Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This review presents a comprehensive overview of dental materials that support tissue healing while exhibiting antimicrobial properties. Emphasis is placed on materials that are biocompatible, bioactive, and non-toxic to host cells, with demonstrated bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity. The review summarizes current research on natural bactericides, antimicrobial polymers, and bioactive glass/polymer composites, along with various techniques employed for surface coating of dental implants. Three principal categories of antimicrobial coatings have been identified: antibacterial phytochemicals, synthetic antimicrobial agents (including polymers and antibiotics), and metallic nanoparticles. Among these, antibacterial peptide-based coatings have been the most extensively studied and have shown the greatest effectiveness in reducing bacterial colonization, especially during extended incubation periods. These coatings offer high antimicrobial potency, durability, and excellent biocompatibility, positioning them as promising candidates for long-term protection against microbial contamination. However, additional in vitro and pre-clinical studies are warranted to thoroughly evaluate their therapeutic potential and to establish their efficacy and safety for clinical applications in the prevention of peri-implant infections.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

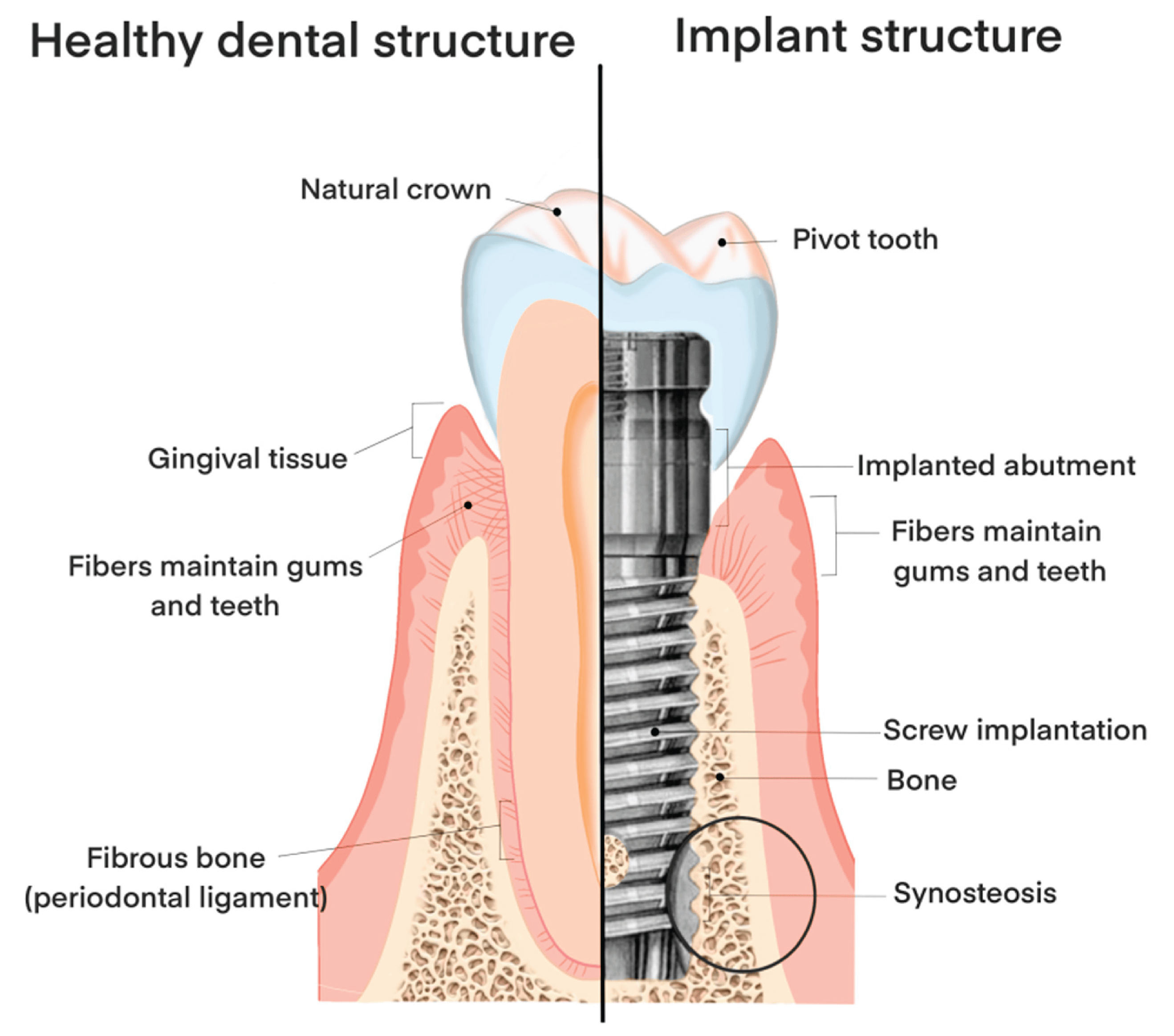

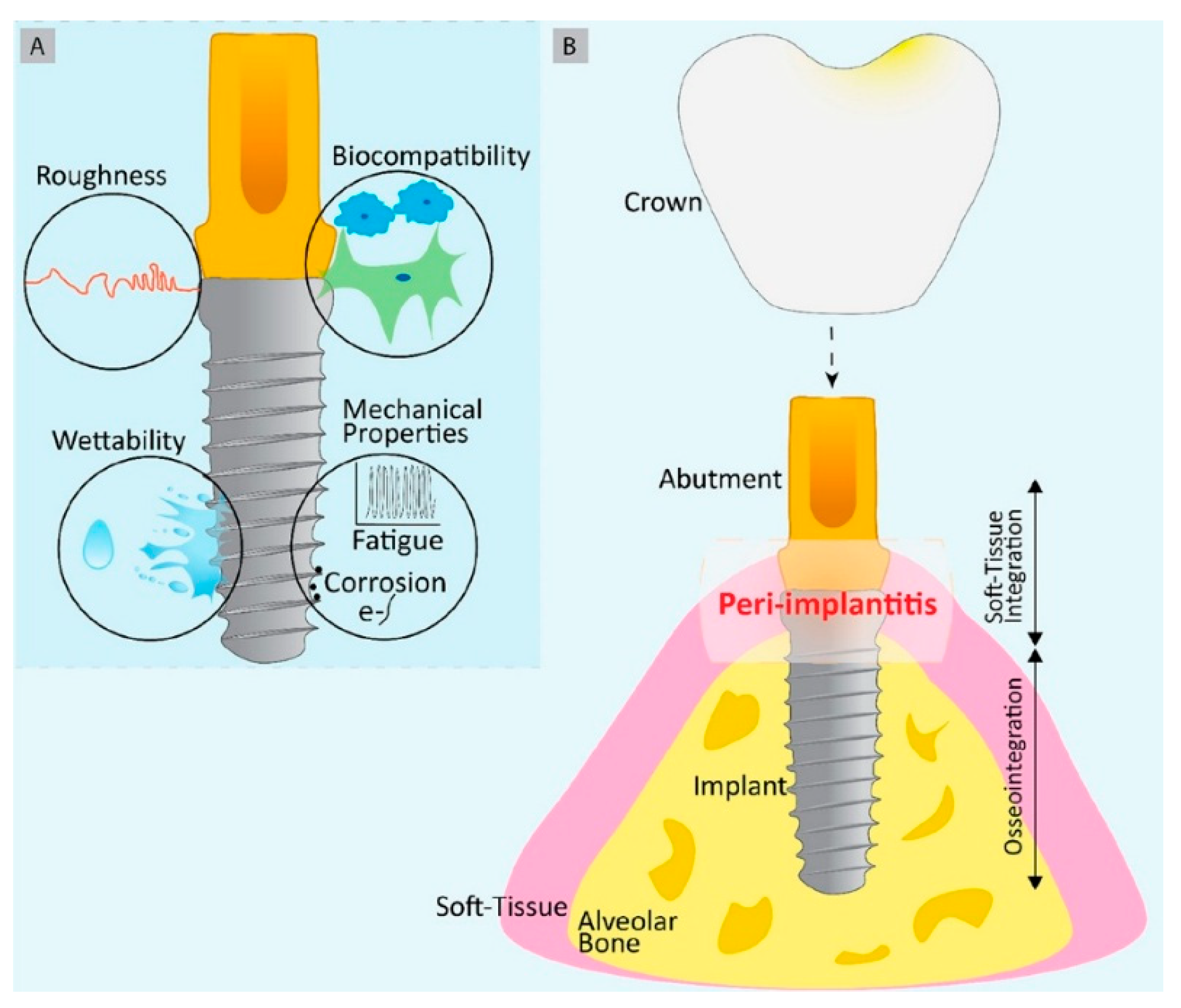

2. Challenges Associated with Dental Implants

2.1. Post Operative Infection:

2.2. Implant Rejection

2.3. Allergic Reactions:

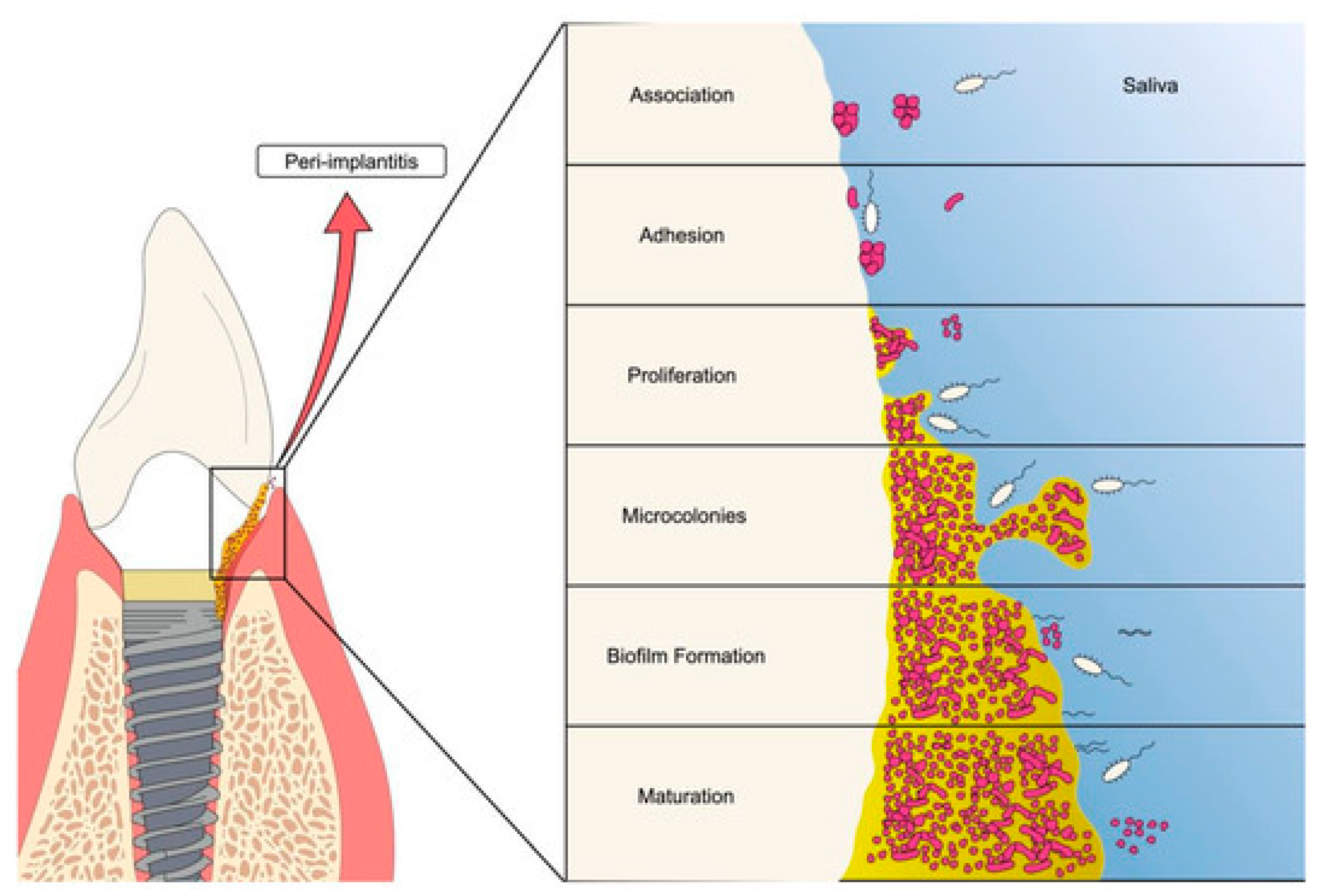

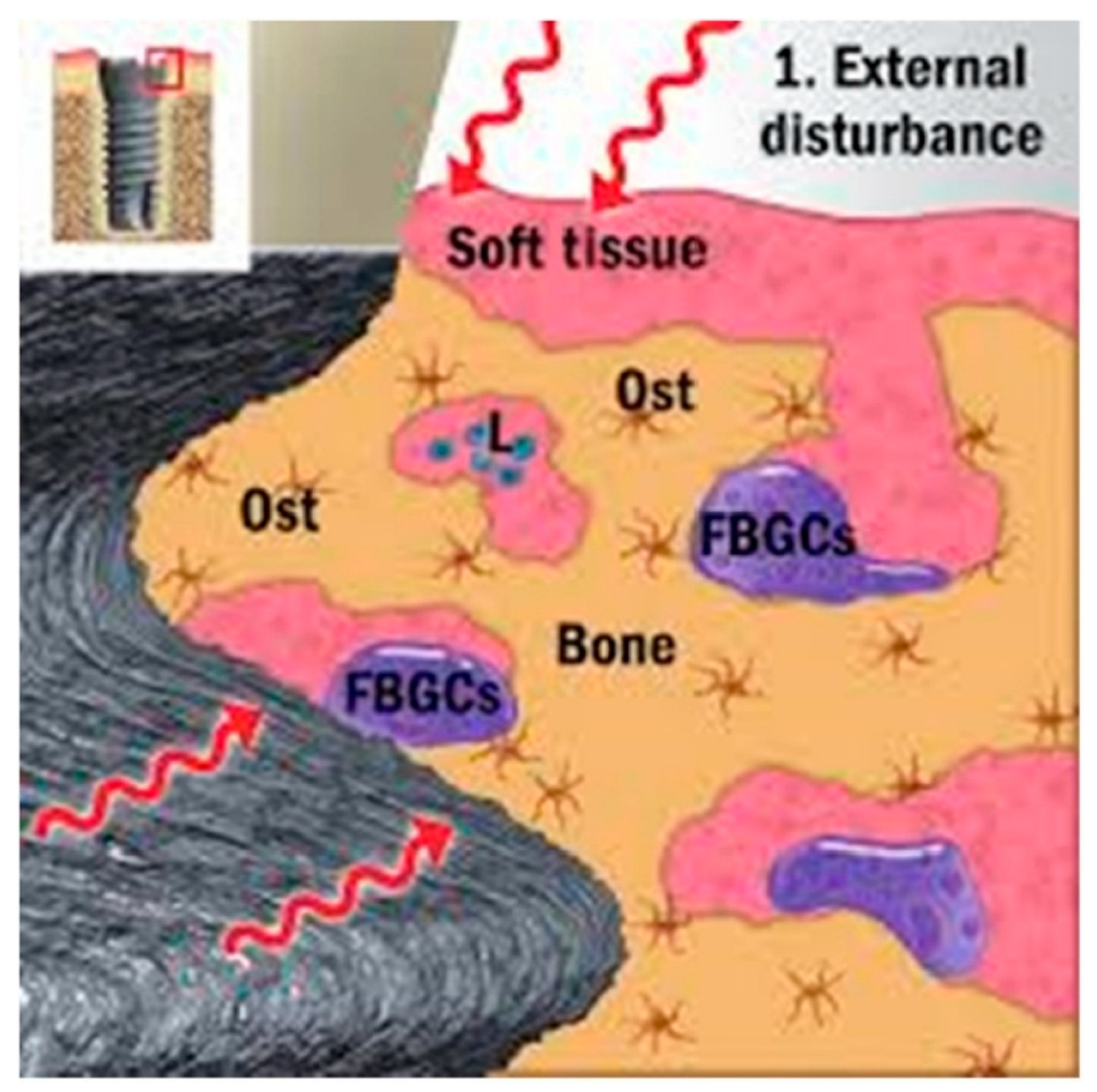

2.4. Peri-Implantitis

2.5. Implant Failure

2.6. Bone Loss or Resorption:

2.7. Aesthetic Issue

3. Implant Related Dental Infections

3.1. Microbiota of Oral Cavity and Dental Implants

3.2. Biofilms on Implants

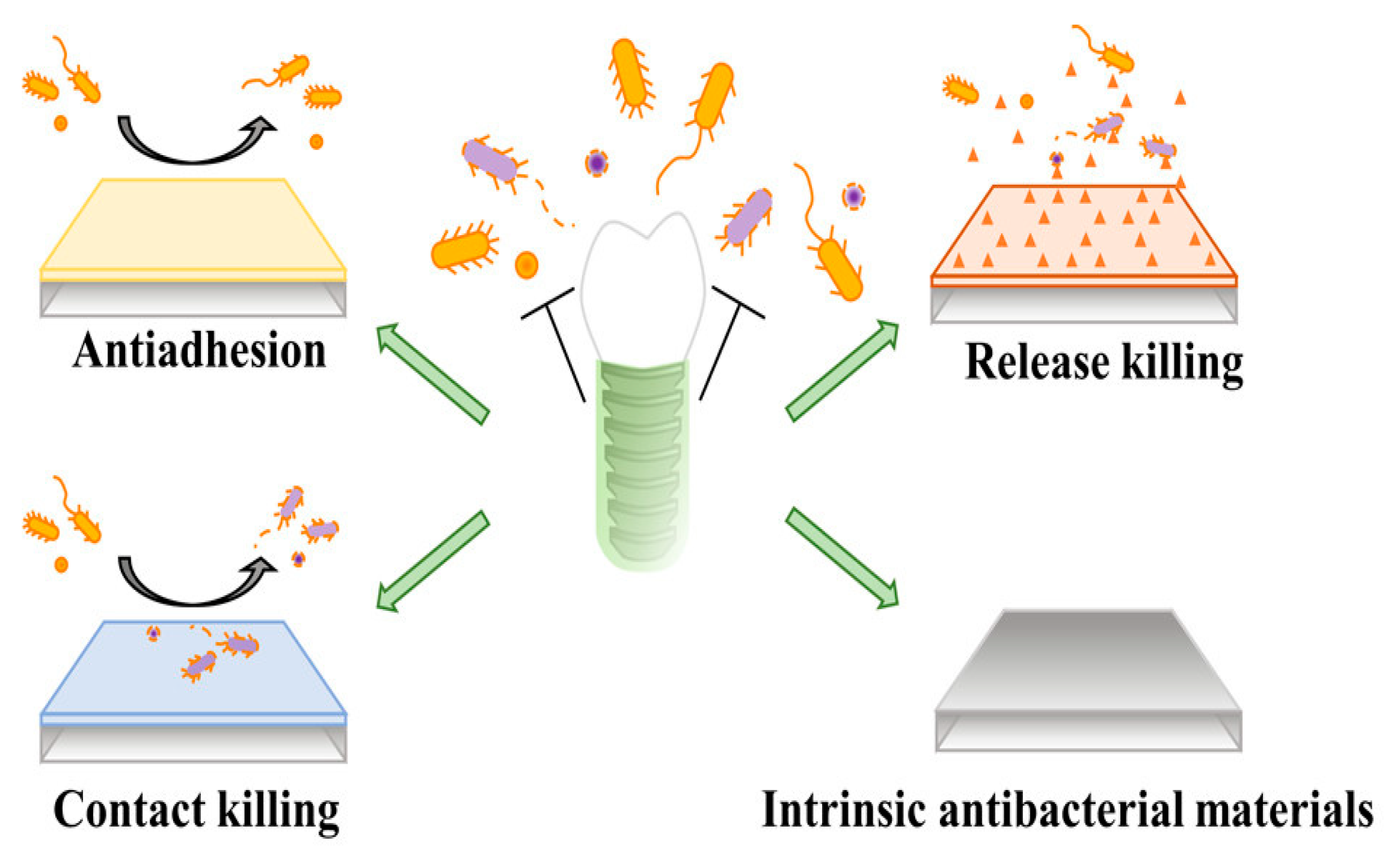

4. Dental Antimicrobial Approaches

4.1. AMPs

4.2. Metal-Releasing Coatings:

4.3. Phytochemicals Used in Dental Materials (Phytodentistry)

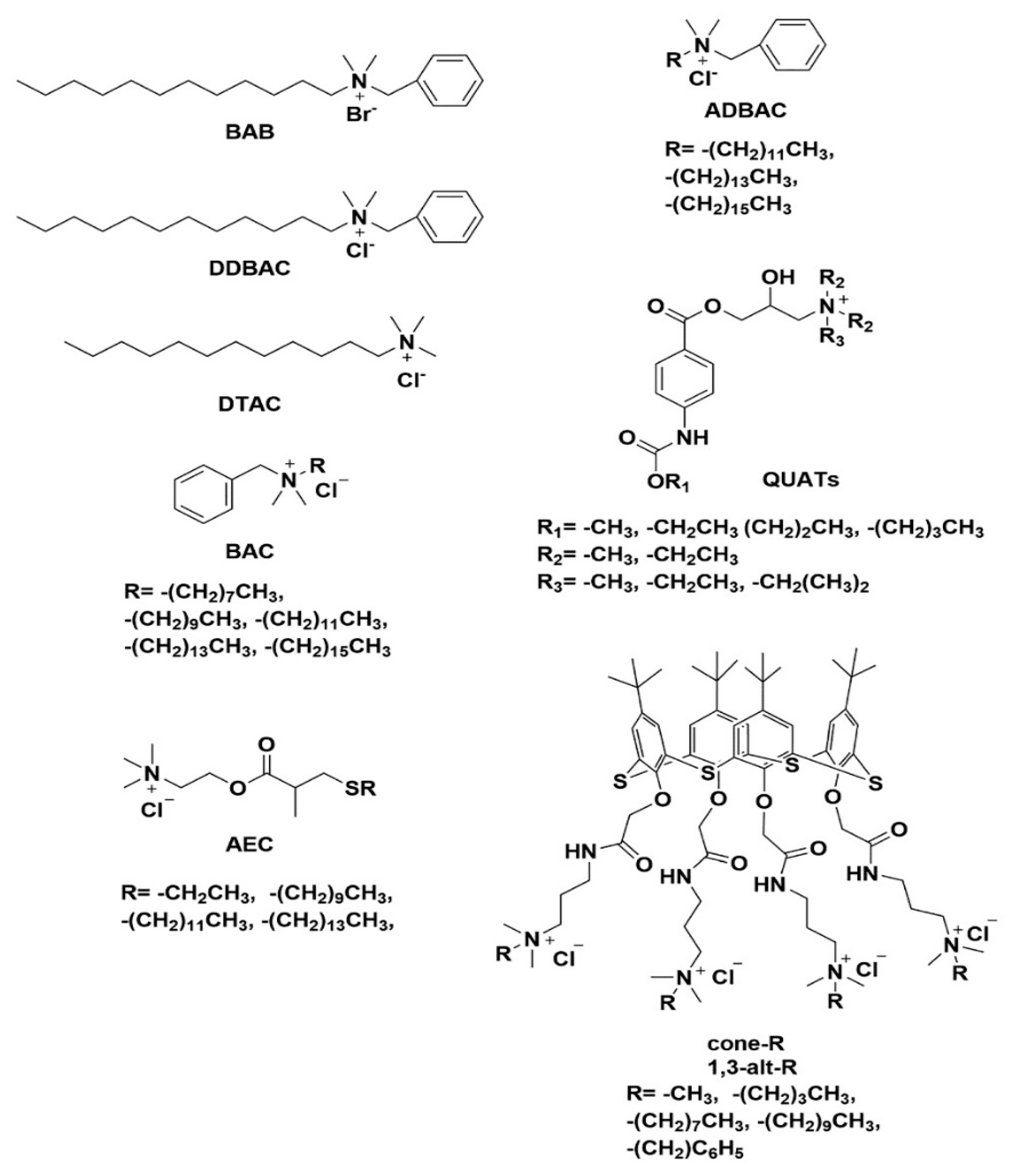

4.4. Quaternary Ammonium Compounds:

- The additive contains the following compounds: n- dodecyl dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride (CAS Reg. No. 139-07-1); n- dodecyl dimethyl ethylbenzyl ammonium chloride (CAS Reg. No. 27479-28-3); n- hexadecyl dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride (CAS Reg. No. 122-18-9); n- octadecyl dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride (CAS Reg. No. 122-19-0); n- tetradecyl dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride (CAS Reg. No. 139-08-2); n- tetradecyl dimethyl ethylbenzyl ammonium chloride (CAS Reg. No. 27479-29-4).

- The composition meets the following specifications: pH (5 percent active solution) 7.0-8.0; total amines, maximum 1 percent as combined free amines and amine hydrochlorides.

- The compound is used as an antimicrobial agent, as defined [[89]] orally in food.

| Name of QAS | Target Bacterial Strain | Human Cell Toxicity | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkyl Dimethyl benzyl Ammonium Chloride (ADBAC) | S. aureus; MIC: 0.6 μg mL–1 | In chronic trials with beagles, mice, and rats, repeated dosage oral toxicity studies found no harmful effects at 10–93.1 mg/kg-day for DDAC and 3.7–188 mg/kg-day for ADBAC (C > 12). At modest adverse impact levels, DDAC and ADBAC (C > 12) consistently cause decreased food intake, average body weight, body weight growth, and localized discomfort. |

[91,92] | |

| Dodecyl dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride (DDBAC) | Listeria monocytogenes; E. coli; S. aureus | Cell viability (NIH-3T3 assays) was 39.7% within 24 hrs incubation at dose of 500 μg/mL respectively | [93] | |

| P-tert-butylthiacalix [4]arene (1,3-alt-R) | S. aureus, B. subtills, E.coli, P. aeruginosa | Cytotoxicity studies on human skin fibroblast (HSF) cells demonstrated that were less toxic compared to ref. drugs. | [94] | |

| Ammonium-esterified acrylate (AEC) |

S. aureus; MIC: 3 ppm, E.coli ; MIC: 31 ppm, P. aeruginosa; MIC: 250 ppm, Candida albicans, Aspergillus niger; Klebsiella pneumoniae; Acinetobacter baummanii |

_ | [95] | |

| Didecyl dimethylammonium chloride (DDAC) |

S. aureus; MIC: 1.63 uM, E.coli ; MIC: 15. 63 uM, P. aeruginosa; MIC : 500uM; K. pneumoniae; MIC: 11 uM, Enterococcus sp.;MIC: 3 uM. |

Cell viability assays confirm a trend of a higher cytotoxicity in correlation to an increasing carbon chain length of the compounds. The toxic potential and low selectivity for microbes over mammalian cells, these novel compounds will likely be more useful as surface disinfectants rather than antiseptics. |

[96] | |

| N,N-dialkyl-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)-N-methylammonium salts (NDMAC) |

S. aureus; MIC: 0.9 uM, E.coli ; MIC: 7.8 uM, P. aeruginosa; MIC : 500uM |

|||

| N-[N′(3-gluconamide)propyl-N′-alkyl]propyl-N,N-dimethyl-N-alkyl ammonium bromide (CDDGPB) |

S. aureus; MIC: 150ppm, E.coli ; MIC: 150 ppm, |

The mortality of mice test group was the highest, with an LD50 of mice larger than 100 mg/kg, indicating that the surfactant has medium toxicity. The mortality of mice in the C10DDGPB test group was significantly lower than that in the C12DDGPB test group. No obvious blackening or body stiffness was observed in any of the tested animals during the 14-day observation period. |

[97] | |

5. Bioactive Dental Materials

5.1. Properties of Biomaterials

5.2. Metallic Substrates

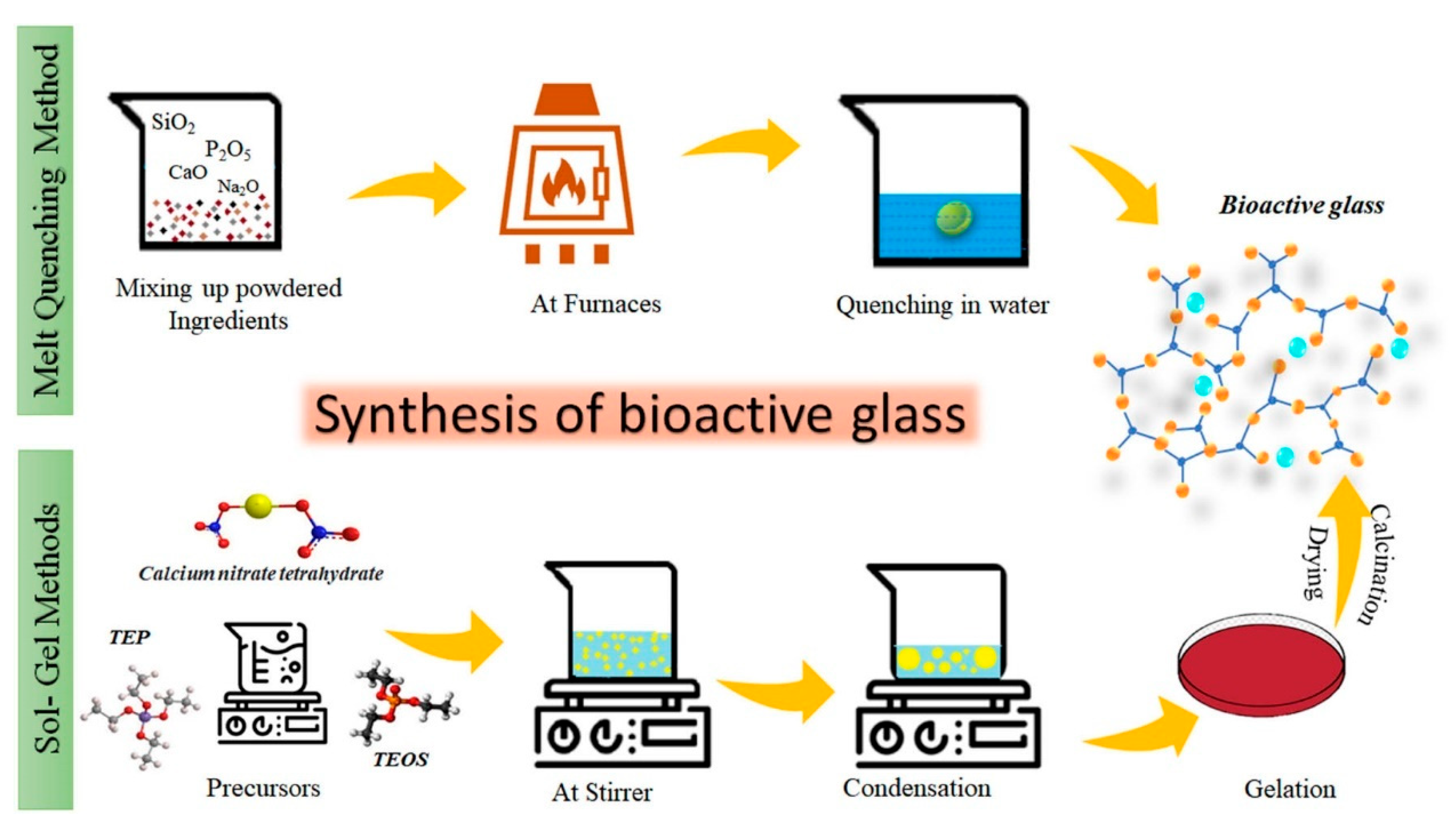

5.3. Bioactive Glass:

5.4. Implant Coatings Made from Bioactive Glass:

5.5. Coating Synthesis

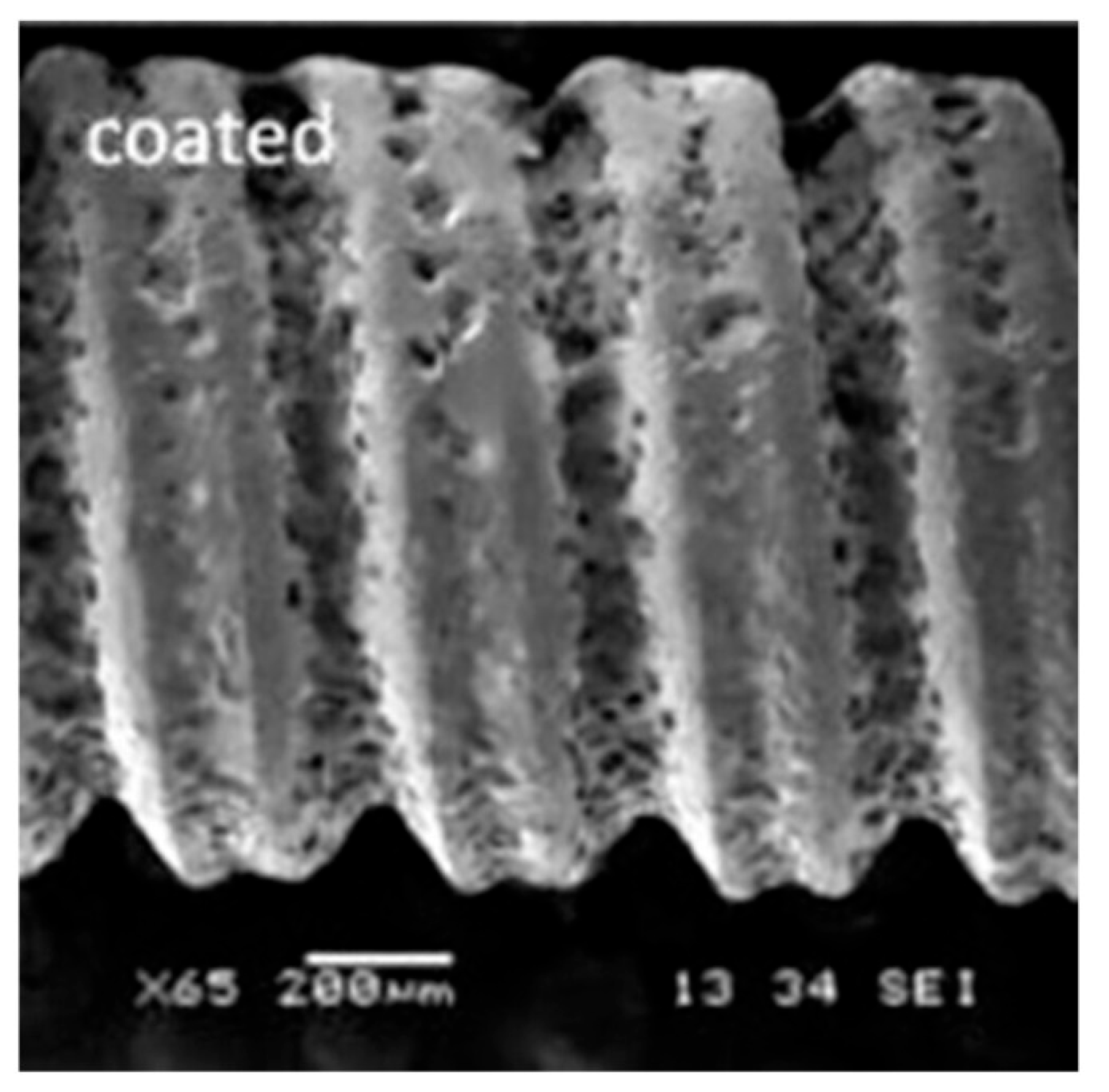

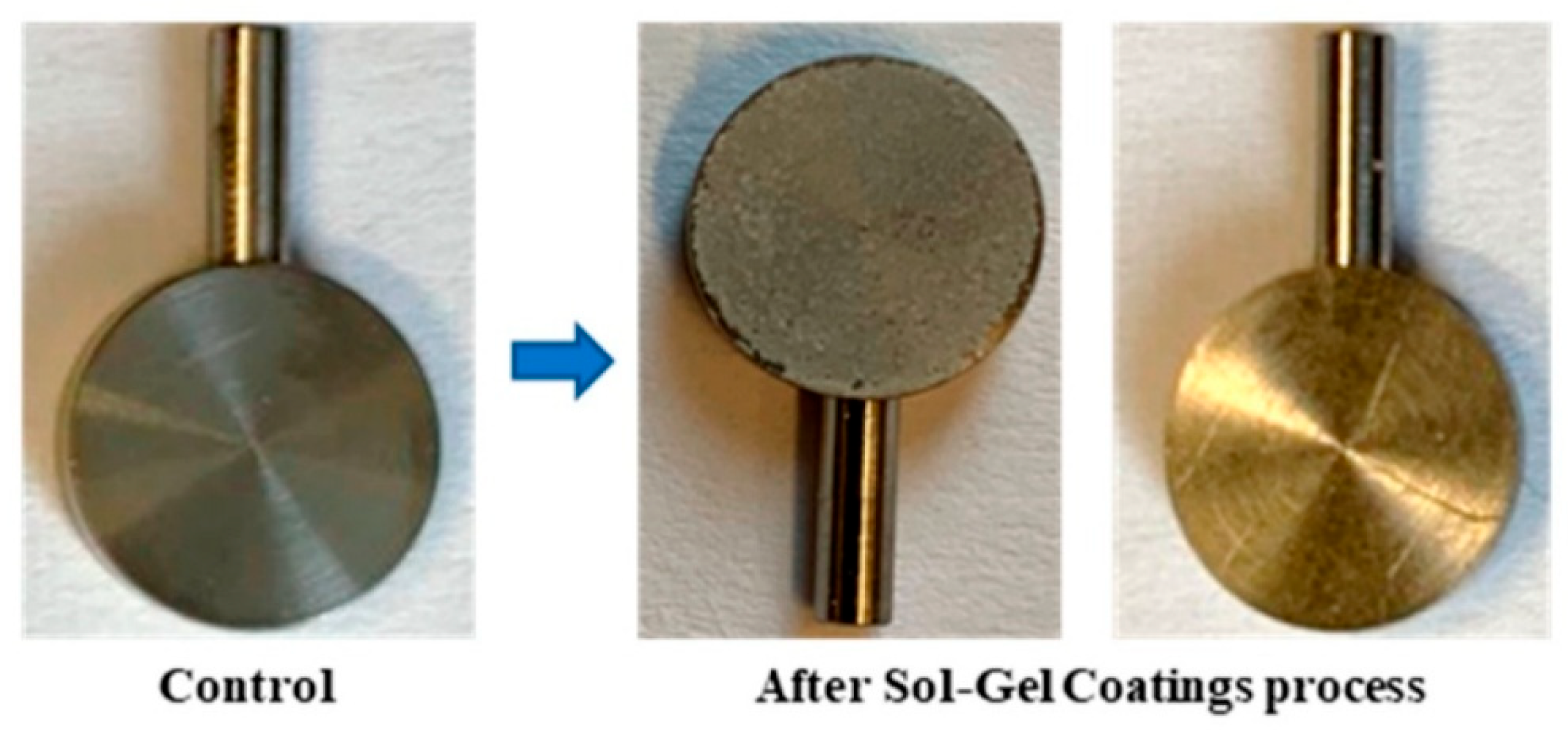

5.6. Sol- Gel Coating Process

Preparation of the Sol:

Gelation

Aging and Drying

Thermal Treatment (If Required)

Advantages of the Sol-Gel Process[160]

- Precise Control: Allows fine-tuning of material composition and properties.

- Simple/ Efficient: Suitable for applications where high temperatures may degrade components. Very high production efficiency. Low initial investment while having high quality products.Versatility: Can produce various material forms (thin films, coatings, fibers, powders).

- Purity and Homogeneity: Ensures uniform chemical distribution.

5.7. Combination of the Sol–Gel Method with Coating Techniques

5.8. Sol- Gel Based Antimicrobial Materials

6. Gaps and Future Directions

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- “Oral and maxillofacial surgeons: the experts in face, mouth and jaw surgery ,” American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons.

- A. Gupta, M. Dhanraj, and G. Sivagami, “Status of surface treatment in endosseous implant: A literary overview,” Indian Journal of Dental Research, vol. 21, no. 3, p. 433, 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. Gaviria, J. P. Salcido, T. Guda, and J. L. Ong, “Current trends in dental implants,” J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg, vol. 40, no. 2, p. 50, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Lambris and R. Paoletti, “Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology.” Online.. Available: http://www.springer.com/series/5584.

- S. S. Magill et al., “Multistate Point-Prevalence Survey of Health Care–Associated Infections,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 370, no. 13, pp. 1198–1208, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Montanaro et al., “Scenery of Staphylococcus Implant Infections in Orthopedics,” Future Microbiol, vol. 6, no. 11, pp. 1329–1349, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- B. Li and T. J. Webster, “Bacteria antibiotic resistance: New challenges and opportunities for implant-associated orthopedic infections,” Journal of Orthopaedic Research, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 22–32, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Gao et al., “Research Progress on the Preparation Process and Material Structure of 3D-Printed Dental Implants and Their Clinical Applications,” Coatings, vol. 14, no. 7, p. 781, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- “Pan-Canadian Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance,” Jun. 2023.

- D. Zoutman, S. McDonald, and D. Vethanayagan, “Total and Attributable Costs of Surgical-Wound Infections at a Canadian Tertiary-Care Center,” Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 254–259, Apr. 1998. [CrossRef]

- O. Camps-Font, P. Martín-Fatás, A. Clé-Ovejero, R. Figueiredo, C. Gay-Escoda, and E. Valmaseda-Castellón, “Postoperative infections after dental implant placement: Variables associated with increased risk of failure,” J Periodontol, vol. 89, no. 10, pp. 1165–1173, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Anth. G. Gristina, “Biomaterial-Centered Infection: Microbial Adhesion Versus Tissue Integration,” American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 1981. Online.. Available: www.sciencemag.org.

- J. M. Schierholz and J. Beuth, “Implant infections: a haven for opportunistic bacteria,” Journal of Hospital Infection, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 87–93, Oct. 2001. [CrossRef]

- S. Ivanovski, P. M. Bartold, and Y. Huang, “The role of foreign body response in <scp>peri-implantitis</scp> : What is the evidence?,” Periodontol 2000, vol. 90, no. 1, pp. 176–185, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Trindade, T. Albrektsson, P. Tengvall, and A. Wennerberg, “Foreign Body Reaction to Biomaterials: On Mechanisms for Buildup and Breakdown of Osseointegration,” Clin Implant Dent Relat Res, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 192–203, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. Thomas and B. Summer, “Implant allergy,” Allergol Select, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 59–64, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- “Allergies to dental materials,” Vital, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 39–39, Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- F. Schwarz, J. Derks, A. Monje, and H. L. Wang, “Peri-implantitis,” Jun. 01, 2018, NLM (Medline). [CrossRef]

- J. Prathapachandran and N. Suresh, “Management of peri-implantitis,” 2012. Online.. Available: www.drj.ir.

- J. Hasan et al., “Preventing Peri-implantitis: The Quest for a Next Generation of Titanium Dental Implants,” Nov. 14, 2022, American Chemical Society. [CrossRef]

- Y.-S. Park, B.-A. Lee, S.-H. Choi, and Y.-T. Kim, “Evaluation of failed implants and reimplantation at sites of previous dental implant failure: survival rates and risk factors,” J Periodontal Implant Sci, vol. 52, no. 3, p. 230, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, A. Pajares, and B. R. Lawn, “Fatigue and damage tolerance of Y-TZP ceramics in layered biomechanical systems,” J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater, vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 166–171, Oct. 2004. [CrossRef]

- “Failure mechanisms of medical implants and their effects on outcomes”.

- F. E. Lambert, H. Weber, S. M. Susarla, U. C. Belser, and G. O. Gallucci, “Descriptive Analysis of Implant and Prosthodontic Survival Rates With Fixed Implant–Supported Rehabilitations in the Edentulous Maxilla,” J Periodontol, vol. 80, no. 8, pp. 1220–1230, Aug. 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. Shetty, P. Yadav, M. Tahir, and V. Saini, “Implant Design and Stress Distribution,” International Journal of Oral Implantology & Clinical Research, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 34–39, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Liaw, R. H. Delfini, and J. J. Abrahams, “Dental Implant Complications,” Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI, vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 427–433, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Renvert, G. R. Persson, F. Q. Pirih, and P. M. Camargo, “Peri-implant health, peri-implant mucositis, and peri-implantitis: Case definitions and diagnostic considerations,” J Clin Periodontol, vol. 45, no. S20, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Atieh, N. H. M. Alsabeeha, C. M. Faggion, and W. J. Duncan, “The Frequency of Peri-Implant Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” J Periodontol, vol. 84, no. 11, pp. 1586–1598, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Radaic and Y. L. Kapila, “The oralome and its dysbiosis: New insights into oral microbiome-host interactions,” Comput Struct Biotechnol J, vol. 19, pp. 1335–1360, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Lu, S. Xuan, and Z. Wang, “Oral microbiota: A new view of body health,” Food Science and Human Wellness, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 8–15, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Bolukbasi, T. Ozdemir, L. Oksuz, and N. Gurler, “Bacteremia following dental implant surgery: Preliminary results,” Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal, pp. e69–e75, 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Pye, D. E. A. Lockhart, M. P. Dawson, C. A. Murray, and A. J. Smith, “A review of dental implants and infection,” Journal of Hospital Infection, vol. 72, no. 2, pp. 104–110, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- G. Cheng, Z. Zhang, S. Chen, J. D. Bryers, and S. Jiang, “Inhibition of bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation on zwitterionic surfaces,” Biomaterials, vol. 28, no. 29, pp. 4192–4199, Oct. 2007. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Pang, P. Hong, H. Guo, and W.-T. Liu, “Biofilm Formation Characteristics of Bacterial Isolates Retrieved from a Reverse Osmosis Membrane,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 39, no. 19, pp. 7541–7550, Oct. 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. Goldberg, “Biofilms and antibiotic resistance: a genetic linkage,” Trends Microbiol, vol. 10, no. 6, p. 264, Jun. 2002. [CrossRef]

- J.-S. Peng, W.-C. Tsai, and C.-C. Chou, “Inactivation and removal of Bacillus cereus by sanitizer and detergent,” Int J Food Microbiol, vol. 77, no. 1–2, pp. 11–18, Jul. 2002. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Chen, Z. Zhang, and T. R. Bott, “Direct measurement of the adhesive strength of biofilms in pipes by micromanipulation ,” Biotechnology Techniques, vol. 12, no. 12, pp. 875–880, 1998. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Dickinson and A. L. Bisno, “Infections associated with indwelling devices: infections related to extravascular devices,” Antimicrob Agents Chemother, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 602–607, May 1989. [CrossRef]

- E. Muller, J. Hübner, N. Gutierrez, S. Takeda, D. A. Goldmann, and G. B. Pier, “Isolation and characterization of transposon mutants of Staphylococcus epidermidis deficient in capsular polysaccharide/adhesin and slime,” Infect Immun, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 551–558, Feb. 1993. [CrossRef]

- D. Mack et al., “The intercellular adhesin involved in biofilm accumulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis is a linear beta-1,6-linked glucosaminoglycan: purification and structural analysis,” J Bacteriol, vol. 178, no. 1, pp. 175–183, Jan. 1996. [CrossRef]

- I. Sutherland, “The biofilm matrix – an immobilized but dynamic microbial environment,” Trends Microbiol, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 222–227, May 2001. [CrossRef]

- W. M. Dunne, “Bacterial Adhesion: Seen Any Good Biofilms Lately?,” Clin Microbiol Rev, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 155–166, Apr. 2002. [CrossRef]

- N. Aboelnaga et al., “Deciphering the dynamics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation: from molecular signaling to nanotherapeutic advances,” Cell Communication and Signaling, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 188, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. R. Korber, J. R. Lawrence, H. M. Lappin-Scott, and J. W. Costerton, “Growth of Microorganisms on Surfaces,” in Microbial Biofilms, Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 15–45. [CrossRef]

- R. C. S. Silva et al., “Titanium Dental Implants: An Overview of Applied Nanobiotechnology to Improve Biocompatibility and Prevent Infections,” Materials, vol. 15, no. 9, p. 3150, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen, Z. Wang, W. Qiu, and F. Fang, “Overview of Antibacterial Strategies of Dental Implant Materials for the Prevention of Peri-Implantitis,” Apr. 21, 2021, American Chemical Society. [CrossRef]

- G. Li, H. Jiang, and F. Yang, “A Novel Diffuse Plasma Jet Without Airflow and Its Application in the Real-Time Surface Modification of Titanium,” IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science, vol. 50, no. 11, pp. 4603–4611, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhu, W. Chu, J. Luo, J. Yang, L. He, and J. Li, “Dental Materials for Oral Microbiota Dysbiosis: An Update,” Front Cell Infect Microbiol, vol. 12, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S.-J. An, J.-U. Namkung, K.-W. Ha, H.-K. Jun, H. Y. Kim, and B.-K. Choi, “Inhibitory effect of d-arabinose on oral bacteria biofilm formation on titanium discs,” Anaerobe, vol. 75, p. 102533, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Masurier et al., “Site-specific grafting on titanium surfaces with hybrid temporin antibacterial peptides,” J Mater Chem B, vol. 6, no. 12, pp. 1782–1790, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Wan et al., “Study on the osteogenesis of rat mesenchymal stem cells and the long-term antibacterial activity of <scp> Staphylococcus epidermidis </scp> on the surface of silver-rich <scp>TiN</scp> /Ag modified titanium alloy,” J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater, vol. 108, no. 7, pp. 3008–3021, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Wang et al., “Antibacterial effects of titanium embedded with silver nanoparticles based on electron-transfer-induced reactive oxygen species,” Biomaterials, vol. 124, pp. 25–34, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Hardes et al., “The Influence of Elementary Silver Versus Titanium on Osteoblasts Behaviour In Vitro Using Human Osteosarcoma Cell Lines,” Sarcoma, vol. 2007, pp. 1–5, 2007. [CrossRef]

- F. Heidenau et al., “A novel antibacterial titania coating: Metal ion toxicity and in vitro surface colonization,” J Mater Sci Mater Med, vol. 16, no. 10, pp. 883–888, Oct. 2005. [CrossRef]

- F. Heidenau et al., “A novel antibacterial titania coating: Metal ion toxicity and in vitro surface colonization,” J Mater Sci Mater Med, vol. 16, no. 10, pp. 883–888, Oct. 2005. [CrossRef]

- W.-L. Du, S.-S. Niu, Y.-L. Xu, Z.-R. Xu, and C.-L. Fan, “Antibacterial activity of chitosan tripolyphosphate nanoparticles loaded with various metal ions,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 75, no. 3, pp. 385–389, Feb. 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. Xia, D. Cai, J. Tan, K. Li, Y. Qiao, and X. Liu, “Synergistic Effects of N/Cu Dual Ions Implantation on Stimulating Antibacterial Ability and Angiogenic Activity of Titanium,” ACS Biomater Sci Eng, vol. 4, no. 9, pp. 3185–3193, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Yu, G. Jin, L. Ouyang, D. Wang, Y. Qiao, and X. Liu, “Antibacterial activity, osteogenic and angiogenic behaviors of copper-bearing titanium synthesized by PIII&D,” J Mater Chem B, vol. 4, no. 7, pp. 1296–1309, 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Antoniazzi et al., “Effects of Cu2+ and Cu+ on the proliferation, differentiation and calcification of primary mouse osteoblasts in vitro,” Phys Rev D Part Fields, vol. 46, no. 11, pp. 4828–4835, Dec. 1992. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhang, L. Ren, Y. Zhang, N. Xue, K. Yang, and M. Zhong, “Antibacterial activity against Porphyromonas gingivalis and biological characteristics of antibacterial stainless steel,” Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces, vol. 105, pp. 51–57, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. O. Noyce, H. Michels, and C. W. Keevil, “Potential use of copper surfaces to reduce survival of epidemic meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the healthcare environment,” Journal of Hospital Infection, vol. 63, no. 3, pp. 289–297, Jul. 2006. [CrossRef]

- J. O. Noyce, H. Michels, and C. W. Keevil, “Use of Copper Cast Alloys To Control Escherichia coli O157 Cross-Contamination during Food Processing,” Appl Environ Microbiol, vol. 72, no. 6, pp. 4239–4244, Jun. 2006. [CrossRef]

- L. P. T. M. Zevenhuizen, J. Dolfing, E. J. Eshuis, and I. J. Scholten-Koerselman, “Inhibitory effects of copper on bacteria related to the free ion concentration,” Microb Ecol, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 139–146, Jun. 1979. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Almoudi, A. S. Hussein, M. I. Abu Hassan, and N. Mohamad Zain, “A systematic review on antibacterial activity of zinc against Streptococcus mutans,” Saudi Dent J, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 283–291, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Li, Q. Li, M. Zhao, L. Dong, J. Wu, and D. Li, “Effects of Zn and Ag Ratio on Cell Adhesion and Antibacterial Properties of Zn/Ag Coimplanted TiN,” ACS Biomater Sci Eng, vol. 5, no. 7, pp. 3303–3310, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Yamaguchi, H. Oishi, and Y. Suketa, “Stimulatory effect of zinc on bone formation in tissue culture,” Biochem Pharmacol, vol. 36, no. 22, pp. 4007–4012, Nov. 1987. [CrossRef]

- W.-L. Du, S.-S. Niu, Y.-L. Xu, Z.-R. Xu, and C.-L. Fan, “Antibacterial activity of chitosan tripolyphosphate nanoparticles loaded with various metal ions,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 75, no. 3, pp. 385–389, Feb. 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. Wang et al., “Where does the toxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles come from: The nanoparticles, the ions, or a combination of both?,” J Hazard Mater, vol. 308, pp. 328–334, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Heidenau et al., “A novel antibacterial titania coating: Metal ion toxicity and in vitro surface colonization,” J Mater Sci Mater Med, vol. 16, no. 10, pp. 883–888, Oct. 2005. [CrossRef]

- H. Kokkonen, C. Cassinelli, R. Verhoef, M. Morra, H. A. Schols, and J. Tuukkanen, “Differentiation of Osteoblasts on Pectin-Coated Titanium,” Biomacromolecules, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 2369–2376, Sep. 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. Irshad, R. Jawad, Q. Mushtaq, A. Spalletta, P. Martin, and U. Ishtiaq, “Determination of antibacterial and antioxidant potential of organic crude extracts from Malus domestica, Cinnamomum verum and Trachyspermum ammi,” Sci Rep, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 976, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Jain, J. Dixit, and D. Prakash, “Modulatory effects of Cissus quadrangularis on periodontal regeneration by bovine-derived hydroxyapatite in intrabony defects: exploratory clinical trial.,” J Int Acad Periodontol, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 59–65, Apr. 2008.

- K. N. Chidambara Murthy, A. Vanitha, M. Mahadeva Swamy, and G. A. Ravishankar, “Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Cissus quadrangularis L.,” J Med Food, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 99–105, Jul. 2003. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim et al., “The Effect of Safflower Seed Extract on Periodontal Healing of 1-Wall Intrabony Defects in Beagle Dogs,” J Periodontol, vol. 73, no. 12, pp. 1457–1466, Dec. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Aurora DOBRIN and Gabriela POPA, “799 EVALUATION OF THE ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY OF CARTHAMUS TINCTORIUS EXTRACTS AGAINST NOSOCOMIAL MICROORGANISMS,” Scientific Papers. Series B, Horticulture, vol. 1, pp. 799–811, 2022.

- A. Merolli, L. Nicolais, L. Ambrosio, and M. Santin, “A degradable soybean-based biomaterial used effectively as a bone filler in vivo in a rabbit,” Biomedical Materials, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 015008, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Hosseini Chaleshtori, M. Ataie Kachoie, and S. M. Hashemi Jazi, “Antibacterial effects of the methanolic extract of Glycine Max (Soybean),” Microbiol Res (Pavia), vol. 8, no. 2, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Agrawal, A. Reche, S. Agrawal, and P. Paul, “Applications of Chitosan Nanoparticles in Dentistry: A Review,” Cureus, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C.-L. Ke, F.-S. Deng, C.-Y. Chuang, and C.-H. Lin, “Antimicrobial Actions and Applications of Chitosan,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 13, no. 6, p. 904, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W.-H. Lo, F.-S. Deng, C.-J. Chang, and C.-H. Lin, “Synergistic Antifungal Activity of Chitosan with Fluconazole against Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, and Fluconazole-Resistant Strains,” Molecules, vol. 25, no. 21, p. 5114, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Tahsin, W. Xu, D. Watson, A. Rizkalla, and P. Charpentier, “Antimicrobial Denture Material Synthesized from Poly(methyl methacrylate) Enriched with Cannabidiol Isolates,” Molecules, vol. 30, no. 4, p. 943, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. Beyth, I. Yudovin-Farber, R. Bahir, A. J. Domb, and E. I. Weiss, “Antibacterial activity of dental composites containing quaternary ammonium polyethylenimine nanoparticles against Streptococcus mutans,” Biomaterials, vol. 27, no. 21, pp. 3995–4002, Jul. 2006. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, Y. Wang, S. Liao, Z. T. Wen, and Y. Fan, “Synthesis and characterization of antibacterial dental monomers and composites,” J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater, vol. 100B, no. 4, pp. 1151–1162, May 2012. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu and S. Costin, “CHAPTER 10. Antimicrobial Polymeric Dental Materials,” 2013, pp. 279–309. [CrossRef]

- S. Imazato, T. Imai, R. R. B. Russell, M. Torii, and S. Ebisu, “Antibacterial activity of cured dental resin incorporating the antibacterial monomer MDPB and an adhesion-promoting monomer,” J Biomed Mater Res, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 511–515, Mar. 1998. [CrossRef]

- S. Imazato, M. Torii, Y. Tsuchitani, J. F. McCabe, and R. R. B. Russell, “Incorporation of Bacterial Inhibitor into Resin Composite,” J Dent Res, vol. 73, no. 8, pp. 1437–1443, Aug. 1994. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ge, S. Wang, X. Zhou, H. Wang, H. Xu, and L. Cheng, “The Use of Quaternary Ammonium to Combat Dental Caries,” Materials, vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 3532–3549, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen, B. I. Suh, and J. Yang, “Antibacterial dental restorative materials: A review.,” Am J Dent, vol. 31, no. Sp Is B, pp. 6B-12B, Nov. 2018.

- US Food and Drug Admistration, “Sec. 172.165 Quaternary ammonium chloride combination. ,” Jan. 1985. Accessed: Jan. 30, 2025. Online.. Available: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=172.165.

- Z. Zhou et al., “Quaternary Ammonium Salts: Insights into Synthesis and New Directions in Antibacterial Applications,” Bioconjug Chem, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 302–325, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Ioannou, G. W. Hanlon, and S. P. Denyer, “Action of Disinfectant Quaternary Ammonium Compounds against Staphylococcus aureus,” Antimicrob Agents Chemother, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 296–306, Jan. 2007. [CrossRef]

- A. Luz, P. DeLeo, N. Pechacek, and M. Freemantle, “Human health hazard assessment of quaternary ammonium compounds: Didecyl dimethyl ammonium chloride and alkyl (C12–C16) dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride,” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, vol. 116, p. 104717, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Ye et al., “π–π conjugations improve the long-term antibacterial properties of graphene oxide/quaternary ammonium salt nanocomposites,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 304, pp. 873–881, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. L. Padnya et al., “Thiacalixarene based quaternary ammonium salts as promising antibacterial agents,” Bioorg Med Chem, vol. 29, p. 115905, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang et al., “Design and production of environmentally degradable quaternary ammonium salts,” Green Chemistry, vol. 23, no. 17, pp. 6548–6554, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Benkova et al., “Synthesis, Antimicrobial Effect and Lipophilicity-Activity Dependence of Three Series of Dichained N -Alkylammonium Salts,” ChemistrySelect, vol. 4, no. 41, pp. 12076–12084, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhi et al., “Synthesis and Performance of Double-Chain Quaternary Ammonium Salt Glucosamide Surfactants,” Molecules, vol. 27, no. 7, p. 2149, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Murata, R. R. Koepsel, K. Matyjaszewski, and A. J. Russell, “Permanent, non-leaching antibacterial surfaces—2: How high density cationic surfaces kill bacterial cells,” Biomaterials, vol. 28, no. 32, pp. 4870–4879, Nov. 2007. [CrossRef]

- D. Xie, Y. Weng, X. Guo, J. Zhao, R. L. Gregory, and C. Zheng, “Preparation and evaluation of a novel glass-ionomer cement with antibacterial functions,” Dental Materials, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 487–496, May 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Cheng, M. D. Weir, K. Zhang, D. D. Arola, X. Zhou, and H. H. K. Xu, “Dental primer and adhesive containing a new antibacterial quaternary ammonium monomer dimethylaminododecyl methacrylate,” J Dent, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 345–355, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhou, M. D. Weir, K. Zhang, D. Deng, L. Cheng, and H. H. K. Xu, “Synthesis of new antibacterial quaternary ammonium monomer for incorporation into CaP nanocomposite,” Dental Materials, vol. 29, no. 8, pp. 859–870, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. A. S. Melo, J. Wu, M. D. Weir, and H. H. K. Xu, “Novel antibacterial orthodontic cement containing quaternary ammonium monomer dimethylaminododecyl methacrylate,” J Dent, vol. 42, no. 9, pp. 1193–1201, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Li, M. D. Weir, A. F. Fouad, and H. H. K. Xu, “Effect of salivary pellicle on antibacterial activity of novel antibacterial dental adhesives using a dental plaque microcosm biofilm model,” Dental Materials, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 182–191, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang et al., “Antibacterial Effect of Dental Adhesive Containing Dimethylaminododecyl Methacrylate on the Development of Streptococcus mutans Biofilm,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 15, no. 7, pp. 12791–12806, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhang et al., “Effect of Antibacterial Dental Adhesive on Multispecies Biofilms Formation,” J Dent Res, vol. 94, no. 4, pp. 622–629, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. D. Marsh and D. J. Bradshaw, “Dental plaque as a biofilm,” J Ind Microbiol, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 169–175, Sep. 1995. [CrossRef]

- D. H. Pashley et al., “Collagen Degradation by Host-derived Enzymes during Aging,” J Dent Res, vol. 83, no. 3, pp. 216–221, Mar. 2004. [CrossRef]

- C. Chen et al., “Antibacterial activity and ion release of bonding agent containing amorphous calcium phosphate nanoparticles,” Dental Materials, vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 891–901, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhang, L. Cheng, E. J. Wu, M. D. Weir, Y. Bai, and H. H. K. Xu, “Effect of water-ageing on dentine bond strength and anti-biofilm activity of bonding agent containing new monomer dimethylaminododecyl methacrylate,” J Dent, vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 504–513, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- F. Li, M. D. Weir, and H. H. K. Xu, “Effects of Quaternary Ammonium Chain Length on Antibacterial Bonding Agents,” J Dent Res, vol. 92, no. 10, pp. 932–938, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- F. Li, M. D. Weir, A. F. Fouad, and H. H. K. Xu, “Time-kill behaviour against eight bacterial species and cytotoxicity of antibacterial monomers,” J Dent, vol. 41, no. 10, pp. 881–891, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- F. Li, P. Wang, M. D. Weir, A. F. Fouad, and H. H. K. Xu, “Evaluation of antibacterial and remineralizing nanocomposite and adhesive in rat tooth cavity model,” Acta Biomater, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 2804–2813, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhou, F. Li, M. D. Weir, and H. H. K. Xu, “Dental plaque microcosm response to bonding agents containing quaternary ammonium methacrylates with different chain lengths and charge densities,” J Dent, vol. 41, no. 11, pp. 1122–1131, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- F. Li, M. D. Weir, J. Chen, and H. H. K. Xu, “Effect of charge density of bonding agent containing a new quaternary ammonium methacrylate on antibacterial and bonding properties,” Dental Materials, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 433–441, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- N. Zhang, J. Ma, M. A. S. Melo, M. D. Weir, Y. Bai, and H. H. K. Xu, “Protein-repellent and antibacterial dental composite to inhibit biofilms and caries,” J Dent, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 225–234, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Karakullukcu, E. Taban, and O. O. Ojo, “Biocompatibility of biomaterials and test methods: a review,” Materials Testing, vol. 65, no. 4, pp. 545–559, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. D. Al-Shalawi et al., “Biomaterials as Implants in the Orthopedic Field for Regenerative Medicine: Metal versus Synthetic Polymers,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 12, p. 2601, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Binlateh, P. Thammanichanon, P. Rittipakorn, N. Thinsathid, and P. Jitprasertwong, “Collagen-Based Biomaterials in Periodontal Regeneration: Current Applications and Future Perspectives of Plant-Based Collagen,” Biomimetics, vol. 7, no. 2, p. 34, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Talha, C. K. Behera, and O. P. Sinha, “A review on nickel-free nitrogen containing austenitic stainless steels for biomedical applications,” Materials Science and Engineering: C, vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 3563–3575, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Niinomi, “Mechanical properties of biomedical titanium alloys,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 243, no. 1–2, pp. 231–236, Mar. 1998. [CrossRef]

- A. Palmquist, O. M. Omar, M. Esposito, J. Lausmaa, and P. Thomsen, “Titanium oral implants: surface characteristics, interface biology and clinical outcome,” J R Soc Interface, vol. 7, no. suppl_5, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. P. Staiger, A. M. Pietak, J. Huadmai, and G. Dias, “Magnesium and its alloys as orthopedic biomaterials: A review,” Biomaterials, vol. 27, no. 9, pp. 1728–1734, Mar. 2006. [CrossRef]

- F. Zhang et al., “Corrosion behavior of mesoporous bioglass-ceramic coated magnesium alloy under applied forces,” J Mech Behav Biomed Mater, vol. 56, pp. 146–155, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H.-Y. Wang et al., “Effect of sandblasting intensity on microstructures and properties of pure titanium micro-arc oxidation coatings in an optimized composite technique,” Appl Surf Sci, vol. 292, pp. 204–212, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Palmquist, O. M. Omar, M. Esposito, J. Lausmaa, and P. Thomsen, “Titanium oral implants: surface characteristics, interface biology and clinical outcome,” J R Soc Interface, vol. 7, no. suppl_5, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- H.-Y. Wang et al., “Effect of sandblasting intensity on microstructures and properties of pure titanium micro-arc oxidation coatings in an optimized composite technique,” Appl Surf Sci, vol. 292, pp. 204–212, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Civantos, E. Martínez-Campos, V. Ramos, C. Elvira, A. Gallardo, and A. Abarrategi, “Titanium Coatings and Surface Modifications: Toward Clinically Useful Bioactive Implants,” ACS Biomater Sci Eng, vol. 3, no. 7, pp. 1245–1261, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Y. Wang et al., “Effect of sandblasting intensity on microstructures and properties of pure titanium micro-arc oxidation coatings in an optimized composite technique,” Appl Surf Sci, vol. 292, pp. 204–212, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Palmquist, O. M. Omar, M. Esposito, J. Lausmaa, and P. Thomsen, “Titanium oral implants: surface characteristics, interface biology and clinical outcome,” J R Soc Interface, vol. 7, no. suppl_5, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Catauro, F. Bollino, and F. Papale, “Biocompatibility improvement of titanium implants by coating with hybrid materials synthesized by sol-gel technique,” J Biomed Mater Res A, p. n/a-n/a, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Midha, T. B. Kim, W. Van Den Bergh, P. D. Lee, J. R. Jones, and C. A. Mitchell, “Preconditioned 70S30C bioactive glass foams promote osteogenesis in vivo,” Acta Biomater, vol. 9, no. 11, pp. 9169–9182, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Niinomi, “Recent metallic materials for biomedical applications,” Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 477–486, Mar. 2002. [CrossRef]

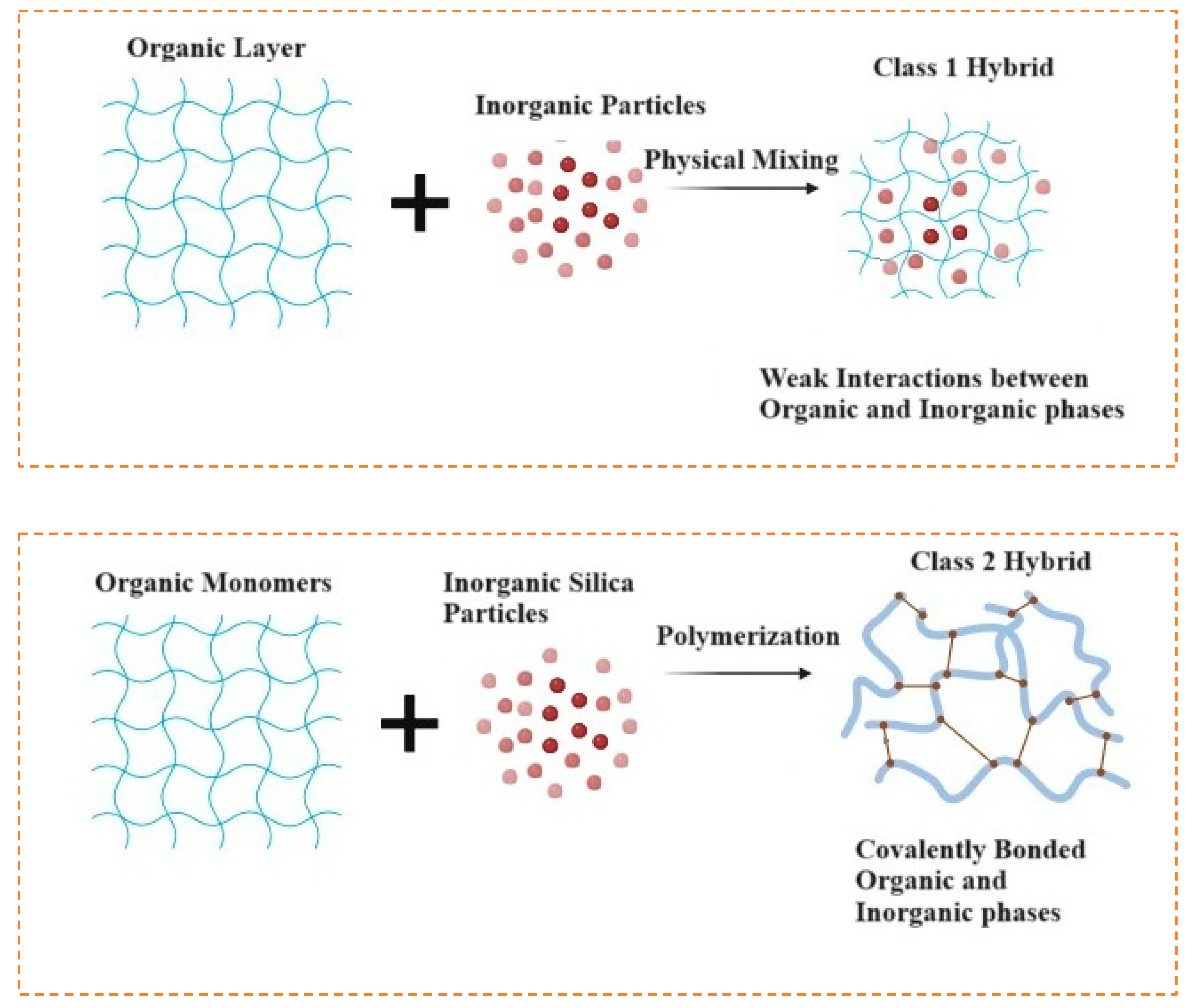

- G. Kickelbick, “Introduction to Hybrid Materials,” in Hybrid Materials, Wiley, 2006, pp. 1–48. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Novak, “Hybrid Nanocomposite Materials—between inorganic glasses and organic polymers,” Advanced Materials, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 422–433, Jun. 1993. [CrossRef]

- D. Grosso, F. Ribot, C. Boissiere, and C. Sanchez, “Molecular and supramolecular dynamics of hybrid organic–inorganic interfaces for the rational construction of advanced hybrid nanomaterials,” Chem. Soc. Rev., vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 829–848, 2011. [CrossRef]

- C. Sanchez, B. Julián, P. Belleville, and M. Popall, “Applications of hybrid organic–inorganic nanocomposites,” J Mater Chem, vol. 15, no. 35–36, p. 3559, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Z. Khurshid et al., “Novel Techniques of Scaffold Fabrication for Bioactive Glasses,” Biomedical, Therapeutic and Clinical Applications of Bioactive Glasses, pp. 497–519, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Dong et al., “Surface Modified Techniques and Emerging Functional Coating of Dental Implants,” Coatings, vol. 10, no. 11, p. 1012, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. U. Habibah, D. V. Amlani, and M. Brizuela, Hydroxyapatite Dental Material. 2025.

- M. A. Islam et al., “Advances of Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles in Dental Implant Applications,” Int Dent J, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Al-Noaman, S. C. F. Rawlinson, and R. G. Hill, “MgF2- containing glasses as a coating for titanium dental implant. I- Glass powder,” J Mech Behav Biomed Mater, vol. 125, p. 104948, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. anne N. Oliver, Y. Su, X. Lu, P. H. Kuo, J. Du, and D. Zhu, “Bioactive glass coatings on metallic implants for biomedical applications,” Bioact Mater, vol. 4, pp. 261–270, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Rohr et al., “Influence of bioactive glass-coating of zirconia implant surfaces on human osteoblast behavior in vitro,” Dental Materials, vol. 35, no. 6, pp. 862–870, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhang, X. Pu, X. Chen, and G. Yin, “In-vivo performance of plasma-sprayed CaO–MgO–SiO2-based bioactive glass-ceramic coating on Ti–6Al–4V alloy for bone regeneration,” Heliyon, vol. 5, no. 11, p. e02824, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Hu et al., “Different response of osteoblastic cells to Mg2+, Zn2+ and Sr2+ doped calcium silicate coatings,” J Mater Sci Mater Med, vol. 27, no. 3, p. 56, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- I. Kinnunen, K. Aitasalo, M. Pöllönen, and M. Varpula, “Reconstruction of orbital floor fractures using bioactive glass,” Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 229–234, Aug. 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Zafar, I. Farooq, M. Awais, S. Najeeb, Z. Khurshid, and S. Zohaib, “Bioactive Surface Coatings for Enhancing Osseointegration of Dental Implants,” Biomedical, Therapeutic and Clinical Applications of Bioactive Glasses, pp. 313–329, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Yoshimura, H. Suda, K. Okamoto, and K. Ioku, “Hydrothermal synthesis of biocompatible whiskers,” J Mater Sci, vol. 29, no. 13, pp. 3399–3402, Jul. 1994. [CrossRef]

- C. C. Silva, A. G. Pinheiro, M. A. R. Miranda, J. C. Góes, and A. S. B. Sombra, “Structural properties of hydroxyapatite obtained by mechanosynthesis,” Solid State Sci, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 553–558, Apr. 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Saeri, A. Afshar, M. Ghorbani, N. Ehsani, and C. C. Sorrell, “The wet precipitation process of hydroxyapatite,” Mater Lett, vol. 57, no. 24–25, pp. 4064–4069, Aug. 2003. [CrossRef]

- W.-J. Shih, Y.-F. Chen, M.-C. Wang, and M.-H. Hon, “Crystal growth and morphology of the nano-sized hydroxyapatite powders synthesized from CaHPO4·2H2O and CaCO3 by hydrolysis method,” J Cryst Growth, vol. 270, no. 1–2, pp. 211–218, Sep. 2004. [CrossRef]

- I.-S. Kim and P. N. Kumta, “Sol–gel synthesis and characterization of nanostructured hydroxyapatite powder,” Materials Science and Engineering: B, vol. 111, no. 2–3, pp. 232–236, Aug. 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. Pandey and S. B. Mishra, “Sol–gel derived organic–inorganic hybrid materials: synthesis, characterizations and applications,” J Solgel Sci Technol, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 73–94, Jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. L. Hench and J. K. West, “The sol-gel process,” Chem Rev, vol. 90, no. 1, pp. 33–72, Jan. 1990. [CrossRef]

- W. Al Zoubi, M. P. Kamil, S. Fatimah, N. Nisa, and Y. G. Ko, “Recent advances in hybrid organic-inorganic materials with spatial architecture for state-of-the-art applications,” Prog Mater Sci, vol. 112, p. 100663, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Jones, “Review of bioactive glass: From Hench to hybrids,” Acta Biomater, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 4457–4486, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. Mondal, S. J. Dixon, K. Mequanint, and A. S. Rizkalla, “Bioactivity, Degradation, and Mechanical Properties of Poly(vinylpyrrolidone- co -triethoxyvinylsilane)/Tertiary Bioactive Glass Hybrids,” ACS Appl Bio Mater, vol. 1, no. 5, pp. 1369–1381, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Cinici, S. Yaba, M. Kurt, H. C. Yalcin, L. Duta, and O. Gunduz, “Fabrication Strategies for Bioceramic Scaffolds in Bone Tissue Engineering with Generative Design Applications,” Biomimetics, vol. 9, no. 7, p. 409, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Gao, M. A. Seles, and M. Rajan, “Role of bioglass derivatives in tissue regeneration and repair: A review,” REVIEWS ON ADVANCED MATERIALS SCIENCE, vol. 62, no. 1, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Bokov et al., “Nanomaterial by Sol-Gel Method: Synthesis and Application,” Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 2021, no. 1, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Zvonkina and M. Soucek, “Inorganic–organic hybrid coatings: common and new approaches,” Curr Opin Chem Eng, vol. 11, pp. 123–127, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. Tranquillo and F. Bollino, “Surface Modifications for Implants Lifetime extension: An Overview of Sol-Gel Coatings,” Coatings, vol. 10, no. 6, p. 589, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Catauro et al., “Coating of Titanium Substrates with ZrO2 and ZrO2-SiO2 Composites by Sol-Gel Synthesis for Biomedical Applications: Structural Characterization, Mechanical and Corrosive Behavior,” Coatings, vol. 9, no. 3, p. 200, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Mendhe, “Spin Coating: Easy Technique for Thin Films.,” in Simple Chemical Methods for Thin Film Deposition: Synthesis and Applications, Singapore: Springer, 2023, pp. 387-424.

- R. Gvishi and I. Sokolov, “3D sol–gel printing and sol–gel bonding for fabrication of macro- and micro/nano-structured photonic devices,” J Solgel Sci Technol, vol. 95, no. 3, pp. 635–648, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Kawashita, S. Tsuneyama, F. Miyaji, T. Kokubo, H. Kozuka, and K. Yamamoto, “Antibacterial silver-containing silica glass prepared by sol–gel method,” Biomaterials, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 393–398, Feb. 2000. [CrossRef]

- A. Bachvarova-Nedelcheva et al., “Sol–Gel Synthesis of Silica–Poly (Vinylpyrrolidone) Hybrids with Prooxidant Activity and Antibacterial Properties,” Molecules, vol. 29, no. 11, p. 2675, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Bryaskova, D. Pencheva, G. M. Kale, U. Lad, and T. Kantardjiev, “Synthesis, characterisation and antibacterial activity of PVA/TEOS/Ag-Np hybrid thin films,” J Colloid Interface Sci, vol. 349, no. 1, pp. 77–85, Sep. 2010. [CrossRef]

- G. J. Copello, S. Teves, J. Degrossi, M. D’Aquino, M. F. Desimone, and L. E. Diaz, “Antimicrobial activity on glass materials subject to disinfectant xerogel coating,” J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 343–348, May 2006. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Nablo, A. R. Rothrock, and M. H. Schoenfisch, “Nitric oxide-releasing sol–gels as antibacterial coatings for orthopedic implants,” Biomaterials, vol. 26, no. 8, pp. 917–924, Mar. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Y. S. Ubhale and A. P. More, “Antimicrobial sol–gel coating: a review,” J Coat Technol Res, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. N. Gunawidjaja et al., “Biomimetic Apatite Mineralization Mechanisms of Mesoporous Bioactive Glasses as Probed by Multinuclear 31 P, 29 Si, 23 Na and 13 C Solid-State NMR,” The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, vol. 114, no. 45, pp. 19345–19356, Nov. 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. L. Hench, “Chronology of Bioactive Glass Development and Clinical Applications,” New Journal of Glass and Ceramics, vol. 03, no. 02, pp. 67–73, 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. E. Skallevold, D. Rokaya, Z. Khurshid, and M. S. Zafar, “Bioactive Glass Applications in Dentistry,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 20, no. 23, p. 5960, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Gonzalez Moreno, M. E. Butini, E. M. Maiolo, L. Sessa, and A. Trampuz, “Antimicrobial activity of bioactive glass S53P4 against representative microorganisms causing osteomyelitis – Real-time assessment by isothermal microcalorimetry,” Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces, vol. 189, p. 110853, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jiao, L.-N. Niu, S. Ma, J. Li, F. R. Tay, and J.-H. Chen, “Quaternary ammonium-based biomedical materials: State-of-the-art, toxicological aspects and antimicrobial resistance.,” Prog Polym Sci, vol. 71, pp. 53–90, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. Grabińska-Sota, “Genotoxicity and biodegradation of quaternary ammonium salts in aquatic environments,” J Hazard Mater, vol. 195, pp. 182–187, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- “Pilot Project Make more antimicrobials available,” Jan. 2025.

- “Device and surgical procedure-related infections in Canadian acute care hospitals, 2017−2021,” Canada Communicable Disease Report, vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 221–234, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Tande and R. Patel, “Prosthetic Joint Infection,” Clin Microbiol Rev, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 302–345, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Lee, R. R. Koepsel, S. W. Morley, K. Matyjaszewski, Y. Sun, and A. J. Russell, “Permanent, Nonleaching Antibacterial Surfaces. 1. Synthesis by Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization,” Biomacromolecules, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 877–882, May 2004. [CrossRef]

- P. Teper, A. Celny, A. Kowalczuk, and B. Mendrek, “Quaternized Poly(N,N′-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate) Star Nanostructures in the Solution and on the Surface,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 5, p. 1260, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Esteves, J. Esteves, M. Resende, L. Mendes, and A. S. Azevedo, “Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Coating of Dental Implants—Past and New Perspectives,” Antibiotics, vol. 11, no. 2, p. 235, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Wessels and H. Ingmer, “Modes of action of three disinfectant active substances: A review,” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 456–467, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu, C. Wu, T. Xu, and Y. Fu, “Novel anion-exchange organic–inorganic hybrid membranes prepared through sol–gel reaction of multi-alkoxy precursors,” J Memb Sci, vol. 329, no. 1–2, pp. 236–245, Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- E. Obłąk, A. Piecuch, K. Guz-Regner, and E. Dworniczek, “Antibacterial activity of gemini quaternary ammonium salts,” FEMS Microbiol Lett, vol. 350, no. 2, pp. 190–198, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Sigma-aldrich, “Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) assay kit sufficient for 500 multiwell testt.”.

- W. H. Habig, M. J. Pabst, and W. B. Jakoby, “Glutathione S-transferases. The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 249, no. 22, pp. 7130–9, Nov. 1974.

- F. Li, M. D. Weir, and H. H. K. Xu, “Effects of Quaternary Ammonium Chain Length on Antibacterial Bonding Agents,” J Dent Res, vol. 92, no. 10, pp. 932–938, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Y. Gu, W. Huang, M. N. Rahaman, and D. E. Day, “Bone regeneration in rat calvarial defects implanted with fibrous scaffolds composed of a mixture of silicate and borate bioactive glasses,” Acta Biomater, vol. 9, no. 11, pp. 9126–9136, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. L. Hench and J. K. West, The Sol-Gel Process. Chemical Reviews, 1990.

- B. Mahltig, C. Swaboda, A. Roessler, and H. Böttcher, “Functionalising wood by nanosol application,” J Mater Chem, vol. 18, no. 27, p. 3180, 2008. [CrossRef]

- B. Mahltig, H. Haufe, and H. Böttcher, “Functionalisation of textiles by inorganic sol–gel coatings,” J Mater Chem, vol. 15, no. 41, p. 4385, 2005. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Bapat et al., “Recent Update on Applications of Quaternary Ammonium Silane as an Antibacterial Biomaterial: A Novel Drug Delivery Approach in Dentistry,” Front Microbiol, vol. 13, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Q. Gong et al., “Quaternary ammonium silane-functionalized, methacrylate resin composition with antimicrobial activities and self-repair potential,” Acta Biomater, vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 3270–3282, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. Gilbert and A. Al-taae, “Antimicrobial activity of some alkyltrimethylammonium bromides,” Lett Appl Microbiol, vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 101–104, Jun. 1985. [CrossRef]

- S. Alkhalifa et al., “Analysis of the Destabilization of Bacterial Membranes by Quaternary Ammonium Compounds: A Combined Experimental and Computational Study,” ChemBioChem, vol. 21, no. 10, pp. 1510–1516, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Mahltig, T. Grethe, and H. Haase, “Antimicrobial Coatings Obtained by Sol–Gel Method,” in Handbook of Sol-Gel Science and Technology, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016, pp. 1–27. [CrossRef]

- W. Z. Xu, G. Gao, and J. F. Kadla, “Synthesis of antibacterial cellulose materials using a ‘clickable’ quaternary ammonium compound,” Cellulose, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 1187–1199, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- W. Z. Xu, L. Yang, and P. A. Charpentier, “Preparation of Antibacterial Softwood via Chemical Attachment of Quaternary Ammonium Compounds Using Supercritical CO 2,” ACS Sustain Chem Eng, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 1551–1561, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, W. Z. Xu, and P. A. Charpentier, “Synthesis of VO2/Poly(MMA-co-dMEMUABr) antimicrobial/thermochromic dual-functional coatings,” Prog Org Coat, vol. 142, p. 105589, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Dibakar Mondal, “ Covalently Crosslinked Organic/Inorganic Hybrid Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications,” Western University, London, Ontario, 2018.

- Y. Wu, C. Wu, T. Xu, F. Yu, and Y. Fu, “Novel anion-exchange organic–inorganic hybrid membranes: Preparation and characterizations for potential use in fuel cells,” J Memb Sci, vol. 321, no. 2, pp. 299–308, Aug. 2008. [CrossRef]

- F. M. He, G. L. Yang, Y. N. Li, X. X. Wang, and S. F. Zhao, “Early bone response to sandblasted, dual acid-etched and H2O2/HCl treated titanium implants: an experimental study in the rabbit,” Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg, vol. 38, no. 6, pp. 677–681, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, W. Z. Xu, and P. A. Charpentier, “Synthesis of VO2/Poly(MMA-co-dMEMUABr) antimicrobial/thermochromic dual-functional coatings,” Prog Org Coat, vol. 142, p. 105589, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. D. Christensen, W. A. Simpson, A. L. Bisno, and E. H. Beachey, “Adherence of slime-producing strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis to smooth surfaces,” Infect Immun, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 318–326, Jul. 1982. [CrossRef]

- D. Mondal, “Covalently Crosslinked Organic/Inorganic Hybrid Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications,” Electronic, Western University, London, 2018.

- O. Santoro and L. Izzo, “Antimicrobial Polymer Surfaces Containing Quaternary Ammonium Centers (QACs): Synthesis and Mechanism of Action,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 25, no. 14, p. 7587, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kim, S. Farrah, and R. H. Baney, “Silanol - A novel class of antimicrobial agent,” Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 176–180, Apr. 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Arya, N. K. Morsy, D. K. Islayem, S. A. Alkhatib, C. Pitsalidis, and A.-M. Pappa, “Bacterial Membrane Mimetics: From Biosensing to Disease Prevention and Treatment,” Biosensors (Basel), vol. 13, no. 2, p. 189, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Ambrosino et al., “Investigation of biocidal efficacy of commercial disinfectants used in public, private and workplaces during the pandemic event of SARS-CoV-2,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 5468, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Mitchell, A. A. Iannetta, M. C. Jennings, M. H. Fletcher, W. M. Wuest, and K. P. C. Minbiole, “Scaffold-Hopping of Multicationic Amphiphiles Yields Three New Classes of Antimicrobials,” ChemBioChem, vol. 16, no. 16, pp. 2299–2303, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. Gaspar, J. Rolo, N. Cerca, R. Palmeira-de-Oliveira, J. Martinez-de-Oliveira, and A. Palmeira-de-Oliveira, “Dequalinium Chloride Effectively Disrupts Bacterial Vaginosis (BV) Gardnerella spp. Biofilms,” Pathogens, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 261, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Joseph, A. Naugolny, M. Feldman, I. M. Herzog, M. Fridman, and Y. Cohen, “Cationic Pillararenes Potently Inhibit Biofilm Formation without Affecting Bacterial Growth and Viability,” J Am Chem Soc, vol. 138, no. 3, pp. 754–757, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Jung, J. Wen, and Y. Sun, “Amphiphilic quaternary ammonium chitosans self-assemble onto bacterial and fungal biofilms and kill adherent microorganisms,” Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces, vol. 174, pp. 1–8, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Qin, G. Yang, S. Wu, H. Zhang, and C. Zhu, “Synthesis, physicochemical characterization, antibacterial activity, and biocompatibility of quaternized hawthorn pectin,” Int J Biol Macromol, vol. 213, pp. 1047–1056, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Saverina, N. A. Frolov, O. A. Kamanina, V. A. Arlyapov, A. N. Vereshchagin, and V. P. Ananikov, “From Antibacterial to Antibiofilm Targeting: An Emerging Paradigm Shift in the Development of Quaternary Ammonium Compounds (QACs),” ACS Infect Dis, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 394–422, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Haase et al., “Toxicity of silver nanoparticles in human macrophages: uptake, intracellular distribution and cellular responses,” J Phys Conf Ser, vol. 304, p. 012030, Jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

| Type of implant (no. of patients/implants) | Most prevalent microbes detected (% sites infected with bacteria) |

|---|---|

|

Brånemark: System is a well-established and widely used dental implant system based on the principle of osseointegration. The original Brånemark implant was a cylindrical, pure titanium implant with smooth, polished screw-like threads |

Prevotella intermedia/P. nigrescens 60% Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans 60% Staphylococci, coliforms, Candida spp. 55% |

| Not stated |

Bacteroides forsythus 59% Spirochetes 54% Fusobacterium spp. 41% Peptostreptococcus micros 39% Porphyromonas gingivalis 27% |

| Titanium hollow cylinder implants (7/not stated) | Bacteroides spp., Fusobacterium spp., spirochetes, fusiform bacilli, motile and curved rods (% not stated) |

| Not stated (13/20) | Staphylococcus spp. 55% |

| Not stated (21/28) | P. nicrescens, P. micros, Fusobacterium nucleatum (% not stated) |

| IMZ: The IMZ (IntraMobil Zylinder) implant system was notable for its two-part design, which included an inner elastic intramobile element that aimed to mimic the natural flexibility of teeth. This design was meant to reduce stress on the bone and improve load distribution.However, IMZ implants are now considered outdated and are rarely used in modern implants. |

Bacteroides spp. 89% Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans 89% Fusobacterium nucleatum 22% Capnocytophaga spp. 27.8% Eikenella corrodens 17% |

|

Astra : widely used in implant dentistry by OsseoSpeed™ surfaces, Micro Thread Technology, with Conical design, reducing complications like peri-implantitis. Astra implants come in various lengths and diameters, making them versatile for different clinical cases, including single tooth replacement, multiple teeth, and full-arch reconstructions. ITI Staumann: Made of Titanium-zirconium alloy that is stronger than pure titanium, allowing for smaller implants with high strength—ideal for patients with limited bone. SLActive® Surface, modified hydrophilic implant surface speeds up osseointegration, reducing healing time. Esthetic finishing in visible areas. Morse Taper Connection for antimicrobial effects. |

Actinomyces spp. 83% F. nucleatum 70% P. intermedia/nigrescens group 60% Steptococcus anginosus (milleri) group 70% P. micros 63% Enterococcus spp. 30% Yeast spp. 30% |

| Metal | Features | Toxicity Profile | Antimicrobial ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silver | An early report on the formation of a TiN/Ag-modified titanium alloy by a multiarc ion-plating and ion implantation system and its in vitro result showed stable antimicrobial ability against Staphylococcus epidermidis for over 12 weeks[51]. To explore the antibacterial mechanism of Ag-implanted titanium surfaces, embedded Ag into Ti, Si, and SiO2 by PIII. [52] They found that electron transfer between the AgNPs and Ti is the first step. |

Silver at low concentrations was not cytotoxic for osteoblast in vitro[53] Studies showed that Ag+, Zn2+ and Hg2+ ions are very cytotoxic even at low concentrations [54] |

Effective against S. choleraesuis, E. coli[55], S. aureus, S. epidermis [56] |

| Copper | N/Cu-incorporated Ti formed by PIII had a good antibacterial effect against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli with promotion of angiogenic activity endowed by the Cu and outstanding corrosion resistance endowed by TiN[57]. However, another study has shown that different forms of Cu (metallic Cu or Cu -NPs) in the coating were dependent on the parameters of the synthesis techniques, which led to different physicochemical properties, such as metallic Cu having better antibacterial ability and biocompatibility than CuNPs [58]. This study highlighted the importance of the preparation technology parameters, for they ultimately affect the antibacterial effect and biocompatibility of the surface. |

Essential metal ion functioning of organs and metabolic processes[121]. Cu deficiency result in anemia, heart disease, arthritis, and osteoporosis, etc. [122]. Cu ion promotes osteoblast proliferation, differentiation and migration [59]. High concentrations of Cu ions inhibits growth and is causes cell death and toxicity on humans [60] |

Effective against MRSA [61]and E. coli [62]within a few hours. Copper inhibited K. aerogenes[63] and S. aureus[61]. |

| Zinc | Zinc, ZnO, nano ZnO and Zn2+ ion release is an antibacterial agent. Used as dental and formulated into oral health products to control plaque such us mouth rinses and toothpaste[64]. Ti surface with Zn- Ag increased ratio of Zn and made up for the inhibition of Ag on cell adhesion and growth of fibroblast-like cells[65]. |

Zn ion is not harmful to cells, and it is known for a long time that zinc can help bones grow. Zinc is an important part of making DNA, enzymes working, nucleic acid processing, biomineralization, and hormone action [66] | Effective against S.aureus; E.coli; S.choleraesuis, [67] P. phosphoreum, [68] S. epidermis[69] |

| Phytochemical | Material | Application | Antimicrobial Efficancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malus domesticaL. | Titanium implant coating[70] | Dental implantology |

Streptococcus mutans, Salmonella typhi bacteria responsible for dental caries and periodontal diseases[71]. Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Listeria monocytogenes |

| Cissus quadrangularisL. | Periodontal filler in association with hydroxyapatite[72]. | Periodontal regeneration | Gram-positive bacteria [73]: Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus species |

| Carthamus tinctoriusL | Periodontal filler in association with collagen sponge. Periodontal filler in association with polylactide glycolic acid bioresorbable barrier[74]. | Periodontal regeneration. |

Escherichia coli (E. coli), Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumonia), Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Salmonella spp[75] |

| Glycine maxL. | Bone filler [76]. | Alveolar bone regeneration |

K. pneumoniae, L. monocytogenes S. aureus[77] |

| Chitosan | The mycelial cell walls of fungi consist of chitin, glucan and glycoproteins. Chitin is upto 45 % of the cell wall of Aspergillus niger and Mucor rouxii, Penicillium notatum. Chitosan is obtained from chitin by undergoing the process of deacetylation. | Guided tissue regeneration (GTR) , hydrogel made of chitosan was developed with the purpose of delivering amelogenin, Dentin Bonding and Adhesion, coating of dental implants [78]. | Prevents biofilm formation of S. aureus, P.Aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis and E. coli[79]. Antifungal against Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, and other Candida species[80]. |

| Cannabidiol (CBD), derived from the Cannabis plant, | PMMA restorations | To minimize denture-associated infections, antimicrobial enhancements to PMMA, the primary material for dentures, were coated with CBD nanoparticles[81]. | Antimicrobial activity against : Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus agalactiae[81]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).