1. Introduction

The Peripheral nerve injuries (PNI) may cause partial to complete loss of sensory and motor function leading to loss of independence, chronic pain, and a significant decline in quality of life. Injury to nerves may be caused by trauma, infection, surgical complication, compression, or autoimmune and metabolic disorders.1 Currently, more than 20 million people in the US are estimated to suffer from some form of PNI.2 This has amounted to an annual expenditure of $1.1 billion on surgical treatment of nerve injuries and $150 billion on overall healthcare dollars to manage these injuries.3 Despite such costs and efforts in nerve repair and reconstruction, the functional recovery, as defined by the return of motor function and sensation, is less than 50%.4,5 Given these poor results, nerve surgeons are in need of innovative approaches that enhance nerve regeneration following repair or reconstruction to enhance the reinnervation potential of nerves and provide better more consistent outcomes to patients sustaining such devastating injuries.

Currently, for injuries with a minimal gap, nerves may be repaired in an end-to-end fashion as long as this is performed in a tension-free fashion. For more severe injuries in which nerves are unable to be repaired in a tension-free fashion, the use of conduits, processed allograft, and autograft are indicated as dictated by the gap size. As conduits lack cross-sectional architecture, their use is best supported for small gaps, commonly less than 1cm but up to 3cm in some clinical situations.6 For longer gaps, processed allografts or autografts are most frequently used. Processed allografts provide the native cross-sectional and longitudinal architecture of nerves, but processing of these nerves to remove immunogenic concerns removed cells, signaling proteins, and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, which could be key to regeneration.7 As a result, cells and proteins needed to initiate and sustain a regenerative microenvironment are significantly reduced. Autograft delivers both the architecture as well as the cells, growth factors, and ECM proteins needed for regeneration. However, their use requires a donor site adding to risk of hematoma, wound healing, and infection complications, loss of donor nerve function, risk of neuroma generation, and a period for Wallerian degeneration to prepare the autograft to become an appropriate regenerative construct.8 Given the pros and cons of each of these modalities, our lab sought to create a graft predicated upon a readily available biomimetic multi-channel cross-sectional graft that harbors chemotactic and regenerative properties while bypassing donor site morbidity in order to best guide cellular migration and axonal regeneration.

In developing this graft, Matrilin-2 (MATN2), a protein from the matrilin family of ECM proteins, which has been shown to enhance Schwann cell (SC) migration and axonal outgrowth was integrated into chitosan, a bioactive and biodegradable polysaccharide, with a lysine augmentation to form a bioactive multi-channel scaffold.9–14 In-vitro testing of this scaffold in our lab found a significant increase in SC adhesion and migration compared to a conduit.15 A subsequent ex-vivo study using dorsal root ganglions demonstrated greater neuronal adhesion and axonal outgrowth when placed upon the scaffold.15 Expanding upon our in-vitro and ex-vivo results, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the MATN2 and lysine enhanced chitosan (K-chitosan) scaffold into a rat sciatic nerve defect and compare functional and regenerative outcomes to a clinically used conduit and autograft. We hypothesized that the implementation of a biomimetic scaffold that enhances Schwann cell adhesion and migration and is supportive of axonal outgrowth will offer better functional, electrophysiological, and histological outcomes than a conduit and be comparable to autograft.

2. Results

2.1. Functional Outcome Measurements

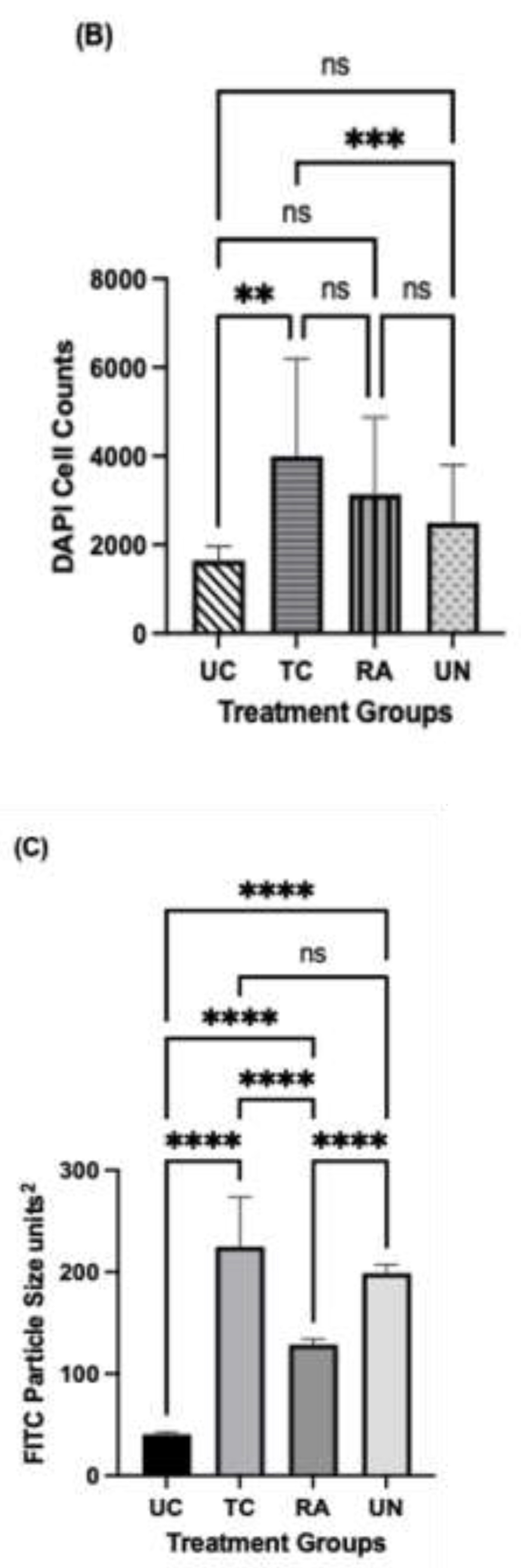

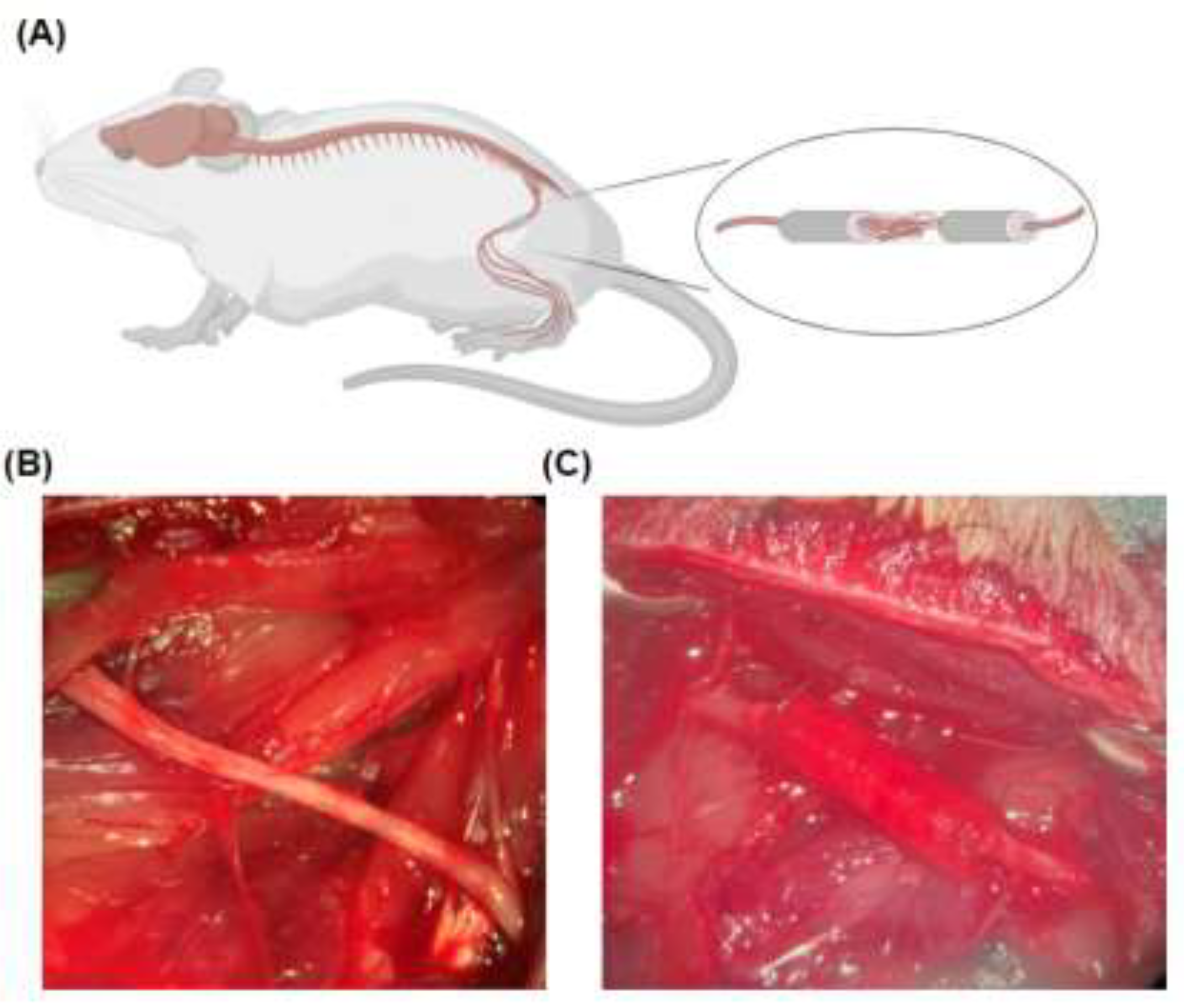

The 3D scaffold of matrilin-2 with K-chitosan in a collagen conduit was prepared as described previously15 and illustrated in Figure 6. The conduit was implanted during rat sciatic nerve reconstruction surgery (Figure 8). Gait analysis was conducted (Figure 7) to measure functional outcomes as follows.

2.2. Walking Track Force Analysis

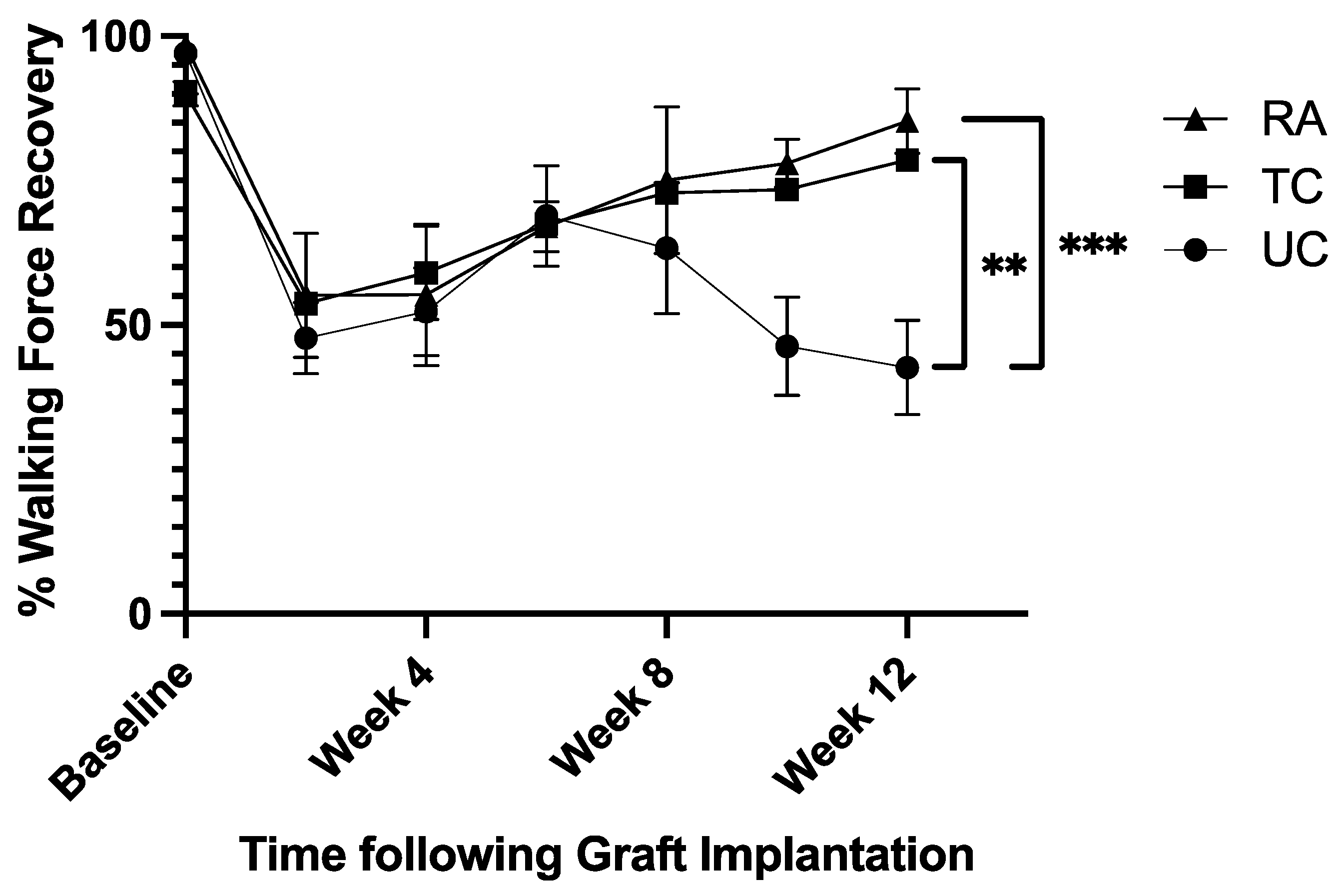

Walking track analysis evaluated the proportion of force placed on the treated left hindlimb (LHL) compared to the control right hindlimb (RHL). Baseline values averaged 95.1% ±4.5% over all three groups. Following sciatic nerve reconstruction, walking force fell to an average of 52.2% ± 3.9% following surgery. The untreated conduit (UC) group fell to 42.6% ± 8.2% by week 12 (

Figure 1), while the treated conduit (TC) and reverse autograft (RA) groups steadily rose to 78.5% ± 1.4% and 85.2% ± 5.6%, respectively (

Figure 1). Analysis of week 12 force measurements found significant differences between UC vs TC groups (p=0.0035) and UC vs RA groups (p=0.001) (

Figure 1). There was no significant difference in walking force r

R4

2.3. Compound Muscle Action Potential (CMAP)

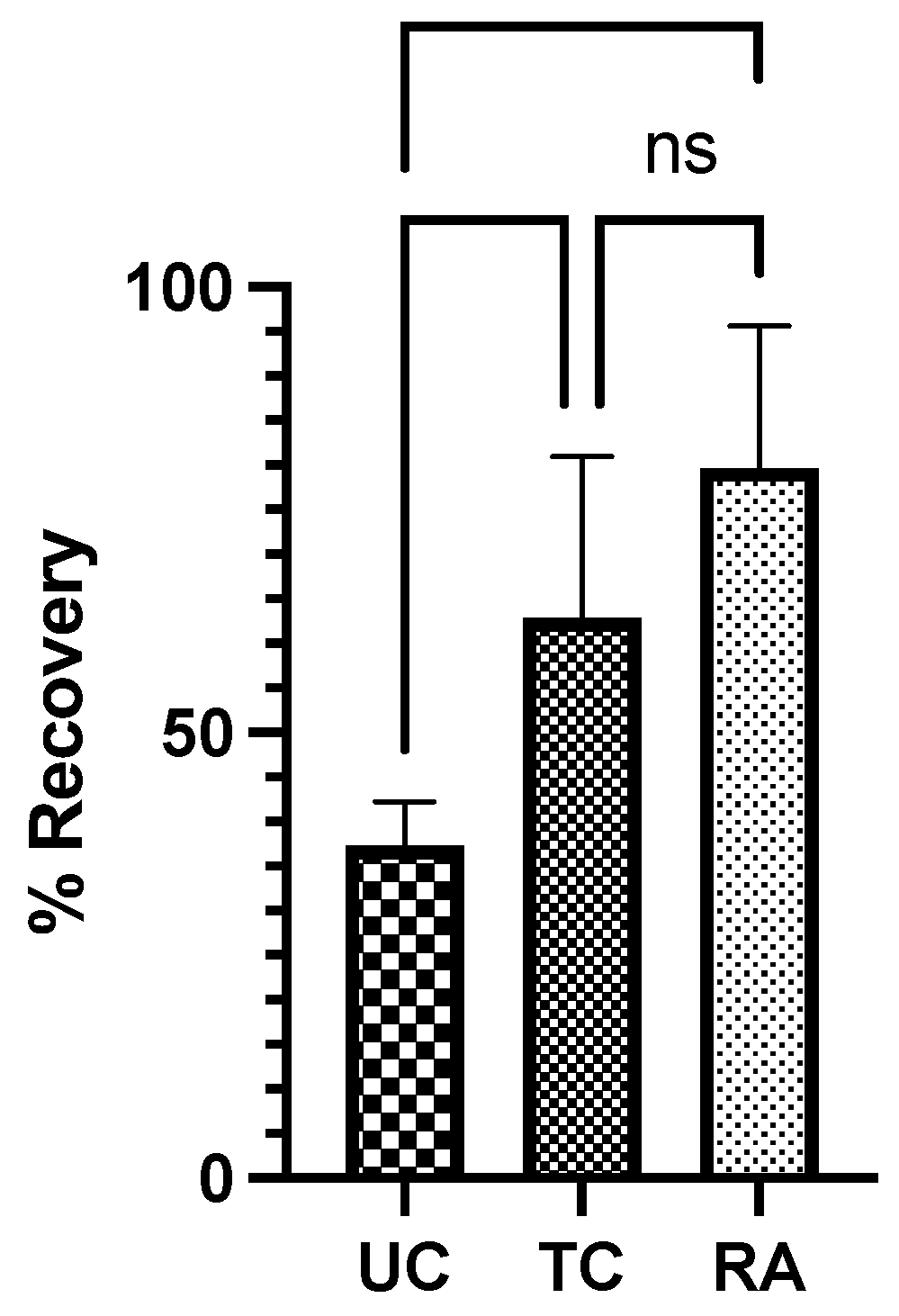

The CMAP was evaluated to the gastrocnemius of each rat to generate a proportion of sciatic recovery of the experimental LHL to the control RHL. The UC group demonstrated a mean recovery of 37.3% ± 4.95% compared to the normal RHL. Comparatively, the TC group had a 62.9% ± 18.1% recovery and RA group had a 79.7% ±15.9% recovery (

Figure 2). Significant differences in proportional recovery were found between UC vs TC (p=0.044) and UC vs RA groups (p=0.0013). No difference was found between the TC and RA groups (

Figure 2).

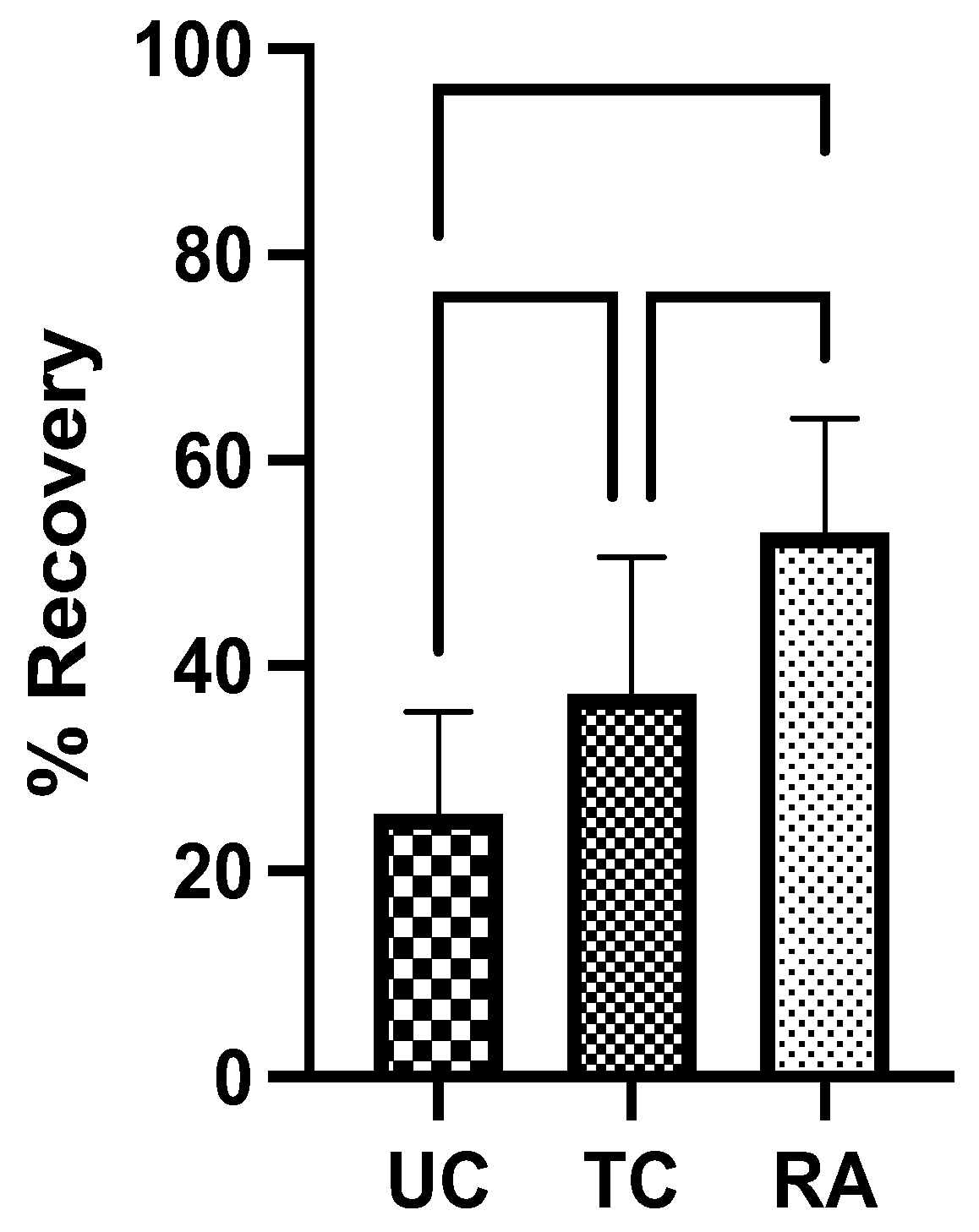

2.4. Tibialis Anterior and Gastrocnemius Muscle Weights

TA and GSC muscle weights of experimental LHL were normalized to RHL determine the percentage of LHL muscle that remained and level of denervation atrophy. The UC group had the lowest weight of preserved muscle at 25.6% ± 9.93% followed by TC group at 37.2% ± 13.4%. The RA group had the greatest proportion of remaining muscle at 52.9% ± 11.1%. Significant differences in muscle weight were identified between UC vs TC groups (p=0.0202) and TC vs RA groups (P=0.0030) (

Figure 3). The most notable difference, however, was noted between UC vs RA groups (P<0.0001) (

Figure 3).

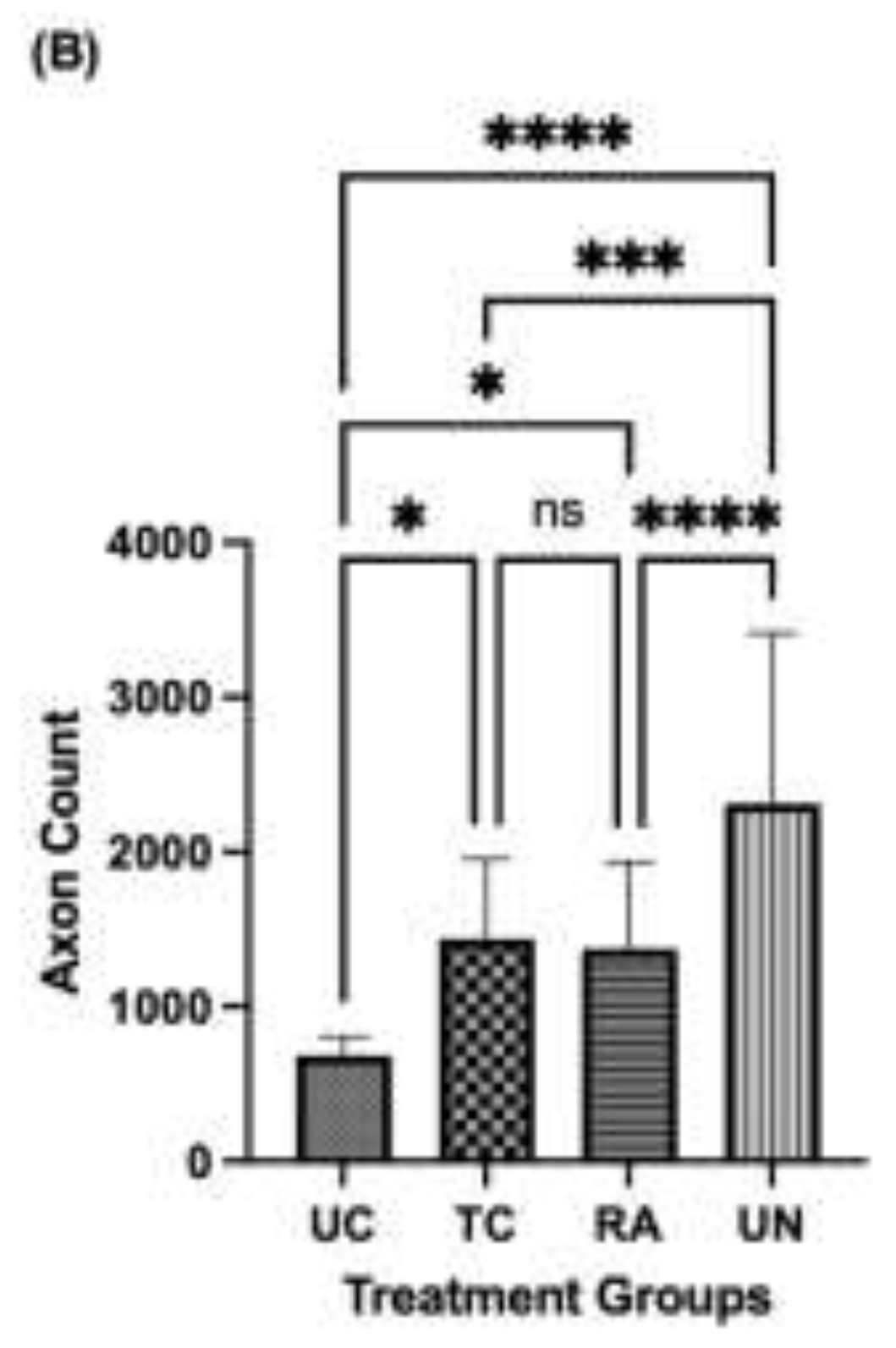

2.5. Axon Analysis

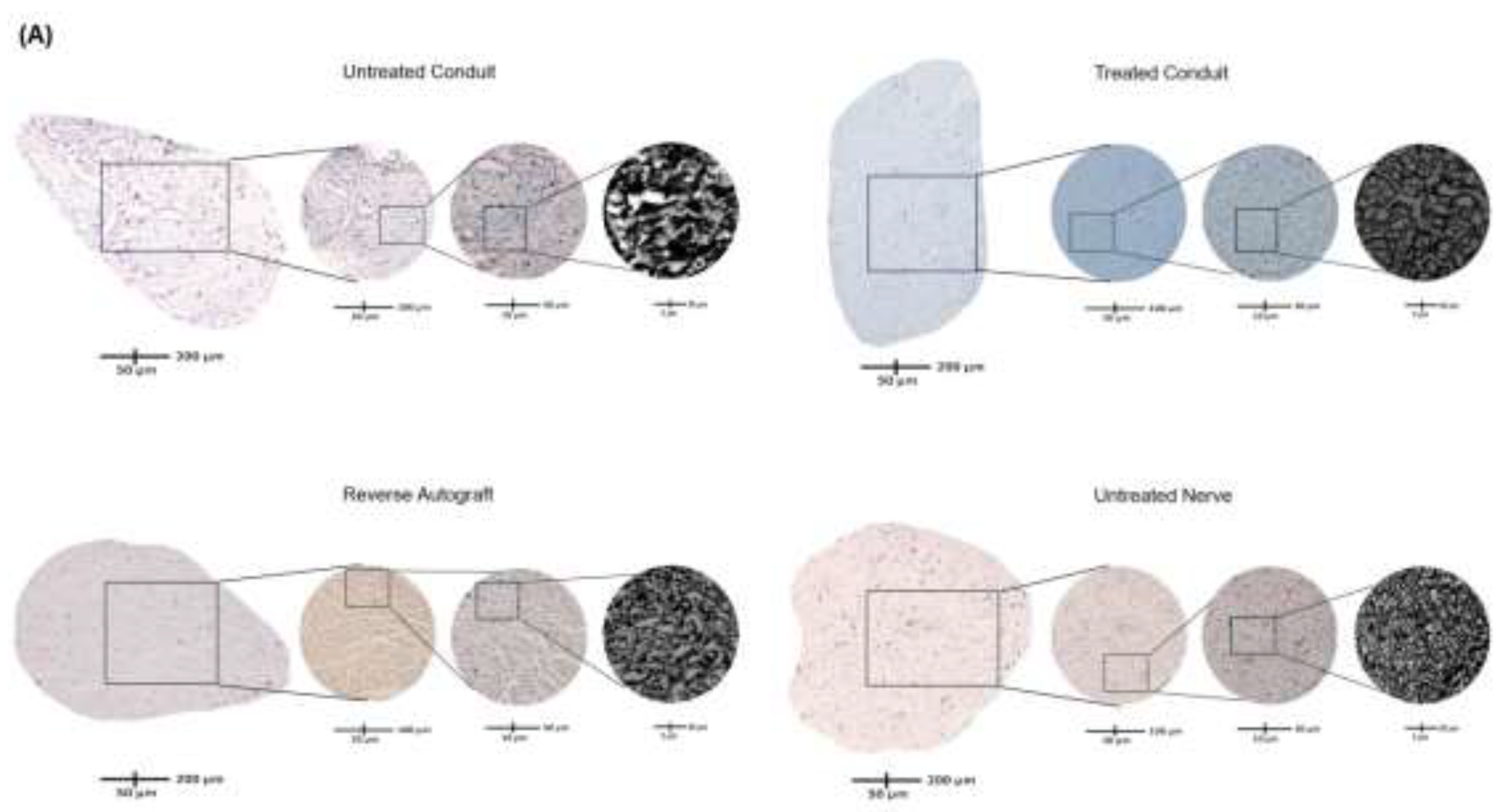

The number of regenerated axons were visualized by toluidine blue staining and counted at the distal nerve stump immediately distal to the conduit and autograft reconstruction suture sites. Doing so ensured consistency in capturing the number of axons that were able to successfully traverse the segmental defect and be compared across native nerve. Each identified axon was counted for the entirety of the cross-section for each nerve. Grossly, the density of axons in the UC group were reduced compared to the TC, RA, and uninjured (UN) groups (

Figure 4A). The lack of axonal density in the UC group was met with a greater degree of disorganized connective tissue. Comparatively, the TC group demonstrated more connective tissue organization and axonal density. Quantitative analysis of axon number revealed a mean of 686.0 ± 117.4 axons for UC, 1,438 ± 514.5 axons for TC, 1,374 ± 565.2 axons for RA, and 2,270 ± 1,1103 axons for UN (

Figure 4B). Significant differences in axon number were counted between UC vs TC (P=0.0331), UC vs RA (P=0.0433), UC vs UN (P<0.0001), TC vs UN (0.0019), and RA vs UN (P=0.0002). No significant differences were noted between TC and RA (P=0.9939).

2.6. Schwann Cell Immunofluorescence

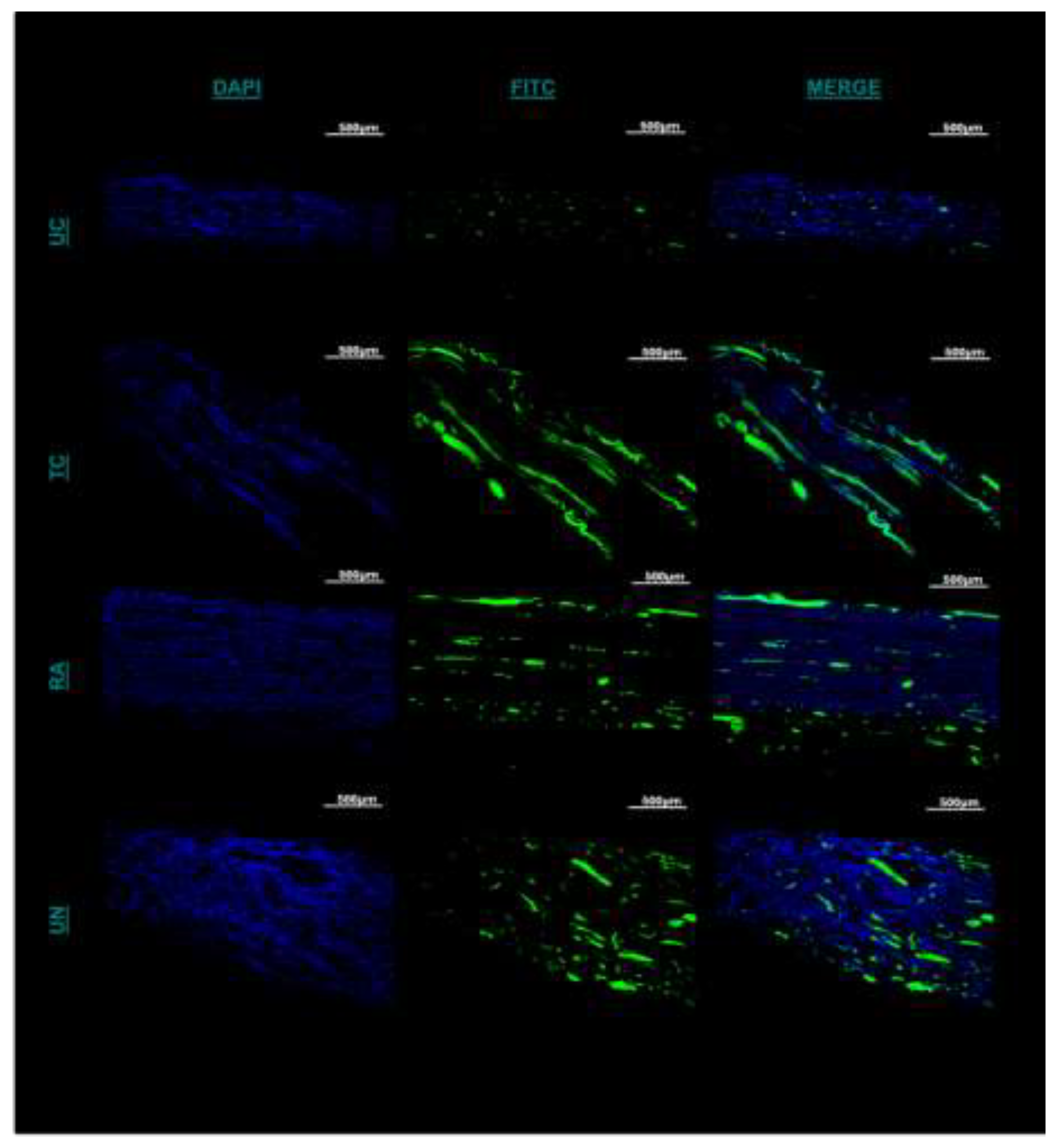

Immunofluorescent staining was utilized to evaluate the presence and distribution of Schwann cells (SCs) within the untreated and treated conduit and autograft of the reconstructed sciatic nerve at its distal most extent. Between the UC and TC imaging, there was greater cross-sectional conglomeration of SCs and DAPI positive cells within the TC than the UC (

Figure 5A). The UC SC distribution was contingent to the central localized area within the empty conduit rather than the entirety of the cross-section (

Figure 5A). More structured longitudinal and cross-sectional populations of SC fluorescence was visualized within the TC compared to the UC and more confluent compared to the RA (

Figure 5A). When quantifying cell number by DAPI, significant differences were noted between UC, TC, and RA. TC, demonstrated significantly greater cell counts than UN (p=0.00082) and UC (p=0.0072) (

Figure 5B). Furthermore, TC demonstrated higher affinity to SC clustering and propagation than in any other treatment group as noted from larger fluorescent particle sizes as measured in (

Figure 5C). Significant differences were noted with TC between TC and UC (P=0.0064) and TC and UN (P=0.0003). No difference was noted between TC and RA. Together such findings demonstrate the chemotactic potential of the matrilin-2/k-chitosan scaffold given the high number of SC counts. The larger particle sizes noted within TC further support the migration and adhesion for Schwann cell chemotaxis to host a more normalized nerve microenvironment as seen in the uninjured nerve.

3. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the in vivo impact of a MATN2 and K-Chitosan scaffold on rat sciatic nerve regeneration of a segmental defect compared to no scaffold and use of an autograft. Rats from each group were tested functionally with gait trials, from which restored TC paw pressures were greater than UC and equivalent to RA at 12 weeks. Prior to sacrifice, nerve conduction to the gastrocnemius was assessed with CMAP, revealing TC with great conduction and muscle activation to the gastrocnemius than UC and was comparable to RA. Muscle weight demonstrated the least atrophy in RA and significantly less atrophy in TC compared with UC. Finally, regenerated axonal number was quantified at the distal stump noting a greater number of regenerated axons in TC compared to UC with no significant differences to RA. Immunofluorescent evaluation of SC quantity and distribution noted greater spatial distribution and quantity in TC compared to UC with equivocal findings to RA. The inset of the Matrilin-2/K-chitosan scaffold into a commercial collagen conduit significantly increased functional, electrophysiologic, and histological measures of nerve regeneration compared to the hollow conduit. In comparison to RA, functional measures such as paw pressures on walking track analysis and muscle innervation by CMAP evaluation as well as axonal counting and Schwann cell profiles were comparable. These findings support the regenerative benefit housed within a readily available matrilin-2 and lysine-enhanced chitosan scaffold that advances Schwann cell migration and axonal regeneration comparable to reverse autograft following segmental nerve injury.

3.1. Importance of Microarchitecture

Following nerve injury requiring segmental reconstruction, successful regeneration occurs as axons from the proximal nerve stump are able to traverse the defect and reach their respective muscle and sensory targets. A crucial mechanism for this to occur resides in Schwann cells and their migration ability. These once-myelinating cells are needed to dedifferentiate into reparative cell phenotypes and begin the migration across the injury site to facilitate the formation of the bands of Büngner that ultimately provide a guide for axonal outgrowth.16 For this to occur, the extracellular matrix microarchitecture and its composition is a major factor implicated in supporting the migration of Schwann cells. The inner composition of nerve consists of a complex network of factors including collagen, laminin, fibronectin, and matrilin-2 that situate and physically suspend regenerative cellular components.17,18 As it relates to nerve regeneration, this microarchitecture offers contact forces, both attractive and repulsive, which affect the migration of Schwann cells and chemotaxis of immune cells along the length of nerve.19 A major deficit of basic conduit repair is the deprivation of a cross-sectional microstructure to support the regenerating axons. Recreating this microarchitecture has recently become a major point of study in peripheral nerve regeneration. Many intra-conduit structures have been tested in their impact on neurite outgrowth, including carbon nanotubes, embedded axons, growth factors, and even Schwann cells.20–22 In this study, our novel approach outside the need to seed scaffolds with cells or growth factors was through the combined use of MATN2, an extracellular matrix protein, and chitosan, a natural biopolymer, each with strong regenerative properties in peripheral nerve to create a porous biomimetic scaffold.

3.2. Benefits of Matrilin-2

The derivation of this scaffold is centered upon the biomimetic influence of matrilin-2 (MATN2) previously shown to provide greater Schwann cell migration and adhesion as well as axonal outgrowth10,15. Matrilin-2 is a highly expressed protein in extracellular matrices throughout the body including skin, cartilage, bone, uterus, and many other sites.23 It has been found crucial and necessary for peripheral nerve regeneration to occur, with Malin et al. finding delayed regrowth and functional recovery in MATN2 deficient mice.11 In malignant pilocytic astrocytoma, MATN2 was upregulated further suggesting its specific contribution to nerve growth.24 One of the main functions of MATN2 is to modulate the collagen of ECM, forming interactions with itself and other matrix proteins to create orderly networks of elongated fibrils.25 These fibrillar structures offer structural and biological incentives for axonal outgrowth, as seen with an ideal porosity for attractive forces for migration as well as cell adhesion molecules for catecholamine-producing PC12 cells. MATN2 poses uniquely beneficial properties for inclusion into scaffolds for nerve regeneration.26,27 Prior in vitro studies have shown MATN2 performing better than other ECM components, namely fibronectin and laminin, in stimulating SC migration.11 Given the individually favorable characteristics of MATN2 and chitosan, the combination of these components offers a biomimetic scaffold with the ability to cross-sectionally enhance SC migration and thereby promote a more robust regenerative response.

3.3. Benefits of Chitosan

Chitosan is a polysaccharide-based biopolymer that has been studied for its potential to create a porous environment like native ECM.28 It has beneficial effects for axonal outgrowth including cell adhesion, biodegradation, and biocompatibility. Chitosan is a polycationic polysaccharide whose charge gives it bioactivity in associating with anionic electrolytes and anionic regions of cell membranes as well as antimicrobial effect in disrupting bacterial cell walls.29,30 As a biopolymer, chitosan can be naturally degraded by native enzymes, creating byproducts known as chitooligosaccharides (COS). These COS stimulate SC production of macrophage-attracting factors such as chemokine ligand 2, which in turn, promotes M2-polarized macrophages to the site of injury, which induces microenvironment tissue repair changes through IL-10 and IL-13 secretion.31,32 As a result of these properties, chitosan has been used in a variety of methods for nerve regeneration.33,34 Engineered chitosan matrices have been shown to provide beneficial porosity and surface area to volume ratio for inflammatory factors, SCs, and axon sheaths to traverse appropriately.35 Chitosan conduits have been created and seeded with varying cell types, muscle, hydrogels, and deacetylation profiles with varying outcomes in rat sciatic nerve models.36–38 However, unique to this study was the modification of the amine group with the addition of lysine in order to enhance the cationic character of the biopolymer to ultimately enhance cellular and protein affinity. The use of lysine-enhanced chitosan allowed for the cross-sectional and longitudinal presence of MATN2 to host a chemotactic enhancement of SC migration and axonal regeneration.

3.4. Functional Outcomes

Following nerve reconstruction, nerve and muscle function are goal-oriented parameters to analyze the rate and quality of regeneration. In this study, we assessed 1) muscle function with an automated gait analysis trial, 2) nerve function with CMAP, and 3) muscle restoration with muscle mass measurement.39–42 In the walking trial, we found that TC exhibited greater use of the reconstructive hindlimb compared to UC, suggesting increased axonal regeneration and signal passage through the MATN2/K-chitosan scaffold. No differences were found between RA and TC at 12 weeks suggesting TC harbors enough axonal regeneration to support a greater functional return than UC. Secondly, CMAP assessment of nerves quantifies their functional return of axonns through the reconstruction site to support muscle function. We found that RA provided increased amplitude and frequency of signal compared with both TC and UC, with TC performing better than UC. This suggests that presence of the matrilin-2 and lysine-enhanced chitosan scaffold provides more functional axonal regeneration to muscle targets compared to empty conduits. Finally, weight of the gastrocsoleus and tibialis anterior complexes at the end of the study period, marking the degree of denervation atrophy, revealed the most preserved muscle was with autograft reconstruction.43 However, rats with matrilin-2 and lysine-enhanced chitosan scaffold reconstruction demonstrate greater preservation of muscle than those with conduit reconstruction, further supporting Schwann cell migration and axonal regeneration through reinnervation of muscle.

3.5. Axonal Regeneration and Schwann Cell Migration

Cross-sections of the distal nerve stump from the reconstructive zone after the study period revealed variance in microarchitecture, axon count, and myelination. Conduit reconstruction demonstrated large gaps between axons and overall poorly developed microarchitecture owing to decreased cross-sectional support in the conduit environment. In accordance, the quantity and distribution of SCs under immunofluorescence was few and more narrowly centralized in the conduit group. In contrast, TC demonstrated a greater number of axons compared to UC. In addition, the immunofluorescence evaluation demonstrated a greater cell number and Schwann cell fluorescence with TC compared to UC. When comparing against autograft and normal nerve, there was a significantly greater number of axons in normal nerve but no statistical difference when comparing TC to autograft. On fluorescence evaluation, Schwann cell confluence, migration, and propagation were best seen between TC and UN with quantification of fluorescence number and size having no significant difference between these two groups. These results further exemplify the crucial role and presence of SCs to cater a microenvironment most conducive to regeneration and restoration of normal physiology.35 Thus, the presence of a biomimetic scaffold using MATN2 and chitosan to enhance SC chemotaxis through the extent of the scaffold is a key crucial attribute to the development of this scaffold that also draws upon a chitosan backbone with previously demonstrated macrophage chemotaxis properties .11,15 Together the chemotactic and biomimetic potential of this scaffold permits a more robust cellular response to best enhance peripheral nerve regeneration and functional return.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of Matrillin-2

Preparation of our matrilin-2/lysine-enhanced chitosan scaffold has been previously described.

15 In brief, Chitosan was dissolved at 2% (w/v) in 1% (v/v) acetic acid solution with stirring at room temperature to form a homogenous gel. A lower molar ratio of lysine was then added to bind the free amine groups on the chitosan chain and further stirred to form a homogenous gel once more. N,N’-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) was then added as a coupling reagent to trigger the reaction followed by dialysis to remove the DCU byproduct. Glutaraldehyde was added to form the crosslinking between lysine and chitosan. Upon completion, matrilin-2 was added using a displacement pipette and mixed by continuous pipetting until homogeny was achieved. The gel was then pipetted into a type 1 collagen conduit (Integra Lifesciences, Princeton, NJ) and lyophilized until a dry, porous structure formed (

Figure 6).

4.2. Animals

All animal experiments and procedures were performed in strict accordance with the National Institute of Health Guidelines for Laboratory Animal Care and Safety, and with approved protocols by the Lifespan Animal Welfare Committee (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee No. 500220). Male adult Lewis Rats (220-250g) were used and given ad libitum access to water and food over a 12h light/dark cycle.

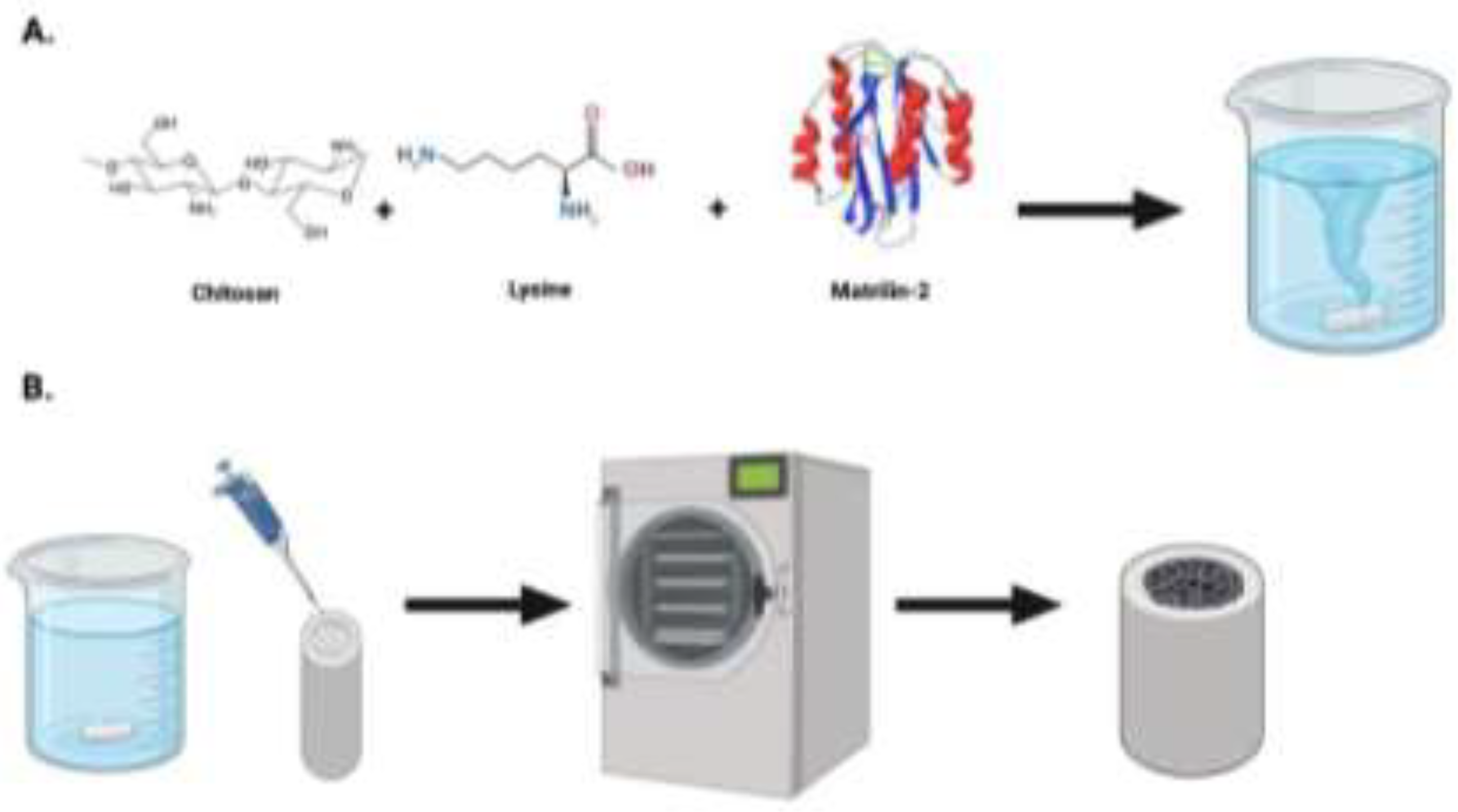

4.3. Gait Analysis

Prior to undergoing surgery, each rat underwent gait pattern analysis to mark preoperative levels of hindlimb paw pressure. Gait patterns were analyzed using a pressure sensor mat (Tekscan VH4, Tekscan, Boston, MA), which is composed of four 5,101 high-resolution pressure sensor grids laid out side by side. The gait testing unit was modified to include a tinted Plexiglas tunnel (width 17.0 cm, height 17.0 cm, length 44.7 cm) for the purpose of guiding the rats across the mat and ensuring that the rats remained

on the sensor area during the gait trial (Figure 7). This minimized false data recordings from animal false steps on the edges or outside the sensor matrix area. Following preoperative evaluation, rats then underwent gait assessment every 2 weeks after surgery over the course of the 12-week study period. A separate male Lewis rat (non-testing) was systematically put in the goal box to motivate the trial rats to run towards it. The same motivator rat was used for all animals and in all test sessions. In case the animal was not motivated by the goal box, alternative positive motivators were used such as noise and food reward. During the data analysis, steps were automatically labeled as right fore paw (RF), right hind paw (RH), left fore paw (LF), and left hind paw (LH), in which the right stands for the non-impaired side and the left for the impaired side. Faulty labels caused by tail, whiskers, or genitalia were removed. After the identification of individual footprints, we performed an automated analysis of a wide range of parameters. Data were classified as follows: (1) individual paw statistics; (2) comparative paw statistics; (3) interlimb coordination; (4) temporal parameters. A gait trial was considered successful if it consisted of three runs across the full-length of the Tekscan

4.4. Sciatic Nerve Defect and Reconstruction Model

After undergoing preoperative walking track analysis, the rats proceeded to surgery. Three groups each contained 10 rats. The groups studied were 1) untreated conduits (UC) serving as negative control, 2) conduit with matrilin-2/lysine enhanced chitosan scaffold (TC), and 3) reverse autograft (RA) serving as positive control. For each rat, the left hindlimb was the operative limb and the right hindlimb served as control. The rats were first anesthetized with 2% isoflurane. The skin on the left thigh was thoroughly prepped, draped, and positioned under a microscope. The limb was incised to expose the left sciatic nerve. At a midline focused at 10mm from the trifurcation of the sciatic nerve, a 12 mm segment of nerve was excised, 6mm on each side of the midline. From the proximal and distal stumps, 2 mm of each stump was drawn into a 16 mm long UC or TC such that a 12 mm gap was kept between the nerve ends (). To mirror the length of the gap, the reverse autograft entailed resection of 12mm of sciatic nerve, flipped 180° and sutured to each end. The conduit or autograft were each reconstructed with 10-0 nylon monofilament suture in epineural repair fashion under the microscope. The wound was closed and the animals, after awaking postoperatively, were returned to individual cages with food and water ad libitum for 12 weeks with body weight monitored weekly.

4.5. Compound Muscle Action Potential Testing

Electrophysiological analysis was performed at 12 weeks postoperatively as previously described.44 Electrical stimulation was applied to the nerve by placing bipolar hooked silver stimulating electrodes proximal to the conduit or reverse autograft. The stimulating mode was set as a pulsed mode (5 mA stimulus intensity, 1 Hz frequency, 1 ms duration). A pair of concentric needle electrodes were inserted into the belly of the gastrocnemius muscle alongside a reference surface electrode near the distal tendon and ground electrode in the tail. Amplification and recording were performed with a data acquisition system (Powerlab 8/35, AD Instruments Inc., Colorado Springs, CO, USA). Signals were recorded using Labchart software (AD Instruments) connected to a Bio-amplifier (Bioamp, AD Instruments). The peak-to-peak amplitude and onset latency of CMAPs were measured for the UC, TC, and RA groups. The amplitude was defined as the height by the signal level minus the baseline at the peak; the latency was defined as the time interval from the stimulus artifact to the start of the response). The measurements were all conducted at room temperature. Peak-to-peak amplitudes of CMAPs were identified for each hindlimb of the rat and reported as a proportion of CMAP from the experimental LHL to the control RHL. Immediately following electrophysiologic testing, rats were rendered unconscious by exposure to CO2, and irreversible death was confirmed via thoracotomy.

4.6. Nerve and Muscle Extraction

Upon sacrifice, sciatic nerves encompassing the conduit and reverse autograft were harvested from the left hindlimb as well as normal sciatic nerve from the right hindlimb. Each conduit or autograft nerve was excised with 3 mm of native nerve stump present proximally and distally. The tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles were then harvested off the tibia from both the right and left hindlimbs. These muscles were weighed as a unit and reported as a proportion of weight from the experimental LHL to the control RHL for each rat.

4.7. Axon Analysis

Upon harvesting of the sciatic nerves, they were rinsed in ice-cold PBS and were then placed into solutions of 4% paraformaldehyde to begin the fixation process at 4C for 3 hours. Following fixation, they were then rinsed in PBS 3x5min and placed into graduated concentrations of sucrose. Samples were placed in 10% sucrose for 30 minutes, followed by 20% sucrose for 30 minutes, and finally at 30% sucrose for 30 minutes. The nerves were then separated into two categories based on purpose. The distal 3mm from the distal nerve coaptation was separated for axonal histomorphometry. The proximal nerve containing the conduit or the reverse autograft was then used for immunofluorescent evaluation of Schwann cell migration and distribution. The distal 3mm segment was then placed into a tray, filled with Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound, frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C. The blocks were then cross-sectioned into 1 µm sections and stained with Toluidine Blue. The transverse sections were then visualized using a digital microscope and photographed under blinded conditions of treatment group to each slide. In ImageJ®, total area of the axonal cross-section was measured by converting pixels to micrometers via the digital scale bar. After formatting the image to 16-bit and converting the image black and white, ImageJ’s cell-counting feature was used to count the number of axons within the nerve segment through analyzing particle count through the binary reversal of highly contrasted axons in blinded fashion.

4.8. Schwann Cell Immunofluorescence

The proximal nerve conduit and reverse autograft were placed into trays, filled with Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound, flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored in -80°C until sectioning. Cryosectioning was performed in a longitudinal fashion to best understand the spatial distribution of Schwann cells within the conduit or graft. Sectioning occurred at 10µm thick sections ensuring 5 slices were taken for staining every 200 µm through the samples. The centrally localized longitudinal sectioned tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 3 hours and then incubated with blocking solution (5% normal goat serum) for 1 hour. Subsequently, the tissues were incubated overnight at 4 ℃ with S-100 (Santa Cruz sc-53438) at 1:50 ratio in antibody dilution reagent solution (Invitrogen #003218). This was followed by incubation with Alex Fluor 594 Fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour in the dark at 1:200 ratio (Invitrogen #A11032). The tissues were then rinsed with PBS and mounted with an anti-fade media (H-1200). The tissues were then observed under confocal microscopy under blinded conditions of the treatment group to each slide. Images were captured using a 4x objective magnification lens for DAPI and 10x objective magnification lens for FITC. Fluorescent images were converted into 16-bit black and white images. ImageJ’s fluorescent quantification system was used to count the number of DAPI and FITC fluorescent signals presented in each image with auto color threshold optimization. The size of average particle per area in unit2 was also collected through the system’s output measurements.

5. Conclusions

This study highlighted the therapeutic potential of extracellular matrix-based biomimetic nerve grafting for peripheral nerve regeneration. The utilization of a novel matrilin-2 (MATN2) and Lysine (K)-enhanced chitosan scaffold formed a multichannel microarchitecture capable of providing a microenvironment that supports SC migration and axonal regeneration. Improved functional outcomes were observed in walking tasks and CMAP when applying the MATN2/K-chitosan scaffold, accompanied by a relative decrease in muscle atrophy compared to the use of a conduit. Detailed histological analysis of nerves within the MATN2/K-chitosan scaffold revealed a greater axonal number, SC migration, and distribution, further supporting the regenerative biomimetic appeal of this cell-free scaffold. This work provides a basis for the use of MATN2 as an integral protein for the development of novel nerve repair strategies along with the versatility of chitosan to form a readily available matrix that avoids the morbidity associated with autograft and delivers bioactivity that is poorly present in processed allograft. These promising results also offer intriguing future avenues for investigation centered through optimizing nerve regeneration through enhanced study and detailing of the biomimetic activity involved within the neural extracellular matrix. While this study provides a preliminary foundation for understanding the potential of MATN2/K-chitosan scaffold in nerve reconstruction, it also highlights the need and excitement for continued exploration and refinement in elucidating the underlying molecular mechanisms involved to optimize the development of cell-free and readily available nerve grafts to effectively reconstruct nerve injuries in a consistent manner.

Funding

This research was supported by the American Foundation for Surgery of the Hand (Award 3968), NIH/NIGMS (P30GM122732), NIH/NIAMS (R61/R33 AR076807), and NIH/NIA (1R01AG080141).

Author contributions

Methodology: N.Y.L., B.V., E.R., J.G., Z.Q., and Q.C.; Investigation: N.Y.L., B.V., E.R., J.G., Z.Q., J.D.,; Formal analysis: N.Y.L., J.G.; Writing - original draft: N.Y.L.; Funding acquisition: N.Y.L. and Q.C.; Validation: N.Y.L., B.V., E.R., J.G., J.K., A.M.; Visualization: N.Y.L., B.V., J.G., A.M., and Q.C.; Conceptualization: N.Y.L., B.V., and Q.C.; Supervision, Writing - review & editing: N.Y.L. and Q.C.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All the animal experimental procedures were approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Rhode Island Hospital, RI, USA.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The authors can confirm that all relevant data are included in this article.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the AFSH and NIH. We thank the staff at the Brown University Health animal facility.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UC |

Untreated Conduit |

| TC |

Treated Conduit |

| RA |

Reverse Autograft |

| UN |

Uninjured Nerve |

| SCs |

Schwann cells |

| CMAP |

Compound Muscle Action Potential |

| MATN2 |

Matrilin-2 |

References

- Li, N.Y.; Onor, G.I.; Lemme, N.J.; Gil, J.A. Epidemiology of Peripheral Nerve Injuries in Sports, Exercise, and Recreation in the United States, 2009 – 2018. Physician Sportsmed. 2021, 49, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NINDS. Peripheral Neuropathy Fact Sheet. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

- Taylor, C.A.; Braza, D.; Rice, J.B.; Dillingham, T. The Incidence of Peripheral Nerve Injury in Extremity Trauma. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2008, 87, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinsell, D.; Keating, C.P. Peripheral Nerve Reconstruction after Injury: A Review of Clinical and Experimental Therapies. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijs, A.C.J.; Jaquet, J.-B.; Kalmijn, S.; Giele, H.; Hovius, S.E.R. Median and Ulnar Nerve Injuries: A Meta-Analysis of Predictors of Motor and Sensory Recovery after Modern Microsurgical Nerve Repair. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2005, 116, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.M.; Kasukurthi, R.; Magill, C.K.; Farhadi, H.F.; Borschel, G.H.; Mackinnon, S.E. Limitations of Conduits in Peripheral Nerve Repairs. HAND 2009, 4, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, E.L.; Tuffaha, S.H.; Luciano, J.P.; Yan, Y.; Hunter, D.A.; Magill, C.K.; Moore, A.M.; Tong, A.Y.; Mackinnon, S.E.; Borschel, G.H. Processed allografts and type I collagen conduits for repair of peripheral nerve gaps. Muscle Nerve 2009, 39, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Whiteman, D.R.; Voigt, C.; Miller, M.C.; Kim, H. No Difference in Outcomes Detected Between Decellular Nerve Allograft and Cable Autograft in Rat Sciatic Nerve Defects. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2019, 101, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piecha, D.; Wiberg, C.; Mörgelin, M.; Reinhardt, D.P.; Deák, F.; Maurer, P.; Paulsson, M. Matrilin-2 interacts with itself and with other extracellular matrix proteins. Biochem. J. 2002, 367, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, I.; Évakorpos; Deák, F. Matrilin-2, an extracellular adaptor protein, is needed for the regeneration of muscle, nerve and other tissues. Neural Regen. Res. 2015, 10, 866–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malin, D.; Sonnenberg-Riethmacher, E.; Guseva, D.; Wagener, R.; Aszódi, A.; Irintchev, A.; Riethmacher, D. The extracellular-matrix protein matrilin 2 participates in peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gong, J.; Yang, L.; Niu, C.; Ni, X.; Wang, Y.; Peng, S.; Gu, X.; Sun, C.; et al. Chitosan degradation products facilitate peripheral nerve regeneration by improving macrophage-constructed microenvironments. Biomaterials 2017, 134, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qulub, F.; Widiyanti, P.; Maulida, H.N.; Indrio, L.W.; Wijayanti, T.R. EFFECT OF DEACETYLATION DEGREES VARIATION ON CHITOSAN NERVE CONDUIT FOR PERIPHERAL NERVE REGENERATION. Folia Medica Indones. 2017, 53, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubrech, F.; Sauerbier, M.; Moll, W.; Seegmüller, J.; Heider, S.; Harhaus, L.; Bickert, B.; Kneser, U.; Kremer, T. Enhancing the Outcome of Traumatic Sensory Nerve Lesions of the Hand by Additional Use of a Chitosan Nerve Tube in Primary Nerve Repair: A Randomized Controlled Bicentric Trial. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 142, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.Y.; Vorrius, B.; Ge, J.; Qiao, Z.; Zhu, S.; Katarincic, J.; Chen, Q. Matrilin-2 within a three-dimensional lysine-modified chitosan porous scaffold enhances Schwann cell migration and axonal outgrowth for peripheral nerve regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, K.R.; Mirsky, R.; Lloyd, A.C. Schwann Cells: Development and Role in Nerve Repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a020487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Führmann, T.; Hillen, L.M.; Montzka, K.; Wöltje, M.; Brook, G.A. Cell–Cell interactions of human neural progenitor-derived astrocytes within a microstructured 3D-scaffold. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 7705–7715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Peng, J. The role of peripheral nerve ECM components in the tissue engineering nerve construction. Prog. Neurobiol. 2013, 24, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charras, G.; Sahai, E. Physical influences of the extracellular environment on cell migration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.H.; Burrell, J.C.; Browne, K.D.; Katiyar, K.S.; Ezra, M.I.; Dutton, J.L.; Morand, J.P.; Struzyna, L.A.; Laimo, F.A.; Chen, H.I.; et al. Tissue-engineered grafts exploit axon-facilitated axon regeneration and pathway protection to enable recovery after 5-cm nerve defects in pigs. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Jiang, X.; Cai, M.; Zhao, W.; Ye, D.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Z. A novel electrospun nerve conduit enhanced by carbon nanotubes for peripheral nerve regeneration. Nanotechnology 2014, 25, 165102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenard, V.; Kleitman, N.; Morrissey, T.; Bunge, R.; Aebischer, P. Syngeneic Schwann cells derived from adult nerves seeded in semipermeable guidance channels enhance peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Neurosci. 1992, 12, 3310–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Peng, J.; Guo, Y.; Javidiparsijani, S.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Luo, J. Matrilin-2 Is a Widely Distributed Extracellular Matrix Protein and a Potential Biomarker in the Early Stage of Osteoarthritis in Articular Cartilage. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.K.; Watson, M.A.; Lyman, M.; Perry, A.; Aldape, K.D.; Deák, F.; Gutmann, D.H. Matrilin-2 expression distinguishes clinically relevant subsets of pilocytic astrocytoma. Neurology 2006, 66, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piecha, D.; Muratoglu, S.; Mörgelin, M.; Hauser, N.; Studer, D.; Kiss, I.; Paulsson, M.; Deák, F. Matrilin-2, a Large, Oligomeric Matrix Protein, Is Expressed by a Great Variety of Cells and Forms Fibrillar Networks. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 13353–13361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittier, R.; Sauthier, F.; Hubbell, J.A.; Hall, H. Neurite extension andin vitro myelination within three-dimensional modified fibrin matrices. J. Neurobiol. 2005, 63, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidinia-Anarkoli, A.; Ephraim, J.W.; Rimal, R.; De Laporte, L. Hierarchical fibrous guiding cues at different scales influence linear neurite extension. Acta Biomater. 2020, 113, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholap, A.D.; Rojekar, S.; Kapare, H.S.; Vishwakarma, N.; Raikwar, S.; Garkal, A.; Mehta, T.A.; Jadhav, H.; Prajapati, M.K.; Annapure, U. Chitosan scaffolds: Expanding horizons in biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 323, 121394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenawy, E.-R.; Worley, S.D.; Broughton, R. The Chemistry and Applications of Antimicrobial Polymers: A State-of-the-Art Review. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 1359–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. , A.; K., V.; M., S.; T., G.; K., R.; P.N., S.; Sukumaran, A. Removal of toxic heavy metal lead (II) using chitosan oligosaccharide-graft-maleic anhydride/polyvinyl alcohol/silk fibroin composite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 1469–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Peng, J.; Han, G.-H.; Ding, X.; Wei, S.; Gao, G.; Huang, K. Role of macrophages in peripheral nerve injury and repair. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.J.; Wynn, T.A. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Ao, Q.; Gong, K.; Wang, A.; Zheng, L.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, X. The effect of topology of chitosan biomaterials on the differentiation and proliferation of neural stem cells. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 3630–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietzmeyer, N.; Förthmann, M.; Leonhard, J.; Helmecke, O.; Brandenberger, C.; Freier, T.; Haastert-Talini, K. Two-Chambered Chitosan Nerve Guides With Increased Bendability Support Recovery of Skilled Forelimb Reaching Similar to Autologous Nerve Grafts in the Rat 10 mm Median Nerve Injury and Repair Model. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Shrestha, B.K.; Kim, J.I.; Ko, S.W.; Park, C.H.; Kim, C.S. Electrodeless coating polypyrrole on chitosan grafted polyurethane with functionalized multiwall carbon nanotubes electrospun scaffold for nerve tissue engineering. Carbon 2018, 136, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Chen, F.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J. Multifunctional Double-Layer Composite Hydrogel Conduit Based on Chitosan for Peripheral Nerve Repairing. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2022, 11, e2200115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosio, A.; Fornasari, B.E.; Gambarotta, G.; Geuna, S.; Raimondo, S.; Battiston, B.; Tos, P.; Ronchi, G. Chitosan tubes enriched with fresh skeletal muscle fibers for delayed repair of peripheral nerve defects. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, Q.; Fung, C.-K.; Tsui, A.Y.-P.; Cai, S.; Zuo, H.-C.; Chan, Y.-S.; Shum, D.K.-Y. The regeneration of transected sciatic nerves of adult rats using chitosan nerve conduits seeded with bone marrow stromal cell-derived Schwann cells. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Mi, R.; Hoke, A.; Chew, S.Y. Nanofibrous nerve conduit-enhanced peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2014, 8, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.-Z.; Wang, Y.; Aibaidoula, G.; Chen, G.-Q.; Wu, Q. Evaluation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, M.V.L.; de Faria, J.C.M.; Isaac, C.; Nepomuceno, A.C.; Teixeira, N.H.; Gemperli, R. Comparisons of the results of peripheral nerve defect repair with fibrin conduit and autologous nerve graft: An experimental study in rats. Microsurgery 2015, 36, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.W.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.H.; Jang, J.W.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, S.H. Decellularized sciatic nerve matrix as a biodegradable conduit for peripheral nerve regeneration. Neural Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 1796–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, H.T.; Senden, J.M.G.; Gijsen, A.P.; Kempa, S.; van Loon, L.J.C.; Spuler, S. Muscle Atrophy Due to Nerve Damage Is Accompanied by Elevated Myofibrillar Protein Synthesis Rates. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, H.-S.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, J.-W.; Kim, H.-S.; Shin, U.S.; Knowles, J.C.; Kim, H.-W.; Hyun, J.K. Carbon-nanotube-interfaced glass fiber scaffold for regeneration of transected sciatic nerve. Acta Biomater. 2015, 13, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Walking Force of Experimental Left Hindlimb as Proportion of Normal Right Hindlimb. Measurements taken preoperatively and every 2 weeks postoperatively for 12 weeks. RA: Reverse Autograft, TC: Treated Conduit, UC: Untreated Conduit. *P≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P≤ 0.001.

Figure 1.

Walking Force of Experimental Left Hindlimb as Proportion of Normal Right Hindlimb. Measurements taken preoperatively and every 2 weeks postoperatively for 12 weeks. RA: Reverse Autograft, TC: Treated Conduit, UC: Untreated Conduit. *P≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P≤ 0.001.

Figure 2.

Compound Muscle Action Potential was recorded for the experimental left hindlimb and control right hindlimb for each rat and normalized as a proportion of recovery for each rat. UC: Untreated conduit, TC: Treated Conduit, RA: Reverse Autograft. *P≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01.

Figure 2.

Compound Muscle Action Potential was recorded for the experimental left hindlimb and control right hindlimb for each rat and normalized as a proportion of recovery for each rat. UC: Untreated conduit, TC: Treated Conduit, RA: Reverse Autograft. *P≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01.

Figure 3.

Muscle weights of tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius from experimental left hindlimb normalized to right hindlimb to generate proportion of recovered muscle mass after 12 weeks. UC: Untreated conduit, TC: Treated Conduit, RA: Reverse Autograft. *P≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P≤ 0.001, **** P≤ 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Muscle weights of tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius from experimental left hindlimb normalized to right hindlimb to generate proportion of recovered muscle mass after 12 weeks. UC: Untreated conduit, TC: Treated Conduit, RA: Reverse Autograft. *P≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P≤ 0.001, **** P≤ 0.0001.

Figure 4.

Number of regenerated axons of the distal nerve stump following sciatic nerve reconstruction. (A) Cross-sections of toluidine blue stained nerve immediately distal to the conduit or autograft segment of UC, TC, RA, and UN cross-sections. (b) Quantification of mean axon number for each nerve in RC, TA, RA, and UN groups. Scale bar of 100µm. *P≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P≤ 0.001, **** P≤ 0.0001. UC: untreated conduit, TC: treated conduit, RA: reverse autograft, UN: uninjured nerve.

Figure 4.

Number of regenerated axons of the distal nerve stump following sciatic nerve reconstruction. (A) Cross-sections of toluidine blue stained nerve immediately distal to the conduit or autograft segment of UC, TC, RA, and UN cross-sections. (b) Quantification of mean axon number for each nerve in RC, TA, RA, and UN groups. Scale bar of 100µm. *P≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P≤ 0.001, **** P≤ 0.0001. UC: untreated conduit, TC: treated conduit, RA: reverse autograft, UN: uninjured nerve.

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence staining of longitudinal section of the distal extent of reconstructed nerve segment. (a) Green fluorescence represents Schwann cells and blue fluorescence represents DAPI. Scale bar at 500µm. UC: untreated conduit, TC: treated conduit, RA: reverse autograft, UN: uninjured nerve. (b) Quantification of mean DAPI fluorescent for cell number of each nerve at 4x magnification. (c) Measurement of mean particle size of Schwann cell fluorescent signal for each nerve at 10x magnification. Scale bar of 100µm. *P≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P≤ 0.001, **** P≤ 0.0001.

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence staining of longitudinal section of the distal extent of reconstructed nerve segment. (a) Green fluorescence represents Schwann cells and blue fluorescence represents DAPI. Scale bar at 500µm. UC: untreated conduit, TC: treated conduit, RA: reverse autograft, UN: uninjured nerve. (b) Quantification of mean DAPI fluorescent for cell number of each nerve at 4x magnification. (c) Measurement of mean particle size of Schwann cell fluorescent signal for each nerve at 10x magnification. Scale bar of 100µm. *P≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P≤ 0.001, **** P≤ 0.0001.

Figure 6.

Schematic for the development of lysine enhanced chitosan and matrilin-2. (a) Initial preparation of chitosan and lysine. Following crosslinking lysine and chitosan, matrilin-2 was added to create a homogenous gel. (b) The gel was then placed into a collagen conduit, freeze dried, then lyophilized to create a porous matrilin-2/lysine enhanced chitosan scaffold housed in a collagen conduit.

Figure 6.

Schematic for the development of lysine enhanced chitosan and matrilin-2. (a) Initial preparation of chitosan and lysine. Following crosslinking lysine and chitosan, matrilin-2 was added to create a homogenous gel. (b) The gel was then placed into a collagen conduit, freeze dried, then lyophilized to create a porous matrilin-2/lysine enhanced chitosan scaffold housed in a collagen conduit.

Figure 7.

The gait testing unit comprised of the Tekscan pressure sensor mat (black) that was modified to include a tinted Plexiglas tunnel (width 17.0 cm, height 17.0 cm, length 44.7 cm) for the purpose of guiding the rats across the mat and a goal box. .

Figure 7.

The gait testing unit comprised of the Tekscan pressure sensor mat (black) that was modified to include a tinted Plexiglas tunnel (width 17.0 cm, height 17.0 cm, length 44.7 cm) for the purpose of guiding the rats across the mat and a goal box. .

Figure 8.

Rat Sciatic Nerve Reconstruction. (a) Overview of localization for sciatic nerve reconstruction, (b) exposure of the left hindlimb sciatic nerve at the level of the femur. (c) Implantation of conduit within the sciatic nerve following resection.

Figure 8.

Rat Sciatic Nerve Reconstruction. (a) Overview of localization for sciatic nerve reconstruction, (b) exposure of the left hindlimb sciatic nerve at the level of the femur. (c) Implantation of conduit within the sciatic nerve following resection.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).