1. Introduction

Aging is a complex process that affects the function of various tissues, leading to a health decline and an increased susceptibility to disease [

1]. Typical manifestations include the loss of muscle fiber quality (volume and quantity), strength, endurance and metabolic capacity [

2]. Sarcopenia is the age-related progressive loss of muscle mass and strength and can lead to fractures [

3], but despite intense studies, its specific mechanism and pathophysiology have not been fully elucidated [

4].

Muscle stem cells (MuSCs) are located at the periphery of muscle fibers, between the sarcolemma and the basal lamina, also known as Satellite Cells [

5]. MuSCs are crucial for skeletal muscle regeneration [

6]. After an injury, they exit their quiescent state and proliferate into myogenic progenitor cells, thus generating new muscle fibers and replacing damaged tissue [

7,

8]. In young individuals, MuSCs are abundant and able to rapidly respond to injuries and promote muscle recovery. In the elderly, however, MuSCs population may be up to 30% lower, with a concomitant decline in muscle function and repair capacity, and an increased risk of sarcopenia. The reduction of MuSCs numbers in the elderly muscle is associated with what is known as “inflammageing”, a chronic inflammatory state where stress pathways, such as the focal adhesion kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), are activated [

9]. This activation may suppress MuSCs proliferation and differentiation capability, possibly due to a change in the local microenvironment [

10].

Fibronectin (FN) is an extracellular glycoprotein that can bind to cells [

11] via, for example, laminin and integrin-α7β1, the primary integrin binding type in skeletal muscle [

12]. An increase in integrin-α7β1 can enhance the migration of MuSCs to the site of injury [

13]. In fact, FN is crucial for muscle stem cell function and maintenance, and for immune regulation and repair of skeletal muscle injury. However, due to its large molecular weight, the expression of full-length recombinant FN is challenging. FN is usually obtained after extraction from plasma, or from segmental recombinant expression, but these methods are resource-intensive and carry safety risks.

The optimal functional domain for recombinant expression can be selected using molecular dynamics simulations (MDs). Herein, we have identified a domain in FN that binds integrin-α7β1. The rhFN-NM (recombinant human Fibronectin N-Terminal Module) can enhance the adhesion and vitality of aging cells and can also regulate the microenvironment of skeletal muscle in aging mice, facilitating the repair and regeneration of damaged tissues.

2. Results

2.1. Integrin and Fibronectin Structures and Analysis of Binding Modes

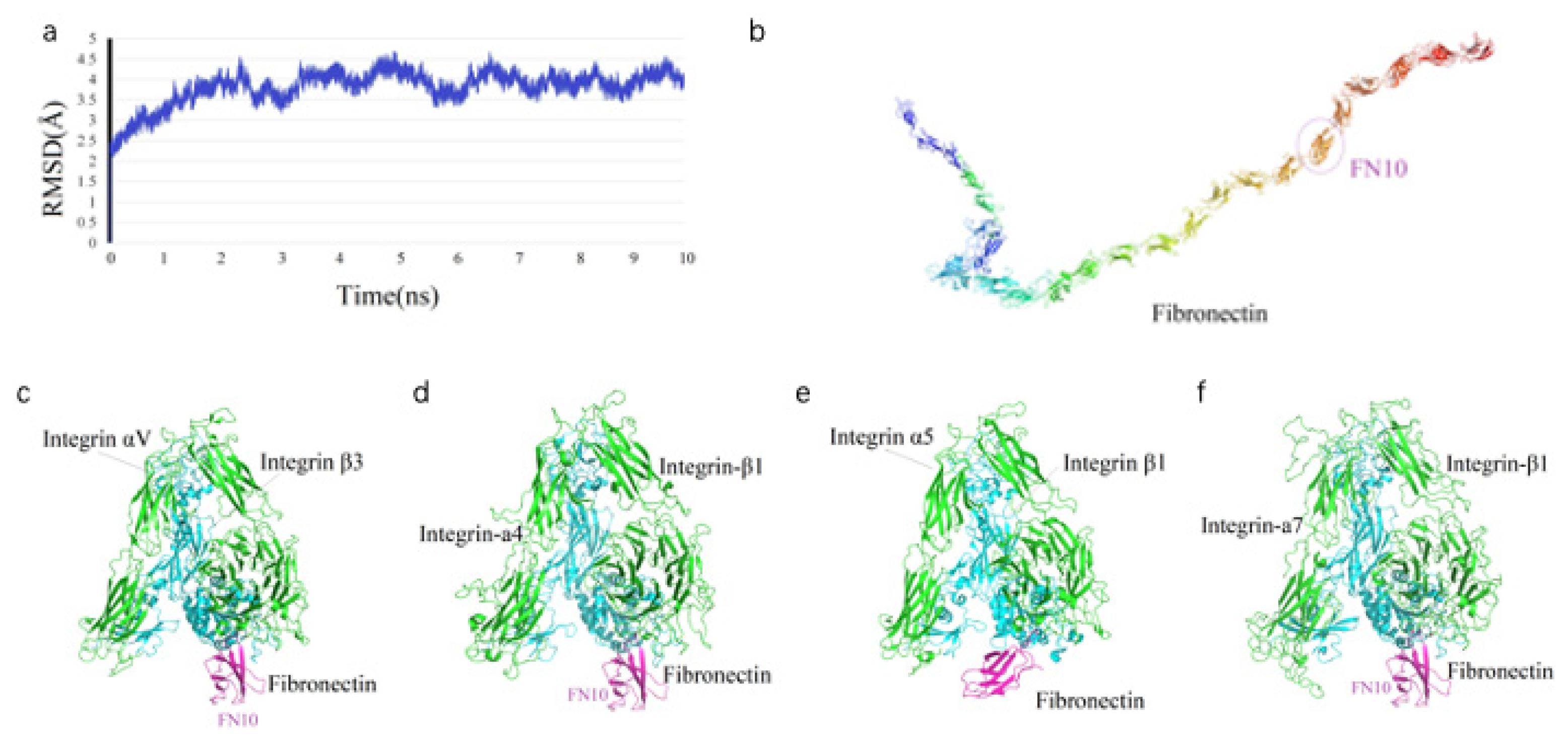

The temporal variation of the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) for full-length Fibronectin (

Figure 1a) indicates that the system achieved stability after 4 ns, reaching an equilibrium state with an average RMSD of 4.03, 2.76, 2.78 and 3.57 Å, respectively. The average structure of Fibronectin (FN) is characterized by a V-shaped extended chain comprising 25 tandem β-sheet repeats (FN1–FN25) (

Figure 1b), with the FN6 module positioned at the junction of two linear segments formed by FN1–FN5 and FN7–FN25. The crystal structure of the integrin ectodomain αV/β3 heterodimer in complex with FN10 (PDB: 4MMX) (

Figure 1c), along with complexes involving other ectodomains (

Figure 1d–f), exhibits a high degree of conservation at the interaction interfaces.

Figure 1.

Molecular Dynamics profiles and Fibronectin-Integrin Interactions. (a) Temporal evolution of RMSD values (y-axis, in Å) for full-length FN backbone atoms over a 10 ns simulation (x-axis, in ns); (b) structural representation of full-length FN, highlighting its domain organization; (c–f) modeled structures of the FN10 domain on FN in complex with various integrin heterodimers: (c) αVβ3, (d) α4β1, (e) α5β1, and (f) α7β1, illustrating the binding conformations.

Figure 1.

Molecular Dynamics profiles and Fibronectin-Integrin Interactions. (a) Temporal evolution of RMSD values (y-axis, in Å) for full-length FN backbone atoms over a 10 ns simulation (x-axis, in ns); (b) structural representation of full-length FN, highlighting its domain organization; (c–f) modeled structures of the FN10 domain on FN in complex with various integrin heterodimers: (c) αVβ3, (d) α4β1, (e) α5β1, and (f) α7β1, illustrating the binding conformations.

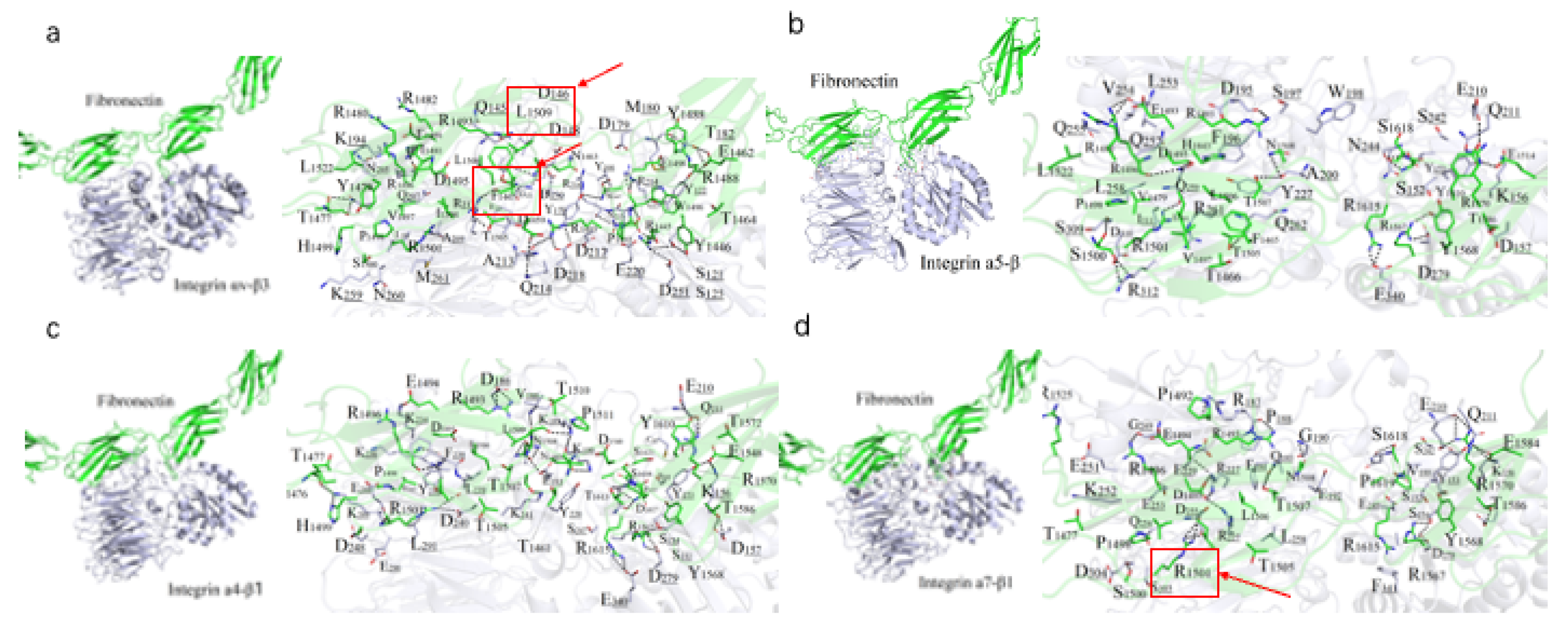

A 10 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was performed to refine the binding models of FN with four integrin subtypes (α4-β1, α5-β1, αv-β3, and α7-β1). The binding interfaces primarily involve the FN10 region, with specific interaction regions spanning residues 1459–1624 across the four complexes (

Figure 2). The binding regions for each integrin subtype are as follows: α7-β1 (residues 1477–1620), αv-β3 (1459–1621), α4-β1 (1461–1624), and α5-β1 (1465–1620).

Polar interactions, particularly salt bridges and hydrogen bonds, dominate the stabilization of these complexes through nonbonded electrostatic interactions. A robust polar interaction network was observed at the binding interfaces, with FN residue R1501 forming critical hydrogen bonds with all four integrin subtypes. Common FN regions (R1493–N1508, R1567–R1570, V1582–T1586, and Y1610–S1621) contribute to both hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions across all complexes. Specifically, the α7-β1/FN complex involves 29 residues from integrin and 39 from FN, forming an extensive interaction network.

Hydrophobic interactions also play a significant role in stabilizing the complexes. Notably, the benzene ring of F1465 and L1509 from all integrin subtypes forms hydrophobic contacts with V188 of FN, enhancing binding stability (

Figure 2). The binding energies, calculated as -111.33 kcal/mol (α4-β1), -102.34 kcal/mol (α5-β1), -102.09 kcal/mol (αv-β3), and -95.27 kcal/mol (α7-β1), reflect the varying strengths of these interactions, with α4-β1 exhibiting the strongest binding, likely due to its extended binding region and enhanced polar interactions. Overall, the interplay of strong salt-bridge-mediated polar interactions and hydrophobic contacts at the binding interface is pivotal to the stability of FN-integrin complexes.

Figure 2.

Binding mode predicted between FN and the integrin isoforms. (a-d) Potential binding interface between FN (green) and αVβ3 (a), α4β1 (b), α5β1 (c) and α7β1 (d), colored in purple. Residues participating in the interaction (sticks) and hydrogen bonds (dashes) are indicated on the right.

Figure 2.

Binding mode predicted between FN and the integrin isoforms. (a-d) Potential binding interface between FN (green) and αVβ3 (a), α4β1 (b), α5β1 (c) and α7β1 (d), colored in purple. Residues participating in the interaction (sticks) and hydrogen bonds (dashes) are indicated on the right.

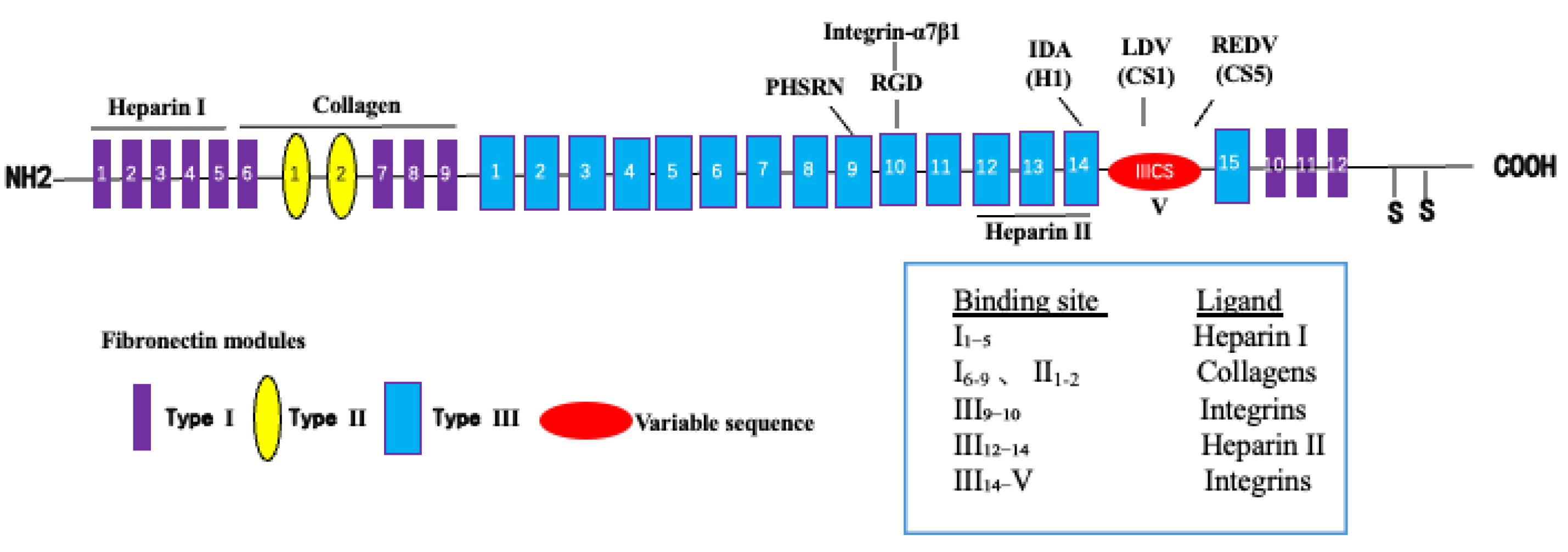

2.2. Recombinant Fibronectin Construction and Integrin Binding Interactions

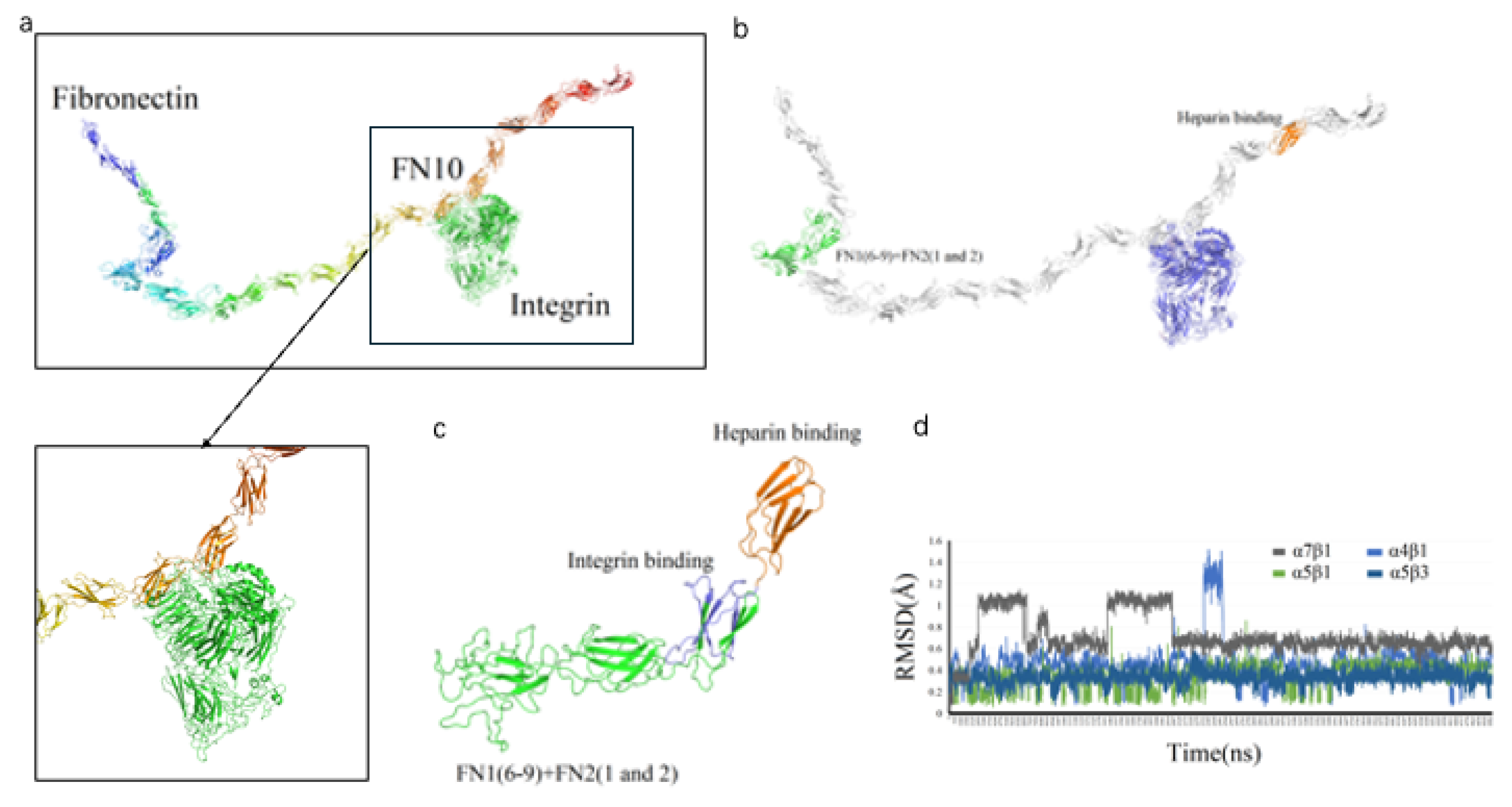

We designed a novel recombinant protein (rhFN-NM) by fusing the collagen-binding domain (FN1(6-9) + FN2(1-2)) and heparin-binding domain of fibronectin (FN) (

Figure 3). Structural alignment confirmed that the local conformations of these functional domains in rhFN-NM remained nearly identical to their native counterparts in full-length FN (RMSD < 1.0 Å). However, the overall architecture of rhFN-NM exhibited significant divergence from native FN, primarily due to the engineered integrin-binding linker region. This linker adopted a novel spatial arrangement, altering the relative positioning between the collagen- and heparin-binding domains (

Figure 4). To investigate the functional implications of these structural changes, molecular dynamics simulations were performed, revealing distinct interaction patterns between rhFN-NM and integrin receptors. The dominant binding modes extracted from trajectory clusters (see Methods) were further analyzed to elucidate the mechanistic basis of the modified interactions.

Figure 3.

Simplified Fibronectin structure.

Figure 3.

Simplified Fibronectin structure.

Figure 4.

De novo modeling of rhFN-NM. (a) Structure of Fibronectin; (b) recombined FN protein; (c) 3D diagram of modeling rhFN-NM. The structure of FN1(6-9) + FN2(1 and 2) and Heparin region were colored as green and orange, respectively; (d) RMSD values (y-axis) versus time (x-axis) for four integrin subtypes (αVβ3, α4β1, α5β1, α7β1) with rhFN-NM.

Figure 4.

De novo modeling of rhFN-NM. (a) Structure of Fibronectin; (b) recombined FN protein; (c) 3D diagram of modeling rhFN-NM. The structure of FN1(6-9) + FN2(1 and 2) and Heparin region were colored as green and orange, respectively; (d) RMSD values (y-axis) versus time (x-axis) for four integrin subtypes (αVβ3, α4β1, α5β1, α7β1) with rhFN-NM.

The RMSD change curves of four Integrin subtypes (αVβ3, α4β1, α5β1, α7β1) with the recombinant Fibronectin-derived protein rhFN-NM complex. The calculated maximum RMSD fluctuation value for each complex was under 1.6 Å, all reaching equilibrium after 5 ns (

Figure 4d)—a demonstration of structural stability in the binding systems—with each average structure further used for subsequent analysis.

rhFN-NM showed weaker binding to the four integrins αVβ3, α4β1, α5β1 and α7β1 (-85.29, -89.77, -82.14 and -98.06 kcal/mol, respectively) than full length FN. For the αVβ3/rhFN-NM complex, 35 and 45 residues participated in the interaction (

Figure 5a), consistent with the low binding energy observed. The lowest binding affinity was for the complex involving α5β1, with 23 and 37 residues from the integrin and rhFN-NM, respectively (

Figure 5b). For αVβ3 and α4β1 complexes, 30 and 37 residues, respectively, participated with 39 residues on rhFN-NM (

Figure 5a/c). Thus it could be inferred that rhFN-NM protein binds with different integrin isoforms with a similar binding region (Y204-Q345).

Figure 5.

Binding mode prediction between different integrin isoforms and rhFN-NM. a-d. Potential binding interface between rhFN-NM (green) and αVβ3 (a), α5β1 (b), α4β1 (c) and α7β1 (d) (purple). Residues participating in the binding interface (sticks) and hydrogen bonds (dashes) are indicated (right panels).

Figure 5.

Binding mode prediction between different integrin isoforms and rhFN-NM. a-d. Potential binding interface between rhFN-NM (green) and αVβ3 (a), α5β1 (b), α4β1 (c) and α7β1 (d) (purple). Residues participating in the binding interface (sticks) and hydrogen bonds (dashes) are indicated (right panels).

2.3. rhFN-NM Protein Mitigates Oxidative Stress-Induced Cellular Damage

Oxidative stress causes cell dysfunction, DNA damage and ultimately, irreversible injury and death due to an imbalance between oxidant and antioxidant mechanisms. FN can affect cell proliferation, differentiation and vitality through various mechanisms. These include remodeling of the extracellular matrix, enhanced inflammation, and alterations in mitochondrial function.

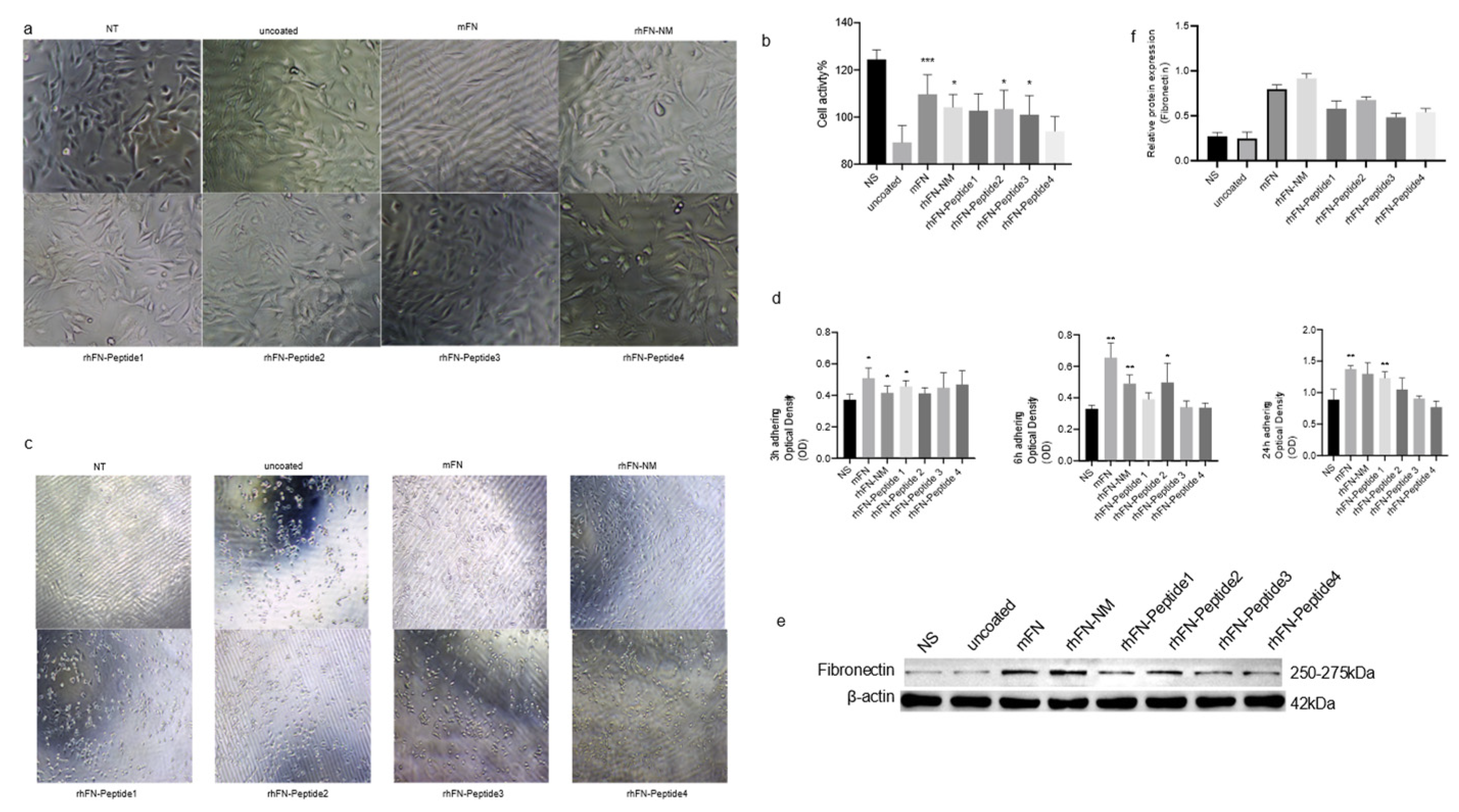

We tested the effect of rhFN-NM, mFN (Native Mouse Fibronectin, Abcam) and other peptides on the proliferation and anti-aging capability of C2C12 cells. To evaluate anti-aging effects, plates were pre-coated with the different constructs, seeding 10

5 cells, and culturing them for 24 h. Oxidative stress damage was induced with 400 µM H

2O

2. Morphological changes and viability were assessed using the CCK-8 assay. After 24 h of culture on the pre-coated plates, no significant differences were observed with respect to the control in the treatment groups, except in the rhFN-Peptide4 group, where a slightly lower cell count was observed (

Figure 5a). Following oxidative stress treatment, all groups experienced morphological changes. The rhFN peptide groups (rhFN-Peptide1-4) showed varying degrees of cell shrinkage and detachment, whereas the rhFN-NM and mFN groups were the least affected (

Figure 5b). The cell viability in the latter two groups was also confirmed by CCK-8 results (

Figure 5d).

To further demonstrate the effect of FN on cell function, we used the CCK-8 assay to measure the OD values of adherent cells after 3, 6 and 24 h after seeding (

Figure 5d), which measured the adhesion of the constructs tested. After 3h, strong adhesion was evident for rhFN-NM, mFN protein, and rhFN-Peptide1, with a significant difference in adhesion observed at 24 h. In contrast, poor adhesion was observed for rhFN-Peptide3 and rhFN-Peptide4. The expression levels of FN in the treated cells were elevated for all constructs, especially for rhFN-NM and mFN protein (

Figure 5e,f). This suggests that the treatments may have an impact on the extracellular matrix and the observed protective effects against oxidative stress.

In summary, the results indicate that rhFN-NM and mFN may have beneficial effects on C2C12 cells, promoting better tolerance to oxidative stress and potentially enhancing their anti-aging potential compared to the peptide controls. The increased expression of Fibronectin in these treated groups suggests that changes in the extracellular matrix may be involved in the observed protective effects. Further research is necessary to fully understand the mechanisms underlying these observations.

Figure 6.

(a) Effects of proteins and peptides on the proliferation of C2C12 myoblasts (100 μm); (b) The histogram represents the percentage of cell viability after injury in each group; (c) Cell morphology and cell viability after oxidative stress injury; (d) Cell adhesion. e-f. Effects of rhFN-NM protein and rhFN-Peptide on Fibronectin expression. Note: Coated groups: rhFN-NM, mFN, rhFN-Peptide1, rhFN-Peptide2, rhFN-Peptide3, rhFN-Peptide4; Untreated group: NT; Each experiment was set with 5 replicates, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.001.

Figure 6.

(a) Effects of proteins and peptides on the proliferation of C2C12 myoblasts (100 μm); (b) The histogram represents the percentage of cell viability after injury in each group; (c) Cell morphology and cell viability after oxidative stress injury; (d) Cell adhesion. e-f. Effects of rhFN-NM protein and rhFN-Peptide on Fibronectin expression. Note: Coated groups: rhFN-NM, mFN, rhFN-Peptide1, rhFN-Peptide2, rhFN-Peptide3, rhFN-Peptide4; Untreated group: NT; Each experiment was set with 5 replicates, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.001.

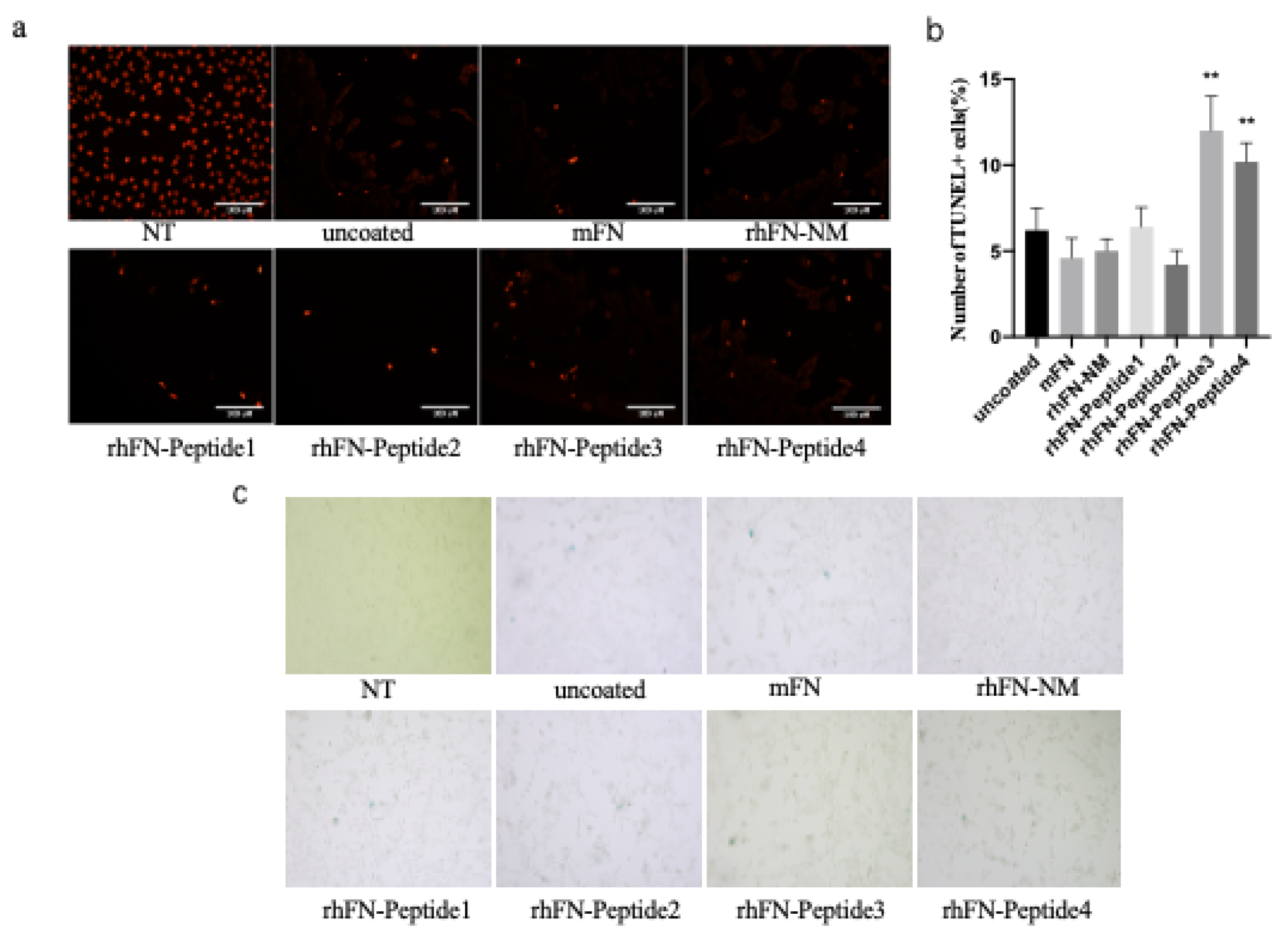

2.4. rhFN-NM Protein Inhibits Cellular Senescence and Apoptosis

To detect and stain senescent cells we used the β-galactosidase staining method, based on the upregulation of senescence-associated β-Gal (SA-β-Gal) activity. After oxidative stress damage to the pre-coated cells, the cells were fixed and stained for β-galactosidase activity, followed by blue cell colonies counting under the microscope to assess the aging status of each group. rhFN-NM, mFN, rhFN-Peptide1, and rhFN-Peptide2 groups had a lower positive rate.

To confirm the inhibitory effect of the constructs on apoptosis, apoptosis rates were measured using the TUNEL assay. Positive rates of apoptotic cells were lower in the rhFN-NM, mFN, rhFN-Peptide1 and rhFN-Peptide2 groups than in the uncoated control group (

Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Cell apoptosis detection by TUNEL labeling. (c) β-galactosidase staining for cell senescence. Note: Coated groups: rhFN-NM, mFN, rhFN-Peptide1, rhFN-Peptide2, rhFN-Peptide3, rhFN-Peptide4; Uncoated group: uncoated; pos is the positive control treated with DnaseI, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.001, scale bar 100 μm.

Figure 7.

Cell apoptosis detection by TUNEL labeling. (c) β-galactosidase staining for cell senescence. Note: Coated groups: rhFN-NM, mFN, rhFN-Peptide1, rhFN-Peptide2, rhFN-Peptide3, rhFN-Peptide4; Uncoated group: uncoated; pos is the positive control treated with DnaseI, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.001, scale bar 100 μm.

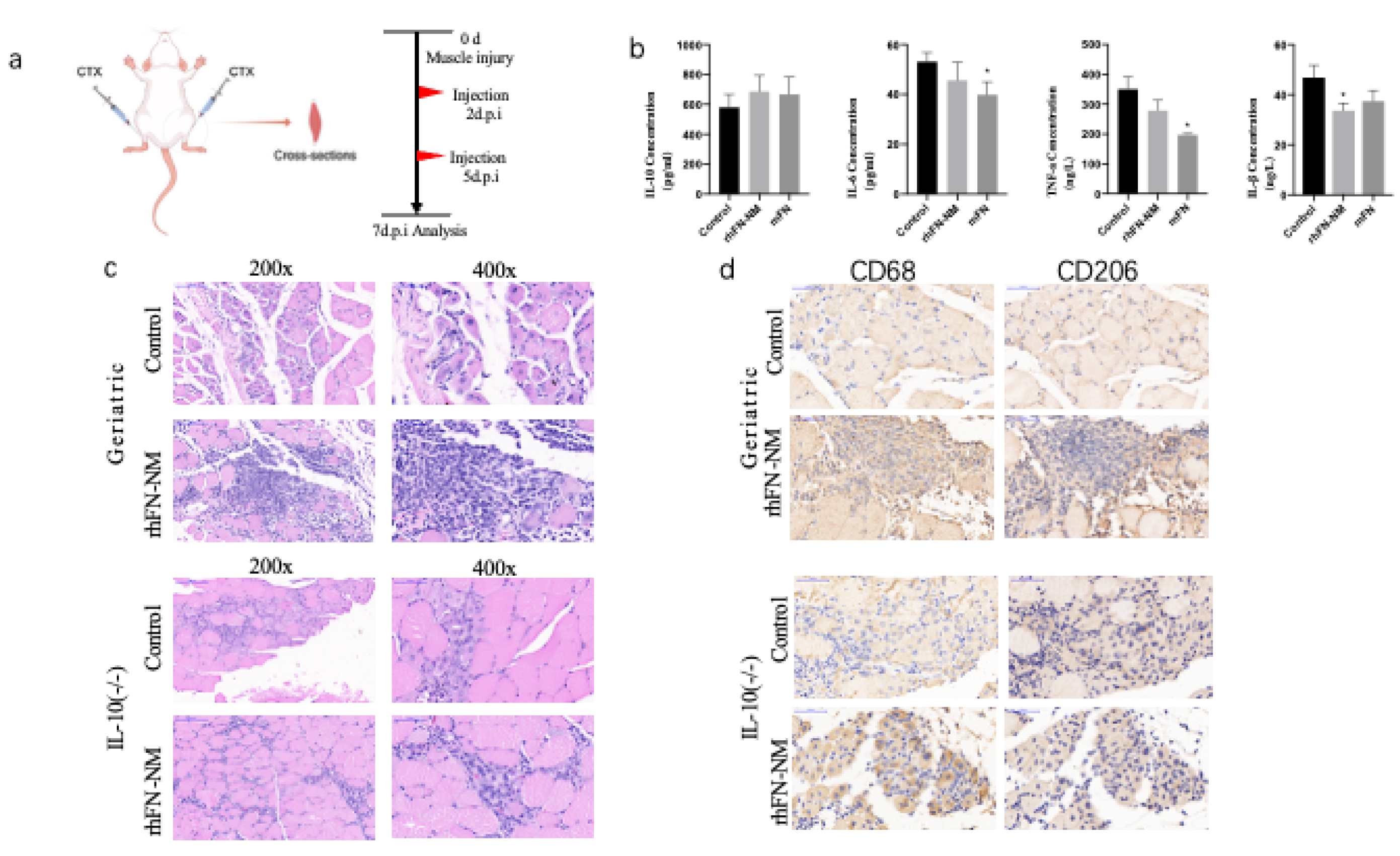

2.5. rhFN-NM: Regulating Mouse Skeletal Muscle Microenvironment

The skeletal muscle microenvironment consists of extracellular matrix (ECM), cytokines, growth factors and immune cells, among others. These components regulate the muscle stem cell (MuSC) behavior essential for muscle regeneration and repair.

We measured the levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-10) in the serum samples from Geriatric mice following CTX muscle injury using ELISA. In the rhFN-NM group, reduction was observed for pro-inflammatory IL-6 and TNF-α, but anti-inflammatory IL-10 increased. In the mFN group, the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β were reduced, while the concentration of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 increased (

Table 1). However, both groups showed similar patterns of change. Treatment with rhFN-NM or mFN produced an increase in IL-10 levels that was not significant (45% higher and 61% higher than control, respectively), suggesting that enhanced anti-inflammatory response may partially contribute to repair, albeit requiring further validation.

Table 1.

Inflammatory Cytokine Levels.

Table 1.

Inflammatory Cytokine Levels.

| Cytokine |

Group |

Control (Mean) |

Treatment (Mean) |

Change |

P-value |

| IL-1β |

rhFN-NM |

46.84 |

33.61 |

↓ |

0.0169* |

| |

mFN |

46.84 |

37.36 |

↓(NS) |

0.1159 |

| IL-6 |

rhFN-NM |

53.14 |

45.6 |

↓(NS) |

0.1268 |

| |

mFN |

53.14 |

39.82 |

↓ |

0.0196* |

| TNF-α |

rhFN-NM |

350 |

277.9 |

↓(NS) |

0.0886 |

| |

mFN |

350 |

196.9 |

↓ |

0.0167* |

| IL-10 |

rhFN-NM |

412.3 |

597.7 |

↑(NS) |

0.1747 |

| |

mFN |

412.3 |

666 |

↑(NS) |

0.1978 |

The H&E staining of skeletal muscle tissue sections from two groups of mice was analyzed for comparison (

Figure 8). The rhFN-NM subset within the Geriatric group displayed marked infiltration of inflammatory cells at the injury site, accompanied by a significant aggregation of immune cells. Notably, the injury area of the skeletal muscle featured numerous centrally nucleated muscle fibers, a hallmark of muscle fiber regeneration. In the Control group, however, there was only a slight infiltration of inflammatory cells, with a few centrally nucleated muscle fibers observed at the injury site, indicating modest muscle fiber regeneration.

Different types of macrophages play distinct roles in muscle injury repair. M1 macrophages secrete inflammatory factors that inhibit repair, whereas M2 macrophages secrete anti-inflammatory factors that facilitate repair. In the aging state, especially in damaged skeletal muscle, macrophages tend to switch from the M2 to the M1 type. We used macrophage marker CD68 and M2 macrophage marker CD206 for immunohistochemical labeling of skeletal muscle tissue. After skeletal muscle injury, the rhFN-NM group of geriatric mice exhibited significant inflammatory cell infiltration, which was confirmed as macrophages by CD68 labeling. Additionally, a large number of macrophages were labeled as CD206-positive in consecutive sections at the same site, indicating a substantial presence of M2 macrophages at the injury site. These macrophages would produce anti-inflammatory factors that promote repair. The control group showed only minimal cell infiltration, with fewer CD206-labeled cells, and no significant presence of M2 macrophages.

Figure 8.

(a) Treatment scheme in aging mice: after CTX-induced muscle injury, geriatric mice received saline (control), rhFN-NM, or mFN injections at 2 and 5 days post-injury (d.p.i.), with samples collected at 7 d.p.i.; (b) effect of rhFN-NM on inflammatory cytokines; (c) Representative immunohistochemical images of muscle in control and rhFN-NM-treated mice; (d) Immunostaining of muscle macrophages (CD68, CD206) in control and rhFN-NM-treated mice.

Figure 8.

(a) Treatment scheme in aging mice: after CTX-induced muscle injury, geriatric mice received saline (control), rhFN-NM, or mFN injections at 2 and 5 days post-injury (d.p.i.), with samples collected at 7 d.p.i.; (b) effect of rhFN-NM on inflammatory cytokines; (c) Representative immunohistochemical images of muscle in control and rhFN-NM-treated mice; (d) Immunostaining of muscle macrophages (CD68, CD206) in control and rhFN-NM-treated mice.

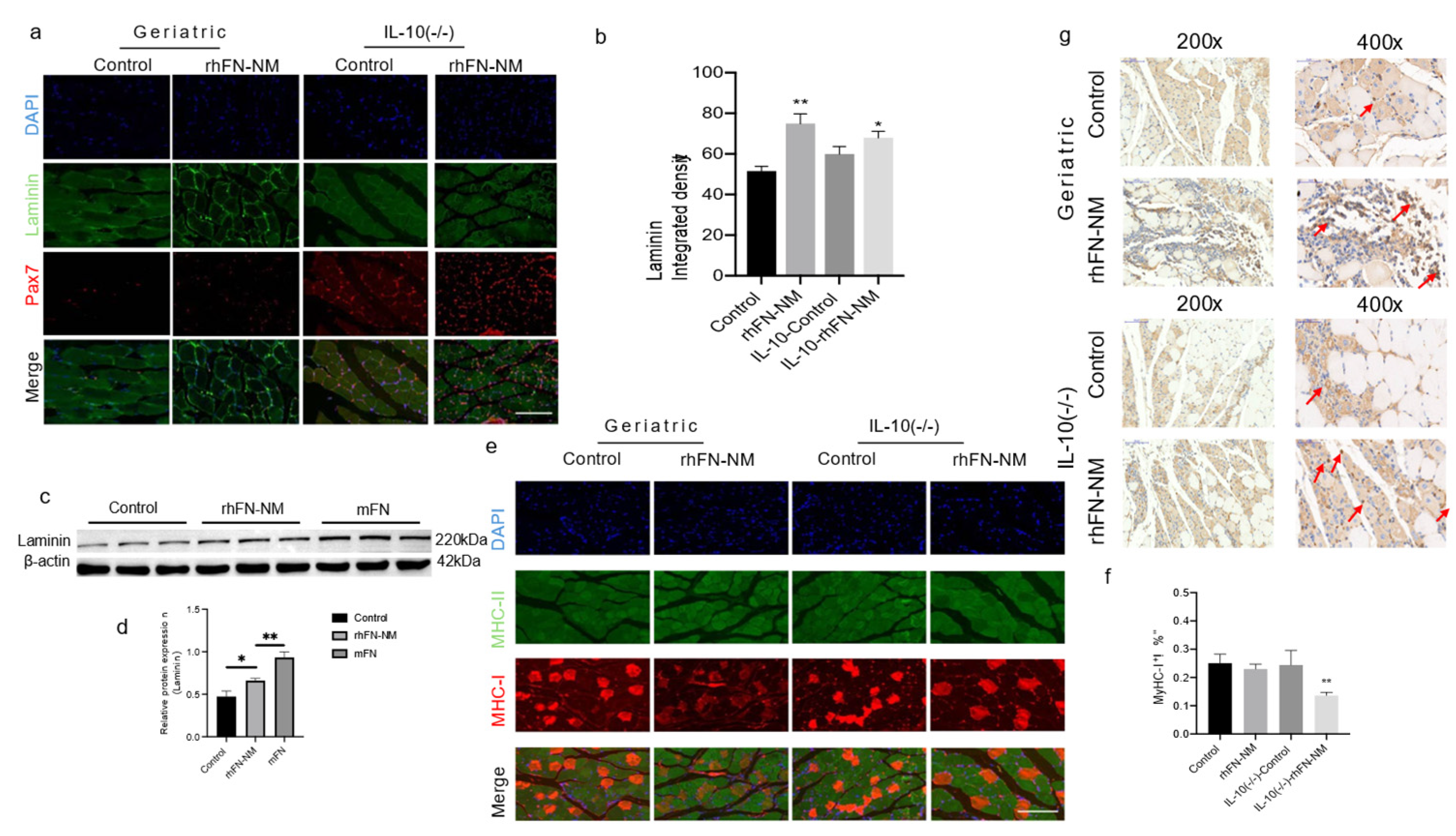

2.6. rhFN-NM Promotes Skeletal Muscle Regeneration

In the context of aging skeletal muscle, expression of Laminin and FN is crucial for the microenvironment and repair of skeletal muscle. We used an immunofluorescence double staining to examine the expression of Laminin and Pax7 in mouse skeletal muscle (

Figure 9). The Pax7 positivity rate in the rhFN-NM group was higher than in the Control group, whereas in the IL-10--rhFN-NM group it was higher than that in the IL-10-Control group. Similarly, in the rhFN-NM group, the average fluorescence intensity of Laminin was higher than in the Control group, whereas, in the IL-10-rhFN-NM group, it was higher than in the IL-10-Control group. Western blot analysis was performed to detect FN and Laminin. In the skeletal muscle of aging mice, laminin expression decreased, but both laminin and FN showed increased expression after treatment with rhFN-NM protein and mFN protein.

Slow muscle type I and fast muscle type II fibers were fluorescently labeled and their composition was analyzed statistically. In the geriatric group, the slow muscle type I fibers and the IL-10(-/-) group treated with rhFN-NM protein were reduced compared to the control. In the geriatric and the IL-10(-/-) mice treated with rhFN-NM, expression of MYH3 embryonic myosin heavy chain was enhanced, suggesting muscle regeneration near the muscle injury site.

Overall, the results suggest that both rhFN-NM and mFN may have potential benefits in promoting muscle repair and regeneration by reducing inflammation and promoting an anti-inflammatory environment. Further research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms by which these proteins exert these effects and to explore their potential therapeutic applications in muscle injury and repair.

Figure 9.

rhFN-NM promotes muscle regeneration and modulates fiber type composition. (a) Immunofluorescence staining of skeletal muscle in geriatric and IL-10(−/−) mice after CTX-induced injury, showing Pax7 (red), Laminin (green), and DAPI (blue). Groups: Control (saline), rhFN-NM, IL-10-Control (saline in IL-10(−/−)), and IL-10-rhFN-NM; (b) Quantified fluorescence intensity (scale bar: 200 μm); (c-d) Western blot of Laminin expression in aging mice: Control (saline), rhFN-NM, and mFN (positive control). Statistical significance: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; (e) Muscle fiber type analysis: Immunofluorescence of MyHC-I (red) and MyHC-II (green) in geriatric and IL-10(−/−) mice. Control (saline) vs. rhFN-NM groups; (f) Western blot of MyHC-I expression in aging mice: Control (saline), rhFN-NM, and mFN (positive control). Statistical significance: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; (g) rhFN-NM enhances MYH3 embryonic myosin expression (200x/400x).

Figure 9.

rhFN-NM promotes muscle regeneration and modulates fiber type composition. (a) Immunofluorescence staining of skeletal muscle in geriatric and IL-10(−/−) mice after CTX-induced injury, showing Pax7 (red), Laminin (green), and DAPI (blue). Groups: Control (saline), rhFN-NM, IL-10-Control (saline in IL-10(−/−)), and IL-10-rhFN-NM; (b) Quantified fluorescence intensity (scale bar: 200 μm); (c-d) Western blot of Laminin expression in aging mice: Control (saline), rhFN-NM, and mFN (positive control). Statistical significance: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; (e) Muscle fiber type analysis: Immunofluorescence of MyHC-I (red) and MyHC-II (green) in geriatric and IL-10(−/−) mice. Control (saline) vs. rhFN-NM groups; (f) Western blot of MyHC-I expression in aging mice: Control (saline), rhFN-NM, and mFN (positive control). Statistical significance: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; (g) rhFN-NM enhances MYH3 embryonic myosin expression (200x/400x).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Construction of Integrin and Fibronectin

Structures of integrin α-chains (α4/α5) and β-chains (β3) were obtained from the PDB database (PDB ID: 4irz/4mmx and 4mmx) [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Structures of α7 and β1 were obtained by homology modeling using template 4mmx with sequence identity of 28.44% and 45.26%, respectively (

Table 1).

The structure of the long sequence of FN was modeled using

de novo and multiple-template approaches by means of homology modeling [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Six regions (residues 48-140, 93-182, 183-275, 298-603, 604-803, 1173-1539 and 1814-2081) were retrieved from PDB structures 109a, 2cg7, 1fbr, 3m7p, 2ha1, 3tlw and 4gh7 (

Table 2). Three crystal structures (3tlw, 1fnf and 4gh7) were selected as homology modeling templates for five FN regions (783-996, 903-1268, 1270-1626, 1542-1887 and 1632-1898) with sequence identity of 27.6, 99.7, 82.1, 33.3, and 31.84%, respectively). No templates were found for regions 1-47, 276-297 and 2081-2446, therefore we used

de novo modeling (

Table 1). Template-based and

de novo FN modeling regions were joined using USC Chimera [

23,

24,

25]. Residues corresponding to the same amino acid sites in overlapping regions were superimposed, followed by the assembly of backbone heavy atoms (C - C(=O) - NH - C) at the junction points, thereby yielding a full-length protein structure.

Table 2.

Structures of integrin.

Table 2.

Structures of integrin.

| Region |

Template |

Sequence identity |

Method |

| Integrin-α7 |

4mmx |

28.44% |

Homology modeling |

| Integrin-β1 |

4mmx |

45.26% |

Homology modeling |

| Integrin-α5 |

4mmx |

100.00% |

Crystal structure |

| Integrin-β1 |

4mmx |

45.26% |

Homology modeling |

| Integrin-α5 |

4mmx |

100.00% |

Crystal structure |

| Integrin-β3 |

4mmx |

100.00% |

Crystal structure |

| Integrin-α4 |

4irz |

100.00% |

Crystal structure |

| Integrin-β1 |

4mmx |

45.26% |

Homology modeling |

Table 3.

Structures of Fibronectin.

Table 3.

Structures of Fibronectin.

| Region |

Template |

Sequence identity |

Method |

| 1-47 |

NO |

NO |

De novo modeling |

| 48-140 |

1o9a |

100% |

Crystal structure |

| 93-182 |

2cg7 |

100% |

Crystal structure |

| 183-275 |

1fbr |

100% |

Crystal structure |

| 276-297 |

NO |

NO |

De novo modeling |

| 298-603 |

3m7p |

100% |

Crystal structure |

| 604-803 |

2ha1 |

100% |

Crystal structure |

| 783-996 |

3t1w |

27.63% |

Homology modeling |

| 903-1268 |

6mfa |

99.73% |

Crystal structure |

| 1173-1539 |

3t1w |

100% |

Crystal structure |

| 1270-1626 |

1fnf |

82.07% |

Homology modeling |

| 1542-1887 |

3t1w |

33.33% |

Homology modeling |

| 1632-1898 |

4gh7 |

31.84% |

Homology modeling |

| 1814-2081 |

1fnh |

100% |

Crystal structure |

| 2081-2446 |

NO |

NO |

De novo modeling |

3.2. Structure Optimization of FN Modeling

MD simulations (10 ns) were performed to eliminate steric clashes. The protein was position-restrained with a force constant k of 100 Kcal/mol

-1Å

-2. Simulations were carried out using AMBER software (version 16) [

26], using the AMBER ff99sb force field for the complex. Hydrogen atoms were added to the initial models using the leap module, setting ionizable residues at their default protonation states at neutral pH. The protein was solvated in a cubic periodic box of explicit TIP3P water that extended a minimum distance of 10 Å from the box surface to any atom of the solute. The particle mesh Ewald (PME) [

27] method for simulation of periodic boundaries was used to estimate the long-range electrostatic interactions, with a cutoff of 10 Å. All bond lengths were constrained using the SHAKE algorithm. Integration time step was set to 2 fs using the Verlet leapfrog algorithm [

28,

29]. To eliminate possible clashes between solute and solvent, the entire system was minimized in two steps. First, the protein was restrained with a harmonic potential (k Δx

2) with k = 100 Kcal/mol

-1Å

-2. Water molecules and counter ions were optimized using the steepest descent method of 2,500 steps, followed by the conjugate gradient method for 2,500 steps. Second, the entire system was optimized using the first step method without any constraint. These two minimization steps were followed by annealing simulation, with a weak restraint (k = 100 Kcal/mol

-1Å

-2) for the complex, and the entire system was heated gradually in the NVT ensemble from 0 to 298K over 500 ps. After the heating phase, a 10 ns MD simulation was performed under 1 atm. A constant temperature of 298 K was selected in the NPT ensemble. The constant temperature was maintained using the Langevin thermostat with a collision frequency of 2 ps

-1. The constant pressure was maintained using an isotropic position scaling algorithm with a relaxation time of 2 ps.

The FN structure stability during the MD simulation was derived from its RMSD deviation from the initial structure [

30]. The RMSD value of all heavy atoms in the entire MD simulation trajectory is shown in

Figure 1a. The FN structures were stable after 3 ns (RMSD of 4 Å). From the MDs trajectory, 3,000 snapshots were extracted from the last 3 ns to obtain the final FN average structure [

19].

3.3. Construction and Optimization of the FN/Integrin Complex

Sequence blasting indicated that one crystal structure is available for integrin αVβ3 ectodomain bound to FN10 (ID: 4MMX) [

14]. To obtain the structural complexes of full length FN with the four integrin ectodomains, the target ectodomain was superimposed on the crystal structure with UCSF Chimera software [

31]. Due to the large size of FN, only domain Fn10 was used. The heavy atoms were not positioned restrained, and 3,000 snapshots were extracted from the last 3 ns to obtain the final average structure of each complex.

3.4. De Novo Modeling of FN-Derived Constructs

We employed the Rosetta protocol [

32] to predict the structures of the FN-derived constructs. The intermediate region (T298 to D353), not associated with any known protein structure, was flanked by sequences at both ends that have known crystal structures. Two additional regions (C1-T197 and S354-S435) have crystal structures and were therefore used for multiple-template modeling.

3.5. Molecular Docking of Integrin Ectodomains to FN-Derived Constructs

To explore the possible binding interface between FN-derived construct and the four ectodomains of integrin we used docking simulations performed with Rosetta software [

32]. In precise docking, the integrin ligands were randomly placed within ~10 Å from the binding regions of receptor FN. Before the start of every simulation, the ligand was perturbed by 3 Å translations and 8° rotations. During precise docking, the side chains at the binding pocket were not allowed to move. A docking pose with the lowest binding energy from a maximum number of 100 conformations was selected. MD simulations (10 ns) were conducted on the selected pose for energy minimization.

3.6. Mice

All animal procedures were approved by the Local Animal Ethics Committee. Female C57BL/6N mice (specific pathogen-free [SPF]) were stratified into three groups: (1) young wild-type (WT) controls (3-4 months; genetically unmodified C57BL/6N background); (2) aged group (26-27-month-old retired breeder mice - defined as mice withdrawn from reproduction programs at 6-7 months and maintained as a validated aging model) and (3) IL-10 knockout (KO) group (5-month-old IL-10-/- mice; C57BL/6N background), used to assess inflammation-accelerated aging phenotypes due to IL-10 deficiency exacerbating chronic inflammation. Mice were obtained from Beijing Weitong Lihua (WT/aged) or Saiye Biotech (IL-10 KO; Guangzhou, China), housed with ad libitum access to food/water. Tibialis anterior muscle injury was induced by injection of 50 μL of 10 μM cardiotoxin (Sigma) in saline. At 2 and 5 days post-injury (d.p.i.), left hind limbs received 0.5 mg/mL rhFN-NM or mFN (Biopur) while right limbs received saline as internal controls. Muscles were harvested at 7 d.p.i. for analysis.

3.7. Cells

C2C12 myoblasts (ATCC® CRL-1772™) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Fisher Scientific, #11531831) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, #P4333) at 37°C under 5% CO₂. Four FN-derived polypeptides (rhFN-Peptide1–4; Sangon Biotech) targeting the integrin-α7β1 binding domain (FN residues 1477–1620) were synthesized. Experimental groups included: Coated substrates: rhFN-NM, native mouse FN (mFN; Abcam, #ab92784), or rhFN-Peptide1–4; Controls: Uncoated wells and untreated cells. Cellular senescence was induced by 1 h exposure to 400 μM H₂O₂ in complete medium, followed by 4 h recovery in fresh medium prior to assays.

3.8. CCK-8 Assay

Cell proliferation and viability were assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Abmole). C2C12 cells were seeded at 10⁴ cells/well in pre-coated 96-well plates and cultured for 3, 6 or 24 h. Subsequently, 10 μL CCK-8 reagent was added to each well, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 4 h. Optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm. Cell viability was calculated as:

Cell viability (%) = [OD (treatment group) -OD (blank)]/ [OD (untreated group) -OD (blank)] x 100

Where treatment group corresponds to wells containing cells treated with test materials (rhFN-NM, mFN, rhFN-Peptide1-4) or H₂O₂-induced senescent cells, plus CCK-8 solution. Untreated group represents wells with untreated cells (no coating/test material) plus CCK-8 solution. Blank is wells containing no cells, just culture medium and CCK-8 solution.

3.9. β-Galactosidase Staining

β-Galactosidase staining [

33] was performed with a senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining kit (Solarbio). C2C12 cells were placed in 6-well plates and incubated for 48 h. Cells were then washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min. Cells were incubated with staining mixture for 16 h at 37 °C. The percentage of positive cells was calculated by counting at least 300 cells in six microscopic fields. Image J was used to count the number of cells.

3.10. TUNEL Assays

Cell death was detected using the in situ cell death detection kit (TMR red, Roche). Cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 1 h, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and incubated in TUNEL staining solution at 37 °C for 1 h. Fluorescence images were obtained using an Olympus IX83 microscope.

3.11. Histology Staining

Mouse skeletal muscle samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution at 4 °C overnight, dehydrated through a gradient ethanol series, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 4-μm-thick slices. Tissue sections were collected and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Servicebio, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

3.12. Immunohistochemistry IHC Staining

Paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated through a graded alcohol series. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation with 3% H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies (all from Abcam, UK): anti-myosin heavy chain/MYH3 (clone F1.652; 1:200 dilution), CD68 (clone E307V; 1:100), and CD206/MRC1 (clone E6T5J; 1:200). Subsequently, sections were incubated with biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies at 4 °C for 50 min. After three washes with PBS, streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was applied, followed by development with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate. Chromogenic reaction was monitored in real-time by microscopy. Sections were then rinsed with distilled water, counterstained with hematoxylin, differentiated in 1% acid ethanol for 1 s, rinsed in tap water, blued in 0.1% ammonia solution, and finally washed under running water. Dehydration was performed through a graded ethanol series (70%, 95%, 100%), followed by clearing in xylene and mounting with neutral gum. Three representative fields per sample were imaged for analysis.

3.13. Immunostaining and Image Analysis

The paraffin sections were fixated in 4% PFA followed by counterstaining with the nuclear dye DAPI. For immunostaining, cells were blocked for 1–2 h in 5% goat serum before incubation with primary and secondary antibodies. The primary antibodies were: Pax-7(EE-8) 1:50 (Santa Cruz, United States), anti-laminin 1:50, anti-fibronectin 1:50, anti-fast skeletal myosin heavy chain 1:200, and anti-slow skeletal myosin heavy chain 1:500 (Abcam, United Kingdom). Image J was used to count the number of cells.

3.14. Detection of Cytokines by ELISA

The serum was centrifuged at 1,500 g for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was collected. The levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-10 were obtained using the enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Biocompany, Nanjing, China) in accordance with the manufacturer instructions.

3.15. Western Blot

Muscle proteins were extracted using a nondenaturing lysis buffer (e.g., Cell Signaling Technology, #9803) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Protein concentrations were normalized using a BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by biotinylation and antibody incubation. Cells for Western blot were grown for 3 h or 72 h in wells coated (treatment) in 6-well plates and lysed in RIPA buffer (Sigma). After adjustment of protein concentrations (as determined by BCA assays) samples were boiled in Laemmli buffer and used for Western blot. Antibodies used were: phospho-p44/42 MAPK (1:500, Abcam), p44/42MAPK (1:10000, Abcam), phospho-p38 MAPK (1:800, Gene Tex), p38 MAPK (1:800, Gene Tex), phospho-FAK (1:1000, Abcam), FAK (1:2000, Abcam), Laminin (1:2000, Novus), β-actin (1:1000, Abcam), GAPDH (1:2500, Abcam). Image J was used to analyze the images.

3.16. Quantitative PCR and Analysis

RNA was extracted from frozen muscles with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s instructions. Typically, 500 ng of total RNA were subjected to reverse transcription (RT) with FastKing one-step method (Tiangen). RT-PCR was performed using TB Green Premix Ex Taq (TliRNaseH Plus) to evaluate expression. Primers used were FN1-F: GGCCACACCTACAACCAGTA, FN1-R: TCGTCTCTGTCAGCTTGCAC, mGapdh-F: GTCAAGGCCGAGAATGGGAA and mGapdh-R: CTCGTGGTTCACACCCATCA. The relative expression of targ3.17.et genes was measured by the DDCt method according to:

ΔΔCt= experimental group (Ct target gene -Ct reference gene) - control group (Ct target gene -Ct reference gene)

The fold-change of mRNA expression was calculated by the 2-ΔΔCt method.

3.17. Flow Cytometric Analysis

Cell suspensions were obtained from triturated thymus and passed through a 200 µm nylon mesh. Flow cytometric analysis data were collected using the BD Fortessa Cell analyzer and analyzed utilizing the Kaluza software (Beckman). The following antibodies were purchased from BioLegend: APC/Cyanine7 anti-mouse CD45 Antibody (103116), PE anti-mouse CD4 Antibody (100512), PerCP anti-mouse CD8a Antibody (100732), Alexa Fluor® 488 anti-mouse CD3 antibody (100210), APC anti-mouse CD25 antibody (101910).

3.18. Statistics

For in vivo studies, data were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) and assessed for significance by a t-test, as appropriate. P-values were determined for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction. Values of P ≤ 0.05 (*), P ≤ 0.01 (**), P ≤ 0.005 (***), and P ≤ 0.001 (****) were considered significant. Statistical tests were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.0.

4. Discussion

Our study demonstrates that the engineered recombinant FN derivative rhFN-NM effectively enhances skeletal muscle repair in aging mice by mitigating oxidative stress, promoting satellite cell activation and modulating the immune microenvironment. By integrating MD-guided domain selection with functional validation, we developed a novel construct that bypasses the challenges of full-length FN expression while retaining critical integrin-binding and matrix-remodeling capabilities. These findings align with prior studies emphasizing the role of FN in maintaining muscle stem cell niche integrity [

1,

2], yet extend the field by introducing a safer, non-plasma-derived alternative with translational potential. In vitro, rhFN-NM significantly improved C2C12 myoblast adhesion and resilience to oxidative damage, while in vivo administration in geriatric mice accelerated muscle regeneration, as evidenced by elevated Pax7+ satellite cells, laminin expression, and M2 macrophage polarization. Notably, rhFN-NM exhibited comparable efficacy in IL-10(−/−) models, suggesting integrin-dependent mechanisms independent of IL-10-mediated anti-inflammatory pathways.

The lack of significant IL-10 elevation in rhFN-NM-treated groups may reflect microenvironment complexity in aged muscle, where multiple cytokines collectively regulate inflammation resolution rather than IL-10 alone. Future studies profiling broader cytokine networks (e.g., TGF-β, IL-4) could clarify this mechanism.

However, our study has limitations that warrant consideration. First, while controlled laboratory conditions ensured experimental rigor, key physiological variables influencing aged populations—such as nutritional status and physical activity—were not standardized. Age-related malnutrition (e.g., protein deficiency) may exacerbate FN depletion and alter therapeutic responses [

3], while sedentary laboratory environments might underestimate rhFN-NM’s benefits in active individuals where exercise synergistically enhances satellite cell function [

4]. Future studies should incorporate dietary interventions (e.g., low-protein diets) and exercise regimens to evaluate rhFN-NM’s robustness in clinically relevant scenarios.

Clinically, rhFN-NM holds distinct advantages over existing therapies. Compared to plasma-derived FN, it eliminates batch variability and pathogen risks [

5], while matching the efficacy of native FN in promoting laminin deposition and M2 macrophage recruitment. In contrast to stem cell therapies, which face engraftment challenges and complex delivery requirements [

6], rhFN-NM acts as a microenvironment modulator amenable to localized injection—a practical advantage for focal injuries. Nevertheless, challenges remain for broader applications, particularly in diffuse sarcopenia. Systemic delivery strategies (e.g., nanoparticle encapsulation) and combination therapies with exercise or nutritional supplements (e.g., leucine [

7]) represent promising avenues to enhance efficacy.

To bridge these gaps, we propose a structured preclinical roadmap that includes (i) comprehensive safety profiling, including 90-day toxicity studies in non-human primates to assess immunogenicity and organ-specific effects, (ii) advanced delivery optimization, such as thermosensitive hydrogels for sustained release at injury sites, (iii) humanized validation using muscle organoids derived from aged donors under variable nutrient/stress conditions [

8] and (iv) mechanistic expansion via single-cell RNA sequencing to identify novel ECM-integrin crosstalk targets potentiated by rhFN-NM.

By addressing these priorities, rhFN-NM could evolve into a versatile therapeutic agent, not only for age-related muscle atrophy but also for trauma rehabilitation and degenerative myopathies, ultimately bridging the gap between bench discoveries and clinical needs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yu-qi Chen; methodology, Yu-qi Chen; software, Yu-qi Chen; validation, Xiaoqin-Yu and Yu-xuan Fan; formal analysis, Yu-qi Chen; investigation, Yu-qi Chen and Yu-xuan Fan; resources, Yu-qi Chen; data curation, Yi-chao Dong; writing—original draft preparation, Yu-qi Chen; writing—review and editing, Yu-qi Chen; visualization, Yu-qi Chen; supervision, Jian-en Gao and Chang-long Guo; project administration, Jian-en Gao and Xu Ma; funding acquisition, Xu Ma.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of IACUC (protocol code YS2126A01224, approval date: 14 February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, we acknowledge lab members for discussion of the manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yamakawa, H.; Hoshino, D.; Fukaya, T. Stem cell aging in skeletal muscle regeneration and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, D.R.; Héroux, M.; Janssen, I. Association between muscle mass, leg strength, and fat mass with physical function in older adults: Influence of age and sex. J. Aging Health 2011, 23, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, H.M.; Cosgrove, B.D.; Ho, A.T. The central role of muscle stem cells in regenerative failure with aging. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Victor, P.; Gutarra, S.; García-Prat, L.; Rodriguez-Ubreva, J.; Ortet, L.; Ruiz-Bonilla, V.; Jardi, M.; Ballestar, E.; González, S.; Serrano, A.L.; et al. Muscle stem cell aging: Regulation and rejuvenation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 26, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, C.A.; Olsen, I.; Zammit, P.S.; Heslop, L.; Petrie, A.; Partridge, T.A.; Morgan, J.E. Stem cell function, self-renewal, and behavioral heterogeneity of cells from the adult muscle satellite cell niche. Cell 2005, 122, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danoviz, M.E.; Yablonka-Reuveni, Z. Skeletal muscle satellite cells: Background and methods for isolation and analysis in a primary culture system. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 798, 21–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.X.; Rudnicki, M.A. Satellite cells, the engines of muscle repair. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, B.M.; Faulkner, J.A. The regeneration of skeletal muscle fibers following injury: A review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1983, 15, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Zhou, R.; Tian, W.; Gao, C.; Li, L.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W. Multimodal cell atlas of the ageing human skeletal muscle. Nature 2024, 629, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Price, F.; Rudnicki, M.A. Satellite cells and the muscle stem cell niche. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 23–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankov, R.; Yamada, K.M. Fibronectin at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2002, 115, 3861–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kääriäinen, M.; Järvinen, T.L.; Järvinen, M.; Rantanen, J.; Kalimo, H. Expression of α7β1 integrin splicing variants during skeletal muscle regeneration. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 161, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkin, D.J.; Kaufman, S.J. The α7β1 integrin in muscle development and disease. Cell Tissue Res. 1999, 296, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Agthoven, J.F.; Xiong, J.; Arnaout, M.A. Integrin αVβ3 ectodomain bound to the tenth domain of fibronectin. Unpublished Work 2014. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Soler, D.; Chapman, T.; Yang, L.L.; Wyant, T.; Egan, R.; Fedyk, E.R. The binding specificity and selective antagonism of vedolizumab, an anti-α4β7 integrin therapeutic antibody in development for inflammatory bowel diseases. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 330, 864–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Agthoven, J.F.; Xiong, J.P.; Alonso, J.L.; Goodman, S.L.; Arnaout, M.A. Structural basis for pure antagonism of integrin αVβ3 by a high-affinity form of fibronectin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Schürpf, T.; Springer, T.A. How natalizumab binds and antagonizes α4 integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 32314–32325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Luo, B.H.; Barth, P.; Schonbrun, J.; Baker, D.; Springer, T.A. Structure of a complete integrin ectodomain in a physiologic resting state and activation and deactivation by applied forces. Mol. Cell 2008, 32, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, C.J.; Lemmon, C.A. Fibronectin: Molecular structure, fibrillar structure and mechanochemical signaling. Cells 2021, 10, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameduh, T.; Haddad, Y.; Adam, V.; Heger, Z. Homology modeling in the time of collective and artificial intelligence. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 3494–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, D.J.; Aukhil, I.; Erickson, H.P. Structure of a fibronectin type III domain from tenascin phased by MAD analysis of the selenomethionyl protein. Science 1992, 258, 987–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, A.L.; Harvey, T.S.; Baron, M.; Boyd, J.; Campbell, I.D. The three-dimensional structure of the tenth type III module of fibronectin: An insight into RGD-mediated interactions. Cell 1992, 71, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiser, A. Template-based protein structure modeling. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010, 673, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Yu, Z.; Hou, T. Improved protein structure prediction using a new multi-scale network and homologous templates. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 2021, 8, 2102592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerenberg, P.S.; Jo, B.; So, C.; Tripathy, A.; Head-Gordon, T. Evaluation and improvement of the Amber ff99SB force field with an advanced water model. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 311a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, H.G. Accuracy and efficiency of the particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 3668–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, R.; Kaul, S.C.; Ishii, T.; Chhipa, R.R.; Taira, K.; Sugimoto, Y.; Reddel, R.R. Molecular dynamics simulations and experimental studies reveal differential permeability of withaferin-A and withanone across the model cell membrane. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, Q.; Zhang, J. Large-scale application of free energy perturbation calculations for antibody design. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Xie, J.; Huang, Q.; Lu, X. Molecular modeling of fibronectin adsorption on topographically nanostructured rutile (110) surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 384, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler Leman, J.; Künze, G. Recent advances in NMR protein structure prediction with ROSETTA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debacq-Chainiaux, F.; Erusalimsky, J.D.; Campisi, J.; Toussaint, O. Protocols to detect senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-βgal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1798–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).