Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

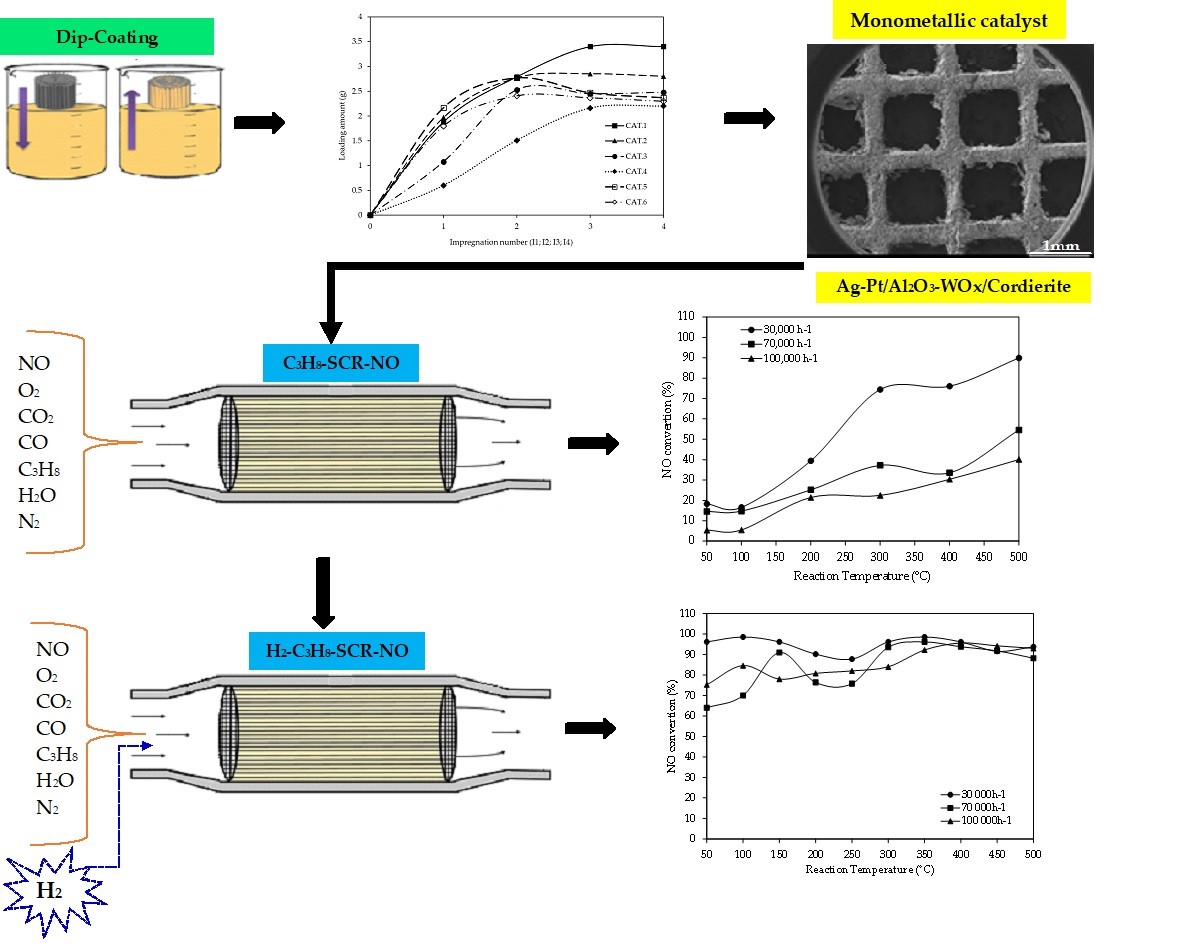

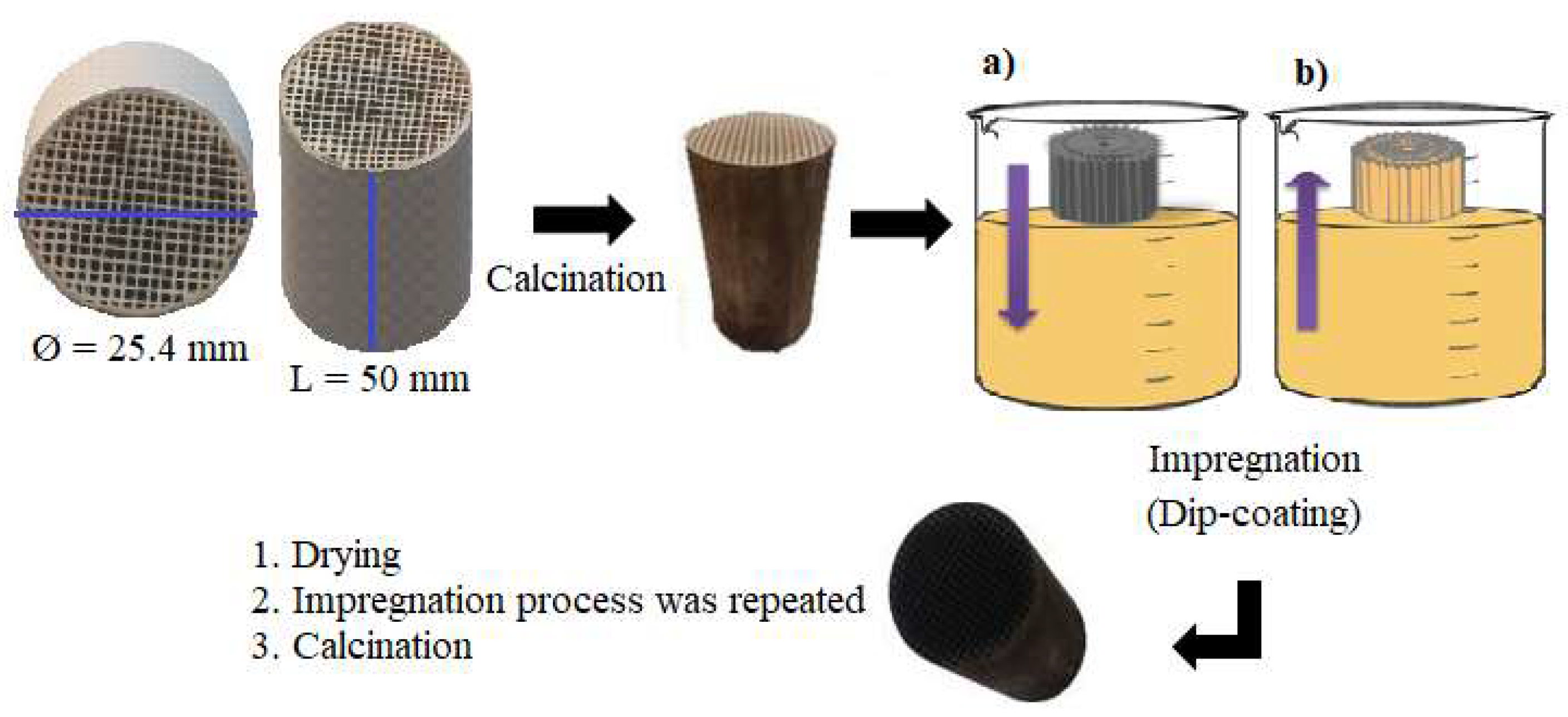

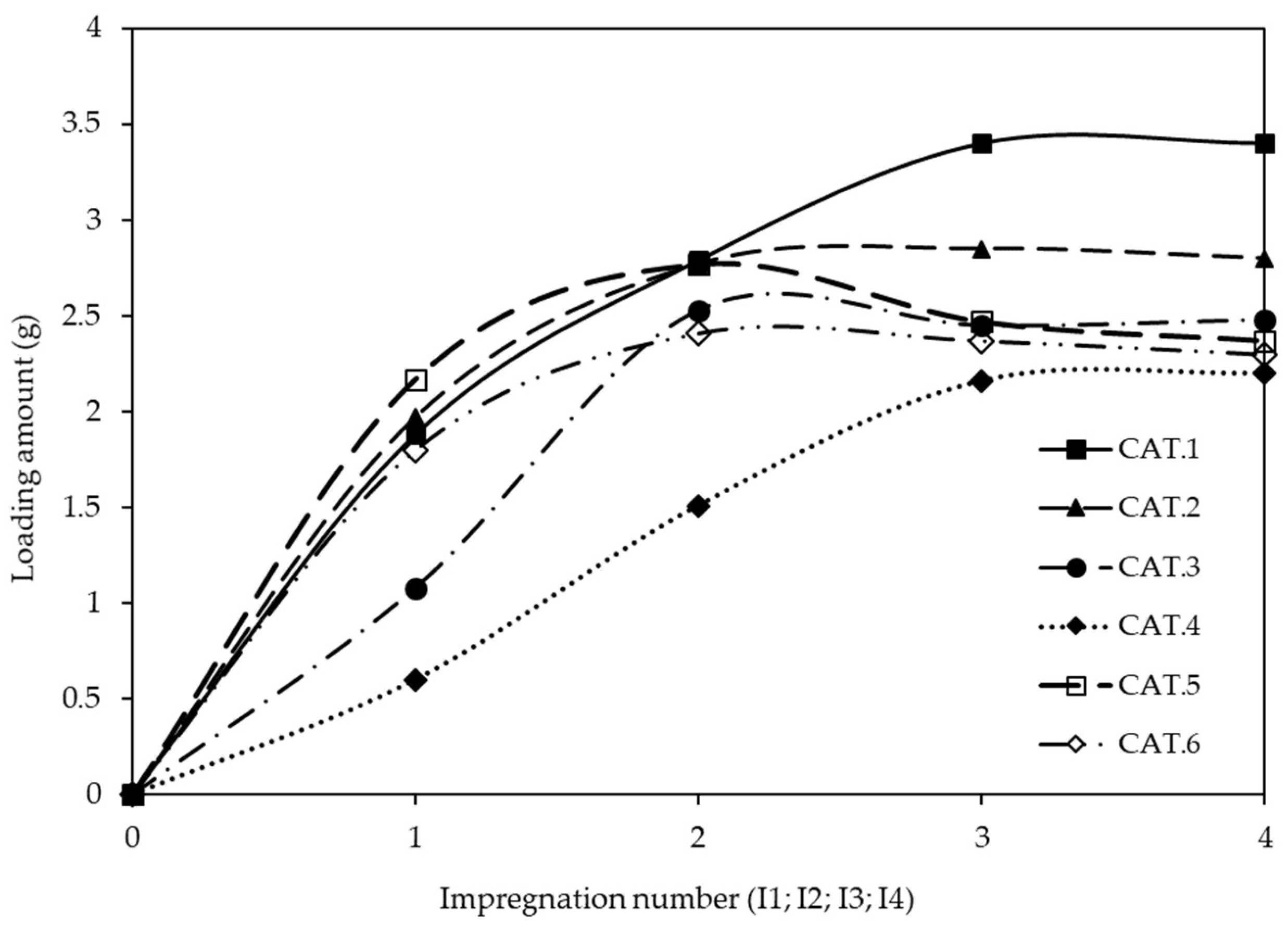

2.1. Synthesis of Structured Catalyst

2.2. Synthesis of Powder Catalysts

2.3. Characterization

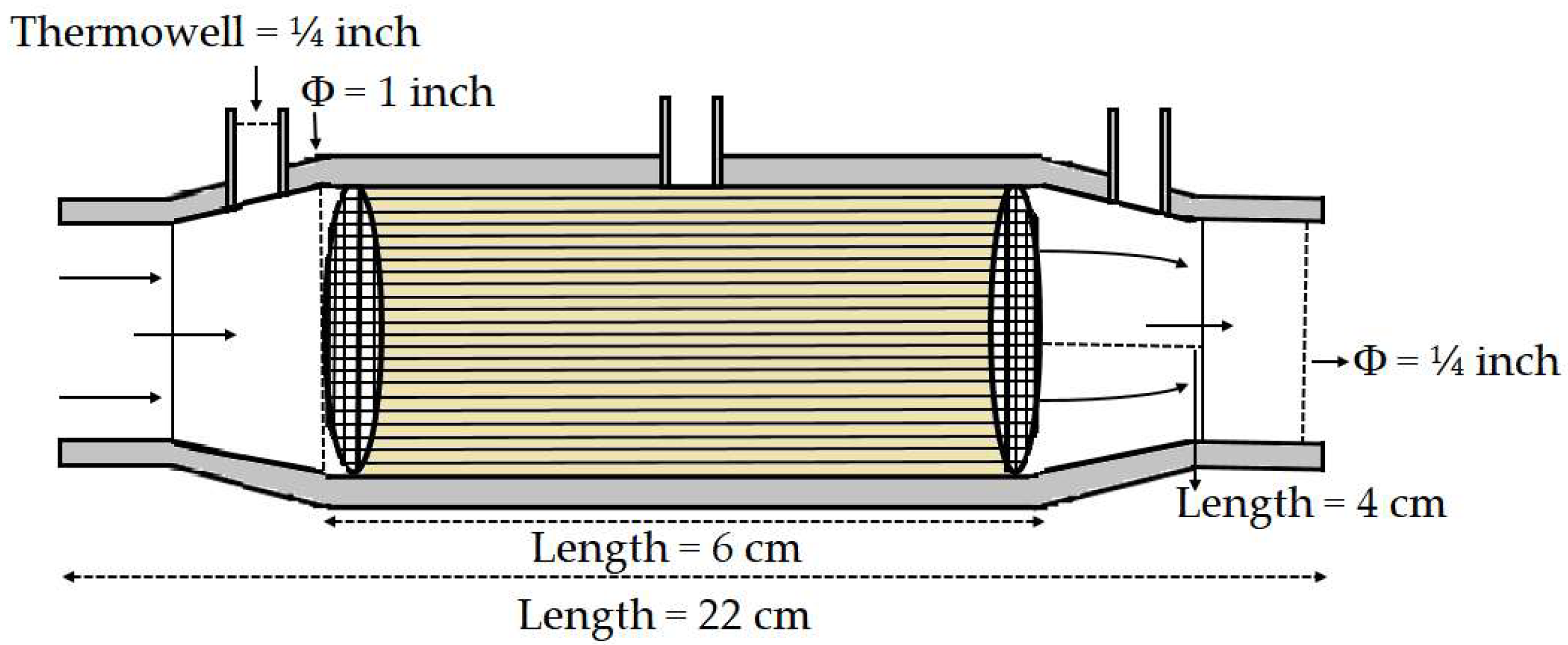

2.4. Catalytic Tests

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization

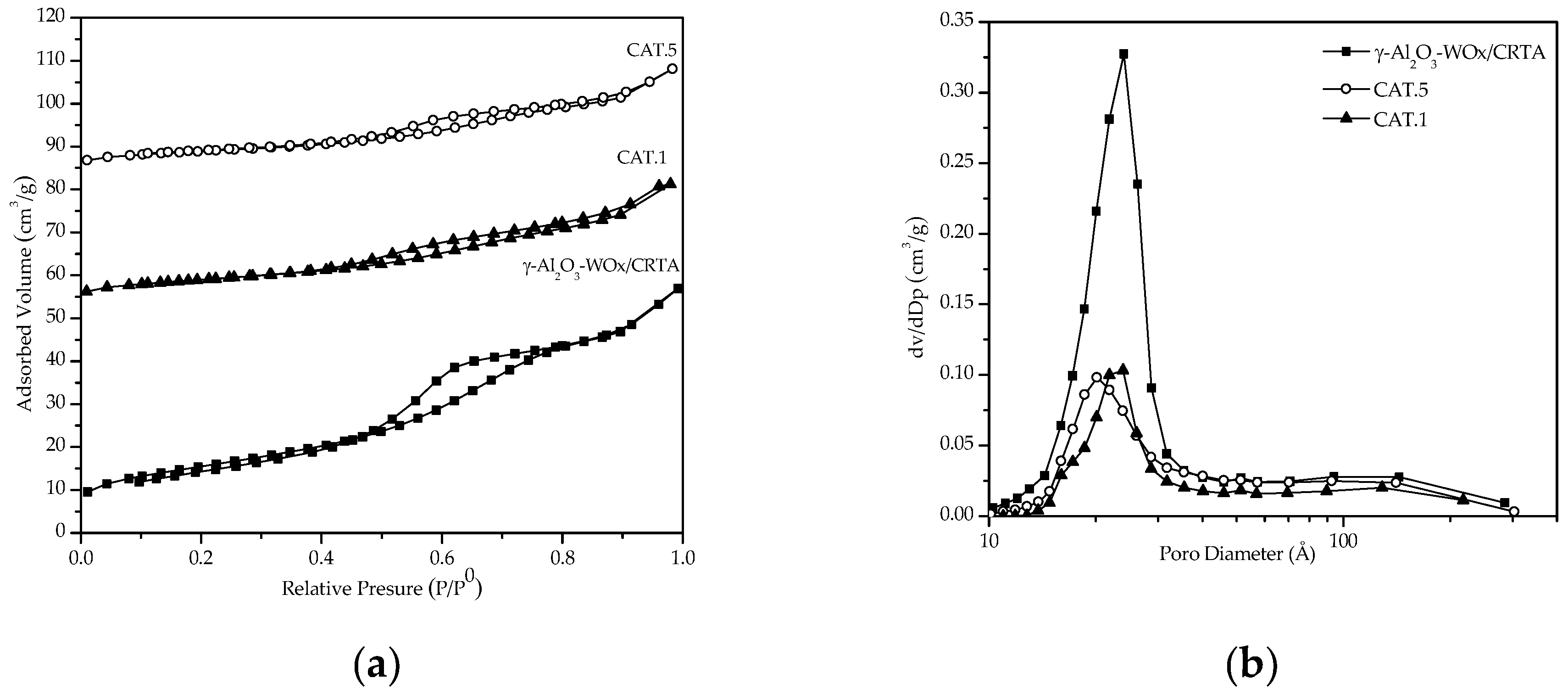

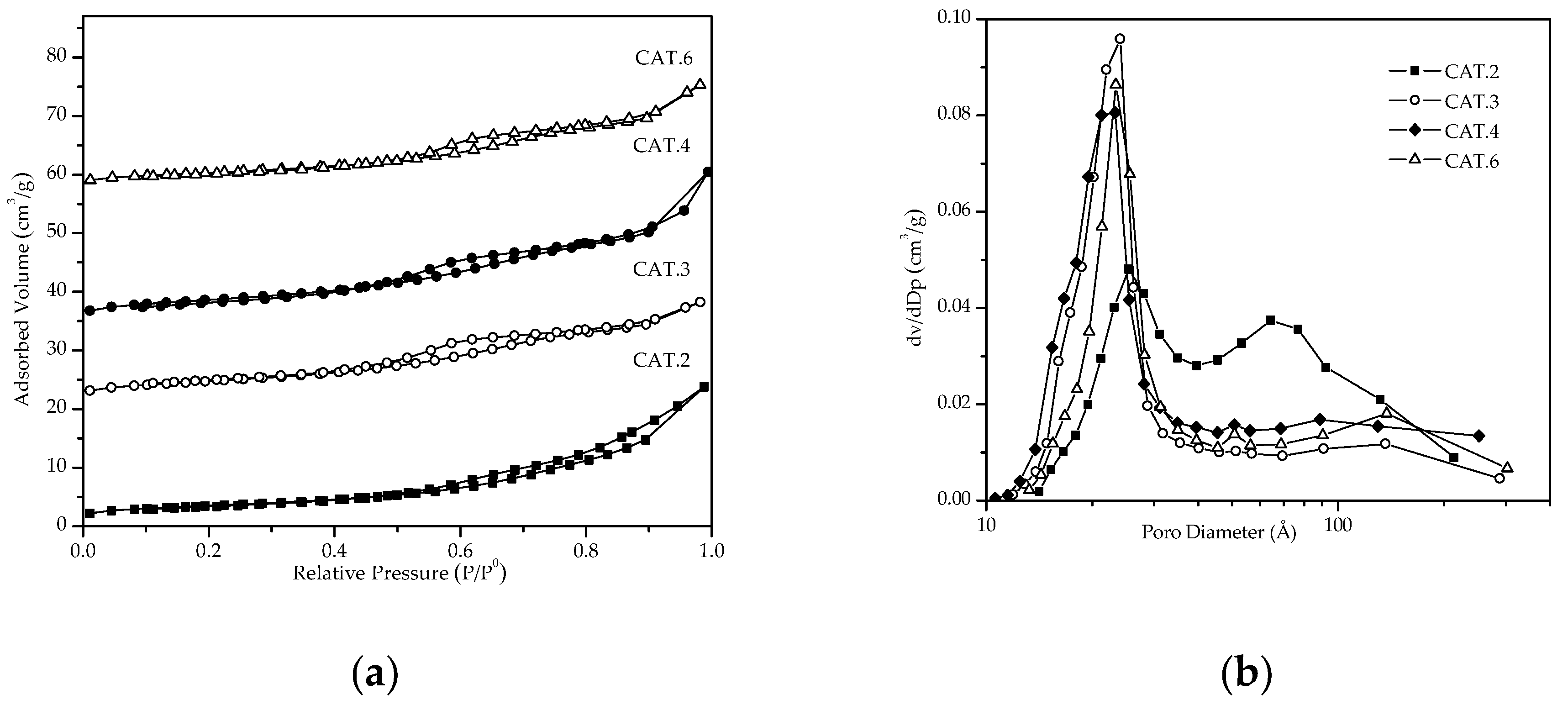

3.1.1. Textural Properties

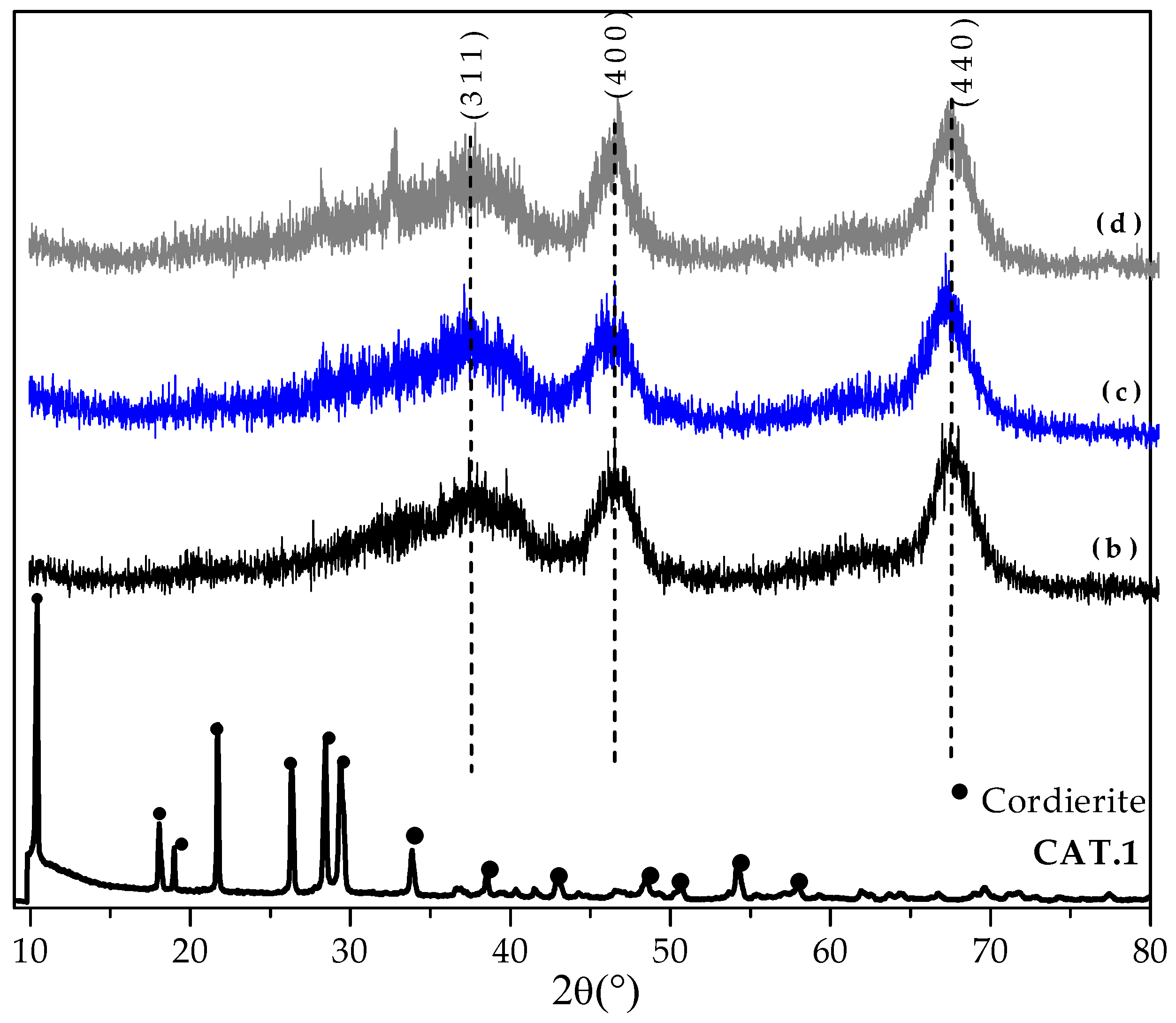

3.1.2. Crystalline Properties

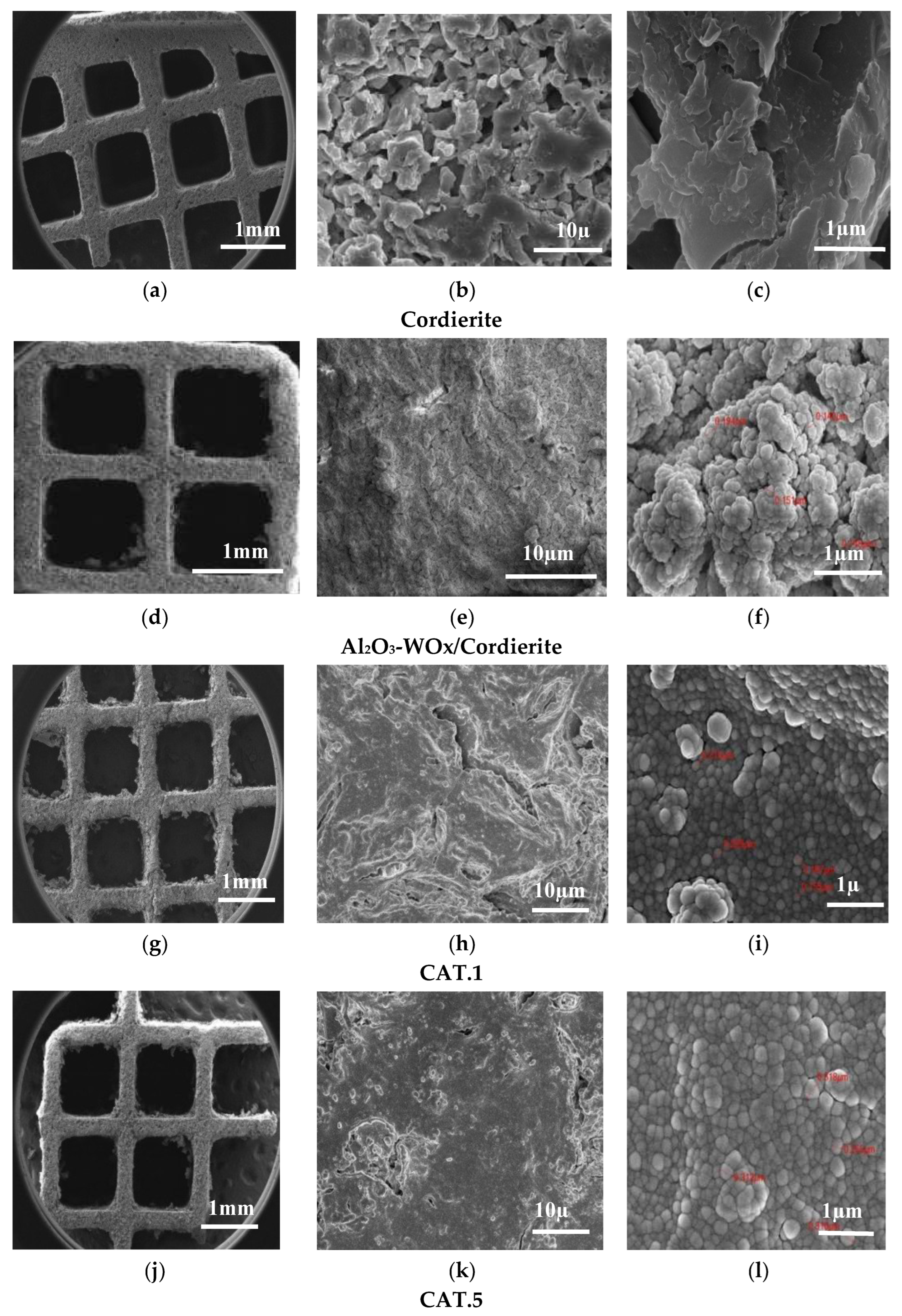

3.1.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM/EDX) Before Catalytic Evaluation

3.1.4. Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (HAADF-STEM)

3.1.5. Temperature Programmed Reduction (H2-TPR)

3.1.6. Pt Dispersion (H2-Chemisorption)

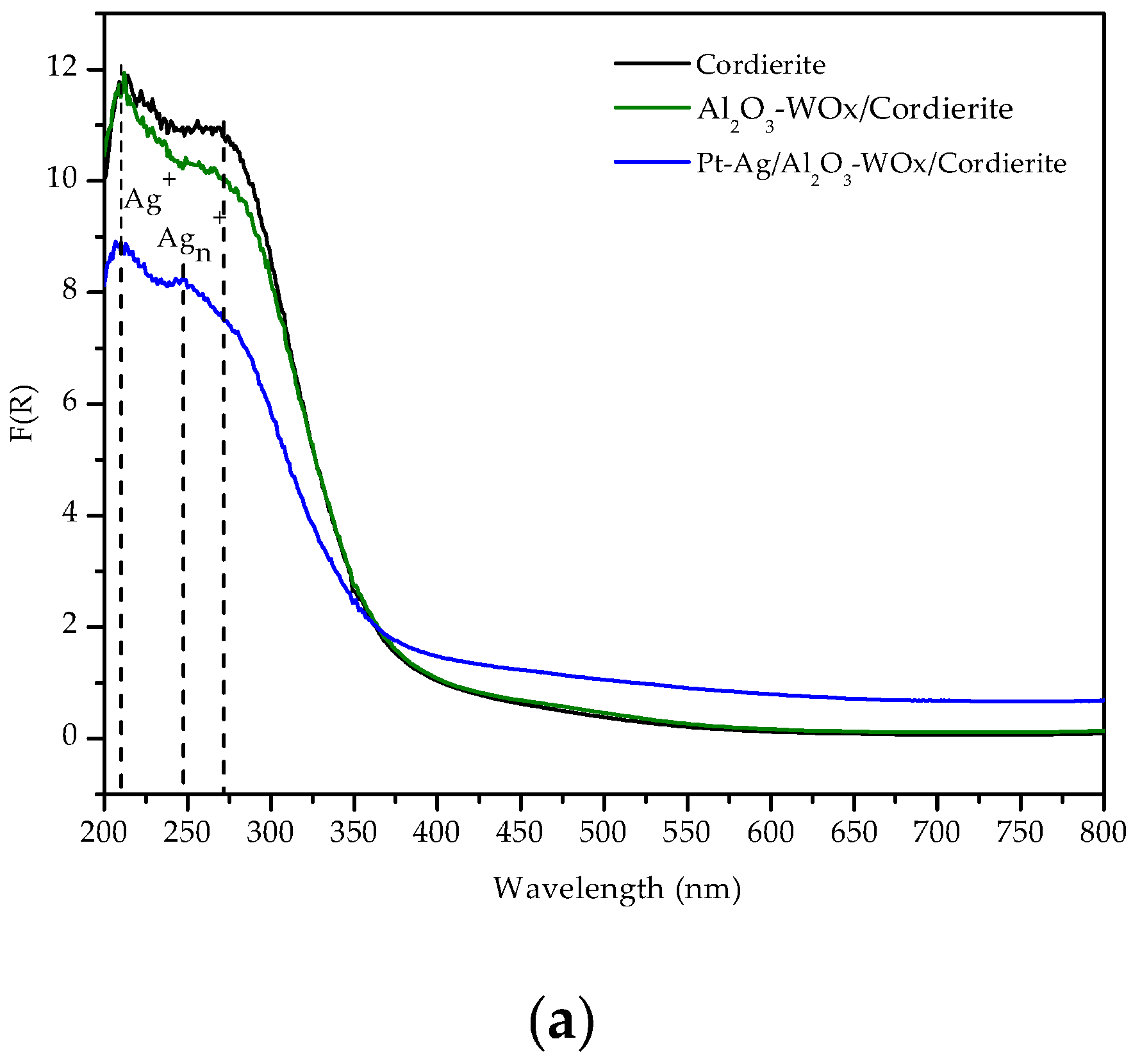

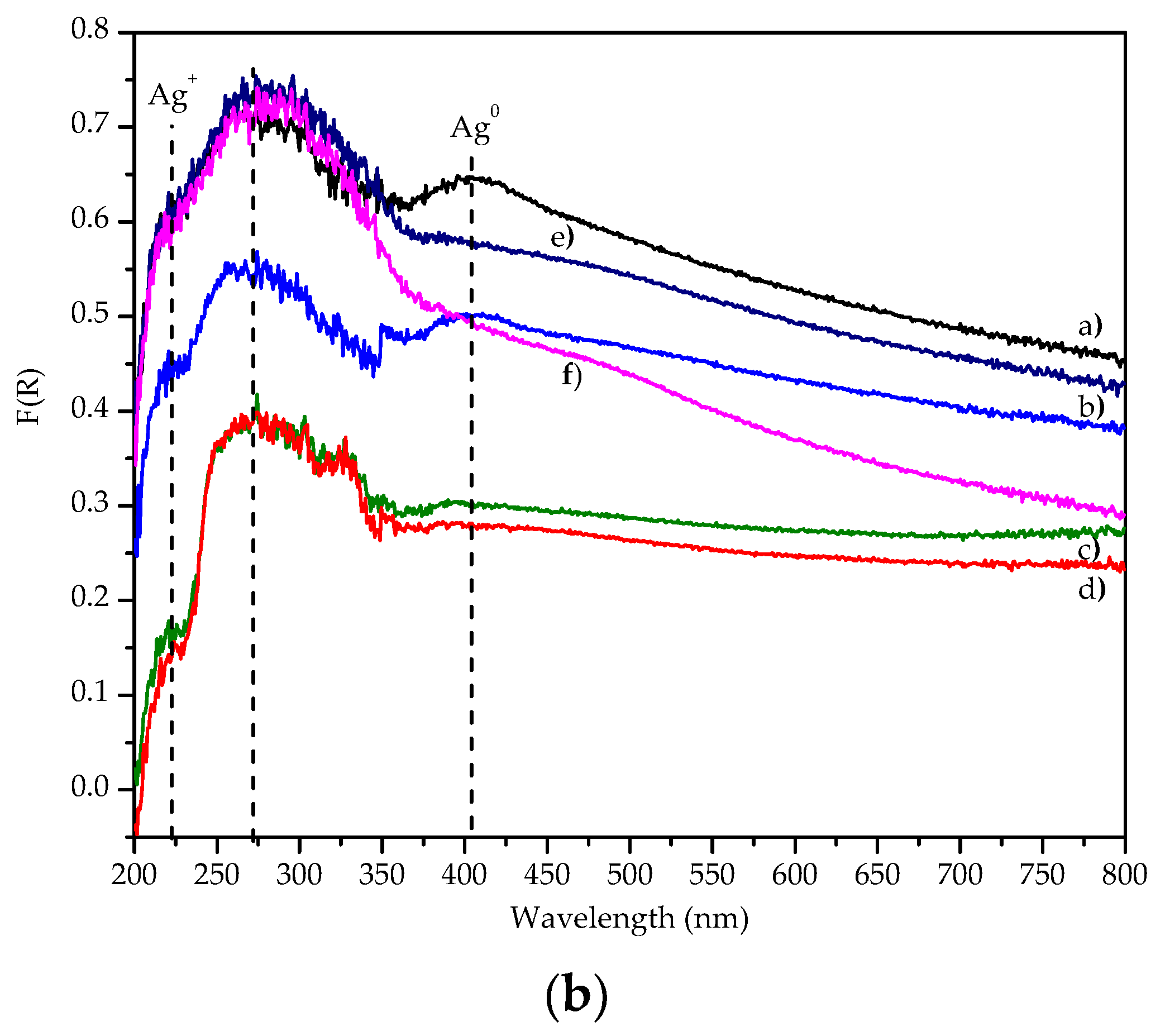

3.1.7. Ex-situ UV-vis Spectra of the Pt-Ag/Al2O3-WOx/Cordierite Catalysts

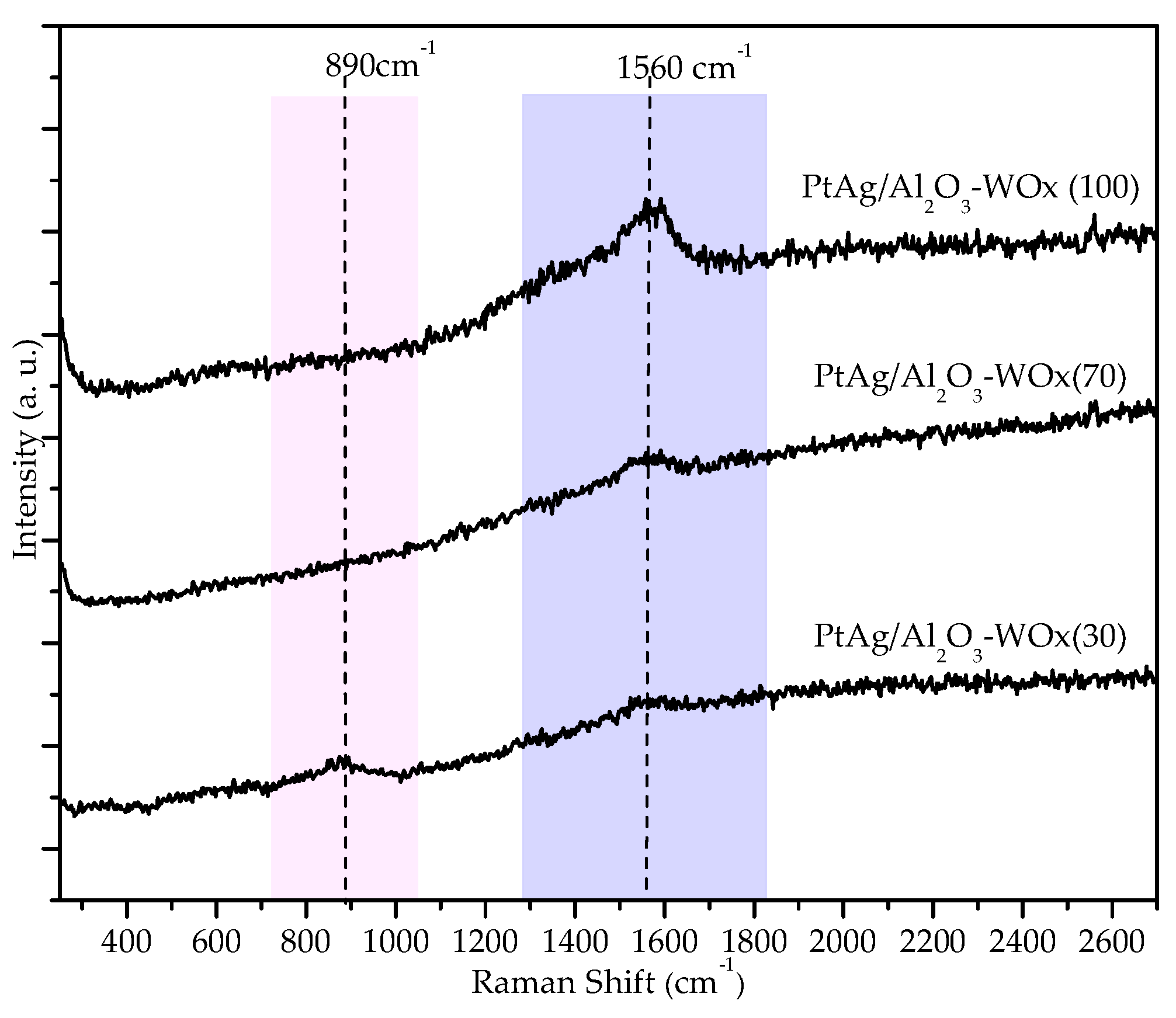

3.1.8. Raman Spectra the Pt-Ag/Al2O3-WOx/Cordierite (CAT.1) Catalyst Evaluated

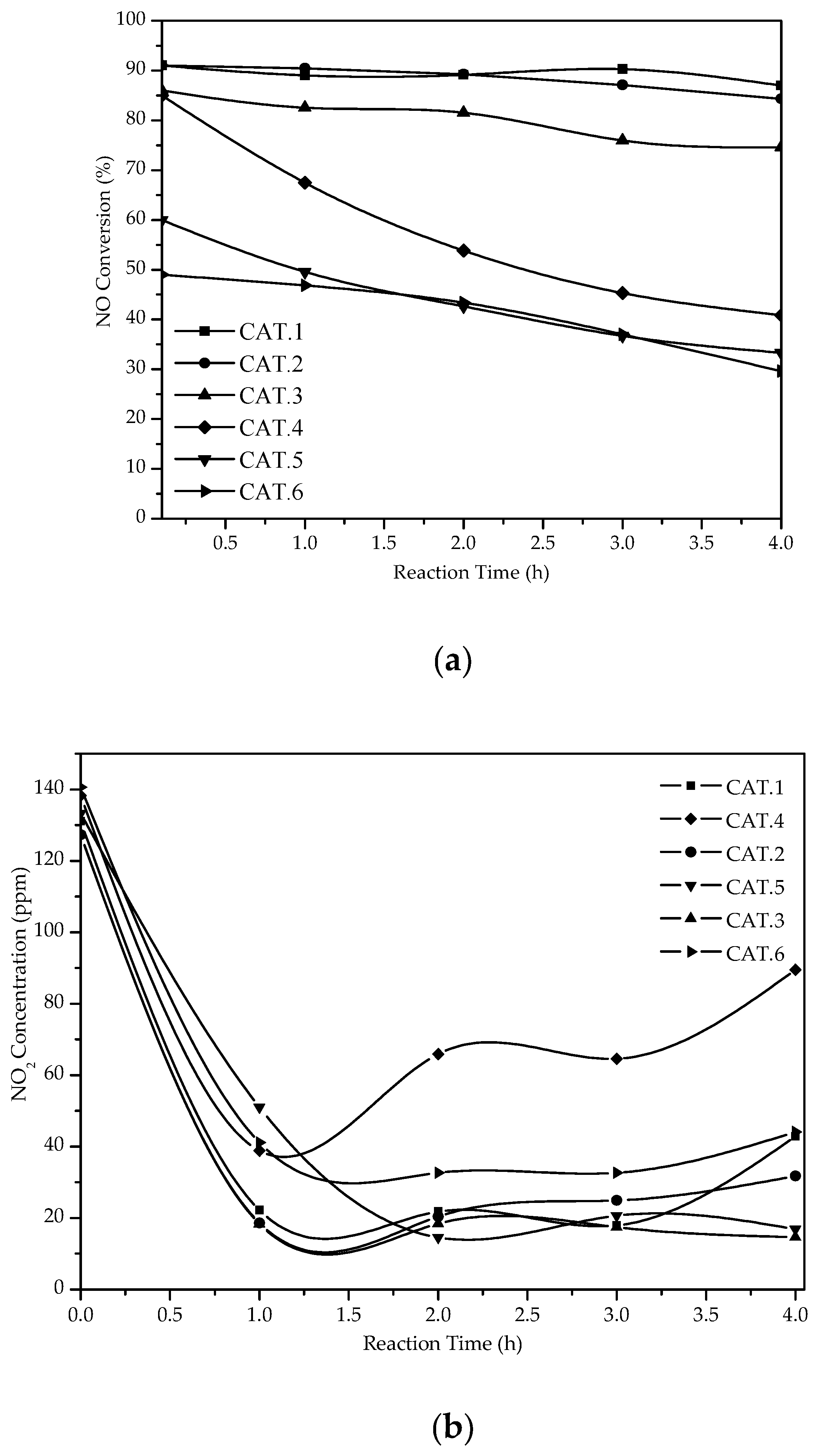

3.2. Catalytic Tests

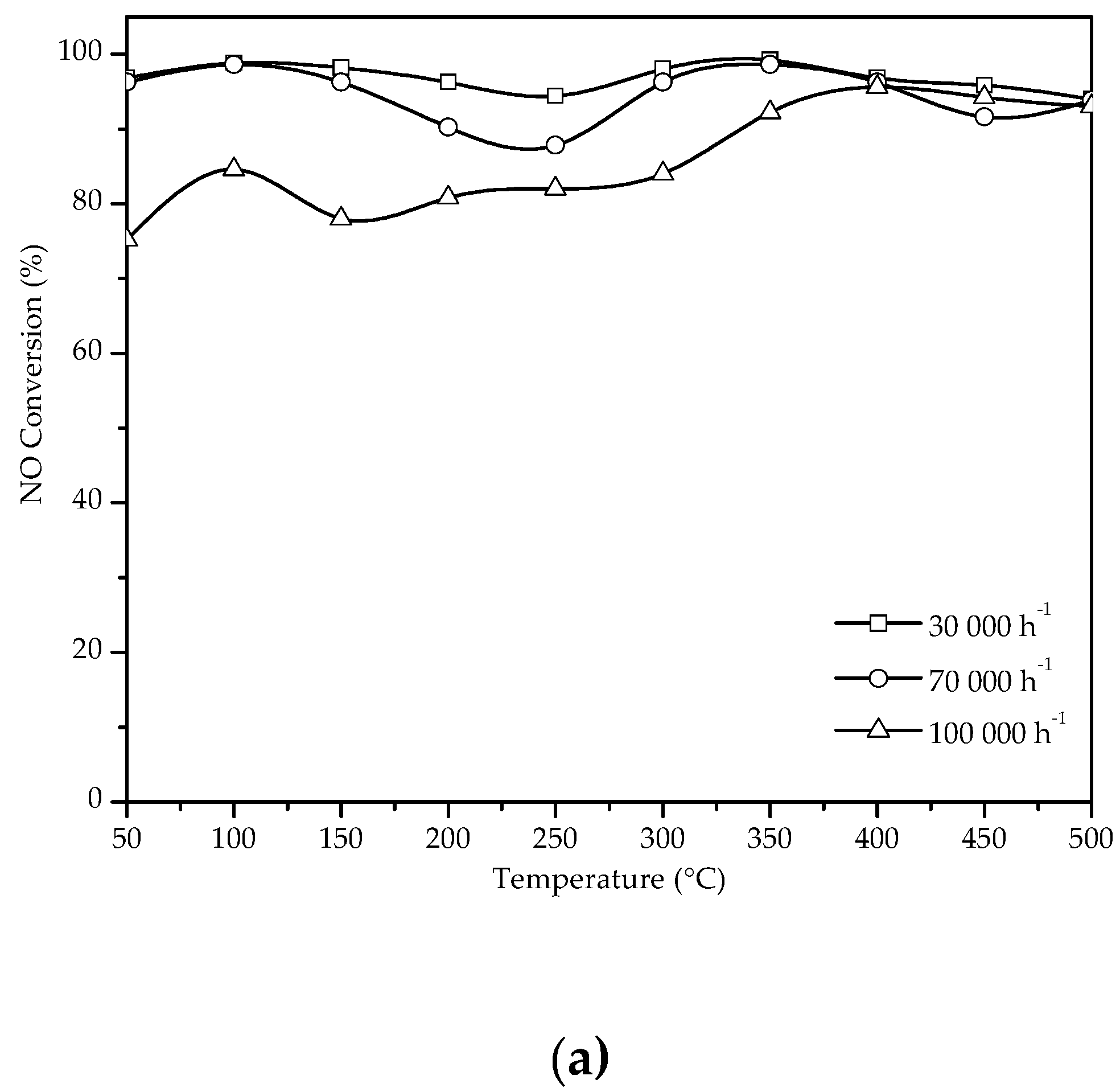

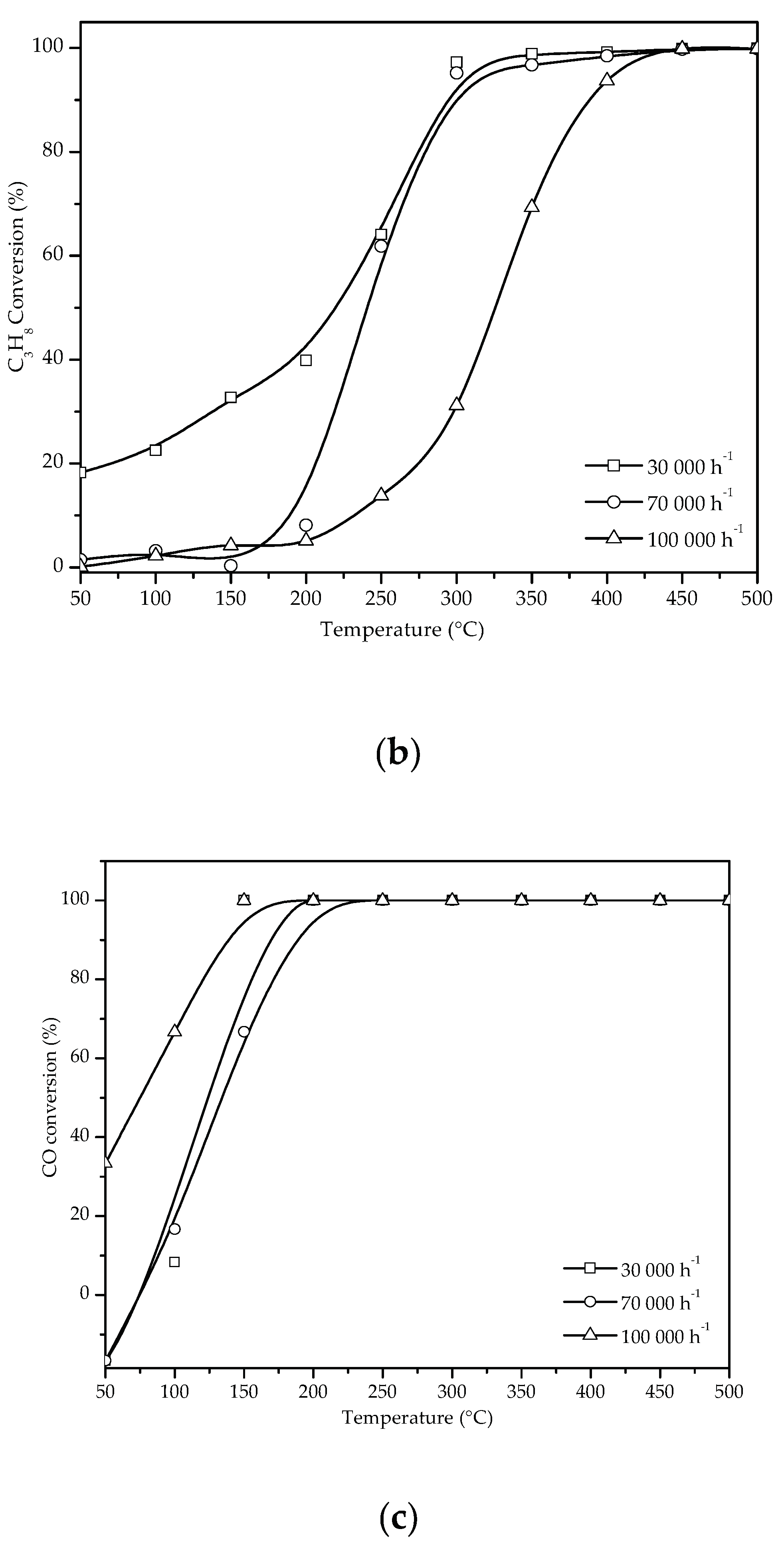

3.2.1. NO Conversion in the SCR with C3H8 Without H2

3.2.2. NO Conversion the CAT.1 Catalyst in the SCR with C3H8 Assisted by H2

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HC-SCR | Selective Catalytic seduction with Hydrocarbons |

| H2-HC-SCR | Selective Catalytic Reduction with Hydrocarbons and Hydrogen |

| GHSV | Gas Hourly Space Velocity |

| SEM/EDX | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| STEM/HAADF | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| TPR-H2 | temperature programmed reduction |

| CRTA | Cordierite |

| SBET | BET area |

| Vp | Pore Volume |

| Dp | Pore Diameter |

References

- Bueno-López, A.; Illán-Gómez, M.; de Lecea, C.S.-M. Effect of NOx and C3H6 partial pressures on the activity of Pt-beta-coated cordierite monoliths for deNOx C3H6-SCR. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 2006, 302, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannisto, H.; Ingelsten, H.H.; Skoglundh, M. Ag–Al2O3 catalysts for lean NOx reduction—Influence of preparation method and reductant. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2009, 302, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satokawa, S.; Yamaseki, K.-I.; Uchida, H. Influence of low concentration of SO2 for selective reduction of NO by C3H8 in lean-exhaust conditions on the activity of Ag/Al2O3 catalyst. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2001, 34, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionta, G.D.; Christoforou, S.C.; Efthimiadis, E.A.; Vasalos, I.A. Selective Catalytic Reduction of NO with Hydrocarbons: Experimental and Simulation Results. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1996, 35, 2508–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C. , Paulus M. , Chu W., Find J., Nickl A. J., Kohler K. Selective Catalytic reduction of NO by C3H8 over CoOx/Al2O3: An investigation of structure-activity relationships. Catalysis Today, 2008, 131, 305–313. [Google Scholar]

- Popovych, N.O.; Soloviev, S.O.; Orlyk, S.M. Selective Reduction of Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) with Oxygenates and Hydrocarbons over Bifunctional Silver–Alumina Catalysts: a Review. Theor. Exp. Chem. 2016, 52, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriienko, P.; Popovych, N.; Soloviev, S.; Orlyk, S.; Dzwigaj, S. Remarkable activity of Ag/Al2O3/cordierite catalysts in SCR of NO with ethanol and butanol. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2013, 140-141, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethke, K.A.; Kung H., H. Supported Ag catalysts for the lean reduction of NO with C3H6. J. Catal. 1997, 172, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. C.; Kung, H.H. Kung. Lean NOx catalysis over alumina-supported catalysts. Top. Catal. 2000, 10, 21–26.

- Meunier F., C.; Breen J., P.; Zuzaniuk, V.; Olsson, M.; Ross J. R., H. Mechanistic aspects of the selective reduction of NO by propene over alumina and silver-alumina catalysts. J. Catal. 1999, 187, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Arias, A.; Fernández-García, M.; Iglesias-Juez, A.; Anderson, J.A.; Conesa, J.C.; Soria, J. Study of the lean NOx reduction with C3H6 in the presence of water over silver/alumina catalysts prepared from inverse microemulsions. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2000, 28, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Carucci J., R. , Kurman a. , Karhu H., Arve K., Eranen k., Warna j., Salmi T., Murzin D. Yu. Kinetics of the biofuels-assisted SCR of NOx over Ag/Alumina-coated microchannels. Chemical Engineering Journal 2009, 154, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Held, W. , Koning, A. Paper Ser. No. 90 0496, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto, M. , Yahiro H. , Shundo S., Yu-u Y., Mizuno N. Appl. Catal. 1991, 69, L15. [Google Scholar]

- Eränen, K.; Klingstedt, F.; Arve, K.; Lindfors, L.-E.; Murzin, D.Y. On the mechanism of the selective catalytic reduction of NO with higher hydrocarbons over a silver/alumina catalyst. J. Catal. 2004, 227, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Männikkö, M.; Wang, X.; Skoglundh, M.; Härelind, H. Characterization of the active species in the silver/alumina system for lean NO reduction with methanol. Catal. Today 2016, 267, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Yu, Y.; He, H. Adsorption states of typical intermediates on Ag/Al2O3 catalyst employed in the selective catalytic reduction of NOx by ethanol. Chinese Journal of Catalysis 2015, 36, 1312–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoost T., E.; Kudla R., J.; Collins K., M.; Chattha M., S. Characterization of Ag/γ-Al2O3 catalysts and their lean-NOx properties. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 1997, 13, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaieb, T.; Delannoy, L.; Costentin, G.; Louis, C.; Casale, S.; Chantry, R.L.; Li, Z.; Thomas, C. Insights into the influence of the Ag loading on Al2O3 in the H2-assisted C3H6-SCR of NO. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2014, 156-157, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Terán, M.E.; Fuentes, G.A. Enhancement by H2 of C3H8-SCR of NOx using Ag/γ-Al2O3. Fuel 2014, 138, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ström, L.; Carlsson, P.-A.; Skoglundh, M.; Härelind, H. Surface Species and Metal Oxidation State during H2-Assisted NH3-SCR of NOx over Alumina-Supported Silver and Indium. Catalysts 2018, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Ma, J.; Wang, L.; Lv, Z.; Wang, S.; Yu, Y.; He, H. Mechanism of the H2 Effect on NH3-Selective Catalytic Reduction over Ag/Al2O3: Kinetic and Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy Studies. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 10489–10498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Cao, J.; Wang, L.; Guo, Y.; Lu, G.; Guo, Y. The study of C 3 H 8 -SCR on Ag/Al 2 O 3 catalysts with the presence of CO. Catal. Today 2017, 281, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, F.; Kannisto, H.; Skoglundh, M.; Härelind, H. Improved low-temperature activity of silver–alumina for lean NOx reduction – Effects of Ag loading and low-level Pt doping. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 152–153, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wang, J.; Feng, Q.; Yu, Y.; Yoshida, K. Novel Pd promoted Ag/Al2O3 catalyst for the selective reduction of NOx. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2003, 46, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, F.J.P.; Balle, P.; Adler, J.; Kureti, S. Reduction of NOx by H2 on Pt/WO3/ZrO2 catalysts in oxygen-rich exhaust. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 87, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, J.L.; Fuentes, G.A.; García, L.A.; Salmones, J.; Zeifert, B. WOx effect on the catalytic properties of Pt particles on Al2O3. Journal of Alloy and Compounds 2009, 483, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, J.L.; Fuentes, G.A.; Zeifert, B.; Salmones, J. Stabilization of supported platinum nanoparticles on γ-alumina catalysts by addition of tungsten. J. Alloy. Compd. 2009, 483, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Hernández, N.N.; Contreras, J.L.; Pinto, M.; Zeifert, B.; Flores Moreno, J.L.; Fuentes, G.A.; Hernández-Terán, M.E.; Vázquez, T.; Salmones, J.; Jurado, J.M. Improved NOx Reduction Using C3H8 and H2 with Ag/Al2O3 Catalysts Promoted with Pt and WOx. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, M.; Groppi, G.; Cristiani, C.; Levi, M.; Tronconi, E.; Forzatti, P. The deposition of γ-Al2O3 layers on ceramic and metallic supports for the preparation of structured catalysts. Catal. Today 2001, 69, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürgen, L., K. , Dieter, L., H., Egbert, L., H., Thomas, K., K., Wilfred, M., O. y Rainer, D., A. Diesel Catalytic. Converter. Patent No. 5, 928, 981.

- Shelef, M.; Montreuil, C.N.; Jen, H.W. NO2 formation over Cu-ZSM-5 and the selective catalytic reduction of NO. Catal. Lett. 1994, 26, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimark, A.V.; Sing, K. W.; Thommes, M. Handbook of Heterogeneous Catalysis, 2nd Ed., G. Ertl., H. Knozinger, F. Schuth, J. Weitkamp. Eds., VCH-Wiley, 2008, 4.

- Contreras, J. L.; Fuentes, G. A. Study of the Pt/Al2O3-WOx Catalyst in the conversion of Heptane. Spanish Academic Editorial Ed., 2013.

- Sing, K.S.W.; Everett D., H.; Haul R. A., W.; Moscou, L.; Pierotti R., A.; Rouquerol, J.; Siemieniewska, T. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity. Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascaso, M. S. Catalysts free of noble metals for the simultaneous elimination of soot and NOx in Diesel engines. Doctoral Thesis, University of Zaragoza, Spain, 2015. http://hdl.handle.net/10261/118009.

- Rojas, H.; Borda, G.; Reyes, P.; Brijaldo, M.; Valencia, J. Liquid-phase hydrogenation of m-dinitrobenzene over platinum catalysts. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2011, 56, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterfield, C.N. , Heterogeneous Catalysis in Practice. McGraw Hill Inc. 1980, p.114. ISBN:0070548757.

- Mather, R.; McEnaney, B.; Mays, T. J.; Rouquerol, J.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F.; Sing, K. S. W.; Unger, K. K. Characterization of Porous Solids IV. Royal Society of Chemistry. 1997, 213, 314–318. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.A.; Thomas, K. Applications of Raman microprobe spectroscopy to the characterization of carbon deposits on catalysts. Fuel 1984, 63, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Hu, C.; Tang, Z. Preparation and performance study of cordierite/mullite composite ceramics for solar thermal energy storage. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2017, 14, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado, J.; Escola, J.; Castro, M. Influence of the thermal treatment upon the textural properties of sol–gel mesoporous γ-alumina synthesized with cationic surfactants. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010, 128, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Terán, M.E.; Fuentes, G.A. Enhancement by H2 of C3H8-SCR of NOx using Ag/γ-Al2O3. Fuel 2014, 138, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Bentrup, U.; Eckelt, R.; Schneider, M.; Fricke, R. The effect of hydrogen on the selective catalytic reduction of NO in excess oxygen over Ag/Al2O3. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2004, 51, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, S.; Friedrich, H.B. Monoliths: A Review of the Basics, Preparation Methods and Their Relevance to Oxidation. Catalysts 2017, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-López, A.; Lozano-Castelló, D.; Such-Basáñez, I.; García-Cortés, J.; Illán-Gómez, M.; de Lecea, C.S.-M. Preparation of beta-coated cordierite honeycomb monoliths by in situ synthesis. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2005, 58, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratenko, V.; Bentrup, U.; Richter, M.; Hansen, T.; Kondratenko, E. Mechanistic aspects of N2O and N2 formation in NO reduction by NH3 over Ag/Al2O3: The effect of O2 and H2. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2008, 84, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthard, F. Palladium and platinum-based catalysts in the catalytic reduction of nitrate in water: effect of copper, silver, or gold addition. J. Catal. 2003, 220, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Huang, W.; Cheng, M.; Bao, X. Restructuring and Redispersion of Silver on SiO2 under Oxidizing/Reducing Atmospheres and Its Activity toward CO Oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 15842–15848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieske, H. Reactions of platinum in oxygen- and hydrogen-treated Pt/$gamma;-Al2O3 catalysts I. Temperature-programmed reduction, adsorption, and redispersion of platinum. J. Catal. 1983, 81, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Lee, H.H.; Hong, S.C. A study on the effect of support's reducibility on the reverse water-gas shift reaction over Pt catalysts. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 2012, 423-424, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Terán, M.E. Development of Ag/γ-Al2O3 and Ag/α-Al2O3 Catalytic Systems for H2-Assisted NO C3H8-SCR under Oxidizing Operation for Emission Control Systems for Diesel Engines or Stationary Sources. Ph.D.; Thesis, Universidad Au-tónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2020.

- Kannisto, H.; Arve, K.; Pingel, T.; Hellman, A.; Härelind, H.; Eränen, K.; Olsson, E.; Skoglundh, M.; Murzin, D.Y. On the performance of Ag/Al2O3as a HC-SCR catalyst – influence of silver loading, morphology and nature of the reductant. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallares-García, A.; Contreras, J.L.; Pérez-Cabrera, J.; Zeifert, B.; Vázquez, T.; Salmones, J.; Gutiérrez-Limón, M.A. Stabilization of Pt in SiO2–Al2O3 Microspheres at High Mechanical Resistance, Promoted with W Oxides for the Combustion of CO. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietz, G. Reactions of platinum in oxygen- and hydrogen-treated Pt/$gamma;-Al2O3 catalysts II. Ultraviolet-visible studies, sintering of platinum, and soluble platinum. J. Catal. 1983, 81, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arve, K.; Čapek, L.; Klingstedt, F.; Eränen, K.; Lindfors, L.-E.; Murzin, D.Y.; Dědeček, J.; Sobalik, Z.; Wichterlová, B. Preparation and characterisation of Ag/alumina catalysts for the removal of NO x emissions under oxygen rich conditions. Top. Catal. 2004, 30-31, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linjie Hu, Kenneth, A. ; Boateng, Josephine, M.; Hill, Sol–gel synthesis of Pt/Al2O3 catalysts: Effect of Pt precursor, Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical. 2006, 259, 51–60.

- Wichterlová, B.; Sazama, P.; Breen, J.; Burch, R.; Hill, C.; Čapek, L.; Sobalík, Z. An in situ UV–vis and FTIR spectroscopy study of the effect of H2 and CO during the selective catalytic reduction of nitrogen oxides over a silver alumina catalyst. J. Catal. 2005, 235, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Ma, J.; He, G.; Yu, Y.; He, H. An alumina-supported silver catalyst with high water tolerance for H2 assisted C3H6-SCR of NOx. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2017, 207, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, J.; Salmones, J.; Colín-Luna, J.; Nuño, L.; Quintana, B.; Córdova, I.; Zeifert, B.; Tapia, C.; Fuentes, G. Catalysts for H 2 production using the ethanol steam reforming (a review). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 18835–18853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Juez, A.; Hungrı́a, A.; Martı́nez-Arias, A.; Fuerte, A.; Fernández-Garcı́a, M.; Anderson, J.; Conesa, J.; Soria, J. Nature and catalytic role of active silver species in the lean NOx reduction with C3H6 in the presence of water. J. Catal. 2003, 217, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamm, S.; Andonova, S.; Olsson, L. The Effect of Hydrogen on the Storage of NOx Over Silver, Platinum and Barium Containing NSR Catalysts. Catal. Lett. 2014, 144, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligaard, T.; Nørskov, J.; Dahl, S.; Matthiesen, J.; Christensen, C.; Sehested, J. The Brønsted–Evans–Polanyi relation and the volcano curve in heterogeneous catalysis. J. Catal. 2004, 224, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.-I.; Shibata, J.; Yoshida, H.; Satsuma, A.; Hattori, T. Silver-alumina catalysts for selective reduction of NO by higher hydrocarbons: structure of active sites and reaction mechanism. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2007, 30, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.; Figueiredo, J.L. Synergistic effect between Pt and K in the catalytic reduction of NO and N2O. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2006, 62, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Yadav, D.; Thakur, P.; Pandey, J.; Prasad, R. Studies on H2-Assisted Liquefied Petroleum Gas Reduction of NO over Ag/Al2O3 Catalyst. Bull. Chem. React. Eng. Catal. 2018, 13, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, R.; Kolaczkowski, S. Mass and heat transfer effects in catalytic monolith reactors. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1994, 49, 3587–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.; Hayes, R.E.; Kolaczkowski, S.T. Diffusion limitation effects in the washcoat of a catalytic monolith reactor. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1996, 74, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomašić, V.; Gomzi, Z. Experimental and theoretical study of NO decomposition in a catalytic monolith reactor. Chem. Eng. Process. - Process. Intensif. 2004, 43, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, R.E.; Kolaczkowski, S.T.; Li, P.K.; Awdry, S. The palladium catalysed oxidation of methane: reaction kinetics and the effect of diffusion barriers. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2001, 56, 4815–4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, H.; Wang, N.; Ring, Z.; Dabros, T. Mathematical modeling of monolith catalysts and reactors for gas phase reactions. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 2008, 345, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaczkowski, S.T. Modelling catalytic combustion in monolith reactors – challenges faced. Catal. Today 1999, 47, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Harold, M.P.; Balakotaiah, V. Mass-transfer coefficients in washcoated monoliths. AIChE J. 2004, 50, 2939–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.J. , Kolaczkowski, S. t. and Thomas, W.J. Determination of heterogeneous reaction kinetics and reaction rates under mass transfer controlled conditions for a monolith reactor. Trans. Instn. Chem. Engr. 1991, 69, part B, 209–220. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, R.; Kolaczkowski, S. Mass and heat transfer effects in catalytic monolith reactors. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1994, 49, 3587–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, A.; Andersson, B. Mass transfer in monolith catalysts–CO oxidation experiments and simulations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1998, 53, 2285–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomašić, V.; Gomzi, Z.; Zrnčević, S. Reaction and mass transfer effects in a catalytic monolith reactor. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 2002, 77, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppi, G.; Belloli, A.; Tronconi, E.; Forzatti, P. A comparison of lumped and distributed models of monolith catalytic combustors. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1995, 50, 2705–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Balakotaiah, V. Heat and mass transfer coefficients in catalytic monoliths. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2001, 56, 4771–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogler, S. H. Elements of Chemical Reaction Engineering, 3rd. Ed.; Prentice Hall Inc. New Jersey, USA, 1999; pp.738-758.

| Catalyst Name | Key | Calcined | Evaluated | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBET(a) (m2/g) |

Vp(b) (cm3/g) |

Dp(c) (Å) |

SBET (m2/g) |

Vp (cm3/g) |

Dp (Å) |

||

| Al2O3-WOx/Cordierite | AW/CRTA | 55.89 | 0.09 | 28.59 | --- | --- | --- |

| 0.1Pt-2Ag/Al2O3-WOx /Cordierite | CAT.1 | 20.90 | 0.03 | 66.62 | 10.41 | 0.02 | 38.94 |

| 0.1Pt-2Ag/Al2O3-WOx /Cordierite | CAT.2 | 20.64 | 0.03 | 55.26 | 10.39 | 0.02 | 48.13 |

| 0.1Pt-2Ag/Al2O3-WOx /Cordierite | CAT.3 | 21.00 | 0.03 | 59.00 | 15.20 | 0.02 | 33.45 |

| 0.1Pt-2Ag/Al2O3-WOx /Cordierite | CAT.4 | 18.39 | 0.06 | 42.91 | 12.74 | 0.04 | 39.02 |

| 2Ag/Al2O3-WOx / Cordierite | CAT.5 | 47.55 | 0.07 | 63.58 | 26.33 | 0.04 | 32.43 |

| 0.1Pt-2Ag/Al2O3-WOx /Cordierite | CAT.6 | 25.54 | 0.04 | 39.00 | 12.91 | 0.03 | 36.65 |

| Catalysts | %DPt(a) | %DPt(b) |

| CAT.1 | 76.8 | 73.47 |

| CAT.2 | 70.8 | 34 |

| CAT.3 | 35.4 | 30.65 |

| CAT.4 | 25.3 | 23.41 |

| CAT.6(c) | 7.07 | 4.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).