Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Trouble in Paradise – Short Overview of the Neuronal Cell Cultures

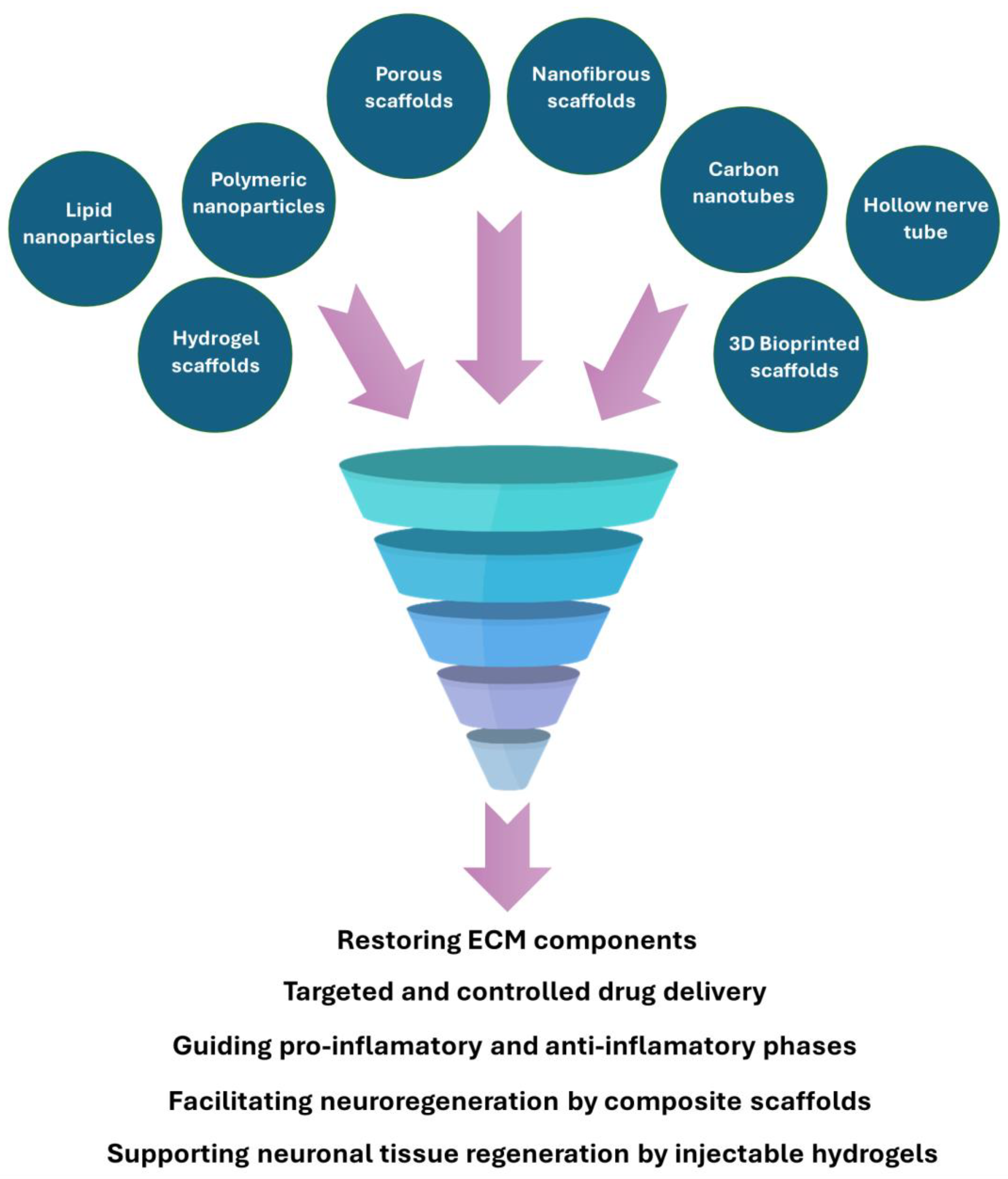

3. Nanomaterials in Nerve Regeneration

3.1. The Influence of Nanomaterial Structure on Its Role in Neuroregeneration

3.2. Multifaceted Approach to Nerve Regeneration Using Nanomaterials

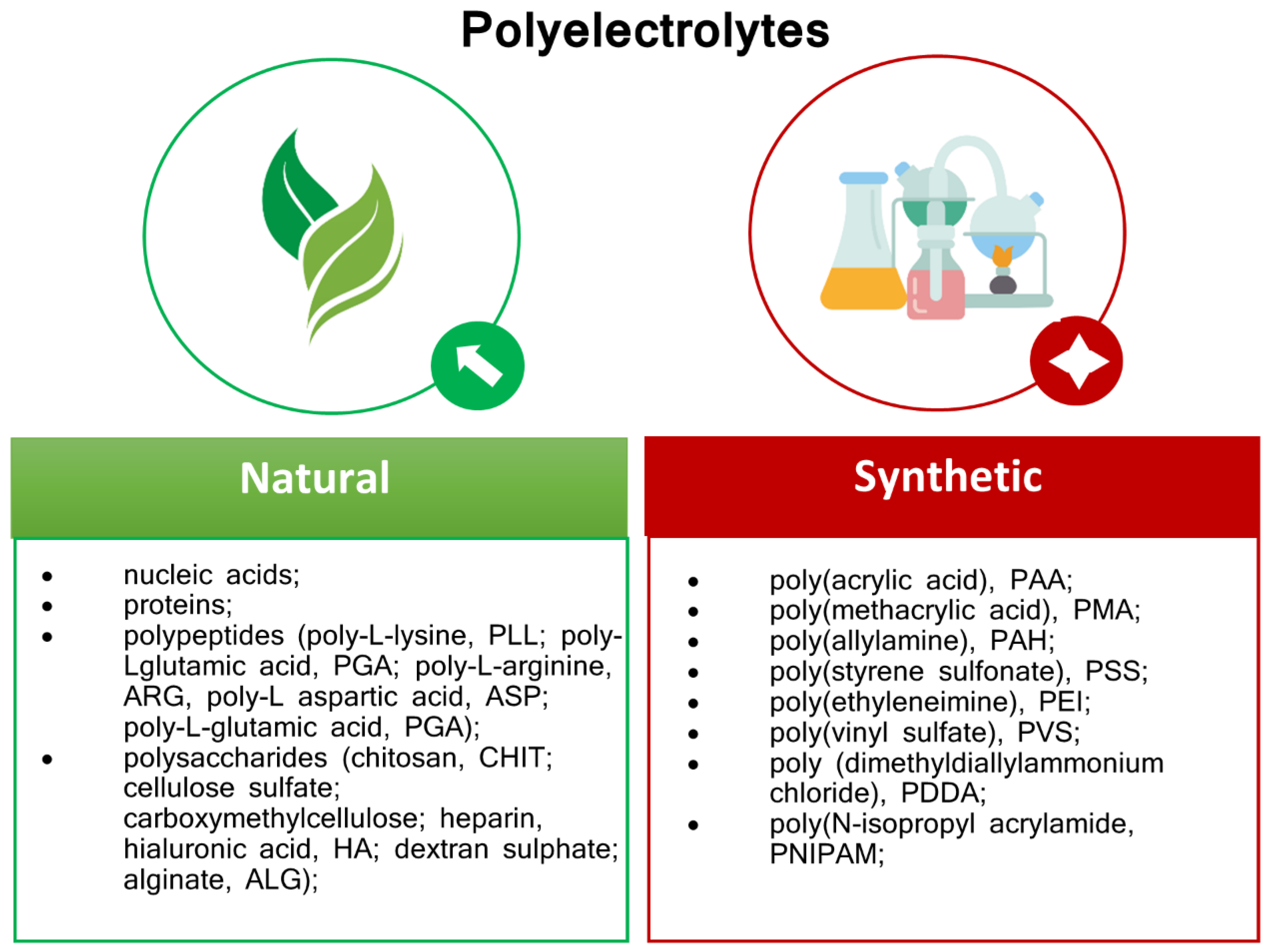

4. Polyelectrolytes Materials

4.1. Mechanism Of Self-Assembly

4.2. Polyelectrolytes for Neural Cell Regeneration in Terms of Mechanical Properties and Potential

4.3. Polyelectrolytes for Interface with Neural Cells

5. PE and PE-Based Nanocomposites Application for Neuronal Cell Immobilization

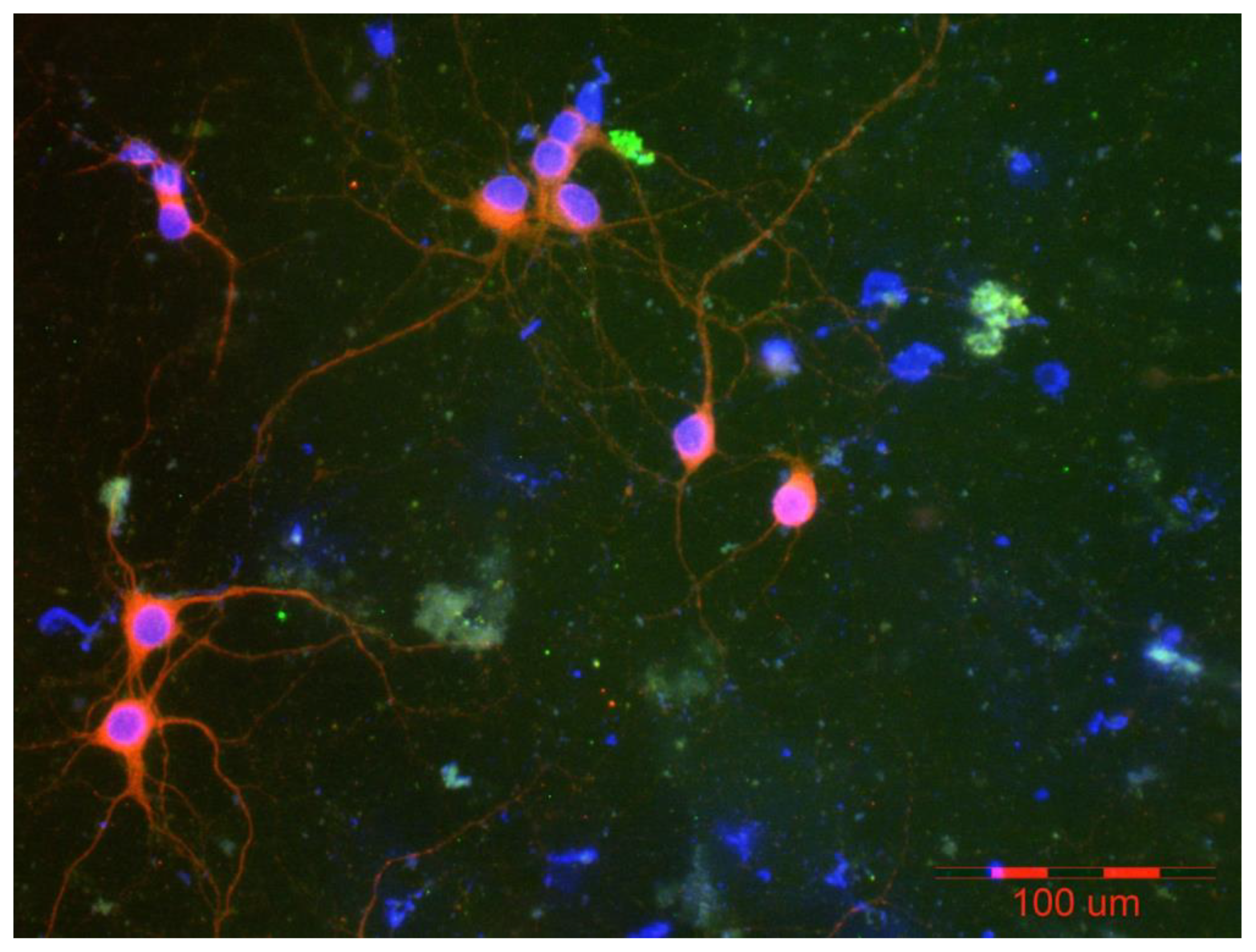

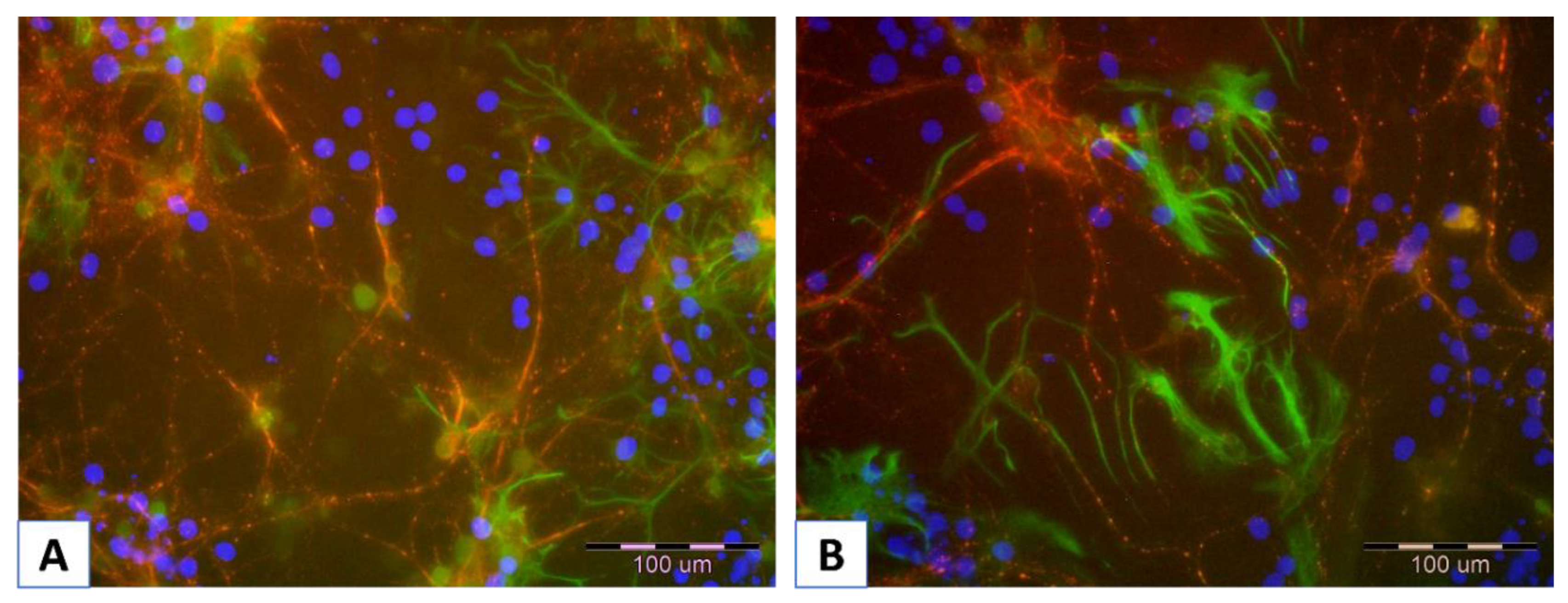

5.1. Visualization of Layer Coating Scaffold-Neuronal Cells Systems

6. Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Molecular and Cellular Basis of Neurodegenerative Diseases | ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780128113042/the-molecular-and-cellular-basis-of-neurodegenerative-diseases?via=ihub= (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Ciurea, A.V.; Mohan, A.G.; Covache-Busuioc, R.A.; Costin, H.P.; Glavan, L.A.; Corlatescu, A.D.; Saceleanu, V.M. Unraveling Molecular and Genetic Insights into Neurodegenerative Diseases: Advances in Understanding Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s Diseases and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J.I.; Borchelt, D.R. Phenotypic diversity in ALS and the role of poly-conformational protein misfolding. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 142, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadhave, D.G.; Sugandhi, V. V.; Jha, S.K.; Nangare, S.N.; Gupta, G.; Singh, S.K.; Dua, K.; Cho, H.; Hansbro, P.M.; Paudel, K.R. Neurodegenerative disorders: Mechanisms of degeneration and therapeutic approaches with their clinical relevance. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 99, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigin, V.L.; Vos, T.; Nichols, E.; Owolabi, M.O.; Carroll, W.M.; Dichgans, M.; Deuschl, G.; Parmar, P.; Brainin, M.; Murray, C. The global burden of neurological disorders: translating evidence into policy. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Schependom, J.; D’haeseleer, M. Advances in Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Pan, H.; Han, L. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders in 204 countries and territories worldwide. J. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 04160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, J.D.; Seeher, K.M.; Schiess, N.; Nichols, E.; Cao, B.; Servili, C.; Cavallera, V.; Cousin, E.; Hagins, H.; Moberg, M.E.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 344–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R.; Saini, A.K.; Taliyan, R.; Chaturvedi, N. Neurodegenerative diseases early detection and monitoring system for point-of-care applications. Microchem. J. 2025, 208, 112280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, L.X.; Ong, S.C.; Tay, L.J.; Ng, T.; Parumasivam, T. Economic Burden of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Value Heal. Reg. Issues 2024, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cao, Z.; Nandi, A.; Counts, N.; Jiao, L.; Prettner, K.; Kuhn, M.; Seligman, B.; Tortorice, D.; Vigo, D.; et al. The global macroeconomic burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: estimates and projections for 152 countries or territories. Lancet Glob. Heal. 2024, 12, e1534–e1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammam, I.A.; Winters, R.; Hong, Z. Advancements in the application of biomaterials in neural tissue engineering: A review. Biomed. Eng. Adv. 2024, 8, 100132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, G.G. Molecular pathology of neurodegenerative diseases: Principles and practice. J. Clin. Pathol. 2019, 72, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, M.N.; Zamboni, F.; Serafin, A.; Escobar, A.; Stepanian, R.; Culebras, M.; Reis, R.L.; Oliveira, J.M. Emerging scaffold- and cellular-based strategies for brain tissue regeneration and imaging. Vitr. Model. 2022 12 2022, 1, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.; Amini, S. General Overview of Neuronal Cell Culture. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2311, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.C.; Wu, Y.C. Facilitating neural stem/progenitor cell niche calibration for neural lineage differentiation by polyelectrolyte multilayer films. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2014, 121, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, M.J.; Gu, K.; Harris, S.N.; Al-Alwan, L.; Gutsin, L.; De Biasio, D.; Jiang, B.; Nakamura, D.S.; Corkery, T.C.; Kennedy, T.E.; et al. Tunable Engineered Extracellular Matrix Materials: Polyelectrolyte Multilayers Promote Improved Neural Cell Growth and Survival. Macromol. Biosci. 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, P.; Parker, T.; Gadegaard, N.; Alexander, M.R. Surface strategies for control of neuronal cell adhesion: A review. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2010, 65, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Solanki, A.; Lee, K.B. Nanotechnology-Based Approaches for Guiding Neural Regeneration. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi Darehbagh, R.; Mahmoodi, M.; Amini, N.; Babahajiani, M.; Allavaisie, A.; Moradi, Y. The effect of nanomaterials on embryonic stem cell neural differentiation: a systematic review. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, K.; Zhang, Z.; Kannan, S. Neuronanotechnology for brain regeneration. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 148, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krsek, A.; Jagodic, A.; Baticic, L. Nanomedicine in Neuroprotection, Neuroregeneration, and Blood–Brain Barrier Modulation: A Narrative Review. Medicina (B. Aires). 2024, 60, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Hong, F.F.; Cao, Z.; Zhao, S.Y.; Chen, L. In Situ Fabrication of Nerve Growth Factor Encapsulated Chitosan Nanoparticles in Oxidized Bacterial Nanocellulose for Rat Sciatic Nerve Regeneration. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 4988–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, P.; Chen, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; He, X.; Huselstein, C.; Ye, Q.; Tong, Z.; Chen, Y. Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor-Transfected Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cells for the Repair of Periphery Nerve Injury. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 563158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Rodrigues, B.; Kanekiyo, T.; Singh, J. ApoE-2 Brain-Targeted Gene Therapy Through Transferrin and Penetratin Tagged Liposomal Nanoparticles. Pharm. Res. 2019, 36, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Layek, B.; Singh, J. Design and Validation of Liposomal ApoE2 Gene Delivery System to Evade Blood-Brain Barrier for Effective Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos Rodrigues, B.; Oue, H.; Banerjee, A.; Kanekiyo, T.; Singh, J. Dual functionalized liposome-mediated gene delivery across triple co-culture blood brain barrier model and specific in vivo neuronal transfection. J Control Release 2018, 286, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakkadwala, S.; dos Santos Rodrigues, B.; Sun, C.; Singh, J. Dual Functionalized Liposomes for Efficient Co-delivery of Anti-cancer Chemotherapeutics for the Treatment of Glioblastoma. J. Control. Release 2019, 307, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, X.; Wen, H.; Lu, W.L.; Du, J.; Guo, J.; Tian, W.; Men, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.J.; Yang, T.Y.; et al. Dual-targeting daunorubicin liposomes improve the therapeutic efficacy of brain glioma in animals. J. Control. Release 2010, 141, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Modgil, A.; Sun, C.; Singh, J. Grafting of cell-penetrating peptide to receptor-targeted liposomes improves their transfection efficiency and transport across blood-brain barrier model. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 101, 2468–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Rodrigues, B.; Banerjee, A.; Kanekiyo, T.; Singh, J. Functionalized Liposomal Nanoparticles for Efficient Gene Delivery System to Neuronal Cell Transfection. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 566, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, F.; Guzman, L. Dendrimer nanocarriers drug action: perspective for neuronal pharmacology. Neural Regen. Res. 2015, 10, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Carrión, M.D.; Posadas, I. Dendrimers in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Process. 2023, Vol. 11, Page 319 2023, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhan, M.; Sun, H.; He, L.; Zou, Y.; Huang, T.; Karpus, A.; Majoral, J.P.; Mignani, S.; Shen, M.; et al. Phosphorus Dendrimers Co-deliver Fibronectin and Edaravone for Combined Ischemic Stroke Treatment via Cooperative Modulation of Microglia/Neurons and Vascular Regeneration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar, A.; Carvalho, M.R.; Maia, F.R.; Reis, R.L.; Silva, T.H.; Oliveira, J.M. Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor-Loaded CMCht/PAMAM Dendrimer Nanoparticles for Peripheral Nerve Repair. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Wu, T.; Qiu, J.; Xia, Y. Spatiotemporally Controlling the Release of Biological Effectors Enhances Their Effects on Cell Migration and Neurite Outgrowth. Small Methods 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donsante, A.; Xue, J.; Poth, K.M.; Hardcastle, N.S.; Diniz, B.; O’Connor, D.M.; Xia, Y.; Boulis, N.M. Controlling the Release of Neurotrophin-3 and Chondroitinase ABC Enhances the Efficacy of Nerve Guidance Conduits. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Wang, T.; Hu, S.; Luan, J.; Tian, F.; Ma, G.; Xue, J. Engineering of electrospun nanofiber scaffolds for repairing brain injury. Eng. Regen. 2023, 4, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiguera, S.; Del Gaudio, C.; Lucatelli, E.; Kuevda, E.; Boieri, M.; Mazzanti, B.; Bianco, A.; Macchiarini, P. Electrospun gelatin scaffolds incorporating rat decellularized brain extracellular matrix for neural tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 1205–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, B.; Chandrasekaran, J.; Cherian, K.M.; Fakoya, A.O.J. Biodegradable nanofiber coated human umbilical cord as nerve scaffold for sciatic nerve regeneration in albino Wistar rats. Folia Morphol. (Warsz). 2024, 83, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; MacEwan, M.R.; Schwartz, A.G.; Xia, Y. Electrospun nanofibers for neural tissue engineering. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Ou, X.; Cheng, D. How Advancing is Peripheral Nerve Regeneration Using Nanofiber Scaffolds? A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 6763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghati, T.; Seifalian, A.M. Nanotechnology and bio-functionalisation for peripheral nerve regeneration. Neural Regen. Res. 2015, 10, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alla, K.; Yuri, C.; Anatoliy, L.; Volodymyr, L.; Yuriy, S.; Alla, K.; Yuri, C.; Anatoliy, L.; Volodymyr, L.; Yuriy, S. Interface Nerve Tissue-Silicon Nanowire for Regeneration of Injured Nerve and Creation of Bio-Electronic Device. Neurons - Dendrites Axons 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichodievskiy, V.; Vysotskaya, N.; Ryabchikov, O.; Korsak, A.; Chaikovsky, Y.; Klimovskaya, A.; Pedchenko, Y.; Lutsyshyn, I.; Stadnyk, O. Application of Oxidized Silicon Nanowires for Nerve Fibers Regeneration. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 854, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidu, R.; Rahman, M.; Mahmoudi, M.; Enachescu, M.; Poteca, T.D.; Opris, I. Nanostructures: a platform for brain repair and augmentation. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechara, S.; Wadman, L.; Popat, K.C. Electroconductive polymeric nanowire templates facilitates in vitro C17.2 neural stem cell line adhesion, proliferation and differentiation. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 2892–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.; Kwon, E.J.; Kang, J.; Skalak, M.; Anglin, E.J.; Mann, A.P.; Ruoslahti, E.; Bhatia, S.N.; Sailor, M.J. Porous silicon–graphene oxide core–shell nanoparticles for targeted delivery of siRNA to the injured brain. Nanoscale horizons 2016, 1, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convertino, D.; Trincavelli, M.L.; Giacomelli, C.; Marchetti, L.; Coletti, C. Graphene-based nanomaterials for peripheral nerve regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1306184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ławkowska, K.; Pokrywczyńska, M.; Koper, K.; Kluth, L.A.; Drewa, T.; Adamowicz, J. Application of Graphene in Tissue Engineering of the Nervous System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, Vol. 23, Page 33 2021, 23, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, T.; Gurcan, C.; Taheri, H.; Yilmazer, A. Graphene based materials in neural tissue regeneration. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1107, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Y.; Yan, Z.; Yang, H.; Xu, X.; Yuan, W.E.; Qian, Y. Graphene Family Nanomaterials for Stem Cell Neurogenic Differentiation and Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 4741–4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Wang, X.; Song, J.; Chen, W.; Chen, S.; Jin, Y.; Ouyang, Y.; Yuan, W.E.; Fan, C. Preclinical assessment on neuronal regeneration in the injury-related microenvironment of graphene-based scaffolds. npj Regen. Med. 2021, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleemardani, M.; Zare, P.; Seifalian, A.; Bagher, Z.; Seifalian, A.M. Graphene-Based Materials Prove to Be a Promising Candidate for Nerve Regeneration Following Peripheral Nerve Injury. Biomedicines 2021, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Lin, Y.; Li, C.; Lei, F.; Luo, H.; Jing, P.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, Z.; et al. Zein-Based Triple-Drug Nanoparticles to Promote Anti-Inflammatory Responses for Nerve Regeneration after Spinal Cord Injury. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 2304261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C. Study on antibacterial activity and repair of peripheral nervous system injury by Zno nanocomposites. Mater. Lett. 2023, 340, 134180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, M.; Haoran, J.; Xing, B.; Wang, B.; Heng, A.; Wen, Y.; Peixun, Z. Design of AgNPs Loaded γ-PGA Chitosan Conduits with Superior Antibacterial Activity and Nerve Repair Properties. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 13 1561330. [CrossRef]

- Demirdöğen, B.C. Theranostic potential of graphene quantum dots for multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.; Das, S.S.; Dey, A.; Chakraborty, A.; Bhattacharyya, C.; Kandimalla, R.; Mukherjee, B.; Gopalakrishnan, A.V.; Singh, S.K.; Kant, S.; et al. Quantum dots: The cutting-edge nanotheranostics in brain cancer management. J. Control. Release 2022, 350, 698–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Mahajan, S.; Roy, I.; Yong, K.T. Theranostic quantum dots for crossing blood-brain barrier in vitro and providing therapy of HIV-associated encephalopathy. Front. Pharmacol. 2013, 4 NOV, 66969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, X.; Niu, Y.; He, K.; Tang, M. Application of quantum dots in brain diseases and their neurotoxic mechanism. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 3733–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalva, M.D.; Agarwal, V.; Ulanova, M.; Sachdev, P.S.; Braidy, N. Quantum Dots as A Theranostic Approach in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 1595–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Wu, J.; Sun, J. Four types of inorganic nanoparticles stimulate the inflammatory reaction in brain microglia and damage neurons in vitro. Toxicol. Lett. 2012, 214, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, S.; Islam Aqib, A.; Muneer, A.; Fatima, M.; Atta, K.; Kausar, T.; Zaheer, C.N.F.; Ahmad, I.; Saeed, M.; Shafique, A. Insights into nanoparticles-induced neurotoxicity and cope up strategies. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1127460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajka, M.; Sawicki, K.; Sikorska, K.; Popek, S.; Kruszewski, M.; Kapka-Skrzypczak, L. Toxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in central nervous system. Toxicol. Vitr. 2015, 29, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Xiong, L.; Zhou, G.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Yuan, F.; Lu, S.; Wan, Z.; et al. Silver nanoparticles crossing through and distribution in the blood-brain barrier in vitro. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2010, 10, 6313–6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Xiong, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Yuan, F.; Xi, T. Distribution, translocation and accumulation of silver nanoparticles in rats. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2009, 9, 4924–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.L.; Gao, J.Q. Potential neurotoxicity of nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2010, 394, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeschner, K.; Hadrup, N.; Qvortrup, K.; Larsen, A.; Gao, X.; Vogel, U.; Mortensen, A.; Lam, H.R.; Larsen, E.H. Distribution of silver in rats following 28 days of repeated oral exposure to silver nanoparticles or silver acetate. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2011, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.N.; Poon, W.; Tavares, A.J.; McGilvray, I.D.; Chan, W.C.W. Nanoparticle–liver interactions: Cellular uptake and hepatobiliary elimination. J. Control. Release 2016, 240, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltysova, A.; Ludwig, N.; Diener, C.; Sramkova, M.; Kozics, K.; Jakic, K.; Balintova, L.; Bastus, N.G.; Moriones, O.H.; Liskova, A.; et al. Gold and titania nanoparticles accumulated in the body induce late toxic effects and alterations in transcriptional and miRNA landscape. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 1296–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Mahady Dip, T.; Padhye, R.; Houshyar, S. Review on electrically conductive smart nerve guide conduit for peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2023, 111, 1916–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Lin, H.; Yan, Z.; Shi, J.; Fan, C. Functional nanomaterials in peripheral nerve regeneration: Scaffold design, chemical principles and microenvironmental remodeling. Mater. Today 2021, 51, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fang, J.; Weng, Z.; Nan, L.; Chen, Y.; Shan, J.; Chen, F.; Liu, J. Advanced development of conductive biomaterials for enhanced peripheral nerve regeneration: a review. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 12997–13009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.; Gao, X.; Gu, G.; Liu, Z.; Hu, Q.; Tu, Y.; Song, Q.; Yao, L.; Pang, Z.; Jiang, X.; et al. Penetratin-functionalized PEG–PLA nanoparticles for brain drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 436, 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Ye, H.; Wu, D. Recent advances on polymeric hydrogels as wound dressings. APL Bioeng. 2021, 5, 11504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Fu, Q.; Song, L.; Liu, L.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Advances in Peripheral Nerve Injury Repair with the Application of Nanomaterials. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 7619884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Farahani, M.K.; Salehi, M.; Atashi, A.; Alizadeh, M.; Kheradmandi, R.; Molzemi, S. Exploring the Physicochemical, Electroactive, and Biodelivery Properties of Metal Nanoparticles on Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 106–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.; Huang, Y.; Wei, J.; Lai, C.; Chen, Y.; Nan, K.; Wu, W. Implantation of biomimetic polydopamine nanocomposite scaffold promotes optic nerve regeneration through modulating inhibitory microenvironment. J. Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.S.; Park, J.M.; Lee, S.; Hong, S.J.; Park, J.S.; Park, K.H. Fabrication of Nanocomposites Complexed with Gold Nanoparticles on Polyaniline and Application to Their Nerve Regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 30750–30760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacko, C.S.; Singh, I.; Wall, M.A.; Garcia, A.R.; Porvasnik, S.L.; Rinaldi, C.; Schmidt, C.E. Magnetic particle templating of hydrogels: Engineering naturally derived hydrogel scaffolds with 3D aligned microarchitecture for nerve repair. J. Neural Eng. 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés, M.; Cáceres, L.; Chiappetta, D.; Magnani, N.; Evelson, P. Current understanding of nanoparticle toxicity mechanisms and interactions with biological systems. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 14328–14344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbuna, C.; Parmar, V.K.; Jeevanandam, J.; Ezzat, S.M.; Patrick-Iwuanyanwu, K.C.; Adetunji, C.O.; Khan, J.; Onyeike, E.N.; Uche, C.Z.; Akram, M.; et al. Toxicity of Nanoparticles in Biomedical Application: Nanotoxicology. J. Toxicol. 2021, 2021, 9954443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fard, J.K.; Jafari, S.; Eghbal, M.A. A Review of Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Toxicity of Nanoparticles. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2015, 5, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, A.B.; Clemons, T.D. Bottom-Up versus Top-Down Strategies for Morphology Control in Polymer-Based Biomedical Materials. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 2022, 2, 2100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, N.; Khan, A.M.; Shujait, S.; Chaudhary, K.; Ikram, M.; Imran, M.; Haider, J.; Khan, M.; Khan, Q.; Maqbool, M. Synthesis of nanomaterials using various top-down and bottom-up approaches, influencing factors, advantages, and disadvantages: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 300, 102597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, M.; Sawadaishi, T. Bottom-up strategy of materials fabrication: a new trend in nanotechnology of soft materials. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2001, 6, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municoy, S.; Álvarez Echazú, M.I.; Antezana, P.E.; Galdopórpora, J.M.; Olivetti, C.; Mebert, A.M.; Foglia, M.L.; Tuttolomondo, M. V.; Alvarez, G.S.; Hardy, J.G.; et al. Stimuli-Responsive Materials for Tissue Engineering and Drug Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, Vol. 21, Page 4724 2020, 21, 4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redolfi Riva, E.; Özkan, M.; Stellacci, F.; Micera, S. Combining external physical stimuli and nanostructured materials for upregulating pro-regenerative cellular pathways in peripheral nerve repair. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1491260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; des Rieux, A.; Malfanti, A. Stimuli-Responsive Nanomedicines for the Treatment of Non-cancer Related Inflammatory Diseases. ACS Nano 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Forge, D.; Port, M.; Roch, A.; Robic, C.; Vander Elst, L.; Muller, R.N. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis, stabilization, vectorization, physicochemical characterizations and biological applications. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2064–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.; Bui, T.A.; Yang, X.; Aksoy, Y.; Goldys, E.M.; Deng, W. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles for Drug/Gene Delivery: An Overview of the Production Techniques and Difficulties Encountered in Their Industrial Development. ACS Mater. Au 2023, 3, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, I.; Alabdallah, N.M.; jomaa, A. Al; kamoun, M. Gold nanoparticles: Synthesis properties and applications. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 2021, 33, 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asem, H.; Zheng, W.; Nilsson, F.; Zhang, Y.; Hedenqvist, M.S.; Hassan, M.; Malmström, E. Functional Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery by Surface Engineering of Polymeric Nanoparticle Post-Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiner, E.G.; van Ravensteijn, B.G.P. Polymerization-induced self-assembly for drug delivery: A critical appraisal. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 61, 3186–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, L.T.; Singh, N.; Gorain, B.; Choudhury, H.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Kesharwani, P.; Shukla, R. Recent Advances in Self-Assembled Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, T.G.; Gurnani, P.; Rho, J.Y. Characterisation of polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 7738–7752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, N.; Kammakakam, I.; Falath, W.; Kammakakam, I. Nanomaterials: a review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 1821–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Ou, X.; Cheng, D. Nanoparticle-Facilitated Therapy: Advancing Tools in Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wan, L.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, K.; Wu, P.; Li, C.; Huang, C.; Liu, X.; Xue, W.; Sun, G.; et al. Curcumin/pEGCG-encapsulated nanoparticles enhance spinal cord injury recovery by regulating CD74 to alleviate oxidative stress and inflammation. J. Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mao, Y.; Huang, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.; An, J.; Jin, Y.; Guan, J.; Wu, L.; Zhou, P. Selenium nanoparticles derived from Proteus mirabilis YC801 alleviate oxidative stress and inflammatory response to promote nerve repair in rats with spinal cord injury. Regen. Biomater. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Qing, X.; Peng, L.; Zhang, D.; Dai, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X. Mannose-coated nanozyme for relief from chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathic pain. iScience 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Han, Z.; Wang, T.; Ma, C.; Li, H.; Lei, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pei, Z.; Liu, Z.; et al. Cerium oxide nanoparticles with antioxidative neurorestoration for ischemic stroke. Biomaterials 2022, 291, 121904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, B.; Mao, Y.; Al Mamun, A.; Wu, M.; Qu, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Pan, J.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Zein nanoparticles loaded with chloroquine improve functional recovery and attenuate neuroinflammation after spinal cord injury. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 137882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Xu, M.; Feng, L.; Zhong, W.; Zhang, L.; Du, R.; Sun, J.; Wang, C.; Du, J. Nanozyme Hydrogels Promote Nerve Regeneration in Spinal Cord Injury by Reducing Oxidative Stress. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Tu, M.; Gao, W.; Cai, X.; Song, F.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Jin, C.; Shi, J.; et al. Hollow Prussian Blue Nanozymes Drive Neuroprotection against Ischemic Stroke via Attenuating Oxidative Stress, Counteracting Inflammation, and Suppressing Cell Apoptosis. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 2812–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Guo, J.; Cai, J.; Chen, X.; Wei, H.; Qi, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; et al. Conductive Nerve Guidance Conduits Based on Morpho Butterfly Wings for Peripheral Nerve Repair. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 1868–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Tang, A.; Xiong, C.; Zhang, G.; Huang, L.; Xu, F. Oriented Graphene Oxide Scaffold Promotes Nerve Regeneration in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 2573–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanwright, P.J.; Qiu, C.; Rath, J.; Zhou, Y.; von Guionneau, N.; Sarhane, K.A.; Harris, T.G.W.; Howard, G.P.; Malapati, H.; Lan, M.J.; et al. Sustained IGF-1 delivery ameliorates effects of chronic denervation and improves functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury and repair. Biomaterials 2022, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.D.F.; Gonçalves, N.P.; Gomes, C.P.; Saraiva, M.J.; Pêgo, A.P. BDNF gene delivery mediated by neuron-targeted nanoparticles is neuroprotective in peripheral nerve injury. Biomaterials 2017, 121, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Kumar, S.; Jain, S.; Nag, T.C.; Mathur, R. Neuroregenerative Effects of Electromagnetic Field and Magnetic Nanoparticles on Spinal Cord Injury in Rats. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 18, 6756–6764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastefanaki, F.; Jakovcevski, I.; Poulia, N.; Djogo, N.; Schulz, F.; Martinovic, T.; Ciric, D.; Loers, G.; Vossmeyer, T.; Weller, H.; et al. Intraspinal Delivery of Polyethylene Glycol-coated Gold Nanoparticles Promotes Functional Recovery After Spinal Cord Injury. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittchen, S.; Boyd, A.; Burns, A.; Park, J.; Fahmy, T.M.; Metcalfe, S.; Williams, A. Myelin repair invivo is increased by targeting oligodendrocyte precursor cells with nanoparticles encapsulating leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF). Biomaterials 2015, 56, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.P.; Zhang, J.Z.; Titus, H.E.; Karl, M.; Merzliakov, M.; Dorfman, A.R.; Karlik, S.; Stewart, M.G.; Watt, R.K.; Facer, B.D.; et al. Nanocatalytic activity of clean-surfaced, faceted nanocrystalline gold enhances remyelination in animal models of multiple sclerosis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Wang, Y.; Lin, F.; Liu, Y.; Gu, R.; Liu, W.; Xiao, C. Selenium-doped carbon quantum dots efficiently ameliorate secondary spinal cord injury via scavenging reactive oxygen species. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 10113–10125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antman-Passig, M.; Giron, J.; Karni, M.; Motiei, M.; Schori, H.; Shefi, O. Magnetic Assembly of a Multifunctional Guidance Conduit for Peripheral Nerve Repair. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2010837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoukian, O.S.; Rudraiah, S.; Arul, M.R.; Bartley, J.M.; Baker, J.T.; Yu, X.; Kumbar, S.G. Biopolymer-nanotube nerve guidance conduit drug delivery for peripheral nerve regeneration: In vivo structural and functional assessment. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 2881–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval-Castellanos, A.M.; Claeyssens, F.; Haycock, J.W. Bioactive 3D Scaffolds for the Delivery of NGF and BDNF to Improve Nerve Regeneration. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 734683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis, T.M.; Vidal, G.; Jose, R.R.; Vigneron, P.; Bresson, D.; Fitzpatrick, V.; Marin, F.; Kaplan, D.L.; Egles, C. Complementary Effects of Two Growth Factors in Multifunctionalized Silk Nanofibers for Nerve Reconstruction. PLoS One 2014, 9, e109770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Lv, Y. Dual-delivery of VEGF and NGF by emulsion electrospun nanofibrous scaffold for peripheral nerve regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 82, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ge, X.; Qian, Y.; Tang, H.; Song, J.; Qu, X.; Yue, B.; Yuan, W.E. Electrospinning Multilayered Scaffolds Loaded with Melatonin and Fe3O4 Magnetic Nanoparticles for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, S.; Zhou, T.; Wu, K.; Qiao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xin, N.; Liu, X.; Wei, D.; Sun, J.; et al. Antioxidative and Conductive Nanoparticles-Embedded Cell Niche for Neural Differentiation and Spinal Cord Injury Repair. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 52346–52361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Lu, D.; Wu, J.; Liang, F.; Wang, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, L.; et al. Nanoparticles for the treatment of spinal cord injury. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 20, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voiţă-Mekereş, F.; Mekeres, G.M.; Voiță, I.B.; Galea-Holhoș, L.B.; Manole, F. A Review of the Protective Effects of Nanoparticles in the Treatment of Nervous System Injuries. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Allied Sci. 2023, 12, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Notterpek, L. Promoting peripheral myelin repair. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 283, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigil, P.; Orellana, R.F.; Cortés, M.E.; Molina, C.T.; Switzer, B.E.; Klaus, H. Endocrine Modulation of the Adolescent Brain: A Review. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2011, 24, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

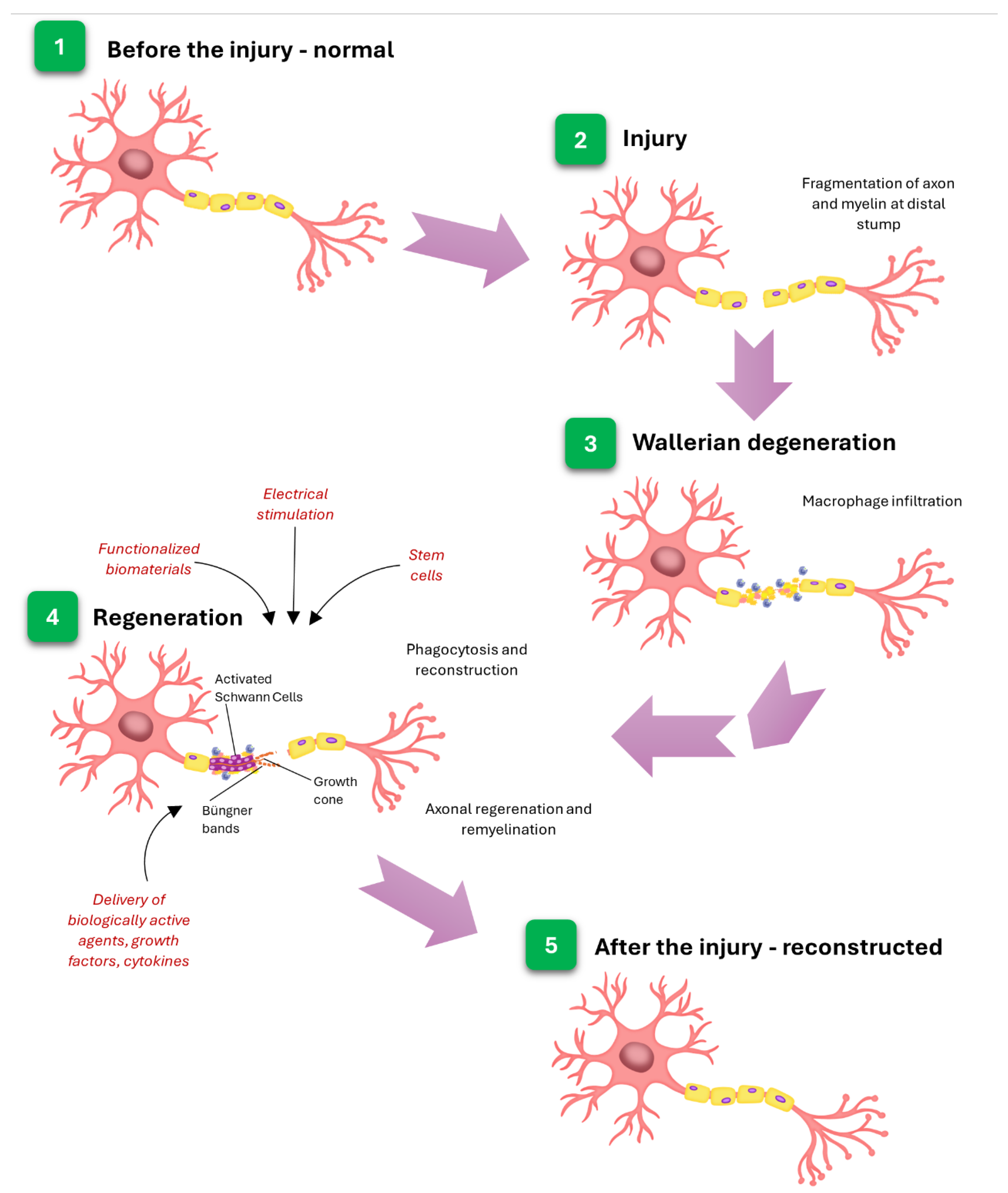

- Arthur-Farraj, P.J.; Latouche, M.; Wilton, D.K.; Quintes, S.; Chabrol, E.; Banerjee, A.; Woodhoo, A.; Jenkins, B.; Rahman, M.; Turmaine, M.; et al. c-Jun Reprograms Schwann Cells of Injured Nerves to Generate a Repair Cell Essential for Regeneration. Neuron 2012, 75, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheib, J.; Höke, A. Advances in peripheral nerve regeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 9, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.W.; Thompson, W.J. Biology and pathology of nonmyelinating schwann cells. Glia 2008, 56, 1518–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattin, A.L.; Burden, J.J.; Van Emmenis, L.; MacKenzie, F.E.; Hoving, J.J.A.; Garcia Calavia, N.; Guo, Y.; McLaughlin, M.; Rosenberg, L.H.; Quereda, V.; et al. Macrophage-Induced Blood Vessels Guide Schwann Cell-Mediated Regeneration of Peripheral Nerves. Cell 2015, 162, 1127–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, C.F.; Bunge, M.B.; Bunge, R.P.; Wood, P.M. Differentiation of axon-related Schwann cells in vitro. I. Ascorbic acid regulates basal lamina assembly and myelin formation. J. Cell Biol. 1987, 105, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, Y.; Taniguchi, J.B.; Homma, H.; Tamura, T.; Fujita, K.; Inotsume, M.; Tagawa, K.; Misawa, K.; Matsumoto, N.; Nakagawa, M.; et al. AAV-mediated editing of PMP22 rescues Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A features in patient-derived iPS Schwann cells. Commun. Med. 2023 31 2023, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.; Boecker, A.; Tank, J.; Altinova, H.; Deumens, R.; Dabhi, C.; Tolba, R.; Weis, J.; Brook, G.A.; Pallua, N.; et al. Efficient bridging of 20 mm rat sciatic nerve lesions with a longitudinally micro-structured collagen scaffold. Biomaterials 2016, 75, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, L.M.; Sakiyama-Elbert, S.E. Engineering peripheral nerve repair. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013, 24, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajimirzaei, P.; Tabatabaei, F.S.A.; Nasibi-Sis, H.; Razavian, R.S.; Nasirinezhad, F. Schwann cell transplantation for remyelination, regeneration, tissue sparing, and functional recovery in spinal cord injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of animal studies. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 384, 115062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, Z.; Lin, Z.; Song, P.; Quan, D.; Bai, Y. Biomaterial-Based Schwann Cell Transplantation and Schwann Cell-Derived Biomaterials for Nerve Regeneration. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 926222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.D.L.; Ganguly, D.; Zuidema, J.M.; Cardinal, T.J.; Ziemba, A.M.; Kearns, K.R.; McCarthy, S.M.; Thompson, D.M.; Ramanath, G.; Borca-Tasciuc, D.A.; et al. Injectable, Magnetically Orienting Electrospun Fiber Conduits for Neuron Guidance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 11, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, J.; Yang, L.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y. Nanoparticles carrying neurotrophin-3-modified Schwann cells promote repair of sciatic nerve defects. Neural Regen. Res. 2013, 8, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Dumitru, A.V.; Eva, L.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.A.; Ciurea, A.V. Nanoparticle Strategies for Treating CNS Disorders: A Comprehensive Review of Drug Delivery and Theranostic Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, Vol. 25, Page 13302 2024, 25, 13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Dung Nguyen, T.T.; Vo, T.K.; Tran, N.M.A.; Nguyen, M.K.; Van Vo, T.; Van Vo, G. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery for central nervous system disorders. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, J. Drug delivery to the central nervous system by polymeric nanoparticles: What do we know? Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014, 71, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

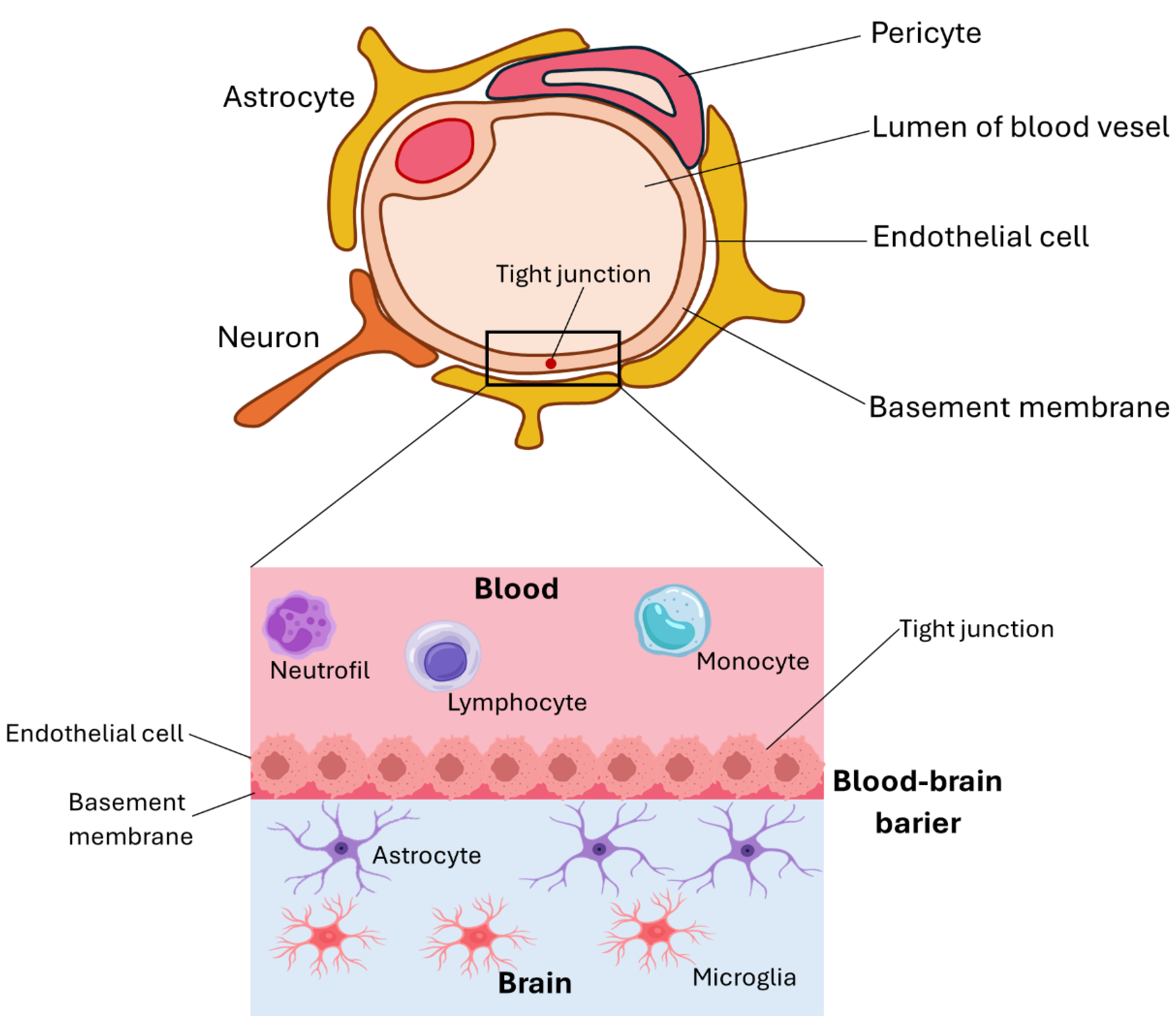

- Wu, D.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Han, F.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y. The blood–brain barrier: structure, regulation, and drug delivery. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleanu, D.M.; Chircov, C.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Volceanov, A.; Teleanu, R.I. Blood-Brain Delivery Methods Using Nanotechnology. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillama Barroso, G.; Narayan, M.; Alvarado, M.; Armendariz, I.; Bernal, J.; Carabaza, X.; Chavez, S.; Cruz, P.; Escalante, V.; Estorga, S.; et al. Nanocarriers as Potential Drug Delivery Candidates for Overcoming the Blood-Brain Barrier: Challenges and Possibilities. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 12583–12595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersh, A.M.; Alomari, S.; Tyler, B.M. Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier: Advances in Nanoparticle Technology for Drug Delivery in Neuro-Oncology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.R.; Hernandez, Y.; Miyasaki, K.F.; Kwon, E.J. Engineered nanomaterials that exploit blood-brain barrier dysfunction for delivery to the brain. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 197, 114820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zha, S.; Liu, H.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Wong, K.L.; All, A.H. Functionalized Nanomaterials Capable of Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 1820–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat Razavi, Z.; Sina Alizadeh, S.; Sadat Razavi, F.; Souri, M.; Soltani, M. Advancing neurological disorders therapies: Organic nanoparticles as a key to blood-brain barrier penetration. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 670, 125186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Yang, J.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Kalvakolanu, D. V.; Cong, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Utilization of nanotechnology to surmount the blood-brain barrier in disorders of the central nervous system. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 31, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xue, Y.; Markovic, T.; Li, H.; Wang, S.; Zhong, Y.; Du, S.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, X.; Yu, Y.; et al. Blood–brain-barrier-crossing lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery to the central nervous system. Nat. Mater. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Liu, M.; Lu, J.; Chu, B.; Yang, Y.; Song, B.; Wang, H.; He, Y. Bacteria loaded with glucose polymer and photosensitive ICG silicon-nanoparticles for glioblastoma photothermal immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2022 131 2022, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagri, S.; Rice, O.; Chen, Y. Nanomedicine strategies for central nervous system (CNS) diseases. Front. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 2, 1215384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Tan, C.; Ge, X.; Qin, Z.; Xiong, H. Recent advances in stimuli-responsive controlled release systems for neuromodulation. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 5769–5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.J.; Lan, Y.H.; Chuang, C.C.; Lu, W.T.; Chan, L.Y.; Hsu, P.W.; Chen, J.P. Injectable Thermo-Sensitive Chitosan Hydrogel Containing CPT-11-Loaded EGFR-Targeted Graphene Oxide and SLP2 shRNA for Localized Drug/Gene Delivery in Glioblastoma Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, Vol. 21, Page 7111 2020, 21, 7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, C.; Bi, R.; Qiu, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, B. Cell-Membrane-Coated Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery to the Brain for the Treatment of Neurological Diseases. Pharm. 2023, Vol. 15, Page 621 2023, 15, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, R.G.R.; Coutinho, A.J.; Pinheiro, M.; Neves, A.R. Nanoparticles for Targeted Brain Drug Delivery: What Do We Know? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, Vol. 22, Page 11654 2021, 22, 11654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yang, R.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Wan, L.; He, J. Nanocarrier-based targeted drug delivery for Alzheimer’s disease: addressing neuroinflammation and enhancing clinical translation. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1591438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Cui, N.; Liao, Y.; Guo, C.; Li, L.; Yin, Y.; Wen, A.; Wang, J.; Ye, W.; Ding, Y. Astrocytes and microglia-targeted Danshensu liposomes enhance the therapeutic effects on cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Control. Release 2023, 364, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilella, A.; Tosi, G.; Grabrucker, A.M.; Ruozi, B.; Belletti, D.; Vandelli, M.A.; Boeckers, T.M.; Forni, F.; Zoli, M. Insight on the fate of CNS-targeted nanoparticles. Part I: Rab5-dependent cell-specific uptake and distribution. J. Control. Release 2014, 174, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Peng, T.; Wu, S.Y.; Zhao, L.; Peng, T.; Wu, S.Y. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Application in Toxicity Therapeutics of CNS Disorders Indicated by Molecular MRI. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Ramírez, E.; Montes, M.; Urrutia, R.A.; Reginensi, D.; Segura González, E.A.; Estrada-Petrocelli, L.; Gutierrez-Vega, A.; Appaji, A.; Molino, J. Metallic Nanoparticles Applications in Neurological Disorders: A Review. Int. J. Biomater. 2025, 2025, 4557622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Adhikary, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Goswami, S.; Roy, D.; Dutta, S.; Ganguly, A.; Nanda, S.; Rajak, P. Iron oxide nanoparticles: a narrative review of in-depth analysis from neuroprotection to neurodegeneration. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2024, 3, 635–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, R.; Fu, C.; Forgham, H.; Javed, I.; Huang, X.; Zhu, J.; Whittaker, A.K.; Davis, T.P. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for brain imaging and drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 197, 114822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.; Ryu, J.; Vu, H.D.; Kim, D.; Youn, Y.J.; Park, M.H.; Huynh, P.T.; Hwang, G. Bin; Youn, S.W.; Jeong, Y.H. Transferrin-Conjugated Melittin-Loaded L-Arginine-Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Mitigating Beta-Amyloid Pathology of the 5XFAD Mouse Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Vemireddy, V.; Cai, Q.; Xiong, H.; Kang, P.; Li, X.; Giannotta, M.; Hayenga, H.N.; Pan, E.; Sirsi, S.R.; et al. Reversibly Modulating the Blood–Brain Barrier by Laser Stimulation of Molecular-Targeted Nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 9805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Pan, M.; Zhang, W.; Lin, H.; Wu, S.; Lu, C.; Tang, S.; Liu, D.; Cai, J. Poly(α-l-lysine)-based nanomaterials for versatile biomedical applications: Current advances and perspectives. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 6, 1878–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Song, T.; Tang, S.; Wang, N.; Du, J. Preparation and Antibacterial Mechanism Insight of Polypeptide-Based Micelles with Excellent Antibacterial Activities. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 3922–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, O.S.; Olafson, K.N.; Pillai, P.S.; Mitchell, M.J.; Langer, R. Advances in Biomaterials for Drug Delivery. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, A.V.; Khorsand, B.; Geary, S.M.; Salem, A.K. 3D Printing of Scaffolds for Tissue Regeneration Applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2015, 4, 1742–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Zheng, M.; Tao, W.; Chung, R.; Jin, D.; Ghaffari, D.; Farokhzad, O.C. Challenges in DNA Delivery and Recent Advances in Multifunctional Polymeric DNA Delivery Systems. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 2231–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshanfar, S.; Mbeleck, R.; Xu, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, W.; Xing, M. 3D bioprinting for biomedical devices and tissue engineering: A review of recent trends and advances. Bioact. Mater. 2018, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudalla, G.A.; Murphy, W.L. Biomaterials that regulate growth factor activity via bioinspired interactions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 1754–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Neu, B.; Venkatraman, S.S. Surface functionalization of nanoparticles to control cell interactions and drug release. Small 2012, 8, 2585–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Kumar, D.; Swarnakar, N.K.; Thanki, K. Polyelectrolyte stabilized multilayered liposomes for oral delivery of paclitaxel. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6758–6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iler, R.K. Multilayers of colloidal particles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1966, 21, 569–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, M.; Kamino, A.; Okamura, J.; Shinkai, S. Noncovalent Self-Assembly of Carbon Nanotubes for Construction of “Cages. ” Nano Lett. 2002, 2, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Sano, M. Van der Waals layer-by-layer construction of a carbon nanotube 2D network. Langmuir 2005, 21, 11490–11494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.; Hammond, P. The role of secondary interactions in selective electrostatic multilayer deposition. Langmuir 2000, 16, 10206–10214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Bai, S.; Cui, S.; Qiu, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X. Hydrogen-bonding-directed layer-by-layer multilayer assembly: Reconformation yielding microporous films. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 9451–9458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharlampieva, E.; Kozlovskaya, V.; Tyutina, J.; Sukhishvili, S.A. Hydrogen-bonded multilayers of thermoresponsive polymers. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 10523–10531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teramura, Y.; Iwata, H. Cell surface modification with polymers for biomedical studies. Soft Matter 2010, 6, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, N.A. Layer-by-layer self-assembly: the contribution of hydrophobic interactions. Nanostructured Mater. 1999, 12, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Pan, F.; Li, P.; Zhao, C.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Cao, X. Fabrication of ultrathin membrane via layer-by-layer self-assembly driven by hydrophobic interaction towards high separation performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 13275–13283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.Q.; Cheng, L.Y.; Xiao, J.X.; Han, X.N. Preparation and characterization of O-carboxymethyl chitosan–sodium alginate polyelectrolyte complexes. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2015, 293, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Li, B.L.; Li, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.Z.; Zhuo, R.X. Controlling the growth behaviour of multilayered films vialayer-by-layer assembly with multiple interactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009, 11, 8835–8840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.Y.; Li, Y.B.; Xu, J.; Geng, Y.F.; Zhang, J.Y.; Xie, J.L.; Zeng, Q.D.; Wang, C. Competitive influence of hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions on self-assembled monolayers of stilbene-based carboxylic acid derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 28625–28630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, P.T. Recent explorations in electrostatic multilayer thin film assembly. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2000, 4, 430442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decher, G. Fuzzy Nanoassemblies: Toward Layered Polymeric Multicomposites. Science (80-. ). 1997, 277, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, D.M. Peeling back the layers: Controlled erosion and triggered disassembly of multilayered polyelectrolyte thin films. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 4118–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Hong, J. Layer-by-layer assembly of multilayer films for controlled drug release. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2014, 37, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabler, C.L.; Sun, X.L.; Cui, W.; Wilson, J.T.; Haller, C.A.; Chaikof, E.L. Surface re-engineering of pancreatic islets with recombinant azido-thrombomodulin. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007, 18, 1713–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabuka, D.; Forstner, M.B.; Groves, J.T.; Bertozzi, C.R. Noncovalent cell surface engineering: incorporation of bioactive synthetic glycopolymers into cellular membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 5947–5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun Lee, D.; Hee Nam, J.; Byun, Y. Functional and histological evaluation of transplanted pancreatic islets immunoprotected by PEGylation and cyclosporine for 1 year. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 1957–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.S.; Park, W.; Na, K. Temperature-modulated noncovalent interaction controllable complex for the long-term delivery of etanercept to treat rheumatoid arthritis. J. Control. Release 2013, 171, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorena Cortez, M.; De Matteis, N.; Ceolín, M.; Knoll, W.; Battaglini, F.; Azzaroni, O. Hydrophobic interactions leading to a complex interplay between bioelectrocatalytic properties and multilayer meso-organization in layer-by-layer assemblies. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 20844–20855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadria, A. Tools to measure membrane potential of neurons. Biomed. J. 2022, 45, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopach, O.; Sindeeva, O.A.; Zheng, K.; McGowan, E.; Sukhorukov, G.B.; Rusakov, D.A. Brain neurons internalise polymeric micron-sized capsules: Insights from in vitro and in vivo studies. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzeczkowicz, A.; Gruszczynska-Biegala, J.; Czeredys, M.; Kwiatkowska, A.; Strawski, M.; Szklarczyk, M.; Koźbiał, M.; Kuźnicki, J.; Granicka, L.H. Polyelectrolyte membrane scaffold sustains growth of neuronal cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2019, 107, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, T.C.; Tao, L.; Hsieh, F.Y.; Wei, Y.; Chiu, I.M.; Hsu, S.H. An injectable, self-healing hydrogel to repair the central nervous system. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 3518–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hsu, S.H. Biomaterials and neural regeneration. Neural Regen. Res. 2020, 15, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Discher, D.E.; Mooney, D.J.; Zandstra, P.W. Growth factors, matrices, and forces combine and control stem cells. Science (80-. ). 2009, 324, 1673–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Q.; Eelkema, R. Self-Healing Injectable Polymer Hydrogel via Dynamic Thiol-Alkynone Double Addition Cross-Links. ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.R.; Ma, J.; Liu, B.F.; Xu, Q.Y.; Cui, F.Z. Layer-by-layer assembly of polyelectrolyte films improving cytocompatibility to neural cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2007, 81, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forry, S.P.; Reyes, D.R.; Gaitan, M.; Locascio, L.E. Facilitating the culture of mammalian nerve cells with polyelectrolyte multilayers. Langmuir 2006, 22, 5770–5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dąbkowska, M.; Stukan, I.; Kowalski, B.; Donerowicz, W.; Wasilewska, M.; Szatanik, A.; Stańczyk-Dunaj, M.; Michna, A. BDNF-loaded PDADMAC-heparin multilayers: a novel approach for neuroblastoma cell study. Sci. Reports 2023 131 2023, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzeczkowicz, A.; Gruszczynska-Biegala, J.; Czeredys, M.; Kwiatkowska, A.; Strawski, M.; Szklarczyk, M.; Koźbiał, M.; Kuźnicki, J.; Granicka, L.H. Polyelectrolyte membrane scaffold sustains growth of neuronal cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2019, 107, jbm.a.36599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.C.; Wang, J.H.; Chen, Y.A.; Tsai, L.K.; Young, T.H.; Ethan Li, Y.C. A self-assembled layer-by-layer surface modification to fabricate the neuron-rich model from neural stem/precursor cells. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2020, 119, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, F.S.Y.; Chan, B.P.; Lo, A.C.Y. Carriers in Cell-Based Therapies for Neurological Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 10669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y. 3D Printing and Bioprinting Nerve Conduits for Neural Tissue Engineering. Polym. 2020, Vol. 12, Page 1637 2020, 12, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandayuthapani, B.; Yoshida, Y.; Maekawa, T.; Kumar, D.S. Polymeric Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering Application: A Review. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2011, 2011, 290602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowska, A.; Granicka, L.H.; Grzeczkowicz, A.; Stachowiak, R.; Kamiński, M.; Grubek, Z.; Bielecki, J.; Strawski, M.; Szklarczyk, M. Stabilized nanosystem of nanocarriers with an immobilized biological factor for anti-tumor therapy. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0170925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Bayachou, M. Layer-by-layer fabrication and characterization of DNA-wrapped single-walled carbon nanotube particles. Langmuir 2005, 21, 6086–6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byon, H.R.; Lee, S.W.; Chen, S.; Hammond, P.T.; Shao-Horn, Y. Thin films of carbon nanotubes and chemically reduced graphenes for electrochemical micro-capacitors. Carbon N. Y. 2011, 49, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Hong, T.K.; Kang, D.; Lee, J.; Heo, M.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, B.S.; Shin, H.S. Highly controllable transparent and conducting thin films using layer-by-layer assembly of oppositely charged reduced graphene oxides. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 3438–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Kotov, N.A. Composite Layer-by-Layer (LBL) assembly with inorganic nanoparticles and nanowires. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1831–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariga, K.; Lvov, Y.M.; Kawakami, K.; Ji, Q.; Hill, J.P. Layer-by-layer self-assembled shells for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 63, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, X.; Lu, G.; Tsuchida, E.; Komatsu, T. Protein nanotubes comprised of an alternate layer-by-layer assembly using a polycation as an electrostatic glue. Chemistry 2008, 14, 10303–10308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, M.P.; Chavali, M.S. Metal Oxide Nanoparticles as Biomedical Materials. Biomimetics 2020, Vol. 5, Page 27 2020, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaan, A.F.; Piedade, A.P. Electro-responsive polymer-based platforms for electrostimulation of cells. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 2337–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybowska-Sarapuk, Ł.; Sosnowicz, W.; Grzeczkowicz, A.; Krzemiński, J.; Jakubowska, M. Ultrasonication effects on graphene composites in neural cell cultures. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 992494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, A.; Huang, X.; Fan, S.; Yao, X.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, Y. One-Step Approach to Prepare Transparent Conductive Regenerated Silk Fibroin/PEDOT:PSS Films for Electroactive Cell Culture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, N.; Kachappilly, M.C.; Bhushan, V.; Pandya, H.J.; Basu, B. Electrical field stimulated modulation of cell fate of pre-osteoblasts on PVDF/BT/MWCNT based electroactive biomaterials. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2023, 111, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, I.; Cerqueira, G.; Varella Penteado, F.; Córdoba de Torresi, S.I. Electrical Stimulation and Conductive Polymers as a Powerful Toolbox for Tailoring Cell Behaviour in vitro. Front. Med. Technol. 2021, 3, 670274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, T.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Gou, M.; He, C. Percutaneous electrical stimulation combined with conductive nerve guidance conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 511, 162124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Action | Description | Examples |

| Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Actions | ||

| Oxidative Stress Mitigation | NPs can scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS), protecting neurons from oxidative damage. |

|

| Inflammation Modulation | NPs can decrease proinflammatory cytokines, creating a favorable environment for nerve regeneration. | |

| Enhancing neuronal viability | NPs can reduce cellular apoptosis. | |

| Promotion of Axonal Growth and Myelination | ||

| Axonal Regeneration | Surface-modified NPs can guide axonal growth by mimicking extracellular matrix structures. |

|

| Myelination Support | NPs can promote axon remyelination. | |

| Enhanced Drug Delivery | ||

| Targeted Delivery | Functionalized NPs can cross biological barriers and deliver therapeutic agents directly to injury sites, minimizing off-target effects. |

|

| Controlled Release | NPs can provide sustained release of therapeutics, reducing the need for frequent dosing and maintaining effective drug concentrations at the injury site. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).