1. Introduction

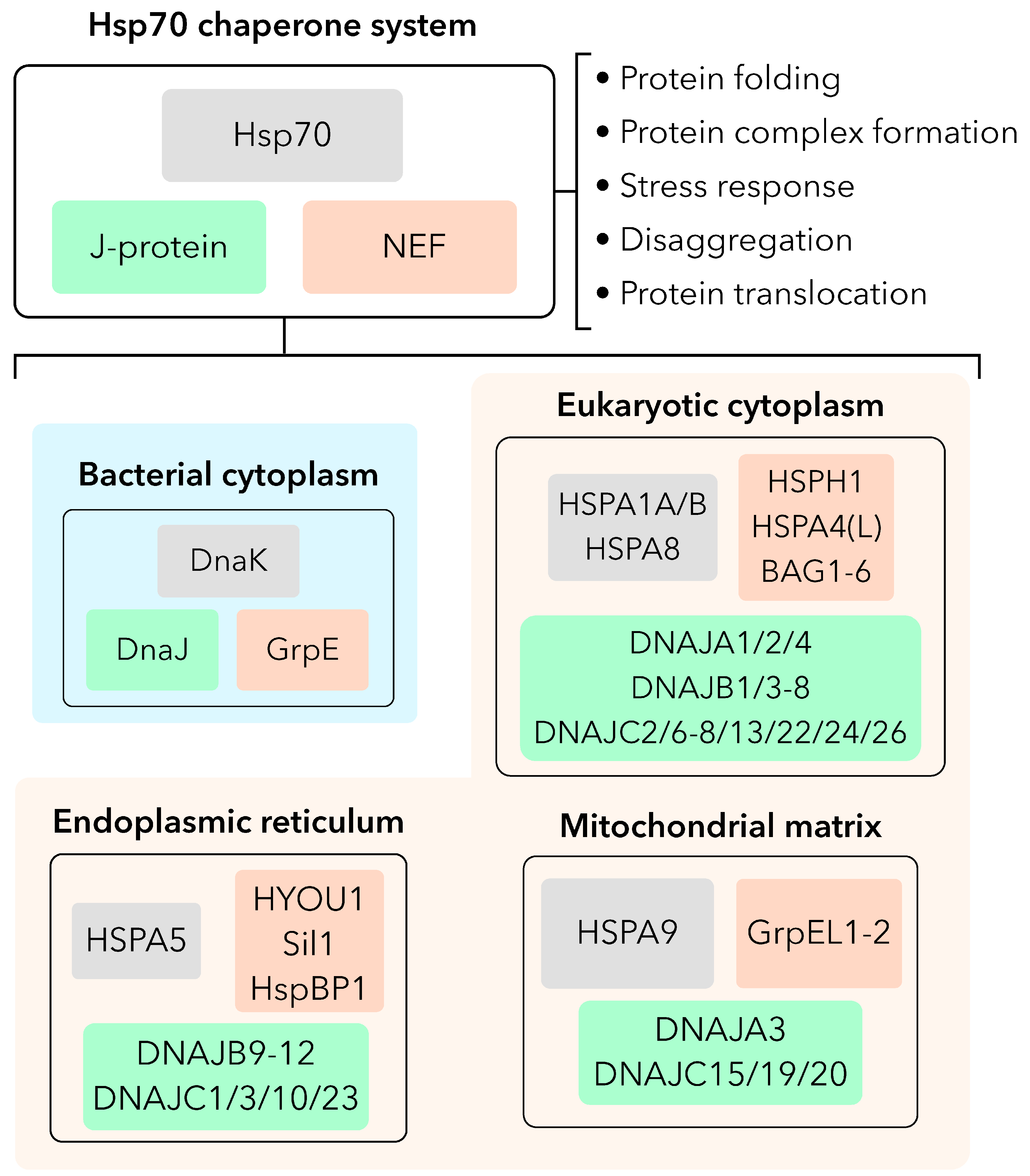

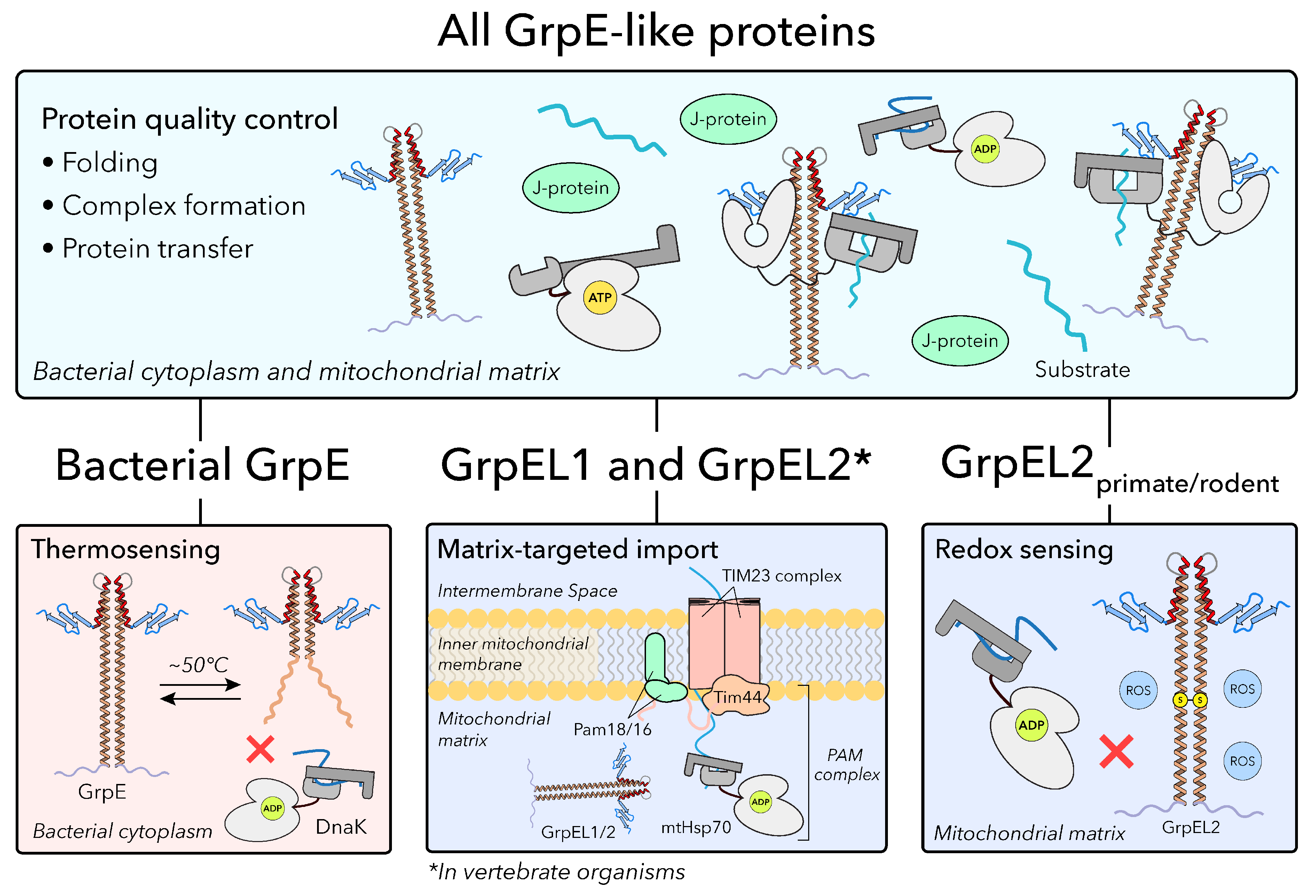

The heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) chaperone system represents a ubiquitous means for cells to maintain protein homeostasis, otherwise referred to as proteostasis, with essential roles in protein folding, stress responses, translocation, degradation, and quality control. The ubiquity of the Hsp70 chaperone system in nearly all known organisms highlights its essential role in supporting cellular homeostasis across all kingdoms of life.[

1,

2,

3] In bacteria, a single Hsp70 system, termed DnaK, suffices for general proteostasis, while eukaryotes have evolved compartment-specific Hsp70 isoforms.[

2,

4] These include cytoplasmic Hsp70 (HSPA1A/B) and heat shock cognate 70 (Hsc70/HSPA8) paralogs, endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP/Grp78/HSPA5), and mitochondrial Hsp70 (mtHsp70/Grp75/HSPA9/mortalin), each with tailored J-domain protein(s) (J-protein/Hsp40s) and nucleotide exchange factor (NEF) co-chaperones that facilitate ATP hydrolysis and nucleotide/substrate exchange, respectively

(Figure 1).[

5,

6,

7] Despite conserved ATPase-driven mechanisms, these systems exhibit striking regulatory diversity and substrate specificity, reflecting their adaptation to distinct proteostatic demands within different cellular environments.

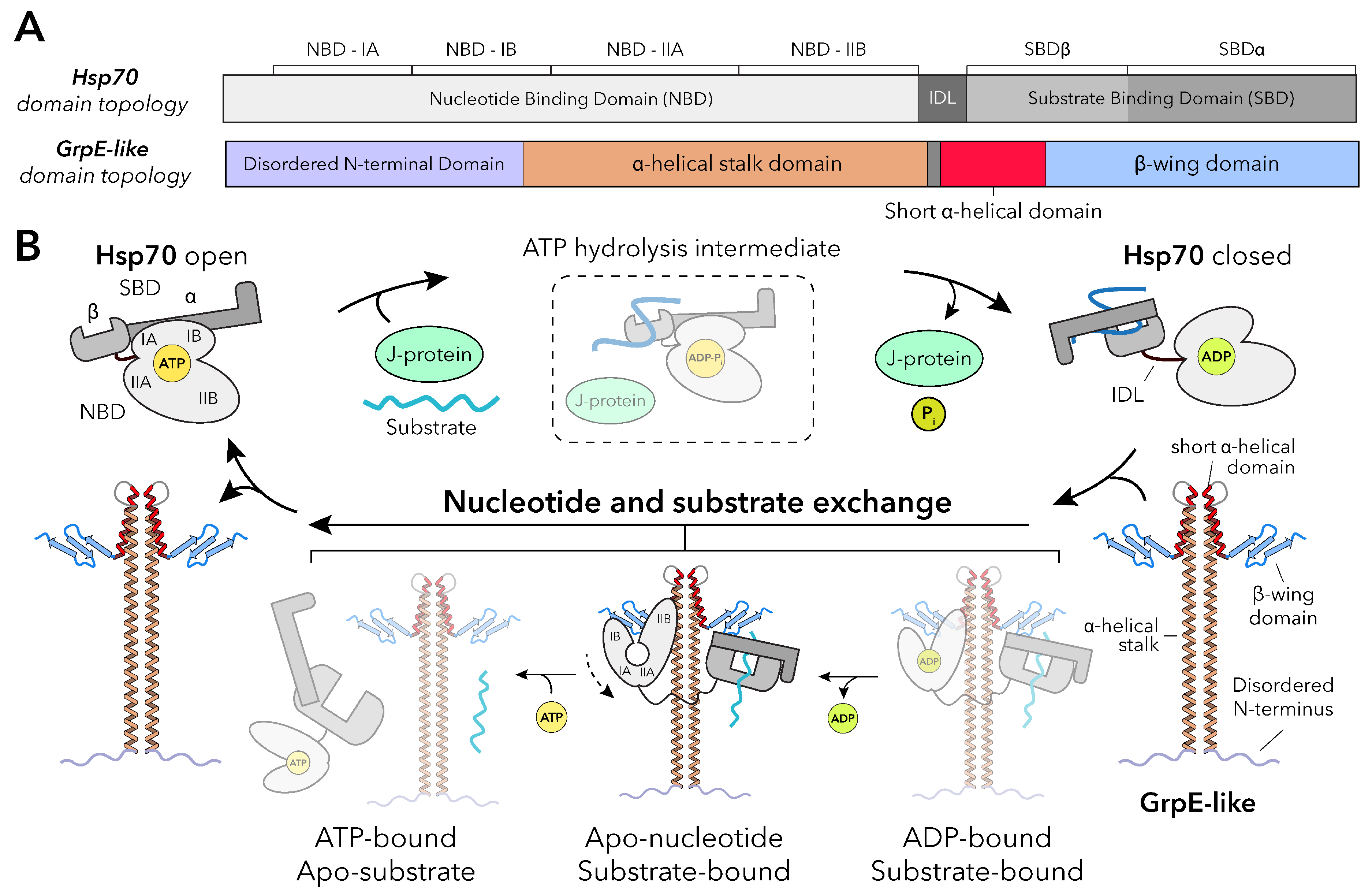

All known Hsp70s characterized to date harbor the same topology: a N-terminal nucleotide binding domain (NBD) that is responsible for ATP binding and hydrolysis, with a C-terminal protein substrate-binding domain (SBD) separated by a short interdomain linker (IDL)

(Figure 2A).[

3,

5,

6] In its canonical cycle, Hsp70 transitions between nucleotide-dependent open and protein/peptide substrate-bound closed states. In the open state, Hsp70 adopts a compact conformation in which an ATP-bound NBD and apo SBD are tightly associated, with the substrate-binding pocket of the SBD open and exposed to solvent

(Figure 2B). Upon peptide substrate binding to the SBD, ATP hydrolysis in the NBD is stimulated by a J-protein co-chaperone, triggering large allosteric changes that close the SBD to capture the protein substrate. In the closed state, the NBD and substrate-bound SBD are physically separated but remained tethered by the flexible IDL. Here, multivalent interactions with a NEF, GrpE-like in bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts, facilitate ADP release via mechanical opening of the NBD and allow for subsequent binding of ATP.[

8,

9] The Hsp70-GrpE complex has been shown to be ATP-sensitive, with addition of ATP resulting in rapid substrate release and dissociation of Hsp70 from GrpE. Importantly, ATP binding at the NBD is thought to initiate restructuring of Hsp70 back to the open state, resetting the chaperone for a new cycle of substrate binding

(Figure 2B).[

10,

11] Although this co-chaperoning function of GrpE-like proteins is conserved, these mechanisms have been assimilated into additional functions to meet diverse environmental needs.[

12,

13,

14,

15]

Investigations into the mechanism of action of GrpE-like NEFs have spanned more than three decades since the first NEF from

E. coli, growth requirement protein E (GrpE), was identified in the late 1980s.[

16,

17] Early studies elucidated the mechanism of nucleotide exchange in

E.coli Hsp70 (DnaK) and other bacterial species, yet the role of GrpE proteins in facilitating substrate release have remained incomplete.[

18] Furthermore, structural insights have been restricted to bacterial systems due to challenges in determining eukaryotic GrpE and Hsp70 structures.[

18,

19,

20,

21] However, recent structural elucidation of human mitochondrial Hsp70 (mtHsp70/mortalin) in complex with the mitochondrial-specific NEF, GrpEL1, has provided a near-complete mechanism of GrpE(L1) function, allowing for in-depth comparative analyses of GrpE-like proteins across kingdoms.[

22] In this review, we will examine the structural and functional diversification of GrpE-like NEFs, highlighting how these differences have evolved to support increasingly specialized cellular processes, particularly in higher eukaryotes. We will also discuss the remaining knowledge gaps of GrpE-like function related to regulation in response to cellular stress and roles in mitochondrial import processes.

2. Evolutionary Origins and Diversification of GrpE-Like NEFs

Generally, NEFs facilitate the exchange of nucleoside diphosphates (NDPs) for nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) – a process essential for numerous cellular functions requiring nucleotide exchange.[

10] NEFs comprise four structurally diverse families that have emerged to augment Hsp70 regulation, including GrpE-like, Hsp110/Grp170, HspBP1/Sil1, and BAG domains.[

7,

23,

24,

25,

26] While the localization and functional roles beyond nucleotide exchange differ for each NEF family, each of these families employs a distinct structural strategy to remodel the NBD of their Hsp70 partners to enable nucleotide release. Hsp110/Grp170 proteins are large Hsp70 relatives that act as both holdases and NEFs, stabilizing unfolded substrates while promoting ADP release through a conserved NBD–NBD interface.[

24] HspBP1 and its ER paralog Sil1 use armadillo-repeat folds to pry open the NBD.[

25]

BAG proteins, in contrast, employ a short

-helical BAG domain to bind and stabilize an open NBD conformation, often coupled to signaling modules that link Hsp70 activity to apoptosis, growth factor signaling, or proteasomal degradation.[

26] Compared with these families, GrpE-like NEFs are unique in their dimeric architecture and in their capacity to regulate both nucleotide and protein substrate release simultaneously. This distinction has facilitated members of the GrpE-like family, found in bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts, to adopt additional roles in protein translocation and oxidative stress responses with specific eukaryotic isoforms.[

7,

12,

15,

23]

The founding member of the GrpE-like family, GrpE from

E. coli, plays a central role in regulating the activity of bacterial DnaK/Hsp70 and is structurally and functionally conserved across prokaryotes.[

23] As mitochondria evolved from an alphaproteobacterial endosymbiont, many of the genes encoding chaperones and their cofactors were adapted to accommodate organellar integration via gene duplication, gene loss, and lateral gene transfer.[

12,

27,

28,

29] Ultimately, this engendered mitochondrial-specific variants of bacterial machineries with functional adaptations characteristic of present-day mitochondria. This evolutionary adaptation gave rise to mitochondrial-specific GrpEL1, a eukaryotic NEF that retains the core structural features of bacterial GrpE but has acquired new functionalities to meet the demands of mitochondrial protein import and stress regulation via mitochondrial Hsp70.[

12,

22,

30] GrpEL1 is conserved across nearly all opisthokonts, including yeast and metazoans, and is considered the primary mitochondrial NEF in these organisms.[

22,

31] In contrast, vertebrates possess a second mitochondrial GrpE paralog, GrpEL2, that likely emerged from a gene duplication event early in vertebrate evolution. Phylogenetic analyses reveal that while GrpEL1 orthologs are broadly conserved, GrpEL2 sequences are only detectable in vertebrate lineages.[

15,

32]

The divergence of GrpEL2 from GrpEL1 enabled the acquisition of specialized features, including a potential redox-sensing function and unique tissue expression patterns, discussed below in greater detail.[

15,

32] This functionalization event mirrors broader trends in the evolution of the mitochondrial proteostasis network, wherein core elements of the chaperone system have been repurposed to address compartment-specific roles. As such, the GrpE-like NEFs provide a model for studying how structural constraints and cellular demands shape the evolution of molecular machines. Ongoing efforts to map the distribution, sequence divergence, and functional specialization of GrpEL2 across vertebrates will shed light on the adaptive significance of this paralog and its emerging noncanonical roles.

3. Mechanisms of GrpE-Mediated Nucleotide and Substrate Release from Hsp70s

GrpE-like proteins share a conserved architecture across kingdoms comprising a disordered N-terminus, an

-helical stalk domain forming a pseudo coiled-coil in the functional dimer, a short

-helical domain, and a

-rich C-terminal “winged” domain

(Figure 2A and 3A).[

22] Homodimerization through the

-helical stalk domain yields a cruciform architecture with the short

-helical domains acting as hinges

to orient the

-rich winged domains outward

(Figure 3). While the GrpE-like topology is generally conserved, subtle structural variations across species and organellar isoforms confer unique functional properties. As most resolved structures of GrpE-like proteins are in complex with their Hsp70 partners, mechanistic insights into how the GrpE architecture engages the Hsp70 NBD and SBD to promote ADP and substrate release, respectively, can be gleaned

(Figure 3B).

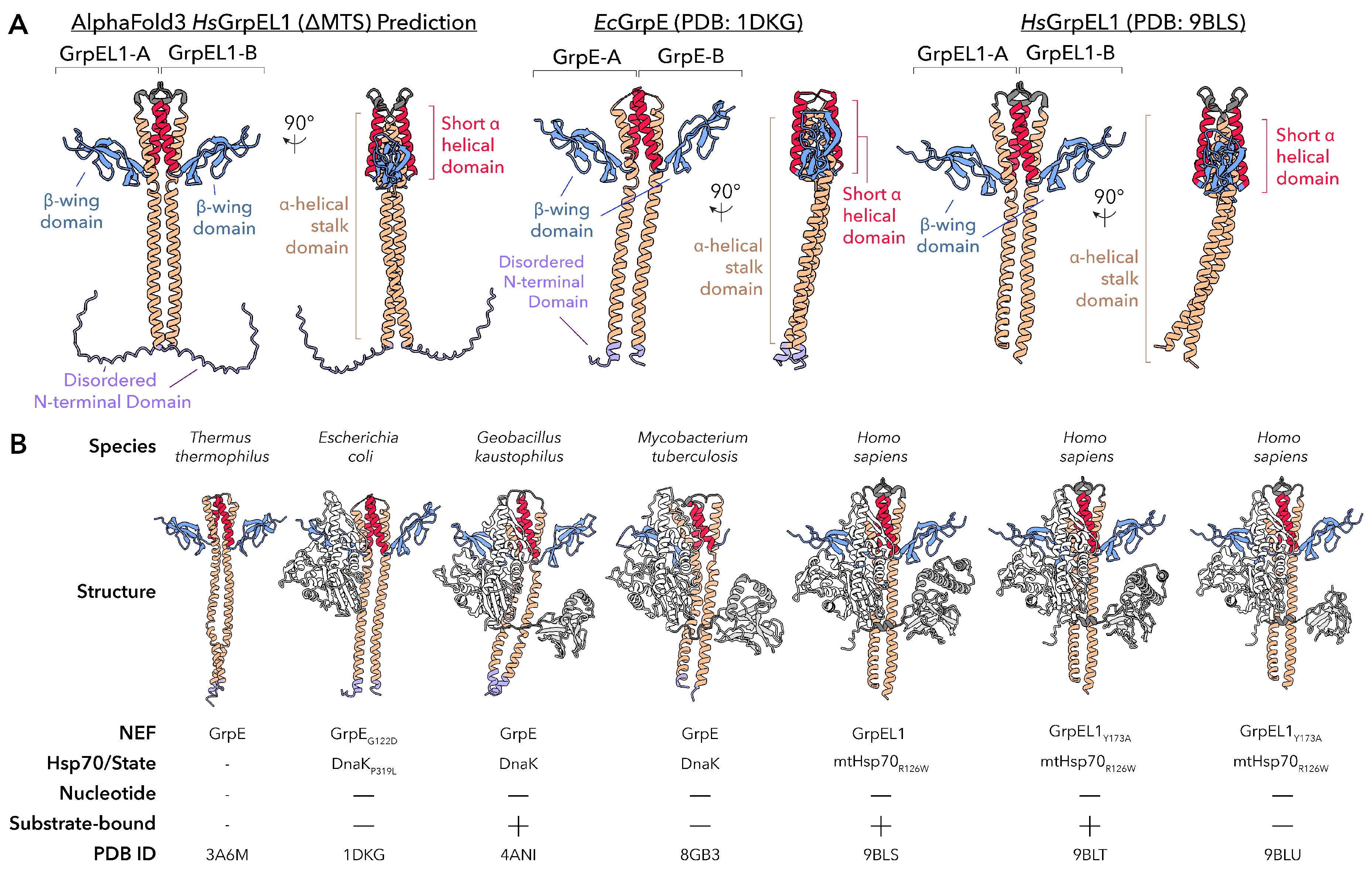

Earlier structural studies of GrpE-like NEFs across bacteria have provided foundational insights into the architecture and function of this family. Initial insights were obtained from the crystal structure of

E. coli GrpE in complex with DnaK (PDB ID: 1DKG), revealing how the

-wing domain of GrpE engages the Hsp70 NBD to wedge apart its lobes, establishing the basic mechanistic framework for how GrpE-like proteins facilitate nucleotide release.[

18] Subsequent structures of bacterial GrpE complexes, including those from

Thermus thermophilus (PDB ID: 3A6M)[

20],

Geobacillus kaustophilus (PDB ID: 4ANI)[

21], and

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (PDB ID: 8GB3)[

19], highlighted the conserved cruciform dimeric architecture while capturing distinct conformations of the Hsp70 nucleotide-binding and substrate-binding domains. Together, these studies established that GrpE-mediated allostery extends across both the NBD and SBD. It is important to note, however, that many of the earlier structures relied on truncations of the GrpE N-terminal disordered domain, stabilizing mutations, or were unable to visualize full-length components

due to proteolysis or dynamics, limiting the extent to which they captured dynamic states of the exchange cycle.

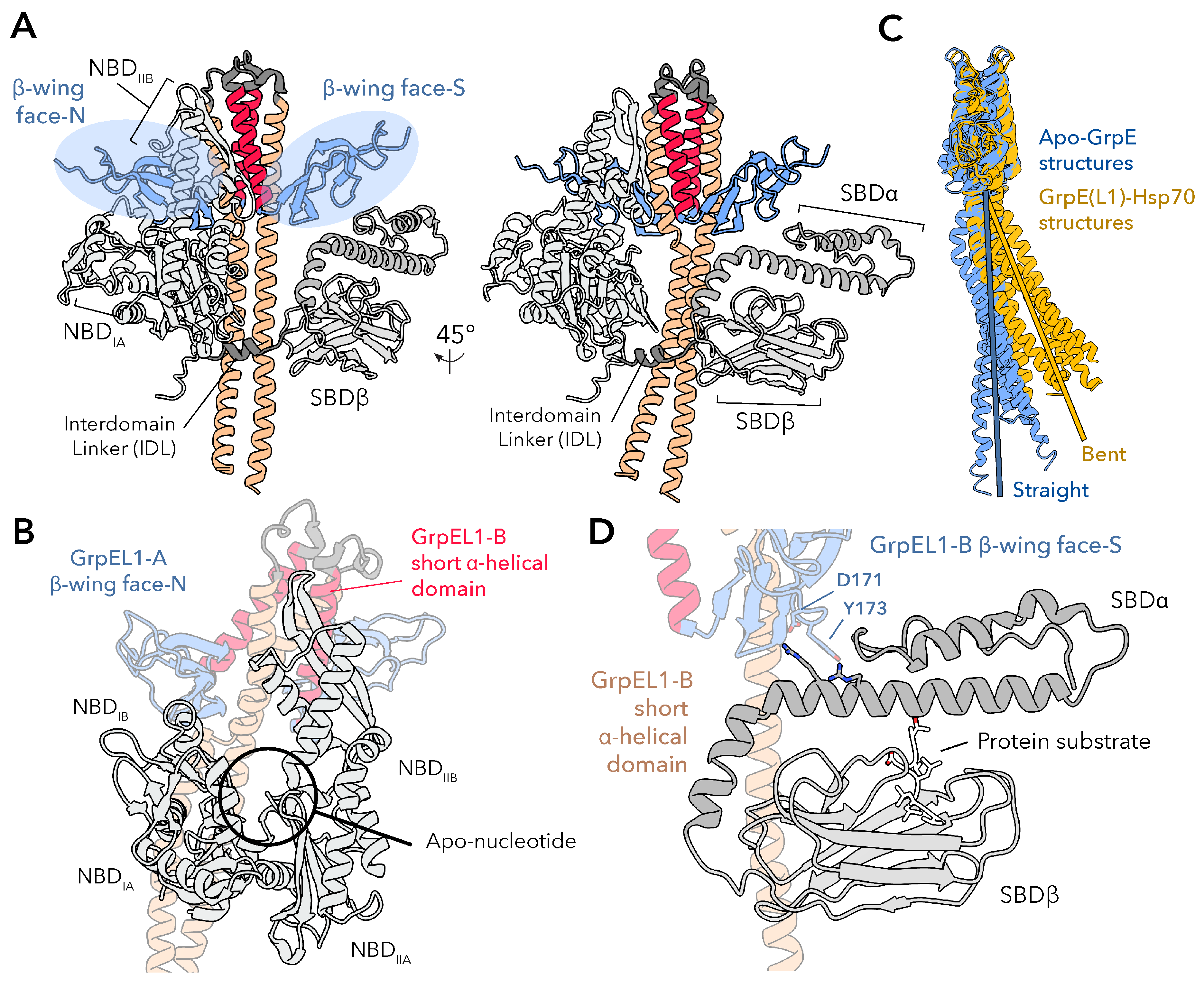

More recently, full-length cryogenic electron microscopy (cryoEM) structures of the human GrpEL1-mtHsp70 complex in distinct states (PDB IDs: 9BLS, 9BLT, 9BLU) have expanded these bacterial observations into the mitochondrial system, providing the most complete mechanistic description of how GrpE-like proteins engage their Hsp70 partners to facilitate nucleotide and protein substrate exchange via asymmetric

-wing interfaces.[

22] Overall, consistent with prior studies, two GrpEL1 protomers interact with a single mtHsp70 molecule via an extensive interface spanning all Hsp70 domains: the NBD lobes IA/B and IIA/B, the IDL, and both

- and

-subdomains of the SBD

(Figure 2 and 4A). Despite the apparent symmetry of the GrpE-like dimer, the GrpEL1 protomers in GrpEL1–mtHsp70 complexes expose unique faces of the

-wing domain to mtHsp70, rendering the homodimeric GrpEL1 an asymmetric complex. This asymmetric architecture enables precise interactions with the multi-domain mtHsp70 molecule, whereby the mtHsp70 NBD interacts with one protomer of GrpEL1, designated GrpEL1-A, via the NBD-interacting face of the

-wing domain, termed

-wing face-N, and the SBD interacts with the other GrpEL1 protomer, designated GrpEL1-B, via the SBD-interacting face of the

-wing domain, termed

-wing face-S

(Figure 4A). Here, the NBD lobes IB and IIB are wedged apart via interactions with

-wing face-N, and with the short

-helical domain of GrpEL1-B.

Electrostatic and van der Waals interactions at these interfaces anchor GrpEL1 to the NBD lobes, stabilizing the apo-nucleotide NBD conformation

(Figure 4B). Downstream of the NBD, the conserved Hsp70 IDL interacts with the

-helical stalk domain, resulting in a distinct bend in the stalk

(Figure 4C). This bending enables simultaneous interactions between the

-wing face-S of GrpEL1-B and SBD

, stabilizing Hsp70 substrate binding. A conserved aspartic acid (Asp171 in human GrpEL1) and partially conserved tyrosine residue (Tyr173 in human GrpEL1) at this interface interact with positively charged arginine and lysine residues that extend from the SBD

subdomain

(Figure 4D). Thus, GrpEL1 coordinates nucleotide and substrate release by unlocking the NBD while stabilizing SBD substrate engagement, synchronizing both steps of the Hsp70 exchange cycle. ATP binding then triggers allosteric rearrangements that facilitates complex dissociation, substrate release, and resetting of Hsp70 for another round of chaperone activity. Together, these complementary structures across bacteria and eukaryotic systems serendipitously sample distinct steps of the Hsp70 cycle, offering a patchwork of mechanistic insights that set the stage for full-length structural analyses. With the structural basis for GrpE-mediated nucleotide and substrate release fully visualized, these findings establish a mechanistic framework in which GrpE-like NEFs act as both catalytic and regulatory elements in the Hsp70 cycle, potentially tunable by redox state or cofactor remodeling.

4. Functionally Divergent Roles of the Disordered N-Terminus

The N-terminus of GrpE proteins typically comprise 40-50 unstructured amino acids of varying length, complexity, and disparate functions

(Figure 2A, 3A).[

12,

19,

34,

35] Previous studies have demonstrated that the N-terminus of bacterial GrpE contributes to substrate release from DnaK. Specifically, early studies observed that truncation of the

E. coli GrpE N-terminus reduced its ability to stimulate substrate dissociation from DnaK.[

19,

23,

34,

35] Therein, it was proposed that the disordered N-terminus may act as a pseudo-substrate for the substrate-binding site of Hsp70, thereby competing with and displacing bound substrate peptides. Although Hsp70s preferentially bind short, commonly leucine-rich hydrophobic peptides, the high local concentration of the negatively charged GrpE N-terminus may nonetheless assist with substrate displacement.[

35,

36,

37] However, to date, there is no direct structural evidence supporting physical insertion of the GrpE N-terminus into the SBD substrate-binding cleft. All high-resolution structures of bacterial GrpE–DnaK complexes show the GrpE N-terminus as disordered and unresolved, and the modeled interface between GrpE and DnaK places the N-terminus distal from the SBD

(Figure 3).[

18,

19,

20,

21] Thus, if substrate displacement occurs via the N-terminus, it likely requires a significant degree of local flexibility or partial disengagement from the

-wing domain, which normally orients the N-terminal stalks away from the SBD.

Alternatively, the effect may be indirect, mediated by global conformational changes upon GrpE binding that allosterically destabilize substrate occupancy in the SBD.

Given the high sequence diversity of the GrpE-like N-terminus (31.6% identical), it remains unclear whether all GrpE homologs have this capability. In eukaryotic homologs, such as mitochondrial GrpEL1 and GrpEL2, this mechanism remains speculative. In particular, in mitochondrially-targeted GrpE species, the first 30 amino acids of the ∼50 amino acid disordered N-terminal domain encode for a mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS) that directs the protein through the presequence import pathway to the mitochondrial matrix.[

14,

22,

32] Following import through the inner mitochondrial membrane, mitochondrial processing peptidase (MPP) cleaves the MTS and allows for entry into the mitochondrial matrix.[

14] The remaining N-terminal residues are highly charged and do not appear to be conserved in bacterial species. To date, structural evidence of the disordered N-terminus interacting with the SBD, in either bacterial or eukaryotic

Hsp70-GrpE structures, is lacking and thus precludes definitive conclusions about its role in substrate displacement.

Taken together, while the bacterial GrpE N-terminus may act as a pseudo-substrate under certain conditions, such a mechanism has not been directly visualized and appears structurally constrained. In mitochondrial GrpEL(1/2) proteins, the absence of an extended, conserved, and charged N-terminal region, combined with recent structural data, refutes a conserved substrate displacement function. Nevertheless, further functional studies employing N-terminally modified GrpE(L1) variants would be valuable to investigate the possibility of its potential role in eukaryotic Hsp70 substrate displacement.

5. The Elongated Pseudo Coiled-Coil Alpha-Helical Domain’s Role in Dimerization and Hsp70 Binding

The elongated -helical stalk domain characteristic of GrpE proteins spans approximately 70 amino acids (∼20 alpha helical turns) and adopts a pseudo coiled-coil domain in the functional dimer, contributing extensively to the stabiliza-

tion of the homodimer through extensive buried surface area (

)

(Figure 2-4).

This domain is highly conserved across all GrpE members, with several residues showing high similarity or absolute conservation throughout the region (47.3% identical). In contrast to canonical coiled-coil domains, the GrpE-like pseudo coiled-coil is composed of two parallel alpha helices that are stabilized via internally facing hydrophobic residues and do not exhibit the ultra-twist characteristic of coiled-coil domains

(Figure 3).[

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] Interestingly, the degree of bending of the helices varies among available experimental structures and is significantly influenced by interactions with an Hsp70 binding partner. In the crystal structure of

T. thermophilus GrpE (PDB ID: 3A6M)[

20], the

-helical stalk appears nearly in-plane with the rest of the protein, exhibiting only minor kinking. Similarly, in the crystal structure of

E. coli GrpE in complex with the NBD of DnaK (PDB ID: 1DKG)[

18], the long alpha helices remain straight and do not appear to extensively interact with the DnaK NBD. In contrast, structures of GrpE in complex with Hsp70s that contain the IDL and SBD regions (PDB IDs: 4ANI, 8GB3, 9BLS, 9BLT, and 9BLU)[

19,

21,

22] show distinct bending

(Figure 4C). In these cases, regions of the GrpE

-helical stalk interact with the interdomain linkers of Hsp70 proteins via hydrophobic interactions in bacteria and lower eukaryotes, or via salt bridges in higher eukaryotes. These interactions can induce significant bending, up to >25°, of the GrpE(L1) stalk relative to the plane of the GrpE(L1) protein.[

22] Structural analysis of GrpE-Hsp70 complexes suggests that the magnitude of this bending may depend on interactions with the

-subdomain of the SBD, further accentuating the bend.[

19,

22]

The short

-helical domain follows the

-helical stalk domain and is bridged by a short loop. This region is moderately conserved (32.2% identical) and consists of about six alpha helical turns in both bacterial and eukaryotic species

(Figure 2A, 3A). Packing interactions between the paired short

-helices create a defined crossing angle that reinforces the cruciform-like architecture of the dimer, extending beyond the stalk domain. These interactions include conserved hydrophobic residues that interdigitate across the dimer interface, as well as salt bridges that further anchor the helices.[

22] This stabilizing role is particularly important given the overall flexibility of GrpE, as it provides a potential pivot point that constrains the relative orientation of the

-wing domains away from the axis of dimerization. By fixing the spatial arrangement of the

-wings, the short

-helical domain ensures that each protomer presents a complementary surface to Hsp70, thereby enabling asymmetric engagement of the NBD and SBD. Interactions between the short alpha helices of each GrpE protomer contribute to the stabilization of the IIB NBD lobe in Hsp70. These stabilizing interactions include salt bridges, van der Waals interactions, and hydrophobic contacts, primarily bridging GrpE-B with the IIB NBD lobe

(Figure 4B). Along with interactions at the

-wing face-N, these contacts result in the opening of the Hsp70 NBD, exposing the nucleotide-binding pocket and facilitating ADP release. These interactions are observed in both bacterial and

human GrpE-Hsp70 structures and represent the primary mechanism of ADP dissociation from the NBD.

6. Dual Faces of the Asymmetric -Wing Domains

The

-wing domains are the most C-terminal regions of GrpE and resemble wings protruding from the short

-helical domain, away from the dimer interface, resulting in a cruciform-like architecture. This domain is highly conserved (52.0% identical) and forms crucial contacts with the NBD and SBD of Hsp70, which are essential for Hsp70’s chaperoning activity

(Figure 2A, 3A, and 4A). Recent structural evidence has shown that each face of the human GrpEL1

-wing domain,

-wing face-N and

-wing face-S, is distinct (PDB IDs: 9BLS, 9BLT, 9BLU)[

22]. This pseudo-symmetry of the GrpEL1 dimer appears critical in ensuring proper orientation and stoichiometry of the mtHsp70 interaction. Here, interaction of the mtHsp70 NBD with

-wing face-N positions the IDL and SBD for further stabilizing interactions with the

-helical stalk and

-wing face-S, respectively

(Figure 4). Moreover, these interactions, inducing bending of the

-helical stalk, may prevent binding of an additional mtHsp70 unit on the opposing solvent-exposed GrpEL1 interface. Collectively, the pseudo-symmetric architecture of the GrpEL1 dimer and non-equivalent

-wing surfaces, enable asymmetric engagement of a single Hsp70 protomer and ensure simultaneous access to both the NBD and SBD without steric clash.

Given the high sequence conservation of the

-wing domain across species and unique configuration of the exposed

-wing faces, it is likely that these solvent-exposed residues play critical roles in correctly orienting the distinct Hsp70 domains in homologous systems. While full-length structures of bacterial GrpE-Hsp70 complexes have yet to be resolved, existing experimental structures support the structural conservation of an asymmetric complex mediated by a pseudo-symmetric GrpE-like protein

(Figure 3).

7. Bacterial GrpE Can Act as a Thermosensor

Beyond its role as a NEF for Hsp70, GrpE has also been described as a thermosensor where

E. coli GrpE was shown to exhibit non-Arrhenius behavior, with decreased co-chaperone activity at elevated temperatures.[

13] Specifically, two thermal transitions were observed: the first was described as a fully reversible conformational change with a midpoint at ∼50°C, and the second, a partially irreversible transition near 75°C

(Figure 5). These findings were later elaborated to determine that the first transition resulted from an unwinding of the

-helical stalk domain of GrpE, and the second transition resulted from unfolding of the shorter

-helical domain.[

38] Based on these results, the

-helical stalk was proposed to function as the thermosensing domain via a reversible and gradual helix-to-coil transition. A similar phenomenon – two thermal transitions (at 90°C and 105°C) – was also observed in

T. thermophilus GrpE, a homolog from a heat-tolerant extremophile.[

39] However, it was proposed that a different unfolding sequence occurred, with the

-wings unfolding first while the

-helical stalk enabled reversible refolding of the

-wings. While this discrepancy may reflect adaptations specific to thermophilic organisms, it nonetheless supports the idea that bacterial GrpEs possess thermosensing capabilities

mediated by the reversible unfolding of specific structural domains. Structural information of bacterial Hsp70-GrpE complexes further support this hypothesis, revealing interactions between GrpE’s

-helical stalk and the IDL of Hsp70.[

19,

21] A helix-to-coil transition in this region would likely disrupt this interaction, impairing GrpE-mediated nucleotide exchange and substrate release. Under heat stress conditions, such inhibition could be beneficial, allowing Hsp70s to retain aggregation-prone substrates. Thus, reversible unfolding of GrpE may act as a regulatory mechanism that enables substrate sequestration during stress while maintaining GrpE levels required for basal activity. Although eukaryotic GrpE homologs may exhibit some sensitivity to thermal changes, their potential role as thermosensors remains largely unexplored. Instead, research has focused on their co-chaperone functions and emerging noncanonical roles

(Figure 5).

8. GrpE-Like NEFs Have Diversified to Accommodate Increasing Environmental Demands

Although the mechanism by which GrpE-like proteins interact with their Hsp70 binding partners to facilitate nucleotide and substrate exchange has been defined, GrpE-like species have evolved to adopt additional context specific functions. Notably, GrpEL1 has acquired an additional essential role involving the import of proteins targeted to the mitochondrial matrix via the presequence translocase-associated motor (PAM) complex

(Figure 5).[

31,

32,

40] This dual functionality highlights a specialized adaptation of GrpEL1 within the mitochondrial environment in addition to regulation of mtHsp70 for protein quality control. Further, vertebrates uniquely possess a second mitochondrial GrpE paralog termed GrpEL2 that, like GrpEL1, is thought to participate in the mtHsp70 chaperone system. Intriguingly, GrpEL2 has also been implicated in oxidative stress sensing, underscoring a potential functional adaptation specific to vertebrate species.[

15,

32,

40] However, the significance in GrpEL2’s co-chaperoning role relative to GrpEL1 remains incompletely defined as evidence has shown GrpEL1, but not GrpEL2, to be indispensable for mitochondrial homeostasis.

9. The Presequence Translocase-Associated Motor (PAM) Complex and GrpEL1

Within the mitochondrial matrix, GrpEL1 not only functions as a canonical NEF for mtHsp70, but also serves as an essential component of the mitochondrial matrix-localized PAM complex, which powers the import of nuclear-encoded preproteins bearing a MTS.[

12,

40] The PAM complex operates downstream of the translocase

of the inner mitochondrial membrane-23 (TIM23 complex) and is responsible for the ATP-dependent translocation of matrix-destined polypeptides across the inner membrane

(Figure 5). The core components of the PAM complex include mtHsp70, GrpEL1, Pam18, Pam16, and Tim44. Pam18 is a J-domain protein that stimulates the ATPase activity of mtHsp70, while Pam16 acts as a regulatory partner that modulates this activity.[

12,

41,

42,

43] Tim44, a peripheral membrane protein, serves as a scaffold that anchors the mtHsp70-GrpEL1 machinery to the inner mitochondrial membrane and coordinates the handoff of preproteins emerging from the translocase channel

(Figure 5).[

12,

40] GrpEL1 plays a critical role in recharging mtHsp70 by promoting the release of ADP and facilitating ATP rebinding, thereby resetting the chaperone for successive rounds of substrate capture during translocation. Genetic depletion of GrpEL1 in model organisms results in profound defects in matrix protein import, leading to protein aggregation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and organismal lethality.[

30,

31,

32,

44] While the biochemical role of GrpEL1 in nucleotide exchange is well established, the precise nature of its integration into the PAM complex remains incompletely defined. Co-immunoprecipitation and crosslinking studies suggest that GrpEL1 physically associates with Tim44, raising the possibility that GrpEL1 may be spatially restricted within the matrix to enhance the efficiency of import cycles.[

32] Moreover, it remains unclear how GrpEL1 simultaneously interacts with mtHsp70 and other PAM components, such as Pam18 or Pam16, during protein translocation. The extent to which GrpEL1 function in the PAM complex is modulated by redox status, import load, or cellular stress also remains an open question. Future work combining

in situ structural analysis, proximity labeling, and time-resolved import assays will be essential for delineating how GrpEL1 is functionally and spatially integrated into the PAM machinery.

10. Vertebrates Harbor Two GrpE-Like Homologs with Specialized Roles

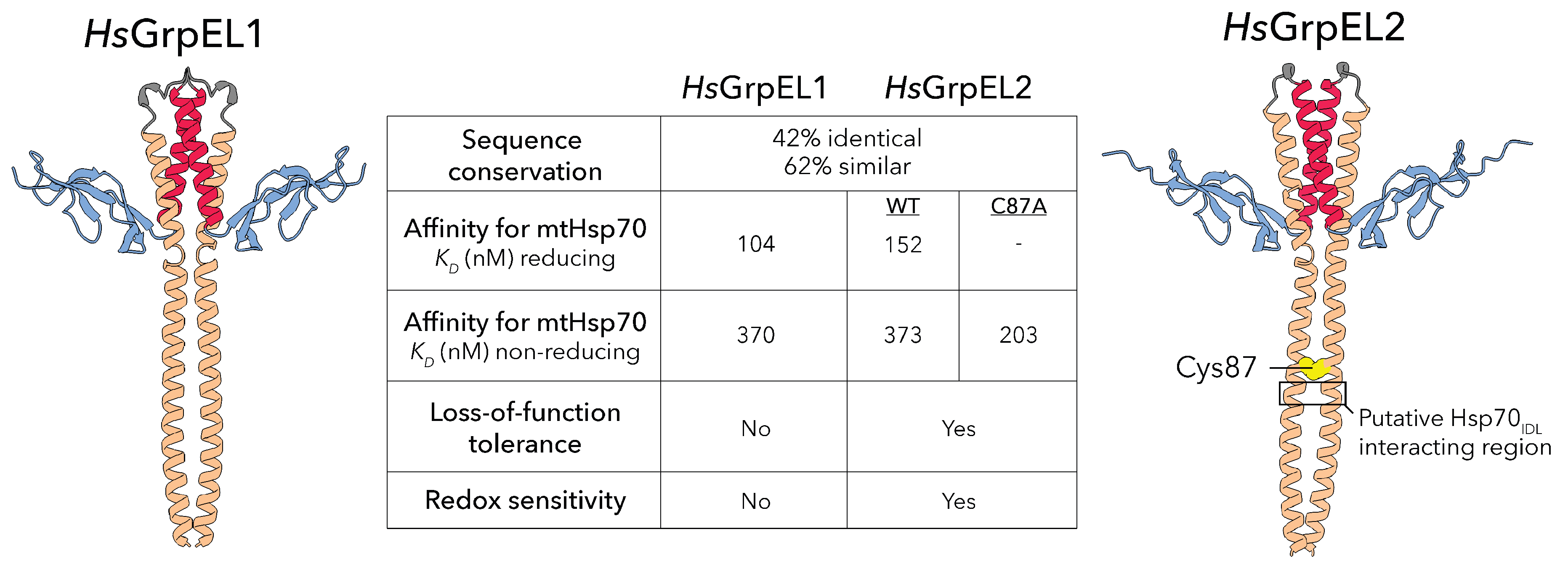

The eukaryotic GrpE homologs, GrpEL1 and GrpEL2, are differentially found in eukaryotes with GrpEL1 ubiquitous in higher eukaryotes whereas concurrent GrpEL1 and GrpEL2 expression is specific to vertebrates.[

15,

31,

32,

44] In humans, these paralogs share 42% sequence identity and 62% sequence similarity, and both follow the mitochondrial presequence import pathway, with final maturation occurring in the mitochondrial matrix. Functionally, both GrpEL1 and GrpEL2 can act as NEFs in the canonical Hsp70 chaperone cycle, promoting protein homeostasis through direct interaction with mtHsp70.[

32] A recent study examined the binding affinities of GrpEL1 and GrpEL2 for mtHsp70, and found that human GrpEL1 had approximately 10-fold higher affinity than GrpEL2 for ADP-bound mtHsp70, suggesting a preferred NEF in the mitochondrial matrix.[

44] It was later demonstrated that GrpEL2 is dispensable in cultured human cells, whereas loss-of-function variants of GrpEL1 are not tolerated.[

15] In a mouse model, it was observed that a GrpEL1 knockout was embryonically lethal, and muscle-specific deletion resulted in rapid skeletal muscle atrophy and disorganization

(Figure 6).[

31] Despite their high sequence and structural similarity, GrpEL1 emerges as the essential and primary mitochondrial NEF. Nevertheless, the distinct properties of GrpEL2 suggest specialized roles that may uniquely contribute to vertebrate biology.

11. Specific GrpEL2 Species May Play a Role in Oxidative Stress Sensing

A unique feature of GrpEL2 that has garnered recent interest is its potential role as an oxidative sensor. In a recent study, it was demonstrated that GrpEL2 oligomerization in HEK293 cells is sensitive to H

2O

2 treatment.[

15] They identified Cys87, located in the

-helical stalk domain, as the residue responsible for disulfide bond formation between GrpEL2 protomers. Notably, Cys87 is conserved only in primate and rodent GrpEL2. In a follow-up study, it was determined that under non-reducing conditions, mutation of Cys87 to an alanine residue increased its binding affinity to mtHsp70 almost two-fold compared to wild-type, suggesting disulfide bond formation at Cys87 reduces GrpEL2’s affinity for ADP-bound mtHsp70.[

44] Structurally, the formation of a disulfide bond at this position could rigidify the GrpEL2 pseudo coiled-coil, maintaining a straight conformation that restricts bending of the

-helical stalk and limits interactions with the IDL of mtHsp70

(Figure 6). This hypothesis is supported by structural data from GrpE(L1)-Hsp70 complexes, which show that flexibility and bending of the GrpE(L1)

-helical stalk is critical for full complex formation.[

19,

21,

22] Similar to the thermosensing mechanism of bacterial GrpE, reduced interaction between substrate-bound Hsp70 and GrpEL2 under oxidative conditions could prevent premature release of aggregation-prone substrates, maintaining protein homeostasis. Given Cys87’s exclusivity to GrpEL2 in primates and rodents, it has been proposed that this oxidative regulation may have evolved in longer-lived species with higher metabolic activities and elevated levels of reactive oxygen species.[

44] However, further studies are needed to determine whether physiological levels of oxidative stress are sufficient to induce disulfide bond formation and how such conditions affect the co-chaperone functions and abundance of both GrpEL1 and GrpEL2.

12. Potential GrpEL1-GrpEL2 Heterodimer

Given their high sequence identity, structural conservation, and co-localization within the mitochondrial matrix, it is not unreasonable to speculate that GrpEL1 and GrpEL2 may form hetero-oligomeric complexes under certain conditions. Indeed, there is evidence supporting the formation of a human GrpEL1-GrpEL2 hetero-oligomer. One such study identified a GrpEL1-GrpEL2 hetero-oligomer that exhibited enhanced thermostability compared to either GrpEL1 or GrpEL2 homodimers.[

32] The authors propose that the formation of the hetero-oligomeric complex may increase the solubility of the aggregation-prone GrpEL1/2 proteins. They further demonstrate that this hetero-oligomer can associate with the Tim44 scaffold at the inner mitochondrial membrane and that this species retains its co-chaperoning activity of mtHsp70. This species has been proposed to be preferentially recruited to the PAM complex in environments of oxidative stress.

However, in an analysis involving several human cell lines, the presence of a human GrpEL1-GrpEL2 hetero-oligomer

could not be detected and only homodimers of GrpEL1 and GrpEL2 could be identified.[

15] Given the structural plasticity of GrpEL1 and its ability to form homodimers or hetero-oligomers with GrpEL2, it is possible that different GrpEL1-containing complexes are recruited under basal versus stress conditions. Taken together, the possibility of GrpEL1–GrpEL2 hetero-oligomerization adds another layer of regulatory complexity to this system, reinforcing the broader theme of GrpE-like NEFs as stress-responsive modulators of proteostasis. However, further studies investigating the significance, function, and abundance of a GrpEL1-GrpEL2 hetero-oligomer in the context of mtHsp70 would provide valuable insights into the role of hetero-oligomerization in mitochondrial import and the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis.

13. Regulation of GrpEL1 and GrpEL2 Expression and Stability

Beyond their structural and mechanistic distinctions, GrpEL1 and GrpEL2 are also subject to differential regulation at the transcriptional, translational, and possibly post-translational levels. Early transcriptomic analyses have indicated that GrpEL1 is broadly expressed across tissues, with highest abundance in metabolically active organs such as the heart, brain, kidney, and liver.[

15] In contrast, GrpEL2 exhibits a more restricted and variable expression profile, with relative enrichment in the pancreas, spleen, cerebrum, and thymus, suggesting a potential role in immune function or specialized metabolic pathways.[

15] To date, the regulatory mechanisms governing GrpEL1 and GrpEL2 expression remain largely unexplored. It is unknown whether either gene is induced in response to mitochondrial unfolded protein stress (UPR

mt), oxidative stress, or other cellular insults that perturb proteostasis. Promoter analyses and epigenomic profiling may reveal the presence of stress-responsive transcription factor binding motifs, such as those for CHOP, ATF4, or NRF2, which are commonly activated in response to mitochondrial dysfunction.

At the protein level, both GrpEL1 and GrpEL2 are aggregation-prone

in vitro, and their solubility is enhanced by co-expression or hetero-oligomerization.[

32] This suggests that expression balance and folding quality control are important determinants of GrpEL1/2 function. It is possible that mitochondrial proteases such as Lon or ClpXP modulate their turnover under stress conditions, though this remains speculative. Additionally, GrpEL2’s redox-sensitive Cys87 may also serve a regulatory role beyond functional modulation, potentially influencing its stability or oligomeric state in oxidative environments. Whether oxidative modification of GrpEL2 triggers degradation, sequestration, or altered import remains to be tested. These regulatory dimensions underscore the complexity of maintaining NEF homeostasis in mitochondria and highlight the need for systems-level analyses of GrpEL1/2 abundance, turnover, and stress responsiveness.

14. Disease Associations and Biomedical Implications

Although the roles of GrpEL1 and GrpEL2 have primarily been studied in the context of fundamental mitochondrial biology, emerging evidence points to their potential involvement in human disease. Loss-of-function studies in animal models underscore the essentiality of GrpEL1 and these phenotypes are consistent with its central role in matrix protein import and maintenance of mitochondrial proteostasis.[

30,

31,

32,

44] Given the high metabolic demands of muscle and neuronal tissues, impaired GrpEL1 function may contribute to or exacerbate pathologies in diseases such as mitochondrial myopathies and neurodegenerative disorders. GrpEL1 has also been implicated in human genetic diseases.[

45,

46] Moreover, GrpEL1 expression may be altered in cancer cells that exhibit reprogrammed mitochondrial metabolism.[

45] Whether GrpEL1 is dysregulated to support increased protein import or modulated to resist apoptosis remains to be determined.

GrpEL2, although dispensable in cell lines, may play a more prominent role in stress adaptation. The discovery that its redox-sensitive cysteine can modulate binding to mtHsp70 raises the possibility that GrpEL2 acts as a regulatory buffer under oxidative conditions.[

15,

32,

44] In long-lived species or tissues prone to high reactive oxygen species (ROS) exposure, such as immune cells or neurons, GrpEL2 might serve as a fine-tuner of mitochondrial proteostasis. While direct links to disease are currently lacking, perturbation of this redox regulation could theoretically influence susceptibility to conditions involving mitochondrial oxidative stress, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, or certain cancers.

In the cancer context, emerging evidence suggests that mitochondrial chaperones, including mtHsp70, may be co-opted to support tumorigenesis.[

47,

48] It is conceivable that altered expression of GrpEL1 or GrpEL2 contributes to this reprogramming. Targeting their interaction surfaces or redox-switch mechanisms could thus represent a novel therapeutic strategy for modulating mitochondrial protein homeostasis in disease.

15. Outstanding Questions and Future Directions

Over the past three decades, significant progress has been made in elucidating the structural mechanisms underlying the function of GrpE-like NEFs. However, several important questions remain unresolved. First, while the structural basis for nucleotide exchange and substrate release has been clarified, the precise mechanism by which ATP binding drives complex dissociation from Hsp70 and triggers substrate release is incompletely defined. Addressing this will require kinetic studies that capture the full chaperone cycle using labeled substrates and real-time tracking. Second, the role of GrpEL1 in the PAM complex remains incompletely mapped. Although interaction with Tim44 has been suggested, the full set of physical and functional interactions between GrpEL1 and other PAM components – including Pam18, Pam16, and mtHsp70 – has not been resolved.[

32] Determining how GrpEL1 is spatially recruited and retained at the inner membrane could yield critical insights into the regulation of matrix import. Third, the physiological relevance of GrpEL2 remains an open question. While GrpEL1 is essential, GrpEL2’s role appears more nuanced. Is it required only under stress conditions? Does it chaperone distinct substrates or contribute to specific mitochondrial functions? Likewise, the proposed GrpEL1-GrpEL2 hetero-oligomer remains controversial, with conflicting data regarding its presence and function in cells. Finally, the broader role of NEFs as regulatory hubs, rather than passive exchange factors, is gaining traction. Redox regulation, conformational tuning, and stress-responsive modulation all point to a more active role in controlling chaperone cycles. Future investigations using time-resolved cryoEM,

in situ crosslinking mass spectrometry, and proximity-based interactome mapping will be essential for disentangling these dynamic regulatory mechanisms.

As GrpE-like proteins continue to reveal layers of complexity, they serve as a paradigm for understanding how core molecular machines evolve, diversify, and adapt to maintain homeostasis in increasingly complex cellular environments.

Author Contributions

Project conceptualization was performed by M.A.M. and M.A.H. Project administration and funding acquisition was performed by M.A.H. M.A.M. and T.V.S. conducted analyses. All authors wrote and edited the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research described here includes local researchers from the University of California, San Diego. The roles and responsibilities of this research were agreed upon by all included authors.

Informed Consent Statement

All the authors listed have approved the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to members of the Herzik lab for providing valuable feedback on this manuscript, especially Suzanne Enos and Brian Cook for facilitating insightful discussions. Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with UCSF ChimeraX, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), with support from National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01-GM129325 and the Office of Cyber Infrastructure and Computational Biology, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. This work was funded by the NIH (R35-GM138206 to M.A.H., T32-GM008326 to M.A.M.), as well as the Searle Scholars Program (M.A.H.), the Cottrell Scholars Program (M.A.H.), and UCSD’s Triton Research & Experiential Learning Scholars (TRELS) Program (T.V.S.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Macario, A.J.; Brocchieri, L.; Shenoy, A.R.; De Macario, E.C. Evolution of a Protein-Folding Machine: Genomic and Evolutionary Analyses Reveal Three Lineages of the Archaeal hsp70(dnaK) Gene. 63, 74–86. [CrossRef]

- Calloni, G.; Chen, T.; Schermann, S.; Chang, H.c.; Genevaux, P.; Agostini, F.; Tartaglia, G.; Hayer-Hartl, M.; Hartl, F. DnaK Functions as a Central Hub in the E. coli Chaperone Network. 1, 251–264. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fernández, M.R.; Gragera, M.; Ochoa-Ibarrola, L.; Quintana-Gallardo, L.; Valpuesta, J.M. Hsp70 – a master regulator in protein degradation. 591, 2648–2660. [CrossRef]

- Schönfeld, H.J.; Schmidt, D.; Schröder, H.; Bukau, B. The DnaK Chaperone System of Escherichia coli: Quaternary Structures and Interactions of the DnaK and GrpE Components. 270, 2183–2189. [CrossRef]

- Kampinga, H.H.; Craig, E.A. The HSP70 chaperone machinery: J proteins as drivers of functional specificity. 11, 579–592. [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, R.; Nillegoda, N.B.; Mayer, M.P.; Bukau, B. The Hsp70 chaperone network. 20, 665–680. [CrossRef]

- Bracher, A.; Verghese, J. Nucleotide Exchange Factors for Hsp70 Molecular Chaperones: GrpE, Hsp110/Grp170, HspBP1/Sil1, and BAG Domain Proteins. In The Networking of Chaperones by Co-Chaperones; Edkins, A.L.; Blatch, G.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing; Vol. 101, pp. 1–39. Series Title: Subcellular Biochemistry. [CrossRef]

- Szabo, A.; Langer, T.; Schröder, H.; Flanagan, J.; Bukau, B.; Hartl, F.U. The ATP hydrolysis-dependent reaction cycle of the Escherichia coli Hsp70 system DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE. 91, 10345–10349. [CrossRef]

- Kityk, R.; Kopp, J.; Mayer, M.P. Molecular Mechanism of J-Domain-Triggered ATP Hydrolysis by Hsp70 Chaperones. 69, 227–237.e4. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.P.; Bukau, B. Hsp70 chaperones: Cellular functions and molecular mechanism. 62, 670. [CrossRef]

- Voos, W.; Gambill, B.D.; Laloraya, S.; Ang, D.; Craig, E.A.; Pfanner, N. Mitochondrial GrpE is present in a complex with hsp70 and preproteins in transit across membranes. 14, 6627–6634. [CrossRef]

- Craig, E.A. Hsp70 at the membrane: driving protein translocation. 16, 11. [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, J.P.; Jelesarov, I.; Schönfeld, H.J.; Christen, P. Reversible Thermal Transition in GrpE, the Nucleotide Exchange Factor of the DnaK Heat-Shock System. 276, 6098–6104. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, O.; Pfanner, N.; Meisinger, C. Mitochondrial protein import: from proteomics to functional mechanisms. 11, 655–667. [CrossRef]

- Konovalova, S.; Liu, X.; Manjunath, P.; Baral, S.; Neupane, N.; Hilander, T.; Yang, Y.; Balboa, D.; Terzioglu, M.; Euro, L.; et al. Redox regulation of GRPEL2 nucleotide exchange factor for mitochondrial HSP70 chaperone. 19, 37–45. [CrossRef]

- Zylicz, M.; Ang, D.; Georgopoulos, C. The grpE protein of Escherichia coli. Purification and properties. 262, 17437–17442. [CrossRef]

- Zylicz, M.; Ang, D.; Liberek, K.; Georgopoulos, C. Initiation of lambda DNA replication with purified host- and bacteriophage-encoded proteins: the role of the dnaK, dnaJ and grpE heat shock proteins. 8, 1601–1608. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.J.; Hayer-Hartl, M.; Liberto, M.D.; Hartl, F.U.; Kuriyan, J. Crystal Structure of the Nucleotide Exchange Factor GrpE Bound to the ATPase Domain of the Molecular Chaperone DnaK. 276, 431–435. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Fay, A.; Molina, P.S.; Kovach, A.; Glickman, M.S.; Li, H. Structure of the M. tuberculosis DnaK–GrpE complex reveals how key DnaK roles are controlled. 15, 660. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A.; Takumi, K.; Miki, K. Crystal Structure of a Thermophilic GrpE Protein: Insight into Thermosensing Function for the DnaK Chaperone System. 396, 1000–1011. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.C.; Naveen, V.; Chien, C.H.; Chang, Y.W.; Hsiao, C.D. Crystal Structure of DnaK Protein Complexed with Nucleotide Exchange Factor GrpE in DnaK Chaperone System. 287, 21461–21470. [CrossRef]

- Morizono, M.A.; McGuire, K.L.; Birouty, N.I.; Herzik, M.A. Structural insights into GrpEL1-mediated nucleotide and substrate release of human mitochondrial Hsp70. 15, 10815. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C. GrpE, a nucleotide exchange factor for DnaK. 8, 218. [CrossRef]

- Dragovic, Z.; Broadley, S.A.; Shomura, Y.; Bracher, A.; Hartl, F.U. Molecular chaperones of the Hsp110 family act as nucleotide exchange factors of Hsp70s. 25, 2519–2528. [CrossRef]

- Shomura, Y.; Dragovic, Z.; Chang, H.C.; Tzvetkov, N.; Young, J.C.; Brodsky, J.L.; Guerriero, V.; Hartl, F.; Bracher, A. Regulation of Hsp70 Function by HspBP1. 17, 367–379. [CrossRef]

- Alberti, S.; Esser, C.; Höhfeld, J. BAG-1—a nucleotide exchange factor of Hsc70 with multiple cellular functions. 8, 225. [CrossRef]

- Roger, A.J.; Muñoz-Gómez, S.A.; Kamikawa, R. The Origin and Diversification of Mitochondria. 27, R1177–R1192. [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, V.; Alcock, F.; Lithgow, T. Minor modifications and major adaptations: The evolution of molecular machines driving mitochondrial protein import. 1808, 947–954. [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, V.; Lithgow, T.; Waller, R.F. Modifications and Innovations in the Evolution of Mitochondrial Protein Import Pathways. In Endosymbiosis; Löffelhardt, W., Ed.; Springer Vienna; pp. 19–35. [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Gao, B.; Wang, Z.; You, W.; Yu, Z.; Shen, H.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. GrpEL1 regulates mitochondrial unfolded protein response after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in vivo and in vitro. 181, 97–108. [CrossRef]

- Neupane, N.; Rajendran, J.; Kvist, J.; Harjuhaahto, S.; Hu, B.; Kinnunen, V.; Yang, Y.; Nieminen, A.I.; Tyynismaa, H. Inter-organellar and systemic responses to impaired mitochondrial matrix protein import in skeletal muscle. 5, 1060. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Savanur, M.A.; Sinha, D.; Birje, A.; R, V.; Saha, P.P.; D’Silva, P. Regulation of mitochondrial protein import by the nucleotide exchange factors GrpEL1 and GrpEL2 in human cells. 292, 18075–18090. [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. 630, 493–500. [CrossRef]

- Moro, F.; Taneva, S.G.; Velázquez-Campoy, A.; Muga, A. GrpE N-terminal Domain Contributes to the Interaction with DnaK and Modulates the Dynamics of the Chaperone Substrate Binding Domain. 374, 1054–1064. [CrossRef]

- Brehmer, D.; Gässler, C.; Rist, W.; Mayer, M.P.; Bukau, B. Influence of GrpE on DnaK-Substrate Interactions. 279, 27957–27964. [CrossRef]

- Clerico, E.M.; Tilitsky, J.M.; Meng, W.; Gierasch, L.M. How Hsp70 Molecular Machines Interact with Their Substrates to Mediate Diverse Physiological Functions. 427, 1575–1588. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.P.; Gierasch, L.M. Recent advances in the structural and mechanistic aspects of Hsp70 molecular chaperones. 294, 2085–2097. [CrossRef]

- Gelinas, A.D.; Langsetmo, K.; Toth, J.; Bethoney, K.A.; Stafford, W.F.; Harrison, C.J. A Structure-based Interpretation of E.coli GrpE Thermodynamic Properties. 323, 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Groemping, Y.; Reinstein, J. Folding properties of the nucleotide exchange factor GrpE from Thermus thermophilus: GrpE is a thermosensor that mediates heat shock response. 314, 167–178. [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, J.B.; Brunstein, M.E.; Bozkurt, S.; Alves, L.; Wegner, M.; Kaulich, M.; Pohl, C.; Münch, C. Protein import motor complex reacts to mitochondrial misfolding by reducing protein import and activating mitophagy. 13, 5164. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dudek, J.; Guiard, B.; Pfanner, N.; Rehling, P.; Voos, W. The Presequence Translocase-associated Protein Import Motor of Mitochondria. 279, 38047–38054. [CrossRef]

- Hutu, D.P.; Guiard, B.; Chacinska, A.; Becker, D.; Pfanner, N.; Rehling, P.; Van Der Laan, M. Mitochondrial Protein Import Motor: Differential Role of Tim44 in the Recruitment of Pam17 and J-Complex to the Presequence Translocase. 19, 2642–2649. [CrossRef]

- Truscott, K.N.; Voos, W.; Frazier, A.E.; Lind, M.; Li, Y.; Geissler, A.; Dudek, J.; Müller, H.; Sickmann, A.; Meyer, H.E.; et al. A J-protein is an essential subunit of the presequence translocase–associated protein import motor of mitochondria. 163, 707–713. [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, P.; Stojkovič, G.; Euro, L.; Konovalova, S.; Wanrooij, S.; Koski, K.; Tyynismaa, H. Preferential binding of ADP -bound mitochondrial HSP70 to the nucleotide exchange factor GRPEL1 over GRPEL2. 33, e5190. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, B.; Mo, Q.; Wu, P.; Fang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Jin, X.; Gao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cao, Y.; et al. The LIV-1-GRPEL1 axis adjusts cell fate during anti-mitotic agent-damaged mitosis. 49, 26–39. [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Wu, X.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; Gu, F.; Tao, X.; Song, B.; Bai, L.; Li, D.; Shen, H.; et al. GrpEL1 overexpression mitigates hippocampal neuron damage via mitochondrial unfolded protein response after experimental status epilepticus. 206, 106838. [CrossRef]

- Albakova, Z.; Armeev, G.A.; Kanevskiy, L.M.; Kovalenko, E.I.; Sapozhnikov, A.M. HSP70 Multi-Functionality in Cancer. 9, 587. [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Xia, Y.; Shen, X.; Hua, W.; Shi, M.; Chen, L. HSPA9 contributes to tumor progression and ferroptosis resistance by enhancing USP14-driven SLC7A11 deubiquitination in multiple myeloma. 44, 115720. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).