Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Parkinson´s Disease

2. Single-Neuron Degeneration

3. Endogenous Neurotoxins in Parkinson´s Disease

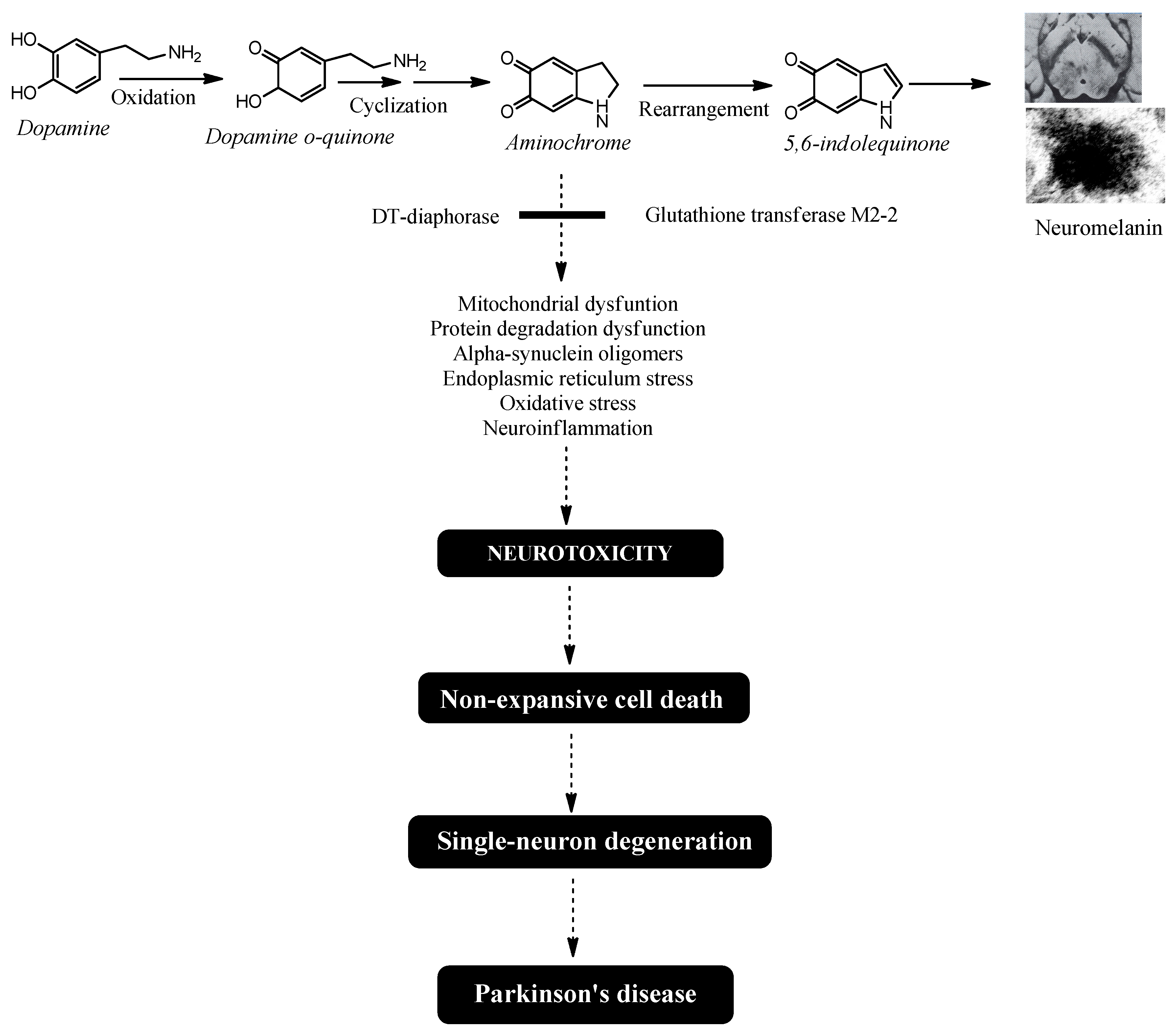

4. Why Can Aminochrome be Neurotoxic During Neuromelanin Synthesis?

- (i)

- DT-Diaphorase – DT-diaphorase (NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase; NQO1; EC 1.6.99.2) is a distinct flavoenzyme that catalyzes the two-electron reduction of quinones to hydroquinones [35]. Unlike other flavoenzymes—which use NADH or NADPH as electron donors to drive the one-electron reduction of quinones, producing highly reactive semiquinones—DT-diaphorase avoids semiquinone formation entirely. Semiquinones react with oxygen, generating superoxide and contributing to oxidative stress. For instance, NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase catalyzes the reduction of aminochrome to leukoaminochrome radicals, which are highly reactive with oxygen [36]. In contrast, DT-diaphorase facilitates the two-electron reduction of aminochrome directly to leukoaminochrome [37]. Inhibition of DT-diaphorase via siRNA has been demonstrated to trigger cell death in catecholaminergic cell cultures [38]. DT-diaphorase is expressed in multiple organs, including the brain, with notable activity in the substantia nigra, striatum, hypothalamus, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex. It represents 97% of total quinone reductase activity (which includes other NADH/NADPH-dependent flavoenzymes) and is present in both dopaminergic neurons and astrocytes [39]. DT-diaphorase provides protection against: aminochrome-induced cell death, formation of neurotoxic α-synuclein oligomers, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, autophagy and lysosomal dysfunction, disruption of cytoskeletal architecture [38,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

- (ii)

- Glutathione transferase M2-2 – This enzyme catalyzes the conjugation of aminochrome with glutathione, forming 4-S-glutathionyl-5,6-dihydroxyindoline, a compound resistant to biological oxidizing agents such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and dioxygen [53,54]. Glutathione transferase M2-2 also conjugates dopamine ortho-quinone (a precursor of aminochrome) to produce 5-glutathionyldopamine, which is typically metabolized into 5-cysteinyldopamine [55]. The detection of 5-cysteinyldopamine in human cerebrospinal fluid and neuromelanin suggests it is a stable end product, supporting its potential neuroprotective role. Notably, while glutathione transferase M2-2 is predominantly expressed in astrocytes, these cells secrete exosomes containing the enzyme, which then enter dopaminergic neurons and release the enzyme into their cytosol. This mechanism implies that astrocytes contribute to neuroprotection by boosting the defensive capacity of DT-diaphorase in neuromelanin-containing dopaminergic neurons [56,57,58,59].

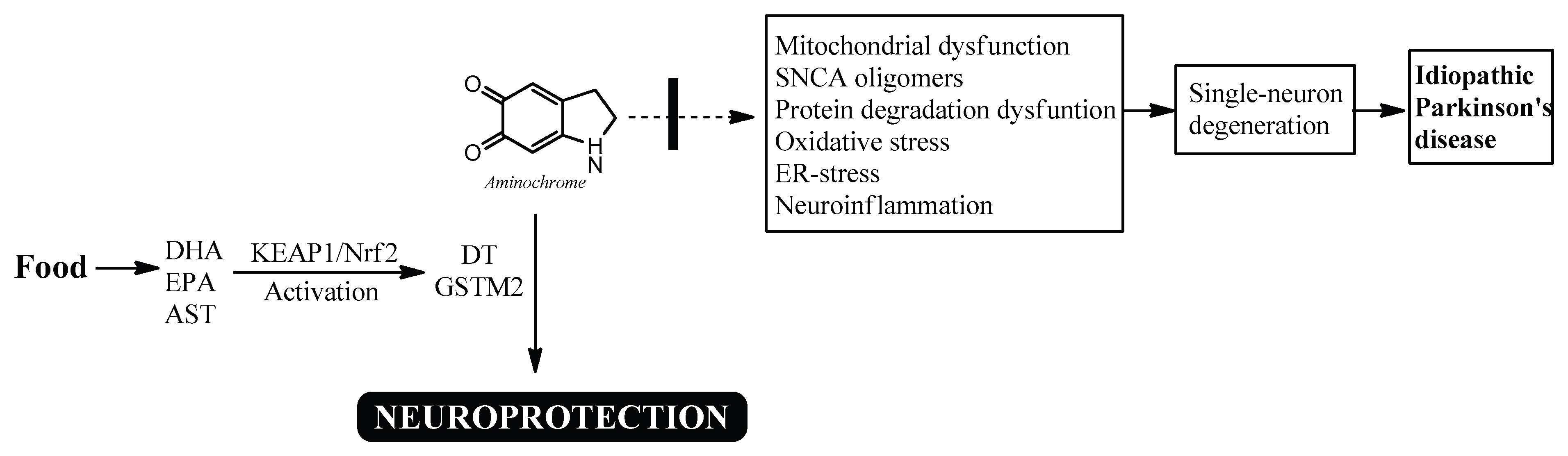

5. Natural Bioactive Compounds that Trigger Neuroprotection in Dopaminergic Neurons Containing Neuromelanin

6. Bioactive Compounds in Food

7. Conclusions

References

- Athauda, D.; Foltynie, T. The ongoing pursuit of neuroprotective therapies in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 11, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson Study Group QE3 Investigators Beal, M.F.; Oakes, D.; Shoulson, I.; Henchcliffe, C.; Galpern, W.R.; Haas, R.; Juncos, J.L.; Nutt, J.G.; Voss, T.S.; et al. Randomized clinical trial of high-dosage coenzyme Q10 in early Parkinson disease: No evidence of benefit. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, B.J.; Rolfe, F.L.; Lockhart, M.M.; Frampton, C.M.; O’Sullivan, J.D.; Fung, V.; Smith, R.A.; Murphy, M.P.; Taylor, K.M. ; Protect Study Group A double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ as a disease-modifying therapy in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 1670–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson Study Group SURE-PD3 Investigators Schwarzschild, M.A.; Ascherio, A.; Casaceli, C.; Curhan, G.C.; Fitzgerald, R.; Kamp, C.; Lungu, C.; Macklin, E.A.; Marek, K.; et al. Effect of Urate-Elevating Inosine on Early Parkinson Disease Progression: The SURE-PD3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021, 326, 926–939. [CrossRef]

- Warren Olanow, C.; Bartus, R.T.; Baumann, T.L.; Factor, S.; Boulis, N.; Stacy, M.; Turner, D.A.; Marks, W.; Larson, P.; Starr, P.A.; Jankovic, J.; Simpson, R.; Watts, R.; Guthrie, B.; Poston, K.; Henderson, J.M.; Stern, M.; Baltuch, G.; Goetz, C.G.; Herzog, C.; Kordower, J.H.; Alterman, R.; Lozano, A.M.; Lang, A.E. Gene delivery of neurturin to putamen and substantia nigra in Parkinson disease: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Neurol. 2015, 78, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olanow, C.W.; Bartus, R.T.; Volpicelli-Daley, L.A.; Kordower, J.H. Trophic factors for Parkinson's disease: To live or let die. Mov Disord. 2015, 30, 1715–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenka, A.; Jankovic, J. How should future clinical trials be designed in the search for disease-modifying therapies for Parkinson's disease? Expert Rev Neurother. 2023, 23, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, M.; Rascol, O.; Foltynie, T.; Carroll, C.; Postuma, R.B.; Porcher, R.; Corvol, J.C. Advantages and Challenges of Platform Trials for Disease Modifying Therapies in Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord. 2024, 39, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filograna, R.; Beltramini, M.; Bubacco, L.; Bisaglia, M. Anti-Oxidants in Parkinson's Disease Therapy: A Critical Point of View. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Aguilar, J. The importance of choosing a preclinical model that reflects what happens in Parkinson's disease. Neurochem Int. 2019, 126, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. MPTP parkinsonism. Br Med J. 1984, 289, 1401–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huenchuguala, S.; Segura-Aguilar, J. Single-neuron neurodegeneration as a degenerative model for Parkinson's disease. Neural Regen Res. 2024, 19, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonez, D.G.; Lee, M.K.; Feany, M.B. α-synuclein Induces Mitochondrial Dysfunction through Spectrin and the Actin Cy-toskeleton. Neuron. 2018, 97, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Martínez, A.; Martínez-Gómez, P.A.; Martinez-Fong, D.; Villegas-Rojas, M.M.; Pérez-Severiano, F.; Del Toro-Colín, M.A.; Delgado-Minjares, K.M.; Blanco-Alvarez, V.M.; Leon-Chavez, B.A.; Aparicio-Trejo, O.E.; et al. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Complex I Dysfunction Correlate with Neurodegeneration in an α-Synucleinopathy Animal Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, E.M.; De Miranda, B.; Sanders, L.H. Alpha-synuclein: Pathology, mitochondrial dysfunction and neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 109 Pt B, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, A.C.; Erustes, A.G.; Reckziegel, P.; Bincoletto, C.; Ureshino, R.P.; Pereira, G.J.S.; Smaili, S.S. α-Synuclein Overexpression Induces Lysosomal Dysfunction and Autophagy Impairment in Human Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y. Neurochem. Res. 2020, 45, 2749–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, B.; Galka, D.; Häffner, N.; Wang, D.; Schmitt, K.; Valerius, O.; Knop, M.; Braus, G.H. α-Synuclein Decreases the Abundance of Proteasome Subunits and Alters Ubiquitin Conjugates in Yeast. Cells. 2021, 10, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Wong, Y.C.; Ysselstein, D.; Severino, A.; Krainc, D. Synaptic, Mitochondrial, and Lysosomal Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease. Trends Neurosci. 2019, 42, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Thiruchelvam, M.J.; Madura, K.; Richfield, E.K. Proteasome dysfunction in aged human alpha-synuclein transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006, 23, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Cardenas, S.; Huenchuguala, S.; Briceño, A.; Couve, E.; Paris, I.; Segura-Aguilar, J. DT-Diaphorase Prevents Aminochrome-Induced Alpha-Synuclein Oligomer Formation and Neurotoxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2015, 145, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, A.; Ernst, C. Evidence That Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta Dopaminergic Neurons Are Selectively Vulnerable to Oxidative Stress Because They Are Highly Metabolically Active. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 826193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Acuña, D.; Shin, S.J.; Rhee, K.H.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, S.J. α-Synuclein propagation leads to synaptic abnormalities in the cortex through microglial synapse phagocytosis. Mol. Brain. 2023, 16, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, M.X.; Cornblath, E.J.; Darwich, A.; Zhang, B.; Brown, H.; Gathagan, R.J.; Sandler, R.M.; Bassett, D.S.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.Y. Spread of α-synuclein pathology through the brain connectome is modulated by selective vulnerability and predicted by network analysis. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Kwon, S.H.; Kam, T.I.; Panicker, N.; Karuppagounder, S.S.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, W.R.; Kook, M.; Foss, C.A.; et al. Transneuronal Propagation of Pathologic α-Synuclein from the Gut to the Brain Models Parkinson’s Disease. Neuron. 2019, 103, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuzumi, A.; Hatano, T.; Matsumoto, G.; Nojiri, S.; Ueno, S.I.; Imamichi-Tatano, Y.; Kimura, H.; Kakuta, S.; Kondo, A.; Fukuhara, T.; et al. Propagative α-synuclein seeds as serum biomarkers for synucleinopathies. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1448–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigi, A.; Cascella, R.; Cecchi, C. α-Synuclein oligomers and fibrils: Partners in crime in synucleinopathies. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 2332–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desplats, P.; Lee, H.J.; Bae, E.J.; Patrick, C.; Rockenstein, E.; Crews, L.; Spencer, B.; Masliah, E.; Lee, S.J. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of alpha-synuclein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009, 106, 13010–13015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Aguilar. Dopamine oxidative deamination. In Segura-Aguilar, editor, Clinical Studies and Therapies in Parkinson's Disease-Translations from Preclinical Models, Elsevier; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2021, pp 203-207.

- Goldstein, D.S. The “Sick-but-not-Dead” phenomenon applied to catecholamine deficiency in neurodegenerative diseases. Semin. Neurol. 2020, 40, 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinsmaa, Y.; Sullivan, P.; Sharabi, Y.; Goldstein, D.S. DOPAL is transmissible to and oligomerizes alpha-synuclein in human glial cells. Auton. Neurosci. 2016, 194, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisaglia, M.; Mammi, S.; Bubacco, L. Kinetic and structural analysis of the early oxidation products of dopamine: Analysis of the interactions with alpha-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 15597–15605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecca, L.; Fariello, R.; Riederer, P.; Sulzer, D.; Gatti, A.; Tampellini, D. The absolute concentration of nigral neuromelanin, assayed by a new sensitive method, increases throughout the life and is dramatically decreased in Parkinson’s disease. FEBS Lett. 2002, 510, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, F.A.; Basso, E.; Cupaioli, F.A.; Ferrari, E.; Sulzer, D.; Casella, L.; Zecca, L. Neuromelanin of the human substantia nigra: an update. Neurotox Res. 2014, 25, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, F.A.; Capucciati, A.; Bellei, C.; Sarna, M.; Sarna, T.; Monzani, E.; Casella, L.; Zecca, L. Neuromelanins in brain aging and Parkinson's disease: synthesis, structure, neuroinflammatory, and neurodegenerative role. IUBMB Life. 2023, 75, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Aguilar. Neuroprotective mechanisms against dopamine oxidation-dependent neurotoxicity. In Segura-Aguilar, editor, Clinical Studies and Therapies in Parkinson's Disease-Translations from Preclinical Models, Elsevier; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2021, Pages 229-240.

- Segura-Aguilar, J.; Metodiewa, D.; Welch, C.J. Metabolic activation of dopamine o-quinones to o-semiquinones by NADPH cytochrome P450 reductase may play an important role in oxidative stress and apoptotic effects. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998, 1381, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Aguilar, J.; Lind, C. On the mechanism of the Mn3(+)-induced neurotoxicity of dopamine:prevention of quinone-derived oxygen toxicity by DT diaphorase and superoxide dismutase. Chem Biol Interact. 1989, 72, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, J.; Muñoz, P.; Nore, B.F.; Ledoux, S.; Segura-Aguilar, J. Stable expression of short interfering RNA for DT-diaphorase induces neurotoxicity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010, 23, 1492–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultzberg, M.; Segura-Aguilar, J.; Lind, C. Distribution of DT diaphorase in the rat brain: biochemical and immunohistochemical studies. Neuroscience. 1988, 27, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arriagada, C.; Paris, I.; Sanchez de las Matas, M.J.; Martinez-Alvarado, P.; Cardenas, S.; Castañeda, P.; Graumann, R.; Perez-Pastene, C.; Olea-Azar, C.; Couve, E.; et al. On the neurotoxicity mechanism of leukoaminochrome o-semiquinone radical derived from dopamine oxidation: Mitochondria damage, necrosis, and hydroxyl radical formation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2004, 16, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, P.; Cardenas, S.; Huenchuguala, S.; Briceño, A.; Couve, E.; Paris, I.; Segura-Aguilar, J. DT-Diaphorase Prevents Aminochrome-Induced Alpha-Synuclein Oligomer Formation and Neurotoxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 2015, 145, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Huenchuguala, S.; Paris, I.; Segura-Aguilar, J. Dopamine oxidation and autophagy. Parkinsons. Dis. 2012, 2012, 920953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, I.; Perez-Pastene, C.; Cardenas, S.; Iturriaga-Vasquez, P.; Muñoz, P.; Couve, E.; Caviedes, P.; Segura-Aguilar, J. Aminochrome induces disruption of actin, alpha-, and beta-tubulin cytoskeleton networks in substantia-nigra-derived cell line. Neurotox. Res. 2010, 18, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez, C.; Muñoz, P.; Segura-Aguilar, J. DT-Diaphorase Prevents Aminochrome-Induced Lysosome Dysfunction in SH-SY5Y Cells. Neurotox. Res. 2019, 35, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, I.; Muñoz, P.; Huenchuguala, S.; Couve, E.; Sanders, L.H.; Greenamyre, J.T.; Caviedes, P.; Segura-Aguilar, J. Autophagy protects against aminochrome-induced cell death in substantia nigra-derived cell line. Toxicol Sci. 2011, 121, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, K.S.; Inayat-Hussain, S.H.; Siegel, D.; Bao, A.; Shieh, B.; Ross, D. Overexpression of NQO1 protects human SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells against dopamine-induced cell death. Toxicol. Lett. 2006, 166, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huenchuguala, S.; Muñoz, P.; Segura-Aguilar, J. The Importance of Mitophagy in Maintaining Mitochondrial Function in U373MG Cells. Bafilomycin A1 Restores Aminochrome-Induced Mitochondrial Damage. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017, 8, 2247–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Aguilar, J. On the Role of Aminochrome in Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Parkinson's Disease. Front Neurosci. 2019, 13, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Aguilar, J.; Baez, S.; Widersten, M.; Welch, C.J.; Mannervik, B. Human class Mu glutathione transferases, in particular isoenzyme M2-2, catalyze detoxication of the dopamine metabolite aminochrome. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272, 5727–5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, S.; Segura-Aguilar, J.; Widersten, M.; Johansson, A.S.; Mannervik, B. Glutathione transferases catalyse the detoxication of oxidized metabolites (o-quinones) of catecholamines and may serve as an antioxidant system preventing degenerative cellular processes. Biochem J. 1997, 324 ( Pt 1)(Pt 1), 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huenchuguala, S.; Muñoz, P.; Zavala, P.; Villa, M.; Cuevas, C.; Ahumada, U.; Graumann, R.; Nore, B.; Couve, E.; Mannervik, B.; et al. Glutathione transferase mu 2 protects glioblastoma cells against aminochrome toxicity by preventing autophagy and lysosome dysfunction. Autophagy. 2014, 10, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnino-Subiabre, A.; Cassels, B.K.; Baez, S.; Johansson, A.S.; Mannervik, B.; Segura-Aguilar, J. Glutathione transferase M2-2 catalyzes conjugation of dopamine and dopa o-quinones. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000, 274, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuevas, C.; Huenchuguala, S.; Muñoz, P.; Villa, M.; Paris, I.; Mannervik, B.; Segura-Aguilar, J. Glutathione transferase-M2-2 secreted from glioblastoma cell protects SH-SY5Y cells from aminochrome neurotoxicity. Neurotox Res. 2015, 27, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, R.; Armijo, A.; Muñoz, P.; Hultenby, K.; Hagg, A.; Inzunza, J.; Nalvarte, I.; Varshney, M.; Mannervik, B.; Segura-Aguilar, J. Cellular Trafficking of Glutathione Transferase M2-2 Between U373MG and SHSY-S7 Cells is Mediated by Exosomes. Neurotox Res. 2021, 39, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Aguilar, J.; Muñoz, P.; Inzunza, J.; Varshney, M.; Nalvarte, I.; Mannervik, B. Neuroprotection against Aminochrome Neurotoxicity: Glutathione Transferase M2-2 and DT-Diaphorase. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022, 11, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Aguilar, J.; Mannervik, B.; Inzunza, J.; Varshney, M.; Nalvarte, I.; Muñoz, P. Astrocytes protect dopaminergic neurons against aminochrome neurotoxicity. Neural Regen Res. 2022, 17, 1861–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Aguilar, J.; Mannervik, B. A Preclinical Model for Parkinson's Disease Based on Transcriptional Gene Activation via KEAP1/NRF2 to Develop New Antioxidant Therapies. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023, 12, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huenchuguala, S.; Segura-Aguilar, J. Natural Compounds That Activate the KEAP1/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway as Potential New Drugs in the Treatment of Idiopathic Parkinson's Disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024, 13, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.H. Health-promoting components of fruits and vegetables in the diet. Adv Nutr. 2013, 4, 384S–92S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufingerl, N.; Eilander, A. Nutrient Intake and Status in Adults Consuming Plant-Based Diets Compared to Meat-Eaters: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2021, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, A.; Ohizumi, Y. Potential Benefits of Nobiletin, A Citrus Flavonoid, against Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidy, N.; Behzad, S.; Habtemariam, S.; Ahmed, T.; Daglia, M.; Nabavi, S.M.; Sobarzo-Sanchez, E.; Nabavi, S.F. Neuroprotective Effects of Citrus Fruit-Derived Flavonoids, Nobiletin and Tangeretin in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's Disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2017, 16, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, B.; Dinda, M.; Kulsi, G.; Chakraborty, A.; Dinda, S. Therapeutic potentials of plant iridoids in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases: A review. Eur J Med Chem. 2019, 169, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Liu, J.; Meng, T.; Li, Y.; He, D.; Ran, X.; Chen, G.; Guo, W.; Kan, X.; Fu, S.; Wang, W.; Liu, D. Polydatin Prevents Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Induced Parkinson's Disease via Regulation of the AKT/GSK3β-Nrf2/NF-κB Signaling Axis. Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J.; Feng, L. Caffeic acid reduces A53T α-synuclein by activating JNK/Bcl-2-mediated autophagy in vitro and improves behaviour and protects dopaminergic neurons in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol Res. 2019, 150, 104538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Feng, B.N.; Hu, B.; Cheng, Y.L.; Guo, Y.H.; Qian, H. Neuroprotection of chicoric acid in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease involves gut microbiota and TLR4 signaling pathway. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 2019–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.M.; Lee, Y.; Chun, H.J.; Kim, A.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Ishigami, A.; Lee, J. Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of morin in a murine model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci Res. 2016, 94, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.M.; Wang, M.; Xiao, X.; Shi, Y.L.; Zheng, Y.S.; Huang, Z.H.; Cheng, Y.T.; Huang, R.T.; Huang, F.; Li, K.; Sun, J.; Sun, W.Y.; Kurihara, H.; Li, Y.F.; Duan, W.J.; He, R.R. Wolfberry (Lycium barbarum) glycopeptide attenuates dopaminergic neurons loss by inhibiting lipid peroxidation in Parkinson's disease. Phytomedicine. 2025, 136, 156275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Sattar, E.; Mahrous, E.A.; Thabet, M.M.; Elnaggar, D.M.Y.; Youssef, A.M.; Elhawary, R.; Zaitone, S.A.; Celia Rodríguez-Pérez Segura-Carretero, A.; Mekky, R.H. Methanolic extracts of a selected Egyptian Vicia faba cultivar mitigate the oxidative/inflammatory burden and afford neuroprotection in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Inflammopharmacology. 2021, 29, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Chen, L.; Liu, R.; Liu, Q.S.; Cheng, Y. Sophora alopecuroides Alleviates Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Damage of Parkinson's Disease In Vitro and In Vivo. Am J Chin Med. 2023, 51, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandalise, F.; Roda, E.; Ratto, D.; Goppa, L.; Gargano, M.L.; Cirlincione, F.; Priori, E.C.; Venuti, M.T.; Pastorelli, E.; Savino, E.; Rossi, P. Hericium erinaceus in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From Bench to Bedside and Beyond, How Far from the Shoreline? J Fungi (Basel). 2023, 9, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, I.C.; Lee, L.Y.; Tzeng, T.T.; Chen, W.P.; Chen, Y.P.; Shiao, Y.J.; Chen, C.C. Neurohealth Properties of Hericium erinaceus Mycelia Enriched with Erinacines. Behav Neurol. 2018, 2018, 5802634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Wang, V.; Chen, B.H. Analysis of bioactive compounds in cinnamon leaves and preparation of nanoemulsion and byproducts for improving Parkinson's disease in rats. Front Nutr. 2023, 10, 1229192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechowska, P.; Zawirska-Wojtasiak, R.; Mildner-Szkudlarz, S. Bioactive β-Carbolines in Food: A Review. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, A.; Ohizumi, Y. Potential Benefits of Nobiletin, A Citrus Flavonoid, against Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Liu, J.; Meng, T.; Li, Y.; He, D.; Ran, X.; Chen, G.; Guo, W.; Kan, X.; Fu, S.; Wang, W.; Liu, D. Polydatin Prevents Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Induced Parkinson's Disease via Regulation of the AKT/GSK3β-Nrf2/NF-κB Signaling Axis. Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J.; Feng, L. Caffeic acid reduces A53T α-synuclein by activating JNK/Bcl-2-mediated autophagy in vitro and improves behaviour and protects dopaminergic neurons in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol Res. 2019, 150, 104538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoi, M.; Maruyama, W.; Shamoto-Nagai, M. Disease-modifying treatment of Parkinson's disease by phytochemicals: targeting multiple pathogenic factors. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2022, 129, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Zhang, Y.; Botchway, B.O.A.; Zhang, J.; Fan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Curcumin can improve Parkinson's disease via activating BDNF/PI3k/Akt signaling pathways. Food Chem Toxicol. 2022, 164, 113091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.S.; Jha, N.K.; Jha, S.K.; Verma, P.R.P.; Ashraf, G.M.; Singh, S.K. Neuroprotective Role of Quercetin against Alpha-Synuclein-Associated Hallmarks in Parkinson's Disease. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 1464–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratih, K.; Lee, Y.R.; Chung, K.H.; Song, D.H.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, D.H.; An, J.H. L-Theanine alleviates MPTP-induced Parkinson's disease by targeting Wnt/β-catenin signaling mediated by the MAPK signaling pathway. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023, 226, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholewski, M.; Tomczykowa, M.; Tomczyk, M. A Comprehensive Review of Chemistry, Sources and Bioavailability of Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Nutrients. 2018, 10, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarra, N.M.; Marçalo, A.; Cordeiro, A.R.; Pousão-Ferreira, P. Sardine (Sardina pilchardus) lipid composition: Does it change after one year in captivity? Food Chem. 2018, 244, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, F.; Nieman, D.C.; Sha, W.; Xie, G.; Qiu, Y.; Jia, W. Supplementation of milled chia seeds increases plasma ALA and EPA in postmenopausal women. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2012, 67, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, H.O.; Price, J.C.; Bueno, A.A. Beyond Fish Oil Supplementation: The Effects of Alternative Plant Sources of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids upon Lipid Indexes and Cardiometabolic Biomarkers-An Overview. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Song, C. Potential treatment of Parkinson's disease with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Nutr Neurosci. 2022, 25, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.A.; Delattre, A.M.; Carabelli, B.; Pudell, C.; Bortolanza, M.; Staziaki, P.V.; Visentainer, J.V.; Montanher, P.F.; Del Bel, E.A.; Ferraz, A.C. Neuroprotective effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the 6-OHDA model of Parkinson's disease is mediated by a reduction of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Nutr Neurosci. 2018, 21, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delattre, A.M.; Kiss, A.; Szawka, R.E.; Anselmo-Franci, J.A.; Bagatini, P.B.; Xavier, L.L.; Rigon, P.; Achaval, M.; Iagher, F.; de David, C.; Marroni, N.A.; Ferraz, A.C. Evaluation of chronic omega-3 fatty acids supplementation on behavioral and neurochemical alterations in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesion model of Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Res. 2010, 66, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguro, A.; Ishihara, Y.; Siswanto, F.M.; Yamazaki, T.; Ishida, A.; Imaishi, H.; Imaoka, S. Contribution of DHA diols (19,20-DHDP) produced by cytochrome P450s and soluble epoxide hydrolase to the beneficial effects of DHA supplementation in the brains of rotenone-induced rat models of Parkinson's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2021, 1866, 158858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitre, N.M.; Wood, B.J.; Ray, A.; Moniri, N.H.; Murnane, K.S. Docosahexaenoic acid protects motor function and increases dopamine synthesis in a rat model of Parkinson's disease via mechanisms associated with increased protein kinase activity in the striatum. Neuropharmacology. 2020, 167, 107976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando, S.; Requejo, C.; Herran, E.; Ruiz-Ortega, J.A.; Morera-Herreras, T.; Lafuente, J.V.; Ugedo, L.; Gainza, E.; Pedraz, J.L.; Igartua, M.; Hernandez, R.M. Beneficial effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids administration in a partial lesion model of Parkinson's disease: The role of glia and NRf2 regulation. Neurobiol Dis. 2019, 121, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchtman, D.W.; Meng, Q.; Wang, X.; Shao, D.; Song, C. ω-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid attenuates MPP+-induced neurodegeneration in fully differentiated human SH-SY5Y and primary mesencephalic cells. J Neurochem. 2013, 124, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceccarini, M.R.; Ceccarelli, V.; Codini, M.; Fettucciari, K.; Calvitti, M.; Cataldi, S.; Albi, E.; Vecchini, A.; Beccari, T. The Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid EPA, but Not DHA, Enhances Neurotrophic Factor Expression through Epigenetic Mechanisms and Protects against Parkinsonian Neuronal Cell Death. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 16176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alves, B.D.S.; Schimith, L.E.; da Cunha, A.B.; Dora, C.L.; Hort, M.A. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and Parkinson's disease: A systematic review of animal studies. J Neurochem. 2024, 168, 1655–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saw, C.L.; Yang, A.Y.; Guo, Y.; Kong, A.N. Astaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids individually and in combination protect against oxidative stress via the Nrf2-ARE pathway. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013, 62, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Source | Amount of total lipids | Reference | |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) |

Herring | 15 % | [85] |

| Wild sardine | 13.6 % in muscle | [86] | |

| Pollock roe | 18.8 | [85] | |

| Undaria pinnatifida | 13 % of essential oil composition) | [85] | |

| Rhododendron sochadzeae | 2 % of leaf extract |

[85] | |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) | Flyingfish | 27.9 % | [85] |

| Herring | 22.6 % | [85] | |

| Pollock | 22.2 % | [85] | |

| Salmon roe | 17.4 % | [85] | |

| Cirrhinus mrigata | 18.07 g/ 100 g muscle | [85] | |

| Catla catla | 17.98 g/100 g muscle | [85] | |

| Jackalberry | 4.54 g/ 100 g oil | [85] | |

| Alpha-linolenic acid | Chia (Salvia hispanica L.) seed | 64.04% of seed oil fatty acids | [85] |

| Trichosanthes kirilowii | 33.77–38.66% of seed oils | [85] | |

| Paprika Capsicum annuum | 29.93% of fresh pericarp fatty acids in the Jaranda variety and 30.27% in the Jariza variety | [85] | |

| Sardine (Sardina pilchardus) |

1.1 | [86] | |

| Linum usitatissimum | 1.1 to 65.2 % | [85] | |

| Rapeseed oil | 9.1 % | [88] | |

| Olive oil | 0.76 % | [88] | |

| Flaxseed oil | 53.4 % | [88] | |

| Soybean oil | 6.7 % | [88] | |

| Corn oil | 1.2 % | [88] | |

| Walnut oil | 10.4 % | [88] | |

| Walnuts seed | 9.0 % of the total seed weight | [88] | |

| Flaxseed seed | 22.8 % of the total seed weight | [88] | |

| Hemp seed | 10 % of the total seed weight | [88] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).