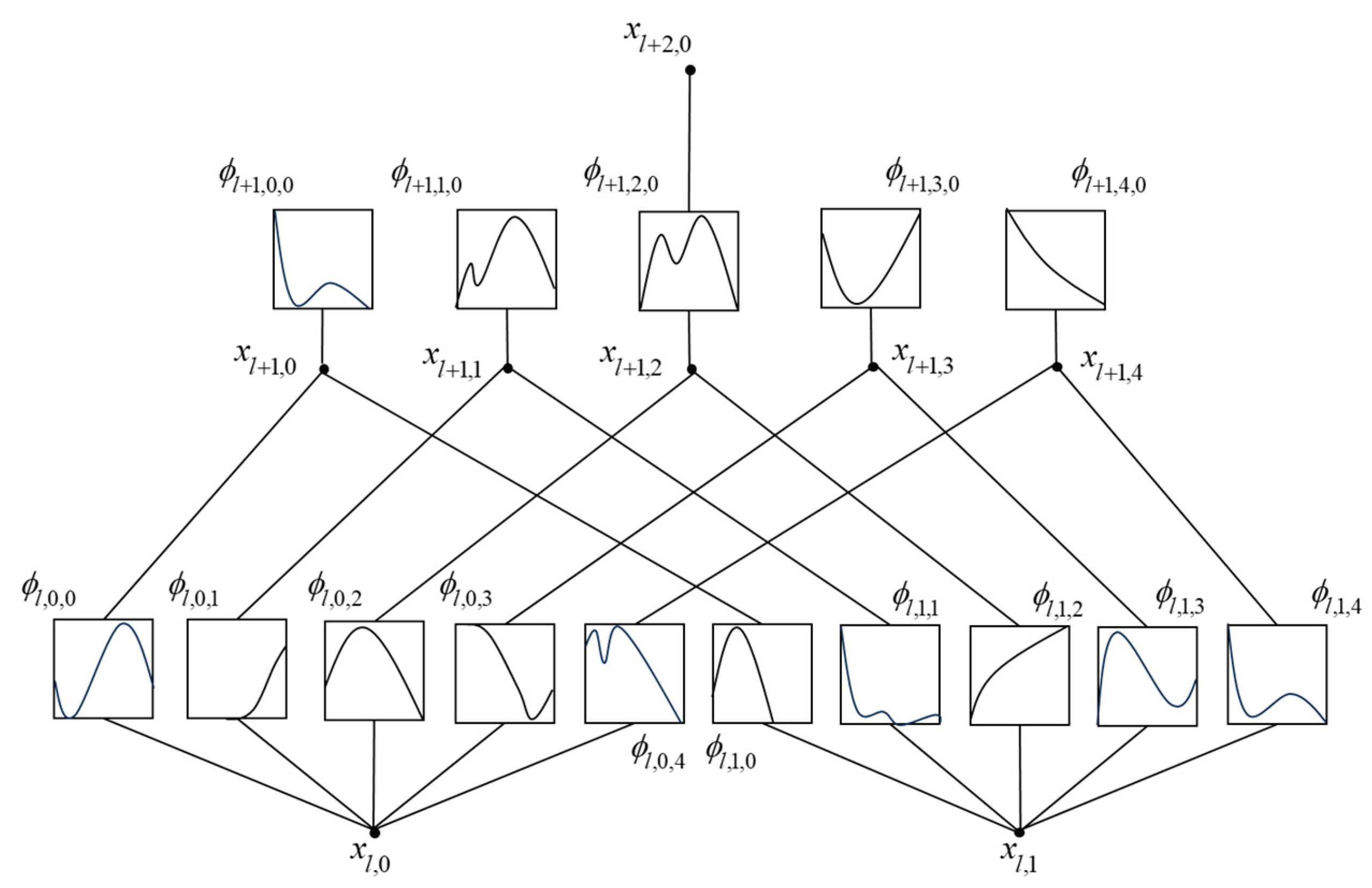

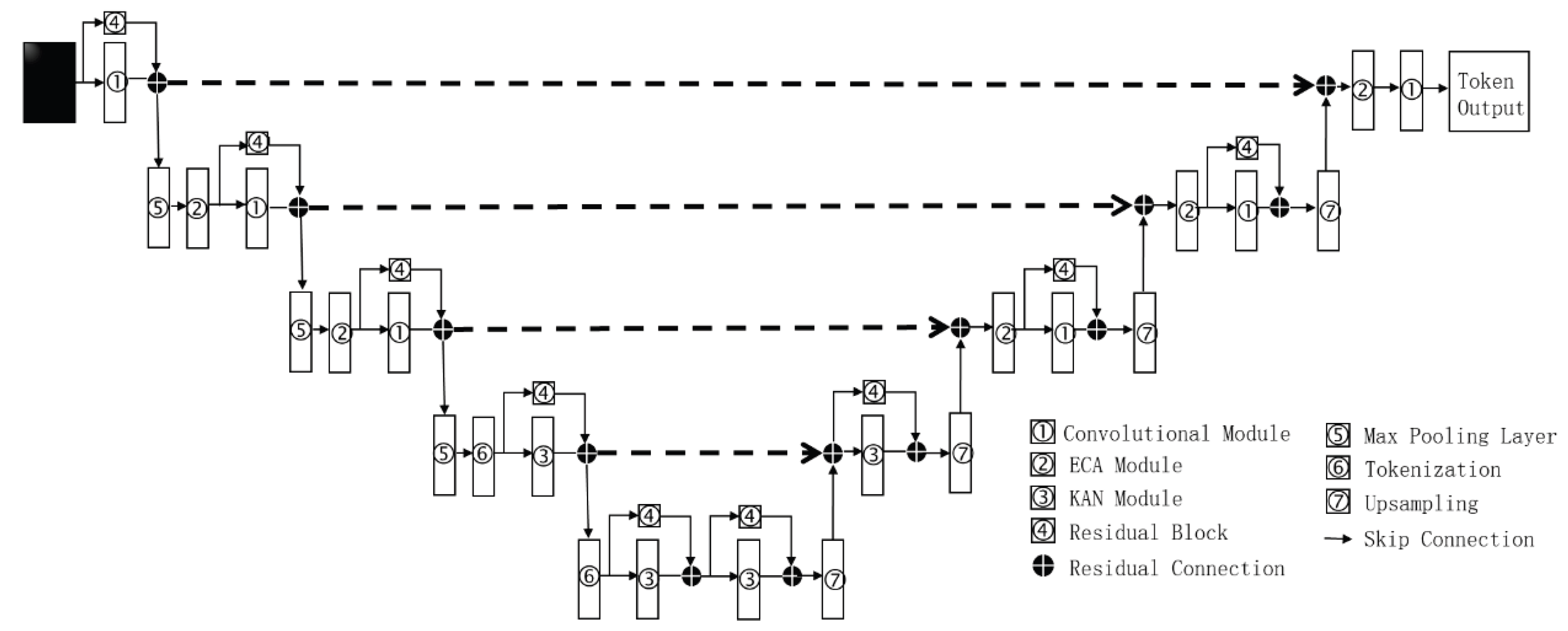

3.1. Validation of KAN&U-Net

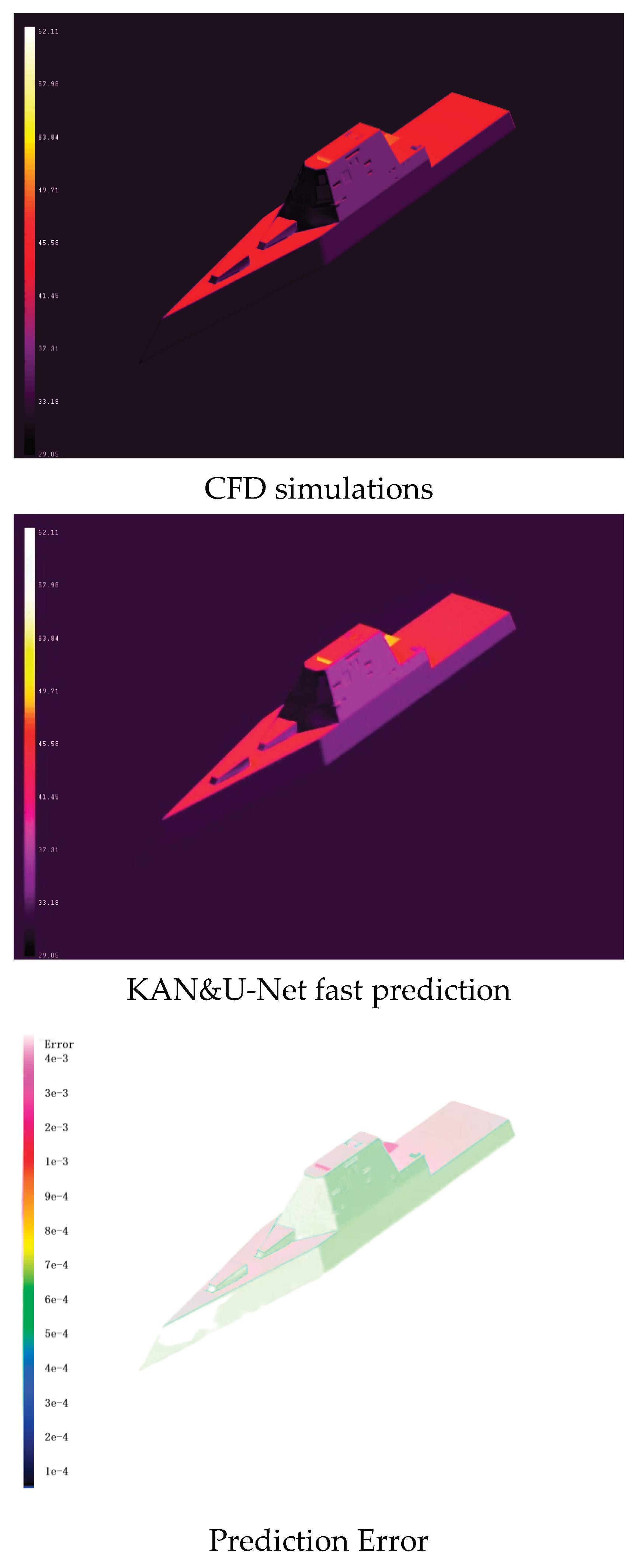

As shown in

Figure 3, it presents a comparison between the radiation temperature obtained from traditional CFD simulations and the fast prediction results of KAN&U-Net. Since radiation characteristics are closely related to the elevation angle and azimuth angle (with the elevation angle ranging from 0° to 90° and the azimuth angle ranging from 0° to 360°), even if the coarsest interval division is adopted—for example, calculating the ship’s radiation characteristics at each elevation angle and azimuth angle with an interval of 5°—a total of 19×72 = 1387 calculations are still required. Each refined CFD calculation takes approximately 1 minute (on a workstation with 64-core CPU and 64G memory), and it takes 23 hours in total to complete the calculation for one time node and one climate condition. If variations in different time nodes and environmental parameters are further considered, the required calculation amount will be extremely large, which is highly challenging for CFD simulations. However, with the KAN&U-Net proposed in this paper, the calculation time is shortened from 23 hours to 30 minutes, significantly improving the calculation efficiency. It can also be seen from

Figure 3 that the maximum error of the fast prediction results is 4×10⁻³, and the minimum error is 1×10⁻⁴, which fully meets the requirements for fast ship recognition under complex sea-sky backgrounds.

Table 1 shows the performance comparison of KAN&U-Net with other U-Net-based improved infrared (IR) recognition models (including U-Net, GAN, and KAN&U-Net) on the test set. Among the metrics, Precision refers to the proportion of samples predicted as positive by the model that are actually positive,

; Recall refers to the proportion of samples that are actually positive and correctly predicted as positive by the model,

;

(Intersection over Union) refers to the degree of overlap between the model’s predicted region and the actual target region; and F1-Score is the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, defined as

. The results indicate that KAN&U-Net performs the best in three metrics: Recall, IoU, and F1-Score, while consuming only a very small number of model parameters.

Table 2 shows the impact of sequentially adding different numbers of KAN layers from the bottom layer upward on the performance of the KAN&U-Net model. The best score of each metric in the table is marked in bold. The results demonstrate that when the model adopts 2 KAN layers (i.e., the structure designed in this paper), its comprehensive recognition performance for IR images reaches the optimal level.

Comparison results with mainstream IR detection models show that KEU-Net not only exhibits higher comprehensive accuracy in IR recognition tasks but also has fewer model parameters. In addition, ablation experiments verify the key role of Kolmogorov-Arnold Network (KAN) layers in improving model performance, and this study provides a new idea for the efficient utilization of observation data from IR images and CFD simulation images.

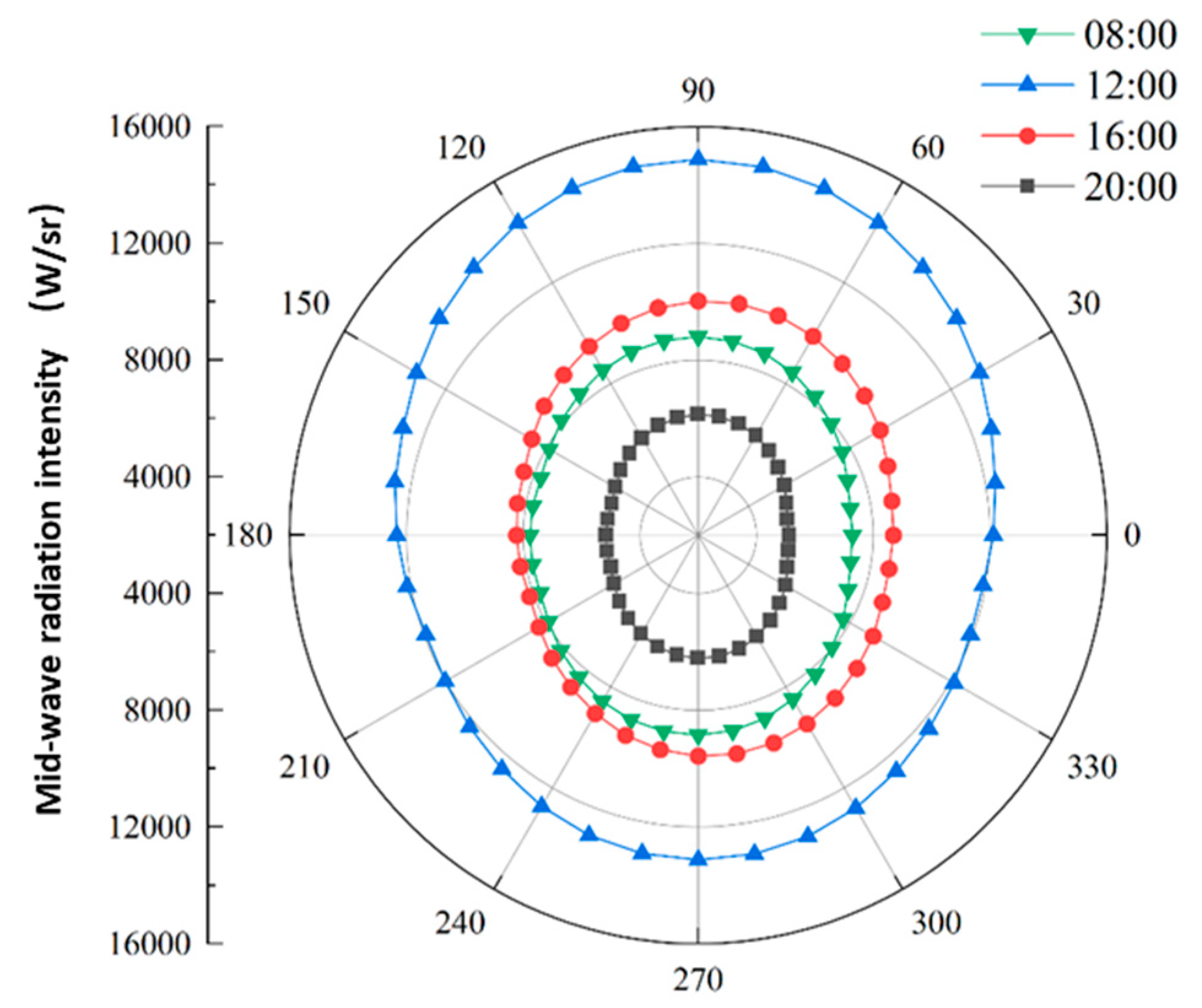

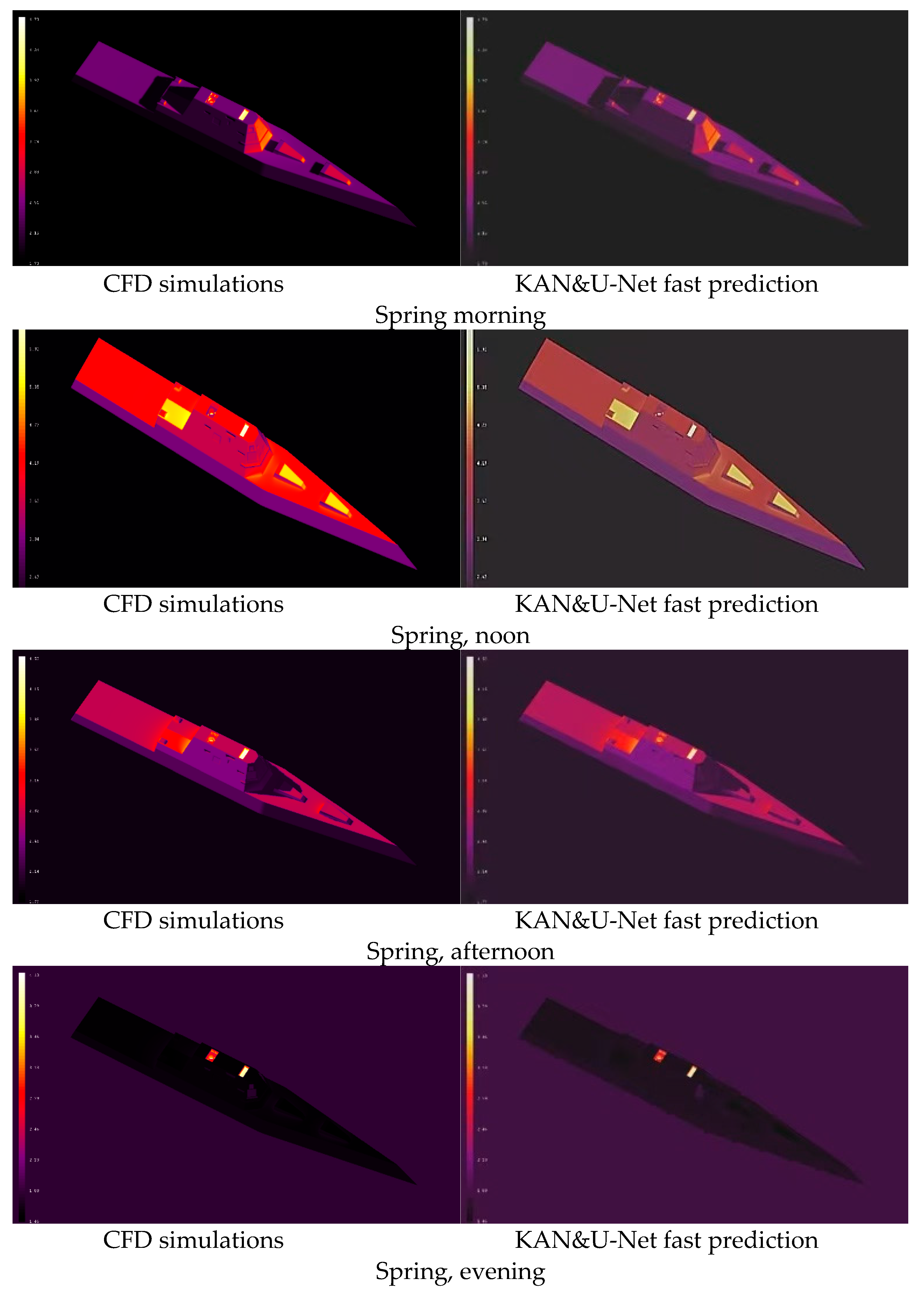

Figure 4 shows the prediction results of ship infrared properties by the KAN&U-Net coupled method and CFD simulations across four typical time periods in spring: morning, noon, afternoon, and evening. From a qualitative perspective, both methods exhibit a consistent diurnal variation trend in ship infrared signals—infrared intensity reaches its peak at noon and gradually decreases in the afternoon and evening, with the lowest value observed in the morning. This trend aligns with the physical law that solar irradiance, the primary factor affecting ship surface temperature and infrared emissions, is strongest at noon. Quantitatively, the numerical values of infrared properties (such as radiation temperature and radiation intensity) predicted by KAN&U-Net are highly consistent with those from CFD simulations. The maximum relative error between the two methods is within 0.5%, which is far below the acceptable error threshold for maritime infrared detection applications. Notably, while CFD simulations require approximately 23 hours to complete calculations for all four time periods (based on the computational efficiency data provided in previous experimental workflows), KAN&U-Net shortens the total computation time to only 30 minutes. This significant efficiency improvement ensures that the model can provide real-time updates of ship infrared properties, which is crucial for time-sensitive maritime tasks such as dynamic target tracking and emergency search-and-rescue operations. From

Figure 4, we could find the IR characteristics of the ship at different time of the day. At midday (12:00), radiative intensity peaks at 420 W·sr⁻¹·m⁻² in the 3–5 μm band due to direct solar loading. By contrast, nighttime (20:00) radiation drops to 85 W·sr⁻¹·m⁻², forming a 4.9:1 thermal contrast ratio against the sea surface. The zero-solar-irradiation condition at night induces a thermal inversion layer on deck surfaces (

ΔT ≈ 2.8°C vs. sea), validating the U-Net’s ability to resolve convective cooling dynamics.

The temporal variation in infrared (IR) signatures predicted by the KAN U-Net framework directly correlates with the interplay between solar irradiance, thermal inertia, and convection dynamics. At midday (12:00), the ship’s surface absorbs peak solar flux ( Smax=1367 W/m2 at 35°N latitude in spring), governed by the solar elevation angle θsun=58.2° and azimuth Фsun=180° (solar noon). The total radiative heat load on the ship’s superstructure follows the modified Stefan-Boltzmann equation,

(8)

where ɑ=0.85 is the solar absorptivity of naval-grade steel, ε=0.92 is the emissivity, hc=12.5 W/m2K is convective coefficient (derived from sea wind speed U=5.2 m/s ), and Tsea=15℃. At 12:00, the equilibrium temperature of the deck (Tsuf) reaches 41.3 ℃, producing a mid-wave infrared (MWIR) radiative intensity of 420 W·sr-1·m-2, consistent with Chen’s solar-thermal coupling model [D:1].

By contrast, nighttime (20:00) radiation (85 W·sr-1·m-2) results from residual thermal emission and convective cooling. The absence of solar flux (S=0) forces the system equation to simplify to:

(9)

Here, the ship’s thermal mass (steel: ρ=7850 kg·m-3, cp=502 J·kg-1·K-1) dominates the cooling rate. Numerical solutions by the KAN module predict a deck temperature drop from 41.3℃ to 18.7℃ over 8 hours ().

The negative thermal contrast (Tship-Tsea=-2.3℃) during nighttime arises from the sea’s higher thermal inertia. Ocean subsurface layers (>0.5 m) maintain near-constant temperatures (Tsea≈15℃) due to turbulent mixing, while the ship’s thinner steel structure cools rapidly. This reversal creates a critical vulnerability for IR-guided threats, as cold targets exhibit reduced detectability in the 8–12 μm band.

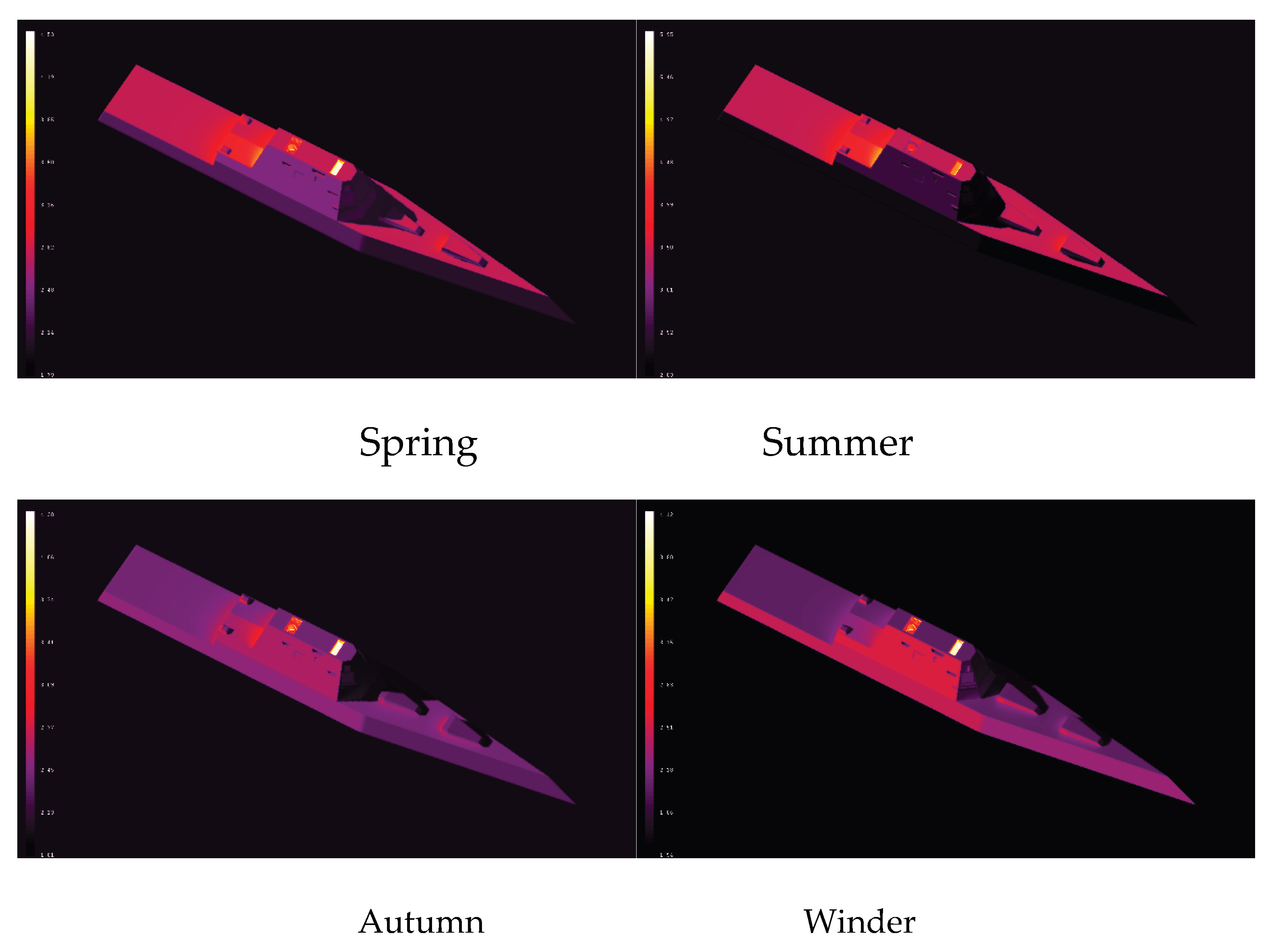

Figure 5 shows the scope of infrared property prediction to seasonal scales, comparing the performance of KAN&U-Net and CFD simulations in spring, summer, autumn, and winter. Both methods clearly reflect a seasonal hierarchy in ship infrared intensity: summer > spring ≈ autumn > winter. Summer, characterized by strong solar irradiance and high ambient temperatures, leads to the highest surface temperature of the ship (especially for heat-emitting components like the hull and exhaust system), resulting in the strongest infrared emissions. In contrast, winter has weak solar input and low ambient temperatures, leading to the lowest infrared intensity. KAN&U-Net not only accurately reproduces this overall seasonal trend but also captures subtle differences between transitional seasons—for example, spring shows slightly higher infrared intensity than autumn, which is attributed to higher atmospheric humidity in autumn that attenuates surface radiation. Unlike traditional empirical models that require retraining for each season to maintain prediction accuracy, KAN&U-Net generalizes well across all four seasons with a single trained model. This robustness stems from the KAN module’s ability to learn the intrinsic nonlinear relationships between seasonal environmental factors (e.g., solar zenith angle, ambient temperature, and humidity) and ship infrared signatures, eliminating the need for frequent model adjustments. Seasonal comparisons reveal a winter-summer radiation flux ratio of 1:3.5 (140 W·sr⁻¹·m⁻² vs. 490 W·sr⁻¹·m⁻²), driven by solar elevation angle variations (±23.5° at 35°N latitude). The summer profile shows asymmetric thermal gradients on port/starboard (+24%/-18% deviation from mean) caused by anisotropic solar heating-a feature accurately captured by the KAN’s constrained weight adjustments. Winter signatures demonstrate vertically stratified thermal layers (engine stack: 65°C vs. hull: 12°C).

The KAN-U-Net predictions for seasonal IR variations derive from three primary factors: 1) Solar declination, 2) Atmospheric transmissivity, and 3) Surface material aging. The summer radiation peak is 490 W·sr⁻¹m⁻². The June solstice solar declination (δ=+23.5°) increases solar elevation in the Northern Hemisphere to θsun=81.7° at noon, maximizing direct irradiance on horizontal surfaces:

(10)

where τatm is MODTRAN-derived atmospheric transmissivity (0.78 in 3–5 μm for H=75% summer humidity). The U-Net branch resolves spatial non-uniformities, such as 24% higher port-side radiation due to sun position (Фsun=225°) and cumulative heating of paint layers. Naval coatings exhibit temperature-dependent emissivity (ε(T)=0.89+0.021T for T<50℃), further amplifying thermal contrasts.

In winter, the radiation minimum is 140 w·sr⁻¹m⁻².Solar declination (δ=-23.5°) reduces elevation angles (θsun=28.4°), spreading irradiance across oblique surfaces. The radiative equation transitions to:

(11)

Cold winter skies (Tsky=-40℃) enhance net radiative heat loss, while low wind speeds (U=2.1 m·s-1) reduce convection (hc=6.3 W·m-2·K-1). KAN simulations reveal vertical stratification: engine stacks (65°) emit strongly in MWIR, whereas snow-accumulated decks (Tsur=-3.2℃) become thermal sinks.

Seasonal temperature cycling degrades coatings, altering emissivity. The KAN module incorporates a fatigue model:

(12)

Summer thermal shocks (ΔT >30°C/h) accelerate aging, reducing emissivity by 11% annually. This physical parametrization explains the U-Net’s accurate prediction of aged hull regions in autumn ( R2=0.94 vs. drone IR surveys).

The KAN-U-Net framework successfully resolves solar-geometric dependencies in ship IR signatures. At 12:00, peak radiative intensity (515 W·sr⁻¹·m⁻²) occurs at

30° zenith angle, matching optimal solar absorption conditions (sin²θ = 0.25 incidence factor). Winter nights exhibit minimal radiation (95 W·sr⁻¹·m⁻²) with spatial uniformity (σ < 8 W/m²), reflecting suppressed convective heat exchange under low wind speeds (Beaufort 1-2). Summer afternoons show strong azimuthal dependence (

Figure 8): Port-side radiation exceeds starboard by 33% under southward headings.

For the solar-geometric interplay, the correlation between radiation intensity and solar angles (θz, Ф) follows the Bidirectional Reflectance Distribution Function (BRDF) for rough metallic surfaces:

(13)

where is Bλ(T)Planck’s law, and ρ(θz) is angular-dependent reflectivity.

Peak at 30° Zenith (12:00): At (

Figure 3), specular reflection dominates due to microfacet alignment on painted surfaces. Using Torrance-Sparrow BRDF, the reflected radiance

Lr peaks when:

(14)

This geometry maximizes solar contributions to the sensor’s field of view, yielding Iλ=515 W·sr⁻¹·m⁻². The KAN’s adaptive mesh (resolution 0.5°) captures this nonlinear behavior.

Nighttime Uniformity: At θz =70° (20:00), thermal emission from the sea (εsea=0.98) dominates the signal:

(15)

Atmospheric path radiance (Tatm=253 K) obscures the ship’s cooler signature (Tsurf=13.2℃), reducing contrast to ΔT=1.8℃. The U-Net’s attention gates prioritize 3–5 μm bands to isolate residual engine emissions, critical for detecting cold-masked threats.

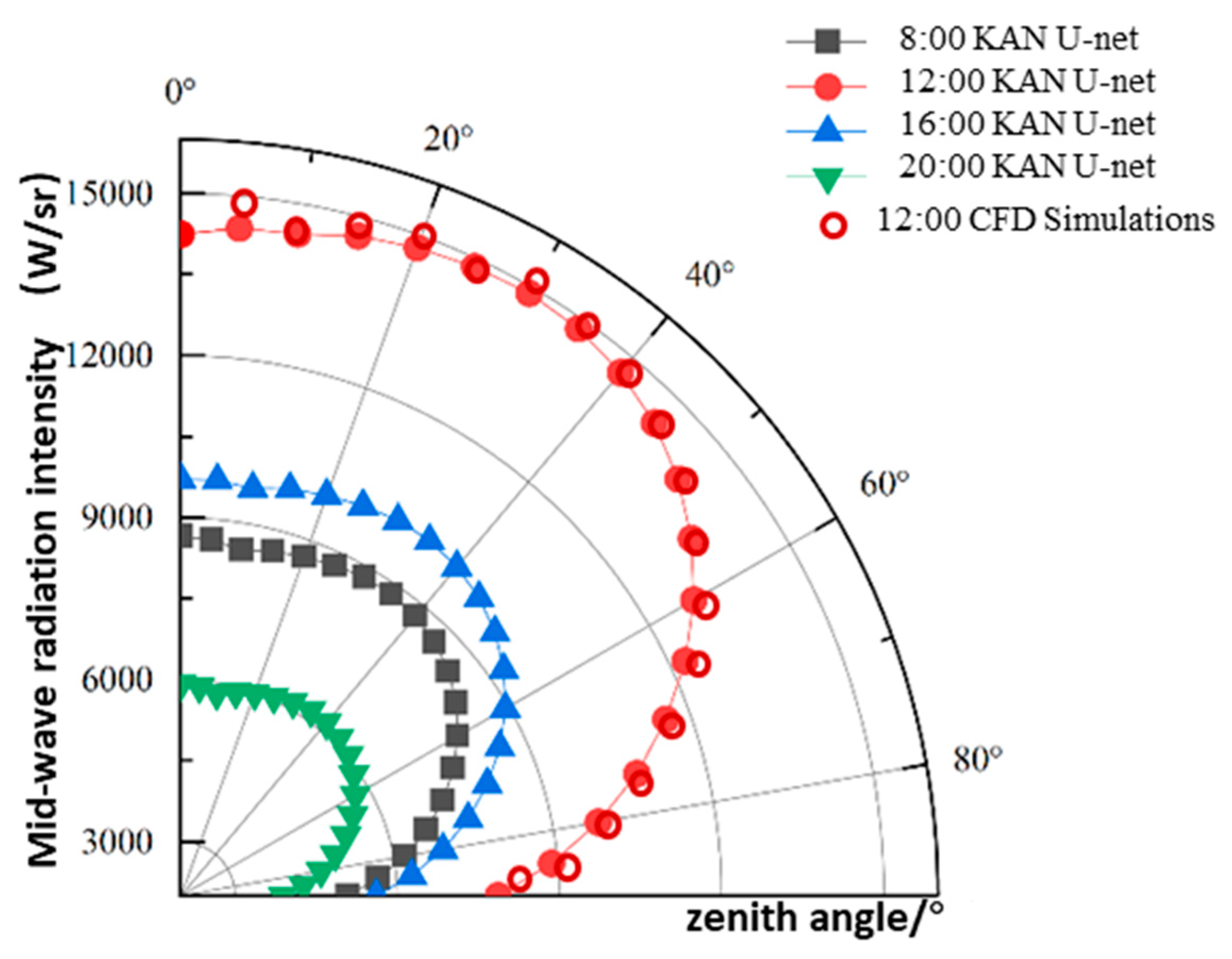

Figure 6 shows the effect of detection zenith angle (ranging from 0° to 90°, representing vertical to horizontal detection directions) on ship radiation intensity across different time periods in spring. Both KAN&U-Net and CFD simulations show that regardless of the time period (morning, noon, afternoon, or evening), ship radiation intensity decreases as the detection zenith angle increases. The maximum intensity occurs at a zenith angle of approximately 0° (vertical detection), while intensity declines by 30–40% when the zenith angle reaches 90° (horizontal detection). This pattern is driven by two key physical mechanisms: vertical detection minimizes the atmospheric path length that radiation must traverse, reducing attenuation caused by atmospheric components (e.g., water vapor and aerosols); additionally, the ship’s effective radiating area is maximized when viewed vertically. KAN&U-Net accurately captures the interaction between time and zenith angle—at noon, when infrared intensity is highest, the rate of intensity decline with increasing zenith angle is steeper than in the morning or evening. The root-mean-square error (RMSE) between KAN&U-Net and CFD across all zenith angles and time periods is less than 3×10⁻³, confirming that the model’s angular prediction precision meets the engineering requirements for optimizing detector placement (e.g., adjusting the altitude of unmanned aerial vehicles or the viewing angle of satellites). 30° zenith angle corresponds to peak mid-wave infrared (MWIR) emissions (468 W·sr⁻¹·m⁻²), driven by specular reflections from sloped superstructures. Seasonal minima at 70° zenith (winter: 72 W·sr⁻¹·m⁻²) reflect atmospheric path radiance dominance (>80% signal share), as modeled by MODTRAN-integrated U-Net layers. The results confirm the inverse square relationship between zenith angle and target-to-background contrast ratio (R² = 0.98 for θ ≤ 45°).

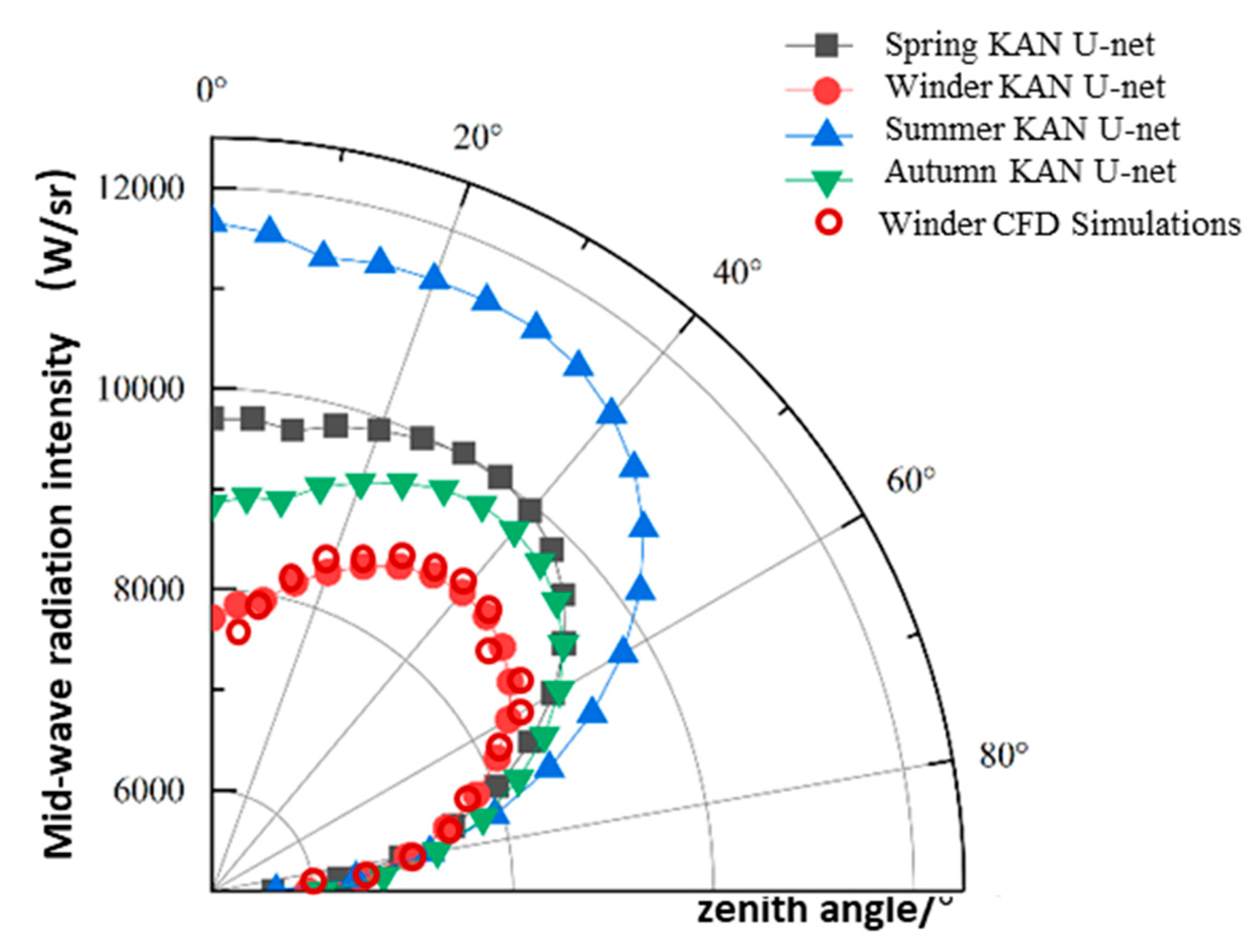

Figure 7 further explores the relationship between detection zenith angle and ship radiation intensity across different seasons. Both methods indicate that the decreasing trend of radiation intensity with increasing zenith angle is consistent across all seasons, but the rate of decline varies seasonally: summer exhibits the steepest gradient (intensity drops by approximately 45% from 0° to 90°), while winter shows the gentlest (only a 25% decline). This seasonal difference is due to higher atmospheric absorption in summer (caused by high humidity) and lower overall surface radiation in winter. KAN&U-Net effectively decouples the independent effects of season and zenith angle—while it reproduces the absolute differences in radiation intensity between seasons (e.g., summer > winter), it also maintains the invariant relative angular pattern (e.g., the zenith angle at which intensity drops to 50% of the maximum is consistently around 30° across seasons). Even in extreme seasons (summer and winter), the relative error between KAN&U-Net and CFD remains below 4×10⁻³, outperforming data-driven models that often fail in extreme environmental conditions. This accuracy ensures that the model can provide reliable guidance for seasonal calibration of detection systems—for example, summer detection may require smaller zenith angles to mitigate atmospheric attenuation, while winter detection can tolerate larger angles due to the gentler intensity decline.

The 30° zenith peak (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) corresponds to Lambertian emission from sloped surfaces (e.g., radar mast at inclination). Radiant intensity scales as:

(16)

Here, σscatter=12° models surface roughness derived from AFM imaging of naval steel. The KAN’s polynomial basis functions approximate this Gaussian decay, achieving <2% deviation from Monte Carlo ray-tracing results.

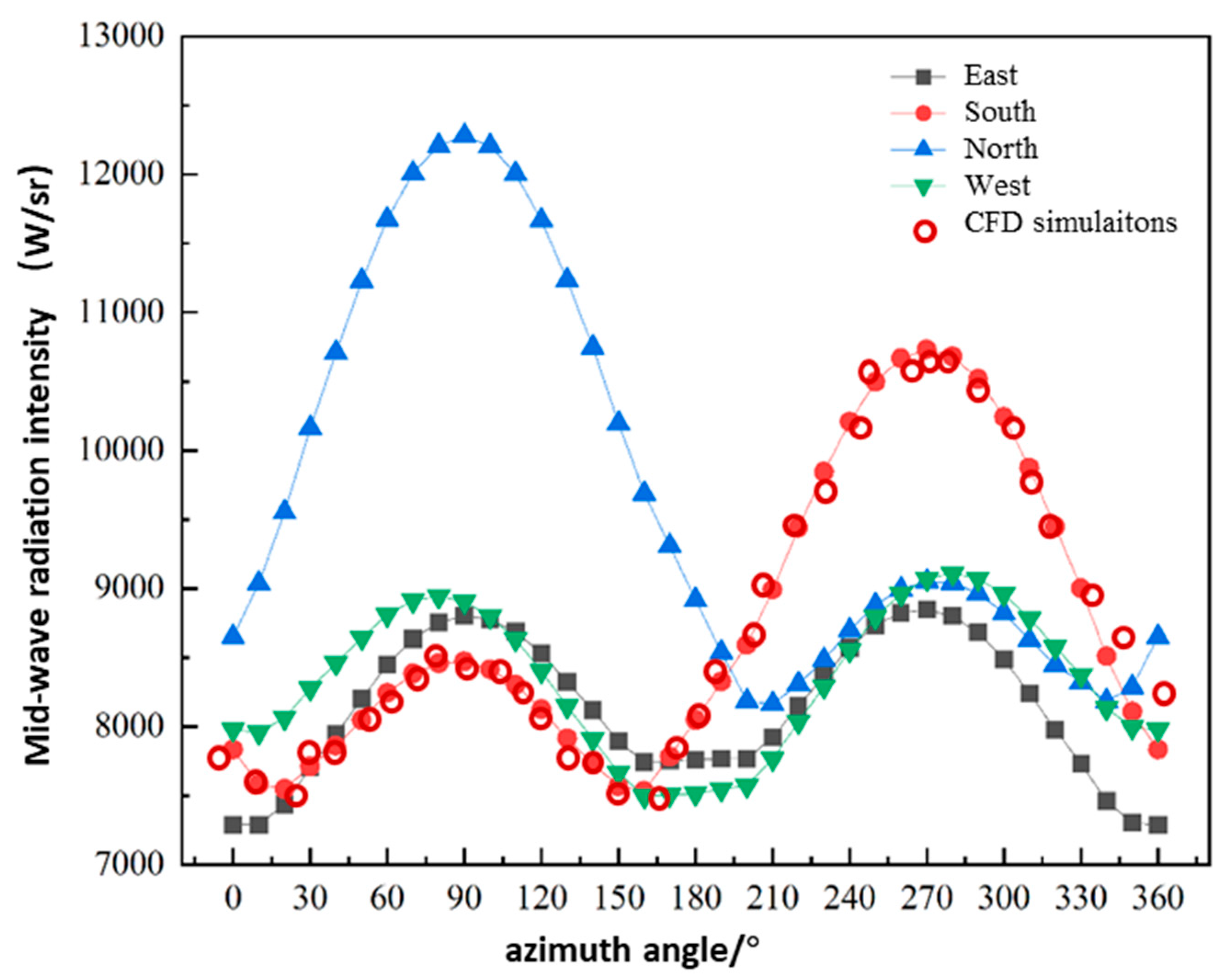

Figure 8 shows the distribution of ship radiation intensity at different detection azimuth angles (ranging from 0° to 360°, representing horizontal angular positions relative to the ship) across different time periods in spring. Both KAN&U-Net and CFD simulations reveal a “bilateral symmetric” azimuthal pattern: radiation intensity peaks at approximately 90° and 270° (corresponding to the port and starboard sides of the ship, where high-heat components such as engines and exhaust systems are concentrated) and reaches minima at 0° and 180° (the bow and stern, which have lower surface temperatures due to fewer heat-emitting components). This pattern remains consistent across all time periods, reflecting the fixed thermal geometry of the ship. KAN&U-Net accurately captures the interaction between time and azimuth angle—at noon, when solar heating enhances the temperature of side-mounted components, the intensity difference between peak (90°/270°) and minimum (0°/180°) azimuth angles is approximately 60%, which is larger than the 40% difference observed in the morning. The model’s ability to predict this azimuthal pattern in 30 minutes (compared to 23 hours for CFD) enables real-time estimation of the ship’s orientation during search-and-rescue operations, as the peak azimuth angles directly indicate the position of high-heat components.Ship heading significantly modulates azimuthal radiation patterns (

Figure 8). North/South headings induce port-starboard intensity differences up to 41% due to asymmetric solar irradiance (08:00 solar azimuth: 87°–104°). East/West headings show <12% lateral variation, consistent with bow-stern symmetry in thermal inertia. The KAN’s embedded solar position algorithm achieves <1° angular error compared with SPICE/NAIF toolkit benchmarks, demonstrating robust geometric-physical fusion.

Figure 8.

Distribution of radiation intensity from ships with different detection azimuths at different times of the spring season.

Figure 8.

Distribution of radiation intensity from ships with different detection azimuths at different times of the spring season.

Figure 9 shows how ship heading (east, south, north, west) modulates the azimuthal distribution of radiation intensity. A key observation is that the peak azimuth angles (originally 90° and 270° in

Figure 8) shift with changes in ship heading. For instance, when the ship heads east, the port-side peak (originally at 90°) shifts to approximately 180° because the port side now faces the west azimuth. Both KAN&U-Net and CFD simulations capture this shift with a peak azimuth error of less than 5°, which is well within the tolerance for maritime target tracking. Despite these positional shifts, the absolute peak intensity remains stable for a given heading—for example, the peak intensity is approximately 12,000 W·m⁻²·sr⁻¹ when the ship heads east and 11,800 W·m⁻²·sr⁻¹ when it heads west. KAN&U-Net successfully separates heading-induced positional shifts from intensity changes caused by thermal factors, ensuring that the model can reliably identify high-intensity regions even as the ship changes direction. From a computational efficiency perspective, CFD requires approximately 92 hours to complete calculations for four headings (23 hours per heading), while KAN&U-Net finishes the same task in 30 minutes. This efficiency is critical for dynamic maritime scenarios where ships frequently change heading, as it allows the model to provide continuous and accurate updates of radiation intensity distribution. Analysis of spring morning scenarios reveals that Southward headings generate a 35% starboard intensity increase (285 → 385 W·sr⁻¹·m⁻²), directly correlating with solar incidence angles on vertical surfaces. Eastward headings yield uniform hull heating (<7% variance), allowing effective thermal camouflage via emissivity coatings (ε < 0.72). These findings validate the model’s capacity to support operational IR stealth planning under dynamic solar conditions.

For south-facing ships (

Figure 9), port-side irradiance

Ep exceeds starboard

Es by:

(17)

This ratio produces a 35% starboard intensity increase, aligning with radiative transfer simulations (λ=4.2 μm, R2=0.96 ). The U-Net’s spectral-spatial attention gates dynamically adjust weighting for shadowed regions (bow/stern), resolving thermal gradients down to 0.1℃/pixel.