Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Model Construction and Its Estimator

2.1. Model

2.2. Spatial Dependence Measures

- for all ,

- for all , with .

3. Asymptotic Properties

3.1. Background Information and Assumptions

- (H1)

-

Here, denotes the ball of radius r centered at a.

- (H2)

- The function satisfies the summability condition:

- (H3)

- For all , the following holds:where .

- (H4)

- There exists a neighborhood of a such that for all and ,with , .

- (H5)

- The kernel K has compact support on and satisfies:where denotes the indicator function of the interval .

- (H6)

- The function H belongs to the class , has compact support, and possesses bounded derivatives.

- (H7)

- There exist constants:such that:andwhere:

3.2. Main Result

4. A Simulation Study

4.1. Simulation Design

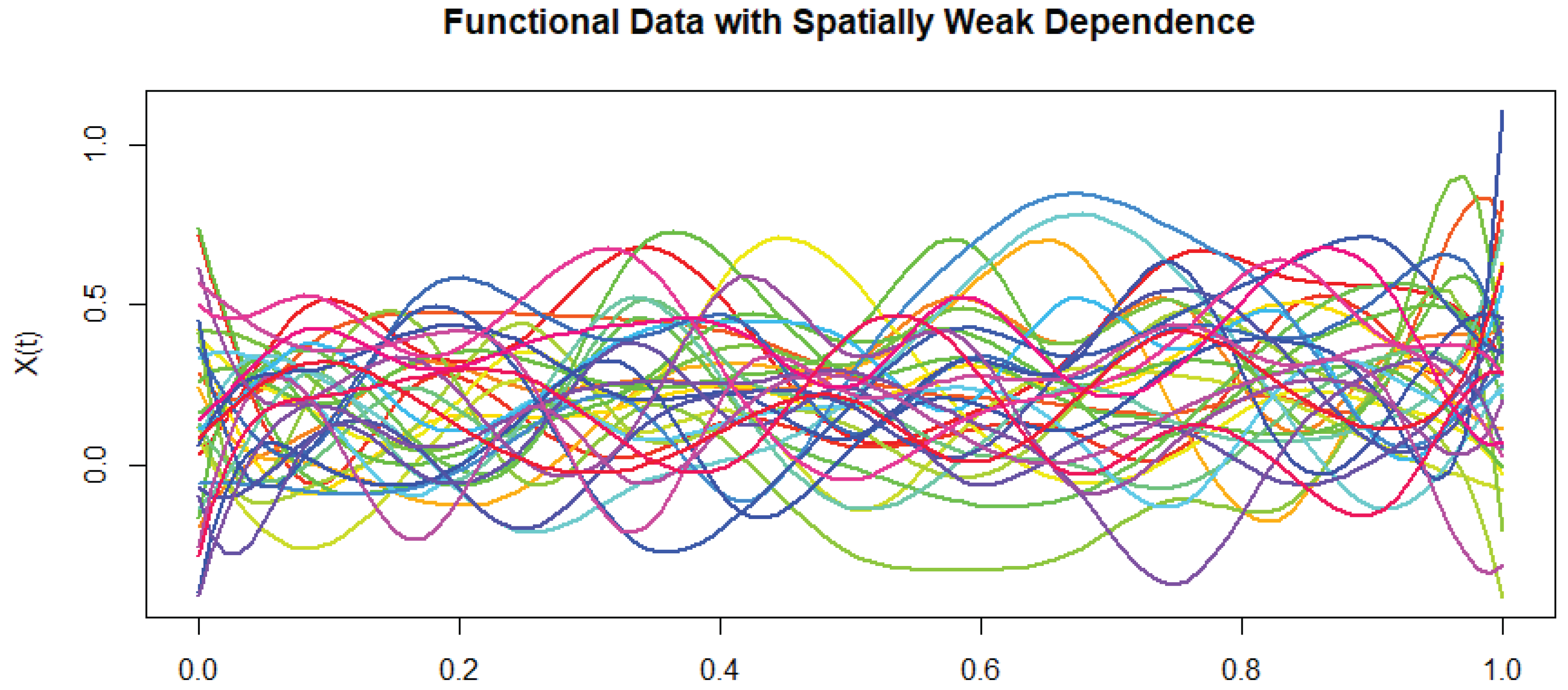

4.2. Visualization of Functional Data

4.3. Simulation Procedure

- Parameter Initialization: Define , bandwidths , , and basis size (e.g., 15 B-splines). Choose functions , and .

- Data Generation: Each functional covariate is generated as:where , and is a spatially correlated perturbation modeled via exponential decay: .

- Response Variable: For each , compute:

-

Kernel Estimation: We employ the nonparametric estimator defined in Equation (1), where denotes the distance between functional covariates, H corresponds to the Gaussian cumulative distribution function, and K is the Epanechnikov kernel defined by:K is the Epanechnikov kernel, and H is the Gaussian CDF.

- Evaluation and Metrics: We compute pointwise metrics:estimated via Monte Carlo replications.

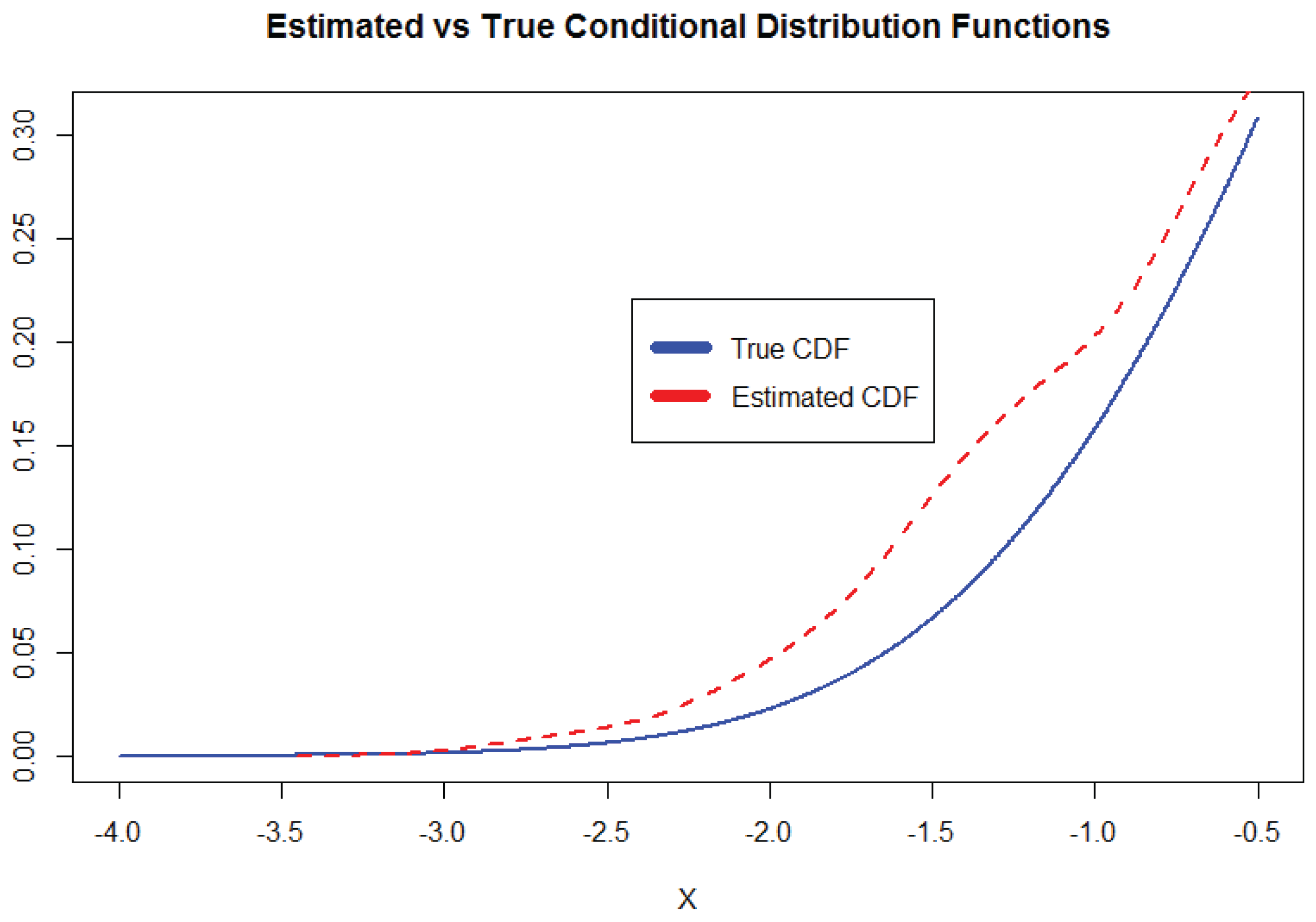

- Visualization: Plot against to visually assess the quality of the estimator across different ranges of b.

4.4. Results and Visual Analysis

4.5. Summary of Findings

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Newman, M. The Role of Research in This Association. Journal of School Health 1984, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneiros, G.; Cao, R.; Fraiman, R.; Genest, C.; Vieu, P. Recent advances in functional data analysis and high-dimensional statistics. J. Multivariate Anal.170, 3–9. [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, J.; Silverman, B. W. Functional Data Analysis; Springer: New York, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay, J.; Hooker, G.; Graves, S. Functional Data Analysis with R and MATLAB; Springer: New York, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Doukhan, P.; Louhichi, S. A new weak dependence condition and applications to moment inequalities. Stochastic Process. Appl. 1999, 84, 313–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matula, P. A note on the almost sure convergence of sums of negatively dependent random variables. Stat. Probab. Lett. 1992, 15, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, C.M. Asymptotic independence and limit theorems for positively and negatively dependent random variables. In Inequalities in Statistics and Probability; IMS Lecture Notes Monograph Series 1984, 5, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Roussas, G.G. Positive and negative dependence with some statistical applications. In Asymptotics, Nonparametrics and Time Series; Ghosh, S., Ed.; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, USA, 1999; pp. 757–788. [Google Scholar]

- Doukhan, P.; Louhichi, S. A new weak dependence condition and applications to moment inequalities. Stochastic Process. Their Appl. 1999, 84, 313–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulinski, A.; Suquet, C. Normal approximation for quasi-associated random fields. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2001, 54, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douge, L. Théorèmes limites pour des variables quasi-associées hilbertiennes. Ann. Inst. Stat. Univ. Paris 2010, 54, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Attaoui, S.; Laksaci, A.; Ould-Said, E. Asymptotic Results for an M-estimator of the Regression Function for Quasi-Associated Processes. In Functional Statistics and Applications. Contributions to Statistics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudi, H.; Mechab, B.; Chikr Elmezouar, Z. Asymptotic normality of a conditional hazard function estimate in the single index for quasi-associated data. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2020, 49, 513–530. [Google Scholar]

- Daoudi, H.; Mechab, B. Asymptotic Normality of the Kernel Estimate of Conditional Distribution Function for the quasi-associated data. Pak. J. Stat. Oper. Res. 2019, 15, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudi, H.; Mechab, B.; Benaissa, S.; Rabhi, A. Asymptotic normality of the nonparametric conditional density function estimate with functional variables for the quasi-associated data. Int. J. Stat. Econ. 2019, 20, 94–106. [Google Scholar]

- Laksaci, A.; Mechab, W. Nonparametric relative regression for associated random variables. Metron 2016, 74, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaoui, S.; Bouzebda, S.; Chesneau, C.; Liu, J. Uniform almost sure convergence and asymptotic distribution of the wavelet-based estimators of partial derivatives of multivariate density function under weak dependence. J. Nonparametr. Stat. 2021, 33, 170–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaker, I.; Belguerna, A.; Daoudi, H. The consistency of the kernel estimation of the function conditional density for associated data in high-dimensional statistics. J. Sci. Arts 2022, 22, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudi, H.; Belguerna, A.; Elmezouar, Z.C.; Alshahrani, F. Conditional Density Kernel Estimation Under Random Censorship for Functional Weak Dependence Data. J. Math. 2025, Article ID 2159604. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1155/jom/2159604.

- Daoudi, H.; Elmezouar, Z.C.; Alshahrani, F. Asymptotic Results of Some Conditional Nonparametric Functional Parameters in High Dimensional Associated Data. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzebda, S.; Laksaci, A.; Mohammedi, M. The k-nearest neighbors method in single index regression model for functional quasi-associated time series data. Rev. Mat. Complut. 2023, 36, 361–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzebda, S.; Laksaci, A.; Mohammedi, M. Single Index Regression Model for Functional Quasi-Associated Time Series Data. REVSTAT-Statistical Journal 2023, 20, 605–631. [Google Scholar]

- Mechab, W.; Laksaci, A. Nonparametric relative regression for associated random variables. Metron 2016, 74, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudi, H.; Mechab, B.; Elmezouar, C.Z. Asymptotic Normality of a Conditional Hazard Function Estimate in the Single Index for Quasi-Associated Data. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods2018, Article ID 1549248.

- Tran, L.T. Kernel density estimation on random fields. J. Multivariate Anal. 1990, 34, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabo-Niang, S.; Yao, A.F. Kernel regression estimation for continuous spatial processes. Math. Methods Statist. 2007, 16, 298–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbon, M.; Francq, C.; Tran, L.T. Kernel regression estimation for random fields. J. Statist. Plann. Inference 2007, 137, 778–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tran, L.T. Nonparametric estimation of conditional expectation. J. Statist. Plann. Inference 2009, 139, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fix, E.; Hodges, J.L. Discriminatory Analysis, Nonparametric Discrimination: Consistency Properties. Technical Report 4, USAF School of Aviation Medicine, Randolph Field, 1951.

- Cover, T.M.; Hart, P.E. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1967, 13, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressie, N.A. Statistics for Spatial Data; Wiley: New York, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Biau, G.; Cadre, B. Nonparametric spatial prediction. Stat. Inference Stoch. Process. 2004, 7, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraty, F.; Rabhi, A.; Vieu, P. Estimation non-paramétrique de la fonction de hasard avec variable explicative fonctionnelle. Rev. Roumaine Math. Pures Appl. 2008, 53, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Masry, E. Recursive probability density estimation for weakly dependent stationary processes. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1986, 32, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, T.; Hall, P.; Presnell, B. Nonparametric estimation of the mode of a distribution of random curves. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1998, 60, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraty, F.; Vieu, P. Nonparametric Functional Data Analysis: Theory and Practice; Springer Series in Statistics: New York, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraty, F.; Laksaci, A.; Tadj, A.; Vieu, P. Rate of uniform consistency for nonparametric estimates with functional variables. J. Stat. Plann. Inference 2010, 140, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara-Zaitri, L.; Laksaci, A.; Rachdi, M.; Vieu, P. Uniform in bandwidth consistency for various kernel estimators involving functional data. J. Nonparametr. Stat. 2017, 29, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraty, F.; Peuch, A.; Vieu, P. Modèle à indice fonctionnel simple. Comptes Rendus Math. 2003, 336, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzahrioui, M.; Ould-Saïd, E. Asymptotic Results of a Nonparametric Conditional Quantile Estimator for Functional Time Series. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2008, 37, 2735–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzahrioui, M.; Ould-Saïd, E. On the asymptotic properties of a nonparametric estimator of the conditional mode for functional dependent data. J. Nonparametr. Stat. 2008, 20, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laksaci, A. Convergence en moyenne quadratique de l’estimateur à noyau de la densité conditionnelle avec variable explicative fonctionnelle. Ann. Inst. Stat. Univ. Paris 2007, 51, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Laksaci, A.; Maref, F. Estimation non paramétrique de quantiles conditionnels pour des variables fonctionnelles spatialement dépendantes. Comptes Rendus Math. 2009, 347, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doob, J.L. Stochastic Processes; John Wiley and Sons: New York, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Kallabis, R.S.; Neumann, M.H. An exponential inequality under weak dependence. Bernoulli 2006, 12, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosq, D. Linear Processes in Function Spaces: Theory and Applications; Lecture Notes in Statistics 149; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay, J.O.; Silverman, B.W. Applied Functional Data Analysis: Methods and Case Studies; Springer-Verlag: New York, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraty, F.; Laksaci, A.; Vieu, P. Estimating some characteristics of the conditional distribution in nonparametric functional models. Stat. Inference Stoch. Process. 2006, 9, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraty, F.; Laksaci, A.; Vieu, P. Functional time series prediction via conditional mode estimation. C. R. Math. Acad. Sci. Paris 2005, 340, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardot, H.; Crambes, C.; Sarda, P. Spline estimation of conditional quantiles for functional covariates. C. R. Math. Acad. Sci. Paris 2004, 339, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gooijer, J.; Gannoun, A. Nonparametric conditional predictive regions for time series. Comput. Statist. Data Anal. 2000, 33, 259–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, A.; Gin, E. The Central Limit Theorem for Real and Banach Valued Random Variables; Wiley Series in Probability and Mathematical Statistics; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA; Chichester, UK; Brisbane, Australia, 1980; p. xiv+233.

- Mohammedi, M.; Bouzebda, S.; Laksaci, A.; Bouanani, O. Asymptotic normality of the k-NN single index regression estimator for functional weak dependence data. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2022, 33, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudi, H.; Mechab, B.; Belguerna, A. Asymptotic Results of a Conditional Risk Function Estimate for Associated Data Case in High-Dimensional Statistics. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Advances in Mathematics and Informatics (ICRAMI), 2021; Conference Paper. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9585904.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).