1. Introduction

Metal nanoclusters (NCs), typically composed of a few to a hundred atoms, occupy a unique regime between discrete molecules and larger nanoparticles (NPs). Unlike conventional NPs, which display continuous electronic bands [

1], NCs exhibit molecule-like properties, including quantized energy levels, HOMO–LUMO transitions, and distinct photoluminescence [

2]. Their ultrasmall core size (typically <3 nm) results in a high fraction of surface atoms and well-defined atomic configurations, granting them exceptional optical, catalytic, and electronic characteristics that are highly sensitive to size, core composition and capping ligands, and surface environment. This atomic precision allows NCs to outperform traditional NPs in many applications where tunability, reproducibility, or biocompatibility are essential.

A defining feature of metal NCs is their strong and tunable photoluminescence, which arises from their discrete electronic states and ligand–metal interactions [

3]. Several emission mechanisms have been proposed to account for the observed fluorescence in NCs, depending on their composition, size, and surface chemistry. In many cases, photoluminescence is attributed to ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) or ligand-to-metal–metal charge transfer (LMMCT), particularly in thiolate- or protein-protected NCs [

4,

5]. These mechanisms involve excitation-induced electron transfer from the surface ligands to the metal core or between metal atoms modulated by the ligand shell, followed by radiative recombination [

6]. In some systems, phosphorescence-like behavior with long lifetimes and large Stokes shifts suggests involvement of triplet states or surface-state-mediated emission [

7,

8,

9]. More recently, intersystem crossing and aggregation-induced emission (AIE) effects have also been identified [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. These diverse mechanisms reflect the complex interplay between cluster core, surface ligands, and environmental factors, and are still the subject of active research aimed at achieving better control and predictability of NC luminescence for targeted applications.

Traditionally, the synthesis of metal NCs has relied on wet chemical reduction methods [

15], where metal salts are reduced in the presence of protecting ligands under mild thermal conditions. While this classical approach is straightforward and adaptable to different ligands and metal precursors, it often suffers from long reaction times, limited control over cluster size and composition, poor reproducibility, and challenges in scaling up. As the demand for NCs in real-world applications grows, it becomes increasingly important to develop more efficient, reproducible, and scalable synthesis routes that preserve atomic precision while improving throughput and structural uniformity.

To address these challenges, this review focuses on emerging synthetic strategies, published in the last 5 years, that accelerate NC production and improve structural control. We discuss recent advances in microwave-assisted, photochemical, sonochemical, catalytically assisted, and smart synthesis approaches, each offering unique advantages in terms of speed, scalability, and structural precision. Beyond synthesis, we also highlight key applications where these newly developed NCs have demonstrated exceptional functionality. Specifically, we focus on their roles in fluorescence imaging, theranostics, chemical and biological sensing, and photocatalytic transformations. The aim of this review is to provide an integrated perspective that connects recent synthetic innovations with their functional outcomes, offering researchers a clear view of the current state and future potential of metallic NCs.

2. Novel Synthesis

The synthesis of metal NCs traditionally relies on solution-phase chemical reduction under mild conditions, often involving prolonged stirring and heating in the presence of stabilizing ligands [

16,

17]. This classical approach, typically carried out in aqueous or organic solvents without specific templating strategies, offers a simple and accessible route to NC formation. However, it suffers from several drawbacks, including long reaction times (ranging from hours to several days), limited size control, and poor reproducibility due to sensitivity to reaction conditions. Emerging methodologies such as microwave-assisted, photochemical, sonochemical, and catalysis-assisted syntheses have significantly reduced reaction times and enhanced uniformity. More recently, the concept of “smart synthesis” has gained traction, leveraging machine learning algorithms, automation, and robotic platforms to optimize reaction parameters and accelerate the discovery and design of NCs with tailored properties.

2.1. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis

Microwave-assisted synthesis has emerged as a powerful alternative to conventional heating methods for the preparation of metal NCs. In this approach, rapid volumetric heating generated by microwave radiation accelerates the reduction of metal precursors and promotes uniform nucleation and growth. This technique offers significant advantages over classical methods, including substantially reduced reaction time, improved reaction reproducibility, and enhanced control over cluster size and emission properties. Moreover, it is inherently compatible with green chemistry principles, often enabling aqueous-phase, ligand-assisted syntheses without the need for harsh reductants or elevated temperatures [

18].

Recent advances highlight the broad applicability of microwave-assisted synthesis for various metal NCs, including those based on gold (Au), silver (Ag) and copper (Cu). For instance, our group has explicitly demonstrated the effect of microwave-assisted synthesis on luminescence efficiency of histidine-stabilized AuNCs [

19]. We reported that NCs synthesized via microwave heating (850 W, 30 minutes –

Figure 1) exhibited fourfold higher photoluminescence than their counterparts obtained through classical, room-temperature protocols. The clusters showed a single blue emission band centered at 471 nm under 380 nm excitation, along with excellent photostability and stability over time. This study provided clear experimental evidence of the enhanced optical quality and consistency afforded by microwave synthesis. In another work, we also demonstrated that microwave-assisted synthesis enables fine control over the structure and emission of solid-state histidine-stabilized AuNCs [

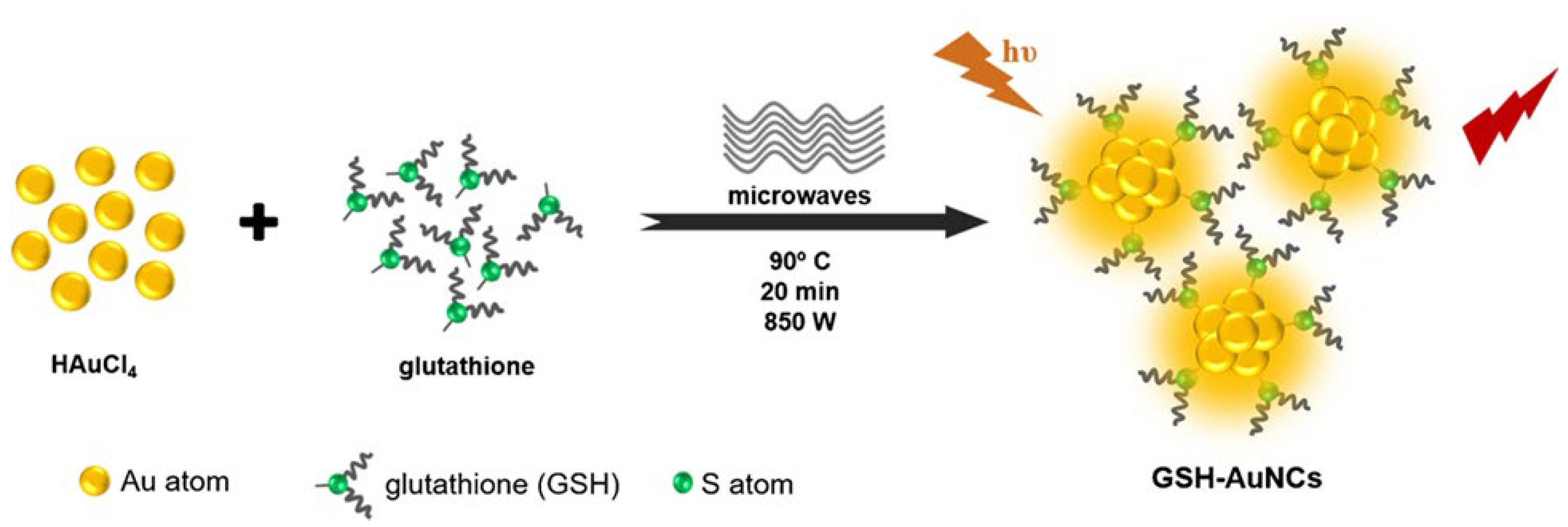

20]. We employed the same microwave-assisted protocol (850 W, 90 °C, 30 minutes) to synthesize colloidal histidine-stabilized AuNCs, which were subsequently lyophilized to obtain solid-state materials. These NCs exhibited dual emission at 475 nm and 520 nm depending on excitation wavelength (340–520 nm), along with average fluorescence lifetimes of 2–3 ns. Notably, the emission remained stable under continuous UV irradiation and was preserved up to 150 °C, reflecting both photostability and thermostability. The excitation-dependent dual emission and robust performance were attributed to enhanced core–ligand interactions and increased structural uniformity induced by microwave heating. In a related effort, our group also employed a rapid microwave-assisted synthesis of AuNCs using glutathione (GSH) as a stabilizing ligand [

21]. The reaction, conducted in sealed microwave vessels at 90 °C and 850 W for 20 minutes, yielded dual-emissive AuNCs with distinct photoluminescence peaks in the red (610 nm) and near-infrared (800–810 nm) regions.

The clusters could be excited over a broad spectral window (405–640 nm), with especially strong emission responses at the spectral edges. A high quantum yield of 9.9% was achieved, along with long fluorescence lifetimes, 407 ns in the red and up to 1821 ns in the NIR range, indicative of a well-passivated, rigid NC structure. These photophysical characteristics were directly enabled by the rapid and homogeneous reduction of Au precursors under microwave irradiation, further reinforcing the advantages of this method for producing structurally robust and optically tunable NCs.

Beyond gold-based systems, microwave-assisted protocols have also proven effective for other metals. A representative example is the work of Shang et al., who developed a rapid and environmentally friendly synthesis of AgNCs using L-histidine as both the reducing and stabilizing agent [

22]. Specifically, a mixture of AgNO₃ and histidine was subjected to microwave irradiation at 700 W for only eight minutes, resulting in the formation of Ag⁰-core NCs with surface-bound Ag⁺ coordinated to histidine. The clusters exhibited strong blue fluorescence with an emission peak at 440 nm upon 356 nm excitation, a quantum yield of 5.2%, and a multiexponential fluorescence decay with an average lifetime of 5.06 ns. The rapid formation, absence of harsh chemicals, and control over optical output were direct benefits of the microwave-assisted approach. This strategy has also been successfully extended to Cu-based systems, which present additional synthetic challenges due to their susceptibility to oxidation. In this context, Saleh et al. reported the microwave-assisted synthesis of pepsin-stabilized CuNCs by irradiating a basic aqueous solution of Cu(NO₃)₂ and pepsin at 850 W for 30 minutes [

23]. The obtained pepsin-stabilized CuNCs exhibited an uniform size of approximately 2 nm. These clusters emitted blue fluorescence with an emission maximum at 409 nm upon 360 nm excitation and exhibited an impressive quantum yield of 17%, one of the highest reported for aqueous CuNCs. The efficiency of the microwave-assisted approach in this case was attributed to rapid nucleation and controlled reduction, which helped mitigate oxidative degradation and produced stable, luminescent NCs.

In conclusion, microwave-assisted synthesis has demonstrated significant potential as a rapid, reproducible, and green route for the preparation of luminescent metal NCs. The microwave-assisted strategy exhibits broad applicability across Au, Ag, and Cu systems, with consistent improvements in reaction time, optical performance, and structural stability. By enabling efficient precursor reduction and uniform NC formation, microwave irradiation allows fine control over emission characteristics. These advantages underscore the value of microwave-assisted protocols as a modern alternative to classical synthesis.

2.2. Photochemical-Assisted Synthesis

Photochemical-assisted synthesis has emerged as a powerful method for producing metal NCs under mild, controllable, and environmentally friendly conditions. In contrast to conventional chemical reductions, photochemical strategies utilize light to drive redox transformations, enabling precise temporal control over nucleation and growth. This approach offers several advantages: it can bypass uncontrolled reduction kinetics, minimize the use of hazardous reagents, and in some cases, generate unique structural features or oxidation states that are difficult to achieve through thermal or chemical methods. The light-triggered mechanisms can operate via direct photoreduction, photoinduced electron transfer (PET), or radical-mediated redox cascades, depending on the metal system and ligand environment.

A representative example is the work of Wang et al., who synthesized atomically precise Ag₂₅ NCs using a PET mechanism under white LED irradiation [

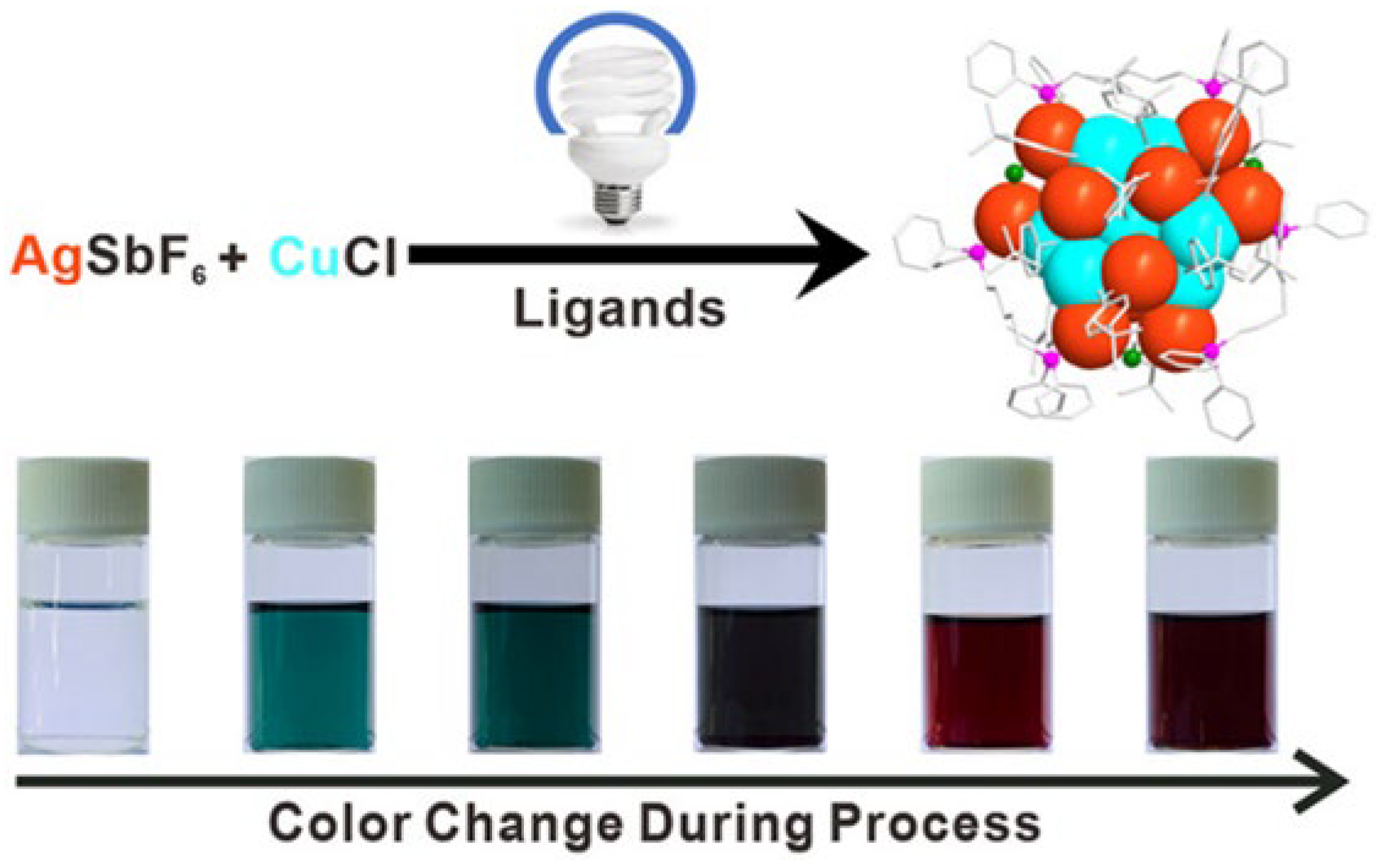

24]. Triethylamine acted as a sacrificial donor, transferring electrons to Ag⁺ to initiate cluster growth, with O₂ as the terminal oxidant. Notably, this method required no chemical reductants and allowed structural control comparable to that achieved using NaBH₄, but under greener, milder conditions. Building on this, the same group developed a stepwise synthesis of a bimetallic Ag₁₂Cu₇ cluster [

25]. Ag₁₉ was first photochemically generated, followed by CuCl addition under continued irradiation (

Figure 2).

This sequential reduction overcame redox incompatibility between Ag⁺ and Cu⁺ and enabled controlled alloying. The final cluster exhibited deep red phosphorescence (λem = 665 nm) with a 30 µs lifetime at room temperature, attributed to strong cuprophilic interactions and ligand-to-metal charge transfer.

Photochemical methods have also enabled access to well-defined group 10 metal NCs. Fan et al. synthesized for the first time nickel (Ni) and palladium (Pd) clusters via a redox cascade triggered by blue light [

26]. After NaBH₄ pre-reduction, irradiation generated thiyl radicals from disulfides, which stabilized metal aggregates into discrete ring-like structures such as Ni₁₁(SPh)₂₂. This approach succeeded where conventional reductions failed, offering better crystallinity, stability, and unique geometries. UV-Vis analysis revealed a characteristic absorption peak at 467 nm for Ni₁₁. In a sustainable chemistry context, Ferlazzo et al. reported a green photochemical synthesis of CuNCs in water using UV-activated acetone and monoethanolamine (MEA) as stabilizer [

27]. The resulting clusters (~3.5 nm) showed blue-green emission centered at 489.9 nm, a quantum yield of 12%, and excellent stability. They also exhibited photothermal behavior under 405 nm laser irradiation, with 38% conversion efficiency. The method avoided toxic solvents and reducing agents, emphasizing photochemistry’s role in green nanomaterials development. Therefore, photochemical-assisted synthesis provides a green and controllable route to metal NCs, enabling precise structural and optical tuning without harsh reductants. From noble to transition metals, this approach has proven effective across diverse systems, highlighting its growing importance in sustainable nanomaterial development.

2.3. Sonochemical-Assisted Synthesis

Sonochemical-assisted synthesis has emerged as a powerful technique for the fabrication of metal NCs, leveraging the physical and chemical effects of ultrasound to drive and control nucleation processes. When ultrasonic waves pass through liquid media, they generate acoustic cavitation, rapid formation and implosion of microbubbles, which produces localized hotspots with extreme temperature and pressure gradients. These transient conditions enhance mixing, accelerate reduction reactions, and promote uniform nucleation, often leading to the formation of smaller, more monodisperse clusters compared to conventional synthesis [

28]. Furthermore, sonochemical processes can activate surfaces, assist ligand integration, and improve metal-support interactions.

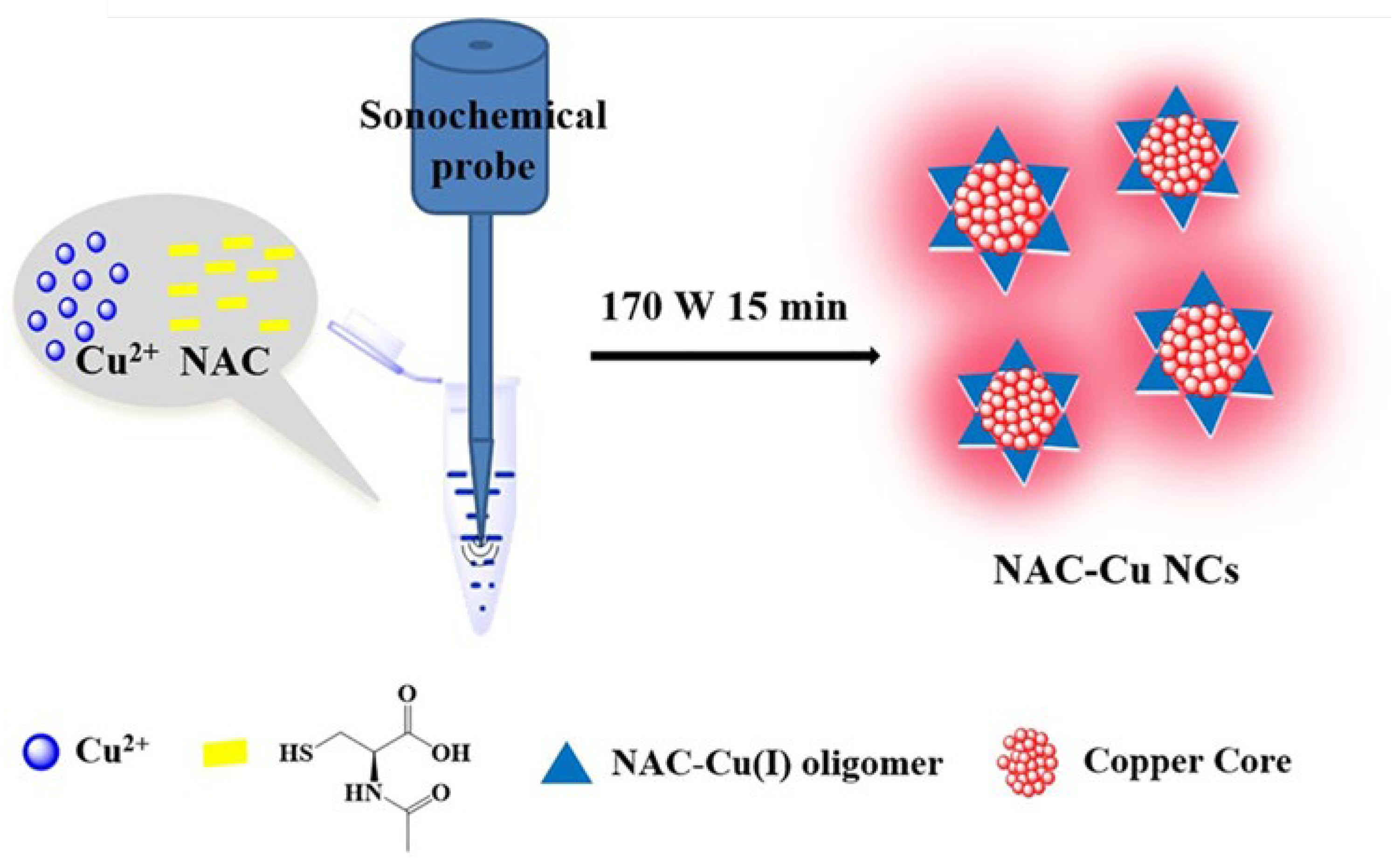

A clear demonstration of these advantages is provided by Kang et al., who synthesized red-emissive CuNCs stabilized by N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) using a 15-minute ultrasound-assisted method in water, without any external reducing agents (

Figure 3) [

29].

The process involved Cu²⁺ reduction to Cu⁺ and subsequent ultrasound-driven reduction to Cu⁰, resulting in ultrasmall clusters (~1.2 nm core size) with a red emission peak at 630 nm and a large Stokes shift of 290 nm. Compared to conventional thermal synthesis (12 h at 70 °C), the sonochemical approach produced brighter, more photostable NCs that remained stable over months. This synthesis strategy offered not only speed and simplicity but also enabled efficient integration of the NAC ligand, which functioned dually as reductant and stabilizer. The resulting NCs showed high fluorescence lifetime (451 ns average) and excellent thermal and colloidal stability, confirming the effectiveness of ultrasound in driving clean, green synthesis with enhanced optical properties. Beyond Cu-based systems, sonochemical methods have also been employed to precisely control the nucleation and growth of transition metal NCs. Liu et al. developed an ultrasound-assisted route to synthesize nickel NCs supported on Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene, where ultrasonic irradiation played a dual role in promoting MXene exfoliation and enabling uniform NiNC formation [

30]. Compared to non-sonicated controls, the ultrasound-treated catalysts exhibited higher dispersion, smaller particle sizes, and a sixfold increase in turnover frequency (302 h⁻¹). The synergy between ultrasound-induced surface activation and enhanced nucleation yielded electron-rich, catalytically active NiNCs with excellent stability. In summary, sonochemical-assisted synthesis offers a rapid, scalable, and environmentally friendly approach for producing well-defined metal NCs. By exploiting the localized energy of acoustic cavitation, this method enables precise control over nucleation, particle size, and ligand incorporation. Its versatility across different metal systems highlights its growing relevance in the development of high-performance nanomaterials under mild and sustainable conditions.

2.4. Catalytic-Assisted Synthesis

Catalytically assisted synthesis has recently emerged as a promising approach for generating atomically precise metal NCs under mild and selective conditions. Unlike traditional chemical reduction methods, catalytic systems can activate molecular hydrogen or other reductants to drive controlled metal ion reduction. These methods leverage well-established catalytic principles, such as hydrogen activation, proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET), and surface-mediated reactions, to facilitate NC formation in a tunable and potentially scalable manner. By integrating heterogeneous catalysts into NC synthesis, this strategy also opens the door for cleaner, recyclable, and industrially relevant processes.

A recent study by Wang et al. demonstrated the first heterogeneous catalytic synthesis of an atomically precise Au₁₃ NC using commercial Pd/C and molecular hydrogen [

31]. The Au precursor, (CH₃)₂SAuCl, was reduced in ethanol under 0.1 MPa H₂ at room temperature, in the presence of thiol (TBBT), phosphine (Dppe) ligands, and a base (Et₃N). The resulting cluster, PPh₄[Au₁₃(TBBT)₄(Dppe)₄]Br₂, featured a centered icosahedral Au₁₃ core stabilized by a mixed ligand shell and confirmed via single-crystal XRD. Control reactions showed that neither heat nor H₂ alone could drive the transformation, Pd/C was essential to activate H₂ and initiate reduction. Mechanistically, Pd–H species facilitated PCET to reduce Au(I), with Et₃N lowering the energy barrier, as supported by DFT studies. The synthesis produced no aggregation, and the Pd/C catalyst was recoverable, highlighting the process’s selectivity and practicality. This work establishes catalytic hydrogenation as a viable, sustainable pathway for NC synthesis. By merging principles from heterogeneous catalysis and nanochemistry, it opens new possibilities for precise cluster construction under ambient and scalable conditions.

2.5. Smart Synthesis

Smart synthesis represents a next-generation strategy for preparing metal NCs, characterized by the integration of automation, intelligent feedback systems, and data-driven control over reaction variables. Unlike conventional methods, smart synthesis incorporates real-time monitoring, machine learning (ML), robotic systems, and high-throughput experimentation to optimize cluster formation with unprecedented precision [

32]. This approach addresses long-standing challenges in NC synthesis, such as low reproducibility, sensitivity to minor changes in reaction conditions, and difficulty in navigating multidimensional parameter spaces, by enabling dynamic, adaptive control and autonomous decision-making.

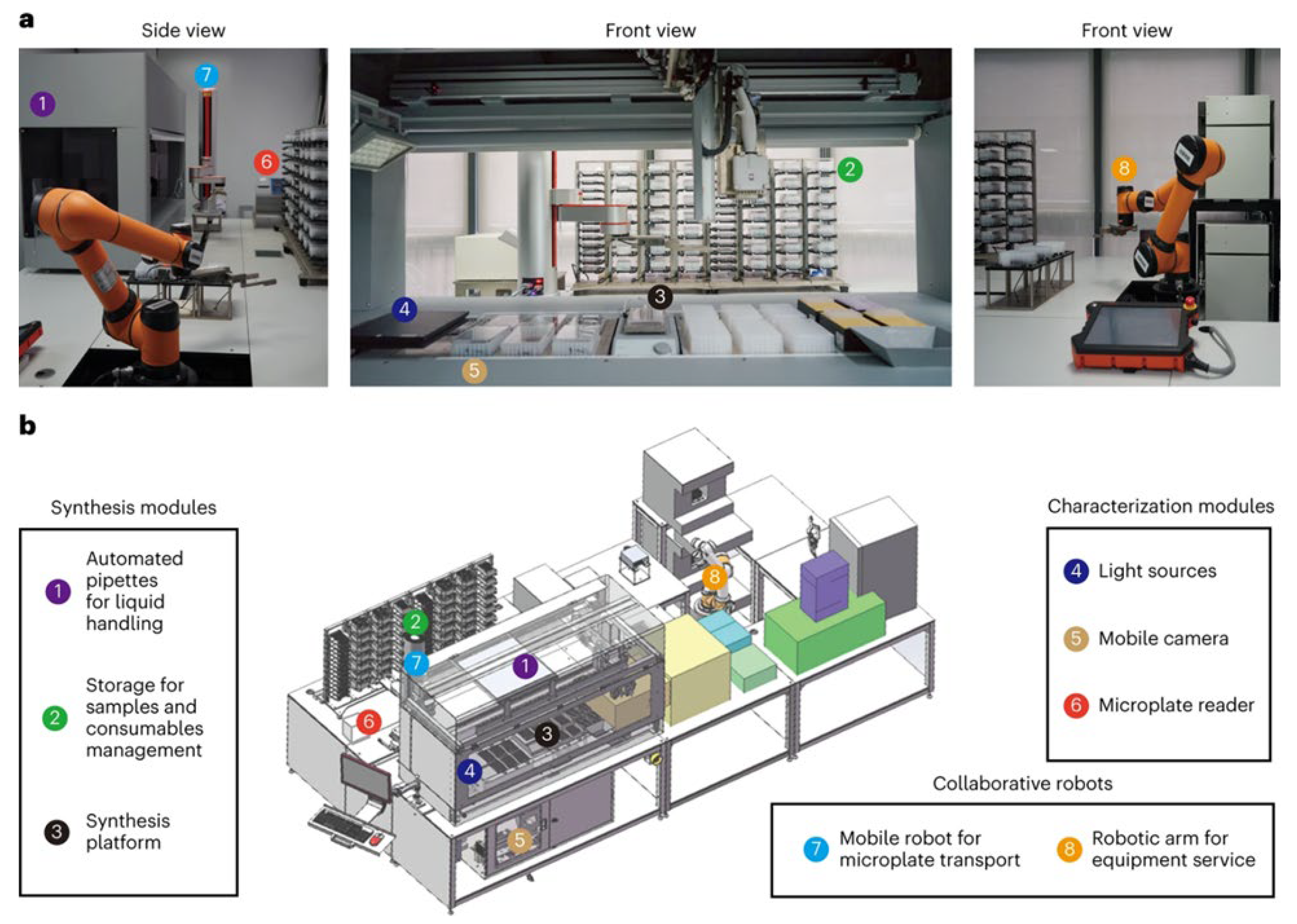

Recently, a self-driving robotic workstation [

33,

34,

35], guided by a closed-loop optimization algorithm, can be employed to synthesize nanocrystals. The robot autonomously adjusted parameters such as stirring speed and precursor concentration based on feedback from real-time UV–vis absorption and fluorescence spectra, rapidly converging on optimal conditions (

Figure 4).

Moreover, ML-assisted reaction optimization has been used to tune ligand–metal ratios, pH, temperature, and reducing agent strength in real time, leading to the efficient identification of conditions that yield atomically precise clusters [

36,

37]. Importantly, smart synthesis not only accelerates discovery but also enhances reproducibility by minimizing human intervention. It facilitates the exploration of vast compositional and kinetic spaces that are often inaccessible through manual methods. While still in its early stages, the convergence of chemistry with robotics, data science, and artificial intelligence promises to redefine how NCs are discovered and manufactured. As these technologies mature, smart synthesis is expected to shift NC preparation from artisanal practice to programmable science, enabling scalable, reproducible, and application-specific design of NCs.

Taken together, these emerging methodologies demonstrate how alternative energy inputs and catalytic principles can overcome the limitations of conventional chemical reduction, offering faster, greener, and more reproducible access to metallic NCs. While the choice of synthesis route is essential for improving efficiency, scalability, and uniformity, it is the ligand chemistry and cluster size that remain the dominant factors in defining photoluminescence properties and functional performance. To provide a consolidated view of these advances, a summary of representative NCs synthesized via microwave-, photochemical-, sonochemical-, catalytically assisted, and smart approaches is presented in

Table 1.

3. Applications

3.1. Fluorescence Imaging

Metal NCs have emerged as highly promising fluorescent probes for bioimaging due to their ultra-small size, high photostability, tunable emission, and excellent biocompatibility [

38]. Their discrete electronic states and strong ligand–metal interactions enable bright and stable luminescence, making them attractive candidates for applications where traditional organic dyes or quantum dots fall short. Although fluorescent NCs have been developed across the visible to near-infrared (NIR) spectrum, this subchapter focuses on those emitting in the NIR region. Compared to visible-emitting agents, NIR-emitting NCs offer deeper tissue penetration, reduced background autofluorescence, and improved signal-to-noise ratios, all of which are critical for high-resolution imaging in biological environments [

39]. Moreover, their compatibility with clinically relevant optical windows makes NIR-emitting NCs particularly attractive for translation into medical imaging applications. To highlight the versatility and translational potential of NCs, we examine their application across different biological settings, ranging from cellular models to tissue-level imaging and whole-organism studies. Accordingly, the following sections are organized into in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo investigations, reflecting the increasing complexity and physiological relevance of each approach.

3.1.1. In vitro Fluorescence Imaging

In vitro imaging studies serve as the foundational step in evaluating the bioimaging potential of NCs, enabling controlled investigation of their behavior in cellular environments. These experiments are critical for assessing cellular uptake, intracellular localization, cytotoxicity, and fluorescence performance under biologically relevant conditions. Moreover, when NCs are functionalized with targeting ligands, such as peptides, antibodies, aptamers or small molecules, they can selectively bind to specific cell types, allowing precise visualization of pathological versus healthy cells. This makes in vitro imaging especially powerful for validating targeted NC designs, optimizing ligand–receptor interactions, and establishing molecular specificity before translation to tissue or whole-organism models.

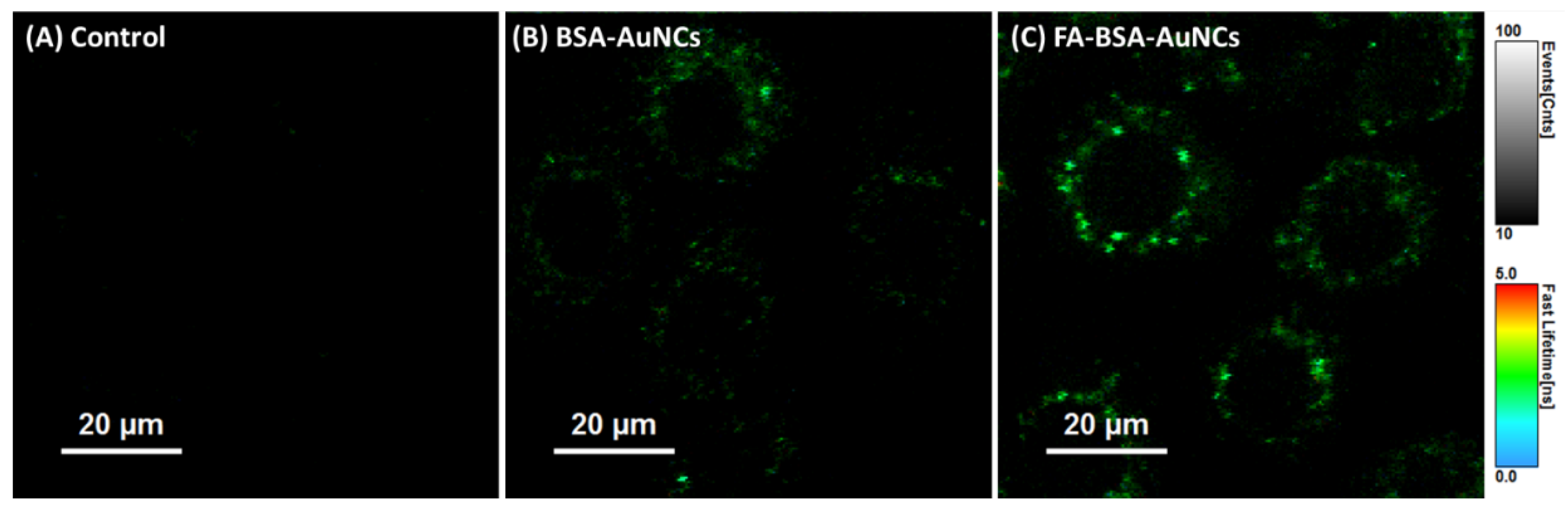

One illustrative example was reported by our group and involves the use of folic acid (FA)-functionalized bovine serum albumin (BSA) stabilized AuNCs for targeted imaging of ovarian cancer cells [

21]. These NCs, emitting at 670 nm under 530 nm excitation, were designed to exploit the overexpression of folate receptor alpha (FRα) on NIH:OVCAR-3 cells. FA was covalently linked to the surface of the BSA-AuNCs using EDC/NHS chemistry (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide/ N-hydroxysuccinimide), resulting in a measurable increase in hydrodynamic size and zeta potential shift, confirming successful conjugation. Epi-fluorescence microscopy revealed intense cytoplasmic accumulation in FRα-positive cells, while confocal fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) demonstrated enhanced contrast and lifetime-based discrimination from background autofluorescence (

Figure 5).

Notably, the functionalized NCs showed stronger internalization and perinuclear accumulation compared to their non-targeted counterparts, without causing cytotoxic effects at high concentrations. Another approach to achieve cell specificity was demonstrated by Feng et. al., who developed thiolated MUC1 aptamer-stabilized AuNCs, where the DNA aptamer served simultaneously as a stabilizer and a recognition ligand [

41]. The resulting NCs, measuring ~1.5 nm in diameter, exhibited strong red fluorescence at 655 nm under 420 nm excitation and a remarkably long fluorescence lifetime of 5.6 μs. Targeting specificity was validated by incubating the NCs with MUC1-positive 4T1 breast cancer cells and MUC1-negative 293T kidney cells. Only the 4T1 cells displayed bright cytoplasmic fluorescence, with signal intensity increasing over time. Lifetime imaging also confirmed that photoluminescence originated from specific interactions within the targeted cancer cells, rather than from passive or nonspecific uptake. This result highlights the strong selectivity of the aptamer-guided NCs for imaging MUC1-expressing tumor cells. Extending the range of targeting mechanisms, Tan et al. reported the synthesis of spider venom–derived peptide-stabilized AuNCs (LGNCs) using lycosin-I, an amphiphilic and cationic peptide known for its tumor-penetrating capabilities [

42]. These LGNCs displayed NIR emission at 682 nm upon 347 nm excitation, with a quantum yield of 9.1% and an average fluorescence lifetime of 2.1 μs. Upon incubation with cancer cells (4T1 and A549), confocal microscopy revealed a two-stage process: initial cytoplasmic localization followed by gradual nuclear translocation over 8 hours. This behavior was driven by intracellular glutathione (GSH), which triggered the disassembly of peptide-induced aggregates into ultrasmall clusters, facilitating nuclear entry. Uptake was highly selective for cancer cells, with >94% internalization in 4T1 cells and negligible uptake in non-cancerous Hek293t cells, as confirmed by flow cytometry and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) quantification.

These studies collectively highlight the versatility of NCs in achieving selective cellular imaging through rational surface functionalization. By employing diverse targeting strategies, from small molecules and aptamers to bioactive peptides, precise discrimination between cancerous and non-cancerous cells was achieved. The ability to tailor emission wavelengths, enhance photostability, and exploit long fluorescence lifetimes further positions NCs as powerful tools for high-contrast, background-free imaging at the cellular level. Such in vitro investigations lay a critical foundation for advancing targeted NC systems toward more complex biological applications.

3.1.2. Ex vivo Fluorescence Imaging

Ex vivo imaging serves as an essential intermediate step between in vitro validation and in vivo translation, offering a more realistic assessment of NC performance in complex tissue environments. This approach allows for detailed evaluation of tissue penetration, signal retention, and contrast enhancement under near-physiological conditions. Importantly, ex vivo studies can also be conducted using artificial tissue-mimicking phantoms, providing a safe and reproducible platform to optimize imaging parameters and assess depth-resolved fluorescence performance before proceeding to animal models.

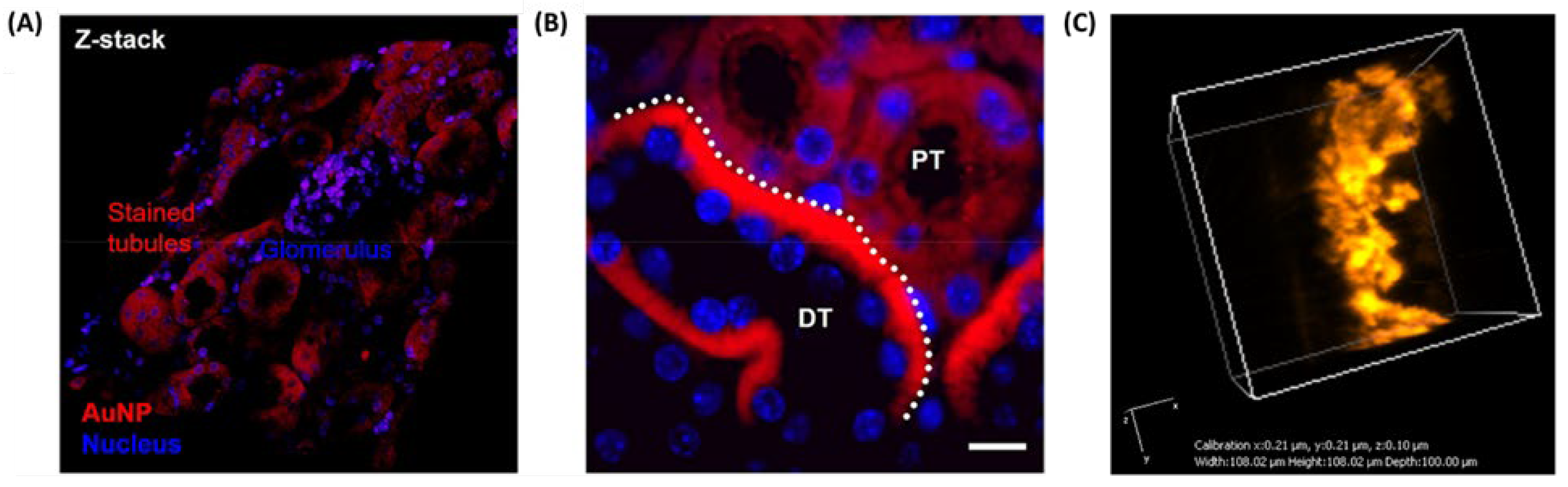

A notable example of selective localization in real tissue slices was demonstrated by Peng et al., who introduced an in situ ligand-directed synthesis approach for growing AuNCs directly within tissue sections [

43]. Using biological ligands such as glutathione (GSH) or β-glucose-SH, Au precursors were selectively reduced within specific compartments of mouse kidney, brain, and intestinal tissue slices. This method led to ultrasmall, NIR-luminescent clusters during the early formation phase, with emission peaks at 730 and 800 nm under 350 nm excitation. Targeted accumulation was guided by natural ligand-tissue affinity, GSH promoted mitochondrial labeling in renal and neuronal regions, while β-glucose enabled selective labeling of the intestinal brush border (

Figure 6A-B). Confocal microscopy, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and whole-tissue NIR imaging confirmed the high spatial precision and multiscale imaging capability, establishing this method as a powerful histological mapping tool.

Complementing real tissue imaging, our group have demonstrated the utility of synthetic tissue-mimicking phantoms for evaluating NCs prior to in vivo application. These phantoms, composed of agarose, intralipid, and hemoglobin, replicate the scattering and absorption characteristics of biological tissues and serve as platforms for optimizing contrast agents. For instance, our group investigated the photophysical performance of BSA-stabilized AuNCs (BSA-AuNCs) in both solid-state form and in phantom matrices designed to simulate tumor-like optical properties [

45]. The NCs were incorporated into agarose-based phantoms doped with intralipid and hemoglobin to mimic biological scattering and absorption. Under two-photon excitation fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (TPE–FLIM) at 810 nm, the NC-containing phantoms exhibited strong, homogeneous fluorescence and lifetime profiles that remained well-separated from background autofluorescence. These results validated the stability and imaging capacity of BSA-AuNCs in three-dimensional, tissue-like environments. Building on this, a second study from our group optimized the embedding concentration and imaging depth using colloidal BSA-AuNCs dispersed in similar phantom matrices [

46]. By varying the volume fraction of NCs and performing TPE–FLIM at excitation wavelengths between 780 and 820 nm, we identified the optimal loading, yielding bright NIR emission without aggregation (

Figure 6D). Quadratic power dependence of the emission confirmed genuine two-photon excitation, while the lifetime mapping showed high contrast against the phantom background. Notably, imaging at 820 nm provided slightly higher signal intensity, reinforcing its suitability for deep-tissue and surgical guidance applications using BSA-AuNCs as contrast agents. Expanding on this, our group explored the embedding of dual-emissive GSH-AuNCs within phantoms to exploit both red (610 nm) and NIR (800 nm) emission channels for flexible imaging strategies [

21]. These NCs, synthesized via a microwave-assisted method, displayed exceptionally long fluorescence lifetimes up to 1.8 μs, This is a significant advantage for FLIM because it provides a clear contrast against the much shorter lifetimes (typically nanoseconds) of native biological fluorophores and tissue autofluorescence. This distinct temporal separation allows for selective imaging of the NCs, making them highly effective as FLIM contrast agents for detailed biological studies. Re-scan confocal microscopy (RCM) and FLIM confirmed their even distribution throughout the phantom and excellent signal separation from background autofluorescence (

Figure 6C), which typically has lifetimes under 4 ns. This demonstrated the value of dual-mode (spectral and lifetime) contrast for tissue-relevant imaging platforms.

These findings highlight the suitability of metal NCs as powerful contrast agents for ex vivo fluorescence imaging. Their stable photoluminescence, tunable emission in the NIR region, and long fluorescence lifetimes enable high-contrast, background-free visualization in both real tissues and synthetic phantoms. Whether grown in situ within biological slices or embedded into scattering tissue models, NCs retain their optical integrity and targeting precision, making them ideal tools for optimizing imaging parameters and validating probe performance ahead of in vivo deployment.

3.1.3. In vivo Fluorescence Imaging

In vivo imaging represents the ultimate test for evaluating the real-world applicability of NCs as bioimaging agents, requiring stability, biocompatibility, deep-tissue penetration, and precise signal detection within living organisms. While early studies largely focused on visible and NIR-I emitting NCs, recent efforts have shifted toward developing probes that operate in the second near-infrared window (NIR-II, 1000–1700 nm). This spectral range offers clear advantages for biomedical imaging, including reduced tissue scattering, lower autofluorescence, and deeper penetration depths. These features collectively enhance spatial resolution and signal-to-background ratios, making NIR-II NCs particularly attractive for non-invasive diagnostics and image-guided interventions.

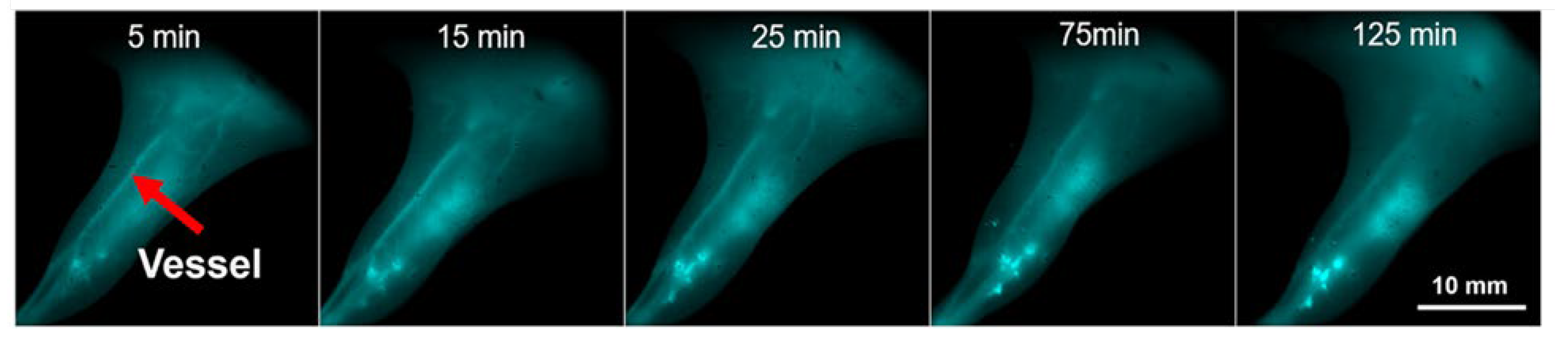

One of the pioneering approaches was reported by Song et al., who introduced cyclodextrin-protected AuNCs (CD-AuNCs) for antibody-guided NIR-II imaging of MCF-7 breast tumors [

47]. With a compact core size of 1.85 nm and emission centered at 1050 nm, these NCs leveraged host–guest supramolecular chemistry for conjugation with anti-CD326 antibodies. The resulting Ab@AuNCs achieved ~12% ID tumor accumulation, approximately 4× higher than untargeted controls, and provided a threefold increase in imaging contrast at tissue depths up to 9 mm, outperforming conventional NIR-I agents. Notably, these ultrasmall NCs exhibited rapid renal clearance (>75% ID in 24 h) with no off-target toxicity, setting a benchmark for clinical translation. Adding subcellular precision to tumor imaging, Nie et al. engineered DNA-aptamer stabilized AuNCs with programmable valence to direct intracellular distribution in 4T1 breast cancer models [

48]. These ultrasmall clusters emitted at 1030 nm and were functionalized with 1–4 AS1411 aptamers, controlling uptake into nuclei (V1–V2) or membrane retention (V4). Tumor accumulation increased with valence (up to 2.88% ID/g), and clearance remained efficient. The study introduced a unique strategy to fine-tune NC by discrete valence engineering without the need for post-synthetic modification.

Beyond oncology, Zhao et al. introduced TPPTS-capped ultrasmall AuNCs for non-invasive detection of early-stage kidney injury [

49]. These clusters remained non-emissive until activated by intracellular glutathione (GSH) via in situ ligand exchange, triggering NIR-II emission at ~1026 nm. This biomarker-free activation strategy produced high imaging contrast in inflamed renal tissue with minimal background signal and clear accumulation in renal tubular epithelium. Imaging lasted >6 h post-injection and significantly outperformed always-on analogs, offering a new platform for activatable disease diagnostics. For high-resolution vascular imaging, Guo et al. synthesized Cd-doped dual-ligand Au7Cd1 NCs using MHA/MPA stabilization [

50]. These bright, photostable emitted in the NIR-II window (~1050 nm) and showed strong renal clearance, peaking in the bladder at ~90 min. Using InGaAs-based NIR-II fluorescence imaging, they visualized cerebral, hindlimb, and spinal vasculature in C57BL/6 mice, resolving vessels as small as 0.4 mm (

Figure 7) with high signal to noise ratio (as high as 11).

Their stability in serum and long imaging window (>270 min) highlight their suitability for real-time angiographic monitoring. Finally, Liu et al. explored the utility of Au25(SG)18 NCs in 3D volumetric imaging using Airy beam-assisted NIR-II light-sheet microscopy [

51]. These glutathione-stabilized clusters emitted in both NIR-I and NIR-II windows (850–950 nm and 1150–1400 nm, respectively) and were employed to visualize ex vivo brain, thymus, spleen, and intestines in radiation-injured mice. Imaging with an 808 nm or 730 nm excitation source enabled deep-tissue penetration (~2.5 mm) and improved axial resolution (3.5 µm) across wide fields of view (~600 µm). This study demonstrated that AuNCs can serve as effective volumetric imaging agents for mapping radiation-induced damage, with minimal photobleaching and enhanced contrast using Airy beam illumination.

Together, these studies highlight the remarkable versatility of NIR-II-emitting AuNCs across diverse in vivo imaging applications, from tumor targeting and subcellular localization to kidney diagnostics, vascular mapping, and deep-tissue volumetric imaging. Their tunable surface chemistry, compact size, and high renal clearance efficiency position them as strong candidates for safe, high-contrast bioimaging. Moreover, the ability to engineer emission activation, dual-modal readouts, and precise targeting strategies underscores their adaptability for complex biological environments. Looking ahead, the continued refinement of surface ligands for enhanced biocompatibility, the integration of multifunctional payloads for theranostics, and the development of scalable, reproducible synthesis routes will be essential for bridging the gap between preclinical success and clinical translation. With growing interest in minimally invasive diagnostics and image-guided interventions, NIR-II NCs are poised to play a transformative role in next-generation biomedical imaging platforms.

The studies discussed in the fluorescence imaging section illustrate the versatility of metallic NCs as imaging probes across in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo models, highlighting their tunable emission, biocompatibility, and capacity for targeted visualization. To consolidate these findings and provide a comparative perspective,

Table 2 summarizes representative examples of NCs employed for fluorescence imaging in different biological settings.

3.2. Theranostics

While high-resolution NIR imaging provides powerful insight into the localization and behavior of disease at the molecular and tissue level, the next logical step is to integrate diagnostic precision with therapeutic intervention. This is the foundation of theranostics, an approach that leverages NCs not only as imaging probes but also as functional platforms for targeted therapy. By uniting real-time visualization with treatment delivery, theranostic NCs enable precise spatiotemporal control over therapeutic actions, minimize off-target effects, and allow for dynamic monitoring of treatment efficacy [

38]. Recent developments have focused on combining NIR imaging with photodynamic therapy, radiotherapy sensitization, or drug delivery, establishing NCs as versatile tools in personalized medicine.

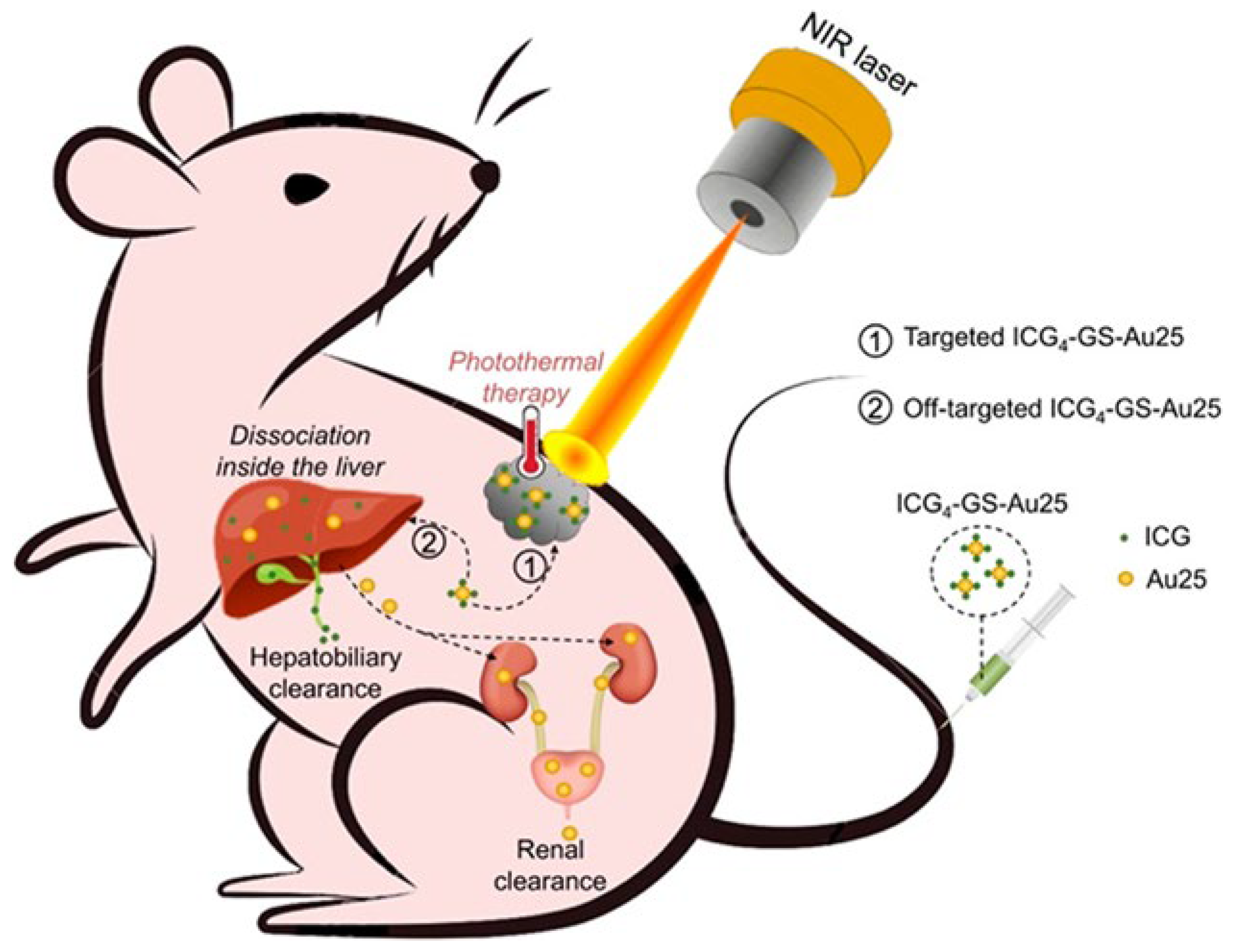

A landmark example is the use of 4 indocyanine green-conjugated Au25 NCs (ICG4–GS-Au25) for fluorescence-guided photothermal therapy in mouse breast cancer cells (TUBO) [

52]. Jiang et al. engineered this construct by conjugating ICG molecules per ultrasmall Au25 cluster. Fluorescence was quenched in the native state and restored intracellularly via thiol-triggered release, enabling imaging of tumor uptake and liver biotransformation. Upon 808 nm laser irradiation, the constructs achieved localized heating (~55 °C) and complete tumor ablation with high photothermal conversion and minimal systemic toxicity (

Figure 8).

The dual-clearance mechanism, renal for AuNCs and hepatobiliary for ICG, addressed long-standing biocompatibility concerns for clinical translation. Kong et al. proposed a cost-effective theranostic alternative by co-loading Neutral Red (NR) into Min-23 peptide-stabilized AuNCs, enabling smartphone-triggered PDT in 4T1 breast cancer [

53]. These ultrasmall NR@Min-23@AuNCs emitted in the NIR-II region (~1050 nm), accumulated passively via the EPR effect, and upon low-power light activation (8 mW/cm²), generated ROS that led to 90% tumor inhibition. Their high renal clearance efficiency (~80% in 48 h) and ease of activation suggest practical potential for use in low-resource clinical settings. Extending this logic into gene therapy, Wang et al. employed in situ biosynthesized AuNCs–PTEN complexes for treatment of orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [

54]. Upon intravenous co-administration of Au precursors and PTEN DNA, NCs self-assembled at the tumor site under reductive conditions, achieving simultaneous fluorescence-based tumor localization and functional gene delivery. The GNC–PTEN complex not only suppressed tumor growth more effectively than free PTEN or NCs alone, but also maintained minimal off-target accumulation, enhancing its therapeutic precision in a clinically relevant liver cancer model.

For rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Yang et al. introduced phosphorylated Au44MBA26 NCs (MBA denotes 4- mercaptobenzoic acid) that combined bone-specific NIR-II imaging (1080/1280 nm) with anti-inflammatory therapy in collagen-induced arthritis rat models [

55]. Accumulating selectively in bone via phosphate-hydroxyapatite affinity, these NCs suppressed key inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) and modulated the NF-κB pathway, outperforming methotrexate in reducing joint inflammation and restoring bone integrity. Their dual-peak NIR-II emission, good biocompatibility, and renal clearance highlight their translational potential for skeletal disorders. The versatility of NCs was further illustrated by Ag@PEG2000-HA NCs (PEG refers to polyethylene glycol, while HA refers to hyaluronic acid), designed for dual-targeted tumor imaging and ROS-mediated therapy [

56]. In a 4T1 breast tumor mouse model, HA enabled active targeting via CD44 receptors, while silver ions disrupted mitochondrial function to induce apoptosis. With NIR emission between 620–800 nm and a tumor contrast index >2.5, these NCs suppressed angiogenesis, metastasis, and tumor proliferation. Notably, the platform achieved high selectivity and minimal off-target effects, marking it as a potent multimodal agent for tumor suppression. In a complementary direction, Zhao et al. developed dual-mode Au–Gd NCs combining NIR-II fluorescence and MRI contrast for glioma imaging and radiotherapy sensitization [

57]. Synthesized via albumin-mediated biomineralization and further functionalized with DTPA–Gd³⁺, these clusters showed strong NIR-II emission and high r₁ relaxivity (22.6 s⁻¹·mM⁻¹), far exceeding that of clinical Gd-based agents. In vivo, they enabled precise tumor localization in C6 glioma-bearing mice, and when combined with 8 Gy X-ray, led to tripled survival and significant tumor regression. Their dual renal-hepatic clearance and excellent biocompatibility positioned them as promising agents for image-guided radiotherapy

Lastly, a computational study by Abd El-Mageed et al. proposed AuNCs as nanocarriers for the anticancer drug D-penicillamine (DPA) [

58]. Using DFT and molecular dynamics simulations, the authors demonstrated stable binding through polar covalent and hydrogen-bond interactions and feasible drug release in aqueous media. Although theoretical, this study offers foundational insights for rational nanocarrier design using atomically defined clusters. Therefore, NCs exhibit a vast potential as next-generation theranostic agents. Their tunable size, surface chemistry, and optical properties, especially in the NIR window, allow for precise integration of imaging and therapy across a spectrum of diseases, from solid tumors to inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis. Whether through photothermal ablation, photodynamic activation, gene delivery, or ROS-mediated mechanisms, NC platforms consistently demonstrate effective treatment outcomes with minimal systemic toxicity and efficient clearance. To provide a consolidated view of these advances,

Table 3 summarizes representative NCs systems employed in theranostic applications.

Looking forward, the clinical translation of NC-based theranostics will rely on continued improvements in synthetic reproducibility, biocompatibility, and large-scale manufacturing. Equally important is the development of activatable or environment-responsive platforms, enabling on-demand therapy while minimizing off-target effects. With their ability to unify diagnosis, treatment, and real-time monitoring in a single platform, NCs are poised to play a central role in the advancement of precision medicine and non-invasive image-guided therapies.

3.3. Sensing

The unique physicochemical properties of metal NCs make them highly attractive also for chemical and biological sensing. Their discrete energy states allow for bright photoluminescence, while their surface chemistry can be engineered to selectively interact with a wide range of analytes. As a result, NCs have emerged as versatile probes capable of converting molecular recognition events into measurable optical signals [

59,

60]. Among the most explored applications is the detection of ions, where NCs serve as both recognition elements and signal transducers. Their fluorescence is often modulated through direct coordination, redox interactions, or aggregation effects upon ion binding, enabling sensitive and selective quantification of biologically and environmentally relevant species. Beyond ions, NCs have also proven effective for sensing small molecules by leveraging tailored surface ligands or catalytic activities that induce measurable changes in their optical response. In recent years, attention has expanded toward pathogen detection, where NCs are increasingly used in combination with biomolecular recognition elements such as aptamers, antibodies, or nucleic acid sequences. These platforms exploit the signal amplification potential and biocompatibility of NCs to achieve high sensitivity in detecting bacteria, viruses, or pathogen-derived markers. In the following section, we will explore representative sensing applications of NCs, beginning with ion detection, then small molecules, and finally pathogen-related targets, highlighting both the detection mechanisms and innovations that contribute to their selectivity, sensitivity, and real-world applicability.

3.3.1. Ion Detection

Metal NCs have emerged as powerful tools for ultrasensitive ion detection, owing to their tunable fluorescence and ease of functionalization. Their ability to detect metal ions through photoluminescence quenching or enhancement mechanisms makes them ideal for environmental monitoring and biomedical diagnostics. In this section, we present recent advances in NC-based ion sensors, beginning with systems targeting a single analyte, moving to multiplexed platforms, and concluding with innovative paper-based sensors suitable for naked-eye or smartphone-assisted detection.

Among single-ion detection systems, Zhao et al. developed glutathione-stabilized AuNCs (GSH-AuNCs) emitting at 500 nm for selective cobalt detection [

61]. The key innovation lies in pH-tuned fluorescence quenching: at pH 6.0, only Co²⁺ disrupts the Au–S interface via static quenching, enabling high specificity even in the presence of Cu²⁺ or other interfering ions. The sensor showed a linear range of 2.0–50.0 μM with a detection limit of 0.124 μM and was successfully validated on environmental water samples with recovery between 102.8% and 108.3%. The probe demonstrated high reproducibility (RSD <0.4%) and visible fluorescence response under UV light. A different ion-specific system was proposed by Singh et al., who fabricated BSA-stabilized CuNCs for Fe³⁺ detection [

62]. The probe, emitting blue fluorescence at 405 nm, relies on static quenching and inner filter effect (IFE) upon Fe³⁺ binding, without significant lifetime changes. It achieved a low LOD of 10 nM over a 0.2–2.4 μM range and was tested in natural water, wastewater, and human serum, with recoveries of 93–104% and relative standard deviations (RSDs) below 5.8%. The sensor’s high sensitivity and biocompatibility make it promising for clinical and environmental use. Furthermore, Zhang et al. introduced a thiol-functionalized CuNC probe for Ag⁺ sensing based on aggregation-induced quenching [

63]. These MMI-capped CuNCs emitted at 476 nm with a lifetime of 10.57 µs, and upon Ag⁺ binding, formed aggregates that reduced fluorescence through static quenching. The sensor achieved a LOD of 6.7 nM within a 0.025–50 µM range and exhibited excellent selectivity against numerous metal ions. Tested in human blood serum, the sensor delivered recoveries of 97–104% (RSD <3.6%). The authors also demonstrated the material’s multifunctionality for anticounterfeiting and LED applications, showcasing its high stability and practical versatility.

In terms of multi-ion detection, Desai et. al. developed AuNCs from Curcuma longa extract capable of independently sensing Cd²⁺, Zn²⁺, and Cu²⁺ ions [

64]. The green-emitting AuNCs (emission at 619 nm) showed distinct detection mechanisms: fluorescence enhancement for Cd²⁺/Zn²⁺ and fluorescence quenching for Cu²⁺. They achieved nanomolar sensitivity (LOD: Cd²⁺ = 12 nM, Zn²⁺ = 16 nM, Cu²⁺ = 26 nM), with linear ranges of 10 nM–10 μM. Tested in biological and various digested food samples, they showed recovery between 87–103%. Another multi-ion detection platform was reported by Saleh et al., who used coffee extract-mediated AuNCs for Cu²⁺ and Hg²⁺ detection [

65]. These bright green-emitting NCs (507 nm emission) relied on different quenching pathways: Cu²⁺ induced chelation with functional groups, while Hg²⁺ interacted with surface Au⁺. Detection was made selective through masking agents: NaBH₄ for Hg²⁺ and EDTA for Cu²⁺. The system achieved LODs of 14.78 nM for Cu²⁺ and 35.21 nM for Hg²⁺, with excellent selectivity and reproducibility over four cycles. Applied to tap water, both ions were accurately detected with recoveries above 96% and RSD <1.6%.

Among the most accessible and user-friendly platforms for ion sensing are paper-based NC sensors, which enable visual detection and smartphone-assisted quantification without the need for specialized equipment. A practical approach first explored by our group employed BSA-stabilized AuNCs (BSA-AuNCs) emitting at 670 nm for the detection of Cu²⁺ ions [

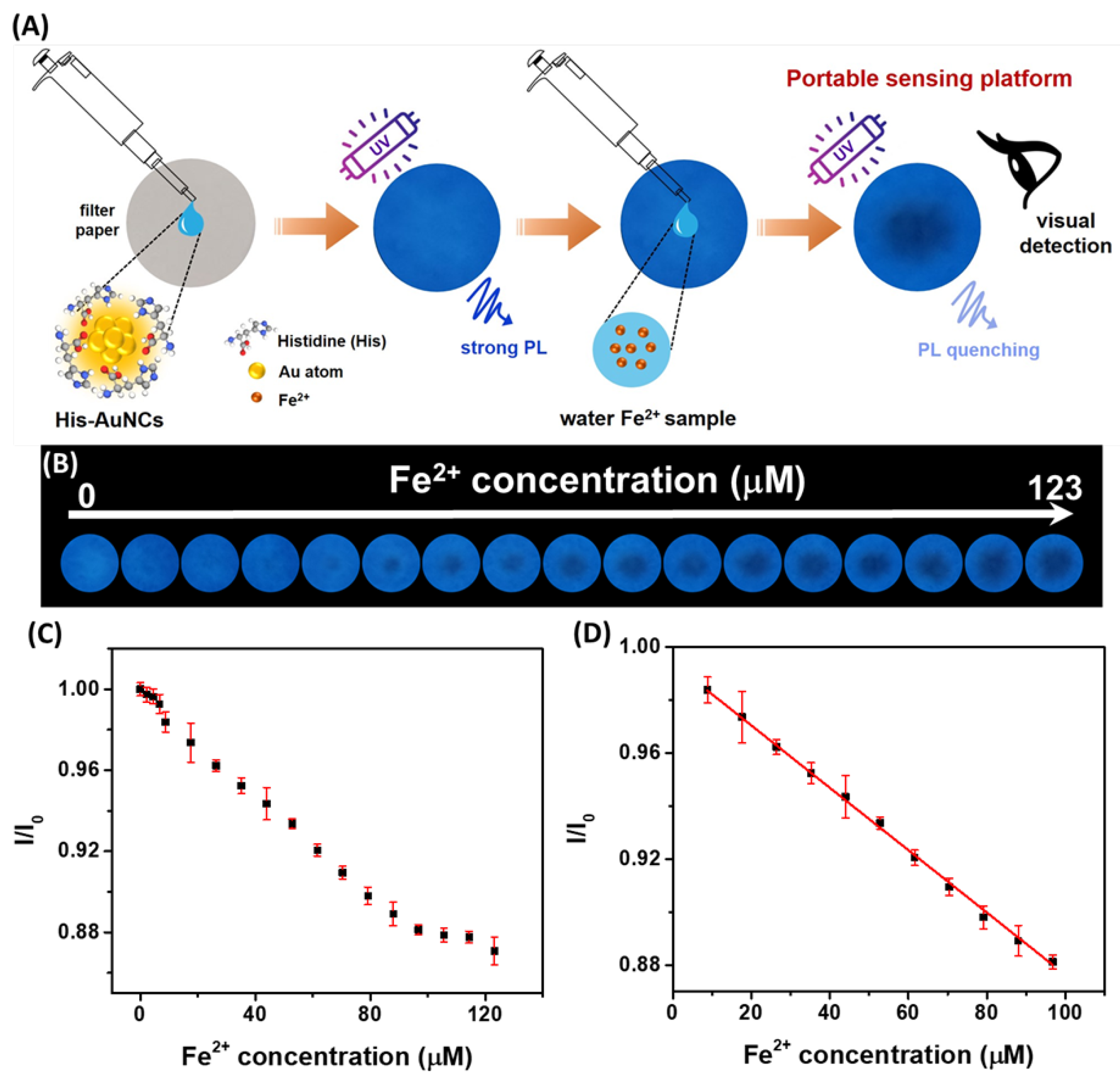

66]. In this format, photoluminescence was quenched through Cu²⁺ chelation with BSA cysteine residues. The system supported both solution-based quantification, offering a dual linear range (0–17 µM and 17–1724 µM) and a low detection limit of 0.83 µM, and paper-based sensing that enabled naked-eye detection under UV light down to 5 µM. The paper strips remained functional for at least 14 days and performed reliably across a variety of water samples, illustrating the potential for low-cost, eco-friendly field diagnostics. Building on this platform, our group later developed a more advanced paper-based sensing system for iron ion detection using histidine-stabilized AuNCs (His-AuNCs) synthesized via a microwave-assisted method (

Figure 9A) [

19].

These blue-emitting NCs (471 nm) enabled detection of both Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ ions, with application in both solution and paper formats. The paper-based strips supported rapid visual detection under UV light, while the integration of smartphone image analysis allowed for precise quantification, achieving a detection limit of 3.2 µM (

Figure 9B-D). When tested on real water sources, including river, spring, and tap water, the sensor delivered recoveries between 102% and 105.4%, highlighting its potential for portable, accessible environmental monitoring.

Metal NCs have proven to be highly effective platforms for ion detection, achieving excellent sensitivity, selectivity, and stability across both single-ion and multi-ion sensing formats. Their successful application in real samples, including environmental waters and biological fluids, highlights their practical relevance. Notably, paper-based NC sensors bring added value through portability, low cost, and ease of visual or smartphone-assisted readout. Looking ahead, the integration of NC-based sensors into smart, low-power devices, such as smartphone-linked diagnostics and wearable formats, will likely drive widespread adoption in environmental surveillance and point-of-care testing. Continued innovation in ligand chemistry, doping strategies, and surface engineering will enable enhanced selectivity, stability, and multiplexing capabilities. Furthermore, bridging sensing with real-time data transmission and AI-based analysis could unlock automated contaminant tracking and health monitoring systems. As regulatory pressures grow for on-site and decentralized monitoring, NC-based sensors are poised to become essential components of next-generation analytical technologies.

3.3.2. Small Molecules Detection

The application of metal NCs in sensing small molecules has expanded significantly, with tailored platforms now offering high sensitivity, selectivity, and practical deployment across diverse analyte classes. Among the earliest examples targeting pesticides, Yang et al. developed a ratiometric fluorescence assay for carbendazim (CBZ) detection using a nanohybrid of N-doped carbon quantum dots and AuNCs [

67]. In this dual-signal platform, the addition of CBZ disrupts FRET-induced quenching, leading to fluorescence recovery and enhanced Rayleigh scattering. The assay showed broad dynamic ranges (1–100 µM and 150–1000 µM), a LOD of 0.83 µM, and excellent recovery in spiked fruit samples, providing a rapid (~10 min), label-free solution with high selectivity. Complementarily, Yixia Yang et al. targeted glyphosate, employing a Cu²⁺-modulated DNA-templated AgNCs (DNA–AgNCs) sensor [

68]. Glyphosate chelated Cu²⁺ ions that otherwise quenched the DNA–AgNCs, triggering a fluorescence turn-on effect. The sensor achieved a LOD of 5 µg/L and excellent selectivity over similar organophosphorus pesticides. It was successfully validated in mineral and tap water, offering a cost-effective tool for environmental glyphosate monitoring.

For biomolecular detection, several strategies highlight the versatility of NCs. Zhou et al. designed a DNA-AuNC-based platform for sensing DNA methyltransferase (MTase) activity, relevant to epigenetic cancer diagnostics [

69]. MTase-mediated cleavage and extension of DNA transformed the NC environment, quenching fluorescence via PET from G-rich sequences. The system demonstrated a LOD of 0.178 U/mL and retained high accuracy in human serum and cancer cell lysates. Notably, it also enabled inhibitor screening for 5-Azacytidine, illustrating its dual diagnostic and drug discovery potential. For multiplex detection, Qin et al. anchored AuNCs onto Fe₃O₄@SiO₂ magnetic nanocomposites using a novel tris(2- carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)-mediated immobilization method [

70]. With duplex-specific nuclease-assisted amplification, simultaneous detection of miRNA-21 and miRNA-141 was achieved, reaching femtomolar LODs (0.020 and 0.017 pM respectively) and excellent specificity in serum and urine. This dual-analyte detection platform demonstrated magnetic enrichment, precise selectivity, and signal amplification, offering a powerful biosensing tool for clinical miRNA profiling. In the context of antioxidant monitoring, Qi et al. employed sanguinarine-templated CuNCs for detecting ascorbic acid (AA) [

71]. Here, MnO2NS quenched CuNC fluorescence via aggregation, while the presence of AA resulted into MnO2NS degradation and restored signal, producing a sensitive “turn-on” mechanism with a LOD of 6.9 µM. The method proved applicable to orange drinks and vitamin tablets, with recoveries of 94–105%. Finally, Bin Jardan et al. reported a PEI/DTH-stabilized nickel NCs platform for glutathione (GSH) detection [

72]. Initially quenched by Fe³⁺ ions, fluorescence was restored by GSH displacing Fe³⁺ via chelation. This system achieved an ultra-low LOD of 7.0 nM, rapid response (3 min), and high recovery in serum, urine, saliva, and supplements, demonstrating broad bioanalytical utility.

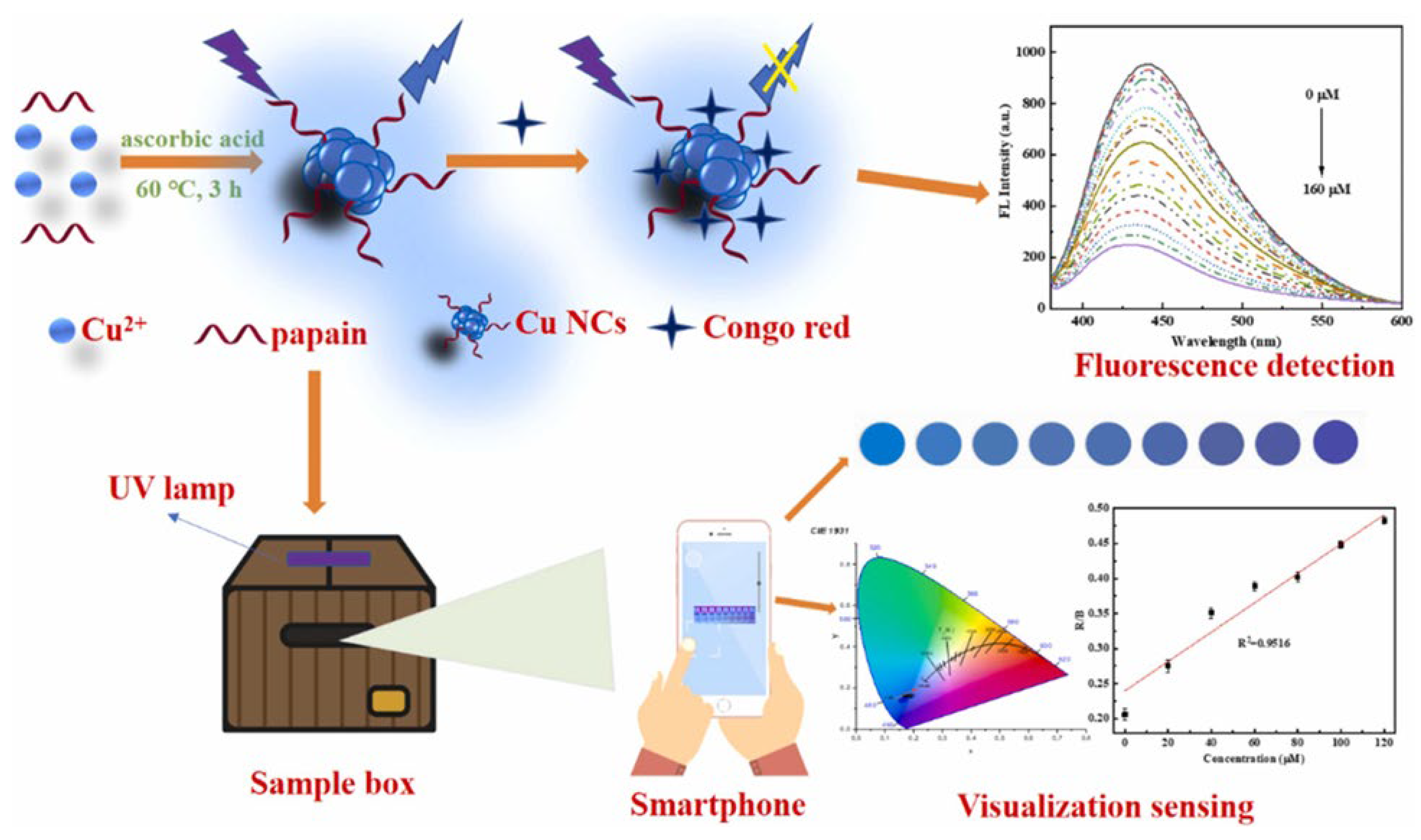

Shifting toward dyes, Zhang et al. reported a papain-stabilized CuNC (CuNC@PP) platform for Congo red detection [

73]. The probe relied on the inner filter effect (IFE), wherein the dye absorbed excitation and emission wavelengths, causing fluorescence quenching. The system offered a linear range of 0.5–160 µM with a low LOD of 0.085 µM via fluorescence, and 3.59 µM using smartphone RGB analysis (

Figure 10). High salt, pH, and photostability along with successful application in river and tap water highlight its field-readiness. The smartphone integration also added value for on-site, low-cost dye contamination monitoring.

The use of metal NCs in small molecule sensing has advanced considerably in the last years. From ratiometric and turn-on fluorescence platforms for pesticide and antioxidant detection to DNA-guided and magnetic nanocomposite-based biosensors for disease biomarkers, NCs have shown excellent sensitivity, selectivity, and robustness. Their modularity has enabled fine-tuned signal transduction mechanisms, including FRET modulation, PET-based quenching, and coordination-triggered recovery, yielding low detection limits and reliable performance in real-world samples such as fruit extracts, beverages, water, serum, and urine. Future efforts in small molecule sensing with NCs will likely emphasize integration into portable, miniaturized devices. Innovations in ligand design, ratiometric dual-emission systems, and enzyme-free amplification strategies will enhance performance while maintaining simplicity and low cost. Additionally, expanding the repertoire of analytes, particularly clinically relevant metabolites and biomarkers, will drive translation into diagnostic and therapeutic monitoring applications. The continued development of multiplexed detection schemes and real-time monitoring capabilities will position NC-based sensors as valuable tools in next-generation point-of-need analytical systems.

3.3.3. Pathogens Detection

Recent advances in pathogen detection have harnessed the unique optical and catalytic properties of metal NCs for the development of sensitive, selective, and field-deployable biosensing platforms. For bacterial detection, Evstigneeva et al. employed glutathione-capped AuNCs (GSH–AuNCs), emitting at 612 nm, for the fluorescence imaging of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli biofilms [

74]. These NCs selectively bound to the extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) within the biofilm matrix rather than penetrating bacterial cytoplasm, allowing for clear visualization using confocal laser scanning microscopy. The method achieved a detection limit of 1.7 × 10⁵ CFU/mL, showing a 10-fold improvement over traditional crystal violet staining assays, and maintained excellent photostability and low cytotoxicity, demonstrating its potential for non-invasive biofilm diagnostics. In the context of foodborne bacterial pathogens, Song et al. developed a dual-functional biosensor combining the peroxidase-mimicking activity of papain-stabilized AuNCs (papain@AuNCs) with the specificity of aptamers for E. coli O157:H7 [

75]. Upon binding to the bacterial surface, the catalytic efficiency of the NCs toward TMB oxidation (in the presence of H₂O₂) was significantly enhanced, producing a quantifiable colorimetric signal at 652 nm visible to the naked eye. The sensor achieved an exceptional limit of detection of 39 CFU·mL⁻¹ in pure cultures, and retained high sensitivity in ultra-high temperature (UHT), pasteurized, and raw milk (LODs ~500 CFU·mL⁻¹), while showing negligible cross-reactivity against 16 other foodborne bacteria. This work marks one of the first demonstrations of aptamer-enhanced nanozyme activity of AuNCs for real-world dairy safety monitoring. In a similar direction, Pang et al. introduced a colorimetric biosensor targeting Salmonella typhimurium using aptamer recognition to trigger the release of complementary DNAs that assemble into a three-way junction (3WJ) DNA structure [

76]. This template directed the in situ synthesis of Ag/Pt bimetallic NCs, which exhibited enhanced peroxidase-like activity. The system catalyzed the oxidation of 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) to generate a yellow signal at 450 nm upon acidification. The sensor achieved a LOD of 2.6 × 10² CFU/mL in buffer and 7.2 × 10² CFU/mL in commercial milk,and exhibited excellent specificity against multiple common pathogens. This strategy highlights the first application of 3WJ DNA scaffolds for NC templating and introduces a robust enzyme-free signal amplification approach adaptable to various targets.

For viral pathogen detection, Liu et al. reported a highly sensitive electrochemiluminescence (ECL) biosensor for Human Papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) DNA, integrating CRISPR/Cas12a with L-methionine-stabilized AuNCs (Met-AuNCs) [

77]. The presence of HPV-16 DNA activated the Cas12a/crRNA complex, which cleaved ferrocene-labeled single-stranded DNA (SH-ssDNA-Fc), thereby restoring the quenched ECL emission from the Met-AuNCs. This “turn-on” response enabled quantification down to 0.48 pM over a 1 pM–10 nM range. Notably, the assay functioned in undiluted human blood with >95% recovery, confirming its translational potential for point-of-care diagnostics. This study was the first to demonstrate Met-AuNCs as ECL emitters in a CRISPR-based format. Extending this CRISPR strategy, Tao et al. constructed a fluorescence sensor for Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) DNA by exploiting Cas12a-mediated cleavage of single-stranded DNA, which inhibited the formation of fluorescent metal NCs [

78]. Among AuNCs, AgNCs, and CuNCs evaluated, DNA-templated CuNCs outperformed in speed, photostability, and sensitivity, yielding a LOD of 0.54 pM within 25 minutes. The probe achieved >99% recovery in spiked serum and showed negligible cross-reactivity with HAV, HCV, and HIV. Importantly, this platform circumvented the need for fluorophore–quencher labeling, offering a low-cost and label-free alternative for clinical virology.

For enzymatic biomarkers, Wu et al. presented a fluorescence “turn-off” biosensor for trypsin, utilizing protamine-enhanced fluorescence of polyadenine DNA-templated AuNCs [

79]. Trypsin hydrolyzed protamine, destabilizing the DNA–AuNC complex and reducing its fluorescence at 475 nm. The sensor operated with a LOD of 1.5 ng/mL and maintained specificity against a range of non-target enzymes. When tested in diluted serum, it demonstrated recovery between 98.7%–103.5%, suggesting high clinical relevance for detecting pancreatic function or related disorders. Finally, for the detection of food toxins, Niu et al. engineered a fluorescence aptasensor for Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), combining catalytic hairpin assembly (CHA) with DNA nanoflower (DNF)-templated AuNCs and Mn-Metal-Organic Framework (Mn-MOF) spatial confinement [

80]. The resulting DNF@AuNCs emitted at 442 nm, and signal quenching occurred through G-rich sequence binding in the presence of AFB1. This multi-layered amplification strategy yielded an ultrasensitive LOD of 7 pg/mL across 0.01–200 ng/mL, and the sensor performed robustly in spiked peanut and corn flours, with recoveries exceeding 95%. This work is notable for integrating in situ NC synthesis with CHA amplification and MOF confinement to enhance both specificity and signal strength.

Recent advances in NC-based pathogen detection highlight their versatility in tackling a broad spectrum of targets, from bacterial biofilms and foodborne pathogens to viral DNA and enzymatic biomarkers. These platforms exploit the photoluminescent, catalytic, and surface-tunable nature of NCs, enabling highly sensitive, selective, and often label-free assays. NCs have demonstrated excellent performance across complex biological and food matrices, offering both visual and quantitative readouts. Their integration with aptamers, DNA scaffolds, and bio-recognition elements has enabled specific target recognition with low limits of detection, while maintaining biocompatibility and rapid response times. Looking ahead, pathogen detection using NCs is expected to further evolve toward portable, field-deployable platforms combining smartphone-based quantification, paper-based formats, and low-cost synthesis. The incorporation of programmable recognition systems like CRISPR/Cas and aptamer logic gates will facilitate multiplexed detection and dynamic response tuning. Additionally, expanding the role of NCs in enzyme-free catalytic amplification, combined with advances in material scaffolding (e.g., MOFs, DNA origami), will allow for higher signal gain and broader applicability. Future directions should focus on clinical validation, regulatory approval, and integration into point-of-care diagnostics and food safety surveillance, bringing NC-based sensing technologies closer to real-world deployment.

As discussed, metallic NCs provide versatile sensing platforms capable of detecting ions, small molecules, and pathogens with high sensitivity and selectivity. Their tunable surface chemistry and responsive photoluminescence make them particularly effective in translating molecular recognition into measurable optical signals across diverse environments. To consolidate these advances,

Table 4 summarizes representative examples of NCs employed in sensing applications.

3.4. Catalysis

Catalysis represents one of the most dynamic frontiers for metal NCs, enabling atom-efficient transformations that are central to energy, environmental, and synthetic chemistry [

81]. With their precisely defined atomic arrangements, abundant low-coordinated surface atoms, and size-dependent electronic structures, NCs offer catalytic behaviors that differ fundamentally from larger NPs or bulk metals [

82,

83,

84,

85]. Their tunable reactivity, combined with ligand-directed surface modulation, makes them especially appealing for activating small molecules under mild conditions.

This section highlights recent advances in NC-driven catalysis, with a focus on key sustainable processes: CO₂ reduction, water splitting for hydrogen evolution, dye degradation for wastewater remediation, N₂ fixation, H₂O₂ generation. These systems not only demonstrate high activity and selectivity, but also offer mechanistic insights into how atomic precision, support effects, and electronic modulation govern catalytic performance.

3.4.1. CO2

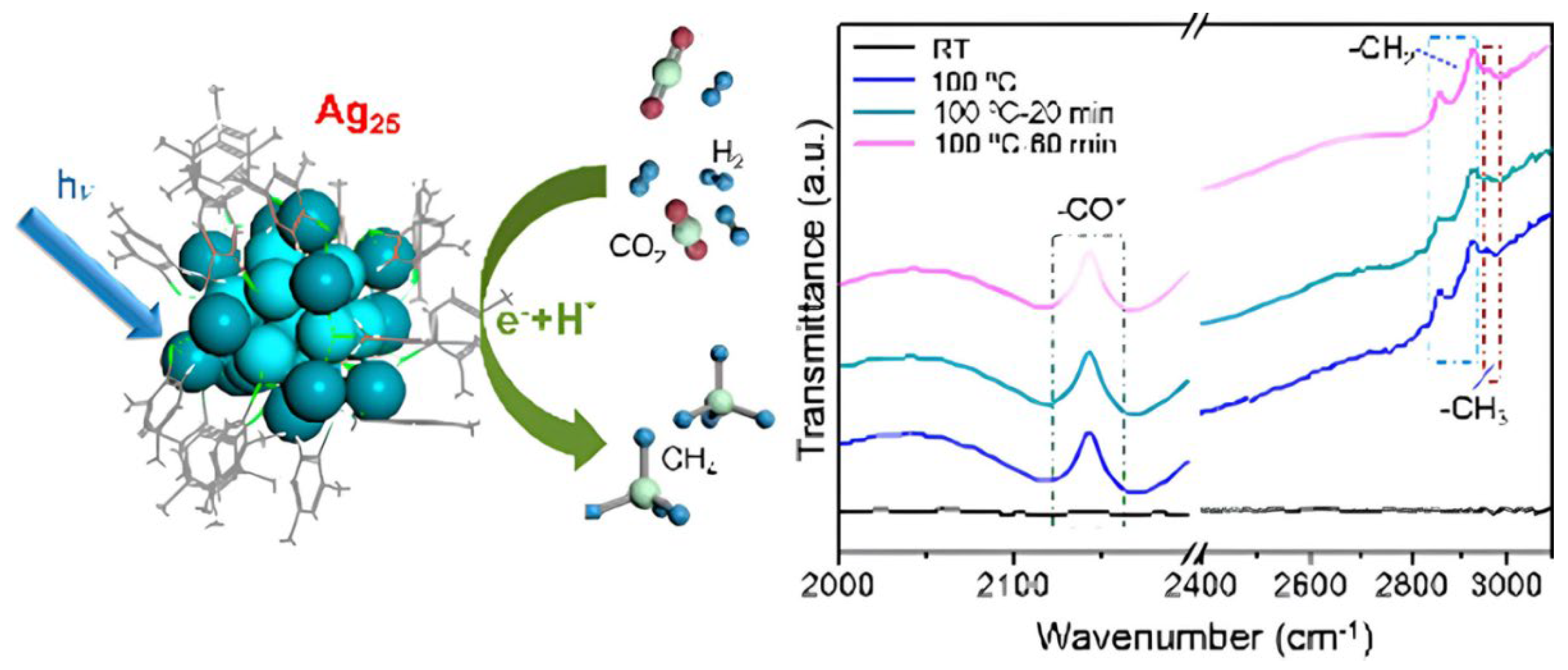

The catalytic reduction of CO₂ using atomically precise metal NCs has garnered significant attention due to their molecularly tunable active sites, well-defined structures, and efficient light-harvesting capabilities. In the context of methane (CH₄) production, Xiong et al. demonstrated the use of Ag₂₅(SPhMe₂)₁₈ NCs for photodriven CO₂ hydrogenation (

Figure 11) with exceptional performance [

86]. These ~1.5 nm clusters feature an icosahedral Ag₁₃ core and exhibited nearly 100% selectivity toward CH₄, outperforming larger Ag nanoparticles which showed no activity under identical conditions.

IR spectroscopy and DFT simulations revealed a multistep reduction pathway involving adsorbed CO₂, conversion to formyl and formaldehyde intermediates, and surface CHₓ formation prior to methane evolution. The discrete molecular orbitals of Ag₂₅, coupled with their long photoluminescence lifetime and strong light absorption, were critical in promoting multielectron transfer under visible light. When carbon monoxide (CO) is the desired product, Au-based NCs have also shown remarkable efficiency and selectivity. Jiang et al. developed a hybrid catalyst by immobilizing ultrasmall AuNCs (~1.8 nm) onto a UiO-68 Zr-based MOF functionalized with N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) [

87]. This covalently linked Au–NHC–MOF interface facilitated charge separation and efficient electron transfer from light-excited AuNCs into the MOF conduction band, enhancing CO₂ activation. The resulting system achieved a CO evolution rate of 57.6 mmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹, significantly surpassing the performance of physical Au/MOF mixtures, and showed stable operation over multiple cycles with minimal generation of H₂ or CH₄. A different design by Tian et al. used ligand-free Au₂₅ NCs deposited on BiOBr nanosheets [

88]. These clusters served both as charge acceptors and catalytic centers, improving interfacial charge transfer and lowering energy barriers for the formation of key intermediates like *COOH and *CO, as confirmed by DFT. The CO generation rate increased to 43.57 µmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹, nearly 3-fold that of pristine BiOBr, with high selectivity for CO and excellent photocatalytic stability over 25 hours.

Among Cu-based NC systems, several strategies have targeted either CO or formic acid (HCOOH) production. Dong et al. designed a crystalline Cu₆–NH cluster coordinated by 2-mercaptopyrimidine ligands, where protonated nitrogen atoms act as intramolecular proton donors, effectively relaying protons to CO₂ molecules adsorbed on Cu sites [

89]. This structure enabled a CO evolution rate of 148.8 µmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹, with nearly 100% selectivity toward CO, and long-term operational stability. DFT calculations and in situ spectroscopies confirmed that the presence of hydrogen bonds significantly reduced the energy barrier for the *COOH intermediate formation, the rate-determining step in CO₂ reduction. Complementary work by Dai et al. introduced ultrasmall Cu NCs (~1.6 nm) embedded in Zr-based MOFs (MOF-801 and UiO-66-NH₂) via a seed-mediated growth method [

90]. These core–shell structures promoted synergistic host–guest interactions, leading to enhanced charge separation and CO₂ adsorption. Particularly, Cu NCs@UiO-66-NH₂ favored formic acid production with 86% selectivity, achieving HCOOH rates up to 128 µmol·h⁻¹·g⁻¹ under UV light. The amino-functionalized MOF improved visible light absorption and created a favorable microenvironment for CO₂ activation at Cu⁺/Cu⁰ interfacial sites.

Expanding beyond gas-phase products, Qiao et al. reported a novel approach for CO₂ fixation into cyclic organic molecules via the carboxylative cyclization of propargylamines into oxazolidinones [

83]. This transformation was catalyzed by a Cu₆-NH₂ NC featuring dual Lewis acid–base functionality, where Cu⁺ centers activated the alkyne moiety and terminal –NH₂ groups stabilized amine–CO₂ intermediates through hydrogen bonding. The catalyst operated under ambient conditions (1 atm CO₂, 30 °C) without cocatalysts or solvents, achieving up to 99% yield and turnover frequencies (TOFs) of 387 h⁻¹, markedly higher than traditional homogeneous systems. Notably, it also demonstrated efficiency under simulated flue gas conditions, scalability to gram quantities, and reusability over five cycles with negligible loss of activity.

Therefore, atomically precise metal NCs exhibit high efficiency in catalyzing CO₂ into high-value products such as methane, carbon monoxide, formic acid, and oxazolidinones, showcasing how their tunable active sites, discrete electronic structures, and strong light-harvesting properties enable selective multielectron transfer and efficient charge separation under mild conditions. Looking forward, future directions should focus on developing scalable and environmentally benign synthetic routes for metal NCs that retain atomic precision and structural integrity under catalytic conditions, integrating NC-based systems into photoelectrochemical devices for solar-to-fuel conversion, expanding the product scope beyond simple C₁ compounds toward higher hydrocarbons or C–C coupled molecules, and ensuring catalyst robustness under realistic flue gas environments. Advancing mechanistic understanding through spectroscopies and computational modeling will be crucial for rational design, while the development of hybrid architectures combining NCs with porous or two-dimensional matrices holds great potential for enhancing activity, selectivity, and recyclability in practical CO₂ valorization applications.

3.4.2. Water Splitting

The photocatalytic splitting of water into hydrogen and oxygen remains one of the most sought-after strategies for sustainable energy generation, and atomically precise metal NCs have emerged as versatile co-catalysts and active sites in this field due to their well-defined structures, tunable energy levels, and superior charge separation properties. One of the foundational examples is the work of Wang et al., who explored the integration of thiolate-protected Ag₄₄(SR)₃₀ NCs with commercial TiO₂ NPs to form a type II heterojunction interface where the conduction band of TiO₂ is lower in energy than the conduction band of the NCs, that dramatically enhanced hydrogen evolution under simulated sunlight [

91]. The Ag₄₄ NCs, with their five distinct absorption bands and narrow HOMO–LUMO gap of ~0.77 eV, functioned dually as photosensitizers and co-catalysts. Upon UV-Vis excitation, holes generated in TiO₂ were effectively transferred to the HOMO of Ag₄₄, while electrons from the excited Ag NCs were injected into the TiO₂ conduction band, resulting in efficient charge separation and suppressed recombination. Ultrafast spectroscopy and transient absorption data revealed extended charge carrier lifetimes (>2 ns), which translated into a remarkable hydrogen evolution rate of 7.4 mmol·h⁻¹·g⁻¹, ten times higher than bare TiO₂ and comparable to TiO₂-Pt systems, without the use of noble metal NPs. In a complementary strategy, Fu et al. harnessed the inherent instability of glutathione-capped AuNCs (Aux@GSH) as a functional asset rather than a limitation [

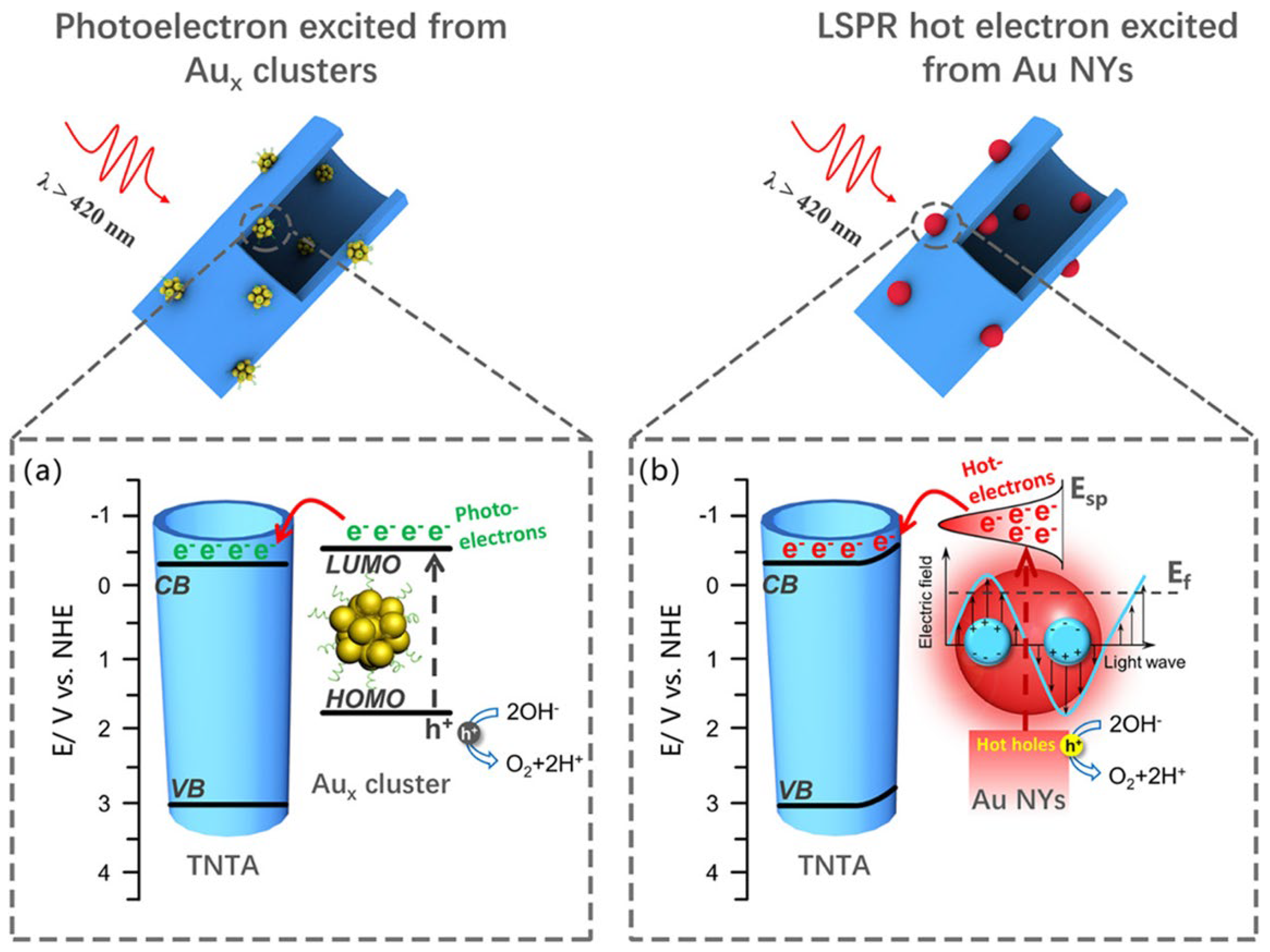

92]. They constructed a complex heterostructure comprising CdS nanowires enveloped by CdTe and PDDA layers, onto which Aux@GSH NCs were deposited. Under visible light, these Au NCs underwent in situ transformation into small Au nanocrystals (~3 nm), which, rather than diminishing performance, acted as efficient electron sinks. The layered CdS@CdTe@PDDA@Aux structure formed a cascade energy alignment that guided photoexcited electrons from CdS to the Au domains via CdTe and PDDA intermediates, greatly improving electron migration and interfacial redox kinetics. This architecture achieved a hydrogen evolution rate of 4.42 mmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹, more than 14-fold greater than pristine CdS, with a solar-to-hydrogen (STH) efficiency of 24.1% and remarkable stability over multiple cycles. Another study by Dai et al. systematically compared the performance of glutathione-capped AuNCs versus larger plasmonic Au nanocrystals when deposited on TiO₂ nanotube arrays (TNTAs) for photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting [

93]. They showed that Aux@GSH clusters (including Au₂₅(GSH)₁₈) significantly outperformed their plasmonic counterparts in terms of photocurrent generation (

Figure 12), charge carrier density, and applied bias photon-to-current efficiency (ABPE).

The TNTAs–Aux heterostructure generated a photocurrent density of 0.07 mA/cm², compared to only 0.015 mA/cm² for TNTAs–Au. This superiority was attributed to the molecular-like nature of AuNCs, which promoted direct LUMO-to-CB charge transfer, minimized recombination, and extended electron lifetimes. The alignment of energy levels further validated the efficient electron injection from Aux LUMO to the TiO₂ CB, positioning these NCs as more effective sensitizers than traditional plasmonic structures.

Expanding on structural stabilization, Kawawaki et al. addressed the challenge of NC aggregation post-ligand removal by designing a Cr₂O₃-encapsulated system using Au₂₅(PET,p-MBA)₁₈ NCs supported on BaLa₄Ti₄O₁₅ [

94]. Through controlled calcination at ~300 °C, the protective thiolate ligands were partially desorbed, exposing active gold surfaces while retaining NC size and structure. Subsequently, UV-induced deposition of a thin Cr₂O₃ layer created a stabilizing shell around the AuNCs, preventing sintering and preserving catalytic performance. This system demonstrated efficient and stable hydrogen and oxygen evolution with a 2:1 H₂:O₂ stoichiometry, and retained its photocatalytic activity over extended irradiation cycles. The optimized interfacial engineering and ligand desorption mechanism were supported by DIP-MS, EXAFS, and TEM analyses, establishing a model for the transition from ligand-protected to heterogeneous active catalysts. While Kawawaki et al. relied on an oxide semiconductor support, Huang et al. developed a distinct MOF-based system [

95]. They proposed an elegant in situ auto-reduction method to generate ultrasmall Pt clusters (1–2 nm) within the pores of MIL-125-NH₂ modified by formaldehyde. The amino groups were converted to –NH–CH₂OH, which served as internal reductants to reduce Pt²⁺ precursors into metallic Pt⁰ without external agents. This confinement strategy ensured high Pt dispersion, minimized aggregation, and optimized the metal–support interface. The resulting Pt(1.5)/MIL-125-NH-CH₂OH catalyst achieved a hydrogen evolution rate of 4,496.4 μmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹ under visible light, approximately 31 times higher than the bare MOF, confirming the synergistic role of Pt NCs in accelerating charge transfer and enhancing photocatalytic efficiency. Using an alternative strategy for single-atom catalysis, another study employed thermal decomposition of Pt₅(GS)₁₀ NCs on multi-armed CdS nanorods, forming atomically dispersed Pt atoms coordinated with surface sulfur atoms [

96]. These Pt–S₄ sites acted as electron sinks, rapidly accepting photogenerated electrons and promoting spatial charge separation. Ultrafast transient absorption spectroscopy and DFT calculations confirmed that the Pt–S₄ sites exhibited optimal hydrogen adsorption energetics, accounting for the high catalytic activity. The system delivered an impressive H₂ evolution rate of 13.0 mmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹ with 25.08% quantum efficiency at 400 nm, setting a benchmark for NC-derived single-atom hydrogen evolution reaction catalysts.

On the covalent organic frameworks (COF) front, Li et al. designed a π-conjugated 2D COF (PY-DHBD-COF) with adjacent hydroxyl and imine-N coordination sites that selectively adsorbed PtCl₆²⁻ ions for in situ photoreduction into ultrasmall Pt clusters [

97]. This structural design enabled site-specific anchoring of Pt and promoted electron transfer from the COF to Pt domains upon light irradiation. At optimal loading (3 wt% Pt), the system achieved a remarkable hydrogen evolution reaction rate of 71,160 μmol·g⁻¹·h⁻¹ and demonstrated 8.4% apparent quantum yield at 420 nm, along with 60-hour operational stability and uniform Pt dispersion. DFT simulations validated the strong Pt binding energy and electron transfer pathways. Lastly, Bootharaju et al. demonstrated the catalytic superiority of bimetallic core–shell clusters [Au₁₂Ag₃₂(SePh)₃₀]⁴⁻ electrostatically anchored on oxygen-deficient TiO₂ for hydrogen evolution [