Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

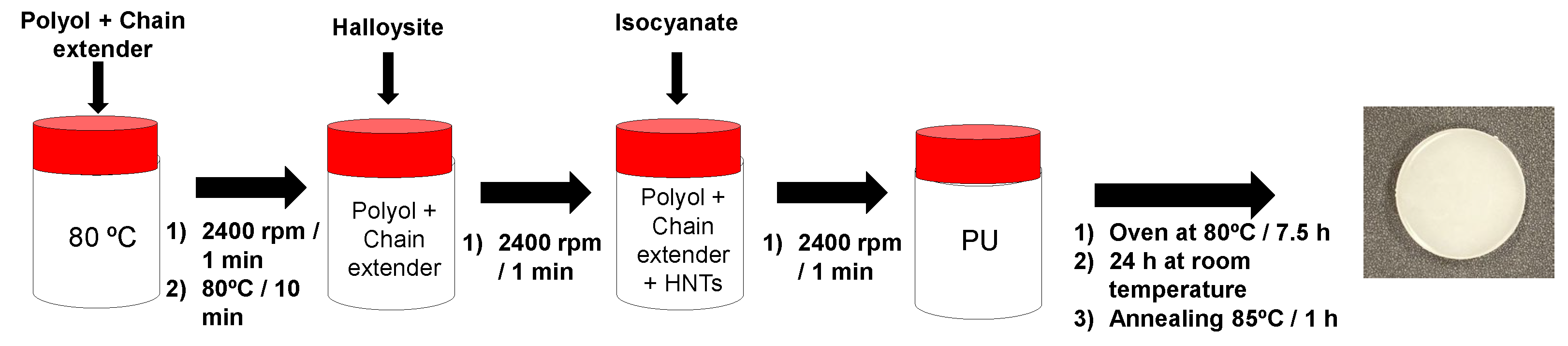

2.2.1 Synthesis of the polyurethanes

2.2.2 Experimental Techniques

3. Results and Discussion

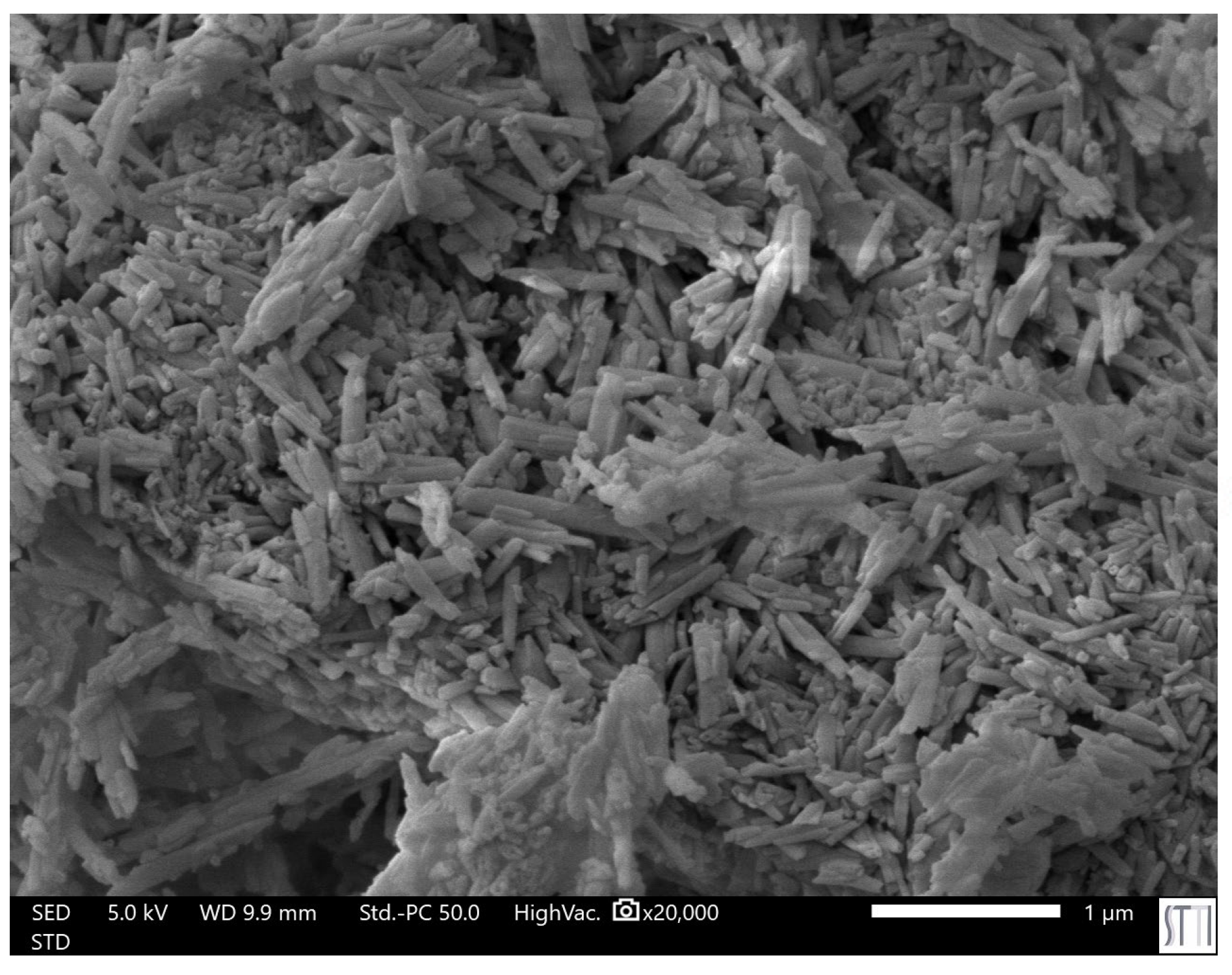

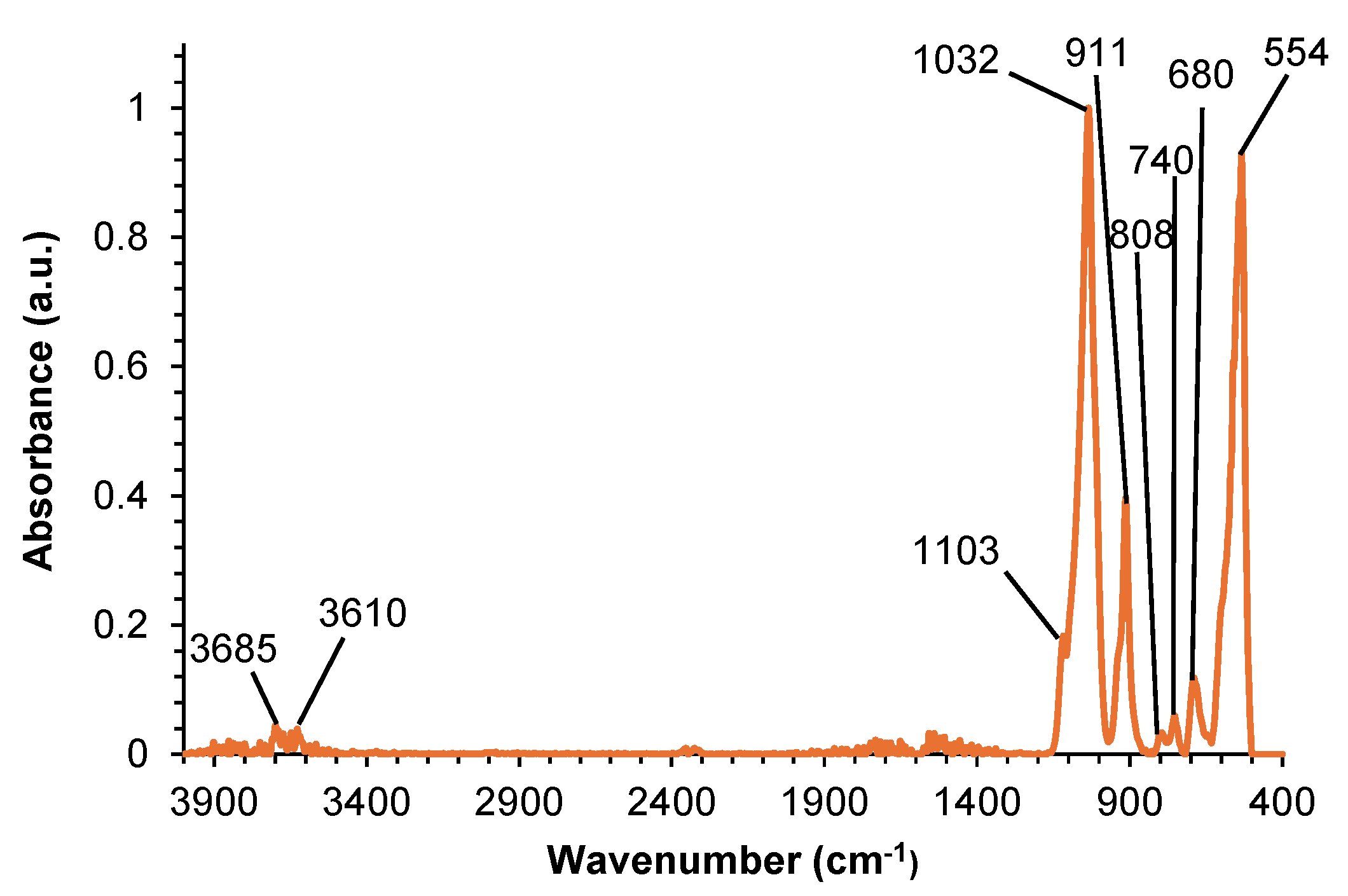

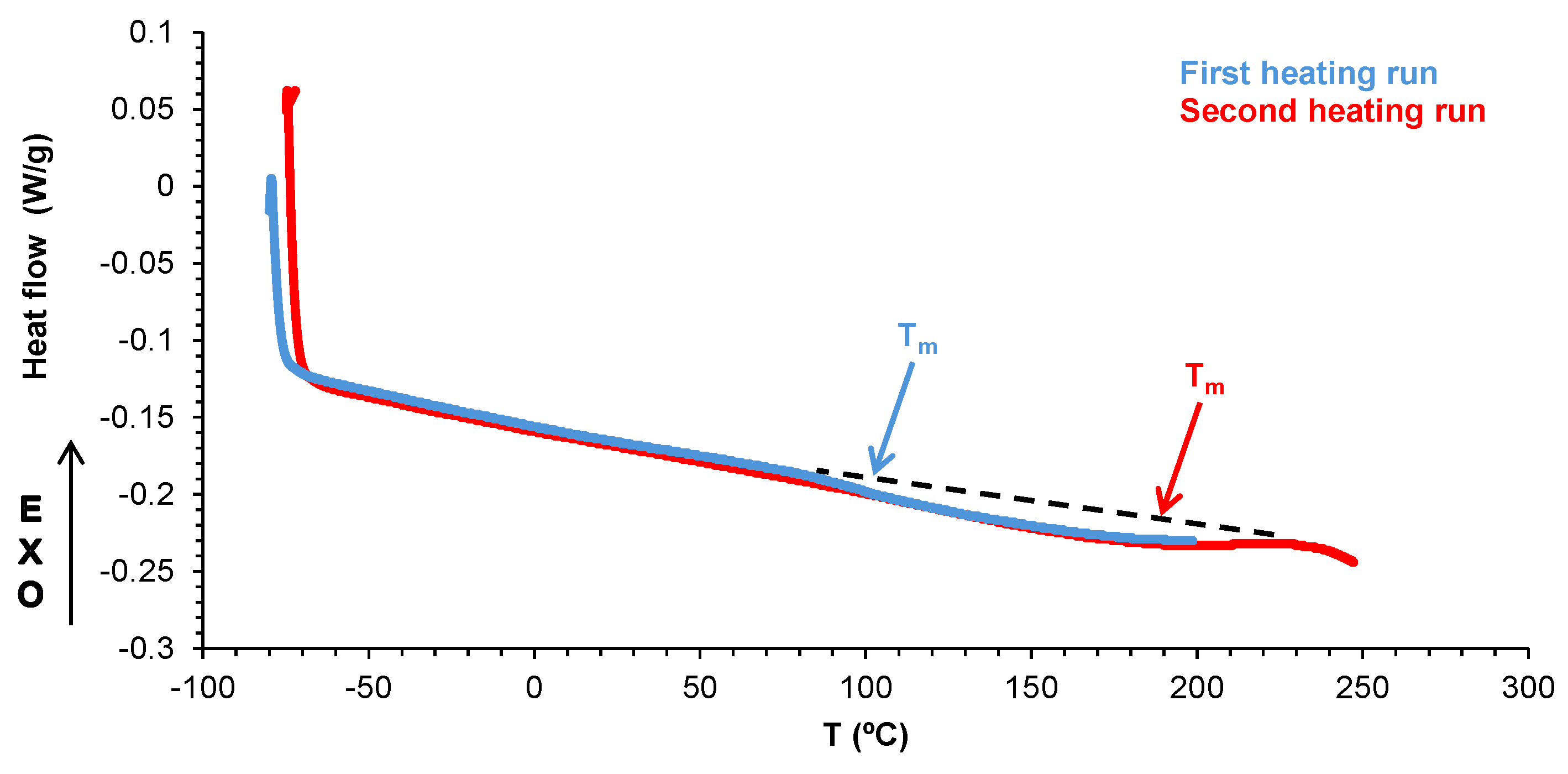

3.1. Characterization of halloysite

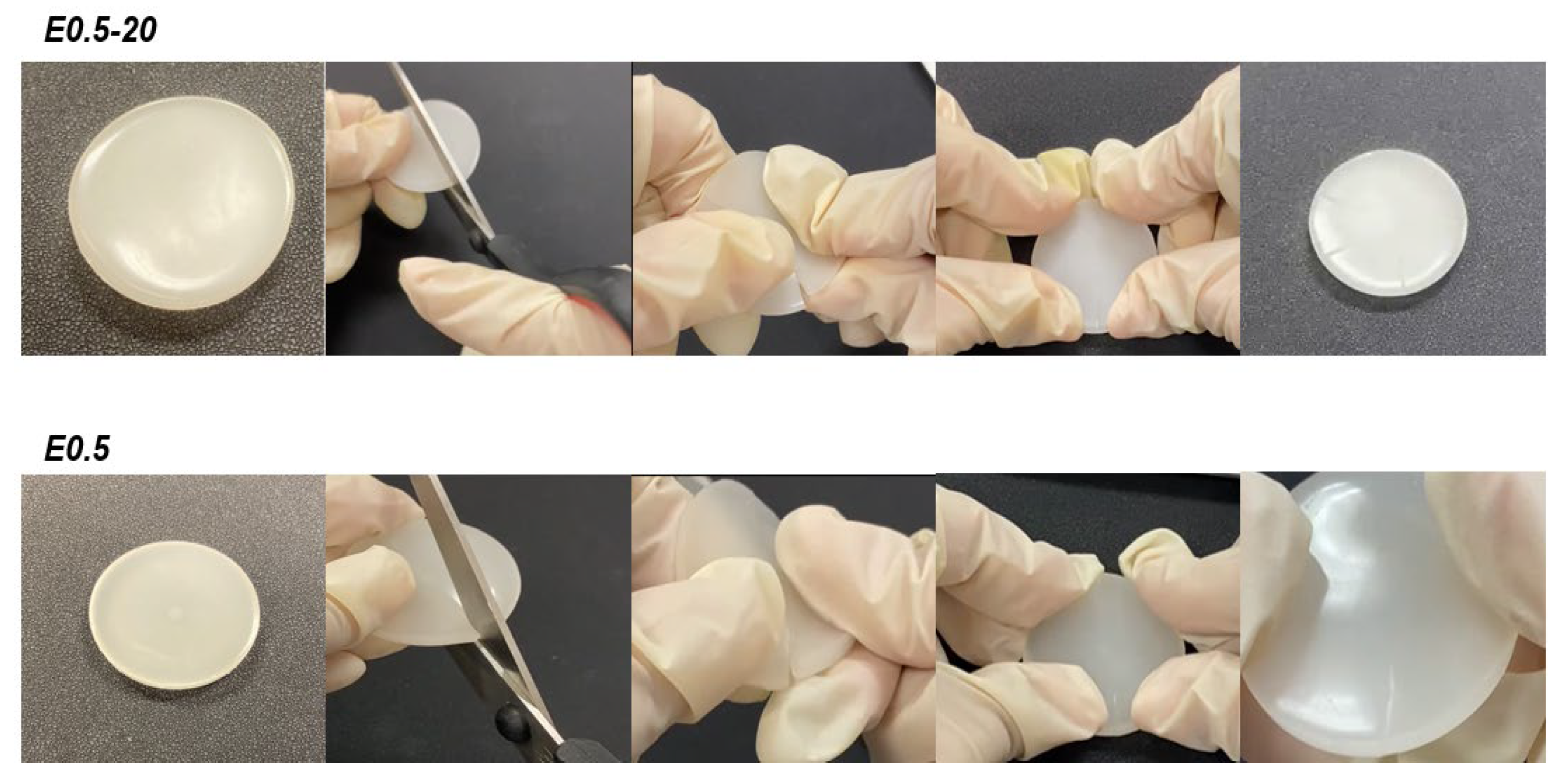

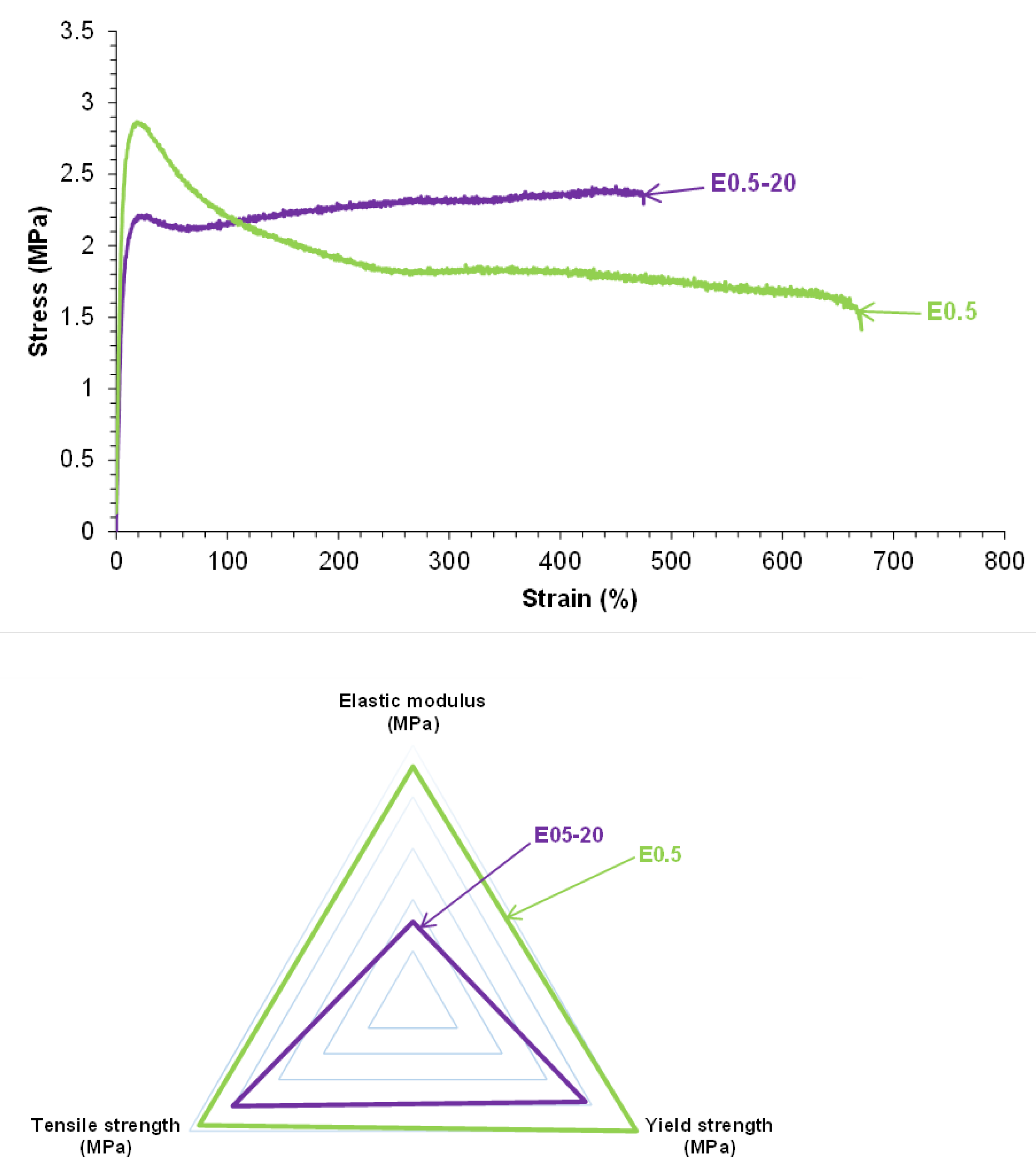

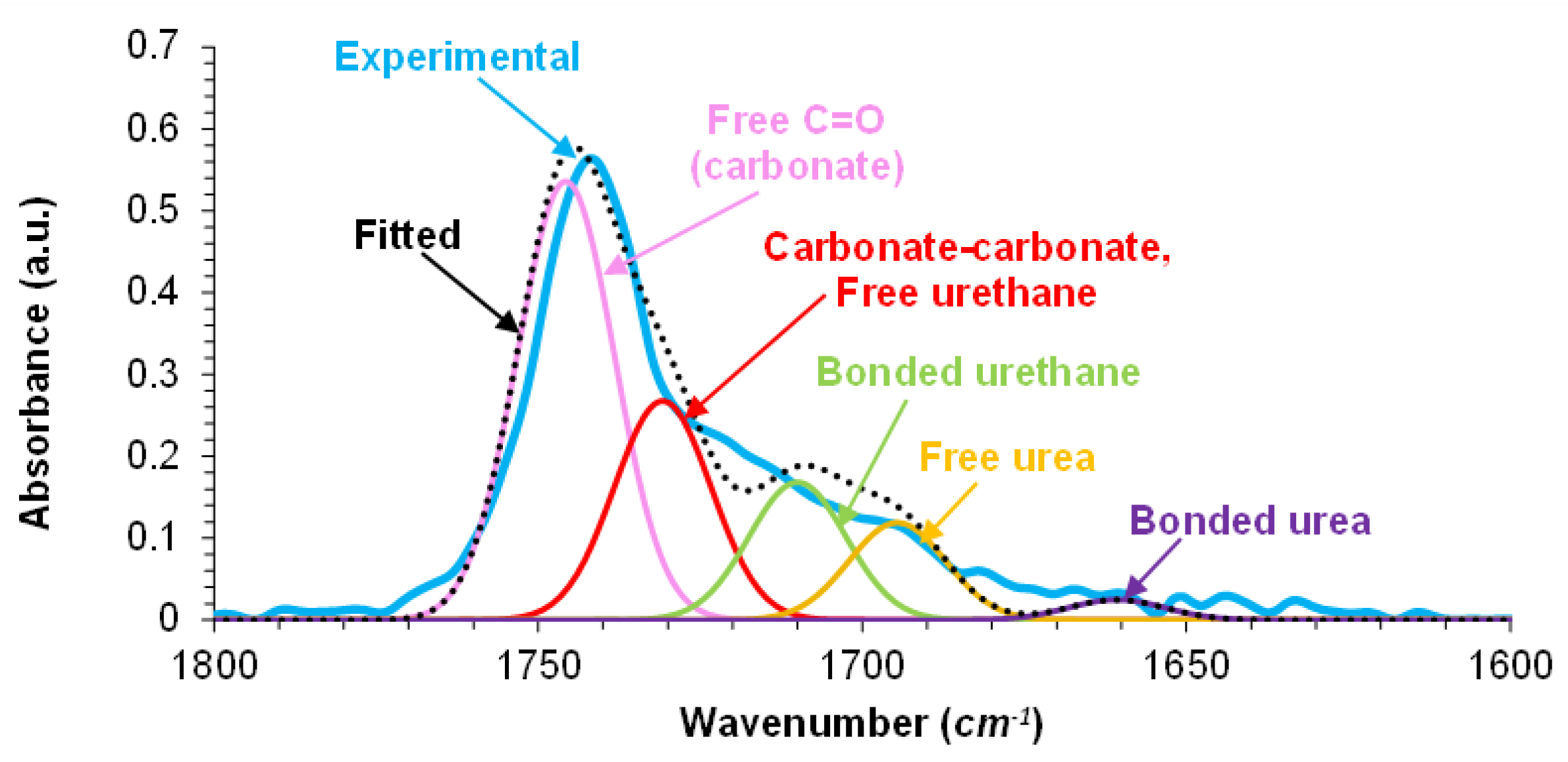

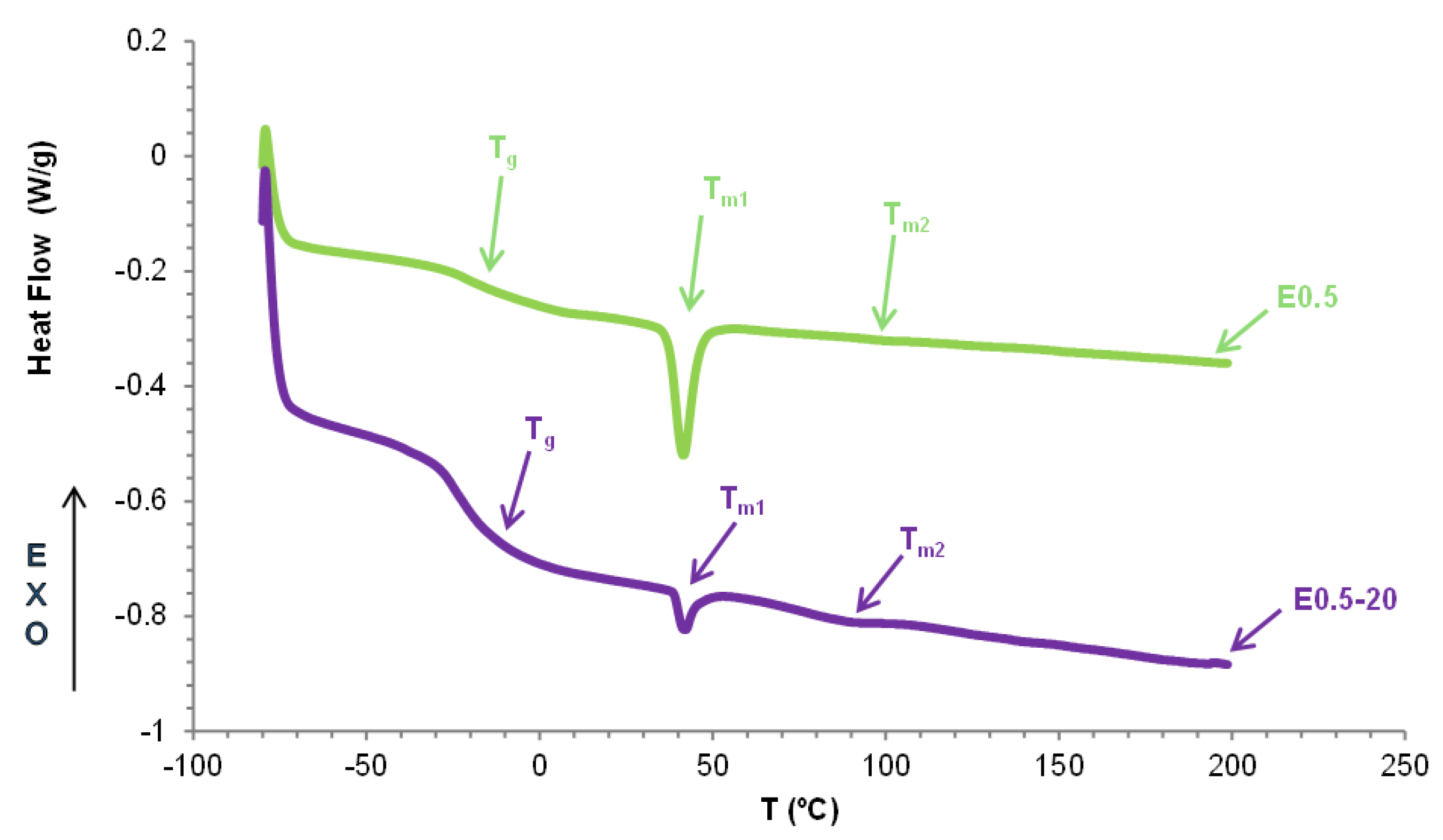

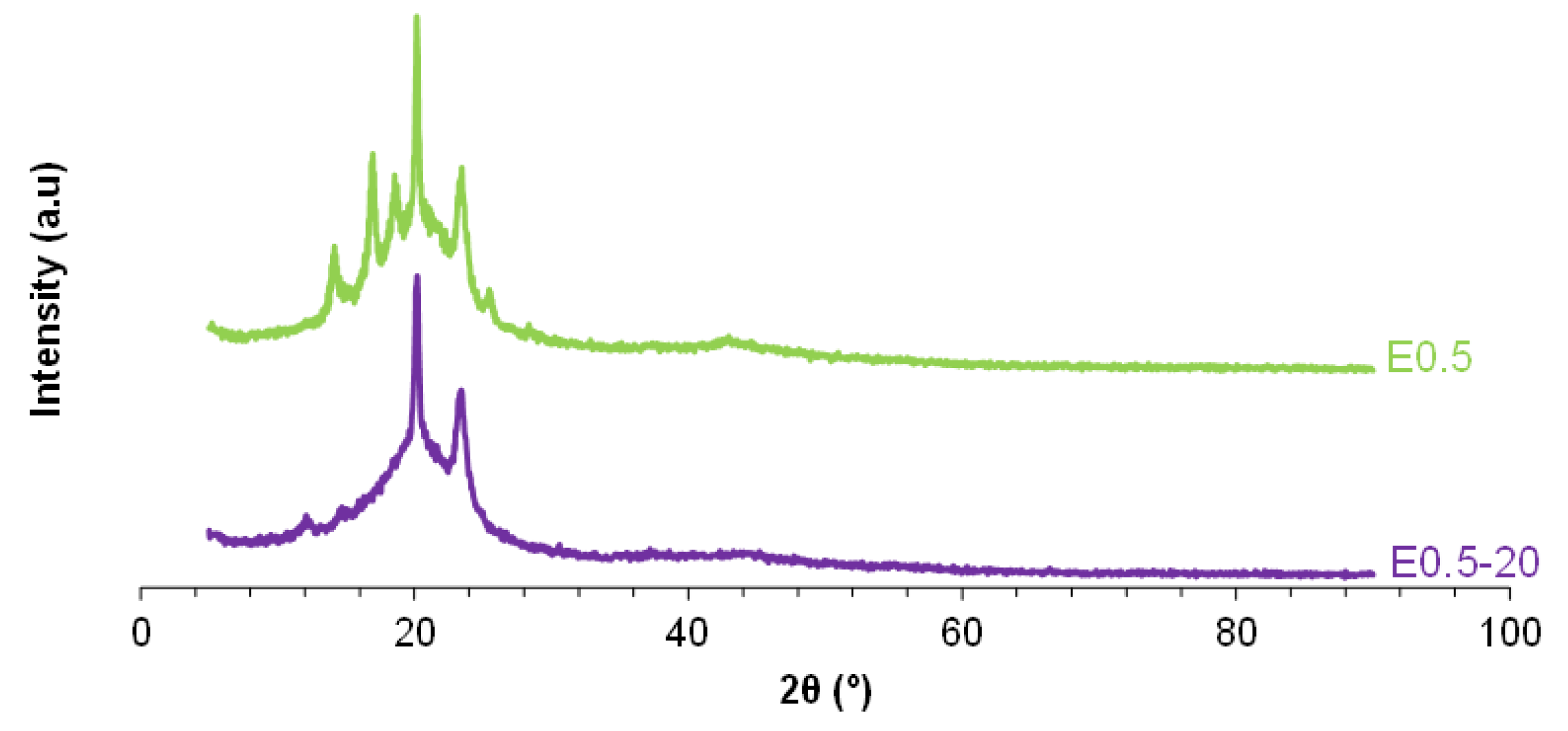

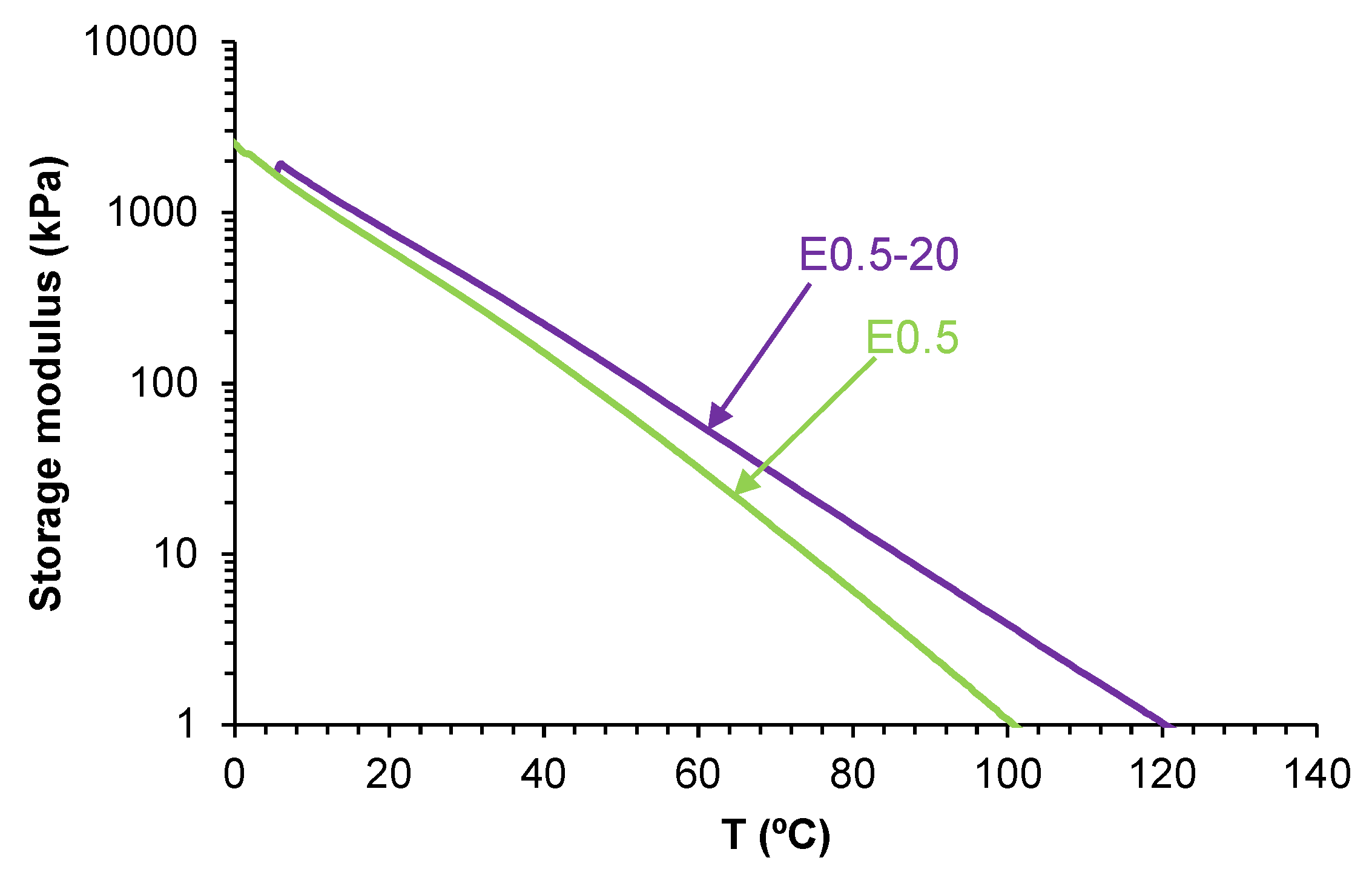

3.2. Polyurethanes made with 0.5 wt.% as-received and thermally treated halloysite (E0.5-20 and E0.5)

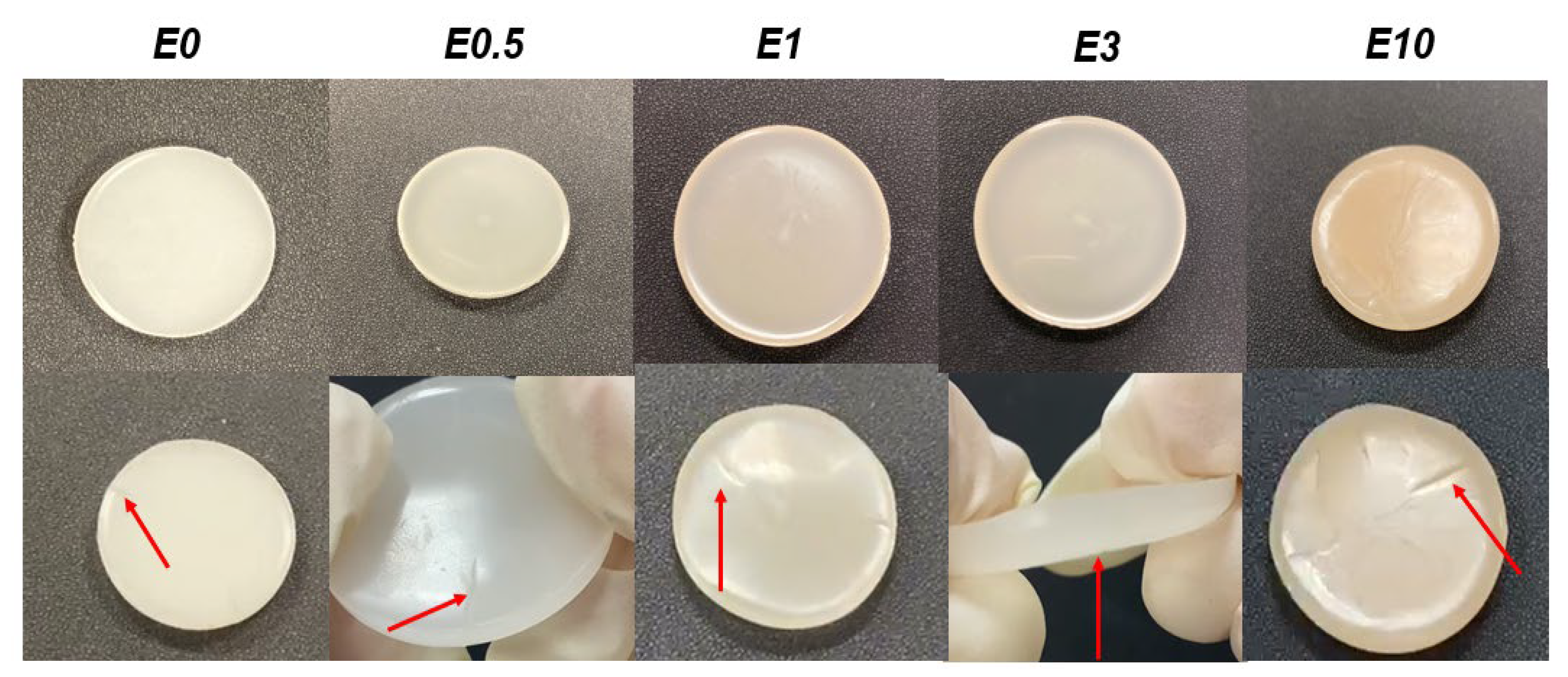

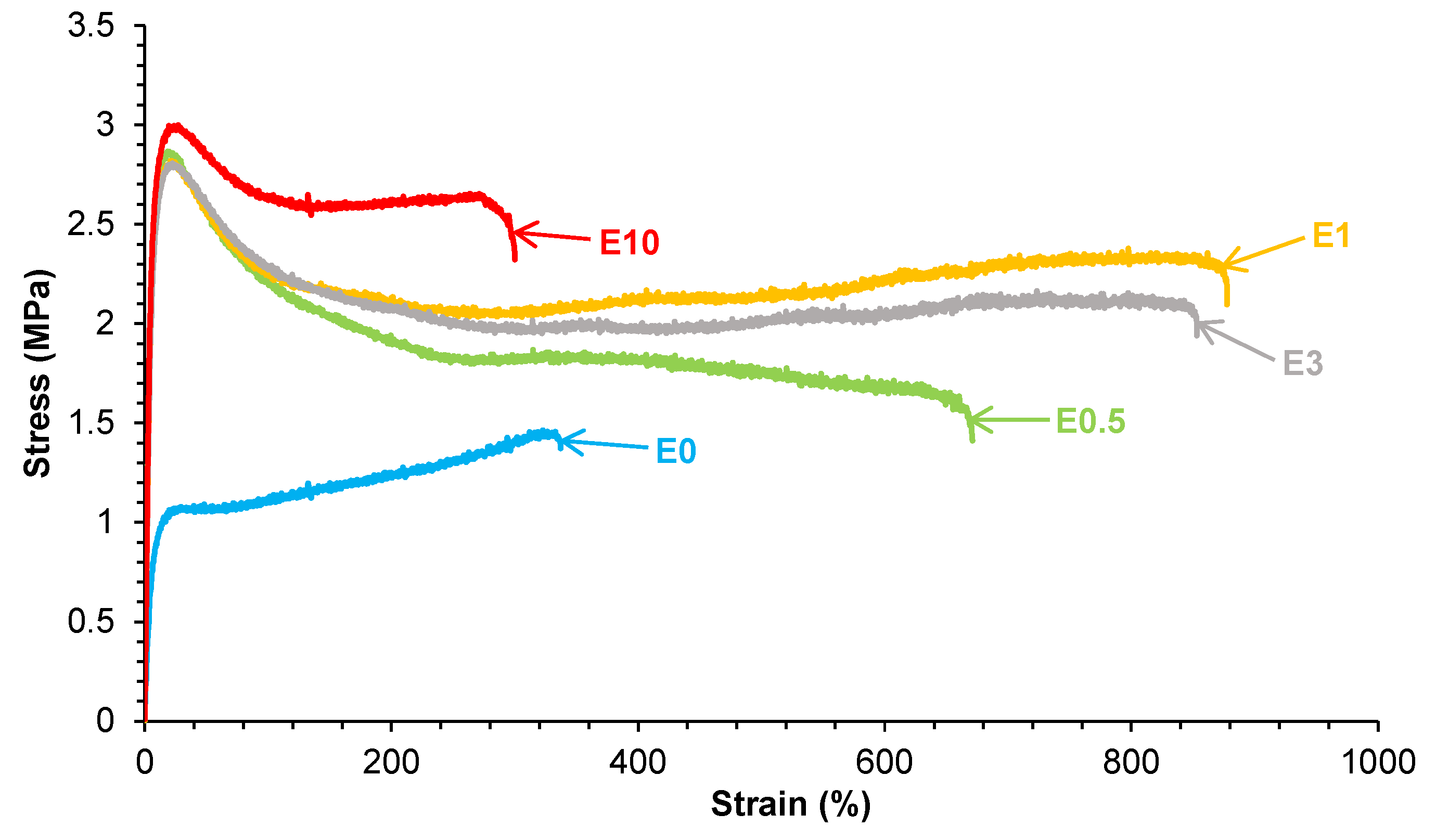

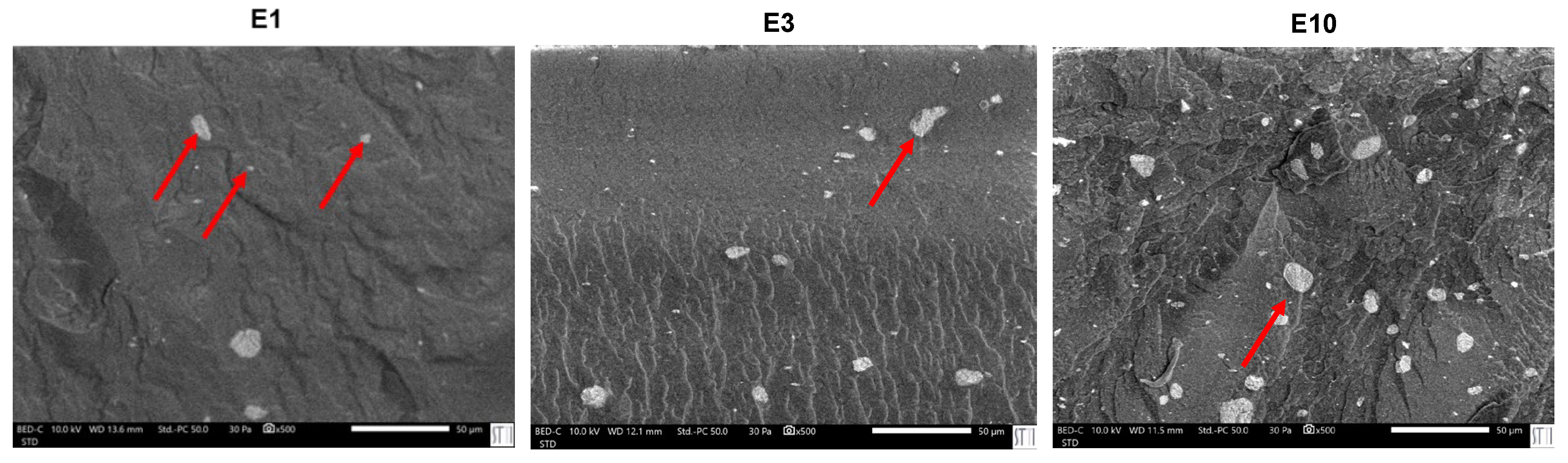

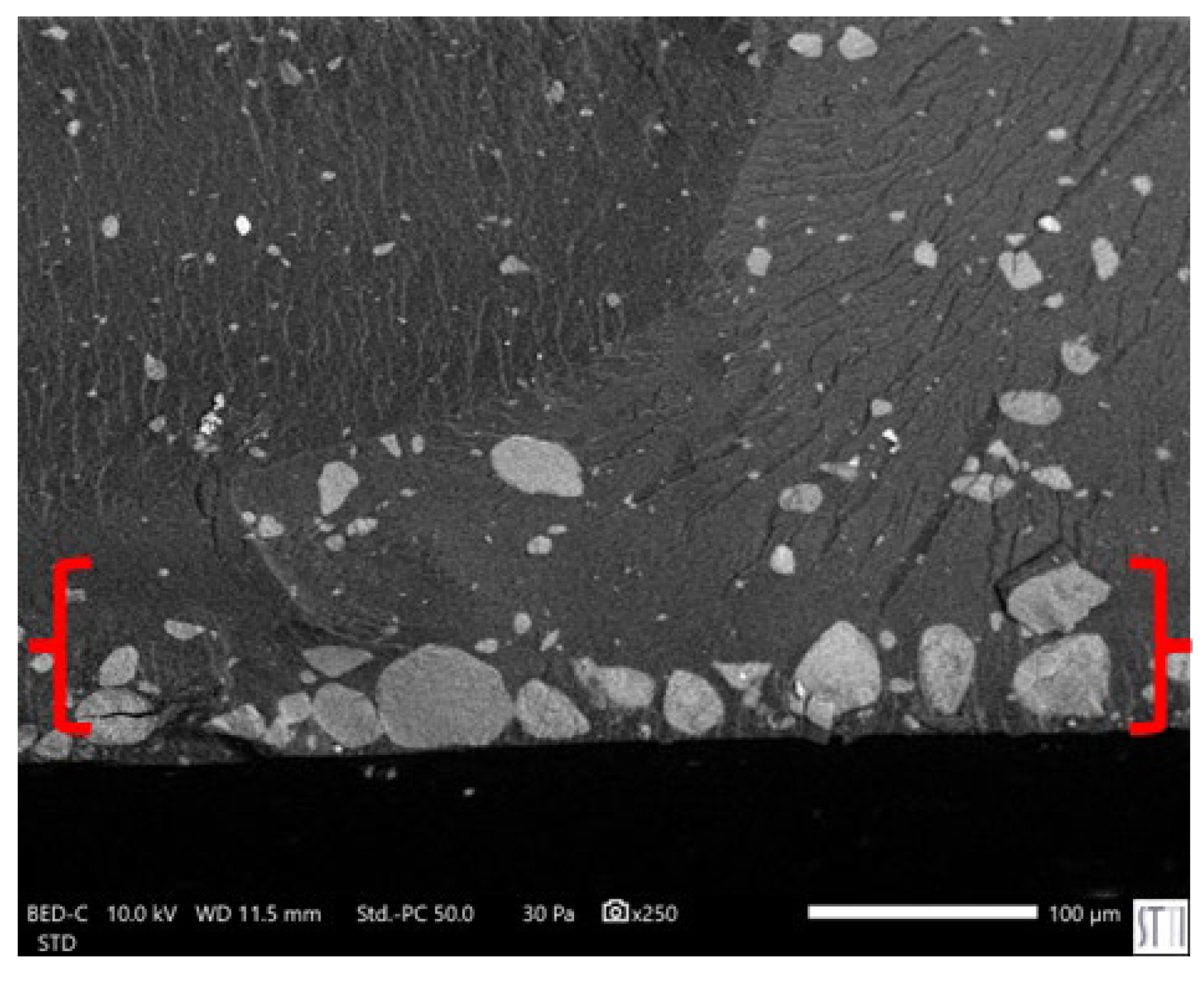

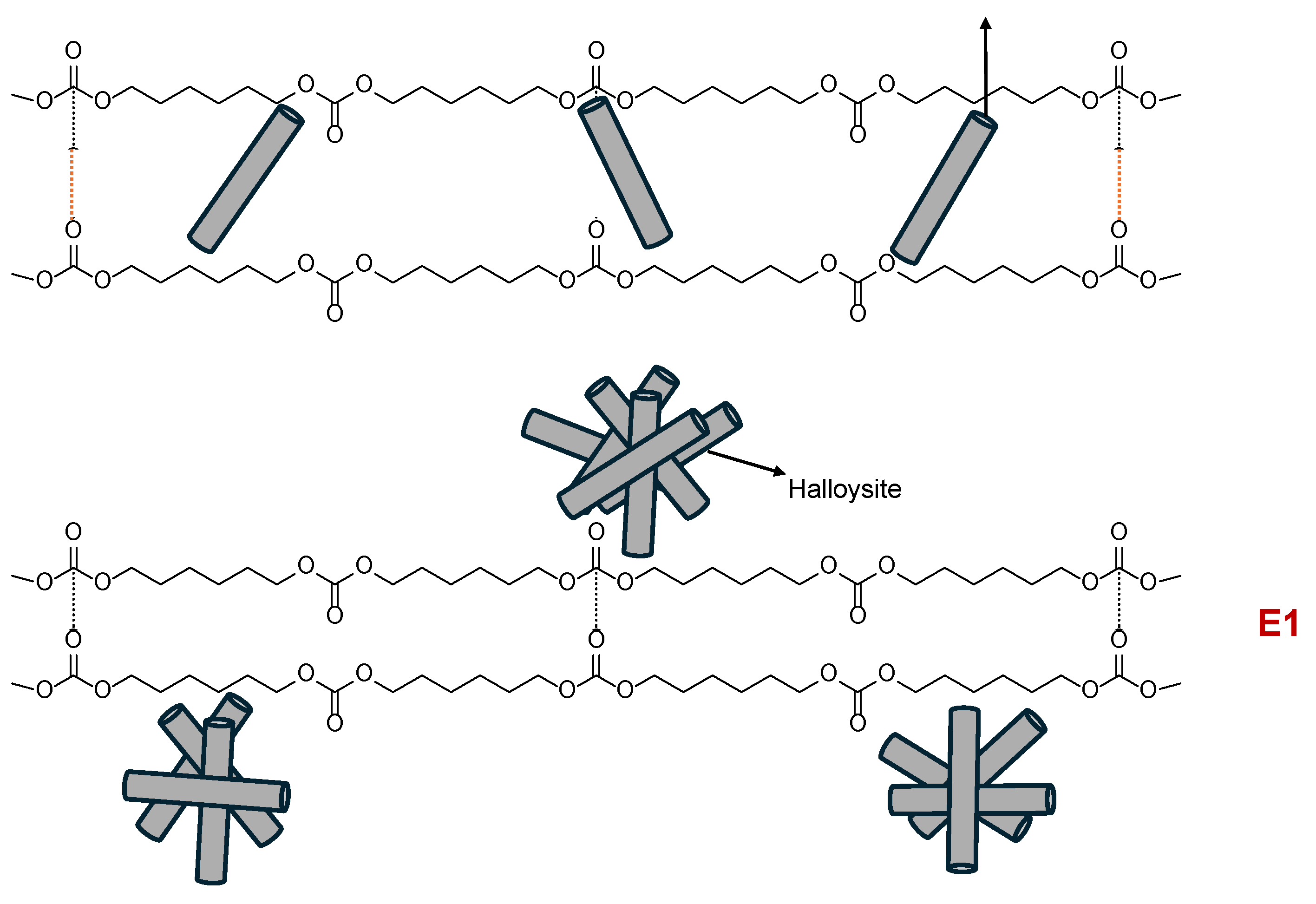

3.3. Characterization of polyurethanes without and with different amounts of halloysite

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paez-Amieva, Y.; Mateo-Oliveras, N.; Martín-Martínez, J.M. Polyurethanes synthesized with blends of polyester and polycarbonate polyols—New evidence supporting the dynamic non-covalent exchange mechanism of intrinsic self-healing at 20 °C. Polymers 2024, 16(20), 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, M.; Kim, Y.-O.; Ahn, S.; Lee, S.-K.; Lee, J.-S.; Park, M.; Chung, J.W.; Jung, Y. Robust and stretchable self-healing polyurethane based on polycarbonate diol with different soft-segment molecular weight for flexible devices. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 118, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, C. Polyurethane elastomers. Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. https://books.google.es/books?id=7WjuCAAAQBAJ.

- Lee, N.C. Practical Guide to Blow Moulding. Rapra Technology Ltd.: Shrewsbury, UK, 2006.

- Gama, N.V.; Ferreira, A.; Barros-Timmons, A. Polyurethane foams: Past, present, and future. Materials 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Mi, F.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, S. Bio-based polycarbonates: Progress and prospects. RSC Sustain. 2023, 1, 2162–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryszkowska, J.; Wasniewski, B. Quantitative description of the morphology of polyurethane nanocomposites for medical applications. WIT Trans. Eng. Sci. 2011, 72, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M. , Guan, F., Zhang, M., Nie, J., Bao, L. Castor oil-based self-healing polyurethane based on multiple hydrogen bonding and disulfide bonds. Journal of Polymer Research 2025, 32(4), 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willocq, B.; Odent, J.; Dubois, P.; Raquez, J.-M. Advances in intrinsic self-healing polyurethanes and related composites. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 13766–13782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, G.; Wang, F.; Wang, P. Synthesis of polycarbonate diol catalyzed by metal–organic framework based on Zn and terephthalic acid. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 634–638, 608–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, F.; Zamani, Y.; Bear, K.; Kheradvar, A. Material characterization and biocompatibility of polycarbonate-based polyurethane for biomedical implant applications. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 8839–8850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, N.; Song, T.; Ji, Z.; Jiang, D.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z. Recent advancements in self-healing materials: Mechanicals, performances and features. React. Funct. Polym. 2021, 168, 105041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez-Amieva, Y.; Mateo-Oliveras, N.; Martín-Martínez, J.M. Influence of the molecular weight of the polycarbonate polyol on the intrinsic self-healing at 20 °C of polyurethanes. Polymers 2024, 16, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.; Kim, Y.-O.; Ahn, S.; Lee, S.-K.; Lee, J.-S.; Park, M.; Chung, J.W.; Jung, Y. Robust and stretchable self-healing polyurethane based on polycarbonate diol with different soft-segment molecular weight for flexible devices. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 118, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, R.; Miller, R.E.; Petel, O.E. Microstructural evidence of the toughening mechanisms of polyurethane reinforced with halloysite nanotubes under high strain-rate tensile loading. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez-Amieva, Y.; Mateo-Oliveras, N.; Martín-Martínez, J.M. Influence of the molecular weight of the polycarbonate polyol on the intrinsic self-healing at 20 °C of polyurethanes. Polymers 2024, 16, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paez-Amieva, Y.; Mateo-Oliveras, N.; Martín-Martínez, J.M. M. Polyurethanes made with blends of polycarbonates with different molecular weights showing adequate mechanical and adhesion properties and fast self-healing at room temperature. Materials 2024, 17, 5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokharel, P.; Xiao, D.; Erogbogbo, F.; Keles, O.; Lee, D.S. A hierarchical approach for creating electrically conductive network structure in polyurethane nanocomposites using a hybrid of graphene nanoplatelets, carbon black and multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 161, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia-Hu, G.; Yu-Cun, L.; Tao, C.; Su-Ming, J.; Hui, M.; Ning, Q.; Hua, Z.; Tao, Y.; Wei-Ming, H. Synthesis and properties of a nano-silica modified environmentally friendly polyurethane adhesive. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 44990–44997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounici, A.; Martín-Martínez, J.M. M. Addition of small amounts of graphene oxide in the polyol during the synthesis of waterborne polyurethane urea adhesives for improving their adhesion properties. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2021, 104, 102725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia-Hu, G.; Yu-Cun, L.; Tao, C.; Su-Ming, J.; Hui, M.; Ning, Q.; Hua, Z.; Tao, Y.; Wei-Ming, H. Synthesis and properties of a nano-silica modified environmentally friendly polyurethane adhesive. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 44990–44997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.I.; Ha, Y.H.; Jeon, H.; Kim, S.H. Preparation and properties of polyurethane composite foams with silica-based fillers. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Członka, S.; Strąkowska, A.; Strzelec, K.; Kairytė, A.; Vaitkus, S. Composites of rigid polyurethane foams and silica powder filler enhanced with ionic liquid. Polym. Test. 2019, 75, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, M.P.; Stanojević-Nikolić, S.; Pavlović, V.B.; Srdić, V.V. The effect of silica nanoparticles obtained from different sources on mechanical properties of polyurethane nanocomposites. Eng. Today 2024, 3, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Yuhana, N.Y.; Fariz, S.; Otoh, M. The mechanical and thermal properties of polyurethanes/precipitated calcium carbonate composites. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 943, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustiyah, E.; Nandang, A.; Amrullah, M.; Priadi, D.; Chalid, M. Effect of calcium carbonate content on the mechanical and thermal properties of chitosan-coated poly(urethane) foams. Indones. J. Chem. 2022, 22, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasirzadeh, R.; Sabet, A.R. Influence of nanoclay reinforced polyurethane foam toward composite sandwich structure behavior under high velocity impact. J. Cell. Plast. 2014, 52, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.I.; Ha, Y.H.; Jeon, H.; Kim, S.H. Preparation and properties of polyurethane composite foams with silica-based fillers. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12(15), 7418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Verma, S.K.; Mehta, R. Tailoring the properties of polyurethane composites: A comprehensive review. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2025, 13, 2004–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Roca, E. Halloysite nanotubes/hydroxyapatite nanocomposites as hard tissue substitutes: Effect on the morphology, thermomechanical behavior and biological development of aliphatic polyesters and polymethacrylates; Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez Barrios, M. Surface modification and interfacial interactions in halloysite nanotube-based polymer nanocomposites; Ph.D. Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, P.; Tan, D.; Annabi-Bergaya, F.; Yan, W.; Fan, M.; Liu, D.; He, H. Changes in structure, morphology, porosity, and surface activity of mesoporous halloysite nanotubes under heating. Clays Clay Miner. 2012, 60, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Zhang, J.; Ye, L.; Wu, J. Toughening epoxies with halloysite nanotubes. Polymer 2008, 49, 5119–5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lvov, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Fakhrullin, R. Halloysite clay nanotubes for loading and sustained release of functional compounds. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 1227–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrówka, M.; Ślusarczyk, M.; Machoczek, T.; Pawlyta, M. Influence of the halloysite nanotube (HNT) addition on selected mechanical and biological properties of thermoplastic polyurethane. Materials 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.; Beatrice, C. Polymer nanocomposites with different types of nanofiller. In Polymer Nanocomposites: Recent Advances and Challenges; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; p. 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Ouyang, C.; Yuan, Y.; Gao, Q. Synthesis and properties of a millable polyurethane elastomer with low halloysite nanotube content. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 77106–77114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sheng, D.; Liu, X.; Lin, C.; Ji, F.; Dong, L.; Xu, S.; Yang, Y. Synthesis and properties of crosslinking halloysite nanotubes/polyurethane based solid–solid phase change materials. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 174, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, R.; Miller, R.E.; Petel, O.E. Microstructural evidence of the toughening mechanisms of polyurethane reinforced with halloysite nanotubes under high strain-rate tensile loading. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Ge, H.; Wang, T.; Huang, M.; Ying, P.; Zhang, P.; Wu, J.; Ren, S.; Levchenko, V. A self-healing and recyclable polyurethane/halloysite nanocomposite based on thermoreversible Diels-Alder reaction. Polymer 2020, 206, 122894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, W.T.; Dong, Y.; Pramanik, A. mechanical and shape memory properties of additively manufactured polyurethane (PU)/halloysite nanotube (HNT) nanocomposites. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Ying, P.; Huang, M.; Zhang, P.; Yang, T.; Liu, G.; Wang, T.; Wu, J.; Levchenko, V.A. Synthesis of robust and self-healing polyurethane/halloysite coating via in-situ polymerization. J. Polymer Res. 2021, 28, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Han, E.-H. A self-healing sustainable halloysite nanocomposite polyurethane coating with ultrastrong mechanical properties based on reversible intermolecular interactions. Appl. Surface Sci. 2024, 667, 160399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Ge, H.; Lin, C.; Ying, P.; Huang, M.; Zhang, P.; Yang, T.; Liu, G.; Wu, J.; Levchenko, V.A. Thermally self-healing and recyclable polyurethane by incorporating halloysite nanotubes via in situ polymerization. Applied Composite Materials 2022, 29, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D638-14; Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics. ASMT: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- Yuan, P.; Tan, D.; Annabi-Bergaya, F.; Yan, W.; Fan, M.; Liu, D.; He, H. Changes in structure, morphology, porosity, and surface activity of mesoporous halloysite nanotubes under heating. Clays Clay Miner. 2012, 60, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliaie, H.; Haddadi-Asl, V.; Masoud Mirhosseini, M.; Sahebi Jouibari, I.; Mohebi, S.; Shams, A. Role of sequence of feeding on the properties of polyurethane nanocomposite containing halloysite nanotubes. Des Monomers Polym. 2019, 22(1), 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Wavenumber (cm⁻¹) | Percentage (%) | Assignment | |

| E0.5-20 | E0.5 | ||

| 1745 | 41 | 48 | Free C=O (carbonate) |

| 1730 | 33 | 24 | Carbonate-carbonate, Free urethane |

| 1710 | 14 | 15 | Bonded urethane |

| 1695 | 10 | 11 | Free urea |

| 1660 | 2 | 2 | Bonded urea |

| Wavenumber (cm⁻¹) | Percentage (%) | Assignment | ||||

| E0 | E0.5 | E1 | E3 | E10 | ||

| 1745 | 49 | 48 | 42 | 39 | 39 | Free C=O (carbonate) |

| 1730 | 25 | 24 | 31 | 33 | 33 | Carbonate-carbonate, Free urethane |

| 1710 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 15 | Bonded urethane |

| 1695 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 11 | Free urea |

| 1660 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | Bonded urea |

|

Element |

Percentage (at. %) | ||

| E0 | E0.5 | E1 | |

| C | 84 | 81 | 84 |

| O | 16 | 18.5 | 15 |

| Si | 0.5 | 1 | |

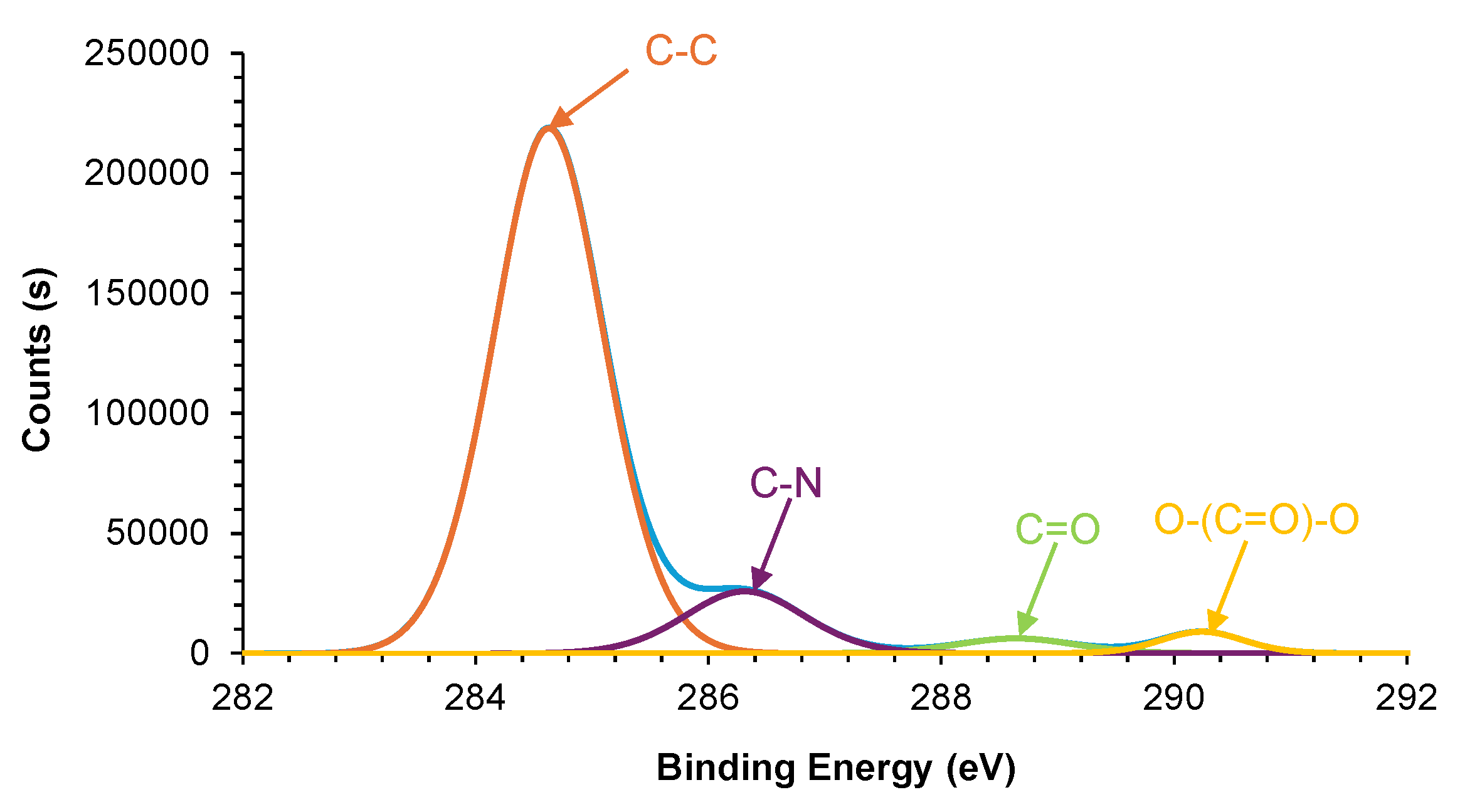

| Species | Binding energy (eV) | Percentage (at.%) | ||

| E0 | E0.5 | E1 | ||

| C-C | 284.7 | 87 | 85 | 87 |

| C–N | 286.4 | 9 | 10 | 9 |

| C=O | 288.6 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| O–(C=O)–O | 290.4 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Species | Binding energy (eV) | Percentage (at.%) | ||

| E0 | E0.5 | E1 | ||

| C=O | 531.7–531.8 | 75 | 67 | 77 |

| C–O | 533.5–533.7 | 25 | 33 | 23 |

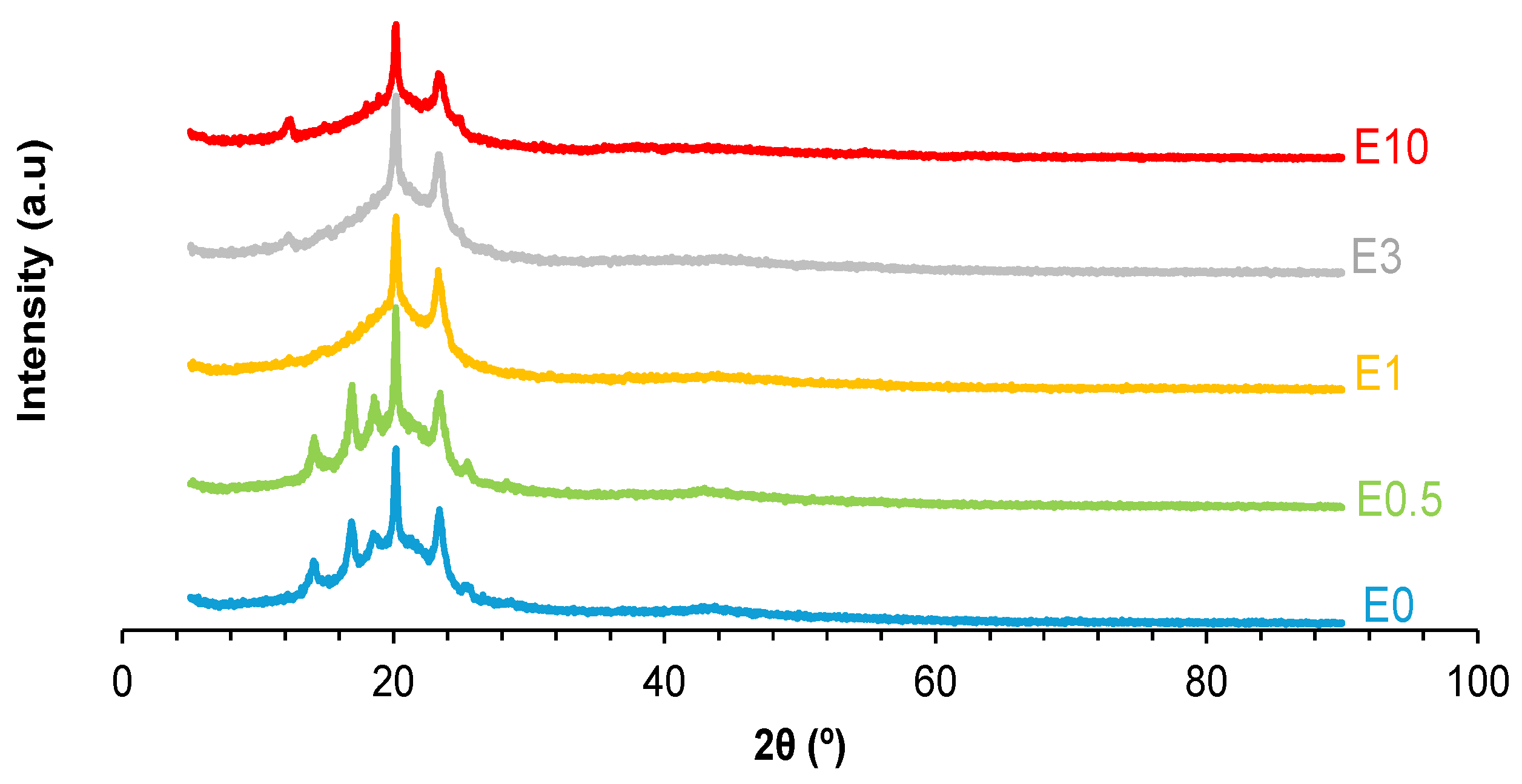

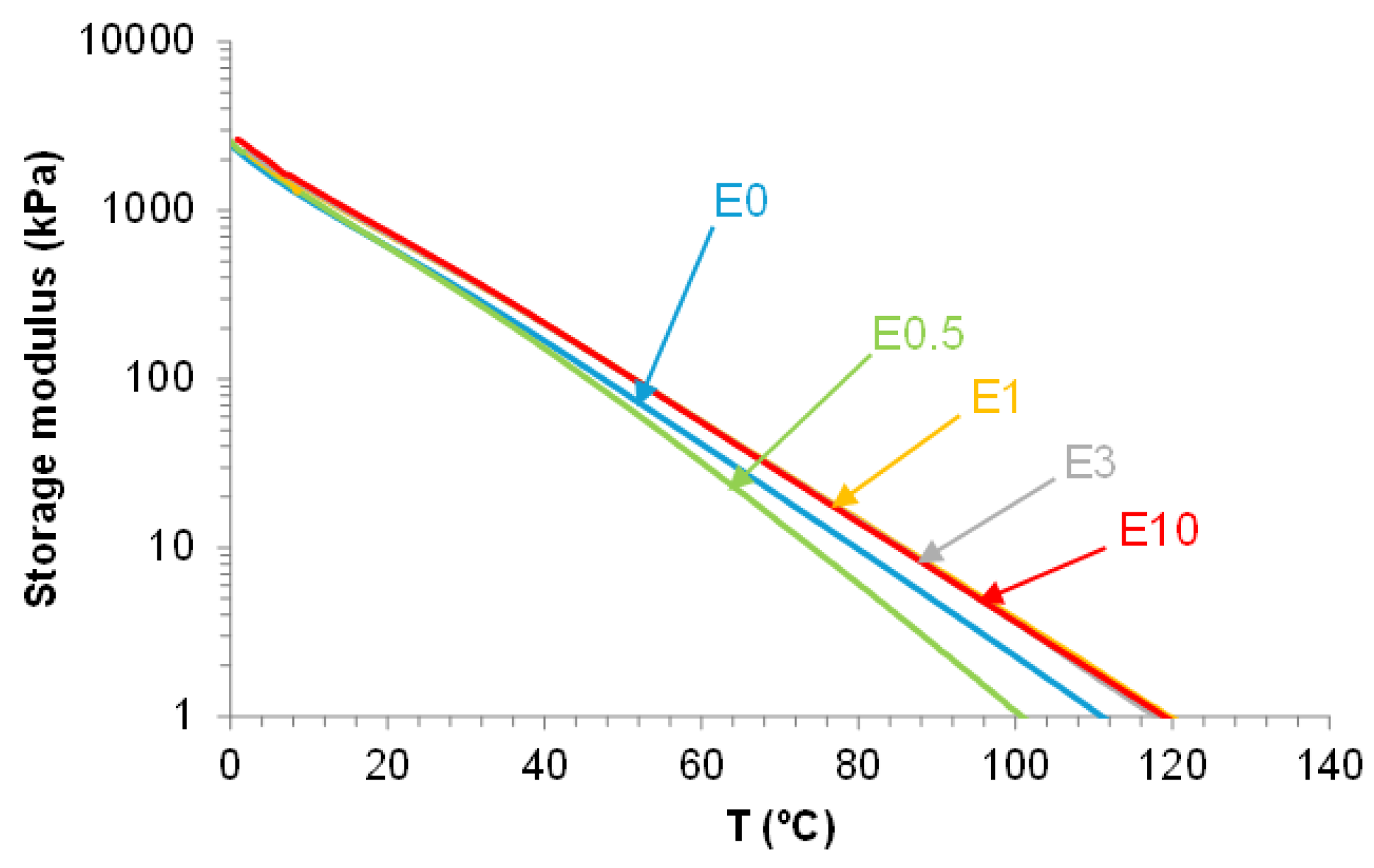

| PU | Tg (°C) | ΔCp (J/g·°C) | Tm1 (°C) | ΔHm1 (J/g) | Tm2 (°C) | ΔHm2 (J/g) |

| E0 | -21 | 0.22 | - | - | - | - |

| E0.5 | -20 | 0.20 | 42 | 7.49 | 100 | 0.12 |

| E1 | -22 | 0.32 | 39 | 0.98 | 76 | 0.25 |

| E3 | -21 | 0.37 | - | - | 91 | 0.98 |

| E10 | -22 | 0.22 | 41 | 3.30 | 61 | 0.22 |

| Halloysite | - | - | - | - | 77 | 0.66 |

|

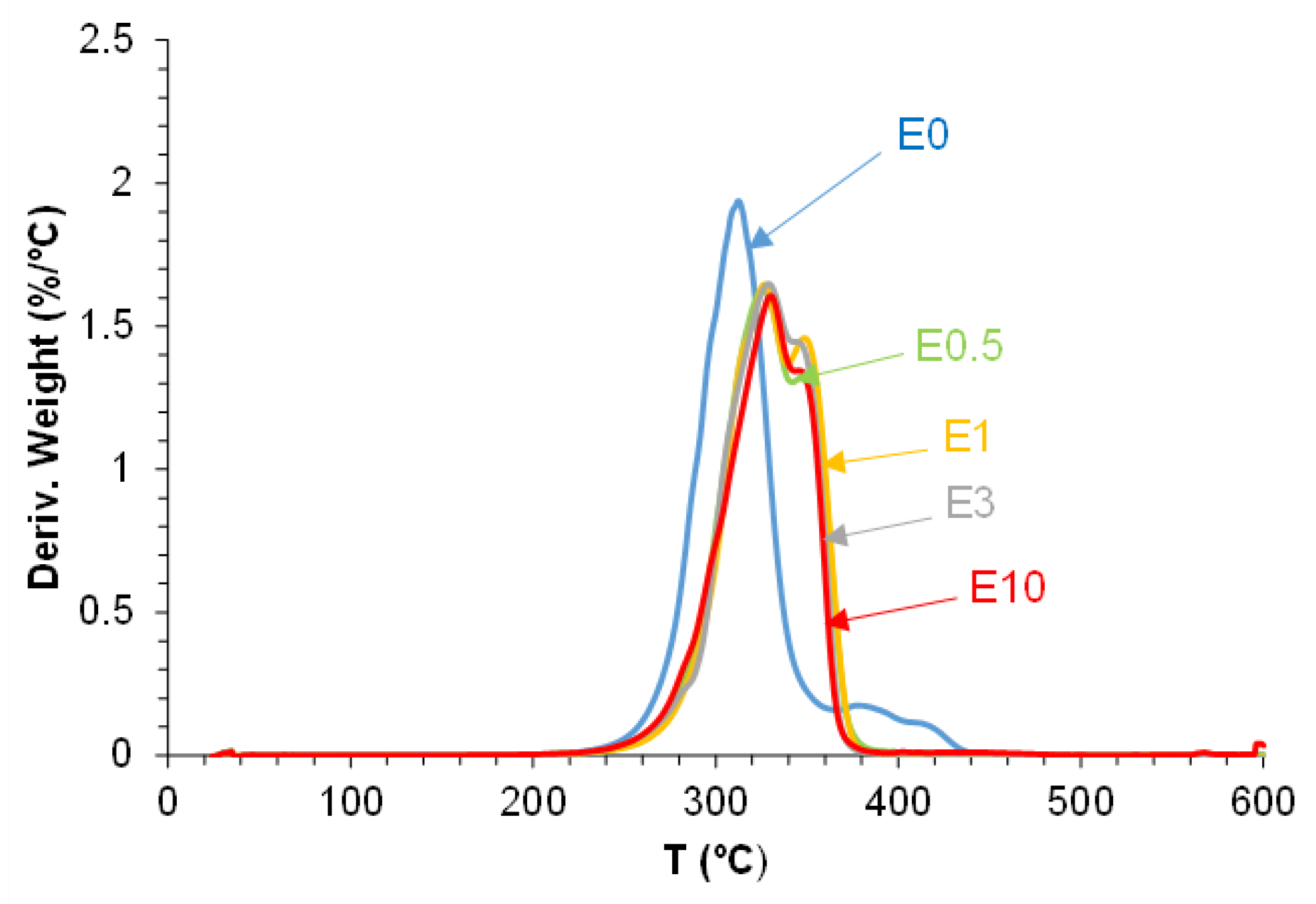

PU |

1st degradation | 2nd degradation | 3rd degradation | 4th degradation | ||||

| T1 (°C) | Weight loss1 (%) | T2 (°C) | Weight loss2 (%) | T3 (°C) | Weight loss3 (%) | T4 (°C) | Weight loss4 (%) | |

| E0 | 297 | 31 | 313 | 60 | - | - | 387 | 6 |

| E0.5 | 283 | 7 | 312 | 28 | 324 | 32 | 347 | 32 |

| E1 | - | - | 314 | 33 | 326 | 34 | 348 | 33 |

| E3 | 281 | 7 | 308 | 18 | 328 | 42 | 346 | 29 |

| E10 | 280 | 7 | 294 | 9 | 330 | 51 | 346 | 27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).