Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

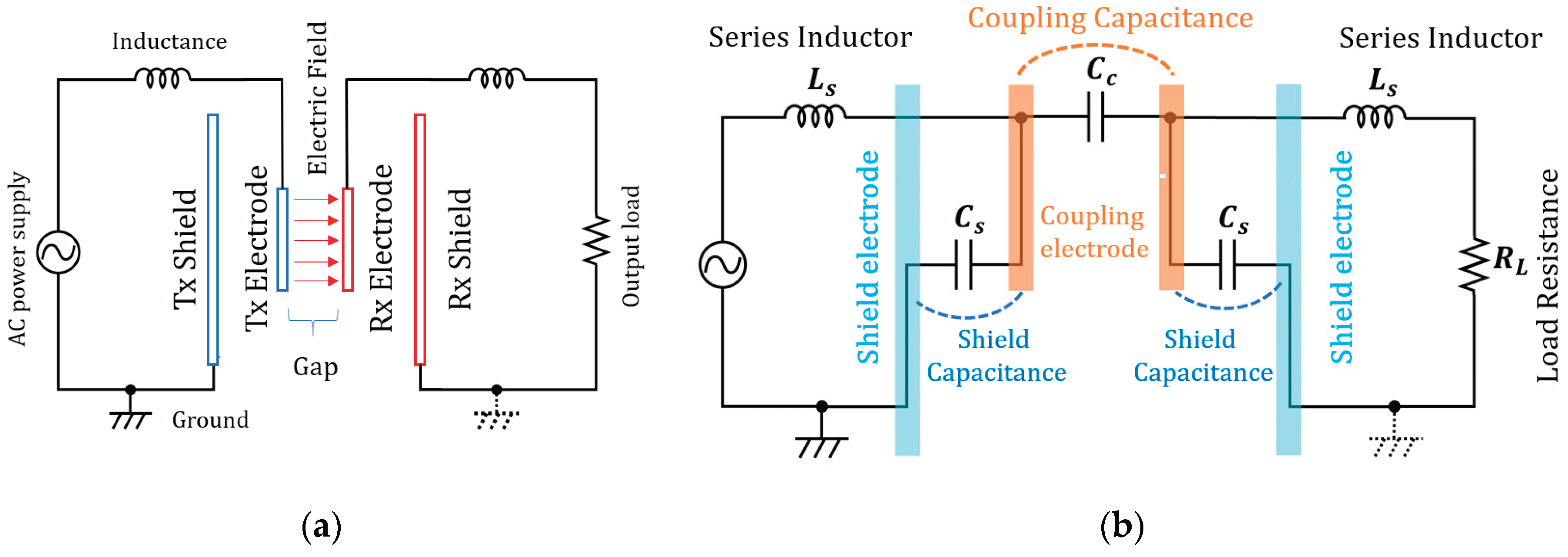

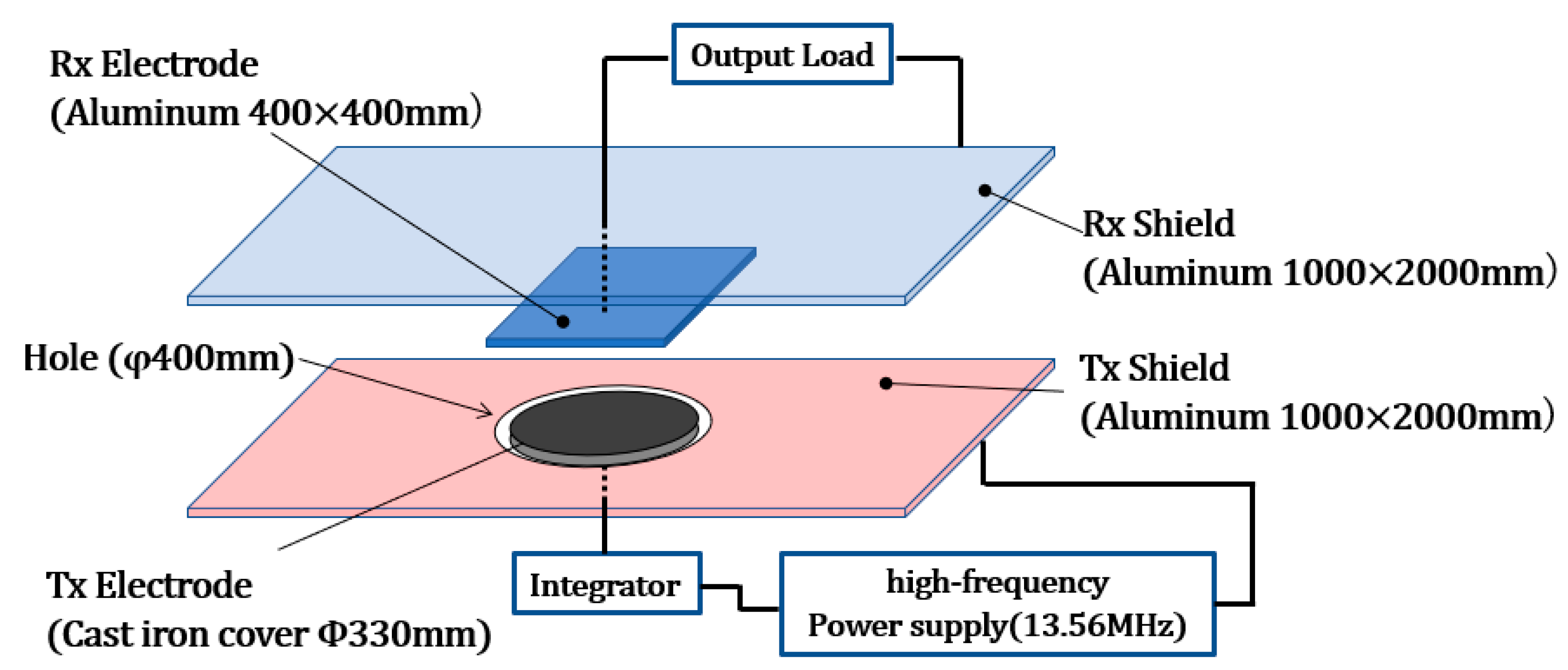

2. S-CPT (Shielded Capacitive Power Transfer)

2.1. S-CPT (Shilded Capacitive Power Transfer)

3. Electrode Material Property Evaluation

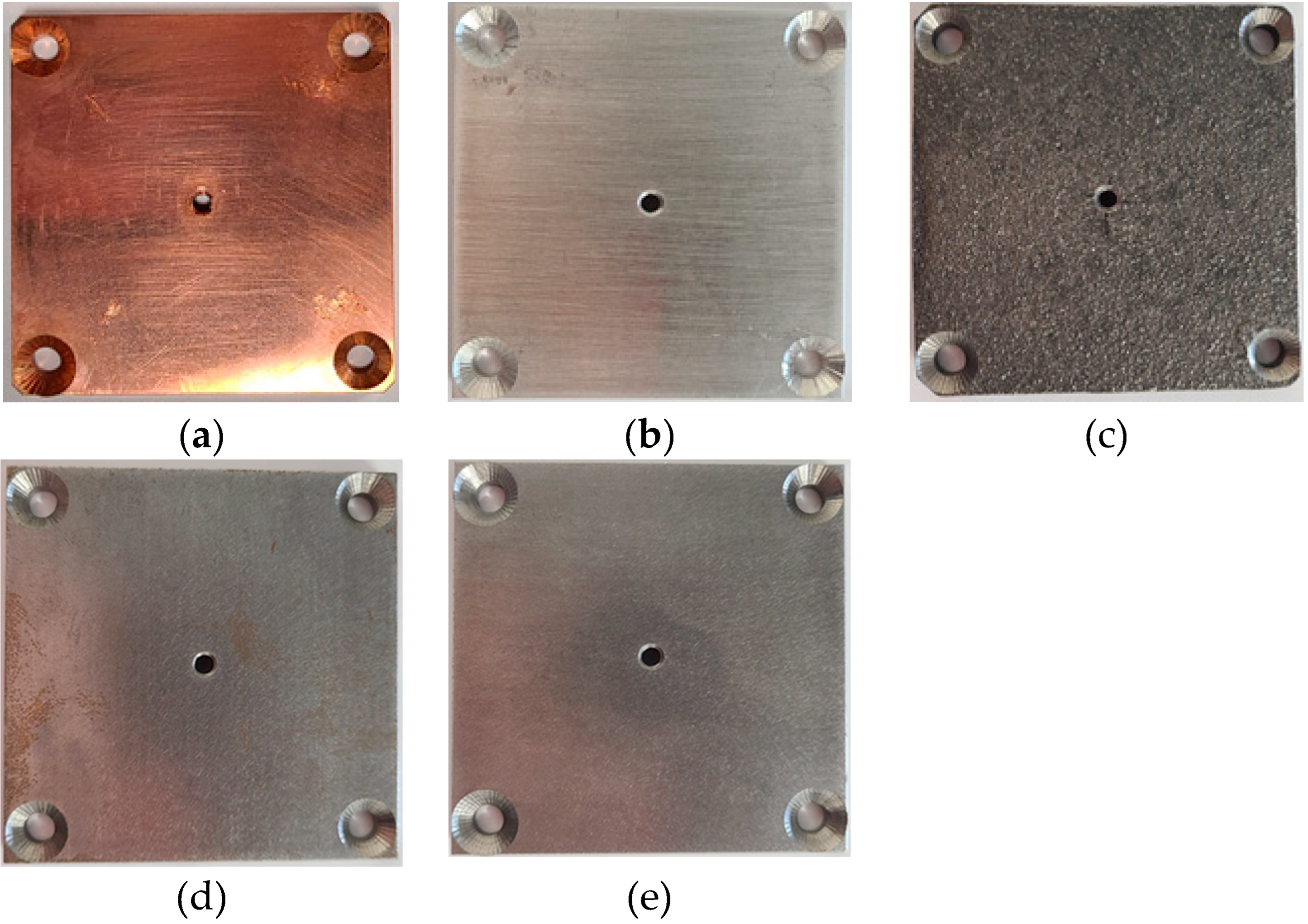

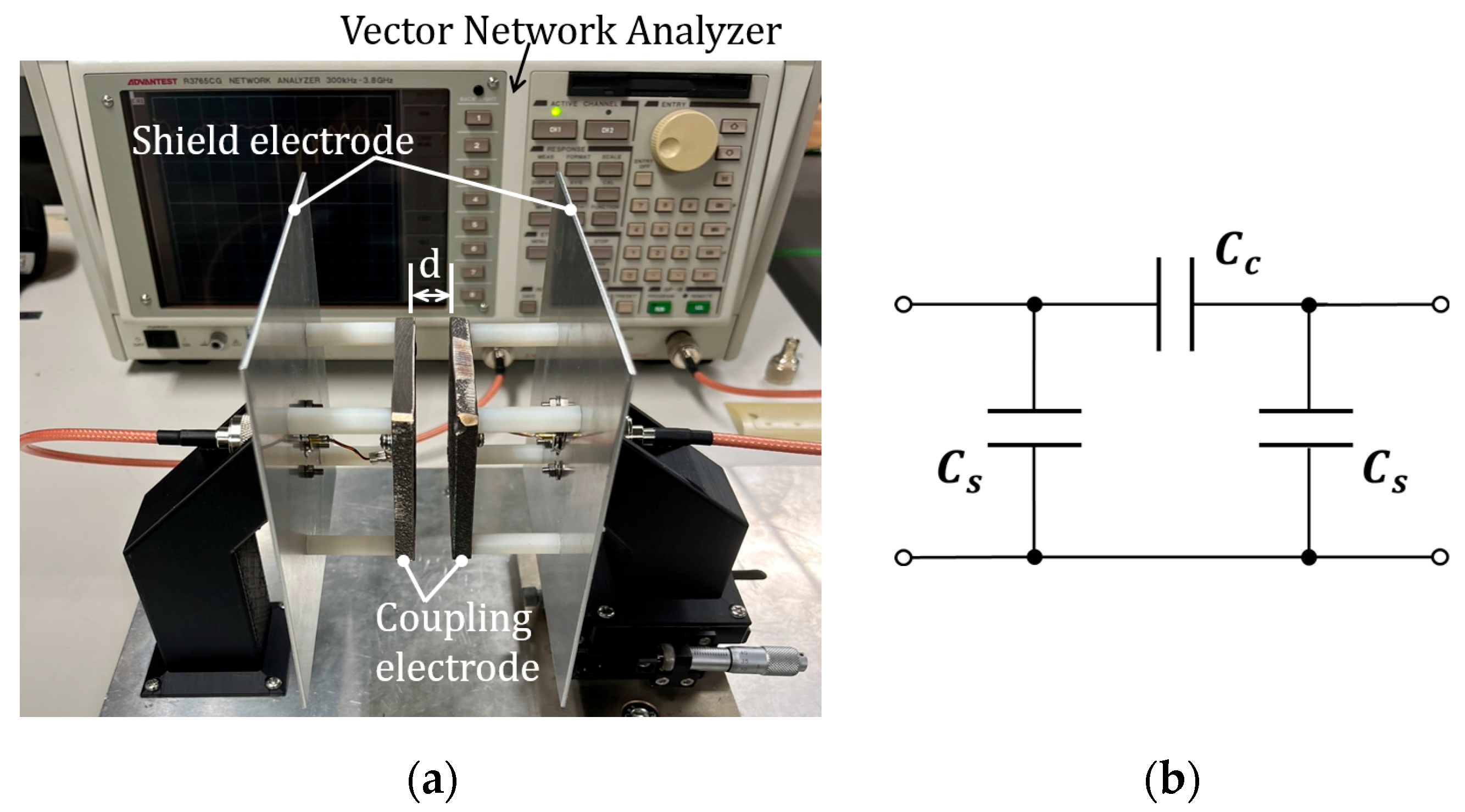

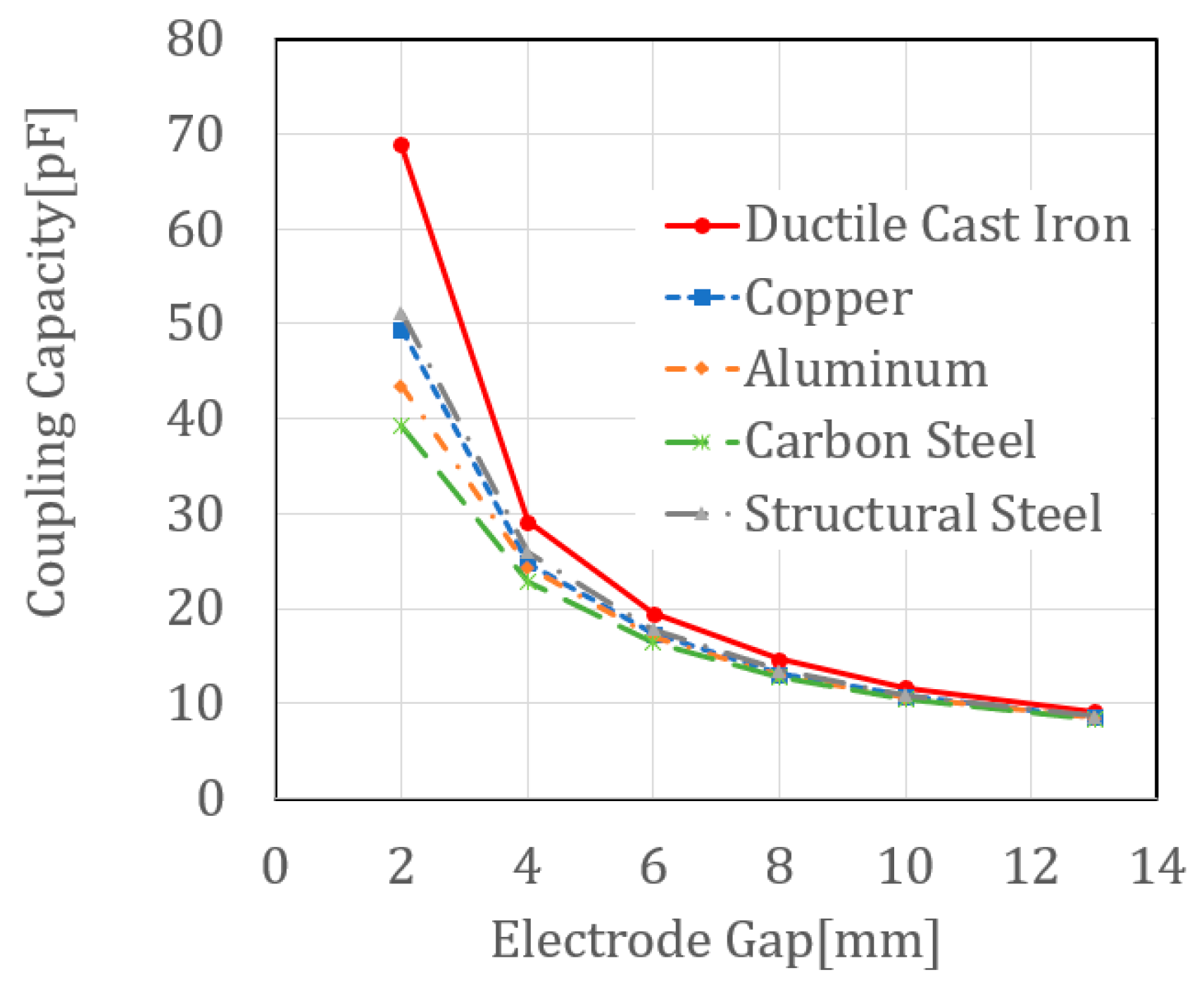

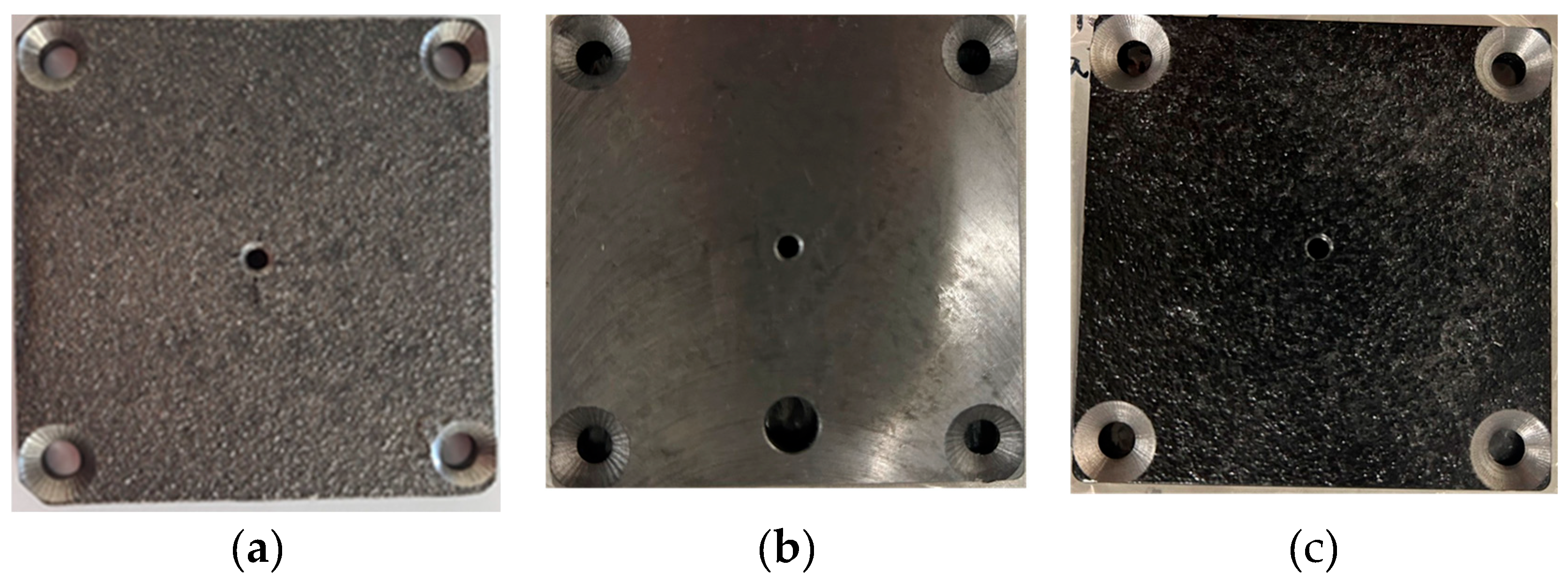

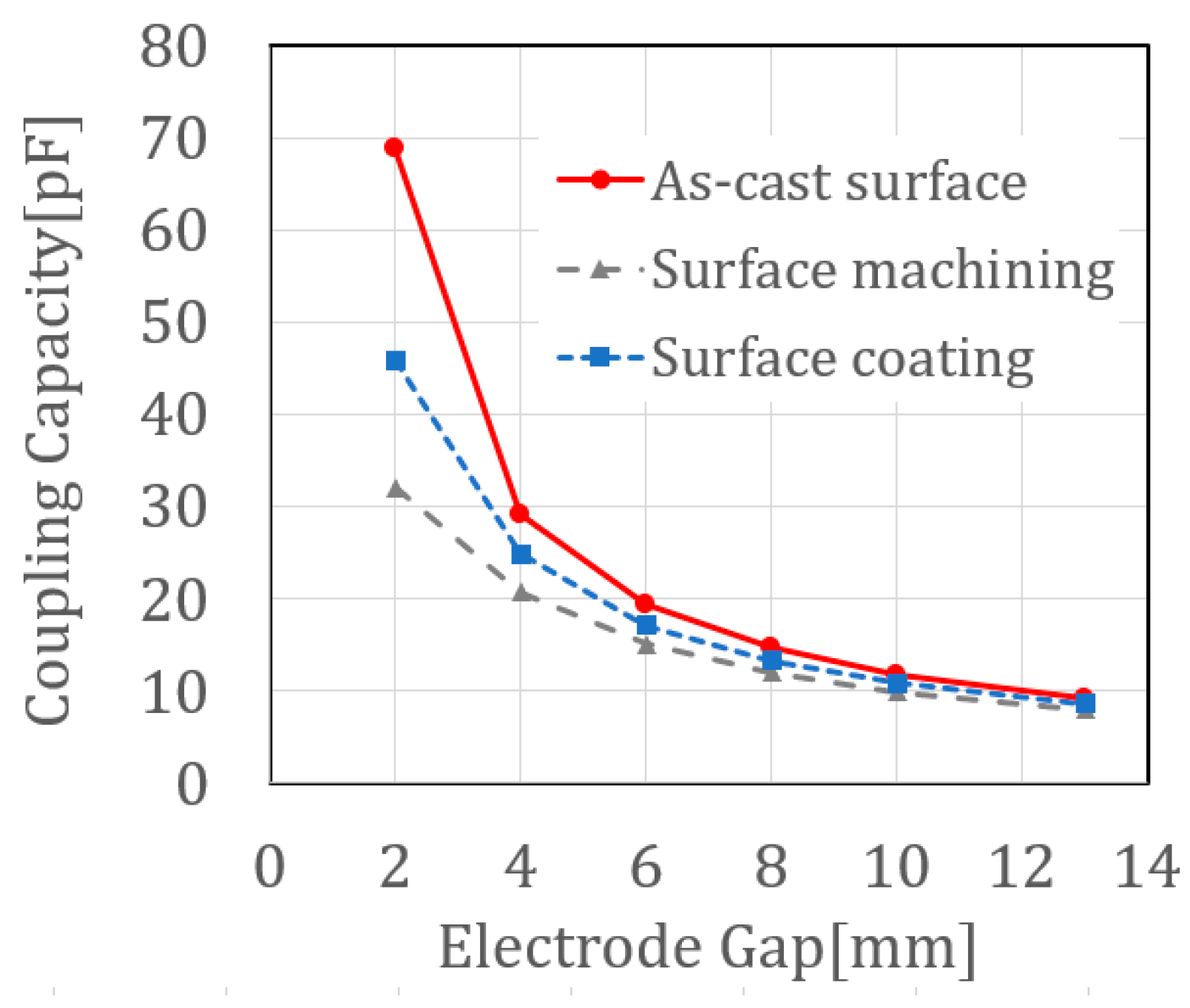

3.1. S-CPT Electrode Material Characteristics #1

3.2. S-CPT Electrode Material Characteristics #2

4. S-CPT Power Transmission Experiment Using Cast Iron Cover Electrodes and Load Resistance Evaluation

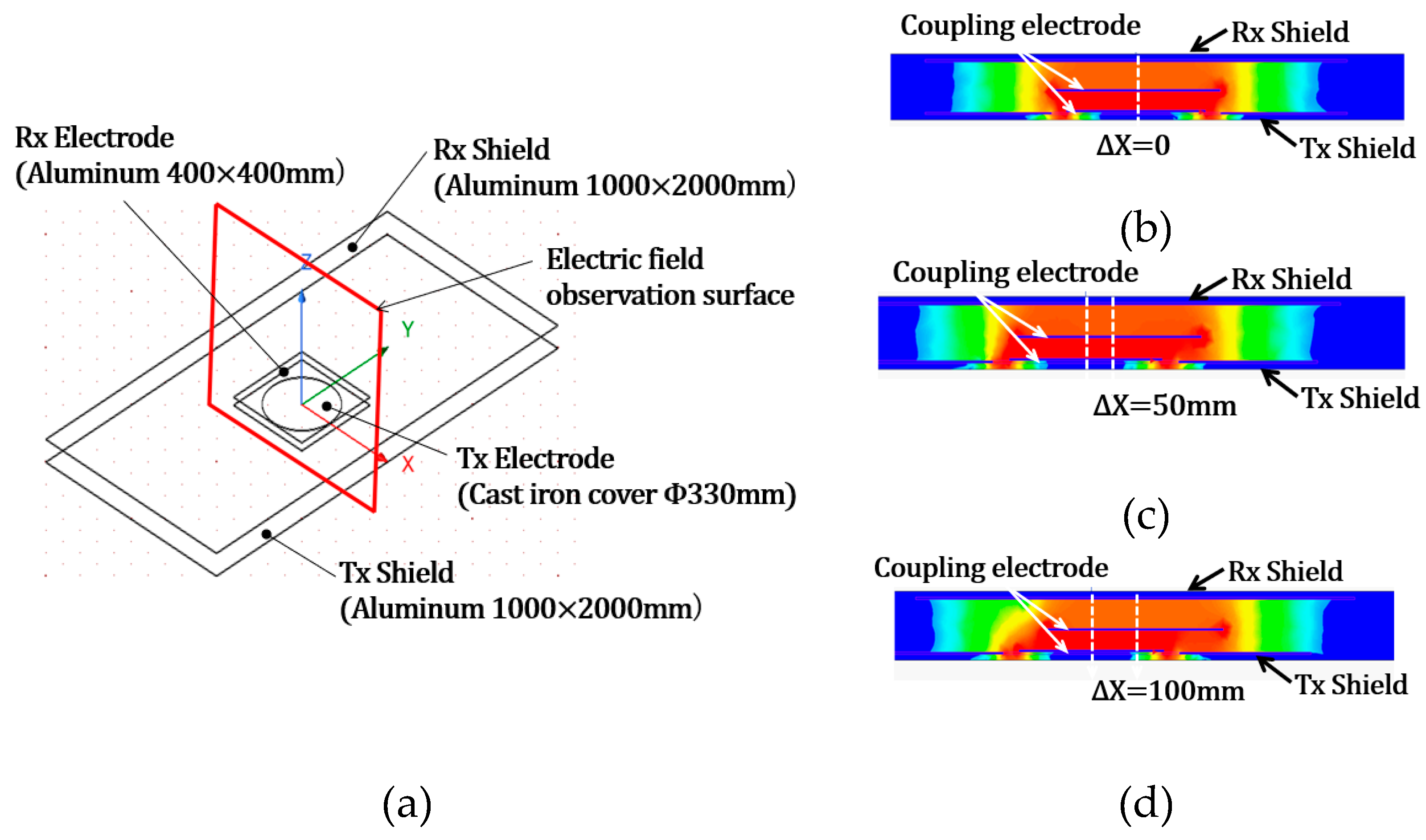

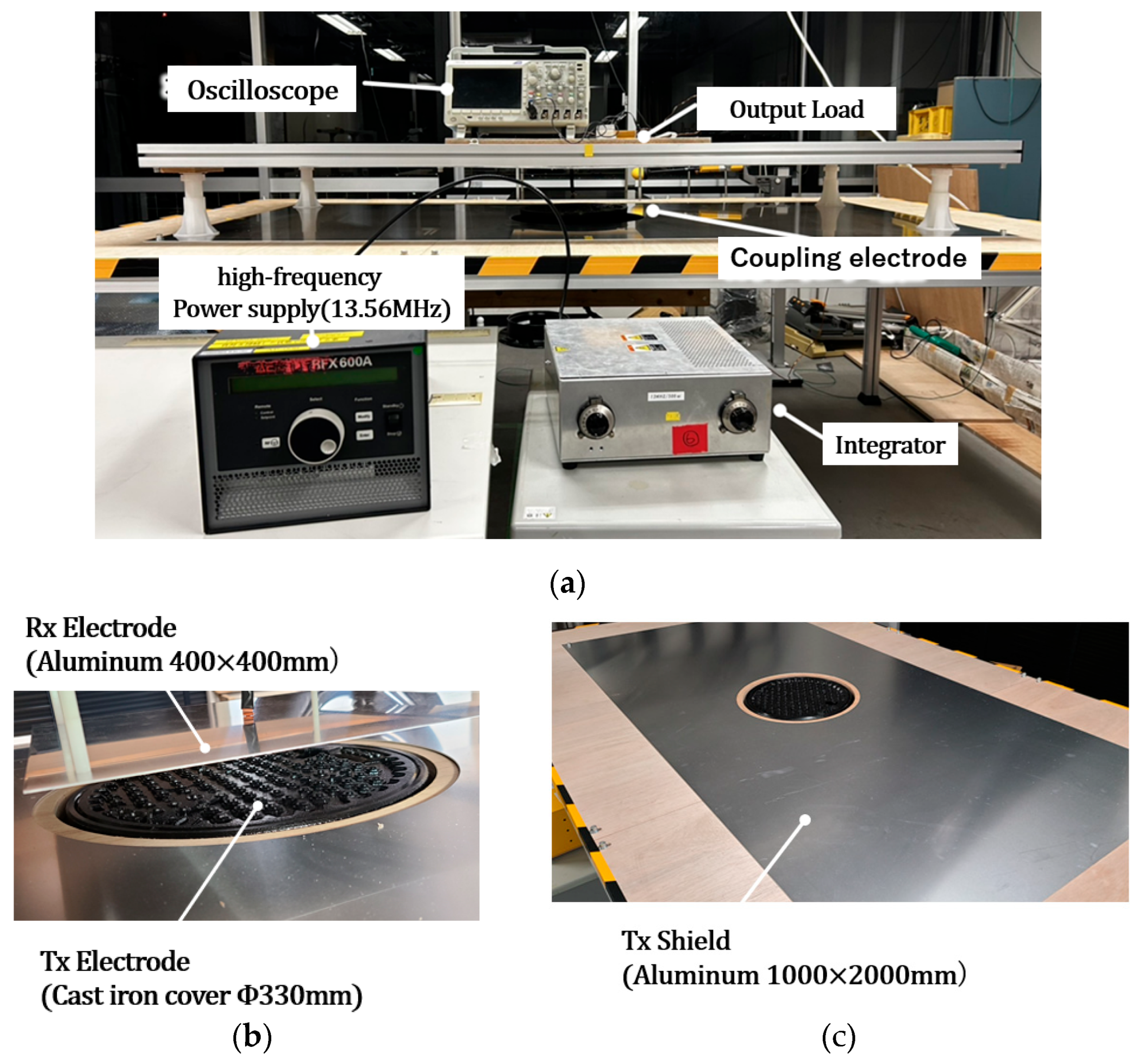

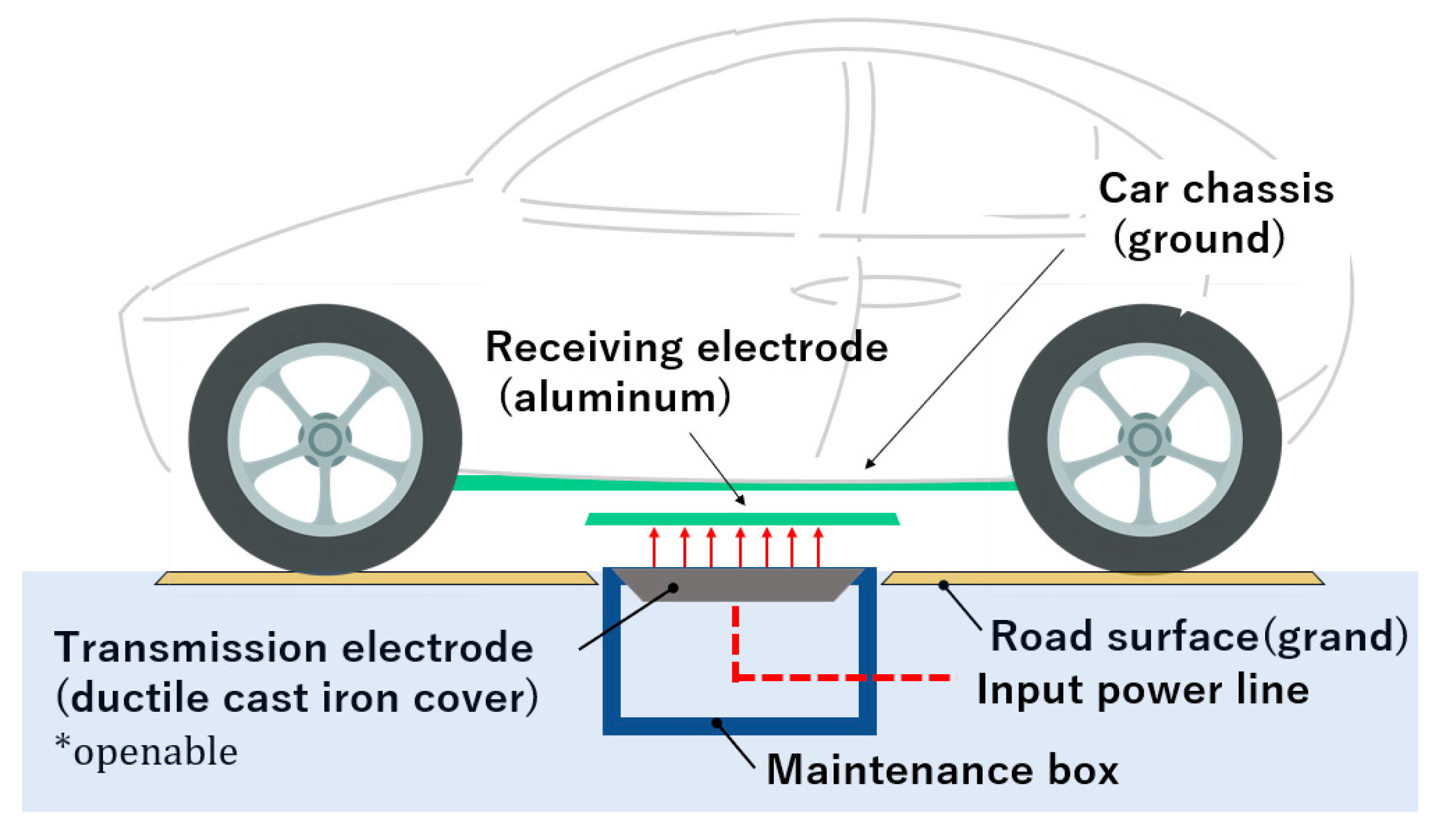

4-1. Power Transmission Experiment Using S-CPT System with Cast Iron Cover as Electrode

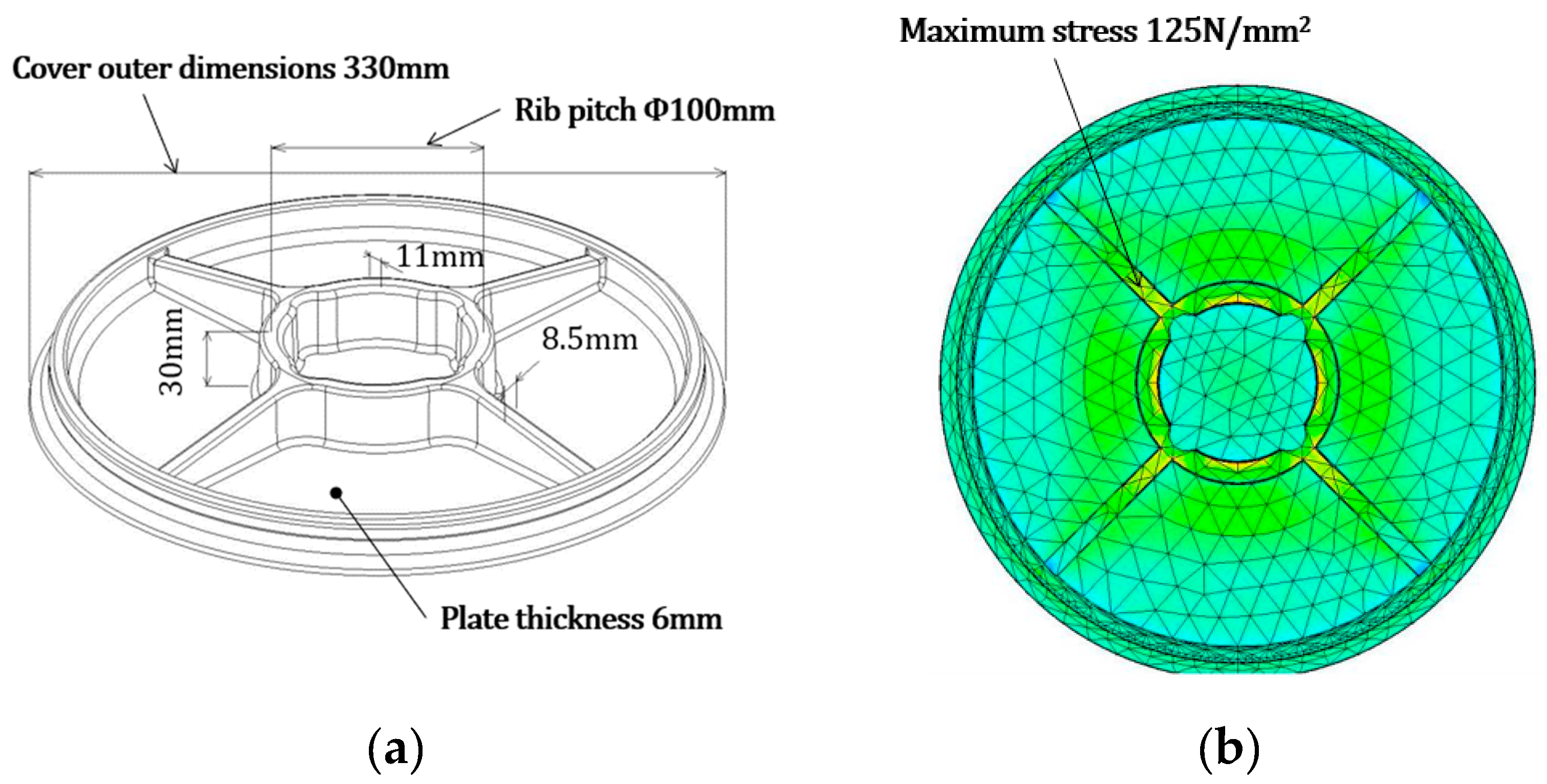

4-2. Cast Iron Cover Electrode for Power Transmission

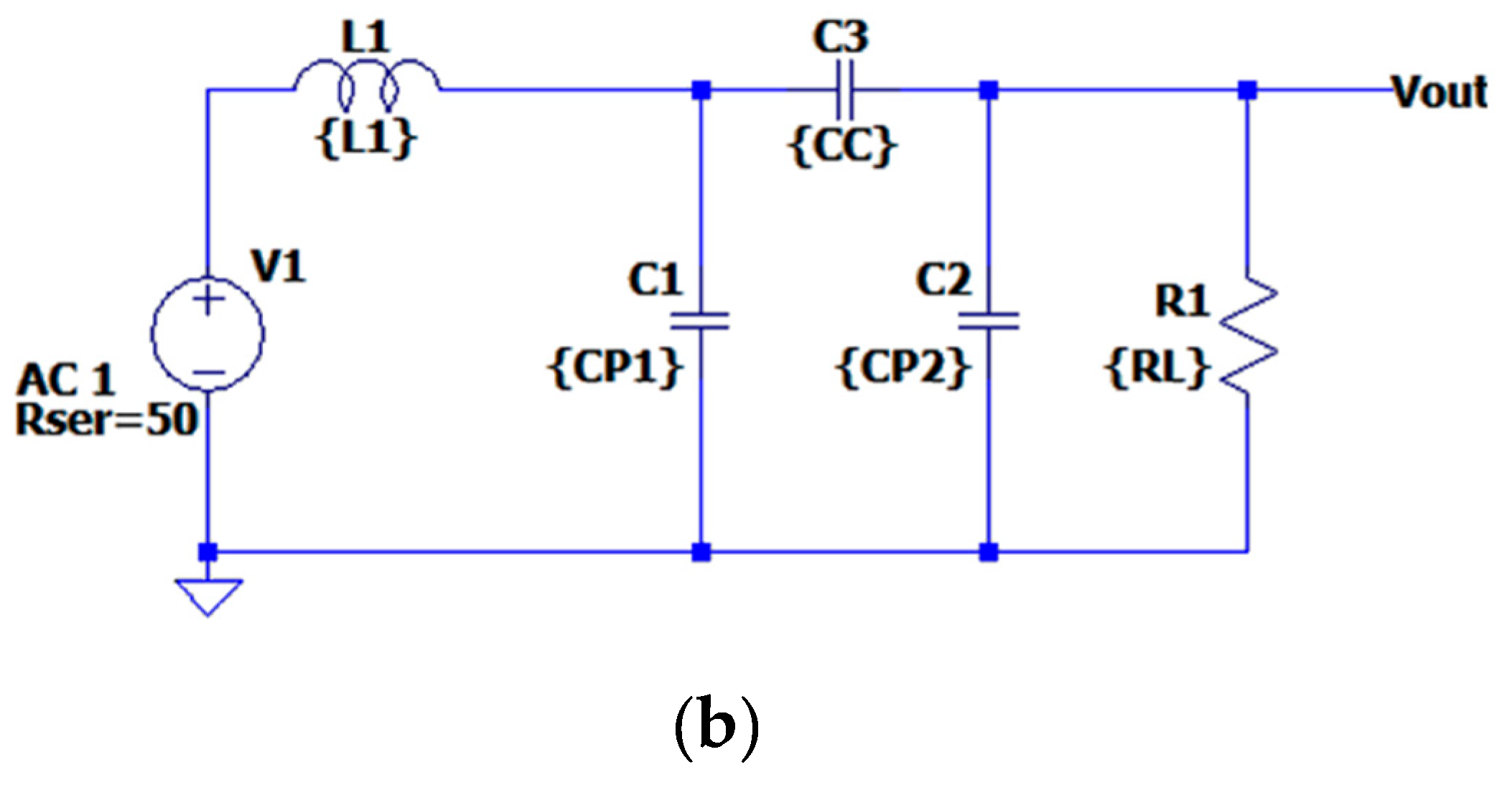

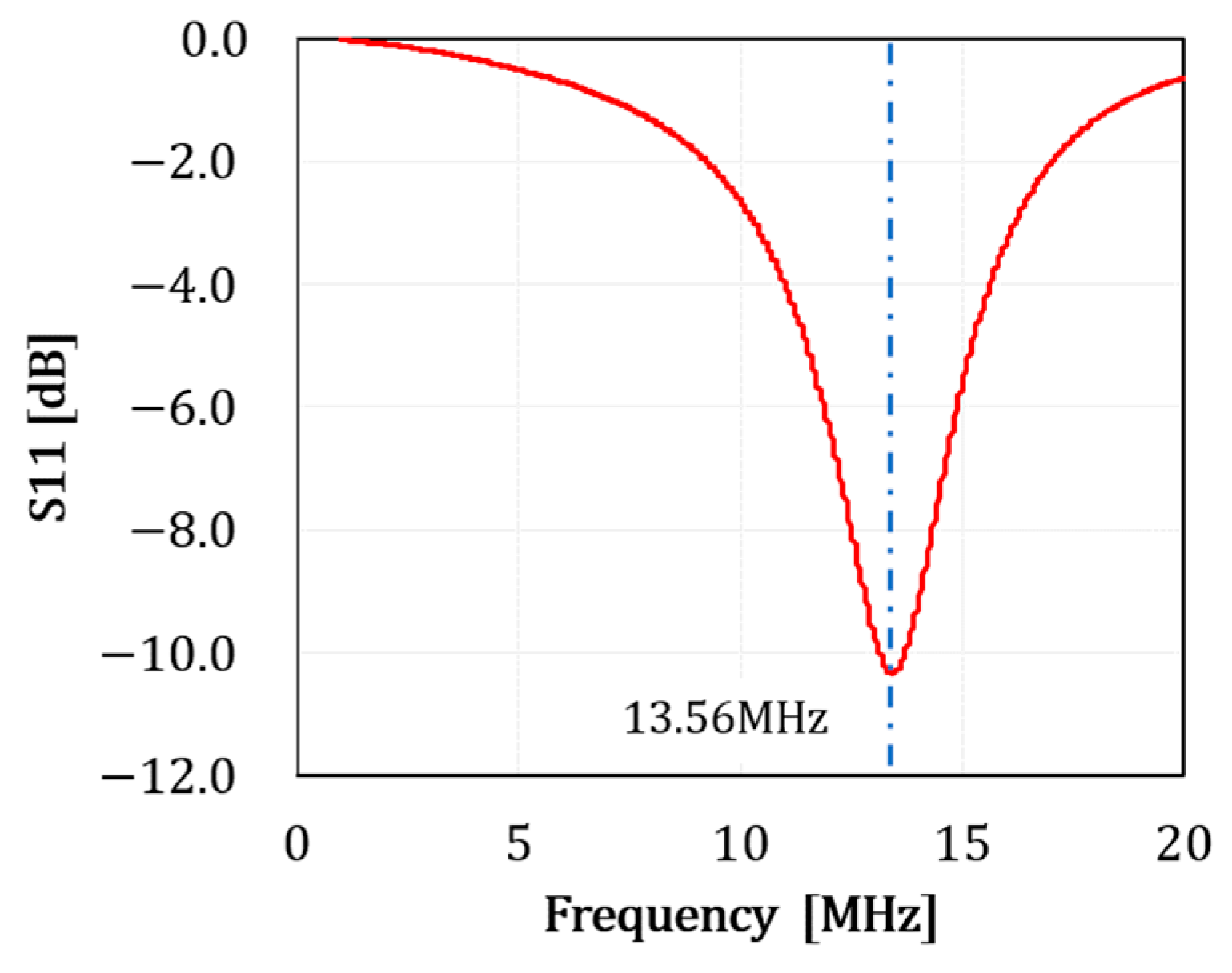

4-3. 4-Plate S-CPT System Configuration and Impedance Matching

4-4. EMI Characteristics

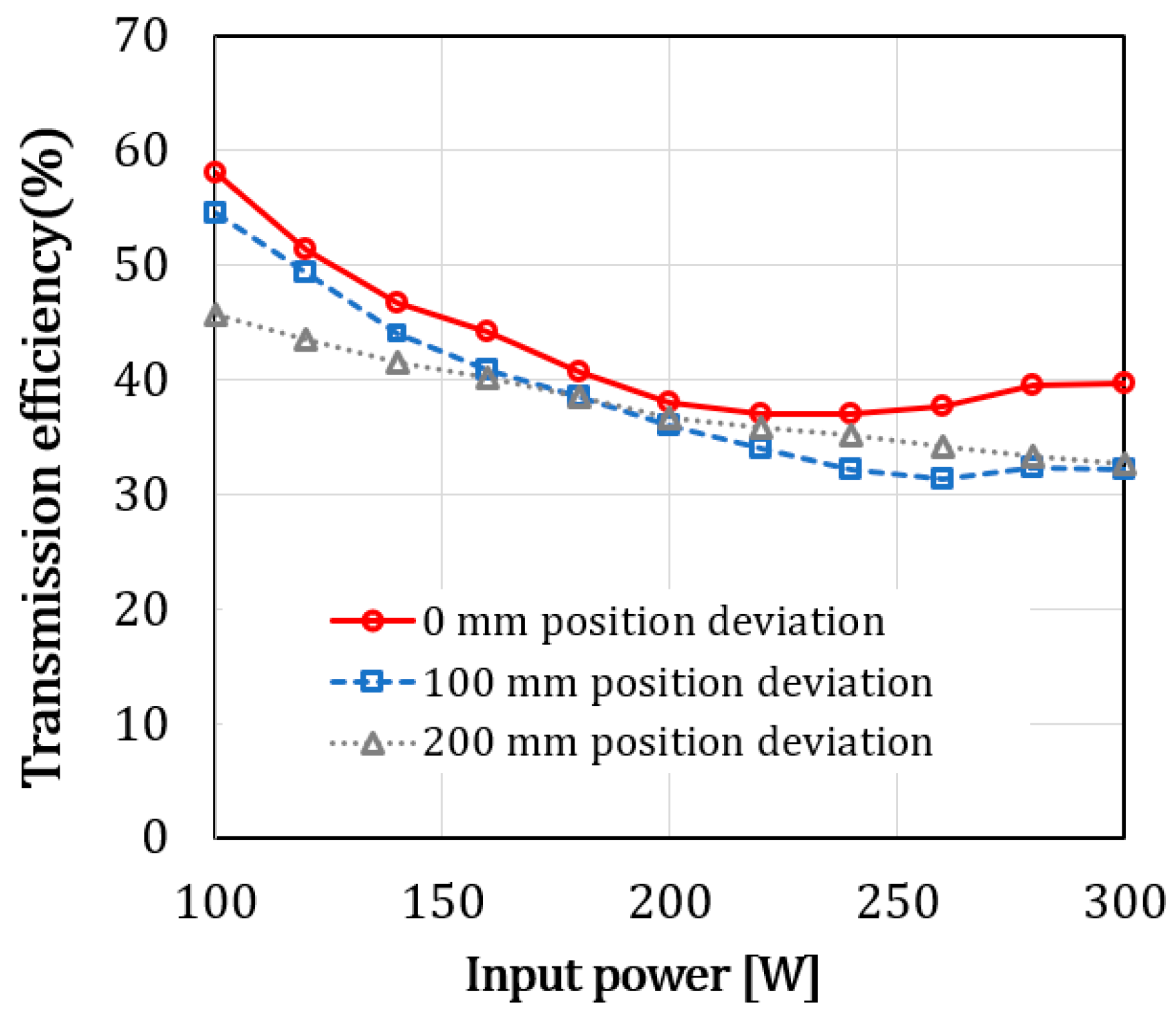

4-5. Power Transmission Test Results

5. Conclusion

References

- Timilsina, R.R.; Zhang, J.; Rahut, D.B.; Patradool, K.; Sonobe, T. Global drive toward net-zero emissions and sustainability via electric vehicles: an integrative critical review. Energy, Ecol. Environ. 2025, 10, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA, Global EV Outlook 2024, International Energy Agency. 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Phase-out of fossil fuel vehicles, Wikipedia. 2024. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phase-out_of_fossil_fuel_vehicles (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Karla Adam, Most new cars in Norway are EVs, The Washington Post, May 30, 2025. online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-solutions/2025/05/30/norway-ev-adoption-electric-cars/?utm_source=chatgpt. (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Schumann, R.A.; Meyer, J.H.; Antwerpen, V.R. A review of green manuring practices in sugarcane production. Proc. S Afr Sugar Technol. Assess. 2000, 74, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, R.R.; Zhang, J.; Rahut, D.B.; Patradool, K.; Sonobe, T. Global drive toward net-zero emissions and sustainability via electric vehicles: an integrative critical review. Energy, Ecol. Environ. 2025, 10, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S&P Global Mobility, Affordability tops charging and range concerns in slowing EV demand, Nov 2023. https://www.spglobal.com/mobility/en/research-analysis/affordability-tops-charging-and-range-concerns-in-slowing-ev-d.html. (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- NREL, Soft Cost Analysis of EV Charging Infrastructure Informs Transition to an Electric Fleet, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2024 https://www.nrel.gov/news/detail/program/2024/soft-cost-analysis-of-ev-charging-infrastructure-informs-transition-to-an-electric-fleet. (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Bi, Z.; Kan, T.; Mi, C.C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Keoleian, G.A. A review of wireless power transfer for electric vehicles: Prospects to enhance sustainable mobility. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, Y.; R, N.; Ali, J.S.M.; Almakhles, D. A Comprehensive Review of the On-Road Wireless Charging System for E-Mobility Applications. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Ma, X.; Hu, R.Q.; Christensen, R. Precise Coil Alignment for Dynamic Wireless Charging of Electric Vehicles with RFID Sensing. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2025, 32, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Ghassemi, L. Soares, H. Wang, and Z. Xi, “A Novel Mathematical Model for Infrastructure Planning of Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer Systems for Electric Vehicles,” Jul. 2021, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2107.11428.

- Wang, C.; Nguyen, H.D. Steady-state Voltage Profile and Long-term Voltage Stability of Electrified Road with Wireless Dynamic Charging. E-Energy '19: The Tenth ACM International Conference on Future Energy Systems. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, USADATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 165–169.

- X. Ma et al., “Exploring Communication Technologies, Standards, and Challenges in Electrified Vehicle Charging,” Mar. 2024, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2403.16830.

- Van Mulders, J.; Delabie, D.; Lecluyse, C.; Buyle, C.; Callebaut, G.; Van der Perre, L.; De Strycker, L. Wireless Power Transfer: Systems, Circuits, Standards, and Use Cases. Sensors 2022, 22, 5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAE International, “SAE International Finalizes Light Duty Wireless Charging ‘Gamechanger’ Standard to Enable Mass Commercialization, Available online:. Available online: https://www.sae.org/news/press-room/2024/08/sae-j2954?utm_source=chatgpt.com. (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- A. Mohamed and S. Shaier, “Evaluation of power transfer efficiency with ferrite sheets in WPT system,” ResearchGate, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317824866. (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- IEA., “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025,” https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/a33abe2e-f799-4787-b09b-2484a6f5a8e4/GlobalCriticalMineralsOutlook2025.pdf. (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Rhee, J.; Woo, S.; Lee, C.; Ahn, S. Selection of Ferrite Depending on Permeability and Weight to Enhance Power Transfer Efficiency in Low-Power Wireless Power Transfer Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Cui, S.; Bie, Z.; Song, K.; Zhu, C.; Matveevich, M.I. Modern Advances in Magnetic Materials of Wireless Power Transfer Systems: A Review and New Perspectives. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U. DigitalCommons, U. All Graduate Theses, and T. Gardner, “Wireless Power Transfer Roadway Integration,” 2017. [Online]. Available: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/6866.

- Honjo, Y.; Caremel, C.; Kawahara, Y.; Sasatani, T. Suppressing Leakage Magnetic Field in Wireless Power Transfer Using Halbach Array-Based Resonators. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2023, 23, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Jia, Q.; Hu, Y.; Yang, C.; Jian, L. Safety Management Technologies for Wireless Electric Vehicle Charging Systems: A Review. Electronics 2025, 14, 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poguntke, T.; Schumann, P.; Ochs, K. Radar-based living object protection for inductive charging of electric vehicles using two-dimensional signal processing. Wirel. Power Transf. 2017, 4, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Espinoza-Andaluz, M.; Thern, M.; Andersson, M. Polymer electrolyte fuel cell system level modelling and simulation of transient behavior. eTransportation 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Luo, B.; Mai, R. Research and Application of Capacitive Power Transfer System: A Review. Electronics 2022, 11, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erel, M.Z.; Bayindir, K.C.; Aydemir, M.T.; Chaudhary, S.K.; Guerrero, J.M. A Comprehensive Review on Wireless Capacitive Power Transfer Technology: Fundamentals and Applications. IEEE Access 2021, 10, 3116–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Luo, B.; Mai, R. Research and Application of Capacitive Power Transfer System: A Review. Electronics 2022, 11, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Xie, S.; Fan, Y. Potential and challenges of capacitive power transfer systems for wireless EV charging: A review of key technologies. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecluyse, C.; Minnaert, B.; Kleemann, M. A Review of the Current State of Technology of Capacitive Wireless Power Transfer. Energies 2021, 14, 5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taisei Corporation, “Roadway Wireless Power Transfer System for Dynamic Charging, National Road Technology Council Report No.2020-6, 2024.” [Online]. Available: https://www.mlit.go.jp/road/tech/jigo/r06/pdf/report2020-6.pdf. (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Lee, I.-O.; Kim, J.; Lee, W. A High-Efficient Low-Cost Converter for Capacitive Wireless Power Transfer Systems. Energies 2017, 10, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikelj, M.; Nagode, M.; Klemenc, J.; Šeruga, D. Influence of Operating Conditions on a Cast-Iron Manhole Cover. Technologies 2022, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintaro Sugi, “Manhole covers as part of the road Their role” Construction Machinery Vol. 70 No. 10, Oct. 2018.

- Mascot Inc., “BS EN 124-2,” [Online]. Available: https://mascotengineering.com/technical-support/en-124-2/?utm_source=chatgpt.com. (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Japanese Standards Association, “Spheroidal graphite cast irons.”, [Online]. Available: https://webdesk.jsa.or.jp/preview/pre_jis_g_05502_000_000_2022_e_ed10_ch.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com. (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Hinode,Ltd. “Characteristics of spheroidal graphite cast iron, [Online]. Available: https://hinodesuido.co.jp/Technology/fcd.html. (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- toshiro Owada, “Electrical resistance of various cast irons,” casting 鋳物, vol. Vol.54 2, pp. 113–118, 1981.

- Muharam, A.; Ahmad, S.; Hattori, R. Scaling-Factor and Design Guidelines for Shielded-Capacitive Power Transfer. Energies 2020, 13, 4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muharam, A.; Ahmad, S.; Hattori, R.; Hapid, A. 13.56 MHz Scalable Shielded-Capacitive Power Transfer for Electric Vehicle Wireless Charging. 2020 IEEE PELS Workshop on Emerging Technologies: Wireless Power Transfer (WoW). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, South KoreaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 298–303.

- Ahmad, S.; Muharam, A.; Hattori, R.; Uezu, A.; Mostafa, T.M. Shielded Capacitive Power Transfer (S-CPT) without Secondary Side Inductors. Energies 2021, 14, 4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yao, S.; Pan, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, C. A Review of Capacitive Power Transfer Technology for Electric Vehicle Applications. Electronics 2023, 12, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. R. Lide, CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 90th ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press, 2009, pp. 12-114.

- J. R. Davis, Metals Handbook Desk Edition. Materials Park, OH, USA: ASM International, 1998, pp. 1-85.

- H. Asanuma, Y. Kondo, and K. Tashiro, “Electrical Resistivity of Ductile Cast Iron and Its Dependence on Graphite Morphology,” Mater. Trans., vol. 48, no. 9, pp. 2463–2468, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, K.; Noh, T.; Kang, I.; Kim, S. High permeability and low core loss of amorphous Fe-Zr-B-M (M=Ni, Nb) alloys in high frequency range. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1993, 29, 3463–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Jiles, Introduction to Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press, 2015, pp. 87–88.

- R. M. Bozorth, Ferromagnetism. New York, NY, USA: IEEE Press, 1993, pp. 27–31.

- Erel, M.Z.; Bayindir, K.C.; Aydemir, M.T.; Chaudhary, S.K.; Guerrero, J.M. A Comprehensive Review on Wireless Capacitive Power Transfer Technology: Fundamentals and Applications. IEEE Access 2021, 10, 3116–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia. “ISO/IEC 14443”, [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISO/IEC_14443?utm_source=chatgpt.com. (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Shimizu Co., Ltd. ” Electroplation”, Available: https://shimizu-corp.co. (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Tobinaga, H.; Yamaguchi, E.; Murayama, M. Consideration of plastic deformation capacity of spheroidal graphite cast iron to deck slab for highway bridge. J. Struct. Eng. 2018, 64A, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Ground Manhole Industry Association.” Specifications and performance of ground manholes for sewerage systems.

- Updated] Sewerage Association Standard JSWAS G-4. [Online]. Available: https://jgma.gr.jp/manhole-cover/g4second/. (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Tateishi, E.; Yi, Y.; Kai, N.; Kumagae, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kanaya, H. Development of Cast Iron Manhole Cover With Broadband-Radio-Transmission Characteristics Applying Spiral Structure. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2024, 24, 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| material name | Conductivity (σ) S/m |

Relative permeability (μr) | Specific resistance (ρ) (Ω·m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | 5.8 ×10⁻⁷ | 1.0 (nonmagnetic) | 1.7 × 10⁻⁸ |

| Aluminum | 3.5 ×10⁻⁷ | 1.0 (nonmagnetic) | 2.8 ×10⁻⁸ |

| Ductile Cast Iron | 0.9 to 1.3 ×10⁻⁶ | 80 to 200 | 7.7 to 11 ×10⁻⁷ |

| Structural Steel | 5.8 to 6.5 ×10⁻⁶ | 100 to 800 | 1.5 to 1.7 ×10⁻⁷ |

| Carbon Steel | 5.5 to 7.0 ×10⁻⁶ | 100 to 800 | 1.4 to 1.7 × 10⁻⁷ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).