Introduction

Face recognition is a fundamental application in modern computer vision, widely used in areas such as security, surveillance, and access control [

1] [

2]. Different techniques have been proposed in this domain, and various studies have explored the relationship between Convolutional Neural Networks, fuzzy logic for face recognition [

3] [

4].

Traditional face recognition methods have been instrumental in the evolution of facial recognition technology, laying a strong foundation for contemporary advancements. These methods are broadly categorized into holistic, local, and hybrid approaches. Holistic methods, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), analyze the entire face as a single entity to extract global features [

5]. Independent Component Analysis (ICA) further expanded these methods by considering statistical independence to enhance feature representation [

6]. Local feature-based techniques, including Local Binary Patterns (LBP) and Gabor filters, focus on analyzing specific regions of the face, such as the eyes, nose, and mouth, to improve robustness against variations like partial occlusions [

7] [

8]. Hybrid approaches combine the strengths of holistic and local methods, aiming to balance global and localized feature analysis [

9].

The advantages of these methods include their computational efficiency and effectiveness in controlled environments. Local and hybrid methods, in particular, demonstrated robustness to noise and partial occlusion, making them suitable for certain practical applications. However, these approaches have notable limitations. They are highly sensitive to variations in illumination, pose, and expression, which significantly impact performance in real-world scenarios [

10]. Furthermore, traditional methods struggle to handle large, diverse datasets effectively and are vulnerable to spoofing attacks, such as the use of photographs [

11].

Face recognition systems have garnered significant attention from researchers employing fuzzy logic due to its ability to handle uncertainty and imprecise data, which are prevalent in such systems. Variations in facial features—such as contours, expressions, and lighting conditions—can challenge traditional deterministic approaches. Fuzzy logic offers a flexible framework to model and interpret these variations, enabling more robust recognition in dynamic, real-world scenarios.

In particular, fuzzy logic can be applied during the classification and matching stages of face recognition. By assigning degrees of similarity rather than binary decisions, it enhances accuracy, especially when faces are partially occluded, distorted, or viewed under varying angles and lighting conditions.

In this context, Bahreini et al. [

12] developed a fuzzy logic-based facial emotion recognition software using the CK+ database, supplemented with additional data from 10 participants, totaling 1,000 facial expressions. Their method involves extracting facial landmarks, calculating cosine values for facial triangles, and applying FURIA fuzzy rules. The software achieved an average accuracy of 83.2%, with recognition rates varying across emotions—the highest being for happiness (93.3%) and the lowest for fear (43.8%).

With the same objective, Yadav et al. [

13] proposed the QIntTyII-DLM method, which combines quaternion representation, interval type-II fuzzy logic, and deterministic learning for face recognition. The method was evaluated on the AR, Georgia Tech, Indian Faces (female), and Faces 94 (male) datasets, showing significant error rate reductions compared to other techniques. It preserves structural information from color channels, suppresses redundancy, and effectively handles non-linearity arising from variations in appearance, occlusion, and pose. Results demonstrated a 15–20% error rate reduction for AR, 8–10% for Georgia Tech, and 3–5% for Indian Faces compared to DLM. The main drawback is its dependence on the footprint of the uncertainty parameter in the fuzzy logic step.

Furthermore, AD Algarni et al. [

14] introduced two novel frameworks for generating cancellable face templates: CFR1, which combines intuitionistic fuzzy logic with random projection, and CFR2, which employs a homomorphic transform followed by random projection. Both frameworks aim to create secure and revocable biometric templates by distorting and encrypting original facial features. The approaches were evaluated using multiple datasets (ORL, FERET, LFW) and various performance metrics. Results demonstrated effective discrimination, with correlation scores exceeding 0.3 for authorized users and below 0.05 for unauthorized users. The proposed methods exhibited robustness against various attacks while maintaining strong recognition performance. However, a potential drawback is the computational complexity of the encryption processes, which may impact real-time performance in large-scale biometric systems. Additionally, the multi-stage transformation approach could increase sensitivity to noise or variations in input images, potentially affecting recognition accuracy in challenging real-world conditions.

In addition, Balovsyak et al. [

15] developed a face mask recognition system combining the Viola-Jones method with fuzzy logic. The system detects facial features using Haar cascades and employs Mamdani-based fuzzy logic with triangular membership functions to distinguish between masked and unmasked faces. Implemented in Python with OpenCV and Scikit-Fuzzy libraries, it operates on the Google Colab platform and is designed for use in security and public spaces. While effective, the system is sensitive to lighting conditions and image quality, reducing accuracy in variable environments. Additionally, its reliance on the Viola-Jones method limits its performance with occlusions and unconventional mask types.

Hybrid methods, which combine techniques from holistic and feature-based approaches, have been proposed using Gabor wavelet features in combination with various subspace methods [

16,

17,

18]. In these methods, Gabor kernels with multiple orientations and scales are convolved with an image, and the resulting outputs are concatenated into a feature vector. The feature vector is then down sampled to reduce its dimensionality. In [

16], the feature vector was subsequently processed using the enhanced linear discriminant model introduced in [

19]. In [

17], the downsampled feature vector underwent PCA followed by ICA, and a probabilistic reasoning model from [

19] was utilized to classify whether two images belonged to the same subject. In [

18], kernel PCA with polynomial kernels was used to encode high-order statistics in the feature vector. These hybrid methods demonstrated improved accuracy compared to using Gabor wavelet features alone.

LBP (Local Binary Pattern) descriptors have been a significant component in many hybrid methods. In [

20], an image was divided into nonoverlapping regions where LBP descriptors were extracted at multiple resolutions from each region. The LBP coefficients for each area were then concatenated into regional feature vectors. These regional feature vectors were subsequently projected onto PCA (Principal Component Analysis) combined with LDA (Linear Discriminant Analysis) subspaces. This method was further extended to color images in [

21], incorporating additional color channel information to enhance feature extraction.

Laplacian PCA, an advanced version of PCA, demonstrated superior performance compared to standard PCA and kernel PCA when applied to LBP (Local Binary Pattern) descriptors in [

22]. This enhanced method, Laplacian PCA, effectively captured the local variations and relationships within the data, leading to better discrimination between patterns. In [

23], two novel versions of LBP were introduced: three-patch LBP (TPLBP) and four-patch LBP (FPLBP). These new LBP variants were combined with LDA (Linear Discriminant Analysis) for dimensionality reduction and SVMs (Support Vector Machines) for classification, further improving the accuracy of the hybrid approach. The proposed TPLBP (Three-Patch LBP) and FPLBP (Four-Patch LBP) descriptors can enhance face recognition accuracy by encoding similarities between neighboring patches of pixels.

More recently, [

24] introduced a high-dimensional face representation by densely extracting multi-scale LBP (MLBP) descriptors around facial landmarks. In their experiments, [

24] demonstrated that extracting high-dimensional features significantly boosts face recognition accuracy, increasing it by 6-7% when the dimensionality is increased from 1K to 100K dimensions. However, the main drawback of this approach is the substantial computational resources required to perform dimensionality reduction on such a large scale, which can be computationally expensive and time-consuming. Hybrid methods integrate the strengths of both holistic and feature-based approaches. However, a key limitation is selecting appropriate features that effectively capture the necessary information for face recognition. Some methods address this challenge by combining various types of features, while others incorporate a learning phase to enhance the discriminative power of these features. Deep learning techniques, which will be discussed next, advance these concepts by training end-to-end systems capable of learning a large set of features that are optimal for the recognition task.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are the most widely used deep learning method for face recognition. The main advantage of deep learning methods like CNNs is their ability to learn a robust face representation from large amounts of data, which can handle variations such as illumination, pose, facial expressions, and age. Instead of manually designing features for these variations, CNNs learn them directly from the training data. However, the main limitation is their requirement for very large datasets to generalize effectively to new, unseen samples. Fortunately, several large-scale face datasets have recently been released publicly, providing the necessary data for training CNN models [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

The concept of using neural networks for face recognition is not new. An early approach in 1997, the Probabilistic Decision Based Neural Network (PBDNN) [

32], was proposed for tasks like face detection, eye localization, and recognition. The PBDNN used one fully connected subnet per training subject to reduce hidden units and prevent overfitting. Two PBDNNs were trained using intensity and edge features, with their outputs combined for final classification. Another early method involved combining a self-organizing map (SOM) with a convolutional neural network [

33].

A self-organizing map (SOM) [

34] is an unsupervised neural network that projects input data onto a lower-dimensional space while preserving the topological properties of the input space—inputs that are close together remain close in the output space. Neither the PBDNN [

32] with edge features nor the SOM-based approach [

33] were trained end-to-end and utilized shallow neural network architectures. A later proposal introduced an end-to-end face recognition CNN in [

35].

In this context, Megahed et al. [

36] proposed a hybrid CNN-fuzzy approach for adaptive e-learning, where a CNN classifies facial expressions, and a fuzzy system determines learning levels. Using two custom datasets—a 1,735-instance emotional state corpus and a 72-instance learning activity corpus—their approach demonstrated improved performance on the FER-2013 dataset and enabled adaptive learning flows based on emotional and behavioral responses. However, limitations include potential inaccuracies in facial expression recognition, reliance on facial cues while ignoring other factors, and uncertainties introduced by the fuzzy system. Privacy concerns arise from continuous video monitoring, and the system oversimplifies emotional responses, failing to account for cultural and individual differences. Additionally, the model’s accuracy (67.15%) and its assumption of a direct link between facial expressions and learning effectiveness leave room for improvement.

With the same objective, Jamal Kh-Madhloom et al. [

37] developed a smile detection system integrating CNN and fuzzy logic to improve accuracy in human face analysis. The system, implemented in Python with TensorFlow and Scikit-Fuzzy, analyzes key facial features such as lips and eyes to detect smiles, with applications in biometrics, security, and forensic analysis. The CNN extracts features automatically, while fuzzy logic refines detection for ambiguous data. Despite its improved accuracy, the system's performance is affected by sensitivity to lighting and face orientation. Additionally, unspecified model size and computational demands may limit its use in resource-constrained environments. Among machine learning methods, SVMs are noted for their effectiveness in handling high-dimensional data and establishing optimal decision boundaries.

The described deep learning techniques, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), represent a significant advancement for face recognition tasks. Their ability to learn robust face representations from large datasets allows them to handle variations such as illumination, pose, and facial expressions without the need for manually designed features. However, their main limitation is the requirement for very large datasets to generalize well to new, unseen samples. Early methods like the Probabilistic Decision Based Neural Network (PBDNN) and self-organizing maps (SOMs) utilized shallow architectures and did not train end-to-end, which limited their effectiveness. In contrast, the introduction of an end-to-end CNN significantly improved face recognition by directly optimizing both feature extraction and classification processes, leading to higher accuracy and robustness. Despite these advances, CNNs still face challenges, such as requiring extensive computational resources and being sensitive to input quality, which can affect their performance in practical applications.

This paper introduces a novel face recognition method that combines Support Vector Machine (SVM) as the primary classifier with ResNet50 for robust feature extraction. Fuzzy logic is incorporated to refine the prediction process, improving classification accuracy. SVM effectively distinguishes known faces, while ResNet50 extracts deep, discriminative features. Fuzzy logic enhances decision-making by addressing uncertainties and variations in data, such as lighting and pose changes, thereby optimizing system performance. SVM's ability to find the optimal hyperplane for class separation improves generalization, while the integration with ResNet50 enables the use of meaningful facial representations. The addition of fuzzy logic allows better management of low-confidence predictions and challenges such as misclassification of unknown faces and overlapping feature spaces. This hybrid approach offers improved robustness and accuracy in face recognition tasks.

The rest of this report is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the proposed face recognition method. Section 3 discusses the experimental results, and Section 4 provides the conclusion.

Proposed Method

Face recognition is a biometric technique used to identify individuals based on the unique features of their faces. It provides an automated method for authentication and identification by analyzing facial patterns. These systems are reliable, fast, and effective, making them suitable for use in various environments, such as educational institutions and public spaces, where they play a critical role in enhancing security and improving organizational management [

38].

In this work, we are interested in identifying individuals based on their facial features. The proposed system is conceptually different and explores new strategies. Specifically, it investigates the potential benefits of integrating advanced Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for feature extraction, Support Vector Machines (SVMs) for classification, and fuzzy logic for refining prediction accuracy. By combining these powerful techniques, the system aims to improve the overall robustness and effectiveness of face recognition, particularly in challenging conditions such as varying lighting, facial expressions, or partial occlusion.

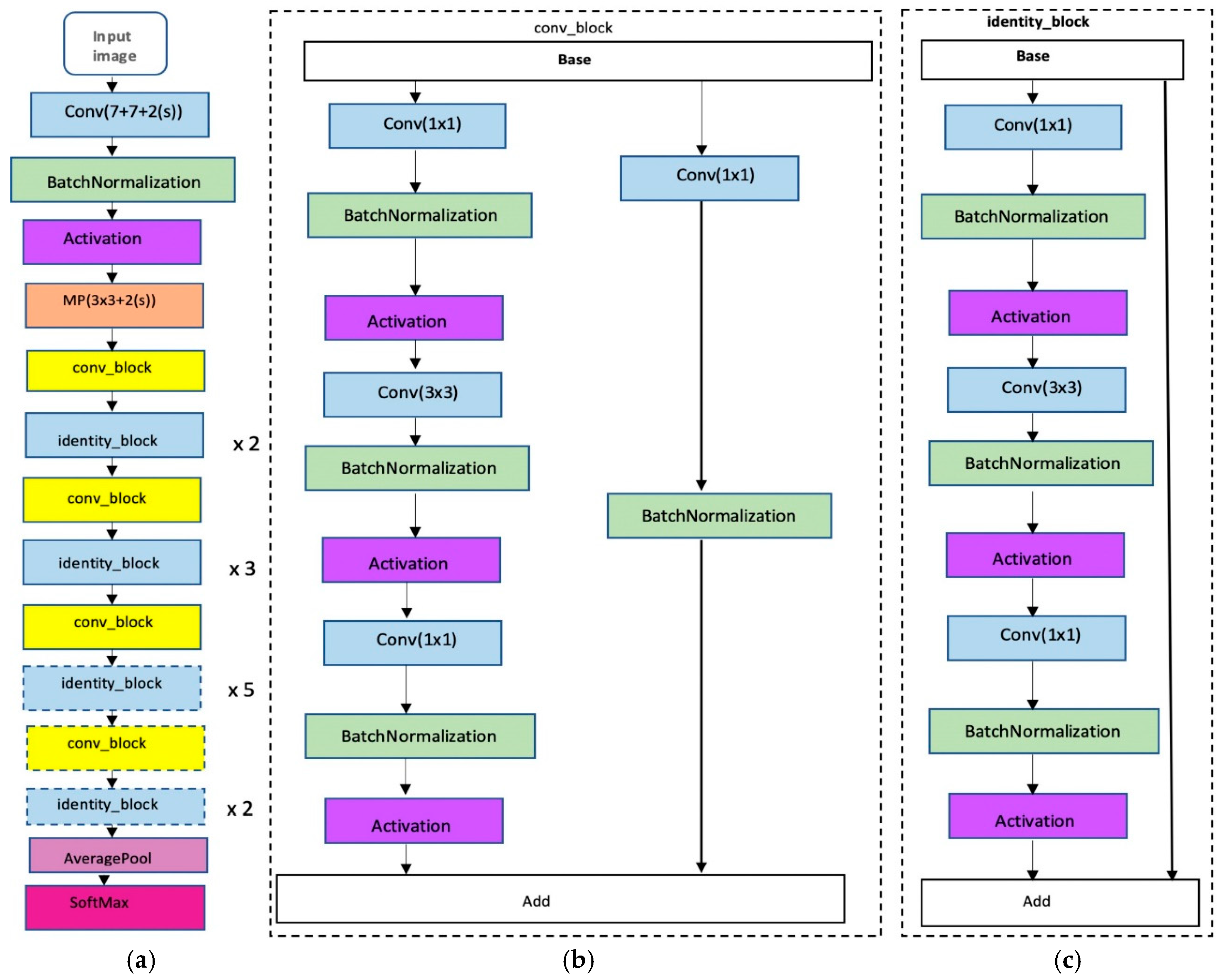

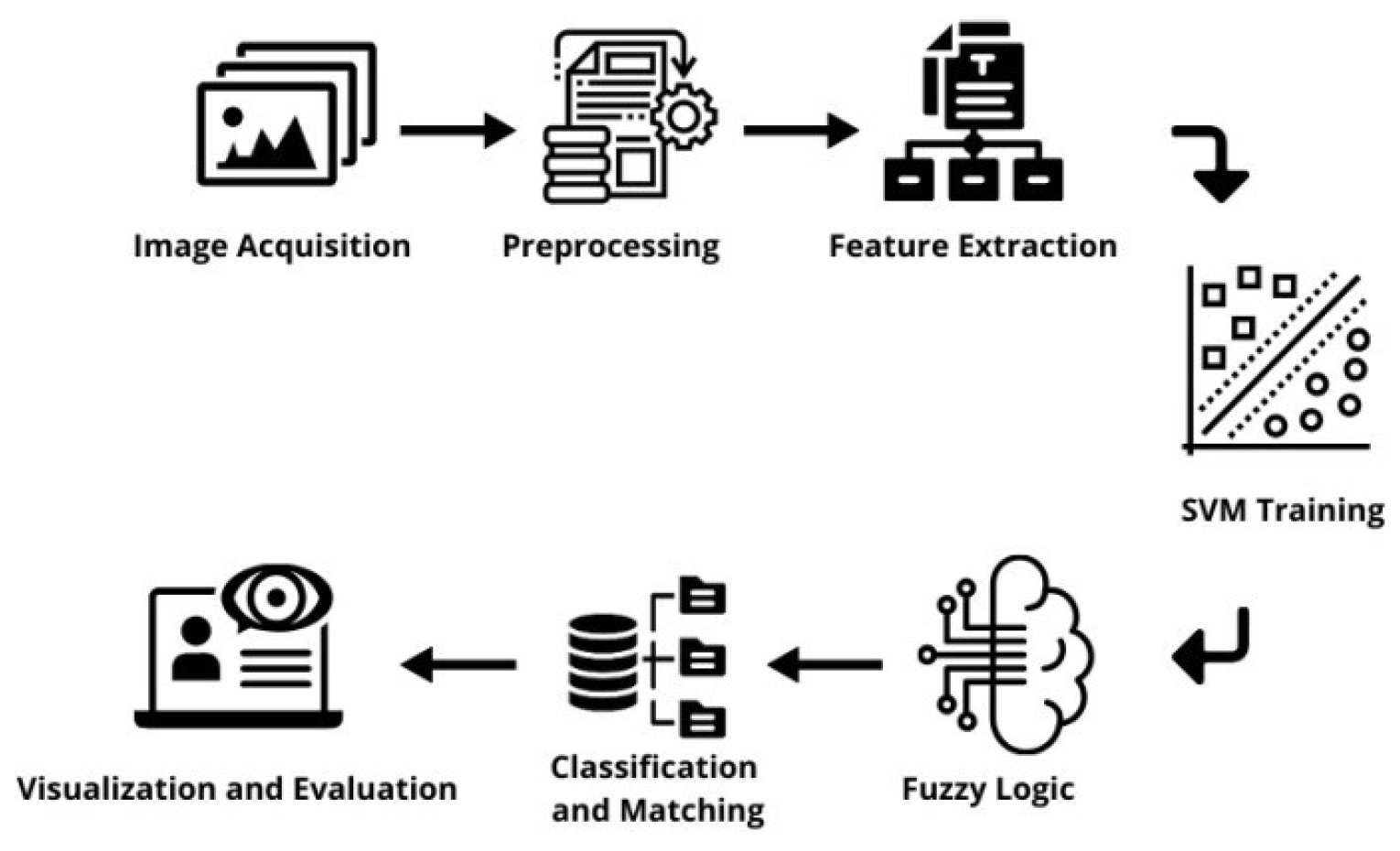

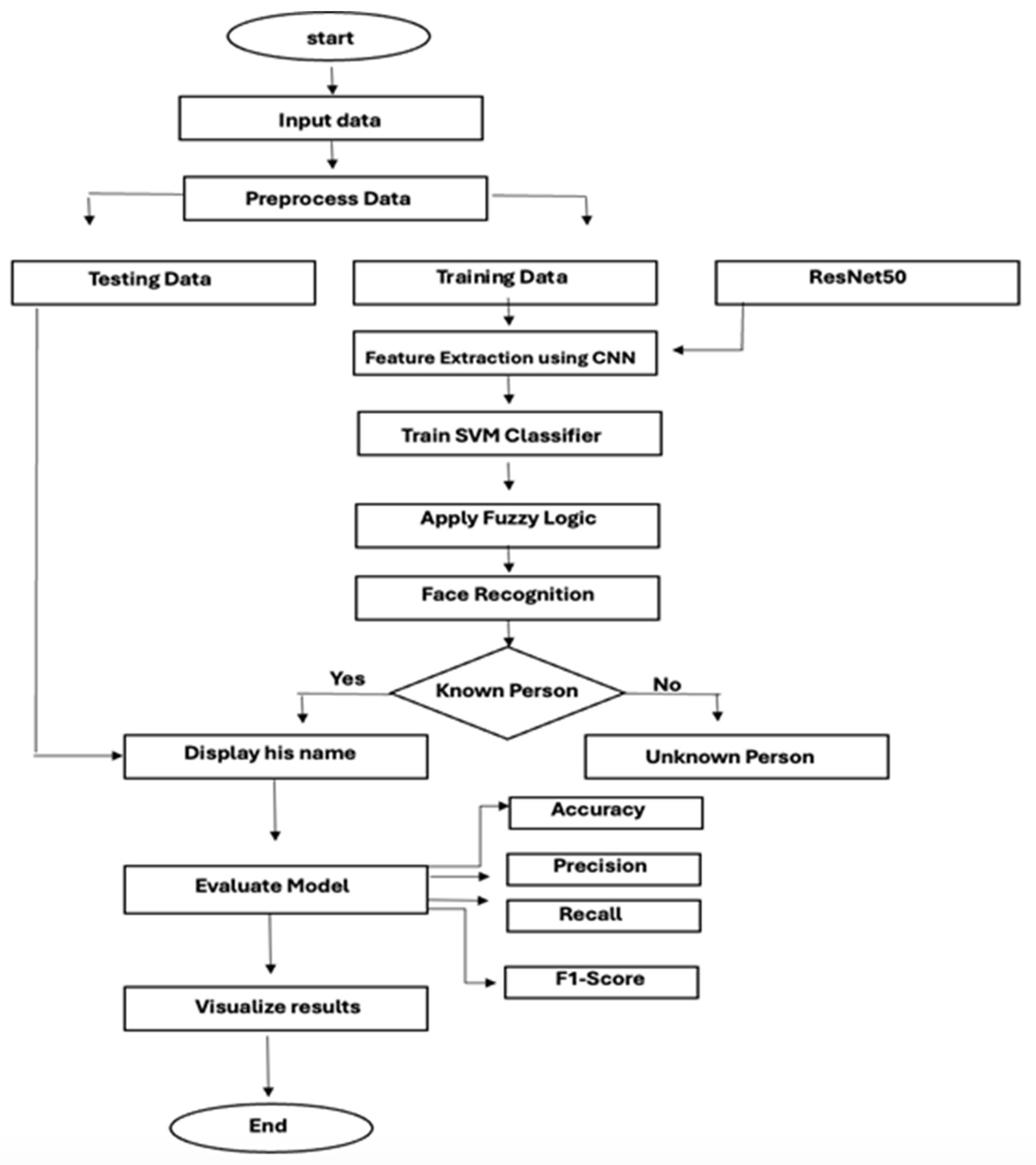

Figure 1 presents the structure of the proposed face recognition method using a hybrid approach. The key steps include image acquisition, where face images are captured for analysis; preprocessing, which normalizes and enhances the input data; feature extraction, to identify and isolate critical facial features; SVM training, to build a robust classification model; fuzzy logic integration, where fuzzy logic rules are applied to refine predictions; classification and matching, to assign identities based on the trained model; and finally, visualization and evaluation, to assess system performance and present results. Each step is crucial for enhancing the system's adaptability and robustness under varying conditions.

The proposed recognition model is structured in several stages to optimize face recognition performance. First, it employs pre-trained Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for feature extraction, leveraging deep learning models to capture rich, discriminative facial features from input images. In the next stage, Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are used for classification, where they separate different classes (i.e., known individuals) based on the extracted features. Finally, fuzzy logic is incorporated to refine the decision-making process by addressing uncertainties and ambiguous data, such as variations in lighting, pose, or expression. This multi-stage approach enhances the system’s robustness and accuracy, enabling it to effectively handle challenging recognition scenarios.

Figure 2 illustrates the flowchart of the proposed face recognition system. The process begins with the input of facial data, which undergoes pre-processing to ensure it is properly formatted and cleaned for analysis. Next, the data is divided into two sets: training and testing. The training set is passed through ResNet50, a pre-trained Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), to extract relevant and deep features from the facial images. These features are then used to train a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier, which learns to distinguish between different individuals based on the facial characteristics.

To further enhance the system’s decision-making, fuzzy logic is applied. This step refines the output by handling uncertainties and ambiguities, particularly in situations where the data is noisy or incomplete. Once the system performs face recognition, it identifies whether the input corresponds to a known individual or an unknown person. If a known person is identified, their name is displayed as the output.

1.1.1. Input Data and preprocessing

The initial step in our face recognition system involves collecting a comprehensive dataset of facial images, which can be sourced from curated databases, live video streams, or static camera captures. In our application, publicly available datasets, such as the Labeled Faces in the Wild (LFW), are used because they offer a diverse range of facial variations, including differences in expressions, lighting conditions, and occlusions. These datasets serve as a vital foundation by providing labeled data essential for training supervised learning models and conducting thorough performance evaluations [

39].

In our application, pre-processing plays a critical role in standardizing image data and reducing variability, thereby ensuring the optimal performance of the recognition system. As a first step, all input images are resized to dimensions of (224 × 224) using bi-cubic interpolation. This resizing process ensures uniformity across the dataset, making the images suitable for model input.

Subsequently, pixel values are normalized to a standardized range, typically between 0 and 1. This normalization process is crucial as it enhances computational efficiency by reducing the dynamic range of the input data, which helps prevent numerical instability during model training. By scaling the pixel values, the system ensures that the model converges more effectively and avoids issues such as exploding or vanishing gradients, ultimately contributing to more stable and accurate training outcomes.

Figure 3 displays a collection of datasets, including LFW, which are used for benchmarking and evaluating the performance of our proposed method. These datasets consist of diverse samples and are integral for training, testing, and validating the proposed computational model.

The LFW dataset consists of 13,233 face images, which are divided into training, validation, and testing sets. Specifically, 60% of the images from each class are allocated for training, 20% for validation, and 20% for testing. The dataset is utilized for a binary classification task, distinguishing Know and Unknown person. To enhance the training data, data augmentation techniques are applied. One such technique is Noise Injection, where random Gaussian noise is applied to the images. This involves adding small, random variations in pixel intensity values across the image, mimicking sensor imperfections or environmental noise during data acquisition.

In addition to these steps, alignment techniques are applied to the images to ensure that facial features, such as eyes, nose, and mouth, are consistently positioned across samples. This alignment significantly enhances the accuracy of feature extraction by reducing spatial variations caused by differences in pose, scale, or orientation. Collectively, these pre-processing techniques establish a solid foundation for accurate and reliable face recognition.

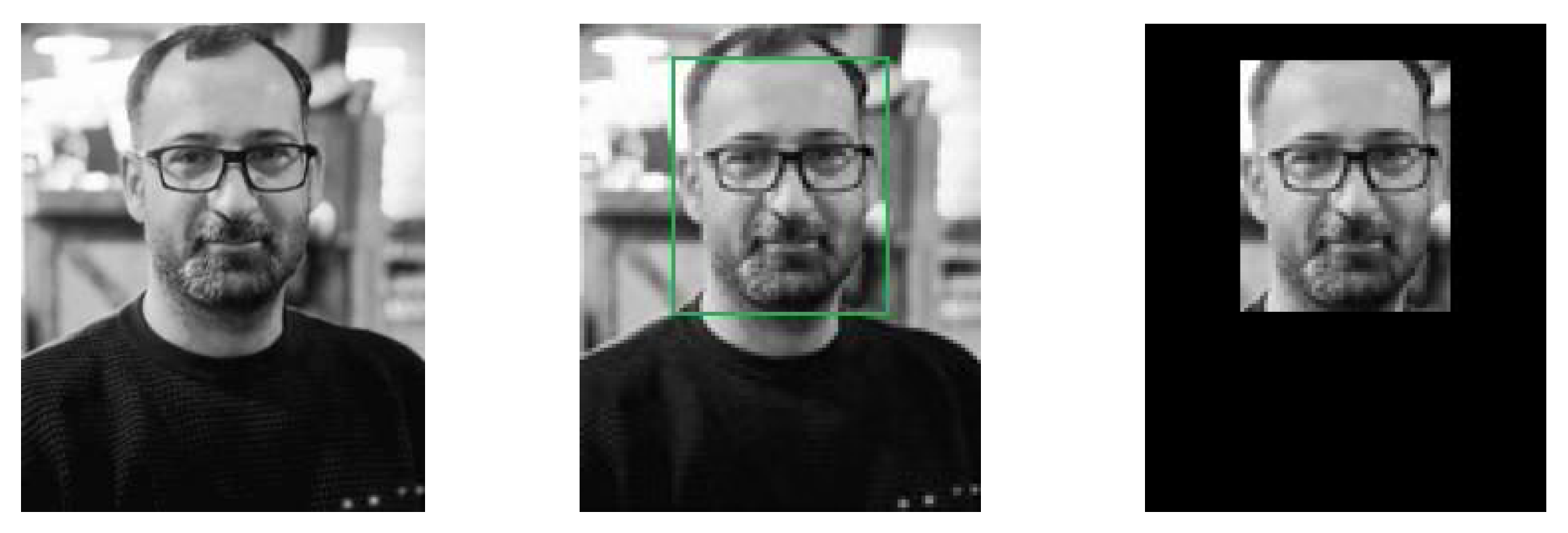

The MediaPipe Face Detector is an advanced machine-learning framework developed by Google as part of its MediaPipe library [

40]. It facilitates real-time detection and localization of human faces in images and videos, making it an efficient and scalable solution for various applications. In our work, the MediaPipe Face Detector is employed on input images to accurately localize facial regions.

Figure 4 presents the face detection using MediaPipe Face Detector. The preprocessing step here served to reduce the area used for the classification, i.e., consists of isolating the face area from its surroundings.

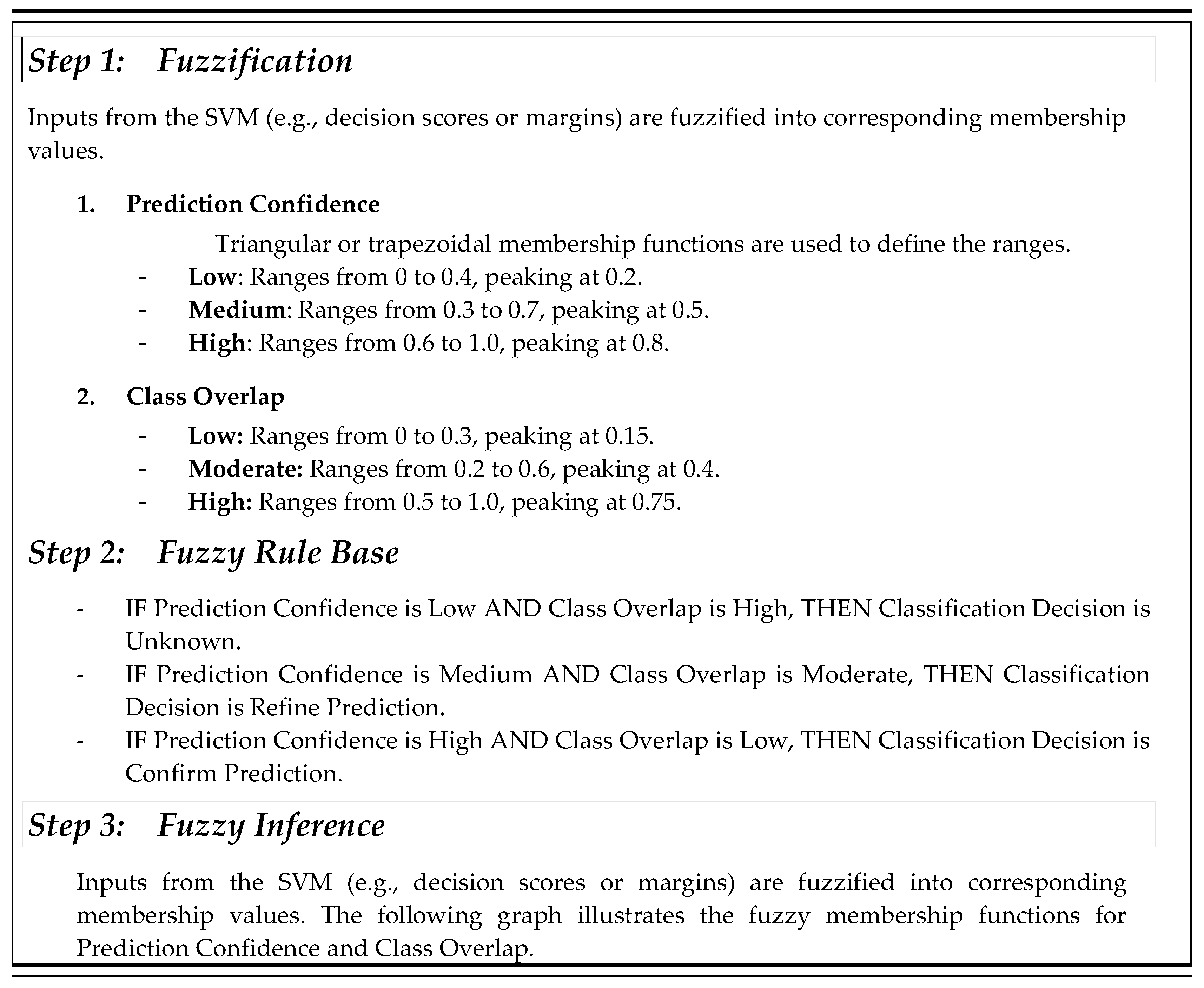

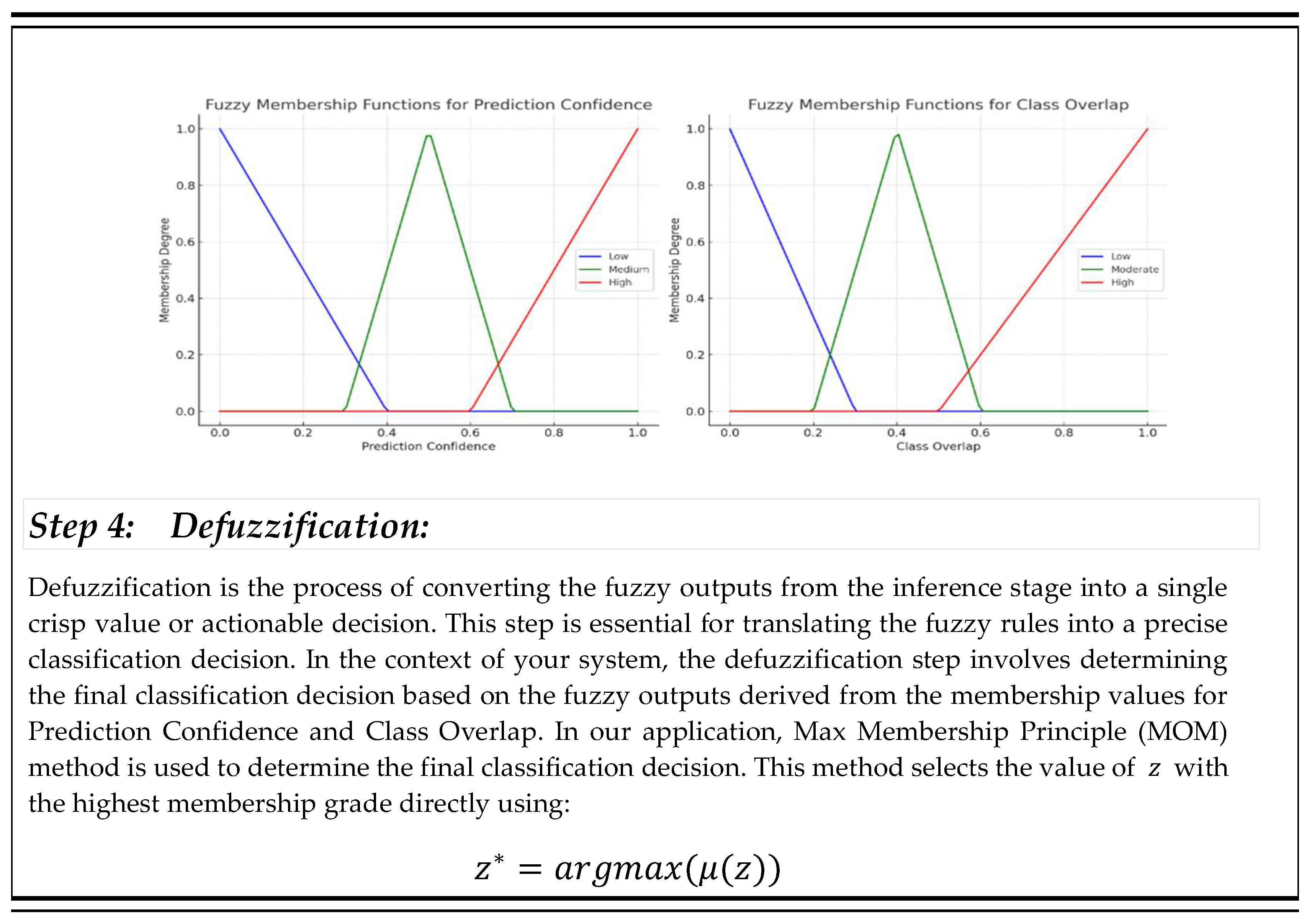

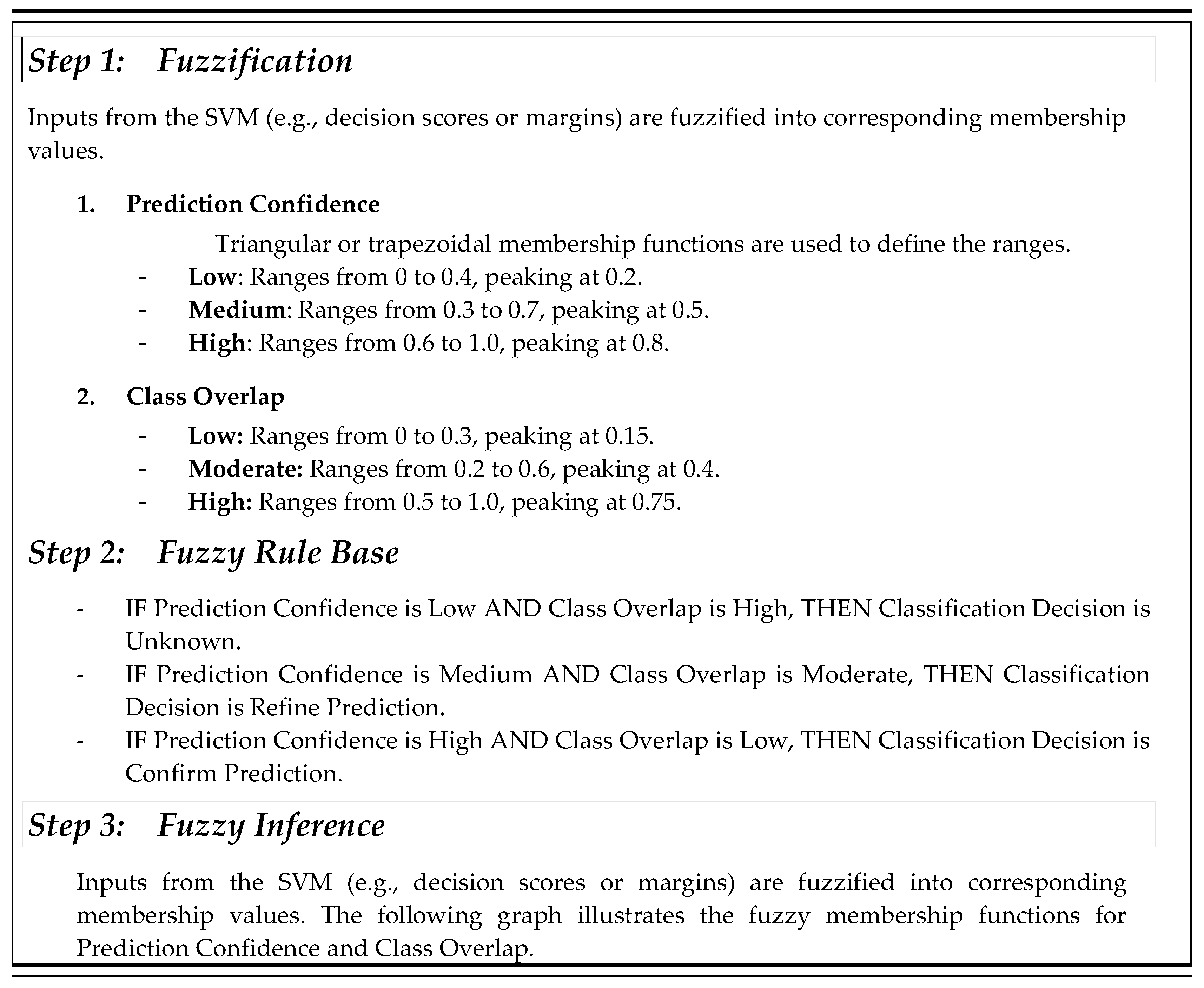

1.1.1. Fuzzy rules

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) classify data by identifying optimal hyperplanes in feature spaces. While highly effective, SVMs may struggle with borderline cases or data exhibiting significant overlap between classes. Integrating a fuzzy inference system provides a mechanism to handle such uncertainties by introducing graded classifications and refining outputs.

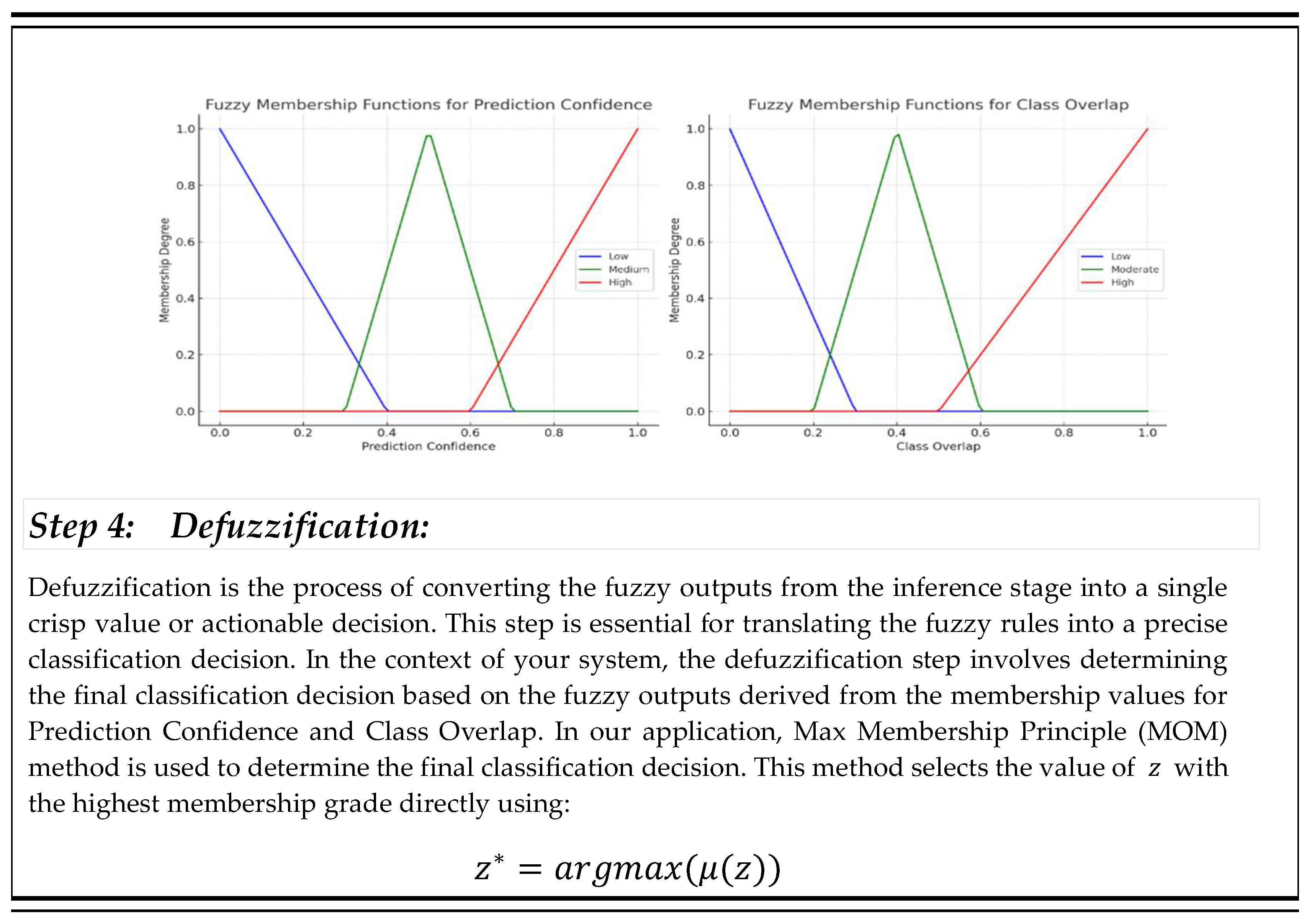

Membership functions are utilized to map input variables into fuzzy sets effectively. In this implementation, Prediction Confidence, which reflects the confidence level of SVM predictions and ranges from low to high, is categorized into three fuzzy sets: Low, Medium, and High. Similarly, Class Overlap, which quantifies the degree of overlap between classes for a given input, is divided into three fuzzy sets: Low, Moderate, and High. To ensure smooth transitions between these categories, triangular and trapezoidal functions are commonly employed to represent the fuzzy sets. The four main components of the fuzzy inference system (FIS) are depicted in the algorithm 1.

By combining SVM outputs with uncertainty metrics, the fuzzy inference system ensures that decisions are informed by contextual information. This integration reduces misclassifications and enhances the model’s adaptability to complex datasets. Integrating a fuzzy inference system with SVM effectively handles uncertainties and imprecise data. This approach ensures smooth transitions across decision boundaries, robust classification of borderline cases, and improved prediction accuracy, thereby enhancing the reliability of the overall system.

Experimental Results

The study implemented the proposed method for Face recognition, as illustrated in

Figure 2. This method utilizes feature vectors derived from training images as inputs, producing classification information for each data point as output.

In this section, we first introduce the dataset and evaluation metrics employed in the study. The performance of the proposed method is then demonstrated through a series of experiments, including quantitative comparisons, misclassification analysis, parameter analysis, computational complexity evaluation, and generalization tests.

1.1. Dataset

To evaluate the proposed method, LFW datasets were utilized in this study. The Labeled Faces in the Wild (LFW) dataset is a benchmark dataset widely used for the task of face verification. Introduced in 2007, it was designed to challenge face recognition systems with real-world images that include variations in lighting, pose, expression, and occlusion. The dataset contains a collection of face images from the internet, making it diverse in terms of age, gender, and ethnicity. The LFW dataset is particularly important for evaluating face verification algorithms, which determine whether two given images belong to the same person or not.

LFW datasets contains 13,233 images of 5,749 individuals, taken in real-world, uncontrolled environments with variations in pose, lighting, and facial expressions. For evaluation purposes, the dataset is split into two subsets, with the second subset serving as a standard benchmark. This benchmark consists of 10 groups, each containing 300 positive and 300 negative image pairs, used for cross-validation. While the LFW dataset has made substantial contributions to the advancement of face verification techniques, it does have some limitations. One notable issue is the uneven distribution of images, with 4,096 individuals represented by just one image each. Despite these drawbacks, the LFW dataset continues to be a widely adopted benchmark, with numerous deep learning models achieving near-perfect accuracy in face verification tasks [

39].

Table 1 presents the descriptions of the LFW Dataset.

1.1. Performance Measures

The proposed model was rigorously evaluated to ensure its effectiveness and reliability. Standard public face image datasets were utilized to assess the model's performance. Specifically, each dataset was divided into two parts: three folds were used for training, while the remaining fold was used for testing in each iteration. Comparative analyses with existing state-of-the-art models were also conducted to highlight the improvements introduced by the proposed method.

Performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and computational efficiency were analyzed to provide a comprehensive assessment [

45][

46]. Accuracy represents the proportion of correct predictions to the total number of samples. Precision is defined as the ratio of true positive samples to the total number of positive predictions. Recall is the ratio of true positive samples to the total number of samples in the positive class. The F-score, which is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, was also calculated. The formulas for these metrics are provided below:

Accuracy reflects the overall correctness of the model by calculating the ratio of correctly predicted instances (both true positives and true negatives) to the total instances examined.

Precision measures the proportion of true positive predictions relative to the total positive predictions made by the model, indicating the model's effectiveness in minimizing false positives.

F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced measure that accounts for both false positives and false negatives, making it particularly useful in situations where class distribution is imbalanced.

Recall, also known as sensitivity, measures the model’s ability to identify all relevant positive instances, calculated as the proportion of true positives to the total actual positives.

Specificity assesses the model's ability to correctly identify negative instances by calculating the proportion of true negatives to the total actual negatives.

Where, TP (True Positive) refers to the number of positive samples correctly predicted. FP (False Positive) represents the number of negative samples incorrectly classified as positive. TN (True Negative) is the number of negative samples correctly identified. FN (False Negative) denotes the number of positive samples mistakenly classified as negative.

By analyzing these metrics, we can gain a comprehensive understanding of the proposed model's performance and its effectiveness in accurately categorizing the data.

Quantitative comparison and analysis

The performance of the face recognition system was evaluated using the Labeled Faces in the Wild (LFW) dataset. On the LFW dataset, the competing methods consist of five widely adopted approaches, which include Bahreini et al. [

47]; Megahed et al. [

48], Khan et al. [

49], Abdullah et al. [

50] and Huang et al. [

51]. A detailed comparison of their performance is provided in Table 4.

As shown in

Table 2, the accuracy, precision, recall, and F-score achieved by our proposed method on the LFW dataset exceed 96%. These results highlight the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed model, demonstrating its consistent high performance in all key evaluation metrics.

The system demonstrated strong performance, achieving an overall accuracy of 92.51%, which indicates that it correctly classified over 92% of the test samples. Additionally, the weighted average precision reached 96.14%, showcasing the model's capability to deliver accurate predictions with minimal false positives. The weighted average recall was 93.2%, reflecting its effectiveness in identifying true positives across the majority of labels. Furthermore, the weighted average F1-Score also stood at 93.8%, emphasizing a well-maintained balance between precision and recall across the dataset.

Table 2 provides a comparative analysis of face recognition techniques utilized in various research studies, emphasizing the diversity in approaches and datasets. Bahreini et al. [

47] implemented a fuzzy logic-based system using the FURIA algorithm on the CK+ database, achieving an accuracy of 83.2%. Similarly, Megahed et al. [

48] proposed a hybrid approach combining Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) with fuzzy logic and tested it on the FER-2013 dataset, yielding an accuracy of 67.15%. On the other hand, Khan et al. [

49] adopted a machine learning approach leveraging the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) algorithm and achieved a variable accuracy 77.5% using the NCR-IT dataset. Abdullah et al. [

50] applied the PCA algorithm in a real-time video streaming context, reporting an accuracy of 80%. Huang et al. [

51] introduced an innovative method based on Point-to-Set Correlation Learning (PSCL), which was evaluated on the COX face database, resulting in accuracy 52.11%. These studies collectively highlight the importance of the choice of algorithm and dataset in determining the effectiveness of a face recognition model.

In contrast, the proposed method presented in this study stands out by utilizing a hybrid approach that integrates CNN, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and fuzzy logic. This methodology was tested on the Labeled Faces in the Wild (LFW) dataset, a standard benchmark in face recognition research. The proposed model achieved an impressive accuracy of 92.51%, significantly outperforming the other techniques listed in

Table 2. The superior performance can be attributed to the effective combination of CNN's feature extraction capabilities, SVM's robust classification potential, and fuzzy logic's ability to handle uncertainty. This result demonstrates the advantage of hybrid models in achieving high recognition accuracy, particularly when benchmarked against state-of-the-art approaches.

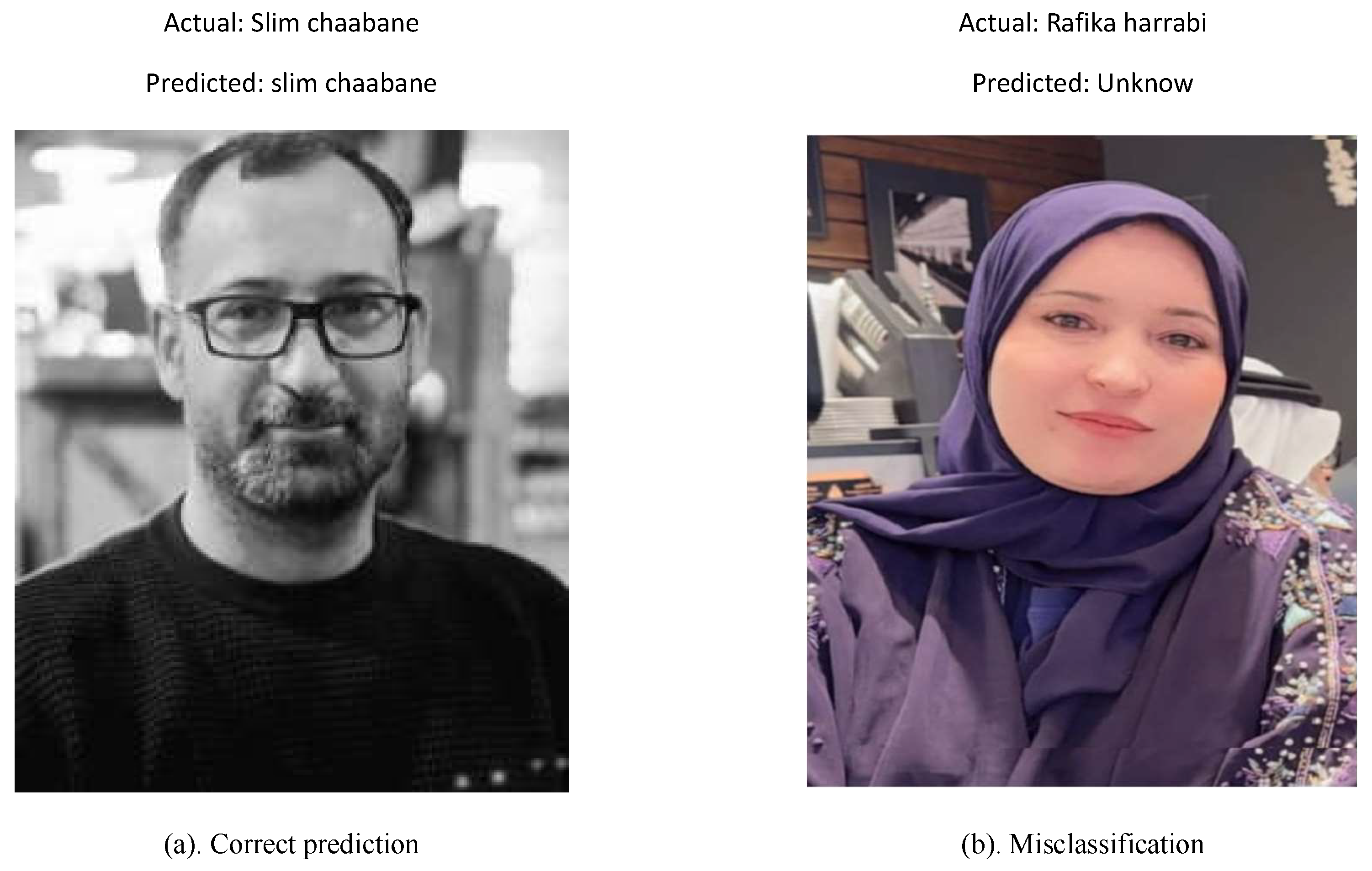

In addition to quantitative evaluation, the system's predictions were analyzed through visual outputs.

Figure 6 shows examples of the system’s performance.

The images above demonstrate the performance of the face recognition system. The first image represents correct predictions, where the system successfully identified the individual, showcasing the model's ability to handle well-represented and distinct classes effectively. However, the second image highlight misclassification. In this image, the actual label was incorrectly predicted as "Unknown," likely due to insufficient representation of this class in the training data and potential variations in facial features or conditions. These misclassifications emphasize the need for a more balanced and diverse dataset, as well as potential improvements in feature extraction and classification methods, to enhance the system’s performance across all classes.

The proposed face recognition system exhibited strong performance, achieving an overall accuracy of 92.51% on the LFW dataset. By combining Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Support Vector Machines (SVMs), and fuzzy logic, the system effectively tackled challenges associated with real-world conditions, including variations in lighting, facial expressions, and pose. This hybrid approach demonstrates its ability to handle uncertainties and improve classification accuracy.

The system achieved outstanding results for well- represented classes, with near-perfect precision and recall for individuals with ample training data. However, classes with limited representation showed weaker performance, underscoring the importance of a more balanced dataset to enhance recognition across all categories.

Hence, the hybrid system provides a robust framework for practical applications, particularly in security, authentication, and adaptive systems. The use of fuzzy logic enhanced decision refinement, making the system more adaptable to uncertainties. However, challenges remain, including computational complexity, which could hinder real-time deployment in resource- constrained environments, and sensitivity to data imbalance, which impacts the system's generalizability to less-represented classes.