Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

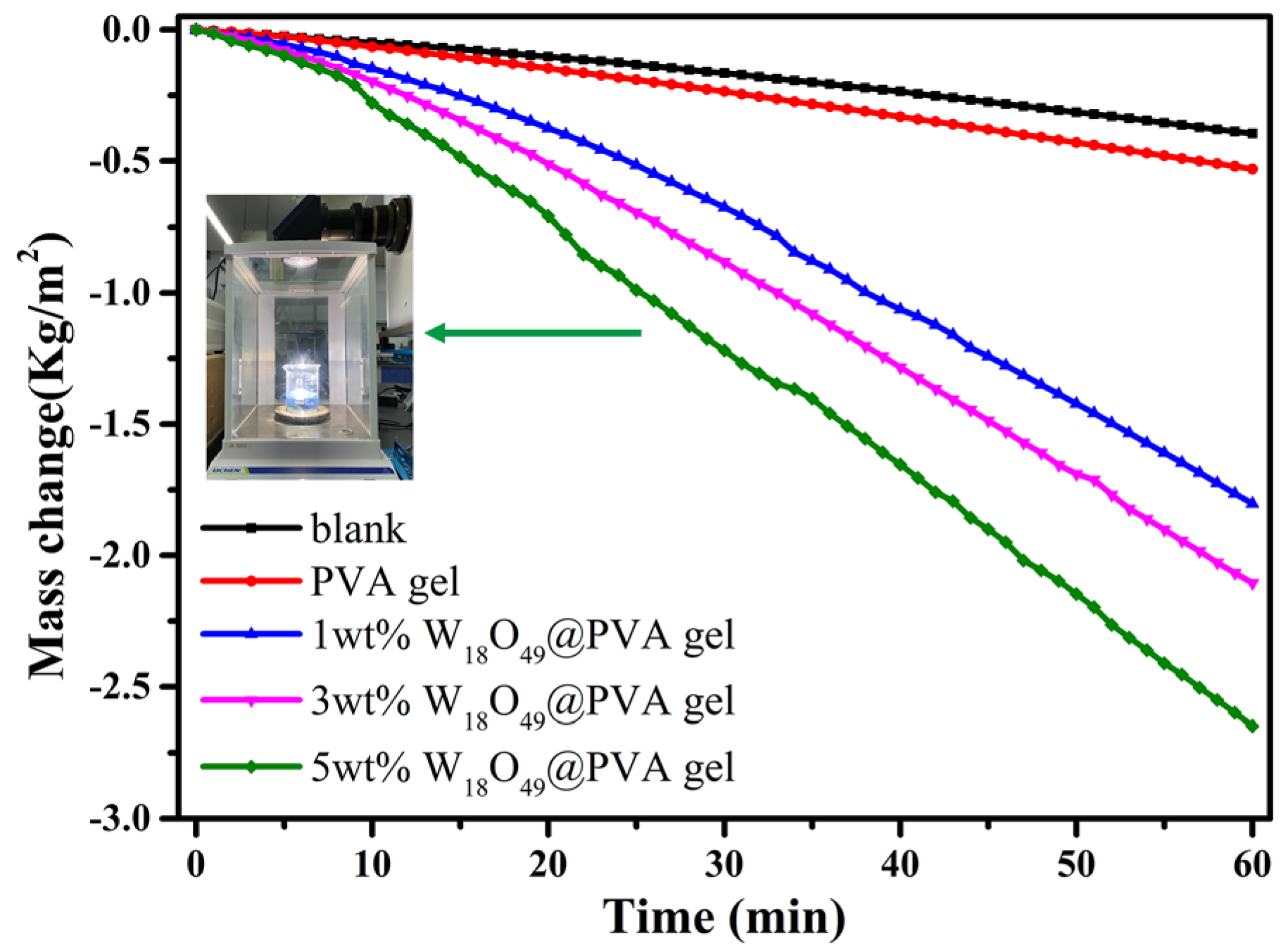

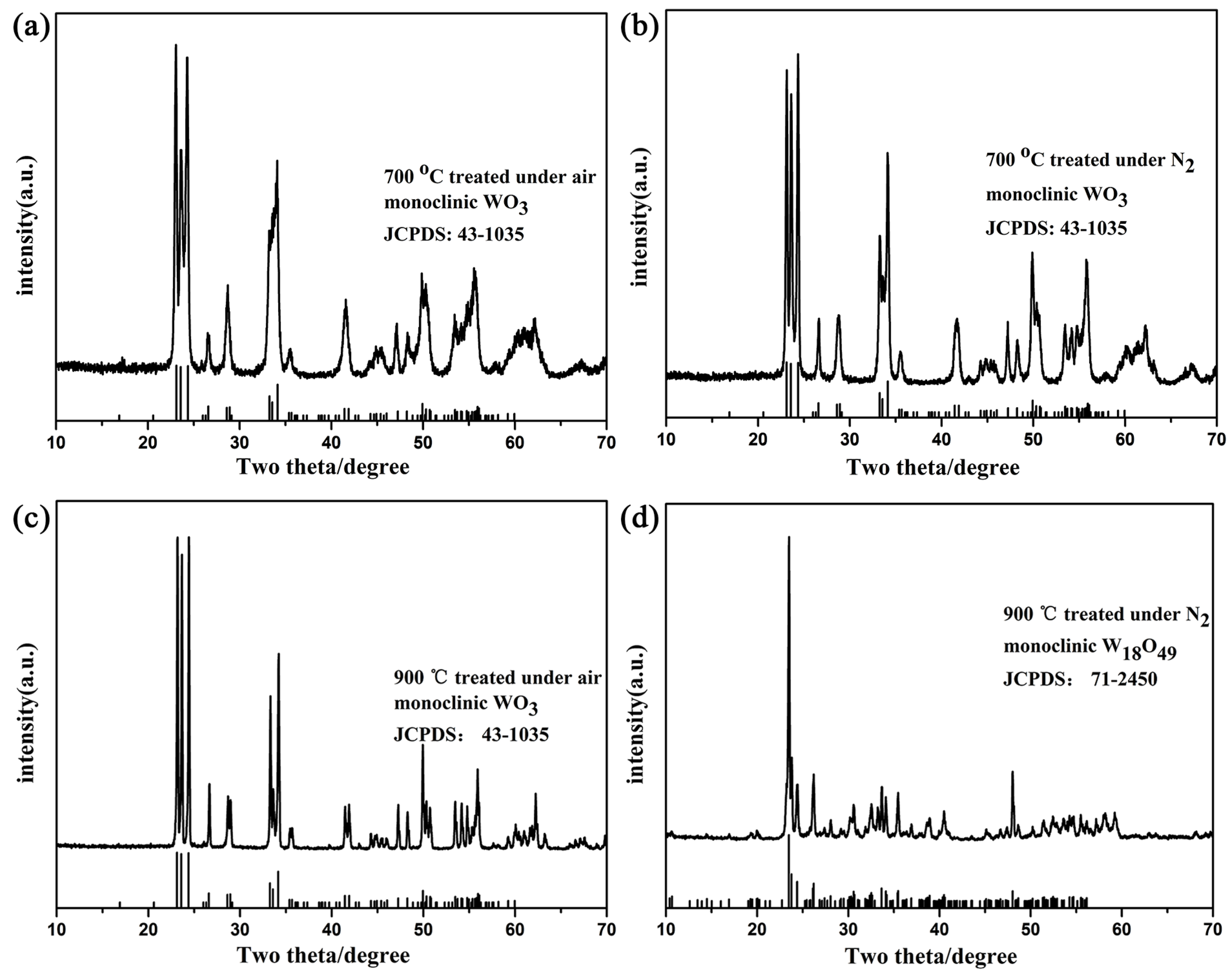

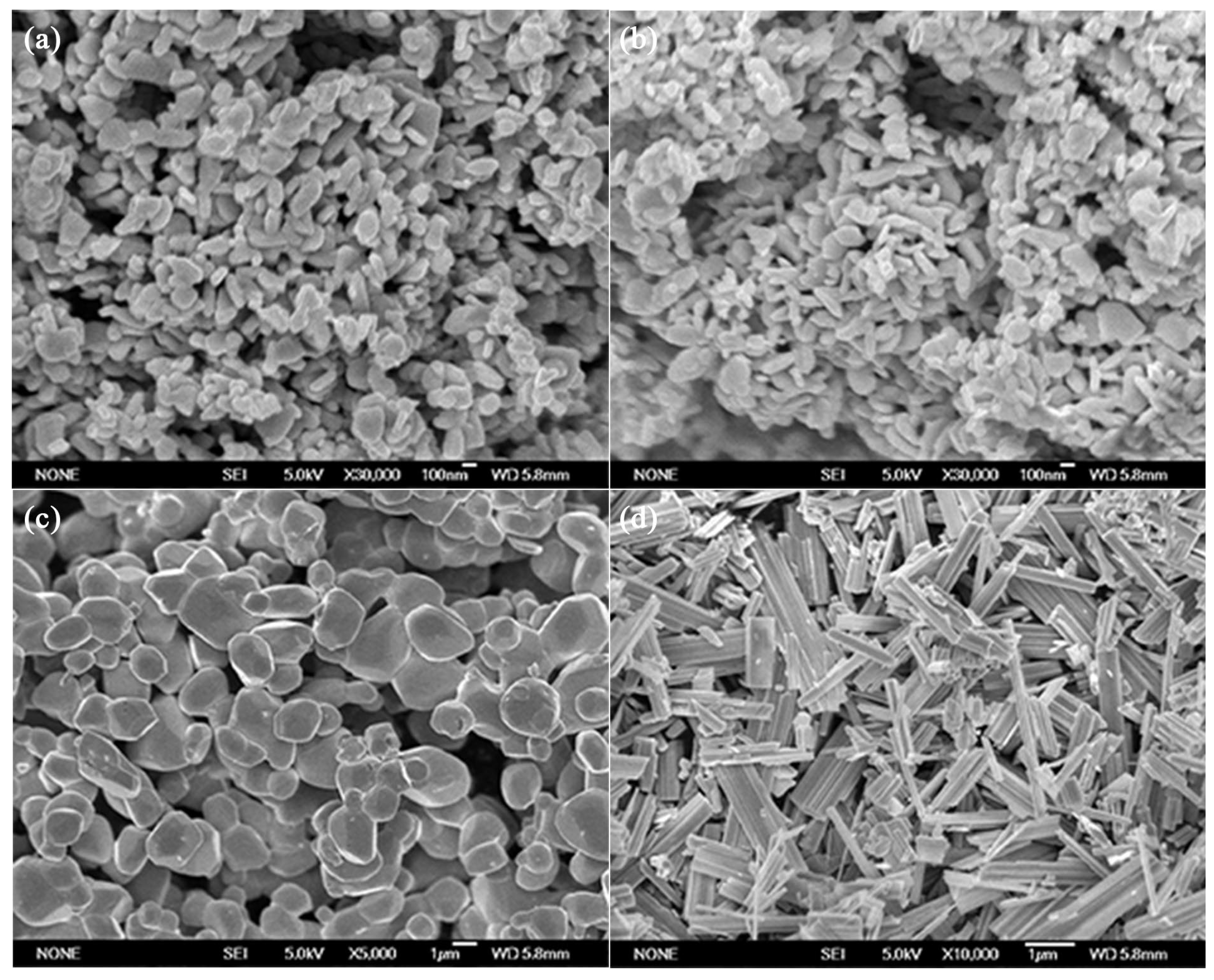

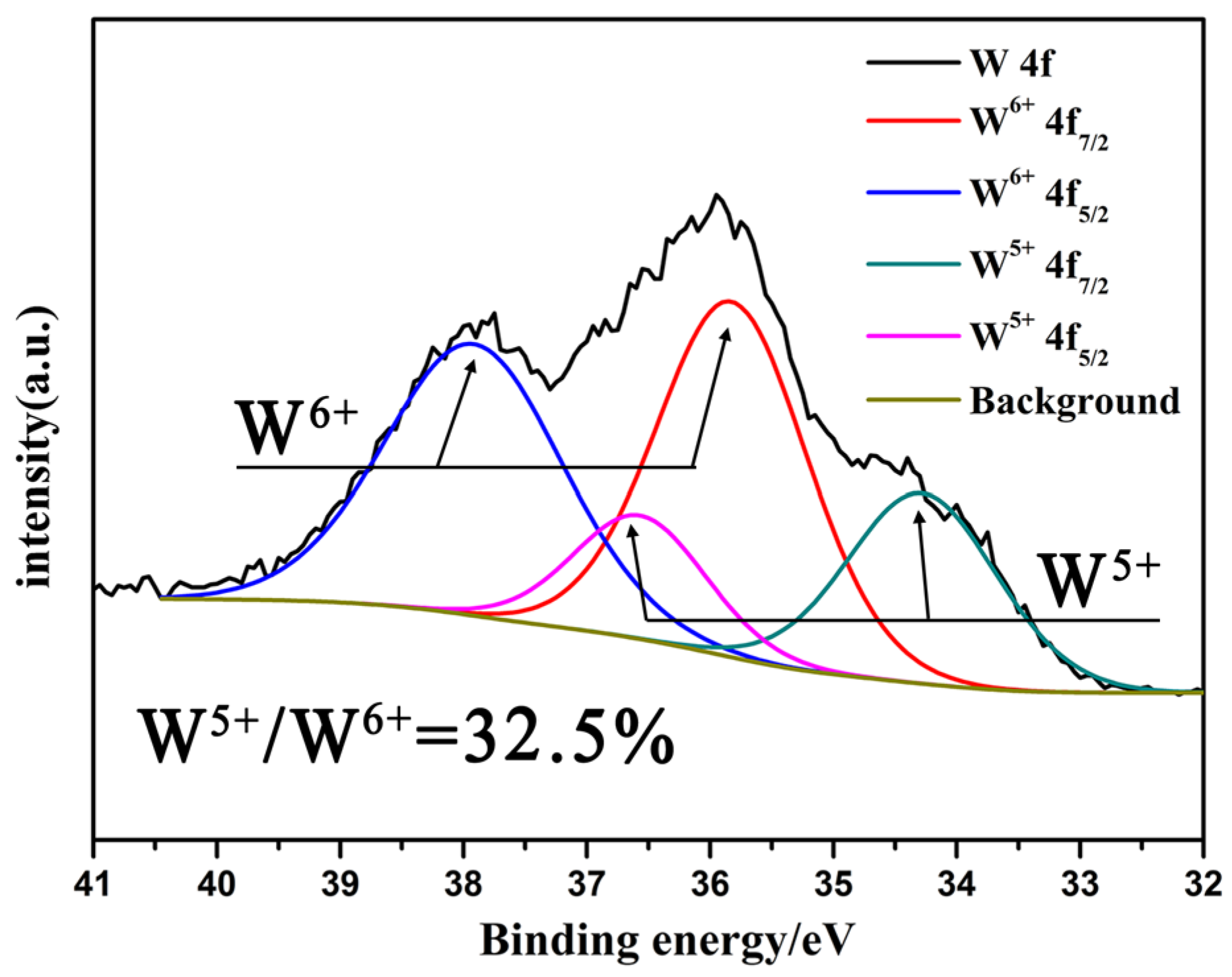

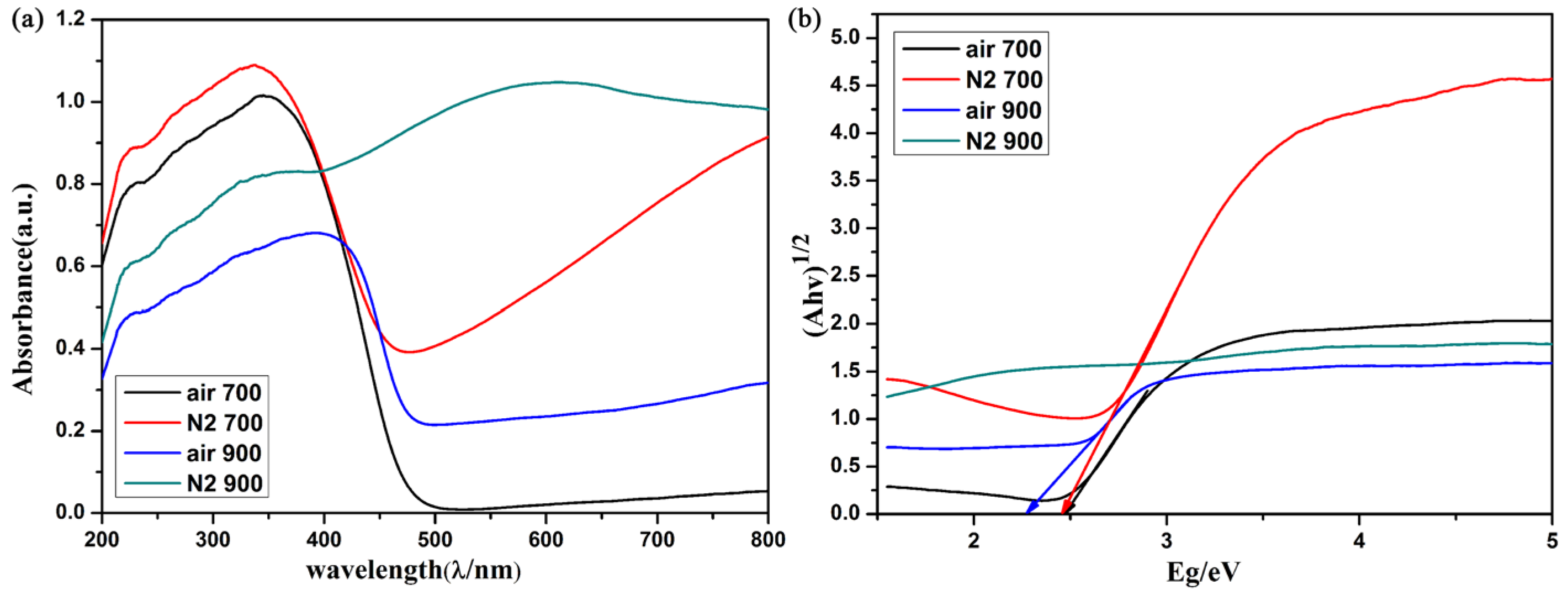

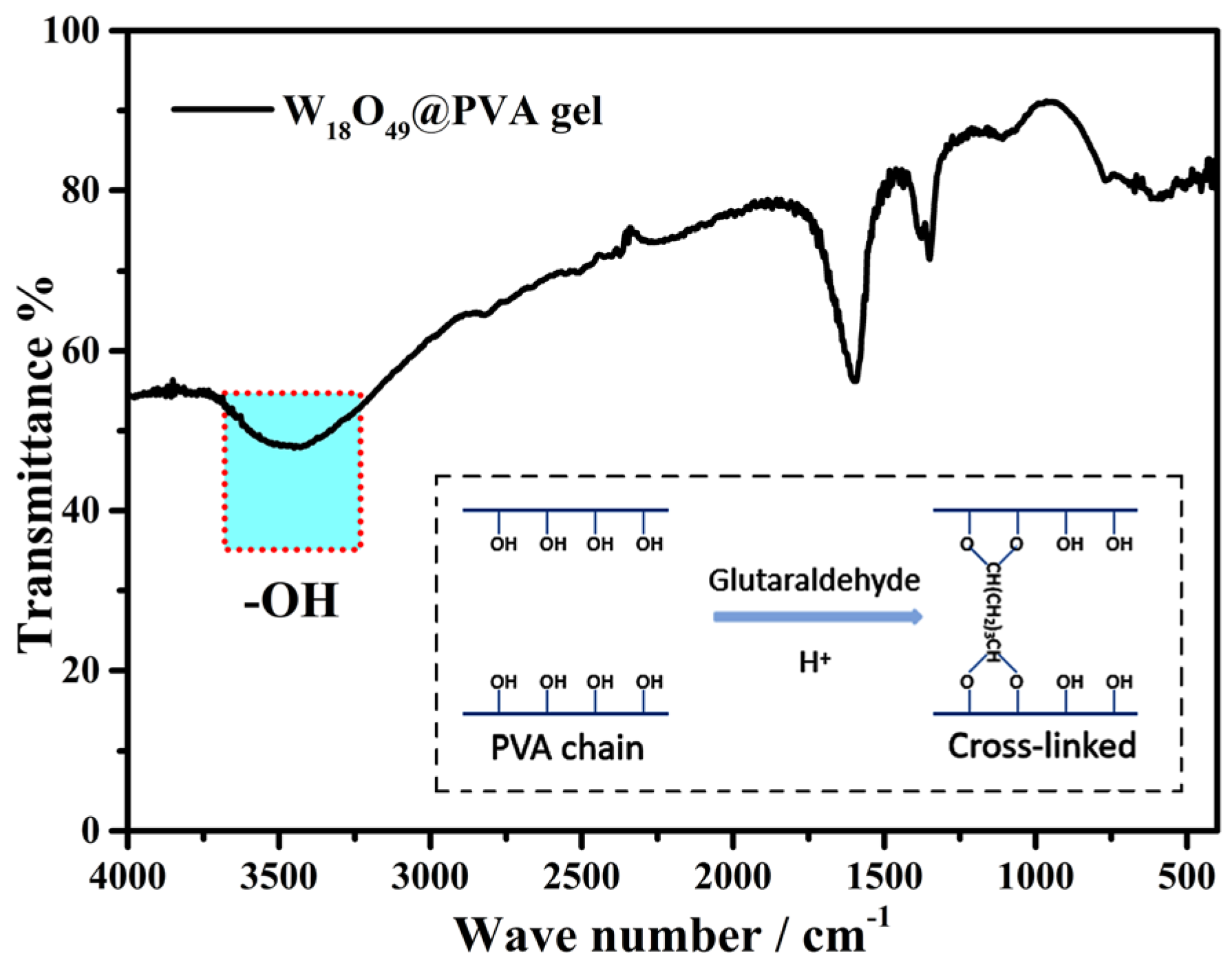

The oxygen deficient tungsten oxide W18O49 was synthesized through lattice oxygen escaping at high temperature in N2 atmosphere. The temperature and inert atmosphere were critical conditions to initiate the lattice oxygen escaping to obtain W18O49. The synthesized tungsten oxides were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) and ultraviolet-visible absorption spectroscope (UV-Vis). The composite gel was fabricated by the oxygen deficient tungsten oxide insertion into PVA-based gel, which was cross linked by glutaraldehyde. The gel was characterized by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and solar steam generation test. The result of the solar steam generation shows that the W18O49-PVA gel (steam generation rate 2.63 kg m-2 h-1) was faster than that of the pure PVA gel.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Procedures of the Composite Gel Synthesis

4.2.1. The Synthesis of Tungsten Oxide

4.2.2. Preparation of PVA Gel

4.2.3. Preparation of W18O49@PVA Composite Gel

4.2.4. Experiment of Solar Steam Generation

4.3. Characterization

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdullah, H., et al., A Brief Review of Emerging Strategies in Designing Interfacial Solar Steam Generation for Desalination, Water Purification, Power Generation, and Sea Farming. ACS Applied Energy Materials, 2025. 8(5):2663-2704.

- Zhang, Z., et al., Bio-based interfacial solar steam generator. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2024. 203:114787.

- Ibrahim, I., et al., Semiconductor photothermal materials enabling efficient solar steam generation toward desalination and wastewater treatment. Desalination, 2021. 500:114853.

- Yong Wang, et al., Plasmonic Photothermal Nanomaterials for Solar Steam Generation. Chem. Sci., 2025:Accepted Manuscript.

- Zhu, J., et al., Carbon materials for enhanced photothermal conversion: Preparation and applications on steam generation. Materials Reports: Energy, 2024. 4(2):100245.

- Hou, J., et al., Review on the structural design of solar-driven interfacial evaporation. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2025. 13(3):116462.

- Tang, Y., et al., Functional Aerogels Composed of Regenerated Cellulose and Tungsten Oxide for UV Detection and Seawater Desalination. Gels, 2022. 9(1).

- Sun, X., et al., Controlled assembly and synthesis of oxygen-deficient W18O49 films based on solvent molecular strategy for electrochromic energy storage smart windows. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2024. 499:156109.

- Xiong, Y., et al., Facile synthesis of hierarchical W18O49 microspheres by solvothermal method and their optical absorption properties. Discov Nano, 2024. 19(1):89.

- Yan, N.-F., et al., Recent progress of W18O49 nanowires for energy conversion and storage. Tungsten, 2023. 5(4):371-390.

- Qiu, Y. and Y. Wang, Controllable synthesis of W18O49 nanoneedles for high-performance NO2 gas sensors. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2023. 944:169199.

- Li, Y., Y. Bando, and D. Golberg, Quasi-Aligned Single-Crystalline W18O49 Nanotubes and Nanowires. Advanced Materials, 2003. 15(15):1294-1296.

- Chen, H., et al., PABA-assisted hydrothermal fabrication of W18O49 nanowire networks and its transition to WO3 for photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Advanced Powder Technology, 2018. 29(5):1272-1279.

- Gao, X., et al., Hydrothermal fabrication of W18O49 nanowire networks with superior performance for water treatment. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2013. 1(19):5831.

- Zhou, G., et al., Oxygen-Sensitive Nanomaterials Synthesized in an Open System: Water-Triggered Nucleation and Its Controllability in the Growth Process. Inorg Chem, 2025. 64(14):6811-6815.

- Nayak, A.K. and D. Pradhan, Microwave-Assisted Greener Synthesis of Defect-Rich Tungsten Oxide Nanowires with Enhanced Photocatalytic and Photoelectrochemical Performance. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 2018. 122(6):3183-3193.

- Guozhen Shen, et al., Electron-Beam-Induced Synthesis and Characterization of W18O49 Nanowires. J. Phys. Chem. C, 2008. 112(112):5856-5859.

- Li, J., et al., Porous polyvinyl alcohol/biochar hydrogel induced high yield solar steam generation and sustainable desalination. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2022. 10(3):107690.

- Li, N., et al., Bioinspired Flexible Composite Hydrogels for Efficient Solar Steam Generation and Stable Electricity Harvest. Nano Lett, 2025. 25(25):10072-10081.

- Shi, Y., et al., All-day fresh water harvesting by microstructured hydrogel membranes. Nat Commun, 2021. 12(1):2797.

- Tian, Y., et al., Versatile PVA/CS/CuO aerogel with superior hydrophilic and mechanical properties towards efficient solar steam generation. Nano Select, 2021. 2(12):2380-2389.

- Xu, X., et al., Full-spectrum-responsive Ti4O7-PVA nanocomposite hydrogel with ultrahigh evaporation rate for efficient solar steam generation. Desalination, 2024. 577:117400.

- Zhao, F., et al., Highly efficient solar vapour generation via hierarchically nanostructured gels. Nat Nanotechnol, 2018. 13(6):489-495.

- Zhang, J., et al., W18O49 nanorods: Controlled preparation, structural refinement, and electric conductivity. Chemical Physics Letters, 2018. 706:243-246.

- Fang, Z., et al., Photothermal Conversion of W18O49 with a Tunable Oxidation State. ChemistryOpen, 2017. 6(2):261-265.

- Parikh, D., H. Yadav, and S. Kapatel, Machine learning-based prediction of optical band gap in WO3 and its derivatives for semiconducting applications. Optik, 2023. 291:171310.

- Vemuri, R.S., M.H. Engelhard, and C.V. Ramana, Correlation between surface chemistry, density, and band gap in nanocrystalline WO3 thin films. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2012. 4(3):1371-7.

- He, M., et al., Remarkable enhancement of the nonlinear optical absorption of W18O49 by Cu doping. Materials Today Physics, 2024. 42:101357.

- Fang, Z., et al., A Flexible, Self-Floating Composite for Efficient Water Evaporation. Glob Chall, 2019. 3(6):1800085.

- Gao, M.-h., et al., Glutaraldehyde-assisted crosslinking in regenerated cellulose films toward high dielectric and mechanical properties. Cellulose, 2022. 29(15):8177-8194.

- Jeon, J.G., et al., Cross-linking of cellulose nanofiber films with glutaraldehyde for improved mechanical properties. Materials Letters, 2019. 250:99-102.

- Zhang, F., et al., Glutaraldehyde-assisted crosslinking for the preparation of low dielectric loss and high energy density cellulose composites filled with poly(dopamine) modified MXene. European Polymer Journal, 2024. 221:113526.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).