Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

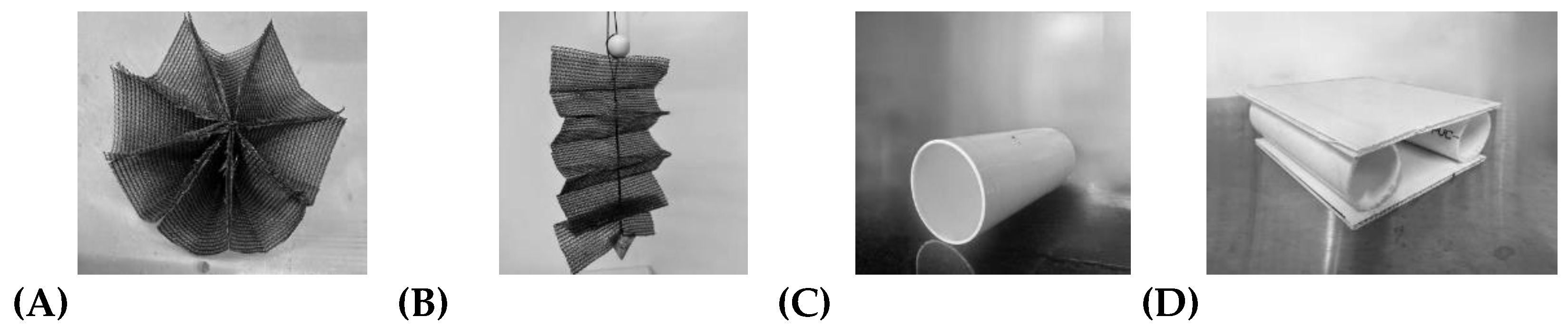

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

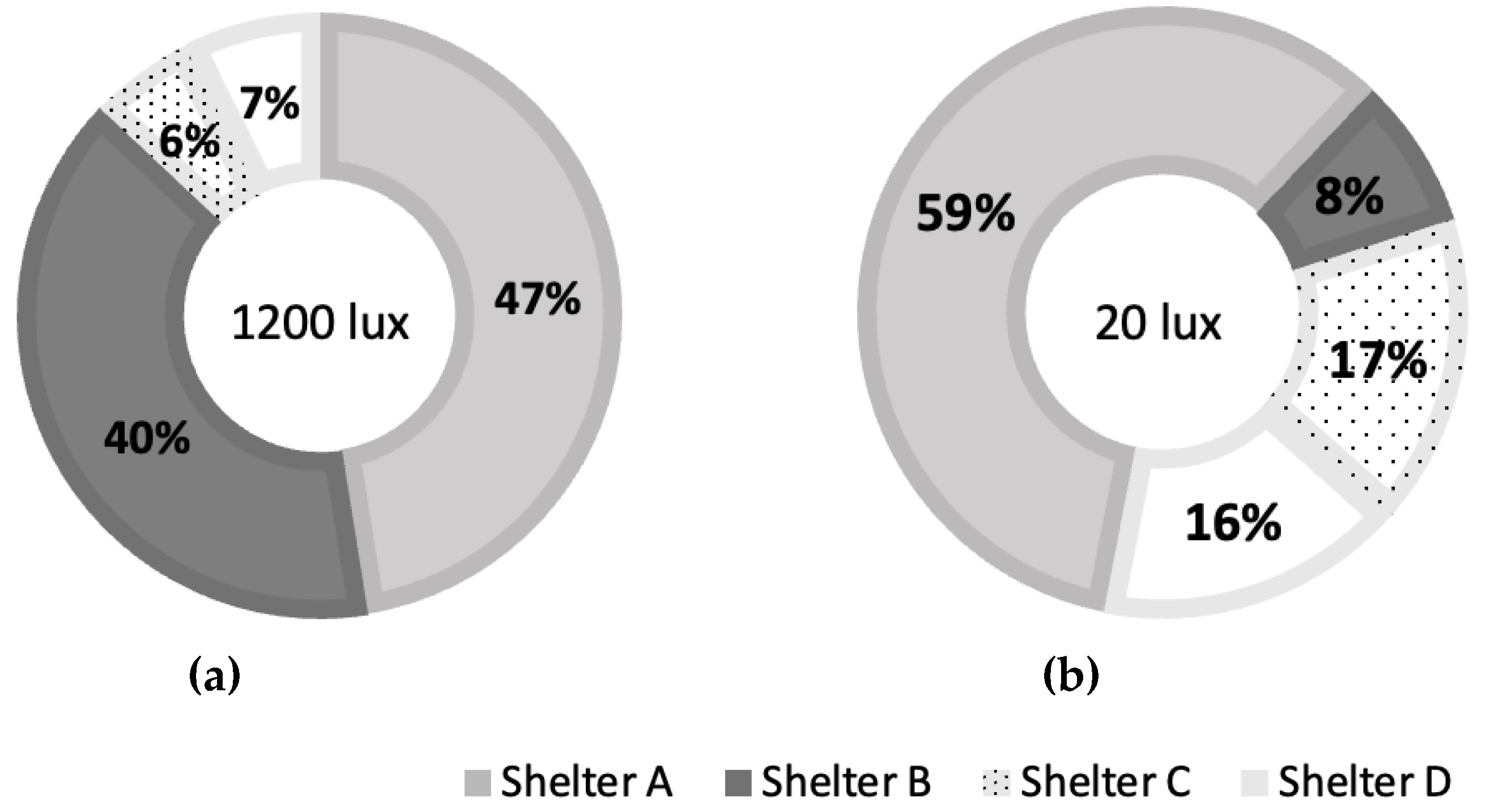

3.1. Shelter Preference

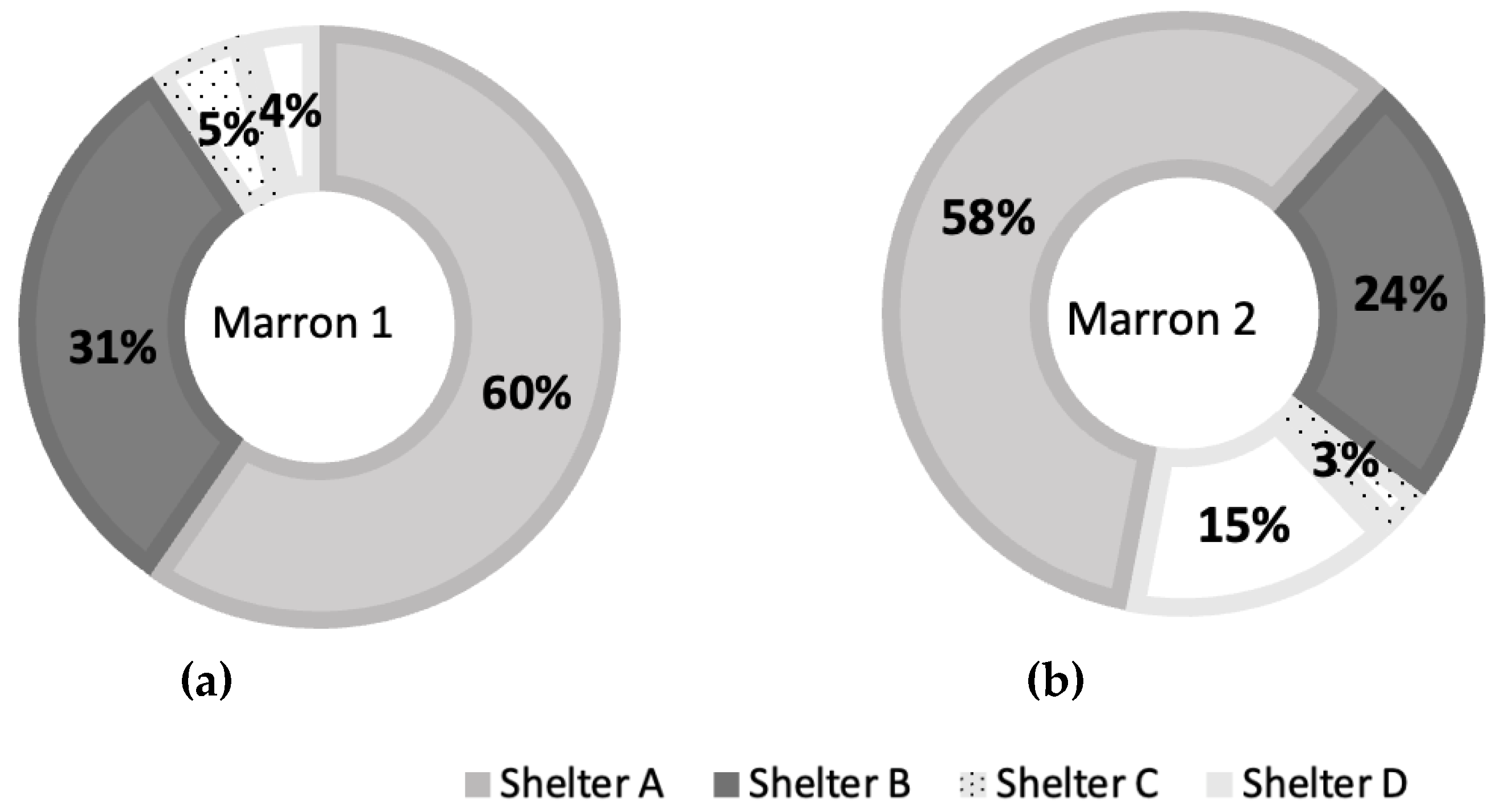

3.1.1. Trial 1 - One Marron with Four Shelters

3.1.2. Trial 2 - Two Marron with Eight Shelters

3.2. The Resident Time

3.2.1. Trial 1 - One Marron with Four Shelters

3.2.2. Trial 2 - Two Marron with Eight Shelters

3.3. The search time

3.3.1. Trial 1 - One Marron with Four Shelters

3.3.2. Trial 2 - Two Marron with Eight Shelters

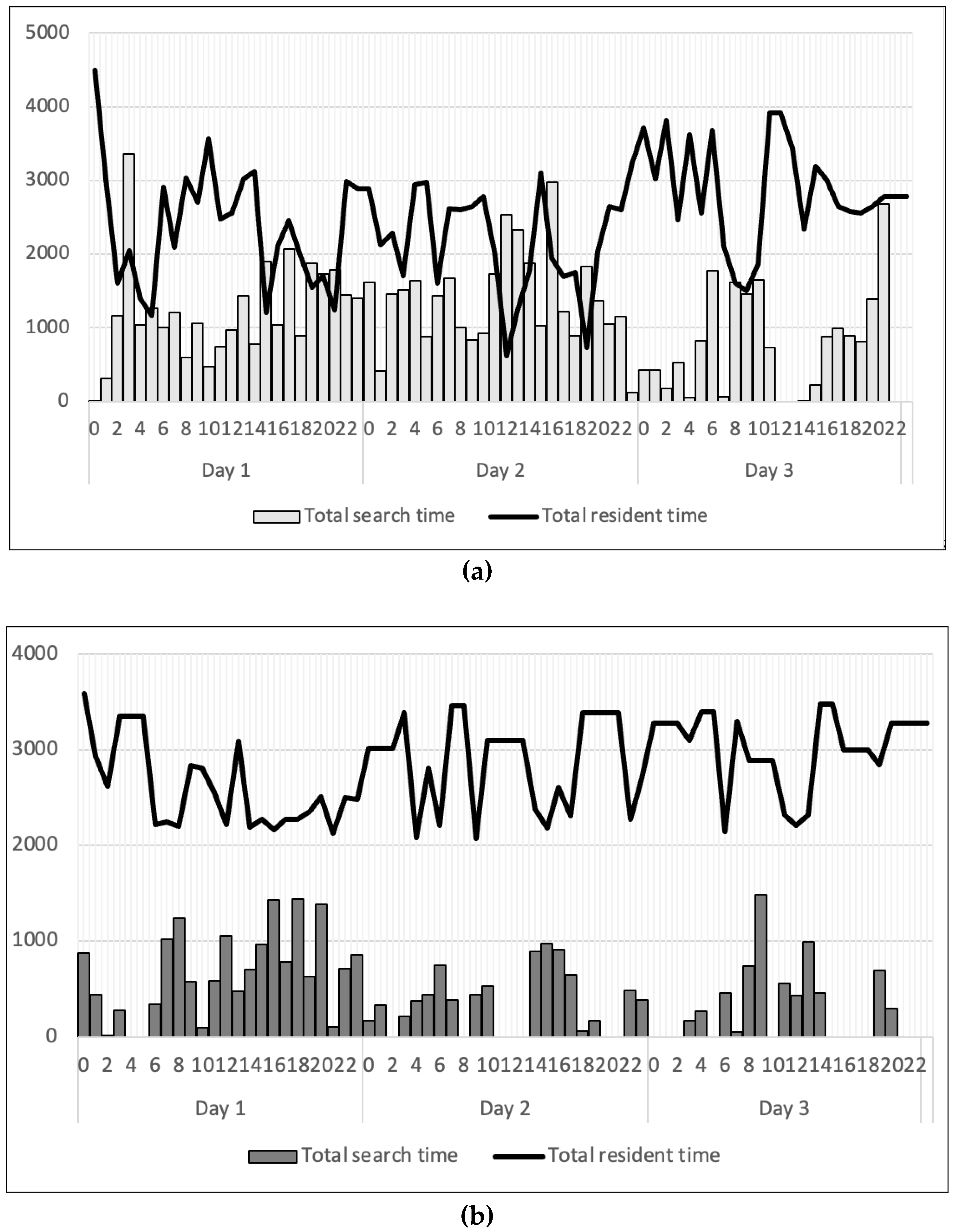

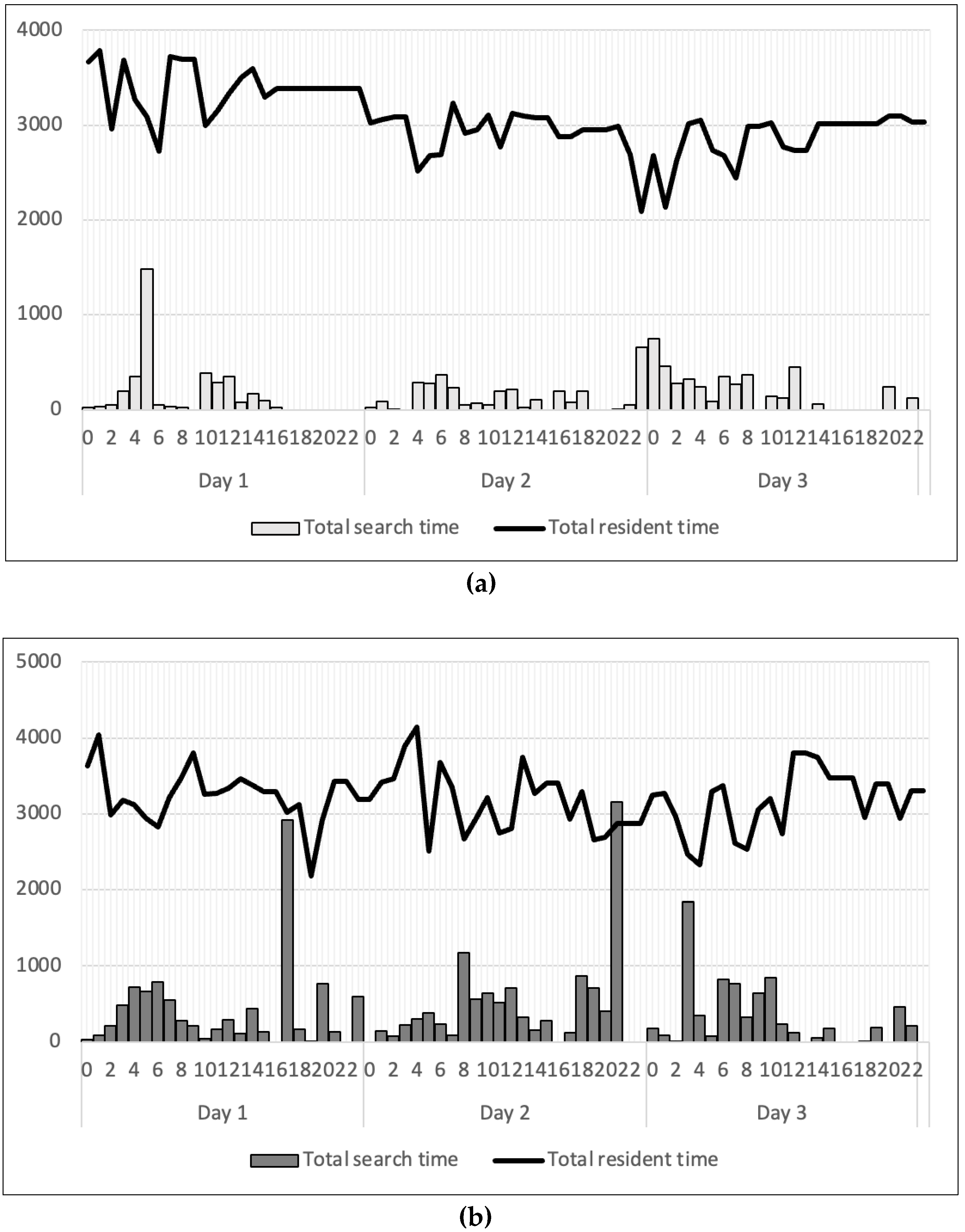

3.4. Daily Activity Pattern

3.4.1. Trial 1 - One Marron with Four Shelters

3.4.2. Trial 2 - Two Marron with Eight Shelters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2024 - Blue transformation in action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, A.D. Marron growing: a Western Australian rural niche market? Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2009, 21, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, C. , Improved performance of marron using genetic and pond management strategies. Fisheries Research Contract Report 2007, 17, 1–178. [Google Scholar]

- McClain, W.R. Crayfish aquaculture. Fish. Aquac 2020, 9, 259. [Google Scholar]

- Souty-Grosset, C.; et al. Atlas of crayfish in Europe; Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle Paris, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, A.; Patullo, B.W.; Macmillan, D.L. Exploration in a T-Maze by the CrayfishCherax destructorSuggests Bilateral Comparison of Antennal Tactile Information. Biol. Bull. 2005, 208, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, J.; Sandeman, D. Crayfish (Cherax destructor) use Tactile Cues to Detect and Learn Topographical Changes in Their Environment. Ethology 2000, 106, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, J.W.; Vehrencamp, S.L. Principles of animal communication, Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, 1998; Vol. 132.

- Aschoff, J. Freerunning and entrained circadian rhythms. In Biological rhythms; Springer, 1981; pp. 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Prosser, C.L. Physiological variation in animals. Biological Reviews 1955, 30, 229–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanjul-Moles, M.a.L. , et al. Effect of variation in photoperiod and light intensity on oxygen consumption, lactate concentration and behavior in crayfish Procambarus clarkii and Procambarus digueti. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 1998, 119, 263–269. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, K.M.; Moore, P.A. The intensity and spectrum of artificial light at night alters crayfish interactions. Mar. Freshw. Behav. Physiol. 2019, 52, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Celada, J.D.; García, V.; Carral, J.M.; González, Á.; Sáez-Royuela, M. Shelter and lighting in the intensive rearing of juvenile crayfish (Pacifastacus leniusculus, Astacidae) from the onset of exogenous feeding. Aquac. Res. 2010, 42, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozák, P.; Gallardo, J.M.; García, J.C.E. Light preferences of red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii). Hydrobiologia 2009, 636, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeel, T.; Vervaecke, H.; Roelant, E.; Platteaux, I.; Adriaen, J.; Durinck, G.; Meeus, W.; van de Perre, L.; Aerts, S. Evaluation of the influence of light conditions on crayfish welfare in intensive aquaculture. In Food futures: ethics, science and culture; Wageningen Academic: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, E.R.; Thiel, M. Chemical and Visual Communication During Mate Searching in Rock Shrimp. Biol. Bull. 2004, 206, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.C. , Effects of temperature, photoperiod, substrate, and shelter on survival, growth, and biomass accumulation of juvenile Pacifastacus leniusculus in culture. Freshwater crayfish 1981, 4, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen, R.; Ruohonen, K.; Tulonen, J. Effects of bottom substrate and presence of shelter in experimental tanks on growth and survival of signal crayfish,Pacifastacus leniusculus(Dana) juveniles. Aquac. Res. 2003, 34, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figler, M.H.; Cheverton, H.M.; Blank, G.S. Shelter competition in juvenile red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii): the influences of sex differences, relative size, and prior residence. Aquaculture 1999, 178, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangpen, P. The role of shelter in Australian freshwater crayfish (Cherax spp.) polysystems. 2007, [Curtin University.

- Ratchford, S.G.; Eggleston, D.B. Temporal shift in the presence of a chemical cue contributes to a diel shift in sociality. Anim. Behav. 2000, 59, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.M.; Ruscoe, I.M. Assessment of Five Shelter Types in the Production of Redclaw Crayfish Cherax quadricarinatus (Decapoda: Parastacidae) Under Earthen Pond Conditions. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2001, 32, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Elwood, R. The mismeasure of animal contests. Anim. Behav. 2003, 65, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tews, J.; Brose, U.; Grimm, V.; Tielbörger, K.; Wichmann, M.C.; Schwager, M.; Jeltsch, F. Animal species diversity driven by habitat heterogeneity/diversity: the importance of keystone structures. J. Biogeogr. 2003, 31, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meager, J.; Williamson, I.; Loneragan, N.; Vance, D. Habitat selection of juvenile banana prawns, Penaeus merguiensis de Man: Testing the roles of habitat structure, predators, light phase and prawn size. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2005, 324, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C.; Skinner, C.; Alberstadt, P.; Antonelli, J. Short communication: Importance of adequate shelters for crayfishes maintained in aquaria. Aquar. Sci. Conserv. 1997, 1, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Nagayama, T. Shelter preference in the Marmorkrebs (marbled crayfish). Behaviour 2016, 153, 1913–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, E.; Lindström, K. Body size and shelter possession in mature signal crayfish, Pacifastacus leniusculus. Annales Zoologici Fennici 1993, 30, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston, D.B.; Lipcius, R.N. Shelter Selection by Spiny Lobster Under Variable Predation Risk, Social Conditions, and Shelter Size. Ecology 1992, 73, 992–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fero, K.C.; Moore, P.A. Shelter availability influences social behavior and habitat choice in crayfish, Orconectes virilis. Behaviour 2014, 151, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.L.; Moore, P.A. The Influence of Dominance on Shelter Preference and Eviction Rates in the Crayfish, Orconectes rusticus. Ethology 2008, 114, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappan, P.; Balasundaram, C. Sheltering behaviour of Macrobrachium nobilii (Henderson and Matthai, 1910). Acta Ethologica 2003, 5, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, G.; Bagarinao, T.; Yong, A.S.K.; Fen, T.C.; Lim, L.S. Shelter colour preference of the postlarvae of the giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Fish. Sci. 2017, 83, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, G.; Austin, C. Combined effects of shelter and density on the growth and survival of juveniles of the Australian freshwater crayfish, Cherax destructor Clark. Aquaculture 1999, 170, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Shi, H.; Xu, W.; Su, Z. Research progress on the cannibalistic behavior of Aquatic Animals and The Screening of Cannibalism-Preventing Shelters (Review). Israeli Journal of Aquaculture-Bamidgeh 2020, 72, 21014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelli, G.M.; Hamilton, P.A. Effects of Food and Shelter on Aggressive Activity in the Crayfish Orconectes rusticus (Girard). J. Crustac. Biol. 1984, 4, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, L.; Gydemo, R. The locomotor activity patterns of juvenile noble crayfish (Astacus astacus) and the effect of shelter availability. Aquaculture 1988, 68, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, R.; Hörstgen-Schwark, G. Influence of social factors on the nocturnal activity pattern of the noble crayfish,Astacus astacus(Crustacea, Decapoda) in recirculating aquaculture systems. Aquac. Res. 2014, 46, 2929–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G. , et al. Effects of broodstock sizes, shelter, illumination and stocking density on breeding in red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii. Fisheries Science (Dalian) 2012, 31, 549–553. [Google Scholar]

- Fielder, D.; Thorne, M. Are shelters really necessary; Australian fisheries: aquaculture special: redclaw, Macreadie, M. (ed); Australian Government Publishing Service: Canberra, 1990; pp. 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.M. Production of juvenile redclaw crayfish, Cherax quadricarinatus (von Martens) (Decapoda, Parastacidae) I. Development of hatchery and nursery procedures. Aquaculture 1995, 138, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, N.M.; Crowley, P.H. Shelter Availability, Occupancy, and Residency in Size-Asymmetric Contests Between Rusty Crayfish,Orconectes rusticus. Ethology 2011, 118, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, A.J.F.; Hurtado-Zavala, J.I.; Reischig, T.; Heinrich, R. Circadian Regulation of Agonistic Behavior in Groups of Parthenogenetic Marbled Crayfish, Procambarus sp. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2009, 24, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franke, R.; Hörstgen-Schwark, G. Control of activity patterns in crowded groups of male noble crayfish Astacus astacus (Crustacea, Astacidea) by light regimes: A way to increase the efficiency of crayfish production? Aquaculture 2015, 446, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, R.W. Seasonal Activity, Migration and Distribution of the Crayfish, Pacifastacus Ieniusculus, in Lake Tahoe. Am. Midl. Nat. 1977, 97, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazlett, B.; Rittschof, D.; Ameyaw-Akumfi, C. Factors affecting the daily movements of the crayfish Orconectes virilis (Hagen, 1870) (Decapoda, Cambaridae), in Studies on Decapoda. 1979, Brill. pp. 121-130.

- Francis, R.C. On the Relationship between Aggression and Social Dominance. Ethology 1988, 78, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioni, A.; Gherardi, F. Agonism and interference competition in freshwater decapods. Behaviour 2004, 141, 1297–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, L. Outcomes of agonistic interactions alter sheltering behavior in crayfish. Behav. Process. 2021, 184, 104337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| The resident time (s) | Shelter types | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |

| 1200 lux | ||||

| Total time | 119,448 ± 11,251 | 23,342 ± 12,133 | 9,867 ± 8,556 | 13,273 ± 6,660 |

| Min | 42.67 ± 14.38 | 52.00 ± 17.04 | 83.33 ± 38.63 | 70.00 ± 25.17 |

| Max | 31,296 ± 11,251 | 5,230 ± 3,542 | 9,010 ± 8,462 | 8,115 ± 4,479 |

| 20 lux | ||||

| Total time | 183,021 ± 88,760 | 210.00 ± 152.27 | 437.67 ± 314.05 | 55,971 ± 54,121 |

| Min | 5,351 ± 5,258 | 190.67 ± 158.81 | ||

| Max | 83,121 ± 43,339 | |||

| Grouped by statistical difference | * |

** |

||

| The resident time (s) | Shelter types | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |

| Marron 1 | ||||

| Total time | 182,714 ± 24,558 | 40,174 ± 34,390 | 1,594 ± 1,028 | 5,247 ± 4,939 |

| Min | 2,994 ± 2,921 | 53.83 ± 14.90 | 473.67 ± 252.76 | 192.83 ± 117.18 |

| Max | 61,753 ± 11,305 | 18,374 ± 17,169 | 1,203 ± 752.43 | 1,669 ± 1,556 |

| Marron 2 | ||||

| Total time | 152,269 ± 23,272 | 23,896 ± 15,372 | 1,577 ± 472.46 | 62,853 ± 20,027 |

| Min | 7,019 ± 4,694 | 672.17 ± 413.70 | 578.50 ± 493.50 | 118.17 ± 15.21 |

| Max | 80,891 ± 19,584 | 18.37 ± 14,534 | 1,114 ± 400.25 | 38,579 ± 22,285 |

| Grouped by statistical difference | * |

** |

||

| Shelter | The search time (s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total time | Min | Max | |

| 1200 lux | |||

| A | 47,092 ± 14,025a | 4.67 ± 0.33 | 6,406 ± 726.670 |

| B | 26,974 ± 2,054a | 20.67 ± 7.33 | 4,056 ± 1,275 |

| C | 2,243 ± 485.35b | 23.67 ± 9.96 | 1,446 ± 402.78 |

| D | 5,500 ± 5,318b | 17.67 ± 5.61 | 2,693 ± 2,613 |

| 20 lux | |||

| A | 308.67 ± 178.91b | 13.00 ± 3.79 | 152.00 ± 71.65 |

| B | 52.00 ± 26.91b | 52.00 ± 26.91 | |

| C | 57.00 ± 28.58b | 57.00 ± 28.58 | |

| D | 306.00 ± 255.32b | 306.00 ± 255.32 | |

| The search time (s) | Light intensity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1200 lux | 20 lux | |||

| Marron 1 | Marron 2 | Marron 1 | Marron 2 | |

| Total | 4,315 ± 4,103a | 1,646 ± 1,522* | 10,727 ± 2,788b | 7,198 ± 3,403** |

| Min | 16.75 ± 11.16 | 10.67 ± 4.69 | 25.17 ± 6.81 | 20.75 ± 2.43 |

| Max | 1,300 ± 1,198 | 424.42 ± 361.81 | 2,733 ± 405.63 | 1,868 ± 283.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).