Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

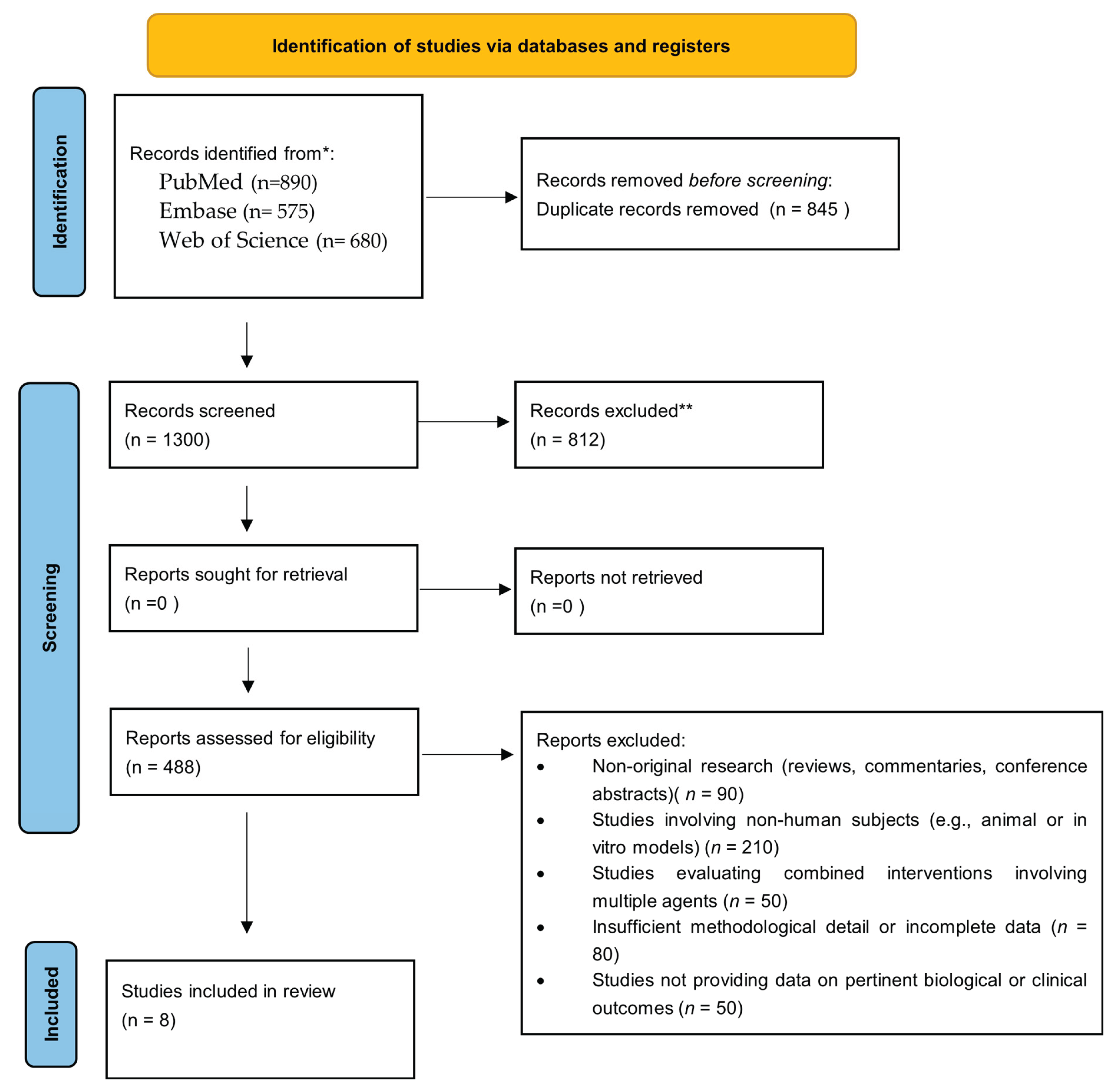

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Inflammatory Markers

3.2. Cervical and Uterine Parameters

3.3. Biochemical Biomarkers and Oxidative Stress

3.4. Obstetric and Neonatal Clinical Outcomes

3.5. Amniotic Immunological Profile

4. Discussion

5. Limits

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Amniotic Fluid |

| bLF | bovine lactoferrin |

| BV | bacterial vaginosis |

| ID | Iron deficiency |

| IDA | iron deficiency anemia |

| LF | lactoferrin |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MMP | matrix metalloproteinase |

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| OSI | Oxidative Stress Index |

| OSI | oxidative stress index |

| OxS | Oxidative Stress |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PTB | prevention of preterm birth |

| PTD | preterm delivery |

| PTL | Threatened Preterm Labor |

| rhLf | recombinant human lactoferrin |

| TAS | Total Antioxidant Status |

| TIMP | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase |

References

- WHO Recommendations for Care of the Preterm or Low Birth Weight Infant, 1st ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2022.

- World Health Organization, ‘Born too soon: the global action report on preterm birth’, p. 112, 2012, Accessed: Jul. 22, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44864.

- V. C. Ward et al., ‘Overview of the Global and US Burden of Preterm Birth’, Clin. Perinatol., vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 301–311, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Vogel, S. Chawanpaiboon, A.-B. Moller, K. Watananirun, M. Bonet, and P. Lumbiganon, ‘The global epidemiology of preterm birth’, Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol., vol. 52, pp. 3–12, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Karampitsakos et al., ‘The Impact of Amniotic Fluid Interleukin-6, Interleukin-8, and Metalloproteinase-9 on Preterm Labor: A Narrative Review’, Biomedicines, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 118, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Romero, J. Espinoza, L. F. Gonçalves, J. P. Kusanovic, L. Friel, and S. Hassan, ‘The role of inflammation and infection in preterm birth’, Semin. Reprod. Med., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 21–39, Jan. 2007. [CrossRef]

- L. Hu et al., ‘Relationship between gastrointestinal disturbances, blood lipid levels, inflammatory markers, and preterm birth’, J. Obstet. Gynaecol., vol. 45, no. 1, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Vajrychova et al., ‘Quantification of intra-amniotic inflammation in late preterm prelabour rupture of membranes’, Sci. Rep., vol. 15, p. 14814, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Jin and P. M. Kang, ‘A Systematic Review on Advances in Management of Oxidative Stress-Associated Cardiovascular Diseases’, Antioxidants, vol. 13, no. 8, p. 923, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. K. Actor, S.-A. Hwang, and M. L. Kruzel, ‘Lactoferrin as a natural immune modulator’, Curr. Pharm. Des., vol. 15, no. 17, pp. 1956–1973, 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. Legrand, ‘Overview of Lactoferrin as a Natural Immune Modulator’, J. Pediatr., vol. 173 Suppl, pp. S10-15, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Talbert, J. Lu, S. K. Spicer, R. E. Moore, S. D. Townsend, and J. A. Gaddy, ‘Ameliorating adverse perinatal outcomes with Lactoferrin: An intriguing chemotherapeutic intervention’, Bioorg. Med. Chem., vol. 74, p. 117037, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. S. Berthon, L. M. Williams, E. J. Williams, and L. G. Wood, ‘Effect of Lactoferrin Supplementation on Inflammation, Immune Function, and Prevention of Respiratory Tract Infections in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis’, Adv. Nutr., vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 1799–1819, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. D’Amico et al., ‘Role of lactoferrin in preventing preterm birth and pregnancy complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Minerva Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 75, no. 3, pp. 273–278, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Lee, K. H. Park, E. H. Jeong, K. J. Oh, A. Ryu, and A. Kim, ‘Intra-Amniotic Infection/Inflammation as a Risk Factor for Subsequent Ruptured Membranes after Clinically Indicated Amniocentesis in Preterm Labor’, J. Korean Med. Sci., vol. 28, no. 8, p. 1226, 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Giunta, L. Giuffrida, K. Mangano, P. Fagone, and A. Cianci, ‘Influence of lactoferrin in preventing preterm delivery: a pilot study’, Mol. Med. Rep., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 162–166, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Paesano, M. Pietropaoli, F. Berlutti, and P. Valenti, ‘Bovine lactoferrin in preventing preterm delivery associated with sterile inflammation’, Biochem. Cell Biol. Biochim. Biol. Cell., vol. 90, no. 3, pp. 468–475, Jun. 2012. [CrossRef]

- F. Vesce et al., ‘Vaginal lactoferrin administration before genetic amniocentesis decreases amniotic interleukin-6 levels’, Gynecol. Obstet. Invest., vol. 77, no. 4, pp. 245–249, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Trentini et al., ‘Vaginal Lactoferrin Modulates PGE2, MMP-9, MMP-2, and TIMP-1 Amniotic Fluid Concentrations’, Mediators Inflamm., vol. 2016, p. 3648719, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Locci et al., ‘Vaginal lactoferrin in asymptomatic patients at low risk for pre-term labour for shortened cervix: cervical length and interleukin-6 changes’, J. Obstet. Gynaecol. J. Inst. Obstet. Gynaecol., vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 144–148, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Trentini et al., ‘Vaginal Lactoferrin Administration Decreases Oxidative Stress in the Amniotic Fluid of Pregnant Women: An Open-Label Randomized Pilot Study’, Front. Med., vol. 7, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Miranda et al., ‘Vaginal lactoferrin in prevention of preterm birth in women with bacterial vaginosis’, J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. Off. J. Eur. Assoc. Perinat. Med. Fed. Asia Ocean. Perinat. Soc. Int. Soc. Perinat. Obstet., vol. 34, no. 22, pp. 3704–3708, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Maritati et al., ‘Influence of vaginal lactoferrin administration on amniotic fluid cytokines and its role against inflammatory complications of pregnancy’, J. Inflamm. Lond. Engl., vol. 14, p. 5, 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Kumar et al., ‘Proinflammatory cytokines found in amniotic fluid induce collagen remodeling, apoptosis, and biophysical weakening of cultured human fetal membranes’, Biol. Reprod., vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 29–34, Jan. 2006. [CrossRef]

- R. Menon and S. J. Fortunato, ‘Infection and the role of inflammation in preterm premature rupture of the membranes’, Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol., vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 467–478, Jun. 2007. [CrossRef]

- S.-S. Shim et al., ‘Clinical significance of intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes’, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 191, no. 4, pp. 1339–1345, Oct. 2004. [CrossRef]

- F. Vadillo-Ortega and G. Estrada-Gutiérrez, ‘Role of matrix metalloproteinases in preterm labour’, BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol., vol. 112 Suppl 1, pp. 19–22, Mar. 2005. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Lee, K. H. Park, E. H. Jeong, K. J. Oh, A. Ryu, and A. Kim, ‘Intra-amniotic infection/inflammation as a risk factor for subsequent ruptured membranes after clinically indicated amniocentesis in preterm labor’, J. Korean Med. Sci., vol. 28, no. 8, pp. 1226–1232, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Romero et al., ‘A fetal systemic inflammatory response is followed by the spontaneous onset of preterm parturition’, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 179, no. 1, pp. 186–193, Jul. 1998. [CrossRef]

- I. Tency et al., ‘Imbalances between Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) and Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases (TIMPs) in Maternal Serum during Preterm Labor’, PLoS ONE, vol. 7, no. 11, p. e49042, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. Sundrani, A. Narang, S. Mehendale, S. Joshi, and P. Chavan-Gautam, ‘Investigating the expression of MMPs and TIMPs in preterm placenta and role of CpG methylation in regulating MMP-9 expression’, IUBMB Life, vol. 69, no. 12, pp. 985–993, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Q. Rascón-Cruz et al., ‘Antioxidant Potential of Lactoferrin and Its Protective Effect on Health: An Overview’, Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 26, no. 1, p. 125, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Pino, G. Giunta, C. L. Randazzo, S. Caruso, C. Caggia, and A. Cianci, ‘Bacterial biota of women with bacterial vaginosis treated with lactoferrin: an open prospective randomized trial’, Microb. Ecol. Health Dis., vol. 28, no. 1, p. 1357417, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Artym, M. Zimecki, and M. L. Kruzel, ‘Lactoferrin for Prevention and Treatment of Anemia and Inflammation in Pregnant Women: A Comprehensive Review’, Biomedicines, vol. 9, no. 8, p. 898, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Otsuki, T. Nishi, T. Kondo, and K. Okubo, ‘Review, role of lactoferrin in preventing preterm delivery’, Biometals Int. J. Role Met. Ions Biol. Biochem. Med., vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 521–530, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Rosa, A. Cutone, M. S. Lepanto, R. Paesano, and P. Valenti, ‘Lactoferrin: A Natural Glycoprotein Involved in Iron and Inflammatory Homeostasis’, Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 18, no. 9, p. 1985, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).