1. Introduction: An Environmental History of Japan

To accurately describe a historical environment, one must focus on concrete elements such as forests, oceans, diverse organisms, natural disasters, waste, microorganisms, viruses, air, and water. Otherwise, the description will be inaccurate. The Handbook of Environmental History in Japan (Fujihara, 2023), published in 2023, has not yet escaped this pitfall. It is valuable that a substantial team of authors, mainly young scholars, introduced environmental history that is not well known in languages other than Japanese to the English-speaking world. However, it must be acknowledged that this is still only a partial description. As with all historiographies, it is difficult to tell the whole story. This is because the environment lies between nature and humans and spans all disciplines, from the humanities and social sciences to the natural sciences. One must always be prepared for some kind of pitfall.

Environmental history for Japanese historians reached its peak more than 10 years ago. Yoshikawa Kobunkan, one of the leading publishers of published works of Japanese history, began publishing in 2012 (Yoshikawa Kobunkan 2012-3). The series titled “Japanese History of the Environment” (the author’s translation) began on October 30, 2012 with “Japanese History and the Environment: People and Nature” (Volume 1 of the series), followed on December 12, 2012 by Volume 4, “People's Activities and Nature in Pre-Modern Times,” on February 6, 2013 by Volume 2, “Life and Prayer in Ancient Times,” and on March 5, 2013 by Volume 3, "Environment and Development in the Middle Ages.” Finally, Volume 5, “Nature Use and Destruction: Modern Times and Folklore,” was published on May 17, 2013. All authors are researchers who didn’t study environmental history as their major field of study. At this point in time, environmental history does not exist as a major field of study within the field of history at universities and other educational and research institutions, and this is still the case today. It was in 2009 when the Association for East Asian Environmental History (AEAEH) was established, and there was the first international conference held in 2011 (

https://www.iceho.org/news/2025/2/11/altered-earth-in-asia-oceans-landscape-atmosphere-aaeh-2025). There is a group for environmental history in Japan that has just been formed at the same time. There was an early publication of this kind when the time had finally come to think about environmental history.

Furthermore, in September 2020, Takeshi Nakatsuka, a paleoclimatology expert at the Research Institute for Humanities and Nature (RIHN), led a giant research project entitled “Re-reading Japanese History from the Perspective of Climate Change.” This project resulted in the publication of a six-volume series limited to the period from ancient to early modern Japanese history. This series was published from September 2020 to January 2021, based on five years of research beginning in fiscal year 2014 (Rinsen Shoten, 2020-21). This research was part of a large project linked to a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and was the result of a dialogue with Japanese historians based on natural science research using new climate change data for the Japanese archipelago from oxygen isotope ratios of annual rings.

However, this was not the end of the story. Unlike the Yoshikawa Kobunkan series, the first in Japan to focus on nature in Japanese history, the Climate Change Project series took natural phenomena as a given and addressed climate adaptation in Japanese society. In other words, we still have a long way to go in terms of the relationship between humans and nature. The reason this series is limited to the early modern period is that we had to focus on humans as recipients of nature. This approach cannot address the Anthropocene period, when human society itself modified nature. At last, there is a groundwork for interactive discussions between humans and nature in Japanese history.

Considering the current state of environmental history research in Japan, this article will demonstrate the limitations of the Anthropocene argument, which sharply distinguishes between pre-modern and modern times. Rather than marking the sudden emergence of an era in which humans began to determine the fate of the Earth, the Anthropocene era is characterized by constant human modification of nature. For example, the construction of PRs in Sanuki, Japan, has been ongoing since ancient times. The author will prove that it is possible to trace the relationship between continuity and change, evolution and regression, and the resilience of nature and socio-technical legislation.

2. Key Questions: Ponds and Reservoirs (PRs) Culture in Sanuki

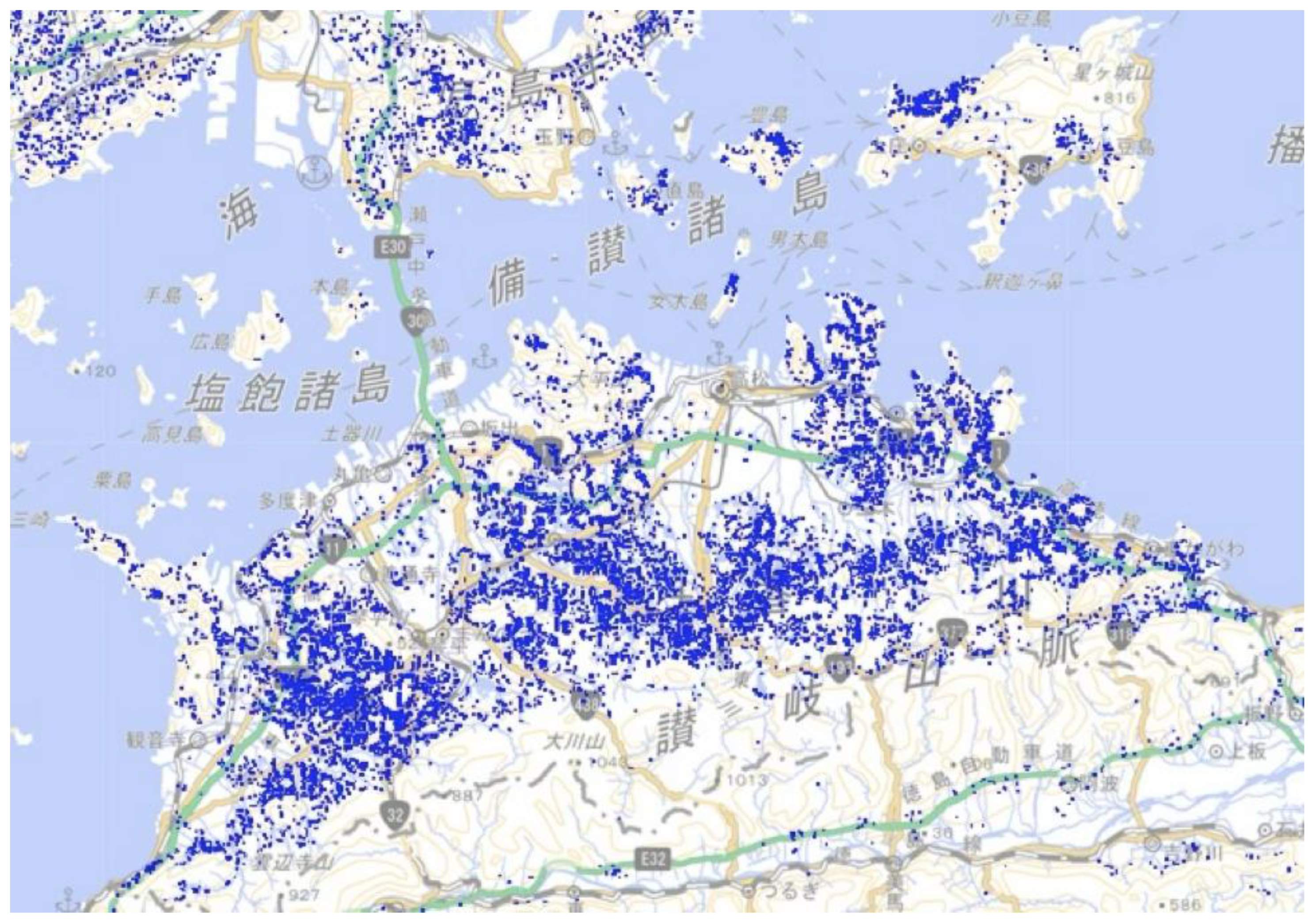

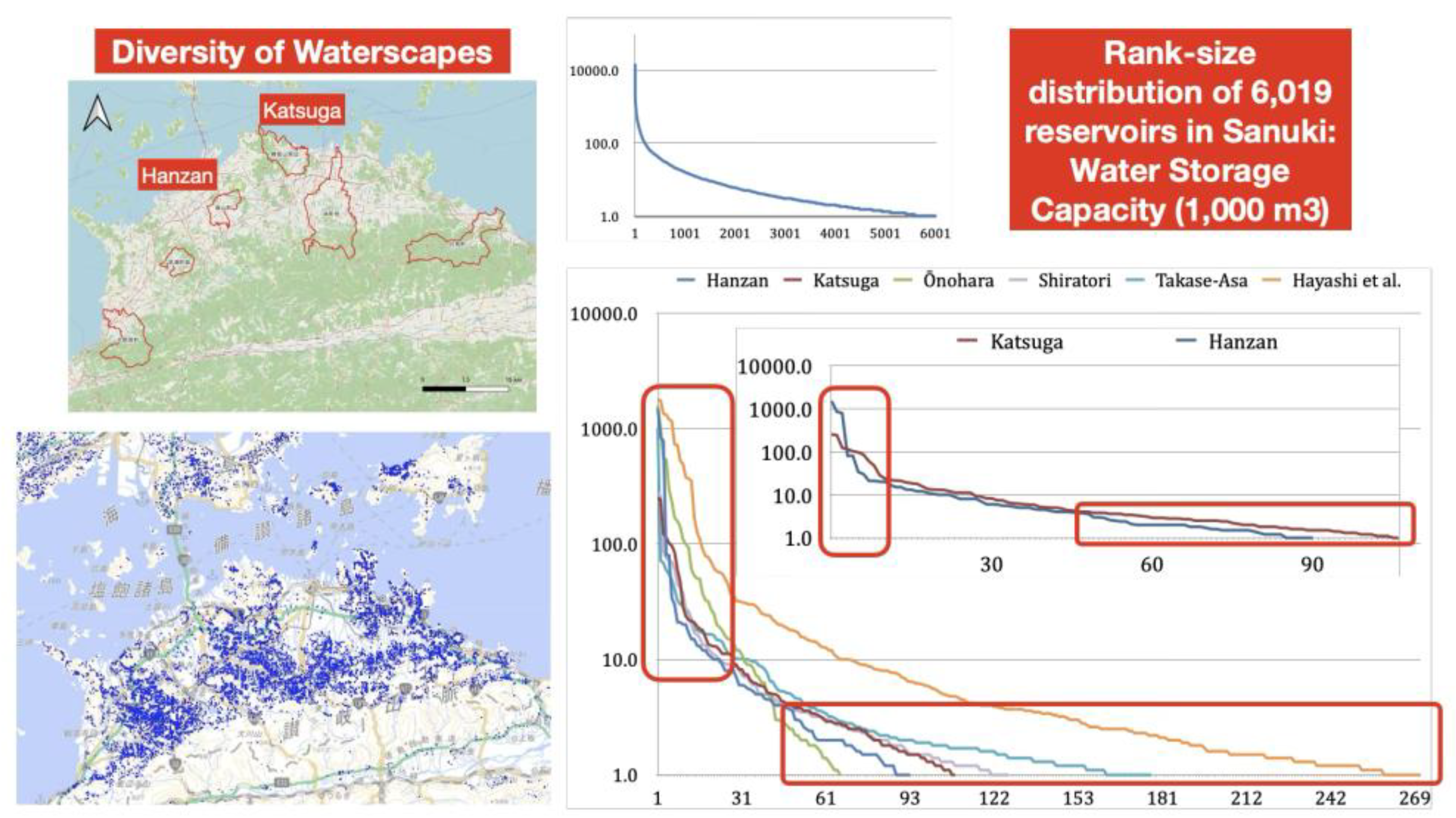

The blue dots on Map 1 represent ponds and reservoirs (PRs). In Japanese, PR means "ike" or "tame-ike," where "tame-ike" means "stored-ike." PRs are the plural form of "ike." The Japanese word "ike" does not distinguish between ponds and reservoirs or between singular and plural PRs. However, the largest ones are not called ike, but rather lakes. In Sanuki, there are only three lakes: Fuchū-ko, Hōzan-ko, and Ōkawa-dam-ko. These lakes were created by modern dam construction.

As of 1999, there were more than two million PRs in Japan (see

Table 1). The Hyōgo, Hiroshima, Kagawa, Yamaguchi, and Osaka prefectures are representative PR regions in Japan. Many PRs are in the Chūgoku region, which includes part of the Kinki region. This area is generally low-rainfall with a Setouchi climate. At that time, Kagawa Prefecture, formerly known as Sanuki, had 14,619 PRs. Ōsaka has the oldest pond in Japan, Sayama-ike, and Kagawa Prefecture has the second oldest, Mannō-ike. Both ponds are small, but Osaka is more urbanized than Kagawa, which has the highest number of ponds at 7.79 per square kilometer.

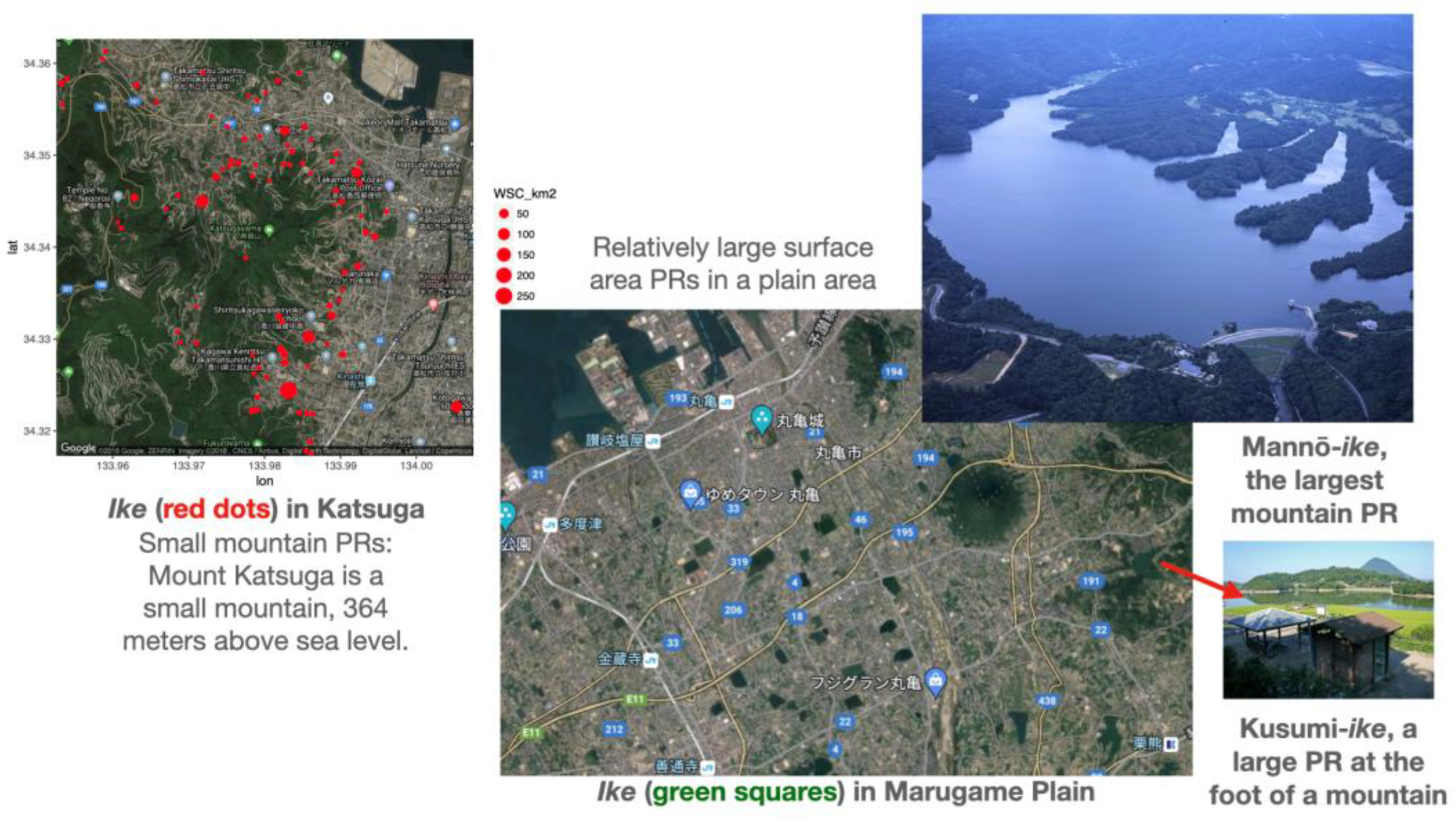

The ike (PR) in Sanuki can be divided into three categories: 1) those in the surrounding area of small, isolated mountains (see Map 2, left), 2) those in plain areas (see middle), and 3) those of various sizes in mountain districts. The largest, ancient-born Mannō-ike is located in the upper right corner of Map 2. It has a bank length of 156 m, a bank height of 32 m, a storage capacity of 15,400 cubic meters, a full water area of 138.5 ha, a landed area of 142.1 ha, and an irrigated area of 3,239 ha. Similar information has been obtained for 6,019 of the 14,619 PRs (Sanuki no Tameike-shi, 2000, p. 13).

Map 2.

Ike (PRs) culture in Sanuki (Kagawa Prefecture). Source: Original dataset (see Appendix).

Map 2.

Ike (PRs) culture in Sanuki (Kagawa Prefecture). Source: Original dataset (see Appendix).

Around the turn of the 21st century, a large volume entitled Sanuki no Tameike-shi was published. Consisting of 1,700 pages of main text and 558 pages of data, the book was written by 119 authors living in Kagawa Prefecture. While the book provides a wealth of knowledge, it contains many common-sense notions. For instance, Takeki Manabe, the governor of Kagawa Prefecture at the time, wrote the following in the book's preface:

Blessed with a mild climate and fertile land, Kagawa Prefecture (Sanuki) has long been one of Japan's leading rice-growing regions. However, due to low rainfall, shallow mountains, and the absence of large rivers, our ancestors had to work hard to secure water and created a unique landscape known as the "tame-ike kingdom."

It is said that 60% of the current rice paddy area was reclaimed during the Nara period (710–794), and a significant number of tame-ike are believed to have been constructed by that time. Nevertheless, the number of tame-ike did not increase dramatically until the period when the development of new rice paddies was promoted.

This is the general understanding of the history of Ike in Sanuki. At first glance, there seems to be nothing wrong with this. But is it correct to assume that precipitation was low, bloody efforts were made to secure water, and 60% of the present paddy fields were cultivated by the Nara period? Furthermore, is it an accurate historical understanding that PRs increased dramatically during the period when the development of new rice paddies was promoted, as exemplified by the early Edo period?

In Japan, where agriculture has developed around paddy rice cultivation, securing water is essential, and the reason PRs were built due to low precipitation is clear. However, why were they so concerned about paddy fields? Why did they want to develop paddy fields in areas with little rainfall? Why did they build PRs to secure water? And how did they acquire the technology and labor to do so? How were the PRs maintained, and who took the initiative to build them?

The historical record is always biased. Large PRs are documented, while small PRs, which can be constructed at the family level, are rarely documented. However, the Chi-Sen-Gōfuroku (Records of Lakes and Springs) (1797) of the Takamatsu clan succeeded in identifying all ponds, reservoirs, and springs in the Eastern Sanuki area, despite being limited to that region of the clan's territory. This demonstrates the importance of PRs and springs for sustaining life at that time and indicates that administrative power had matured sufficiently to control water resources. Furthermore, the PRs documented the size of the paddy fields they could supply, indicating the total amount of rice that could be produced with human resources. In other words, the PRs were understood based on human understanding. In terms of identifying individuals, early modern Japan was one of the few countries in the world with a well-developed administrative capacity.

In recent years, the actual situation regarding the restoration of Mannō-ike, the largest pond in Sanuki during the time of Kūkai (774-835), has been estimated (Sanuki no Tameike-shi 2000, 37). Although it currently has only one-third of its original storage capacity, it can still hold five million tons of water, and its embankment is twenty-two meters high. It is no exaggeration to call it a dam of the modern era. It should be noted that this was an era before the existence of huge, automated machines such as modern earth movers, and the "dam" was built solely by human and animal power. It is estimated that 380,000 man-days of mobilization, including technical staff, were required. How was such mobilization possible when it far exceeded the region's population? This is one of the most important questions addressed in this article.

Kūkai completed the renovation of Mannō-ike in 821 (Kōnin 12) (Sanuki no Tameike-shi 2000, 79). The pond was repaired several times due to floods and other disruptions, but not after May 1, 1184, when a major flood caused the levee to break (Sanuki no Tameike-shi 2000, 82). In 1626, the Sanuki area experienced a drought, with no rain falling for 95 days, and people starved to death. Following a detailed investigation in 1628, restoration efforts began. The turfing of the embankment was completed on February 15, 1631, and a ridgepole-raising ceremony was held (Sanuki no Tameike-shi 2000, 89).

The reconstruction took 1184 to 1631 years. This must have been a significant turning point in the history of labor mobilization for PRs in Sanuki. In other words, using the concept of living spaces, it was a sort of "localization" of people's living spaces through rural independence and self-responsibility based on a peasant economy at the beginning of the early modern period in Japan, mainly from the 15th to the 17th century. The inhabitants of the locality may have assumed responsibility for it. Why did this establishment require such a long period of 447 years? This is the final hypothetical question in this article.

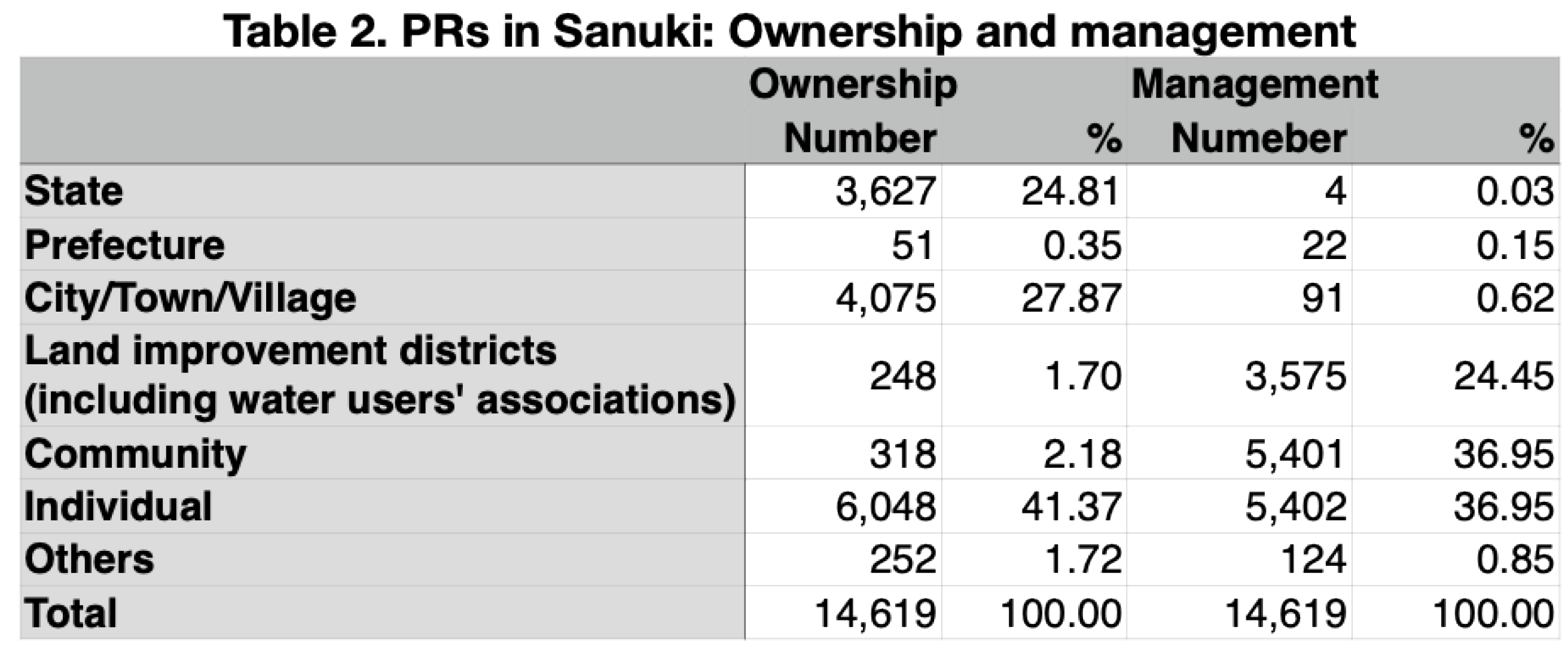

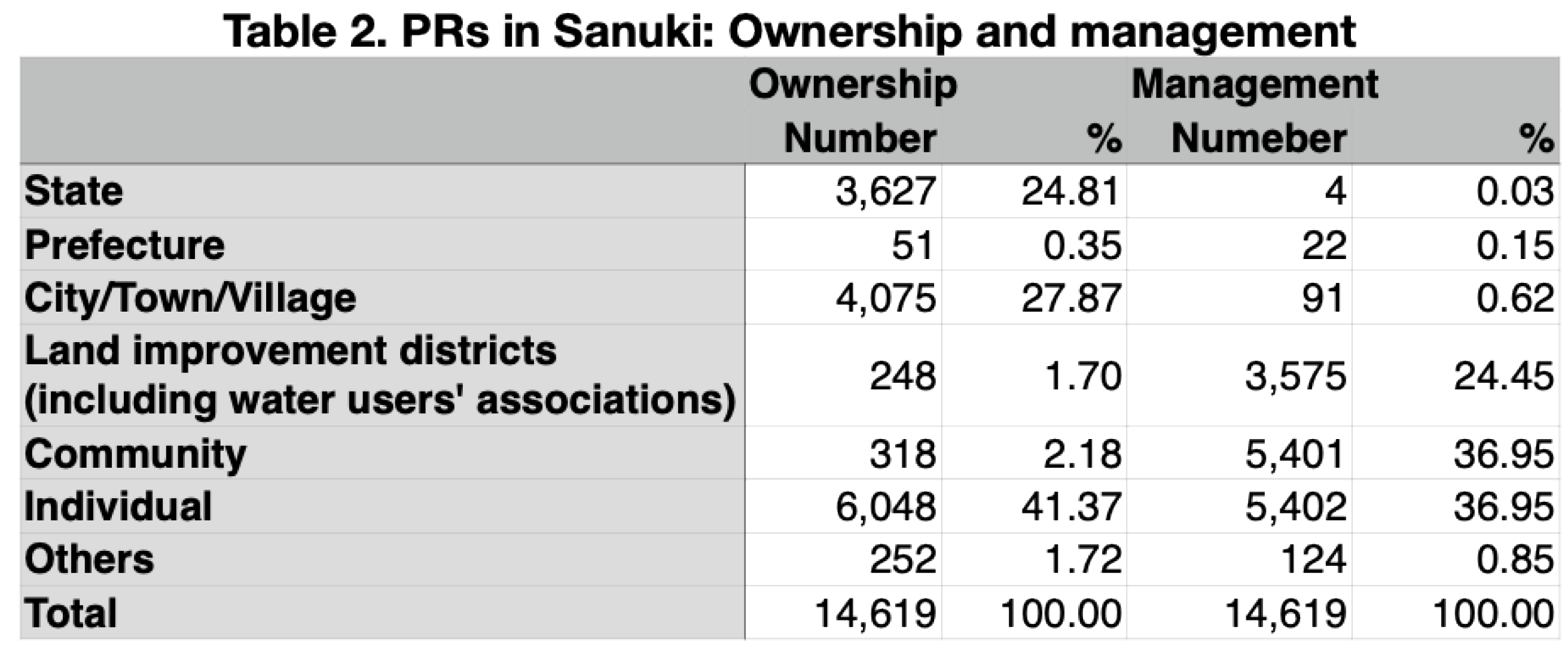

Although there are significant differences in the locations of PRs (see Map 2), Table 2 shows that the management systems for PRs in Sanuki have crucial characteristics in common. Of the 14,619 PRs, 41.37% are privately owned, while 38.95% are managed by individuals. Few are owned by the prefecture. Although nearly 25% are owned by the national government, the government does not manage them. Almost all of them—more than 98%—are managed by local organizations, municipalities, and individuals. In other words, it is important to note that each PR is managed primarily at the local level, a system that has endured to this day.

Source: Sanuki no Tameike-shi 2000, 13.

The academic question addressed in this article is not specific to a specialized field of history. It is also a bold attempt to reexamine 1,400 years of history, from the seventh to the twentieth century, from the perspective of one physical entity: PRs. Narrowing the scope of consideration would challenge Conrad Totman's periodization of Japanese environmental history (Totman, 2014). In his book, which could not refer to the two major edited volumes on Japanese environmental history due to its publication time, he divides Japanese history into seven periods: 1. Hunting and gathering society until 500, 2. Early agricultural society until 600, 3. Early agricultural society from 600 to 1250, 4. Later agricultural society from 1250 to 1650, 5. Later agricultural society from 1650 to 1890, 6. Imperial industrialism until 1890, 7. Entrepreneurial industrialism from 1945 to 2010. This periodization is supported by the general understanding of the transition from an agricultural society to an industrial society. When focusing on the historical development of PRs, this socio-hydrological article's greatest contribution may be its potential to offer new insights into this general periodization.

3. Materials and Methods

The basic data on PRs compiled in Sanuki no Tameike-shi (2000) is being digitized to create a statistical dataset that can be analyzed. This dataset (see Appendix) is the most important material for this article. The data includes the length and height of the banks, the storage capacity, the water, land, and irrigated areas of 6,019 PRs under 14,619 categories. Topographic and historical descriptions of the 668 main PRs are also available. The author also consulted several local histories and topographies of Sanuki regarding these PRs.

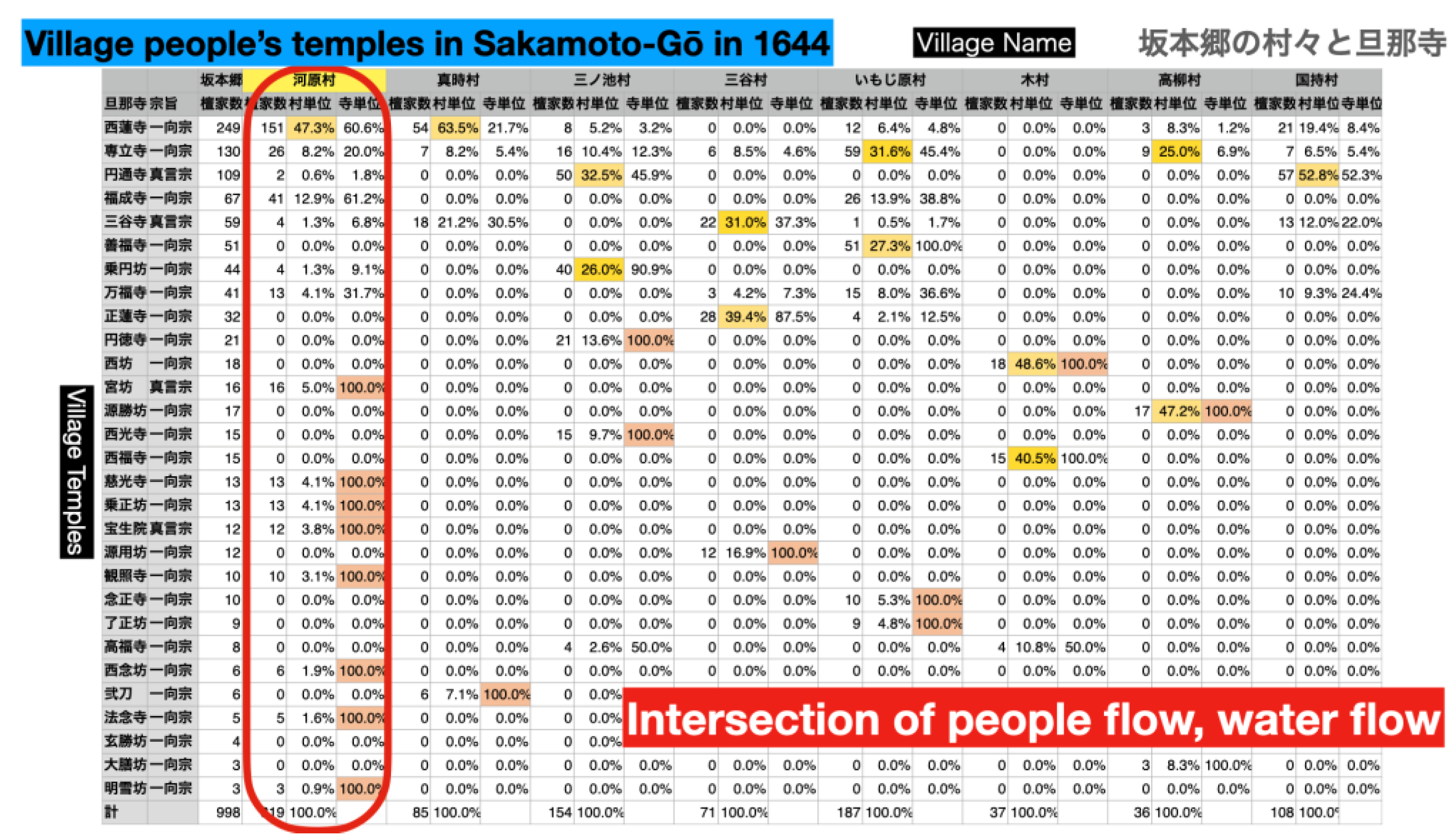

The historical document discussed here is a valuable early record book from 1644 (Shūmon-chō of Sakamoto-gō, 1644). Throughout Japan, people were forced to trample on statues of Mary in February, March, or April to prove that they were not Christian. In any case, individuals were recognized as residents only after proving their affiliation with a particular Buddhist temple. The priests of each temple provided proof.

This historical document is from the early stages of the Shūmon Aratame-chō, a pivotal text in the study of historical demography in Japan (Hayami, 1986, 2003). It is extremely valuable because it dates from the earliest period of production of this type of historical material. The discovery of its survival in this area was also the starting point of this article.

The Shūmon Aratame-chō, also known as the Shūmon Ninbetsu Aratame-chō (Religious Population Register), was a document that the Edo shogunate required each village to prepare in order to enforce the prohibition of Christianity. Once a year, Buddhist temples required everyone to prove that they were not Christian because the people being investigated were members of a Buddhist temple. Initially, this was only done in the shogunate's domain, but starting in 1671, clans throughout Japan were required to produce this register in approximately 63,000 villages. The documents were made annually in principle, although this varied depending on the time of year and the region. They contained the names and ages of the head of the household and his or her family, as well as information on the temple to which the residents belonged.

In the early Shūmon Aratame-chō, the unit of record sometimes included several dozen people. The largest unit of record in the books analyzed in this article included 108 people. The number of houses in that unit and the total taxable income were also listed. This measurement symbolizes Japan as a rice society and was recorded in terms of rice quantity.

Although the term "household" is in question, it is proven which Buddhist temple each listed unit belonged to. In the 1644 Shūmon Aratame-chō compiled in Sakamoto-gō, not only is the "household" stated, but also the number of houses and total income subject to taxation for each unit of entry, all in terms of rice. For simplicity's sake, one Koku (150 kg of rice) is considered the equivalent of one year's sustenance for the population as a whole. A quantity of 100 Koku is considered sufficient income and property for 100 people to live on and pay taxes. In fact, the record of Kawahara village in Sakamoto-gō shows that a household of 108 people could be described as a single business entity with over 190 Koku in total. This quantity is significant because usually, even 10 Koku is a large farmhouse. It is clear that this is an exceptional group.

The PRs are a prominent feature of the Sanuki landscape. Even if they originated in ancient times, it makes sense that they were built to address the area's long-term drought due to low rainfall. The argument that they were built using forced labor in premodern times ignores historical reality. The mobilization of people must have its own logic that works within a specific time and place. Religious motivations may drive people to enthusiasm, or a practical need to secure food for the people may exist. It may also be an increase in productivity that allows politicians to collect taxes to finance their political entities.

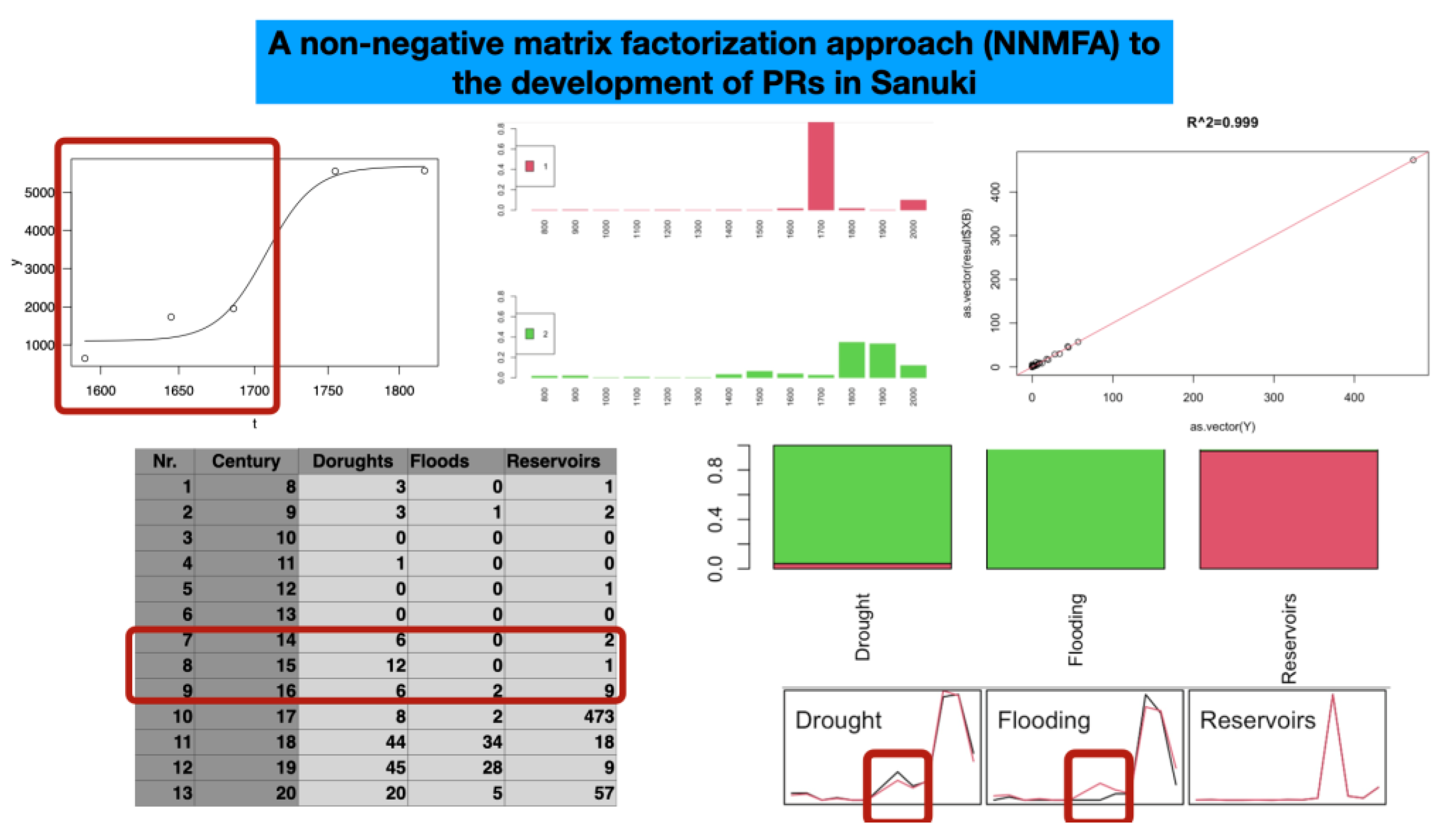

There are historical records of PR construction since ancient times, as well as records of floods and droughts in Sanuki. The author analyzed these figures using a soft-clustering approach called Non-Negative Matrix Factorization (NNMF) (Satoh, 2024). The specifics of this approach are discussed in the following chapters. The author also used other methods, such as analyzing the distribution of reservoir size, estimating development stages by fitting logistic curves, and Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis. This analysis considers the flow of residents from the perspective of the labor force and workload. This approach provides a multidimensional view of the long-term history of PRs and takes a holistic approach.

In recent years, quantitative historical research on Japan has dramatically progressed in terms of population (Saito, 2018), economic indicators (Takashima, 2017, 2023), precipitation (Nakatsuka, 2022), and other long-term factors. This article is one such attempt, focusing on PRs as objects that shape a place's cultural landscape. The author believes this approach will present new challenges in long-term historical research.

4. Results

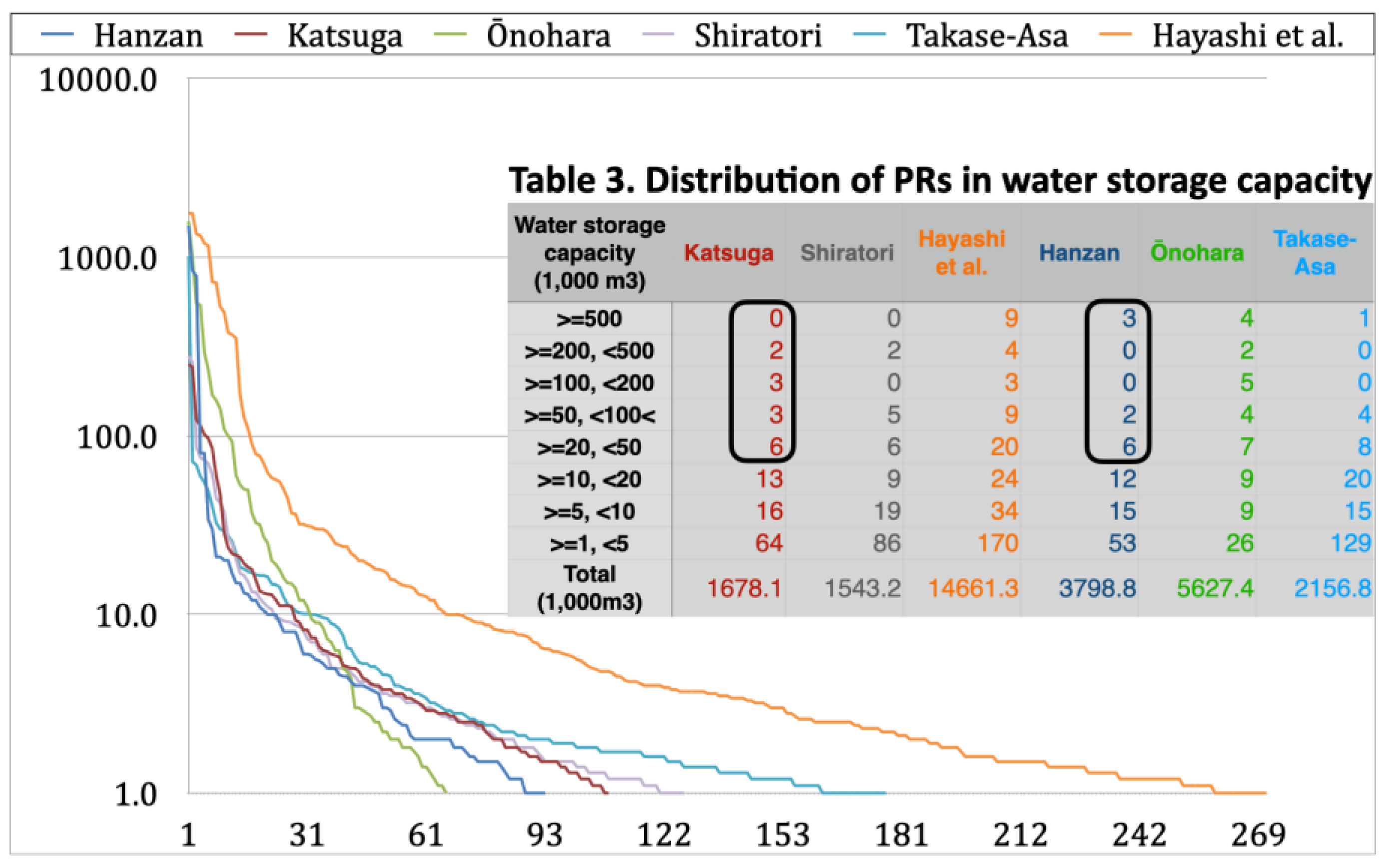

4.1. Rank-Size Distribution of PRs

Unlike microhistorical research, which is driven by the history of individual events due to the variety of historical developments, macrohistorical research can reveal things through aggregation. For instance, identifying hundreds of PRs in each area through the distribution of water storage capacity reveals the characteristics of each area. In such cases, attention should be paid to the presence of large PRs and the relative proportions of smaller PRs. Selecting six regions from the entire Sanuki reveals a particularly striking difference in the ratio of small PRs (

Figure 1). This difference is in the proportion of PRs that can be managed by one or a few families. Conversely, when comparing the Katsuga and Hanzan regions, the differences between small PRs are minimal, but the differences between large PRs are significant.

Hanzan (Hanzan Chōshi 1988) is located on the Marugame Plain. There are PRs in Hanzan, such as Kusumi-ike, which utilizes the mountainous area. However, the large PRs built on the plains are also characteristic (

Figure 2). Some of the large PRs in Hanzan were constructed in the 16th and 17th centuries. These include Ni-ike, Kusumi-ike, and Ōkubo-ike. They have a water storage capacity of over 700,000 cubic meters. Kusumi-ike has a capacity of 783,000 cubic meters. Ōkubo-ike has a capacity of 843,000 cubic meters. Ni-ike has a capacity of more than 1.5 million cubic meters. For this reason, managing the PRs required the cooperation of more than ten villages. In contrast, the largest PR in the Katsuga region, Kandaka-ike, has a capacity of only 251,400 cubic meters.

Table 3, which is quantified by PRs storage volume, shows striking differences between the Katsuga and Hanzan regions. However, this is not clearly visible in the rank-size distribution graph (

Figure 2). In the Hanzan region, there are three large PRs and almost no medium-sized PRs. There is a significant difference in the management and maintenance of PRs. In other words, even though water scarcity is a universal phenomenon, regional differences arise in how it is addressed. Although topographical-geological factors play a major role, differences in hydro-climatological factors, such as river and weather conditions, need to be clarified.

4.2. The NNMFA to a Logistic Curve Fitting of PRs

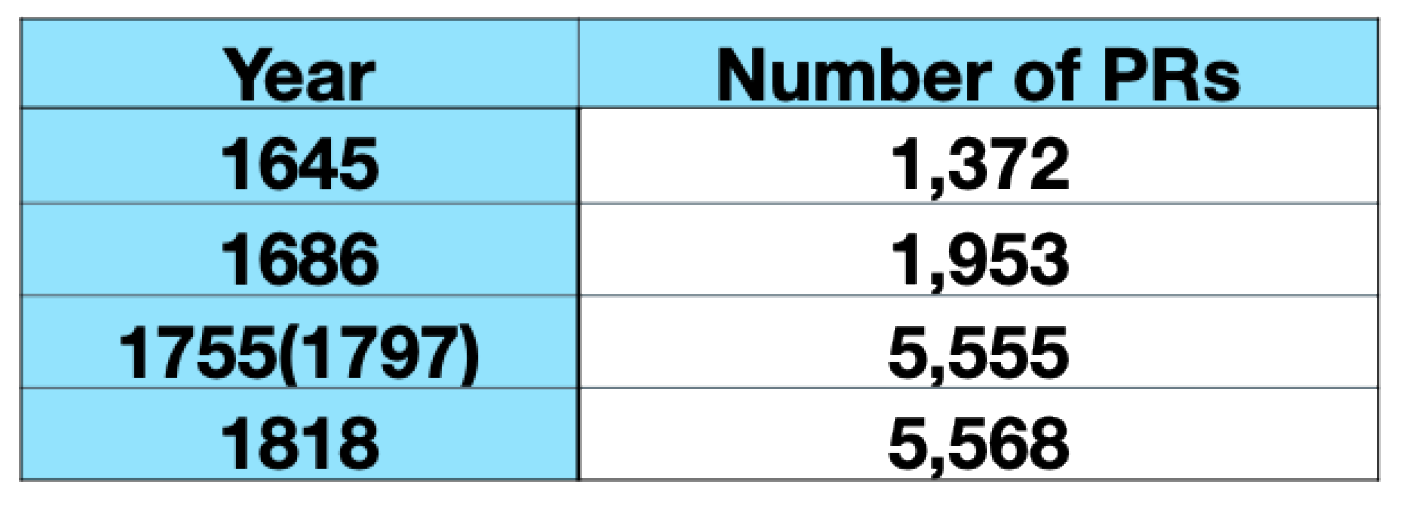

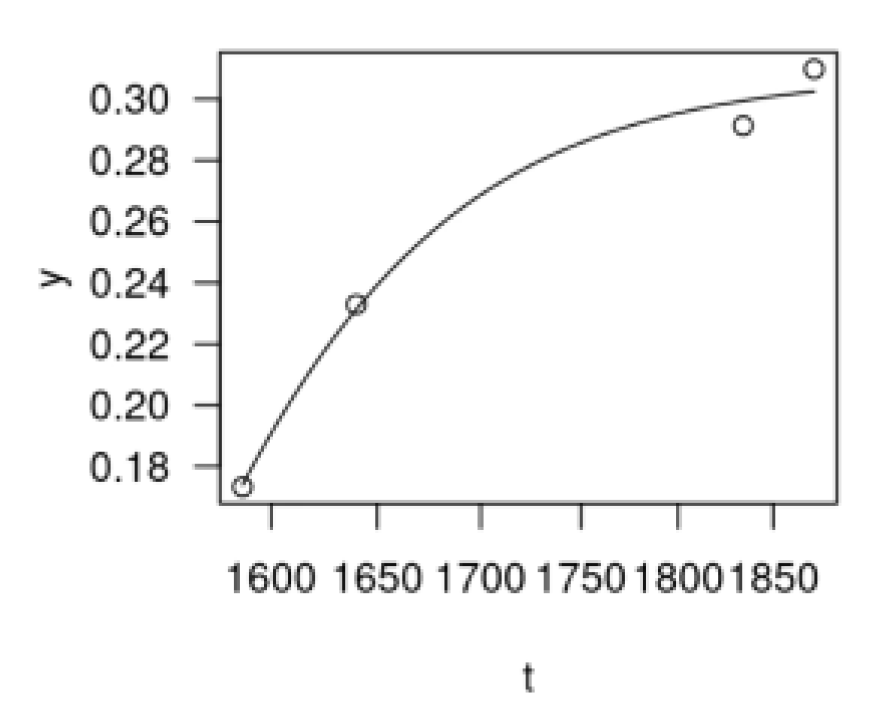

There are limited figures on the number of PRs: There were 1,372 in 1645, 1,953 in 1686, 5,555 in the late 18th century, and 5,568 in the early 19th century. These numbers are only available for the eastern half of Sanuki. These numbers vary from one source to another. The mid-18th-century numbers are the result of decades of early modern investigations of each PR. Here, the figures are taken from 1755. Various physical quantities are said to follow a logistic curve. Logistic curve-fitting analysis has been proven effective for population analysis when sufficient data is unavailable (Saito, 2018).

Table 4.

Number of PRs in early modern times.

Table 4.

Number of PRs in early modern times.

The growth curve for this PR analysis can also be obtained by applying these four figures. There is a marked increase from the end of the 17th century onwards, followed by a gradual convergence of the growth rate in the second half of the 18th century. While the growth curve appears reasonable, the Takamatsu domain's economic size had already grown rapidly, increasing from 173,300 koku in 1587 to 232,948.93 koku in 1640 and further rising to 307,602.83 koku in 1872. If these figures are applied to the logistic curve, however, the result is shown in

Figure 3. , it can be inferred that the original increase in economic volume likely occurred before 1600. If PRs were built to avoid drought and lead to economic growth, this would not be a problem. However, this does not appear to be the case.

Historical research has attributed the beginning of PR construction to the Buddhist monk Gyōki (668–749) and his group during the Nara period (710–794). Another famous Buddhist monk, Kūkai, is credited with restoring the largest PR in Sanuki a little later. Though there are few references to this in the medieval period, many PRs are said to have been constructed in the early modern period by individuals such as Hachibei Nishijima (Sanuki no Tameike-shi, 2000, 1483–1488) and Heiroku Yanobe (Sanuki no Tameike-shi, 2000, 1489–1493). Nishijima is said to have constructed more than 90 large PRs in the 14 years from 1625. Yanobe built 406 PRs in response to the unprecedented drought of 1645, bringing the total to 1,366, including the original 960 PRs. (Hanzan Chōshi 1988, 296).

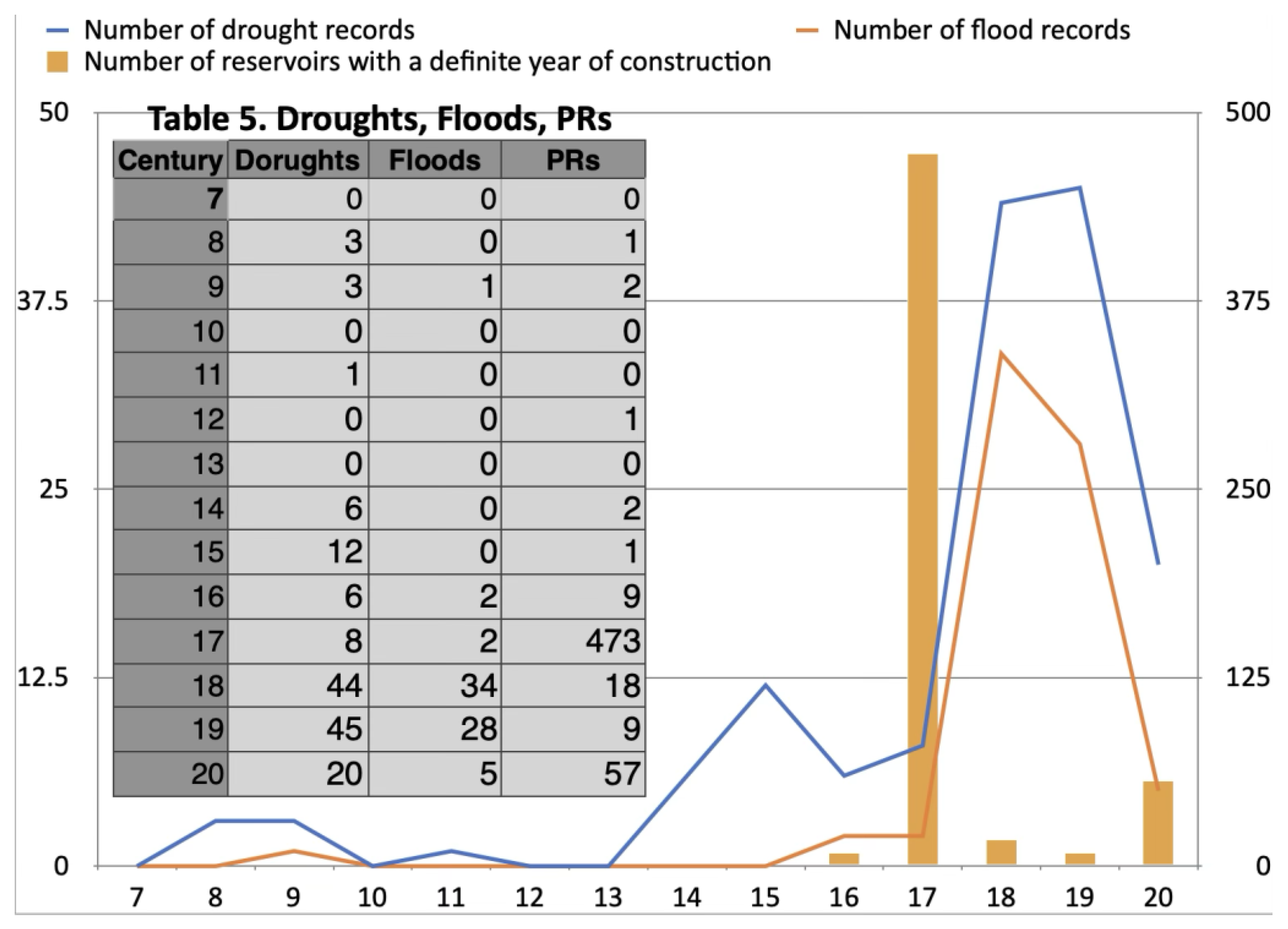

Additionally, the Sanuki no Tameike-shi (2000) collects data on past droughts and floods since ancient times (

Figure 4/Table 5), as well as the years in which the PRs were constructed from the 8th century onwards. Table 5 shows that 473 PRs were constructed in the 17th century, and their dates of establishment are recorded. How can we understand the relationship between the PRs and the drought and flood data? It is generally accepted that the construction of PRs was triggered by drought, as evidenced by the written historical record. However, why were droughts and floods recorded in the first place, and what is the significance of clearly stating the year of construction for PRs?

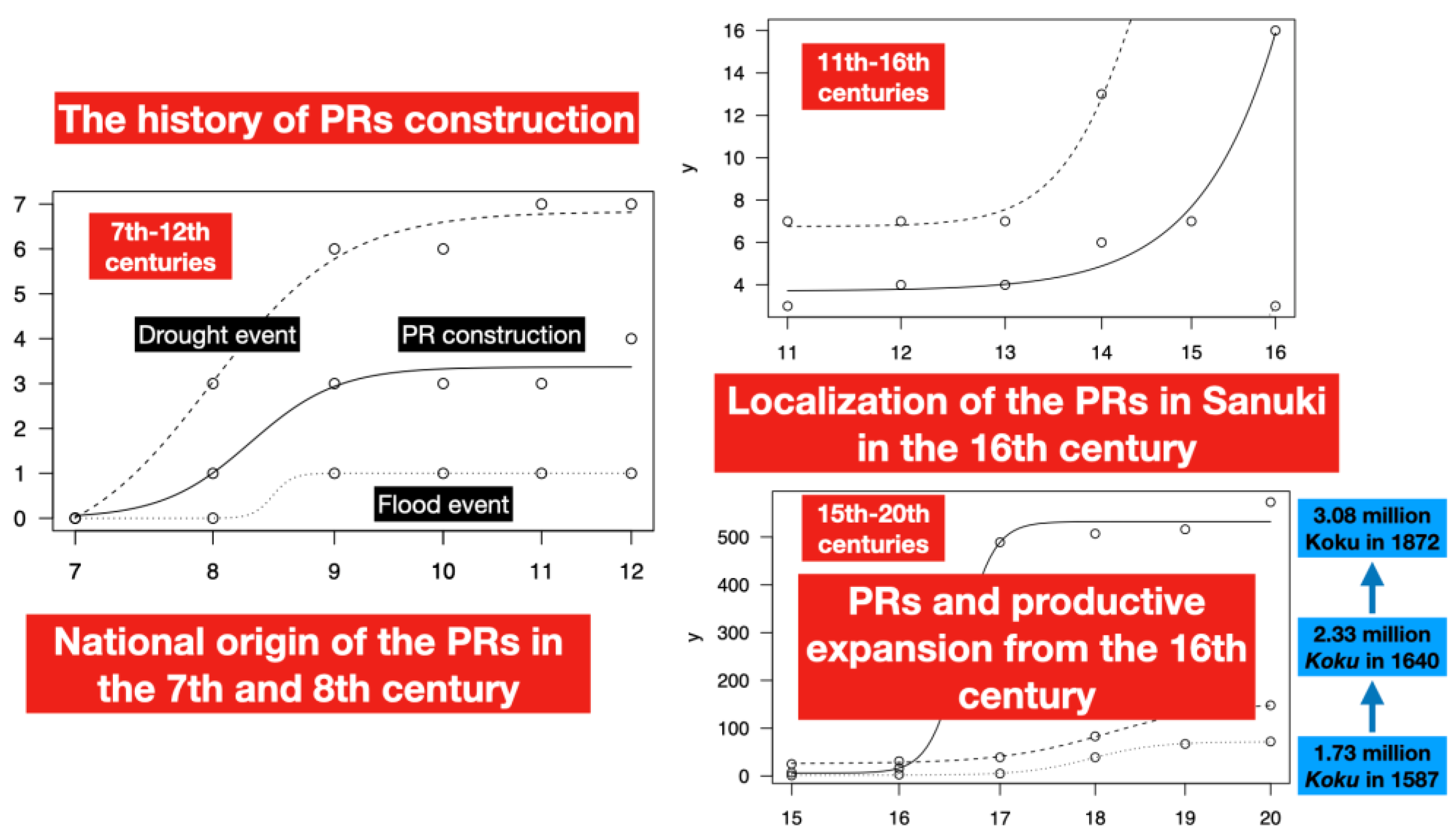

The issue at hand is the relationship between accumulated experience with droughts or floods and the construction of PRs. The author used a non-negative matrix factorization (NNMF) for 1,400 years of drought and flood records, as well as the number of PRs whose construction years are known. The author does not believe there is enough space to provide further technological detail here. The result is an interesting difference in the historical patterns of the three numbers. The results depict that droughts, floods, and PRs have different underlying logics, i.e., basic trends over the past 1,400 years.

The development of a particular element seems to follow a logistic curve to a significant degree. However, it cannot be said that PRs were developed directly from ancient ideas or constructions to the present day. The primary response to water scarcity is the bass note, and one could argue that the concept has been combating water scarcity since ancient times. However, this would be inaccurate. There was a period when the local situation clearly forced a response to water scarcity. This response probably occurred in the 16th century when drought records clearly increased.

In this respect, the method used here is not logistic curve fitting analysis, but rather, NNMFA. NNMFA models how a few basic factors influence the development of a time series, revealing trends close to real numerical information. In other words, this method clarifies the multiple development paths seen throughout history. Here, the logic of creating PRs is contrasted with the logic of recording droughts and floods. The logic behind recording droughts is to prevent starvation due to withering plants and trees.

However, it is distinct from the logic of PR construction. Building a PR cannot be done by one person alone. A few families may be able to do it, though. In many cases, though, it requires collaboration, producing struggling actors in terms of interests. The commons are precisely within the logic of struggle. Of particular interest, based on observations of the Sanuki PRs, is the record of droughts in the sixteenth century. During the Warring States period, PR construction progressed beyond individuals and families to include small groups of local units. This gave rise to the era of rapid PR construction that followed. In this sense, the eighteenth century was the age of PR construction, but it was a legacy of an earlier age.

Figure 5.

A result of a NNMFA to PRs development in Sanuki Source: Original dataset (see Appendix).

Figure 5.

A result of a NNMFA to PRs development in Sanuki Source: Original dataset (see Appendix).

The idea that PRs were created due to a lack of water is overly simplistic. The focus is on the sixteenth century. However, there is a gap in Japanese historical sources. Additionally, there is a disconnect between the content of the early modern period and earlier periods. The issue of continuity and disconnection in historical sources is complex, and the Living Spaces Approach could be effective. In other words, the historical logic of each record of drought or flooding and each dated PR construction is unique.

Note that the vertical axes of the three graphs in

Figure 6 have different scales, but they show that, in ancient times, when PRs were first constructed in the Kinki region of central Japan, information about droughts gradually became important in the Sanuki region as well. The solid line shows the development trend of PR construction; the dashed line shows the record of drought events, and the dotted line shows the record of flood events. Flood records may have been insignificant in ancient times and the Middle Ages. In contrast, there was a gradual increase in drought and flood records from the sixteenth century onwards, but this gradually subsided. At the same time, the boom in PR construction also subsided after the seventeenth century. The early modern period, when clan leaders made efforts to build PRs, was a boom period for PR construction in clan society, which began dramatically in the sixteenth century.

One development trend can be identified by looking at the number of PRs. However, drought data suggest three phases since antiquity. Flooding is a relatively modern phenomenon that only affects human-made landscapes. In contrast, drought provides opportunities for human activities such as building PRs and constructing waterway networks.

Extending this discussion further into antiquity, these two phases should be considered as two initial points in time. This is because records of drought, famine, and other events began to be kept in historical documents at the same time as the construction of the PRs. The Kinki region, the center of the ancient period, leads in the accumulation of such records. The Sanuki region is also linked to the study of droughts in central Japan. This is why Kūkai constructed the largest PR in Sanuki, as mentioned above. However, the details of this construction are not well documented (Sanuki no Tameike-shi 2000, 1469–1476).

In conclusion, the history of PRs can be divided into three phases over a period of 1,400 years. These phases include the overlapping centuries of the seventh to twelfth, eleventh to sixteenth, and fifteenth to twentieth. The second phase involved the construction of PRs in the advanced Kinki region, which took root and spread to Sanuki. This was followed by the third, final phase, during which large numbers of PRs were constructed alongside economic expansion.

4.3. People Flow and PRs

The final section is a study of a historical document from 1644 focusing on labor. It is a type of resident registry that reveals significant migration, technological innovation, and family structure issues related to the mountainous area of Kusumi-ike in PR.

While some households with a few members are common, larger households existed, including one with 108 members. However, the term "household" may not be the correct one (Nishitani, 2021; Saito, 2022). However, it is a registered unit. This group is believed to have played a central role in constructing, extending, and managing the "communized" PR in Sakamoto-gō, Kusumi-ike.

In early modern villages, the amount of rice that each household received as Kokudaka was weighed and measured. This quantitative decision determined the household's tax burden, meaning the property and income that would be taxed. In this case, the group of one hundred and eight "household" members who managed Kusumi-ike showed a Kokudaka that would be unthinkable for an average peasant. The household unit of Densuke has 108 members and a tax burden of 190 Koku, which is equivalent to the annual income of 190 household members.

Each household is affiliated with a specific temple. For example, in ancient times, there was a group of water-related developers led by a monk named Gyōki. Mannō-ike, the largest pond in Sanuki, is attributed to the renowned monk Kūkai. Was the Buddhist community the source of a group of workers, engineers, and prayer groups?

The one hundred and eight people under Densuke, including himself, form a modern-day composite of several conjugal households. Densuke and his family belong to the Miya-no-Bō temple of the Shingon sect of Buddhism. It could be called a family temple. The family consists of 16 members, including Densuke's wife; three couples from the next generation, including their children; Densuke's 76-year-old mother; and a 55-year-old male servant. It is a three-generation family.

Table 6.

Village people’s temples and people flow.

Table 6.

Village people’s temples and people flow.

The village of Kawahara in Sakamoto-gō appears to consist of many migrants. 47.3 percent of Kawahara's inhabitants belong to Shōren-ji, a Jōdo Shinshū temple in a neighboring village. While many other villages have villagers who belong to one or two central temples, Kawahara has a very high proportion of families with their own temples. In other words, most of the villagers are migrants, and it is reasonable to assume that the village developed around Kusumi-ike as a settlement of migrants. Did family members migrate as a group? Even so, individual households usually secured more koku than expected. It is likely that a group of people were directly involved in creating and expanding Kusumi-ike, though there is no proof. However, it is certain that they were one of the groups that benefited from the PR's irrigation.

This final analysis could provide one last point of clarification. While the location of a PR is specific, it is not only the local inhabitants who play an important role in its construction, maintenance, or extension. In premodern societies, a more mobile group may have played a greater role. This was also the case in ancient times. Gyōki and Kūkai were highly migratory people who eventually established their own bases. PRs store water, but the Asian monsoon must also be considered in terms of water flow and the mobility of human populations. Local histories are not just local histories.

5. Concluding Remarks

While it is generally true that PRs were constructed due to the area's low rainfall, many issues are overlooked in the decision-making process regarding the environment. Ultimately, it all boils down to this simple logic. The seasonality of rainfall in this area allows for the timing of PR construction and renovation, which can be linked to the seasonality of rice production. In the premodern era, more labor was required to build, maintain, and renovate PRs than was initially thought. Consideration must be given to the social systems that made this process possible: Did Buddhist monks, village autonomy, or the power of a specified family make it possible?

The rank-size distribution of PRs varies according to the characteristics of each site. It can be understood by the proportion of areas where larger PRs are present, as well as the proportion of smaller PRs. Based on the development of PRs as a logistic curve according to the NMMFA, the long-term history of PRs spanning 1,400 years from ancient times to the present day is divided into three periods: 1) the seventh to twelfth centuries, 2) the eleventh to sixteenth centuries, and 3) the fifteenth to twentieth centuries, including transitional centuries.

Regarding the flow of people and the development of logistic curves of PRs in Sanuki, the location of PRs is specific, but not only local inhabitants played an important role in their construction, maintenance, or extension. In premodern societies, a more mobile group may have played a greater role. This was also the case in ancient times with Gyōki and Kūkai.

In fact, the study is not yet complete. Lastly, new hypotheses and questions could be presented.

1. The national project of building huge PRs since ancient times indicates a top-down approach that engages the religious public through practical Buddhist monks and the emperor.

2. However, the decisive change occurred during the Warring States period (Takagi, 2023). Powerful clans continued the top-down approach, producing new living spaces.

3. The struggle for the commons, including PRs, turned into a water struggle. Efforts to increase rice production focused solely on premodern economism in small-scale farming operations. This approach was fundamentally different from the path of pre- and modern economism in Europe, which was based on coal mining (Wrigley, 2016).

4. In the 20th century, a state capitalist project ended the history of PRs as commons originally related to Buddhist monks. Now, many people living there are no longer involved with water in nearby PRs.

A long-term socio-hydrological history: Practical Buddhist religion, together with state power, created "Living Spaces" of PRs. Through wars of deprivation, these spaces turned into peaceful competition at the beginning of the early modern period in the 15th century. After the latter half of the Tokugawa period, especially in the 19th century, the gap between the wealthy and the poor expanded enormously. Eventually, state capital and public water management, which cannot be described here, seem to have erased the value that sustains all life. The long-term localization period of the PRs will likely end. What should come next? This is one of the author's future challenges.

Funding

This research was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research; Kaken Kiban-B (20H01523); Kaken Kiban-B (23H01661/23K26355); Core-to-Core Program (JPJSCCB20230002), JSPS/MESS Bilateral Program (2019-2022; 2023-2025), the Research Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Kyoto University, the International Research Center for Japanese Studies (Nichibunken), the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN), and the International Consortium for Earth and Development Sciences (ICEDS), Kagawa University. Based on these funds, the author has also made presentations at many international conferences. Recently, the author gave an invited talk at the 2nd International Sociohydrology Conference (19-21 July 2025, Tokyo, Japan) and presented a part of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| JSPS |

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science |

| NA |

Not Available |

| PR |

Pond and Reservoir |

| PRs |

Ponds and Reservoirs |

| NMMFA |

Non-Negative Matrix Factorization Approach |

Appendix A

Dataset for PRs in Sanuki (Original dataset)

This is an Excel file that originally organizes information on the construction dates and statistical data of ponds and reservoirs (PRs) and historical records of droughts and floods, mainly based on data from Sanuki no Tameike-shi 2000.This excel file has two worksheets, one for compiling records of droughts and floods, and the other for PRs. Tomohiro Murayama of the ICEDS at Kagawa University digitized an original dataset from written materials, from which this selected document was compiled. The author would like to express his gratitude to Tomohiro Murayama for his assistance. It can be accessed from the link below:

References

- (Fujihara ed. 2023) Fujhara, T., ed. Handbook of Environmental History in Japan (Handbooks on Japanese Studies, Amsterdam University Press, 2024 (online, print publication year, 2023).

- (Hanzan Chōshi 1988) Hanzan Chōshi Hensan Iinkai [The Committee of Hanzan Chōshi] ed., Hanzan Chōshi [History of Hanzan-chō].

- (Hayami 1986) Hayami, A. 1986. A great transformation: Social and economic change in sixteenth and seventeenth century Japan. Bonner Zeitschrift für Japanologie, 8, 3–13.

- (Hayami 2003) Hayami, A. 2003. Sangyo Kakumei tai Kinben Kakumei [The Industrial Revolution vs. The Industrious Revolution]; In Kinsei Ni-hon no Keizai Shakai [Economic Society of Early Modern Japan]; Reitaku University Press: Tôkyô, Japan; pp. 307–322.

- (Murayama and Nakamura 2021) Murayama, S.; Nakamura, H. 2021. “Industrious Revolution” Revisited: A Variety of Diligence Derived from a Long-Term Local History of Kuta in Kyô-Otagi, a Former County in Japan. Histories, 1(3), 108-121. [CrossRef]

- (Murayama 2025) Murayama, S. 2025. An Introduction to the Living Spaces Concept. Pp. 9-28 in (Murayama et al. 2025) Changing Living Spaces. Subsistence and Sustenance in Eurasian Economies from Early Modern Times to the Present. https://www.hippocampus.si/ISBN/978-961-293-399-9/7-28.pdf.

- (Murayama et al. 2025a) Murayama, S., Z. Lazarevic, and A. Panjek, eds. 2025. Changing Living Spaces. Subsistence and Sustenance in Eurasian Economies from Early Modern Times to the Present, Slovenia Scientific Series in Humanities, 12, Koper: University of Primorska Press. ISBN 978-961-293-399-9 | PDF; ISBN 978-961-293-400-2 | HTML. [CrossRef]

- (Murayama et al. 2025b) Murayama, S., H. Nakamura, N. Higashi, and T. Terao. 2025. Agricultural Crises Due to Flood, Drought, and Lack of Sunshine in the East Asian Monsoon Region: An Environmental History of Takahama in the Amakusa Islands, Kyushu, Japan, 1793-1818. [CrossRef]

- (Nagamachi 2013) Nagamachi, H. 2013. Sanuki no Tameike Bunka to Kagawa Yousui: Kinsei Tameike Suiri no Hattatsu [Sanuki's Ponds and reservoirs culture in Sanuki and Kagawa Waterway: Development of irrigation management in the early modern period], Mizu to Tomoni [With Water] (Mizu Shigen Kikou [Japan Water Agency]), 9, 10-13.

- (Nakatsuka 2022) Nakatsuka, T. 2022. Kikō Tekiou no Nihon-shi. Jin-Shin-Sei wo Norikoeru Shiten. [The History of Climate Adaptation in Japan: Perspectives for Overcoming the Anthropocene.] Yoshikawa Kobunkan.

- (Nishitani 2021) Nishitani, M. 2021. Chūsei wa Kaku-Kazoku dattanoka. Minshū no Kurashi to Ikikata [Was the Middle Ages a nuclear family? The lives and lifestyles of the common people.] Yoshikawa Kobunkan.

- (Rinsen Shoten 2020-21) Nakatsuka T. et al. eds, Kikou Hendō kara Yominaosu Nihon-shi [Rereading Japanese History form the Perspective of Climate Change. Rinsen Shoten, 6 volumes.

- (Saito 2018) Saito, O. 2018. 1600-nen no zenkoku jinkō. 17 seiki jinkōkeizaishi saikōchiku no kokoromi [Japan’s population in 1600: An attempt to reconstruct the history of population and economy in the seventeenth century]. Shakai-Keizaishigaku [Socio Econ. Hist.], 84, 3–23.

- (Saito 2022) Saito, O. 2022. Chūsei Nihon wa donoyōna imi de kaku-kazoku shakai dattanoka: Chien-kyōdōtai, shinzoku-shūdan, yashiki-chi [In what sense was medieval Japan a nuclear family society? Local community, kinship, farm-family compound], Syakai-keizai shigaku [Socio-Economic History], 88(3), 51-66.

- (Sanuki no Tameike-shi 2000) Sanuki no Tameike-shi Hensan Iinnkai 2000. [Topography of Ponds and Reservoirs in Sanuki] ed., Sanuki no Tameike-shi [Topography of Ponds and Reservoirs in Sanuki], Gyōsei.

- (Satoh 2024) Satoh K. 2024. Applying Non-negative Matrix Factorization with Covariates to the Longitudinal Data as Growth Curve Model. [CrossRef]

- (Shūmon-chō of Sakamoto-gō 1644) “Kan-ei Nijū-ichi Nen Ichi-gatsu Uta-gun Sakamoto-gō Kirishitan Shūmon-On-Aratamechō” [Religious Register of Sakamoto-go in 1644] A. Takamatsu City Historical Museum Collection: A copy in April 1924, owned by Senzō Miyake, B: Kamata Kyōsai-kai Local History Museum Collection, owned by Takahiko Mitani, C: A reprinting of the historical materials of B in Kagawa-ken Hensan [Kagawa Prefecture, ed.], Kagawa Ken-shi [History of Kagawa Prefecture] Dai Jyukkan [vol. 10], Kinsei-Siryō-hen II [Pre-modern historical materials II], 1987, 5-47.

- (Takagi 2023) Takagi, H. 2023. Sengoku Nihon no Seitai-kei: Shomin no Seizon-senryaku wo Fukugen Suru [The Ecosystem of Warring States Japan: Reconstructing the Survival Strategies of the Common People] Kodan-sha Metier.

- (Takashima 2017) Takashima, M. 2017. Keizai Seichô no Nihonshi. Kodai kara Kinsei no Chōchōki GDP Suikei, 730–1874 [Economic Growth in the Japanese Past: Estimating GDP, 730–1874]; University Press: Nagoya, Japan.

- (Takashima 2023) Takashima, M. 2023. Chingin no Nihon-shi: Shigoto to Kurashi no 1500 nen [A History of Wages in Japan: 1,500 Years of Work and Life] Yoshikawa Kobun-kan.

- (Totman 2014) Totman, C. 2014. Japan. An Environmental History.I.B.Tauris & Co.Ltd, London/New York.

- (Wrigley 2016) Wrigley, E.A. 2016. The Path to Sustained Growth: England’s Transition from an Organic Economy to an Industrial Revolution. Cam-bridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

- (Yoshikawa Kobunkan 2012-3) Hirakawa, M., Miyake, K., Ihara, K., Mizumoto, K., and Torigoe, H. eds. Series: Japanese History of the Environment, Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 5 volumes.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).