Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. System Boundaries and Purposes

- A – Methodological Development and Standardization of MFA

- B – National and Regional Wood Flow Analyses

- C – Climate Change Mitigation and Carbon Accounting

- D – Resource Efficiency, Circularity, and Cascading Use

- E – Policy Support, Strategic Planning, and Socioeconomic Implications

3.2. Data Processing

3.3. Outputs and Applications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe – Strengthening the Connection between Economy, Society and the Environment – Updated Bioeconomy Strategy; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Communication. The European Green Deal – Delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Targets; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, P.H.; Rechberger, H. Practical Handbook of Material Flow Analysis, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, A.H.; Levine, S.B. Wood-based building materials and atmospheric carbon emissions. Environ. Sci. Policy 1999, 2, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, L. A. J.; Hekkert, M. P.; Worrell, E.; Turkenburg, W. C. STREAMS: A new method for analysing material flows through society. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 1999, 27, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.; Cunha, J.; De Meyer, A.; Navare, K. Contribution Towards a Comprehensive Methodology for Wood-Based Biomass Material Flow Analysis in a Circular Economy Setting. Forests 2020, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džubur, N.; Sunanta, O.; Laner, D. A Fuzzy Set-Based Approach to Data Reconciliation in Material Flow Modeling. Appl. Math. Model. 2017, 43, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džubur, N.; Laner, D. Evaluation of Modeling Approaches to Determine End-of-Life Flows Associated with Buildings: A Viennese Case Study on Wood and Contaminants. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 22, 1156–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalcher, J.; Praxmarer, G.; Teischinger, A. Quantification of Future Availabilities of Recovered Wood from Austrian Residential Buildings. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 123, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalt, G. Biomass Streams in Austria: Drawing a Complete Picture of Biogenic Material Flows within the National Economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 95, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, F.C. Assessment of the Coherence of the Swiss Waste Wood Management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 91, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, F.C. Energy and Climate Impact Assessment of Waste Wood Recovery in Switzerland. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 94, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehr, J.; Vadenbo, C.; Steubing, B.; Hellweg, S. Environmentally Optimal Wood Use in Switzerland—Investigating the Relevance of Material Cascades. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 131, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, F.; Steubing, B.; Hellweg, S. Life Cycle Impacts and Benefits of Wood along the Value Chain: The Case of Switzerland. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 874–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinevičius, G.; Lindner, M.; Cienciala, E.; Tykkyläinen, M. Carbon Accounting in Harvested Wood Products: Assessment Using Material Flow Analysis Resulting in Larger Pools Compared to the IPCC Default Method. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 22, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bösch, M.; Jochem, D.; Weimar, H.; Dieter, M. Physical Input–Output Accounting of the Wood and Paper Flow in Germany. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 94, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, M.; Poganietz, W.-R.; Schebek, L. Anthropogenic Carbon Stock Dynamics of Pulp and Paper Products in Germany. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egenolf, V.; Vita, G.; Distelkamp, M.; Schier, F.; Hüfner, R.; Bringezu, S. The Timber Footprint of the German Bioeconomy—State of the Art and Past Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochem, D.; Weimar, H.; Bösch, M.; Mantau, U.; Dieter, M. Estimation of Wood Removals and Fellings in Germany: A Calculation Approach Based on the Amount of Used Roundwood. Eur. J. For. Res. 2015, 134, 869–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauf, M. An Analysis of Wood Market Balance Modeling in Germany. Forest Policy and Economics 2015, 50, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauf, M. The Wood Market Balance as a Tool for Calculating Wood Use's Climate Change Mitigation Effect — An Example for Germany. Forest Policy and Economics 2016, 66, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweinle, J.; Geng, N.; Iost, S.; Weimar, H.; Jochem, D. Monitoring Sustainability Effects of the Bioeconomy: A Material Flow Based Approach Using the Example of Softwood Lumber and Its Core Product Epal 1 Pallet. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szarka, N.; Haufe, H.; Lange, N.; Schier, F.; Weimar, H.; Banse, M.; Sturm, V.; Dammer, L.; Piotrowski, S.; Thrän, D. Biomass Flow in Bioeconomy: Overview for Germany. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 150, 111449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szichta, P.; Risse, M.; Weber-Blaschke, G.; Richter, K. Potentials for wood cascading: A model for the prediction of the recovery of timber in Germany. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 178, 106101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskhiri, M.S.; Garbs, M.; Geldermann, J. Sustainable logistics network for wood flow considering cascade utilisation. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 110, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

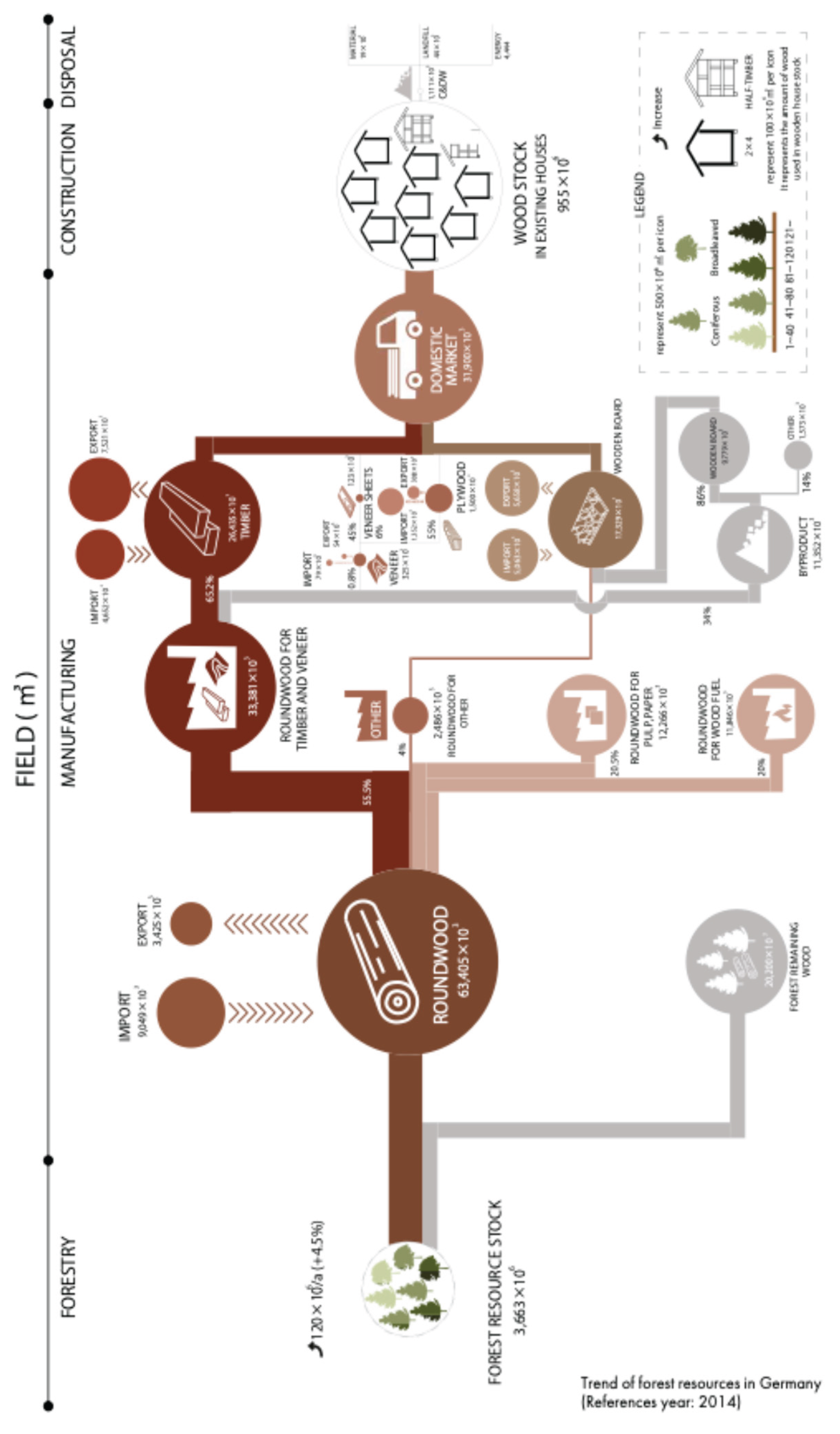

- Wang, R.; Haller, P. Dynamic material flow analysis of wood in Germany from 1991 to 2020. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 201, 107339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownell, H.; Iliev, B.E.; Bentsen, N.S. How much wood do we use and how do we use it? Estimating Danish wood flows, circularity, and cascading using national material flow accounts. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 423, 138720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.K.; Villa, A.; Kuittinen, S.; Jänis, J.; Pappinen, A. An assessment of side-stream generation from Finnish forest industry. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2019, 21, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, B.; Piccardo, C.; Hughes, M. Estimating the material stock in wooden residential houses in Finland. Waste Manag. 2021, 135, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, R.J.; Horta Arduin, R.; Yazdeen, H.; Pommier, R.; Sonnemann, G. Material Flow Analysis to Evaluate Supply Chain Evolution and Management: An Example Focused on Maritime Pine in the Landes de Gascogne Forest, France. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenglet, J.; Courtonne, J.-Y.; Caurla, S. Material flow analysis of the forest-wood supply chain: a consequential approach for log export policies in France. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polgár, A. Carbon footprint and sustainability assessment of wood utilisation in Hungary. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 24495–24519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlan, J.; Skog, K.E.; Byrne, K.A. Carbon storage in harvested wood products for Ireland 1961–2009. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 46, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekkert, M.P.; Joosten, L.A.J.; Worrell, E. Analysis of the paper and wood flow in The Netherlands. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2000, 30, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Freire, F.; Garcia, R. Material flow analysis of forest biomass in Portugal to support a circular bioeconomy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169, 105507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piškur, M.; Krajnc, N. Roundwood flow analysis in Slovenia. Croj. J. For. Eng. 2007, 28, 39–46. Available online: https://crojfe.com/site/assets/files/3901/piskur39-46.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Gejdoš, M.; Danihelová, Z. Valuation and timber market in the Slovak Republic. Procedia Econ. Finance 2015, 34, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parobek, J.; Paluš, H.; Kaputa, V.; Šupín, M. Modelling of wood and wood products flow in the Slovak Republic. In A European Wood Processing Strategy: Future Resources Matching Products and Innovations; COST Action E44 Conference, Ghent, Belgium, 2008, p. 93. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285288571_Modelling_of_wood_and_wood_products_flow_in_the_Slovak_Republic (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Parobek, J.; Paluš, H.; Kaputa, V.; Šupín, M. Analysis of wood flows in Slovakia. BioResources 2014, 9, 6453–6462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parobek, J.; Paluš, H. Material flows in primary wood processing in Slovakia. Acta Logistica 2016, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais-Moleman, A.; Sikkema, R.; Vis, M.; Reumerman, P.; Theurl, M.; Erb, K.-H. Assessing wood use efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions of wood product cascading in the European Union. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3942–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantau, U.; Saal, U.; Steierer, F.; Verkerk, H.; Lindner, M.; Anttila, P.; Asikainen, A.; Oldenburger, J.; Leek, N.; Eggers, J.; Prins, K.; Leek, N. EUwood – Real potential for changes in growth and use of EU forests. Final report; Hamburg, Germany, June 2010; 160 p. Available online: https://www.probos.nl/images/pdf/rapporten/Rap2010_Real_potential_for_changes_in_growth_and_use_of_EU_forests.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Mantau, U. Wood flows in Europe (EU 27). Project report; INFRO e.K.: Celle, Germany, 2012; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291034739_Wood_flows_in_Europe_EU_27 (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Mantau, U. Wood flow analysis: Quantification of resource potentials, cascades and carbon effects. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 79, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilli, R.; Fiorese, G.; Grassi, G. EU mitigation potential of harvested wood products. Carbon Balance Manag. 2015, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saal, U.; Iost, S.; Weimar, H. Supply of wood processing residues – a basic calculation approach and its application on the example of wood packaging. Trees Forests People 2022, 7, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikkema, R.; Styles, D.; Jonsson, R.; Tobin, B.; Byrne, K.A. A market inventory of construction wood for residential building in Europe – in the light of the Green Deal and new circular economy ambitions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 90, 104370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAO Yearbook of Forest Products 2020; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/6fdc429f-1d35-428d-bcde-326070d6d3ad (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: http://www.fao.org (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Wang, H.; Takano, A.; Tamura, K. An attempt to create the holistic flow chart of forest resources. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 588, 042039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Country | First Author | Year | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AT | Džubur | 2017 | A fuzzy set-based approach to data reconciliation in material flow modeling [7] |

| 2 | AT | Džubur | 2018 | Evaluation of modeling approaches to determine end-of-life flows associated with buildings: A Viennese case study on wood and contaminants [8] |

| 3 | AT | Kalcher | 2017 | Quantification of future availabilities of recovered wood from Austrian residential buildings [9] |

| 4 | AT | Kalt | 2015 | Biomass streams in Austria: Drawing a complete picture of biogenic material flows within the national economy [10] |

| 5 | CH | Bergeron | 2014 | Assessment of the coherence of the Swiss waste wood management [11] |

| 6 | CH | Bergeron | 2016 | Energy and climate impact assessment of waste wood recovery in Switzerland [12] |

| 7 | CH | Mehr | 2018 | Environmentally optimal wood use in Switzerland—Investigating the relevance of material cascades [13] |

| 8 | CH | Suter | 2017 | Life cycle impacts and benefits of wood along the value chain [14] |

| 9 | CZ | Jasinevičius | 2018 | Carbon accounting in harvested wood products: Assessment using material flow analysis resulting in larger pools compared to the IPCC default method [15] |

| 10 | DE | Bösch | 2015 | Physical input-output accounting of the wood and paper flow in Germany [16] |

| 11 | DE | Cote | 2015 | Anthropogenic carbon stock dynamics of pulp and paper products in Germany [17] |

| 12 | DE | Egenolf | 2021 | The timber footprint of the German bioeconomy—State of the art and past development [18] |

| 13 | DE | Jochem | 2015 | Estimation of wood removals and fellings in Germany: A calculation approach based on the amount of used roundwood [19] |

| 14 | DE | Knauf | 2015 | An analysis of wood market balance modeling in Germany [20] |

| 15 | DE | Knauf | 2016 | The wood market balance as a tool for calculating wood use's climate change mitigation effect—An example for Germany [21] |

| 16 | DE | Schweinle | 2020 | Monitoring sustainability effects of the bioeconomy: A material flow based approach using the example of softwood lumber and its core product epal 1 pallet [22] |

| 17 | DE | Szarka | 2021 | Biomass flow in bioeconomy: Overview for Germany [23] |

| 18 | DE | Szichta | 2022 | Potentials for wood cascading: A model for the prediction of the recovery of timber in Germany [24] |

| 19 | DE | Taskhiri | 2016 | Sustainable logistics network for wood flow considering cascade utilisation [25] |

| 20 | DE | Wang | 2024 | Dynamic material flow analysis of wood in Germany from 1991 to 2020 [26] |

| 21 | DK | Brownnell | 2023 | How much wood do we use and how do we use it? Estimating Danish wood flows, circularity, and cascading using national material flow accounts [27] |

| 22 | FI | Hassan | 2018 | An assessment of side-stream generation from Finnish forest industry [28] |

| 23 | FI | Nasiri | 2021 | Estimating the material stock in wooden residential houses in Finland [29] |

| 24 | FR | Layton | 2021 | Material flow analysis to evaluate supply chain evolution and management: An example focused on maritime pine in the Landes de Gascogne forest, France [30] |

| 25 | FR | Lenglet | 2017 | Material flow analysis of the forest-wood supply chain: A consequential approach for log export policies in France [31] |

| 26 | HU | Polgár | 2023 | Carbon footprint and sustainability assessment of wood utilisation in Hungary [32] |

| 27 | IE | Donlan | 2012 | Carbon storage in harvested wood products for Ireland 1961-2009 [33] |

| 28 | NT | Hekkert | 2000 | Analysis of the paper and wood flow in The Netherlands [34] |

| 29 | PT | Gonçalves | 2021 | Material flow analysis of forest biomass in Portugal to support a circular bioeconomy [35] |

| 30 | PT | Marques | 2020 | Contribution towards a comprehensive methodology for wood-based biomass material flow analysis in a circular economy setting [6] |

| 31 | SI | Piškur | 2007 | Roundwood flow analysis in Slovenia [36] |

| 32 | SK | Gejdoš | 2015 | Valuation and timber market in the Slovak Republic [37] |

| 33 | SK | Parobek | 2008 | Modelling of wood and wood products flow in the Slovak Republic [38] |

| 34 | SK | Parobek | 2014 | Analysis of Wood Flows in Slovakia [39] |

| 35 | SK | Parobek | 2016 | Material flows in primary wood processing in Slovakia [40] |

| 36 | EU | Bais-Moleman | 2018 | Assessing wood use efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions of wood product cascading in the European Union [41] |

| 37 | EU | Mantau | 2010 | EUwood—Real potential for changes in growth and use of EU forests. Final report [42] |

| 38 | EU | Mantau | 2012 | Wood flows in Europe [43] |

| 39 | EU | Mantau | 2015 | Wood flow analysis: Quantification of resource potentials, cascades and carbon effects [44] |

| 40 | EU | Pilli | 2015 | EU mitigation potential of harvested wood products [45] |

| 41 | EU | Saal | 2022 | Supply of wood processing residues—A basic calculation approach and its application on the example of wood packaging [46] |

| 42 | EU | Sikkema | 2023 | A market inventory of construction wood for residential building in Europe: In the light of the Green Deal and new circular economy ambitions [47] |

| Evaluation Criterion | Purpose | Specific Aspects Analyzed |

|---|---|---|

| Geographical and temporal coverage | Understand spatial and historical scope of studies | Countries or regions covered, temporal range |

| System boundaries | Clarify purposes and completeness of material flow systems | Inclusion of forest resources, processing stages, product use, end-of-life |

| Data sources and quality | Assess transparency, reliability, and comparability of data | Data sources, unit consistency, conversion factors, estimation methods, treatment of gaps |

| Flow representation techniques | Evaluate clarity and comprehensiveness | Use of diagrams, flow charts, tables; level of detail and consistency in visualization |

| Treatment of uncertainty | Identify methodological validity and transparency | Presence of sensitivity analysis, handling of uncertainties, documentation of assumptions, reconciliation steps |

| No | Stage-I | Stage-II | Stage-III | Stage-IV | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forestry | Manufacturing | Building | End-of-Life | ||

| 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | A |

| 2 | Yes | C | |||

| 3 | Yes | B | |||

| 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | B | |

| 5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | D |

| 6 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | C |

| 7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | D |

| 8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | E | |

| 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | C |

| 10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | A |

| 11 | Yes | Yes | A | ||

| 12 | Yes | Yes | D | ||

| 13 | Yes | Yes | A | ||

| 14 | Yes | Yes | Yes | A | |

| 15 | Yes | Yes | Yes | C | |

| 16 | Yes | Yes | Yes | D | |

| 17 | Yes | Yes | D | ||

| 18 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | B |

| 19 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | D |

| 20 | Yes | Yes | Yes | B | |

| 21 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | B |

| 22 | Yes | Yes | D | ||

| 23 | Yes | D | |||

| 24 | Yes | B | |||

| 25 | Yes | Yes | Yes | E | |

| 26 | Yes | Yes | C | ||

| 27 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | C |

| 28 | Yes | Yes | Yes | A | |

| 29 | Yes | Yes | B | ||

| 30 | Yes | Yes | Yes | A | |

| 31 | Yes | Yes | Yes | E | |

| 32 | Yes | D | |||

| 33 | Yes | Yes | E | ||

| 34 | Yes | Yes | B | ||

| 35 | Yes | Yes | B | ||

| 36 | Yes | Yes | Yes | D | |

| 37 | Yes | Yes | Yes | E | |

| 38 | Yes | Yes | Yes | B | |

| 39 | Yes | Yes | Yes | A | |

| 40 | Yes | C | |||

| 41 | Yes | Yes | A | ||

| 42 | Yes | Yes | E |

| No | Unit symbol | Unit name | Quantity type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | t / t dry matter | tonnes of dry wood / matter | mass |

| 2 | t | metric tonne | mass |

| 3 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 4 | Mtdry | million tonnes of dry mass | mass |

| 5 | Mt | megatons | mass |

| 6 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 7 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 8 | m3 solid wood | cubic meter solid wood equivalent | volume |

| 9 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 10 | m3(f) | (cubic meter) wood fiber equivalent | volume |

| 11 | Mt | million metric tons | mass |

| 12 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 13 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 14 | Mm³ | million cubic meters | volume |

| 15 | Mm³ | million cubic meters | volume |

| 16 | t | metric ton | mass |

| 17 | tDM | tons of dry matter | mass |

| 18 | m³ SWE | volume of solid wood equivalents | volume |

| 19 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 20 | SWE | solid wood equivalent | volume |

| 21 | m3 SWE | cubic meter solid wood equivalent | volume |

| 22 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 23 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 24 | m3 [f] | wood fiber equivalent | volume |

| 25 | m3 [f] | wood fiber equivalent | volume |

| 26 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 27 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 28 | kt | kiloton / kilotonne | mass |

| 29 | m3(f) | cubic meter of wood fiber equivalent | volume |

| 30 | kton | kiloton | mass |

| 31 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 32 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 33 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 34 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 35 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 36 | tonne | tonne wet weight woody raw material | mass |

| 37 | m³ rwe | roundwood equivalent | volume |

| 38 | m³ swe | solid wood equivalent | volume |

| 39 | m³ swe | solid wood equivalent | volume |

| 40 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

| 41 | m3f | wood fiber equivalent | volume |

| 42 | m³ | cubic meter | volume |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).