Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Hybrid Excitation Generator Design Mechanism

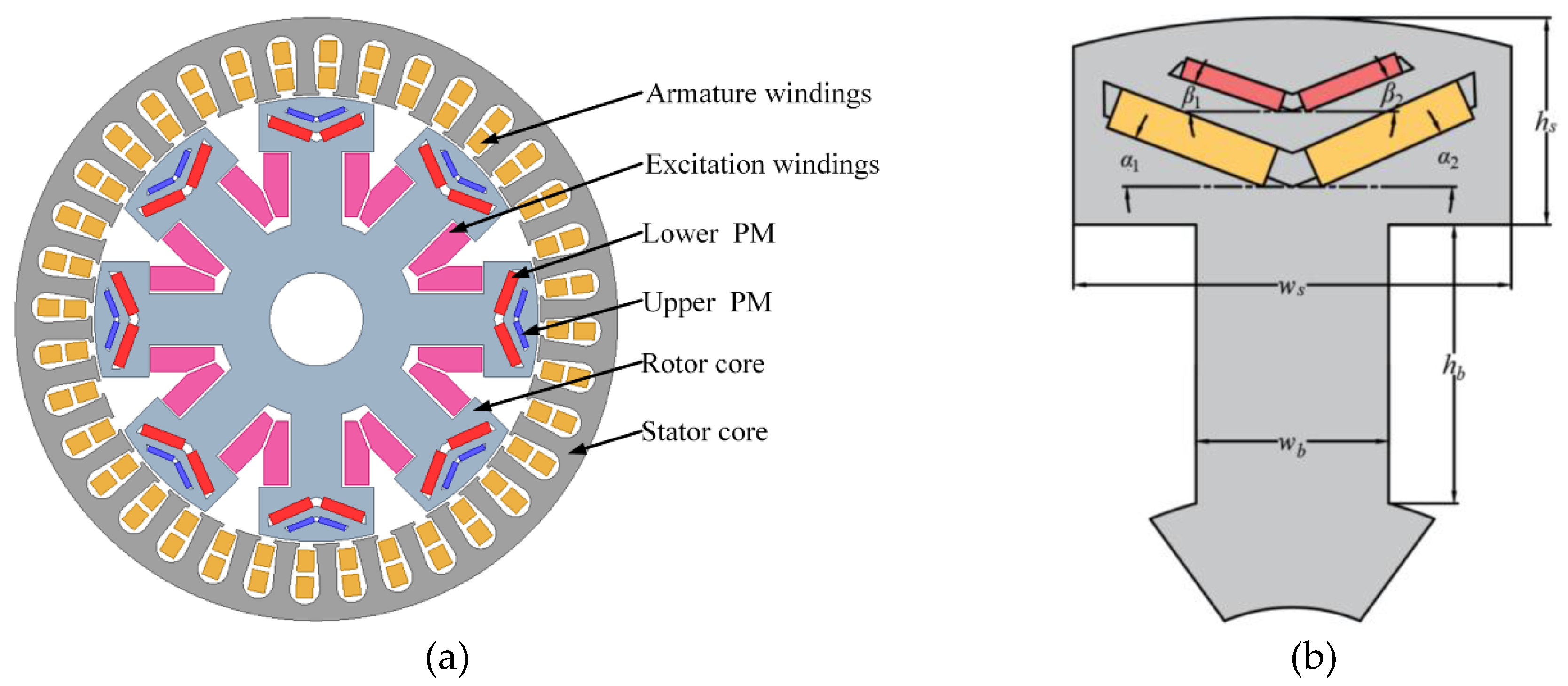

2.1. Hybrid Excitation Generator Structure Design

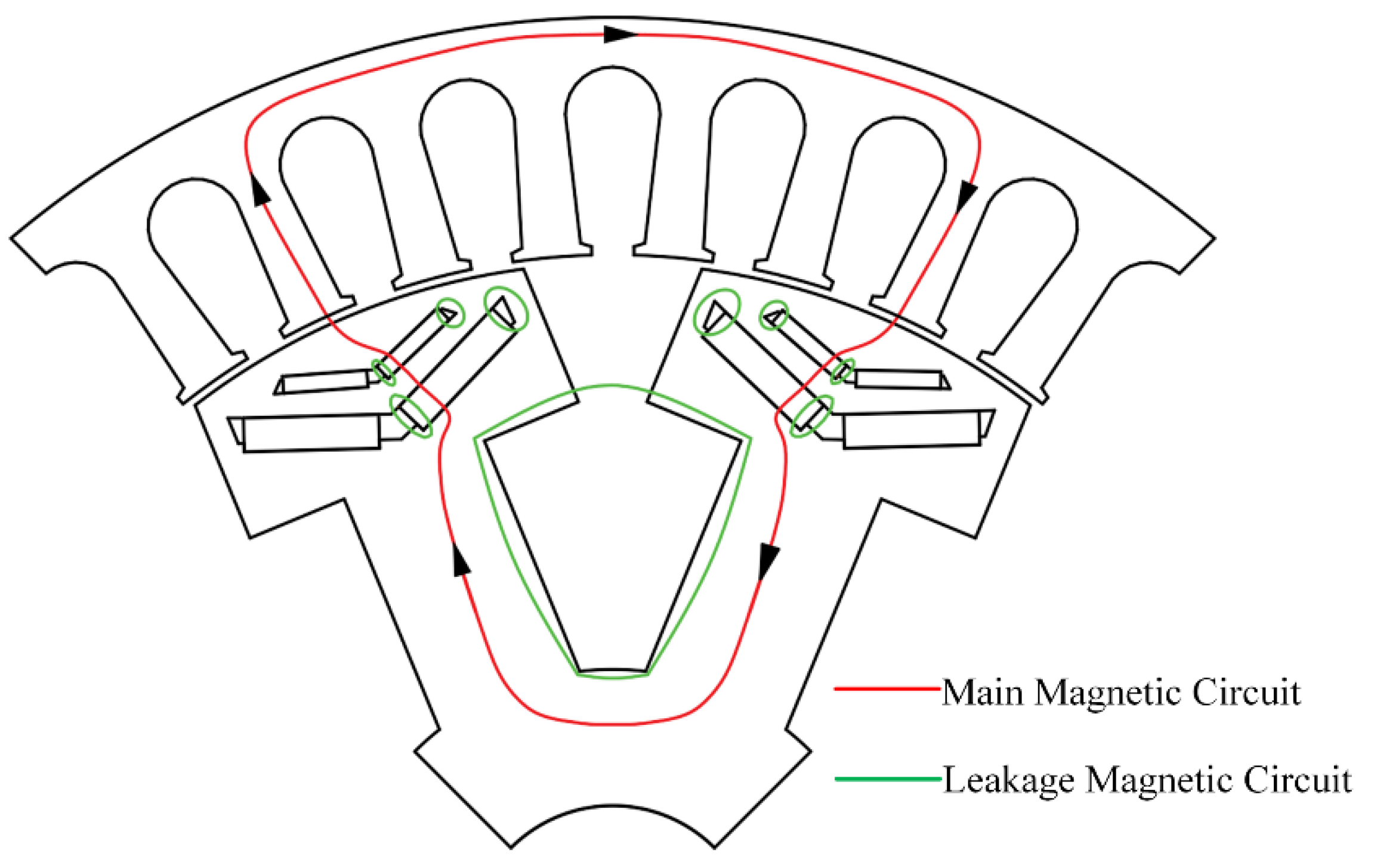

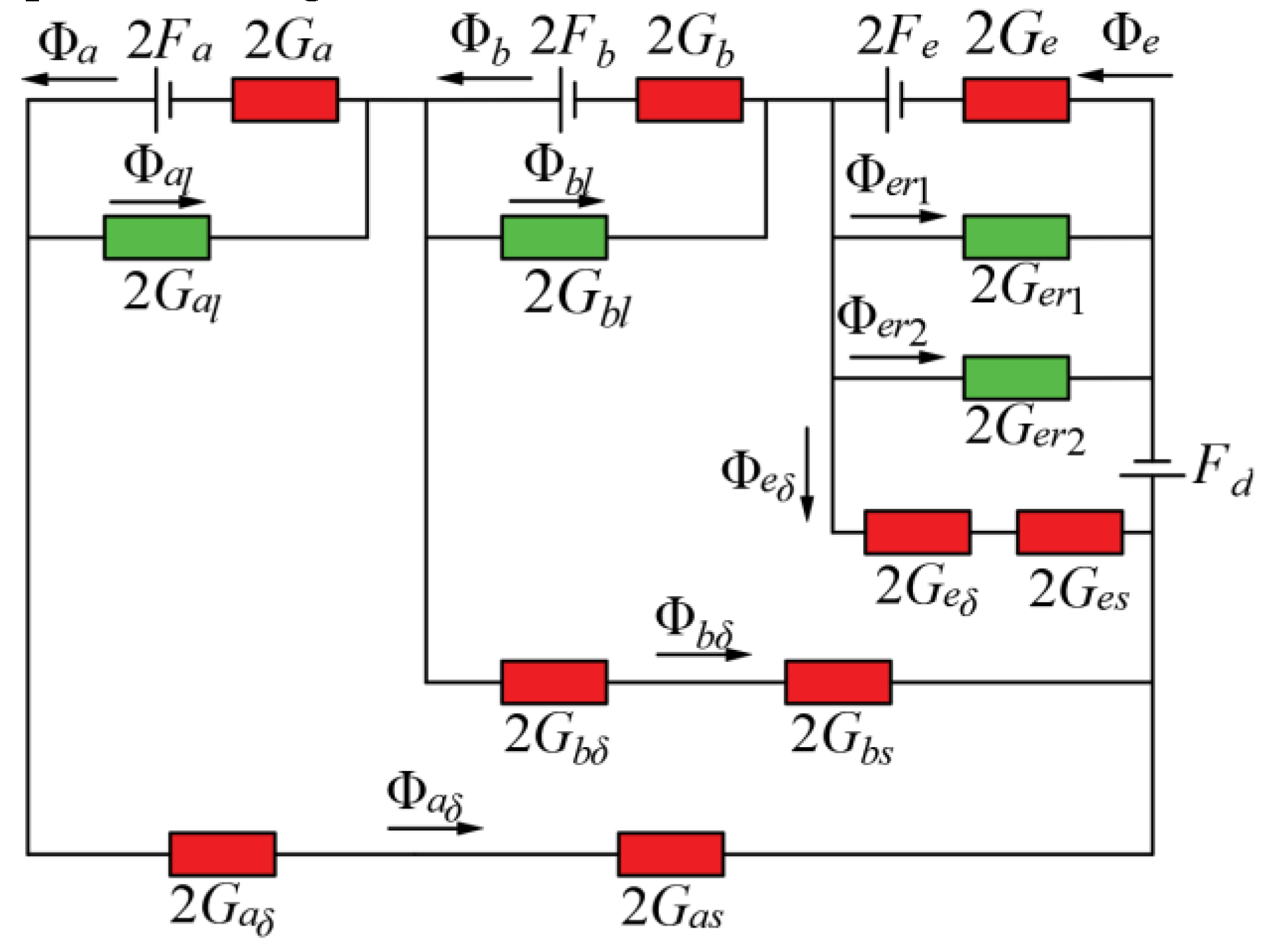

2.2. Magnetic Circuit Analysis of Hybrid Excitation Generator

3. Electromagnetic Performance Optimization Analysis

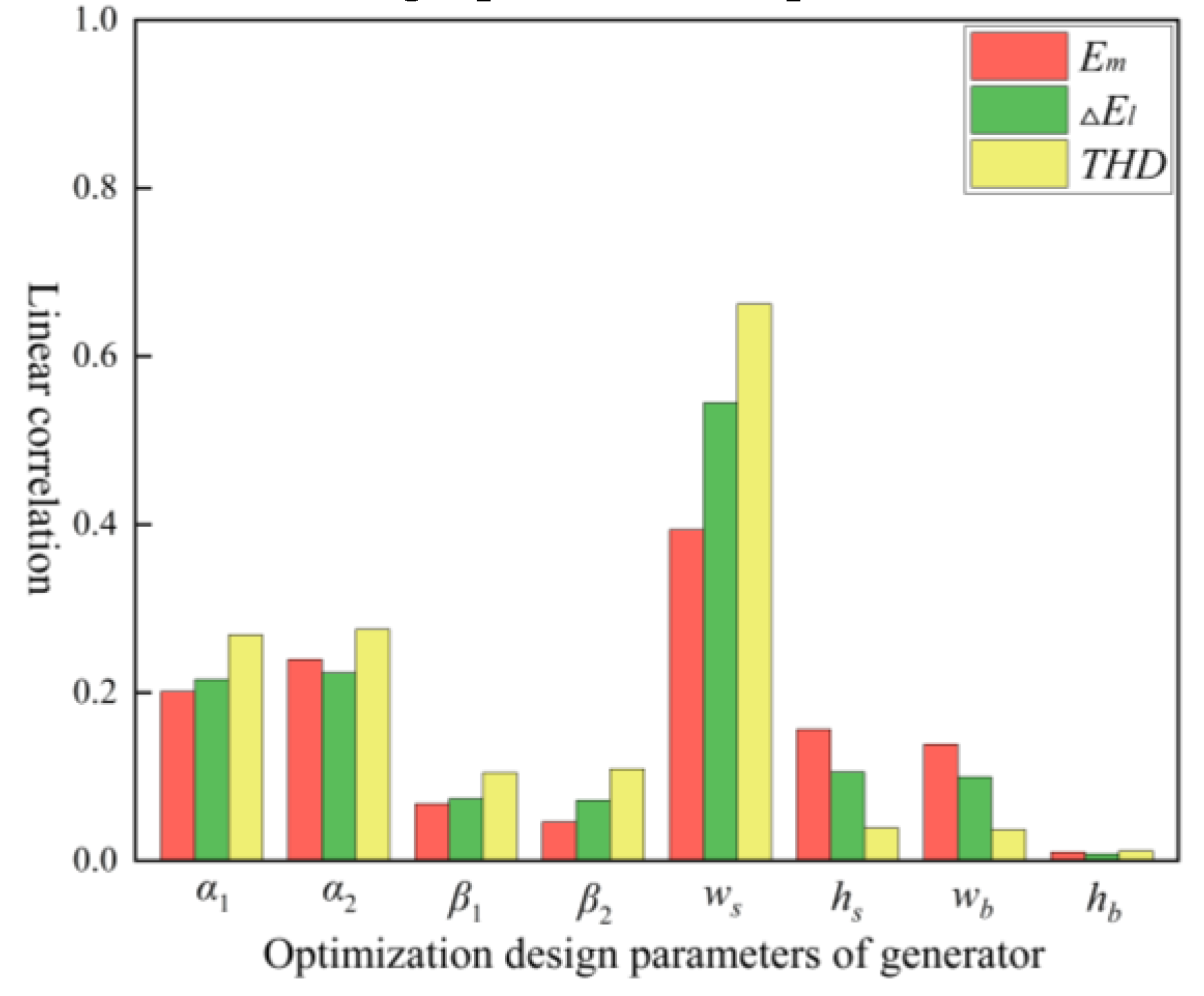

3.1. Sensitivity Analysis

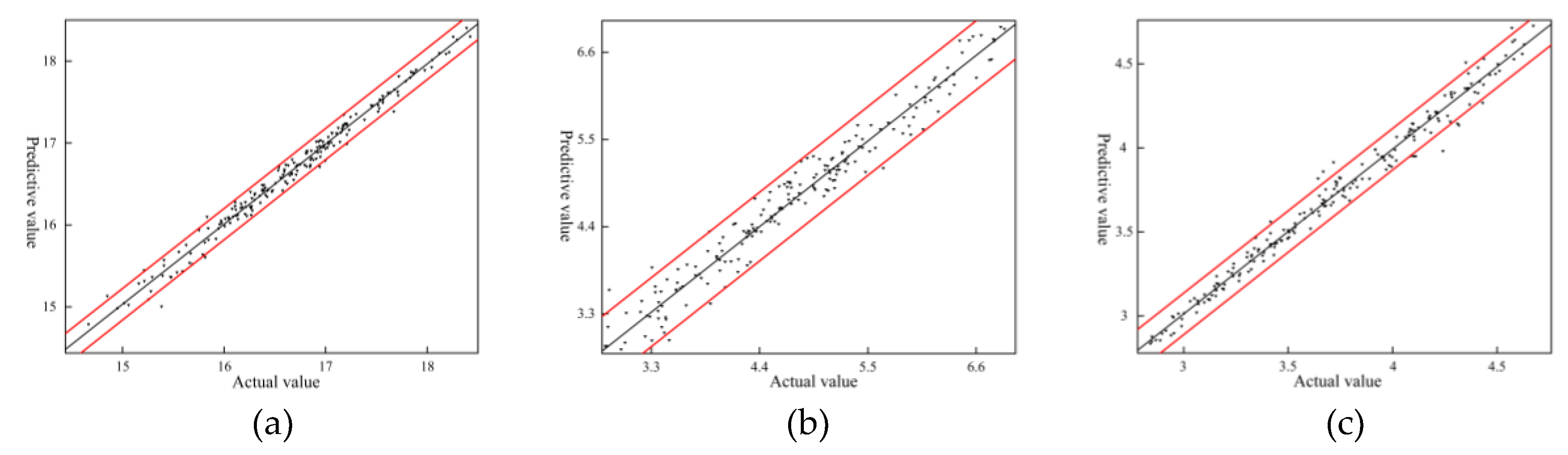

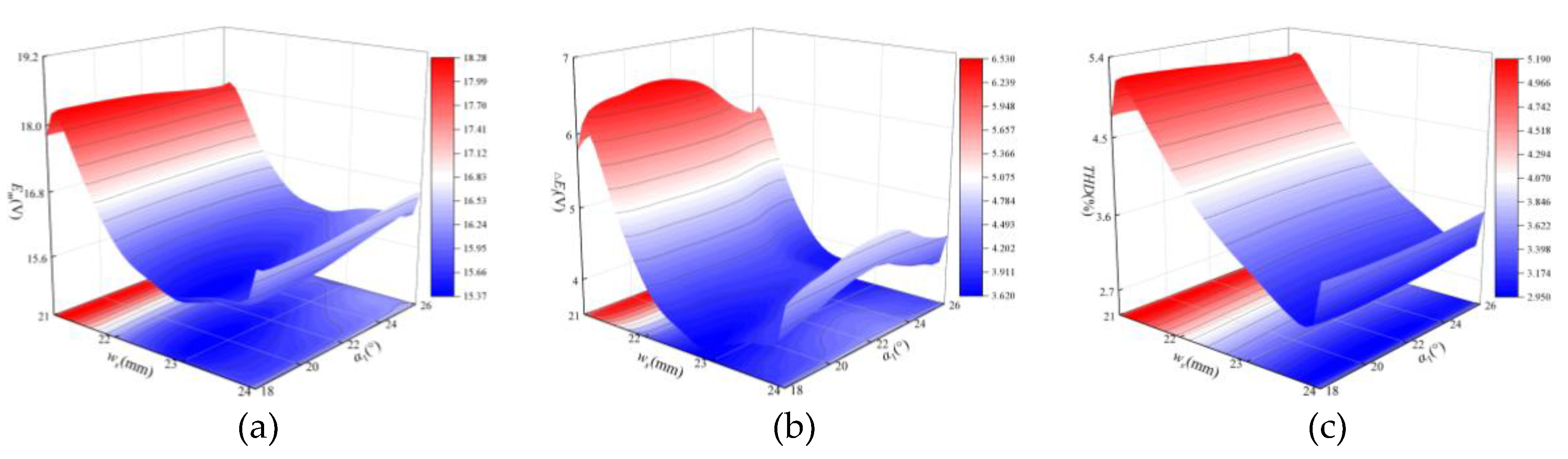

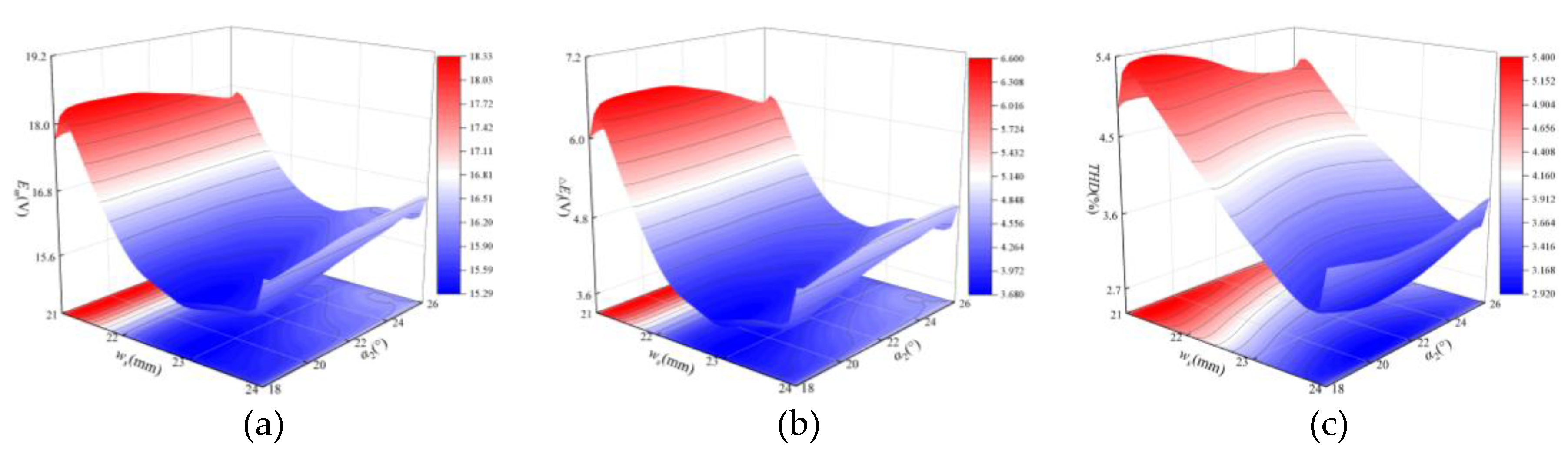

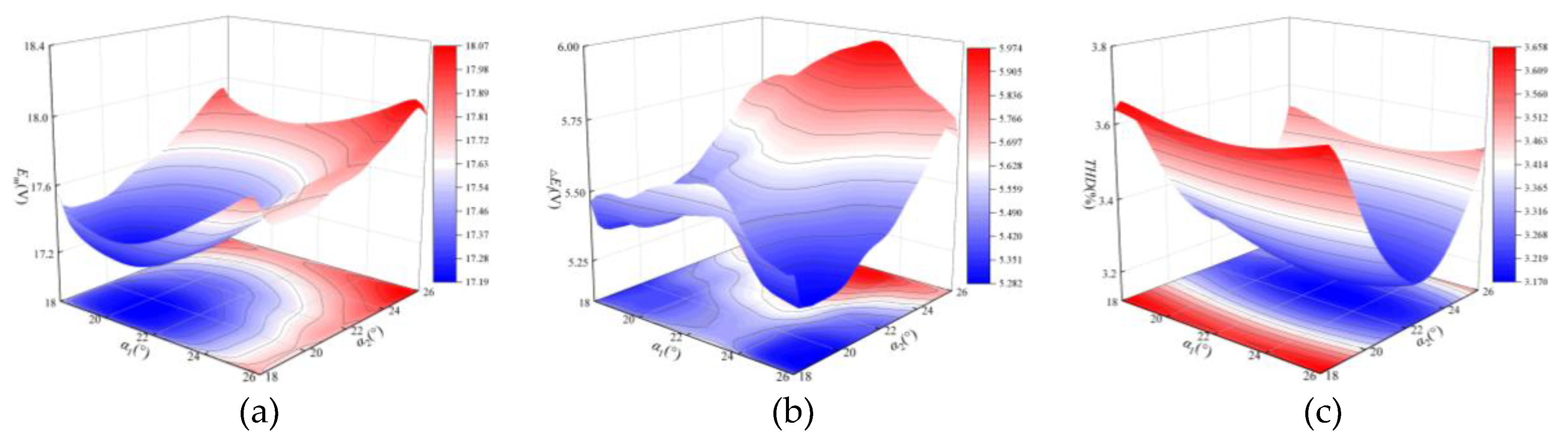

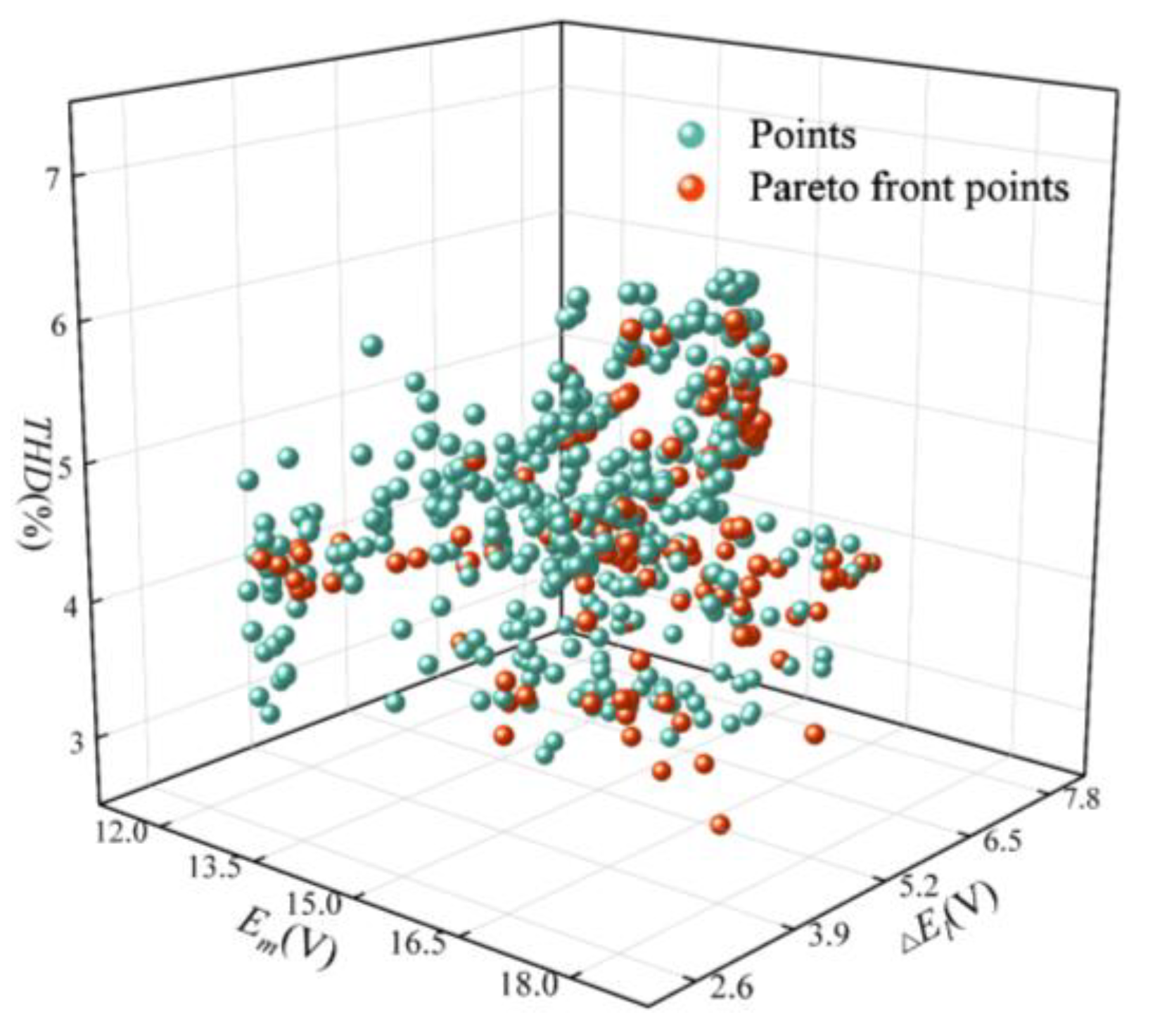

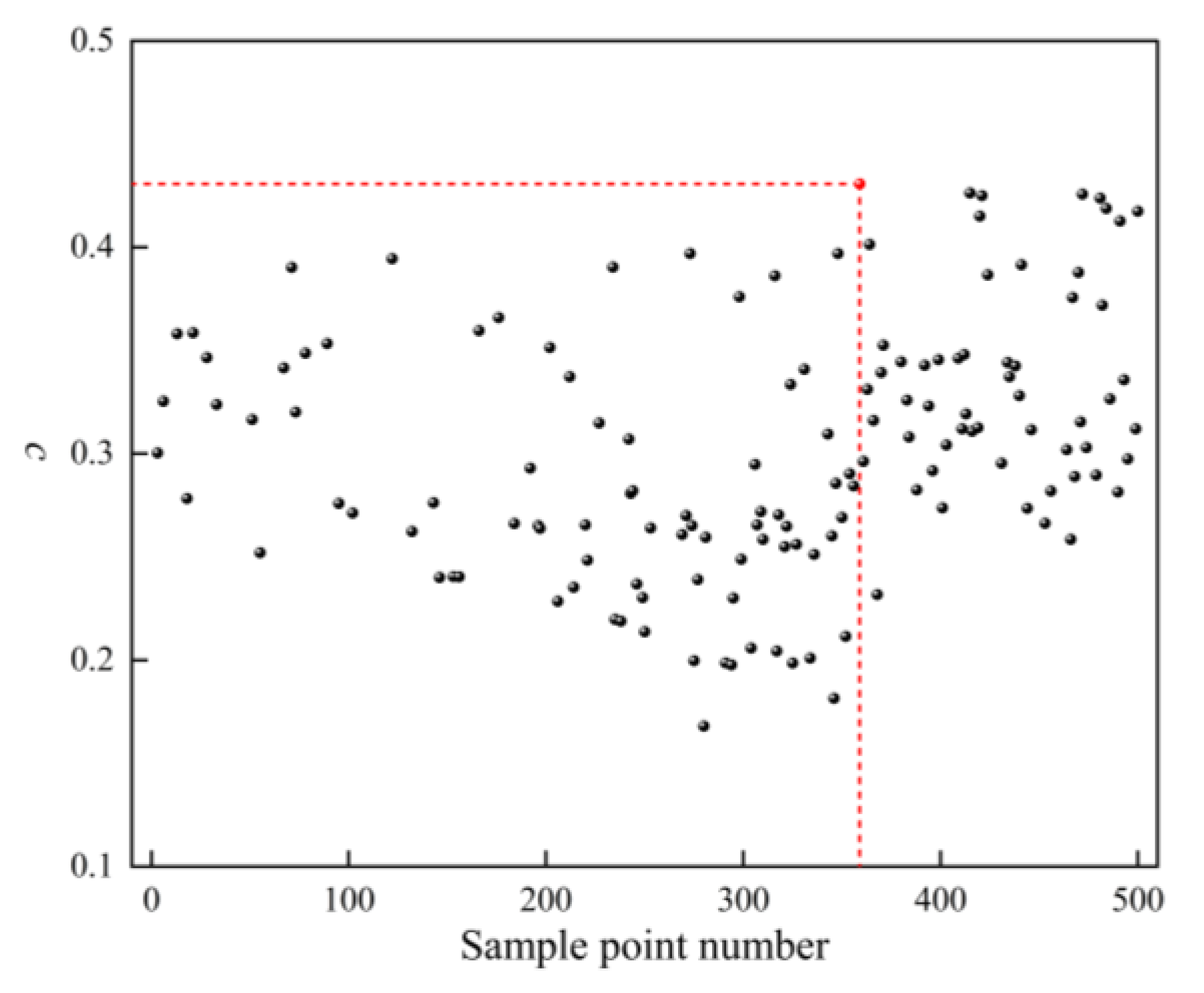

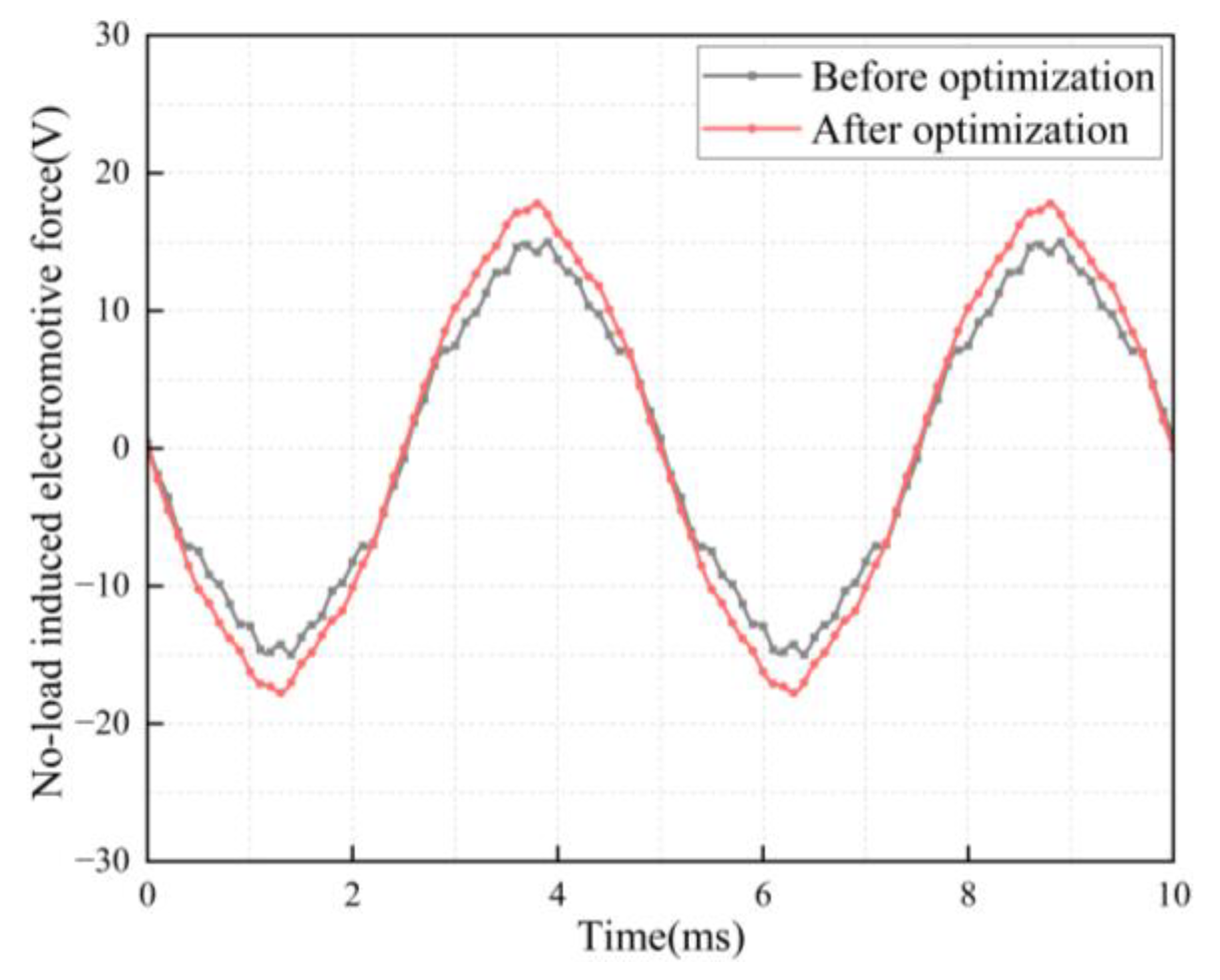

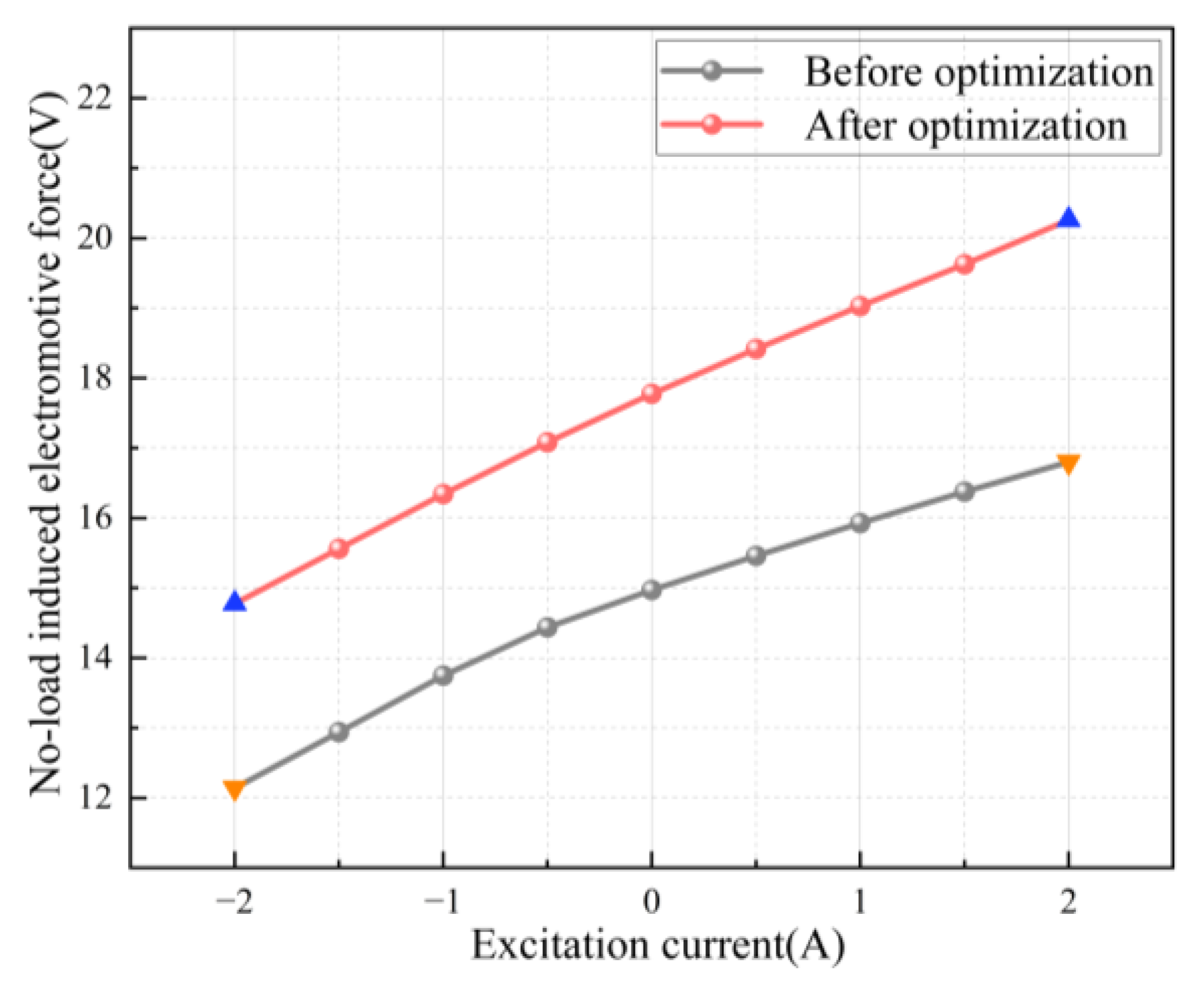

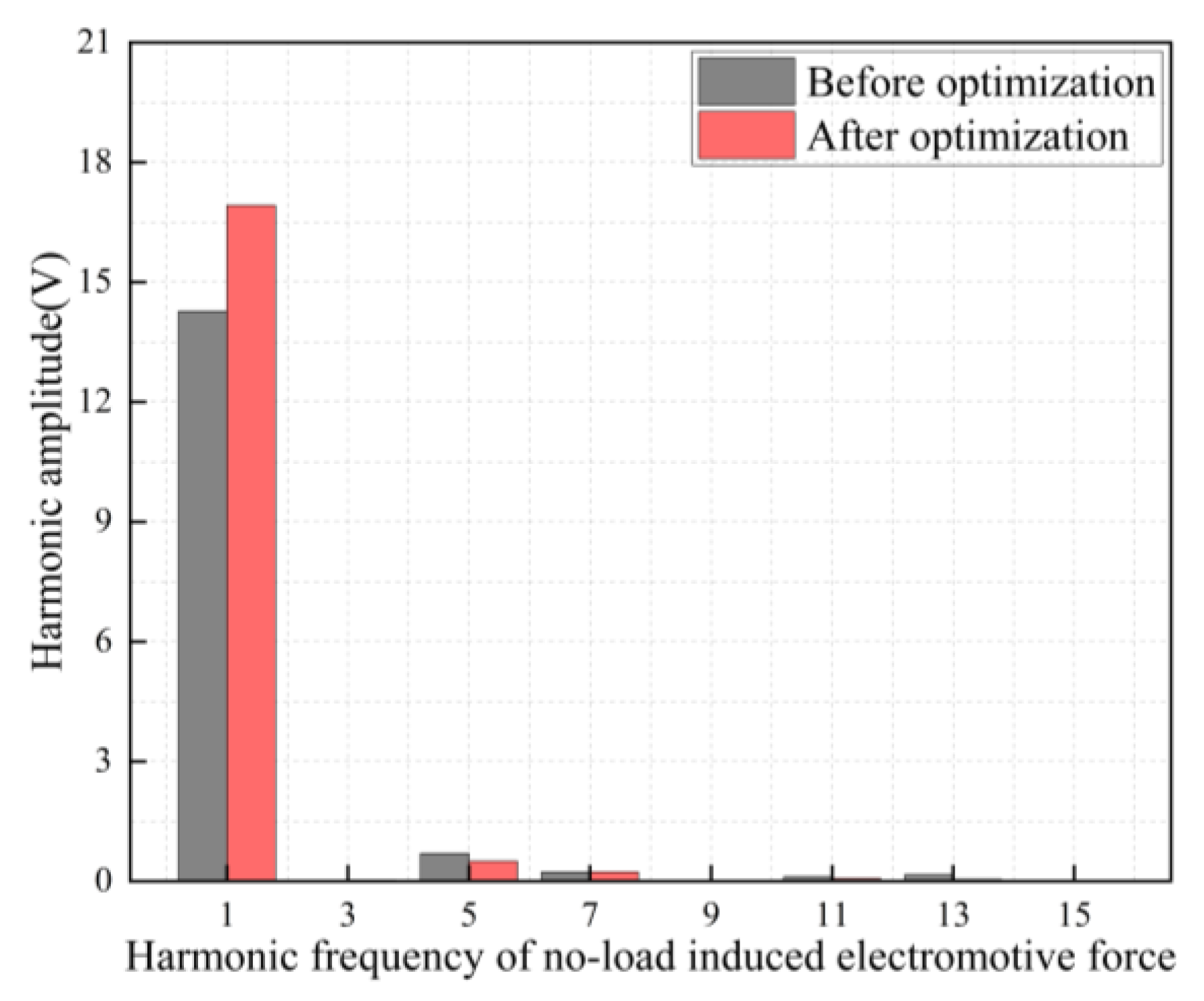

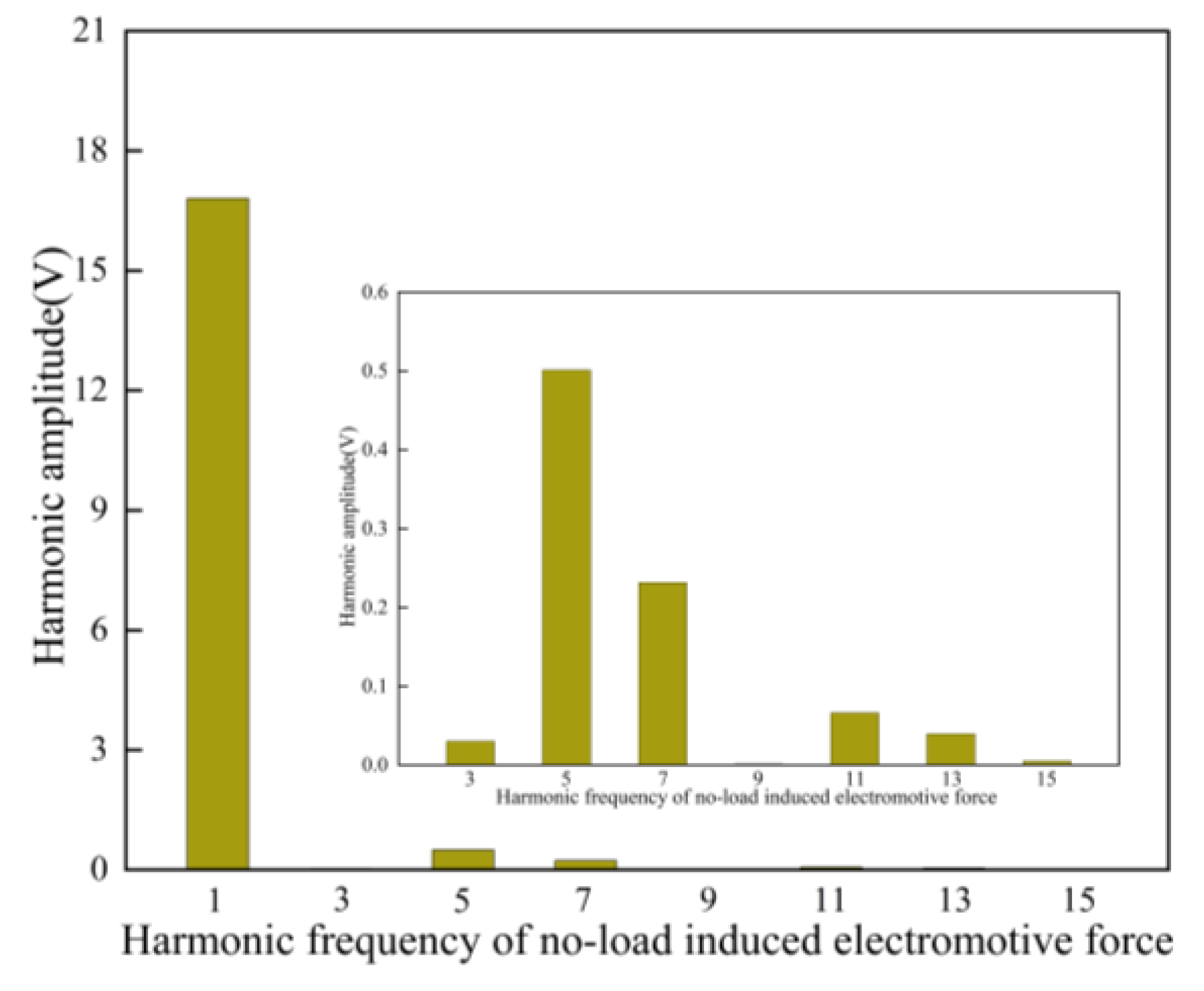

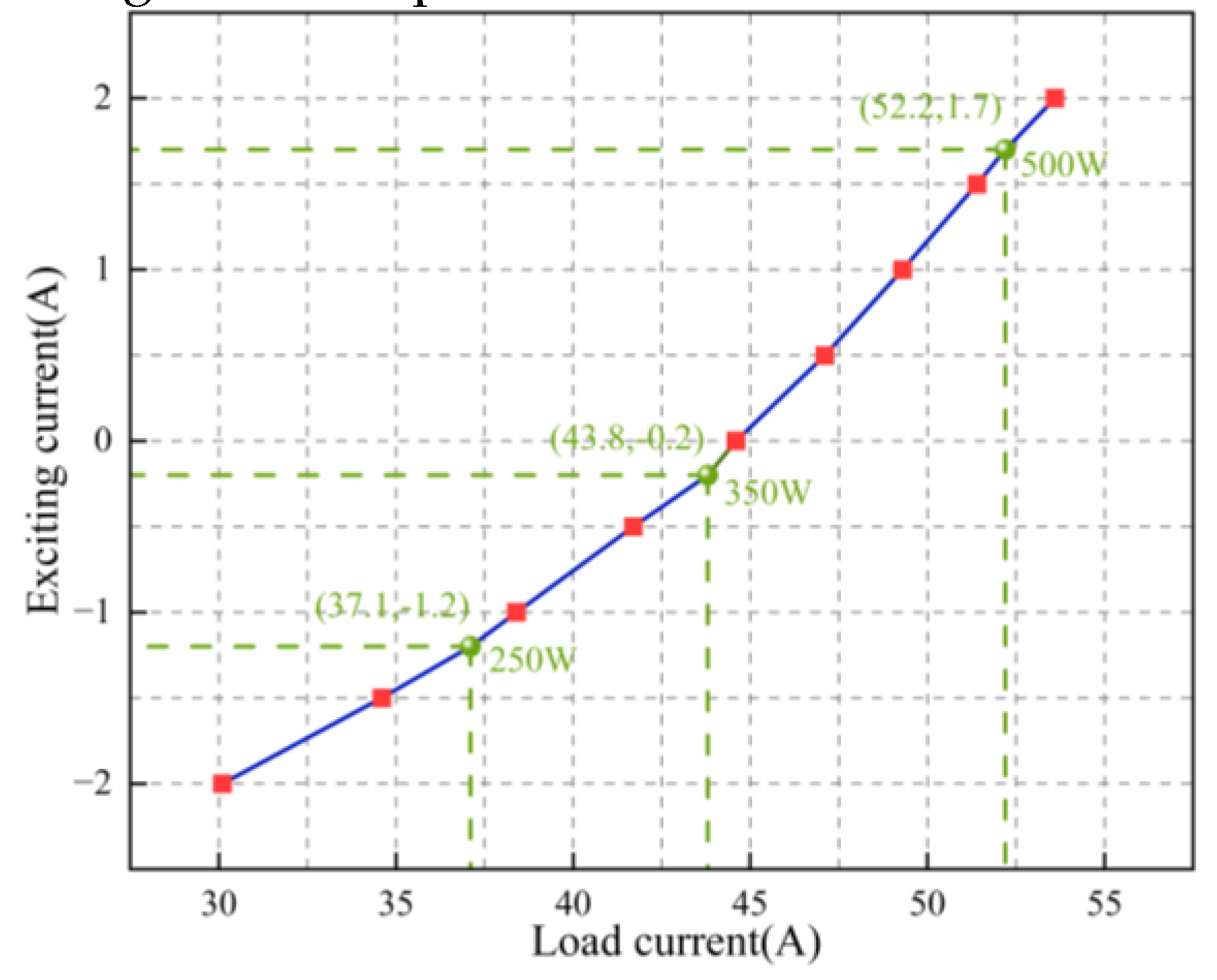

3.2. Multi-objective Optimization and Verification

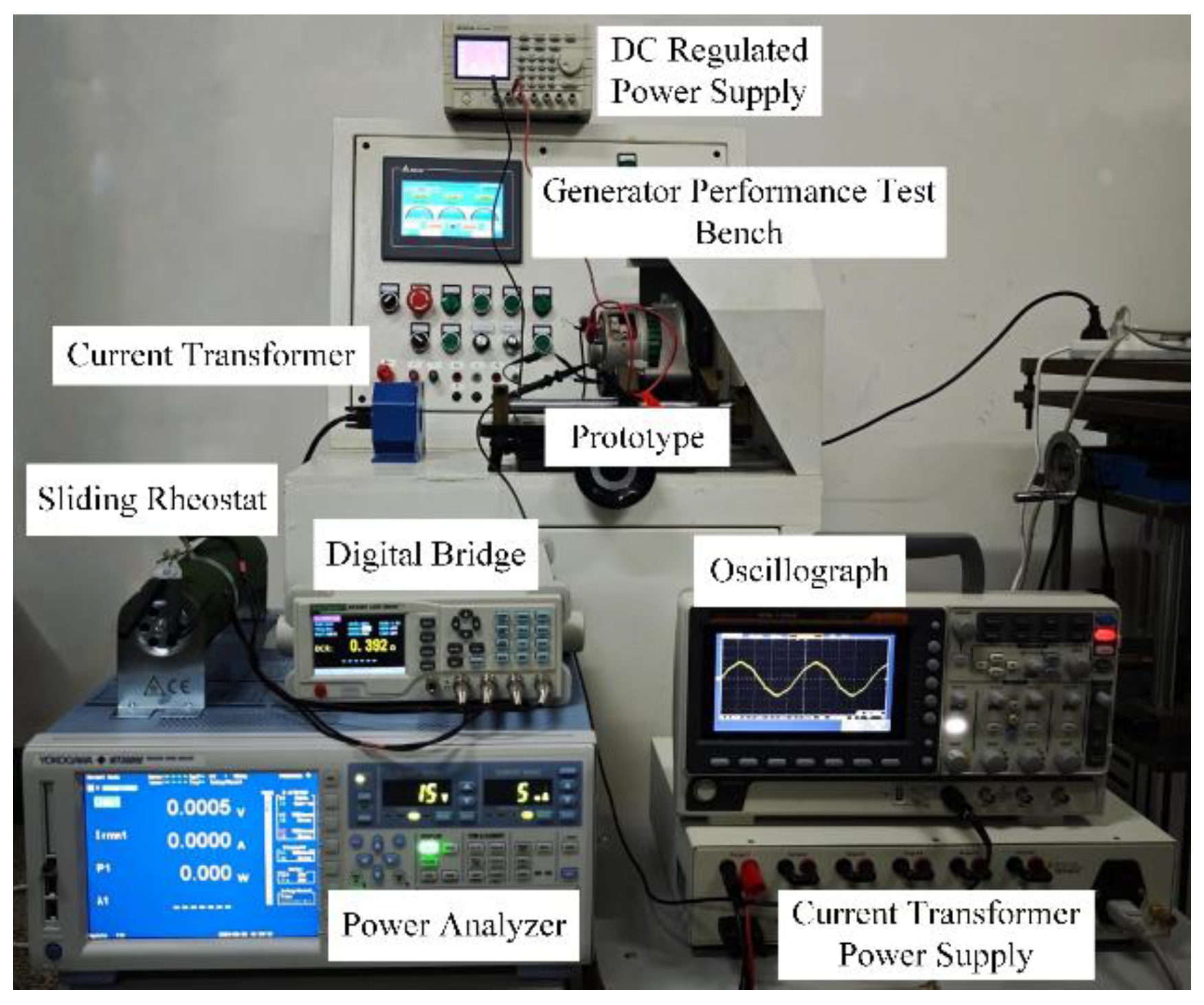

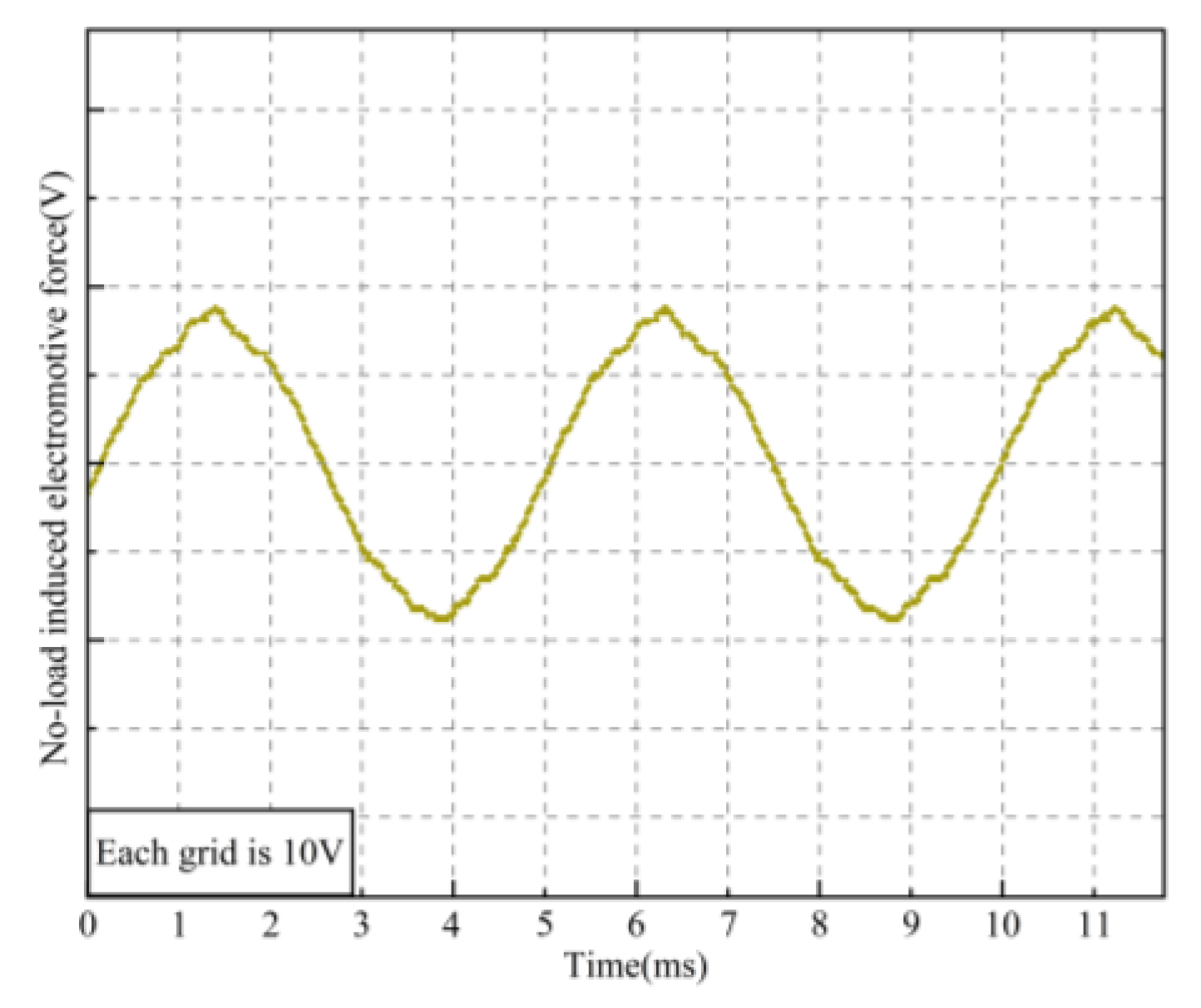

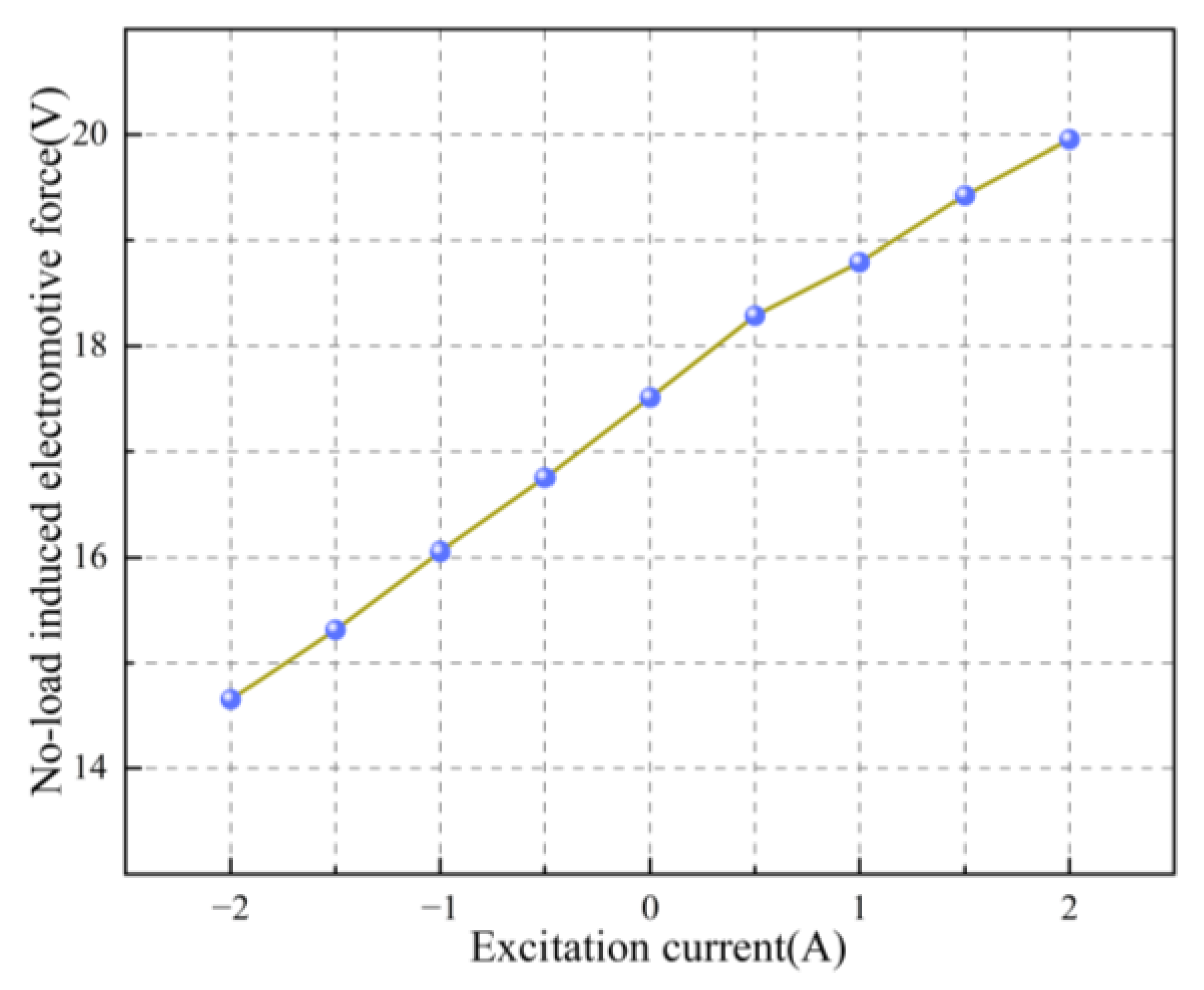

4. Experimental verification

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Y.; Mo, C.; Zhu, W.; Chen, J.; Wu, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L. Design and Test for a New Type of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator Applied in Tidal Current Energy System. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Wang, D. A Novel Design Method of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator From Perspective of Permanent Magnet Material Saving. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2017, 32, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Du, Q.; Ma, S.; Geng, H.; Hu, W.; Li, Z.; Liu, G. Permeance Analysis and Calculation of the Double-Radial Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Voltage-Stabilizing Generation Device. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 23939–23947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Zuo, S.; Wu, X.; Wu, S.; Sun, H. Analytic Model of Air Gap Magnetic Field and Radial Electromagnetic Force for Electric Excitation Claw Pole Alternator. Transactions of China Electrotechnical Society 2017, 32, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Han, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, W.; An, J.; Yan, B. Electromagnetic characteristics analysis of E-core stator doubly salient electro-magnetic generator with short circuit. Electric Machines and Control 2020, 24, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, D.; Hua, W. Overview of Configuration, Design and Control Technology of Hybrid Excitation Machines. Proceedings of the CSEE 2020, 40, 7834–7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Du, Q.; Ma, S.; Xu, J.; Geng, H. Development of Hybrid Excitation Generator for Vehicles. Automotive Engineering 2017, 39, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, L.; Yu, L. Phase Displacement Characteristics of a Parallel Hybrid Excitation Brushless DC Generator. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2020, 35, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ren, J.; Yan, S.; Wang, L.; Pang, X.; Liu, W.; Kong, Z. Study of Electromagnetic Characteristics of Brushless Reverse Claw Pole Electromagnetic and Permanent Magnet Hybrid Excitation Generator for Automobiles. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2024, 39, 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, L.; Yan, Y. Operation Principle and Flux Regulation Characteristics of a New Parallel Hybrid Excitation Blushless DC Machine. Transactions of China Electrotechnical Society 2013, 28, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C. Investigation of Flux Regulation Performance and Experimental Validation of Novel Hybrid Excitation Brushless Claw-pole Alternators. Proceedings of the CSEE 2013, 33, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C. Structure Designing and Characteristic Study of HECPG Which Magnetic Circuit Series Connection. Transactions of China Electrotechnical Society 2009, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörée, G.; Leijon, M. Overview of Hybrid Excitation in Electrical Machines. Energies 2022, 15, 7254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, L.; Yu, L. Magnetic Field Enhancement Characteristic of an Axially Parallel Hybrid Excitation DC Generator. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2021, 57, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; Zhang, X.; Tong, L.; Ma, Q.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. Performance Optimization Analysis of Hybrid Excitation Generator With the Electromagnetic Rotor and Embedded Permanent Magnet Rotor for Vehicle. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 163640–163653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, L.; Zhang, C. Research on Rotor Pole Matching for Hybrid Excitation Synchronous Generator with Parallel Rotor Structure. Electric Machines and Control 2020, 24, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Kou, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, J. A Novel Hybrid Excitation Doubly Salient Generator with Separated Windings by PM Inserted in Stator Slot for HEVs. Energies 2022, 15, 7968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ren, J.; Yan, S.; Wang, L.; Pang, X.; Liu, W.; Kong, Z. Study of Electromagnetic Characteristics of Brushless Reverse Claw Pole Electromagnetic and Permanent Magnet Hybrid Excitation Generator for Automobiles. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2024, 39, 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, S.; Liu, C. Analysis of Operation Characteristics for Dual-Direction Hybrid Excitation Brushless DC Generator. Transactions of China Electrotechnical Society 2019, 34, 4634–4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C. Study on a hybrid excitation brushless claw-pole alternator with an annular PM between the claw poles. Journal of Electric Machines and Control 2014, 18, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yan, S.; Wei, K. Analytical Calculation of the No-Load Magnetic Field of a Hybrid Excitation Generator. Electronics 2024, 13, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, M.; Hu, W.; Geng, H.; Pang, X. Multi-Objective Optimization Design of a Segmented Asymmetric V-Type Interior Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2025, 61, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Shi, L.; Li, F.; Xu, H.; Zhou, T.; Wang, W. Characteristics Analysis of Magnetic-Pole-Shift in an Asymmetric Hybrid Pole-Permanent Magnet-Assisted Synchronous Reluctance Motor. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics 2025, 13, 1394–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Jewell, G.W.; Chen, J.; Wu, D.; Gong, L. A Novel Asymmetric Rotor Interior Permanent Magnet Machine With Hybrid-Layer Permanent Magnets. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2021, 57, 5993–6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, K.; Zhu, S.; Liu, C. Consequent-pole Hybrid Excitation Brushless DC Generator Based on Integrated Induction. Proceedings of the CSEE 2022, 42, 4209–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Li, X.; Qi, X.; Tao, C.; Gao, P. Analysis of torque ripple of the interior permanent magnet synchronous motor with asymmetric V-pole offset. Electric Machines and Control 2021, 25, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Yu, P.; Zhang, G. Structure and Voltage Regulation Analysis of a Parallel Hybrid Excitation Synchronous Generator Based on Double-pole Induction. Proceedings of the CSEE 2020, 40, 7890–7898, 8226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Yan, B.; Zhang, W.; An, J.; Ding, F.; Bian, Y. Electromagnetic characteristics analysis of electric excitation segmental rotor flux-switching generator. Journal of Electric Machines and Control 2021, 25, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Jiang, S.Z.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Chan, C.C. Analytical Modeling of Open-Circuit Air-Gap Field Distributions in Multisegment and Multilayer Interior Permanent-Magnet Machines. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2009, 45, 3121–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Gao, J.; Li, M.; Yao, P.; Song, Z.; Yang, K.; Gao, X. Optimization Design of Halbach Interior Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Based on Parameter Sensitivity Stratification. Journal of Xi’an Jiaotong University 2022, 56, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, L.; Wang, X.; Dai, Z. Parameter optimization design of double-layer magnets permanent magnet synchronous motor for vehicles based on multi-round evolutionary algorithm. Science Technology and Engineering 2024, 24, 9891–9898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, F. Rotor Strength Optimization of Surface Mount High Speed Permanent Magnet Motor Based on FEM/Kriging Approximate Model and Evolutionary Algorithm. Transactions of China Electrotechnical Society 2023, 38, 936–944, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Ma, S.; Li, C.; Wu, Y.; Ma, J. Optimization and Design of Built-In U-Shaped Permanent Magnet and Salient-Pole Electromagnetic Hybrid Excitation Generator for Vehicles. Symmetry 2025, 17, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, K. Optimization and analysis of interior permanent magnet drive motor with unequal thickness magnetic poles for electric vehicle. Journal of Hebei University of Science and Technology 2025, 46, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters (Unit) | Value | Parameters (Unit) | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rated power (W) | 500 | Slot number | 36 |

| Rated speed (r/min) | 4000 | Stator outer diameter (mm) | 110 |

| Rated voltage (V) | 14 | Stator inner diameter (mm) | 82 |

| Axial length (mm) | 25 | Rotor outer diameter (mm) | 81 |

| Pole number | 8 | Rotor inner diameter (mm) | 17 |

| Parameters (Unit) | Range of values |

|---|---|

| α1(°) | 18~26 |

| α2(°) | 18~26 |

| β1(°) | 17~22 |

| β2(°) | 17~22 |

| ws(mm) | 21~24 |

| hs(mm) | 7.5~11 |

| wb(mm) | 7~10.5 |

| hb(mm) | 13~16.5 |

| entry 2 | data 1 |

| Optimization objectives | TSS | RSS | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Em | 347.09 | 4.71 | 1.36 |

| △El | 230.55 | 9.51 | 4.13 |

| THD | 118.18 | 1.82 | 1.54 |

| Serial numbers | ws (mm) | α1 (°) | α2 (°) | Em (V) | △El (V) | THD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 21.041 | 20.3825 | 22.518 | 18.159 | 3.840 | 4.918 |

| 6 | 22.169 | 19.963 | 23.183 | 14.025 | 4.851 | 2.991 |

| 13 | 23.266 | 19.403 | 25.523 | 15.989 | 4.677 | 3.325 |

| ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| 495 | 22.212 | 19.513 | 18.868 | 18.312 | 3.813 | 5.022 |

| 499 | 24.110 | 25.989 | 19.041 | 15.579 | 3.674 | 3.513 |

| 500 | 21.402 | 23.062 | 24.666 | 15.961 | 6.916 | 3.142 |

| Parameters | α1 (°) | α2 (°) | β1 (°) | β2 (°) | ws (mm) | hs (mm) | wb (mm) | hb (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before optimization | 23.772 | 23.772 | 19.142 | 19.142 | 23.335 | 7.986 | 7.206 | 14.536 |

| After optimization | 20.676 | 24.156 | 18.832 | 21.832 | 21.009 | 9.934 | 9.250 | 13.359 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).