters to varying system conditions, ensuring robust and precise control. The proposed structure of the IT2-PID controller is depicted in

Figure 7.

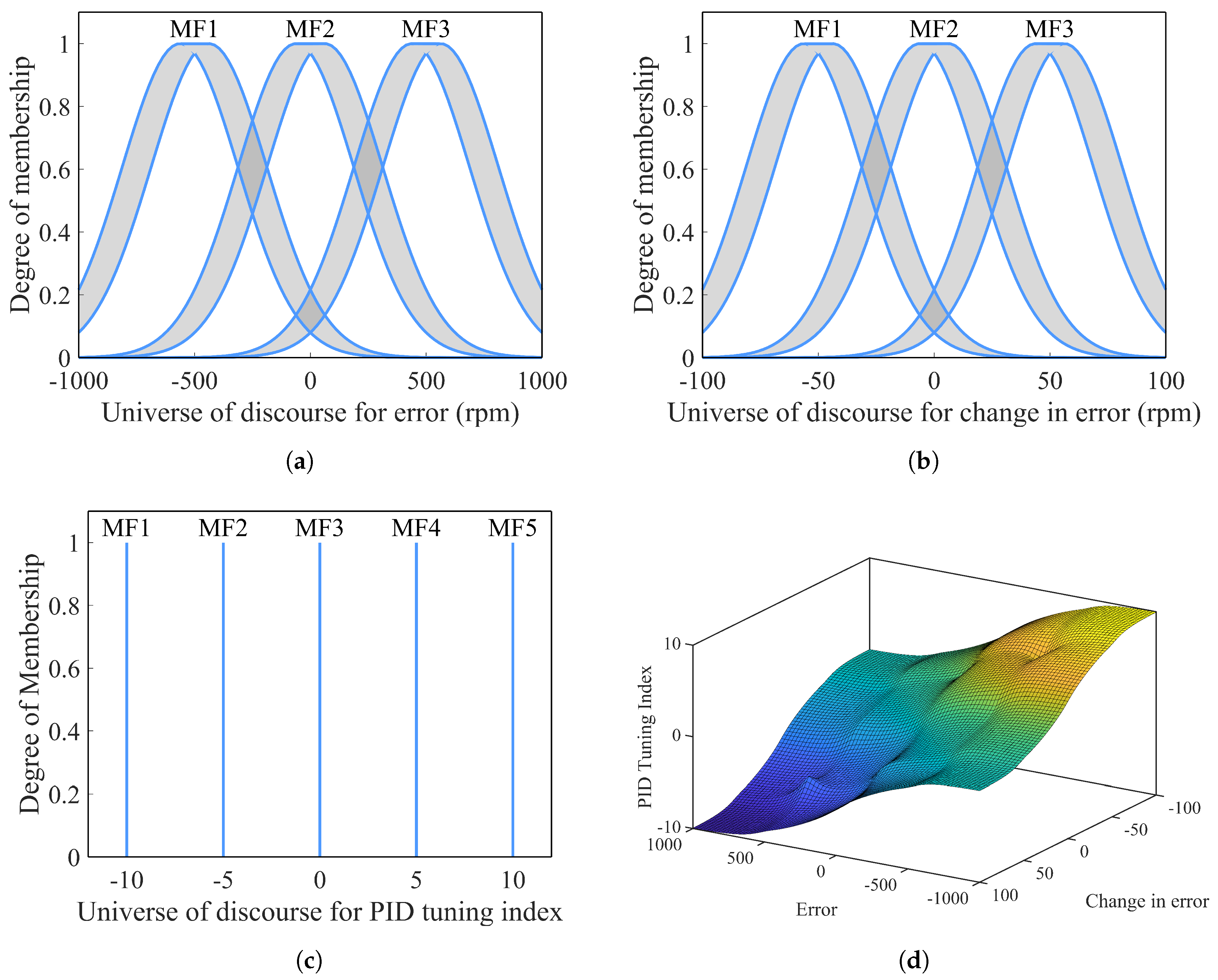

The proposed IT2-FLC accepts two inputs: the error (

e) and the change in error (

). The output of the controller is a scalar value referred as the PID Tuning Index (

). The standard deviation (

) is set to 250 for the error and 25 for the change in error MFs, while the delta (

) values are 62.5 and 6.25, respectively. MFs and the inference system surface are depicted in

Figure 8. The rule base governing the IT2-FLC is presented in

Table 2.

Since

lies within the range

, parameter mapping is required to determine the appropriate PID gains (

,

, and

). The absolute value of the PID Tuning Index (

) is utilized. This ensures that the tuning decisions depend only on the magnitude of the index, independent of its sign. The absolute value

is divided into predefined intervals, with each interval corresponding to a unique set of PID parameters. The selection of parameter sets is performed dynamically based on the magnitude of

.

Table 3 presents the mapping framework between the intervals of

and the corresponding PID parameter sets. Tuned parameter values will be presented in Section VI. The resulting parameters are stored and dynamically selected at runtime.

7. Conclusions

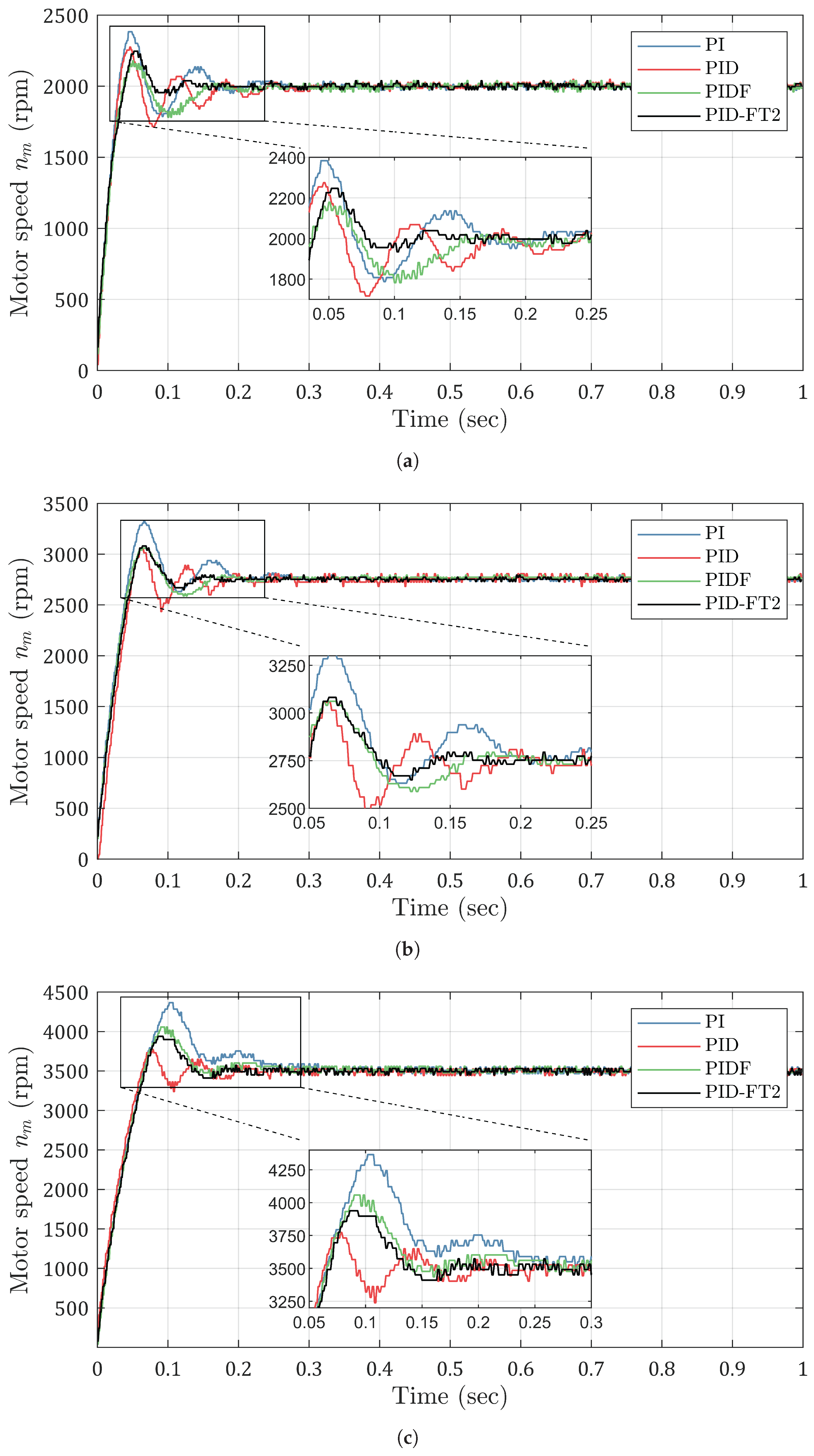

In this paper, the experimental implementation of speed control for a coreless DC motor using a low-cost microcontroller was presented. The prototype design methodology was thoroughly analyzed, addressing critical limitations and ensuring practical feasibility. An adaptive FT2-PID controller was evaluated against conventional PI, PID, and PIDF controllers, with comprehensive performance metrics, including rise time, settling time, and overshoot, used for comparison. The results demonstrate that the adaptive FT2-PID controller consistently outperforms the conventional controllers across all test cases. It exhibits superior dynamic performance with faster settling times, reduced overshoots, and robust speed tracking capabilities. Notably, the FT2-PID controller achieves these results despite the inherent challenges of implementing advanced control strategies on resource-constrained microcontroller platforms.

The performance of the FT2-PID controller, when compared to traditional PI, PID, and PIDF controllers, highlights significant advantages in terms of response speed and stability. Specifically, in terms of settling time, the FT2-PID consistently outperformed the other controllers across different reference speeds. At 2000 rpm, the FT2-PID controller achieved a settling time of 104 ms, which is 28.3% faster than the PIDF controller at 145 ms and 56.7% faster than the PI controller at 240 ms. This superior performance is especially critical in applications where fast and stable motor response is required, such as in robotics or automation systems. The FT2-PID controller also demonstrated lower overshoot at higher reference speeds, further underscoring its effectiveness in ensuring stable operation, with overshoot values remaining consistently lower than the PI controller, which exhibited significant fluctuations, especially at higher speeds. These results underscore the potential of the FT2-PID controller in applications requiring precise and reliable speed control of DC micromotors.

For future work, further optimization of the FT2-PID algorithm could be explored to reduce its computational burden without compromising its control efficacy. Techniques such as approximate inference methods or precomputed rule bases may strike a balance between advanced control capabilities and efficient resource utilization. Additionally, memory optimization techniques tailored for fuzzy type-2 controllers could be investigated to minimize memory usage while maintaining system performance and efficiency. Such advancements would enable broader applicability of FT2-PID controllers in embedded systems with stringent resource constraints. Furthermore, comparative studies with other modern control approaches, such as adaptive neural controllers or model predictive controllers, could provide deeper insights into the strengths and limitations of the FT2-PID control method. By addressing these future directions, the effectiveness and practicality of FT2-PID controllers can be further enhanced, paving the way for their application in more complex and demanding control scenarios.

Figure 1.

DC micro-motor: (a) Equivalent circuit and (b) Investigated micro-motor.

Figure 1.

DC micro-motor: (a) Equivalent circuit and (b) Investigated micro-motor.

Figure 2.

Block diagram illustrating closed-loop architecture for DC micro-motor speed control.

Figure 2.

Block diagram illustrating closed-loop architecture for DC micro-motor speed control.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the negative feedback control loop for regulating DC micro-motor’s speed.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the negative feedback control loop for regulating DC micro-motor’s speed.

Figure 4.

Structure of the controllers under study: (a)PI (b) PID (c) PIDF.

Figure 4.

Structure of the controllers under study: (a)PI (b) PID (c) PIDF.

Figure 5.

Gaussian IT2 MFs with: (a) uncertainty in the mean (b) uncertainty in the standard deviation.

Figure 5.

Gaussian IT2 MFs with: (a) uncertainty in the mean (b) uncertainty in the standard deviation.

Figure 6.

Block diagram of the IT2-FLC structure.

Figure 6.

Block diagram of the IT2-FLC structure.

Figure 7.

Proposed IT2-PID controller structure.

Figure 7.

Proposed IT2-PID controller structure.

Figure 8.

Membership Functions of the IT2-FLC: (a) error, (b) change in error, (c) PID tuning index, and (d) the control surface of the inference system.

Figure 8.

Membership Functions of the IT2-FLC: (a) error, (b) change in error, (c) PID tuning index, and (d) the control surface of the inference system.

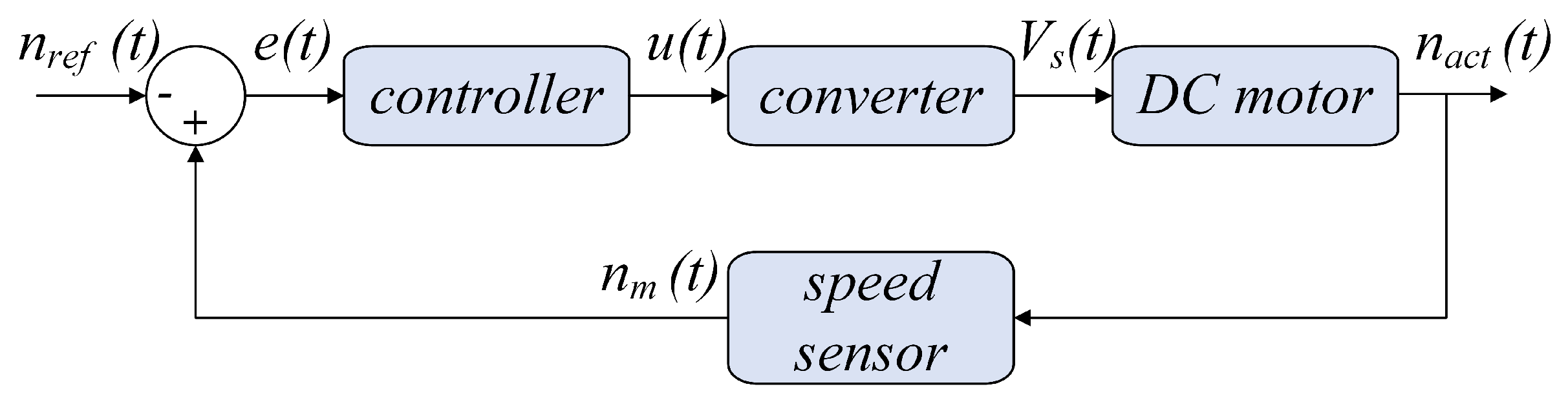

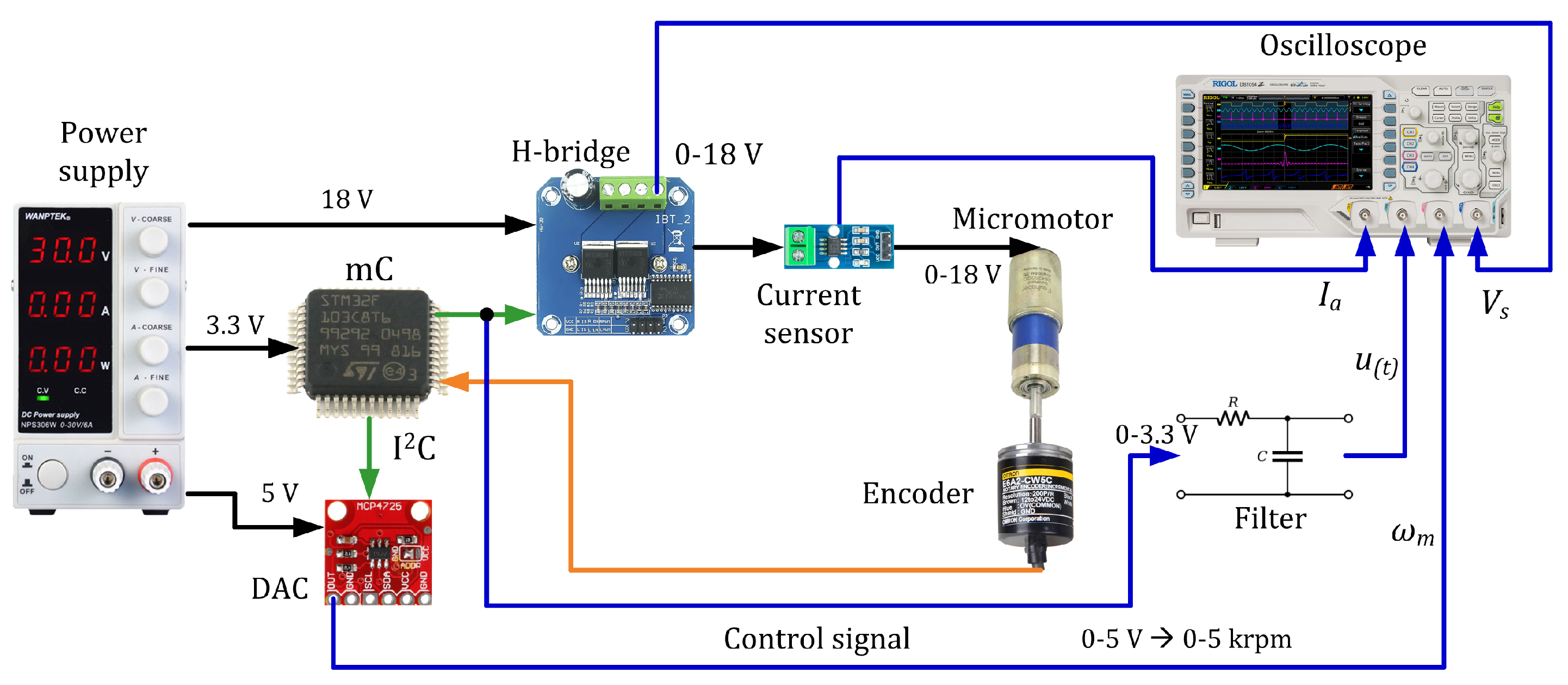

Figure 9.

Hardware Architecture Overview.

Figure 9.

Hardware Architecture Overview.

Figure 10.

Experimental testbench for DC micro-motor control and data acquisition.

Figure 10.

Experimental testbench for DC micro-motor control and data acquisition.

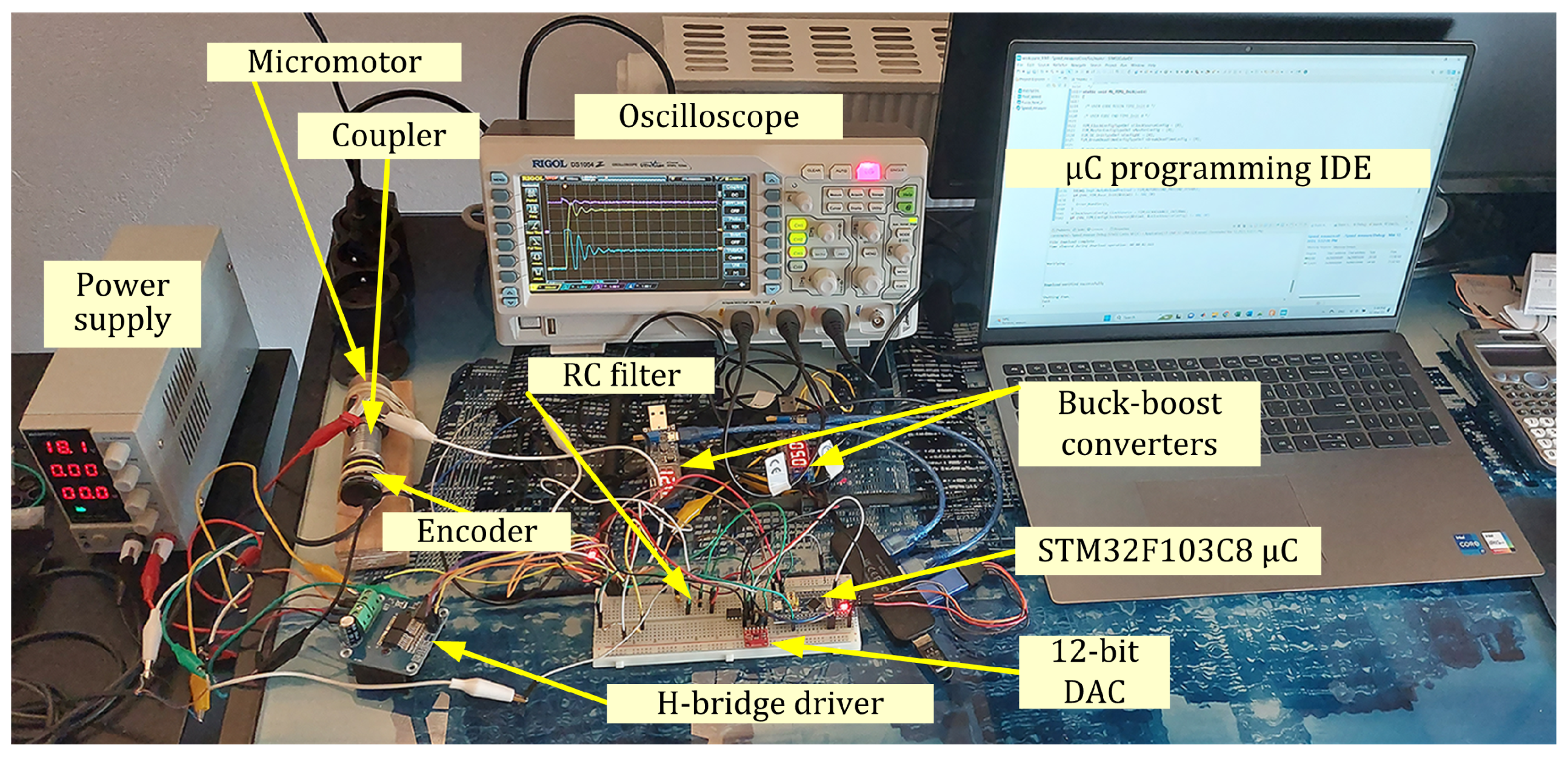

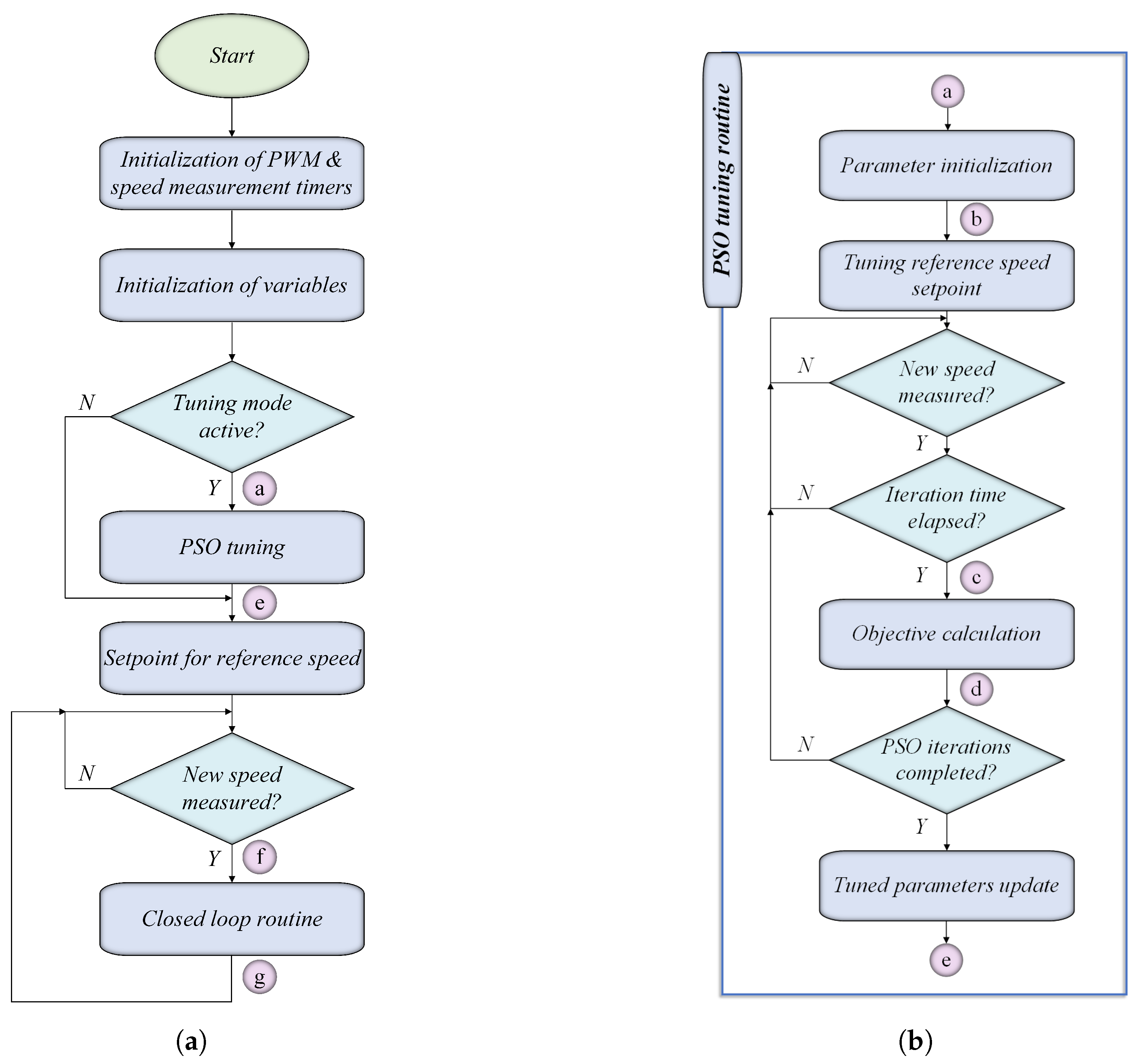

Figure 11.

Software architecture flowchart for (a) main control algorithm and (b) PSO tuning routine.

Figure 11.

Software architecture flowchart for (a) main control algorithm and (b) PSO tuning routine.

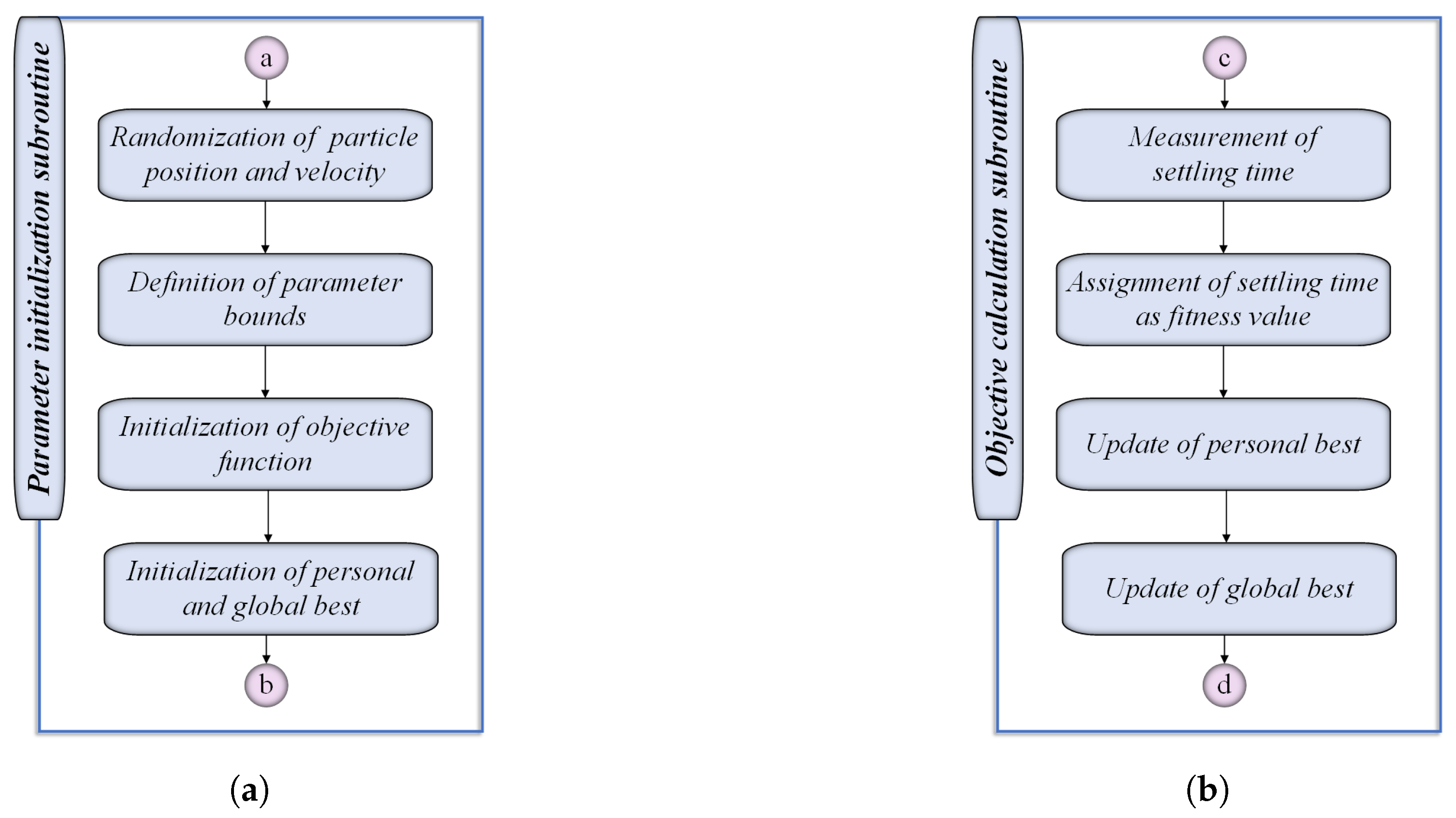

Figure 12.

PSO tuning subroutines (a) Parameter initialization and (b) Objective calculation.

Figure 12.

PSO tuning subroutines (a) Parameter initialization and (b) Objective calculation.

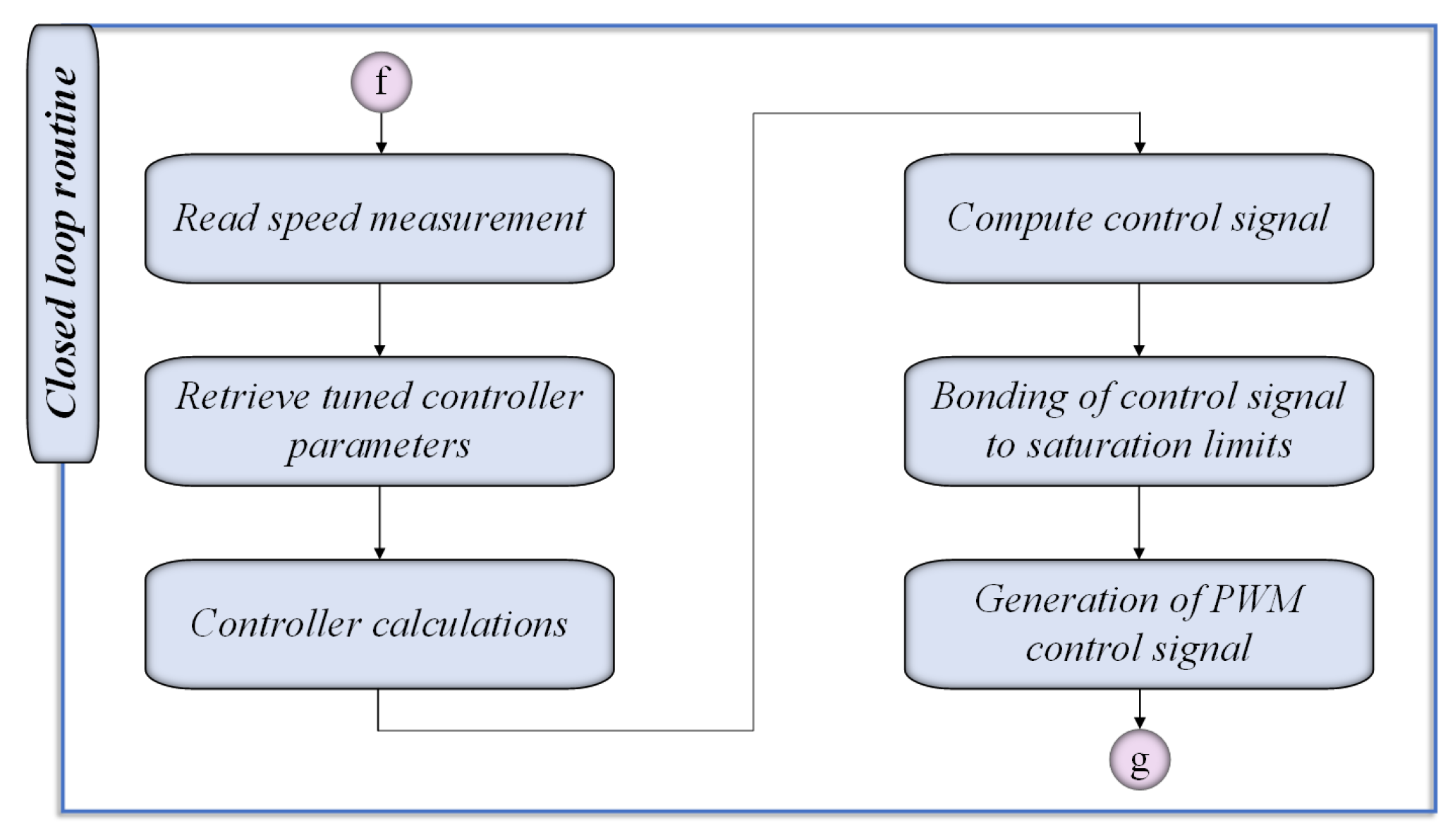

Figure 13.

Closed loop routine flowchart.

Figure 13.

Closed loop routine flowchart.

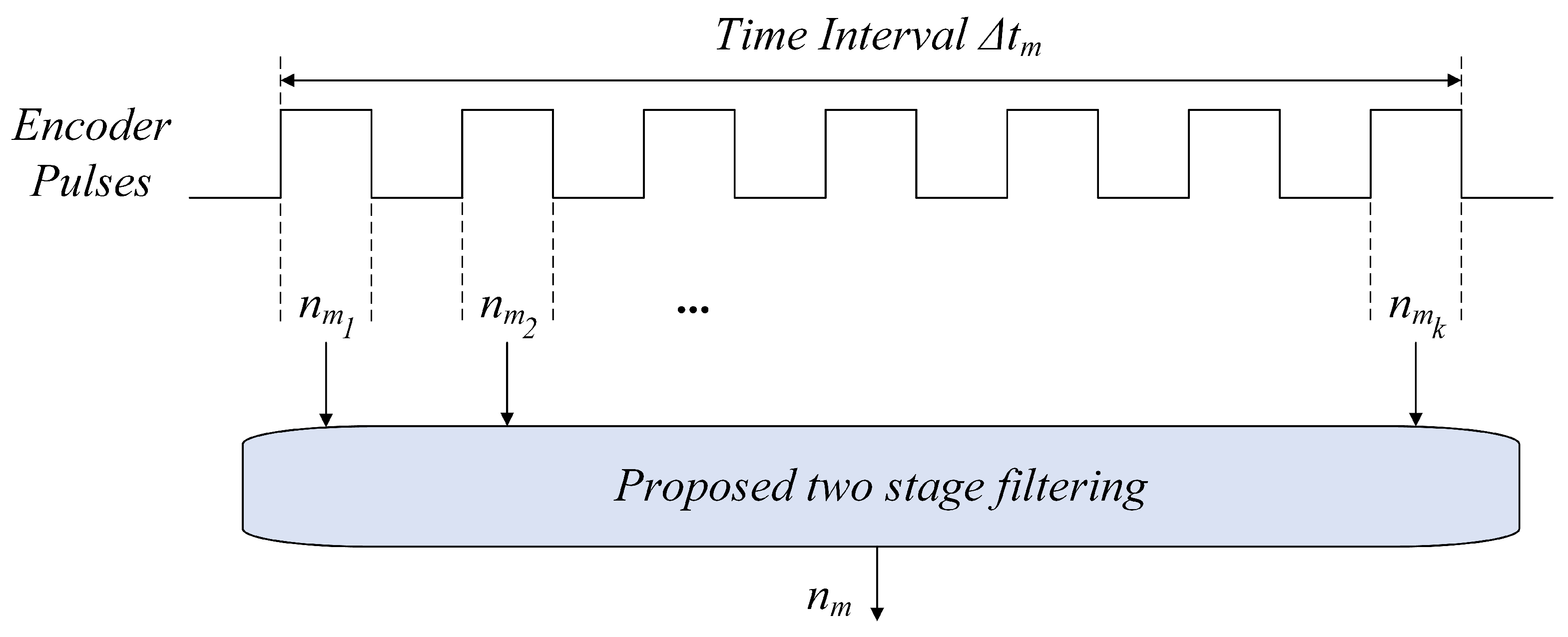

Figure 15.

Schematic of proposed speed measurement methodology.

Figure 15.

Schematic of proposed speed measurement methodology.

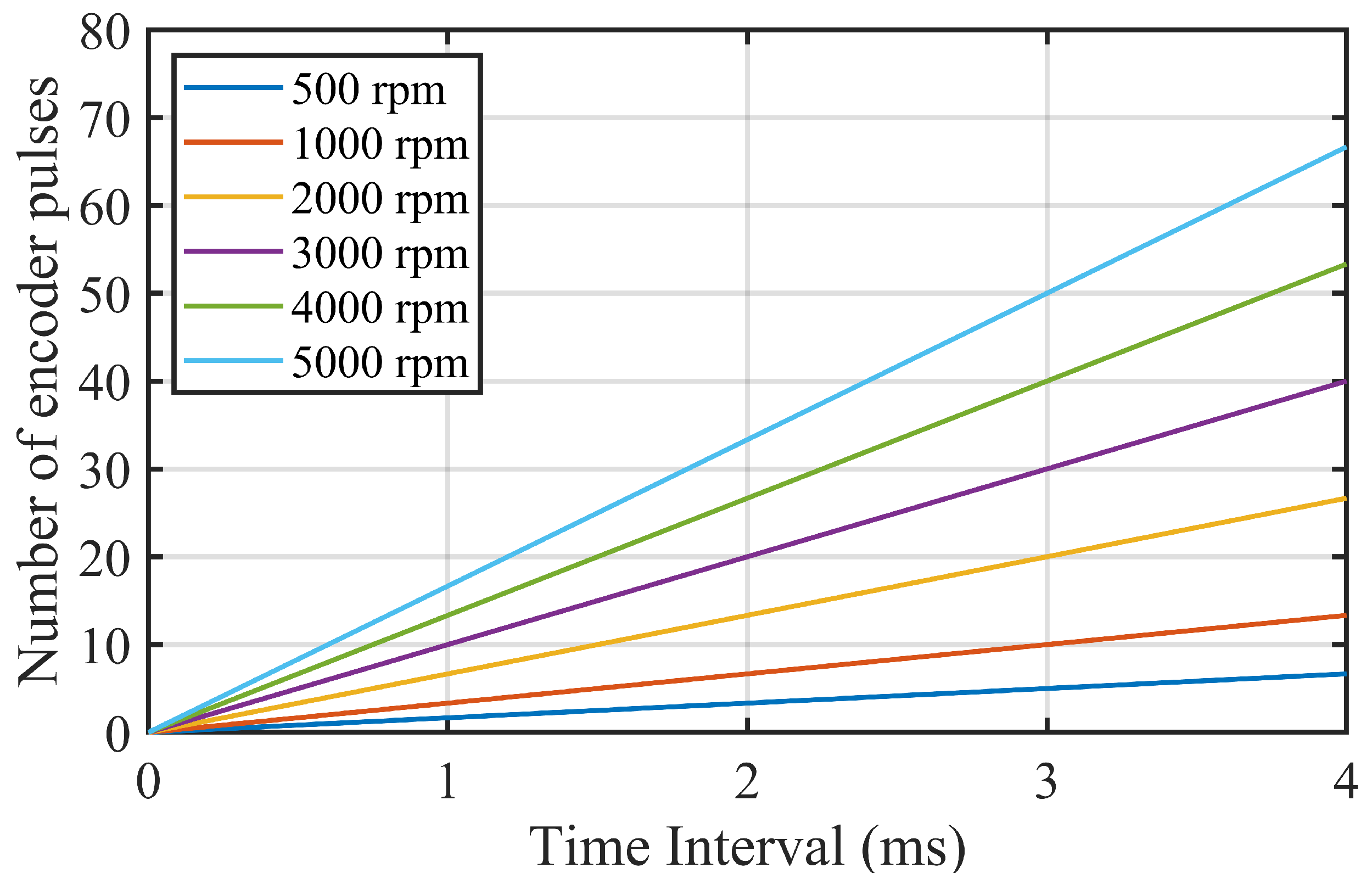

Figure 16.

Number of encoder pulses generated for different time intervals and micro-motor speeds.

Figure 16.

Number of encoder pulses generated for different time intervals and micro-motor speeds.

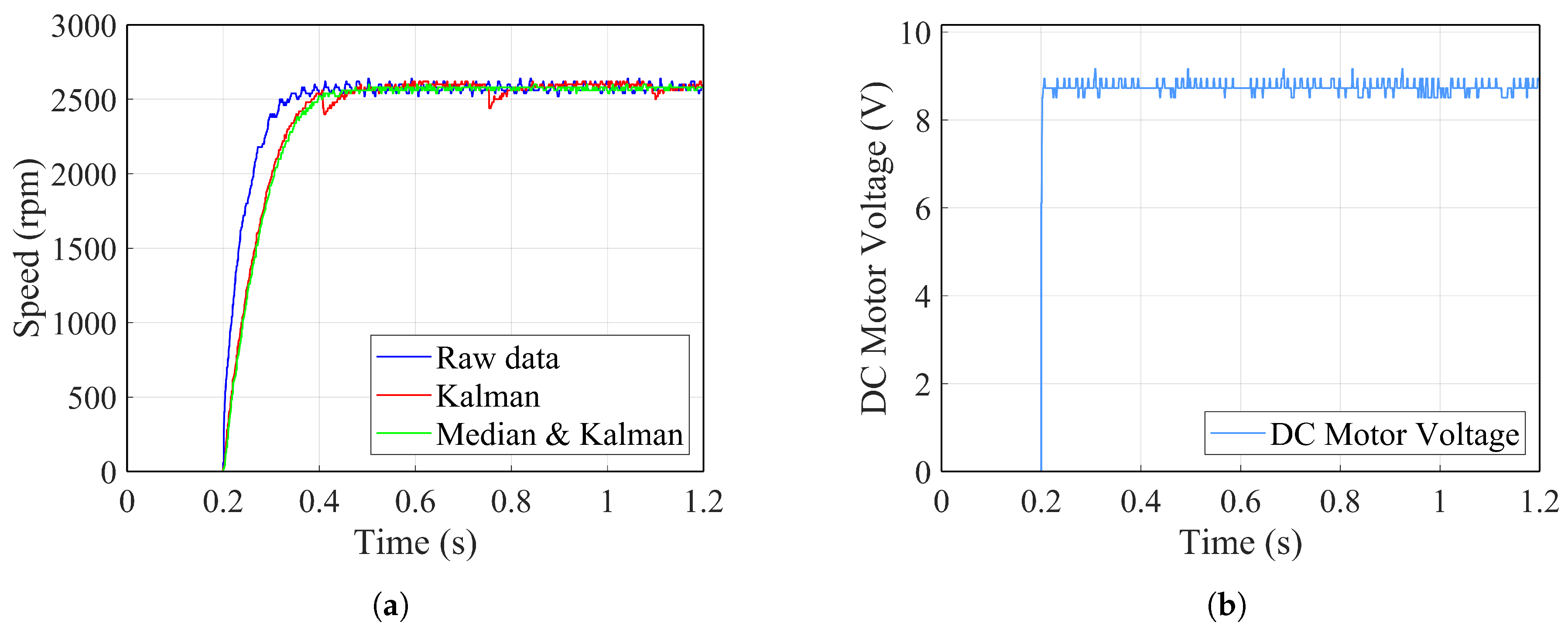

Figure 17.

Speed measurements for step voltage. (a) Comparison between raw data, Kalman filtering, and the proposed two-stage filtering method. (b) Depicts the step input voltage.

Figure 17.

Speed measurements for step voltage. (a) Comparison between raw data, Kalman filtering, and the proposed two-stage filtering method. (b) Depicts the step input voltage.

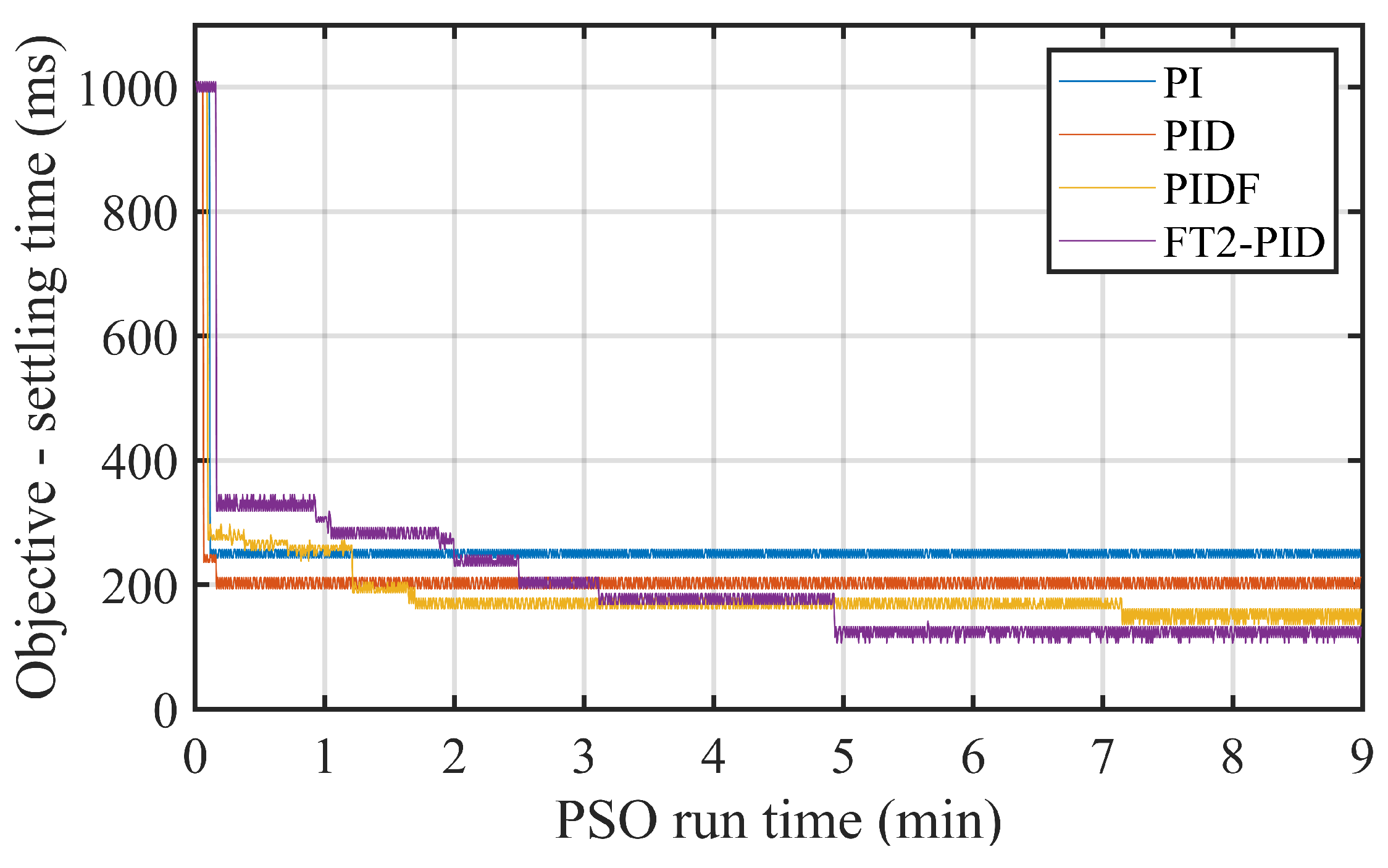

Figure 18.

PSO Convergence Times for Different Controllers. The plot illustrates the convergence times for PI, PID, PID with D Filtering (PIDF), and FT2-PID controllers. A target speed of 2750 rpm was maintained for all evaluations.

Figure 18.

PSO Convergence Times for Different Controllers. The plot illustrates the convergence times for PI, PID, PID with D Filtering (PIDF), and FT2-PID controllers. A target speed of 2750 rpm was maintained for all evaluations.

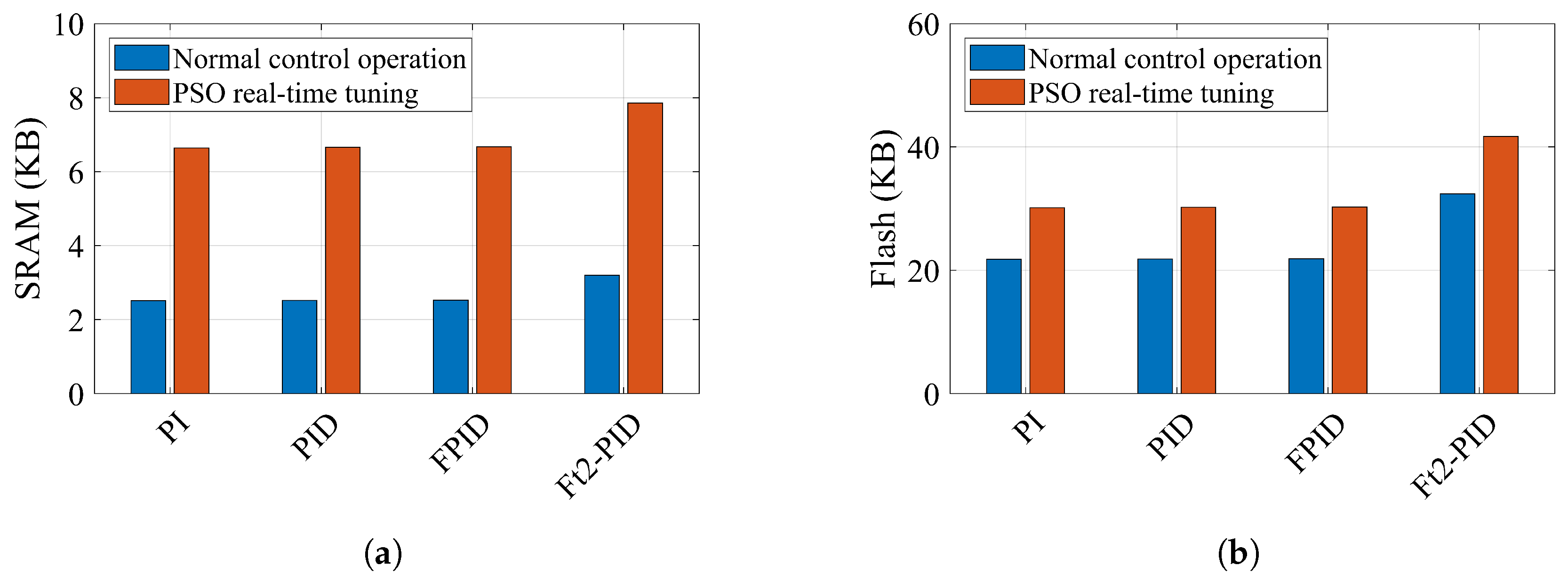

Figure 19.

Memory consumption comparison between SRAM and Flash for all controllers. (a) Shows SRAM memory consumption, and (b) shows Flash memory consumption.

Figure 19.

Memory consumption comparison between SRAM and Flash for all controllers. (a) Shows SRAM memory consumption, and (b) shows Flash memory consumption.

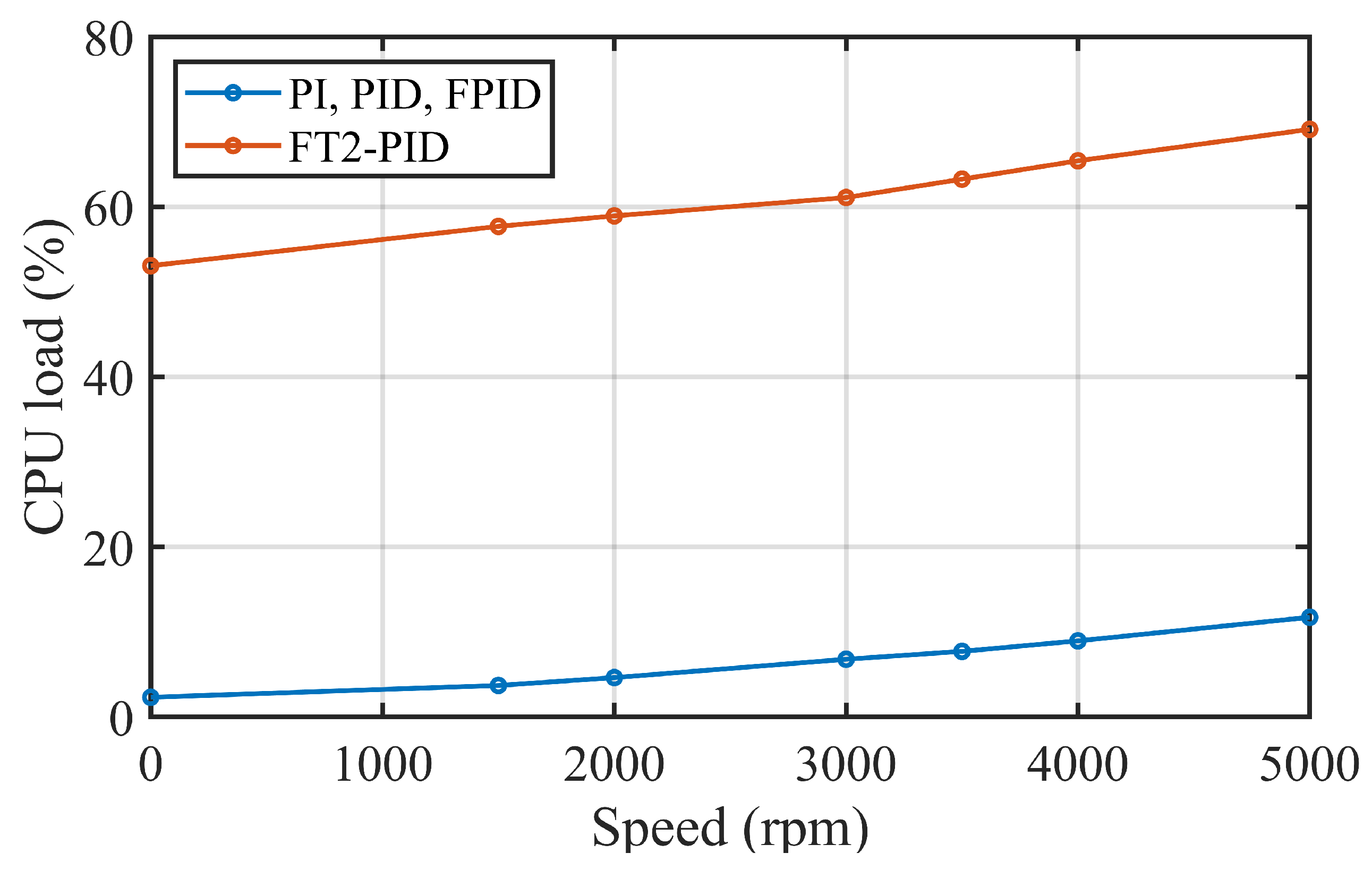

Figure 20.

CPU load for different steady state speeds.

Figure 20.

CPU load for different steady state speeds.

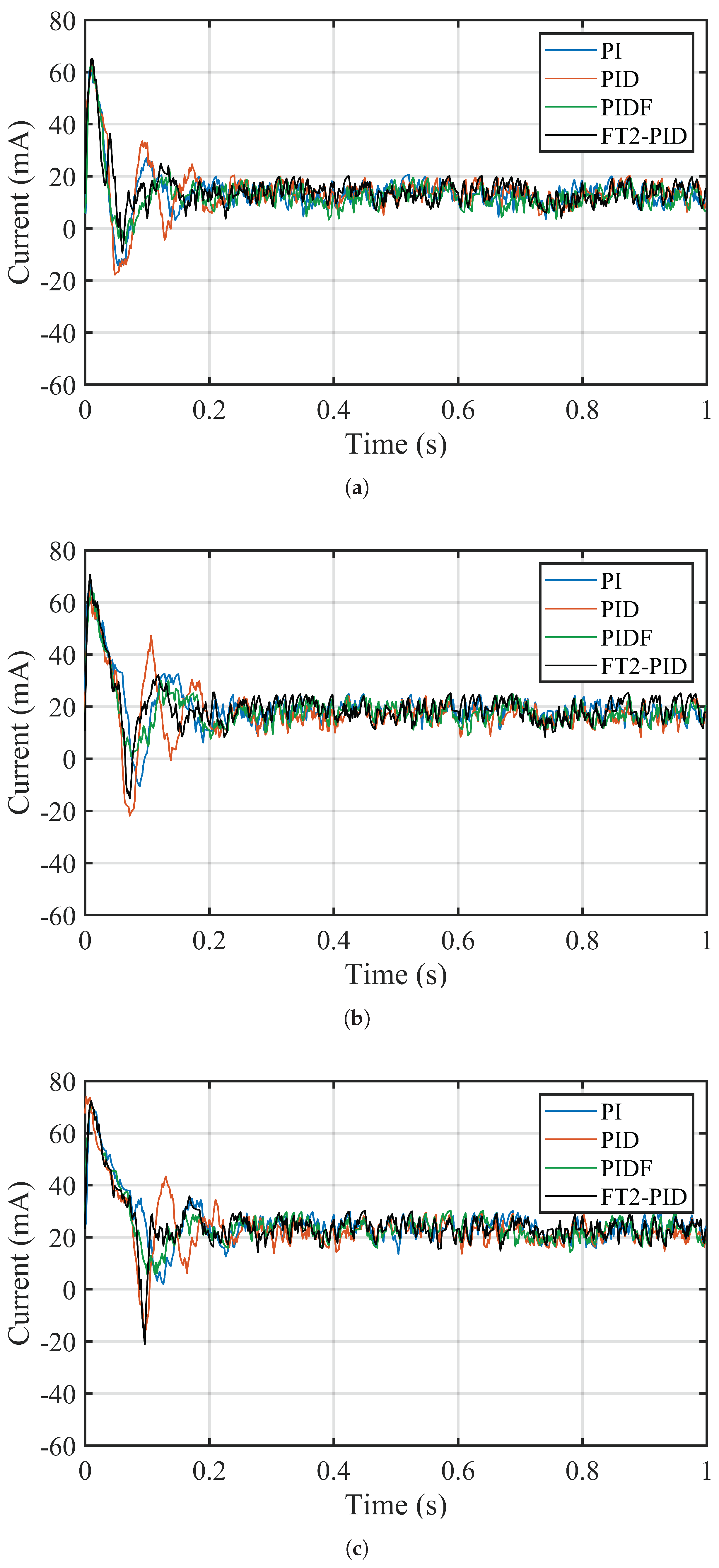

Figure 21.

Current experimental results for different reference speeds. (a) Shows the response for 2000 rpm, (b) for 2750 rpm, and (c) for 3500 rpm.

Figure 21.

Current experimental results for different reference speeds. (a) Shows the response for 2000 rpm, (b) for 2750 rpm, and (c) for 3500 rpm.

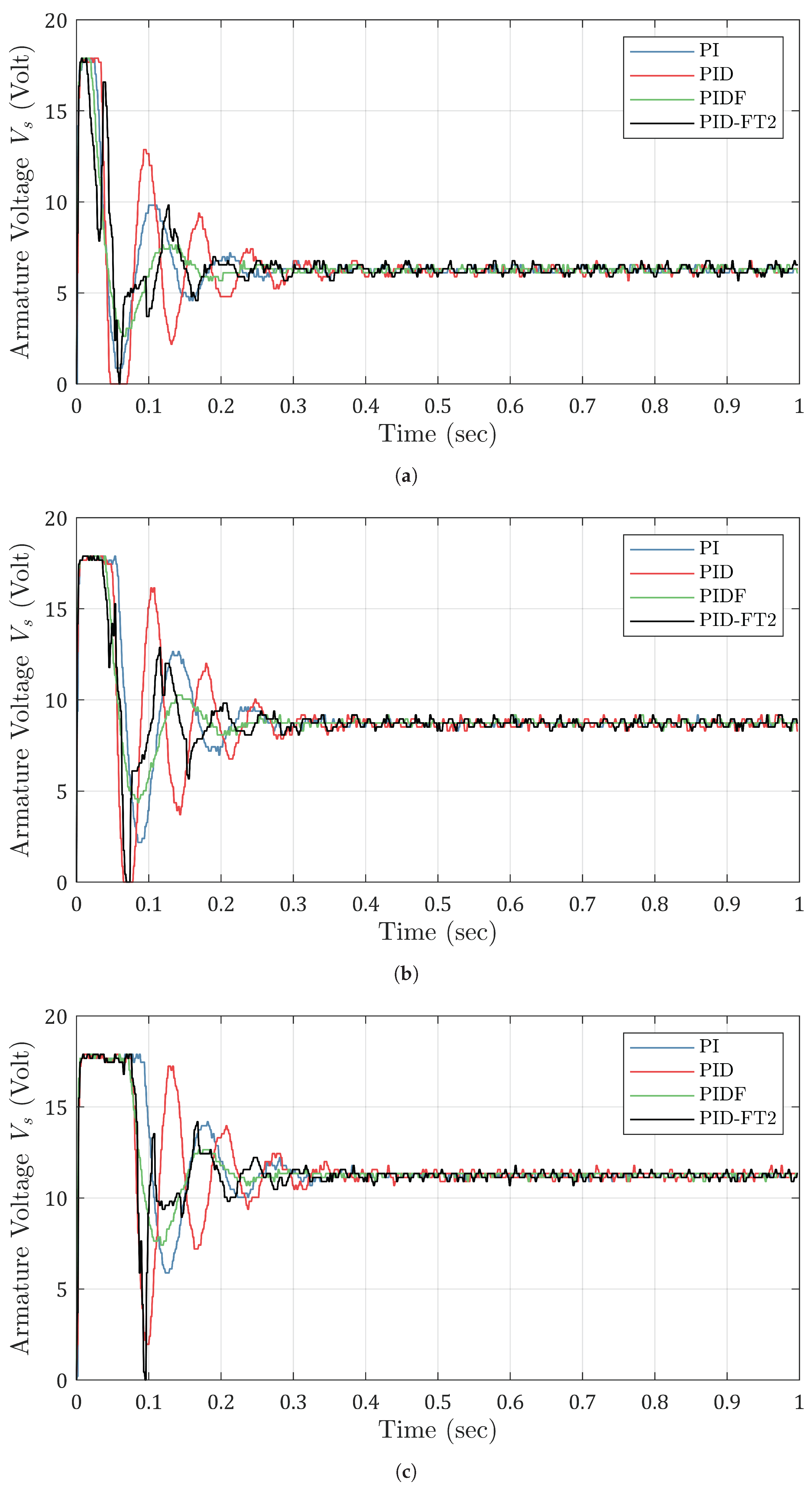

Figure 22.

Armature voltage experimental results for different reference speeds. (a) Shows the response for 2000 rpm, (b) for 2750 rpm, and (c) for 3500 rpm.

Figure 22.

Armature voltage experimental results for different reference speeds. (a) Shows the response for 2000 rpm, (b) for 2750 rpm, and (c) for 3500 rpm.

Figure 23.

Motor speed experimental results for different reference speeds. (a) Shows the response for 2000 rpm, (b) for 2750 rpm, and (c) for 3500 rpm.

Figure 23.

Motor speed experimental results for different reference speeds. (a) Shows the response for 2000 rpm, (b) for 2750 rpm, and (c) for 3500 rpm.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of filter coefficient value selection.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of filter coefficient value selection.

| N |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| Small |

✓ Fast response to rapid error changes. ✓ Better adaptation to dynamic error changes. ✓ Improved tracking of small error variations. |

✗ Limited noise suppression. ✗ Increased sensitivity to noise. ✗ Potential instability due to noise amplification. |

| Large |

✓ Enhanced noise filtering capabilities. ✓ Reduced controller impact of high-frequency noise. ✓ Improved stability by attenuating unwanted oscillations. |

✗ Slower response to fast error dynamics. ✗ Reduced system responsiveness to fast error changes. ✗ Possible increased overshoot and longer settling time. |

Table 2.

The developed Fuzzy Association Matrix (FAM) for IT2-FLC.

Table 2.

The developed Fuzzy Association Matrix (FAM) for IT2-FLC.

| |

|

|

Error |

|

| |

|

MF1 |

MF2 |

MF3 |

| |

MF1 |

MF5 |

MF4 |

MF3 |

| Change in Error |

MF2 |

MF4 |

MF3 |

MF2 |

| |

MF3 |

MF3 |

MF2 |

MF1 |

Table 3.

Parameter mapping based on PID Tuning Index.

Table 3.

Parameter mapping based on PID Tuning Index.

|

Corresponding PID Parameters |

| [0, 1] |

|

| (1, 2] |

|

| (2, 3] |

|

| (3, 4] |

|

| (4, 5] |

|

| (5, 6] |

|

| (6, 7] |

|

| (7, 8] |

|

| (8, 9] |

|

| (9, 10] |

|

Table 4.

Microcontroller specifications.

Table 4.

Microcontroller specifications.

| Parameter |

Details |

| Microcontroller |

STM32F103C8 |

| Core Architecture |

32-bit ARM Cortex M3 |

| Clock Speed |

72 MHz |

| Operating Voltage |

3.3 V |

| Flash Memory |

64 KB |

| SRAM |

20 KB |

| Data Bus Width |

32 b |

| Cost |

5 € |

Table 5.

Summary of hardware components.

Table 5.

Summary of hardware components.

| Hardware |

Part Number |

| Micro-motor |

Faulhaber 2842S018C |

| Microcontroller |

STM32F103C8 |

| Power supply |

NPS306W |

| Oscilloscope |

Rigol DS1054Z |

| Motor driver |

BTS7960 |

| Speed sensor |

OMRON E6A2-CW5C |

| Current Sensor |

ACS712 |

| DAC |

MCP4725 |

| Buck boost |

DR-YM-288 |

Table 6.

PSO parameter values used in this work.

Table 6.

PSO parameter values used in this work.

| Parameter |

Value |

Description |

| Population Size (N) |

6 |

Particle population of the swarm. |

| Maximum Iterations () |

100 |

Number of iterations. |

| Inertia Weight (w) |

Varies between 0.2 and 0.9 |

Exploration-exploitation balance. |

| Cognitive Coefficient () |

2 |

Weight for the best personal position. |

| Social Coefficient () |

2 |

Weight for the best global position. |

| Bounds for

|

[0, 10] |

Proportional gain parameter range. |

| Bounds for

|

[0, 1] |

Integral gain parameter range. |

| Bounds for

|

[0, 1] |

Derivative gain parameter range. |

| Bounds for N

|

[0, 100] |

Filter coefficient range. |

| Reference Speed Setpoint |

2750 rpm |

Tuning micro-motor speed. |

Table 7.

Correlation between PWM resolution and frequency.

Table 7.

Correlation between PWM resolution and frequency.

| Bit Resolution |

PWM Frequency (Hz) |

| 10 |

70314 |

| 11 |

35156 |

| 12 |

17578 |

| 13 |

8789 |

| 14 |

4394 |

Table 8.

Advantages and disadvantages of selecting small or large .

Table 8.

Advantages and disadvantages of selecting small or large .

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| Small |

✓ Enables faster control updates, improving response to dynamic changes. ✓ Facilitates frequent speed measurements, enhancing the precision of real-time control. ✓ Enhances the system’s capability to adapt to fast changes in speed. |

✗ Lower accuracy in speed estimation due to fewer encoder pulses within the interval. ✗ Increased sensitivity to signal noise, potentially introducing control instability. ✗ Limited low speed resolution, due to the small number of pulses produced within the time interval. |

| Large |

✓ Improves measurement accuracy by averaging over more encoder pulses. ✓ Provides smoother speed calculations with reduced sensitivity to noise. ✓ Increased resolution at low speeds since a higher number of pulses generated within the time interval. |

✗ Slower system response to dynamic changes, leading to potential prolonged error correction. ✗ Delays in control actions, potentially affecting performance in fast-changing scenarios. ✗ Increased likelihood of missing short-duration speed events. |

Table 9.

Selected Kalman filter parameters in this work.

Table 9.

Selected Kalman filter parameters in this work.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Process Noise Covariance (Q) |

0.0005 |

| Measurement Noise Covariance (R) |

0.1 |

| Initial Estimate Error Covariance (P) |

1 |

| Initial Speed Estimate () |

0 |

| Initial Kalman Gain (K) |

1 |

Table 10.

PSO tuning results for PI, PID, and PIDF controllers.

Table 10.

PSO tuning results for PI, PID, and PIDF controllers.

| Controller |

|

|

|

N |

| PI |

4 |

0.12 |

- |

- |

| PID |

7.8 |

0.059 |

0.41 |

- |

| PIDF |

2.72 |

0.0069 |

0.61 |

57.4 |

Table 11.

PSO tuning results for FT2-PID controller based on .

Table 11.

PSO tuning results for FT2-PID controller based on .

|

|

|

|

| [0, 1] |

|

|

|

| (1, 2] |

|

|

|

| (2, 3] |

|

|

|

| (3, 4] |

|

|

|

| (4, 5] |

|

|

|

| (5, 6] |

|

|

|

| (6, 7] |

|

|

|

| (7, 8] |

|

|

|

| (8, 9] |

|

|

|

| (9, 10] |

|

|

|

Table 12.

Memory requirements for DC micro-motor control.

Table 12.

Memory requirements for DC micro-motor control.

| Memory |

Total Size |

PI |

PID |

PIDF |

FT2-PID |

| SRAM |

20 KB |

2.51 KB |

2.52 KB |

2.53 KB |

3.20 KB |

| Flash |

64 KB |

21.78 KB |

21.84 KB |

21.88 KB |

32.39 KB |

Table 13.

Memory requirements for PSO real-time tuning.

Table 13.

Memory requirements for PSO real-time tuning.

| Memory |

Total Size |

PI |

PID |

PIDF |

FT2-PID |

| SRAM |

20 KB |

6.64 KB |

6.66 KB |

6.67 KB |

7.86 KB |

| Flash |

64 KB |

30.14 KB |

30.22 KB |

30.28 KB |

41.69 KB |

Table 14.

CPU load at various micro-motor speeds.

Table 14.

CPU load at various micro-motor speeds.

| Speed (rpm) |

CPU Load (% - PI, PID, PIDF) |

CPU Load (% - FT2-PID) |

| 0 |

2.31 |

53.09 |

| 1500 |

3.70 |

57.72 |

| 2000 |

4.63 |

58.95 |

| 3000 |

6.79 |

61.11 |

| 3500 |

7.72 |

63.27 |

| 4000 |

8.95 |

65.43 |

| 5000 |

11.73 |

69.14 |

Table 15.

Overview of experimental cases and controllers.

Table 15.

Overview of experimental cases and controllers.

| Case |

Target Speed (rpm) |

Controllers Evaluated |

Objective |

| Case 1 |

2000 |

PI, PID, PIDF, FT2-PID |

Low-Speed Performance |

| Case 2 |

2750 |

PI, PID, PIDF, FT2-PID |

Mid-Speed Performance |

| Case 3 |

3500 |

PI, PID, PIDF, FT2-PID |

High-Speed Performance |

Table 16.

Rise time for examined controllers.

Table 16.

Rise time for examined controllers.

| Case |

Reference Speed |

PI |

PID |

PIDF |

FT2-PID |

| 1 |

2000 rpm |

22.7 ms |

24.3 ms |

26.1 ms |

29.7 ms |

| 2 |

2750 rpm |

34.5 ms |

37.8 ms |

35.9 ms |

37.7 ms |

| 3 |

3500 rpm |

50.7 ms |

49.9 ms |

52.3 ms |

53.5 ms |

Table 17.

Overshoot for examined controllers.

Table 17.

Overshoot for examined controllers.

| Case |

Reference Speed |

PI |

PID |

PIDF |

FT2-PID |

| 1 |

2000 rpm |

19.00% |

14.00% |

9.00% |

12.00% |

| 2 |

2750 rpm |

21.00% |

11.00% |

11.00% |

12.30% |

| 3 |

3500 rpm |

25.00% |

8.00% |

16.00% |

12.50% |

Table 18.

Settling time for examined controllers.

Table 18.

Settling time for examined controllers.

| Case |

Reference Speed |

PI |

PID |

PIDF |

FT2-PID |

| 1 |

2000 rpm |

240 ms |

230 ms |

145 ms |

104 ms |

| 2 |

2750 rpm |

250 ms |

203 ms |

149 ms |

123 ms |

| 3 |

3500 rpm |

313 ms |

245 ms |

225 ms |

167 ms |