Introduction:

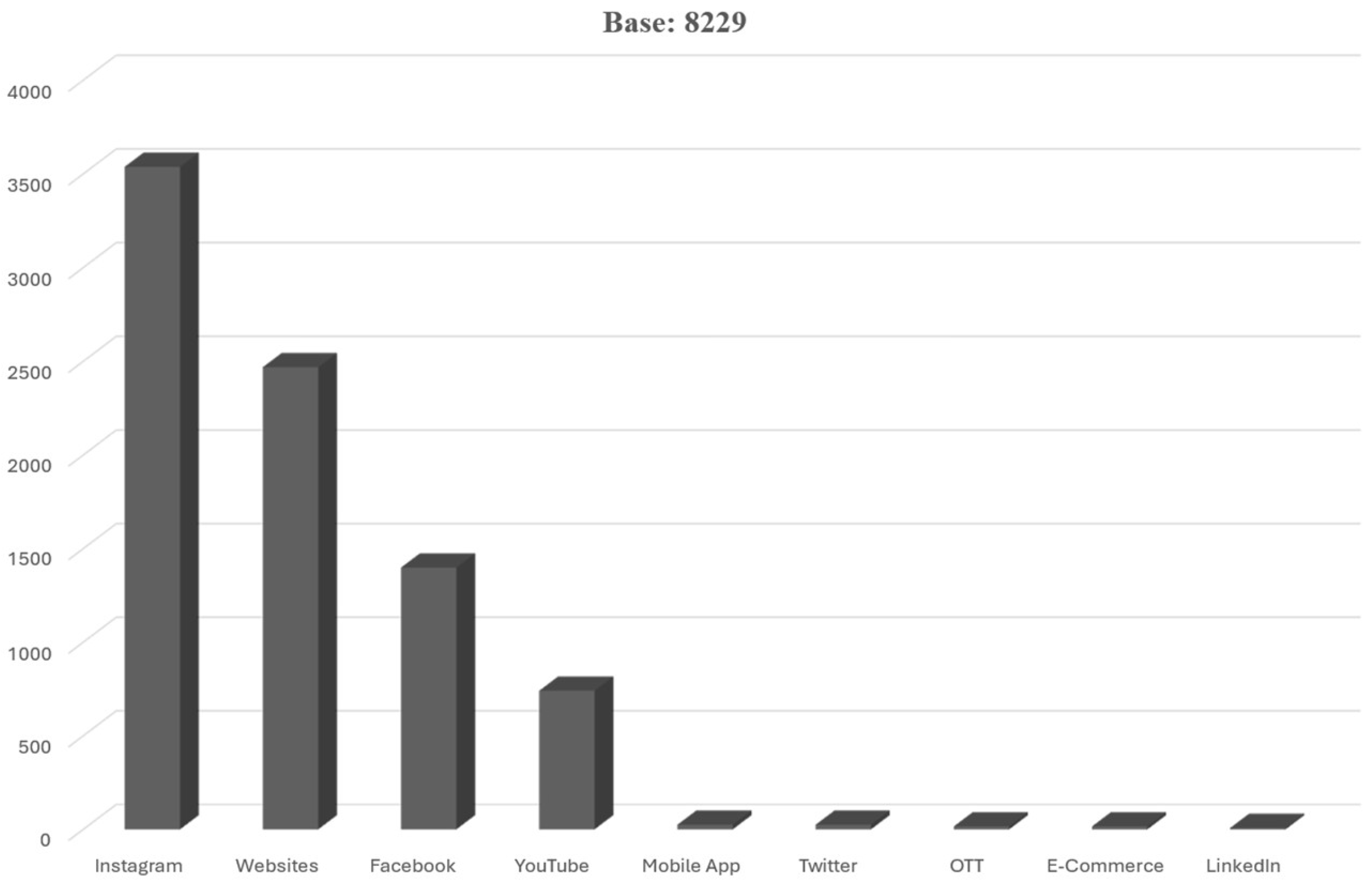

Online Reputation Management (ORM), with its advanced resource tools and accelerated services, is increasingly used to enhance brand reputation and build trust among target audiences. As shown in

Figure 1, this strategic approach enables coaching centers to effectively navigate the dynamic digital marketing landscape. Meanwhile, establishing online reputation has become a strategic weapon to influence the choice of coaching centers. These coaching centers as clients, project that a strong public image with fostering customer loyalty enhances a brand image in the digital landscape which may increase the turnover. With the advancement of online reputation management agencies and widespread availability of advanced Social Listening Tools, the importance of digital reputation has led the situation to widespread manipulation of perceived quality imparting of education backed up by the fake qualification of faculties at coaching centers, through fake ratings and paid reviews.

If a misleading advertisement is published, coupled with positive reviews and rankings on the media, they will direct the peer students’ choices. These choices of the peer group are followed by others thereby propelling greater number of enrolments which also guarantees institutes success. This is known as bandwagon effect (Kwek, Lei, Leong, & Peh, 2020), and it is also observed in Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities with the fear of missing out factor. With less accessible information about the authenticity of the facts, most of the students are gullible to the misleading claims. Few of the coaching institutes project an individual rank as batch ranks and propel the reviews on the social platforms. Most of these institutes do not give proof of statistical validation. This halo effect is responsible to manufacture trust. With all the three factors working hand in hand, the genuine reviews become redundant. The digital space is utilised for manipulation than performance.

The problem is compounded by weaknesses in regulatory oversight. While provisions under the Consumer Protection Act, Information Technology Act, and Indian Penal Code address certain aspects of digital deception, enforcement remains fragmented and reactive. In the absence of strong governance mechanisms, fabricated narratives often overshadow authentic student experiences, leaving parents and aspirants vulnerable to misinformation.

This study investigates the phenomenon of digital deception in India’s coaching industry by examining the mechanisms of fake reviews, fabricated rankings, and manipulated advertising. Using sentiment analysis of consumer feedback and an examination of public data, advertisements, and case studies, we highlight how systemic exploitation of psychological biases and digital platforms undermines consumer trust. The paper also identifies regulatory gaps and proposes a multi-pronged framework that integrates technological, legal, and ethical interventions to curb deceptive practices and restore credibility in the education sector.

Accountability is the key factor to repose the trust of the consumer. This study contributes a multi-dimensional framework to curb digital deception. A deft robust legal punishment is needed to contain the unethical practices. Adhering to the prescribed advertising standards and for the users collaborative linked framework like introduction of AI based fraud detection system, KYC linked review or rating mechanism, ethical disclosure mandates, centralized review and rating auditing along with outreach programs for consumers may reduce unethical practices. These measures, if implemented, would not only protect consumers but also propel India’s credibility as an emerging global educational hub.

2. Literature Review

Sentiment analysis is a highly automated process of analyzing and interpreting text data which are in form of reviews or ratings or digital narratives from various platforms (Gullipalli & Dholey, n.d.). It is also commonly termed as opinion mining. Research has highlighted that consumer narratives are often distorted by fake reviews (Gandhi, Hollenbeck, & Li, 2024), paid ratings, and algorithmic manipulation, which mask genuine consumer experiences. In education, sentiment analysis has become a vital tool to decode the perception of coaching centers by categorizing opinions as positive, negative, or neutral. The outcomes of such analysis often shape marketing techniques adopted by organizations to achieve financial success. Studies in e-learning platforms show that student feedback processed through sentiment mining provides insight into both service quality and manipulation strategies (Mite-Baidal, Delgado-Vera, Solís-Avilés, Espinoza, Ortiz-Zambrano, & Varela-Tapia, 2018). This establishes sentiment analysis as both a diagnostic tool and a lens to examine trust in digitally mediated education.

Key psychological concepts: bandwagon effect, halo effect, FOMO: Manufactured trust in the digital space is frequently rooted in psychological exploitation. Misleading advertisements trigger cascades of fake reviews and ratings, reinforcing the bandwagon effect, where students imitate peer choices (Molina, Wang, Sundar, Le, & DiRusso, 2023). In Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities, limited access to authentic information amplifies the fear of missing out (FOMO) (Emre & Köse, 2025) when institutes advertise exaggerated ranks or achievements. Similarly, the halo effect is created when a single success case is projected as representative of the institution’s overall quality. This also demonstrates the clamping of consumer psychology to manufacture trust and institutional credibility.

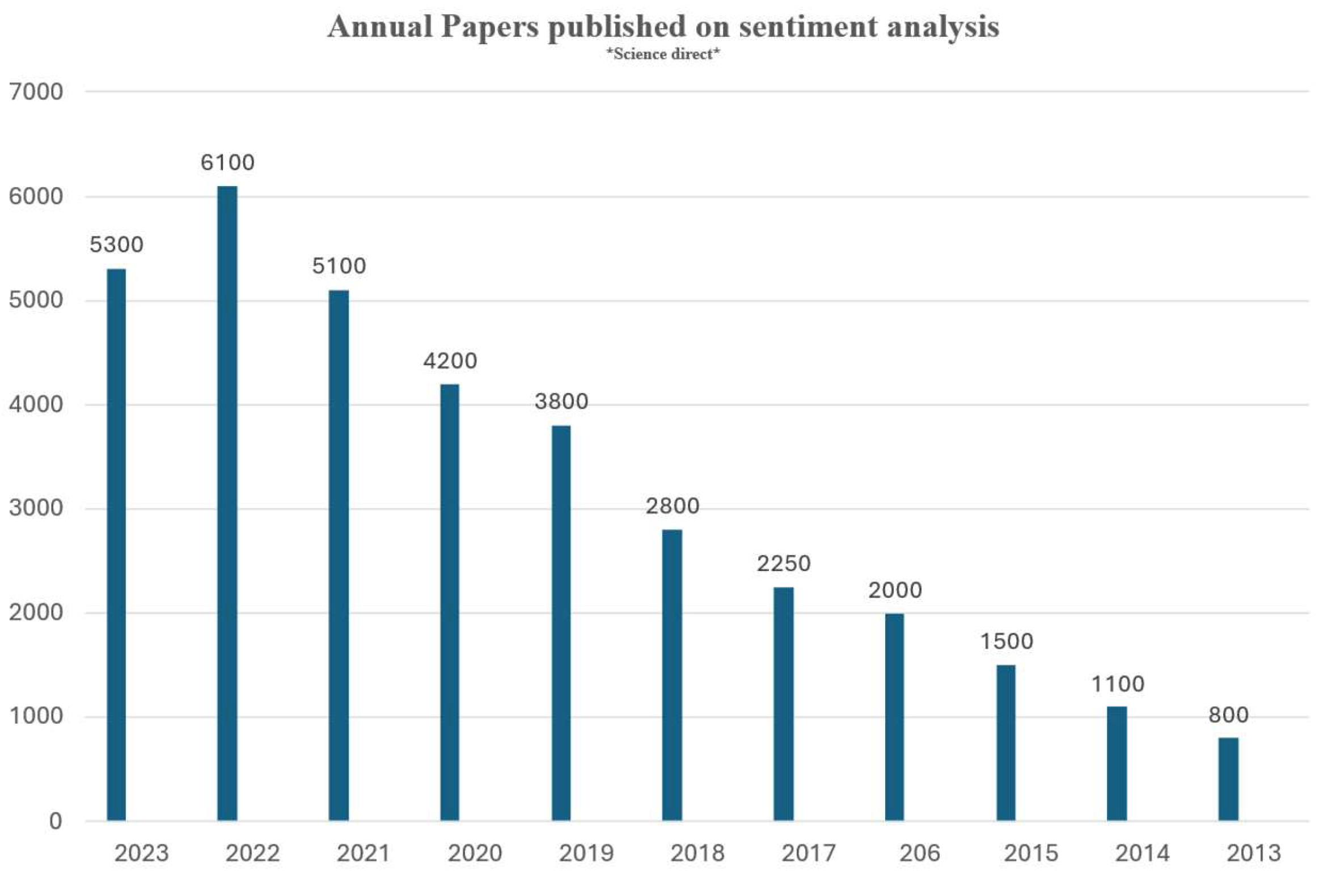

Figure 2.

Bar plot highlighting the increase in the study of fake reviews in literature.

Figure 2.

Bar plot highlighting the increase in the study of fake reviews in literature.

Prior research on fake reviews, reputation management, and digital ethicsThe study of fake reviews began in the early 2000s but has gained prominence since 2019 with the expansion of Online Reputation Management (ORM) services. Research in e-commerce demonstrates how fake reviews distort consumer trust and normalize unethical practices. Within the service sector, especially education (Chandurkar & Tijare, 2021), the consequences are more severe because financial investment is directly tied to long-term career outcomes. Studies on digital ethics emphasize that manufactured trust erodes not only consumer choice but also institutional credibility. Furthermore, research on algorithmic manipulation reveals that ORM agencies often exploit ranking systems, boosting artificial visibility while suppressing genuine dissent.

Recent advances in detection methods: While lexicon-based sentiment analysis (Aung & Myo, 2017) remains a foundational method, of analysis. With the advancement and use of Natural language Processing models has increased, the accuracy of fake review detection. The usage of Bidirectional Encoders Representations from Transformers which can understand the context of words and Long Short-Term Memory networks which can excel at language translation, the accuracy increased. The advantage with these methods over the lexicon method is that they can identify formal words in different regions in India. However, due to availability of tools which can detect fake reviews in regional languages, the exploitation is carried out systematically.

Gaps: Limited focus on India’s coaching industry and its unique socio-cultural dynamics

Although global scholarship provides valuable frameworks, the socio-cultural dynamics of India’s coaching industry remain underexplored. Unlike e-commerce or hospitality, the education sector involves aspirational decision-making by families who may invest a significant proportion of household income (5.78% in urban areas and 3.3% in rural areas). This amplifies the stakes of digital deception. Furthermore, vernacular misinformation and cultural targeting in advertisements exploit local vulnerabilities yet remain largely absent from academic discourse. This study seeks to address this gap by combining sentiment analysis, case study evidence, and policy review to provide a holistic understanding of digital deception in the Indian coaching sector.

3. Methodology

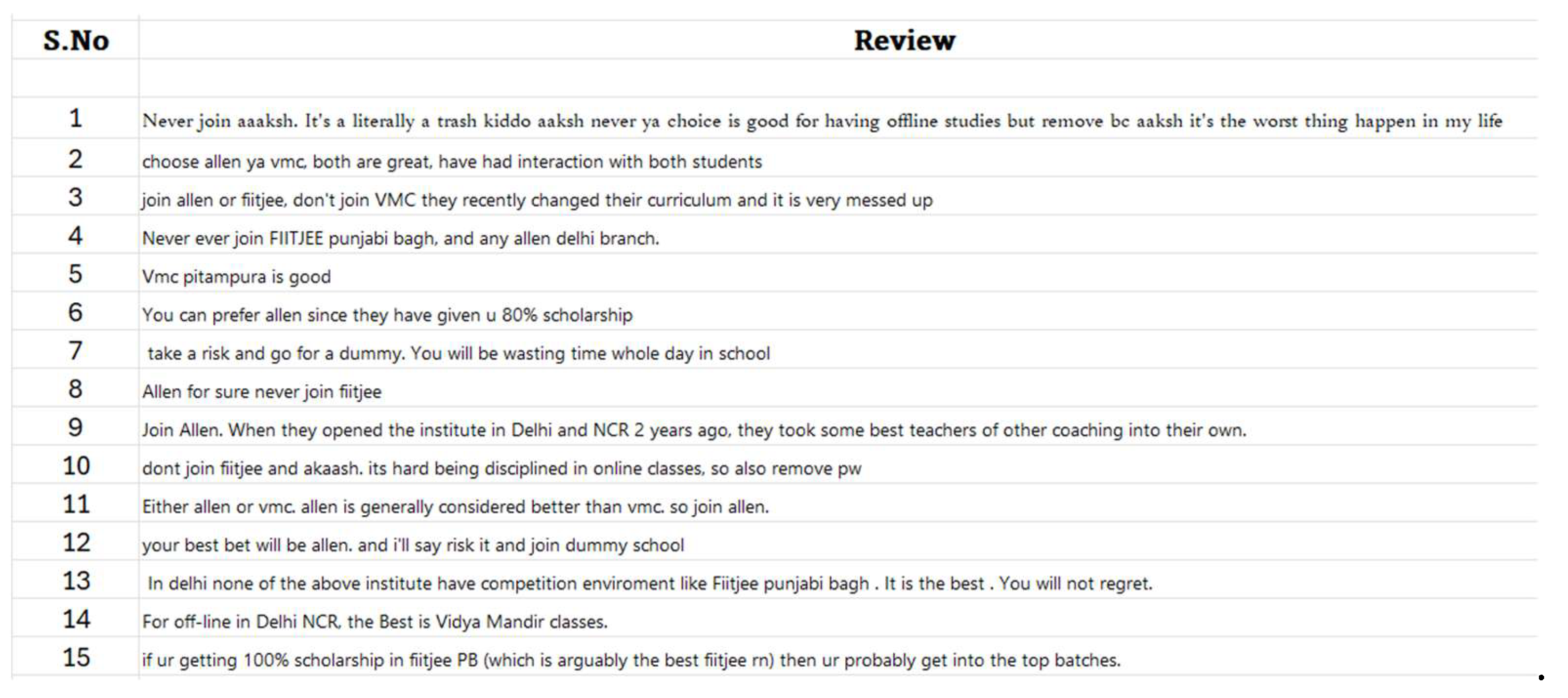

Source of Data: The sample data was collected from discussion forums like Reddit and Quora and for reviews from popular platforms like Facebook and Instagram. Google data of rankings also was collected manually using keywords.

Preparation of Data: In the collected raw data, there were duplicate entries, regional language expressions, usernames and URL.

The following steps were followed for the analysis of data

The above

Figure 3 is sample for uncleaned data.

Preprocessing and cleaning– Reviews were manually cleaned to remove URLs, usernames, redundant information, duplicate sentences, and unnecessary symbols. Informal colloquial expressions and misspelled words were standardized. Stop words were filtered out, and special attention was given to handling negations, as they significantly alter sentiment polarity (e.g., “not good” → negative).

A sample from the sentiment dictionary is shown below:

Table 1.

sample of sentiment dictionary.

Table 1.

sample of sentiment dictionary.

| Word |

Sentiment |

Word |

Sentiment |

| Never |

Negative |

Good |

Positive |

| choice |

Neutral |

Generally considered |

Neutral |

| remove |

Negative |

wasting |

Negative |

| do |

Positive |

mess up |

Negative |

| don’t |

Negative |

Best |

Positive |

| prefer |

Neutral |

Wasting |

Negative |

- 2.

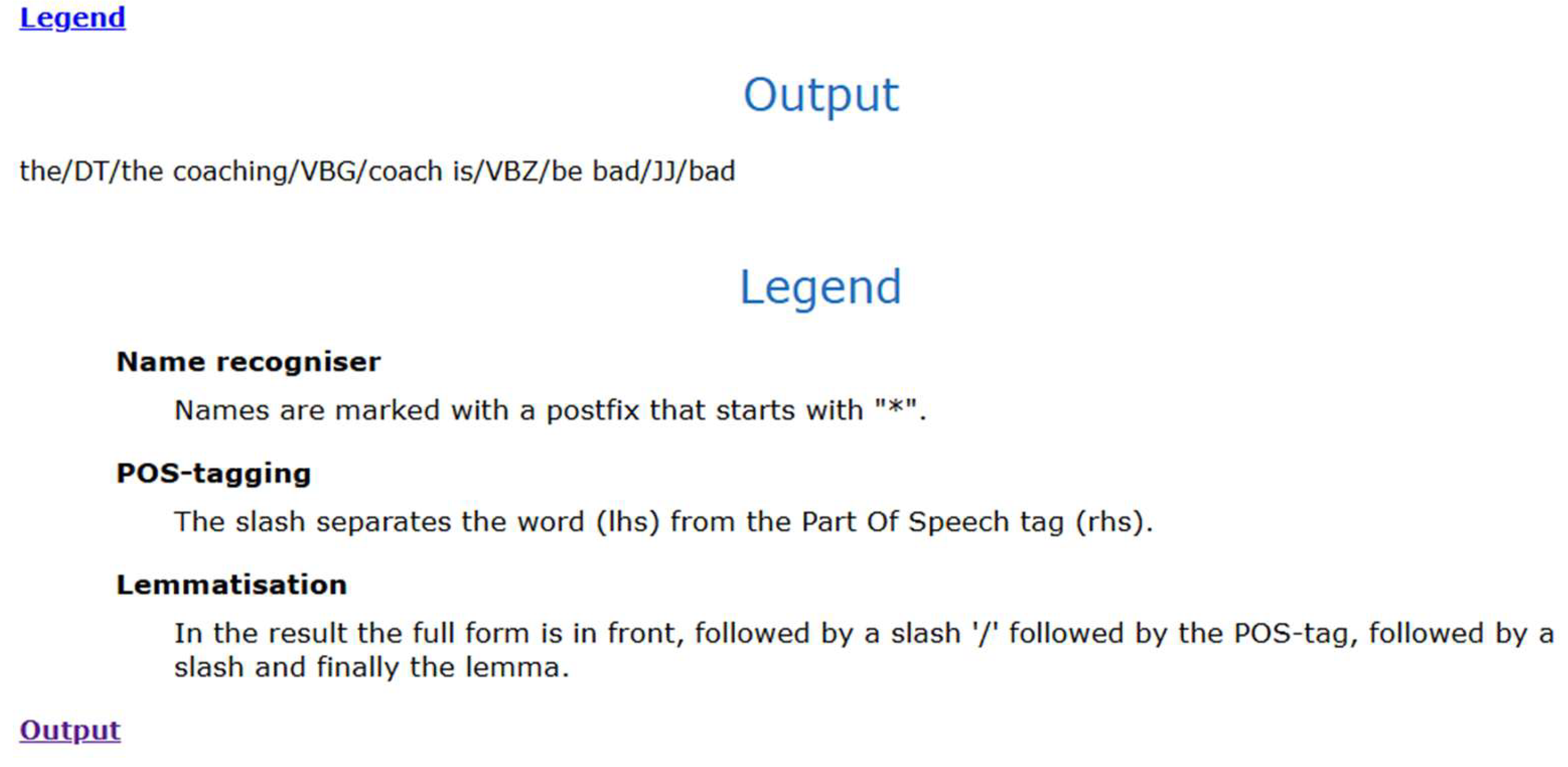

Tools used: “R” programming packages such as textclean and tidytext were employed for preprocessing and sentiment analysis.

- 3.

Lemmatization: Lemmatization was applied for sentiment scoring because it provided higher accuracy than stemming by ensuring that words were reduced to valid root forms found in the dictionary (

Figure 4).

- 4.

Sentiment scoring: Finally, sentiment scores were calculated by comparing the processed reviews with the entries in the sentiment dictionary. The sampled data was categorized as positive, negative, or neutral based on this matching process.

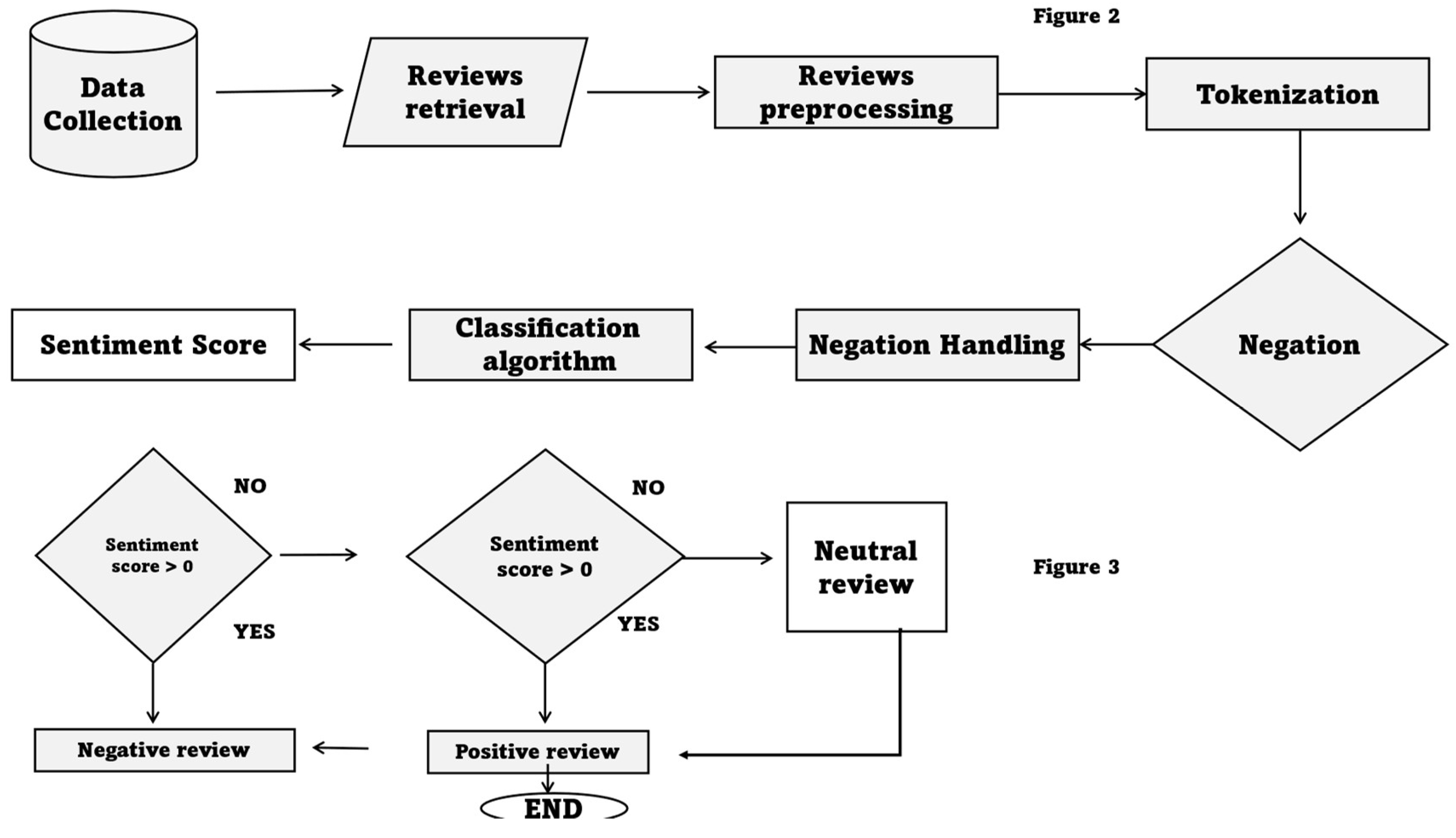

4. Sentiment Analysis Techniques

Standard methodology for the sentiment analyses technique is shown in

Figure 5.

For this study, we adopted a lexicon-based sentiment analysis approach. Predefined dictionaries of positive, negative, and neutral terms were used to rapidly classify reviews. This method was selected for three reasons:

Dataset Size – The dataset of reviews from the coaching industry was relatively small. Supervised machine learning models typically require large, balanced datasets for training, which were not available in this case.

Data Imbalance – The presence of a limited number of fake or deceptive reviews would have posed a high risk of misclassification in machine learning models, which tend to struggle with skewed class distributions.

Rapid Classification – The lexicon approach enabled efficient large-scale classification without the need for extensive manual labeling, making it practical for the exploratory scope of this study.

While more advanced models such as Naïve Bayes, SVM, and deep learning classifiers are widely available, they were not implemented here due to the constraints of dataset size and balance. Instead, the lexicon-based approach provided a transparent, efficient, and contextually sufficient method for analyzing consumer sentiment in the coaching sector.

Case Study Selection: To complement the quantitative sentiment analysis, seven case studies were purposively selected. The inclusion criteria were:

Documented visibility in regional or national media. Each case was coded along four dimensions: (1) type of deception, (2) operational mechanism, (3) consumer impact, and (4) regulatory response. This mixed-methods design provided both statistical patterns and qualitative depth.

Limitations: Despite rigorous preprocessing, certain limitations persist. The foremost being misclassification due to imbalance in the dataset, which has few fake reviews compared to authentic ones. Lexicon-based methods are limited in handling sarcasm, slang, and context-specific sentiment. Furthermore, reliance on publicly available data excludes private or deleted consumer experiences. These limitations highlight the need for adaptive and automated approaches such as transformer-based models (e.g., BERT, LSTM) for improved detection in dynamic domains like education (Mamgain, Mehta, Mittal, & Bhatt, 2016).

5. Mechanisms of Digital Deception:

Digital deception in India’s coaching sector is not a single act but a set of practices that work together. The psychological deception makes students and parents convinced about the narrative of influencer promotions, paid rating, fake reviews and exaggerated claims of success which otherwise do not match the reality.

Fake Ratings and Paid Reviews: Some institutes employ bots or click farms to quickly fill Google or Facebook with five-star ratings. In other cases, students are persuaded to post positive reviews in return for fee concessions, free mock tests, or even extra study material. Parents reading these reviews often believe they represent genuine experiences. The timing is also important: such reviews usually spike when exams or results are announced, because that is when parents are actively searching for the “best” coaching options. In Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities, where reliable information is harder to check, this practice has a stronger effect.

Exaggerated Claims and Doctored Results: Many coaching centre’s exaggerate their performance. For example, one student’s All India Rank may be advertised as if the whole batch achieved that success. Sometimes, fabricated scorecards are circulated, or AIR numbers are claimed without proper statistical proof. In certain cases, even dummy student profiles with AI-generated images or stock photos are used to back these claims. The aim is to create the appearance of credibility, even when actual outcomes are far more modest.

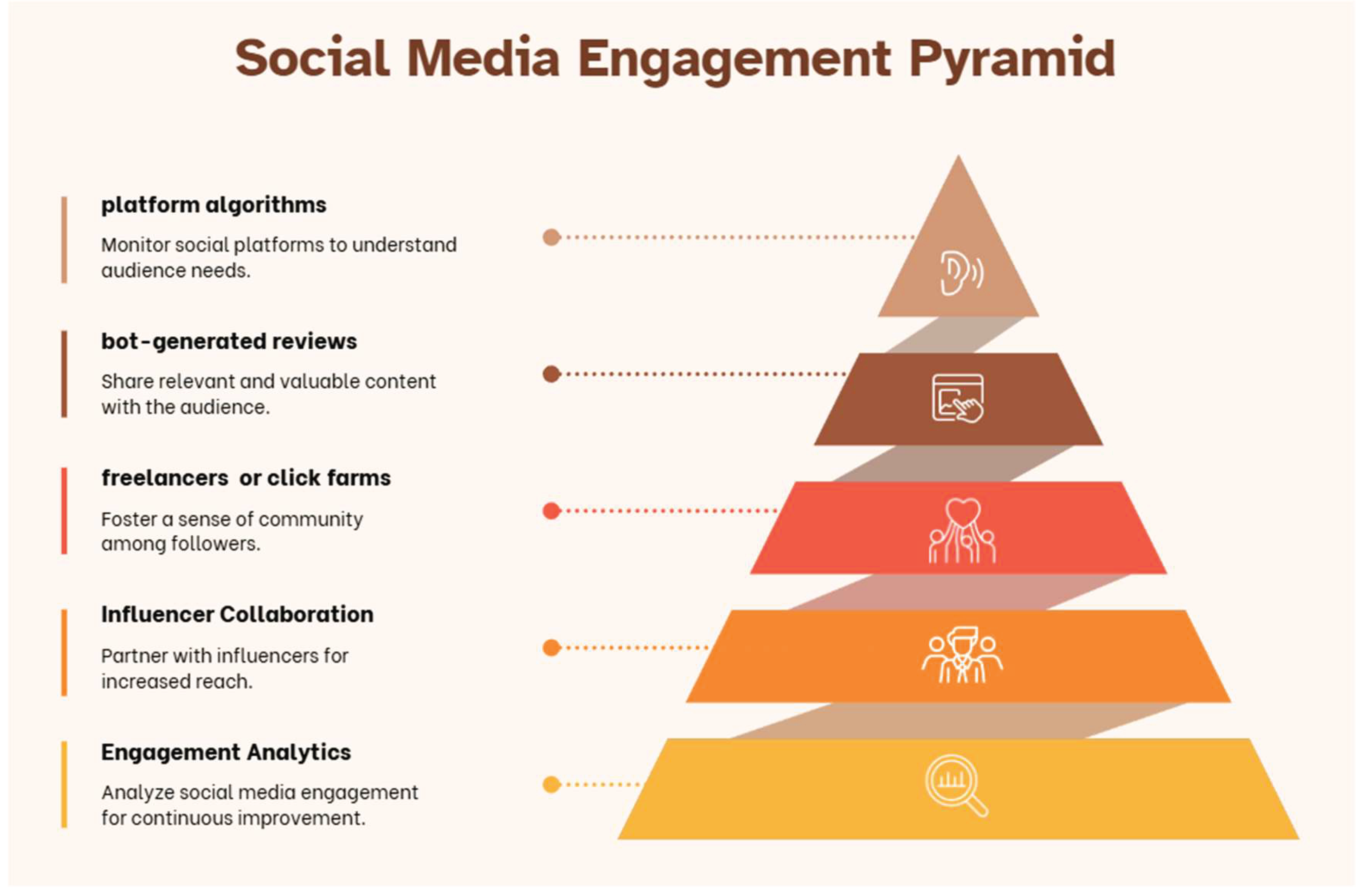

Figure 6.

Social media engagement pyramid.

Figure 6.

Social media engagement pyramid.

Influencer and Media Manipulation: Another strategy is the use of influencers. YouTube, Instagram reels, and short testimonial videos are often paid promotions, though they are rarely marked as such. Celebrities, ex-students, or even hired interns are coached to deliver motivational stories that sound authentic. Larger institutes and EdTech companies sometimes work with Enterprise Marketing (EM) agencies, who bundle “visibility packages” including fabricated reviews, curated testimonials, and top placements in search engines. Smaller coaching centres, without such resources, struggle to compete.

Psychological Exploitation: A big part of digital deception is not technical at all, but psychological. Coaching centers play on very common mental shortcuts that people use when making decisions. Three of these—bandwagon effect, fear of missing out (FOMO), and the halo effect show up again in the way institutes market themselves (Munusamy, Syasyila, Shaari, Pitchan, Kamaluddin, & Jatnika, 2024).

Bandwagon Effect: This is the idea that if many people are doing something, then it must be the right choice. In simple terms, people “join the crowd.” In coaching, parents often think: “If so, many students have enrolled in this institute, then it must be good.” Ratings and testimonials are inflated to reinforce this feeling. The result is that people follow others rather than checking facts on their own.

Fear of Missing Out (FOMO): FOMO is more of an anxious feeling, the worry that one will be left behind if action is not taken quickly. Coaching centers know this. Ads often say things like “last chance for NEET success” or “limited seats for top batches.” In Tier-2 and Tier-3 towns, where families already feel pressure to give their children a fair chance, such messages are even more powerful. Parents rush into decisions out of fear rather than careful judgment.

Halo Effect: This happens when one good feature makes us assume everything else must be good too. In the coaching industry, a single student’s All India Rank (AIR) is sometimes shown as proof of overall excellence. Parents see the ad and believe the whole batch was successful, even though that may not be true. Institutes use this shortcut deliberately because it creates quick trust.

When these three biases work together, they can be very persuasive. A parent who sees high ratings (bandwagon), a warning that seats are running out (FOMO), and a flashy rank-holder in the ad (halo effect) is much more likely to sign up their child without questioning the details. Genuine reviews and experiences then get buried under these louder, more polished messages.

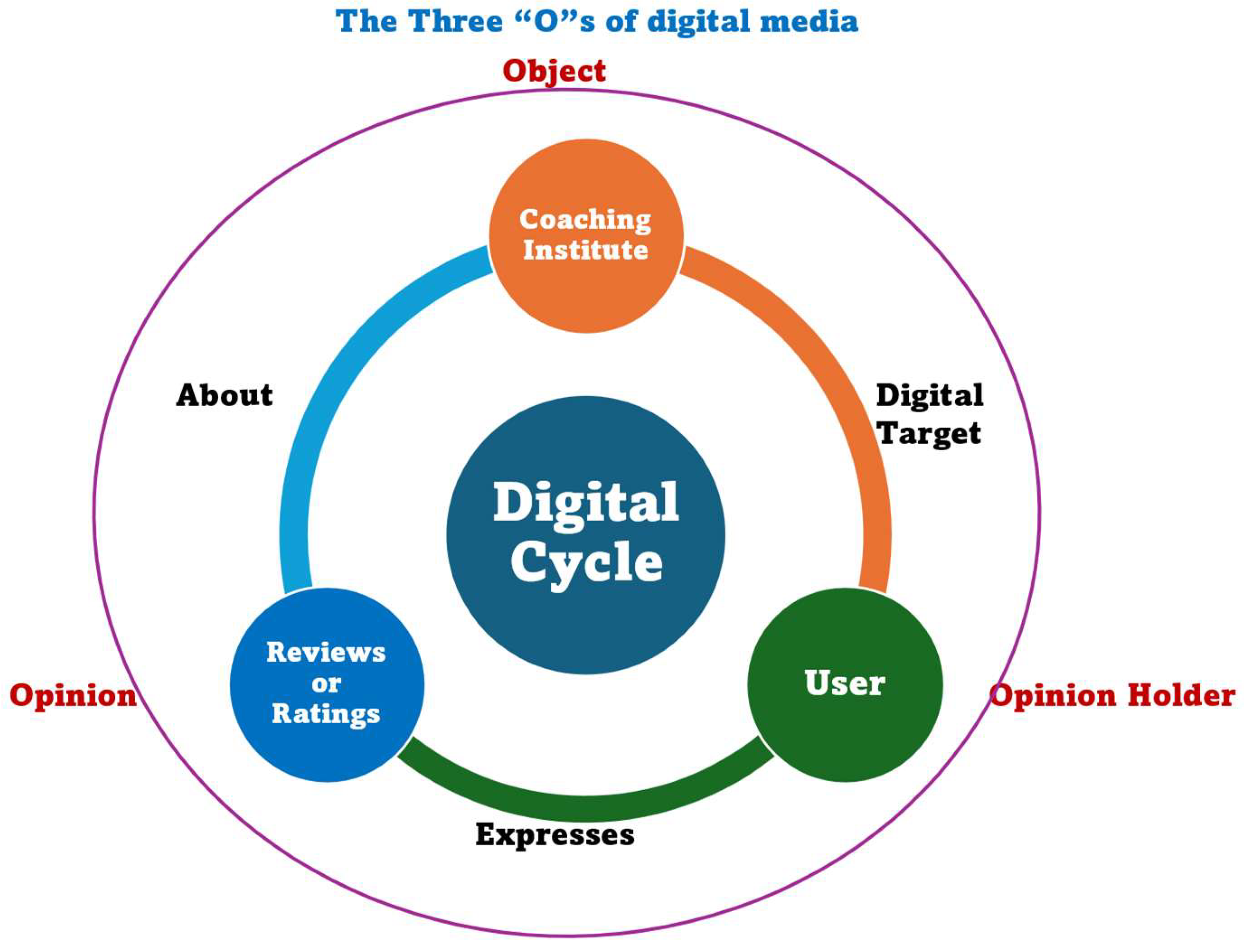

Figure 7.

Digital cycle link between objects, opinion holders, and opinions.

Figure 7.

Digital cycle link between objects, opinion holders, and opinions.

6. Case Studies of Digital Deception in India’s Coaching Sector:

If looked at from broader plane the psychological clamping on the three ‘O’ of the digital space which impacts the students is tremendous. To complement the sentiment analysis, we examined seven case studies that illustrate how deception operates in practice. These cases were chosen because they had visibility in media or consumer complaints, showed clear evidence of digital manipulation, and represented different types of malpractices. Together, they highlight both the creativity of coaching centers in marketing and the vulnerabilities of students and parents.

Case 1: Misleading Advertisements (Halo Effect): A coaching institute released one of the most misleading advertisements (Tap-a-gain, n.d.) of the year, portraying a single student’s success as if it were the achievement of the entire batch. This played directly into the halo effect, where one positive outcome is projected as proof of overall excellence. The advertisement created manufactured trust, even though no statistical validation was provided.

Case 2: Bot-Generated Reviews: On platforms like Google and Facebook, reviews often appeared overnight in large numbers. Threads on Quora and Reddit (Reddit, n.d.) showed glowing testimonials that were clearly scripted, sometimes posted by accounts with stock profile photos and inconsistent timelines. This created an artificial reputation boost, particularly around IIT-JEE coaching, where emotional aspirants were more likely to believe such digital voices.

Case 3: Fake “AIR rank” Claims in JEE: Perhaps the most striking example came from a JEE coaching institute that advertised (IIT JEE Pune Wellwishers, 2011) a student as having secured All India Rank. Closer examination revealed the claim was false. Yet the advertisement was powerful enough to sway anxious students and parents, many of whom equated enrolment with guaranteed success. This is a direct case of psychological manipulation through fabricated achievements.

Case 4: Identity Forgery: (NEET Coaching): Several NEET institutes in India were caught claiming the same rank. Photos of topper reposted as their own students’ results (Reddit, n.d.). Close monitoring of the discussions shows dissent on these institutes. On the contrary, you don’t see the same dissent voices on their official platform. When challenged, the groups deleted messages and blocked dissenters, exploiting the fleeting nature of messaging platforms.

Case 5: Misrepresentation Fined by Regulators (IIT-JEE Coaching, Delhi) A prominent coaching center in Delhi (Business Standard, n.d.) was fined by regulators for claiming inflated admission results. The institute advertised “large numbers of IIT admissions” but failed to clarify whether these were actual admissions or only qualifying ranks. The Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI) and other bodies issued 46 notices to 24 institutes for similar misrepresentations, showing that regulatory action, though limited, is beginning to catch up.

Table 2.

summary of case studies.

Table 2.

summary of case studies.

| Case No. |

Type of Deception |

Coaching Segment |

Location |

Mechanism / Method |

Psychological Bias Exploited |

Key Outcome / Impact |

| 1 |

Misleading Advertisements |

General |

India |

Single student’s success advertised as entire batch achievement |

Halo Effect |

Manufactured trust; inflated perception of overall quality |

| 2 |

Bot-Generated Reviews |

IIT-JEE |

Delhi |

Scripted reviews, fake profiles on Google/Facebook |

Bandwagon Effect |

Artificial reputation boost; misled aspirants |

| 3 |

Fake AIR Claims |

IIT JEE |

Pune |

Unverified rank advertised as AIR |

FOMO, Bandwagon Effect |

Students/parents influenced to enrol; psychological manipulation |

| 4 |

Identity Forgery |

NEET |

North India |

Same Topper for all Institutes. |

FOMO, Local Trust Bias |

Exploited local community trust; doctored success narratives |

| 5 |

Misrepresentation Fined by Regulators |

IIT-JEE |

Delhi |

Inflated admission claims: regulator notices issued |

Halo Effect, Bandwagon Effect |

Regulatory fines issued; public awareness raised, but enforcement limited |

Patterns from the Case Studies:

Across these cases, a common pattern emerges: Techniques range from fake advertisements, bot-generated reviews, and doctored results to influencer-driven deception and identity forgery.

Psychological biases such as the halo effect, FOMO, and bandwagon effect amplify the impact of these strategies. Regional vulnerability is higher in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities, and in vernacular-language marketing, where families have fewer means of verification.

While these cases may appear as isolated marketing tricks, together they show a systematic attempt to exploit digital platforms, manipulate perceptions, and erode consumer trust in education.

7. Results and Analysis

Table 3.

sample results of sentiment classification.

Table 3.

sample results of sentiment classification.

| 1 |

Never join Aakash. It's literally a trash kiddo Akash never ya choice is good for having offline studies but remove bc aaksh it's the worst thing happen in my life |

Negative |

| 2 |

choose Allen ya vmc, both are great, have had interaction with both students |

Positive |

| 3 |

join Allen or fiitjee, don't join VMC they recently changed their curriculum, and it is very messed up |

Negative |

| 4 |

Never ever join FIITJEE punjabi bagh, and any Allen Delhi branch. |

Negative bias |

| 5 |

Vmc Pitampura is good |

Positive |

| 6 |

You can prefer Allen since they have given u 80% scholarship |

Positive |

| 7 |

take a risk and go for a dummy. You will be wasting time whole day in school |

Negative |

| 8 |

Allen for sure never join fiitjee |

Negative bias |

| 9 |

Join Allen. When they opened the institute in Delhi and NCR 2 years ago, they took some best teachers of other coaching into their own. |

Positive |

| 10 |

dont join fiitjee and akaash. it’s hard being disciplined in online classes, so also remove pw |

Negative bias |

| 11 |

Either allen or vmc. allen is generally considered better than vmc. so, join allen. |

Positive |

| 12 |

your best bet will be allen. and i'll say risk it and join dummy school |

Negative |

| 13 |

In delhi none of the above institute have competition enviroment like Fiitjee punjabibagh. It is the best. You will not regret. |

Negative |

| 14 |

For off-line in Delhi NCR, the Best is Vidya Mandir classes. |

Positive |

| 15 |

if ur getting 100% scholarship in fiitjee PB (which is arguably the best fiitjee rn) then ur probably get into the top batches. |

Positive |

8. Sentiment Analysis Findings:

A sentiment analysis was conducted on over 1,600 online reviews of major coaching institutes in India, categorizing them as positive, negative, or neutral. Nearly half of the reviews (46.6%) were positive, suggesting apparent satisfaction among students. Positive feedback often highlighted experiences with faculty or scholarship opportunities, as seen in comments like, “choose Allen or VMC, both are great” or “VMC Pitampura is good.” However, numerous negative reviews revealed dissatisfaction with aspects such as curriculum changes, online class management, and perceived organizational inefficiencies. Some comments exhibited strong negative bias toward specific institutes, for instance, “Allen for sure, never join FIITJEE”.

While nearly half of reviews were positive, a closer examination revealed a mismatch between sentiment and engagement, suggesting that public ratings may not fully represent genuine student experiences.

Engagement Mismatch: Followers vs. Reviews: Analyzing metrics of the official channels of some of the top-notch coaching institutes a visible mismatch between the reviews of users and their sentiment on their channels and total number of followers or users. Yet, many institutes with large follower bases showed low volumes of authentic, organic reviews. Smaller institutions, conversely, displayed higher engagement relative to their digital footprint. This discrepancy suggests the presence of dormant accounts, artificial likes, or paid followers, indicating that online popularity does not necessarily reflect genuine reputation or teaching quality.

Patterns Across Platforms: Platform-specific analysis further highlights the deliberate curation of content. Independent discussion forums often feature mixed opinions, with parents and students criticizing misleading advertisements, inflated ranks, and so-called dummy schools. But on the official social media channels, negative reviews were notably absent. Only positive testimonials, success stories, and promotional content were actively highlighted. Google reviews, while mostly positive, keywords related to teaching quality persisted, showing selective amplification of favourable feedback.

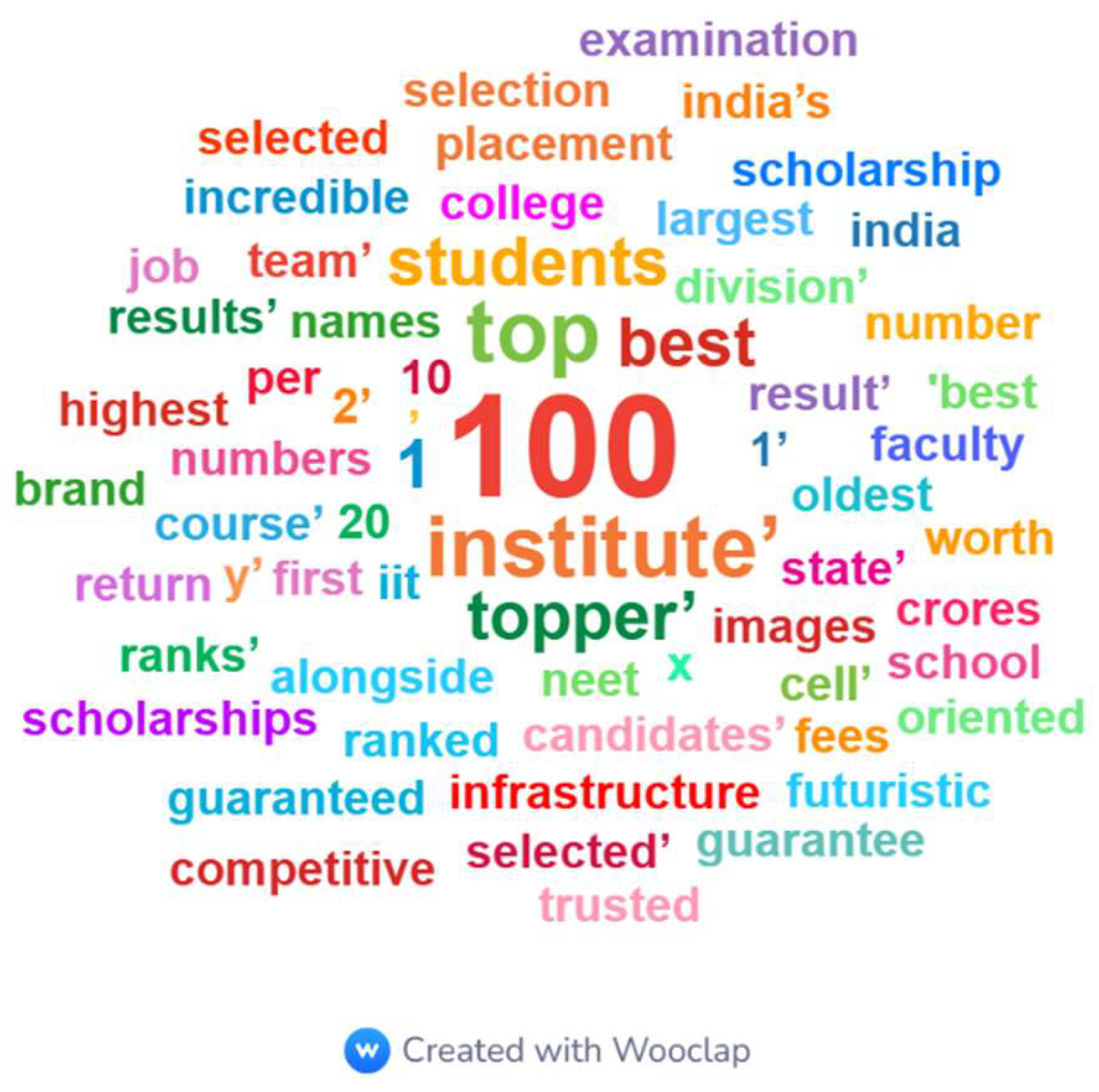

Analysis of digital content demonstrates the deliberate use of psychological triggers, particularly the

“Fear of Missing Out” (FOMO).

Figure 8 demonstrates the word cloud of the common terminologies aimed at creating urgency and prestige. These include:

“IIT Topper,” “NEET Topper,” “100% Result,” “No.1 Institute,” “Top 10 Institute,” “Guaranteed Selection” Scholarship-related claims: “, 100% scholarship to top 100 students,” “Scholarships Worth 20 Crores” Promises of exclusivity and infrastructure: “Best futuristic school of India,” “Largest Faculty Team,” “Best Placement Cell.”

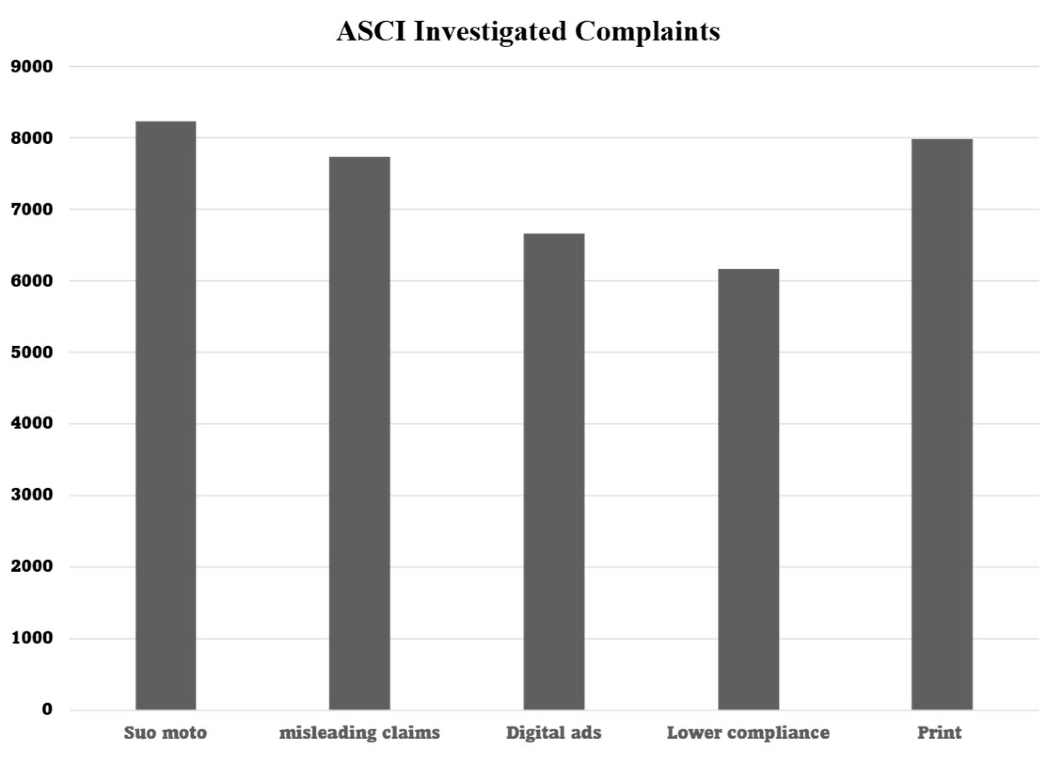

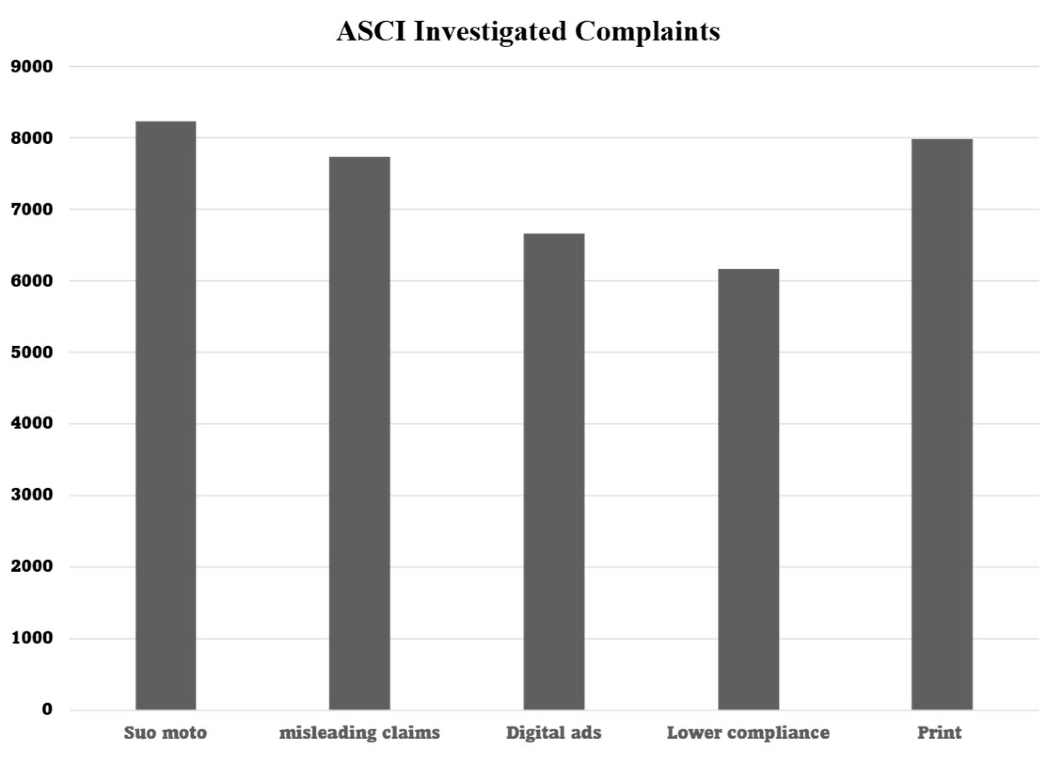

9. Regulatory Insights:

The Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI) (ASCI Agm-report-20-Aug-2024) investigated 10,093 complaints, analysing 8,299 advertisements (

Figure 9). N 0.3% Mobile App 0.2% E-Commerce 42% Instagram 9% YouTube 30% Websites 17% Facebook 1% MAT Bulletin /E-Mailer /Google Ad Word. And 0.1% LinkedIn. During pandemic and in post pandemic there is an enormous increase in influencer marketing, for the EdTech companies, which unfortunately have been one of the most violated categories. Many players in the market are targeting vulnerable students and parents.

Among 142 ads processed 81 reflected noncompliance with influencers not disclosing their brand collaborations on social media. 140 of the ads were misleading and required modification. 91 of these ads were not contested. 139 of these ads featured on digital medium. The unrealistic claims and exaggerated promises clubbed with curated positive narratives suppress the real facts. Such practices reinforce misleading reviews and ratings, perpetuating a cycle of digital deception in the coaching sector.

Figure 9.

Distribution of complaints on various platforms *source: ASCI*.

Figure 9.

Distribution of complaints on various platforms *source: ASCI*.

Discussion: The consumers right to informed choice is compromised and overshadowed by the digital malpractices which coerces parents and students to make costly irreversible decisions. As a result, the consumer trust erodes, undermining the fair play policy, favouring manipulative marketing and overshadows credible genuine service providers creating systemic inequalities. These reviews are taken as feedback as a primary trust building tool and the lexemic susceptibility of wide-eyed consumers is exploited. This also deepens the digital divide and has a far-reaching socio-economic implication. The families often invest a higher share of household income in education.5.78% of total income in urban areas and 3.3% of total income in rural areas (Varthana, n.d.).

The digital platform algorithms are vulnerable to incentivized five-star ratings, bot generated content and feedback. The platform ranking system worsens the problem, allowing paid reviews or sponsored ads suppressing authentic voices. The fraudulent content is allowed to flourish before it is detected or flagged.

Fake reviews and fraudulent practices are dealt stringently in various countries. In Europe the regulatory body mandates transparency, accountability in the feedback mechanism and trackability. In the United States guidelines to prevent deceptive endorsements and the penalties levied are practiced. We in India require a regulatory body who can initiate the guidelines, enforce to plug the gap in governance especially in education sector and deal stringently with the penalties levied.

10. Recommended framework:

The existing challenges and gaps can be addressed with a legal framework and regulatory body which integrates technical, ethical and awareness driven interventions is required to address the challenges of fake ratings and paid reviews.

Technological: AI-based fraud detection, KYC-linked reviews, centralized audit systems. The technical body should utilize AI based fraud detection systems, which can identify patters of sudden increase in ratings, identify anomalies in reviews, bot generated activity, and linguistic styles. The reviews can be linked by utilizing mobile linked OTP mode to ensure accountability of feedback contributors. In addition, the regulatory body should conduct a digital audit periodically to cross check to reduce the manipulation.

Ethical: Mandatory disclosure of paid promotions. The coaching centres or institutes and online reputation management service organizations should follow the norms of mandatory disclosure of paid promotions. This will ensure transparency which will align with global practices and distinguish between authentic reviews and marketing driven endorsements.

Regulatory: Stronger penalties, proactive monitoring, collaboration with ASCI. The regulatory body should collaborate with Advertising standards council of India (ASCI) for introduction of more stringent penalties for institutes engaging in deceptive reviews and manipulative advertisements. By collaboration, standard for best practices can be set.

Awareness: Consumer education programs for parents/students. The most challenging is to bridge the gap between the urban rural misinformation gap. Regular education programs specially for Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities can enhance digital literacy programs helping them to recognize red flags in online reviews.

11. Conclusion

This study focuses on how a manipulated advertisement of coaching institute or its services, or the results claimed for high stake exams like UPSC, JAM, CAT, IIT-JEE, NEET etc., influence the decision making by digital clamping of consumer trust. The study also highlights the vulnerability of the digital reputation and their presence vying for consumer trust. The main contribution is the combining of sentiment analysis with real time case analysis and policy perspective leading to a multidimensional view of the issue. The identification of algorithmic loopholes which enables the fraudulent practices but within a regulatory and ethical framework. The study emphasises the need for more resilient digital ecosystems in education.

One of the limitations in the study is the small data set on which the analysis was based and may limit the generalized findings. Therefore, the lexicon-based sentiment analysis was used for rapid classification instead of ML models that would require large datasets. Looking ahead, the future work should be focussing on expansion of the data set which can incorporate linguistic contexts including vernacular reviews across platforms. Comparative studies for fraud detection with international collaboration would provide global insights and set benchmarks for policies in India. Hybrid transformers architecture, BERT, LSTM could enhance the detection of fraudulent cases.

References

- Mite-Baidal, K. , Delgado-Vera, C., Solís-Avilés, E., Espinoza, A. H., Ortiz-Zambrano, J., & Varela-Tapia, E. (2018, October). Sentiment analysis in education domain: A systematic literature review. In International conference on technologies and innovation (pp. 285-297). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Kwek, C. L. , Lei, B., Leong, L. Y., & Peh, Y. X. (2020, June). The Impacts of Online Comments and Bandwagon Effect on the Perceived Credibility of the Information in Social Commerce: The Moderating Role of Perceived Acceptance. In 8th International Conference of Entrepreneurship and Business Management Untar (ICEBM 2019) (pp. 451-460). Atlantis Press.

- Molina, M. D. , Wang, J., Sundar, S. S., Le, T., & DiRusso, C. Reading, commenting and sharing of fake news: How online bandwagons and bots dictate user engagement. Communication Research 2023, 50, 667–694. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, A. , Hollenbeck, B., & Li, Z. (2024). Misinformation and Mistrust: The Equilibrium Effects of Fake Reviews on Amazon. com, Working Paper.

- Munusamy, S. , Syasyila, K., Shaari, A. A. H., Pitchan, M. A., Kamaluddin, M. R., & Jatnika, R. Psychological factors contributing to the creation and dissemination of fake news among social media users: a systematic review. BMC psychology 2024, 12, 673. [Google Scholar]

- Emre, İ. E. , & Köse, G. G. (). UNDERSTANDING FEAR OF MISSING OUT PHENOMENA AND SOCIAL MEDIA USING BIBLIOMETRIC ANALYSIS (2013-2023). Öneri Dergisi 2025, 20, 197–225. [Google Scholar]

- Gullipalli, V. S., & Dholey, M. K. (n.d.). Sentiment analysis of colleges in India. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET), 11(03).

- Chandurkar, T. , & Tijare, D. P. (2021). Sentiment analysis: A review and comparative analysis on colleges. International Journal of Scientific Research in Computer Science, Engineering, and Information Technology, 526-531.

- Kandhro, I. A. , Wasi, S., Kumar, K., Rind, M., & Ameen, M. Sentiment analysis of students’ comment using long-short term model. Indian Journal of Science and Technology 2019, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Aung, K. Z. , & Myo, N. N. (2017, May). Sentiment analysis of students' comment using lexicon-based approach. In 2017 IEEE/ACIS 16th international conference on computer and information science (ICIS) (pp. 149-154). IEEE.

- Mamgain, N. , Mehta, E., Mittal, A., & Bhatt, G. (2016, March). Sentiment analysis of top colleges in India using Twitter data. In 2016 international conference on computational techniques in information and communication technologies (ICCTICT) (pp. 525-530). IEEE.

- https://www.ascionline.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/agm-report-20-Aug-2024.pdf.

- Varthana. (n.d.). Dissecting private educational expenditures in Indian households.https://varthana.com/school/dissecting-private-educational-expenditures-in-indian-households/.

- Rajesh, N. , & Ramachandra, A. C. (2023, November). Fake reviews detection based on sentiment analysis using ml classifiers. In 2023 International Conference on Ambient Intelligence, Knowledge Informatics and Industrial Electronics (AIKIIE) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Kauffmann, E. , Peral, J., Gil, D., Ferrández, A., Sellers, R., & Mora, H. A framework for big data analytics in commercial social networks: A case study on sentiment analysis and fake review detection for marketing decision-making. Industrial Marketing Management 2020, 90, 523–537. [Google Scholar]

- Tap-a-gain. (n.d.). Narayana advertisement controversy: Misleading ads in India. https://tap-a-gain.com/narayana-advertisement-controversy-misleading-ads-india/.

- https://www.reddit.com/r/JEENEETards/comments/1gmeix2/which_institute_to_join/.

- IIT JEE Pune Wellwishers. (2011, ). IIT JEE Pune fake results by coaching institutes. https://iitjeepunewellwishers.wordpress.com/2011/08/05/iit-jee-pune-fake-results-by-coaching-institutes-2/. 5 August 2011.

- Reddit. (n.d.). The same girl studied at three coaching institutes. https://www.reddit.com/r/india/comments/xdvzia/the_same_girl_studied_at_three_coaching/.

- Business Standard. (n.d.). IITPK fined for misleading IIT-JEE results advertisements. https://www.business-standard.com/india-news/iitpk-fined-misleading-iit-jee-results-ads-125021400896_1.html.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).