Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Preparation of MAO Film on TA1 Titanium Alloy Surface

2.3. Characterization of the MAO Coating on TA1 Titanium Alloy Surface

3. Results

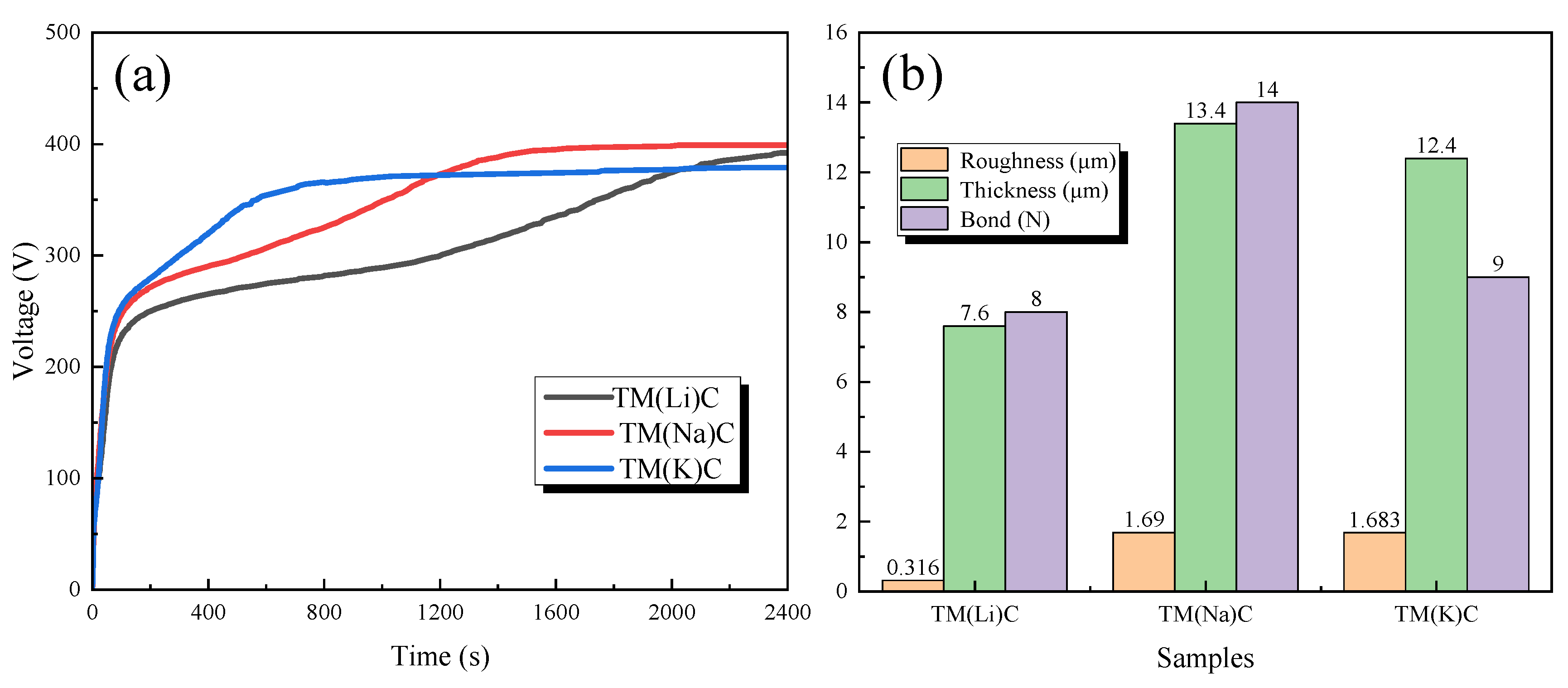

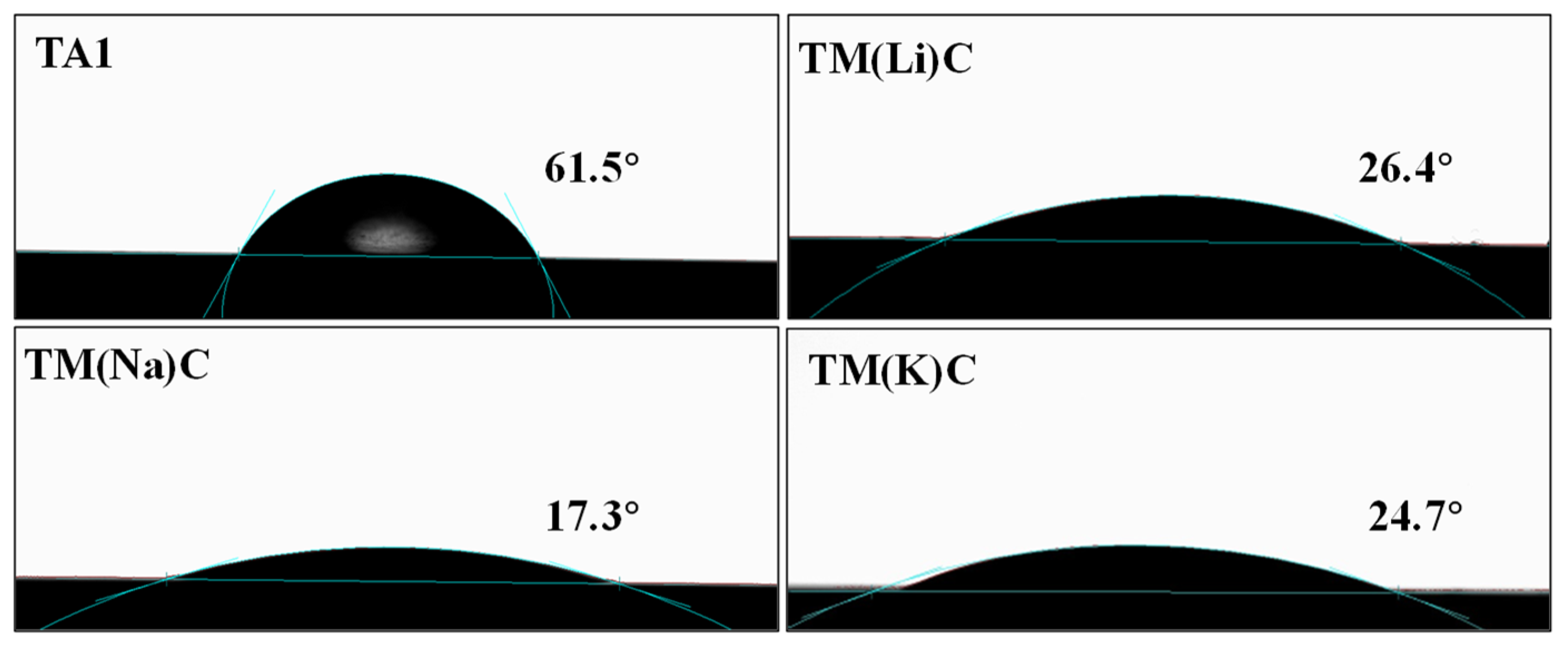

3.1. The Thickness, Surface Roughness, and Adhesion Properties of the Film Layer

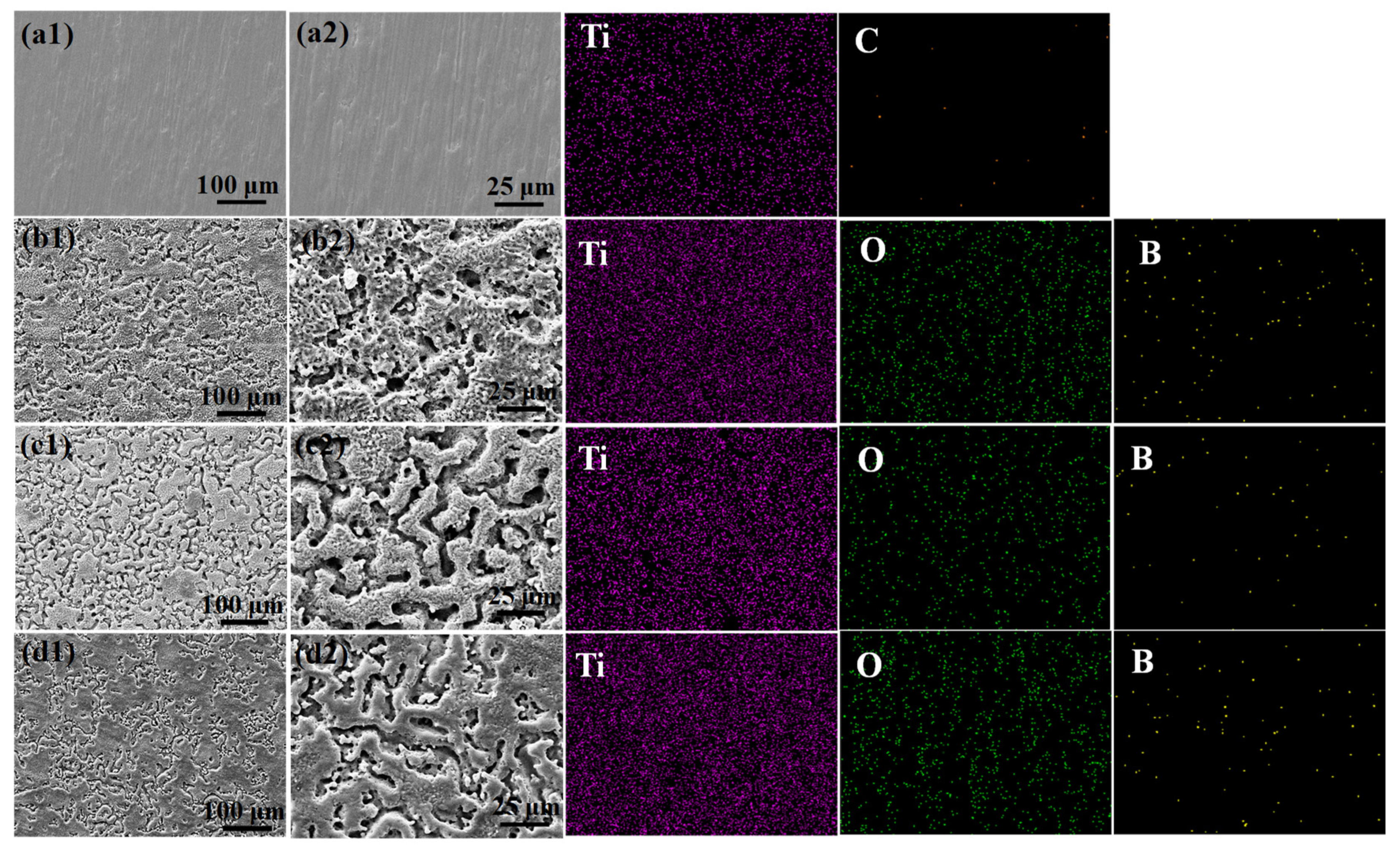

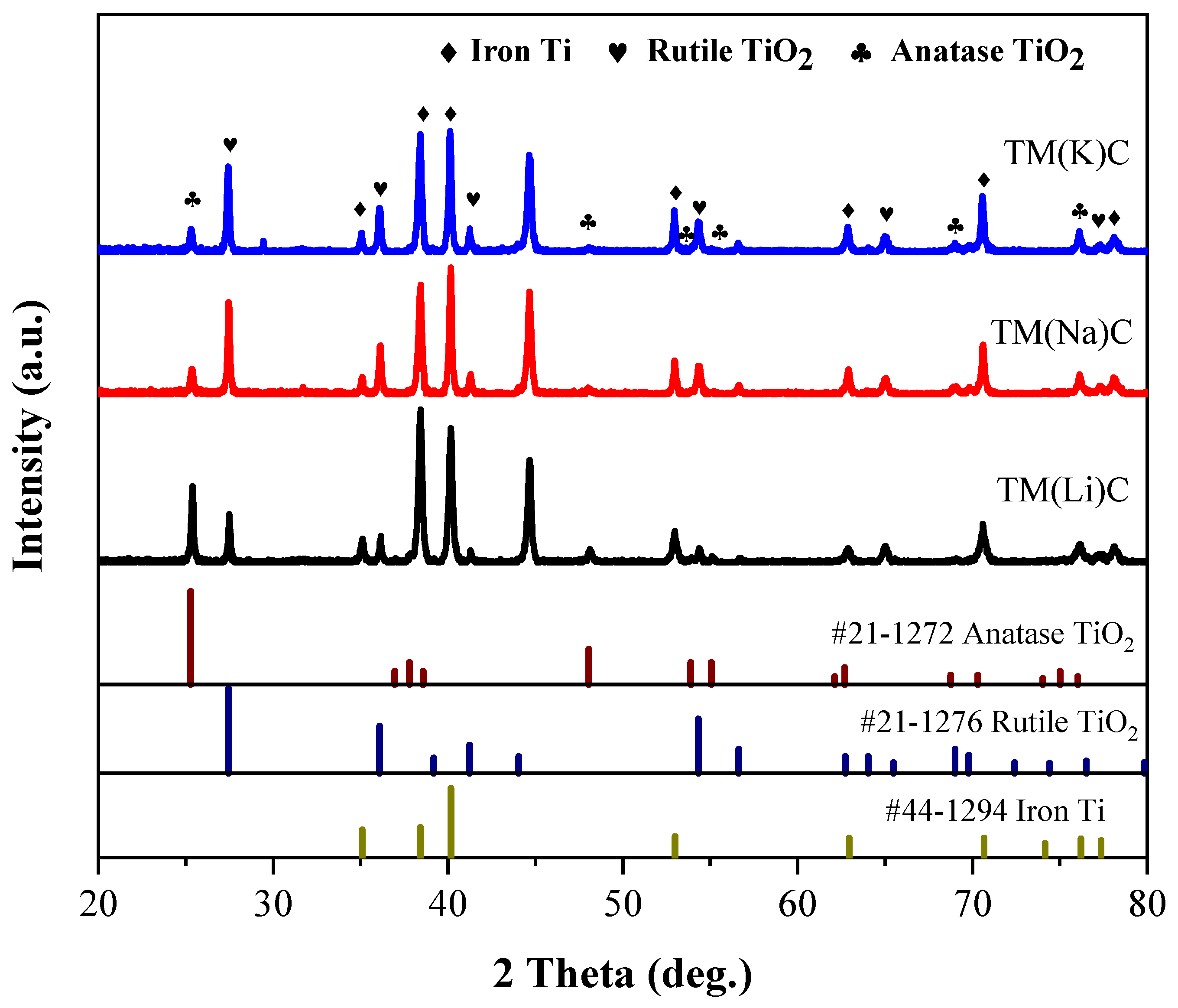

3.2. Surface Morphology and Elemental Composition

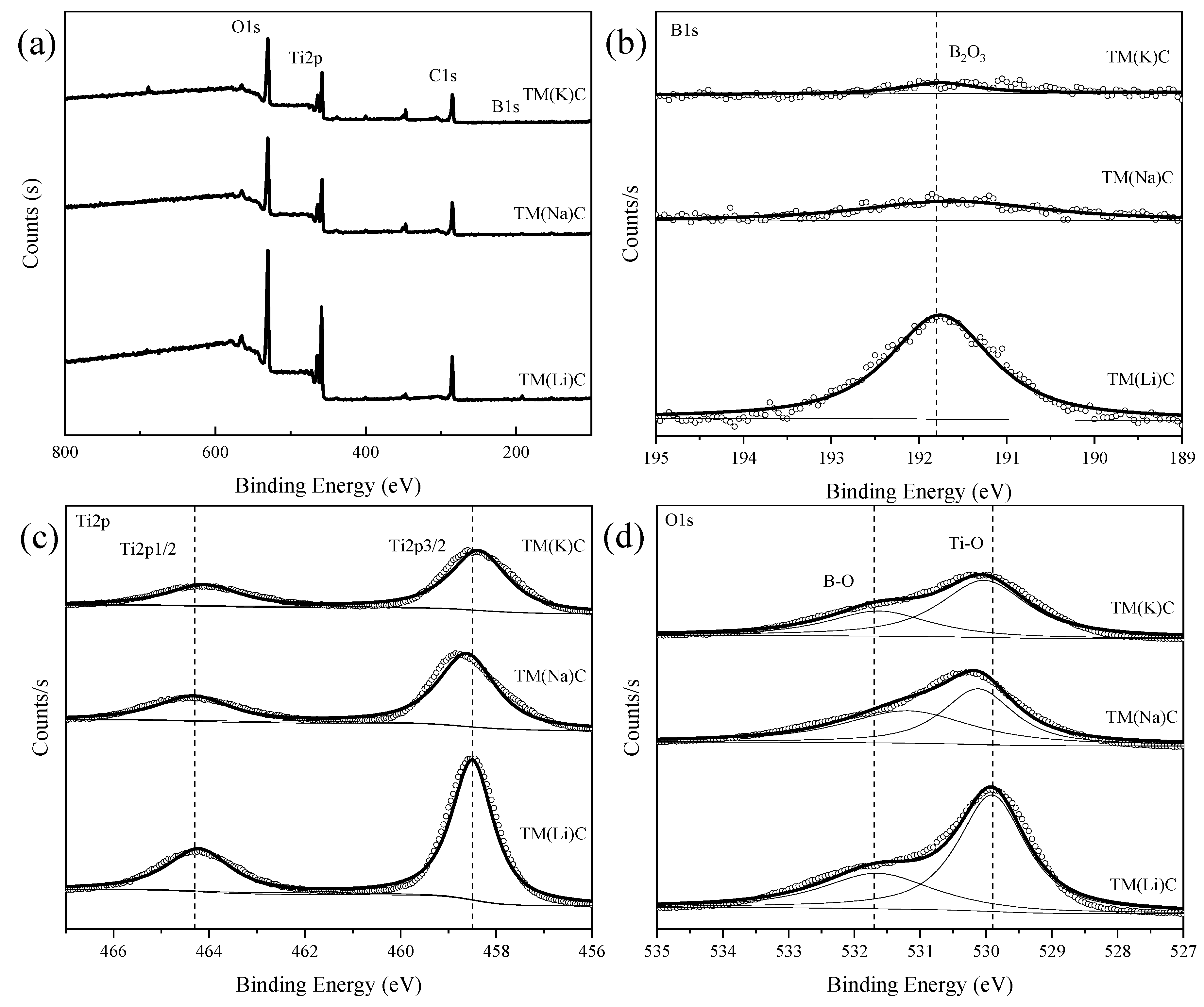

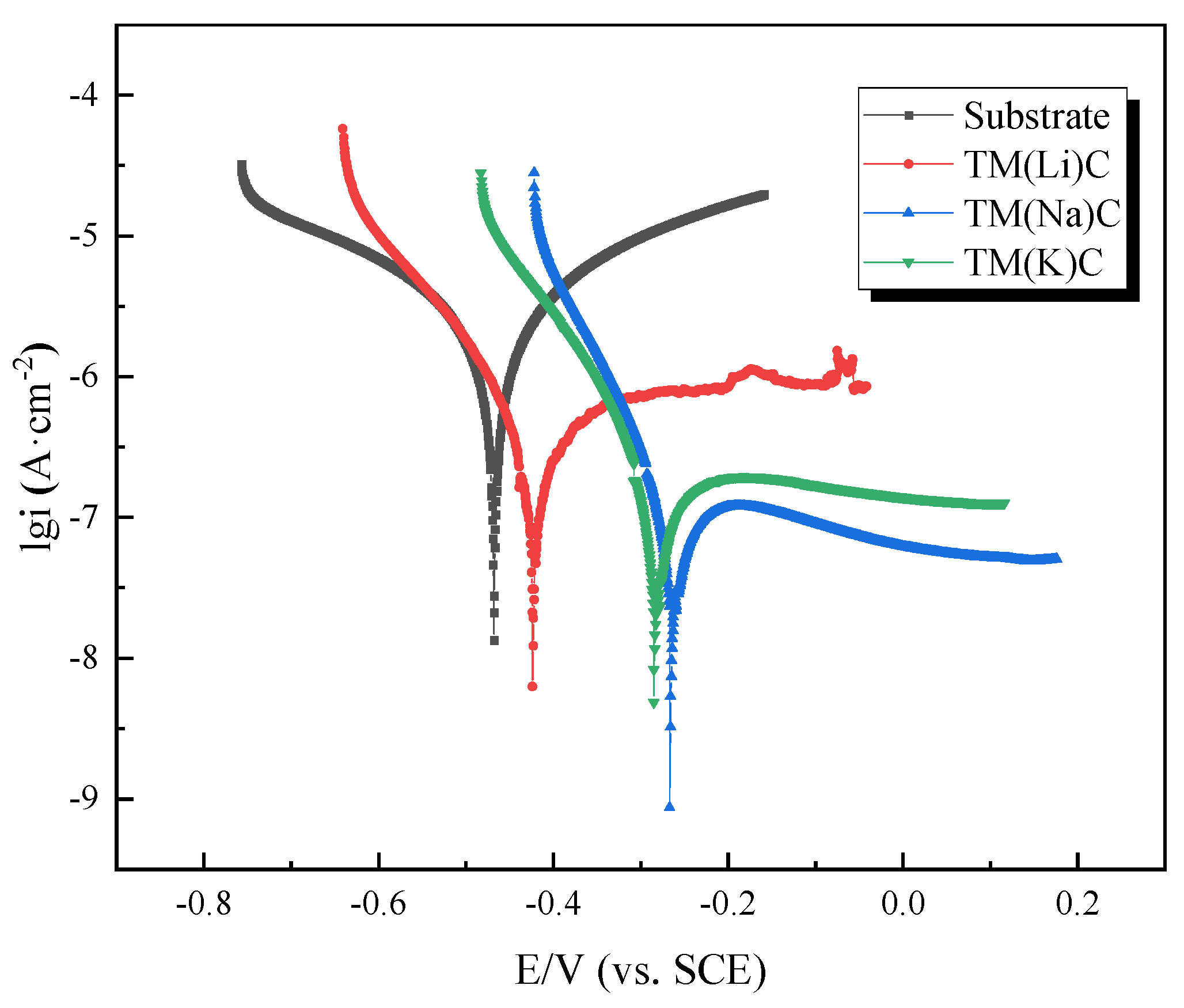

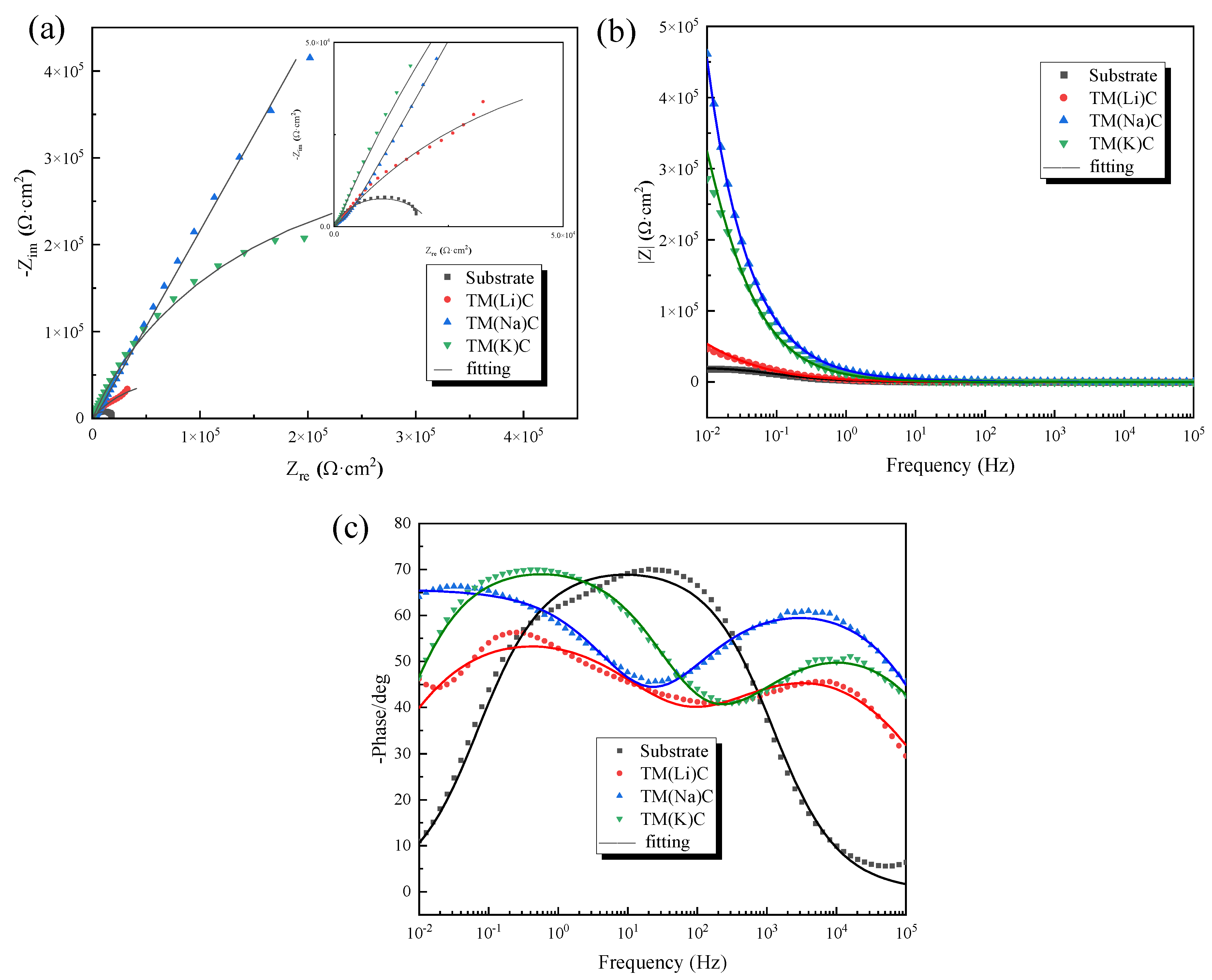

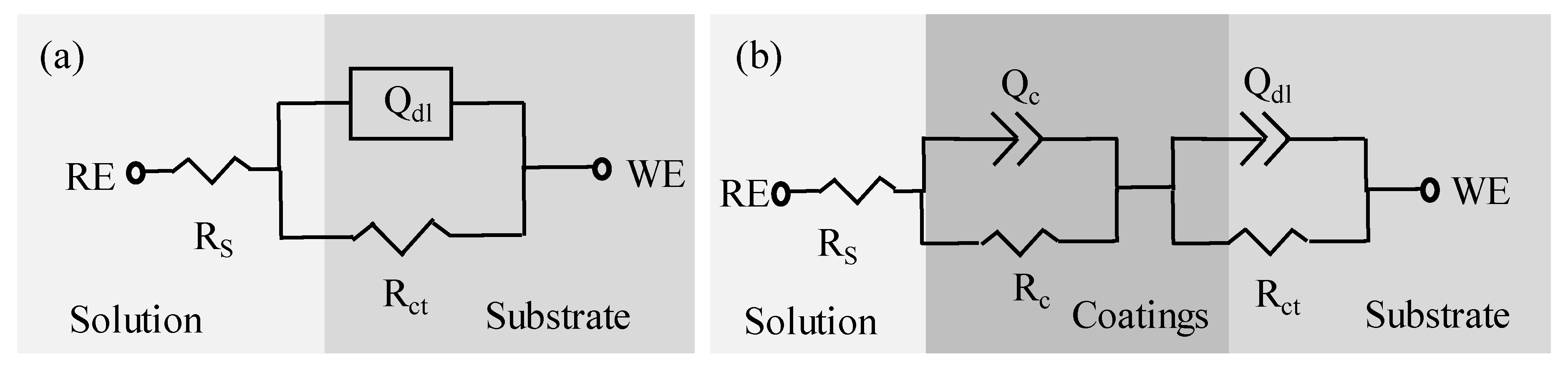

3.3. Corrosion Resistance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, L.; Wu, K.; Zhou, G.; Lan, Z. Design, Preparation, and Experiment of the Titanium Alloy Thin Film Pressure Sensor for Ocean Depth Measurements. IEEE Sensors Journal 2024, 24, 14042–14049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Dan, Z.; Lu, J.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chang, H.; Zhou, L. Research Status and Prospect on Marine Corrosion of Titanium Alloys in Deep Ocean Environments. Rare Metal Materials and Engineering 2020, 49, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, H.J.; Vollmer, D.; Papadopoulos, P. Super liquid-repellent layers: The smaller the better. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science, 2015, 222, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, T.P.; Rasitha, T.P.; Vanithakumari, S.C.; Anandkumar, B.; George, R.P.; Philip, J. A simple, rapid and single step method for fabricating superhydrophobic titanium surfaces with improved water bouncing and self-cleaning properties. Applied Surface Science 2020, 512, 145636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Shah, Z.A.; Sabiruddin, K.; Keshri, A.K. Characterization and tribological behaviour of Indian clam seashell-derived hydroxyapatite coating applied on titanium alloy by plasma spray technique. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials 2023, 137, 105550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, T.; Sun, R. Optimization of microstructure and properties of composite coatings by laser cladding on titanium alloy. Ceramics International 2021, 47, 2230–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, B.; Liu, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Bian, H. Influences of friction stir processing on the microstructure and properties of TC4 titanium alloy by laser metal deposition. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2024, 1008, 176769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.; Peretyagin, N.; Apelfeld, A.; Smirnov, A.; Morozov, A.; Torskaya, E.; Volosova, M.; Yanushevich, O.; Yarygin, N.; Krikheli, N.; Peretyagin, P. Investigation of Tribological Characteristics of PEO Coatings Formed on Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloy in Electrolytes with Graphene Oxide Additives. Materials 2023, 16, 3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jáquez-Muñoz, J.M.; Gaona-Tiburcio, C.; Mendez-Ramirez, C.T.; Carrera-Ramirez, M.G.; Baltazar-Zamora, M.A.; Santiago-Hurtado, G.; Lara-Banda, M.; Estupiñan-Lopez, F.; Nieves-Mendoza, D.; Almeraya-Calderon, F. Corrosion of Anodized Titanium Alloys. Coatings 2024, 14, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [Lan, X.; Wang, P.; Gong, Z.; Luo, X.; Zheng, Y.; Deng, B. ; Effect of Phytic Acid Modification on Characteristics of MAO Coating on TC4 Titanium Alloy. Rare Metal Materials and Engineering 2024, 53, 954–962. [Google Scholar]

- Yerokhin, A.L.; Nie, X.; Leyland, A.; Matthews, A.; Dowey, S.J. Plasma electrolysis for surface engineering. Surface and Coatings Technology 1999, 122, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M.; Salimijazi, H.R.; Golozar, M.A.; Garsivaz jazi, M.R. A Comparison of Corrosion, Tribocorrosion and Electrochemical Impedance Properties of Pure Ti and Ti6Al4V Alloy Treated by Micro-Arc Oxidation Process. Applied Surface Science 2015, 324, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Wu, L.; Wang, J.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, D.; Serdechnova, M.; Shulha, T.; Blawert, C.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Pan, F. Micro-Arc Oxidation of Magnesium Alloys: A Review. Journal of Materials Science &Technology 2022, 118, 158–180. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Sun, X.; Song, J.; Chen, J.; Gao, J.; Xiao, K. Study on Corrosion Protection Behavior of Magnesium Alloy/Micro-Arc Oxidation Coating in Neutral Salt Spray Environment. International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2023, 18, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Ma, F.; Liu, P.; Qi, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, K.; Chen, X. Review of micro-arc oxidation of titanium alloys: Mechanism, properties and applications. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2023, 948, 169773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, W.; Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Liang, J. Correlations between the growth mechanism and properties of micro-arc oxidation coatings on titanium alloy: Effects of electrolytes. Surface and coatings technology 2017, 316, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Hai, J.; Shan, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Q.; Ma, X. Effect of Na2B4O7 on Wear and Corrosion Resistance of Micro-arc Oxidation Coating on Titanium Alloy. Surface Technology 2024, 53, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Shokouhfar, M.; Dehghanian, C.; Montazeri, M.; Baradaran, A. Preparation of Ceramic Coating on Ti Substrate by Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation in Different Electrolytes and Evaluation of Its Corrosion Resistance: Part II. Applied Surface Science 2012, 258, 2416–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavarini, M.; Moscatelli, M.; Candiani, G.; Tarsini, P.; Cochis, A.; Rimondini, L.; Najmi, Z.; Rocchetti, V.; De Giglio, E.; Cometa, S.; De Nardo, L.; Chiesa, R. Influence of Frequency and Duty Cycle on the Properties of Antibacterial Borate-Based PEO Coatings on Titanium for Bone-Contact Applications. Applied Surface Science 2021, 567, 150811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, T.; Qi, M. Formation and characterization of titania coatings with cortex-like slots formed on Ti by micro-arc oxidation treatment. Applied Surface Science 2013, 266, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Lei, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, H.; Qi, M. Formation and in vitro/in vivo performance of “cortex-like” micro/nano-structured TiO2 coatings on titanium by micro-arc oxidation. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2018, 87, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.; Wei, E.; Dou, X.; He, Z. Construction of superhydrophobic film on the titanium alloy welded joint and its corrosion resistance study. Anti-Corrosion Methods and Materials 2023, 70, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, F. Influence of anions in phosphate and tetraborate electrolytes on growth kinetics of microarc oxidation coatings on Ti6Al4V alloy. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 2022, 32, 2243–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, D.; Qiu, T.; Shen, J.; Feng, K. Mechanism of tetraborate and silicate ions on the growth kinetics of microarc oxidation coating on a Ti6Al4V alloy. RSC Advances 2023, 13, 5382–5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, Y. Ionic radii in aqueous solutions. Chemical Reviews 1988, 88, 1475–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, M.O.; Fortenberry, R.C. Factors affecting the solubility of ionic compounds. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry 2015, 1069, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, R.N. Resistance of solid surfaces to wetting by water. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry 1936, 28, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignolo, M.; Romano, G.; Martinelli, A.; Bernini, C.; Siri, A.S. A Novel Process to Produce Amorphous Nanosized Boron Useful for MgB2 Synthesis. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2012, 22, 6200606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Li, L.; Shi, Q.; Che, X.; Xu, X.; Li, G. Heat capacity and thermodynamic functions of TiO2(B) nanowires. The Journal of Chemical Thermodynamics 2018, 119, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, J.F.; Chapusot, V.; Billard, A.; Alnot, M.; Bauer, Ph. Characterisation of reactively sputtered Ti–B–N and Ti–B–O coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology 2002, 151-152, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Hrbek, J.; Osgood, R. Formation of TiO2 Nanoparticles by Reactive-Layer- Assisted Deposition and Characterization by XPS and STM. Nano Letters 2005, 5, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H. 4-Electrochemical polarization technique based on the nonlinear region weak polarization curve fitting analysis. Techniques for Corrosion Monitoring (Second Edition) 2021, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Cheng, Y.; Tu, W.; Zhan, T.; Cheng, Y. The black and white coatings on Ti-6Al-4V alloy or pure titanium by plasma electrolytic oxidation in concentrated silicate electrolyte. Applied Surface Science 2018, 428, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikani, N.; Pu, J.H.; Cooke, K. Analytical modelling and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) to evaluate influence of corrosion product on solution resistance. Powder Technology 2024, 433, 119252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammelt, U.; Reinhard, G. Application of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) for characterizing the corrosion-protective performance of organic coatings on metals. Progress in Organic Coatings 1992, 21, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Chen, M.; Liu, W.; Shen, X.; Min, Y.; Xu, Q. The research on preparation of superhydrophobic surfaces of pure copper by hydrothermal method and its corrosion resistance. Electrochimica Acta 2018, 270, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Lü, K.; Chen, W.; Wang, M. Study on Preparation of Micro-Arc Oxidation Film on TC4 Alloy with Titanium Dioxide Colloid in Electrolyte. Coatings 2022, 12, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Fe | C | O | H | N | Ti |

| Content | 0.047 | 0.012 | 0.080 | 0.0004 | 0.0063 | Bal. |

| Samples | Mass percentage(wt.%) | Atomic percentage(at.%) | ||||

| Ti | O | B | Ti | O | B | |

| TA1 | 98.82 | -- | -- | 95.47 | -- | -- |

| TM(Li)C | 60.39 | 38.41 | 1.20 | 33.42 | 63.64 | 2.94 |

| TM(Na)C | 58.07 | 41.05 | 0.89 | 31.40 | 66.46 | 2.13 |

| TM(K)C | 60.88 | 37.56 | 1.56 | 33.78 | 62.39 | 3.83 |

| Samples | Ecorr(mV) | icorr(A·cm-2) | ba(mV) | bc(mV) | MPY |

| Substrate | -468.38 | 5.8027×10-6 | 472.70 | 542.89 | 4.634 |

| TM(Li)C | -412.50 | 1.5544×10-7 | 176.56 | 95.518 | 0.124 |

| TM(Na)C | -254.13 | 8.0435×10-8 | 9548.30 | 79.559 | 0.064 |

| TM(K)C | -272.39 | 8.4739×10-8 | 448.16 | 90.282 | 0.068 |

| Samples |

Rs Ω·cm2 |

Qc 10-6Ω-1·sn·cm-2 |

Qn 0<n<1 |

Rc Ω·cm2 |

Qdl 10-6Ω-1·sn·cm-2 |

Q-ndl 0<n<1 |

Rct 104Ω·cm2 |

| Substrate | 9.56 | -- | -- | -- | 8.889 | 0.7906 | 2.115 |

| TM(Li)C | 6.121 | 6.454 | 0.5774 | 295.6 | 8.36 | 0.6374 | 15.21 |

| TM(Na)C | 11.2 | 7.211 | 0.609 | 279.3 | 2.309 | 0.7733 | 55 |

| TM(K)C | 9.737 | 1.253 | 0.7484 | 427.6 | 5.155 | 0.625 | 31.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).