3.1. Material Responses

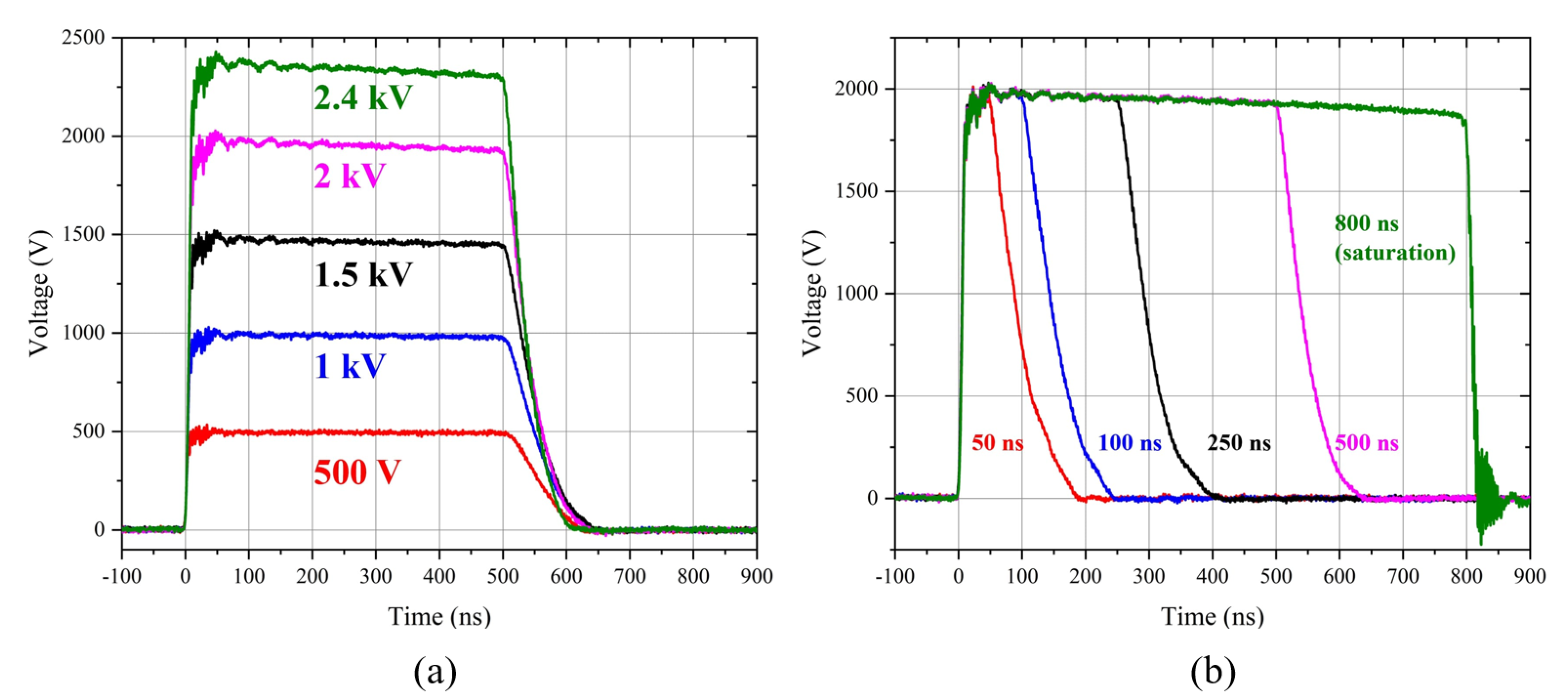

To meet the design requirement of a 500 ns pulse at 2.4 kV (1.2 mVs), the core must support a flux swing of at least 1.62 T without saturating, based on its physical dimensions.

To evaluate the performance of the cores under pulsed conditions, which more accurately reflect LTD operation, their magnetic behavior was tested under fast pulsed excitations. A simple pulse generator was used to apply voltages up to 2.4 kV to the cores, with a rise-time of approximately 20 ns. The core was first reset using a single-turn continuous DC reset current of 4 A before applying the high-voltage pulse. The reset utilizes an air core choke inductor (10 mH) to isolate the low-voltage DC supply from the high-voltage pulse. Due to MOSFET limitations, the maximum available current for testing was 200 A.

Using the current and voltage measurements on a single turn excited by a high voltage pulse from the pulse generator described previously, the average

H-field and

B-field throughout the core can be calculated using Equations (

3)–(

5).

Where

is the number of primary turns,

is the effective cross-sectional area of the core,

is the effective path length of the core,

is the core outer diameter, and

is the inner diameter of the core. For

= 1,

= 200 A, and an effective magnetic path length

of 0.218 m, resulting in a maximum H-field of approximately 900 A/m, using Equations (

3) and (

5).

Differentiating Equation (

4), with the assumption of square pulse excitation, yields the magnetization rate expressed by Equation (

6). The magnetization rate is an influential quantity that has been found to directly impact the behavior of the magnetic core [

10,

12,

20,

21].

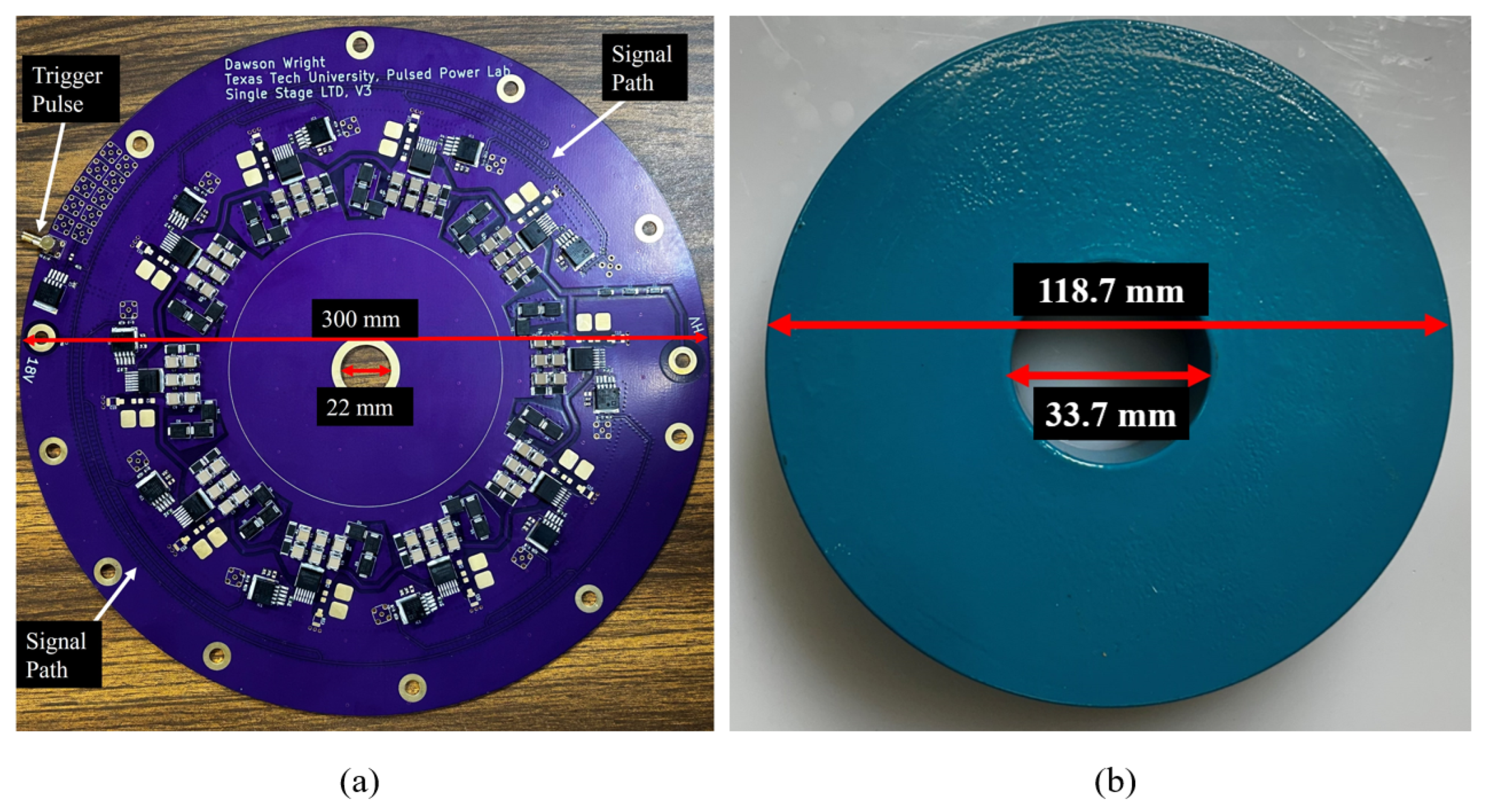

All cores were tested using a single primary turn for consistency with the one-turn topology of LTD, see

Figure 4. The cores reach saturation at different times despite resetting with the same 4 A current. This difference highlights the impact of the annealing process on magnetic properties, specifically the DC permeability.

The saturation times for each core align with their initial DC reset points, with the 3W-L core saturating first due to its lower total flux utilization, followed by the 3W-M and 3W-H cores. Upon reaching saturation, all of the cores exhibit a steep voltage drop, signaling the collapse of the effective inductance.

The behavior of each core under these conditions is illustrated in

Figure 5a. One feature of the B-H curve that must be considered under pulsed conditions is the initial push-out in H that is a result of the finite diffusion time, which limits the ability of the magnetic field to engage the magnetic material [

22]. From

Figure 5a it is evident that each core has a significant push out with the 3W-L, 3W-M, and 3W-H materials having an initial push out of ∼ 80 A/m.

Experimentally measured B-H curves of the MK cores with a continuous DC reset current of 4 A . (a) Comparison of MK cores with 2 kV charge voltage. The 3W-H achieves the highest flux at 2.25 T, while the 3W-L only reaches 1.85 T. Initial push-out in H for all cores is ∼ 80 A/m. (b) 3W-H magnetic core B-H curve widening with increasing pulse voltage.

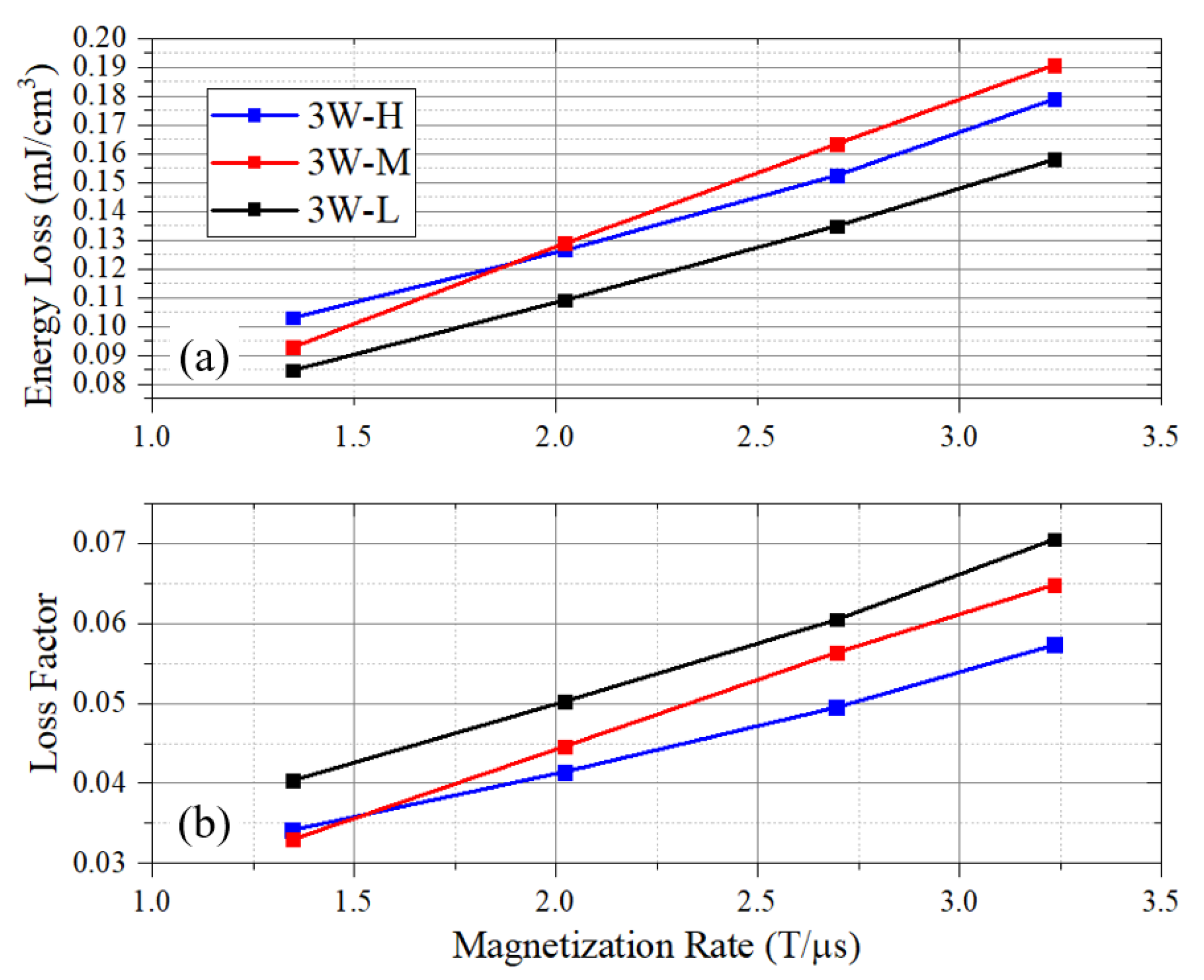

The energy loss of these magnetic materials must also be evaluated to determine the optimal core for the LTD. The energy loss for a magnetic material may be found by taking the area within the B-H curve, an expression for the energy loss of a magnetic core is given by Equation (

7).

As seen in

Figure 5b, the B-H curve of the magnetic material widens with increasing pulse voltage or magnetization rate; thus, the area within the curve increases, producing higher losses.

To be consistent with the magnetic core’s use case in an LTD where saturation should be avoided, the energy loss comparison was taken at 80 % of the total flux swing,

. As a figure of merit, the loss is normalized by the square of the total flux swing, yielding the loss factor in units of

. The energy loss factor is given by Equation (

8) [

23], where a lower loss factor reflects superior core performance.

At the upper end of the magnetization rates of interest, the 3W-L material has the lowest energy losses, followed by the 3W-H, with 3W-M being the most lossy, see

Figure 6a. However, considering the loss factor, the 3W-M outperforms the other two cores, see

Figure 6b.

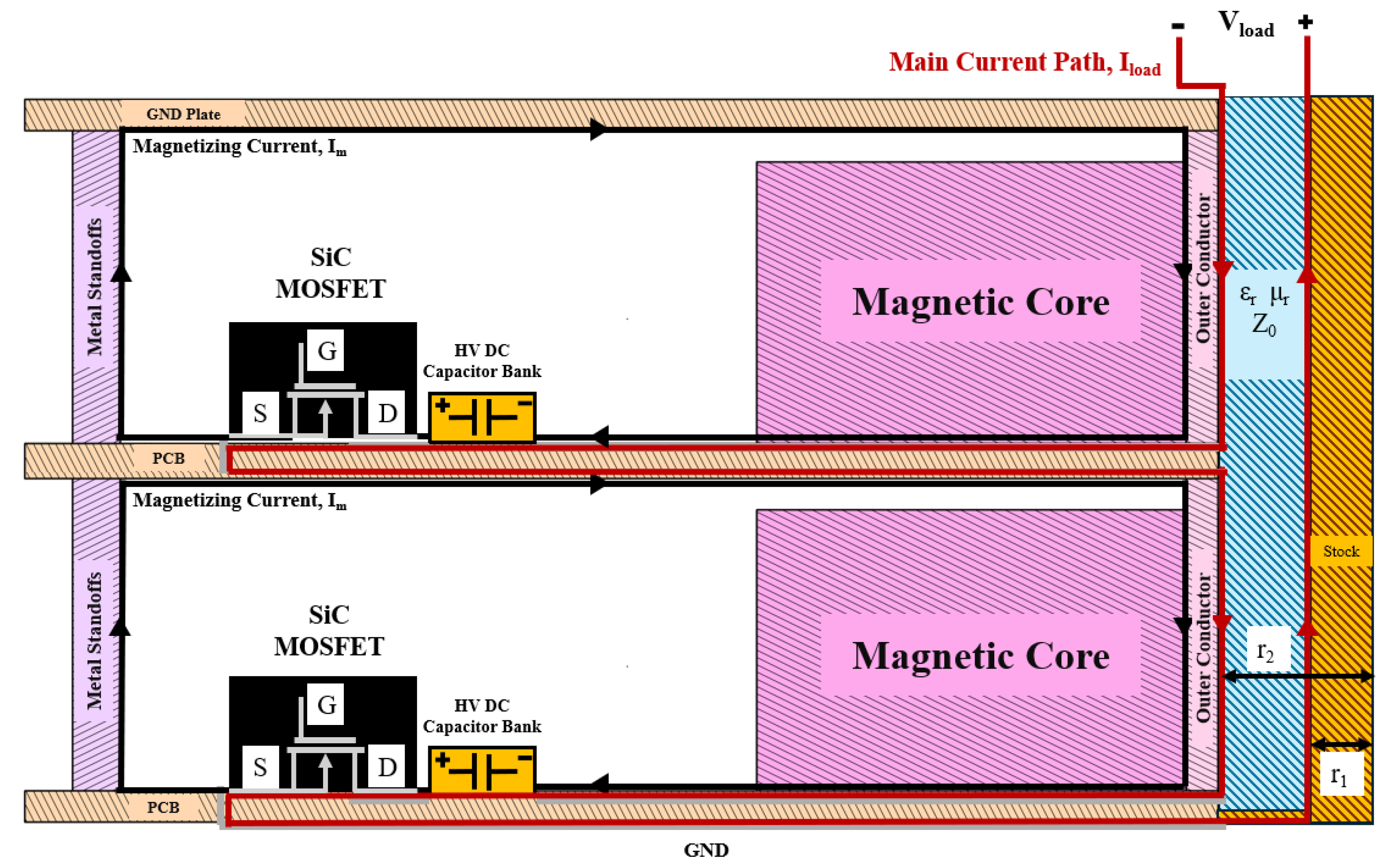

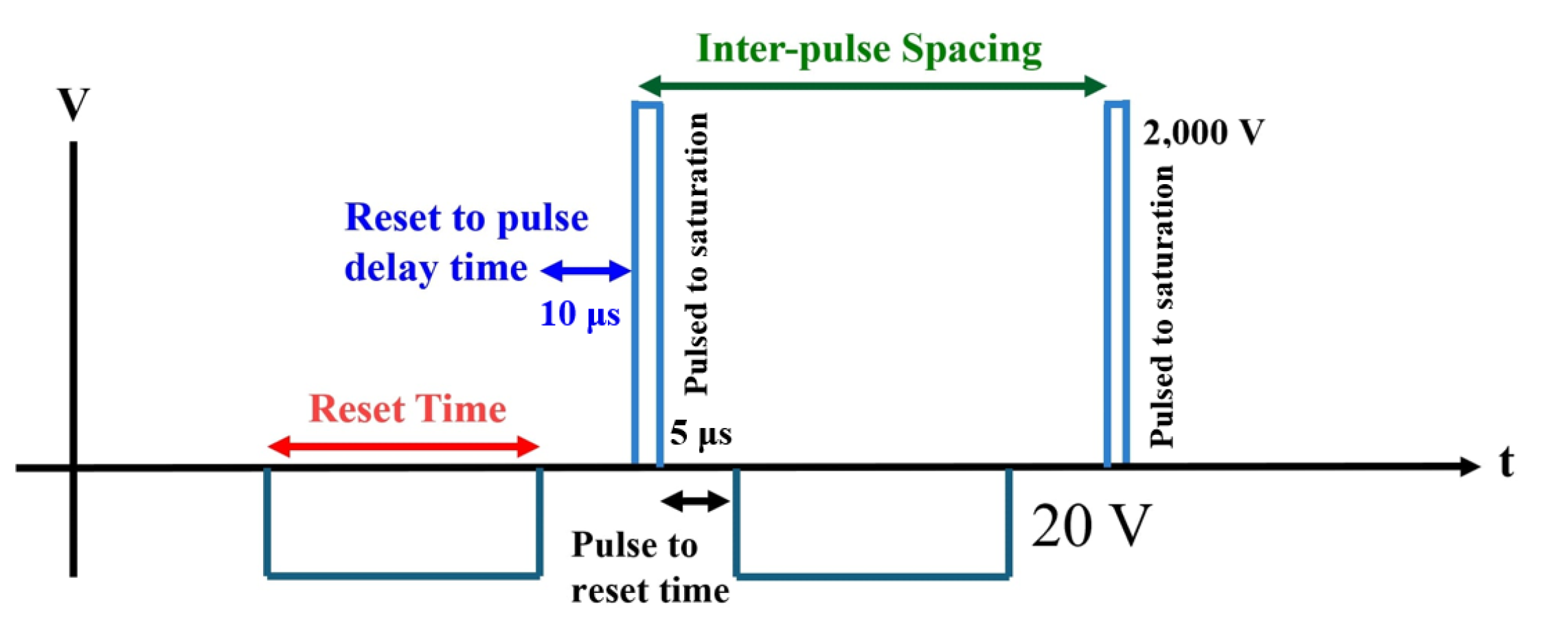

This work examines the distinction between continuous reset and active (pulsed) core reset strategies, see

Figure 7, with particular attention to the reset time required between repetition-rated pulses. At higher pulse voltages or with extended pulse durations, each pulse induces a substantial flux swing in the core, which must be reset prior to the subsequent pulse. This is not an issue for bipolar LTDs where there is an equal but opposite polarity pulse to reset the core [

16]. However, with space or cost limitations in mind, a single-polarity pulse with an active reset mechanism is a viable method to achieve repetition-rated operation. The stage-to-stage isolated pulsed reset allows for independent operation of each LTD stage, which is essential for waveform shaping. In contrast, the simplest DC reset technique utilizing a single choke inductor shared across all cores restricts independent stage-level control.

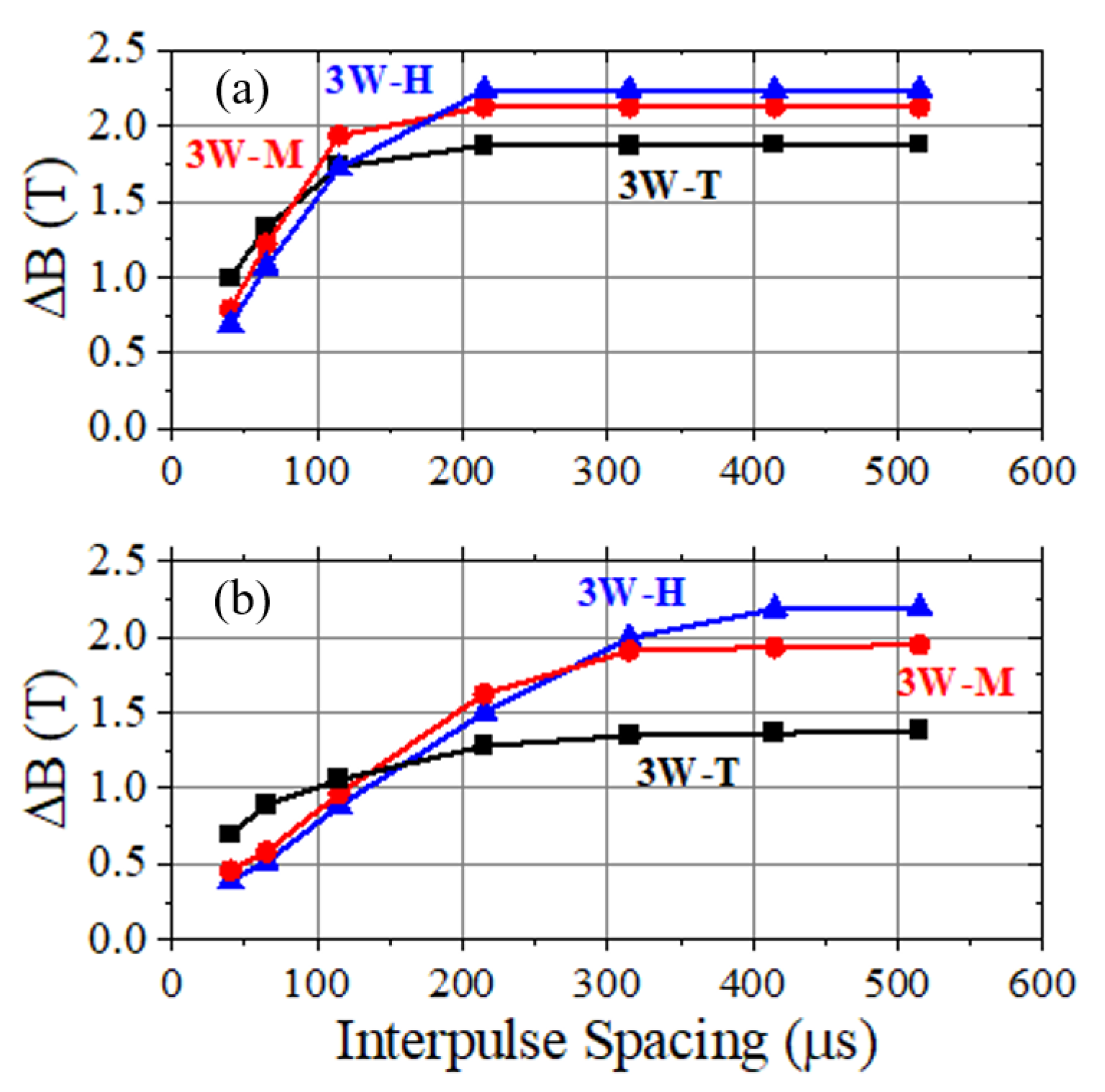

First, the continuous reset was evaluated at 4 A for each core; see

Figure 8a. Even at this reset level, none of the cores could utilize their full available flux swing of 2.36 T. The 3W-H core came closest, reaching 2.2 T after approximately 200

s. Initially, the 3W-L core exhibited the highest recovery flux at 40

s, but the other cores surpassed it by 100

s. All cores reached their total available flux after 200

s, corresponding to a 5 kHz repetition rate. However, suppose the core is not fully saturated and operates within 1 T flux swing. In that case, the maximum repetition rate would increase to approximately 20 kHz, demonstrating the trade-off between flux utilization and achievable pulse repetition rate.

After continuous reset testing, active reset was evaluated in the following manner: an initial reset pulse applied to the core, followed by a high-voltage pulse to drive the core into saturation. This sequence was repeated with a second reset and high-voltage pulse to again saturate the core, as illustrated in

Figure 7. The reset board was charged to 20 V with current limited to 4 A. The second high-voltage pulse was measured with varying reset times, and total flux swing calculated to quantify the extent of core reset achieved during the reset pulse.

The time delay between the reset pulse and the high-voltage pulse is set to 10

, ensuring the reset board turns off completely before the high-voltage pulse is applied. Similarly, a 5

delay is introduced between the high-voltage pulse and the next reset pulse. These delays add 15

to the inter-pulse spacing. The reset time is varied from 25

to 500

, where increasing this time no longer provides additional flux swing. The maximum flux achieved during the second high-voltage pulse is plotted against inter-pulse spacing in

Figure 8b.

The pulsed reset underperformed in all cases compared to the continuous reset, primarily due to the additional time delay between the reset and high-voltage pulse. This extra delay allows for natural flux relaxation towards , reducing the maximum achievable flux. The effect is most pronounced in the 3W-L core, as its lower remanent flux makes it more susceptible to natural reset effect.

In both reset methods, the 3W-H core exhibits the highest available flux at a reset of 4 A, reaching approximately 2.2 T in both cases. The continuous reset method achieves a slightly higher maximum usable flux than the pulsed reset, and it also reaches complete core reset twice as fast. This demonstrates that while both methods can achieve similar total flux swings, the continuous (DC) reset is generally faster when using similar reset voltage and currents. As a result, DC reset is the preferred approach for high-repetition-rate LTD applications, where space limitations do not discourage the use of large choke inductors. Alternatively, the reset voltage amplitude could be increased. One estimates that roughly a doubling of the amplitude will reset the core in a similar time as the 4 A DC case.

Based on the evaluations described previously, the 3W-H core emerges as the best choice for the LTD, as it provides the largest total flux swing, the lowest energy loss factor at the higher magnetization rates of interest, and similar reset times compared to the other cores with the continuous and pulsed reset techniques. The 3W-M material performed very similar to the 3W-H throughout this evaluation and would also perform well as a LTD magnetic core. Although the 3W-L core underperformed relative to the other two cores during evaluation, its low ratio enables a flux swing of ∼ 1.2 T per pulse without requiring reset circuitry - an advantage in applications where implementing core reset is impractical.

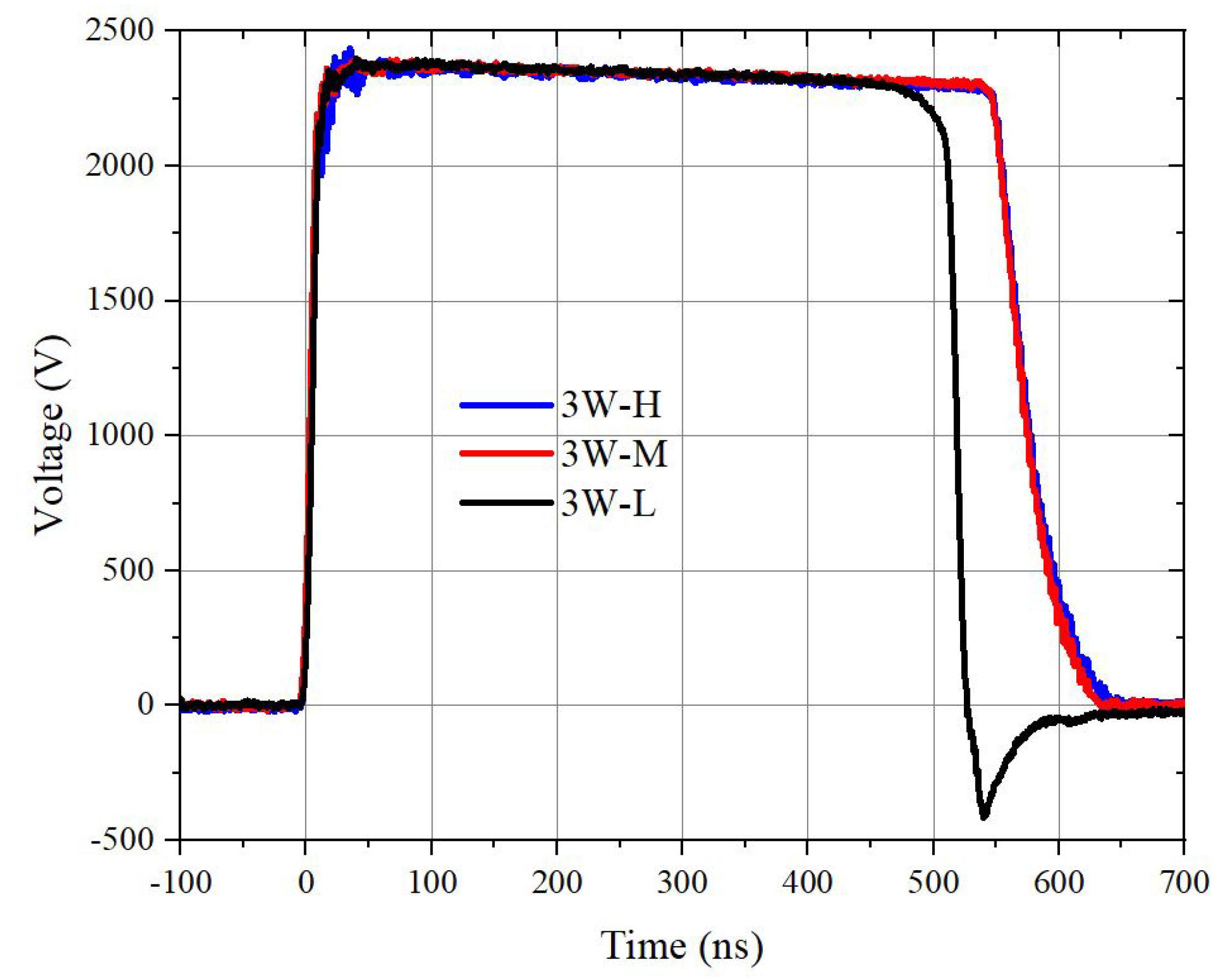

3.2. Single Stage Testing

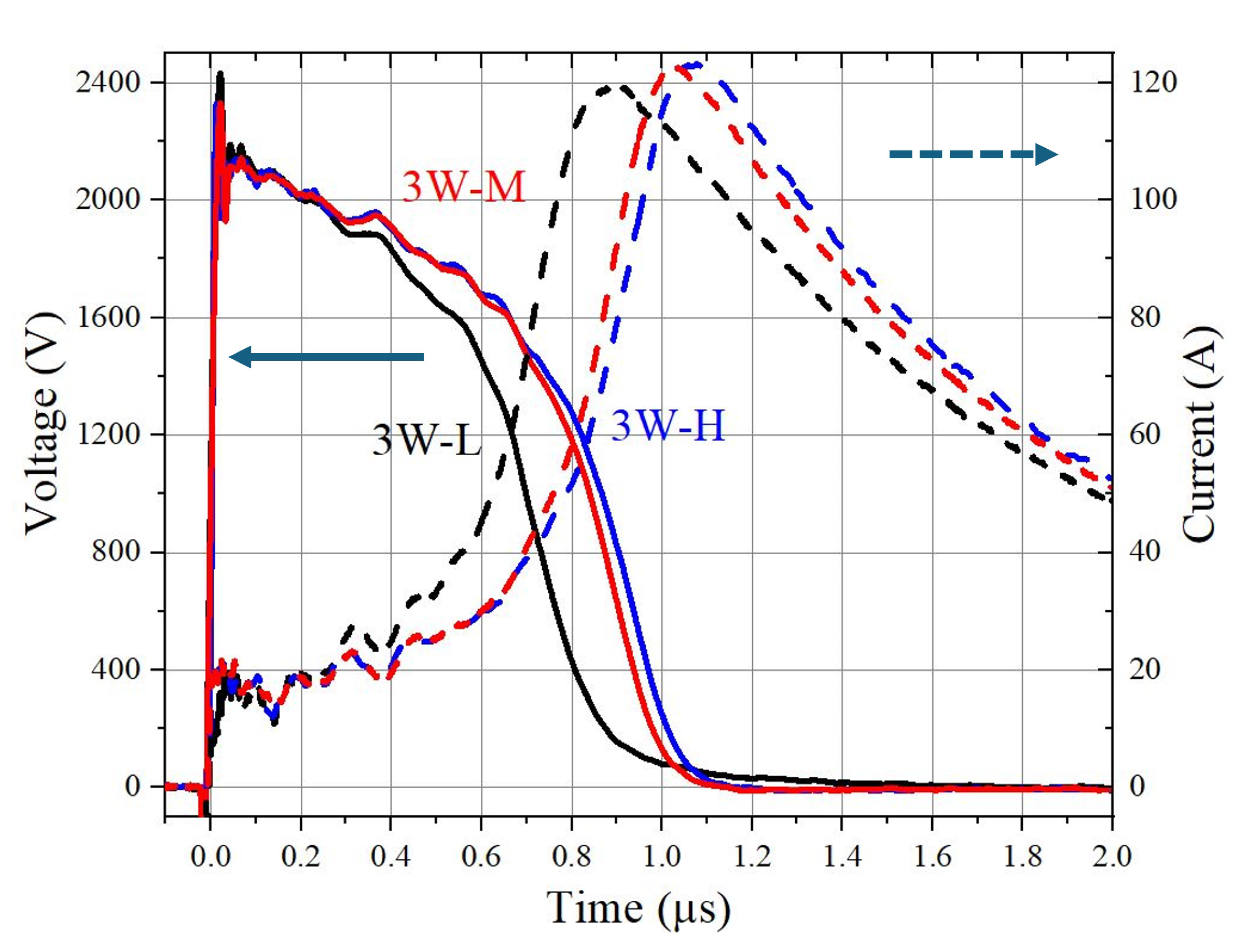

Following individual characterization, the cores were integrated into the LTD system to evaluate their influence on overall performance, including rise-time, output pulse shape, and system efficiency under practical operating conditions. A statistical comparison based on 100 shots with a 50

load was used to assess each core’s average voltage amplitude during the pulse flat-top and its rise-time, revealing negligible differences. Representative waveforms at 2.4 kV for each core, shown in

Figure 9, illustrate nearly identical profiles. The only notable distinction is that the 3W-L core saturates earlier due to its lower available flux swing for a given reset current.

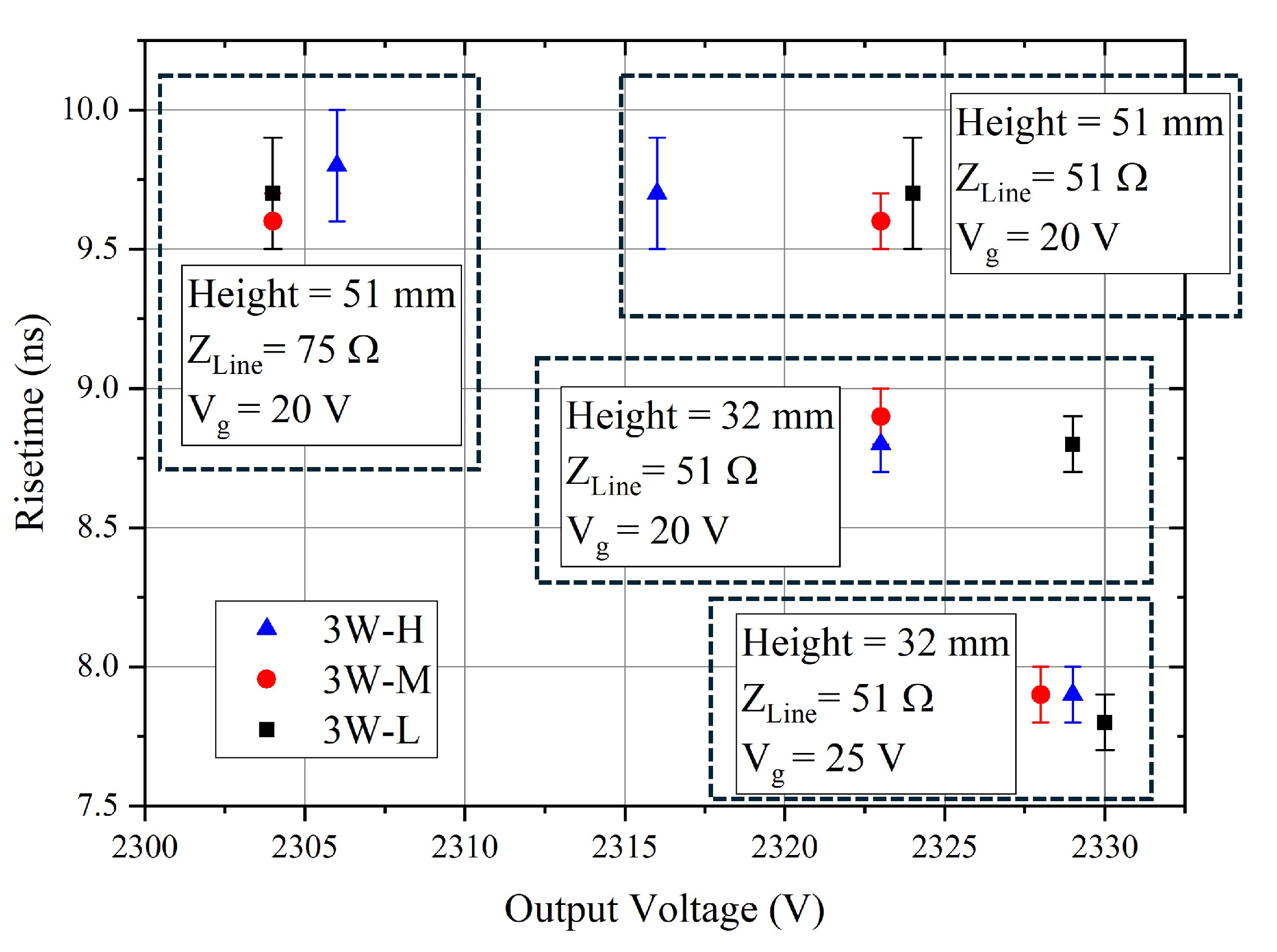

To assess the LTD’s rise-time sensitivity to switching speed, the MOSFET gate voltage was varied - a straightforward method for influencing switching behavior. While advanced gate-boosting techniques exist to mitigate parasitic inductance and capacitance effects [

2,

24,

25,

26,

27], this study focused on direct gate voltage adjustment. Results show a clear reduction in rise-time with increased gate voltage: from 34.4 ns at 10 V to 7.9 ns at 25 V, see

Table 3. Voltages below 10 V were insufficient for full MOSFET activation. At higher speeds, parasitic elements introduced ringing lasting for ∼ 30 ns before the output voltage amplitude settled.

With the switching characteristics established, attention was then directed toward the transmission line section of the LTD, specifically the influence of insulation material and geometry. Variations in dielectric type, stalk height, and diameter were examined to assess their impact on impedance matching and pulse fidelity. Initially, a 6 mm (1/4 in.) diameter stalk operating in air yielded a characteristic impedance of approximately 75

(Equation (

2)). Replacing air with PTFE (

,

) reduced the impedance to 51

. Although this change had no measurable effect on rise-time, it resulted in a modest increase in average voltage amplitude—from 2305 V to 2320 V — across all core types. This improvement is attributed to better impedance matching with the 50

load, enhancing power transfer and reducing reflection losses.

To further explore geometric influences, the height of the single-stage LTD structure was also evaluated. While the 26 mm core height sets a lower bound, the initial system height of 50.8 mm (2 in.), chosen somewhat arbitrarily during early development, was reduced to 31.75 mm (1.25 in.). This reduction led to a measurable improvement in rise-time, though it had minimal effect on average voltage amplitude. The combined effects of these and previously discussed parameter changes are illustrated in

Figure 10.

The results show that when the single stage LTD is shorter and the MOSFET gate is driven with the maximum rated voltage, the rise-time decreases. Additionally, impedance matching improves the average flat-top voltage over the non-impedance matched case. Furthermore, shot-to-shot variations are reduced, improving the consistency of the LTD output.

A complete statistical analysis is provided in

Table 4, presenting the 200-shot averages for flat-top voltage, current, rise-time, and jitter. At a 500 V charging voltage, the rise-time is approximately 4.5 ns, and as the voltage increases to the maximum of 2.4 kV, the rise-time increases to 7.9 ns. Jitter is kept relatively constant regardless of voltage. A sweep of input voltages and pulse widths was conducted under these optimized conditions, with the results presented in

Figure 11.

3.3. 10-Stage Results

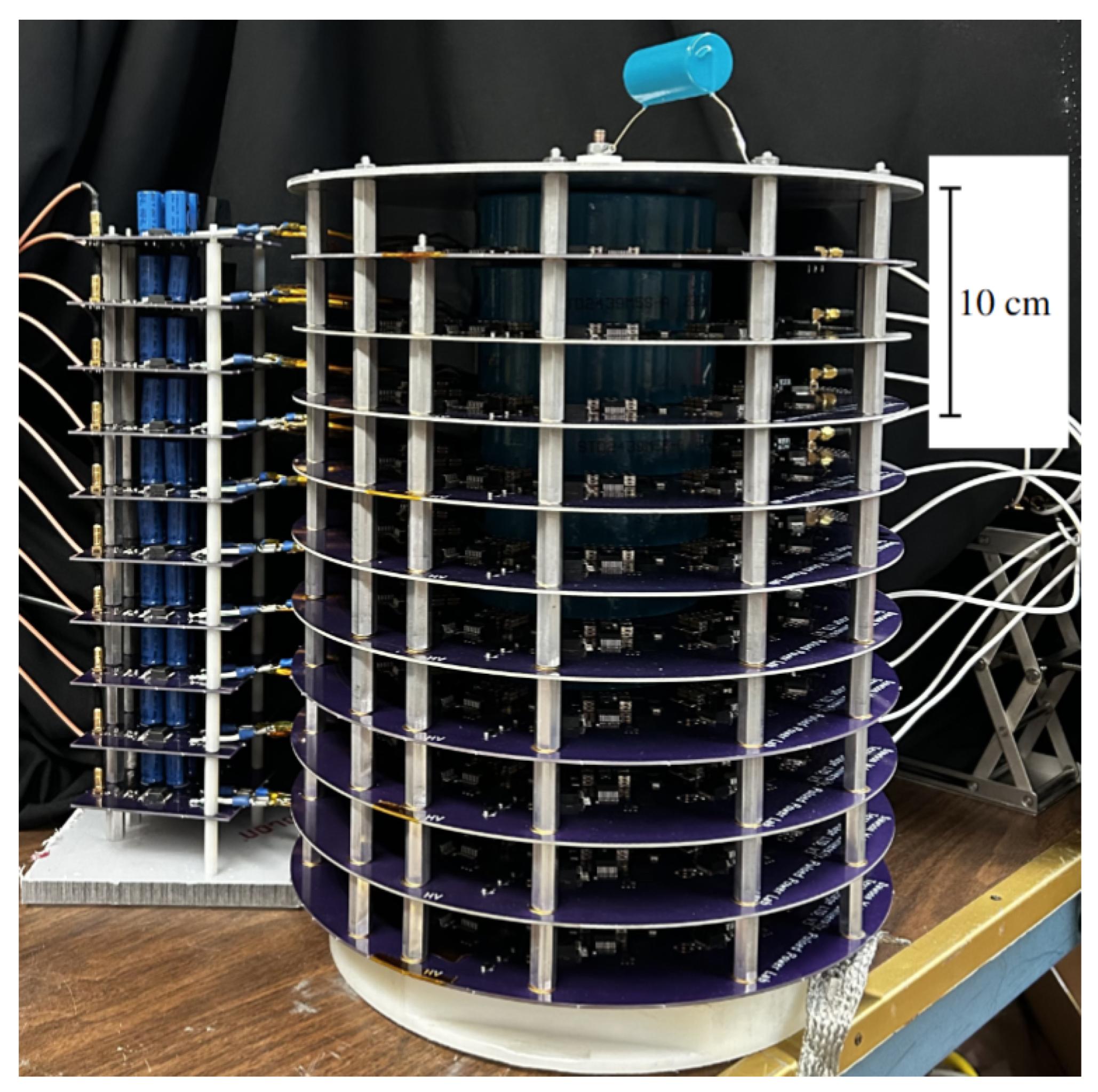

With single-stage performance fully characterized, the study progressed to evaluating the complete 10-stage LTD system. When stacked, the total system capacitance decreases since the LTD charges in parallel but effectively discharge in series, leading to an effective capacitance of . For the 10-stage setup, this results in a capacitance of one-tenth that of a single stage.

The pulsed reset boards were attached with a single turn winding around core of each stage, as shown in

Figure 12. To evaluate the voltage output of the full 10-stage LTD, testing was conducted by sweeping the charging voltage from 500 V to up to 2.4 kV in 500 V increments. The fully assembled LTD has a total height of 35.5 cm and a width of 40.5 cm, including the attached pulsed reset boards.

Based on the results of the magnetic core evaluation and single-stage LTD testing, the following parameters were chosen for the best performance: the 3W-H core was used for its higher flux availability compared to the other cores, PTFE dielectric was used as a center stalk insulation material which aided in impedance matching, a shorter overall height was selected to increase rise-time, and a gate drive voltage of 25 V was used to minimize rise-time.

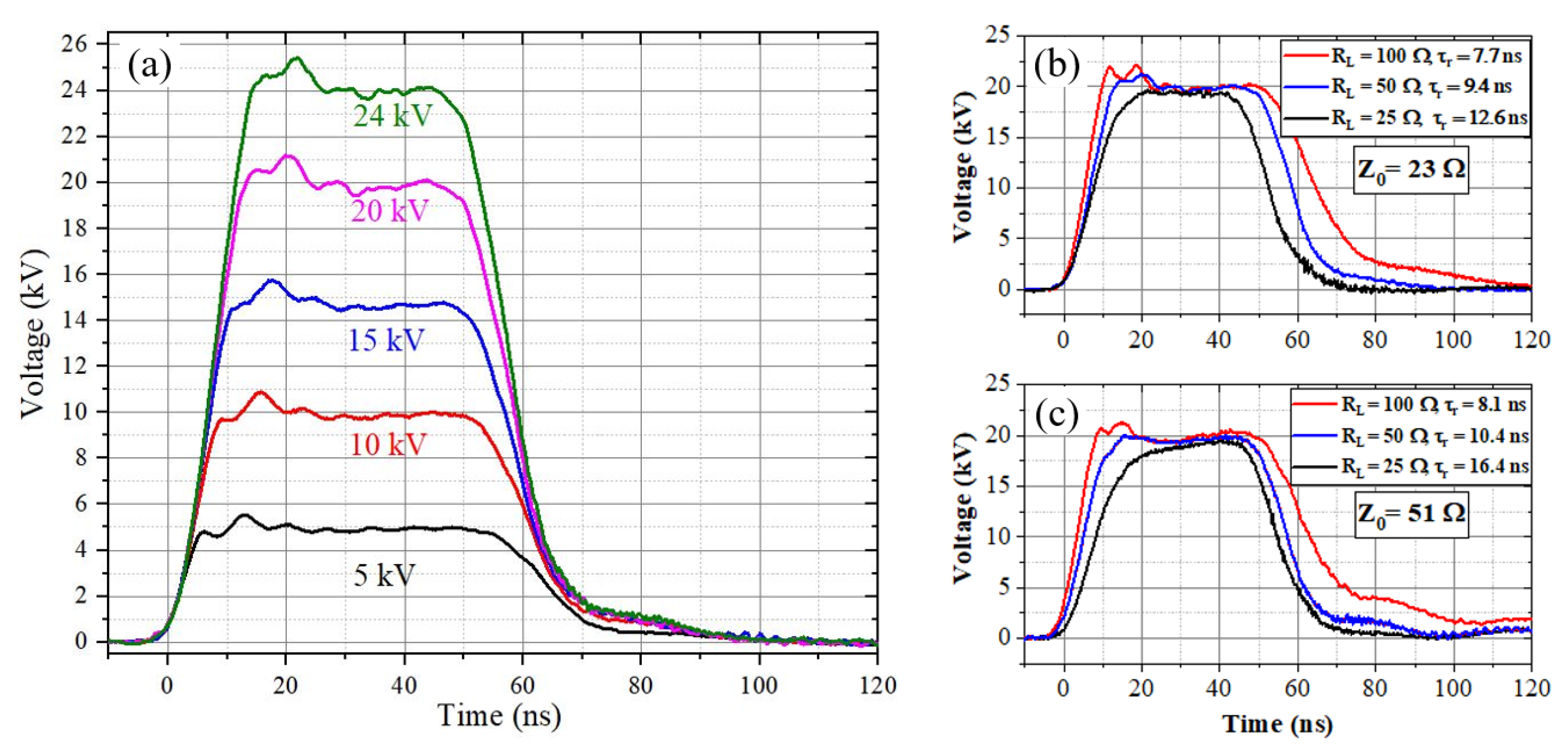

The results for the 10-stage LTD operating with a 12.7 mm (1/2 in.) diameter stalk and PTFE dielectric (

,

) with a 50

load are presented in

Figure 13a. A voltage overshoot is observed on the leading edge of the pulse, which quickly settles into a stable flat-top. At 24 kV, the FWHM pulse width is 56 ns, and the rise-time is 10 ns. The peak instantaneous power reaches 13 MW, while the average flat-top power over the duration of the pulse is 11.3 MW. The SSLTD developed in this work performs quite well in comparison with others reported in literature, see

Table 1. The 24 kV output voltage achieved is slightly lower than the 29 kV reported in [

4]; however, the SSLTD presented here delivers over twice the current and has a significantly faster switching speed. It is also capable of driving a lower load impedance of 25

, and demonstrates the fastest dV/dt switching rate of 2.4 kV/ns, outperforming the rest of the devices outlined in

Table 1, with the next best at 1.42 kV/ns [

5]. The maximum pulse width at the maximum output voltage of 24 kV is just over 500 ns, limited by saturation of the cores. The minimum pulse width is approximately 50 ns, constrained by the cumulative propagation delays of the gate drivers in the trigger signal path. A summary of the statistical averages for the system is provided in

Table 5.

The impact of transmission line impedance on voltage waveform shape and rise-time was examined for three different stalk characteristic impedances: 6

, 23

, and 51

, as shown in

Figure 13b,c. In

Figure 13b, a sweep of load resistances with

reveals that the 100

load produces a noticeable voltage overshoot at the front of the pulse, while the 25

load does not. This overshoot is likely caused by the impedance mismatch between the characteristic impedance of the center stalk,

, and the load. The similarities in voltage waveforms for the

,

and

,

configurations shown in

Figure 13b,c, both with approximately

support this claim.

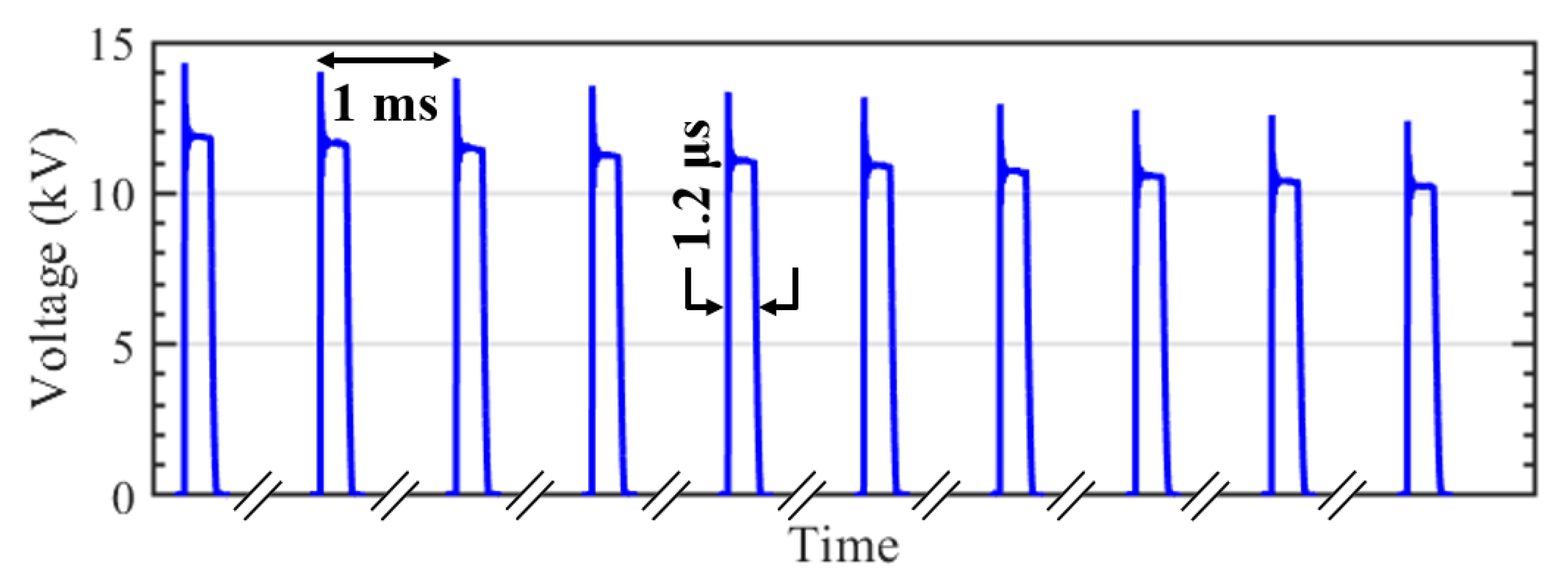

Having characterized the influence of transmission line parameters on pulse behavior, the next focus was on evaluating the full 10-stage LTD system under repetition-rated operation. Using a 6 mm stock diameter and PTFE dielectric (), this test aimed to determine the maximum achievable repetition rate while maintaining a significant flux swing in the magnetic cores for each pulse.

Due to limitations in the LTD’s charging capabilities, specifically the limited current capacity of the power supply, the repetition-rate evaluation was conducted in bursts of 10 shots into a 10

load. The active (pulsed) reset scheme used for this evaluation was the same as outlined in

Section 3.1. The large load resistance of 10

minimizes voltage droop on the energy storage capacitors, with losses dominated by the magnetic cores (∼180 mJ per pulse), while approximately 20 mJ per pulse is dissipated in the load resistor. A short burst of pulses opposed to continuous repetition-rated operation also eliminates the thermal concerns that arise with the relatively high average power output. A simple method to overcome the charging limitations and achieve a longer burst sequence is to add a large buffer capacitor on the high-voltage power rail. This capacitor allows the discharge capacitors to recharge between subsequent pulses, extending the burst operation.

The LTD was charged to 1.2 kV, with each pulse having a pulse width of 1

, correlating to a flux swing of approximately 1.8 T. Based on previous results outlined in

Section 3.1, the minimum inter-pulse spacing that should be expected would be around 300

, correlating to a pulse repetition frequency of 3.3 kHz.

Figure 14 shows an example voltage waveform from a 10 shot burst with a charge voltage of 1.2 kV and an inter-pulse spacing of 1 ms.

The observed pulse to pulse droop is due to the limited capacitor charging speed and could be overcome or minimized with a more aggressive charging scheme. As discussed previously, the voltage decay on each pulse is due to the losses in the magnetic core and the inability to recharge the energy storage capacitors to the target voltage between pulses.

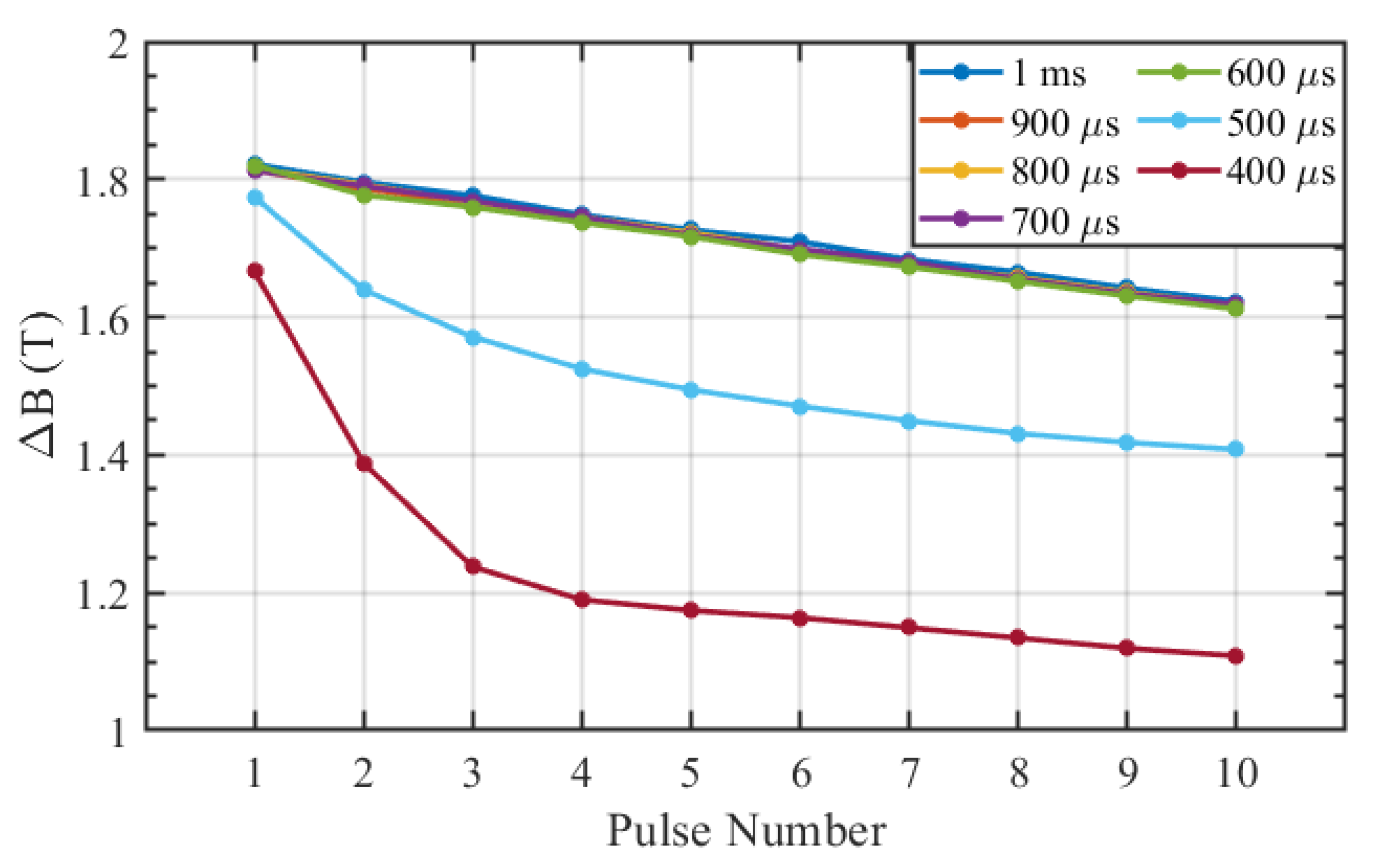

Figure 15 depicts the flux swing of each core of the LTD across the 10 shots in the burst across a range of inter-pulse spacings. The top grouping consisting of the 1 ms - 600

inter-pulse spacings experience some reduction in flux swing as the pulse number increases, associated with the energy loss in the cores. The reduction in flux swing observed in the 500

and 400

inter-pulse spacing tests was significantly more rapid in the initial pulses, indicating saturation of the magnetic cores.

These results demonstrate that, under the previously defined operating conditions, the minimum inter-pulse spacing is between 500 and 600 , corresponding to a maximum operating frequency of just under 2 kHz.