1. Introduction

Antlers are developed in most species of deer, normally produced only by males, and are composed of rapidly growing solid tissue that initially forms from cartilage and later transforms into bone [

1]. Antlers are not permanent structures; they regrow every year, and their size and shape reflect the animal’s age, health, and genetic fitness.

Genetic analysis of antler samples holds significant potential across various fields, including conservation, forensics, biomedicine, and the study of ecological and evolutionary dynamics in deer populations, as well as prehistoric and ancient research [

2]. With advancements in DNA extraction techniques, the study of antlers has deepened our understanding of species’ genetic structure (

Table S1). Early studies focused on mitochondrial DNA from Giant deer (

Megaloceros giganteus) specimens, demonstrating the utility of antlers in recovering historical genetic data and contributing to phylogenetic analysis [

3]. Other research extracted nuclear DNA microsatellites from older, museum-preserved antlers, enabling multi-generational ecological studies [

4,

5]. Lopez and Beier (2012) further showed that naturally shed and weathered antlers can retain usable DNA over time, making them valuable for both historical and contemporary population studies [

6]. Antlers also play a role in forensic genetics, particularly in individual identification, allowing for comparisons with registered trophies and aiding in the detection of illegal hunting activities [

7]. In biomedical research, antlers serve as models for rapid mammalian growth and cartilage formation, with studies highlighting the role of epigenetic regulation in cartilage differentiation [

8]. Research on sika deer (

Cervus nippon) has examined the role of the osteopontin gene in tissue development, while investigations into velvet antler growth underscore its biomedical and economic significance [

8,

9,

10]. In traditional Asian medicine, deer products—such as antlers, meat, skin, and bones—remain highly valued. However, the high market demand has led to counterfeit products, often mixed with tissues from other animals (e.g., pigs, cows, sheep). DNA barcoding has proven effective in verifying the species origin of these products, including antlers [

11,

12]. Furthermore, for RNA-based transcriptomic studies on rapid growth and annual regeneration, antler velvet and mesenchyme tissues provide reliable sources [

13,

14].

DNA extraction and purification are essential steps in various scientific disciplines, and the primary goal is to obtain pure, high-quality DNA suitable for downstream applications such as PCR, microarray technologies, and sequencing. Studies involving bone tissue—including antlers—have shown that using liquid nitrogen in combination with bone mills can improve DNA yield by preserving DNA integrity [

15]. Successful extraction and subsequent STR genotyping or mitochondrial gene sequencing from red deer (

Cervus elaphus) and sika deer antlers have typically relied on this approach [

4,

12]. However, these tools are expensive and often unavailable in basic laboratory settings. For more accessible and preservation-friendly sampling, Venegas et al. (2020) compared multiple DNA extraction techniques for antler tissue [

16]. While all methods were suitable for mitochondrial gene sequencing, they required a large quantity (10 g) of connective tissue. Most studies used either phenol-based extraction or silica column-based methods. The latter was favored for fresher samples, such as velvet antlers or antler tips, and sometimes used in combination with phenol extraction (

Table S1). Although silica column-based techniques are non-toxic and commonly used, they generally produce high yields only when (1) large amounts of fresh, non-ossified tissue are available, and (2) a bone mill is used. And while the exact extraction protocol is available in most of these publications, data on the quantity and quality of the extracted DNA are mostly missing.

In this study, we aimed to develop an organic DNA extraction protocol for antlers that eliminates the need for a bone mill, liquid nitrogen, or lengthy decalcification, while still providing sufficient DNA yield and quality. We tested the method on three deer species, roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), fallow deer (Dama dama), and red deer (Cervus elaphus), all of which are ecologically and forensically important. Notably, there are currently no genetic studies based on antler samples for roe or fallow deer. We also assessed the applicability of our method on antlers and antler pedicles from skulls across these species, and in a real ongoing case regarding the violation of hunting rules.

Case study

In early 2025, a red deer stag was mistakenly harvested in the Transdanubian region of Hungary after having recently shed its antlers. Under Hungarian hunting regulations, antlerless stags are not permitted to be taken. Believing the animal to be a female, which was legally huntable at the time, the hunter shot the deer. Upon discovery, the animal was identified as a male, resulting in sanctions by the Hungarian hunting authority.

As per national practice, the hunting fee is calculated retrospectively based on the trophy weight (skull and antlers). Since no antlers were present, the local hunting association imposed the legally defined game management fee for an antlerless stag (approximately €2.500). The hunter subsequently located one of the shed antlers near the hunting site and requested a genetic analysis to confirm if the antler and skull belonged to the same individual. If confirmed, the estimated full trophy weight could be used to calculate the fee based on standard trophy pricing, potentially greatly reducing the amount owed under game management regulations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

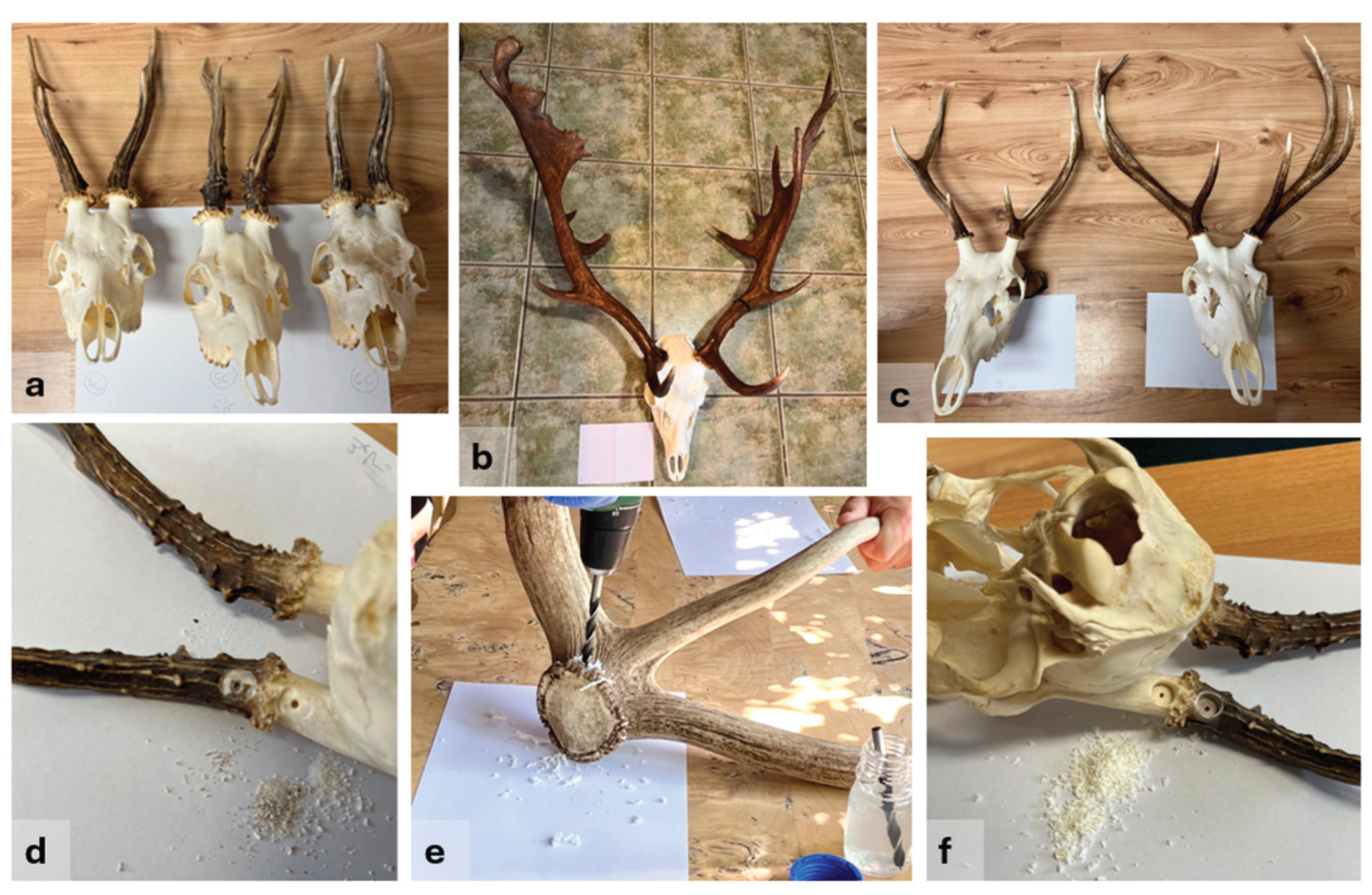

Trophies (skull with antlers,

Figure 1a–c), prepared by boiling in water and treated with a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution, were obtained from private hunters and hunting associations. A total of 29 trophies (harvested within the last 30 years) and two separate antlers were available, originating from 10 roe deer (

Capreolus capreolus), 11 red deer (

Cervus elaphus), and 11 fallow deer (

Dama dama, nine trophies and two antlers). Two samples were taken from each trophy, one from the antler and one from the pedicle part, so a total of

n = 60 samples were tested (

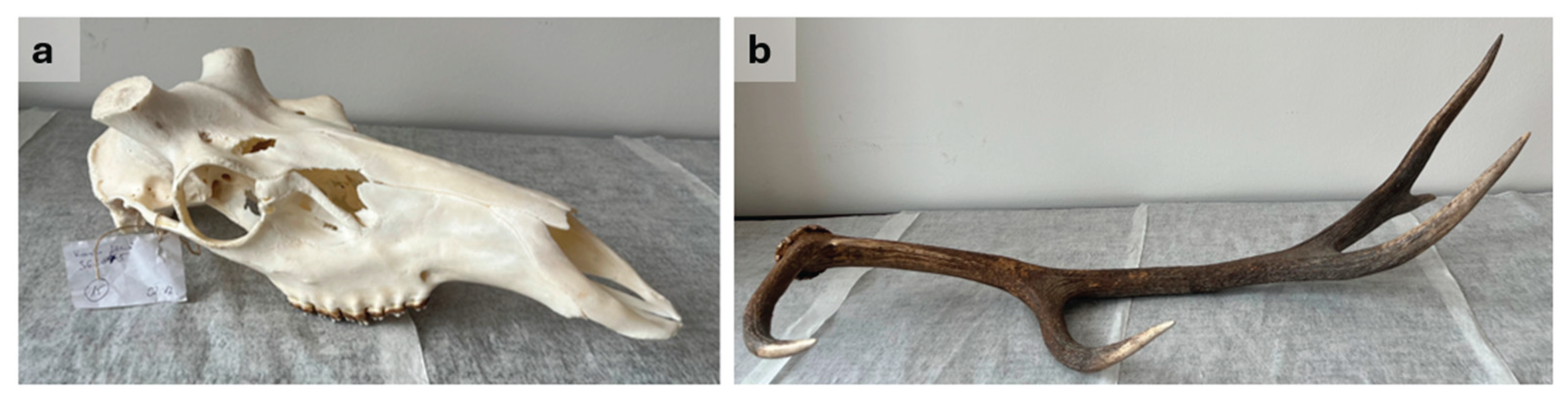

Table 1). In addition, two case-type samples—a prepared red deer trophy skull and an antler beam—were provided for genetic analysis by an official judicial expert in wildlife damage (

Figure 2). The preliminary hypothesis was that the antler may have originated from a slaughtered red deer stag, necessitating a comparative genetic study.

To remove surface contamination, the sampling area was first abraded with emery paper. After drilling through the surface, the top layer of the antler was discarded (

Figure 1d). Shavings were then collected from both the antler base (just above the burr) and the antler pedicle using a sterile 8 mm drill bit (

Figure 1e–f). To avoid visible damage, drilling was carried out on the backside of the trophy, using a low rotational speed to minimize heat generation and thereby preserve DNA integrity. The drill penetrated approximately 0.5 cm deep, avoiding the deeper bone marrow. Between each sampling, the drill bit was disinfected with BIB forte eco (Alpro Medical GmbH), an instrument disinfectant that provides effective decontamination without causing corrosion.

2.2. DNA Extraction

Homogenization of the shavings was performed using a TissueLyser LT (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany), a bead-based mechanical disruptor. To minimize heat buildup, the tube adapter was pre-cooled in a freezer for approximately 15 minutes before use and then loaded with 2 mL U-bottom Eppendorf tubes, each containing 0.1 g of antler shavings and a 5 mm stainless steel bead. The instrument was set to 50 Hz for 1.5 minutes to achieve a fine powder from the antler shavings.

After removing the beads, powdered antler and pedicle materials were decalcified and digested. The extraction buffer consisted of 600 µL 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8), 60 µL 0.5% N-lauryl sarcosine, and 20 µL Proteinase K solution (PCR grade, 20 mg/mL; ThermoFisher Scientific, Bioscience Ltd, Budapest, Hungary). Tubes were incubated in a thermo-shaker at 50℃ and 900 rpm (revolutions per minute) for two hours, followed by an additional two hours at 56℃ and 900 rpm with an additional 20 µL of Proteinase K solution (20 mg/mL).

The extracted DNA was then purified and concentrated using a modified “organic/dialysis” method. Six hundred µL of Ultrapure™ phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (ThermoFisher Scientific, Bioscience Ltd, Budapest, Hungary) was added to the digested solution. After vortexing for 30 seconds and centrifugation for 5 minutes at 13,000 rpm, the supernatant was transferred to a sterile 2 mL Eppendorf tube, and the extraction process was repeated. Microcon®-100 centrifugal filter units (Merck Millipore, Merck Ltd., Budapest, Hungary) were used for purification and concentration of the extract. Filter units were pre-moistened with 100 µL Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer. The washing process was performed with TE buffer and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 20 minutes until the wash buffer had completely passed through the filter. This process was repeated three times. Finally, purified DNA was recovered in 40 µL of TE buffer, and its quality was assessed on agarose gel using GelRed™ Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Biotium, Inc., Izinta Kereskedelmi Ltd., Budapest, Hungary). The DNA concentration of each sample was measured using two methods, a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies Corporation, Biocenter Ltd., Szeged, Hungary) with the dsDNA Broad Range Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Bioscience Ltd., Budapest, Hungary), and with a Nanodrop OneC Microvolume UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Bioscience Ltd., Budapest, Hungary). DNA isolates were also tested with the Nanodrop assay for protein purity (A260/280) and organic compound-related purity (A260/230), and the results were statistically analyzed with respect to species and sample type.

2.3. Statistical Analyses of DNA Concentration and Purity

All statistical analyses were carried out in the R statistical environment (v4.5.1) [

17]. Before modelling, DNA concentration (Qubit, Nanodrop) and purity (260/280 and 260/230 ratios) variables were screened for extreme observations using descriptive statistics (<4% of the data). Data distributions were assessed with Shapiro–Wilk tests. Because both DNA concentration variables showed strong deviations from normality, we applied generalised linear mixed models (GLMMs) with a Gamma distribution and log link, using the

glmmTMB package [

18]. Species and tissue origin (antler or pedicle) were treated as fixed factors, while animal ID was included as a random effect. Purity variables (A260/280 and A260/230 ratios) showed approximately normal distributions; therefore, linear mixed models (LMMs,

lme4 package) were applied. Species and tissue origin were treated as fixed factors, while animal ID was included as a random effect only in the case A260/280 ratio. The inclusion of the random effect for the 260/230 ratio led to model singularity, as it had no effect; therefore, we removed it from further models. Model selection was based on likelihood ratio tests (LRTs), and for explanatory terms that improved model fit we report χ² statistics, p-values, and regression coefficients with standard errors. Pairwise post hoc contrasts were calculated from estimated marginal means with Holm’s correction for multiple comparisons (

emmeans package) [

19].

To examine whether Qubit and Nanodrop yielded comparable estimates, we calculated Spearman rank correlations. Correlations were tested across the full dataset as well as within subsets defined by tissue origin (antler vs. pedicle).

2.4. Assessment of the Subsequent Genetic Testability of DNA Isolates

The quality of DNA isolates was verified using microsatellite-based genetic profiling. For red deer genotyping with the

DeerPlex I and

DeerPlex II multiplexes [

7], a reduced reaction volume of 10 μL (instead of 25 μL) was used, while primers and PCR settings remained unchanged. For roe deer, the

STRoe deer plex was applied in a 15 μL reaction volume (instead of 20 μL), with all other settings following the original description [

20]. For fallow deer DNA samples, a newly developed 8-plex system (

Table S2) was applied based on the findings of Zorkóczy et al. [

21]. PCR conditions were optimised for fallow deer in a 15 μL reaction volume, containing 4 μL DreamTaq™ Green DNA Polymerase (ThermoFisher Scientific, Bioscience, Budapest, Hungary), 6 μL primer mix, 2 ng of DNA template, and PCR-grade H₂O to reach the final volume. Each polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed on 2400 Thermal Cyclers (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies Corp., Budapest, Hungary) using the following conditions for fallow deer: an initial step at 95℃ for 30 seconds, followed by 32 cycles of 30 s at 94℃, 60 s at 59℃ for annealing, and 40 s at 72℃, with a final extension of 2 min at 72℃. Negative (no-template) controls were included in each step to monitor for contamination.

PCR products from each multiplex system were first checked on a 2% agarose gel and then separated and analysed by capillary electrophoresis using an ABI Prism 3130XL Genetic Analyzer with the GeneScan-500 LIZ Size Standard (ThermoFisher Scientific, Bioscience, Budapest, Hungary). During fragment analysis using GeneMapper® ID-X software version 1.4, the minimum detection threshold was set at 150 relative fluorescence units (RFU).

3. Results

The sampling procedure described above yielded approximately 0.6 g of antler shavings, sufficient for multiple DNA preparation batches. Following extraction, agarose gel electrophoresis, Qubit, and Nanodrop quantification confirmed that the DNA isolates met the required quality and yield standards. The extracted DNA appeared highly intact, containing a substantial amount of endogenous DNA molecules (

Table 1,

Figure S1).

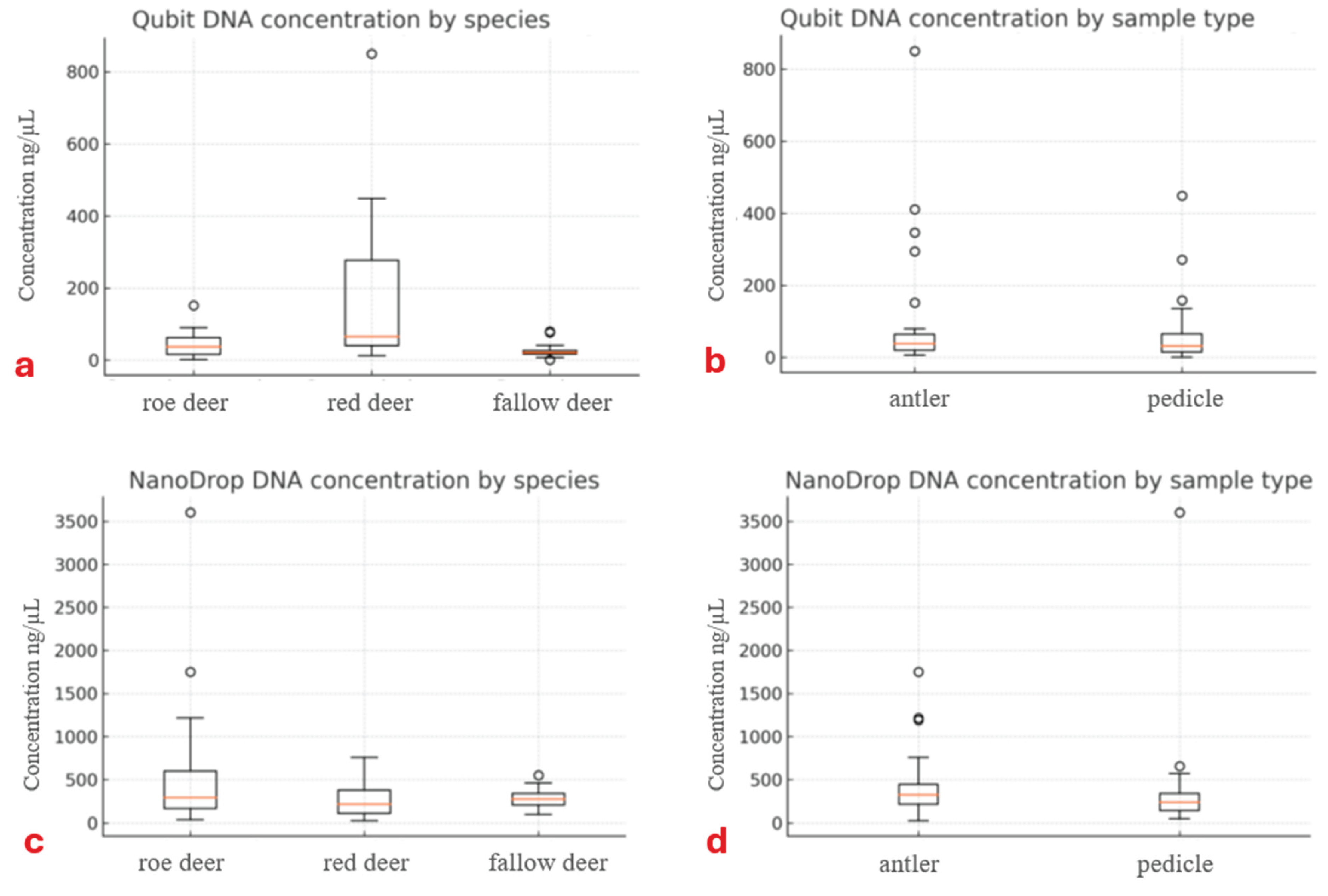

Based on the data presented in

Table 1, a notable difference was observed between the two concentration measurement methods. Using Qubit, the average DNA concentrations were 44 ng/µL, 174 ng/µL, and 26 ng/µL for roe deer, fallow deer, and red deer samples, respectively, whereas Nanodrop measurements yielded 602 ng/µL, 281 ng/µL, and 285 ng/µL, respectively.

DNA concentration measured with Qubit was significantly influenced by the species (GLMM, LRT: χ²₂ = 15.16, p < 0.001;

Figure 3a-b). Post hoc tests showed that red deer samples had significantly higher DNA concentrations compared to fallow deer (β ± SE = 1.48 ± 0.34, z = 4.42, p < 0.001) and roe deer (β ± SE = 0.99 ± 0.33, z = 2.98, p = 0.006) samples. No difference was found between roe deer and fallow deer samples (β ± SE = 0.49 ± 0.33, z = 1.49, p = 0.135). Neither the origin of the tissue, nor its interaction with the species had effect (GLMM, LRT; origin: χ²₁ = 2.19, p = 0.139, origin x species: χ²

2 = 2.69, p = 0.260).

Nor the species, nor its interaction with tissue origin affected the DNA concentration measured with Nanodrop (GLMM, LRT; species: χ²₂ = 2.04, p = 0.361, origin x species: χ²

4 = 6.40, p = 0.172). However, it was influenced by the origin of the tissue (χ²₁ = 4.88, p = 0.027;

Figure 3c-d), with higher values in antler compared to pedicle samples (β ± SE = 0.36 ± 0.16, z = 2.21, p = 0.027).

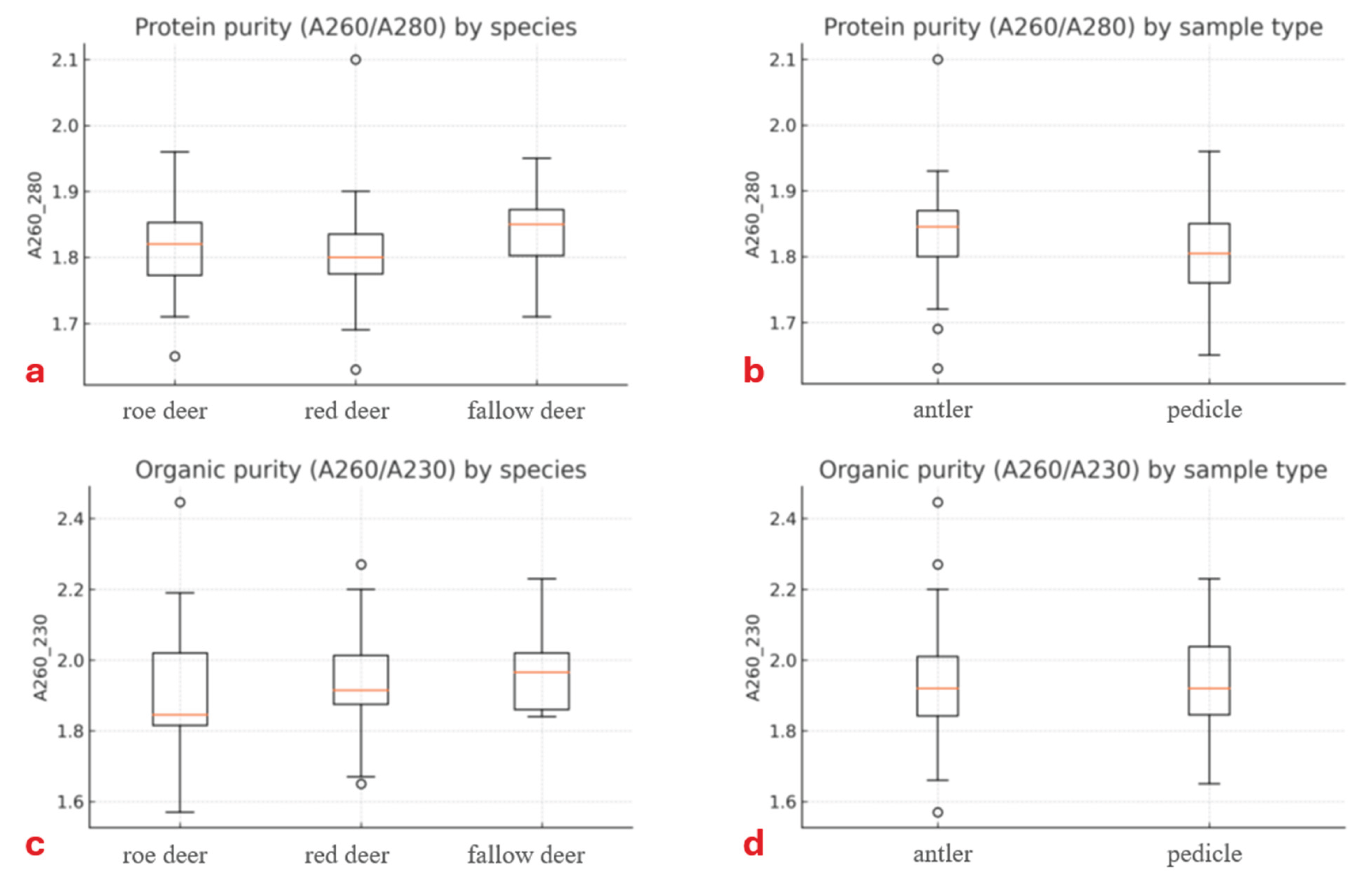

Purity values for both protein- and organic-related variables exhibited normal distributions despite relatively low absolute values (

Table 1). Protein-related purity (A260/280) ranged from 1.6 to 2.0, with an average of 1.8 across all three cervid species. Organic-related purity (A260/230) varied between 1.6 and 2.0, with average values of 1.9 in roe deer and red deer and 2.0 in fallow deer.

Neither the species (

Figure 4a,c), tissue origin (

Figure 4b,d), nor their interaction affected A260/280 and A260/230 purity ratios (260/280: null model had higher logLik values with all p < 0.065; A260/230 ratio: all p > 0.584). No correlation was observable between Qubit and Nanodrop DNA concentration values (ρ = –0.06, df = 56, p = 0.680).

Genotyping using species-specific multiplex STR systems was successful for all species and sample types using the previously described multiplex kits and PCR settings. Similarly, the multiplex fallow deer-specific system developed in this study, which allows for the simultaneous amplification of eight tetrameric microsatellites, also worked successfully. For each sample, a complete genetic profile could be generated from all extracted DNA isolates (

n = 60), with genotypes from samples of the same individual being identical and no identical profiles observed between samples from different individuals (

Tables S3–S5).

Case Study

Based on genotyping results obtained with the DNA extraction protocol described in this study and the red deer-specific multiplex STR systems, it was possible to establish that the deer skull and antler shared the same genetic profile (

Table S6). That is, the autosomal genetic profiles detected from the samples were identical at the analyzed loci, which, based on available Hungarian red deer population data [

7], supports the hypothesis that they originated from the same individual with extremely high probability.

4. Discussion

Reliable DNA extraction from calcified tissues such as bone, ivory, and antler is essential for wildlife forensics, conservation genetics, food safety, evolutionary biology, and ancient DNA studies. While antlers of various deer species have been studied previously, protocols for roe deer and fallow deer antlers and trophies remain underexplored.

Traditional methods often require expensive milling equipment, liquid nitrogen, or lengthy demineralization steps, and may yield degraded DNA. Over the past decades, various extraction strategies have been developed. Phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction is a well-established, high-yield method applicable across tissues but involves hazardous reagents. Silica column-based kits provide user-friendly workflows and high DNA purity but can be costly, while magnetic bead-based methods enable automation yet demand specialized equipment. Chelex® extraction is economical but often provides insufficient purity for sensitive downstream analyses. Thus, the choice of method must balance yield, purity, cost, and laboratory capacity.

In this study, we optimized a simplified, low-cost protocol for deer antlers using mechanical homogenization (TissueLyser), organic extraction, and Microcon

® centrifugal filtration. This approach avoids the need for bone mills and liquid nitrogen, yet consistently produces high DNA yields, particularly from the antler shaft, which appears better preserved and less inhibitor-rich than the pedicle [

4]. Avoiding marrow-rich material likely enhanced DNA quality, as lipids are known to interfere with extraction and filtration. The protocol was reproducible, PCR-compatible, and suitable for laboratories with limited resources. Compared with earlier protocols that required large sample amounts [

3,

16] or specialized grinding tools [

2,

4,

11,

12], our method offers a minimally destructive alternative that remains compatible with downstream applications.

The DNA recovered with this protocol met integrity and yield requirements, with Qubit quantification confirming reliable concentration estimates. In contrast, Nanodrop values were considerably higher, likely due to protein and organic contaminants, reinforcing the use of Qubit for accurate quantification. Although purity ratios were not always ideal, PCR amplification and multiplex STR genotyping were successful across all cervid species and sample types, consistent with the view that modest deviations in purity do not necessarily compromise molecular workflows. Identical genotypes obtained across replicate samples confirmed the reproducibility of the method, and the case study further demonstrated its forensic value by matching a skull and antler from the same individual.

Previous studies on DNA extraction from calcified samples have primarily relied on two main strategies: (1) EDTA-based demineralization followed by classical organic extraction and ethanol precipitation, and (2) commercial silica column kits. The former is particularly effective for degraded or museum-grade samples and often involves extended digestion (24–36 hours), enabling recovery of both mitochondrial and nuclear markers [

3,

4,

5,

11,

13,

22]. This approach efficiently removes inhibitors such as collagen and, in environmentally exposed samples, humic substances, which are common in bone and antler tissues and can interfere with downstream molecular applications. Silica column kits, while effective for fresh or less degraded material, may underperform with calcified or inhibitor-rich tissues unless modified with additives such as EDTA or Chelex [

2,

7,

8,

10,

16]. Nonetheless, inhibitor carryover remains a concern in some cases. Notably, several previous studies did not report the exact amount of sample processed or failed to indicate the extraction method in sufficient detail. Moreover, while DNA yields are often given, information on DNA purity is frequently missing. In contrast, our protocol was thoroughly evaluated: although purity values were not ideal in all cases, the PCR results confirmed that this did not compromise the success of downstream molecular analyses.

Overall, phenol-based methods tend to maximize yield, whereas silica column techniques generally provide higher purity. Where both parameters are equally critical, phenol extraction followed by column purification may be optimal. Our results highlight that efficient DNA recovery from antler is feasible without costly equipment, and the developed protocol can broaden access to molecular analyses in forensic and conservation contexts.

5. Conclusions

We developed a short, simple, and cost-effective DNA extraction protocol applicable to the pedicle part of prepared skulls and antlers from different deer species, including roe deer and fallow deer, which had not been previously investigated. The method consistently yielded DNA of sufficient quality and quantity, as confirmed by various concentration and purity measurement methods, as well as on case samples, and subsequent genetic analyses. By avoiding the need for specialized equipment, this approach expands access to reliable molecular analyses in laboratories with modest infrastructure. These features make the protocol a valuable tool for wildlife forensics, conservation genetics, and broader research contexts requiring DNA recovery from antlers and other calcified tissues.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1: Genetic studies performed on antlers of deer species, indicating the purpose of the study, the extraction method of genetic material, the results regarding the quantity and quality of the extracted DNA, and the subsequent molecular methods used; Table S2: Details of the 8-plex fallow deer multiplex PCR: primer sequences for 8 autosomal STRs, size range, and primer concentrations; Figure S1: Quality assessment for the integrity of DNA isolates (

n = 16) by gel electrophoresis using 1% agarose gel; Table S3: Genetic profiles of the roe deer antlers and trophies investigated, based on the size of the detected fragments located in the allele fragment size-interval of the roe deer-specific STR markers; Table S4: Analytical results of fragments detected in red deer antlers and trophies using two tetrameric 5-plex STR systems, within the allele size range of red deer-specific STR markers; Table S5: Analytical results of fragments detected in fallow deer antlers and trophies using a tetrameric 8-plex STR system, within the allele size range of fallow deer-specific STR markers

; Table S6: Analytical results of fragments detected in red deer antlers and trophies in the case study using two tetrameric 5-plex STR systems, within the allele size range of red deer-specific STR markers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.Z. and E.L.; methodology, E.L. and P.Z.; software, O.K.Z.; formal analysis, E.L.; investigation, E.L., P.Z., and O.K.Z.; resources, L.M., N.B., and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.L.; writing—review and editing, P.Z.; funding acquisition, Zs.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Project no. 2024-2.1.2-EKÖP-2024-00018 was funded by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the 2024-2.1.2-EKÖP funding scheme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

None of the tests described in the manuscript titled ‘A simplified and efficient protocol for DNA isolation from deer antlers and prepared trophy skulls’ required the approval of the Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board. There were no experimental animals involved in the study. The samples required for the tests were obtained from animals that were shot in compliance with the current national and international laws in force. Hunting licenses are personal documents owned by professional hunters and cannot be disclosed due to the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR). The authors do not have access to any such documents.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Hungarian Institute for Forensic Sciences for providing institutional support for this study. We also thank the Hungarian hunting associations and private hunters for providing trophy samples, as well as the staff of the University of Veterinary Medicine Budapest for their technical assistance during laboratory work. Statistical advice provided by Dr. Boglárka Morvai is also acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no interests that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EDTA |

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid |

| GLMM |

Generalized Linear Mixed Model |

| LMM |

Linear Mixed Model |

| LRT |

Likelihood Ratio Test |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RFU |

Relative Fluorescence Unit |

| STR |

Short Tandem Repeat |

| TE buffer |

Tris-EDTA buffer |

References

- Lincoln, G.A. Biology of Antlers. J. Zool. 1992, 226, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejero, J.-M.; Cheronet, O.; Gelabert, P.; Zagorc, B.; Álvarez-Fernández, E.; Arias, P.; Averbouh, A.; Bar-Oz, G.; Barzilai, O.; Belfer-Cohen, A.; et al. Cervidae Antlers Exploited to Manufacture Prehistoric Tools and Hunting Implements as a Reliable Source of Ancient DNA. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuehn, R.; Ludt, C.J.; Schroeder, W.; Rottmann, O. Molecular Phylogeny of Megaloceros Giganteus — the Giant Deer or Just a Giant Red Deer? Zoolog. Sci. 2005, 22, 1031–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, G.S.; Griebeler, E.M. An Improved High Yield Method to Obtain Microsatellite Genotypes from Red Deer Antlers up to 200 Years Old. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2013, 13, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, A.; Denome, R.M. Microsatellite Locus Amplification Using Deer Antler DNA. BioTechniques 1999, 26, 1086–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, R.G.; Beier, P. Weathered Antlers as a Source of DNA. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2012, 36, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabolcsi, Z.; Egyed, B.; Zenke, P.; Padar, Z.; Borsy, A.; Steger, V.; Pasztor, E.; Csanyi, S.; Buzas, Z.; Orosz, L. Constructing STR Multiplexes for Individual Identification of Hungarian Red Deer. J. Forensic Sci. 2014, 59, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, H.; Zhang, F.; Han, R.; Li, H. DNA Methylation Pattern and mRNA Expression of OPN Promoter in Sika Deer Antler Tip Tissues. Gene 2023, 868, 147382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, P.; Wang, T.; Liu, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, P.; Xing, X. Full-Length Transcriptome and microRNA Sequencing Reveal the Specific Gene-Regulation Network of Velvet Antler in Sika Deer with Extremely Different Velvet Antler Weight. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2019, 294, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Bai, M.; Yang, H.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis Reveals Layer-Specific Methylation Patterns in Deer Antler Tissue. Gene 2023, 884, 147744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, H.; Yoneyama, K.; Hayashizaki, Y.; Hara, M.; Takada, A.; Saito, K. Establishment of Widely Applicable DNA Extraction Methods to Identify the Origins of Crude Drugs Derived from Animals Using Molecular Techniques. J. Nat. Med. 2019, 73, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ren, Q.; Feng, J.; Lee, S.Y.; Liu, Y. DNA Barcoding for the Identification and Authentication of Medicinal Deer (Cervus Sp.) Products in China. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0297164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Li, C. Identification and Characterization of Alternative Splicing Variants and Positive Selection Genes Related to Distinct Growth Rates of Antlers Using Comparative Transcriptome Sequencing. Animals 2022, 12, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, X.; Zhai, J.; Xia, Y.; Li, H. Analysis of Genetic Information from the Antlers of Rangifer Tarandus (Reindeer) at the Rapid Growth Stage. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0230168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Colón, E.; Hernández, M.; Candelario, M.; Meléndez, M.; Dawson Cruz, T. Evaluation of a Freezer Mill for Bone Pulverization Prior to DNA Extraction: An Improved Workflow for STR Analysis. J. Forensic Sci. 2018, 63, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venegas, C.; Varas, V.; Vásquez, J.P.; Marín, J.C. Non-Invasive Genetic Sampling of Deer: A Method for DNA Extraction and Genetic Analysis from Antlers. Gayana Concepc. 2020, 84, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2025.

- Brooks, M., E.; Kristensen, K.; Benthem, K., J.; Magnusson, A.; Berg, C., W.; Nielsen, A.; Skaug, H., J.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B., M. glmmTMB Balances Speed and Flexibility Among Packages for Zero-Inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Modeling. R J. 2017, 9, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R.V. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means 2017, 1.11.2.

- Morf, N.V.; Kopps, A.M.; Nater, A.; Lendvay, B.; Vasiljevic, N.; Webster, L.M.I.; Fautley, R.G.; Ogden, R.; Kratzer, A. STRoe Deer: A Validated Forensic STR Profiling System for the European Roe Deer (Capreolus Capreolus). Forensic Sci. Int. Anim. Environ. 2021, 1, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorkóczy, O.K.; Turi, O.; Wagenhoffer, Z.; Ózsvári, L.; Lehotzky, P.; Pádár, Z.; Zenke, P. A Selection of 14 Tetrameric Microsatellite Markers for Genetic Investigations in Fallow Deer (Dama Dama). Animals 2023, 13, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, Amit Kumar; Khan, Shahbaz; Joshi, P.C.; Bahuguna, Archana; Dev, Kapil Wildlife Forensic Techniques: DNA Extraction from Hard Biological Matter of Chital (Axis Axis), Molecular Analysis, Use of SEM and EDX in Species Identification. IOSR J. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2016, 2, 104–110.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).