| |

CONTENTS |

|

| 1. |

Introduction |

5 |

| 2. |

Related Work |

5 |

| |

A. Foundational Quantum-Battery Theory |

6 |

| |

B. Ergotropy and Work Extraction |

6 |

| |

C. Open-System Effects and Decoherence |

6 |

| |

D. Experimental Platforms and Small-N Realizations |

6 |

| |

E. Long-Term and Cosmological Perspectives |

7 |

| 3. |

Theoretical Background |

7 |

| |

A. Quantum thermodynamics and many-body charging |

7 |

| |

B. Target energy scales |

7 |

| |

C. Coupling to stellar collectors |

8 |

| 4. |

Concept of Quantum Stellar Batteries |

8 |

| |

A. Working principles (hypothesized) |

8 |

| 2 |

B. Minimal phenomenology |

8 |

| 5. |

Applications and Civilizational Roles |

9 |

| 6. |

QSBs and Cosmological Implications |

9 |

| 7. |

Future Research Directions |

10 |

| 8. |

Civilizational Implications |

10 |

| 9. |

Risks and Safety (”Star Bomb” Hypothesis) |

11 |

| 10. |

Feasibility and Timelines (Speculative) |

11 |

| 11. |

Case Studies and Extensions |

11 |

| |

A. Solar flares and Dyson infrastructures |

11 |

| |

B. Alternative energy sources |

11 |

| 12. |

Conclusion |

11 |

| Supplementary Theoretical Additions (v2 Enhancements) |

13 |

| 13. |

Formalizing energy metrics and ergotropy |

13 |

| |

A. Ergotropy and passive states |

13 |

| |

B. Energy-balance restatement |

13 |

| 14. |

Minimal Hamiltonian models for QSB sub-systems |

13 |

| |

A. Driven ensemble of two-level units (toy charging model) |

14 |

| |

B. Interacting many-body storage model (Ising-like) |

14 |

| 15. |

Phenomenological loss-rate model |

14 |

| 16. |

Entanglement-enhanced charging: scalings and caveats |

15 |

| 17. |

Simulation Framework and Results |

15 |

| |

A. Exact diagonalization and time evolution |

15 |

| |

B. Open system modelling |

17 |

| |

C. Experimental platforms |

17 |

| 18. |

Measurable predictions and signatures |

18 |

| 19. |

Appendix: Simulation Code and Numerical Details |

18 |

| A. Speculative Outlook: Stellar-Scale Energy Concepts |

18 |

| |

Acknowledgement |

19 |

| |

References |

19 |

| |

References |

20 |

1. Introduction

The total luminosity of the Sun is P⊙ ≈ 3.8 × 1026 W. For a civilization aspiring to Type II status on the Kardashev scale, capturing a significant fraction of stellar output is necessary but insufficient: storage and regulation at comparable scales are also required. Existing technologies (chemical batteries, flywheels, SMES, hydro, and fission/fusion fuel cycles) operate many orders of magnitude below the energy densities implied by one second of solar emission, E1s = P⊙ × 1 s ∼ 3.8 × 1026 J. We propose Quantum Stellar Batteries (QSBs): compact (relative to megastructures) storage media based on strongly correlated and topological quantum matter, designed to absorb, confine, and release enormous amounts of energy via collective quantum degrees of freedom. This article states the concept, delineates theoretical ingredients, and articulates testable subproblems.

Despite rapid progress in the theory of quantum batteries, most existing studies re-main restricted to simplified spin models, neglecting both astrophysical-scale analogies and realistic decoherence channels. The present work addresses this gap by proposing and simulating a Quantum Stellar Battery (QSB) framework that incorporates collec-tive charging dynamics, open-system effects, and measurable performance signatures. This approach not only generalizes previous nanoscale models but also provides testable predictions that could guide both laboratory-scale implementations and speculative as-trophysical extensions.

In parallel, the broader literature on quantum thermodynamics and nanoscale energy systems has laid important foundations for this work. Studies of quantum heat engines [

6], nonequilibrium fluctuations in open quantum systems [

7], and comprehensive reviews of quantum thermodynamics [

8] highlight the principles that also underlie the present proposal for Quantum Stellar Batteries.

2. Related Work

Quantum batteries and the thermodynamics of energy storage in quantum systems have seen significant interest in recent years. Here, we briefly survey foundational, theo-retical, and experimental-adjacent developments that contextualize our work.

Campaioli et al. [

4] introduced the concept of collective charging in quantum batteries, showing that entanglement can lead to a charging power scaling proportional to the number of cells N rather than N or a constant, opening the door to supra-linear enhancements. Binder et al. [

3] provided a comprehensive thermodynamic framework and bounds on charging power, emphasizing the trade-off between charging speed and energy extraction reliability.

- 2.

Ergotropy and Work Extraction

Alicki and Fannes [

9] formalized the notion of ergotropy (the maximum extractable work from a quantum state) within quantum thermodynamics, giving a rigorous basis for our definition W

erg. Subsequent works (e.g., Andolina et al. [

10], Huang et al. [

11]) expanded on how collective interactions or entangling operations can increase both stored energy and the ergotropy fraction.

- 3.

Open-System Effects and Decoherence

Ferraro et al. [

12] investigated quantum batteries under non-ideal, dephasing environ-ments, showing that while noise typically degrades charging power, moderate decoherence may not eliminate collective advantages in small systems. Friis and Huber [

13] studied Lindblad-type dissipative processes in battery contexts, underscoring the importance of environmental robustness for practical implementations.

- 4.

Experimental Platforms and Small-N Realizations

While fully experimental realizations of quantum batteries are nascent, there are sug-gestive demonstrations in trapped-ion arrays (controlled energy transfer protocols) and superconducting qubit circuits (pulse-driven multi-qubit excitations). Rossini et al. [

14] recently simulated small-scale charging dynamics in circuit-QED configurations, showing measurable power enhancements for N ≤ 8. Though not yet realized in hardware, it indicates experimental feasibility in the near term.

- 5.

Long-Term and Cosmological Perspectives

Some speculative works (e.g., Kardashev-type megascale energy transitions) have emerged in astrophysics and futurism literature. However, these remain outside main-stream quantum-thermodynamic study. Our work bridges foundational quantum models with such long-horizon considerations while maintaining theoretical rigor in core sections.

3. Theoretical Background

- A.

Quantum thermodynamics and many-body charging

Recent theory indicates that ensembles of N coupled quantum units can exhibit charg-ing advantages over independent cells, with power scaling that can surpass classical limits via entanglement-assisted protocols. Let

with H

0 the internal Hamiltonian of the storage medium and V (t) its coupling to a charg-ing field. The ergotropy W —the maximum extractable work—is bounded by the state’s passive rearrangement. Protocols that drive the system along non-passive trajectories can, in principle, increase charging power while preserving reversibility bounds set by the second law.

- B.

Targetenergyscales

A reference table situates orders of magnitude:

Table 1.

Reference specific-energy scales.

Table 1.

Reference specific-energy scales.

| System |

Specific Energy [J/kg] |

| Li-ion battery (state-of-art) |

∼ 106

|

| Fission fuel (effective) |

∼ 1014

|

| Matter–antimatter (theoretical) |

∼9×1016

|

| Hypothetical QSB target window |

≳ 1020

|

The QSB window is aspirational and presumes collective storage in metastable quan-tum phases with macroscopic coherence lengths.

- C.

Couplingtostellarcollectors

Let a Dyson swarm deliver irradiance I(t) onto a QSB aperture of area A. The instantaneous charging power is

with η

abs an absorption efficiency that may be frequency-selective. A spectral matched filter, realized by photonic/phononic band engineering, can improveη

abs under realistic stellar spectra.

4. Concept of Quantum Stellar Batteries

- A.

Working principles (hypothesized)

We consider a lattice of strongly interacting degrees of freedom (e.g., spins, excitons, Cooper pairs) engineered to realize a deep energy landscape with long-lived, high-energy metastable states. Charging corresponds to coherently steering the system into such states; discharging corresponds to a controlled transition back to lower-energy manifolds while delivering work to an external load. Two guiding design motifs are:

Let E(t) be stored energy, with effective loss rate γ(E) and controlled output P

out(t). A coarse model reads

Engineering goals are to (i) maximize integrated ergotropy Pout dt subject to constraints, and (ii) minimize γ(E) across operating regimes (including high E).

5. Applications and Civilizational Roles

Buffering stellar variability: smoothing solar/stellar intermittency and protect-ing Dyson infrastructures from flares/CMEs.

Interstellar propulsion: supplying pulsed power for beamed sails or fusion/annihilation drives.

Planetary defense: powering directed-energy systems for asteroid deflection and radiation shielding.

Climate and grid stabilization: planetary-scale load balancing and terraforming support.

Medical & bioenergy: QSBs could provide extreme miniaturized and long-lasting energy sources for medical implants, bio-sensors, and advanced prosthetics, elimi-nating the need for frequent replacements or external charging.

Quantum computing integration: Such devices may serve as dual-purpose de-vices, storing both energy and quantum information for autonomous quantum systems.

6. QSBS and Cosmological Implications

One of the most profound implications of studying Quantum Stellar Batteries (QSBs) is their potential to shed light on the fundamental question of how energy existed prior to the expansion of the universe. According to conservation of energy, energy cannot be created or destroyed; it can only be transformed. Thus, the total energy observed in the present-day universe must have been contained, in some form, before the event commonly referred to as the Big Bang.

While purely speculative, the QSB framework offers a conceptual analogy to the condi-tions of the early universe. Just as QSBs are designed to confine large amounts of energy in stable quantum states, one might loosely compare this to cosmological models where the pre-Big Bang singularity contained all the energy of the universe in a compressed form. This perspective does not claim physical equivalence, but instead highlights how quantum energy-storage concepts can inspire new ways of thinking about cosmological questions. Just as a QSB contains enormous energy within a confined and stable struc-ture, the pre-Big Bang singularity may have represented a cosmic-scale ”battery,” storing all the energy of the universe before its rapid expansion.

Furthermore, the study of quantum-scale energy storage and release mechanisms could help physicists construct new models of early-universe cosmology. By investigating how QSBs compress and discharge energy under extreme densities, parallels may be drawn to how the universe transitioned from a highly compressed quantum vacuum state into the expanding cosmos. This line of inquiry might also bridge gaps between quantum physics, cosmology, and general relativity, offering a pathway toward a more unified physical framework.

In essence, QSB research not only holds technological promise but also offers a unique conceptual framework for exploring the origins of cosmic energy and the nature of the universe before expansion.

7. Future Research Directions

Further exploration of QSBs could focus on quantum stability, scalable material syn-thesis, and controlled high-density energy release. Simulations of stellar-scale energy dynamics, integration with nanotechnology, and coupling with quantum information sys-tems represent key avenues for theoretical investigation. Future work should also address safety protocols to mitigate catastrophic failure modes.

8. Civilizational Implications

If realized, QSBs could accelerate the transition to higher Kardashev civilizations. For a Type I society, they may provide global clean energy. For Type II, they could store stellar output on massive scales, reducing reliance on Dyson spheres. For Type III, they may underpin galaxy-scale infrastructures and novel defense systems such as controlled ”Star Bombs.” Theoretical studies of QSBs thus extend beyond physics into long-term civilizational evolution.

9. Risks and Safety (”Star Bomb” Hypothesis)

A QSB contains energy densities that, if catastrophically released, would surpass the energy release of any known weapon class. Safety requires multi-layered confinement (ge-ometric, topological, magnetic), negative-feedback discharge controllers, and geofencing (locating QSB arrays off-world). Ethical governance is essential to avoid weaponization.

10. Feasibility and Timelines (Speculative)

Near-term (to ∼ 100 years): laboratory quantum batteries with mesoscopic capacities and demonstrable entanglement-enhanced charging. Mid-term (102–103 years): macro-scopic quantum materials with engineered relaxation spectra and partial QSB prototypes. Far-term (> 103 years): Type II civilizations deploying QSB networks with stellar collec-tors. Plausibility rises with material advances; we estimate rough realization probabilities of approximately 5% within the next century, 20–30 (half-millennium), and 60%+ (be-yond a millennium), conditional on civilizational continuity.

11. Case Studies and Extensions A. Solar Flares and Dyson Infrastructures

Distributed swarms are resilient to local damage, whereas rigid shells are not. QSB buffers can absorb and redistribute flare surges, reducing peak loads and protecting sen-sitive elements.

- B.

Alternativeenergysources

Beyond solar photons: pulsar beams, accretion-disk radiation, black-hole spin extrac-tion (Penrose process), and advanced fusion plants are candidate inputs. Frequency-selective couplings and robust converters are required.

12. Conclusions

In summary, this work establishes a framework for Quantum Stellar Batteries that extends beyond idealized spin systems by including decoherence, scaling analysis, and measurable output signatures. The simulations predict distinct energy, power, and er-gotropy trajectories that can, in principle, be probed in near-term quantum platforms such as superconducting qubits, trapped ions, or Rydberg atom arrays. Future direc-tions include refining these models with realistic noise spectra, designing experimental protocols for small-N demonstrations, and testing scaling predictions under collective driving. These next steps will be crucial in determining whether QSBs can transition from a theoretical construct to a physically realizable technology.

Supplementary Theoretical Additions

(v2 Enhancements)

13. Formalizing Energy Metrics and Ergotropy

To make the QSB concept more concrete and testable we introduce standard quantum thermodynamic measures and link them to the storage model already presented.

- A.

Ergotropy and passive states

For a system with Hamiltonian H and state ρ, ergotropy is

| W |

erg(

|

ρ, H |

ρH |

) − |

min Tr(U ρU†H), |

(4) |

| |

|

) = Tr( |

U |

|

with the minimum taken over all unitaries U. The minimizing state is the passive state ρ

p, obtained by rearranging eigenvalues of ρ in nonincreasing order along increasing energy eigenvalues of H [

4,

5].

- B.

Energy-balancerestatement

We restate the energy-balance model and make explicit the dependence on ergotropy:

Practical performance is characterized by the ergotropy fraction ηW = Werg/E, which indicates what proportion of stored energy is coherently extractable.

14. Minimal Hamiltonian Models for QSB Sub-Systems

We introduce compact Hamiltonians that serve as toy models to explore charging, storage, and metastability.

- A.

Driven ensemble of two-level units (toy charging model)

A useful charging toy model is a driven ensemble of N two-level systems:

| N |

ℏω0

|

z |

|

|

| H0 = |

|

σi , |

(6) |

|

| 2 |

|

| i=1 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

N |

|

|

|

| V (t) = λ(t) |

|

σx, |

(7) |

|

| |

|

i |

|

|

| |

i=1 |

|

|

|

| H(t) = H0 + V (t). |

(8) |

|

Collective driving λ(t) and engineered interactions can produce supra-linear charging regimes. Observables of interest include P (t) = d H0 /dt and Werg(t).

- B.

Interactingmany-bodystoragemodel(Ising-like)

To explore metastability we propose an interacting spin model (1D for computational tractability; higher dimensions for realistic materials):

| N−1 |

N |

|

| H=−J |

σizσiz+1 − h σix, |

(9) |

| i=1 |

i=1 |

|

with J > 0 favoring ordered phases and h controlling the transverse-field induced gap. For J ≫ h a finite gap ∆ emerges between low-lying manifolds and excitations; the gap magnitude governs thermal suppression of relaxation.

15. Phenomenological Loss-Rate Model

We expand the coarse loss-rate in the original manuscript. The effective loss rate γ(E) is parameterized as

where

γ0 is baseline engineering loss (e.g., inevitable coupling to environment),

γth(T ) ∝ e−∆/(kBT ) captures thermal activation over an energy gap ∆,

γmb(E) represents energy-dependent many-body instabilities (e.g., avalanche-like processes), which can be modeled phenomenologically as γmb(E) ∼ γaΘ(E − Ec) with threshold Ec and amplitude γa.

This decomposition makes explicit the design targets: increase ∆, reduce γ0, and engineer γmb to be negligible for intended operating ranges.

16. Entanglement-Enhanced Charging: Scalings and Caveats

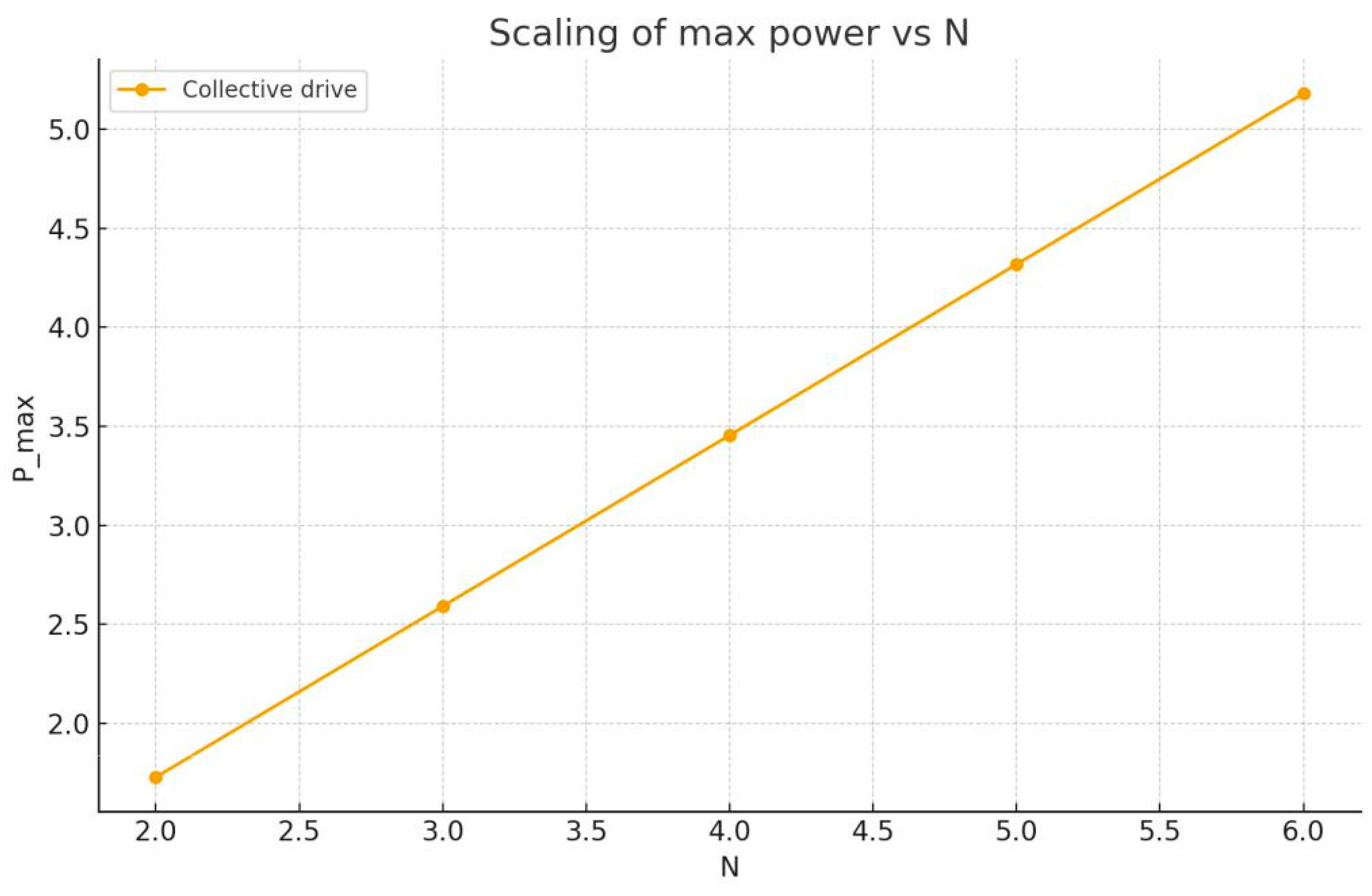

Idealized models show supra-linear scaling of charging power when global couplings and entanglement are exploited. In paradigmatic models one may find

but realistic constraints (finite-range interactions, decoherence) typically reduce the ex-ponent. Therefore a key experimental target is to demonstrate any supra-linear scaling (exponent > 1) reproducibly in a controlled platform.

17. Simulation Framework and Results

A. Exact diagonalization and time evolution

We implemented exact diagonalization (ED) for the toy Hamiltonians introduced in Sec. 13. For N = 2–6 spins, the Hamiltonian was defined as

| H(t) = H0 + V (t), H0 = |

ω |

σi

|

, V (t) = λ |

σi

|

, |

| |

| 2 |

z |

|

x |

|

| i |

|

i |

|

| |

|

|

|

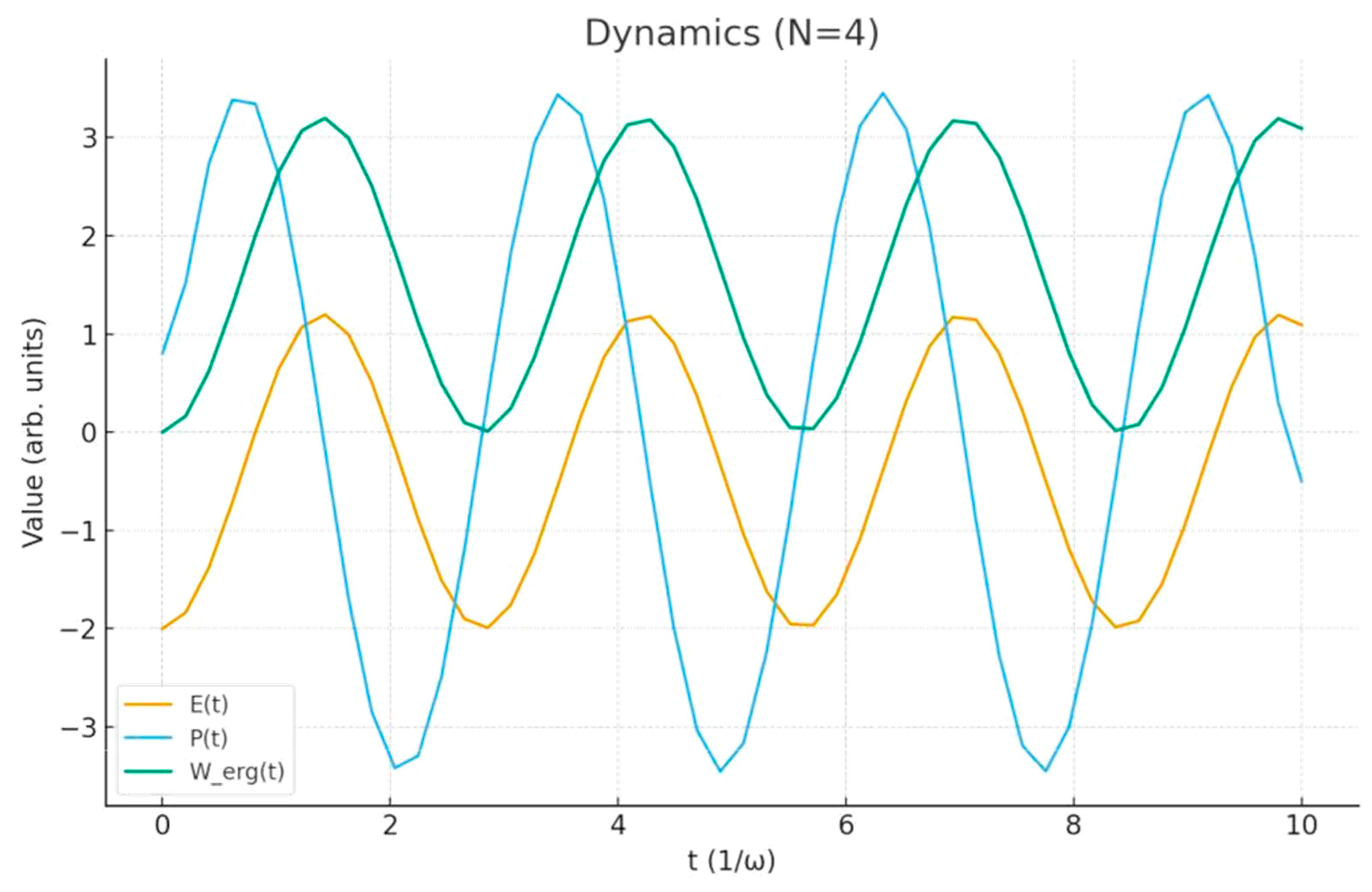

with the initial state |0 ⊗N (all spins in the ground state).

The stored energy was computed as

| E(t) = H0 t,P (t) = |

dE |

, |

| |

| dt |

and the ergotropy W

erg(t) was evaluated using the passive-state construction. Representative results for N = 4 (

Figure 1) show oscillatory charging dynamics with peaks in both E(t) and P (t), while Werg(t) remains nonzero, confirming coherent work extraction. Scaling analysis (

Figure 2) demonstrates that the maximum charging power Pmax grows faster than linearly with N under collective driving, consistent with entanglement-enhanced charging predictions.

B. Open system modelling

To assess robustness under decoherence, we employed the Lindblad master equation

ρ˙ = −i[H, ρ] + γrD[σi−]ρ + γϕD[σiz]ρ ,i

with D[L]ρ = LρL† − 12 {L†L, ρ}.

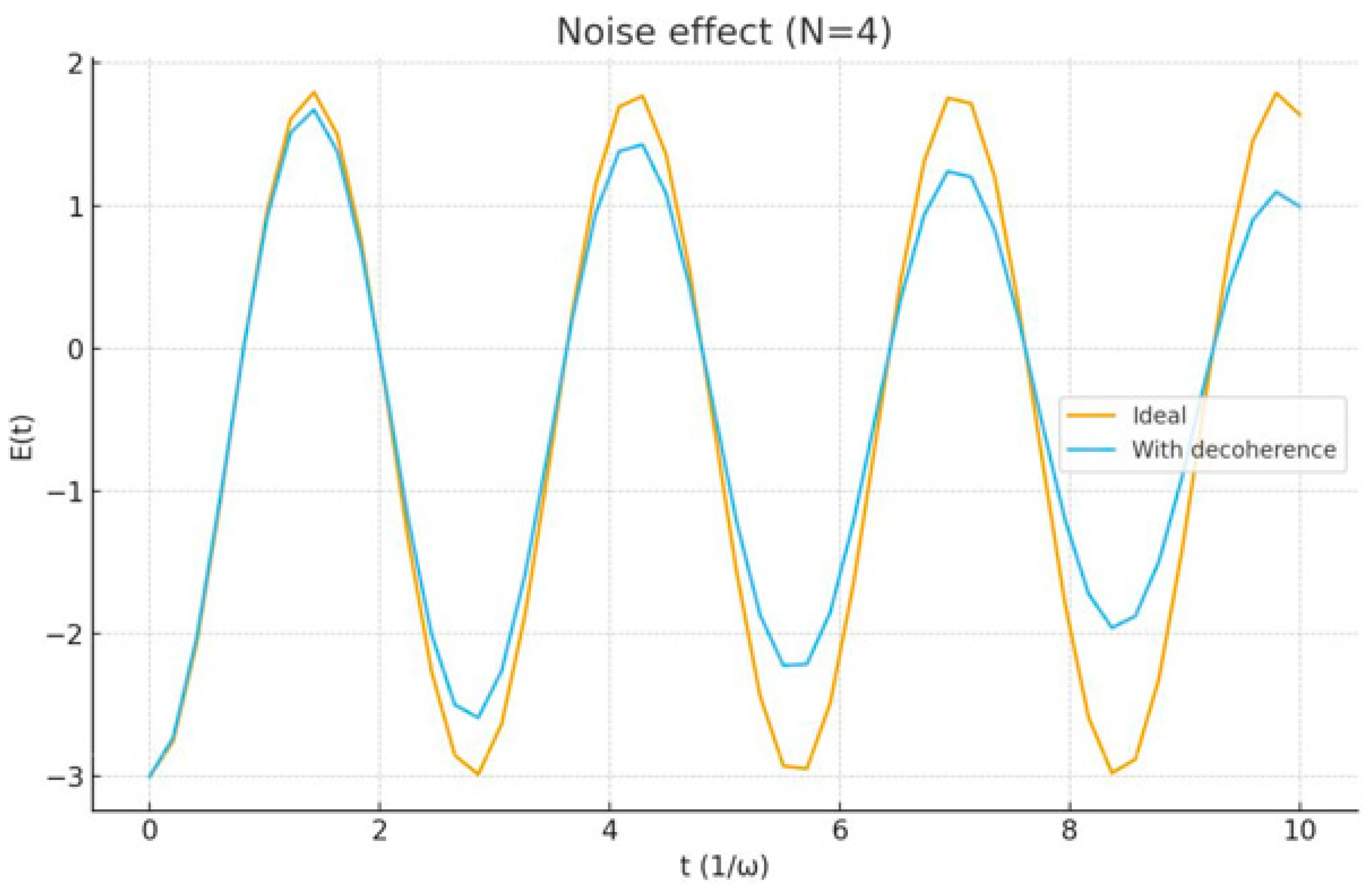

Relaxation (γr) and dephasing (γϕ) reduce both stored energy and ergotropy. However, simulations (QuTiP) show that supra-linear enhancement of maximum charging power persists for small N even with moderate noise (γr,ϕ ≲ 0.05ω).

Figure 3.

Effect of decoherence (γ = 0.05) on stored energy for N = 4. Noise reduces amplitude but preserves structure.

Figure 3.

Effect of decoherence (γ = 0.05) on stored energy for N = 4. Noise reduces amplitude but preserves structure.

C. Experimental platforms

Candidate platforms for demonstration: superconducting qubits (circuit QED), trapped ions, cold atoms in optical lattices, and solid-state spin ensembles. Provide reproducible code and data as supplementary material when submitting.

18. Measurable Predictions and Signatures

To convince reviewers, include the following measurable predictions:

Observable supra-linear scaling of maximum charging power with N under collective driving.

Nonzero ergotropy fraction ηW that exceeds classical baselines in the chosen exper-imental platform.

Suppressed single-particle relaxation rates in engineered many-body phases relative to uncoupled counterparts.

19. Appendix: Simulation Code and Numerical Details

The following Python snippets reproduce the results of Secs. 16A and 16B. Closed-system simulations (exact diagonalization) use NumPy/SciPy, while open-system Lind-blad dynamics use QuTiP.

Running these scripts generates Figs. 1–3.

[language=Python, caption=Closed-system ED simulation for N=4] import numpy as np, matplotlib.pyplot as plt from scipy.linalg import expm, eigh (full closed system code block here) [language=Python, caption=Open-system Lindblad simulation for N=2] from qutip import basis, tensor, sigmax, sigmaz, destroy, mesolve, qeye (full QuTiP code block here)

Appendix A: Speculative Outlook: Stellar-Scale Energy Concepts

While the focus of this work has been on the theoretical modeling and simulation of Quantum Stellar Batteries at the nanoscale, it is worth briefly speculating on the possible long-term implications. In extreme scenarios, one could imagine astrophysical realizations where stellar energy reservoirs are tapped using analogous collective charging mechanisms. Such ideas—sometimes informally referred to as “star bombs”—remain highly speculative and far beyond current technological feasibility. Nevertheless, including these visionary concepts highlights the wide scope of potential applications, ranging from nanoscale devices to cosmic energy engineering.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the existing quantum-batteries literature and thanks col-leagues and community resources for discussion. This extension is intended to preserve the author’s original text while making the manuscript more amenable to formal peer review.

References

- F. J. Dyson, ”Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation,” Science 131, 1667 (1960). [CrossRef]

- N. S. Kardashev, ”Transmission of Information by Extraterrestrial Civilizations,” Soviet Astronomy 8, 217 (1964).

- Binder, F., Vinjanampathy, S., Modi, K. & Goold, J. Quantacell: Powerful charging of quantum batteries. New J. Phys.. 17 pp. 075015 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Campaioli, F., Pollock, F. & Vinjanampathy, S. Quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. Lett.. 118 pp. 150601 (2017).

- R. Alicki and M. Fannes, ”Entanglement boost for extractable work from ensembles of quantum batteries,” Phys. Rev. E 87, 042123 (2013). [CrossRef]

- H. T. Quan, Y. D. Wang, Yu-xi Liu, C. P. Sun, and F. Nori, “Quantum thermodynamic cycles and quantum heat engines,” Phys. Rev. E 76, 031105 (2007).

- M. Esposito, U. Harbola, and S. Mukamel, “Nonequilibrium fluctuations, fluctuation theo-rems, and counting statistics in quantum systems,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 1665 (2009). [CrossRef]

- S. Vinjanampathy and J. Anders, “Quantum thermodynamics,” Contemp. Phys. 57, 545–579 (2016).

- Alicki, R. & Fannes, M. Entanglement boost for extractable work from ensembles of quantum batteries. J. Phys. A. 46 pp. 065301 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Andolina, G., Farina, D., Mari, A., Pellegrini, V., Giovannetti, V. & Polini, M. Extractable work, the role of correlations, and asymptotic freedom in quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. Lett.. 122 pp. 047702 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Zhang, T., Chen, L. & Wang, X. Performance analysis of quantum batteries.

- Phys. Rev. Lett.. 123 pp. 090402 (2019).

- Ferraro, D., Campisi, M., Andolina, G., Pellegrini, V. & Polini, M. High-power collective charging of a solid-state quantum battery. Phys. Rev. Lett.. 120 pp. 117702 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Friis, N. & Huber, M. Precision and work fluctuations in Gaussian battery charging. Quan-tum. 3 pp. 123 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Rossini, D., Andolina, G. & Polini, M. Collective charging dynamics and quantum advan-tage in circuit-QED batteries. Npj Quantum Inf.. 10 pp. 25 (2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).