1. Introduction

It is clear that the observation of gravitational waves by the Ligo-Handford and Ligo-Louisana detectors confirms the predictions of Einstein’s theory of general relativity and its general solutions, to the detriment of modified gravitation theories [

1,

2,

3]. However, the presence of gravitons in the observation of gravitational waves has led to a major revival of interest in better understanding the compatibility between the theory of general relativity and that of quantum mechanics [

4]. This is all the more obvious when we look at the evaporation of black holes as predicted by Hawking [

5]. According to the theory of relativity, black holes are supposed to absorb everything that comes near them and emit nothing in return, contrary to quantum mechanics. This idea is even more interesting: when we study a black hole from the point of view of the quantum mechanics of black holes, we obtain a picture opposite to that of the theory of general relativity, with the presence of certain phenomena violating the principles of general relativity [

5,

6]. These divergences set up a fundamental problem as to the real nature of the theory of relativity in its current form. These different results open the way for further reflection on whether or not Einstein’s gravitation in its original form should be modified [

2,

4,

7]. Taking into account Wheeler’s [

8] remarks, namely on one of the concepts of general relativity theory, the notion of body treatment. In the process, he indicated two possibilities for the concrete study of this notion. The first is to consider the body as a singularity in the metric, while retaining the original form of general relativity theory. The second approach is to assume the regularity of the gravitational field throughout the entire region of space, and to use quantum mechanics to clarify this effect on the region of the body. Starting from Wheeler’s [

8] assumption that spacetime must be treated as a quantum field in gravitation theory, a number of works based on Wheeler’s [

8] principle have demonstrated their effectiveness in the quantization of gravity and the existence of gravitons [

4,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In the same vein, the unification of general relativity theory and quantum mechanics by the equation

[

13] has proved to be a solid possibility, insofar as we are only able to explain the phenomenon of Hawking radiation [

5,

6] from certain solutions derived from Einstein’s gravitation. This success, and the advent of technology, has raised many questions about the urgency of devising a theory of quantum gravity [

1,

4,

14]. By treating spacetime as quantum space, it has now been proven that the deformation of spacetime leading to gravitational waves also results in the presence of gravitons [

4,

12], which marks the proof of the quantization of the gravitational field. Given these principles, it will be important to find an appropriate mathematical formalism capable of reconciling these two theories in the context of the study of black holes. In recent work [

15,

16,

17], it has been shown that Schwarzschild black holes behave similarly to gravitational solitons when the gravitational field is regular throughout the region of spacetime. Building on the notion of gravitational solitons [

17], it is shown that it is possible to construct gravitational waves with properties almost similar to those observed by the Ligo-Handford and Ligo-Louisana [

1] using a system of two cylindrical soliton solutions. In this procedure, we use Pomeransky’s inverse scattering method (ISM) [

18] to treat Einstein and Rosen’s spacetime [

19] in a quantum manner in order to obtain two intricate black holes that in fact constitute an

pair [

20]. In a first approach, it will be important to investigate the nature of the noise present in the Ligo-Handford and Ligo-Louisana detectors [

1]. In a second approach, we show the direct link between the behavior of two intricate black holes in the form of an

pair and Hawking radiation [

5].

2. Gravitational Waves

The presence of gravitons during the propagation of gravitational waves as highlighted by Dyson [

21], leads us to question the nature of the noise coming from the Ligo-Handford and Ligo-Louisana detectors [

1]. This notion of “noise” becomes crucial in understanding the quantization of the gravitational field [

9,

10,

12]. In this section, we will demonstrate the presence of the graviton in the Ligo-Handford detector, based on the work done in ref. [

17]. In this procedure, let us introduce the following metric [

17]:

We note that represents the cylindrical coordinates and t the time. We specify that the different functions and depend on and t. In this metric including the Einstein field equations, represents a dynamic degree of freedom of the gravitational field and plays the role of the gravitational energy of the system. It is also noted that the previous quantities written with comma as subscript denotes the partial derivatives with the associated variables.

Using the different quantities

are

whose physical meanings are clearly established [

17], we show that when

with similar conditions we obtain a new form of gravitational wave propagation according to the following configuration:

This result shows that the gravitational wave, as it propagates in the zone under consideration, is capable of splitting. Clearly, the splitting of the wave during propagation is due to the presence of the spin

, which acts as a graviton [

22]. At this stage, it’s difficult to observe the presence of graviton in concrete terms, as Dyson [

21] points out. It is important to specify that every propagating wave possesses an inverse with identical properties whatever the distance considered, confirming the hypothesis of

[

20]. Moreover, we emphasize that the different configurations mentioned have the same energy densities previously studied [

17]. We mentioned that by treating spacetime in a quantum manner, it is possible to quantify the gravitational field [

9,

10]. It would be interesting to show indirectly the presence of gravitons during the propagation of the gravitational wave. To this end, we rely on the quantum entanglement [

23] commented in

Figure 1 to build the LIGO-Handford detector. In this procedure, we use the physical quantity

with the same clearly established conditions [

17] and obtain the following configuration:

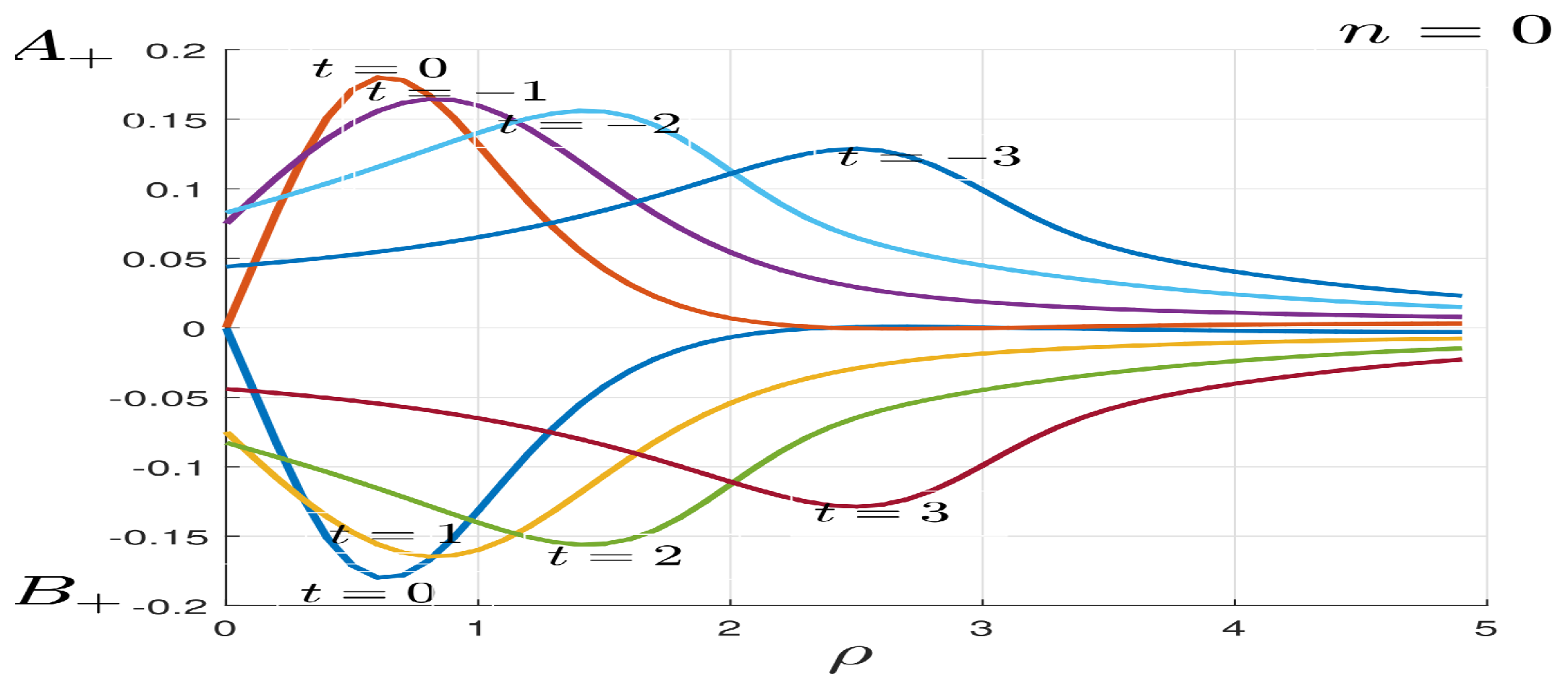

Figure 1.

It can be seen that at , the amplitude is maximum for the different waves obtained. The new gravitational wave (ER) is concentrated near the radius on the explosion trajectory, for negative values of t and remains above . While the new gravitational wave (ER) is concentrated near the radius on the implosion trajectory, for positive values of t and remains below . For and .

Figure 1.

It can be seen that at , the amplitude is maximum for the different waves obtained. The new gravitational wave (ER) is concentrated near the radius on the explosion trajectory, for negative values of t and remains above . While the new gravitational wave (ER) is concentrated near the radius on the implosion trajectory, for positive values of t and remains below . For and .

Figure 2.

The direct observation of this signal in the ER-[

19] spacetime is done by using the explosion wave

and by introducing a noise at the order

. We use the following parameters: for

with

).

Figure 2.

The direct observation of this signal in the ER-[

19] spacetime is done by using the explosion wave

and by introducing a noise at the order

. We use the following parameters: for

with

).

It is important to note that the blue curve represents the noisy signal coming from the detector, and it may be the presence of graviton during the propagation of the gravitational wave [

1,

9,

10,

23]. The red curve, on the other hand, reflects the reconstructed gravitational wave signal. We can see that the two signals coming from the two detectors are in fact intricate and have similar characteristics, whatever the distance considered. We note, that the results obtained in this section confirm the Shapiro et al. [

24] hypothesis that gravitational waves is a strong argument for the evidence of quantum gravity.

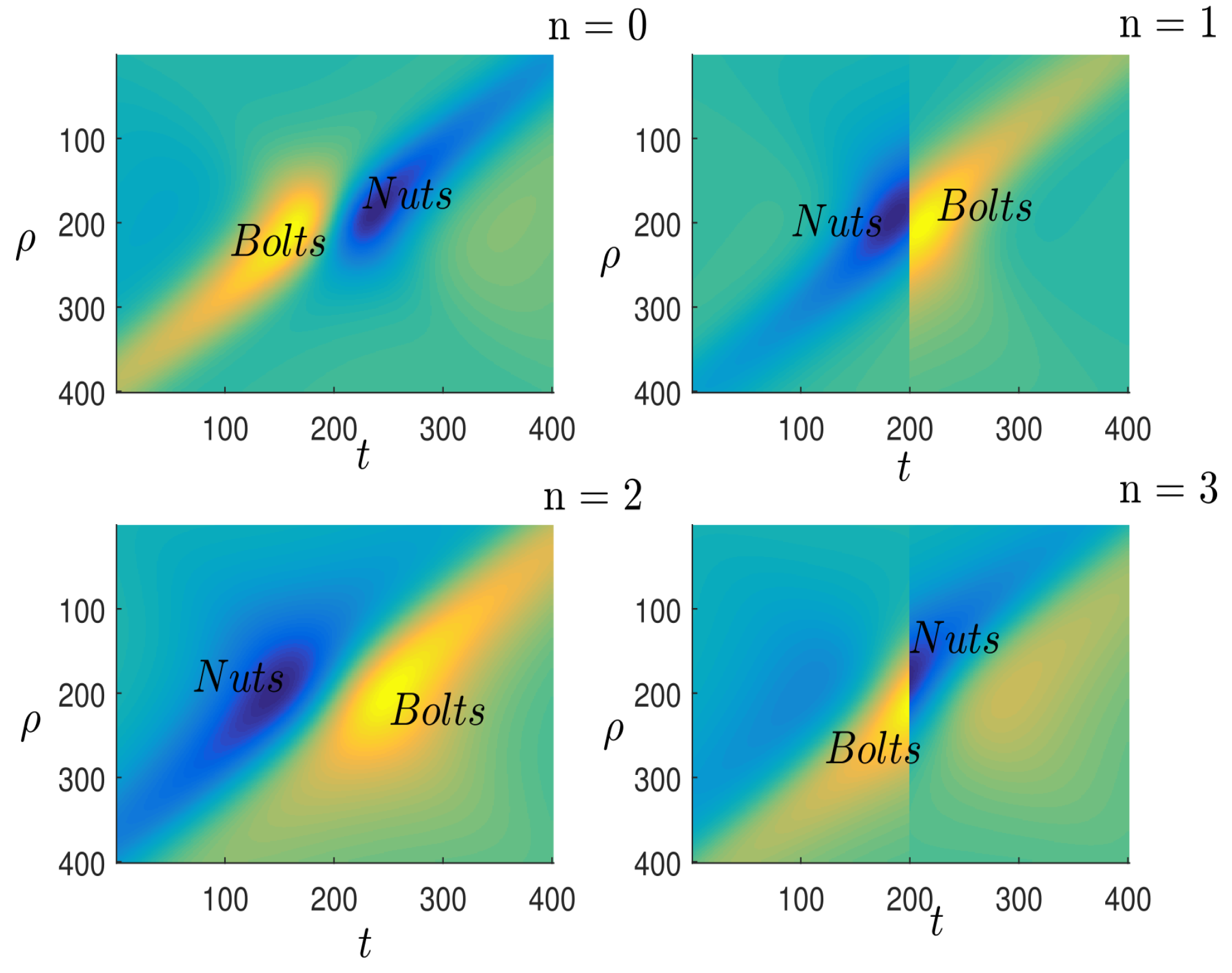

Hawking radiation: In this sub-section, we will show the different unobservable configurations that result from the formation of black holes when spacetime is treated quantum. To do this, we consider the various quantum fluctuations in the metric responsible for the phenomena mentioned above.

“Nuts and Bolts:” The presence of these two notions as unobservable configurations of black holes are in reality gravitational instantons, which are considered to be the complete, non-singular positive solutions of Einstein’s equations [

25] that play an important role in understanding the decay of baryons into leptons. In addition, these two notions will provide ample information for understanding the presence of entropy per baryon in the universe. In this procedure, we consider the various physical quantities

are

that we have mentioned and the boundary conditions [

26]. Based on the various assumptions, we obtain the following configurations:

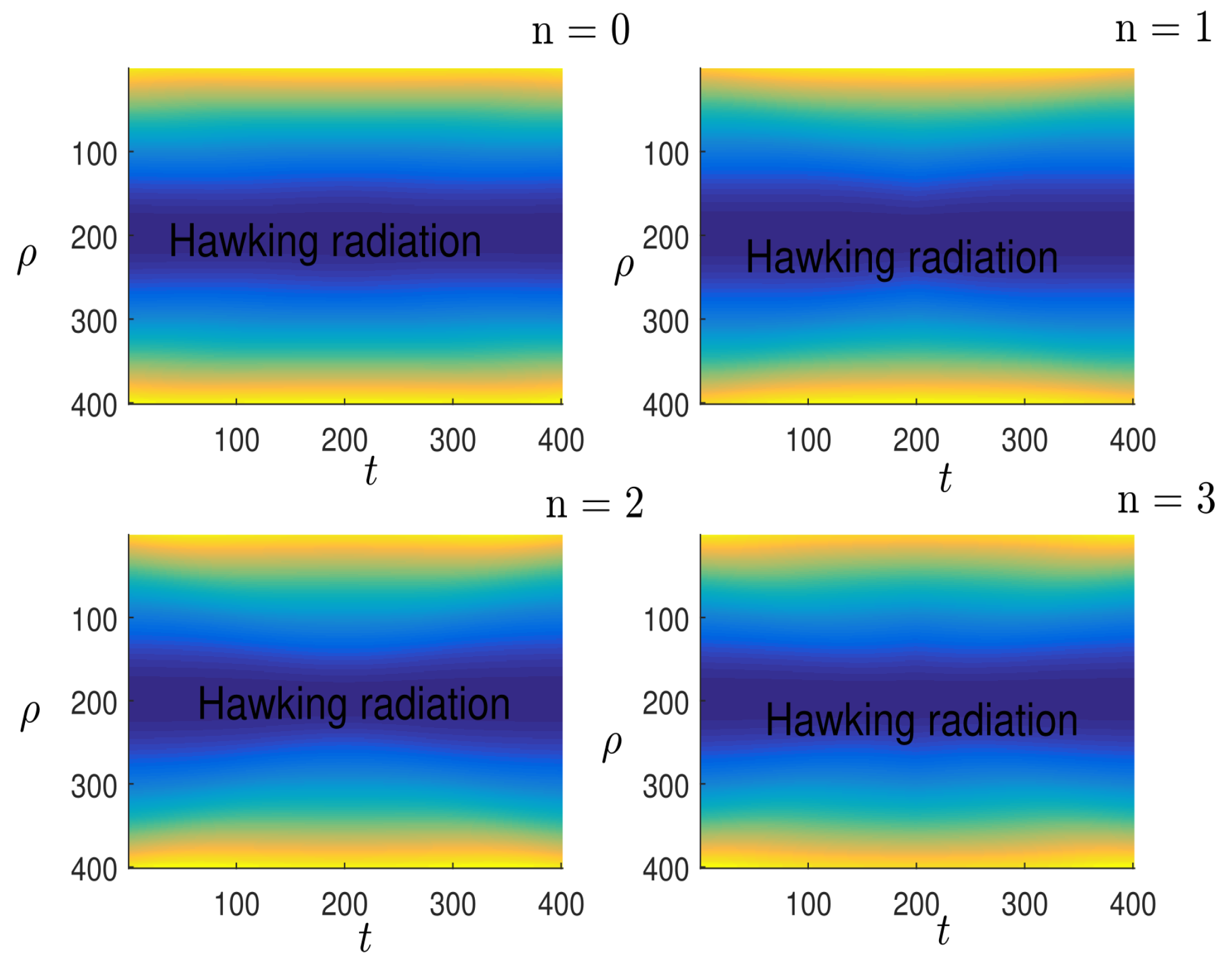

Before making any comments, please note that the coordinates

t and

given in the legend do not correspond to current measurements. They have been included for illustrative purposes. This curve is best illustrated by embedding the two-dimensional space in a three-dimensional Euclidean space [

27]. Looking at

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, we can see that they have identical properties with respect to each symmetry considered. We note, however, that these phenomena can disappear when the fluctuation present in the metric becomes significant. If we take Hawking’s [

28] hypothesis into account, these two phenomena will disappear as the distances become larger and larger. In our situation, these two phenomena will automatically disappear if we increase the gravitational field “

” while maintaining the distances considered. This experiment can be interpreted as the presence of matter and antimatter in Einstein and Rosen’s spacetime [

19], propagating as the pair of

[

20,

29].

“Wormholes:” This notion has found further explanation in the case of Schwarzchild black hole solutions in general relativity theory, with incredible [

8,

30,

31] properties. We know that this phenomenon is much more closely related to the behavior of spacetime in general relativity theory. So in our situation we are going to step outside the framework of Schwarzchild spacetime to investigate the possibility of such a phenomenon in Einstein and Rosen spacetime [

19]. In this investigation, we will not be interested in the transversality of this phenomenon as studied [

30,

31] but rather how information falling into a black hole in d’Einstein and Rosen spacetime [

19] must emerge as an

pair [

13,

32]. In this demonstration, it is important to cut up the Einstein and Rosen spacetime [

19] and study each compartment. We introduce the metric of Einstein and Rosen [

19] as well as the quantities of matter

of which we present the following different expressions:

In this dynamic, we are going to focus more on the

and

components to understand how information falls into a black hole in Einstein and Rosen’s spacetime [

19] must emerge as an

pair [

13,

32]. We emphasize, that the

component could play a very large role in the investigation of the energy [

33] necessary for the “Wormholes” to be traversable in the Einstein and Rosen spacetime [

19] whose development is in progress. Using similar conditions for

Figure 3 and

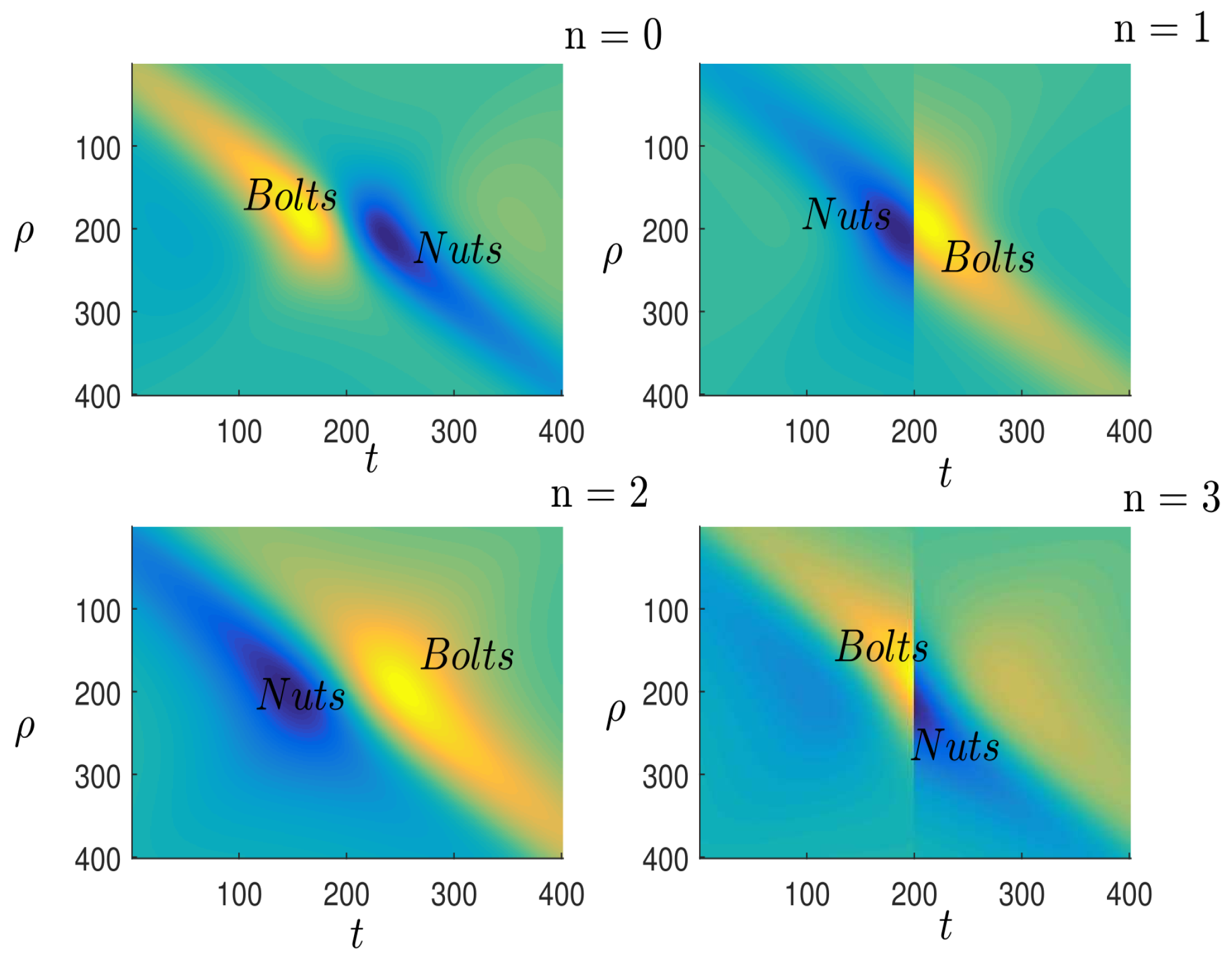

Figure 4, we obtain the following configurations:

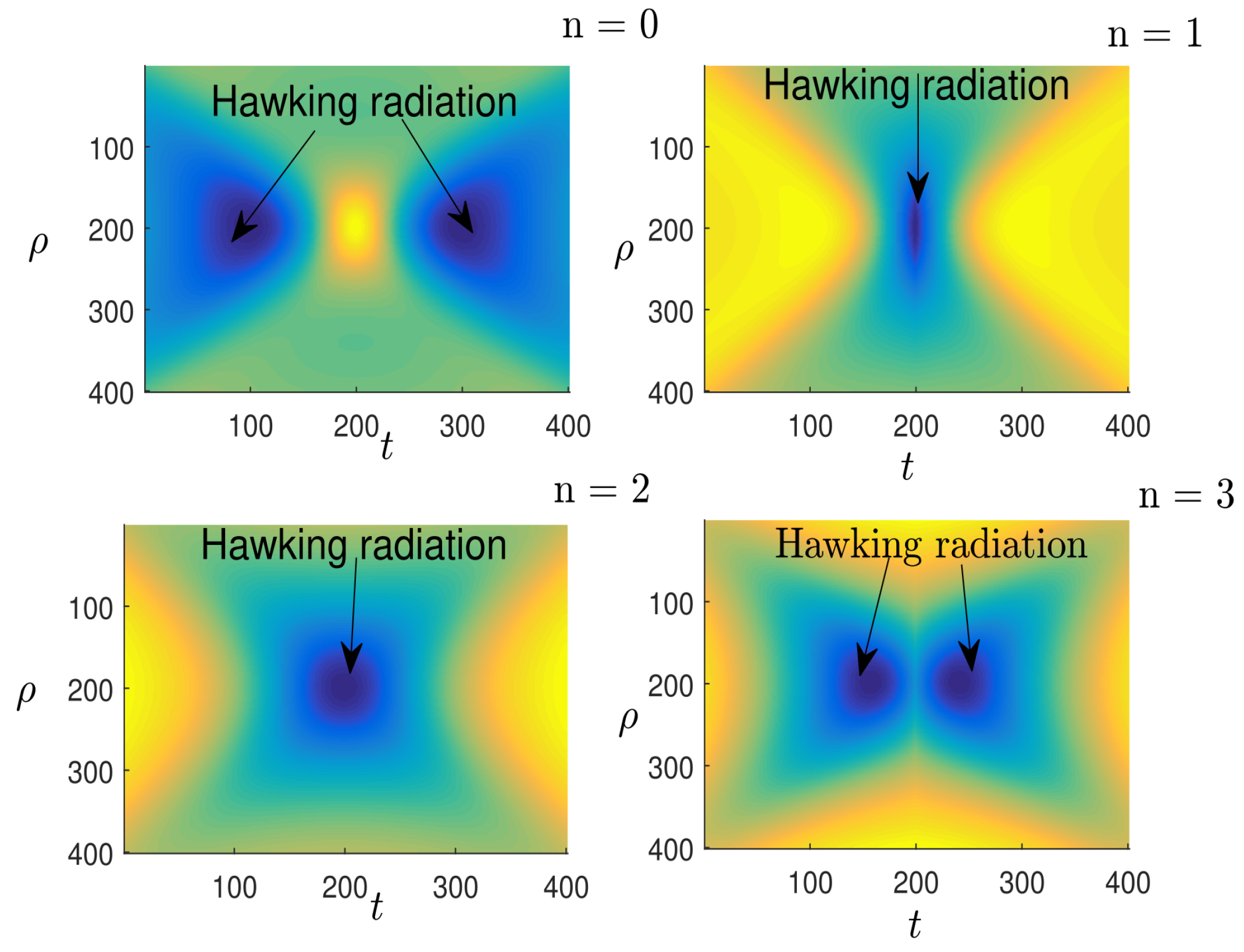

Looking at

Figure 5, we see that the Einstein and Rosen bridge [

34] has completely disappeared, giving way to large singularity-free empty spaces. These empty spaces demonstrate the evaporation and gradual disappearance of the Hawking black hole [

5]. Using the hypothesis [

13], we can otherwise interpret

Figure 5 as the entanglement model for a collection of Bell pairs. In this case, we notice that the Einstein and Rosen bridge [

34] is in a scrambled state. We note that, for different values of

n, the observed surface of the black hole does not change for a given state of the gravitational field. This result confirms Hawking’s [

35] hypothesis that the surface cannot decrease with time.

Figure 6 shows impassable “wormholes” with singularity-free empty spaces on both sides, and we find that these empty spaces are linked by the Einstein and Rosen bridge [

34]. This configuration demonstrates how information from the black hole propagates in the form of Hawking radiation [

5]. We find that these “wormholes” are in fact a pair of

that can link and unlink.

3. Conclusions

Ultimately, our aim was to demonstrate the existence of quantum gravity within the theory of general relativity through the new equation

. In this investigation, we used the Einstein and Rosen metric [

19] coupled to

phenomena [

20] to demonstrate the uniqueness between general relativity theory and quantum mechanics in the case of black holes. In this dynamic, we succeeded in recovering results identical to those for the equation

obtained by Maldacena and Susskind [

13]. Importantly, we obtained the presence of gravitons in Einstein and Rosen spacetime [

19] as treated by Feynman [

36]. Obtaining “wormholes” has confirmed Wheeler’s hypothesis [

8] about the quantization of general relativity. We were able to show that gravitational waves [

1,

4,

9,

10,

11,

12,

17,

23,

24] and Hawking radiation [

5,

6,

25,

28,

32,

35] are linked by the

phenomenon [

20]. In this investigation, we draw attention to the detection of gravitational waves as observed by the LIGO science team, which is linked to an EPR entanglement that, thanks to their mutual quantum interactions and their difference in the way the gravitational waves propagate through spacetime as mentioned in

Figure 1, allows us to obtain signals considered in

Figure 2 that could play a crucial role in terms of sensitivity at the quantum level gravitational waves detectors [

37]. Although we have used spacetime as a means of probing the quantum nature of gravity by virtue of the intrinsically quantum properties of entanglement [

38], taking this assumption into account as a fundamental element of quantum gravity leads to a result whereby the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics and Everett’s relative state formulation are complementary descriptions, as Susskind [

39] points out. The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics can be verified through the structure of the “wormholes”, as expanded in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, characterizing the Heisenberg principle, which is corroborated by the collapse of the wave function of entangled particles [

40]. Furthermore, we find that the exchange of virtual gravitons in Einstein and Rosen spacetime [

19] is equivalent to connections “wormholes” content in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 [

40,

41]. It is important to stress that the fact that quantum gravity can integrate the foundations of quantum mechanics is due to the fact that the metric possesses essentially non-local properties, which in an adapted mathematical formalism [

18] allows the singularities of Planck-scale relativity theory to be eliminated [

40,

41]. This absence of singularity on the Planck scale makes it possible to observe the notion of matter and antimatter developed in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, and confirms the immense secret unexplored by the theory of general relativity [

42]. It is important to point out that other approaches to the quantum nature of gravity, such as that of Oppenheim et al. [

43,

44], explain the measurements observed in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, which are due to the fact that Einstein’s theory of gravity interacts with quantum matter. In this investigation, Oppenheim et al. [

43,

44] demonstrate in a very complex mathematical formalism that the fact that two systems interact, one classically and the other quantum-like, results in decoherence of the quantum system and a break in predictability in classical phase space. It is clear that we can observe such behavior in the measurements of

t and

contained in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. The fact that we use (ISM) Pomerasnky’s [

18] as a mathematical formalism has enabled us to treat spacetime in a quantum way, and to confirm the hypothesis that the gravitational soliton plays the role of field and matter [

45], making it easier to understand the various phenomena discussed in this letter.