Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

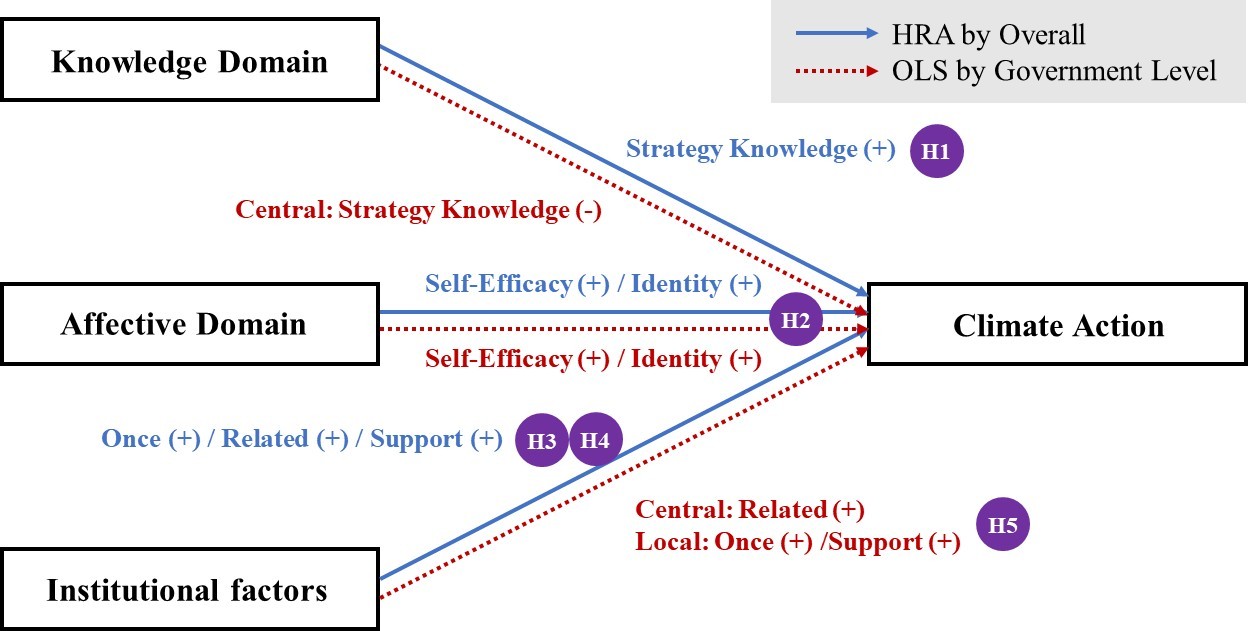

1.1. Climate Change Literacy and the Knowledge-Behavior Gap

1.2. Policy Vision to Administrative Practice: The Critical Role of Public Officials

1.3. Behavior Differences Across Governance Contexts

1.4. Research Objectives

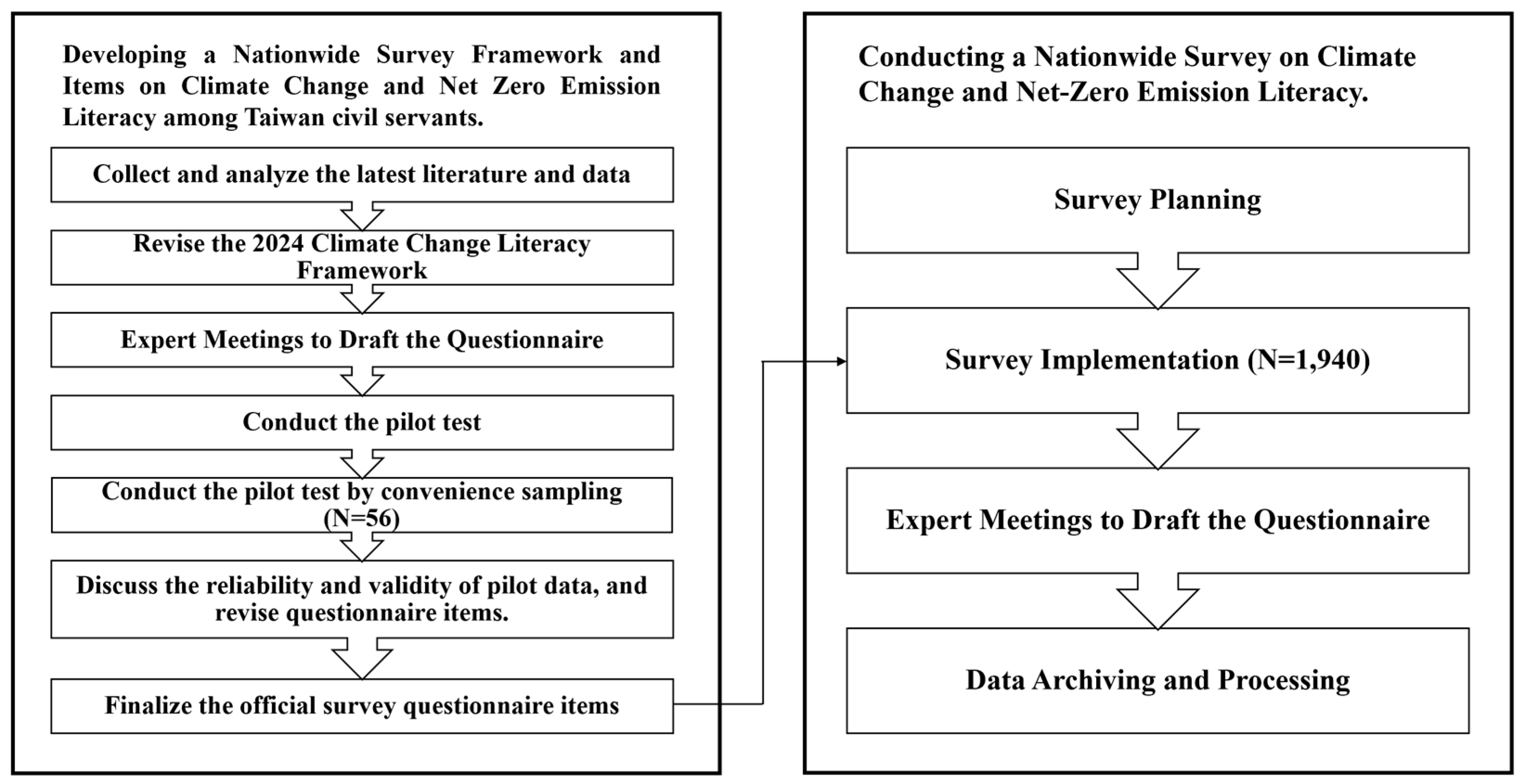

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Sampling Procedures

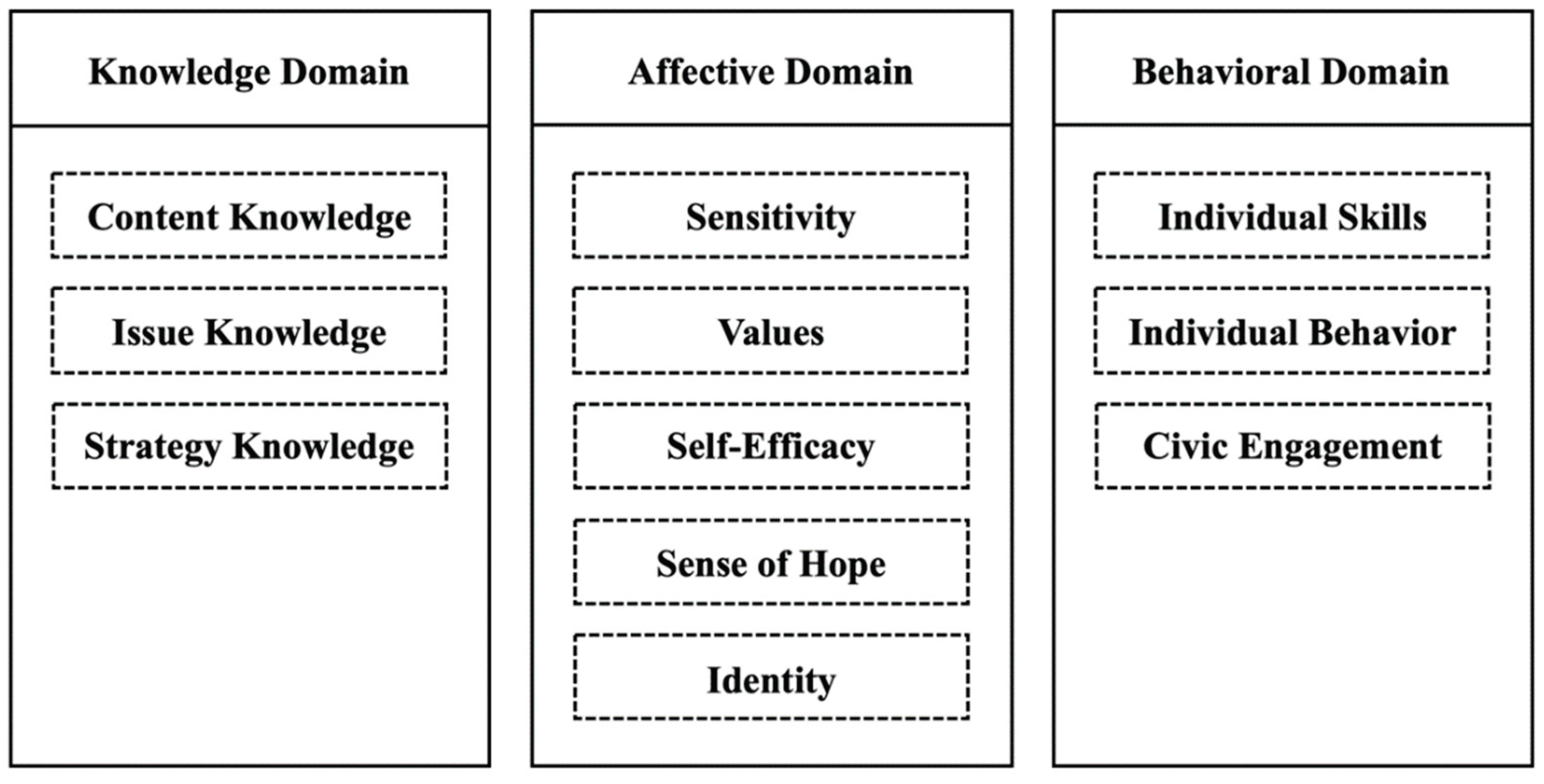

2.2. Measurement of Climate Change Literacy

2.3. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Background Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCL | Climate Change Literacy |

| CK | Content Knowledge |

| IK | Issue Knowledge |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| SK | Strategy Knowledge |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Taiwanese Public Servants’ Climate Change Literacy Perception Survey - Questionnaire

| Sub-domains | Question |

| Background Information (3) |

Q1. When did you first hear about the term ‘’climate change’’? (1) Just now (I had never heard it before) (2) Within the past year (3) Within the past 1-3 years (4) Within the past 3-5 years (5) Within the past 5-10 years (6) Within the past 10-15 years (7) Within the past 15-20 years (8) More than 20 years ago (9) I have heard of it, but cannot recall when Q2. Before today, have you ever heard of the term “climate change mitigation”? ☐ Yes ☐ No Q3. Before today, have you ever heard of the term “climate change adaptation”? ☐ Yes ☐ No |

Section 1. Knowledge Domain (19)Section 2. Affective Domain (28)

| Sub-domains | Question |

| Content Knowledge (4) |

Q4. On April 16, 2024, Dubai experienced the heaviest rainfall in 75 years, with daily precipitation far exceeding the city’s annual average. In the field of climate change, such an event is called: (1) Extreme climate (2) Extreme weather (3) Anomalous condition (4) Unresolved phenomenon |

| Q5. Which of the following gases has the strongest warming potential per unit of weight? (1) Carbon dioxide (CO2) (2) Methane (CH4) (3) Nitrous oxide (N2O) (4) Hydrogen (H₂) |

|

| Content Knowledge (4) |

Q6. Which of the following is the primary cause of climate change? (1) Burning fossil fuels (2) Ozone layer depletion (3) Deforestation (4) Use of plastics |

| Q7. Over the past five years, the global atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) has decreased. (True/False) ☐ True ☑ False |

|

| Issue knowledge (3) |

Q8. Compared with the pre-industrial era, by approximately how many degrees Celsius has the global average temperature increased? (1) 0.5°C (2) 1.0°C (3) 2.0°C (4) 3.0°C |

| Q9. In 2023, which energy source accounted for the largest share of Taiwan’s electricity generation? (1) Hydropower (2) Thermal power (3) Nuclear power (4) Solar and wind power |

|

| Q10. In the international community, who makes the key decisions regarding actions to address climate change? (1) Scientists (2) Media (3) Political leaders (4) Civil society organizations |

|

| Strategy Knowledge (12) |

Q11. Which of the following is not considered a climate change adaptation strategy? (1) Installing additional air conditioning units on school campuses (2) Strengthening urban flood control and drainage systems (3) Developing water resources through seawater desalination (4) Replacing fuel-powered vehicles with electric vehicles |

| Q12. In Taiwan, which of the following is considered a priority measure for achieving net-zero emissions? (1) Announcing carbon reduction pledges (2) Implementing afforestation programs (3) Reducing electricity consumption (4) Joining international climate organizations |

|

| Q13. Which of the following groups is not considered highly vulnerable to heat-related risks? (1) Patients with chronic diseases (2) Persons with physical or mental disabilities (3) Outdoor workers (4) Young adults |

|

| Q14.”Net-zero emissions” means reducing anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions to zero. (True/False) ☐ True ☑ False |

|

| Strategy Knowledge (12) |

Q15. Which of the following laws has been enacted in Taiwan in response to the severity of global climate change? (1) Climate Mitigation and Adaptation Act (2) Climate Change Response Act (3) Greenhouse Gas Reduction and Management Act (4) No such law exists |

| Q16. In Taiwan’s 2050 Net-Zero Emissions Roadmap, which of the following is classified as a “carbon removal” strategy? (1) Just Transition (2) Energy efficiency (3) Net-zero green lifestyle (4) Natural carbon sinks |

|

| Q17. In Taiwan, can private enterprises obtain “Voluntary Emission Reduction” by planting trees in their own private parks? (True/False) ☐ True ☑ False |

|

| Q18. According to Taiwan’s Climate Change Response Act, local governments are required to develop climate change adaptation implementation plans. (True/False) ☑ True ☐ False |

|

| Q19. Which international treaty currently governs global climate change responses under the United Nations? (1) Kyoto Protocol (2) Washington Convention (CITES) (3) Paris Agreement (4) Montreal Protocol |

|

| Q20. Following the current global trend in carbon reduction, in which year has Taiwan set its national target for achieving net-zero emissions? (1) 2030 (2) 2040 (3) 2050 (4) 2060 |

|

| Q21. Which of the following is not a potential impact of climate change? (1) Banks factoring climate risks into financing decisions (2) Continued increase in oil demand (3) Expansion of employment opportunities requiring climate expertise (4) Fluctuations in food prices |

|

| Q22. Regarding the government agencies legally designated with responsibilities for climate change affairs in Taiwan, which of the following assignments is incorrect? (1) Just Transition is overseen by the National Development Council (NDC) (2) Carbon Fee Collection is overseen by the Ministry of Finance (3) Natural Carbon Sinks are overseen by the Ministry of Agriculture (MOA) (4) Mass Transit System Development is overseen by the Ministry of Transportation and Communications (MOTC) |

Section 2. Affective Domain (28)

| Sub-domains | Question |

| Sensitivity (6) | Q23. Climate change is already happening. |

| Q24. Climate change has already affected my life and the lives of my family and friends. | |

| Q25. Global climate change has already entered a state of emergency. | |

| Q26. More people in society are now discussing climate change. | |

| Q27. The average summer temperature in Taiwan is becoming increasingly higher. | |

| Q28. The summer season in Taiwan is becoming increasingly longer. | |

| Values (12) | Q29. Everyone has a responsibility to respond to climate change. |

| Q30. Climate change should be regarded as a national security issue. | |

| Q31. The implementation of climate change policies should also consider the rights and interests of traditional energy-related industries. | |

| Q32. In your opinion, to what extent is climate change related to the environment (e.g., environmental quality, ecological conservation)? | |

| Q33. In your opinion, to what extent is climate change related to society (e.g., human well-being, social justice)? | |

| Q34. In your opinion, to what extent is climate change related to the economy (e.g., economic development, urban construction)? | |

| Q35. The impacts of climate change are equal for everyone. (Reverse-coded item) | |

| Q36. Cross-departmental collaboration within the government is very important for responding to climate change. | |

| Q37. International carbon reduction measures (e.g., supply chain decarbonization, carbon tariffs) will affect the cost of living. | |

| Q38. Climate change response measures will affect the nature of my work responsibilities. | |

| Q39. The government should develop long-term response plans for periods of extreme heat and cold weather. | |

| Q40. The responsibilities of my department/unit are related to climate change. | |

| Self-Efficacy (7) | Q41. My daily carbon-reduction actions can help mitigate global climate change. |

| Q42. My work responsibilities contribute to the effectiveness of climate change response measures. | |

| Q43. I am able to maintain my health during periods of extreme heat or cold (e.g., heatwaves, cold spells). | |

| Q44. My knowledge and skills enable me to carry out tasks related to climate change response. | |

| Q45. I am able to collaborate with personnel from other departments or agencies on projects or tasks related to climate change. | |

| Q46. Climate change can create more opportunities for my professional development. | |

| Q47. Climate change will bring more challenges to my work. | |

| Sense of Hope (2) | Q48. I believe that through collective effort, climate change problems can be solved. |

| Q49. I believe that there are people who are working to solve climate change problems. | |

| Identity (1) | Q50. I will take actions to respond to climate change and live in a more sustainable way. |

Section 3. Behavioral Domain (13)

| Sub-domains | Question |

| Individual Skills (5) |

Q51. I am capable of collecting information on climate change that is relevant to the responsibilities (or professional) of my department. |

| Q52. I am capable of interpreting professional scientific information related to climate change (e.g., carbon emissions, temperature changes). | |

| Q53. I am capable of interpreting social information related to climate change (e.g., regulations and policies, social advocacy, industry trends). | |

| Q54. I am capable of translating climate change knowledge into messages that colleagues or the public can easily understand. | |

| Q55. I am capable of planning projects to respond to climate change. | |

| Individual Behavior | Q56. I regularly follow information related to climate change (e.g., news reports, online videos). |

| (5) | Q57. I participate in climate change–related training courses organized by the government or civil society. |

| Q58. When making purchases, I prioritize products with carbon labels (e.g., carbon footprint labels). | |

| Q59. I usually opt for a low-carb diet whenever possible. | |

| Q60. In hot weather, I avoid exposing myself to high-temperature environments. | |

| Civic Engagement | Q61. I try to persuade colleagues or the public to take action in response to climate change. |

| (3) | Q62. I pay attention to or prioritize supporting public figures who emphasize climate change policies. |

| Q63. I participate in civic activities related to climate change in my personal capacity (e.g., expressing public opinions, attending hearings, signing petitions). |

Section 4. Demographic Information (15)

| Q66. In which city/county is your current workplace located? | ||

| (1) Keelung City (2) Taipei City (3) New Taipei City (4) Taoyuan City (5) Hsinchu City (6) Hsinchu County (7) Miaoli County (8) Taichung City |

(9) Changhua County (10) Nantou County (11) Yunlin County (12) Chiayi City (13) Chiayi County (14) Tainan City (15) Kaohsiung City (16) Pingtung County |

(17) Taitung County (18) Hualien County (19) Yilan County (20) Penghu County (21) Kinmen County (22) Lienchiang County |

| Q71. What is your field of expertise? (Please indicate based on your highest level of education; multiple selections allowed) | |

| (1) Information Technology (2) Engineering (3) Mathematics, Physics, and Chemistry (4) Medicine and Health Sciences (5) Life Sciences (6) Biological Resources (7) Earth and Environmental Sciences (8) Architecture and Design (9) Arts (10) Social Sciences and Psychology |

(11) Mass Communication (12) Foreign Languages (13) Humanities (Literature, History, Philosophy) (14) Education (15) Law, Political Science, and Public Administration (16) Management (17) Finance and Economics (18) Recreation and Sports |

References

- AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (Ipcc) Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2023. ISBN 978-1-009-15789-6. [CrossRef]

- Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.W.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barrett, K.; Blanco, G.; et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (Eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland.; First.; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2023. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Blijleven, W.; Van Hulst, M. How Do Frontline Civil Servants Engage the Public? Practices, Embedded Agency, and Bricolage. The American Review of Public Administration 2021, 51, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braams, R.B.; Wesseling, J.H.; Meijer, A.J.; Hekkert, M.P. Civil Servant Tactics for Realizing Transition Tasks Understanding the Microdynamics of Transformative Government. Public Administration 2024, 102, 500–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjærseth, J.B. Towards a European Green Deal: The Evolution of EU Climate and Energy Policy Mixes. Int Environ Agreements 2021, 21, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecer, K.; Güner, O. The European Union’s Policies and Role in Tackling Climate Change in the Context of the European Green Deal. In The Social Consequences of Climate Change; Açikalin, Ş.N., Erçetin, Ş.Ş., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited, 2024; pp. 163–185. ISBN 978-1-83797-678-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wretling, V.; Balfors, B. Building Institutional Capacity to Plan for Climate Neutrality: The Role of Local Co-Operation and Inter-Municipal Networks at the Regional Level. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cai, W.; Zheng, X.; Lv, X.; An, K.; Cao, Y.; Cheng, H.S.; Dai, J.; Dong, X.; Fan, S.; et al. Global Readiness for Carbon Neutrality: From Targets to Action. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology 2025, 25, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickard, L.N.; Yang, Z.J.; Seo, M.; Harrison, T.M. The “I” in Climate: The Role of Individual Responsibility in Systematic Processing of Climate Change Information. Global Environmental Change 2014, 26, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapiains, R.; Beeton, R.J.; Walker, I.A. Individual responses to climate change: Framing effects on pro-environmental behaviors. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 46, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Barnett, J.; Brown, K.; Marshall, N.; O’Brien, K. Cultural Dimensions of Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation. Nature Clim Change 2013, 3, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Betsill, M. Rethinking Sustainable Cities: Multilevel Governance and the “Urban” Politics of Climate Change. Environmental Politics 2005, 14, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Harris, E.A.; Bain, P.G.; Fielding, K.S. Meta-Analyses of the Determinants and Outcomes of Belief in Climate Change. Nature Clim Change 2016, 6, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.S.; Clayton, S.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Capstick, S.; Whitmarsh, L. How Psychology Can Help Limit Climate Change. American Psychologist 2021, 76, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.-L.; Fan, R.; Pan, W.; Ma, X.; Hu, C.; Fu, P.; Su, J. The Role of Climate Literacy in Individual Response to Climate Change: Evidence from China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 405, 136874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L.; Böhm, G.; Fisher, S. Climate Change Perceptions and Their Individual-Level Determinants: A Cross-European Analysis. Global Environmental Change 2019, 55, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Moser, S.C. Individual Understandings, Perceptions, and Engagement with Climate Change: Insights from In-depth Studies across the World. WIREs Climate Change 2011, 2, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, N.P.; Andrews, T.M.; Krönke, M.; Lennard, C.; Odoulami, R.C.; Ouweneel, B.; Steynor, A.; Trisos, C.H. Climate Change Literacy in Africa. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaimi, N.; Mahmud, S.N.D. A Bibliometric Analysis of Climate Change Literacy between 2001 and 2021. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drews, S.; Van Den Bergh, J.C.J.M. What Explains Public Support for Climate Policies? A Review of Empirical and Experimental Studies. Climate Policy 2016, 16, 855–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.M.; Markowitz, E.M.; Howe, P.D.; Ko, C.-Y.; Leiserowitz, A.A. Predictors of Public Climate Change Awareness and Risk Perception around the World. Nature Clim Change 2015, 5, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Visschers, V.H.M.; Siegrist, M. Public Perception of Climate Change: The Importance of Knowledge and Cultural Worldviews. Risk Analysis 2015, 35, 2183–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutti, R. Closing the Knowledge-Action Gap in Climate Change. One Earth 2019, 1, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.-C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Van Velzen, R.; Lin, P.-H. The Climate Change Literacy of Public Officials in Taiwan: Implications and Strategies for Global Adaptation. Policy Studies 2025, 46, 168–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portus, R.; Aarnio-Linnanvuori, E.; Dillon, B.; Fahy, F.; Gopinath, D.; Mansikka-Aho, A.; Williams, S.-J.; Reilly, K.; McEwen, L. Exploring the Environmental Value Action Gap in Education Research: A Semi-Systematic Literature Review. Environmental Education Research 2024, 30, 833–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gestel, N.; Kuiper, M.; Pegan, A. Strategies and Transitions to Public Sector Co-Creation across Europe. Public Policy and Administration 2023, 09520767231184523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Meene, S.J.; Head, B.W.; Bettini, Y. Toward Effective Change in Urban Water Policy: The Role of Collaborative Governance and Cross-Scale Integration; Cooperative Research Centre for Water Sensitive Cities: Melbourne, Australia, 2016; Https://Watersensitivecities.Org.Au/Wp-Content/Uploads/2017/04/TMR_A3-1_Toward-Effective-Change-in-Urban-Water-Policy.Pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Innovative capacity of governments. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/innovative-capacity-of-governments_52389006-en.html (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Termeer, C.; Dewulf, A.; Rijswick, H.; Buuren, A.; Huitema, D.; Meijerink, S.; Rayner, T.; Wiering, M. The regional governance of climate adaptation: A framework for developing legitimate, effective, and resilient governance arrangements. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Willis, C.D.; Saul, J.E.; Bitz, J.; Pompu, K.; Best, A.; Jackson, B. Improving Organizational Capacity to Address Health Literacy in Public Health: A Rapid Realist Review. Public Health 2014, 128, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, B.S.; Qader, K.S.; Jamil, D.A.; Sabah, K.K.; Gardi, B.; Anwer, S.A. Work Engagement and Its Influence in Boosting Productivity. Int. J. Lang. Lit. Cult. 2022, 2, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. Engaging Leadership: How to Promote Work Engagement? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adla, L.; Eyquem-Renault, M.; Gallego-Roquelaure, V. From the Leader’s values to organizational values: Toward a dynamic and experimental view on value work in SMEs. Management 2020, 23, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, B.A. ; NULL Cultivating a Culture of Sustainability: The Role of Organizational Values and Leadership in Driving Sustainable Practices. BEL 2025, 9, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aukhoon, M.A.; Iqbal, J.; Parray, Z.A. Corporate Social Responsibility Supercharged: Greening Employee Behavior through Human Resource Management Practices and Green Culture. Evidence-based HRM: a Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship 2024, 12, 945–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingaleva, Z.; Shironina, E.; Lobova, E.; Olenev, V.; Plyusnina, L.; Oborina, A. Organizational Culture Management as an Element of Innovative and Sustainable Development of Enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y. Enhancing pro-environmental behavior through green HRM: Mediating roles of green mindfulness and knowledge sharing for sustainable outcomes. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resanovich, S.L.; Hopthrow, T.; Randsley de Moura, G. Growing greener: Cultivating organisational sustainability through leadership development. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Lüpke, H.; Leopold, L.; Tosun, J. Institutional Coordination Arrangements as Elements of Policy Design Spaces: Insights from Climate Policy. Policy Sci 2023, 56, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Constitutes “Institutional Arrangements” for Member State Reporting within the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement? | PLOS Climate. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/climate/article?id=10.1371/journal.pclm.0000327 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Mogelgaard, K.; Dinshaw, A.; Ginoya, N.; Gutiérrez, M.; Preethan, P.; Waslander, J. From Planning to Action: Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation Into Development. 2018.

- Local Governments Facing Turbulence: Robust Governance and Institutional Capacities. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/12/8/462 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Local Government Strategies in the Face of Shocks and Crises: The Role of Anticipatory Capacities and Financial Vulnerability - Carmela Barbera, Martin Jones, Sanja Korac, Iris Saliterer, Ileana Steccolini, 2021. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0020852319842661 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Gomes, R.C.; Liddle, J.; Gomes, L.O.M. A Five-Sided Model Of Stakeholder Influence: A Cross-National Analysis of Decision Making in Local Government. Public Management Review 2010, 12, 701–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garritzmann, J.L.; Siderius, K. Introducing ‘Ministerial Politics’: Analyzing the Role and Crucial Redistributive Impact of Individual Ministries in Policy-Making. Governance 2025, 38, e12859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Bureaucracy and Climate Change Adaptation - Biesbroek - 2018 - Review of Policy Research - Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ropr.12316 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Hoppe, T.; van den Berg, M.M.; Coenen, F.H. Reflections on the Uptake of Climate Change Policies by Local Governments: Facing the Challenges of Mitigation and Adaptation. Energy, Sustainability and Society 2014, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.-W.; Fang, W.-T.; Yeh, S.-C.; Liu, S.-Y.; Tsai, H.-M.; Chou, J.-Y.; Ng, E. A Nationwide Survey Evaluating the Environmental Literacy of Undergraduate Students in Taiwan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwana, D.; Engineer, P.; Dabhi, A.; Chudasama, H. Sampling Methods in Research: A Review. Int. J. Trend Sci. Res. Dev. 2023, 7, 762–768. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, S.-C.; Yeh, T.-H.; Wu, A.-W.; Wu, H.C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Lin, P.-H. Development of the climate change literacy framework and baseline survey in Taiwan. Cities Plan. 2024, 51, 188–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbling, M.; Auer, D.; Meierrieks, D.; Mistry, M.; Schaub, M. Climate Change Literacy and Migration Potential: Micro-Level Evidence from Africa. Climatic Change 2021, 169, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transforming Administrative Policy - Christensen - 2002 - Public Administration - Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-9299.00298 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Bremer, S.; Glavovic, B.; Meisch, S.; Schneider, P.; Wardekker, A. Beyond Rules: How Institutional Cultures and Climate Governance Interact. WIREs Climate Change 2021, 12, e739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengö, M.; Andersson, E. Solutions-Oriented Research for Sustainability: Turning Knowledge into Action. Ambio 2022, 51, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, R.; van der Sluijs, J. Bridging Different Ways of Knowing in Climate Change Adaptation Requires Solution-Oriented Cross-Cultural Dialogue. Front. Clim. 2025, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostrom, A.; Hayes, A.L.; Crosman, K.M. Efficacy, Action, and Support for Reducing Climate Change Risks. Risk Analysis 2019, 39, 805–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S. Green Identity, Green Living? The Role of pro-Environmental Self-Identity in Determining Consistency across Diverse pro-Environmental Behaviours. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linking Organizational Context and Managerial Action: The Dimensions of Quality of Management - Ghoshal - 1994 - Strategic Management Journal - Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://sms.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/smj.4250151007 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Paillé, P.; Francoeur, V. Enabling Employees to Perform the Required Green Tasks through Support and Empowerment. Journal of Business Research 2022, 140, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Top Management Support as a Catalyst: Unpacking the Influence of Green Culture, Green HRM, and Green Work Engagement on Employee Ecological Behaviour | Journal of Management Development | Emerald Publishing. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/jmd/article/doi/10.1108/JMD-07-2024-0240/1268856/Top-management-support-as-a-catalyst-unpacking-the (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Organizational Support for Employees: Encouraging Creative Ideas for Environmental Sustainability - Catherine A. Ramus, 2001. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.2307/41166090 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Promoting Pro-Environmental Behaviours at Work: The Role of Green Organizational Climate and Supervisor Support / Fomentando Las Conductas Proambientales En El Trabajo: El Papel Del Clima Organizacional Verde y El Apoyo Del Supervisor - Patrícia Leitão, Carla Mouro, Ana Patrícia Duarte, Sílvia Luís, 2024. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/21711976241263474 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Albrecht, S.L.; Dalton, J.R.; Kavadas, V. Employee Pro-Environmental Proactive Behavior: The Influence of pro-Environmental Senior Leader and Organizational Support, Supervisor and Co-Worker Support, and Employee pro-Environmental Engagement. Front. Sustain. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riege, A.; Lindsay, N. Knowledge Management in the Public Sector: Stakeholder Partnerships in the Public Policy Development. Journal of Knowledge Management 2006, 10, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, F. The polity of implementation: Organizational and institutional arrangements in policy implementation. Governance 2022. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gove.12677 (accessed on 16 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Kay, B. Learning While Transforming: Solution-Oriented Learning for Urban Sustainability in Phoenix, Arizona. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2015, 16, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Hao, J.L.; Zheng, C.; Yu, S.; Wu, W. Applying Social Cognitive Theory to the Determinants of Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviour Towards Renovation Waste Minimization: In Pursuit of a Circular Economy. Waste Biomass Valor 2022, 13, 3739–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applying Social Cognitive Theory to the Determinants of Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviour Towards Renovation Waste Minimization: In Pursuit of a Circular Economy | Waste and Biomass Valorization. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12649-022-01828-4 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Battilana, J.; D’Aunno, T. Institutional Work and the Paradox of Embedded Agency. In Institutional Work: Actors and Agency in Institutional Studies of Organizations; Leca, B., Suddaby, R., Lawrence, T.B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2009; pp. 31–58. ISBN 978-0-521-51855-0. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, L.L.; Mumby, D.K. The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Communication: Advances in Theory, Research, and Methods; SAGE Publications, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4833-0997-2. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Description | Freq. | Percent | Cum. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 889 | 45.82 | 45.82 |

| Female | 1,051 | 54.18 | 100.00 | |

| Age (years) | 29 years and under | 270 | 13.92 | 13.92 |

| 30-39 | 626 | 32.27 | 46.19 | |

| 40-49 | 621 | 32.01 | 78.20 | |

| 50-59 | 343 | 17.68 | 95.88 | |

| 60-69 | 80 | 4.12 | 100.00 | |

| Education level | Junior high school | 7 | 0.36 | 0.36 |

| Senior high school | 34 | 1.75 | 2.11 | |

| Junior college | 115 | 5.93 | 8.04 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 998 | 51.44 | 59.48 | |

| Master’s degree | 745 | 38.40 | 97.89 | |

| Doctoral degree (PhD) | 41 | 2.11 | 100.00 | |

| Seniority | 0-9 | 867 | 44.69 | 44.69 |

| 10-19 | 646 | 33.30 | 77.99 | |

| 20-29 | 263 | 13.56 | 91.55 | |

| 30-39 | 155 | 7.99 | 99.54 | |

| 40 years and over | 9 | 0.46 | 100.00 | |

| Government Level | Central | 1,106 | 57.01 | 57.01 |

| Local | 834 | 42.99 | 100.00 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Variables | Action | |||||

| CK | 0.021 | 0.017 | 0.013 | 0.020 | 0.016 | 0.013 |

| (0.018) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.018) | (0.013) | (0.013) | |

| IK | -0.024 | -0.019 | -0.018 | -0.018 | -0.016 | -0.015 |

| (0.021) | (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.021) | (0.015) | (0.015) | |

| SK | 0.041*** | 0.0068 | -0.0046 | 0.039*** | 0.0049 | -0.0067 |

| (0.0086) | (0.0061) | (0.0062) | (0.0086) | (0.0061) | (0.0063) | |

| Sensitivity | - | -0.015 | -0.0049 | - | -0.011 | -0.00088 |

| - | (0.025) | (0.024) | - | (0.025) | (0.025) | |

| values | - | 0.040 | -0.00088 | - | 0.037 | -0.0015 |

| - | (0.037) | (0.037) | - | (0.037) | (0.037) | |

| Self-Efficacy | - | 0.61*** | 0.56*** | - | 0.61*** | 0.56*** |

| - | (0.020) | (0.021) | - | (0.020) | (0.021) | |

| Sense of Hope | - | 0.0093 | 0.020 | - | 0.012 | 0.021 |

| - | (0.022) | (0.021) | - | (0.022) | (0.021) | |

| Identity | - | 0.13*** | 0.14*** | - | 0.13*** | 0.13*** |

| - | (0.023) | (0.023) | - | (0.023) | (0.023) | |

| Once | - | - | 0.053* | - | - | 0.046 |

| - | - | (0.029) | - | - | (0.029) | |

| Related | - | - | 0.067*** | - | - | 0.065*** |

| - | - | (0.014) | - | - | (0.014) | |

| Support | - | - | 0.026* | - | - | 0.028** |

| - | - | (0.014) | - | - | (0.014) | |

| Gender | 0.067** | 0.0030 | -0.0066 | 0.050 | 0.0029 | -0.0035 |

| (0.034) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.034) | (0.024) | (0.024) | |

| Age | 0.0024 | -0.0033* | -0.0029 | 0.00079 | -0.0039** | -0.0035* |

| (0.0027) | (0.0019) | (0.0018) | (0.0027) | (0.0019) | (0.0019) | |

| Edu | 0.056*** | 0.026*** | 0.020*** | 0.064*** | 0.032*** | 0.024*** |

| (0.011) | (0.0075) | (0.0074) | (0.011) | (0.0076) | (0.0076) | |

| Seniority | 0.0011 | 0.0035* | 0.0030 | 0.0022 | 0.0043** | 0.0037* |

| (0.0028) | (0.0019) | (0.0019) | (0.0028) | (0.0019) | (0.0019) | |

| Constant | 1.79*** | -0.0012 | 0.13 | 2.09*** | 0.060 | 0.14 |

| (0.19) | (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.24) | (0.18) | (0.18) | |

| City | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Observations | 1,940 | 1,940 | 1,940 | 1,940 | 1,940 | 1,940 |

| R-squared | 0.043 | 0.542 | 0.556 | 0.075 | 0.548 | 0.560 |

| Central | Local | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. | Coef. | Std. | ||

| CK | 0.019 | (0.017) | 0.0053 | (0.020) | |

| IK | -0.016 | (0.019) | -0.014 | (0.023) | |

| SK | -0.016* | (0.0084) | 0.0024 | (0.0096) | |

| Sensitivity | -0.0038 | (0.033) | 0.0052 | (0.038) | |

| values | 0.013 | (0.049) | -0.011 | (0.058) | |

| Self-Efficacy | 0.55*** | (0.028) | 0.57*** | (0.034) | |

| Sense of Hope | 0.032 | (0.028) | 0.015 | (0.035) | |

| Identity | 0.13*** | (0.029) | 0.13*** | (0.036) | |

| Once | 0.016 | (0.040) | 0.093** | (0.043) | |

| Related | 0.088*** | (0.019) | 0.023 | (0.023) | |

| Support | 0.017 | (0.018) | 0.054** | (0.024) | |

| Constant | -0.16 | (0.27) | 0.24 | (0.26) | |

| Control var. | Yes | Yes | |||

| City | Yes | Yes | |||

| Observations | 1,106 | 834 | |||

| R-squared | 0.561 | 0.575 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).