1. Introduction

Healthcare workers worldwide face significant challenges that affect their psychological well-being and job performance. The healthcare industry is characterized by high work demands, emotional labor, time pressure, and high-stakes decision-making [

1,

2]. The COVID-19 pandemic further intensified these challenges, exposing healthcare workers to unprecedented levels of stress, burnout, and mental health concerns [

3,

4]. In this context, understanding the factors that protect against job burnout and promote mental health resilience among healthcare workers has become increasingly important for maintaining the quality and sustainability of healthcare systems.

Job burnout among healthcare workers has been associated with numerous negative outcomes, including decreased quality of patient care, increased medical errors, higher staff turnover rates, and diminished overall healthcare system effectiveness [

5,

6]. While many studies have focused on identifying risk factors for burnout, there is growing interest in protective factors and psychological resources that may buffer against these occupational challenges. Psychological resilience, defined as the ability to adapt positively and maintain functioning in the face of significant adversity [

7,

8], has emerged as a crucial protective factor in this regard.

The transactional theory of stress and coping [

9] provides a foundational framework for understanding how psychological resilience may influence job burnout through its effects on stress perception and management. According to this model, individuals with higher psychological resilience may appraise challenging situations as less threatening and perceive themselves as having greater coping resources, thereby experiencing lower levels of stress in response to occupational demands. The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory [

10] further elucidates this process, suggesting that psychological resilience acts as a personal resource that helps individuals conserve other resources and prevent the resource depletion that characterizes burnout.

While the direct relationship between psychological resilience and job burnout has been established in previous research [

11,

12], the mechanisms underlying this relationship are not fully understood. Occupational stress has been proposed as a potential mediator, as resilience may influence how individuals perceive and respond to workplace stressors, which in turn affects burnout development [

13,

14]. Additionally, contextual factors such as organizational climate and trust may moderate these relationships by influencing how effectively individuals can deploy their resilience resources in the workplace [

15].

Organizational trust, defined as employees’ positive expectations regarding the intentions and behaviors of the organization and its representatives [

16], may be particularly relevant in healthcare settings where team collaboration and interdependence are essential. The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model [

17,

18] suggests that job resources (including organizational factors like trust) can buffer the negative effects of job demands on occupational outcomes. In this framework, organizational trust may enhance the effectiveness of personal resources like resilience by creating a psychologically safe environment in which healthcare workers feel supported in managing workplace challenges.

This study aims to investigate the complex relationships between psychological resilience, occupational stress, organizational trust, and job burnout among healthcare workers. Specifically, we propose a moderated mediation model in which psychological resilience influences job burnout both directly and indirectly through occupational stress, with organizational trust moderating these relationships. By examining these interrelationships, this study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the protective mechanisms against burnout in healthcare settings and informs the development of targeted interventions at both individual and organizational levels.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Psychological Resilience and Job Burnout

Psychological resilience refers to the ability to adapt positively and maintain psychological functioning despite experiencing significant adversity or trauma [

19,

20]. In occupational contexts, resilience enables individuals to cope effectively with workplace stressors, adapt to changing conditions, and recover from challenging experiences [

21,

22]. Healthcare workers, who routinely face high-stress situations, ethical dilemmas, and emotional demands, particularly benefit from psychological resilience as a protective resource [

23].

Job burnout is conceptualized as a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors in the workplace, characterized by three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (or cynicism), and reduced personal accomplishment [

24,

25]. In healthcare settings, burnout has been linked to reduced quality of patient care, increased medical errors, higher rates of healthcare-associated infections, and decreased patient satisfaction [

26,

27]. Additionally, burnout contributes to healthcare worker turnover, absenteeism, and early retirement, exacerbating workforce shortages and increasing healthcare costs [

28].

The relationship between psychological resilience and job burnout has been well-documented in healthcare contexts. Studies across various healthcare professionals, including nurses [

11,

29], physicians [

30], and mental health providers [

31], have consistently found negative associations between resilience and burnout. For instance, Mealer et al. [

32] found that highly resilient intensive care unit nurses reported significantly lower burnout symptoms compared to their less resilient colleagues. Similarly, Arrogante [

12] demonstrated that resilience was inversely related to all three dimensions of burnout among healthcare professionals.

Based on both theoretical foundations and empirical evidence, we propose our first hypothesis:

H1: Psychological resilience is negatively associated with job burnout among healthcare workers.

2.2. The Mediating Role of Occupational Stress

Occupational stress refers to the harmful physical and emotional responses that occur when job requirements do not match the capabilities, resources, or needs of the worker [

33]. Healthcare workers face numerous occupational stressors, including heavy workloads, time pressure, role conflicts, emotional demands, exposure to suffering and death, and concerns about medical errors [

34,

35].

The relationship between occupational stress and burnout is well-established in the literature. According to the job demands-resources model [

17,

36], prolonged exposure to job demands (stressors) without adequate resources leads to exhaustion and disengagement—the core components of burnout. Multiple studies in healthcare settings have confirmed that higher levels of occupational stress predict greater burnout [

13,

37].

Psychological resilience may influence job burnout not only directly but also indirectly through its impact on occupational stress. The transactional model of stress and coping [

9] provides a theoretical framework for understanding this relationship. According to this model, resilience influences both primary appraisal (evaluation of potential threat) and secondary appraisal (assessment of coping resources), thereby affecting the stress response.

Based on these theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2: Psychological resilience is negatively associated with occupational stress among healthcare workers.

H3: Occupational stress is positively associated with job burnout among healthcare workers.

H4: Occupational stress mediates the relationship between psychological resilience and job burnout among healthcare workers.

2.3. The Moderating Role of Organizational Trust

Organizational trust is defined as "a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another" within an organizational context [

16]. In healthcare settings, organizational trust encompasses employees’ confidence in their organization’s competence, openness, concern for employees, reliability, and identification with organizational values [

38].

The job demands-resources model [

17,

36] provides a theoretical framework for understanding how organizational trust might moderate the relationship between psychological resilience, occupational stress, and burnout. According to this model, job resources (including organizational factors like trust) can buffer the negative impact of job demands on stress and burnout.

Based on this research and the theoretical frameworks described above, we propose that organizational trust will moderate the relationship between psychological resilience and occupational stress, as well as the indirect effect of resilience on burnout through occupational stress.

Specifically, we hypothesize:

H5: Organizational trust moderates the relationship between psychological resilience and occupational stress, such that the negative relationship is stronger when organizational trust is high.

H6: Organizational trust moderates the indirect effect of psychological resilience on job burnout through occupational stress, such that the indirect effect is stronger when organizational trust is high.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design, recruiting healthcare personnel from multiple tertiary hospitals through convenience and snowball sampling methods. The research team first contacted hospital management to obtain research permission and assisted in questionnaire distribution. The survey was conducted from September to December 2023, using a combination of online and paper questionnaires. Participants signed informed consent forms after being informed of the research purpose and completed self-assessment questionnaires. To ensure data quality, attention check items were included, and questionnaires completed too quickly were eliminated.

A total of 350 questionnaires were distributed, with 303 valid questionnaires returned, yielding an effective response rate of 86.57%. Participants’ demographic characteristics are shown in

Table 1. The sample comprised 70.30% females (213 individuals) and 29.70% males (90 individuals). Age distribution was primarily concentrated between 26-40 years, accounting for 62.70% of the total sample. Educational background was predominantly bachelor’s degree (60.40%), followed by master’s degree (23.76%). More than half (51.49%) of the participants had over 10 years of work experience. In terms of occupational distribution, nursing staff accounted for 33.66%, technical personnel 29.70%, and physicians 24.75%.

3.2. Measures

All measurement tools used Chinese versions, with some scales undergoing translation-back-translation processes to ensure their applicability in the Chinese cultural context. All scales employed a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher levels of the corresponding trait or state.

Psychological Resilience: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) simplified version [

19] was used, containing 25 items measuring individuals’ adaptability when facing pressure and adversity. The scale covers five dimensions: personal competence, tolerance of negative emotions, acceptance of change, sense of control, and spiritual influence. Sample items include "I am able to adapt to change" and "I can stay focused and think clearly under pressure." In this study, the scale’s Cronbach’s

coefficient was 0.945, indicating excellent internal consistency.

Job Burnout: The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) revised version [

24] was used, containing 22 items measuring three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. Sample items include "I feel emotionally drained from my work" (emotional exhaustion), "I feel I have become more callous toward some patients" (depersonalization), and "I feel I have accomplished many worthwhile things in my job" (personal accomplishment, reverse-scored). In this study, the scale’s Cronbach’s

coefficient was 0.921.

Occupational Stress: The Healthcare Personnel Occupational Stress Scale [

34] revised version was used, containing 20 items assessing dimensions such as workload, interpersonal conflict, professional development pressure, and work environment pressure. Sample items include "My workload is too heavy" and "I often find it difficult to balance work and personal life." In this study, the scale’s Cronbach’s

coefficient was 0.920.

Organizational Trust: The Organizational Trust Scale [

38,

39] revised version was used, containing 15 items measuring trust in organizational competence, benevolence, and integrity. Sample items include "I trust that hospital management can make reasonable decisions" and "I believe the hospital will fulfill its commitments to employees." In this study, the scale’s Cronbach’s

coefficient was 0.947.

Control Variables: Based on previous research, demographic variables that might influence the relationships between main variables were collected, including gender, age, education level, years of work experience, and occupational type.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 26.0 and Mplus 8.0 software. First, preliminary data screening was performed to address missing values and outliers, and to test normality assumptions. Second, descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were conducted to understand the basic characteristics of each variable and their interrelationships.

For the measurement model, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess the structural validity and measurement quality of each scale. Cronbach’s coefficients were calculated to assess internal consistency for all measurement tools, and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and explained total variance were used to evaluate scale validity.

To test the research hypotheses, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to analyze direct and indirect relationships between variables. A two-stage procedure was employed: first confirming the fit of the measurement model, then evaluating the structural model. Model fit was assessed through multiple indicators, including the chi-square ratio (/df), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

Mediation effects were tested using the Bootstrap method (5000 resamples), determining the significance of indirect effects by examining whether the 95% confidence interval included zero. Moderation effects were tested through interaction terms, with simple slope analysis further exploring conditional effects at different levels of the moderating variable. Moderated mediation effects were tested through conditional indirect effects, examining the indirect effect of psychological resilience on job burnout through occupational stress at different levels of organizational trust.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients for the main research variables. Psychological resilience was significantly negatively correlated with job burnout (r = -0.48, p < 0.001) and with occupational stress (r = -0.53, p < 0.001). Occupational stress was significantly positively correlated with job burnout (r = 0.61, p < 0.001). Organizational trust was significantly negatively correlated with occupational stress (r = -0.44, p < 0.001) and job burnout (r = -0.39, p < 0.001), and significantly positively correlated with psychological resilience (r = 0.30, p < 0.001). These correlation results preliminarily support the expected relationships between variables in the research hypotheses.

4.2. Measurement Model

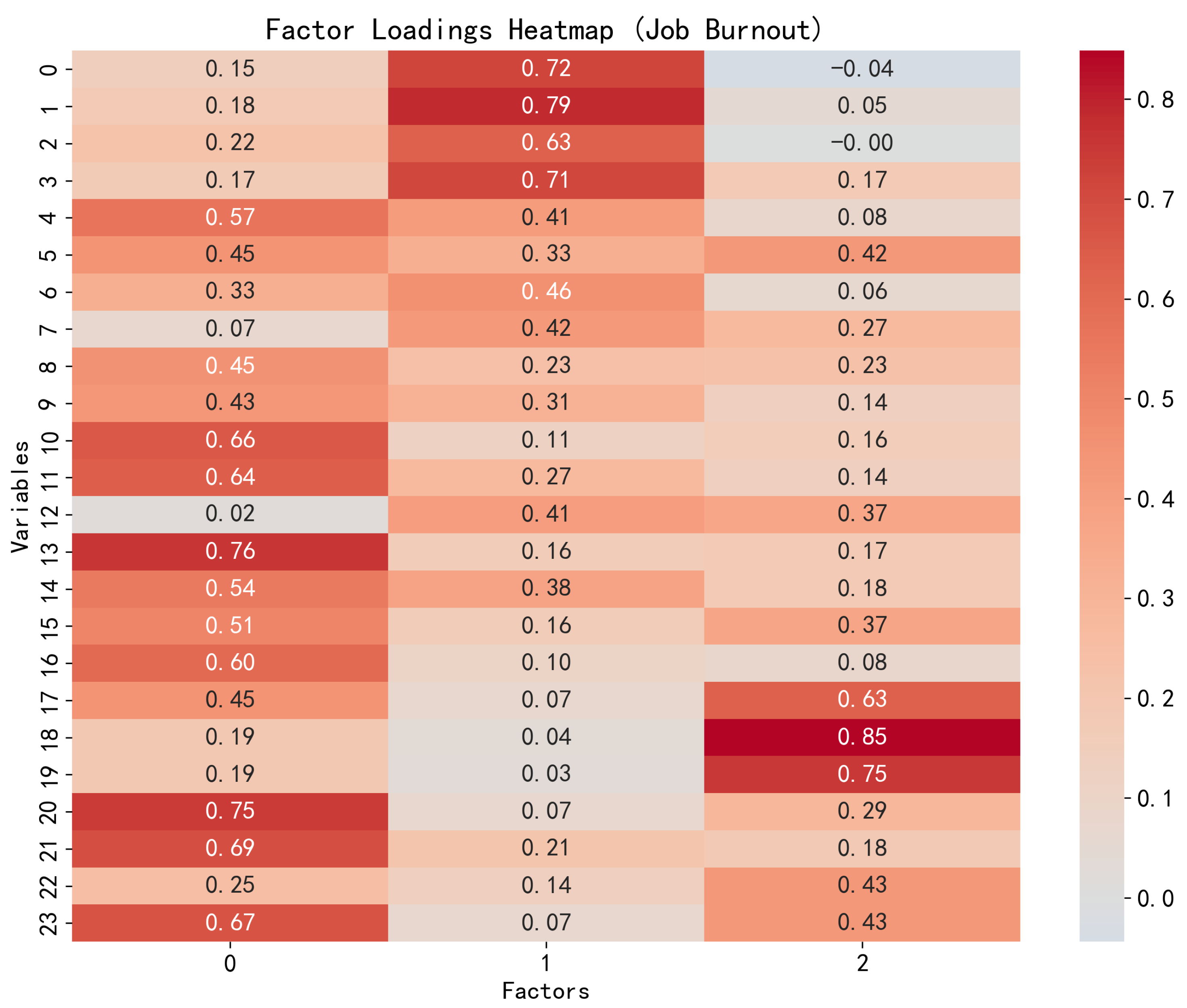

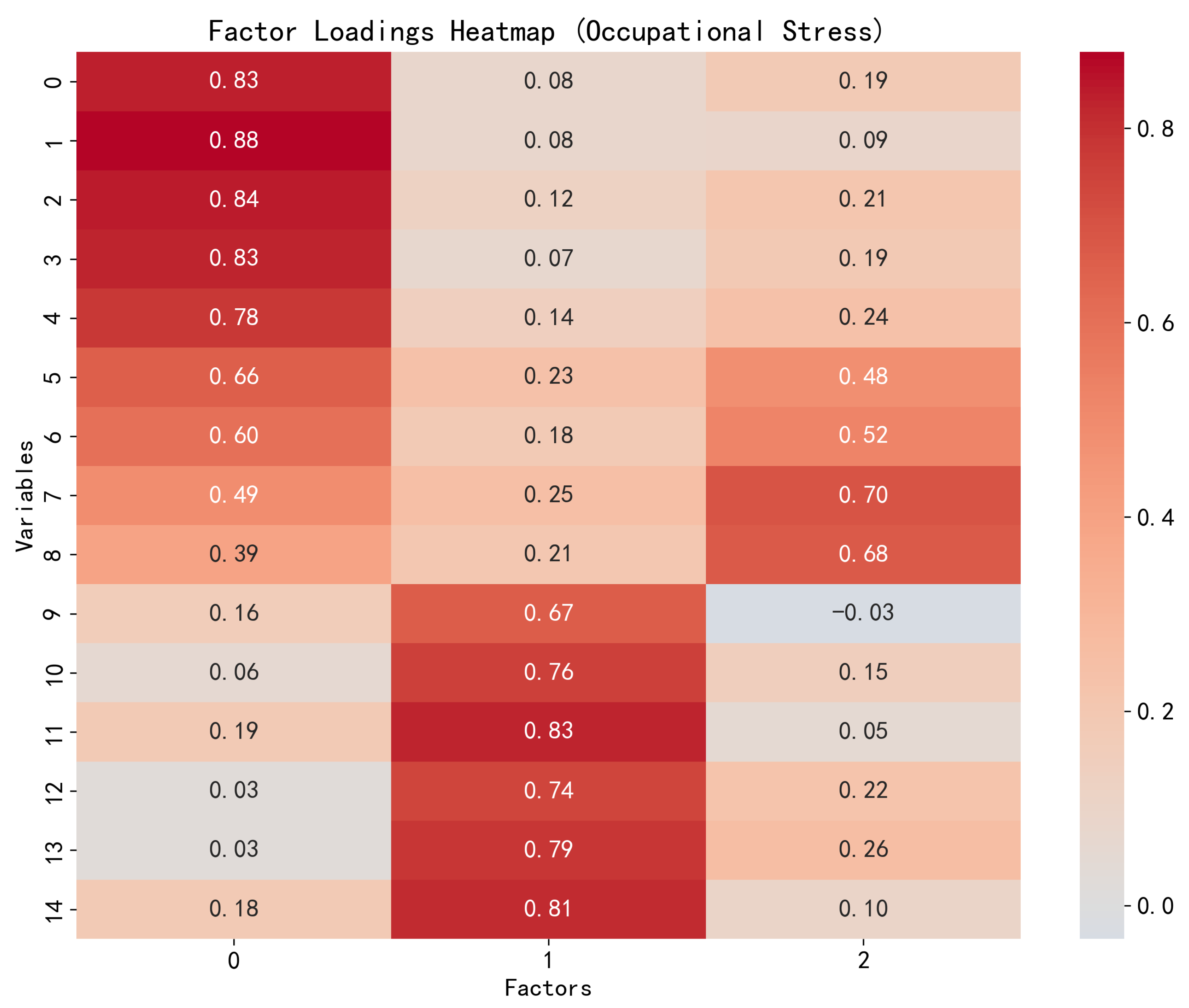

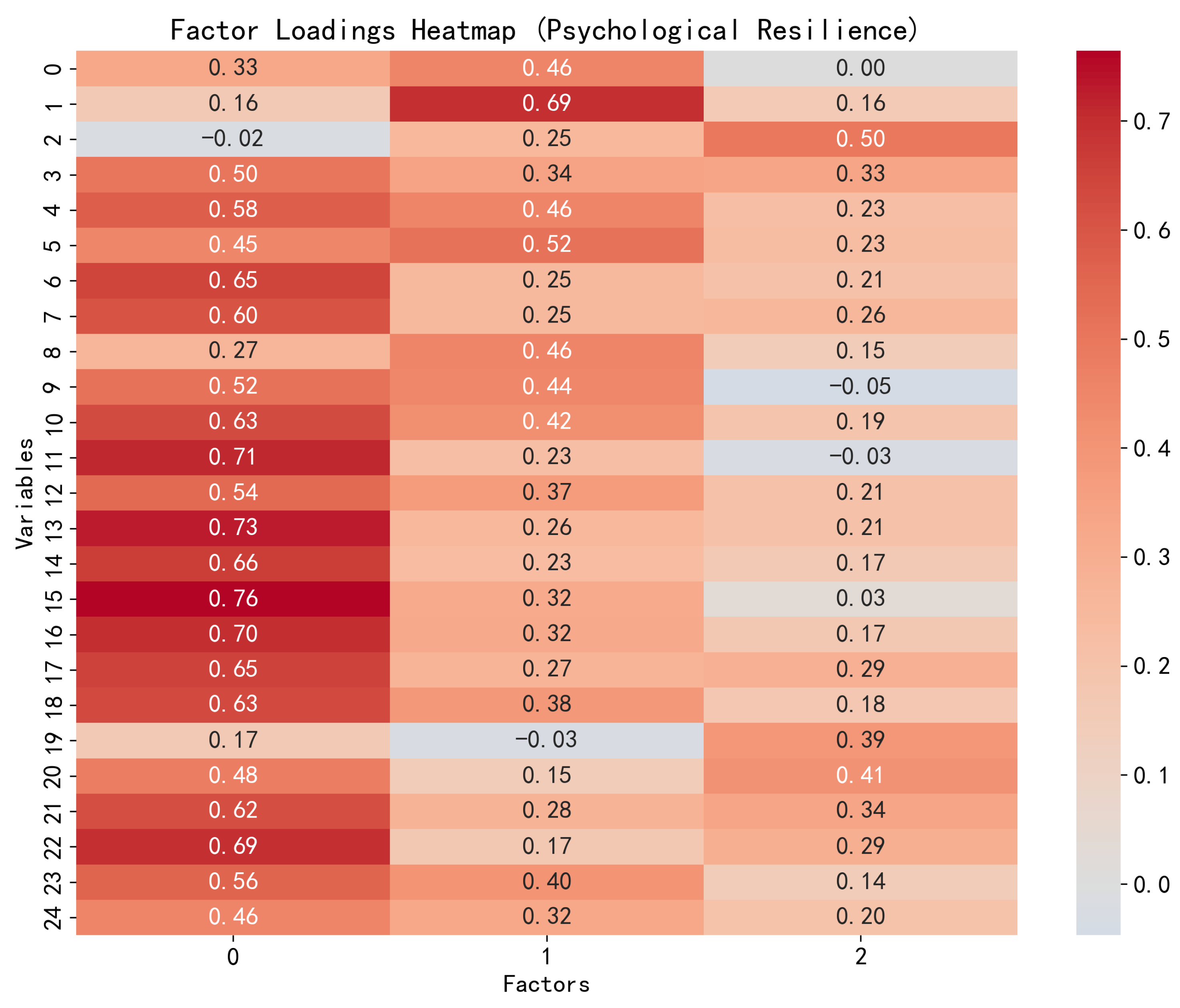

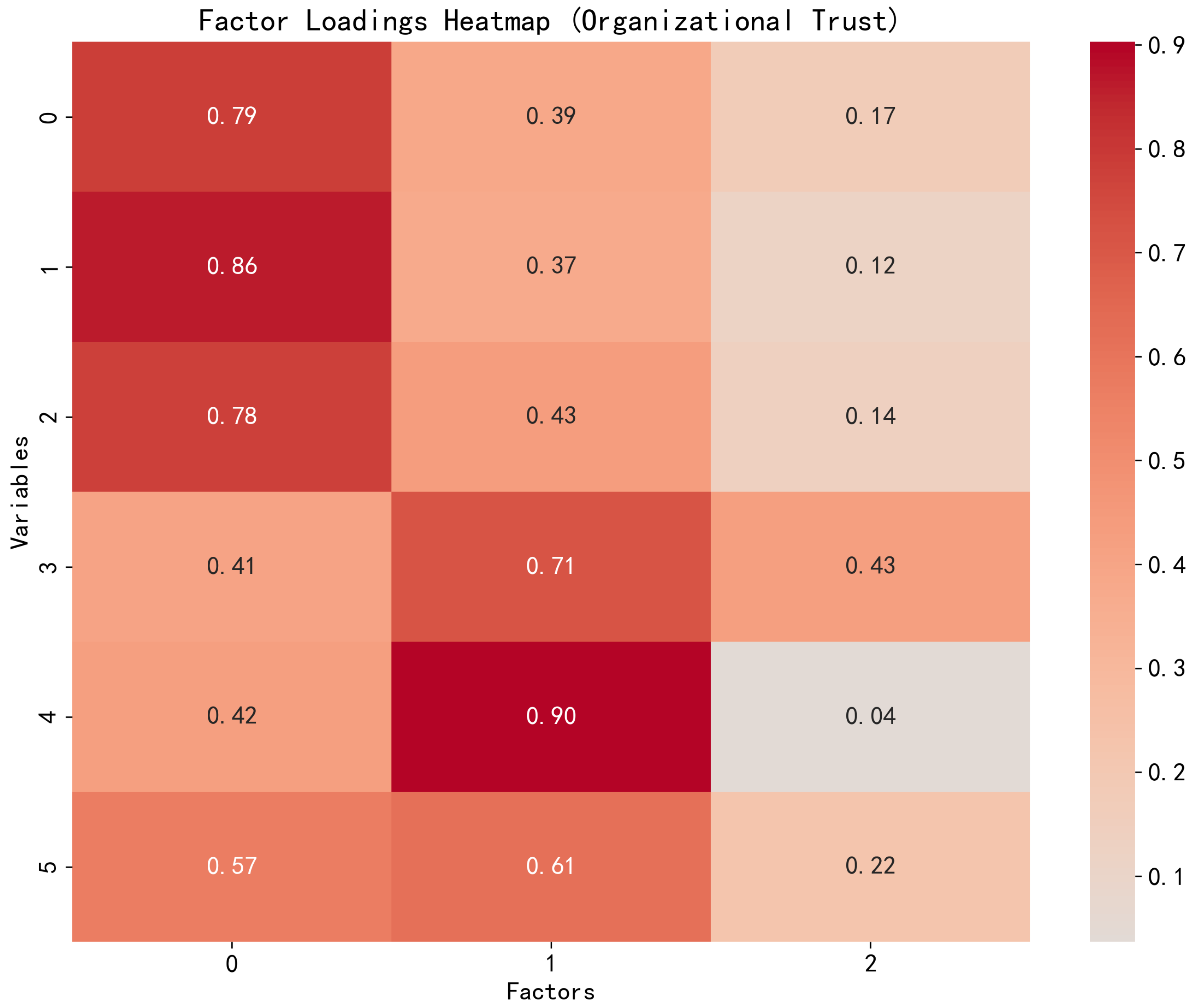

Before hypothesis testing, the reliability and validity of the measurement model were assessed. As shown in

Table 3, all scales had Cronbach’s

coefficients exceeding 0.90, indicating excellent internal consistency of the measurement tools. KMO values all exceeded 0.89, indicating the data were suitable for factor analysis. The percentage of explained total variance ranged from 63.1% to 97.8%, indicating that each scale could explain most of the variance in the measured constructs.

Confirmatory factor analysis results showed that the measurement model of the four main variables had good fit: /df = 2.843, CFI = 0.906, RMSEA = 0.078. All items’ standardized factor loadings were greater than 0.60 and significant at the p < 0.001 level, further supporting the convergent validity of the measurement model.

4.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

The fit indices of the structural equation model showed that the hypothesized model fit the data well:

/df = 2.843, CFI = 0.906, RMSEA = 0.078.

Figure 1 shows the structural model and path coefficients.

The path analysis results of the structural equation model supported Hypothesis 1, showing a significant negative correlation between psychological resilience and job burnout ( = -0.283, p < 0.001). Hypothesis 2 was also supported, with psychological resilience significantly negatively correlated with occupational stress ( = -0.570, p < 0.001). Hypothesis 3 was similarly supported, with occupational stress significantly positively correlated with job burnout ( = 0.380, p < 0.001).

The path analysis results of the structural equation model supported Hypothesis 1, showing a significant negative correlation between psychological resilience and job burnout ( = -0.283, p < 0.001). Hypothesis 2 was also supported, with psychological resilience significantly negatively correlated with occupational stress ( = -0.570, p < 0.001). Hypothesis 3 was similarly supported, with occupational stress significantly positively correlated with job burnout ( = 0.380, p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Factor Loadings Heatmap for Job Burnout.

Figure 1.

Factor Loadings Heatmap for Job Burnout.

Figure 2.

Factor Loadings Heatmap for Occupational Stress.

Figure 2.

Factor Loadings Heatmap for Occupational Stress.

Figure 3.

Factor Loadings Heatmap for Psychological Resilience.

Figure 3.

Factor Loadings Heatmap for Psychological Resilience.

4.4. Mediating Role of Occupational Stress

To test Hypothesis 4, regarding the mediating role of occupational stress in the relationship between psychological resilience and job burnout, Bootstrap analysis (5000 resamples) was conducted. As shown in

Table 4, the indirect effect of psychological resilience on job burnout through occupational stress was significant (indirect effect = -0.217, 95% CI = [-0.389, -0.085]). Simultaneously, the direct effect of psychological resilience on job burnout remained significant (

= -0.283, p < 0.001), indicating that occupational stress played a partial mediating role in the relationship between psychological resilience and job burnout, thus supporting Hypothesis 4.

4.5. Moderating Role of Organizational Trust

Hypothesis 5 predicted that organizational trust would moderate the relationship between psychological resilience and occupational stress. Analysis results showed that the interaction term of psychological resilience and organizational trust had a significant effect on occupational stress (

= -0.186, p < 0.01). To further explain this moderating effect, simple slope analysis was conducted under conditions of high organizational trust (+1 SD) and low organizational trust (-1 SD). As shown in

Figure 4, under conditions of high organizational trust, the negative relationship between psychological resilience and occupational stress was stronger (

= -0.756, p < 0.001), while under conditions of low organizational trust, this relationship was weaker (

= -0.384, p < 0.001). These results supported Hypothesis 5, indicating that organizational trust enhanced the buffering effect of psychological resilience on occupational stress.

To test Hypothesis 6, regarding the moderating role of organizational trust on the indirect effect of psychological resilience on job burnout through occupational stress, conditional indirect effects were calculated at different levels of organizational trust. Under high organizational trust conditions (+1 SD), the indirect effect of psychological resilience on job burnout through occupational stress was stronger (indirect effect = -0.288, 95% CI = [-0.486, -0.113]); while under low organizational trust conditions (-1 SD), this indirect effect was weaker (indirect effect = -0.146, 95% CI = [-0.295, -0.037]). The moderated mediation index was significant (index = -0.071, 95% CI = [-0.135, -0.021]), supporting Hypothesis 6, indicating that organizational trust moderated the indirect effect of psychological resilience on job burnout through occupational stress.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The results of this study make several important contributions to the theoretical understanding of the complex relationships between psychological resilience, job burnout, occupational stress, and organizational trust. First, the finding that psychological resilience directly negatively predicts job burnout is consistent with Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, which posits that psychological resilience as a personal resource can help healthcare workers more effectively cope with work challenges and prevent resource depletion [

10]. Additionally, this finding echoes the negative correlation between psychological resilience and job burnout found in previous research [

12,

14,

32], confirming the role of psychological resilience as an important protective factor against job burnout in healthcare workers.

Second, this study confirmed the partial mediating role of occupational stress in the relationship between psychological resilience and job burnout, extending previous understanding of the direct relationships between these variables. This suggests that psychological resilience not only directly alleviates job burnout but also indirectly influences job burnout by reducing perceived occupational stress. This mediating pathway supports the transactional stress model of Lazarus and Folkman [

9], which emphasizes how individual traits (such as psychological resilience) influence the assessment of and response to potential stressors.

Third, this study found that organizational trust moderated the relationship between psychological resilience and occupational stress, with the negative impact of psychological resilience on occupational stress being stronger under conditions of high organizational trust. This result is consistent with the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model, which posits that job resources (such as organizational trust) can enhance the effectiveness of personal resources [

18].

Finally, this study proposed and validated a moderated mediation model, integrating individual factors (psychological resilience) and organizational factors (organizational trust) in their impact on healthcare workers’ job burnout. The results showed that organizational trust moderated the indirect effect of psychological resilience on job burnout through occupational stress, with this indirect effect being stronger in high-trust environments. This finding highlights the importance of the interaction between individual resources and organizational environment in understanding occupational health outcomes, providing a more integrated theoretical framework for future research.

5.2. Practical Implications

The results of this study offer several practical implications for healthcare organization managers, policy makers, and healthcare workers. First, given the important role of psychological resilience in reducing occupational stress and job burnout, healthcare organizations should prioritize implementing interventions aimed at enhancing employee resilience. Such interventions may include mindfulness training [

40], cognitive behavioral techniques [

41], and positive psychology interventions [

42], which have been proven effective in improving individuals’ ability to cope with stress.

Second, this study emphasizes that occupational stress is an important mediating mechanism through which psychological resilience affects job burnout, suggesting that organizations should take measures to reduce the sources of occupational stress faced by healthcare workers. This might include optimizing workflows, reasonably allocating workloads, providing adequate resources and support systems, and creating healthier work environments.

Third, this study found that organizational trust plays an important moderating role in the impact of psychological resilience on occupational stress, highlighting the critical importance of building and maintaining organizational trust in promoting employee well-being. Healthcare organization leaders should cultivate a culture of trust through transparent communication, fair decision-making processes, fulfilling commitments, and demonstrating genuine concern for employee well-being.

Finally, the moderated mediation model in this study suggests that multi-level interventions considering both individual and organizational factors may be most effective. Healthcare organizations should simultaneously focus on improving employees’ personal resilience capabilities and creating supportive organizational environments.

In addition, recent interdisciplinary studies have applied advanced analytical techniques—such as multi-modal data fusion, adaptive signal decomposition, and attention mechanisms—to improve health-related prediction and interpretation tasks [

43,

44]. These approaches offer methodological insights that may be extended to psychological modeling and burnout monitoring in occupational settings [

45,

46].

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Despite this study’s contributions to understanding the relationships between healthcare workers’ psychological resilience, occupational stress, organizational trust, and job burnout, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, this study employed a cross-sectional design, limiting inferences about causal relationships between variables. Future research should employ longitudinal designs or experimental methods to better determine the temporal order and causal relationships between these variables.

Second, all data in this study came from self-reports, which may present common method bias issues. Although this problem was mitigated through procedural controls (such as randomizing item order) and statistical tests, future research should consider combining objective indicators (such as physiological measurements, performance evaluations) and others’ assessments to provide more comprehensive measurements.

Third, although the sample size was sufficient for the planned analyses, participants were mainly from tertiary hospitals in China, which may limit the generalizability of the research findings. Future research should expand the sample scope to include different types of healthcare institutions and healthcare workers from different cultural backgrounds to verify the cross-cultural applicability of this study’s findings.

Fourth, although this study examined the role of occupational stress as a mediating variable, other important mediating mechanisms may exist. Future research could explore other potential mediating variables, such as work engagement, professional identity, and emotional regulation abilities, to more comprehensively understand how psychological resilience affects job burnout.

Finally, this study primarily focused on the role of psychological resilience as an individual trait, with less exploration of how to effectively enhance healthcare workers’ psychological resilience. Future research should assess the effectiveness of different types of resilience interventions in healthcare settings and determine which intervention strategies are most suitable for specific groups or situations.

6. Conclusions

This study, based on a moderated mediation model, explored the complex relationships between healthcare workers’ psychological resilience, occupational stress, organizational trust, and job burnout. The findings showed that psychological resilience both directly reduces job burnout and indirectly reduces job burnout by lowering occupational stress. Additionally, organizational trust enhanced the buffering effect of psychological resilience on occupational stress and moderated the indirect effect of psychological resilience on job burnout through occupational stress. These findings emphasize the importance of simultaneously attending to individual psychological resources and organizational environmental factors in preventing job burnout among healthcare workers.

From a theoretical perspective, this study integrated individual-level and organizational-level factors, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms of job burnout development and prevention. From a practical perspective, the results suggest that healthcare organizations should adopt a two-pronged strategy, both enhancing employees’ psychological resilience capabilities and creating high-trust organizational environments, to maximally reduce occupational stress and prevent job burnout.

In the context of unprecedented challenges facing global healthcare systems, understanding and promoting healthcare workers’ psychological health and occupational well-being has become particularly critical. This study provides an empirical foundation for developing more effective intervention strategies that can enhance healthcare workers’ psychological resilience, improve work environments, and ultimately improve the quality and sustainability of healthcare services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Xiaotong Zhou; Data curation, Weitong Kong; Formal analysis, Hong Liu; Funding acquisition, Kalok Tong, Dong Chen and Chitin Hon; Investigation, Hong Liu, Yanxin Chen and Sengtong Hon; Methodology, Hong Liu; Project administration, Yiping Li, Weitong Kong, Kalok Tong, Dong Chen and Chitin Hon; Resources, Yiping Li and Yanxin Chen; Supervision, Weitong Kong, Kalok Tong, Dong Chen and Chitin Hon; Writing – original draft, Xiaotong Zhou and Hong Liu; Writing – review & editing, Xiaotong Zhou. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Science and Technology Development Fund of Macau SAR (Grant No. 0002/2024/RDP) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFE0214800).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all healthcare workers who participated in this study for their time and valuable contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COR |

Conservation of Resources |

| JD-R |

Job Demands-Resources |

| MBI |

Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| CD-RISC |

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale |

| SEM |

Structural Equation Modeling |

| CFA |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI |

Comparative Fit Index |

| RMSEA |

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

References

- Wallace, J.E.; Lemaire, J.B.; Ghali, W.A. Physician wellness: A missing quality indicator. The Lancet 2009, 374, 1714–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. Journal of Internal Medicine 2018, 283, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open 2020, 3, e203976–e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Yang, Y.z.; Zhang, X.M.; Xu, X.; Dou, Q.L.; Zhang, W.W.; Cheng, A.S. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: A cross-sectional survey. Epidemiology & Infection 2020, 148, e98. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, L.H.; Johnson, J.; Watt, I.; Tsipa, A.; O’Connor, D.B. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: A systematic review. PloS One 2016, 11, e0159015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Noseworthy, J.H. Addressing physician burnout: The way forward. JAMA 2017, 317, 901–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M. Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2006, 1094, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthar, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.; Becker, B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development 2000, 71, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 2011, 84, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, C.H.; Schoonover-Shoffner, K.; Kennedy, M.S. Moral distress: A catalyst in building moral resilience. American Journal of Nursing 2015, 115, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrogante, Ó. Relationship between resilience and burnout in nursing professionals. Enfermeria Clínica 2016, 26, 330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Khamisa, N.; Peltzer, K.; Ilic, D.; Oldenburg, B. Work related stress, burnout, job satisfaction and general health of nurses: A follow-up study. International Journal of Nursing Practice 2016, 22, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.f.; Cross, W.; Plummer, V.; Lam, L.; Luo, Y.h.; Zhang, J.p. The mediating role of perceived organizational support on the relationship between psychological capital and job burnout among Chinese nurses: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Nursing Management 2018, 26, 707–714. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C.; Gu, Q. Resilience at work: Building capability in the face of adversity. The Sage Handbook of Workplace Learning 2016, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Sitkin, S.B.; Burt, R.S.; Camerer, C. Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Job demands and job resources and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 2017, 22, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist 2004, 59, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F. Positive organizational behavior: Developing and managing psychological strengths. Academy of Management Perspectives 2002, 16, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Firtko, A.; Edenborough, M. Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2007, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, M.; Lowe, J.B. The resilient nurse: Empowering your practice. Springer Publishing Company 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Bradley, K.A.; Wipf, J.E.; Back, A.L. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Annals of Internal Medicine 2002, 136, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimiotti, J.P.; Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; Wu, E.S. Nurse staffing, burnout, and health care–associated infection. American Journal of Infection Control 2012, 40, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Ora, C.; Ball, J.; Reinius, M.; Griffiths, P. Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review. Human Resources for Health 2020, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, B.; Ma, W.; Sun, Q. Resilience and work engagement: A stochastic actor-based modeling of workplace relationships. Frontiers in Psychology 2019, 10, 1743. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, G.; Doust, J.; Steele, M. Resilience in medicine: a study of resilience in junior hospital doctors. International Journal of Medical Education 2013, 4, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Harker, R.; Pidgeon, A.M.; Klaassen, F.; King, S. Effectiveness of a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program on healthcare professionals in the midst of a crisis. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar]

- Mealer, M.; Burnham, E.L.; Goode, C.J.; Rothbaum, B.; Moss, M. The prevalence and impact of post traumatic stress disorder and burnout syndrome in nurses. Depression and Anxiety 2012, 29, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Stress at work. NIOSH Publication 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gray-Toft, P.; Anderson, J.G. The nursing stress scale: Development of an instrument. Journal of Behavioral Assessment 1981, 3, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVicar, A. Workplace stress in nursing: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2003, 44, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Izquierdo, M.; Rios-Risquez, M.I.; Aguinaga-Ontoso, E.; Sanchez-Ros, N. Burnout, work engagement and professional efficacy in nursing staff: The mediating role of organizational trust. Journal of Nursing Management 2018, 26, 697–706. [Google Scholar]

- Shockley-Zalabak, P.; Ellis, K.; Winograd, G. Organizational trust: What it means, why it matters. Organization Development Journal 2000, 18, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikens, K.A.; Astin, J.; Pelletier, K.R.; Levanovich, K.; Baase, C.M.; Park, Y.Y.; Bodnar, C.M. Mindfulness goes to work: Impact of an online workplace intervention. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2014, 56, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I.T.; Cooper, C.L.; Sarkar, M.; Curran, T. Resilience training in the workplace from 2003 to 2014: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 2015, 88, 533–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E. Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being; Simon and Schuster, 2011.

- Li, X.; He, H.; Huang, J.; Liu, R.; Qian, T.; Hon, C. ASFM-AFD: Multimodal Fusion of AFD-Optimized LiDAR and Camera Data for Paper Defect Detection. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2025, 74, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lin, Y.; He, W.; Liu, R.; Oliveira, A.L.; Qian, T.; Zheng, J.; Hon, C. Enhancing the Interpretation of Spirometry: Joint Utilization of n-Order Adaptive Fourier Decomposition and Deep Learning Techniques. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2025, 74, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yan, H.; Cui, K.; Li, Z.; Liu, R.; Lu, G.; Hsieh, K.C.; Liu, X.; Hon, C. A Novel Hybrid YOLO Approach for Precise Paper Defect Detection With a Dual-Layer Template and an Attention Mechanism. IEEE Sensors Journal 2024, 24, 11651–11669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, J. Joint attention mechanism for the design of anti-bird collision accident detection system. Electron. Res. Arch. 2022, 30, 4401–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).