Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

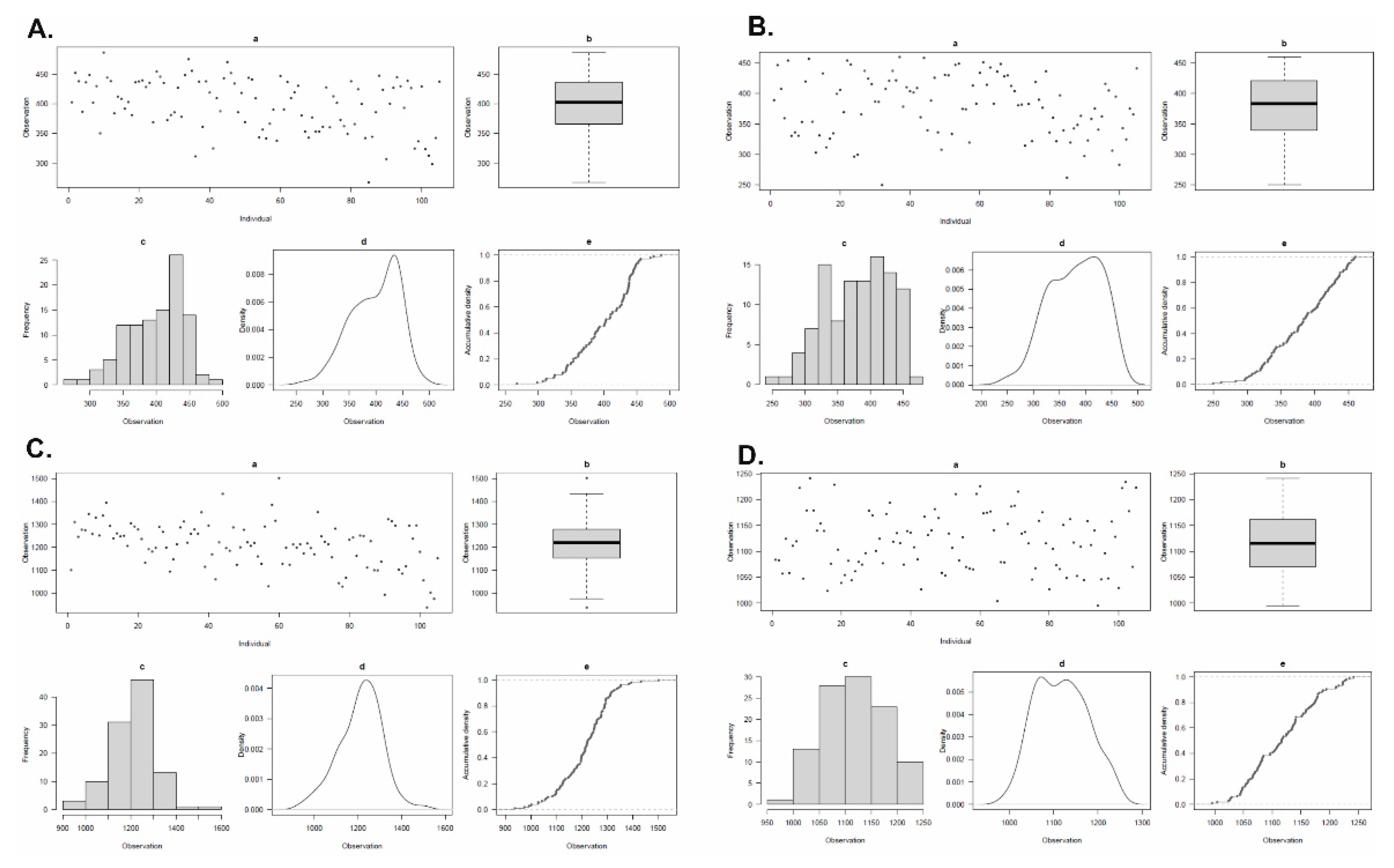

2.1. Variability for Grain Ca and Mg Concentration

| Source | Df | Ca_SS | Mg_SS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1 | 42.2* | 476* |

| Entry | 104 | 8.79* | 9.68 * |

| Replication | 2 | 10.3 | 60.5 |

| Year× Entry | 104 | 5.35* | 7.61* |

| SS: Sum of square; Df: degrees of freedom; significant at ** p <0.001. | |||

| Statistics | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLUP Ca | BLUP Mg | BLUP Ca | BLUP Mg | |

| Heritability | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.68 | 0.78 |

| Genotypic variance | 2312.00 | 10528.4 | 2786.74 | 4323.17 |

| Grand Mean | 398.62 | 1211.88 | 380.42 | 1118.02 |

| LSD | 49.83 | 73.2 | 49.36 | 85.21 |

| CV | 8.36 | 3.88 | 8.55 | 5.34 |

| LSD = Least significant difference; CV = Coefficient of variation | ||||

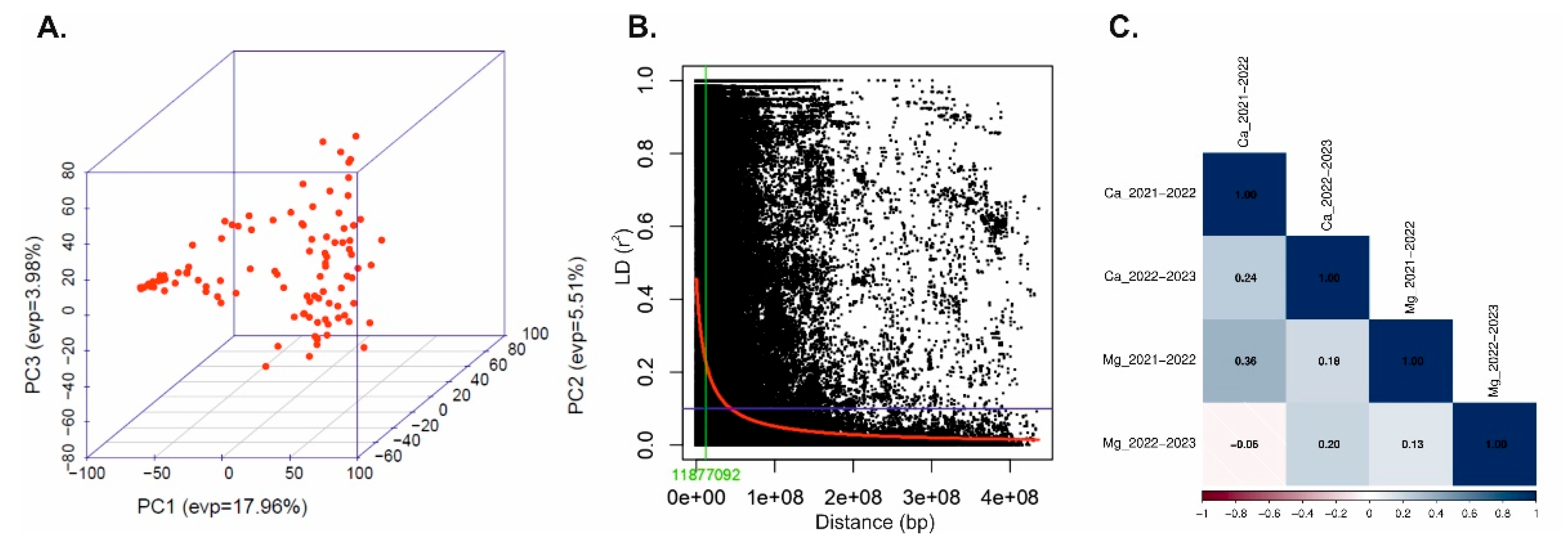

2.3. Population Structure Analysis

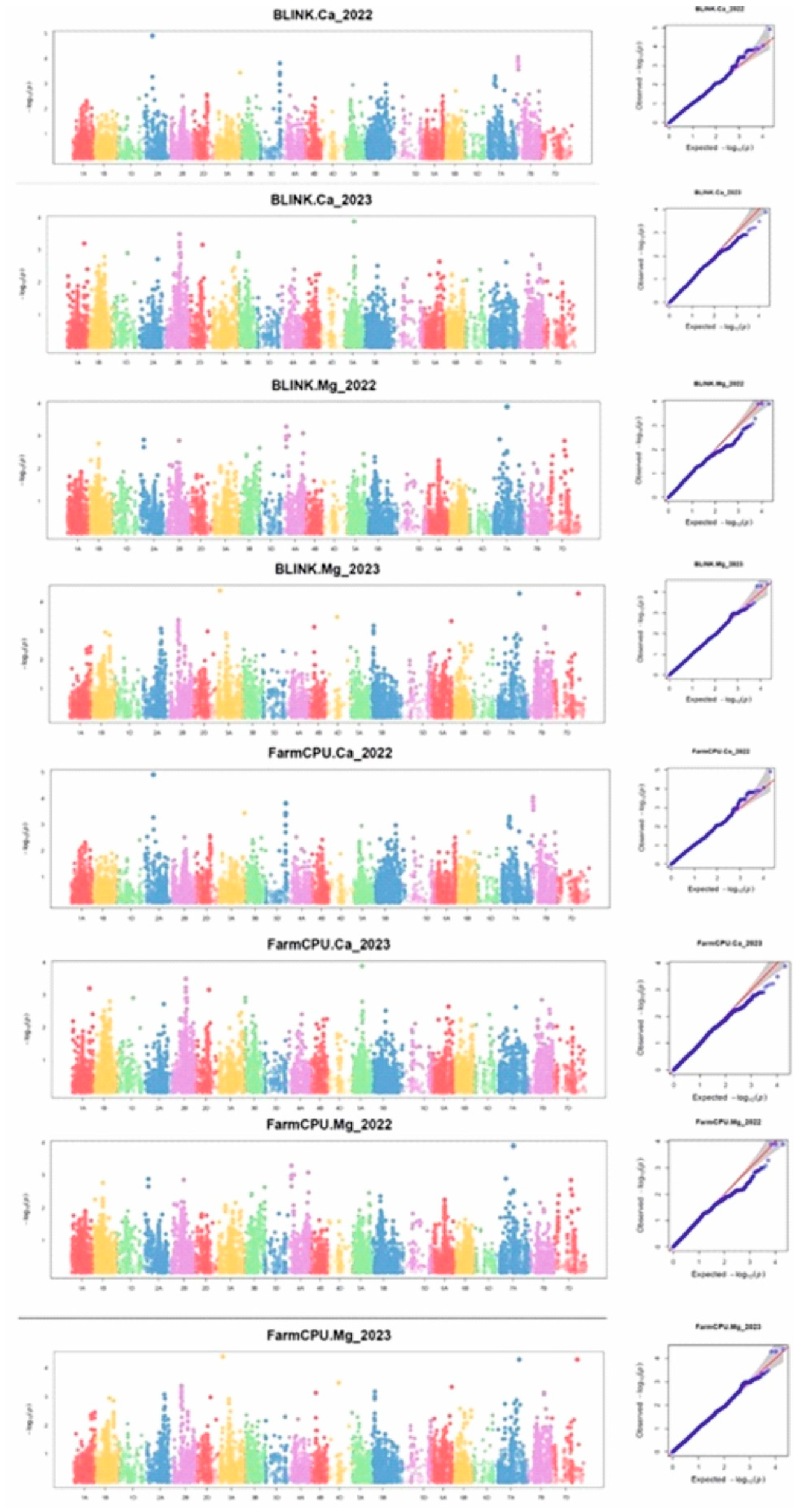

2.4. MTAs for the Target Trait Utilizing GWAS

2.4.1. MTAs for GCaC

2.4.2. MTAs for GMgC

2.4.3. Multi-Effect MTA Locus for Ca and Mg

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Genetic Material and Experimental Conditions

4.2. DNA Extraction and Genotyping

4.3. Elemental Analysis for GCaC and GMgC

4.3. Statistical Analyses

4.4. Population Structure, Kinship Matrix, and Principal Components Analyses (PCA)

4.5. Genome-Wide Association Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIC | Bayesian information criterion |

| BLINK | Bayesian-information and linkage disequilibrium iteratively nested keyway |

| BLUP | Best Linear Unbiased Prediction |

| Ca | Calcium |

| CIMMYT | International maize and wheat improvement center |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| FarmCPU | Fixed, and random model circulating probability unification |

| GCaC | Grain calcium content |

| GMgC | Grain magnesium content |

| GWAS | Genome wide association study |

| ICP-OES | Utilising inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectroscopy |

| IWIN | International wheat Improvement Network |

| LD | Utilizes linkage disequilibrium |

| LSD | Least significant difference |

| MAF | Minor allele frequency |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| MTAs | Marker trait associations |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| Q-Q | Quantile-Quantile |

| QTL | Quantitative trait loci |

| r2 | Pairwise squared allele-frequency correlations |

| REML | Restricted maximum likelihood |

| TASSEL | Trait Analysis by aSSociation, Evolution and Linkage |

| WAMI | Wheat association mapping initiative |

| BIC | Bayesian information criterion |

| BLINK | Bayesian-information and linkage disequilibrium iteratively nested keyway |

| BLUP | Best Linear Unbiased Prediction |

| Ca | Calcium |

| CIMMYT | International maize and wheat improvement center |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| FarmCPU | Fixed, and random model circulating probability unification |

| GCaC | Grain calcium content |

| GMgC | Magnesium content |

| GWAS | Genome wide association study |

| ICP-OES | Utilising inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectroscopy |

| IWIN | International wheat Improvement Network |

| LD | Utilizes linkage disequilibrium |

| LSD | Least significant difference |

| MAF | Minor allele frequency |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| MTAs | Marker trait associations |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| Q-Q | Quantile-Quantile |

References

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization 2025.

- Shewry, P.R. Wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 1537–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Fact sheets 2025.

- Weaver, C.M. Calcium. In Present Knowledge in Nutrition; Marriott, B.P., Birt, D.F., Stallings, V.A., Yates, A.A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2022; pp. 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mulet-Cabero, A.I.; Wilde, P.J. Role of calcium on lipid digestion and serum lipids: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). Food and nutrition board. Dietary reference intakes: calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin D and fluoride. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997.

- Rude, R.K. Magnesium. In modern nutrition in health and disease; Ross, A.C., Caballero, B., Cousins, R.J., Tucker, K.L., Ziegler, T.R., Eds.; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, Mass: Lippincott, 2012; pp. 159–75. [Google Scholar]

- Rude, R.K.; Singer, F.R.; Gruber, H.E. Skeletal and hormonal effects of magnesium deficiency. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2009, 28, 131–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, A.; Brazauskas, G.; Gaikpa, D.S.; Henriksson, T.; Islamov, B.; Jørgensen, L.N.; Koppel, M.; Koppel, R.; Liatukas, Ž.; Svensson, J.; Chawade, A. Genome-wide association analysis and genomic prediction for adult-plant resistance to Septoria tritici blotch and powdery mildew in winter wheat. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 661742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabieyan, E.; Bihamta, M.R.; Moghaddam, M.E.; Alipour, H.; Mohammadi, V.; Azizyan, K.; Javid, S. Analysis of genetic diversity and genome-wide association study for drought tolerance related traits in Iranian bread wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, W. ; Gataa, Zakaria.; Rachdad, F.E.; El Baouchi, A.; Kehel, Z.; Alemu, A. Single- and multi-trait genomic prediction and genome-wide association analysis of grain yield and micronutrient-related traits in ICARDA wheat under drought environment. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2023, 298, 1515–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnappa, G.; Khan, H.; Krishna, H.; Kumar, S.; Mishra, C.N.; Parkash, O.; Devate, N.B.; Nepolean, T.; Rathan, N.D.; Mamrutha, H.M.; Srivastava, P.; Biradar, S.; Uday, G.; Kumar, M.; Singh, G.; Singh, G.P. Genetic dissection of grain iron and zinc, and thousand kernel weight in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using genome-wide association study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabri, M.; El-Soda, M. Genome-wide association mapping of macronutrient mineral accumulation in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) grain. Plants 2024, 13, 3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadana, D.; Kaur, P.; Kaur, R.; Ravat, V.K. ; Ashutosh; Kumar, R.; Vasistha, N.K. Genome-wide association study for powdery mildew resistance in CIMMYT’s spring wheat germplasm. Plant Pathol. 2024, 74, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaler, A.S.; Gillman, J.D.; Beissinger, T; Purcell, L.C. Comparing different statistical models and multiple testing corrections for association mapping in soybean and maize. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A.L.; Patterson, N.J; Plenge, R.M.; Weinblatt, M.E.; Shadick, N.A.; Reich, D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, M.; Fan, B.; Buckler, E.S.; Zhang, Z. Iterative usage of fixed and random effect models for powerful and efficient genome-wide association studies. PloS Genet. 2016, 12, e1005767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Summers, R.M.; Zhang, Z. BLINK: a package for the next level of genome-wide association studies with both individuals and markers in the millions. Giga Sci. 2019, 8, giy154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Vasistha, N.K.; Ravat, V.K.; Mishra, V.K.; Sharma, S.; Joshi, A.K.; Dhariwal, R. Genome-wide association study reveals novel powdery mildew resistance loci in bread wheat. Plants 2023, 12, 3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, W.G.; Weir, B.S. Variances and covariances of squared linkage disequilibria in finite populations. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1988, 33, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkelish, A.; Alqudah, A.M.; Alomari, D.Z.; Alammari, B.S.; Alsubeie, M.S.; Hamed, S.M; Thabet, S.G. Targeting candidate genes for the macronutrient accumulation of wheat grains for improved human nutrition. Cereal Res. Commun. 2024, 53, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabri, M.; El-Soda, M. Genome-wide association mapping of macronutrient mineral accumulation in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Genome-wide association mapping of macronutrient mineral accumulation in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) grain. Plants 2024, 13, 3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.; Batley, J.; Snowdon, R.J. Accessing complex crop genomes with next-generation sequencing. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Ye, C.; Li, L.; Yin, H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, W.; Long, Y.; Hu, X.; Xiao, J. Genome-wide association study and genomic prediction for yield and grain quality traits of hybrid rice. Mol. Breed. 2022, 42, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Amand, P.S.; Bernardo, A.; Li, W.; He, F.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; Yuan, X.; Dong, L. High-resolution genome-wide association study identifies genomic regions and candidate genes for important agronomic traits in wheat. Mol. Plant. 2020, 13, 1311–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariatipour, N.; Heidari, B.; Tahmasebi, A.; Richards, C. Comparative genomic analysis of quantitative trait loci associated with micronutrient contents, grain quality, and agronomic traits in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 709817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.S.; Dreisigacker, S.; Pena, R.J.; Sukumaran, S.; Reynolds, M.P. Genetic characterization of the wheat association mapping initiative (WAMI) panel for dissection of complex traits in spring wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2015, 128, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alomari, D.Z.; Eggert, K.; von Wirén, N.; Pillen, K.; Röder, M.S. Genome-wide association study of calcium accumulation in grains of European wheat cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Barry, K.; Cao, F.; Zhou, M. Genome-wide association mapping for adult resistance to powdery mildew in common wheat. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 1241–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Sehgal, D.; Kumar, S.; Arif, M.A.R.; Vikram, P.; Sansaloni, C.P.; Fuentes-Dávila, G.; Ortiz, C. GWAS revealed a novel resistance locus on chromosome 4D for the quarantine disease karnal bunt in diverse wheat pre-breeding germplasm. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ren, J.; Yuan, X.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, D.; Li, C.; Zeng, Q.; Wu, J.; Han, D.; Jiang, L. Genome-wide association study reveals the genetic variation and candidate gene for grain calcium content in bread wheat. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 1379–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, M.; Baenziger, P.S.; Waters, B.M.; Poudel, R.; Belamkar, V.; Poland, J.; Morgounov, A. Genome-wide association study reveals novel genomic regions associated with 10 grain minerals in synthetic hexaploid wheat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, W.; Qin, M.; Yang, P.; Hou, J.; Huang, F.; Lei, Z.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J. Genome-wide association study reveals the genetic architecture for calcium accumulation in grains of hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathan, N.D.; Krishna, H.; Ellur, R.K.; Sehgal, D.; Govindan, V.; Ahlawat, A.K.; Krishnappa, G.; Jaiswal, J.P.; Singh, J.B.; Sv, S. Genome-wide association study identifies loci and candidate genes for grain micronutrients and quality traits in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. , Guo, H., Wu, C., Yu, H., Li, X., Chen, G., Tian, J.; Deng, Z. Identification of novel genomic regions associated with nine mineral elements in Chinese winter wheat grain. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 311. [Google Scholar]

- Sigalas, P.P.; Shewry, P.R.; Riche, A.; Wingen, L.; Feng, C.; Siluveru, A.; Chayut, N.; Burridge, A.; Uauy, C.; Castle, M.; Parmar, S. Improving wheat grain composition for human health by constructing a QTL atlas for essential minerals. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Dong, F.S.; Hu, F.H.; Liu, Y.W.; Chai, J.F.; Zhao, H.; Lv, M.Y.; Zhou, S. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the calmodulin-binding transcription activator (CAMTA) gene family in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Genet. 2020, 21, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peleg, Z.; Cakmak, I.; Ozturk, L.; Yazici, A.; Jun, Y.; Budak, H.; Korol, A.B.; Fahima, T.; Saranga, Y. Quantitative trait loci conferring grain mineral nutrient concentrations in durum wheat × wild emmer wheat RIL population. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 119, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, W.; Qin, M.; Yang, P.; Hou, J.; Huang, F.; Lei, Z.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J. Genome-wide association study reveals the genetic architecture for calcium accumulation in grains of hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, Y.; Taylor, J.; Rongala, J.; Oldach, K. A major locus for chloride accumulation on chromosome 5A in bread wheat. PloS One. 2014, 9, 98845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudah, A.M.; Elkelish, A.; Abu-Elsaoud, A.M.; Hassan, S.E.D.; Thabet, S.G. Genome-wide association study reveals the genetic basis controlling mineral accumulation in wheat grains under potassium deficiency. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2025, 72, 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.S. Characterization of quantitative trait loci for grain minerals in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Integr. Agric. 2013, 12, 1512–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigalas, P.P.; Shewry, P.R.; Riche, A.; Wingen, L.; Feng, C.; Siluveru, A.; Chayut, N.; Burridge, A.; Uauy, C.; Castle, M. , Parmar, S. Improving wheat grain composition for human health by constructing a QTL atlas for essential minerals. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Kong, F.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Che, N.; Li, S.; Wang, M.; Hao, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y. Genome-wide association study of grain micronutrient concentrations in bread wheat. J. Integr. Agri. 2024, 23, 1468–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, D.Z.; Alqudah, A.M.; Pillen, K.; von Wirén, N.; Röder, M.S. Toward identification of a putative candidate gene for nutrient mineral accumulation in wheat grains for human nutrition purposes. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 6305–6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukumaran, S.; Crossa, J.; Jarquín, D.; Lopes, M.; Reynolds, M.P. Genomic and pedigree prediction with genotype x environment interaction in spring wheat grown in South and Western Asia, North Africa, and Mexico. G3. 2016, 7, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wong, D.; Forrest, K.; Allen, A.; Chao, S.; Huang, B.E.; Maccaferri, M.; Salvi, S.; Milner, S.G.; Cattivelli, L. Characterization of polyploid wheat genomic diversity using a high-density 90,000 single nucleotide polymorphism array. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 12, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukumaran, S.; Lopes, M.; Dreisigacker, S.; Reynolds, M. Genetic analysis of multi-environmental spring wheat trials identifies genomic regions for locus-specific trade-offs for grain weight and grain number. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahirwar, R.N.; Mishra, V.K.; Chand, R.; Budhlakoti, N.; Mishra, D.C.; Kumar, S.; Singh, S.; Joshi, A.K. Genome-wide association mapping of spot blotch resistance in wheat association mapping initiative (WAMI) panel of spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). PLoS ONE. 2018, 13, e0208196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and environment for statistical computing; R foundation for statistical computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado, G.; Rodríguez, F.M.; Pacheco, A.; Burgueño, J.; Crossa, J.; Vargas, M.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Lopez-Cruz, M.A. META-R: A Software to analyze data from multi-environment plant breeding trials. Crop J. 2020, 8, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanRaden, P.M. Efficient Methods to compute genomic predictions. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 4414–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Z.; Xu, J.; Yin, D.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, X.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; et al. rMVP: A Memory-efficient, visualization-enhanced, and parallel-accelerated tool for genome-wide association study. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2021, 19, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marroni, F.; Pinosio, S.; Zaina, G.; Fogolari, F.; Felice, N.; Cattonaro, F.; Morgante, M. Nucleotide diversity and linkage disequilibrium in Populus nigra cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD4) Gene. G3. 2011, 7, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Gaurav, S.S.; Vasistha, N.K.; Joshi, A.K.; Mishra, V.K.; Chand, R.; Gupta, P.K. Genetics of spot blotch resistance in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using five models for GWAS. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1036064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccaferri, M. ; El-Feki,W.; Nazemi, G.; Salvi, S.; Canè, M.A.; Colalongo, M.C.; Stefanelli, S.; Tuberosa, R. Prioritizing quantitative trait loci for root system architecture in tetraploid wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Marker | Chr | Pos (cM)# | Pos (Mb)* |

Effect | Trait | Year | MAF | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wsnp_BE591290B_Ta_2_7 | 1A | 133.0 | 661.8 | -21.85 | Ca | 2022-23 | 0.19 | PNF |

| wsnp_BG274294B_Ta_2_3 | 1B | 77.0 | 543.0 | 36.33 | Mg | 2021-22 | 0.37 | PNF |

| IAAV565 | 1B | 122.0 | 652.4 | 18.64 | Ca | 2022-23 | 0.26 | PNF |

| Excalibur_c23906_303 | 1D | 115.0 | 436.9 | -34.07 | Ca | 2022-23 | 0.14 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ra_c193_406396 | 1D | 115.0 | 435.8 | -34.07 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.14 | PNF |

| BS00068139_51 | 2A | 62.0 | 30.4 | 34.28 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.07 | PNF |

| Kukri_c11327_977 | 2A | 101.0 | 361.3 | 19.62 10.69 |

Ca | 2021-2022, 2022-2023 |

0.13 |

[21] |

| wsnp_Ex_c61879_61748626 | 2A | 62.0 | 30.4 | 21.38 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.13 | PNF |

| RAC875_c39634_370 | 2A | 27.0 | 10.7 | -35.81 | Mg | 2021-2022 | 0.40 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ex_c11827_18986376 | 2A | 133.0 | 733.9 | -17.24 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.29 | PNF |

| RFL_Contig3509_229 | 2A | 128.0 | 723.8 | -32.11 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.09 | PNF |

| TA005606-1282 | 2B | 96.0 | 212.2 | -36.83 | Mg | 2021-2022 | 0.23 | PNF |

| Ra_c10607_524 | 2B | 114.0 | 692.9 | -26.26 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.11 | PNF |

| Kukri_c19751_873 | 2B | 108.0 | 594.1 | 20.46 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.47 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ex_rep_c67543_66165372 | 2B | 108.0 | 593.6 | 20.25 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.48 | PNF |

| BS00022800_51 | 2B | 108.0 | 595.1 | 19.23 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.48 | PNF |

| Kukri_c25815_263 | 2B | 108.0 | 594.8 | 18.76 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.49 | PNF |

| Excalibur_c7963_1722 | 2B | 69.0 | 31.0 | -19.95 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.46 | PNF |

| GENE-1421_802 | 2B | 69.0 | 46.0 | -19.80 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.45 | PNF |

| Tdurum_contig12879_1273 | 2B | 115.0 | 712.6 | -21.51 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.20 | PNF |

| Ku_c51309_212 | 2B | 115.0 | 714.7 | -22.06 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.19 | PNF |

| Kukri_c29640_212 | 2B | 69.0 | 47.1 | -20.51 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.47 | PNF |

| Gene_1421_706 | 2B | 69.0 | 46.0 | 19.73 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.45 | PNF |

| Excalibur_c2050_748 | 2B | 69.0 | 46.1 | -20.77 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.45 | PNF |

| GENE-1421_124 | 2B | 69.0 | 47.1 | -21.02 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.44 | PNF |

| RAC875_c66820_684 | 2D | 91.0 | 622.9 | 20.76 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.23 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ku_c2249_4335279 | 3A | 188.0 | 611.2 | 25.67 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| D_contig35269_394 | 3A | 33.0 | 16.1 | -34.31 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.13 | PNF |

| RAC875_rep_c111781_179 | 3B | 5.0 | 13.0 | -22.87 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.20 | PNF |

| Kukri_c17082_519 | 3B | 5.0 | 24.8 | -23.06 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.18 | PNF |

| RAC875_c13385_1268 | 3B | 5.0 | 24.8 | -23.06 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.18 | PNF |

| BS00062806_51 | 3D | 143.0 | 604.6 | 26.18 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| BS00070060_51 | 3D | 143.0 | 614.6 | 26.18 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| D_GBF1XID02HLMWB_65 | 3D | 143.0 | 604.4 | 26.18 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| Excalibur_c51976_119 | 3D | 143.0 | 611.2 | 26.18 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| TA006354-0937 | 3D | 143.0 | 611.2 | 26.18 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| BobWhite_c5246_196 | 3D | 143.0 | 746.6 | 25.67 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| BS00070059_51 | 3D | 143.0 | 614.6 | 25.67 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| BS00105800_51 | 3D | 143.0 | 611.5 | 25.67 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| D_GDEEGVY01CO81T_81 | 3D | 143.0 | 604.3 | 25.67 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| Excalibur_c17654_1090 | 3D | 143.0 | 611.2 | 25.67 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| Excalibur_c6906_804 | 3D | 143.0 | 612.8 | 25.67 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ex_c12963_20529964 | 3D | 143.0 | 612.9 | 25.67 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ku_c7264_12545135 | 3D | 143.0 | 612.9 | 25.67 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.10 | PNF |

| Excalibur_c12032_1101 | 4A | 26.0 | 10.6 | 39.71 | Mg | 2021-2022 | 0.36 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ex_c7280_12498193 | 4A | 144.0 | 725.6 | 48.11 | Mg | 2021-2022 | 0.12 | PNF |

| Ra_c7973_1185 | 4A | 43.0 | 46.1 | 46.51 | Mg | 2021-2022 | 0.14 | PNF |

| Tdurum_contig59603_74 | 4A | 26.0 | 99.2 | 37.64 | Mg | 2021-2022 | 0.39 | PNF |

| Tdurum_contig59603_94 | 4A | 26.0 | 99.2 | 37.64 | Mg | 2021-2022 | 0.39 | PNF |

| Tdurum_contig31139_143 | 4B | 35.0 | 13.9 | -22.53 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.22 | PNF |

| Tdurum_contig31139_79 | 4B | 35.0 | 13.9 | -22.53 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.22 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ku_c9140_15390166 | 4D | 79.0 | 50.1 | -35.87 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.07 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ex_c2718_5038582 | 5A | 43.0 | 46.7 | 16.98 18.48 |

Ca | 2021-2022, 2022-2023 |

0.43 0.23 |

[21] |

| RAC875_c9984_1003 | 5A | 89.0 | 585.4 |

16.55 11.10 |

Ca | 2021-2022, 2022-2023 |

0.31 0.23 |

[21] |

| Excalibur_c52167_355 | 5A | 76.0 | 549.5 | -28.63 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.12 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ra_c17216_26044790 | 5A | 76.0 | 549.5 | -22.78 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.13 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ku_c5308_9450093 | 5B | 21.0 | 16.4 | -20.67 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.39 | PNF |

| GENE-3277_145 | 5B | 20.0 | 16.9 | -20.05 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.40 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ex_c12927_20480163 | 5B | 20.0 | 16.4 | -20.05 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.40 | PNF |

| Tdurum_contig28802_213 | 6A | 125.0 | 597.8 | 17.94 18.12 | Mg | 2021-2022, 2022-23 | 0.19 0.38 | [22] |

| BS00077044_51 | 6A | 140.0 | 614.6 | -33.63 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.09 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ex_c34597_42879693 | 6A | 125.0 | 597.8 | 19.2,1 21.02 | Mg | 2021-2022, 2022-23 | 0.29 0.37 | [22] |

| RFL_Contig6053_3082 | 6A | 126.0 | 597.7 | 17.76 24.84 |

Mg | 2021-22, 2022-2023 |

0.24 0.26 |

[22] |

| wsnp_Ex_c34597_42879718 | 6B | 93.0 | 597.8 | Ca, Mg | 2021-2022, 2022-23 | PNF | ||

| CAP11_c1473_320 | 7A | 82.0 | 52.9 | -19.47 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.20 | PNF |

| BS00078460_51 | 7A | 82.0 | 52.9 | -18.50 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.22 | PNF |

| Ex_c9615_1202 | 7A | 82.0 | 52.9 | -18.50 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.22 | PNF |

| Ex_c9615_574 | 7A | 82.0 | 49.8 | -18.50 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.22 | PNF |

| RAC875_c52560_123 | 7A | 76.0 | 46.7 | 22.30 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.11 | PNF |

| BS00022751_51 | 7A | 126.0 | 159.5 | -41.85 | Mg | 2021-2022 | 0.34 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ex_c25025_34285478 | 7A | 126.0 | 159.4 | -41.85 | Mg | 2021-2022 | 0.34 | PNF |

| Tdurum_contig45437_1667 | 7A | 74.0 | 42.1 | 45.24 | Mg | 2021-2022 | 0.12 | PNF |

| Kukri_c31824_636 | 7A | 183.0 | 696.9 | 24.44 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.32 | PNF |

| Tdurum_contig31699_276 | 7A | 183.0 | 696.9 | 24.44 | Mg | 2022-2023 | 0.32 | PNF |

| RAC875_c10555_178 | 7B | 8.0 | 35.4 | 20.69 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.29 | PNF |

| IAAV1902 | 7B | 8.0 | 36.8 | 20.44 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.29 | PNF |

| wsnp_JD_c1285_1848292 | 7B | 10.0 | 37.0 | 19.93 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.30 | PNF |

| BobWhite_c47269_128 | 7B | 10.0 | 37.0 | 19.65 | Ca | 2021-2022 | 0.30 | PNF |

| Tdurum_contig97814_355 | 7B | 95.0 | 641.1 | 18.45 | Ca | 2022-2023 | 0.35 | PNF |

| wsnp_Ex_c10430_17064001 | 7D | 118.0 | 112.4 | -37.60 | Mg | 2021-2022 | 0.48 | PNF |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).