1. Introduction

The wide adoption of multimodal recognition systems has occurred because of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) advancements that enable the capture and processing of multimedia data content including face, object, emotion, scene, and action data for applications in various fields. These technologies are deployed to automate processes, improve efficiency, and aid in decision-making; however, they also present many privacy risks as they process vast amounts of Personally Identifiable Information (PII) such as facial biometrics, location data, and behavioural patterns. As Sharma [

23] highlights, privacy paradox causes users to engage in information disclosure behaviour despite their concerns about privacy risks, while privacy policies remain challenging to create because of this paradox [

24].

To address these concerns, Privacy Engineering (PE) has emerged as a discipline focused on integrating privacy-by-design principles into AI systems as proposed by Martin and Alamo [

25]. Hansen, Meiko Jensen and Martin Rost [

26] define PE as a systematic approach to ensure adequate data protection within organisational systems. However, most current privacy-protecting AI systems rely on static obfuscation techniques, such as blurring, pixelation, and masking, without dynamically adjusting to the environmental context or user preferences. The static obfuscation techniques lead to suboptimal privacy protection through over-masking data, thus reducing usability or under-masking data (failing GDPR compliance), which results in inadequate protection of sensitive data. The challenge is amplified in shared and dynamic environments, such as smart homes, workplaces, or public events, where privacy expectations can vary significantly depending on the contextual relationships among users, observers, and settings.

To overcome these limitations, this work proposes a user-centric, ontology-driven, and context-aware privacy protection framework that enables real-time and adaptive obfuscation based on the semantic classification of recognised entities such as users, scenes, actions, objects, emotions, soft biometric traits, including gait, hair, clothing, and privacy context. This framework draws from Nissenbaum’s Contextual Integrity theory [

22], which defines that privacy protection is not absolute but must be preserved to contextual norms such as “who is sharing what with whom and under what conditions”.

In this research, privacy context refers to the combination of actors (users), their roles, actions, relationships, and the situational parameters that define how data should be protected. This builds upon the ontology-based privacy protection models developed by Badii, Tiemann and Thiemert [

10], where ontology encodes the relationships between entities, actions, contexts, and privacy rules. Environment, in this context, refers to the spatial, temporal, and interactional conditions in which data is captured and shared. By reasoning over these elements, the framework interprets privacy context and determines how data should be protected, whether fully obfuscated, selectively masked, or left unobscured.

The proposed framework introduces several key innovations:

The use of soft biometric traits such as gait, hair type, hair colour, skin tone, age, and gender for fallback re-identification when face recognition fails to detect and recognise individuals because of occlusions.

A Re-Identifiability Index (RII) that computes the likelihood of identifying a user based on soft biometrics.

An Auto Privacy mode that uses machine learning to predict privacy preferences based on contextual data and historical behaviour.

Support for user-defined red lines, such as "always hide logos", that override any predefined user settings.

A rule-based ontology model that defines the relationships between users, entities, contexts, and privacy levels for consistent and explainable privacy decision-making.

Prior studies validate the importance of this framework. Lin and Li [

63], show that using 23 out of 30 soft attributes can yield 85% re-identification accuracy, and that combining soft traits such as hair, gender, and age boosts recognition performance by up to 6%. Similarly, Bari and Gavrilova [

60] and Corbishley, Nixon and Carter [

61] report re-identification rates at 85% when using gait and other soft biometrics, which highlight the limitations of facial masking alone.

The proposed framework builds upon these gaps by treating privacy as a multidimensional, context-sensitive process, which applies real-time obfuscation based on scene, content, and user-defined constraints. The multimodal AI pipeline of the framework integrates YOLOv5 for object recognition, MTCNN for face recognition, SlowFast for action recognition, Places365 for scene classification, and EfficientNet for emotion recognition. These recognition outputs are used to identify privacy contexts and inform the ontology-driven privacy engine, to adapt and apply masking strategies while preserving scene intelligibility and GDPR compliance. The framework also supports user-centric privacy in shared spaces by encoding privacy rules into an ontological model which also ensures transparency, scalability and explainability.

2. Related Work

Given the expansion of multimodal AI applications, concerns regarding personal privacy have increased, specifically in processing PII within video data. Although previous research [

3,

4,

5] addresses privacy-preserving techniques, significant gaps remain in such approaches as many rely on static obfuscation rules and do not adapt to user-defined preferences, real-time contextual shifts or multi-user scenarios. As a result, these models either over-mask content, undermining usability or under-mask sensitive data, compromising privacy and GDPR compliance.

Recent efforts in privacy protection have explored soft biometrics as both a challenge and opportunity. Zhou, Pun and Tong [

67] highlight the limited exploration of dynamic face pixelation as a method and its inefficiencies in highly dynamic settings. Similarly, Hasan, Shaffer, Crandall and Kapadia [

5] and Lin and Li [

63] demonstrate that soft biometric features, such as gait, hair type, skin tone, age and clothing attributes can lead to re-identification even when faces are obscured. For instance, Lin and Li [

63] show that using 23 out of 30 soft attributes can yield an 85% identification rate, reinforcing the privacy risks posed by non-facial attributes. However, few systems integrate these cues into a coherent privacy enforcement model.

Existing privacy protection methods either do not recognise soft biometric features to identify individuals with the aim of personalised privacy protection or fail to dynamically adjust obfuscation based on contexts or user red line. In contrast, the proposed framework improves on this by incorporating a user-centric, ontology-driven privacy framework that models the relationships between users, visual entities (faces, objects, actions, emotions), environmental context, and user-defined privacy red lines. This framework incorporates:

Soft biometric analysis as both a fallback to face recognition and a standalone re-identifiability risk factor.

A Re-Identifiability Index (RII) that quantifies re-identifiability risk and advises dynamic masking decisions.

Support for user-defined red lines such as "always hide logos", which override any predefined settings.

Support for Auto Privacy through supervised learning, predicting privacy settings needs based on scene type, emotional state and prior user behaviour.

An ontology-based reasoning model, that defines the relationships between users, entities, contexts, and privacy levels for consistent and explainable privacy decision-making.

Unlike prior methods such as those of Hasan, Shaffer, Crandall and Kapadia [

5] and Zhou, Pun and Tong [

67], which apply uniform, static rules, the proposed framework uses semantic inference to guide privacy decisions on a frame-level and user-centric basis. It addresses the balance between intelligibility and privacy by using contextual cues such as location, scene category or action type, and balancing these with user defines privacy settings and red lines.

The proposed framework extends the state of the art by embedding contextual integrity, real-time adaptability and re-identifiability assessment within a unified and scalable privacy protection pipeline. Its ontology-based reasoning capability enables the framework to reason over context, that makes it particularly effective in complex and multi-user environments. In doing so, it directly addresses key challenges in intelligent, context-aware privacy preservation.

2.1. Privacy Challenges in Multimodal AI Systems

Modern AI systems increasingly combine multiple recognition capabilities including face, scene, object, emotion, and action recognition to enable more automatic operations within a variety of applications. However, the processing of such large quantities of PII data creates major privacy risks while posing challenges to data security, user control, and regulatory standards specifically outlined under GDPR [

1]. The ability of AI systems to extract specific attributes such as identity and location data points leads to serious privacy issues regarding profiling practices, mass surveillance, and unauthorised data misuse [

2].

The continuous growth of location-based services intensifies this concern as stated by Jiang, Li, Zhao and Zeng [

28], that the ubiquity of GPS-enabled applications has led to pervasive location tracking. Castillo [

18] reveals that 94% of smartphone users conduct searches for location-specific data, and 72% are targeted by location-aware advertisements, which indicates the comprehensive utilisation of personal data for both commercial and possibly intrusive activities.

A key challenge is the lack of adaptive privacy methods as existing privacy methods use static privacy models and fail to adapt to the changing user preferences, entity sensitivity and dynamic contexts [

3]. These methods use anonymisation techniques such as blurring and pixelation that provide a level of privacy protection [

4] but seriously diminish data utility as shown by Hasan, Shaffer, Crandall and Kapadia [

5]. Insufficient protection could lead to re-identifying anonymised data through cross-referencing with external datasets making privacy protection countermeasures complex and difficult to manage as an evolving requirement [

14]. More critically, re-identification through soft biometric traits, like gait, hair colour, age, or clothing style, can be used to cross-reference and identify individuals even after standard anonymisation. Sosa, Fierrez and Vera-Rodriguez [

62] demonstrate that using a wide range of soft biometric attributes can yield re-identification accuracies exceeding 85%, raising significant risks that most systems fail to address.

Another major challenge for organisations today is regulatory compliance. The GDPR requires necessary data minimisation tactics alongside transparency about data use and formal consent (European Commission, 2016) but most AI systems fail to effectively implement privacy-by-design solutions according to Gurses, Troncoso and Diaz [

6]. Current permission-based frameworks show inadequate results because users do not understand them well enough and lack the ability to adapt to different contexts [

2]. Additionally, current methods are not adequately developed to effectively manage multi-user privacy requirements noted by Sezer, Dogdu and Ozbayoglu [

11]. The collaborative AI environments within smart homes and video conferences require individual and robust privacy settings regardless of differing user requirements as noted by Ren, Lee and Ryoo [

7]. The predefined privacy options used in current systems fail to adapt dynamically to changing image contexts, alongside user states or detected objects, leading to privacy vulnerabilities.

This research addresses these gaps, by introducing a user-centric, context-aware, and ontology-driven privacy protection framework. Rather than treating privacy as a fixed set of permissions, the framework reasons over the privacy context, including the roles of actors, the nature of their interactions, the setting, and the likely exposure of visual data. It integrates soft biometric-aware fallback mechanisms, supports user-defined red lines and dynamically adapts privacy decisions using a Re-Identifiability Index (RII). These mechanisms enable the framework to deliver robust, real-time privacy protection that is user-centric and compliant with regulatory standards.

2.2. User-Centric Privacy Protection and PII Risks in AI

The increasing use of AI systems that integrate facial recognition, location data, behavioural patterns and emotion analysis, has increased concerns about the protection of PII, such as facial attributes, behavioural signs and location history. These systems that handle sensitive user data create multiple privacy risks as they enable unauthorised profiling practices, potential identity theft, and breaches of personal data security [

2]. Despite regulatory frameworks such as the GDPR mandating user control and explicit consent, current privacy frameworks do not adapt to changing user preferences dynamically when managing their data, and they remain unable to grant suitable control over user data [

69].

Current fixed privacy-preserving mechanisms prove inadequate because they lack contextual specificity, do not accommodate user-defined privacy thresholds and adaptability in their design [

5,

70]. Such fixed privacy configurations fail to match diverse user requirements and might provide inadequate or excessive security protection to users [

2]. The lack of contextual sensitivity is problematic in environments where privacy expectations vary, such as between public and private settings or when multiple users with unique privacy preferences share the same scene.

In user-centric privacy frameworks, the privacy options must be transparent, customisable, and adaptable based on individual preferences [

6]. The GDPR reinforces this by requiring mechanisms that grant users control over their data, minimise data collection, and seek explicit consent but many AI systems do not provide real-time capabilities to adjust privacy settings [

1]. As Olejnik, Dacosta, Machado and Huguenin [

2], further highlights, users need systems that enable them to set and update privacy preferences through real-time adaptations to maintain privacy and align with personal expectations.

This research addresses these gaps by introducing a user-centric, real-time adaptive privacy framework that enables fine-grained control over sensitive data through ontology-based reasoning, soft biometric-aware re-identification mitigation and auto privacy mode. Ontology-based reasoning structures the relationships between users, entities (e.g. faces, logos, actions, objects), and privacy settings to inform conflict resolution and consistent enforcement. Soft biometric-aware re-identification mitigation uses fallback traits such as gait, hair type, skin tone, age and gender when face recognition fails, supported by a Re-Identifiability Index (RII) to assess risk dynamically. Auto Privacy mode uses supervised learning to predict privacy preferences from prior user behaviour and contextual cues, enabling automatic enforcement without constant manual intervention.

By combining these mechanisms, the framework ensures compliance with GDPR, while maintaining user-led privacy protection that evolves with both contextual sensitivity and user intent. This ensures that privacy enforcement remains meaningful, personalised, and operationally efficient in multimodal AI environments.

2.3. Context-Aware and Dynamic Privacy Adaptation Techniques

Privacy requirements in multimodal AI systems vary according to context, which consists of location, time elements, user interactions, and environmental factors. Current static privacy models lack adaptability as they do not adjust privacy settings to changing data sensitivity levels or user-defined privacy preferences, thus resulting in either too much sharing of data or too much data concealment [

2]. A context-based privacy protection framework addresses this issue by updating settings dynamically based on user privacy settings, scene elements, the detected objects, emotions and user actions being processed [

6].

To address this, our framework adopts a context-aware and ontology-driven design, dynamically adjusting privacy protection [

7] according to scene type, recognised entities, user interactions, and individual privacy preferences. It builds upon Nissenbaum’s Contextual Integrity theory [

22], which conceptualises privacy not as a universal right but as a context-bound expectation based on appropriate information flow between actors, under specific roles and transmission principles. Privacy is considered violated when personal data is shared outside of these context-appropriate boundaries, for example, when a bedroom scene is shared publicly without user consent.

In our framework, privacy context refers to the semantically structured interpretation of the setting, the actors involved, their relationships and the expected exposure or sharing pathways of the data. This context includes spatial, social and temporal factors, as well as the intended or likely recipients of the data. By encoding this interpretation within an ontology, our framework supports machine-understandable privacy reasoning that adapts protection measures to the actual situational configuration.

This work extends and builds on the foundational contributions by Badii, Einig, and Tiemann [

8], who introduced the Holistic Privacy Impact Assessment (H-PIA) framework, and by Badii and Al-Obaidi [

9], who demonstrated privacy protection via semantic scene classification. We extend these ideas with real-time multimedia analysis and user-defined rules, delivering an explainable and scalable framework. Furthermore, Badii, Tiemann and Thiemert [

10] highlight that privacy reasoning should integrate heterogeneous data sources into a unified model.

This has been achieved in this framework through an ontology-based structure that formalises how users, entities and scenes relate to privacy sensitivity. The ontology-driven model enables the framework to:

Categorise detected scenes into private, semi-private or public sensitivity, based on predefined ontological rules that determine the baseline privacy level applicable to the scene.

Evaluate entity sensitivity of recognised faces, actions, objects and emotions, which are scored based on visibility, semantic significance and sensitivity class that inform the level of masking needed.

User-specific privacy preferences, where individuals can define their preferred level of privacy protection (None, Low, Medium, High, Auto) and specific red lines (e.g., "always hide logos"), which override context-based inferences.

Once the context is identified, the framework dynamically determines privacy protection levels based on the interaction between scene, entity and user-defined factors, such as public, semi-private and private settings. In public settings, only sensitive entities classified as highly sensitive are masked to preserve usability while reducing re-identification risks. In semi-private settings, medium privacy protection is applied, which ensures that all sensitive and semi-sensitive entities are automatically obfuscated. Moreover, in private settings, high level of privacy protection is applied to ensure that all user-sensitive data, such as faces and all sensitive and semi-sensitive objects are obfuscated.

Unlike current approaches, the proposed framework continuously interprets the privacy context as a combination of actors, attributes and exposure trajectories. It dynamically determines protection strategies using semantic rules, machine learning predictions and ontology reasoning. This ensures compliance with GDPR principles of data minimisation and user consent [

1] and practical usability for users in real-world and multi-user settings.

2.4. Multi-User Privacy Protection Mechanisms

Privacy management within multi-user settings presents specific challenges in video conferencing, surveillance and collaborative areas according to Sezer, Dogdu and Ozbayoglu [

11]. Guo, Zhang, Hu, He and Gao [

12] highlight that current privacy settings typically apply uniform privacy configurations across all users and disregard individual preferences and contextual interactions. This results in two key limitations: over-protection, where excessive obfuscation reduces scene intelligibility and usability or under-protection, where privacy-sensitive user data remain insufficiently protected [

13].

A major limitation in existing approaches is their lack of adaptability to dynamic group interactions and contexts. Gurses, Troncoso and Diaz [

6] highlight the need for real-time, personalised privacy control, that could ensure that each user’s privacy settings are maintained while enabling seamless collaboration. Most current systems do not support context recognition or negotiation between conflicting user preferences.

The proposed framework addresses these challenges by introducing a multi-user adaptive privacy framework that reasons over privacy contexts, defined as structured combinations of users, roles, data types and scene categories:

Detect and classify multiple users in real-time, assigning privacy levels based on individual preferences and contextual factors.

Dynamically adjust privacy measures based on user privacy protection settings (High, Medium, Low, or Auto Privacy), contextual ontologies to differentiate between environments (e.g., workplace, public park or private home), and sensitivity of scenes, objects, emotions, and actions.

Enable multi-user privacy by enabling each individual to have their privacy settings to fulfil their needs and balance the privacy of each individual and the usability and intelligibility of the system. High-privacy users receive strict obfuscation, even if others in the scene have lower privacy settings.

Maintain intelligibility through adaptive filtering by ensuring that shared privacy contexts (e.g. collaborative spaces) are preserved without compromising individual privacy expectations.

By integrating real-time user recognition and privacy adaptation, the proposed privacy protection framework ensures personalised privacy protection in shared settings, real-time adaptation to context, user preferences and visual content, while complying to GDPR processing of sensitive personal data. By encoding privacy reasoning into an explainable, ontological structure, the framework enables AI systems to balance individual privacy protection with shared scene intelligibility, even in complex and multi-user scenarios.

2.5. Performance vs. Privacy Trade-Offs in AI Systems

Balancing privacy protection and performance is a major challenge in multimodal AI systems especially under real-time conditions. Studies confirm that privacy-preserving techniques help protect against re-identification according to Narayanan and Shmatikov [

14], yet Liu, Song, Liu and Zhang [

13] demonstrated that privacy-enhancing mechanisms may lead to accuracy degradation, creating trade-offs between usability and privacy robustness. Real-time AI applications should have a balance between computational efficiency and privacy protection, as these systems require high-speed processing. Studies by Sezer, Dogdu and Ozbayoglu [

11] and Zhou, Wang, Liang and Wang [

30] emphasise that sophisticated privacy methods such as obfuscation and encryption, produce latency and require high computational resources. Gurses, Troncoso and Diaz [

6] further underscore the need for efficiency in resource-constrained environments, as excessive computational load can hinder responsiveness and user experience.

Privacy protection through obfuscation measures helps protect sensitive data but can lead to performance reductions and visual interpretability. The findings from Olejnik, Dacosta, Machado and Huguenin [

2] demonstrate that over obfuscation reduces system reliability by causing performance problems between maintaining privacy integrity and preserving scene intelligibility.

To address this trade-off, the proposed framework introduces a context-aware, adaptive privacy model that adapts obfuscation dynamically based on user preferences, scene sensitivity and the semantic classification of detected entities. Unlike current approaches, it applies obfuscation only to privacy-sensitive elements including faces, personal items and sensitive objects, that preserves visual intelligibility and reduces unnecessary computational load. Moreover, GPU acceleration and algorithmic optimisation ensure that privacy enforcement operates within real-time constraints, maintaining both protection quality and responsiveness.

2.6. Comparison of Existing Approaches and Research Gaps

Existing privacy-preserving approaches in multimodal AI systems fall into static privacy models and permission-based frameworks, both of which face significant limitations in handling dynamic user preferences, contextual variability and multi-user interactions. The current privacy-preserving approaches encounter significant limitations when dealing with critical real-time AI applications that process large volumes of Personally Identifiable Information (PII) such as facial attributes, emotional expressions, and behavioural cues.

Conventional anonymisation techniques, such as blurring and pixelation, provide a fixed level of privacy protection as stated by Frome, Cheung and Abdulkader [

4], but fail to accommodate evolving user needs or varying sensitivity levels of data stated by Hassan, Shaffer, Crandall and Kapadia [

5]. Narayanan and Shmatikov [

14] demonstrate that static obfuscation methods may fail to prevent re-identification when combined with external data, hence rendering privacy protections less effective in real-world applications. Similarly, Olejnik, Dacosta, Machado and Huguenin [

2] states that systems that rely on manual user settings meet usability challenges, as users often struggle to understand and manage their privacy settings effectively. Additionally, Gurses, Troncoso and Diaz [

6] and Ren, Lee and Ryoo [

7] have shown that current AI-driven privacy methods lack transparency, and context-awareness and often do not scale well in real-time, multi-user or real-time environments.

Moreover, recent studies, such as Sezer, Dogdu and Ozbayoglu [

11] report that current privacy methods use fixed general privacy settings that fall short of accommodating modern AI-driven applications including social media platforms and collaborative workspaces. Liu, Song, Liu and Zhang [

13] further identify key challenges in ensuring real-time efficiency, scalability, and GDPR compliance. They pointed out that existing privacy mechanisms often result in over-protection, which reduces data usability, or under-protection, which compromises privacy protection.

Among the few context-aware frameworks, the Holistic Privacy Impact Assessment (H-PIA) framework by Badii, Einig and Tiemann [

8] represents a significant contribution. Their model treats privacy filtering as a multi-layered process involving technical and human-centric factors.

Later work by Badii and Al-Obaidi [

9] introduced a context-aware filtering strategy that applied different obfuscation techniques to face, skin and body regions. Their framework aimed to balance Privacy, Intelligibility and Pleasantness, taking under consideration recognisable attributes such as race and gender still impacted perceived privacy. Although this marked progress toward adaptive privacy filtering, it lacked semantic reasoning, user-defined red lines, or integration with multimodal entity recognition at the data-instance level (e.g., recognising faces, objects, and actions within each frame and assigning them context-specific re-identifiability risks).

Further foundational work by Badii, Tiemann and Thiemert [

10] proposed the use of semantic data integration and ontology-based modelling for improving situational awareness in security applications. Their system showed that data from heterogeneous sources, such as CCTV footage, could be unified under an ontology-driven structure that enabled rule-based reasoning and decision support. While not directly focused on user-centric privacy, their methodology forms a critical foundation for semantic reasoning and context modelling adopted in the proposed framework.

Building upon these foundational works, this research proposes a real-time, user-centric and ontology-driven privacy protection framework that operationalises contextual reasoning through entity-level sensitivity classification, soft-biometric risk modelling, and adaptive obfuscation. It unifies the technical robustness of earlier privacy filters, the context-aware aspirations of MediaEval [

9] approaches, and the structured semantic reasoning of MOSAIC [

10] under a scalable, GDPR-compliant, and multi-user capable system for privacy protection in multimodal AI.

3. Methodology

3.1. Framework Overview

The proposed user-centric, context-aware privacy protection framework integrates multimodal AI recognition with adaptive privacy enforcement to ensure real-time protection of Personally Identifiable Information (PII). It processes video data, classifies the sensitivity of detected elements and dynamically modulates privacy levels based on user-defined preferences, contextual factors, soft-biometric attributes, a Re-Identifiability Index (RII) that quantifies re-identification risk and sensitivity of detected entities. The framework is structured into three main modules, where each is responsible for a specific aspect of privacy adaptation and enforcement:

The Recognition Module uses state-of-the-art AI models such as YOLOv5 for object recognition, MTCNN for face recognition, and Places365 for scene classification to extract and analyse contextual information from video streams. It identifies privacy-sensitive entities, including faces, objects, actions, emotions, and scenes, along with soft biometrics including gait, hair type, age and gender, that are used to calculate RII, when facial recognition fails. These outputs are passed into contextual risk analysis for real-time privacy decision-making.

The Privacy Enforcement Module computes the appropriate privacy levels dynamically by classifying detected entities into privacy-sensitive categories such as private, semi-private or public. Based on sensitivity, it applies privacy-preserving techniques such as blurring, pixelation, silhouette masking, or synthetic data replacement (GAN-based anonymisation) [

16]. The framework aligns obfuscation intensity with user preferences and entity sensitivity to strike a balance between privacy protection and usability. In multi-user settings, it supports personalised enforcement, strictly protecting high-privacy users even when others share lower privacy levels.

Privacy Reasoning and User Context Module, captures, and reasons over user-defined privacy rules using ontology-based logic to ensure structured, consistent, and context-aware decision-making. It supports multiple privacy modes (Auto Privacy, High, Medium, Low and No Privacy), enforces red-line rules (e.g., always hide logos), and adapts protections in real time based on scene dynamics and feedback from AI recognition modules. It also handles Auto Privacy Mode, which uses supervised learning to predict preferred privacy configurations from historical user behaviour and contextual cues.

By combining multimodal recognition, dynamic privacy adaptation, ontology-based reasoning, and user-driven privacy settings, this framework maintains strong privacy protection without compromising framework usability or scene intelligibility. It is deployable in a variety of environments including smart homes, video conferencing platforms, and public surveillance contexts.

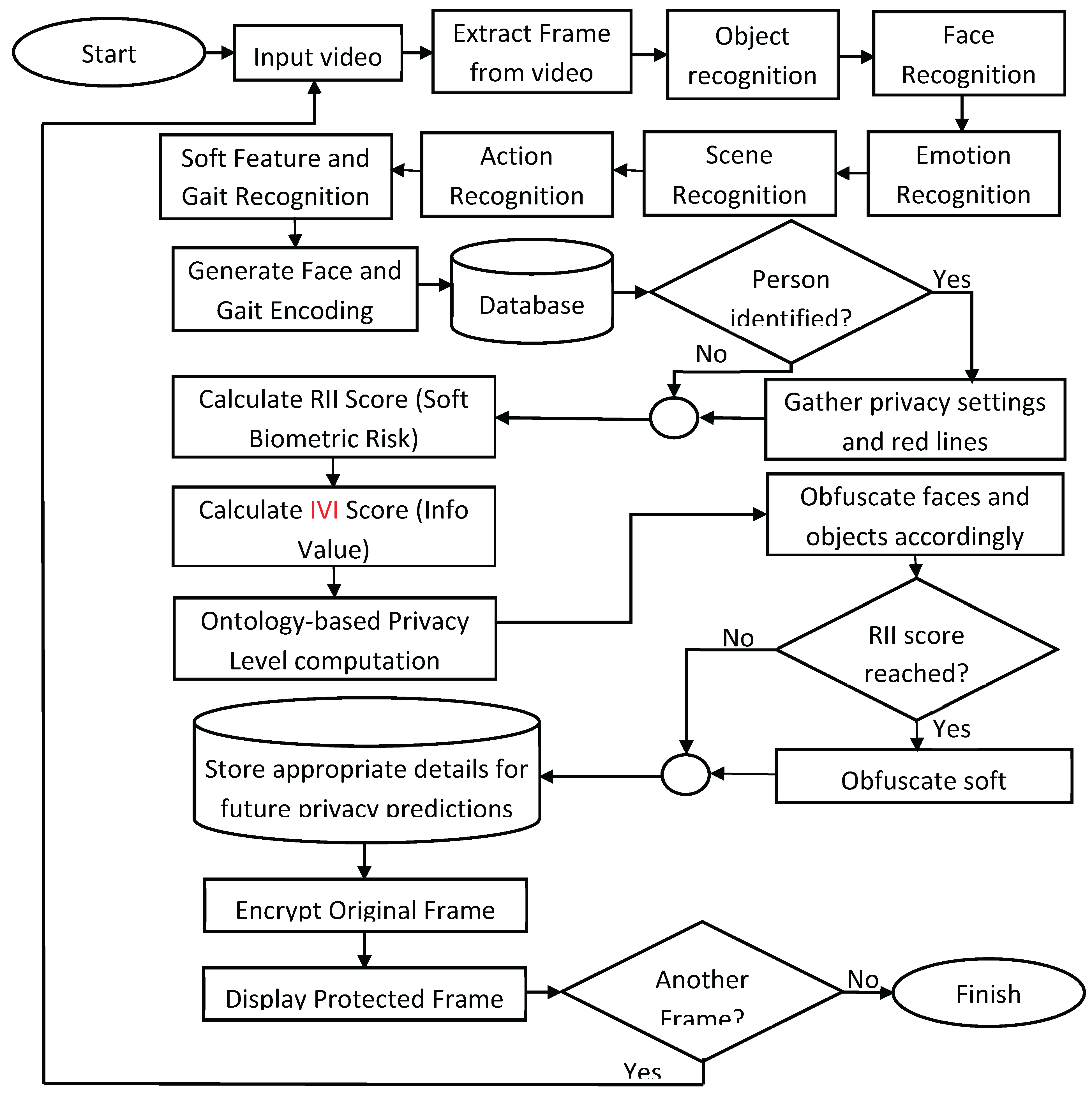

Figure 1 illustrates the high-level architecture, showing how recognition modules, context reasoning and enforcement pipelines interact to deliver adaptive privacy protection.

This layered design supports real-time, context-aware privacy decisions by integrating multimodal recognition, ontology-based reasoning, and user-centric policy enforcement into a unified, adaptive framework.

3.2. Context-Sensitive Privacy Mechanisms

Context-sensitive privacy ensures that privacy protection is dynamically adjusted based on the sensitivity of detected entities and environmental context. Unlike static privacy models [

3,

4,

5], which apply fixed privacy settings regardless of context, our framework follows Nissenbaum’s Contextual Integrity Theory [

22] which asserts that privacy norms depend on the interplay between actors, information types, and contextual setting. To operationalise this, the framework combines ontology-driven knowledge representation with real-time AI inference. The ontology captures privacy preferences alongside contextual semantics such as scene type, emotional expression, action, and soft biometric traits. It enables reasoning over privacy decisions by evaluating what is shown, to whom, in what context and under what user-defined constraints. We define two types of contexts that shape privacy decisions:

Frame context, that defines what is happening on the scene (e.g. people, objects, activities).

Exposure, where and to whom the context will be visible (e.g. social media, shared in public, private message).

These contexts influence both the user’s expressed privacy preferences and adaptive privacy reasoning of the framework. For instance, being at home with friends (private frame context) may trigger different masking behaviour than being in a public park (public frame context), especially if the intended exposure is social media. Such differences are modelled by the ontology to balance privacy risks and intelligibility across platforms.

Table 1 outlines the core entities within the ontology-driven framework.

Previous studies show that soft biometric features offer significant potential for user re-identification. Bari and Gavrilova [

60] state that users can be identified using gait biometrics with an 98.08% accuracy. Corbishley, Nixon and Carter [

61] identified that combining soft biometric features can increase the re-identification accuracy up to 88.1%, depending on the soft biometric features and the combinations used. Moctezuma, Conde, Diego and Cabello [

66] introduce a person identification method using only three soft biometrics features such as clothing, complexion and height to reach 85% identification rate. Additionally, the study explores how a recognition system using soft biometric features such as gender, backpack, jeans, and short hair achieves 53%-75% accuracy. This aligns with the findings by Sosa, Fierrez and Vera-Rodriguez [

62], who demonstrate that using a broader set of 73 soft biometrics can further improve re-identification accuracy, reaching 85.54%. Expanding on this, Corbishley, Nixon and Carter [

61], identified that when combining key features such as gender, height, skin tone, hair colour, hair type, age and so on, can result in re-identification of individuals and quantification of soft features (see

Table 2). For this work only the soft features with the highest-weighted are selected to improve the re-identifiability.

To support re-identification when face recognition is inconclusive, these soft biometric traits are analysed, to compute a Re-Identifiability Index (RII). If the RII score exceeds a defined threshold, the framework associates user with previously stored privacy settings or if the score is not high enough for accurate identification but it is high enough to risk re-identification the privacy settings are automatically increased to obfuscate high risk soft biometric traits and protect against potential re-identification. This adaptive mechanism aligns with Contextual Integrity by updating privacy to contextual norms rather than static rules, ensuring that privacy decisions are context-aware, personalised, and explainable. Accordingly, privacy enforcement dynamically reflects both frame context (scene, user activity, companions) and exposure context (where and to whom the content is visible).

Table 3 defines the key relationships within this ontology framework that enable explainable and context-sensitive privacy decisions.

Ontology-driven privacy enforcement rules follow a hierarchical sensitivity model, where the highest-sensitivity element detected (e.g., scene, object, action, emotion) in a frame determines the final privacy level applied. Additionally, user-defined red lines such as specific features, objects, logos, or individuals that must always be masked, are enforced independently of contextual sensitivity, ensuring that user-specified constraints override general framework predictions when necessary. When users choose to be on Auto Privacy mode, it uses prior user privacy configurations and contextual cues to train a supervised learning model (Random Forest), which dynamically predicts and applies optimal privacy settings in future frames. The resulting privacy enforcement mechanism combines hierarchical sensitivity reasoning with the absolute enforcement of user-defined red lines, ensuring both adaptive flexibility and strict user control.

Table 4 summarises the privacy actions applied under different user settings and contextual conditions.

This adaptive and explainable model enables privacy enforcement that is both personalised and scalable. It addresses long-standing gaps in privacy mechanisms, as noted by Halvatzaras and Williams [

15] and Laak, Litjens and Ciompi [

69], who emphasise the importance of adaptable privacy models that respond to changing user and environmental contexts. It also addresses concerns raised by Olejnik, Dacosta, Machado and Huguenin [

2] regarding the lack of effective privacy mechanisms in AI systems.

In addition to adaptive privacy levels, the framework supports user-defined red lines, elements that must be obfuscated in all contexts, regardless of privacy level, scene sensitivity, or intelligibility trade-offs. These may include highly personal or identifying traits such as certain objects, clothing styles, hats, bags or logos on clothing. During registration or privacy configuration, users are prompted to mark such features, which are stored in their user profile and always masked whenever detected. This ensures that the framework never compromises on non-negotiable privacy protections, even when balancing against intelligibility requirements or low privacy settings. These red lines are enforced at the final stage of the privacy pipeline, overriding all other contextual decisions. Also, when the Re-Identifiability Index (RII) exceeds a predefined threshold, the framework triggers obfuscation of soft biometric features, even if facial recognition is unavailable or the base privacy level is lower.

By integrating user-defined preferences, contextual cues, and soft biometric risk scores, the framework balances intelligibility and privacy, delivering a robust and GDPR-compliant framework for real-time privacy protection.

3.3. Multi-User Privacy Protection

Current privacy models produce ineffective results by neglecting dynamic privacy requirements between multiple users who share video streams, use smart homes, and in public surveillance systems, where multiple individuals may have diverse privacy preferences. Research by Ren, Lee and Ryoo [

7] highlights that current privacy systems enforce static privacy configurations, for all users without considering individual privacy requirements. Similarly, Olejnik, Dacosta, Machado and Huguenin [

2], and Sezer, Dogdu and Ozbayoglu [

11], identified a lack of adaptive mechanisms that prioritise privacy-sensitive users, contextual sensitivity, and usability considerations, while preserving framework usability.

To address these gaps, the proposed framework integrates real-time multi-user privacy enforcement that dynamically adjusts privacy settings for each detected user. It evaluates three primary factors: user-defined privacy preferences (e.g., Auto Privacy, High Privacy, Medium Privacy, Low Privacy, or No Privacy), contextual sensitivity of the detected entities (objects, actions and emotions), the presence of soft biometric traits that may lead to re-identification. When multiple users appear on the same frame, framework prioritises the highest privacy level for shared scene elements, while still applying individualised obfuscation to each person. For example, if User A opts for High Privacy while User B selects No Privacy, shared sensitive objects will all be obfuscated, but User B’s face will remain unobscured, which ensures a balance between collective protection and personal choice.

The ontology-driven rule engine resolves conflicts between users using a hierarchical model and user-specific red lines, such as “always hide logos” or “always hide certain objects”, that override contextual conflicts. Additionally, when a user is not directly recognised (e.g., face is occluded), the framework applies fallback privacy prediction based on soft biometric features and the Re-Identifiability Index (RII). In Auto Privacy mode, privacy settings are predicted using a supervised model trained on user historical data and contextual cues, that ensures users remain protected even when identity is ambiguous.

This detailed and user-centric framework is important for maintaining privacy protection across frames, that supports adaptive privacy in complex, multi-user scenarios and ensures compliance with user-defined privacy constraints, exposure contexts, and GDPR principles.

3.4. Person Re-Identification

In scenarios where facial recognition is not possible, due to occlusion, low resolution or user-defined masking, soft biometric traits are used as an alternative means for user re-identification and RII calculation. These traits include gait, hair type, skin tone, age, gender, and clothing/accessory cues, all of which provide varying degrees of identifiability. As Dantcheva, Elia and Ross [

64] highlights, a single soft biometric trait would not be unique enough to identify a subject, but their combination can significantly increase the probability of identity inference [

65,

66]. Dantcheva, Elia and Ross [

64] further discuss that every soft feature can carry information about different soft biometric trains, for instance hair type may implicitly indicate ethnicity or gender. To systematically evaluate the risk of re-identification, Dantcheva, Velardo and Dugelay [

65] proposes categorising each soft biometric feature into a distinctiveness level of Low, Medium or High and assign values 0.1 – 0.3, 0.4 – 0.7 and 0.8 – 1.0 respectively. These scores form the basis for quantifying the identifiability of a feature.

To address re-identifiability risks when using soft features, the proposed framework integrates two key components:

Re-Identifiability Index (RII) score that quantifies the cumulative re-identification risk of a user based on identified soft biometric features.

Intelligibility Value Index (IVI) measures the balance between obfuscation and the interpretability or information value of a given trait within the current frame and context.

IVI is not yet a formally standardised metric in existing literature, however it draws inspirations from several foundational works. Moctezuma, Conde, Diego and Cabello [

66] introduce a numbering points system for the list of features to calculate feature weights, while Bari and Gavrilova [

60] and Corbishley, Nixon and Carter [

61] quantified main soft biometric features based on their contribution to re-identification likelihood. Building upon these models, the proposed framework introduces the Intelligibility Value Index (IVI), which measures the proportion of scene interpretability retained after obfuscation of high-RII features. Each soft biometric feature is assigned an interpretability weight reflecting its contribution to overall scene understanding. After obfuscation, the retained weights are summed and normalised by the total interpretability weight, that results in an IVI score between 0 and 1.

IVI Score = Retained Interpretability Weight / Total Interpretability Weight (1)

A higher IVI indicates that obfuscation has minimally impacted the ability to interpret the scene, whereas a lower IVI signals substantial loss of semantic content. Importantly, IVI is evaluative and does not drive obfuscation decisions directly but provides a quantitative measure of the framework effectiveness in preserving scene intelligibility while enforcing privacy.

Table 5.

IVI evaluation for a single frame with retained interpretability after obfuscation of high-RII features.

Table 5.

IVI evaluation for a single frame with retained interpretability after obfuscation of high-RII features.

| Feature |

RII (Re-identifiability) |

Interpretability Weight |

Obfuscated? |

IVI Contribution |

| Face |

0.95 |

0.45 |

Yes |

0.0 |

| Gait |

0.8 |

0.3 |

Yes |

0.0 |

| Hair Type |

0.02 |

0.03 |

No |

0.03 |

| Hair Colour |

0.03 |

0.02 |

No |

0.02 |

| Age |

0.08 |

0.05 |

No |

0.05 |

| Gender |

0.03 |

0.25 |

No |

0.25 |

| Bag |

0.01 |

0.1 |

No |

0.1 |

| Bag colour |

0.012 |

0.03 |

No |

0.03 |

| Bag logo |

0.022 |

0.02 |

No |

0.02 |

| Dress |

0.1 |

0.15 |

No |

0.15 |

| Dress colour |

0.015 |

0.05 |

No |

0.05 |

| Dress logo |

0.023 |

0.03 |

No |

0.03 |

| Hat |

0.1 |

0.2 |

No |

0.2 |

| Hat colour |

0.014 |

0.03 |

No |

0.03 |

| Hat logo |

0.02 |

0.02 |

No |

0.02 |

| Jacket |

0.1 |

0.15 |

No |

0.15 |

| Jacket colour |

0.015 |

0.03 |

No |

0.03 |

| Jacket logo |

0.024 |

0.02 |

No |

0.02 |

| Pants |

0.11 |

0.3 |

No |

0.3 |

| Pants colour |

0.02 |

0.03 |

No |

0.03 |

| Pants logo |

0.03 |

0.02 |

No |

0.02 |

| Shirt |

0.01 |

0.1 |

No |

0.1 |

| Shirt colour |

0.015 |

0.03 |

No |

0.03 |

| Shirt logo |

0.023 |

0.02 |

No |

0.02 |

| Shoes |

0.02 |

0.1 |

No |

0.1 |

| Shoes colour |

0.01 |

0.03 |

No |

0.03 |

| Shoes logo |

0.02 |

0.02 |

No |

0.02 |

| Shorts |

0.1 |

0.1 |

No |

0.1 |

| Shorts colour |

0.015 |

0.03 |

No |

0.03 |

| Shorts logo |

0.02 |

0.02 |

No |

0.02 |

| Skin tone |

0.02 |

0.02 |

No |

0.02 |

| Skirt |

0.1 |

0.1 |

No |

0.1 |

| Skirt colour |

0.015 |

0.03 |

No |

0.03 |

| Skirt logo |

0.02 |

0.02 |

No |

0.02 |

| Sunglasses |

0.012 |

0.1 |

No |

0.1 |

| COCO Object Types (e.g., person, vehicle, furniture, electronics) |

0.01 |

0.1–0.5 |

No |

0.1–0.5 |

| Combined Soft Biometrics (Face + Hair + Jacket) |

0.91 normalised |

0.63 |

Yes (only jacket) |

0.76 |

When face recognition fails, the framework activates fallback matching using soft biometric embeddings (gait, body shape, hair, clothing). If a user profile is identified, their privacy settings and red lines are used for obfuscation. If no match exists, RII scores are used to identify potential re-identification risk and enforce protective masking as needed.

This layered framework supports privacy continuity in real-time applications by combining deterministic rules, such as “always hide logos”, when a predefined threshold has been reached (e.g., RII > 0.3). By evaluating intelligibility against re-identifiability dynamically, the framework aligns with Nissenbaum’s Contextual Integrity theory, which ensures that exposure decisions respect user-defined preferences and context-dependent privacy risk.

3.5. Privacy Risks and Mitigation

The increasing accuracy of soft biometric-based re-identification presents significant privacy challenges in multi-user, real-time video processing systems. As demonstrated in prior research [

60,

62], soft features such as gait, skin tone, hair type and clothing can be used to identify individuals even when facial data is obscured. This raises concerns in shared settings, where individuals may not directly interact with the system but their data is collected without consent.

Soft biometric features, including gait patterns (with an accuracy up to 98.08% [

60]) or a combination of gender, hair type, skin tone, clothes and others (with an accuracy up to 88.1% [

61]), could enable re-identification of individuals. In scenarios where face recognition fails these features may still facilitate tracking, which violate user anonymity. This risk is increased in social media sharing or surveillance contexts, where exposure is less controlled.

To mitigate these risks, the proposed framework applies context-sensitive privacy masking mechanisms that dynamically adapt to predefined user privacy settings, the sensitivity of the context and the potential for re-identification. These include:

High-Risk Features such as soft biometric traits (e.g., gait, hair colour) are obfuscated in cases when the Re-Identifiability Index (RII) exceeds a defined threshold.

Hierarchical sensitivity enforcement to prioritise the most sensitive element in the frame, scene, object, action, or emotion and applies the strictest corresponding privacy level.

Independently of the context or prediction, user-defined red lines (e.g., tattoos, logos, or specific clothing items) are always obfuscated.

In shared settings, the proposed framework uses multi-user conflict resolution to identify the highest applicable privacy preference across users, which ensures that no individual’s privacy is compromised due to the lower preference of others.

The proposed framework complies with GDPR principles of data minimisation, privacy-by-design by default and security of processing. To comply with data minimisation, only essential data is collected, and sensitive elements are masked by default in high-risk contexts. To comply to privacy by design, it automatically applies privacy settings based on user preferences and contextual sensitivity without requiring manual intervention. Lastly, for security of processing, framework uses adaptive masking to ensure that even indirect identifiers (e.g., gait) are protected when re-identification risks are detected.

By combining contextual reasoning, soft biometric risk scoring and user-centric privacy settings and red lines, the proposed framework provides robust protection against re-identification, even in complex or multi-user scenarios. This ensures that the privacy of individuals is protected not only through face masking, but also by mitigating less obvious but equally important identification features.

3.6. Implementation Details

The proposed framework incorporates a modular architecture and ontology-driven reasoning to achieve dynamic, real-time, user-centric privacy protection across multimodal recognition tasks. It integrates state-of-the-art deep learning models for face, object, scene, action and emotion recognition, operating in parallel to extract semantic features from continuous video streams. These features are fed into a unified reasoning engine that evaluates user-defined red lines, contextual sensitivity and re-identifiability risk to determine the appropriate level of privacy protection per frame. The framework is optimised for GPU-accelerated processing and is designed to prioritise real-time performance, GDPR compliance and intelligibility preservation.

The framework begins by identifying users and their associated privacy settings, a crucial step for enabling personalised privacy enforcement. Multiple face recognition models were evaluated based on accuracy and computational efficiency to ensure robust and real-time performance. Among the evaluated models, listed in

Appendix A Table A.1, MTCNN was selected for its balance between processing speed of 16–99 FPS, recognition accuracy of 94.4% and its ability to run on the GPU.

Once user privacy settings are identified, scene classification is processed to assess scene sensitivity, such as private, semi-private or public. Comparative evaluation of CNN-based and region-based CNN models, as detailed under

Appendix A Table A.2, showed that AlexNet achieved the best balance between classification accuracy of approximately 85% and computational efficiency of up to 205 FPS, which making AlexNet model ideal for real-time data processing.

In considering the choice of most appropriate model for object recognition, speed and scalability were key. Two-stage detectors offered higher detection accuracy, but their latency proved excessive for real-time deployment. Based on model evaluation, detailed under

Appendix A Table A.3, YOLOv5 was selected based on recognition speed of approximately 140 FPS and sufficient accuracy, which enables effective object recognition in real time.

The action recognition module is responsible for identifying sensitive behaviours (e.g., brushing teeth) that may require stricter privacy enforcement. Of the architectures compared (Appendix Table A.4), SlowFast Networks were selected for their ability to distinguish both subtle and fast-paced actions at high frame rates (approximately 30–60 FPS) while maintaining strong recognition performance.

To adapt to emotional sensitivity, the emotion recognition component analyses user facial expressions and informs dynamic privacy settings. The EfficientNet model was chosen for its high processing speed of up to 155 FPS and competitive accuracy of 84.6%, as summarised in

Appendix A Table A.5.

Across all modules, model selection prioritised a balance between recognition precision and computational speed, ensuring real-time operation using GPU-accelerated hardware. Additional model performance metrics and evaluation criteria are detailed in

Appendix A (Tables A.1-A.5).

Privacy enforcement mechanisms automatically classify recognised entities using established privacy categories such as private, semi-private, and public. Sensitivity classification enables the framework to dynamically adjust privacy settings based on user defined privacy settings and contextual sensitivity. This framework ensures that the highest level of privacy settings is applied to each frame, maximising the protection of sensitive objects. To balance privacy protection with usability, the framework dynamically adjusts privacy settings based on the user predefined privacy setting, contextual classification of detected entities and user predefined red lines. In the cases where users are on Auto Privacy, the framework uses a machine learning model to continuously refine privacy recommendations based on past user interactions, scene attributes, and sensitivity levels. Additionally, after the extraction of multimodal features including scene, object, action, and emotion information, the framework evaluates soft biometric traits such as gait, clothing types and colours, clothing logos, hair type and colour, skin tone, gender and age. A Re-Identifiability Index (RII) is computed for each user based on these traits (as described in

Section 3.4), guiding dynamic soft feature obfuscation decisions to further enhance user privacy where needed.

Users have full control and can define and update their privacy preferences by way of the system interface. Machine learning models are then used to refine privacy recommendations by utilising past activities between the recognised entities to optimise settings for each recognised individual and scene. To support this process, the framework uses a dedicated database that stores recognised entities including face encodings, objects, scenes, actions, emotions and their corresponding sensitivity levels. This structured database functions as an important reference point for the recognition modules, enabling real-time, context-driven privacy adjustments based on live feedback.

To ensure best performance, the framework is implemented using PyTorch and TensorFlow with CUDA optimisation, enabling deployment on devices with limited resources. The framework is designed to scale effectively across various real-world applications to maintain high privacy protection without hindering usability.

A detailed comparison between the proposed framework and prior static, semi-dynamic and context-aware methods (including Atta [

8,

9,

10]) is provided in

Table 10 under

Section 4. This demonstrates the significant improvements achieved in adaptability, contextual reasoning, soft biometric protection and real-time performance.

The reasoning ability of the proposed framework is demonstrated through its capacity to balance privacy protection with scene intelligibility using an adaptive model based on IVI and RII scores. These metrics control real-time obfuscation decisions by considering user-defined red lines and contextual relevance of visual elements. Unlike prior works that rely on static rules, proposed framework dynamically adapts at runtime through a unified, ontology-driven reasoning engine that integrates multimodal recognition, including soft biometric recognition, re-identifiability analysis, and context classification. At each stage, the framework integrates predefined user red lines, such as “always hide logos” or “always hide item x”, which override other user predefined settings and RII scoring. This ensures GDPR-aligned, user-centric enforcement even in ambiguous contexts.

3.7. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

A series of tests were performed on the proposed privacy protection framework by utilising suitable datasets for each module (faces, objects, scenes, emotions, and actions) and each class label was categorised into privacy-sensitive categories. The framework processed real-time multimedia streams to evaluate its ability to adapt to different conditions such as different user requirements and privacy preferences.

The experimental setup included a NVIDIA RTX GPU, Intel i7 CPU and 32GB RAM, which ensured sufficient computational power for real-time processing. The framework was developed using Python, PyTorch, TensorFlow, and OpenCV, using their GPU-accelerated capabilities and optimised execution pipelines to ensure efficient real-time processing for face, object, scene, action and emotion recognition.

To ensure clarity of our experiments, the proposed framework parameters and model configurations are reported in

Table 6. These parameters govern the recognition modules, privacy thresholds, and obfuscation methods used during evaluation.

As shown in

Table 6, each component was tuned to balance accuracy and computational efficiency for real-time performance. Thresholds for RII and IVI were selected to maintain strong privacy protection while at the same time preserving scene intelligibility, and ensuring the framework operates effectively under diverse conditions.

To evaluate the adaptability of the privacy protection mechanisms, the framework was evaluated under various scenarios, including single-user and multi-user settings and variations in sensitivity, and different privacy levels, such as No Privacy, Low, Medium, High or Auto Privacy.

To analyse the balance between intelligibility and privacy protection,

Table 7, summarises the trade-offs between information value and re-identifiability risk across various features.

As shown in

Table 7, achieving a good balance between information value and privacy sensitivity is critical. To evaluate how well the proposed framework manages this balance in real-time conditions, quantitative and qualitative evaluation methods were used. Quantitatively, the Re-Identifiability Index (RII) was used to assess privacy risks associated with identified soft biometric traits, while computational latency and obfuscation effectiveness were measured to ensure real-time feasibility. Qualitative evaluation involved structured user studies to assess participant's perceived privacy protection, scene intelligibility of how understandable the scene is after obfuscation and overall usability.

Following prior work by Hasan, Shaffer, Crandall and Kapadia [

5], re-identification rates were adopted as a comparative benchmark to assess how well the framework prevents unintended identification. To ensure that privacy enforcement does not compromise usability, system performance was measured before and after privacy-preserving transformations were applied. Additionally, the evaluation included measuring the processing latency of the recognised entities, privacy settings, and necessary obfuscations for each frame to guarantee that privacy control remains effective and scalable in real-time.

The experimental setup provides a complete assessment of privacy enforcement techniques by maintaining a balance between privacy protection, recognition accuracy, computational performance, and user experience. The experimental findings highlight the trade-offs involved in dynamic, context-aware privacy adaptation and whether in fact, these trade-offs could apply to real-world multimodal AI systems.

Finally, a structured user study was conducted to assess perceived usability and privacy satisfaction. Participants rated their experience based on the ease of use, perceived privacy protection and overall responsiveness. The findings from this evaluation are presented and discussed in detail under

Section 4.

3.8. Ethical Considerations

The proposed framework complies with ethical principles as it prioritises user privacy, transparency, fairness and regulatory frameworks such as GDPR. Ensuring that privacy protection mechanisms align with legal and ethical standards is critical for responsible AI [

27] deployment. A key ethical consideration is user consent and control so that individuals can exercise their decision-making power regarding privacy preferences. Individuals are provided with granular control over their privacy settings, enabling them to adjust their privacy configurations at any time based on personal comfort and identified contexts. This user-centric framework aligns GDPR standards of empowering users and gaining their consent which helps create better user trust. Also, the framework enforces data minimisation by limiting data handling to privacy protection needs while avoiding the collection and storage of unnecessary personal information.

The Re-identification process uses soft biometric features, such as gait, hair type, clothing, skin tone, etc., to compute a Re-Identifiability Index (RII) score. Ethically, this raises concerns around transparency, profiling and potential discrimination, and to address these users are informed about such data processing and can opt for their soft biometrics not to be used. The RII is used to calculate the re-identifiability risk and if necessary, authenticate users when face recognition fails and its use follows strict data minimisation principles. All these mechanisms are designed in compliance with GDPR to promote fairness, explainability and user control. Ethical rules are also encoded within the framework ontology-driven reasoning engine, which dynamically enforces user red lines and exposure-aware constraints to ensure that privacy decisions respect both legal standards and individual moral boundaries.

Addressing fairness and bias mitigation is essential in multimodal AI privacy systems. Recognition models used to detect faces, objects, scenes, actions and emotion information along with datasets they are trained on, are evaluated to identify potential demographic bias. The training data is carefully selected and when necessary is updated to ensure a balanced representation across demographic groups, reduce bias in privacy protection mechanisms and operate equitably across all types of user groups.

Ethical design is a main principle of the proposed framework as it ensures a balanced integration of privacy protection, fairness, trust and regulatory compliance. To protect sensitive data captured from video streams, the framework uses encryption protocols that encrypt raw data and stores it in encrypted format. Access to the encrypted data is restricted to authorised users only or government representatives. Moreover, data stored on the database is restricted through strict access control mechanisms, where each user has access only to their personal data. This framework prevents unauthorised use or data exposure and is aligned with the GDPR data protection requirements. By integrating these ethical enforcements into its architecture, the framework represents a responsible, secure and user-centric model to develop multimodal AI privacy protection.

4. Results and Analysis

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed ontology-driven, user-centric privacy protection framework. The analysis draws on both quantitative and qualitative methods to assess its effectiveness across multiple dimensions, including privacy protection strength, visual intelligibility, computational performance and user satisfaction. Each subsection examines key outcomes from experiments and user studies conducted in diverse, real-world and simulated environments involving varying user types, scene contexts, and data sensitivities.

The evaluation framework is designed to test how well it balances privacy preservation with usability, particularly under dynamic and multi-user conditions. Central to this assessment are two core metrics developed in this work: the Re-Identifiability Index (RII), which estimates the risk of identifying individuals based on soft biometric traits, and the Intelligibility Value Index (IVI), which approximates how much semantic clarity is retained post-obfuscation. These metrics, alongside recognition accuracy, responsiveness and subjective user feedback, form the basis for determining the real-world applicability of the proposed framework.

4.1. Intelligibility vs. Re-Identifiability

Balancing intelligibility with privacy is a central challenge in privacy-preserving multimedia systems. The proposed framework addresses this challenge through the use of the Re-Identifiability Index (RII) and the Intelligibility Value Index (IVI), which quantify, respectively, the likelihood of a user being re-identified and the interpretability of visual content. These metrics are used to drive adaptive privacy decisions that respond to both contextual risk and usability needs. The evaluation demonstrates that while increased obfuscation improves privacy, it may compromise intelligibility, highlighting the necessity for intelligent trade-offs.

The IVI is approximated through a hybrid method that considers the number of semantic elements which are not obfuscated (e.g., objects, actions, body cues), object recognition confidence, and visual clarity post-obfuscation. While RII escalates privacy based on identifiability risk, IVI acts as a feedback mechanism to ensure that intelligibility is not unnecessarily degraded. This dynamic scoring enables fine-grained control over which elements are obfuscated, when, and why.

The evaluation confirms that feature-level privacy directives (e.g., "always hide hair" or "always hide logos") are consistently enforced, regardless of context. This reflects the strength of the ontology-based reasoning engine and user-defined red line policies, which override contextual inference to ensure that personal privacy boundaries are respected, even in low-risk or high-clarity environments.

To empirically illustrate the privacy–intelligibility trade-off,

Table 8 presents example scenarios with varying Re-Identifiability Index (RII) and Intelligibility Value Index (IVI) scores, system-inferred privacy levels, and their corresponding obfuscation strategies. The Intelligibility Score represents the approximate proportion of semantic content preserved after obfuscation. It is computed using a weighted combination of IVI, the presence and visibility of key visual features (e.g., faces, actions, objects), and their semantic weights, outlined in

Table 5. These scores reflect each the contribution of each feature to scene comprehension and viewer interpretation. The final score accounts for both what is obfuscated and how it is obfuscated (e.g., fully masked vs. semi-visible), enabling a meaningful estimation of retained intelligibility under varying privacy conditions.

In cases where an unregistered individual is captured in a public setting, the framework detects soft features and calculates a RII score. If the RII score passes the threshold, the framework automatically applies obfuscation to the individual’s face and associated soft features, even in the absence of predefined privacy preferences or user-defined red lines. This scenario highlights the GDPR-aligned default protection strategy and ensures that individuals without explicit consent or registration are still protected against potential re-identification risks.

In another scenario involving a registered user, a red line was set to “never show jacket”. The framework enforced selective obfuscation, masking only the user’s jacket while keeping the rest of the face and body visible. Although the RII was moderate (0.4), this user-defined rule took precedence over contextual inference, validating the ability of the framework to enforce user autonomy through red lines.

Compared to prior efforts, such as Hasan, Shaffer, Crandall and Kapadia [

5], who achieved only 5% object masking accuracy using cartoonisation and reported a 95% identifiability rate among users, proposed ontology-driven framework demonstrates a significant performance advantage. Across 7,410 evaluated frames, proposed framework achieved 77.8% privacy protection accuracy in real-time video streams. Although 22.2% of users were still able to recognise at least one individual, this identifiability was mainly attributed to low-resolution constraints (224×224 pixels) used for real-time processing efficiency.

Furthermore, unlike static masking techniques that apply uniform filters across content, the proposed ontology-driven framework dynamically adjusts privacy enforcement based on entity sensitivity, user-defined privacy settings and red lines, soft biometric recognition and RII and IVI trade-off scoring. This enables detailed, transparent and explainable privacy protection aligned with the principles of Contextual Integrity, as well as the accountability and data minimisation requirements of the GDPR. This ensures a more explainable, user-centric and effective privacy framework.

In conclusion, balancing intelligibility and re-identifiability requires more than just masking, it requires adaptive, context-aware enforcement that accounts for human perception, risk levels and ethical protection. By combining RII–IVI analytics, ontology-based privacy reasoning and user-driven preferences, the proposed framework offers a flexible, adaptive method to privacy in real-world multimedia settings.

4.2. Privacy Protection Effectiveness

The evaluations of proposed privacy-preserving methods included both user studies and quantitative evaluations to measure their effectiveness on data protection, alongside user convenience and framework transparency. The ontology-driven privacy protection, supported by user-defined red lines, ensures that personal preferences are always respected, regardless of contextual inference or predicted privacy level (see

Table 4). These red lines, such as “always hide hair” or “always hide logos”, override framework decisions and are enforced consistently across all frames. Results indicate that 77.8% of participants, were unable to recognise any individuals within obfuscated videos, while 22.2% of participants identified at least one user at any point in time on the obfuscated video as a result of the false negatives from the face recognition module. This demonstrates strong anonymisation capabilities of the framework, highlighting potential improvements in recognition reliability at the frame level, for entities such as objects, faces, clothing, and accessories that carry re-identifiability risk. The obfuscation techniques were rated highly effective, with 85.2% of participants describing them very effective and 14.8% rating them as somewhat effective. Regarding overall privacy protection, the framework received excellent results with 74.1% of participants displaying strong agreement, and 22.2% expressing agreement that the framework offered sufficient privacy protection, which further validates the robustness of privacy enforcement mechanisms.

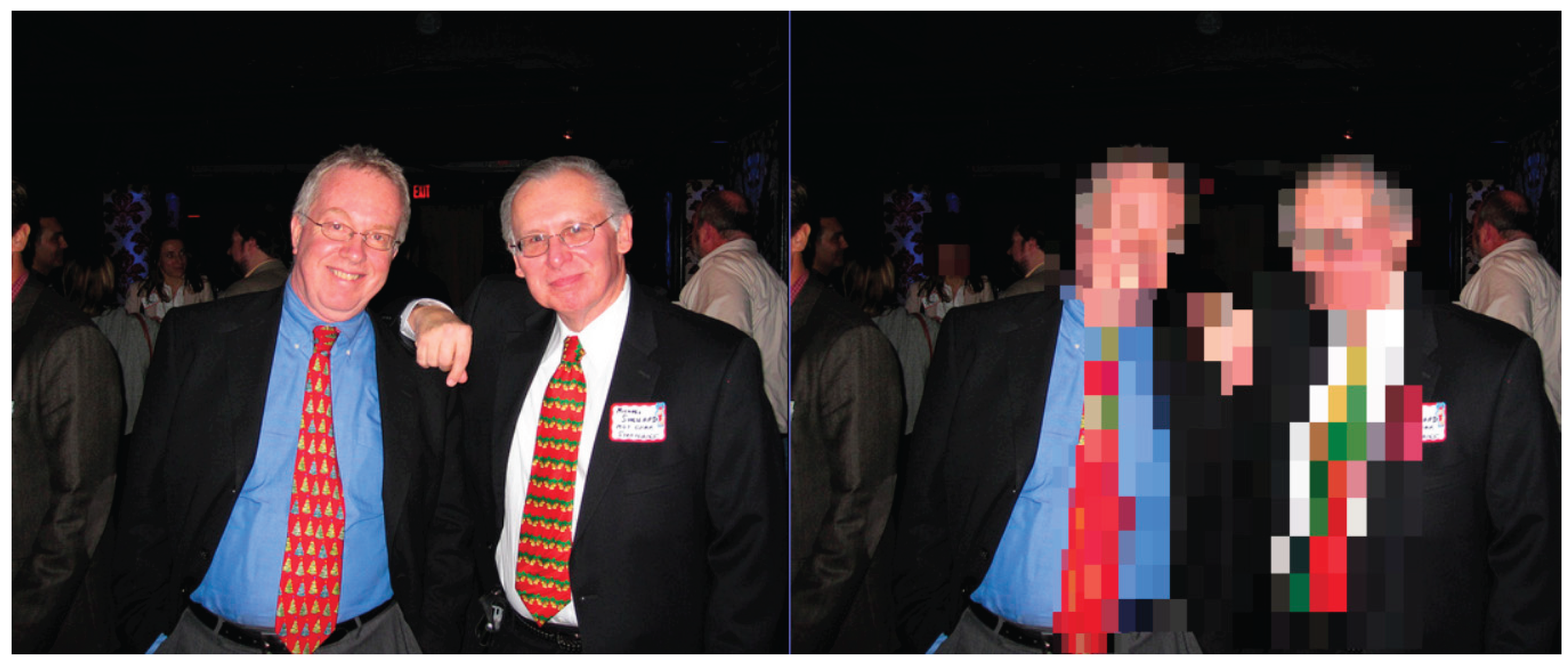

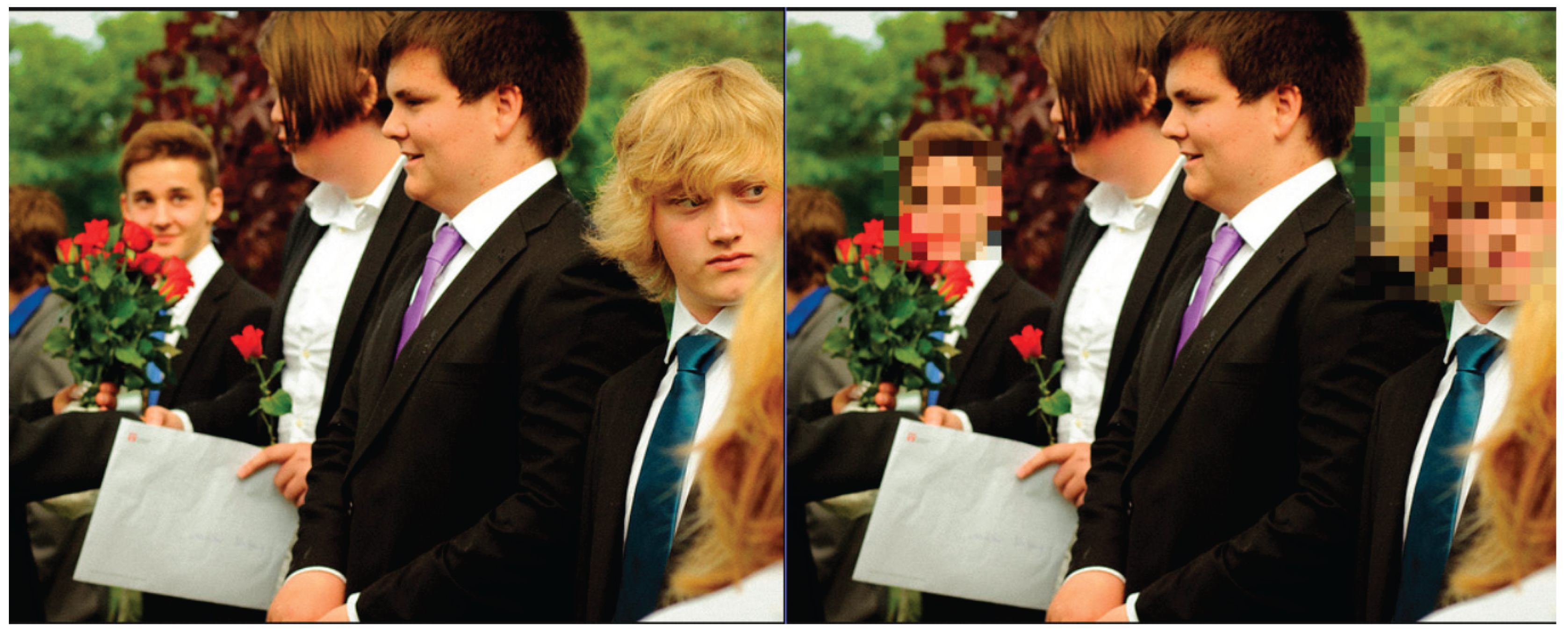

A key challenge in privacy-preserving AI systems is balancing privacy protection with usability. Nevertheless, users evaluated the proposed framework positively with results revealing that 71.4% of participants rated it positively balanced and 28.6% rated it as somewhat balanced in terms of privacy protection versus intelligibility. Notably, 34% of participants who observed the framework stated that the video clarity suffered a reduction, particularly at higher levels of privacy or when subjects appeared close-up as illustrated in

Figure 2. These results reinforce the need to optimise privacy-preserving techniques to maintain intelligibility while ensuring robust privacy protection.

Furthermore, user confidence in the data protection protocols was also high, where participants indicated “Very Confident” feelings in 53.6% of cases and “Confident” in 39.3% of cases when asked to rate data protection capabilities. Overall, user feedback confirms that the privacy protection control mechanisms, security protocols, and user-centric design of the framework are well received by users. To contextualise the effectiveness of the proposed method,

Table 10 compares its performance with state-of-the-art privacy-preserving techniques.

Table 9.

Comparison of Privacy Protection Methods.

Table 9.

Comparison of Privacy Protection Methods.

| Method |

Privacy Mechanism |

Anonymisation Accuracy |

Intelligibility Retained |

Re-identification Risk |

Real-time Capable |

| Hasan, Shaffer, Crandall and Kapadia [5] |

Cartoonisation |

5% (Object masking) |

High |

High |

No |

| Zhou, Pun and Tong [67] |

Face pixelation |

60% (Face only) |

Medium |

Moderate |

Partially |

| Proposed Framework |

Ontology + RII + Obfuscation |

77.8% |

Medium–High (60–85%) |

Low (RII-based masking) |

Yes |

In real-world evaluations, the framework demonstrated its adaptability across multi-user scenarios, including users with and without predefined privacy preferences. In one scenario, an unregistered user was detected in a video frame. Since no privacy level was assigned, the framework computed the Re-Identifiability Index (RII) using visual soft features such as hair colour, clothing and gait. As the RII exceeded the risk threshold, the framework automatically applied obfuscation to the user's face and soft biometric features, without any manual configuration. This validates the capacity of the framework to protect unidentified users in accordance with the GDPR principle of data protection by default.

In contrast, for registered users who specified red lines (e.g., “never show jacket”), the framework applied selective obfuscation only to the specified feature, in this case, the jacket, while leaving the rest of the frame unobscured. This showcases the detailed, user-respecting nature of the framework and its ability to distinguish between general privacy logic and user-enforced exceptions. This selective obfuscation results in minimal visual disruption, preserving full intelligibility of the user’s face and actions while respecting specific privacy directives.

This comparison highlights the robustness of the proposed framework, and its ability to dynamically adapt privacy protection levels based on context, user-defined constraints and re-identifiability risk. Unlike current static or face-only approaches, our framework protects multiple dimensions of identity, while maintaining reasonable intelligibility in most conditions.

To further demonstrate the robustness of the proposed framework,

Table 10 provides a comparative evaluation against current state-of-the-art privacy protection frameworks. This highlights the significant improvements introduced by our ontology-driven framework, in adaptability, contextual reasoning, and handling of soft biometric re-identification risk.

Table 10.

Comparative Evaluation of current Data Protection Methods and the Proposed Ontology-Driven Framework.

Table 10.

Comparative Evaluation of current Data Protection Methods and the Proposed Ontology-Driven Framework.

| Feature/Aspect |

Static data protection [4,5,7,67,68] |

Partially dynamic protection [3] |

Context-Aware Privacy Filters [8,9,10] |

Proposed Ontology-Driven Privacy Framework |

| Context-Awareness |

No |

Partial (fixed rules) |

Medium (scene elements) |

Full (scene, exposure, user settings) |

| Adaptability to User Preferences |

No |

Limited (static settings) |

No |

High (dynamic + user-defined red lines) |

| Privacy Adaptation (Sensitivity) |

Low |

Medium |

Medium (face, skin and body) |