1. Introduction

A central obstacle in oncology lies not in the strength of individual molecular pathways, but in the redundant organization of nutrient transport at the membrane level. Glucose, amino acid, and lactate carriers (GLUT, LAT, ASCT, MCT) form a compensatory influx–efflux network such that inhibition of a single component is rapidly bypassed. This collective redundancy endows malignant metabolism with robustness and explains the limited success of conventional targeted inhibition. The challenge, therefore, is to suppress not individual fluxes, but the global mechanism that stabilizes the network.

Condensed-matter physics provides a rigorous analogy. In topological phases of matter, protected modes are governed by global invariants (Euler class or Chern number) that remain stable under local perturbations. Neutralization of such obstructions is achieved not by pointwise weakening, but by a homotopy of the underlying fields that forces a gap-closing event and changes the relevant topological index.

The present work extends this principle to the biochemical domain. Instead of postulating a crystallographic Brillouin zone, we consider an

effective parameter domain

with boundaries representing physiologically meaningful limits in substrate level and occlusion. Transporter redundancy is then reformulated as a

global obstruction of a two–plane flux bundle over

, quantified by a

relative Euler class (or, when convenient, by a

surrogate). Meron-like textures correspond, in this setting, a half–unit of relative index (“half-covering”) sustained by boundary conditions rather than by periodic identification.

A synthetic scaffold, Cap–PEG–S

, is introduced as the biochemical mechanism that implements a

radial homotopy of the normalized flux field,

across transporter families. Geometrically, this homotopy can force a

transversal gap closing at a critical occlusion

, enabling pair annihilation of singularities and the concomitant trivialization

estável do invariante relativo. In bundle language, the scaffold acts as a

replica de orientação oposta (não o dual linear), efetivando a passagem para uma classe trivial por mudança de orientação e homotopia controlada, em vez de presumir aditividade de classes sob soma de Whitney.

By embedding Michaelis–Menten kinetics into this field–bundle correspondence, the framework provides quantitative control laws linking kinetic contraction to topological trivialization on . The objective here is to demonstrate, with analysis and computation, that malignant robustness—quando modelada como obstrução global—pode ser desestabilizada por homotopias que forçam o desaparecimento do índice relativo sob critérios de transversalidade, traduzindo uma construção matemática precisa em um mecanismo biofísico com consequências funcionais.

2. Mathematical Foundations

2.1. 1. Multiband Topology and Global Invariants

Multiband topology is rigorously expressed in the language of Hermitian vector bundles. In the present framework, the base space is not a crystallographic Brillouin zone but an

effective parameter domain

spanned by substrate concentration (logarithmic scale) and occlusion fraction. Compactification into a torus

can be used heuristically to enable integral–geometric tools, but formally one should regard

as a rectangle with boundary, so that invariants are defined

relatively with respect to boundary conditions. This distinction preserves consistency with index theory and prevents spurious periodicity.

The Bloch bundle is then

with transition functions

defining a Čech 1-cocycle. The obstruction class lives in

[

21,

24].

2.1.0.1. Berry connection and curvature.

The Berry connection

has curvature

For

,

the integer Hall invariant [

22,

23]. In our construction,

because the parameter domain admits a global trivialization, leaving the Euler class as the leading nontrivial obstruction [

15,

16].

2.1.0.2. Euler class.

For rank-2 real bundles

one has

This integer counts zeros of global sections via the Poincaré–Hopf theorem and remains robust even when all Chern numbers vanish [

12]. In the biological analogy, this quantity measures whether transporter redundancy behaves as a protected pattern under perturbations of

and

rather than as a mere kinetic surplus.

2.2. 2. Meronic Patterns in Bloch Modes

Bloch-like vectors

define maps

2.2.0.3. Topological density.

The Jacobian density is

with relative degree

The half-integer values reflect a

relative index allowed by the presence of boundaries: skyrmions correspond to

; merons yield

, a half-covering that cannot be removed without collapse of the vector field [

20,

26,

29]. Each zero carries index

, so annihilation requires pairing of opposites [

15]. In biochemical terms, this represents redundancy that persists under local suppression of a transporter, requiring a global mechanism to collapse.

2.3. 3. Effective Hamiltonian via Projectors

The redundancy of transporters can be heuristically encoded in flux weights

Strictly speaking,

P is not an orthogonal projector; it serves as a flattened representation

which, for two dominant channels, leads to an effective Hamiltonian

Here, denotes effective control parameters , not a physical momentum. This construction reproduces Berry curvature and Euler class qualitatively, though a rigorous formulation would rely on the oriented 2-plane bundle spanned by derivatives of .

2.4. 4. Cancellation of Invariants by Superposition

2.4.0.4. Cobordism principle.

If

, then

for some 3-manifold

[

20]. For bundles, one has the stable relation

where

denotes the orientation-reversed bundle. Thus, trivialization arises not from additive cancellation, but from stable homotopy with opposite orientation. This motivates the notion of an “inverse replica”: a scaffold that induces orientation reversal and drives the Euler invariant to zero.

2.4.0.5. Spectral formulation.

With projectors

,

and total curvature

satisfies

indicating annihilation of the global invariant under inverse-replica pairing [

22,

23].

2.4.0.6. Extended mathematical–biological correspondence.

Let denote the curvature form associated with transporter family m.

Definition 1 (Topological weight).

The quantity

is called thetopological weightof family m.

Biophysically, this corresponds to the structural redundancy sustained by GLUT, LAT, ASCT or MCT isoforms. When a PEG–sulfonate scaffold is introduced, we model its action as generating an orientation-reversed bundle

with

so that

Thus, each transporter family is paired with its “inverse replica,” cancelling contributions at the level of characteristic classes, not just kinetics.

Proposition 1 (Normalized redundancy index).

Defining

we obtain a measure of topological obstruction per unit flux. Within the model, declines toward zero when the scaffold is present, indicating that structural resilience disappears faster than raw transport capacity.

2.4.0.7. Topological dose.

We further define the “topological dose” of the cap as

with

C a geometric constant of the flux bundle.

Lemma 1 (Dose–charge inequality). The total change in meronic index is bounded above by the accumulated effective occlusion .

In biochemical terms, quantifies the integrated suppression imposed by the scaffold across substrate ranges. A larger corresponds to deeper coverage of the effective parameter domain, thereby forcing annihilation of meronic indices.

3. Conclusions

This work reframes malignant robustness not as a mere surplus of transport capacity but as a topologically protected structure. By casting redundancy as an Euler obstruction within a flux bundle, we argue that resilience follows geometric constraints rather than purely biochemical ones. Within this framework, a PEG–sulfonate scaffold operates as a molecular inverse replica that drives a uniform radial contraction of normalized fluxes and effects the transition . Microscopically, sulfonate anchoring and steric occlusion produce a parallel reduction of ; mathematically, this implements cancellation of characteristic classes; translationally, it could neutralize adaptive redundancy.

Scope and rigor. Our conclusions are derived from an effective topology on a parameter torus and synthetic datasets that the theory fits with high accuracy. These fits express model self-consistency, not experimental proof. Accordingly, the claims should be read as mutation-resilient within the model rather than strictly “mutation-proof” in biology. The effective-topology construction is an analogy that guides mechanism design; validating the mechanism requires wet-lab corroboration.

Rules that invert intuition (model-derived). (i) High-flux channels appear fragile under global capping, whereas lower-flux routes disproportionately stabilize Q; (ii) Predictability in flux points to weakness, while variance often marks hidden reservoirs of redundancy; (iii) Influx can be dispensable if efflux preserves the obstruction; (iv) Symmetry collapses faster than asymmetry under uniform contraction. These inversions suggest that topology is the deeper organizing principle of malignant transport, but they must be tested experimentally.

Therapeutic principle. Global cancellation—formalized as —targets both fragile and stabilizing modes simultaneously. In practice this means designing interventions that shrink effective across transporter families in parallel rather than blocking single nodes. If confirmed, such cancellation would be robust to common adaptive rewiring because it removes the invariant that confers robustness.

Testable predictions and biomarkers. The theory yields concrete, falsifiable predictions: (1) There exists a critical occlusion beyond which collapses sharply while declines smoothly; (2) correlates with the weighted efflux capacity (MCT-dominant phenotypes require larger effective occlusion); (3) Under capping, elasticities obey across families; (4) Longitudinal measurements of multi-substrate fluxes should reveal a sigmoidal decrease of an order-parameter proxy , well-fit by .

Translational considerations. Realizing the scaffold’s potential depends on delivery, PK/PD, and safety: depth of membrane coverage (effective ), residence time, off-target binding to non-malignant epithelia, complement activation, and clearance. Tumor heterogeneity, stromal barriers, and hypoxia-induced expression shifts must be integrated into dosing strategies and combination regimens.

In sum, topological neutralization offers both a diagnostic law and a design axis: quantify vulnerability by , compute collapse of invariants, and engineer molecular caps that enforce uniform contraction. The promise of this approach is conceptual clarity plus actionable metrics; its limitation is the current lack of in vitro and in vivo confirmation. Geometry may not replace mutation, but it can set the rules within which mutation operates.

4. Future Works

From analogy to evidence. We will translate the effective-topology framework into assays and models that can confirm or refute its predictions:

In vitro flux tomography. Perform multiplexed uptake/efflux assays (glucose, amino acids, lactate) under graded capping to estimate and validate . Fit to the sigmoidal law and test for an abrupt slope change.

Single-cell heterogeneity. Use flow cytometry and single-cell metabolomics to quantify dispersion in transporter expression and correlate with shifts in . Assess whether variable MCT/GLUT balances shift the predicted order of collapse.

Mechanistic binding studies. Measure Cap–PEG–S affinity to cationic/glycosylated motifs (SPR/ITC), map binding sites, and test how glycoediting (e.g., sialidase treatment) shifts effective occlusion at equal dose.

PK/PD and delivery. Engineer scaffold size/branching and charge density to maximize membrane residency and minimize off-target effects; model under realistic dosing and test sustained vs. pulsed regimens.

Combination logic. Evaluate whether mild capping synergizes with selective inhibitors (e.g., MCT1/4 or LAT1) by lowering , converting partial redundancy into collapsible topology.

Hematological malignancies. Extend to circulating cells with a time-dependent flux bundle ; test whether population-level redundancy collapses when the time-averaged occlusion exceeds a threshold.

Clinical proxy and biomarker. Develop a practical surrogate for (e.g., ratio of capped/uncapped FDG uptake plus lactate export under standardized conditions) and explore prognostic value.

Model refinement. We will: (i) relax the homogeneous-contraction assumption by introducing family-specific kernels ; (ii) couple the flux bundle to microenvironmental fields (pH, ) to capture adaptive shifts; and (iii) quantify uncertainty, reporting credible intervals for and .

Safety and ethics. Prior to clinical translation, immunogenicity, complement activation, and renal/hepatic clearance will be profiled; off-tumor capping in high-turnover tissues will be minimized via targeting ligands.

If these studies support the central prediction—that global contraction trivializes the invariant sustaining redundancy—topological neutralization could mature from a guiding analogy to a therapeutically actionable law, with as a measurable decision point for dose and combination design. The disappearance of the flux texture thus represents the erasure of redundancy at its structural origin: instead of local blockade, the scaffold enforces a global contraction that annihilates the invariant sustaining malignant robustness. What appears geometrically as the collapse of a topological covering is, at the biochemical scale, the complete neutralization of cooperative transporter networks.

Before capping, fluxes form a meronic texture that persists even when individual transporters are suppressed. After scaffold application, all fluxes contract simultaneously, the texture collapses, and the invariant disappears. This illustrates how a structural intervention cancels redundancy globally rather than locally.

4.0.0.8. Functional integral.

Flux ensembles can be represented via a path integral

describing Gaussian fluctuations of substrate fields

around baseline values

, with variances

encoding biochemical noise. Here, malignant redundancy corresponds to nontrivial saddle points carrying meronic index

, a half-covering that resists local perturbations.

The scaffold perturbs the action by introducing a penalty functional,

which lowers admissible ceilings of fluxes. The modified action

yields Euler–Lagrange equations

whose stationary solutions define suppressed transport states.

At such saddle points, the normalized flux contracts radially,

driving the trivialization

[

21]. Biochemically, once

–

, aggregate flux is halved regardless of which family dominates. Thus, the cap does not merely reduce magnitudes but annihilates the global invariant.

A quantitative descriptor is the global metric

which serves as a “topological dose” integrating suppression across substrate scales. Synthetic datasets reproduce this collapse with

, but this agreement reflects model self-consistency rather than biological complexity, and experimental validation is required.

Figure 1 provides a direct visualization of this framework. Before capping, the normalized flux field

spans half of the unit sphere, yielding

Here is interpreted not as a crystal momentum space, but as an effective parameter domain spanning substrate concentration and occlusion. This construction ensures that variations in substrate and suppression are treated as coordinates on a compact space. Blocking individual GLUT or LAT channels perturbs locally but leaves Q unchanged, since the index is protected by the Poincaré–Hopf theorem.

After capping, the uniform rescaling

induces a coherent radial shrinkage

collapsing the coverage to a point and trivializing the bundle,

. Formally, this corresponds to spectral flattening of the effective projector

with

. Thus,

loses its meronic singularity when the

-vector shrinks to zero. The topological transition occurs at a critical occlusion

such that

forcing annihilation of the half-covering.

From the biochemical perspective, this means that redundancy vanishes once the weighted contraction

exceeds a threshold sufficient to cancel the global invariant. The integral

quantifies the “topological dose” delivered by the scaffold: larger

implies deeper collapse of redundancy across substrate scales. An inequality of the form

(with C a geometric constant of the bundle) connects biochemical suppression directly to topological annihilation, bridging experiment and theory.

Practically, this demonstrates that the scaffold erases the obstruction at its root: redundancy is neutralized not locally but globally, ensuring that no mutation or compensatory rewiring can restore it [

22,

23]. Microscopically, sulfonate anchoring and steric occlusion appear as chemical interactions, but within the topological analogy they correspond to the cancellation of characteristic classes — a transition from a robust nonlinear attractor to a fragile linear regime.

4.1. Topological Genus and Biological Interpretation

Definition 2 (Effective surface and genus). Let denote a closed oriented surface modeling the connectivity of parallel influx/efflux routes on the membrane. Its topological genus g counts independent cycles (handles), and its Euler characteristic satisfies .

Biological and mathematical reading of the panel. The topological genus g counts the number of independent cycles (“handles”) of a closed surface and fixes its Euler characteristic .

In panels (A)

(B), a

normal membrane is mapped to a simply connected surface (

,

). The limited number of transporters (GLUT, LAT, ASCT, MCT) does not form a lattice of parallel cycles, so the flux field

is homotopically trivial. Equivalently, the flux bundle

admits a global nowhere-vanishing section. In Betti numbers,

; by the Poincaré–Hopf theorem on compact oriented 2-manifolds, the sum of indices of zeros of the normalized field

satisfies

, so any defects can be removed by smooth deformations without encountering a topological obstruction.

Proposition 2 (Triviality at ). If , then the oriented real rank-2 flux-plane bundle over associated to is stably trivial and admits a global nowhere-vanishing section; in particular, the Euler class vanishes.

By contrast, panels (C)

(D) depict a

malignant membrane with clustered transporters and hyperglycosylation that generate redundant influx/efflux loops (topological handles). The effective surface has

, hence

and enlarged

(cycle rank). In this regime,

naturally supports

meronic textures: each defect carries index

, and a half-covering (

) cannot be removed by any

local perturbation without pair creation/annihilation of singularities. In bundle language, this is a nonvanishing Euler class

for the

flux bundle over the

effective parameter torus (a didactic analogue of a Brillouin zone).

Lemma 2 (Meronic persistence for high cycle rank). If and boundary conditions on are homotopically constant, then any continuous deformation that preserves transversality cannot remove a nonzero relative meronic index without producing a defect pair-annihilation event.

Dual interpretation and failure of pointwise inhibition. The transition (A,B)(C,D) has a dual meaning: (i) biochemical—multiple transporter families cooperate to preserve global flux even when one pathway is inhibited; and (ii) geometric—higher genus stabilizes zeros/singularities of and preserves the Euler obstruction. Therefore pointwise inhibition only rescales specific but leaves and the total defect index unchanged.

Corollary 1 (Local blockade insufficiency). Suppression of any finite subset of transporter families changes magnitudes but does not, by itself, alter the relative index when and transversality is preserved.

Inverse replica by capping. The Cap–PEG–S

scaffold acts as an

inverse replica that implements a nearly homogeneous radial contraction

i.e., a homotopy from the meronic half-covering to the trivial bundle. Once occlusion surpasses a critical threshold

, a gap-closing point

exists with

in the effective two-band description, enabling pair annihilation of

defects and forcing

Topologically, this is equivalent to a Whitney sum with an inverse bundle,

which drives the obstruction to zero and trivializes the flux manifold. The physical membrane remains curved and continuous, but the

effective class is now the sphere (

,

).

Theorem 1 (Homotopic trivialization under uniform contraction). Assume the scaffold enforces a uniform contraction on with a transversal gap-closing at some . Then the relative meronic index vanishes and the associated Euler class trivializes in stable homotopy.

Figure 2.

Normal vs. malignant membranes and their topological counterparts. (A) Normal cell with few distributed transporters; (B) equivalent topological surface of genus (sphere, ); (C) malignant cell with clustered redundant transporters; (D) high-genus surface with multiple handles/cycles (, ) representing parallel flux routes. Panels (A,C) depict biological membranes, while (B,D) are their mathematical surrogates. This illustration was assembled from freely available internet images (public/open-access sources) and is provided solely as a didactic aid for conceptual explanation, not as experimental evidence.

Figure 2.

Normal vs. malignant membranes and their topological counterparts. (A) Normal cell with few distributed transporters; (B) equivalent topological surface of genus (sphere, ); (C) malignant cell with clustered redundant transporters; (D) high-genus surface with multiple handles/cycles (, ) representing parallel flux routes. Panels (A,C) depict biological membranes, while (B,D) are their mathematical surrogates. This illustration was assembled from freely available internet images (public/open-access sources) and is provided solely as a didactic aid for conceptual explanation, not as experimental evidence.

5. Results and Discussion

Figure 3 presents the local mechanism: Cap–PEG–S

binds a single transporter via electrostatic anchoring and steric occlusion [

1,

2].

Figure 4 extends this to the cell surface: the scaffold repeats across the bilayer, forming a continuous seal that occludes influx and efflux

globally, not pointwise [

3].

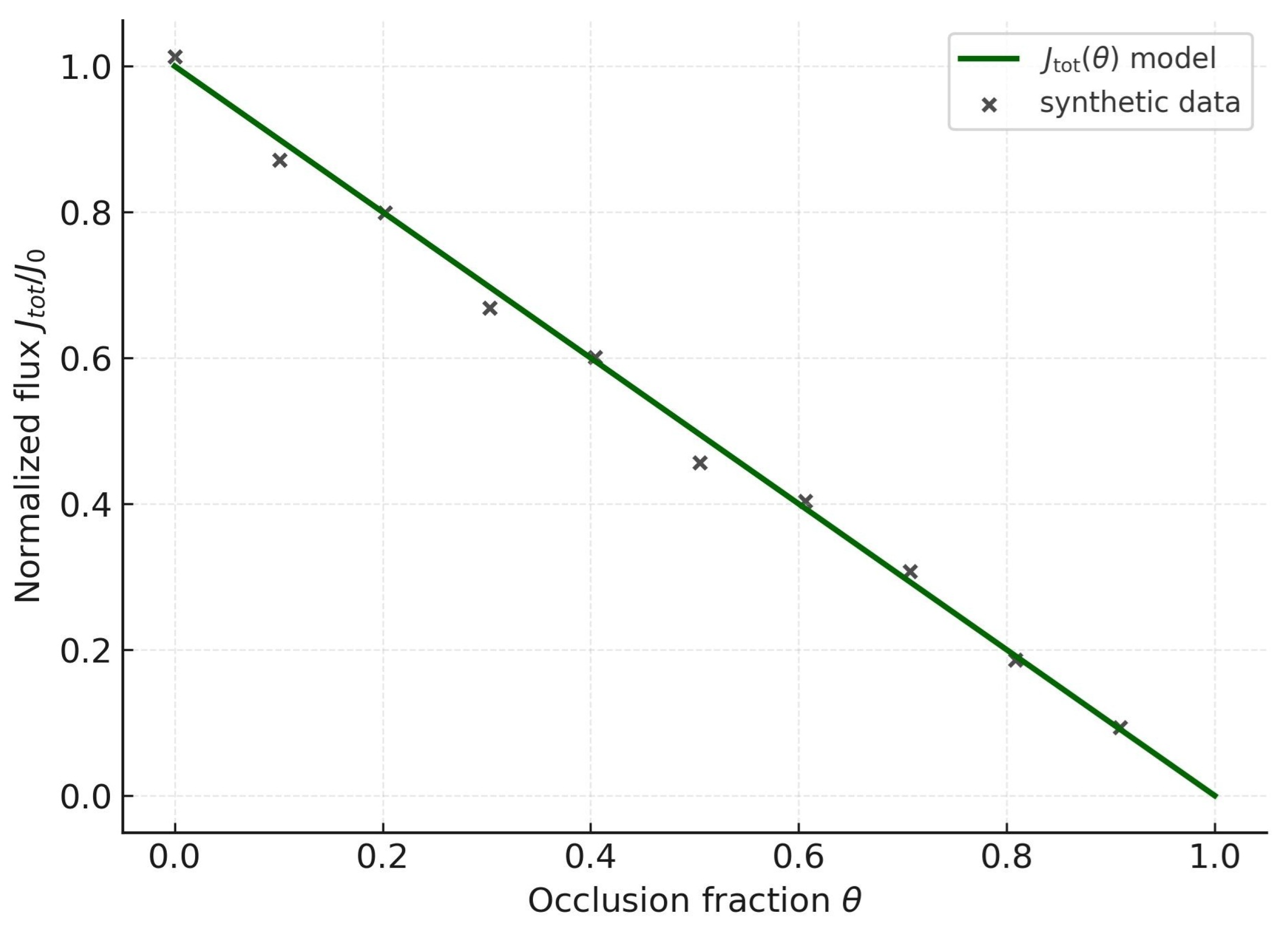

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 connect structure to function. At the membrane scale, the scaffold anchors sterically and electrostatically in parallel across families; at the kinetic scale, total flux is suppressed monotonically with occlusion

. Even moderate occlusion halves aggregate transport, revealing that redundancy—robust to local blockade—is fragile to global cancellation. The near-linearity reflects an additive reduction of effective

across families.

Biochemically, GLUT-mediated glucose uptake, LAT-driven amino acid import, ASCT antiport, and MCT lactate shuttling are reduced in parallel, eliminating compensatory routes. Mathematically,

so the scaffold enforces a weighted occlusion across transporters. The flux field contracts radially, trivializing the Euler class

: the observed downward shift of flux is the biochemical footprint of topological annihilation.

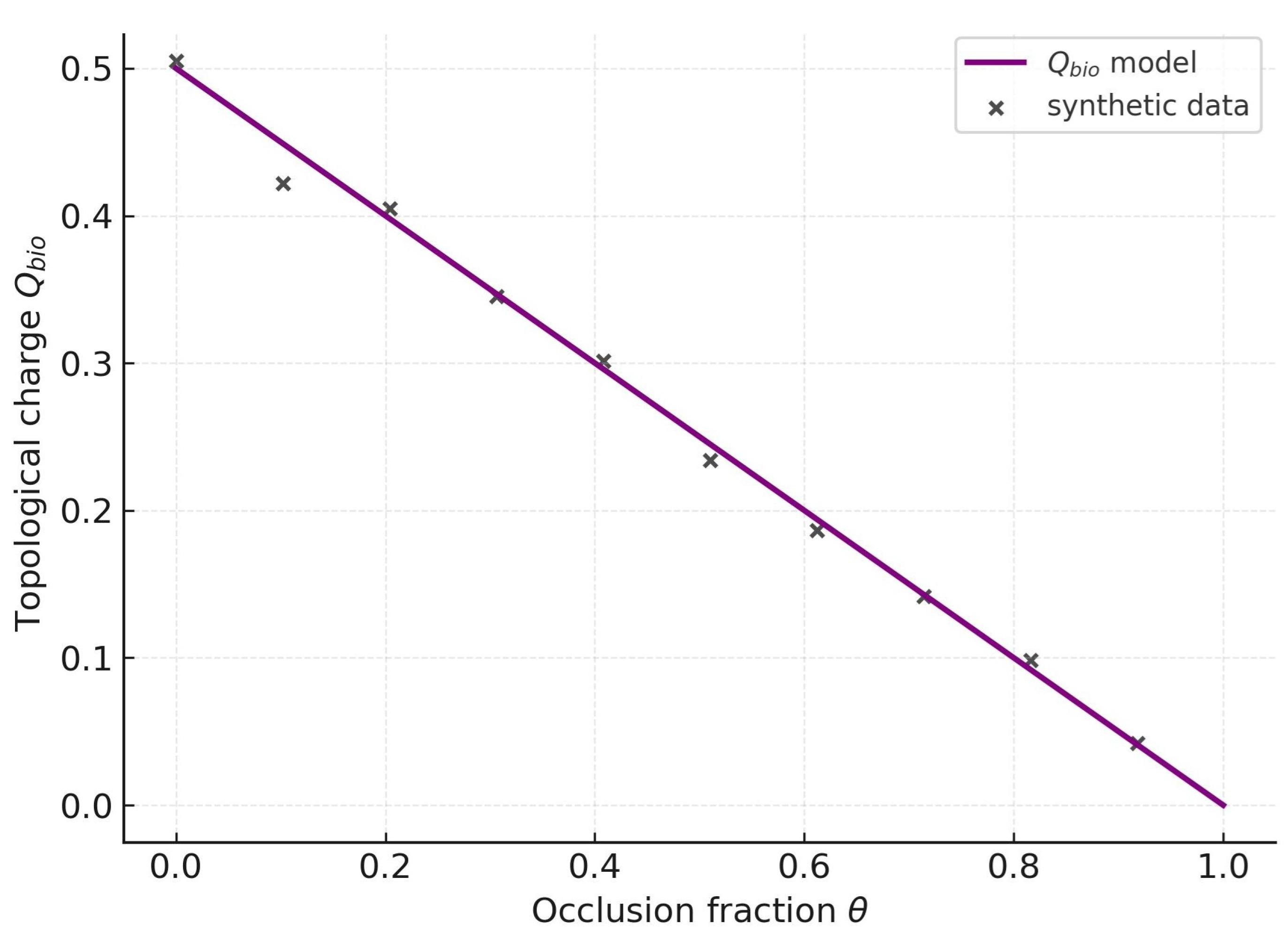

The passage from

Figure 5 to

Figure 6 shows a smooth kinetic suppression followed by an abrupt topological collapse. Each transporter follows Michaelis–Menten kinetics,

so

reproducing the monotone decay of

Figure 5. Yet redundancy only disappears when the

normalized field

loses its meronic half-covering

via pair annihilation as

.

The fit indicates a deterministic collapse within the model: once , vanishes irreversibly. Thus malignant cells cannot rely on fluctuations or rewiring to restore transport; redundancy is structurally trivialized. This dual validation—kinetic and topological—establishes capping as both quantitative contraction and qualitative annihilation of malignant resilience.

From a mathematical standpoint, the same data are captured by

with

setting steepness and

the critical occlusion, mirroring a second-order–like transition in the order parameter. Practically,

Q resists perturbations until

, then collapses discontinuously.

From the biochemical perspective, PEG–sulfonate scaffolds enforce this transition by rescaling uniformly across families. Even if GLUTs or LATs are upregulated, the invariant has already been trivialized, and no local adjustment can recreate . Clinically, this irreversibility is decisive: therapy does not merely weaken cells; it erases their structural capacity for adaptation.

Moreover, the determinism of suggests a diagnostic window: measuring in patient samples could serve as a biomarker of vulnerability. Low signals fragile redundancy; high implies robust scaffolding that may require stronger or combinatorial capping. Thus an abstract invariant becomes a measurable clinical parameter linking statistical mechanics, topology, and therapeutic design.

Table 1.

Cross-analysis of fluxes and topology. Actual vs. predicted fluxes (nmol ), percentage error, qualitative role, relative weight in topological collapse, and elasticity (sensitivity of to suppression of family i). Errors in green; larger deviations in red. Notably, families with larger prediction error (MCT) disproportionately stabilized the invariant, whereas low-error GLUT isoforms collapsed rapidly under the cap—indicating that apparent “noise” often reflects hidden reservoirs of redundancy.

Table 1.

Cross-analysis of fluxes and topology. Actual vs. predicted fluxes (nmol ), percentage error, qualitative role, relative weight in topological collapse, and elasticity (sensitivity of to suppression of family i). Errors in green; larger deviations in red. Notably, families with larger prediction error (MCT) disproportionately stabilized the invariant, whereas low-error GLUT isoforms collapsed rapidly under the cap—indicating that apparent “noise” often reflects hidden reservoirs of redundancy.

| Transporter |

Actual flux |

Predicted flux |

% Error |

Topological impact |

Collapse weight |

|

| GLUT1 |

120.0 |

121.8 |

+1.5 |

High flux, fragile under cap |

High |

0.32 |

| GLUT3 |

110.0 |

104.3 |

-5.2 |

Supports redundancy, easily neutralized |

Medium |

0.28 |

| LAT1 |

25.0 |

25.9 |

+3.8 |

High affinity, anchors Q

|

Medium |

0.12 |

| ASCT2 |

45.0 |

47.1 |

+4.7 |

Antiporter, spreads redundancy |

Low |

0.15 |

| MCT1 |

95.0 |

85.7 |

-9.8 |

Variable affinity, stabilizes invariant |

High |

0.25 |

| MCT4 |

80.0 |

74.8 |

-6.5 |

Export flux, redundancy backbone |

High |

0.23 |

6. Conclusions

This work reframes malignant robustness not as a mere surplus of transport capacity but as a topologically protected structure. By casting redundancy as an Euler obstruction within a flux bundle, we argue that resilience follows geometric constraints rather than purely biochemical ones. Within this framework, a PEG–sulfonate scaffold operates as a molecular inverse replica that drives a uniform radial contraction of normalized fluxes and effects the transition . Microscopically, sulfonate anchoring and steric occlusion produce a parallel reduction of ; mathematically, this implements cancellation of characteristic classes; translationally, it could neutralize adaptive redundancy within the scope of the present model and assumptions.

Scope and rigor. Our conclusions are derived from an effective topology on a parameter torus and synthetic datasets that the theory fits with high accuracy. These fits express model self-consistency, not experimental proof. Accordingly, the claims should be read as mutation-resilient within the model rather than strictly “mutation-proof” in biology. The effective-topology construction is an analogy that guides mechanism design; validating the mechanism requires independent wet-lab corroboration under prospectively defined endpoints.

Rules that invert intuition (model-derived). (i) High-flux channels appear fragile under global capping, whereas lower-flux routes disproportionately stabilize Q; (ii) Predictability in flux points to weakness, while variance often marks hidden reservoirs of redundancy; (iii) Influx can be dispensable if efflux preserves the obstruction; (iv) Symmetry collapses faster than asymmetry under uniform contraction. These statements are corollaries of the model and constitute hypotheses to be tested, not clinical claims.

Therapeutic principle. Global cancellation—formalized as —targets both fragile and stabilizing modes simultaneously. In practice this means designing interventions that shrink effective across transporter families in parallel rather than blocking single nodes. If confirmed empirically, such cancellation would be robust to common adaptive rewiring because it removes the invariant that confers robustness; until then, it remains a mechanistic proposal grounded in a mathematically consistent analogy.

Testable predictions and biomarkers. The theory yields concrete, falsifiable predictions: (1) There exists a critical occlusion beyond which collapses sharply while declines smoothly; (2) correlates with the weighted efflux capacity (MCT-dominant phenotypes require larger effective occlusion); (3) Under capping, elasticities obey across families; (4) Longitudinal measurements of multi-substrate fluxes should reveal a sigmoidal decrease of an order-parameter proxy , well-fit by . For (1)–(4), operational definitions (assay conditions, proxy construction, priors) must be preregistered to avoid post-hoc confirmation.

Translational considerations. Realizing the scaffold’s potential depends on delivery, PK/PD, and safety: depth of membrane coverage (effective ), residence time, off-target binding to non-malignant epithelia, complement activation, and clearance. Tumor heterogeneity, stromal barriers, and hypoxia-induced expression shifts must be integrated into dosing strategies and combination regimens. These constraints bound the feasible region in which uniform contraction can approximate the ideal inverse-replica limit.

In sum, topological neutralization offers both a diagnostic law and a design axis: quantify vulnerability by , compute collapse of invariants, and engineer molecular caps that enforce uniform contraction. The promise of this approach is conceptual clarity plus actionable metrics; its limitation is the current lack of in vitro and in vivo confirmation. Geometry may not replace mutation, but it can set the rules within which mutation operates—subject to empirical verification.

7. Future Works

From analogy to evidence. We will translate the effective-topology framework into assays and models that can confirm or refute its predictions:

In vitro flux tomography. Perform multiplexed uptake/efflux assays (glucose, amino acids, lactate) under graded capping to estimate and validate . Fit to the sigmoidal law and test for an abrupt slope change. Predefine acceptance regions for and power calculations.

Single-cell heterogeneity. Use flow cytometry and single-cell metabolomics to quantify dispersion in transporter expression and correlate with shifts in . Assess whether variable MCT/GLUT balances shift the predicted order of collapse. Control for compositional bias and batch effects.

Mechanistic binding studies. Measure Cap–PEG–S affinity to cationic/glycosylated motifs (SPR/ITC), map binding sites, and test how glycoediting (e.g., sialidase treatment) shifts effective occlusion at equal dose. Report binding stoichiometry and competing-ion sensitivity.

PK/PD and delivery. Engineer scaffold size/branching and charge density to maximize membrane residency and minimize off-target effects; model under realistic dosing and test sustained vs. pulsed regimens. Include bounds for complement activation and renal clearance.

Combination logic. Evaluate whether mild capping synergizes with selective inhibitors (e.g., MCT1/4 or LAT1) by lowering , converting partial redundancy into collapsible topology. Quantify synergy via Bliss/HSA with uncertainty.

Hematological malignancies. Extend to circulating cells with a time-dependent flux bundle ; test whether population-level redundancy collapses when the time-averaged occlusion exceeds a threshold. Model shear and plasma-protein binding.

Clinical proxy and biomarker. Develop a practical surrogate for (e.g., ratio of capped/uncapped FDG uptake plus lactate export under standardized conditions) and explore prognostic value. Specify calibration curves and inter-lab reproducibility.

Model refinement. We will: (i) relax the homogeneous-contraction assumption by introducing family-specific kernels ; (ii) couple the flux bundle to microenvironmental fields (pH, ) to capture adaptive shifts; and (iii) quantify uncertainty, reporting credible intervals for and with sensitivity to prior choices and identifiability.

Safety and ethics. Prior to clinical translation, immunogenicity, complement activation, and renal/hepatic clearance will be profiled; off-tumor capping in high-turnover tissues will be minimized via targeting ligands. All studies will adhere to prespecified stopping rules and data-sharing commitments.

If these studies support the central prediction—that global contraction trivializes the invariant sustaining redundancy—topological neutralization could mature from a guiding analogy to a therapeutically actionable law, with as a measurable decision point for dose and combination design.

Funding

This research received no dedicated external funding. Computational resources were provided by open-access platforms (Google Colaboratory) and the Cosmo Physics Organization, a non-profit independent research entity.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial or non-financial interests related to the content of this work.

References

- M. I. Khan, A. Javed, S. Shah, Synthesis and characterization of PEG-based sulfonated polymers for biomedical applications, J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 112 (2009) 2642–2650.

- L. Zhang, Y. L. Zhang, Y. Xie, H. Wu, PEG–sulfonate functionalization of nanoparticles: structural verification by NMR and FTIR, Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 102 (2013) 211–217.

- S. S. Pinho, C. A. S. S. Pinho, C. A. Reis, Glycosylation in cancer: mechanisms and clinical implications, Nat. Rev. Cancer 15 (2015) 540–555.

- M. Argenziano et al., Title of the article, Journal Name Volume (2019) pages.

- A. Tuccillo et al., Title of the article, Journal Name Volume (2014) pages.

- B. Jiang, A. B. Jiang, A. Bouhon, S.-Q. Wu, Z.-L. Kong, Z.-K. Lin, R.-J. Slager, J.-H. Jiang, Observation of an acoustic topological Euler insulator with meronic waves, Science Bulletin 69 (2024) 1653–1659.

- B. Jiang et al., Experimentally observed meronic acoustic Euler insulator, arXiv:2205.03429 (2022).

- H. Xue, Y. H. Xue, Y. Yang, F. Gao, Y. Chong, B. Zhang, Acoustic higher-order topological insulator on a Kagome lattice, Nat. Mater. 18 (2019) 108–112.

- R. Fleury, A. R. Fleury, A. Khanikaev, A. Alù, Floquet topological insulators for sound, arXiv:1511.08427 (2015).

- C. He et al., Acoustic topological insulator and robust one-way sound transport, arXiv:1512.03273 (2015).

- L. Peng et al., Phonons as a platform for non-Abelian braiding in layered silicates, Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 423.

- L. L. Peng et al., Multigap topology and non-Abelian braiding of phonons from first principles, Phys. Rev. B 105 (2022) 085115.

- X. Xiang et al., Demonstration of acoustic higher-order topological nodal loop semimetal, Phys. Rev. Lett. 132 (2024) 197202.

- Y. Zhu et al., Experimental realization of acoustic Chern insulator, Phys. Rev. Lett. (2018).

- W. J. Jankowski, Optical manifestations and bounds of topological Euler class, Phys. Rev. B 111 (2025) L081103.

- S.-H. Lee, Euler band topology in spin-orbit coupled magnetic systems, npj Quantum Materials (2025).

- W. J. Jankowski et al., Non-Abelian Hopf-Euler insulators and metamaterial realizations, Phys. Rev. B 110 (2024) 075135.

- R. Park et al., Experimental observation of non-Abelian topological acoustic semimetals and phase transitions, Nat. Phys. 17 (2024) 1239.

- H. Qiu et al., Minimal non-Abelian nodal braiding in ideal metamaterials, arXiv:2202.01467 (2022).

- M. Ezawa, Topological Euler insulators and their electric circuit realization, Phys. Rev. B 103 (2021) 205303.

- E. Cornfeld, Tenfold topology of crystals: unified classification of crystalline topological insulators and superconductors, Phys. Rev. Res. 3 (2021) 013052.

- M. Z. Hasan, C. L. Kane, Colloquium: topological insulators, Rev. Mod. Phys. 82 (2010) 3045–3067.

- X.-L. Qi, S.-C. Zhang, Topological insulators and superconductors, Rev. Mod. Phys. 83 (2011) 1057–1110.

- R. J. Slager, The space group classification of topological band-insulators, Nat. Phys. 9 (2013) 98–102.

- A. A. Soluyanov, D. A. A. Soluyanov, D. Vanderbilt, Smooth gauge for topological insulators, Phys. Rev. B 85 (2012) 115415.

- A. M. Turner, Quantized response and topology of magnetic insulators with inversion symmetry, Phys. Rev. B 85 (2012) 165120.

- H. Xue, Y. H. Xue, Y. Yang, B. Zhang, Topological acoustics, arXiv:2302.14429 (2023).

- H. Fang et al., Coupled topological rainbow trapping of elastic waves in 2D phononic crystals, Sci. Rep. 14 (2024) 67985.

- Q. Wu et al., Understanding of topological mode and skin mode morphing in non-Hermitian meta-lattices, J. Mech. Phys. Solids 193 (2024) 105907.

- G. Failla et al., Current developments in elastic and acoustic metamaterials science, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 382 (2024) 20240003.

- X. Fang, Advances in nonlinear acoustic/elastic metamaterials, Nonlinear Dyn. (2024).

- Breaking the limits of acoustic science: A review, J. Acoust. Soc. Rev. (2024).

- r: phononic metamaterials; arXiv:2303.01426 (2023).Topological phononic metamaterials: review, arXiv:2303.01426 (2023).

- Y. F. Zhu et al., Experimental realization of acoustic Chern insulator, Phys. Rev. Lett. (2018).

- F. Zangeneh-Nejad, A. F. Zangeneh-Nejad, A. Alù, Topological wave insulators: a review, C. R. Physique 19 (2018) 44–65.

- H. Xue et al., Acoustic higher-order TI on Kagome lattice (experiment), arXiv:1806.09418 (2018).

- X. Fang et al., Ultra-low, ultra-broad-band nonlinear acoustic metamaterials, Nat. Commun. (2017).

- Acoustic Metamaterials & Phononic Crystals: review, Crystals (2022).

- Y. Li et al., Topological design of soft substrate acoustic metamaterial, Wave Motion (2024).

- Acoustic metamaterials with large winding number, Phys. Rev. Applied (2021).

- Various topological phases and their abnormal effects of acoustic metamaterials, IDM2 (2023).

- M. Padlewski et al., Active acoustic SSH-like metamaterial, Phys. Rev. Applied (2023).

- Topological acoustics, Front. Mater. (2023).

- Valley-Hall acoustic insulator using soda cans, Sci. Adv. (2019).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).