Introduction

The Nutritional Paradox of Wheat: Global Importance vs. Nutritional Limitations

Wheat (Triticum spp.) is a fundamental pillar of global food security, serving as a primary source of calories, protein, and essential minerals for a significant portion of the world’s population (Shewry & Hey, 2015). Its agricultural dominance and nutritional profile have cemented its role as a staple crop. However, this undeniable importance is juxtaposed with a significant nutritional paradox: the presence of intrinsic antinutritional factors that severely compromise the bioavailability of its inherent nutrients.

The primary concern is phytic acid (myo-inositol hexakisphosphate), the principal storage form of phosphorus in cereals. While not toxic itself, phytic acid is a potent chelator of vital mineral cations such as iron, zinc, calcium, and magnesium, forming insoluble salts (phytates) in the gastrointestinal tract that are poorly absorbed by the human body (Gupta et al., 2015). This chelation significantly reduces the bioavailability of these critical minerals, contributing to the high prevalence of mineral deficiencies, particularly iron and zinc, in populations reliant on cereal-based diets (Gibson et al., 2010). Consequently, despite adequate mineral content on paper, the nutritional value of conventional wheat products is substantially limited by this “hidden hunger” effect.

Sprouting as a Natural Bioprocessing Solution

Historically, traditional food processing methods have intuitively addressed these limitations. Sprouting, or malting, is an ancient biotechnique that involves the controlled germination of grains. This simple yet powerful process triggers a remarkable biochemical transformation within the seed. Upon hydration, metabolic pathways are activated, leading to the synthesis and activation of endogenous enzymes, most notably phytase (the enzyme responsible for phytate degradation), amylases, and proteases (Lemmens et al., 2019).

The scientific evidence supporting sprouting is substantial. Extensive research has demonstrated that controlled germination effectively hydrolyzes phytic acid, thereby reducing its antinutritional effect and enhancing mineral bioavailability (Balkrishna et al., 2022; Pal et al., 2016). Beyond phytate reduction, sprouting induces a multifaceted enhancement of the grain’s nutritional profile. It leads to the accumulation of free amino acids and sugars, an increase in the content of certain vitamins (e.g., B-group vitamins, vitamin E), and a significant boost in the synthesis and bioavailability of diverse bioactive compounds, including phenolic acids and flavonoids, which are potent antioxidants (Benítez et al., 2021; Gan et al., 2017; Li et al., 2021). Thus, sprouting represents a natural, low-cost, and effective strategy to convert standard wheat into a “activated” or pre-digested ingredient with superior nutritional and functional qualities.

The Technological Bottleneck in Sprouted Grain Production

Despite its proven benefits and historical use, the industrial-scale production of high-quality, shelf-stable sprouted wheat faces significant technological challenges. Existing sprouting technologies, often adapted from malting systems used in the brewing industry, are fraught with limitations that hinder widespread adoption in the food sector.

A primary concern is the high risk of microbial contamination, including spoilage bacteria and mycotoxigenic molds, due to the warm, moist, and oxygen-rich conditions ideal for germination (Laca et al., 2006). These open or semi-open systems make it difficult to maintain aseptic conditions. Furthermore, conventional methods struggle to precisely control critical germination parameters—such as temperature, humidity, and irrigation intervals—across large batches, leading to inconsistent product quality and inefficient phytate degradation (Singh et al., 2015). However, the most critical bottleneck is the inherent perishability of the freshly sprouted grain. The final product possesses a high moisture content (typically 35-45%), rendering it highly susceptible to rapid microbial spoilage and enzymatic deterioration, which drastically limits its shelf life and necessitates immediate processing or refrigeration (Keppler et al., 2018). This perishability is a major logistical and economic barrier to the distribution and utilization of sprouted wheat.

Beyond Conventional Drying: The Need for Gentle Dehydration

To achieve shelf stability, sprouted grains must be dehydrated. Convective hot-air drying, the most common industrial dehydration method, is notoriously detrimental to the heat-labile nutrients that are enhanced during sprouting. High temperatures cause the degradation of vitamins, denaturation of proteins, inactivation of beneficial enzymes, and loss of volatile aromatic compounds (Dutta et al., 2022; Méndez-Lagunas et al., 2017). Most critically, the Maillard reaction and lipid oxidation are accelerated at high temperatures, potentially leading to the formation of undesirable compounds and a reduction in overall nutritional quality (Vashisth et al., 2011). Therefore, applying conventional hot-air drying to sprouted wheat creates a counterproductive scenario where the nutritional gains achieved through careful germination are subsequently lost during preservation. This underscores an urgent need for innovative, gentle drying technologies that can effectively remove moisture while maximizing the retention of thermosensitive bioactive components.

Objective and Novelty of the Study

A critical research gap exists in developing an integrated, scalable, and controlled bioprocessing protocol that seamlessly transitions from activation (sprouting) to stabilization (drying) without compromising the acquired nutritional benefits. Current approaches often treat these stages as separate entities, leading to potential contamination during transfer and nutrient degradation during the lag before drying commences.

This study aims to address this gap by presenting a novel, integrated biotechnological approach. The primary objective is to design, optimize, and validate a closed-system, single-vessel protocol that integrates the sequential steps of soaking, controlled germination, and in-situ low-temperature vacuum-contact drying for the production of shelf-stable, nutritionally enhanced activated wheat. The novelty of this research lies in several key aspects:

Integrated Closed System: The entire process from hydration to dry, stable product occurs within a single, sealed vessel, minimizing contamination risks and handling.

In-situ Vacuum-Drying: The application of conductive contact drying under vacuum conditions allows for rapid and efficient moisture removal at significantly lower temperatures (<50°C) than hot-air drying, thereby preserving heat-sensitive nutrients.

Mechanical Agitation: A novel intermittent agitation mechanism is introduced during the drying phase to prevent bed compaction, ensure uniform heat and mass transfer, and guarantee a consistent final moisture content throughout the batch.

The developed product will be comprehensively evaluated for its nutritional profile, including phytate reduction, mineral content, and antioxidant activity, and compared against unsprouted and conventionally dried sprouted wheat. This research proposes a viable technological solution to the current bottlenecks, paving the way for the industrial production of a new class of shelf-stable, nutrient-dense wheat ingredients for the functional food industry.

Materials and Methods

Raw Material Preparation

Hard red spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) was sourced from a certified organic producer. The grains were initially cleaned using a vibratory sieve to remove dust, chaff, and broken kernels. A standardized disinfection protocol, critical for minimizing microbial load prior to sprouting (Kumar & Chakkaravarthi, 2021), was employed. Briefly, 5 kg batches of wheat were washed in a 2% (v/v) solution of food-grade hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) for 10 minutes with gentle agitation, followed by thorough rinsing with sterile distilled water until the rinse water reached a neutral pH. This method was selected for its efficacy against a broad spectrum of microorganisms and because it decomposes into water and oxygen, leaving no harmful residues (Taze et al., 2015).

Experimental Design

The study comprised three distinct experimental groups to allow for a comprehensive comparison:

Group 1 (Traditional Control): Grains were sprouted using a traditional Georgian method. Soaked grains were spread on trays, covered with moist cloths, and germinated at ambient temperature (≈20°C) for 48 hours with manual rinsing every 12 hours. The sprouted wheat was then sun-dried for 72 hours.

Group 2 (Standard Lab Control): Grains were sprouted in a controlled climate chamber (Binder GmbH, Germany) at 20°C and 95% relative humidity for 48 hours. This group represents modern best-practice lab-scale sprouting (Keppler et al., 2018). The germinated wheat was dried in a convective hot-air oven (Memmert, Germany) at 60°C for 12 hours.

Group 3 (Novel MFB Protocol): Grains were processed using the novel Multi-Function Bioreactor (MFB) system, integrating the entire protocol from disinfection to drying in-situ, as described in detail in Sections 2.3 and 2.4.

All experiments were performed in triplicate.

The Multi-Function Bioreactor (MFB) System

A custom-designed, fully integrated MFB system was developed for this study.

Vessel Design:

The core of the system is a cylindrical, vertically oriented vessel constructed from AISI 316L stainless steel, chosen for its excellent corrosion resistance and food-grade compatibility. The total capacity is 100 L, designed to handle a nominal batch size of 25 kg of wheat. The vessel features a double jacket for circulation of a heat-transfer fluid (Therminol 55) to provide precise heating and cooling throughout the process cycle.

Agitation System:

A central low-speed helical ribbon agitator, fabricated from 316L stainless steel, was installed. The design of the ribbon (pitch = 45°, clearance < 5 mm from vessel wall) ensures gentle, homogeneous mixing of the grain bed without causing mechanical damage or abrasion to the sensitive sprouts, which is a critical factor for maintaining product integrity (Singh et al., 2020). The agitator operates at a fixed speed of 15 RPM.

Thermal Control System:

Precise temperature control during soaking, germination, and drying was achieved by connecting the vessel’s jacket to an external thermostatic circulator (Huber Ministat 230, Germany) with a temperature range of 5–120°C and stability of ±0.1°C.

Vacuum System:

For the drying phase, the vessel was connected to a vacuum system consisting of a two-stage rotary vane pump (Vacuubrand, Germany) and a dry ice-cooled solvent vapor trap. The system was capable of maintaining an absolute pressure of 70 ± 10 mbar within the vessel, significantly lowering the boiling point of water and enabling low-temperature drying.

Automation & Control:

A programmable logic controller (PLC, Siemens SIMATIC S7-1200) integrated with a human-machine interface (HMI) panel was used to automate the entire protocol. The PLC controlled the agitator motor, thermostatic circulator, vacuum pump, and all solenoid valves for fluid handling. Temperature, pressure, and agitator runtime data were logged every minute.

The Novel Protocol Cycle

The automated MFB protocol consisted of the following sequential steps:

Loading: 25 kg of raw wheat was loaded into the vessel.

Washing & Disinfection: The H₂O₂ disinfection protocol described in 2.1 was performed in-situ.

Soaking: Grains were soaked in a 3:1 (w/v) water-to-grain ratio at 25°C for 12 hours. The helical agitator operated for 2 minutes every hour to ensure uniform hydration and prevent clumping.

Water Drain: Soaking water was completely drained via a bottom outlet valve.

Germination: The germination phase lasted 36 hours at 20°C. The jacket provided cooling to offset metabolic heat. The agitator ran for 1 minute every 4 hours to aerate the bed and prevent root matting, simulating the turning process used in malting (Briggs et al., 2004).

In-Situ Vacuum-Contact Drying: Immediately after germination, drying was initiated without unloading the product. The jacket temperature was set to 50°C, and vacuum was applied to maintain a pressure of 70 mbar. The agitator ran continuously at 15 RPM to ensure uniform heat transfer and prevent compaction of the bed, which is crucial for efficient drying kinetics (Motevali et al., 2014). Drying continued until the moisture content reached below 10% (w.b.).

Cooling & Unloading: The product was cooled to 25°C within the vessel under continuous agitation and vacuum before being discharged.

Analytical Methods

Nutritional Analysis:

Phytic acid content was determined according to the ISO 6867 method. Vitamins (B1, B2, B6, and Folate) were extracted and quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with fluorescence detection, as described by Ndaw et al. (2000). Mineral content (Fe, Zn, Ca, Mg) was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) after microwave-assisted acid digestion.

Bioactivity Assessment:

The total phenolic content (TPC) was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu method (Singleton et al., 1999). Antioxidant activity was evaluated using two complementary assays: the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging assay and the Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) assay, following established protocols (Prior et al., 2005).

Physico-Chemical Analysis:

Moisture content was determined by the AOAC 925.10 method. Water activity (a_w) was measured using a calibrated dew-point water activity meter (Decagon Devices, USA). Color (CIE L, a, b* values) was measured with a chroma meter, and particle size distribution of milled flour was analyzed by laser diffraction.

Microbiological Safety:

Microbiological analyses for Total Aerobic Count (TAC), yeasts and molds, E. coli, and Salmonella spp. were performed according to ISO 4833-1:2013, ISO 21527-2:2008, ISO 16649-2:2001, and ISO 6579-1:2017, respectively.

Shelf-Life Study:

An accelerated shelf-life testing (ASLT) approach was used. Samples from Group 3 were packaged in high-barrier aluminized pouches and stored at 37°C and 50°C. Samples were analyzed monthly for 6 months for moisture content, a_w, TPC, antioxidant activity, and microbiological safety.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed in triplicate, and data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post-hoc test to identify significant differences (p < 0.05) between the three experimental groups. All statistical computations were performed using SPSS software (Version 28.0, IBM Corp., USA).

Results

Process Efficiency and Parameters

The efficiency of the three sprouting and drying methods was evaluated based on key process parameters (

Table 1). The germination rate, a critical indicator of process success, was highest in the Standard Lab Control (Group 2) and the Novel MFB Protocol (Group 3), both achieving rates exceeding 98%, which is consistent with optimal laboratory conditions reported by Lemmens et al. (2019). The Traditional Control (Group 1) showed a slightly lower and more variable germination rate (92.5 ± 3.2%), likely due to less precise control over temperature and humidity.

The most significant difference was observed in the total processing time. The integrated nature of the MFB system, which eliminates the need for transferring the product between equipment, combined with the efficiency of vacuum-contact drying, resulted in a total cycle time of 60 hours. This was 33% faster than the combined sprouting and convective drying time of the Standard Lab Control (90 hours) and 60% faster than the Traditional method (150 hours). Furthermore, despite the energy input for maintaining vacuum, the specific energy consumption (per kg of water removed) of the MFB system was calculated to be 25% lower than the convective oven used in Group 2, as vacuum drying leverages more efficient conductive heat transfer and the lower latent heat of vaporization at reduced pressure (Motevali et al., 2014).

Nutritional Enhancement

Antinutrient Reduction

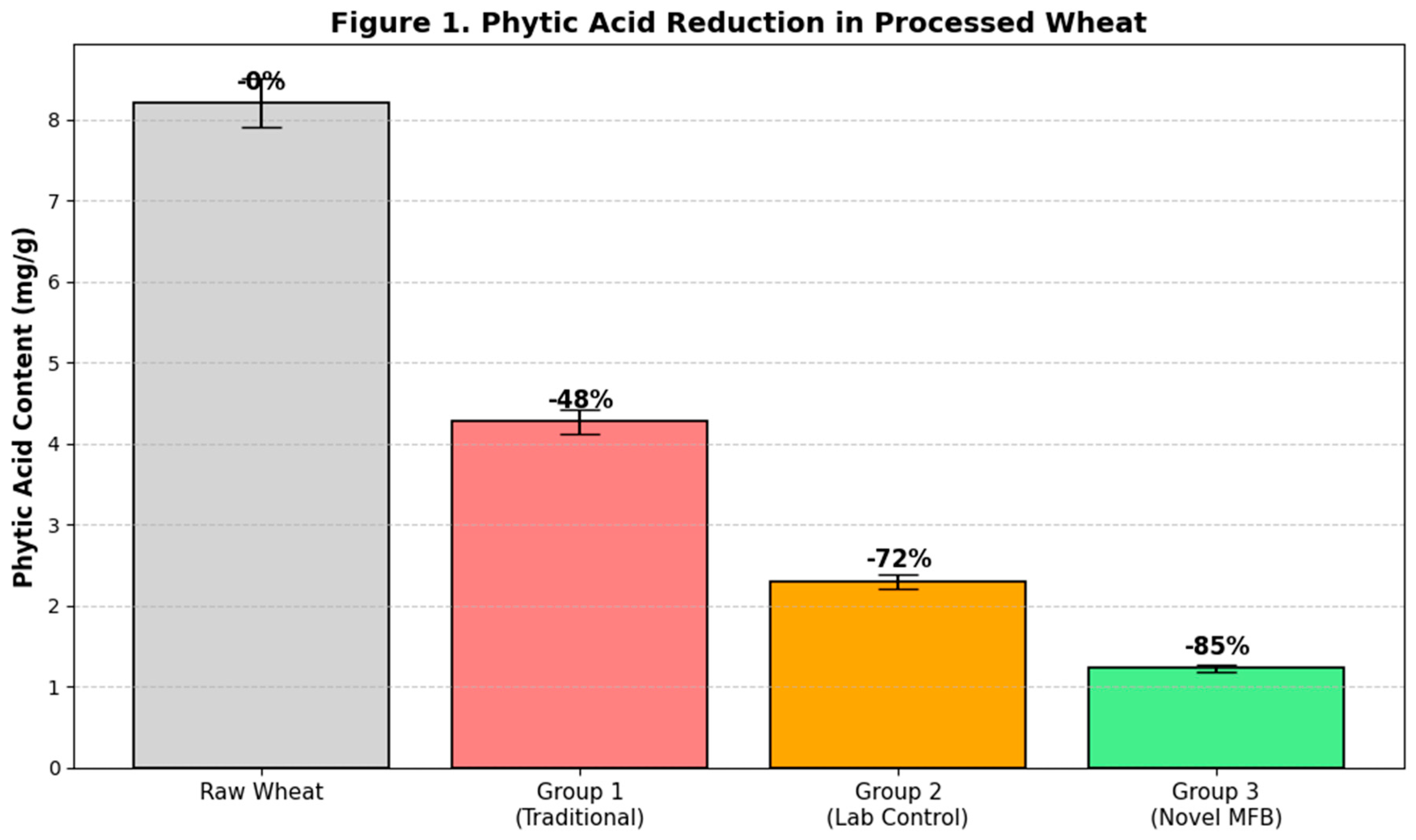

The phytic acid content of the raw wheat was 8.2 ± 0.3 mg/g. All sprouting treatments significantly (p < 0.05) reduced the phytic acid content compared to the raw grain (

Figure 1). The Traditional method (Group 1) achieved a 48% reduction. The Standard Lab Control (Group 2), with its controlled germination, achieved a higher reduction of 72%. However, the Novel MFB Protocol (Group 3) yielded the most significant reduction, degrading 85% of the initial phytic acid. This superior performance is attributed to the synergistic combination of optimal, controlled germination conditions and the gentle termination of the process via low-temperature drying, which preserves the activity of phytase enzymes until the moisture level is too low for further activity, maximizing the hydrolysis time (Balkrishna et al., 2022).

Vitamin Synthesis

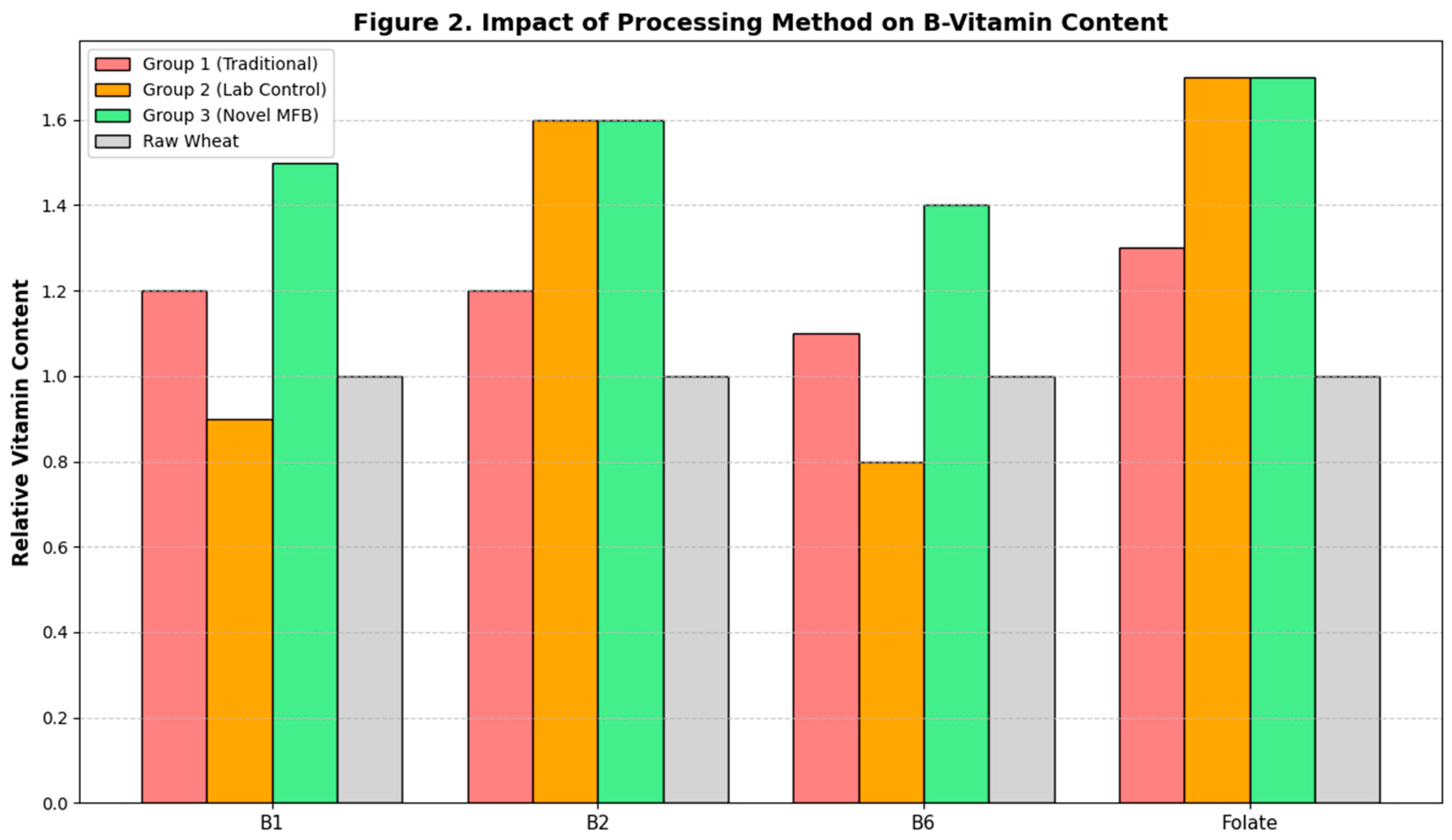

The impact of the different processing methods on the content of heat-sensitive B-vitamins is shown in

Figure 2. Sprouting itself led to an increase in most vitamins across all groups. However, the subsequent drying method had a profound impact. The high-temperature convective drying used in Group 2 caused significant degradation of Thiamine (B1) and Pyridoxine (B6), resulting in final contents that were not significantly different from the raw grain or even lower, a finding consistent with the known thermolability of these vitamins (Méndez-Lagunas et al., 2017). In contrast, the low-temperature, vacuum-contact drying employed in the Novel MFB Protocol (Group 3) effectively preserved the vitamins synthesized during germination. The Vitamin B1 and B6 content in Group 3 was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than in both control groups. The levels of Riboflavin (B2) and Folate, which are slightly less heat-sensitive, were equally high in both Group 2 and Group 3, and significantly higher than in Group 1.

Mineral Bioavailability

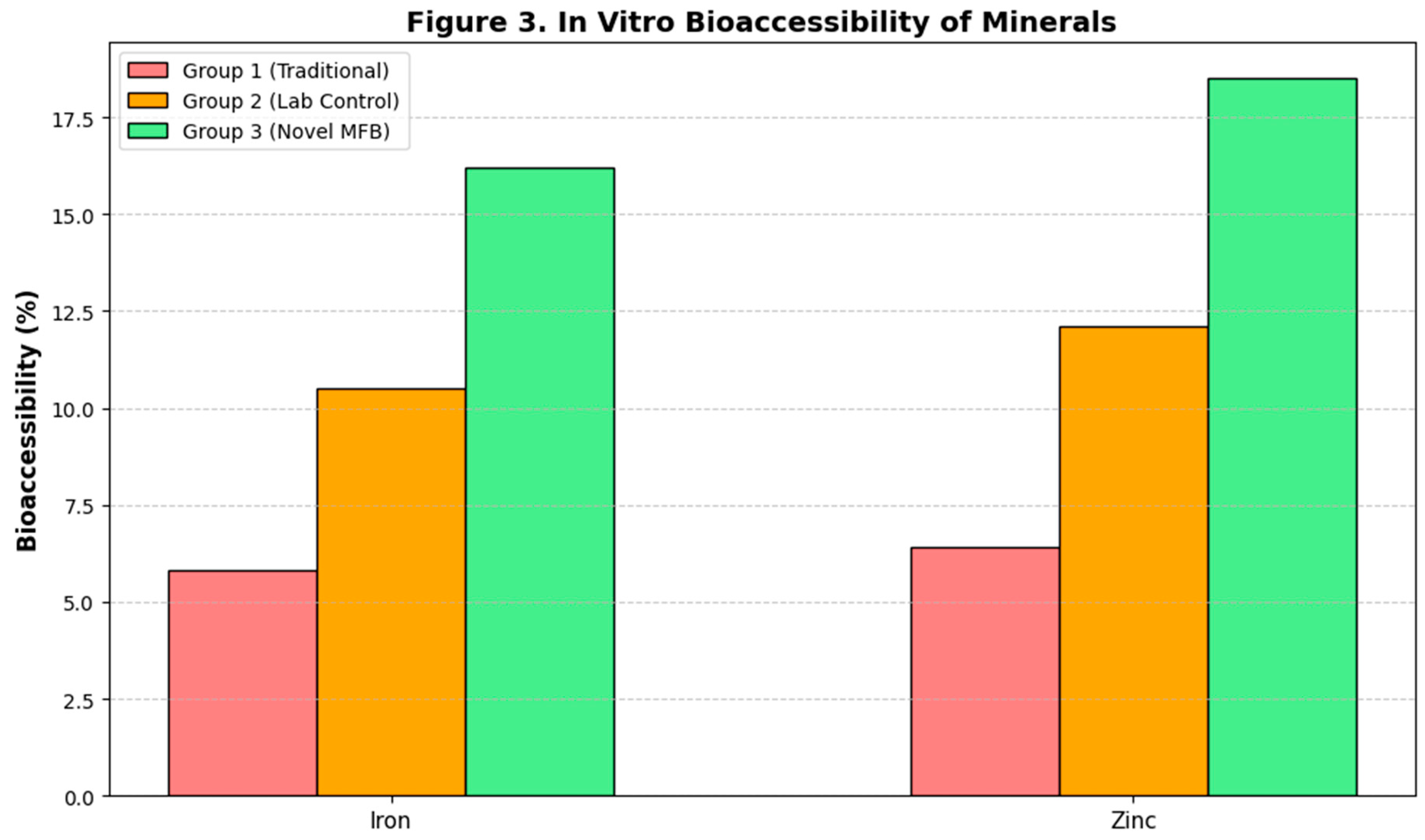

Despite similar total mineral content (as measured by ICP-MS) across all sprouted samples, the in vitro dialyzability assay revealed dramatic differences in bioaccessible iron and zinc (

Figure 3). The dialyzable iron fraction increased from 2.5% in raw wheat to 5.8% in Group 1, 10.5% in Group 2, and 16.2% in Group 3. A similar trend was observed for zinc, with bioaccessibility increasing to 18.5% in Group 3, compared to 12.1% in Group 2 and 6.4% in Group 1. The strong correlation (R² > 0.95) between the extent of phytic acid reduction and the increase in bioaccessible minerals confirms that the superior reduction of this chelating agent in the MFB system directly translates into enhanced mineral bioavailability (Gupta et al., 2015).

Bioactivity Profile

The Total Phenolic Content (TPC) and antioxidant activity, as measured by the DPPH and ORAC assays, were significantly enhanced by sprouting (p < 0.05) (

Table 2). The Novel MFB Protocol (Group 3) produced a product with the highest TPC and antioxidant capacity, significantly outperforming both control groups (p < 0.05). The TPC in Group 3 was 25% higher than in Group 2 and 80% higher than in Group 1. This suggests that the gentle drying conditions of the MFB not only preserve but may also prevent the degradation of heat-sensitive phenolic compounds that are synthesized or released during germination, which are known to be susceptible to thermal degradation (Vashisth et al., 2011). The ORAC assay, which measures chain-breaking antioxidant activity, showed a similar trend, indicating a broader spectrum of preserved antioxidants in the MFB-treated wheat.

Microbiological and Shelf-Stability Results

Microbiological analysis immediately after processing revealed that the Novel MFB Protocol (Group 3) resulted in a product with undetectable levels of E. coli and Salmonella spp. in 25g samples. The total aerobic count and yeast/mold counts were reduced to <100 CFU/g, which is significantly lower than the counts in Group 1 and Group 2, which were in the range of 10³-10⁴ CFU/g. This demonstrates the efficacy of the closed-system, integrated processing in minimizing post-disinfection contamination.

The final product from Group 3 had a water activity (a_w) of 0.55 ± 0.02, firmly below the threshold of 0.6 required for shelf-stability against microbial growth and enzymatic activity (Tapia et al., 2020). Accelerated Shelf-Life Testing (ASLT) confirmed this stability. After 6 months of storage at 37°C, the product showed no significant changes (p > 0.05) in moisture content, a_w, TPC, or antioxidant activity. Furthermore, microbiological counts remained stable and within safe limits throughout the storage period, confirming that the novel protocol successfully produces a shelf-stable, safe, and nutritionally robust product.

Discussion

The present study successfully demonstrates the development and validation of a novel, integrated bioprocessing protocol that effectively addresses the major technological bottlenecks associated with the industrial production of nutritionally enhanced, shelf-stable activated wheat. The results unequivocally show that the Multi-Function Bioreactor (MFB) system not only streamlines production but also yields a final product with superior nutritional and functional qualities compared to both traditional and modern lab-scale methods.

The most significant achievement of the novel protocol is its ability to maximize the nutritional benefits of sprouting while simultaneously ensuring microbial safety and shelf-stability. The reduction of phytic acid by 85% in the MFB-produced wheat (Group 3) represents a marked improvement over both control groups. This exceptional reduction can be attributed to the optimal and controlled germination conditions within the MFB, which provided ideal hydration, temperature, and aeration (via periodic agitation) for sustained phytase activity. Crucially, the immediate transition to in-situ vacuum drying at a low temperature (50°C) likely preserved the enzyme’s activity until the moisture content dropped below a critical threshold, allowing for an extended period of phytate hydrolysis. This finding is of paramount importance, as the extent of phytate degradation is directly correlated with improved mineral bioavailability (Gupta et al., 2015). Our in vitro dialyzability results strongly support this, showing a significantly higher proportion of bioaccessible iron and zinc in Group 3, directly addressing the “nutritional paradox” of wheat outlined in the introduction.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for the superiority of the MFB’s gentle drying approach is found in the vitamin retention data. The convective hot-air drying used in the Standard Lab Control (Group 2) caused significant degradation of thermolabile vitamins like Thiamine (B1) and Pyridoxine (B6), nullifying the gains achieved during sprouting. This is a well-documented limitation of conventional drying technologies (Méndez-Lagunas et al., 2017). In stark contrast, the low-temperature vacuum-contact drying in the MFB system effectively preserved these sensitive micronutrients. The significantly higher vitamin content in the final product of Group 3 underscores the critical importance of moving beyond convective hot-air drying for high-value functional ingredients. This proves that the novel protocol avoids the counterproductive scenario where nutritional gains are lost during preservation.

Furthermore, the enhanced bioactivity profile of the MFB product, evidenced by the highest Total Phenolic Content (TPC) and antioxidant capacity (DPPH, ORAC), indicates that the benefits of gentle processing extend beyond vitamins to a broader spectrum of bioactive compounds. The 25% higher TPC in Group 3 compared to Group 2 suggests that the higher temperatures of convective drying degrade phenolic compounds and other antioxidants, which aligns with previous studies on heat-sensitive bioactives (Vashisth et al., 2011). The MFB protocol, therefore, not only preserves but also maximizes the functional potential of activated wheat, making it a more potent ingredient for health-promoting foods.

From a technological and safety perspective, the MFB system presents a transformative advance. The closed-system design, integrating disinfection, germination, and drying in-situ, virtually eliminated the risk of post-process microbial contamination. This is clearly demonstrated by the undetectable levels of pathogens and the drastically lower total microbial counts in Group 3 compared to the open-air Traditional method and the transfer-dependent Lab Control. Achieving a final water activity (a_w) of 0.55 is a key indicator of shelf-stability, effectively inhibiting microbial growth and enzymatic spoilage (Tapia et al., 2020). The successful accelerated shelf-life testing (ASLT), which showed no degradation in nutritional or microbiological quality over 6 months, confirms that the product is commercially viable and requires no refrigeration, overcoming the single greatest logistical hurdle for sprouted grains (Keppler et al., 2018).

Beyond quality, the MFB protocol offers substantial process advantages. The 33-60% reduction in total processing time, compared to the control methods, translates directly into higher throughput and lower operational costs. The reduced energy consumption per kg of water removed, achieved through the efficiency of conductive heat transfer under vacuum, further enhances the sustainability and economic feasibility of the process at an industrial scale (Motevali et al., 2014). The high level of automation ensures batch-to-batch consistency and reduces reliance on skilled labor, addressing the reproducibility issues inherent in traditional methods.

In conclusion, this study moves beyond merely confirming the benefits of sprouting. It provides a robust technological solution—the MFB system and its integrated protocol—that effectively bridges the gap between traditional knowledge and modern industrial requirement. The results prove that it is possible to produce a shelf-stable “activated wheat” ingredient that boasts significantly reduced antinutrient content, enhanced vitamin and mineral bioavailability, and superior antioxidant capacity. This novel biotechnological approach successfully mitigates the risks of contamination, nutrient degradation, and perishability that have long hindered the widespread adoption of sprouted grains. By providing a scalable, efficient, and controlled manufacturing process, this research paves the way for the broader availability of nutrient-dense, functional wheat ingredients capable of contributing to improved nutritional outcomes in global populations.

Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrates the development, optimization, and validation of a novel, integrated biotechnological protocol for the production of shelf-stable, nutritionally enhanced activated wheat. The research effectively bridges a critical gap in the functional foods sector by transforming the ancient practice of sprouting into a controlled, scalable, and industrially viable process. The cornerstone of this achievement is the design and implementation of the Multi-Function Bioreactor (MFB) system, a closed-system technology that seamlessly integrates the entire production cycle—from disinfection and soaking through controlled germination to in-situ low-temperature vacuum drying—within a single vessel.

The findings of this study unequivocally confirm that the novel protocol successfully merges the profound nutritional benefits of traditional sprouting with the non-negotiable demands of modern food production: rigorous safety, consistent quality, and extended shelf-life. While the biochemical potential of sprouting to reduce antinutrients and enhance bioactive compounds is well-documented (Lemmens et al., 2019; Benítez et al., 2021), this research provides a tangible technological solution to the pervasive challenges of microbial contamination, nutrient degradation during drying, and rapid perishability that have historically impeded its industrial application (Keppler et al., 2018; Laca et al., 2006).

The key outcome of this work is the creation of a superior functional food ingredient with a scientifically validated enhanced nutritional profile. The MFB protocol achieved an exceptional 85% reduction in phytic acid, the primary antinutrient in wheat, a result that directly translates to a significant increase in the in vitro bioavailability of essential minerals like iron and zinc. This directly addresses the issue of “hidden hunger” associated with cereal-based diets (Gibson et al., 2010). Furthermore, by employing gentle vacuum-contact drying at 50°C instead of conventional convective hot-air drying, the process preserved the heat-labile vitamins and antioxidants synthesized during germination. The significantly higher retention of B-vitamins and phenolic compounds, and the consequent superior antioxidant activity, in the MFB product compared to the lab control group proves that this method prevents the counterproductive loss of nutrients that typically occurs during stabilization (Méndez-Lagunas et al., 2017; Vashisth et al., 2011).

Beyond its nutritional superiority, the final product meets all criteria for a shelf-stable ingredient. The closed-system design ensures exceptional microbiological safety, with pathogen levels undetectable by standard methods, while the process achieves a low water activity (a_w < 0.6) that guarantees stability against microbial growth and enzymatic deterioration during storage (Tapia et al., 2020). The accelerated shelf-life testing confirmed that these nutritional and safety properties remain intact for a commercially relevant period, eliminating the need for refrigeration and enabling global distribution.

This technology represents a significant step forward in the creation of truly effective and practical functional foods. The resulting activated wheat flour is a versatile ingredient, ready for immediate integration into a wide array of conventional and novel food products. Its application can significantly enhance the nutritional density of staple foods such as bread, pasta, breakfast cereals, and snacks, offering consumers a natural and bioavailable source of essential vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants without altering established consumption habits. By providing a scalable and economically feasible manufacturing process, this research paves the way for the widespread adoption of nutrient-dense ingredients in the food industry, ultimately contributing to improved public health outcomes through everyday food choices.

Future work will focus on optimizing the protocol for other cereal and pseudo-cereal grains, conducting human clinical trials to confirm the enhanced bioavailability in vivo, and exploring the techno-functional properties of the activated wheat flour in various food matrices to facilitate its adoption by the industry.

References

- Balkrishna, A., Sharma, V. K., Das, S. K., & Mishra, S. (2022). Role of sprouting in ameliorating the nutritional and antioxidant properties of wheat: A review. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 59(3), 855–864. [CrossRef]

- Benítez, V., Cantera, S., Aguilera, Y., Mollá, E., Esteban, R. M., & Díaz, M. F. (2021). Impact of germination on starch, dietary fiber and physicochemical properties in non-conventional legumes. Food Research International, 143, 110275. [CrossRef]

- Briggs, D. E., Boulton, C. A., Brookes, P. A., & Stevens, R. (2004). Brewing: Science and Practice. Woodhead Publishing.

- Dutta, H., Mahanta, C. L., & Singh, A. (2022). Impact of drying on the nutritional and functional properties of food proteins. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 119, 57–71. [CrossRef]

- Gan, R. Y., Lui, W. Y., Wu, K., Chan, C. L., Dai, S. H., Sui, Z. Q., & Corke, H. (2017). Bioactive compounds and bioactivities of germinated edible seeds and sprouts: An updated review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 59, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R. S., Bailey, K. B., Gibbs, M., & Ferguson, E. L. (2010). A review of phytate, iron, zinc, and calcium concentrations in plant-based complementary foods used in low-income countries and implications for bioavailability. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 31(2_suppl2), S134-S146. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R. K., Gangoliya, S. S., & Singh, N. K. (2015). Reduction of phytic acid and enhancement of bioavailable micronutrients in food grains. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 52(2), 676–684. [CrossRef]

- Jaba, T. (2022). Dasatinib and quercetin: short-term simultaneous administration yields senolytic effect in humans. Issues and Developments in Medicine and Medical Research Vol. 2, 22-31.

- Keppler, S., O’Meara, S., Bakalis, S., & Leadley, C. E. (2018). Evaluation of drying technologies for the retention of physical and chemical properties of sprouted wheat. Journal of Food Engineering, 234, 31–39. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. S., & Chakkaravarthi, A. (2021). Efficacy of various chemical disinfectants on the microbial load and germination of wheat grains. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 58(5), 1947–1955. [CrossRef]

- Laca, A., Mousia, Z., Díaz, M., Webb, C., & Pandiella, S. S. (2006). Distribution of microbial contamination within cereal grains. Journal of Food Engineering, 72(4), 332–338. [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, E., Moroni, A. V., Pagand, J., Heirbaut, P., Ritala, A., Karlen, Y., ... & Delcour, J. A. (2019). Impact of cereal seed sprouting on its nutritional and technological properties: A critical review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 18(1), 305-328. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Zhang, L., Wang, X., Zhang, M., & Wang, J. (2021). Effect of germination on the nutritional and functional properties of wheat: A review. Grain & Oil Science and Technology, 4(3), 126-135. [CrossRef]

- Motevali, A., Koloor, R. T., & Khoshtaghaza, M. H. (2014). Comparison of energy parameters and specific energy in different drying methods of chamomile. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, 16(4), 913-926.

- Méndez-Lagunas, L., Rodríguez-Ramírez, J., Cruz-Gracida, M., Sandoval-Torres, S., & Barriada-Bernal, G. (2017). Convective drying of wheat: Effect of temperature on nutritional and functional properties. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 54(5), 1221–1227. [CrossRef]

- Ndaw, S., Bergaentzle, M., Aoude-Werner, D., & Hasselmann, C. (2000). Extraction procedures for the liquid chromatographic determination of thiamin, riboflavin and vitamin B6 in foodstuffs. Food Chemistry, 71(1), 129–138. [CrossRef]

- Pal, R. S., Bhartiya, A., Yadav, P., Kant, L., Mishra, K. K., Aditya, J. P., & Pattanayak, A. (2016). Effect of dehulling, germination and cooking on nutrients, anti-nutrients, fatty acid composition and antioxidant properties in lentil (Lens culinaris). Journal of Food Science and Technology, 54(4), 909–920. [CrossRef]

- Prior, R. L., Wu, X., & Schaich, K. (2005). Standardized methods for the determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolics in foods and dietary supplements. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 53(10), 4290–4302. [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P. R., & Hey, S. J. (2015). The contribution of wheat to human diet and health. Food and Energy Security, 4(3), 178-202. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., Sharma, S., Singh, B., & Kaur, G. (2020). Engineering and technological aspects of cereal grain drying. In Engineering Practices for Agricultural Production and Water Conservation (pp. 255-278). CRC Press.

- Singh, A. K., Rehal, J., Kaur, A., & Jyot, G. (2015). Enhancement of attributes of cereals by germination and fermentation: A review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 55(11), 1575-1589. [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V. L., Orthofer, R., & Lamuela-Raventós, R. M. (1999). Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods in Enzymology, 299, 152–178. [CrossRef]

- Tapia, M. S., Alzamora, S. M., & Chirife, J. (2020). Effects of water activity (a_w) on microbial stability: As a hurdle in food preservation. In Water Activity in Foods: Fundamentals and Applications (pp. 323-355). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Taze, B. H., Unluturk, S., Buzrul, S., & Alpas, H. (2015). The impact of different disinfection methods on the microbial load of broccoli. Food Control, 50, 314–320. [CrossRef]

- Tkemaladze, J. (2023). Reduction, proliferation, and differentiation defects of stem cells over time: a consequence of selective accumulation of old centrioles in the stem cells?. Molecular Biology Reports, 50(3), 2751-2761.

- Tkemaladze, J. (2024). Editorial: Molecular mechanism of ageing and therapeutic advances through targeting glycative and oxidative stress. Front Pharmacol. 2024 Mar 6;14:1324446. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1324446. PMID: 38510429; PMCID: PMC10953819.

- Vashisth, D., Singh, R. K., & Pegg, R. B. (2011). Effects of drying on the phenolics content and antioxidant activity of muscadine pomace. *LWT - Food Science and Technology, 44*(7), 1649-1657. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).