1. Introduction

In recent years, surveillance has evolved into a critical necessity for safeguarding both lives and assets across various sectors. The growing complexity of security threats, from theft and vandalism to terrorism and cybercrime, has driven the demand for more advanced surveillance systems [

1,

2]. These systems are increasingly deployed in public spaces, private properties, industrial zones, and government facilities to ensure safety and security.

The integration mobile robots into surveillance systems [

3,

4], offers a highly flexible and cost-effective solution to enhance safety across various sectors, including industries, the military and home automation. These robots can effectively replace humans in hazardous environments or risky manufacturing processes, minimizing the need for human intervention in dangerous conditions. Their ability to navigate autonomously and perform tasks in real time makes them a valuable asset in ensuring security and safety while reducing operational costs.

Intelligent security robots [

5,

6] are equipped with cameras and a variety of sensors that allow them to continuously monitor an area with minimal human oversight. They can detect intrusions or issues and alert surveillance personnel in real time with high reliability. Subsequently, surveillance mobile robots have become a significant focus of research, given their potential to enhance security and operational efficiency.

Surveillance technologies have significantly advanced with the integration of modern innovations such as artificial intelligence (AI), computer vision (CV), and the Internet of Things (IoT). These technologies enable real-time monitoring, anomaly detection, and automated responses, making surveillance systems more efficient and reliable. For instance, face recognition, behavior analysis, and motion detection are now commonplace in modern surveillance, allowing for early detection of potential threats.

Recently, the need for secure identification methods has become increasingly crucial. Traditional methods such as passwords and PIN codes are no longer enough to protect sensitive information and secure access to restricted areas [

7,

8,

9]. This has led to the rise of biometric technology, which uses unique physical or behavioral characteristics to verify an individual’s identity. In recent years, many security structures have started implementing biometric systems based on iris, fingerprint [

8], voice, and face recognition [

10].

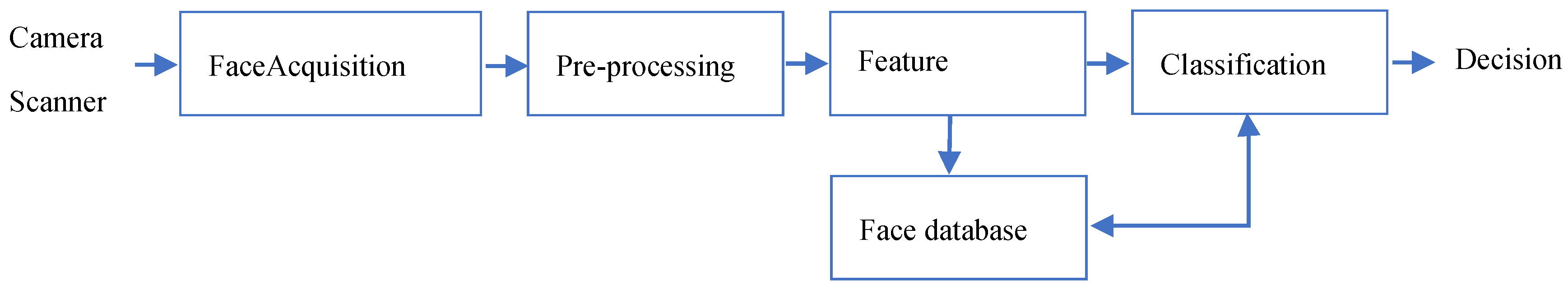

Due to the diverse structures and features present in the human face, it has emerged in recent years as one of the most widely employed biometric authentication systems in various applications and domains [

7,

8,

9]. However, a robust face recognition system [

10] is developed using three fundamental steps: face detection, feature extraction, and face matching/classification. The process of face detection begins by locating and identifying the human face. The feature extraction step is a critical aspect of the recognition process, responsible for extracting feature vectors for any human face identified in the initial stage. Moreover, successful feature extraction plays a pivotal role in determining the success of subsequent steps. Finally, the face recognition step conducts matching or classification of image features according to predefined criteria and is then compared against all template face databases to establish the identity of a human face.

Figure 1 depicts the main components of a typical face recognition system.

Face recognition is a technique used to authenticate or identify individuals by automatically recognizing them based on their facial characteristics. It involves a computer program that can automatically detect or confirm one or more individuals from a digital image or a video frame extracted from a video source. In verification situations, the similarity between two facial images is evaluated, and a decision is made regarding whether they match or not. However, the process of identifying the identity of an unknown facial image from a database of recognized faces is referred to as face recognition. In this scenario, the system computes the similarity between a particular facial image and all facial images stored in a large database, returning the best match as the presumed identity of the person.

In this context, many authors have examined the issue of face recognition by employing diverse techniques [

5,

6], and many authors and researchers have extensively discussed the challenges and advantages of these hybrid approaches in the context of face recognition [

11]. They have explored how combining different techniques can enhance performance under various conditions such as varying lighting conditions, pose variations, occlusions, and facial expressions [

7,

8,

9].

The Internet of Things (IoT) is a recent advancement in surveillance technology designed to bolster security and provide personalized protection. This innovative approach involves integrating a wide range of physical devices—such as cameras, sensors, and alarms into a network connected to the internet. These interconnected devices can communicate with one another and with centralized systems to collect, analyze, and share data in real-time. The advantages of IoT in surveillance extend beyond basic functionalities, offering a range of benefits such as Fast Operation, Automation and Control, Easy Access to Information and Saving Money that enhance overall security and operational efficiency. Overall, the integration of IoT into surveillance systems provides a more dynamic, efficient, and cost-effective approach to security, enhancing both the functionality and economic viability of these systems. However, the integration of face recognition technology with IoT is essential to significantly enhance the effectiveness of surveillance robots and develop more efficient rapid response systems.

In this paper, a prototype of a cost-effective mobile surveillance robot is proposed. The robot’s intelligent security system is controlled by the Raspberry Pi 4 Model B, known for its advanced computing capabilities. Compared to earlier Raspberry Pi models or other microcontrollers such as the Arduino Uno/Mega, the Raspberry Pi 4 Model B delivers significantly improved processing power. This high-performance processor enhances the robot’s capabilities and overall effectiveness in surveillance tasks.

The proposed surveillance robot is outfitted with a PIR (Passive Infrared) sensor and a USB camera to detect the presence of intruders within a designated area. By integrating IoT and face recognition technology, the robot can not only monitor the environment but also identify and track individuals, enhancing its ability to provide accurate and timely security responses. This combination of sensors and intelligent technology allows for efficient surveillance, making it a powerful tool in detecting unauthorized access.

When the PIR (Passive Infrared) sensor detects the presence of a person, the system automatically activates the camera to capture live streaming video and photos. These recordings are then transmitted to the control room through IoT technology, allowing real-time monitoring and analysis of the situation. This automated process ensures that any potential security breach is promptly captured and relayed, enabling quick responses from security personnel.

Face recognition technology based on high-order statistical features and evidence theory is employed to differentiate between known individuals and potential intruders. The proposed method comprises two distinct steps aimed at enhancing recognition accuracy and robustness. Firstly, high-order statistical features are extracted from facial images to capture complex patterns and variations inherent in facial data. Subsequently, evidence theory is employed to integrate these features, providing a comprehensive and reliable basis for face recognition. Hence, this work may be seen as a straightforward additional improvement of the issues proposed by Ben Chaabane et al. [

12]. By analyzing and comparing facial features with a pre-existing database, the system can quickly identify authorized personnel while detecting unfamiliar or unauthorized persons. This capability enhances security by allowing more precise monitoring and reducing false alarms, ensuring that only genuine threats trigger a response.

In addition, when an unknown individual is detected, the system immediately sends an email containing the captured image along with an alert notification to the control room via IoT. Furthermore, a web interface has been developed to receive this data and allows for remote control of the robot’s movements over a Wi-Fi connection. This interface provides operators with the ability to monitor the situation in real-time and manually adjust the robot’s position if necessary, enhancing both security and operational flexibility.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section (2) details the proposed robot surveillance system. Section (3) discusses the experimental results, and Section (4) provides the conclusion.

2. The Proposed Robot Surveillance System

The proposed surveillance system is designed to carry out high-risk tasks in environments where it would be unsafe or impractical for humans to operate. By leveraging advanced technology, such as automated drones, AI-powered cameras, or remote-controlled robots, the system can monitor and respond to potential threats or hazardous situations in real-time, making it ideal for use in environments like disaster zones, conflict areas, or high-security facilities. This reduces the need for human involvement in potentially life-threatening conditions, while ensuring continuous and efficient surveillance.

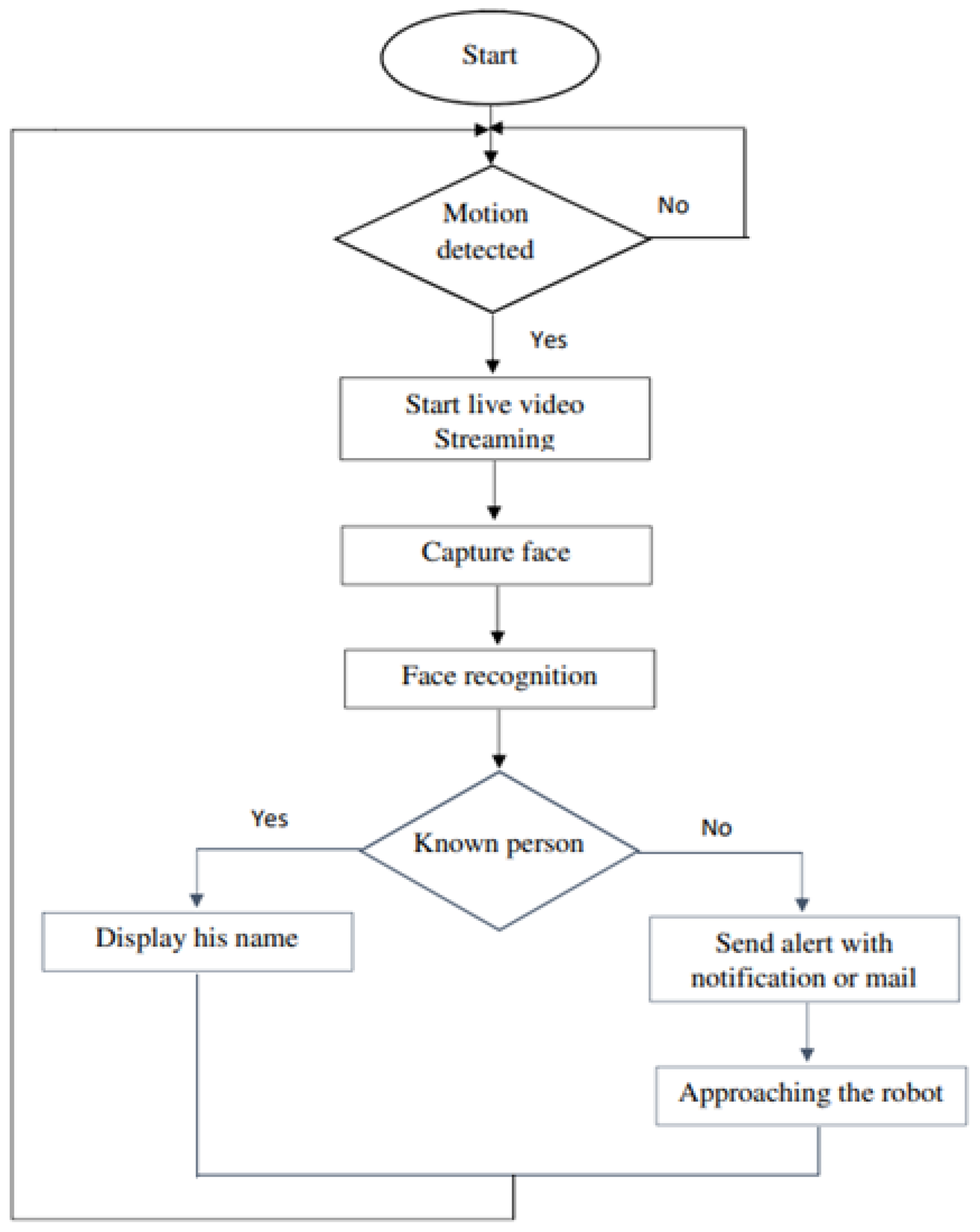

In this context, we propose a prototype of a low-cost mobile surveillance robot based on the Raspberry PI 4, which can be integrated into any industrial environment. This intelligent robot detects the presence of intruders using IoT and face recognition technology, providing a reliable and automated security solution. The flowchart of the surveillance robot is shown in

Figure 2.

The system is equipped with a passive infrared (PIR) sensor and a camera, used to capture real-time streaming video and images. These recordings are instantly transmitted to the control room through an IoT network for continuous monitoring.

When the PIR sensor detects the presence of a person, regardless of whether the individual is recognized or registered in the system’s database, the robot automatically activates live-streaming mode and begins capturing photos. This allows for immediate visual data collection, enabling swift response and detailed analysis of potential security breaches or intrusions.

Using the proposed face recognition algorithm, the system can accurately analyze and identify faces by comparing the captured images with the facial data stored in its database.

If the facial features match a stored profile, the system recognizes the person as authorized or familiar. If no match is found, the system classifies the individual as unknown or potentially unauthorized. This real-time comparison enables the system to quickly distinguish between familiar faces and possible intruders, improving the overall security and response time of the surveillance system. Additionally, the system can log interactions with both known and unknown individuals, providing a historical record for future reference or investigation.

If a person is detected as an intruder, the system instantly sends a notification to the control room, alerting security personnel of the potential breach. Additionally, the system can send an email with the intruder’s photo attached, providing visual evidence for further action. In cases where the detected individual is a known person, the system will include their name in the notification, ensuring clarity and a quick response. This dual alert mechanism—both real-time notification and email—helps streamline the process of identifying and addressing unauthorized access.

Additionally, a web application has been developed to allow remote control of the robot, enabling it to approach individuals for better visibility and capture high-quality pictures and videos. Through this application, operators can maneuver the robot to obtain a closer view or focus on specific areas of interest. It’s also worth noting that the robot has the flexibility to function as a stationary surveillance system if needed, offering both mobile and fixed monitoring capabilities. This versatility enhances the robot’s effectiveness in various surveillance scenarios, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the area.

2.1. Face Detection by Dlib

There are two widely used methods for face detection. The first utilizes the haar-like feature combined with an AdaBoost classifier, proposed by Viola and Jones [

13]. The second method is based on the HOG (Histogram of Oriented Gradients) and SVM (Support Vector Machine) classifier, introduced by Dalal and Triggs [

14].

In the literature [

15], a comparison of face detection results is presented between the Viola-Jones algorithm implemented using OpenCV [

16] and the HOG algorithm implemented with Dlib [

17].

The results demonstrate that for frontal face detection, the performance of the Dlib algorithm significantly outperforms the OpenCV implementation of the Viola-Jones algorithm. Dlib’s use of HOG features and an SVM classifier provides greater accuracy and reliability in detecting frontal faces compared to OpenCV’s traditional haar-like features and AdaBoost classifier. This makes Dlib more effective for precise frontal face recognition tasks. For side face detection, while both Dlib and OpenCV have limited capabilities and exhibit poor overall performance, the Dlib algorithm still produces superior detection results compared to OpenCV. Despite the inherent challenges of accurately detecting side faces, Dlib’s HOG and SVM-based approach manages to outperform OpenCV’s Viola-Jones algorithm, showing better detection accuracy in these situations. Based on the comparison outlined above, the Dlib algorithm is chosen for implementation. Its superior performance, particularly in detecting frontal faces, and its ability to outperform the OpenCV Viola-Jones algorithm in both frontal and side face detection, make it a more effective solution for this application. Therefore, Dlib’s face detection algorithm is adopted for enhanced accuracy and reliability. The images in the ORL dataset [

18] are tested, and an illustrative example of face detection and Isolation is presented in

Figure 3.

Among the total 400 images in the dataset, two facial images were unable to be detected by the face detection algorithms, resulting in a successful detection face of 398 images. The subsequent experimental results and analyses are based exclusively on these 398 successfully detected images. This indicates a high level of accuracy and reliability in the face detection process, allowing for a robust evaluation of the performance of the employed algorithm. After face detection, face recognition algorithm is implemented in order to distinguish between company personnel and intruders.

2.2. Face Recognition with High-Order Statistical Features and Evidence Theory

Face recognition involves identifying individuals based on their facial features. It encompasses two distinct approaches: biometric identification, which utilizes physical traits for recognition, and behavioral analysis, which assesses actions to verify identity claims. Although both methods have historical use, contemporary practices predominantly favor biometric identification for facial recognition purposes.

Facial recognition is a significant challenge due to the vast volumes of available datasets and various complicating factors. These include facial expressions, lighting conditions, and the presence of accessories like glasses or scarves, which can lead to partial occlusion, further complicating the process.

The objective of a face recognition algorithm is to determine whether two faces are of the same individual or not [

19]. Typically, such algorithms consist of three key stages: pre-processing, feature representation, and classifier training. During pre-processing, input images are standardized, noise is eliminated, and essential operations are carried out. The feature representation stage involves extracting relevant features from the images, while the classifier training stage entails training a model based on these extracted features.

The face recognition method proposed in this paper is conceptually different and explores new strategies. The proposed method does not rely on established methods but rather investigates the benefits of integrating various approaches.

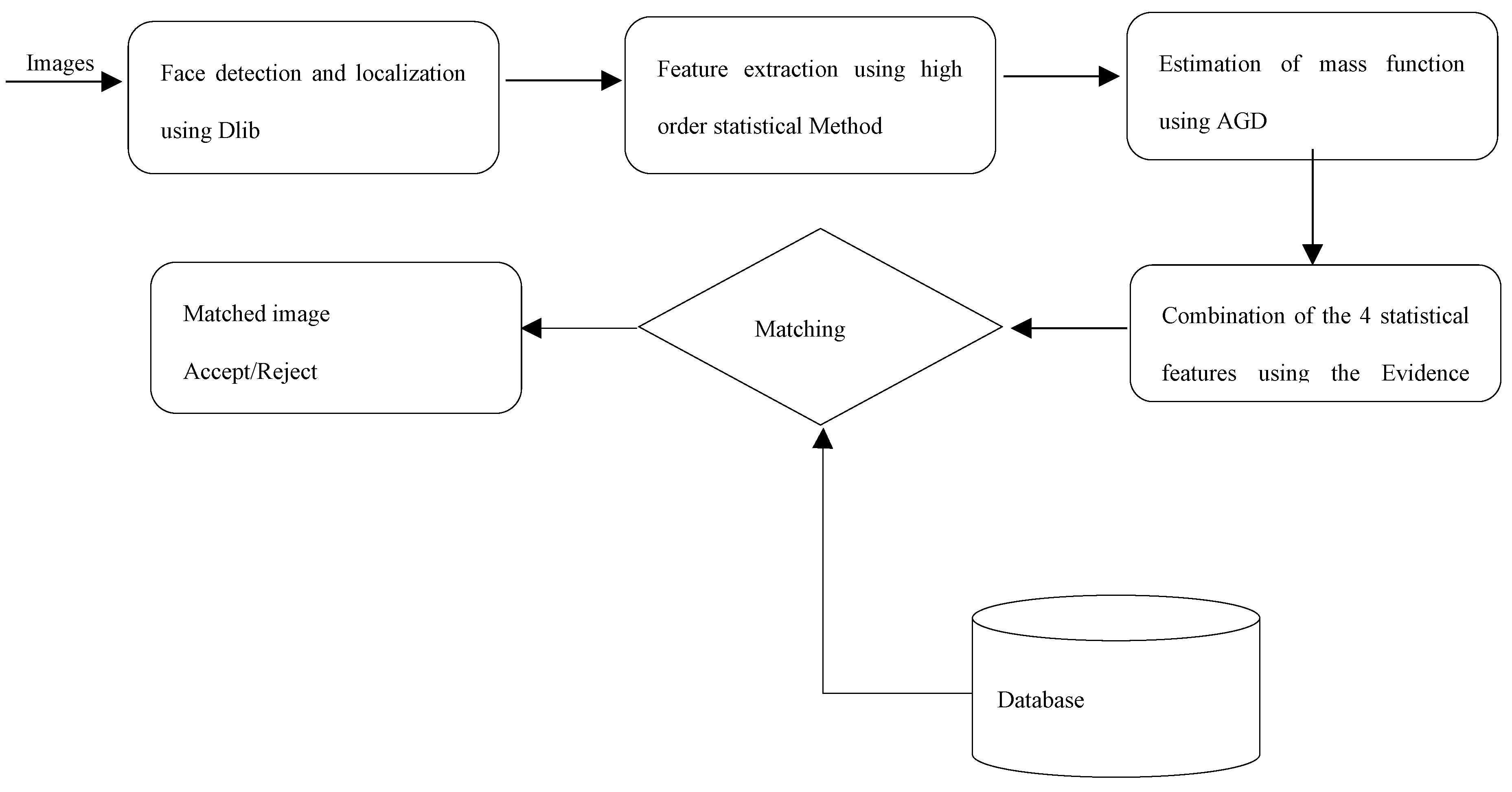

The proposed method for face recognition is based on high-order statistical features and evidence theory [

20]. In the first phase, the statistical features selection approach is applied to each image in order to select the features based on relevance and redundancy characteristics and to construct the attribute images, whereas the evidence theory is used to merge the different information sources. By integrating multiple information sources, each with its reliability, the proposed method can make more informed decisions in face identification tasks.

Significantly, the proposed face recognition method is structured into two phases. Initially, statistical features are derived from the original images to generate a new image termed as the attribute image [

21]. Subsequently, during the second phase, the estimation of the mass functions algorithm [

22] and the application of evidence combination and decision rules [

23,

24,

25] are employed to obtain face recognition results. The main components of the proposed face recognition system are depicted in the diagram illustrated in

Figure 4.

2.2.1. Feature Extraction

The process of feature extraction from face images is performed using the statistical method. These features capture complex patterns and relationships within the image data that may not be apparent with traditional methods. The idea is to replace the image by the feature extracted from the cooccurrence matrix. The co-occurrence matrix is a common tool in image processing and natural language processing to capture the spatial or relational information between elements in an image or text. From this matrix, various statistical features can be extracted to characterize the relationships between elements. Some common statistical features include:

Mean: the average value of all the elements in the matrix. It provides a measure of the central tendency of co-occurrence relationships.

Variance: Measures the dispersion of values around the mean. Higher variance indicates greater variability in the relationships between elements.

Where and are respectively the size of co-occurrence matrix and the value at the (i,)th position in the co-occurrence matrix.

Standard Deviation: The square root of the variance. It quantifies the amount of variation or dispersion present in the co-occurrence relationships.

Entropy: Represents the amount of information or uncertainty in the co-occurrence matrix. Higher entropy indicates greater randomness or disorder in the relationships between elements.

Log denotes the natural logarithm.

Energy: Also known as uniformity or angular second moment, it measures the sum of squared elements in the co-occurrence matrix. High energy indicates a high degree of homogeneity in the relationships.

Contrast: Measures the intensity contrast between neighboring elements in the co-occurrence matrix. High contrast values indicate large intensity differences, while low contrast values indicate similar intensities.

Correlation: Measures the linear dependency between pairs of elements in the co-occurrence matrix. It indicates how much one element is related to another. Positive values denote positively correlated elements, negative values denote negatively correlated elements, and zero indicates no correlation.

Homogeneity: Reflects the closeness of the distribution of elements in the co-occurrence matrix to the diagonal. Higher homogeneity values indicate that the elements are concentrated along the diagonal, implying a high degree of uniformity in the relationships.

These are just a few examples of statistical features that can be derived from co-occurrence matrices. The choice of features depends on the specific application and the desired characterization of the relationships between elements. In this work, the features selection is based on their relevance and redundancy characteristics. Features that are relevant for distinguishing between different faces are identified and retained, while redundant or less informative features are discarded. This helps in reducing the dimensionality of the feature space and focusing on the most discriminative features. These statistical features serve as the basis for further analysis and processing in the face recognition task.

2.2.2. Use the Evidence Theory for Classification

The purpose of classification is to classify the images into different classes. The idea of using DS evidence theory for image classification is to integrate the information from multiple sources while considering the uncertainty associated with each piece of evidence. Initially, features are extracted from the input images using statistical methods. Each feature highlights specific characteristics of the original image. The DS evidence theory is then used to fuse the features extracted from the cooccurrence matrix. In DS theory, each piece of evidence (feature) is represented by a belief function, which assigns degrees of belief to different hypotheses (classes, i.e., faces). Finally, based on the combined belief function, a classification decision is made. This decision could involve assigning the image to one or more predefined classes, depending on the evidence provided by the features extracted from the cooccurrence matrix.

Dempster-Shafer Theory (DS) [

26,

27], also known as the theory of belief functions, provides a framework for reasoning with uncertain or incomplete information. Unlike traditional probability theory, DS theory allows for the representation of uncertainty more flexibly by assigning degrees of belief to sets rather than just single events.

In the present study, the frame of discernment

composed of

single mutually exclusive subsets

contains the the clusters or faces (

), which are symbolized by:

where:

.

In order to express a degree of confidence for each proposition A of

, it is possible to associate an elementary mass function

which indicates the degree of confidence that one can give to this proposition. Formally, this description of

can be represented with the following three equations:

can be represented with the following three equations:

The purpose of segmentation is to divide the image into uniform regions. The idea of using the evidence theory for image segmentation is to fuse one by one the features coming from the cooccurrence matrix of each image. The Gaussian distribution model [

28] is applied to the statistical features to be combined. Then, the mass functions are combined using the Dempster-Shafer (DS) combination theory to obtain the final segmentation results.

Masses of simple hypotheses

are derived based on the assumption that the attributes

for the class

follow a Gaussian distribution. For each hypothesis

, the probability density function (PDF) of the Gaussian distribution is used to describe the probability that a data point belongs to the class

. The formula for the mass function based on the Gaussian distribution for the class

is as follows:

Where:

is the mass of hypothesis , representing the likelihood that the attribute belongs to class i.

is the attribute value being evaluated.

is the mean of the Gaussian distribution for class .

is the variance of the Gaussian distribution for class .

The mass function assigned to double hypotheses (i.e., when there is uncertainty between two possible clusters) depends on the mass functions of each individual hypothesis. In the context of evidence theory, such as Dempster-Shafer theory, the mass function for a double hypothesis is derived by combining the masses of the individual hypotheses while accounting for the uncertainty between them.

Let’s denote two simple hypotheses as

and

. The mass function for the double hypothesis

, which represents the uncertainty that the attribute could belong to either class

or class

, can be expressed as:

Once the mass functions of the four attributes are estimated, their combination can be performed using Dempster’s rule of combination (also known as the orthogonal sum) from Dempster-Shafer theory. This rule is used to combine evidence from multiple sources to estimate the final belief or mass function. The orthogonal sum for combining two mass functions

and

is represented as follows:

Where:

is the combined mass function for hypothesis .

and are subsets of the frame of discernment (the possible hypotheses) such that their intersection is .

is the mass function for hypothesis from the first attribute, and is the mass function for hypothesis from the second attribute.

is the conflict term, which quantifies the conflict between the two mass functions and is given by:

represents the basic probability mass associated with conflict. This is determined by summing the products of mass functions of all sets where the intersection is an empty set.

In the DS combination theory [

29], the mass functions of the four attributes are fused together to generate a single value. After calculating the orthogonal sum of the mass functions for the four attributes, the decisional procedure for classification purpose consists in choosing one of the most likely hypotheses

. This is typically done by evaluating the final mass functions and identifying the hypothesis with the highest mass (i.e., the most supported hypothesis based on the combined evidence).

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

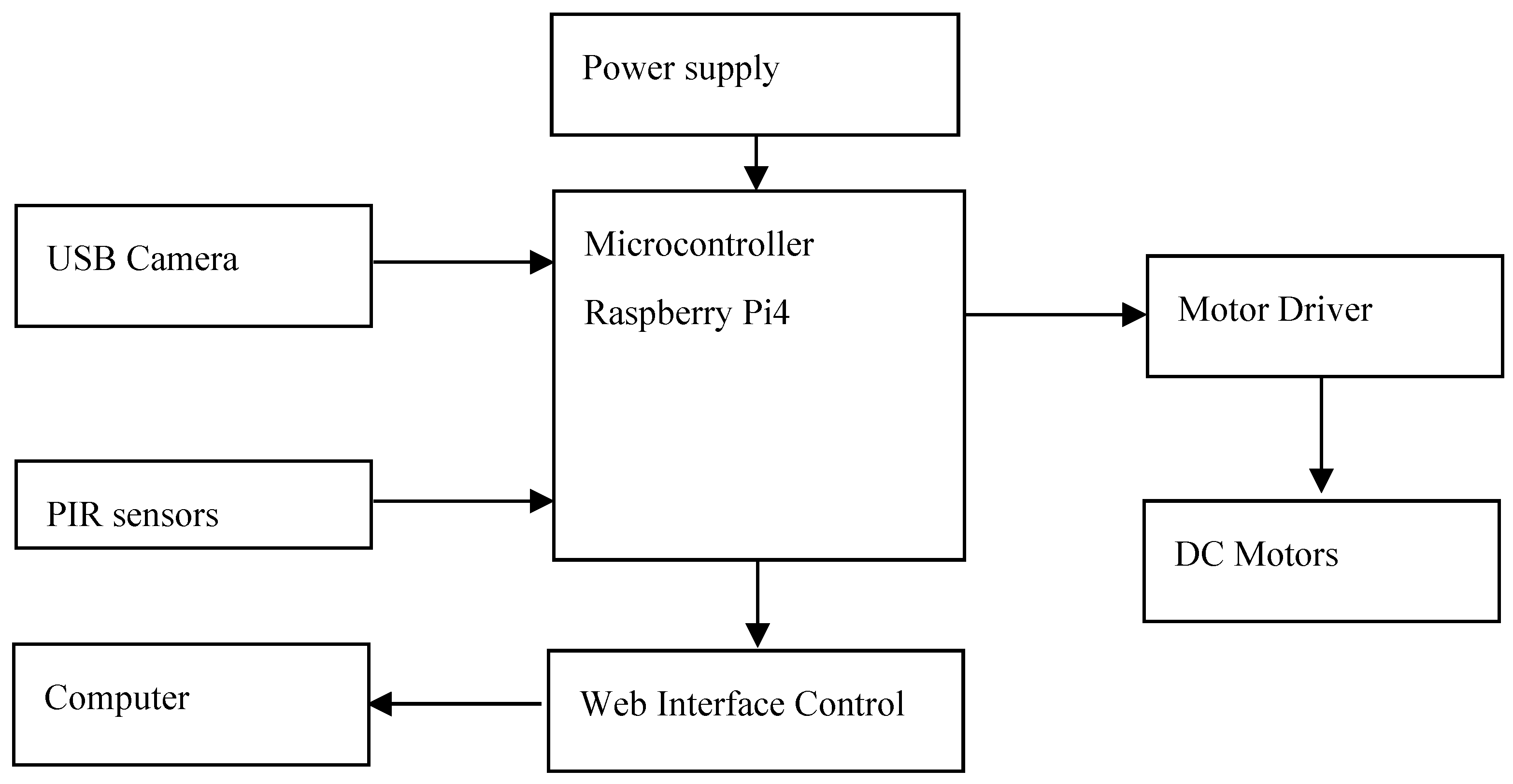

The electrical design of the robot is outlined, with a schematic diagram of the proposed system created using Fritzing software. The diagram of the robot system is given by the following

Figure 5, incorporates the following components:

4 Motors: Responsible for movement, controlled with the information transmitted by the sensors.

Dual H-Bridge Motor Driver L298N: typically used to control motor speed and rotation direction.

PIR Sensors: used to detect human motion with a sensitivity range of about 7 meters.

Raspberry Pi4: used to control the proposed intelligent security system.

USB camera: used to stream live video to a user at a remote location, enabling real-time monitoring. Additionally, the camera captures images of an intruder whenever motion is detected, enhancing the system’s security functionality.

Power Supply: Provides the necessary voltage and current to power the system. The motors are powered by a 12V battery, which delivers the necessary voltage to the motors through a motor driver, ensuring proper regulation and control of power. Additionally, a power bank is utilized to supply power to the Raspberry Pi, providing a stable and portable energy source for the microcontroller, allowing it to manage the system’s operations independently of the motor power supply.

Wiring and Connectors: Used to connect all components and ensure communication and power distribution.

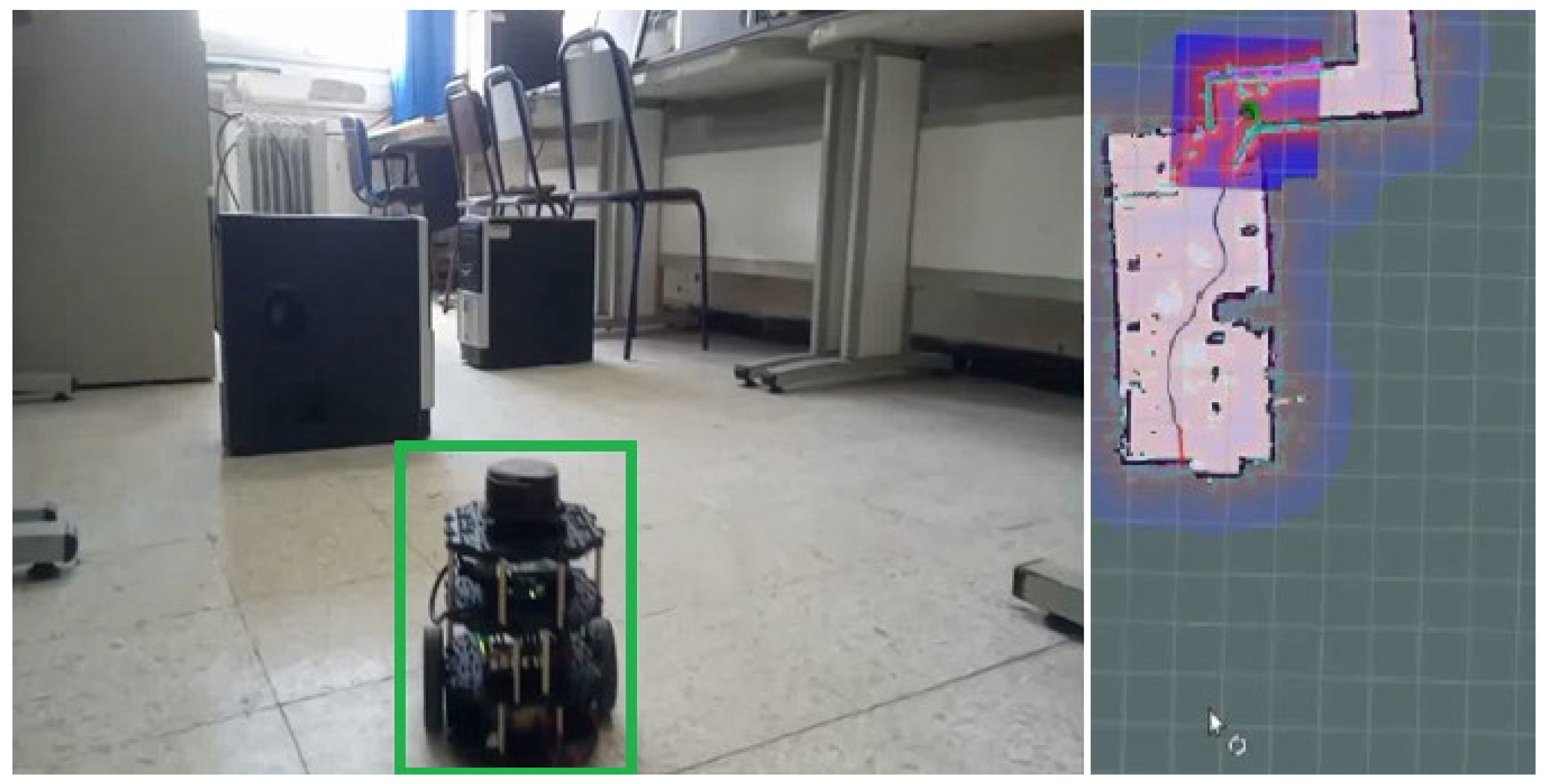

This schematic offers a clear visualization of how these components are integrated into the overall electrical system of the robot. The prototype of the surveillance robot is presented in

Figure 6.

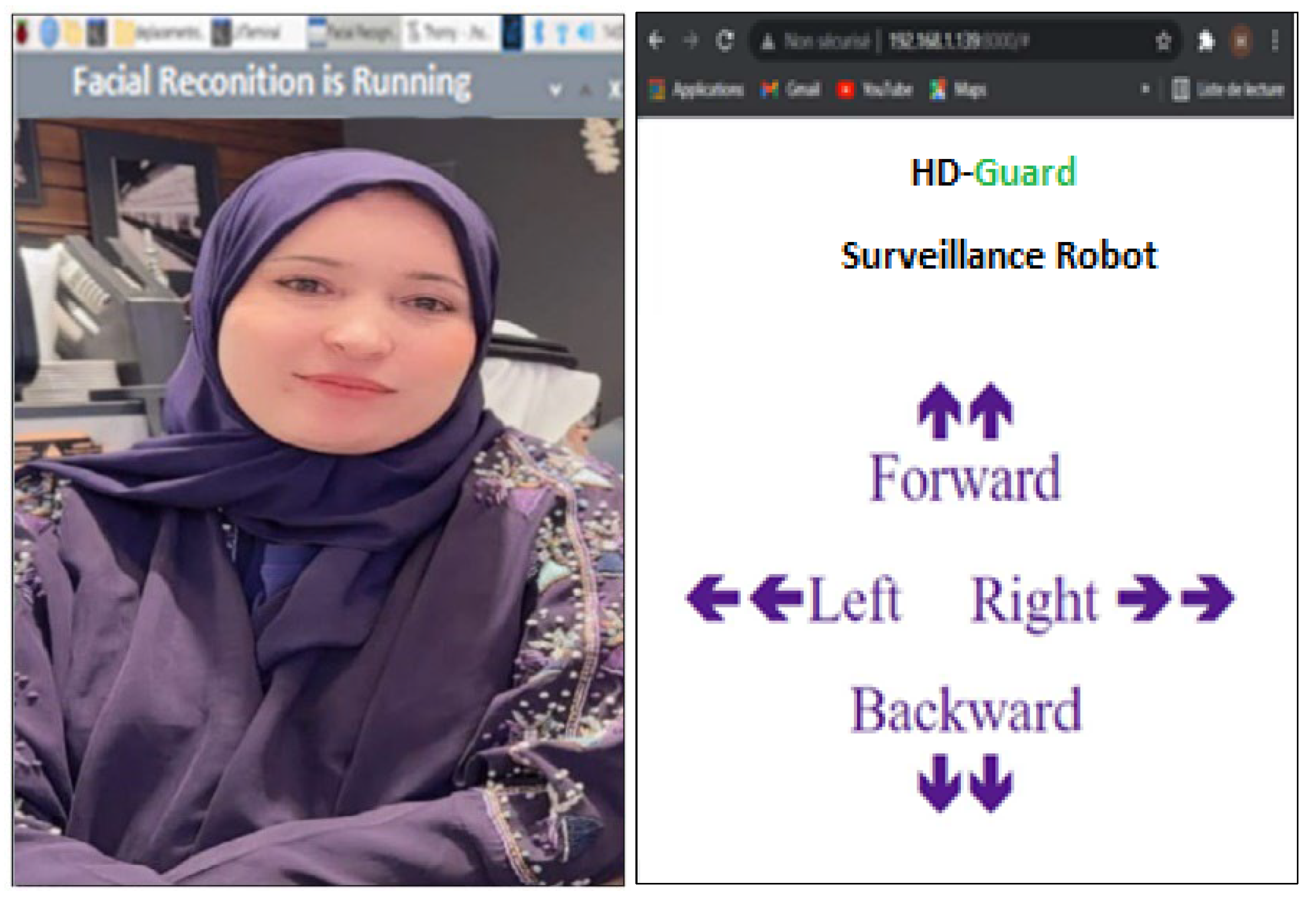

When the PIR (Passive Infrared) sensor detects human motion, the system activates a live video stream to monitor the scene. As the video stream starts, face recognition software is employed to analyze and verify the presence of any personal facial data. If the system identifies the individual as someone stored in its database, it cross-references the data and displays the person’s name on the screen.

Figure 7 represents the scenario in which a known individual is detected by the system. When the person is recognized, the system identifies them and displays her name on the screen.

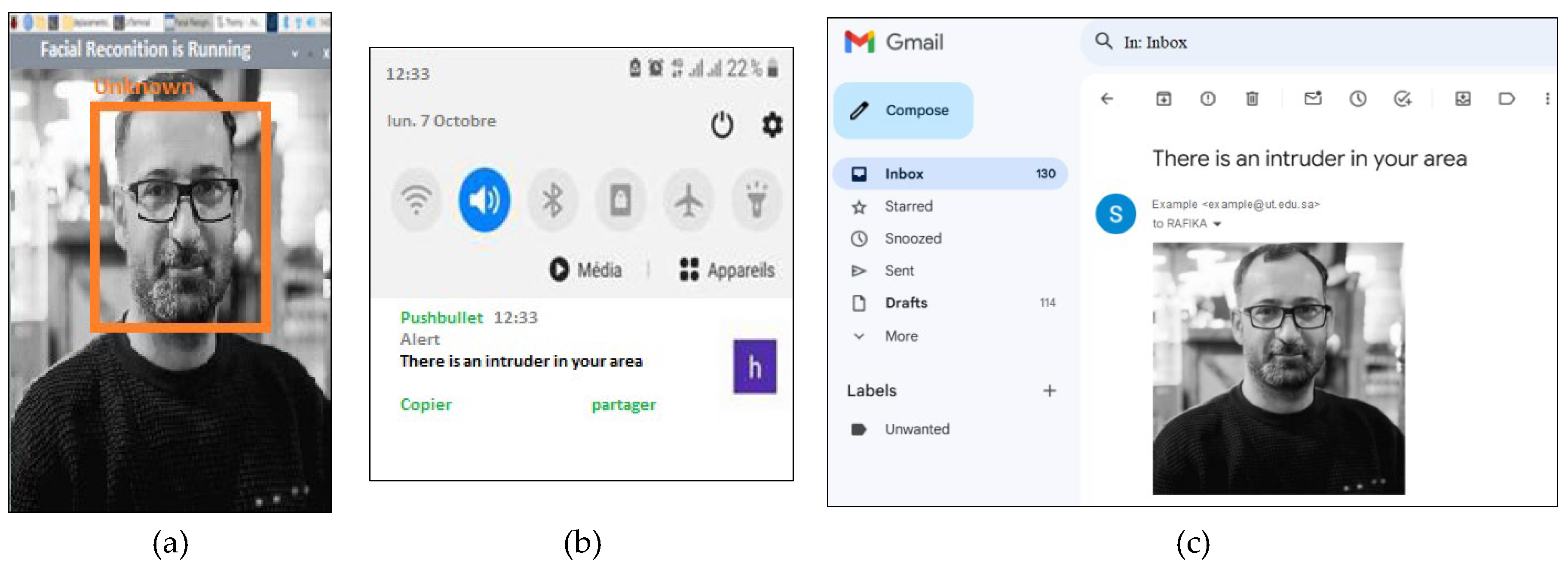

If the facial data of the detected individual does not match any entries in the system’s database, the monitoring system will label the person as “unknown,” as demonstrated in

Figure 8(a). Simultaneously, the system triggers an alert by sending a notification and an email containing a captured image of the individual to the room control center, as illustrated in

Figure 8(b) and

Figure 8(c), respectively. This ensures timely awareness and response to potential security concerns.

In order to evaluate the performance of the proposed face recognition method, we conducted different experiments using the same dataset. Firstly, we compared the accuracy of face recognition methods using different feature extraction techniques. Secondly, we evaluate the performance of face recognition algorithms using different classifiers: Support Vector Machines (SVM) [

12,

19], k-Nearest Neighbours (KNN) [

20], and K-means clustering [

30]. In addition, we compared these results to those obtained by the state-of-the-art face recognition methods such as the DCP and LBP method [

31], the Facial recognition system using local binary patterns (LBP) [

32], the Face recognition method based on statistical features and SVM classifier [

12].

The ORL dataset consists of 400 images taken from 40 different people, 10 poses for each person. The images were then converted into JPEG image format without changing their size. The images are stored in gray level format, take 8 bits, and has the intensity range from 0 to 255. Five individuals with 6 images for each person of the ORL face images are showed in

Figure 9.

The images were then split into two sets. One set was used for training and the other set was used for testing. Frequently, datasets are isolated into training and testing datasets in the proportion of 45:55. Hence, 180 images are randomly chosen as training sets with 220 images from all cases. In order to reduce the training set dimension, the training sets include 30, 60, 90, 120, 150 and 180 images according to chosen pose count. For each person, poses with the same indices are chosen for the corresponding set.

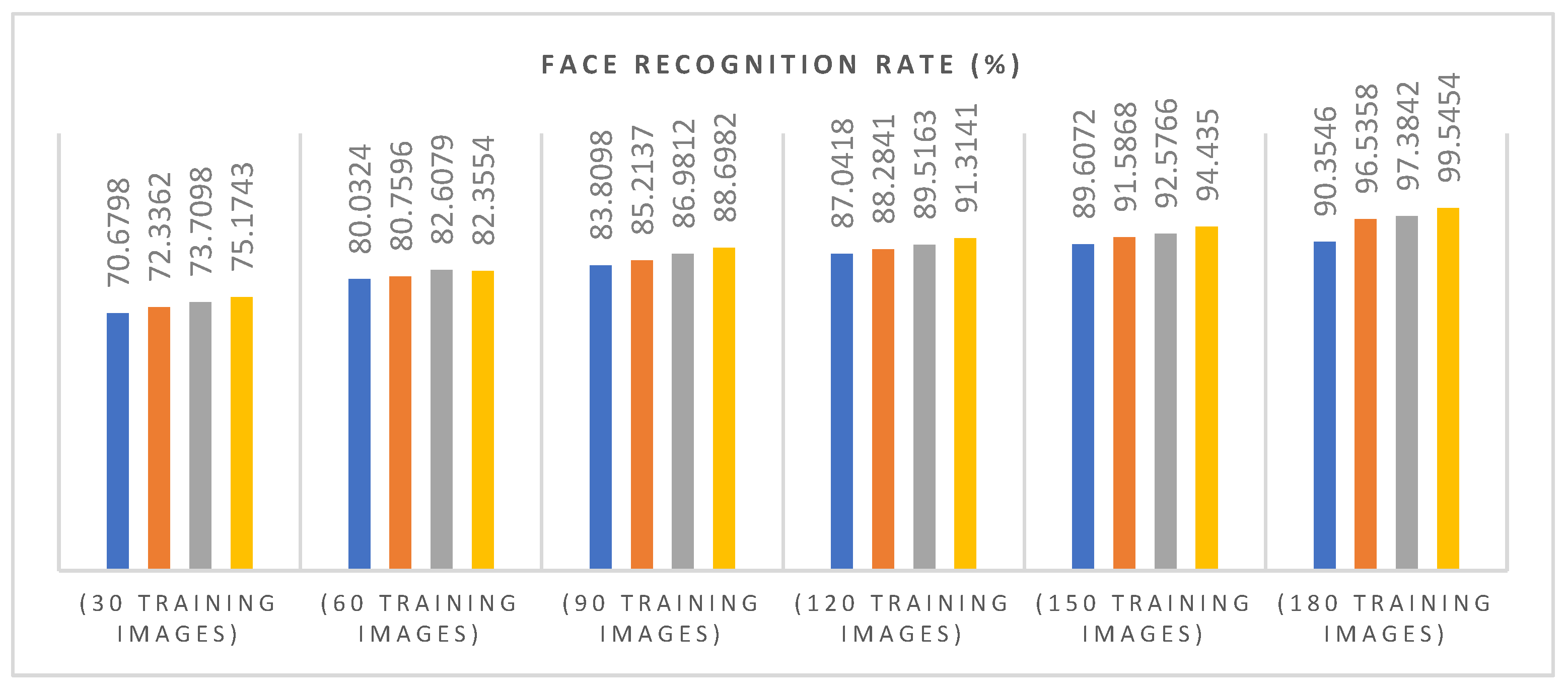

Table 1 shows the results obtained by the proposed method according to increasing pose count and the dimension of feature vectors. In addition,

Figure 10 shows the Face Recognition rates of our model at different pose counts. The blue, red, green, and white lines represent the Face Recognition Rates by using one, two, three and four features, respectively.

We can notice, as we increase the pose count, the accuracy of the model increases. At pose count 30 and using only 1 feature, the accuracy was around 75.1743%. At pose count 150 and using 4 features, the accuracy increased to about 94.435% and then continued to rise until pose count 180 with 4 features where a peak level (99.5454%) in recognition performance is obtained with the proposed method.

To evaluate our method, we compare and contrast the results of the proposed method with other published reports recently applied to face recognition. These include The DCP and LBP method [

31], the Facial recognition system using local binary patterns (LBP) [

32], the Face recognition method based on statistical features and SVM classifier [

12].

Table 2 shows the results obtained from a previous studies [

12,

31,

32], on the ORL database using 45% of each individual’s samples in the training set and 55% of the samples in the test set. As one can notice from

Table 2, a peak level (99.5454%) of Face Recognition Rate and True Positive (219 images) are obtained with the proposed method.

Experimental comparisons use different evaluation protocols, including Face Recognition Rate (FRR) and Equal Error Rate (EER) [

33]. Face recognition rate (FRR) is defined as the percentage of correctly identified faces out of total number of faces. FRR is calculated using the following formula:

Where: is the Face Recognition Rate, represents true positive, i.e., the number of images where the face was detected; represents false negative, i.e., those images where the face was not detected.

The equal error rate () is the minimum probability of making a mistake while recognizing a person’s identity. In order to calculate , we need two parameters: 1) False Acceptance Rate (), which is the ratio of incorrectly accepted images to the total number of images where the faces were detected; 2) True Rejection Rate (), which is the ratio between the number of incorrect rejected images to the total number where the faces were not detected.

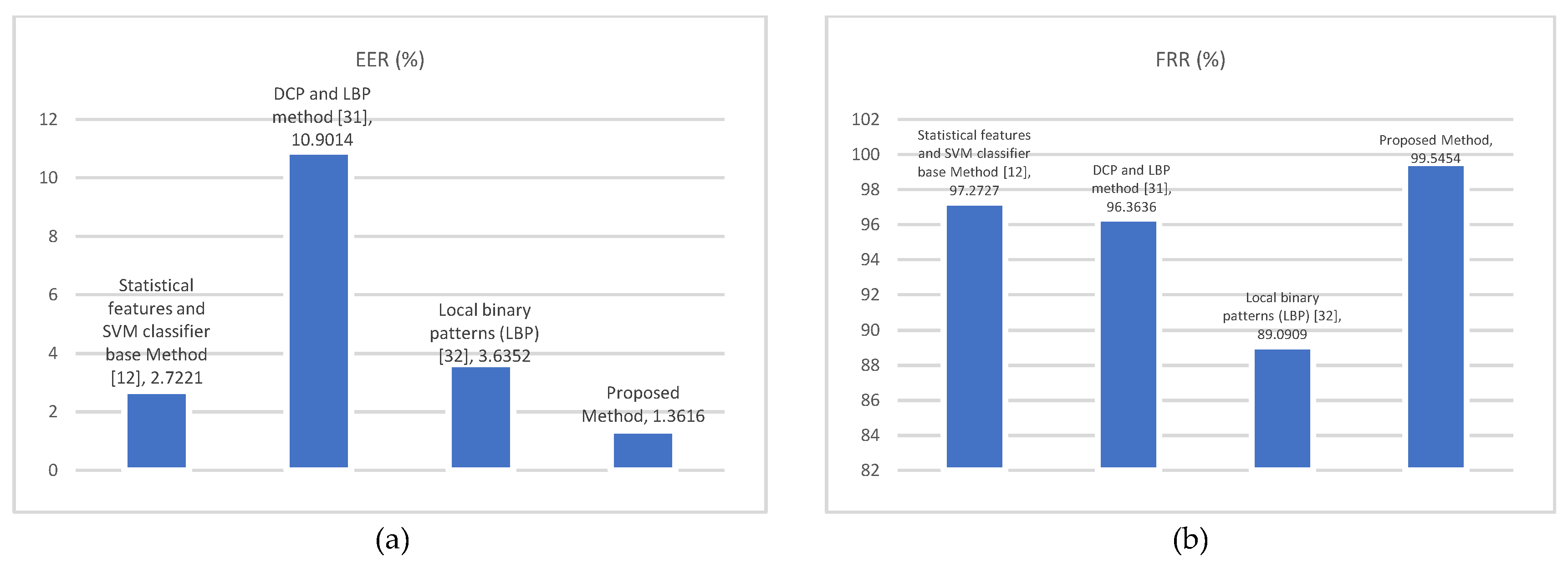

Table 3 shows the EER numerical comparison of the face recognition based on statistical features and SVM classifier (SFSVM) [

12], DCP and LBP method [

31] and Local binary patterns (LBP) [

32]. The intuitive comparisons in terms of EER and FRR between these methods are plotted in

Figure 11.

From

Table 3 and

Figure 10, we can see that proposed method clearly outperforms the other approaches with the EER of 1.3616%, and the FRR of 99.5454%. Hence, higher accuracy rates are obtained with the proposed method. The experiments showed that the proposed method had a lower error rate than the other methods [

12,

31,

32].

The proposed method was tested on a variety of images, demonstrating robustness and high accuracy rates even with poor-quality inputs. Our experimental results revealed that the choice of feature extraction technique significantly impacted face recognition performance. Specifically, the highest accuracy was achieved when the statistical feature extraction method was employed. Furthermore, the face recognition performance improved notably when the classification process utilized evidence theory. Overall, the proposed method proves effective and can be applied to face recognition tasks and mobile.

4. Conclusion

In this paper, a mobile surveillance robot based on Raspberry Pi 4 and IoT is presented. The system can be operated remotely through a web interface and WiFi connection. The robot is designed to continuously monitor a specific area and provides live video streaming when it detects human movement. A new method for face recognition based on high order statistical feature and evidence theory is used to identify whether the detected person is familiar or unfamiliar. If the system identifies an intruder person, it will send out alert notifications and emails via the IoT.

The performance of the proposed human face recognition method is evaluated and a comparative analysis with existing techniques is conducted to demonstrate the effectiveness and robustness of the face recognition algorithm used in this framework. We obtained the highest recognition rate as 99.5454% with the proposed method. Considering the weighted averages of the recognition rates, the proposed recognition method gave better results compared to some existing approaches. Due to these features, the designed robot is suitable for surveillance applications in various environments.

This work can be expanded to develop a mobile security robot able to move autonomously, avoid obstacles, and select the most efficient trajectory. Additionally, more advanced face recognition algorithms could be implemented, allowing the robot to also recognize vehicle license plates.

References

- Ezeji, Chiji Longinus. “Cyber policy for monitoring and regulating cyberspace and cyber security measures for combating technologically enhanced crime in South Africa.” International Journal of Business Ecosystem & Strategy (2687-2293) 6.5 (2024): 96-109. . [CrossRef]

- Dodiya, Kiranbhai Ramabhai, Sai Niveditha Varayogula, and B. V. Gohil. “Rising Threats, Silent Battles: A Deep Dive Into Cybercrime, Terrorism, and Resilient Defenses.” Cases on Forensic and Criminological Science for Criminal Detection and Avoidance. IGI Global, 2024. 123-150..

- Pham, Thanh-Nam, and Duc-Tho Mai. “A Mobile Robot Design for Home Security Systems.” Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research 14.4 (2024): 14882-14887. . [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Inam, et al. “Mobile robot localization: Current challenges and future prospective.” Computer Science Review 53 (2024): 100651. . [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, C., et al. “Facial Recognition Robots for Enhanced Safety and Smart Security.” 2024 Third International Conference on Smart Technologies and Systems for Next Generation Computing (ICSTSN). IEEE, 2024..

- Anurag, Aishwary, et al. “Robotic and Cyber-Attack Classification Using Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Techniques.” 2024 Fourth International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Computing, Communication and Sustainable Technologies (ICAECT). IEEE, 2024..

- Saba K. Naji, Muthana Hamd, ‘’Human identification based on face recognition system’’, 2021 Journal of Engineering and Sustainable Development 25(01):80-91, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Martin, K. Štefan, and F. J. T. L’ubor, “Biometrics Authentication of Fingerprint with Using Fingerprint Reader and Microcontroller Arduino,” TELKOMNIKA Telecommunication, Computing, Electronics and Control, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 755-765, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. J and V. K. S, “Feature Extraction for Human Identification Using Local Ternary Pattern,” International Journal of Advanced Research in Electrical, Electronics and Instrumentation Engineering, vol. 7, no. 3, 2018.

- S. Humne and P. Sorte, “A Review on Face Recognition using Local Binary Pattern Algorithm,” International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology. 2018.

- Fathima AA, Ajitha S, Vaidehi V, Hemalatha M, Karthigaiveni R, Kumar R (2015) Hybrid approach for face recognition combining Gabor Wavelet and Linear Discriminant Analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Graphics, Vision and Information Security (CGVIS), Bhubaneswar, India, 2–3 November 2015. IEEE, Piscataway, NJ, USA, pp. 220–225.

- Slim Ben Chaabane, · Mohammad Hijji, · Rafika Harrabi and · Hassene Seddik, ‘’Face recognition based on statistical features and SVM classifier’’, Multimedia Tools and Applications, springer journal, Volume 81, pp. 8767–8784, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Viola and M. J. Jones, “Robust real-time face detection”, Int. J. Comput. Vis., vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 137-154, May 2004. [CrossRef]

- N. Dalal and B. Triggs, “Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection”, Proc. IEEE Comput. Soc. Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR), vol. 1, pp. 886-893, Jul. 2005. [CrossRef]

- B. Johnston and P. de Chazal, “A review of image-based automatic facial landmark identification techniques”, EURASIP J. Image Video Process., vol. 2018, no. 1, pp. 86, 2018. [CrossRef]

- O.Team, OpenCV, 2018, [online] Available: https://opencv.org/.

- D. E. King, “Dlib-ml: A machine learning toolkit”, J. Mach. Learn. Res., vol. 10, pp. 1755-1758, Jul. 2009.

- Xie, Jiahao, et al. “Unsupervised object-level representation learning from scene images.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (2021): 28864-28876..

- 7-Slim ben chaabane, Rafika harrabi, I. Labiedh and Hassene SEDDIK, ‘’Face Recognition using Fast Fourier Transform and SVM Techniques, ICGST Journal of Graphics, Vision and Image Processing (GVIP), Vol. 21, No.1, pp.1-9, 2021.

- Gou, J., Du, L., Zhang, Y., Xiong, T.: A new distance-weighted k- nearest neighbor classifier. J. Inf. Comput. Sci. 9(6), 1429–1436 (2012).

- S. Ben Chaabane and F. Fnaiech, “Color edges extraction using statistical features and automatic threshold technique: application to the breast cancer cells,” BioMedical Engineering OnLine, 13:4, 2014.pp 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Rafika Harrabi, Ezzedine Ben Braiek, ‘’Color Image Segmentation Using a Modified Fuzzy C-means Method and Data Fusion Techniques’’, Vol. 3, No. 2, Page: 119-134, ISSN: 2296-1739, 2014.

- S. Ben chaabane, M. Sayadi and F. Fnaiech, “Color Image Segmentation Using Homogeneity Method and Data Fusion Techniques’’, EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing, vol.5, 2010.

- R. Harrabi and E. ben braiek, “Color image segmentation using multi-level thresholding approach and data fusion techniques: Application in the breast cancer cells images,” EURASIP Journal on Image and Video Processing, 2012.

- Slim Ben Chaabane, and Anas Bushnag ‘’Color Edge Detection Using Multidirectional Sobel Filter and Fuzzy Fusion’’, Computers, Materials & Continua Journal, vol.74, no.2, pp. 2839-2852, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yang, et al. “Classification of incomplete data based on evidence theory and an extreme learning machine in wireless sensor networks.” Sensors 18.4 (2018): 1046. . [CrossRef]

- Feng, Tianjing, Hairong Ma, and Xinwen Cheng. “Land-cover classification of high-resolution remote sensing image based on multi-classifier fusion and the improved Dempster–Shafer evidence theory.” Journal of applied remote sensing 15.1 (2021): 014506-014506. . [CrossRef]

- Wang, Shuning, and Yongchuan Tang. “An improved approach for generation of a basic probability assignment in the evidence theory based on gaussian distribution.” Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 47.2 (2022): 1595-1607. . [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., et al. “Evidence-theory-based reliability analysis from the perspective of focal element classification using deep learning approach.” Journal of Mechanical Design 145.7 (2023): 071702. . [CrossRef]

- Farhang, Yousef. “Face extraction from image based on K-means clustering algorithms.” International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 8.9 (2017).

- Bhangale Kishor B, Jadhav Kamal M, Shirke YR (2018) Robust pose invariant face recognition using DCP and LBP. International Journal of Management, Technology and Engineering 8(IX):1026–1034 ISSN NO: 2249–7455.

- Priya TS Vishnu, Vinitha Sanchez G, Raajan NR. Facial recognition system using local binary patterns (LBP). Int J Pure Appl Math 2018;119(15):1895–1899.

- Shen W, Surette M, Khanna R (1997) Evaluation of automated biometrics-based identification and verification systems. Proc IEEE 85(9):1464–1478. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).