Introduction

Robotic liver surgery is increasingly being recognized as the next step in minimally invasive procedures and is currently undergoing significant advancement. Its technology represents the most advanced form of minimally invasive surgery, though there are still some unresolved challenges regarding its implementation in clinical practice (28). The robotic system provides a stable visual platform, eliminates physiological tremors, enhances surgical precision, and offers better ergonomics through a seated operating position (1). Given these potential benefits, robotic assistance may be particularly well-suited for complex liver procedures, which require delicate tissue handling, highly accurate intracorporeal suturing, and intricate parenchymal dissection—followed by the need for meticulous bleeding and bile leak control. Parenchymal transection remains one of the most technically demanding aspects (2). Robotic hepatectomy is commonly used to treat liver tumors. For patients with large (≥ 5 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma, robotic hepatectomy has been shown to be a safe and feasible option. Giulianotti et al. first reported robotic-assisted laparoscopic hepatectomy (28). Since then, medical centers around the world have shared their experiences with this technique (29). The lack of specialized instruments and the development of various techniques have so far prevented the establishment of a standardized surgical approach. Nowadays, the increasing use of ICG-fluorescence imaging in patients undergoing minimally invasive resections for colorectal liver metastases, aiming to improve radical resection rates and the accuracy of tumor margin identification. At the same time colorectal cancer (CRC) remains one of the primary causes of cancer-related mortality, with liver metastases occurring in approximately 25–30% of patients (3). The presence of metastatic disease in the liver places a considerable burden on the healthcare system, not only by driving up costs and expenditures but also by increasing the need for and use of medical resources (4). Robot-assisted simultaneous colon and liver resections are becoming increasingly common as the use of robotic platforms grows in the surgical treatment of metastatic colon cancer. Nevertheless, this technique remains underexplored, with current evidence limited to case series. In this paper we focus on an overview of the recent advances in the surgical, robotic treatment of colorectal liver metastasis (CRLM).

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

The surgeons’ team compiled a Microsoft Excel Database, including demographic, clinical, surgical, and pathological data.

Literature Review

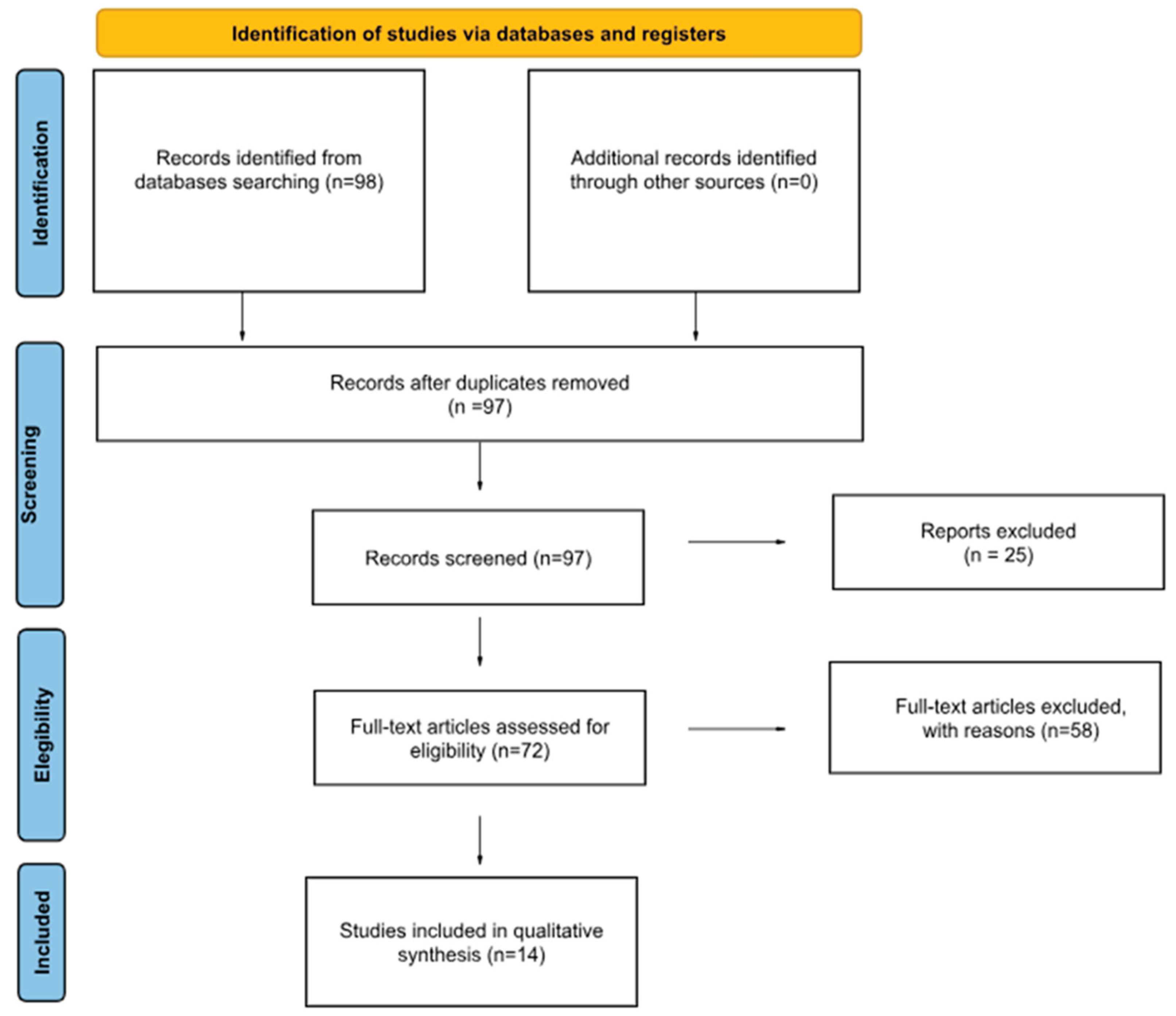

A narrative review of the literature was conducted. This review followed a narrative approach and has not been intended as a systematic review. The aim was to synthesize the most relevant literature on surgical and robotic management of CRLM. The search was narrowed to articles between 2010 and 2025. We searched on PUBMED and Cochrane Library; Studies were included if they were full-text articles or review or case reports published in English involving human adult participants (>18 years), and addressed aspects of the diagnosis, management, or treatment of CRLM. Studies were excluded if they were in other languages, without a visible abstract, not relevant.

The research was conducted using the following terms: “robotic liver resection AND colorectal metastasis”. Single case reports were included. The search showed 98 results. After removing one duplicate 97. Others 25 were excluded because in other languages or without a visible text or abstract.

58 papers were excluded because they were not relevant to our focus considering the topics covered ( because, after the research conducted through PubMed and Cochrane Library, even though they met the inclusion criteria regarding language and participants, we excluded from our discussion all works that did not address the treatment of liver metastases from colorectal cancer) ; for example in this part we excluded some papers about non-surgical treatments.

In the end 14 texts were included in our work as reported in our PRISMA Flowchart Diagram (

Figure 1) (26).

Results

A total of 14 studies that included patients who underwent RLR (robotic liver resections) in patients with CRLM were considered eligible for inclusion in our narrative review. Four of them were single case reports, one was a literature systematic review, one multicentric prospective and the others all monocentric studies (5 retrospective and 3 prospective). Four of them originated from Italy, two from the United States, two from Deutschland, one from Belgium, one from China, one from India, one from Brasil, one from Korea and one from Nederland. The indices analyzed were tabulated in

Table 1.

Main Outcomes

The 14 included studies analyzed ranged from single case reports to studies with hundreds of patients who underwent RAR , and the male sex was generally more prevalent. Among included patients, the ages ranged from 31 to 88 years. The primary tumor site was prevalent in the rectum (76%). CRLM were unilobar in 82% of patients.

Rahimli et al. (14) reported a prevalence of cirrhosis in 12 patients (10 Child A, 2 Child B) and in 14 patients was present hepatic steatosis, while the hepatitis was reported as follows: 2 patients with hepatitis B and one with hepatitis C.

All procedures were performed with the da Vinci Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Mountain View, CA, USA) in its subsequent models. In 6 studies the RLR was performed using the new da Vinci Xi. Out of 771 patients, 478 underwent wedge liver resection (62%), 293 received anatomical resections (38%). Among anatomical resections, major hepatectomy (more than 3 segments) was performed in 165 cases (56.3%), while the resection was classified as minor (3 segments or less) in 128 (43.7%) cases. Among included patients, the BMI ranged from 19.5 to 40.4 (kg/m2).

The median LOS was 7 days (range 2–28 days). Navarro et al showed a series where there were no cases requiring conversion to open surgery. Robotic SCLR for colorectal cancer with liver metastases can be carried out safely, even when major liver resections are needed, particularly in specialized centers with experienced and well-trained teams (13). The mean operative times ranged from from 30 to 682 minutes. Longer operative time is considered to be a drawback of robotic procedures. This is due the time needed to prepare and dock the robot, as well as for changing instruments during the procedure.

Winckelmans et al. also explored the economic aspects—an especially relevant and widely discussed topic in the context of robotic surgery—by comparing robotic liver resections with laparoscopic ones. They found that expenses associated with surgical instruments and hospital stay were notably lower in the robotic group, whereas the costs linked to operative time were higher in that same group (24).

Data about POLF (postoperative liver failure) are reported in two studies: Rocca et al 1/90 patients, Marino et al. 1/40 patients. Biliary leak is reported in 1 case by Marino et al. while Winckelmans et al. reported a 2.6% of biliary leak in laparoscopic group and 3.4% in robotic group respectively.

Not all studies reported data about blood loss; considering 13 studies the median blood loss was 181,5 ml (30-780). Regarding Clavien Dindo classification the complications rate was 19.2% grade I, 0.9% grade II, 8.5% grade III, 0.4% grade IV, 0.2% grade V (27).

About the timing of robotic surgeries in 5 studies the approach was simultaneous with colorectal surgery and in 2 studies was in two steps; it was not specified in the remaining ones .

Long-Term Outcomes

Most papers don’t report long term outcomes. Navarro et al. (2) reports 12 cases followed for 47.1 months of disease-free survival (DFS) and 75.2 months of overall survival (OS).

Guadagni et al. (4) in 20 cases reports a 1- and 3-year disease-free survival of 89.5% and 35.8%, respectively.

Pesi et al instead reported that 4% of the patients (two) had died. Local recurrence was diagnosed in five patients (10%), whereas distant metastases were observed in five patients (10%)(22). Rocca et al. told us that short- and long-term outcomes are superimposable compared to laparoscopy to RLR (16).

| Patients |

N |

|

Age (years) |

BMI (kg/m2) |

Primary tumor location |

Liver disease |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Righ Left Rectum |

|

|

| Navarro et al 2019 (13) |

12 |

|

59(37–77) |

24.9±2.4 |

2 1 10 |

n/a |

|

| Achterberg et al. 2024 (12) |

201 |

|

65(57-72) |

n/a |

40 65 96 |

n/a |

|

| McGuirk et al. 2021 (14) |

28 |

|

62,5 |

22,4 |

7 7 14 |

n/a |

|

| Guadagni et al. 2020 (15) |

20 |

|

66.1 ± 11.8 |

24.4 ± 2.7 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

| Rocca et al. 2024 (16) |

45 |

|

66.53 ±12.67 |

25.95 ±3.83 |

11 15 19 |

n/a |

|

| Machado et al. 2019 (17) |

1 |

|

64 |

n/a |

1 |

n/a |

|

| Kenary et al. 2025 (18) |

1 |

|

78 |

n/a |

1 |

n/a |

|

| Krishnamurthy et al. 2018 (19) |

1 |

|

57 |

n/a |

1 |

n/a |

|

| Wang et al. 2023 (20) |

1 |

|

52 |

n/a |

1 |

n/a |

|

| Marino et al. 2020 (21) |

40 |

|

69.4 (38–79) |

25.2 (18.5–28.8) |

n/a |

Hepatitis B 5 (12.5%), Hepatitis C 4 (10%), Cirrhosis 6 (15%) |

|

| Pesi et al. 2019 (22) |

51 |

|

63 (31–81) |

n/a |

n/a |

Cirrhosis 13 (25,5%) |

|

| Mehdorn et al. 2021 (23) |

50 |

|

64.0 ± 12.3 (40–82) |

27.4 ± 6.7 (19.5–40.4) |

n/a |

n/a |

|

| Winckelmans et al. 2023 (24) |

210 |

|

age >75 years 92 20.4%, age<75 years 34 19.2% |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

| Rahimly et al. 2022 (25) |

50 |

|

66.9 (10.5) |

27.9 (5.0) |

n/a |

cirrhosis Child A 10 (25.0)

Child B 2 (5.0)

Hepatic steatosis 14 (35.0)

Hepatitis B 2 (5.0)

Hepatitis C 1 (2.5)

|

|

Discussion

The global incidence of CRC has been rising with annual increases of 3.2%, beginning with 783,000 cases in 1999 and increasing to 1.8 million in 2020 (5). Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common malignancy and the second most common cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most common causes of cancer-related mortality, with liver metastases occurring in roughly 25–30% of diagnosed individuals. Around 15% of patients were found to have liver metastases at the time of diagnosis, and nearly half of all individuals with colorectal cancer are expected to develop liver metastases at some point during their lives (6).Earlier studies indicate a variation in survival outcomes between patients with liver metastases originating from right-sided versus left-sided CRC, despite the fact that left-sided tumors tend to develop liver metastases more frequently (3).

The development of liver metastases from colorectal cancer is a prolonged and intricate process. It encompasses the persistence of the primary tumor, invasion into blood vessels, distant spread, and the eventual formation of metastases. The establishment of a supportive microenvironment prior to metastasis significantly facilitates tumor colonization and growth. During the progression of liver metastases in colorectal cancer, these events do not occur in a strict sequence but often happen simultaneously. The liver, which receives blood from the gastrointestinal tract, is the most common site for colorectal cancer to spread. It contains various resident cell types that contribute to the formation of a pre-metastatic niche. Some of these cells aid in tumor attachment and colonization, others support tumor cell growth, modulate the immune environment, or promote the formation of new blood vessels (7). Interventional oncology plays a key role in managing liver metastases from colorectal cancer by expanding the pool of patients eligible for surgery, offering potentially curative options to those who cannot undergo surgery, and enhancing survival outcomes in palliative care scenarios. While surgical removal remains the preferred approach when feasible, image-guided ablation—either alone or combined with surgery—has shown better survival outcomes compared to chemotherapy by itself. Selecting appropriate candidates—particularly those with tumors smaller than 3 cm—and ensuring ablation margins exceed 5 mm can help reduce local tumor recurrence. Techniques like cryoablation may be effective in alleviating symptoms caused by painful lesions, while irreversible electroporation (IRE) offers a non-thermal option for tumors located near sensitive structures, such as bile ducts, where heat-based treatments are less suitable due to the heat sink effect. As treatment strategies continue to shift, more research is needed, particularly given the rising incidence of colorectal cancer in younger individuals (8). When examining surgical options, robotic techniques have seen significant advancements. Laparoscopic surgery is now widely regarded as the standard approach for specific procedures, such as left-lateral sectionectomies and wedge resections of anterior liver segments. However, the exact role of robotic liver surgery remains under discussion, particularly in terms of long-term cancer-related outcomes. Robotic technology represents the most advanced form of minimally invasive surgery, though there are still some unresolved challenges regarding its implementation in clinical practice. Robot-assisted, minimally invasive surgery has already become a reality and is likely to be the future standard for many procedures. Conventional laparoscopy has several limitations, such as restricted movement, difficulty performing precise sutures, awkward surgeon positioning, and a lack of 3D visualization. Robotic surgery addresses many of these challenges and broadens the potential for minimally invasive surgery to benefit more patients (28). Robotic surgery presents as a compelling minimally invasive alternative for liver procedures due to enhanced visualization and the use of highly articulated instruments (9). Challenges such as longer operative times and the absence of tactile sensation have been noted, although these drawbacks have not been clearly demonstrated in clinical studies. On the other hand, according to Machado et al., robotic repeat hepatectomy is a viable and safe option when performed by skilled surgeons and may offer certain benefits compared to laparoscopic or open repeat liver resections (17). Unique aspects of robotic procedures, including specific safety measures, must be established and reviewed at the start of each operation to prepare for possible emergency conversions. Although many liver surgeons have been slow to adopt this technique, robotic liver surgery continues to develop and gain acceptance in the field. Current data indicate that cancer outcomes following robotic liver resections are comparable to those seen with open or laparoscopic techniques for both hepatocellular carcinoma and colorectal liver metastases, with additional benefits noted in cirrhotic patients and those requiring repeat operations (10). Achieving optimal outcomes and maintaining high levels of patient safety requires targeted training in both hepatobiliary and general minimally invasive surgical skills to successfully navigate the learning curve. As we can infer from our review experience, the age of patients varies greatly, reaching up to 88 years, demonstrating a relatively wide application of robotic surgery. The site most commonly associated with metastatic issues is the rectum, and the robot performs particularly well in minor hepatic resections. However, there is limited long-term data, although the encouraging results motivate us to increasingly use this surgical approach in the future. Many of the studies reviewed evaluated the feasibility of robotic-assisted surgery for the treatment of colorectal liver metastases (CRLM), highlighting its beneficial role even in patients with multiple metastases or those who had undergone previous or simultaneous surgeries. Emerging imaging technologies (11) such as near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence with indocyanine green (ICG) may help offset the absence of tactile sensation in minimally invasive surgery and act as a valuable complement to intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS). Many laparoscopic and robotic platforms currently in clinical use are either compatible with or already integrated with NIR fluorescence imaging capabilities. The use of ICG fluorescence can offer surgeons real-time visualization of tumor boundaries during minimally invasive procedures for colorectal liver metastases, potentially enhancing the rate of complete oncologic resections. Achterberg et al have shown that ICG-guided imaging is linked to a higher frequency of margin-negative resections and led to intraoperative strategy modifications in over 25% of cases. Notably, the lack of ICG signal in the liver during parenchymal dissection was found to predict an R0 resection with 92% precision (12). These findings indicate that ICG fluorescence can support intraoperative decision-making and improve oncologic outcomes by providing accurate, real-time delineation of tumor margins.A limitation of our work is certainly the number of reviewed papers; however, few papers focused on the strictly surgical and robotic aspects.Future prospects are definitely the continued advancements that are anticipated in both resection techniques and diagnostic tools. Technologies such as artificial intelligence—which is already being implemented in laparoscopy — augmented reality, intraoperative navigation, and hybrid operating rooms are expected to play an increasingly important role. These innovations support surgeons in managing complex anatomies that are not visible on the surface and often exhibit significant individual variation.

Conclusions

As research progresses and new weapons are available for the treatment of CRLM , surgery maintains its predominant role. Robotic liver surgery is now a consolidated reality. Its application in the treatment of liver metastases from colorectal cancer is the future. This minimally invasive approach proposes treatment of the pathology either concurrently or subsequently to the primary surgery with encouraging outcomes. Robotic combined resection for colorectal cancer with liver metastases is technically achievable and appears to offer comparable oncologic outcomes to those of open or laparoscopic procedures . Further studies are necessary in the future to reinforce our conclusions considering the relatively small number of involved papers.

References

- Becker F, Morgül H, Katou S, Juratli M, Hölzen JP, Pascher A, et al. Robotic Liver Surgery - Current Standards and Future Perspectives. Z Gastroenterol. 2021;59(1):56-62.

- Palucci M, Giannone F, Del Angel-Millán G, Alagia M, Del Basso C, Lodin M, et al. Robotic liver parenchymal transection techniques: a comprehensive overview and classification. J Robot Surg. 2024;19(1):36.

- Engstrand J, Nilsson H, Strömberg C, Jonas E, Freedman J. Colorectal cancer liver metastases - a population-based study on incidence, management and survival. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):78.

- Horn SR, Stoltzfus KC, Lehrer EJ, Dawson LA, Tchelebi L, Gusani NJ, et al. Epidemiology of liver metastases. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020;67:101760.

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-49.

- Biasco G, Derenzini E, Grazi G, Ercolani G, Ravaioli M, Pantaleo MA, et al. Treatment of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: many doubts, some certainties. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32(3):214-28.

- Zhao W, Dai S, Yue L, Xu F, Gu J, Dai X, et al. Emerging mechanisms progress of colorectal cancer liver metastasis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1081585.

- Venkat SR, Mohan PP, Gandhi RT. Colorectal Liver Metastasis: Overview of Treatment Paradigm Highlighting the Role of Ablation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;210(4):883-90.

- Lafaro KJ, Stewart C, Fong A, Fong Y. Robotic Liver Resection. Surg Clin North Am. 2020;100(2):265-81.

- Di Benedetto F, Petrowsky H, Magistri P, Halazun KJ. Robotic liver resection: Hurdles and beyond. Int J Surg. 2020;82s:155-62.

- Kasai M, Uchiyama H, Aihara T, Ikuta S, Yamanaka N. Laparoscopic Projection Mapping of the Liver Portal Segment, Based on Augmented Reality Combined With Artificial Intelligence, for Laparoscopic Anatomical Liver Resection. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e48450.

- Achterberg FB, Bijlstra OD, Slooter MD, Sibinga Mulder BG, Boonstra MC, Bouwense SA, Bosscha K, Coolsen MME, Derksen WJM, Gerhards MF, Gobardhan PD, Hagendoorn J, Lips D, Marsman HA, Zonderhuis BM, Wullaert L, Putter H, Burggraaf J, Mieog JSD, Vahrmeijer AL, Swijnenburg RJ; Dutch Liver Surgery Group. ICG-Fluorescence Imaging for Margin Assessment During Minimally Invasive Colorectal Liver Metastasis Resection. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Apr 1;7(4).

- Navarro J, Rho SY, Kang I, Choi GH, Min BS. Robotic simultaneous resection for colorectal liver metastasis: feasibility for all types of liver resection. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2019 Nov;404(7):895-908.

- McGuirk M, Gachabayov M, Rojas A, Kajmolli A, Gogna S, Gu KW, Qiuye Q, Dong XD. Simultaneous Robot Assisted Colon and Liver Resection for Metastatic Colon Cancer. JSLS. 2021 Apr-Jun;25(2):e2020.00108.

- Guadagni S, Furbetta N, Franco GD, Palmeri M, Gianardi D, Bianchini M, Guadagnucci M, Pollina L, Masi G, Cremolini C, Falcone A, Mosca F, Di Candio G, Morelli L. Robotic-assisted surgery for colorectal liver metastasis: A single-centre experience. J Minim Access Surg. 2020 Apr-Jun;16(2):160-165.

- Rocca A, Avella P, Scacchi A, Brunese MC, Cappuccio M, De Rosa M, Bartoli A, Guerra G, Calise F, Ceccarelli G. Robotic versus open resection for colorectal liver metastases in a “referral centre Hub&Spoke learning program”. A multicenter propensity score matching analysis of perioperative outcomes. Heliyon. 2024 Jan.

- Machado MA, Surjan RC, Basseres T, Makdissi F. Robotic Repeat Right Hepatectomy for Recurrent Colorectal Liver Metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019 Jan;26(1):292-295. Epub 2018 Nov 9. [CrossRef]

- Kenary PY, Ross S, Sucandy I. Robotic Subtotal Caudate Lobe Hepatic Resection for Paracaval Colorectal Metastasis: Technique of Inferior Vena Cava Dissection and Handling. Ann Surg Oncol. 2025 Mar;32(3):1769-1770.

- Krishnamurthy J, Naragund AV, Mahadevappa B. First Ever Robotic Stage One ALPPS Procedure in India: for Colorectal Liver Metastases. Indian J Surg. 2018 Jun;80(3):269-271. [CrossRef]

- Robotic combined resection of sigmoid colon, hepatic metastasis (S3), and pelvic metastasis - A video vignette Anqi Wang 1, Ce Bian 1, Peng Zhang 1, Haiyang Zhou 1 Colorectal Dis. 2023 Oct;25(10):2121-2122.

- The application of indocyanine green-fluorescence imaging during robotic-assisted liver resection for malignant tumors: a single-arm feasibility cohort study Marco Vito Marino,* , Mauro Podda , Carmen C. Fernandez , Marcos G. Ruiz & Manuel G. Fleitas HPB (Oxford). 2020 Mar;22(3):422-431.

- Surgical and oncological outcomes after ultrasound-guidedrobotic liver resections for malignant tumor. Analysis of a prospective database Benedetta Pesi | Luca Moraldi | Francesco Guerra | Federica Tofani |Alessandro Nerini | Mario Annecchiarico | Andrea Coratti Int J Med Robot. 2019 Aug;15(4):e2002.

- Usability of Indocyanine Green in Robot-Assisted Hepatic Surgery.Anne-Sophie Mehdorn 1, Jan Henrik Beckmann 1, Felix Braun 1, Thomas Becker 1, Jan-Hendrik Egberts 1 J Clin Med. 2021 Jan 25;10(3):456.

- Robotic Versus Laparoscopic Hepatectomy: A Single Surgeon Experience of 629 Consecutive Minimally Invasive Liver Resections. Thomas Winckelmans 1, Dennis A Wicherts 2, Isabelle Parmentier 1 3, Celine De Meyere 1, Chris Verslype 1 2 4, Mathieu D’Hondt World J Surg. 2023 Sep;47(9):2241-2249.

- The LiMAx Test as Selection Criteria in Minimally Invasive Liver Surgery Mirhasan Rahimli 1,*, Aristotelis Perrakis 1 , Andrew A. Gumbs 2 , Mihailo Andric 1 , Sara Al-Madhi 1 , Joerg Arend 1 and Roland S. Croner J Clin Med. 2022 May 27;11(11):3018.

- PRISMA 2020: a reporting guideline for the next generation of systematic reviews. Brennan SE, Munn Z. JBI Evid Synth. 19. United States2021. p. 906-8.

- Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA Ann Surg. 2004 Aug;240(2):205-13. PMID: 15273542; PMCID: PMC1360123. [CrossRef]

- Robotics in general surgery: personal experience in a large community hospital.Giulianotti PC, Coratti A, Angelini M, Sbrana F, Cecconi S, Balestracci T, Caravaglios G. Arch Surg. 2003 Jul;138(7):777-84. PMID: 12860761. [CrossRef]

- Robotic versus open hepatectomy for large(≥ 5 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma: A large volume center, propensity score matched study. Mao W, Meng B, Jin Z, et al. World J Surg Oncol. 2025;23(1):306. Published 2025 Jul 31. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).