1. Introduction

The nuclear track detection in solid state detectors is widely used to measure different types of ionizing radiations, i. e., electrons, positrons, protons, neutrons, deuterons, alpha particles, fission fragments and cosmic rays, through track formation [

1,

2,

3]. This nuclear detection technique provides the simplest, easiest and cheapest method for particle registration, which can be employed in different fields of science and technology, from nuclear physics to geology and from space physics to archaeology [

4,

5,

6,

7].

When a charged particle interacts with a polymeric material, it loses energy mainly through ionization and excitation processes, which induce physical and chemical modifications of the material’s molecular structure [

8,

9]. The stopping power of a charged particle in matter can be electronic, nuclear, Bremsstrahlung radiation, and radiative, depending on its interaction cross-section and its energy. The stopping power from collisional processes generates the most significant changes in the material properties.

The damaged trail left by the particle in the material is called a latent track. The particle latent track can be observed by using a chemical etching process which enlarges the track dimensions and makes it visible under an ordinary optical microscope [

10]. The chemical reaction between the chemical agent and the polymeric detector (material composed of long chains of repeating molecules) is more intense in the region damaged by the particle than in the bulk of the detector without irradiation. The track development is governed by two parameters, which are the track etch rate

and the bulk etch rate

. When

is higher than

, the track visualization is formed [

11]. Therefore, studying the track etching efficiency is very important to comprehend the relative detection sensitivity of Solid State Nuclear Track Detectors (SSNTDs).

Track parameters such as length, depth, and diameter are critical for understanding the underlying physics of track formation in SSNTDs. While previous studies have explored aspects of alpha particle interactions in detectors like CR-39 and LR-115, they often focus on either limited energy ranges or normal incidence conditions, and do not provide a comprehensive view of how these parameters evolve with both energy and incident angle (e.g., [

11,

12].

Recent work underscores renewed interest in LR-115 SSNTDs for radon diagnostics and detector physics. For example, non-destructive characterization via XRD/UV–Vis has been used to establish LR-115 sensitivity limits and dose-dependent structural/optical changes; large-scale field campaigns continue to deploy LR-115 in diffusion chambers and bare mode; intercomparisons and new compact sensing configurations (e.g., activated-carbon–assisted LR-115) demonstrate improved sensitivity and fine spatial mapping. These advances contextualize and motivate our focus on alpha-track length characterization in LR-115 and help clarify the manuscript’s contribution relative to the current state of the art [

13,

14,

15,

16].

The present work offers a novel and comprehensive investigation into the geometric and etching characteristics of alpha-particle tracks in LR-115 detectors, focusing on the maximum etched track length as a function of initial alpha energy (1–5 MeV) and incident angle (0

–70

). While previous studies have typically examined either the energy–range relationship (e.g., [

12]) or the angular dependence of track detection (e.g., [

11]) in isolation, this study uniquely combines both variables within a unified simulation framework. By simultaneously exploring the influence of energy and incident angle, we determine the critical detection angle and establish quantitative etching thresholds. These findings are crucial for improving the accuracy of detector calibration and enhancing applications in radiation dosimetry and environmental monitoring.

Furthermore, we employ Geant4 Monte Carlo simulations, a robust and widely validated toolkit for modeling particle–matter interactions [

17,

18]. In contrast to prior analytical or semi-empirical models, such as those utilizing the Durrani–Green function to describe etching ratios as functions of incident energy and angle [

19], or empirical equations modeling track length evolution in CR-39 detectors [

20], our approach allows for a high-resolution simulation of track geometry formation by accounting for energy loss, angular scattering, and detailed material interactions within the LR-115 detector medium. Through this method, we develop empirical relationships, such as quadratic fits, between the maximum etched track length and the particle’s energy and angle, offering a new predictive framework for detector response under various experimental conditions.

2. Analytical Procedure

To investigate the track formation and evolution of alpha particles in LR-115 detectors, we adopted a two-pronged approach combining Monte Carlo simulations with controlled laboratory experiments. The simulation component was used to model particle interactions and energy deposition profiles inside the detector material, enabling a systematic study of the maximum track lengths as a function of incident angle and initial energy. Complementarily, experimental measurements were carried out to determine key etching parameters, such as the bulk and track etch rates, which govern the development of etched tracks. Together, these methods provide a comprehensive framework for analyzing the range-dependent behavior of alpha tracks and evaluating the critical conditions that define their maximum observable length.

2.1. Monte Carlo Simulation Strategy

The interaction of alpha particles with the LR-115 nuclear track detector was simulated using Geant4 (Geometry and Tracking - version 11.3.2), a Monte Carlo-based toolkit for modeling particle transport and interactions with matter [

17]. We employed the

emstandard_opt4 physics list with detailed treatment of multiple scattering, ionization, and energy-loss processes. The LR-115 active layer was represented as a 12 µm cellulose nitrate film (density = 1.4 g/cm

3) supported by a polyester substrate. Production cuts and step limits were set to ensure submicron accuracy in track-length determination.

A collimated monoenergetic alpha-particle beam was simulated with energies sampled uniformly between 1 and 5 MeV. The incidence zenith angle was varied from 0 (normal to the detector plane) to 70 in steps of 10. To refine the determination of the critical angle for track registration, additional simulations were performed in 1 steps between 51 and 59. For each angle, primary events were generated using independent random seeds.

The maximum longitudinal track length () was obtained directly from the simulated particle ranges, corrected for geometry, and combined with experimentally determined etching parameters (bulk etch rate and track etch rate ). This approach enabled the evaluation of the angular cutoff and mapping of for the LR-115 under standard etching conditions.

2.2. Experimental Approach

The bulk etch rate (

) of the LR-115 nuclear track detector was experimentally determined using the relation

, where

D represents the diameter of tracks (in µm) produced by normally incident alpha particles, and

t is the chemical etching time in hours [

21]. The LR-115 detector used in this work is type II, non-strippable films, purchased from KODAK. The samples consist of 12 µm-thick sensitive layers of red cellulose nitrate plastic deposited on a non-etchable clear polyester base 100 µm thick. The detectors were cut into a size of 1 × 1 cm

2 and irradiated with alpha particles from a

226Ra point source with a nominal activity of 3.3 kBq (8.9 ×

Ci). The

226Ra source was positioned close to the detector, directly in front and centered within the setup. The samples were irradiated for one minute, which is enough to have a good track-density distribution.

After irradiation, the detectors were chemically etched in a 2.5 N NaOH solution at 60.0 ± 0.5

C using a water bath with thermostat control [

22]. Etching times ranged from 20 to 140 minutes in 20-minute increments. However, tracks became visible under an optical microscope only after 80 minutes of etching. At 140 minutes, the LR-115 film was completely dissolved from the polyester base. Therefore, track evolution was analyzed for etching times between 70 and 130 minutes, in 10-minute steps. The relationship between track diameter for normally incident particles and etching time enabled the determination of the bulk etch rate [

23].

Regarding the track etch rate (

), it is determined using the following expression [

24]:

where

,

D is the track diameter, and

x is the removed thickness of the detector bulk during the etching time

t.

During the etching process, when the etchant reaches the end of the particle trajectory, the track etch rate

decreases to match the bulk etch rate

, transitioning the track geometry from a conical phase to an over-etched stage. At this point, the track length reaches its maximum value (

), which can be calculated as follows [

25]:

where the first equation applies to normal incidence and the second to an incident angle

. Here,

is the complete etching time, i.e., the time required for the etchant to reach the endpoint of the particle trajectory, given by

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Etched Track Analysis of Alpha Particles in LR-115 Detector

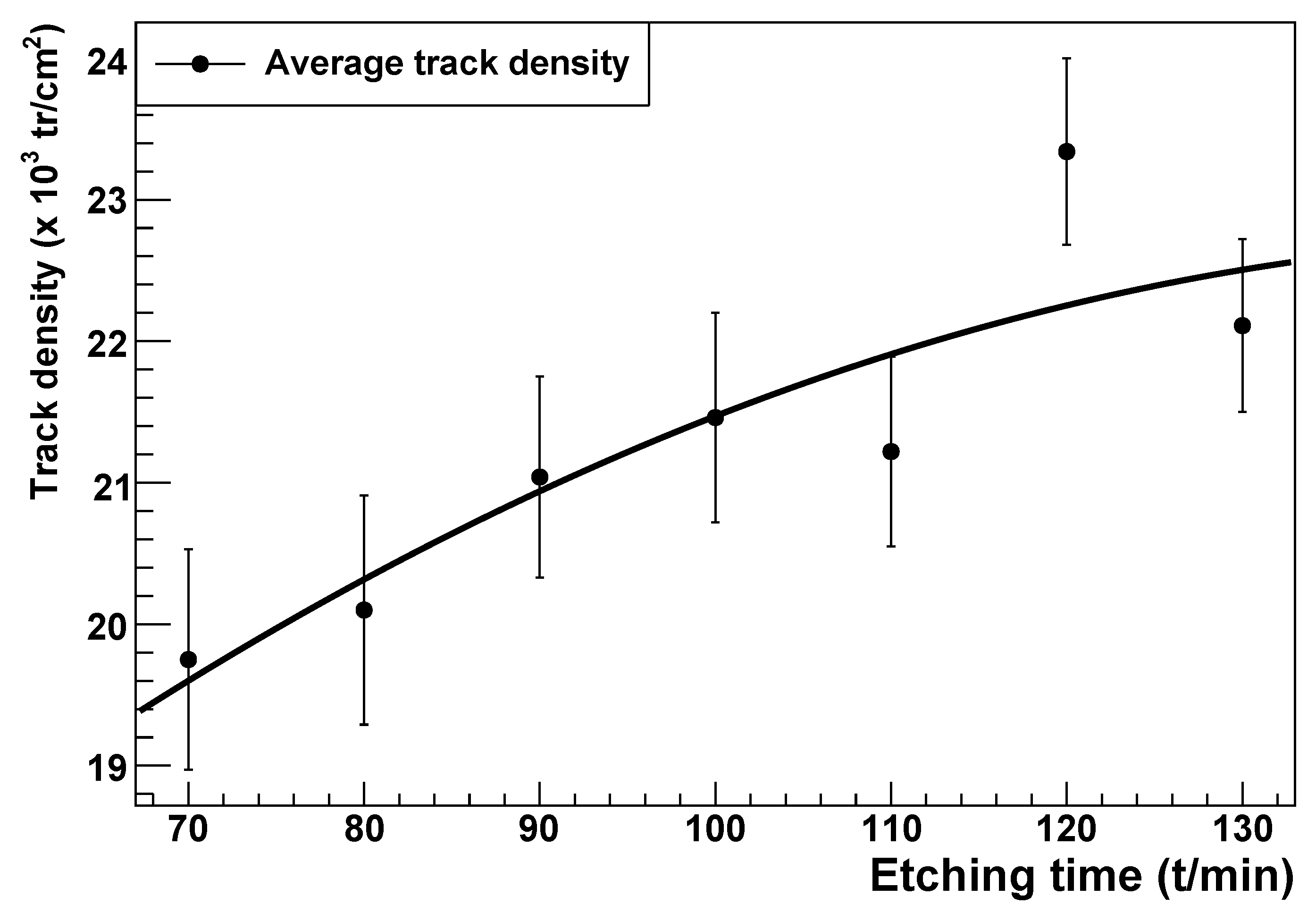

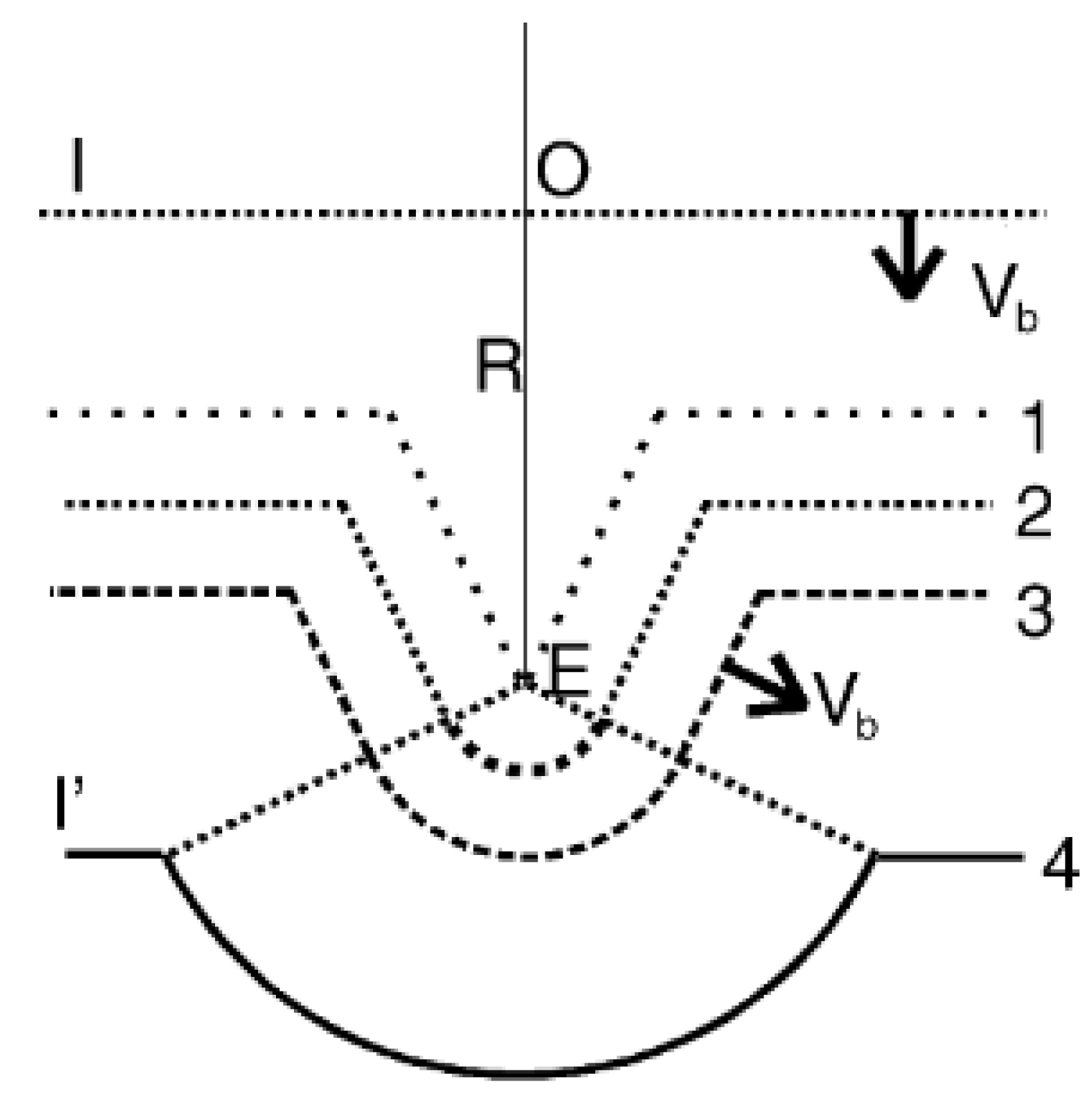

Figure 1 shows the track density distribution as a function of etching time. Since the majority of alpha particles are incident nearly perpendicular to the detector surface, the analysis of track diameters focused on tracks exhibiting a circular opening. A schematic illustration of the circular track opening construction is presented in

Figure 2 (extracted from [

11]), while

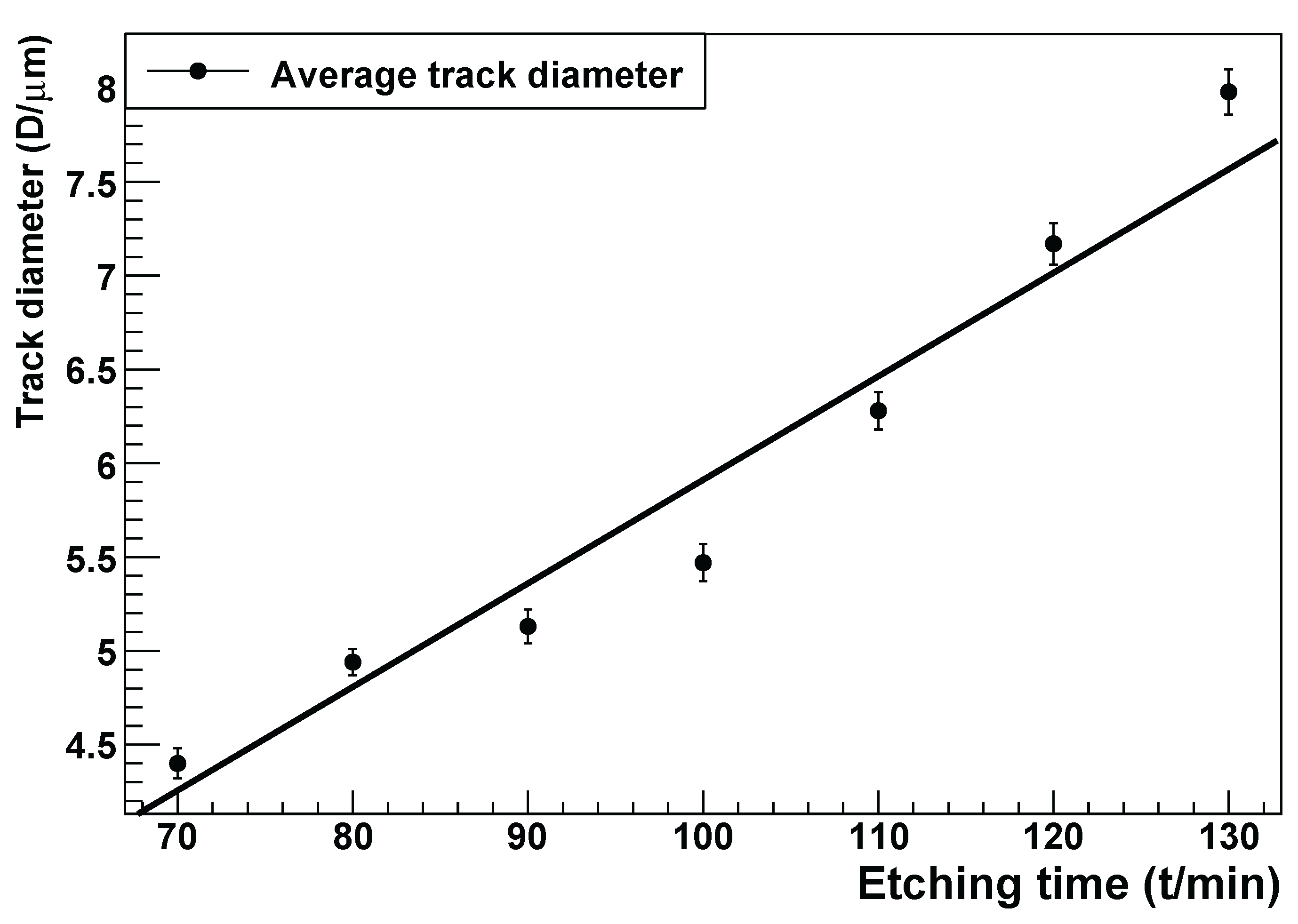

Figure 3 depicts the distribution of the mean track diameter as a function of etching time.

During the etching process, the chemical solution advances along the particle trajectory at the bulk etch rate towards the endpoint E of the track. Initially, the track has a well-defined conical shape (phase 1 of track development). Once the etchant reaches the endpoint, it begins to etch isotropically in all directions, causing the track to transition into an over-etched stage. At this stage, the track geometry is partially conical near the detector surface and partially spherical around the endpoint E (phases 2 and 3 as shown in the inset). With increasing etching time, the conical portion diminishes until the track assumes a fully spherical shape, which occurs for alpha particles incident at or near normal angles.

The least-squares regression of the track diameter as a function of chemical etching time for LR-115 yielded a slope of

µm/h and a y-intercept of

µm, with a correlation coefficient of 0.975, described by the equation

. The slope corresponds to the bulk etch rate (

) and is in good agreement with previous studies: Barillon et al. [

22] reported a bulk etch rate of

µm/h, while Hussain et al. [

26] determined

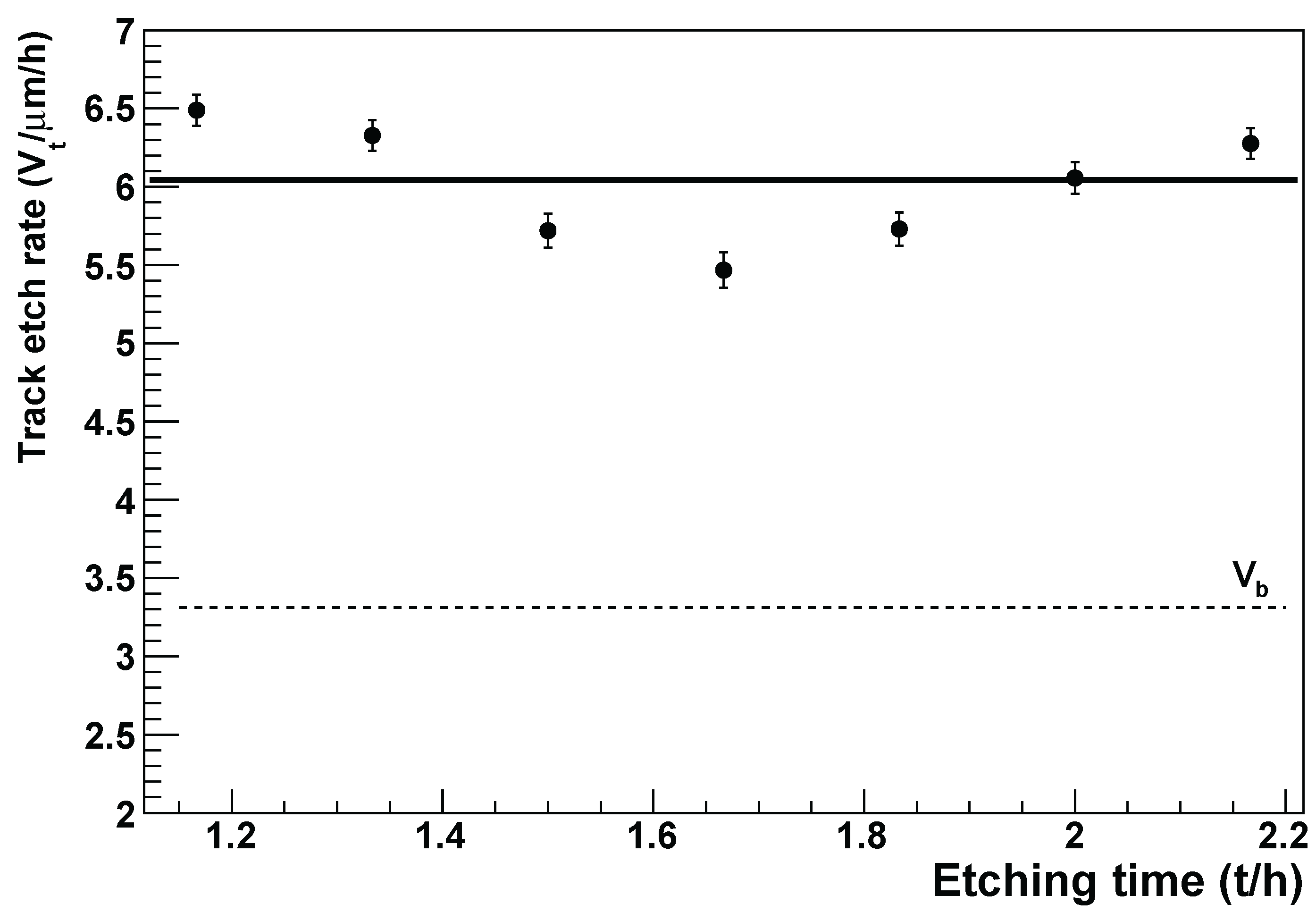

via mass difference measurements before and after etching, obtaining approximately 3.3 µm/h. Regarding the track etch rate (

), our measurements indicate a nearly constant value of

µm/h (see

Figure 4).

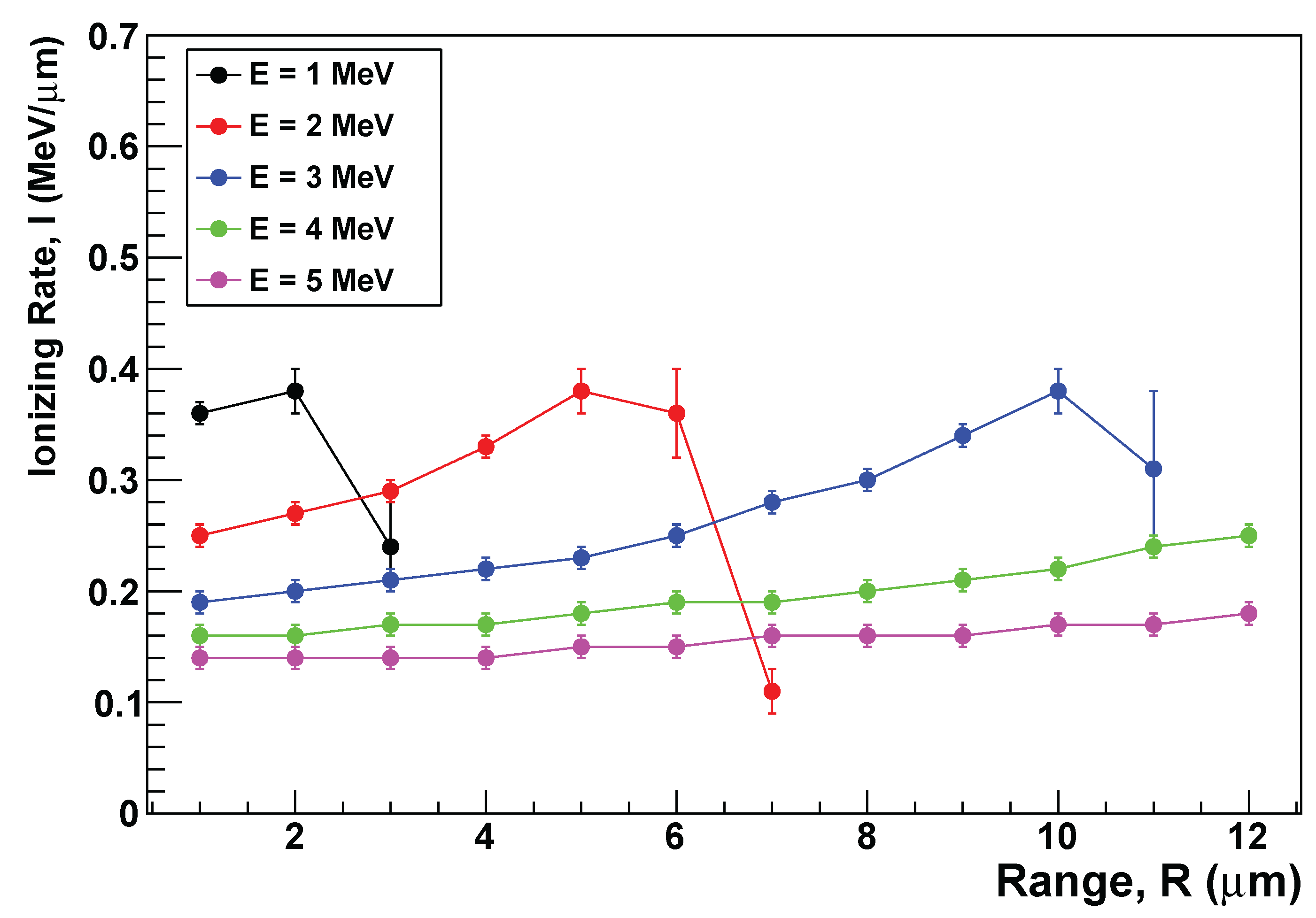

3.2. Numerical Modeling of LR-115 Detector Response to Alpha Particles

The track etch rate

at a specific point

x along the particle trajectory is proportional to the ionization rate

at that point, i.e.,

, where

E is the initial energy of the particle. According to

Figure 5, this rate remains nearly constant for energies up to 5 MeV over approximately 12 µm in the LR-115 detector [

22], which justifies treating

as a constant. The calculated value of

approaches the mean experimental value of 7.2 µm/h reported by [

22] under identical etching conditions. The ionization rate for a 4 MeV alpha particle is estimated at 0.19 MeV/µm, consistent with the value of approximately 0.18 MeV/µm obtained from TRIM (Transport of Ions in Matter) simulations [

27] cited by [

22]. The pronounced peaks observed in the energy distributions for 1, 2, and 3 MeV correspond to the Bragg peak, which occurs near the end of the particle’s path as it comes to rest. This happens because, as the kinetic energy decreases along the trajectory, the interaction cross-section increases, leading to higher ionization rates. At higher energies (close to 5 MeV), the alpha particle moves faster, depositing less energy per unit length, resulting in a lower ionization rate. As the particle slows, the ionization rate rises, reaching a maximum near the end of its range.

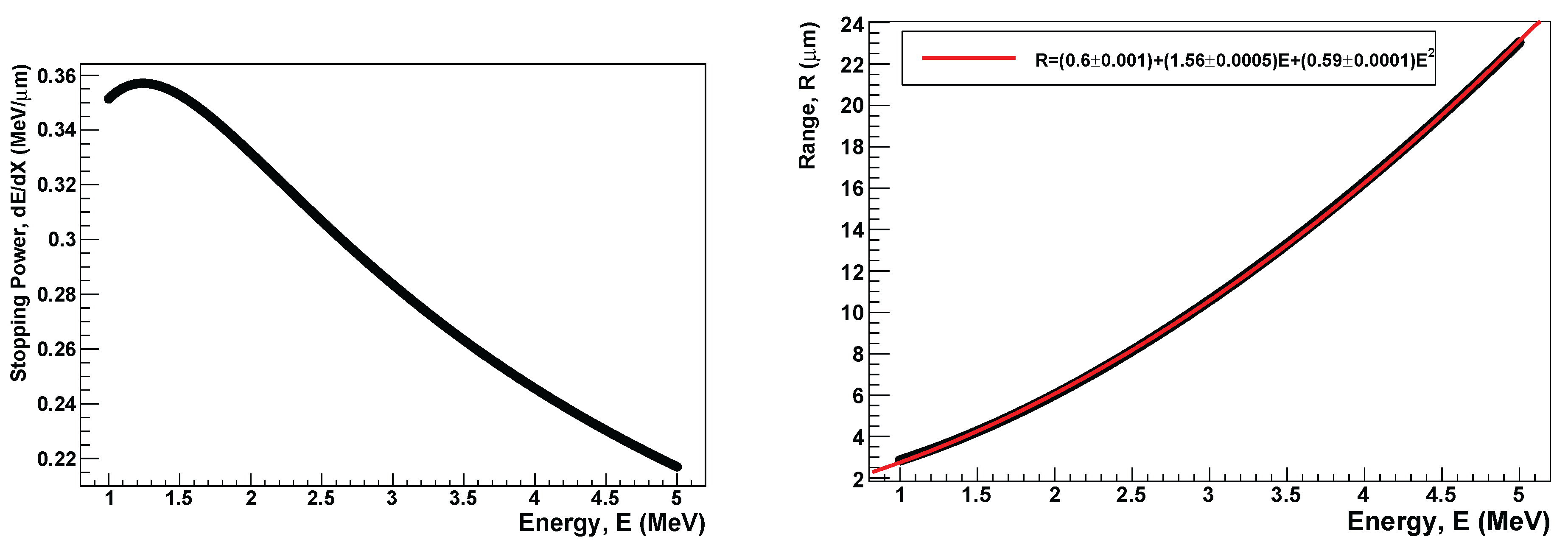

Figure 6 (left panel) displays the average energy deposited by alpha particles in the detector per unit path length, i.e., the linear stopping power (

), as calculated using Geant4. Since the rate of energy loss is inversely proportional to the particle’s energy [

9], lower-energy alpha particles deposit more energy per unit length, resulting in greater damage to the detector material.

Figure 6 (right panel) illustrates the range (

R) of alpha particles as a function of their initial energy (

E). The red solid line represents a quadratic fit to the simulated data.

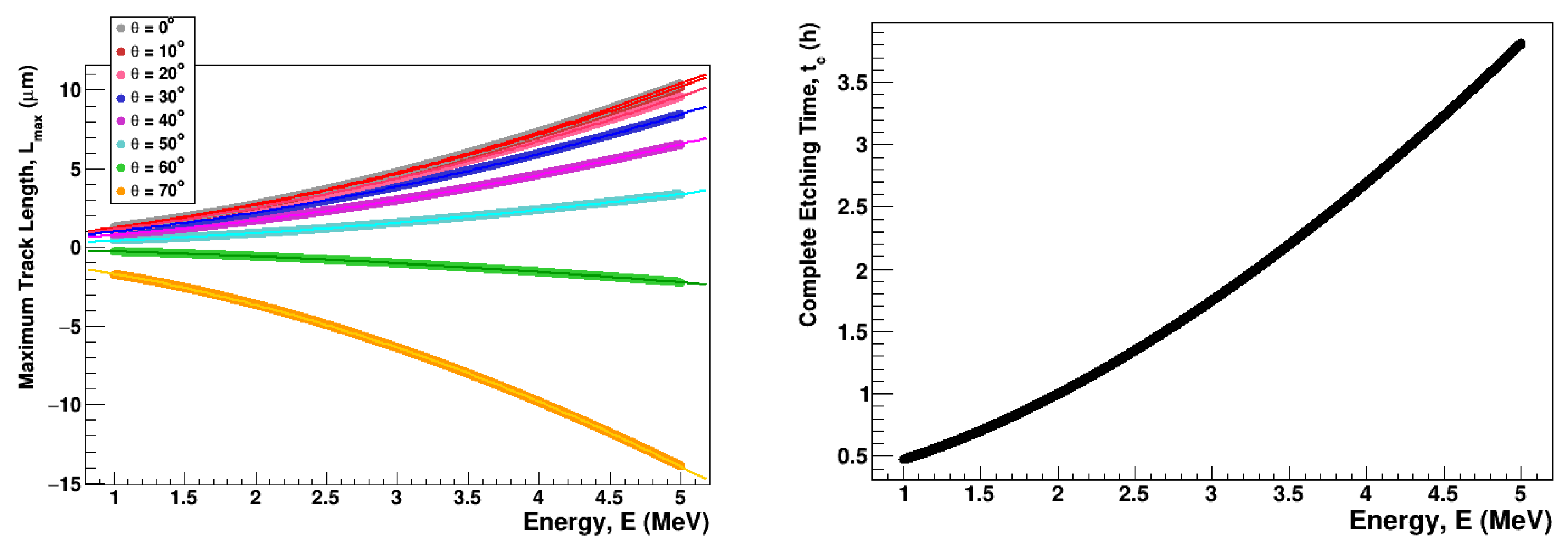

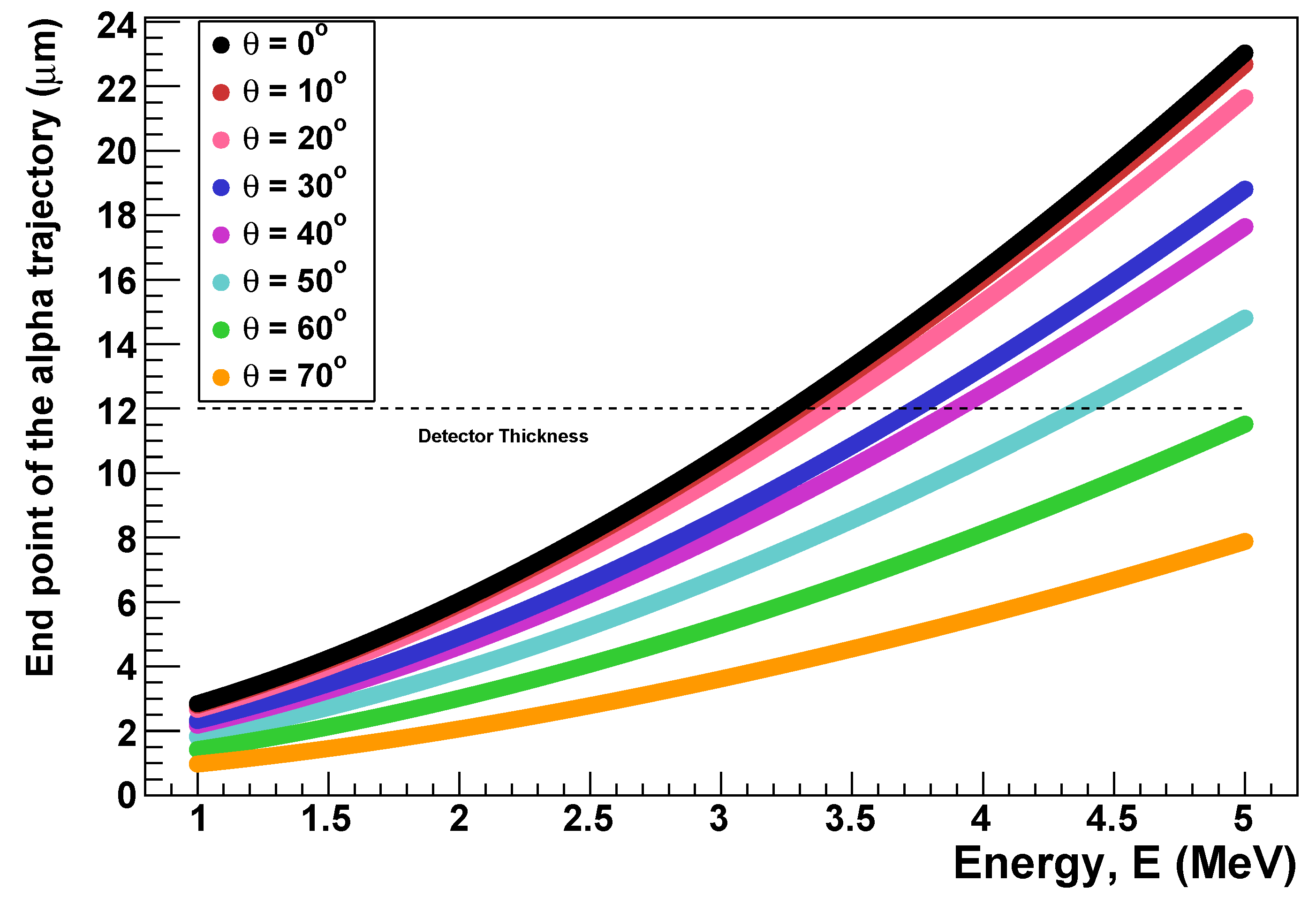

Figure 7 (left panel) shows the parametrization of the maximum track length,

, as a function of the particle energy for different incident angles. The solid lines represent the quadratic regression model fitted to the data, expressed as

The fitting parameters are listed in

Table 1. The estimated critical etching time

as a function of the incident energy is presented in

Figure 7 (right panel). The

distributions indicate that the LR-115 detector is not sensitive to tracks at incident angles greater than 60

.

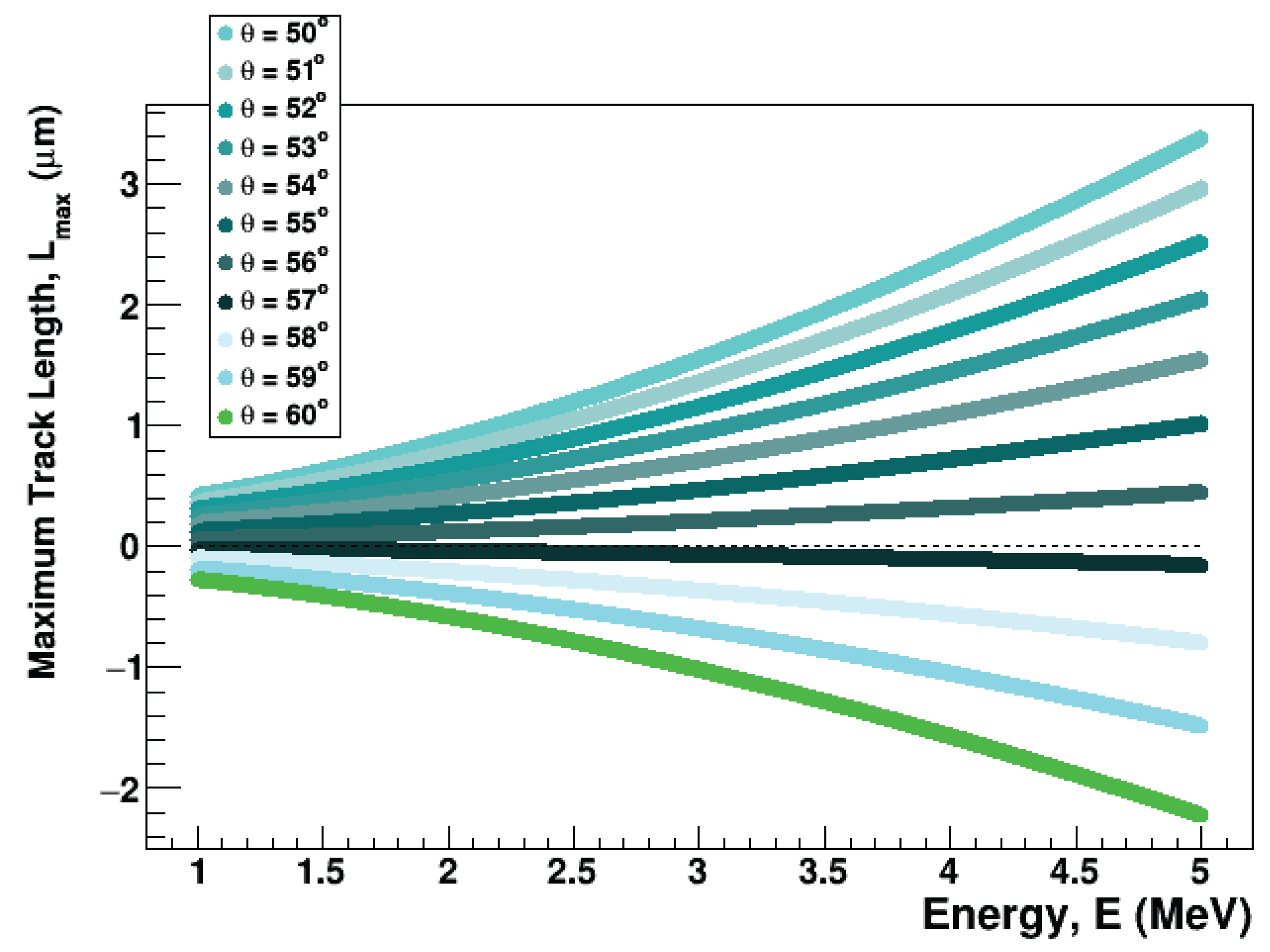

To more precisely determine the critical angle for alpha detection in LR-115 between 50

and 60

, additional simulations were conducted.

Figure 8 depicts the maximum track length as a function of particle energy for incident angles ranging from 50

to 60

. The results show that above approximately 56.5

, the product

lies entirely within the corroded detector layer of thickness

, making track detection impossible.

The critical angle can also be estimated analytically by

which yields a value of 56.7

, in excellent agreement with the Monte Carlo simulation results.

The parameterization of the maximum track length, , offers an alternative and potentially more robust method for estimating the initial energy of alpha particles compared to traditional track diameter measurements. Unlike the track diameter, which often exhibits a non-monotonic and degenerate relationship with particle energy, meaning multiple energy values can correspond to the same diameter, increases monotonically with energy. This monotonic behavior ensures a unique correspondence between the measured maximum track length and the alpha particle’s initial energy, reducing ambiguities in energy determination. Consequently, using as a primary observable can improve the accuracy and reliability of energy reconstruction in applications such as radiation dosimetry and environmental monitoring where precise energy measurements are critical.

Regarding the end point of the alpha particle range within the detector, it is observed that as the incident angle increases, this end point moves closer to the detector surface. This behavior is attributed to the fact that at larger incident angles, the alpha particles traverse a greater effective thickness of detector material, resulting in a shorter penetration depth perpendicular to the surface.

Figure 9 illustrates the track depth as a function of the initial alpha particle energy for various incident angles. Given that the alpha-sensitive film used in this study has a thickness of 12 µm, there exists a maximum energy threshold beyond which the particle range extends beyond the sensitive layer and partially enters the underlying polyester substrate. This threshold is marked by the black dashed line in the figure, which denotes the film thickness boundary.

Considering the full alpha energy range from 1 to 5 MeV, only particles with incident angles up to approximately 50

complete their trajectories entirely within the sensitive layer. Notably, the LR-115 detector loses sensitivity to alpha particles with incident angles greater than 56.5

under the etching conditions used here (2.5 N NaOH at 60.0 ± 0.5

C). For smaller incident angles, a maximum energy limit exists below which the alpha particle’s range remains fully contained within the sensitive film. This energy threshold depends on the incident angle: the smaller the angle, the lower the maximum energy allowed for full containment. The specific values for these limits are summarized in

Table 2.

4. Conclusion

This study characterized the dependence of the maximum etched track length () on alpha-particle energy and incidence angle in LR-115 Type II detectors by combining Geant4 simulations with controlled etching experiments. By measuring and under standardized conditions and linking these to Monte Carlo–based range predictions, we confirmed a critical detection angle of about 56.5. Beyond this angle, latent tracks cannot be revealed because the etched cone lies entirely within the corroded layer.

Our simulations and measurements further established quadratic parameterizations of as functions of both energy and angle. These relations provide a practical alternative to traditional energy–track diameter calibrations, enabling more precise alpha spectrometry. We also determined that the finite 12 µm sensitive layer of LR-115 imposes an upper energy limit for full track containment, which rises from about 3.3 MeV at normal incidence to about 4.4 MeV at 50.

Overall, this work demonstrates that incorporating into LR-115 calibration protocols improves quantitative interpretation of alpha-particle interactions. The results complement existing track-diameter methods, strengthen the basis for radon dosimetry and environmental monitoring, and illustrate the value of Geant4 modeling in refining the response functions of solid-state nuclear track detectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; methodology, Stuani Pereira, L.A. and Sáenz, C.A.T.; software, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; validation, Stuani Pereira, L.A. and Sáenz, C.A.T.; formal analysis, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; investigation, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; resources, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; data curation, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Stuani Pereira, L.A. and Sáenz, C.A.T.; writing—review and editing, Stuani Pereira, L.A and Sáenz, C.A.T.; visualization, Stuani Pereira, L.A. and dSáenz, C.A.T.; project administration, Stuani Pereira, L.A.; funding acquisition, Sáenz, C.A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author thanks the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP N° 2020/02464-8), the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoa de Nível Superior.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest..

References

- Fleischer, R.L. Technological Applications of Ion Tracks in Insulators. MRS Bulletin 1995, 20, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T. Studies on the nuclear tracks in CR-39 plastics. Radiation Measurements 2003, 36, 73–81, Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Nuclear Tracks in Solids. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V.; Singh, S.; Chauhan, R.P.; Mudahar, G. Surface chemical etching behavior of LR-115 type II solid state nuclear track detector: Effects of UV and ultrasonic beam. Optoelectronics and Advanced Materials, Rapid Communications 2014, 8, 943–947. [Google Scholar]

- Misdaq, M. Radon, thoron and their progenies measured in different dwelling rooms and reference atmospheres by using CR-39 and LR-115 SSNTD. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2003, 59, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasino, L. Detectors/Dosemeters of galactic and solar cosmic rays. Radiation protection dosimetry 2004, 109, 365–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; O’Sullivan, D.; Semones, E.; Zapp, N.; Benton, E. Research on sensitivity fading of CR-39 detectors during long time exposure. Radiation Measurements 2009, 44, 909–912, Proceedings of the 24th International Conferenceon Nuclear Tracks in Solids. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Walia, V.; Mogili, S.; Fu, C.C. Improved semi automatic approach to count the tracks on LR-115 film for monitoring of radioactive elements. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2021, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesby, A. Atomic Radiation and Polymers, 1st ed.; International Series of Monographs on Radiation Effects in Materials; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, R.L.; Price, P.B.; Walker, R.M. Nuclear Tracks in Solids: Principles and Applications; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, N.; Hafez, A.F. Studying the Physical Parameters of a Solid State Nuclear Track Detector. Journal of Korean Physical Society 2013, 63, 1713–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikezic, D.; Yu, P. Formation and growth of tracks in nuclear track materials. Materials Science & Engineering R-reports - MAT SCI ENG R 2004, 46, 51–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrani, S.A.; Bull, R.K. Solid State Nuclear Track Detection: Principles, Methods and Applications; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Yerimbetova, D.S.; Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Tuichiyev, U.N.; Zhumadilov, K.S. Study of the Sensitivity Limit of Detection of α-Particles by Polymer Film Detectors LR-115 Type 2 Using X-ray Diffraction and UV-Vis Spectroscopic Methods. Polymers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereyra, P.; Guevara-Pillaca, C.J.; Liza, R.; Pérez, B.; Rojas, J.; Vilcapoma L., L.; Gonzales, S.; Sajo-Bohus, L.; López-Herrera, M.E.; Palacios Fernández, D. Estimation of Indoor 222Rn Concentration in Lima, Peru Using LR-115 Nuclear Track Detectors Exposed in Different Modes. Atmosphere 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Verde, G.; Ambrosino, F.; Ragosta, M.; Pugliese, M. Results of Indoor Radon Measurements in Campania Schools Carried Out by Students of an Italian Outreach Project. Applied Sciences 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressyanov, D.; Dimitrov, D. Fine-Scale Spatial Distribution of Indoor Radon and Identification of Potential Ingress Pathways. Atmosphere 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinelli, S.; et al. Geant4—a simulation toolkit. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2003, 506, 250–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, J.; et al. Recent developments in Geant4. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2016, 835, 186–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mheemeed, A.K.; Hussein, A.K.; Kheder, R.B. Characterization of alpha-particle tracks in cellulose nitrate LR-115 detectors at various incident energies and angles. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2013, 79, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jubbori, M.A. Empirical model of alpha particle track length in CR-39 detector. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2017, 871, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, S.; Kolekar, R.; Sunil, C.; Sarkar, P.; Dwivedi, K.; Sharma, D. Microwave-induced chemical etching (MCE): A fast etching technique for the solid polymeric track detectors (SPTD). Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2010, 612, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barillon, R.; Fromm, M.; Chambaudet, A.; Marah, H.; Sabir, A. Track etch velocity study in a radon detector (LR 115, cellulose nitrate). Radiation Measurements 1997, 28, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuani Pereira, L.A.; Candido de Azevedo, M.; Nakasuga, W.M.; Figueroa, P.; Tello Sáenz, C.A. Fission-track evolution in Macusanite volcanic glass. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2020, 176, 109076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermsdorf, D.; Hunger, M. Determination of track etch rates from wall profiles of particle tracks etched in direct and reversed direction in PADC CR-39 SSNTDs. Radiation Measurements 2009, 44, 766–774, Proceedings of the 24th International Conferenceon Nuclear Tracks in Solids. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S. A New Treatment to Compute the Track Parameters in PADC Detector using Track Opening Measurement. Journal of Physical Science 2018, 29, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A. Variation of Bulk Etch Rate and some other Etching Parameters with Etching Temperature for Cellulose Nitrate LR-115 Detector. JOURNAL OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE 2009, 22, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Yang, Q.; Chen, X.; Yang, J. Fast Calculation of Mont Carlo Ion Transport Code. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2021, 1739, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).