Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Variables and Measurement Instruments

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Variables and Personal History

2.3.2. Lifestyle Factors

2.3.3. Arterial Stiffness

2.3.4. Cardiovascular Risk Factors

2.3.5. Anthropometric Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

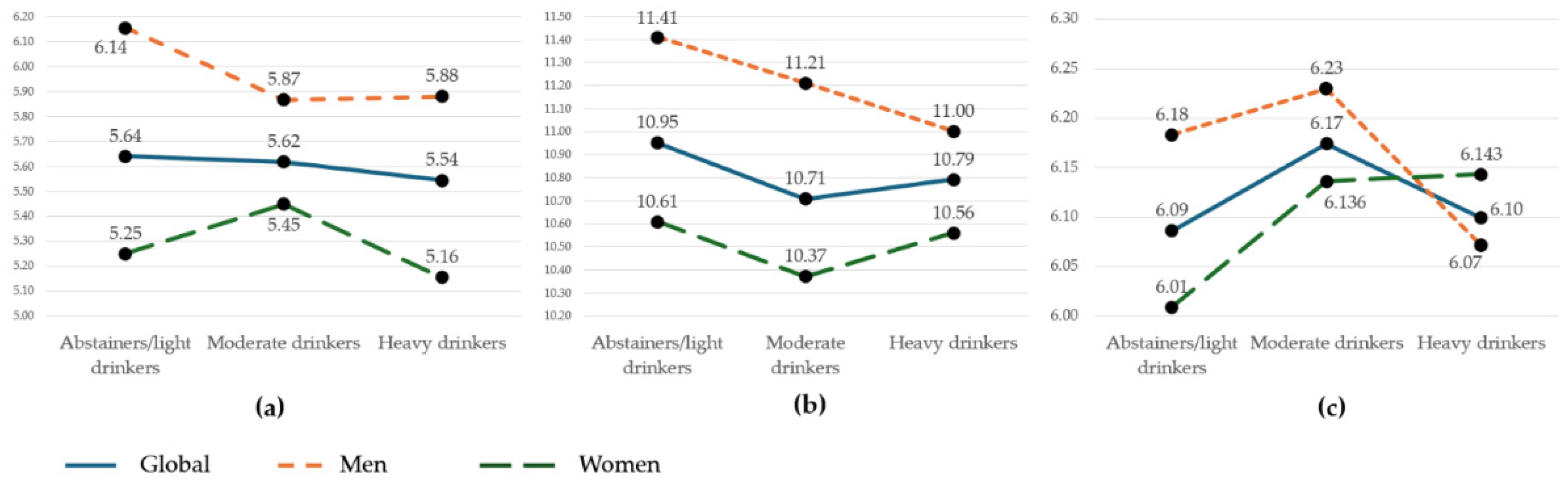

3.2. Arterial Stiffness According to Alcohol Consumption Tertiles

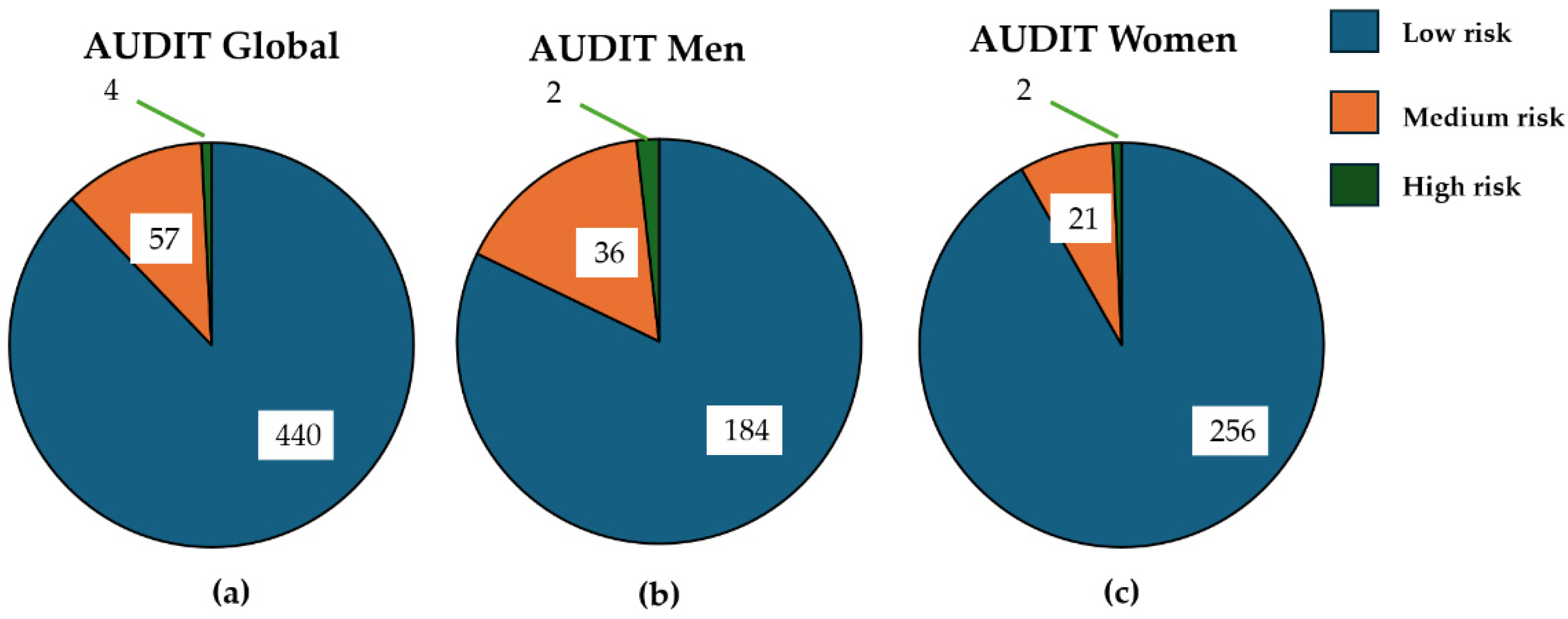

3.3. Risk Drinking According to AUDIT

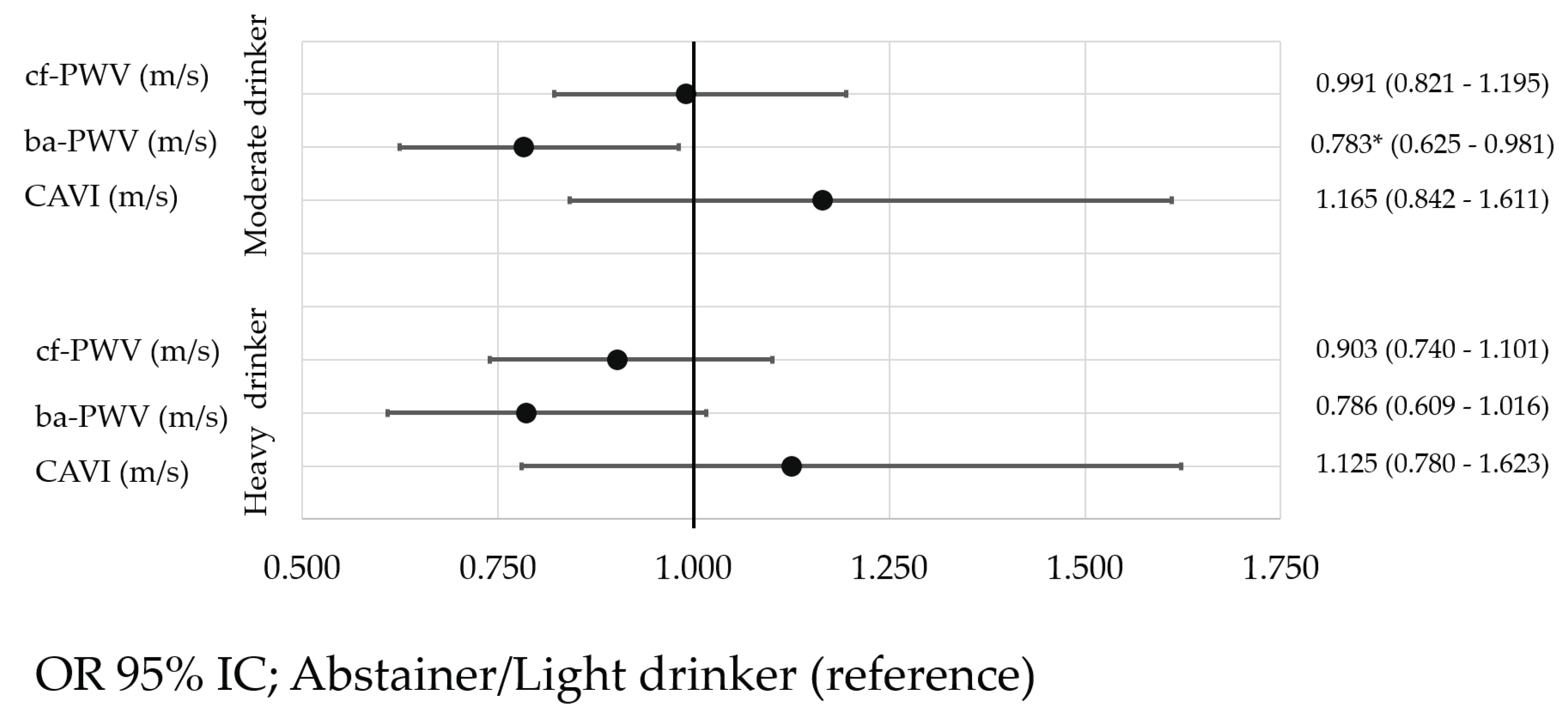

3.4. Association Between Alcohol Consumption and Arterial Stiffness

4. Discussion

4.1. Arterial Stiffness Values

4.2. Alcohol Consumption and Arterial Stiffness

4.3. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

EVA-Adic Investigators Group The members of the EVA-Adic Group are

Informed Consent Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cf-PWV | carotid–femoral pulse wave velocity |

| ba-PWV | brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity |

| CAVI | cardio-ankle vascular index |

| AUDIT | Alcohol Use Disorders Identification TEST |

| MEDAS | Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener |

| IPAQ-SF | International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form |

| METs-min/week | metabolic equivalent of task |

| SBP | systolic blood pressure |

| DBP | diastolic blood pressure |

| PP | pulse pressure |

| BMI | body mass index |

References

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health and treatment of substance use disorders; 2024.

- European Union Drugs Agency. Prevalence of drug use, Alcohol, Lifetime prevalence, Young adults (15-34). Available online: https://www.euda.europa.eu/data/stats2024/gps_en#displayTable:GPS-128 (accessed on 01/12/2024).

- Observatorio Español de las Drogas y las Adicciones. Informe 2024. Alcohol, tabaco y drogas ilegales en España. 2024, 1-74.

- Seaman., P.; Ikegwuonu, T. Drinking to belong. Understanding young adults’ alcohol use within social networks; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: Glasgow, 2010; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Boutouyrie, P.; Chowienczyk, P.; Humphrey, J.D.; Mitchell, G.F. Arterial Stiffness and Cardiovascular Risk in Hypertension. Circulation Research 2021, 128, 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, X.; Chen, L.; Shi, Y.; Suo, Y.; Liao, S.; Cheang, I.; Gao, R.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, W.; et al. Comparison of arterial stiffness indices measured by pulse wave velocity and pulse wave analysis for predicting cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in a Chinese population. Hypertension Research 2024, 47, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.L.; Kim, S.H. Pulse Wave Velocity in Atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2019, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, M.; Topouchian, J.; Labat, C.; Gautier, S.; Blacher, J.; Cwynar, M.; de la Sierra, A.; Pall, D.; Duarte, K.; Fantin, F.; et al. Cardio-ankle vascular index for predicting cardiovascular morbimortality and determinants for its progression in the prospective advanced approach to arterial stiffness (TRIPLE-A-Stiffness) study. EBioMedicine 2024, 103, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, K.; Fryer, S.; McDonnell, B.J.; Meyer, M.L.; Faulkner, J.; Agharazii, M.; Fortier, C.; Pugh, C.J.A.; Paterson, C.; Zieff, G.; et al. Aortic-Femoral Stiffness Gradient and Cardiovascular Risk in Older Adults. Hypertension 2024, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.L.; Muchira, J.; Hibner, B.A.; Phillips, S.A.; Piano, M.R. Alcohol Consumption: A New Risk Factor for Arterial Stiffness? Cardiovascular Toxicology 2022, 22, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cypiene, A.; Gimzauskaite, S.; Rinkuniene, E.; Jasiunas, E.; Laucevicius, A.; Ryliskyte, L.; Badariene, J. Effect of Alcohol Consumption Habits on Early Arterial Aging in Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome and Elevated Serum Uric Acid. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Neill, D.; Britton, A.; Brunner, E.J.; Bell, S. Twenty-Five-Year Alcohol Consumption Trajectories and Their Association With Arterial Aging: A Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of American Heart Association 2017, 6, e005288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, R.; Zhang, J.; Kiran, M.; Ball, G. Alcohol and arterial stiffness in middle-aged and older adults: Cross-sectional evidence from the UK Biobank study. Alcohol Clinical & Experimental Research 2024, 48, 1915–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piano, M.R. Alcohol’s Effects on the Cardiovascular System. Alcohol Research 2017, 38, 219–241. [Google Scholar]

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Back, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. European Heart Journal 2021, 42, 3227–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasnim, S.; Tang, C.; Musini, V.M.; Wright, J.M. Effect of alcohol on blood pressure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020, 7, CD012787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Cooke, A.B.; Scheffler, P.; Doonan, R.J.; Daskalopoulou, S.S. Alcohol Exerts a Shifted U-Shaped Effect on Central Blood Pressure in Young Adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2021, 36, 2975–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Sola, J. Cardiovascular risks and benefits of moderate and heavy alcohol consumption. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2015, 12, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, S.; Sharma, A.; Garg, A. Effect of Alcohol Consumption on Cardiovascular Health. Current Cardiology Report 2018, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwll, T.; Zhao, J.; Panwar, S.; Roemer, A.; Naimi, T.; Chikritzhs, T. Do “Moderate” Drinkers Have Reduced Mortality Risk? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis ofAlcohol Consumption and All-Cause Mortality. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs 2016, 77, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Stockwell, T.; Naimi, T.; Churchill, S.; Clay, J.; Sherk, A. Association Between Daily Alcohol Intake and Risk of All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses. JAMA Network Open 2023, 6, e236185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018, 392, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Sanchez, J.; Garcia-Ortiz, L.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, E.; Maderuelo-Fernandez, J.A.; Tamayo-Morales, O.; Lugones-Sanchez, C.; Recio-Rodriguez, J.I.; Gomez-Marcos, M.A.; Investigators, E.V.A. The Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption With Vascular Structure and Arterial Stiffness in the Spanish Population: EVA Study. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research 2020, 44, 1816–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Romero, S.; Gomez-Sanchez, L.; Suarez-Moreno, N.; Navarro-Caceres, A.; Dominguez-Martin, A.; Lugones-Sanchez, C.; Tamayo-Morales, O.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, S.; Castro-Rivero, A.B.; Gomez-Sanchez, M.; et al. Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and Vascular Structure and Arterial Stiffness in Adults Diagnosed with Persistent COVID: BioICOPER Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giorno, R.; Maddalena, A.; Bassetti, S.; Gabutti, L. Association between Alcohol Intake and Arterial Stiffness in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddinger, K.J.; Emdin, C.A.; Haas, M.E.; Wang, M.; Hindy, G.; Ellinor, P.T.; Kathiresan, S.; Khera, A.V.; Aragam, K.G. Association of Habitual Alcohol Intake With Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e223849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charakida, M.; Georgiopoulos, G.; Dangardt, F.; Chiesa, S.T.; Hughes, A.D.; Rapala, A.; Davey Smith, G.; Lawlor, D.; Finer, N.; Deanfield, J.E. Early vascular damage from smoking and alcohol in teenage years: the ALSPAC study. European Heart Journal 2019, 40, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.L.; Piano, M.R.; Thur, L.A.; Peters, T.A.; da Silva, A.L.G.; Phillips, S.A. The effects of repeated binge drinking on arterial stiffness and urinary norepinephrine levels in young adults. J Hypertens 2020, 38, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiina, K.; Takahashi, T.; Nakano, H.; Fujii, M.; Iwasaki, Y.; Matsumoto, C.; Yamashina, A.; Chikamori, T.; Tomiyama, H. Longitudinal Associations between Alcohol Intake and Arterial Stiffness, Pressure Wave Reflection, and Inflammation. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis 2023, 30, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiwaki, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nishida, R.; Matsumoto, N. Dose of Alcohol From Beer Required for Acute Reduction in Arterial Stiffness. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiwaki, M.; Kora, N.; Matsumoto, N. Ingesting a small amount of beer reduces arterial stiffness in healthy humans. Physiological Reports 2017, 5, e13381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, S.; Yoshioka, E.; Saijo, Y.; Kita, T.; Okada, E.; Tamakoshi, A.; Kishi, R. Relation between alcohol consumption and arterial stiffness: A cross-sectional study of middle-aged Japanese women and men. Alcohol 2013, 47, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Gabriel, S.; Lugones-Sanchez, C.; Tamayo-Morales, O.; Vicente Prieto, A.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, S.; Conde Martin, S.; Gomez-Sanchez, M.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, E.; Garcia-Ortiz, L.; Gomez-Sanchez, L.; et al. Relationship between addictions and obesity, physical activity and vascular aging in young adults (EVA-Adic study): a research protocol of a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, S.Á.; Casado, P.G.; Cruz, C.l.T.d.l.; Fernandez, F.B. Papel del test AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) para la detección de consumo excesivo de alcohol en atención primaria. Revista de Medicina Familiar y Comunitaria 2001, 11, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad Gobierno de España. Límites de Consumo de Bajo Riesgo de Alcohol Actualización del riesgo relacionado con los niveles de consumo de alcohol, el patrón de consumo y el tipo de bebida Parte 1. Actualización de los límites de consumo de bajo riesgo de alcohol. 2020, 24-25.

- Schröder, H.; Fito, M.; Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Ros, E.; Salaverría, I.; Fiol, M.; et al. A short screener is valid for assessing mediterranean diet adherence among older spanish men and women. The Journal of Nutrition Nutritional Epidemiology 2011, 141, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunstall-Pedoe, H. The World Health Organization MONICA Project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): a major international collaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1988, 41, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.H.; Macfarlane, D.J.; Lam, T.H.; Stewart, S.M. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2011, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier, C.; Agharazii, M. Arterial Stiffness Gradient. Pulse (Basel) 2016, 3, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirai, K.; Hiruta, N.; Song, M.; Kurosu, T.; Suzuki, J.; Tomaru, T.; Miyashita, Y.; Saiki, A.; Takahashi, M.; Suzuki, K.; et al. Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index (CAVI) as a Novel Indicator of Arterial Stiffness: Theory, Evidence and Perspectives. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis 2011, 18, 924–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashina, A.; Tomiyama, H.; Takeda, K.; Tsuda, H.; Arai, T.; Hirose, K.; Koji, Y.; Hori, S.; Yamato, Y. Validity, Reproducibility, and Clinical Significance of Noninvasive Brachial-Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity Measurement. Hypertens Research 2002, 25, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai. T; Ohishi. M; Onishi. M; Ito. N; Takeya. Y; Maekawa. Y; Rakugi. H. Cut-Off Value of Brachial-Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity to Predict Cardiovascular Disease in Hypertensive Patients: A Cohort Study. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis 2013, 20, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.L.; Coca, A.; de Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. European Heart Journal 2018, 39, 3021–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Salvadó, J.; Rubio, M.A.; Barbany, M.; Moreno, B. Consenso SEEDO 2007 para la evaluación del sobrepeso y la obesidad y el establecimiento de criterios de intervención terapéutica. Medicina Clínica 2007, 128, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 02-01-2025).

- Association, W.M. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants. JAMA 2025, 333, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiwaki, M.; Kume, D.; Matsumoto, N. Investigations of segmental arterial stiffness in a cross-sectional study on young adult male trained swimmers, cyclists, and non-trained men. Physiological Reports 2025, 13, e70186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, M.; Nomura, K.; Karita, K.; Nishikitani, M.; Yano, E. Relationship between Brachial-Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity and Heart Rate Variability in Young Japanese Men. Hypertension Research 2004, 27, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaruchart, T.; Suwanwela, N.C.; Tanaka, H.; Suksom, D. Arterial stiffness is associated with age-related differences in cerebrovascular conductance. Exp Gerontol 2016, 73, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yufu, K.; Takahashi, N.; Hara, M.; Saikawa, T.; Yoshimatsu, H. Measurement of the brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity and flow-mediated dilatation in young, healthy smokers. Hypertension Research 2007, 30, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiming, G.; Zhou, X.; Lv, W.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Li, Y.; Xing, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Reference values of brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity according to age and blood pressure in a central Asia population. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0171737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S.G.; Arakeri, S.; Khode, V. Association of Low BMI with Aortic Stiffness in Young Healthy Individuals. Current Hypertension Reviews 2021, 17, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutouyrie, P.; Vermeersch, S.J. Determinants of pulse wave velocity in healthy people and in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors: 'establishing normal and reference values'. European Heart Journal 2010, 31, 2338–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaje, A.O.; Barmi, S.; Sansum, K.M.; Baynard, T.; Barker, A.R.; Tuomainen, T.P. Temporal longitudinal associations of carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity and carotid intima-media thickness with resting heart rate and inflammation in youth. Journal of Applied Physiology 2023, 134, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, D.; Teren, A.; Wirkner, K.; Loeffler, M.; Scholz, M. Parameters of pulse wave velocity: determinants and reference values assessed in the population-based study LIFE-Adult. Clinical Research in Cardiology 2018, 107, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.; Zocalo, Y.; Bia, D.; Wray, S.; Fischer, E.C. Reference intervals and percentiles for carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity in a healthy population aged between 9 and 87 years. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension 2018, 20, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdel, D.M.; Gadberry, J.J.; Burke, S.L.; Carlini, N.A.; Fleenor, B.S.; Campbell, M.S. Dietary fat and alcohol in the prediction of indices of vascular health among young adults. Nutrition 2021, 84, 111120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, S.J.; Moody, A.M.; McCoy, S.M.; Barinas-Mitchell, E.; Jakicic, J.M.; Gibbs, B.B. Effects on carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity 24 h post exercise in young healthy adults. Hypertens Res 2016, 39, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.J.; Lee, P.Y.; Chuang, Y.H.; Huang, C.C. Measurement of local pulse wave velocity for carotid artery by using an ultrasound-based method. Ultrasonics 2020, 102, 106064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiwaki, M.; Takahara, K.; Matsumoto, N. Arterial stiffness in young adult swimmers. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2017, 117, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, A.; Kotani, K.; Bushueva, O.; Taniguchi, N.; Lazarenko, V. The cardio-ankle vascular index and ankle-brachial index in young russians. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis 2015, 22, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uurtuya, S.; Taniguchi, N.; Kotani, K.; Yamada, T.; Kawano, M.; Khurelbaatar, N.; Itoh, K.; Lkhagvasuren, T. Comparative study of the cardio-ankle vascular index and ankle-brachial index between young Japanese and Mongolian subjects. Hypertension Research 2009, 32, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Hou, L.; Cui, M.; Mourot, L.; Zhu, W. Acute effects of low-volume intermittent versus higher-volume continuous exercise on arterial stiffness in healthy young men. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, W.; Chen, X.; Wu, H.; Yan, S. Acute effects of moderate-intensity continuous and accumulated exercise on arterial stiffness in healthy young men. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2015, 115, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huck, C.J.; Bronas, U.G.; Williamson, E.B.; Draheim, C.C.; Duprez, D.A.; Dengel, D.R. Noninvasive measurements of arterial stiffness: repeatability and interrelationships with endothelial function and arterial morphology measures. Vascular Health and Risk Management 2007, 3, 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J.; Baek, H.J. A Comparative Study of Brachial-Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity and Heart-Finger Pulse Wave Velocity in Korean Adults. Sensors (Basel) 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizzadeh, M.; Karimi, A.; Breyer-Kohansal, R.; Hartl, S.; Breyer, M.K.; Gross, C.; Boutouyrie, P.; Bruno, R.M.; Hametner, B.; Wassertheurer, S.; et al. Reference equations for pulse wave velocity, augmentation index, amplitude of forward and backward wave in a European general adult population. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 23151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagura, C.; Takamura, N.; Kadota, K.; Nagazumi, T.; Morishita, Y.; Nakazato, M.; Maeda, T.; Kusano, Y.; Abe, Y.; Aoyagi, K. Evaluation of cardiovascular risk factors and related clinical markers in healthy young Japanese adults. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine 2007, 45, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namekata, T.; Suzuki, K.; Ishizuka, N.; Shirai, K. Establishing baseline criteria of cardio-ankle vascular index as a new indicator of arteriosclerosis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2011, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su-Yeon, C.; Byung-Hee, O.; Bae Park, J.; Dong-Ju, C.; Moo-Yong, R.; Sungha, P. Age-associated increase in arterial stiffness measured according to the cardio-ankle vascular index without blood pressure changes in healthy adults. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis 2013, 20, 911–923. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J.; Hwang, I.C.; Kim, K.K.; Kang, W.C.; Cha, J.Y.; Moon, Y.A. Casual alcohol consumption is associated with less subclinical cardiovascular organ damage in Koreans: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, H.; Katsuura-Kamano, S.; Yamaguchi, M.; Arisawa, K. Relationships of elevated levels of serum hepatic enzymes and alcohol intake with arterial stiffness in men. Atherosclerosis 2015, 238, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzi, K.; Rontoyanni, V.G.; Protogerou, A.D.; Georgoulia, A.; Xenos, K.; Chrysou, J.; Sfikakis, P.P.; Sidossis, L.S. Acute effects of beer on endothelial function and hemodynamics: a single-blind, crossover study in healthy volunteers. Nutrition 2013, 29, 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Safar, M.E. Influence of lifestyle modification on arterial stiffness and wave reflections. American Journal of Hypertension 2005, 18, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldo, L.; Narvaez, A.; Izzo, L.; Graziani, G.; Gaspari, A.; Minno, G.D.; Ritieni, A. Red Wine Consumption and Cardiovascular Health. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, L.M.; Rimm, E.B. Moderate alcohol consumption and coronary heart disease: a review. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2001, 77, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| . | Global (n = 501) | Men (n=222) | Women (n=279) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean o n | DS o % | Mean o n | DS o % | Mean o n | DS o % | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | 26.58 | 4.40 | 27.04 | 4.41 | 26.22 | 4.37 | 0.040 |

| Lifestyle | |||||||

| Alcohol (g/week) | 48.80 | 73.59 | 61.54 | 91.14 | 38.66 | 53.90 | < 0.001 |

| Smokers. n (%) | 70 | 14.0 | 28 | 12.61 | 42 | 15.05 | 0.434 |

| Cigarettes/day | 9.05 | 7.31 | 10.56 | 7.39 | 7.92 | 7.10 | 0.042 |

| MD (total score) | 7.44 | 2.01 | 6.96 | 2.06 | 7.81 | 1.88 | < 0.001 |

| METS/min/week | 2651 | 2490 | 3159 | 3130 | 2248 | 1730 | < 0.001 |

| Risk factors | |||||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 170.16 | 28.66 | 170.98 | 29.77 | 169.52 | 27.79 | 0.573 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 96.13 | 25.97 | 101.83 | 28.47 | 91.50 | 22.78 | < 0.001 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 58.30 | 12.85 | 52.20 | 10.84 | 63.12 | 12.26 | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 83.11 | 44.24 | 95.55 | 55.70 | 73.19 | 28.80 | < 0.001 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 81.10 | 12.43 | 82.35 | 16.20 | 80.09 | 8.18 | 0.044 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 110.94 | 11.56 | 118.61 | 10.29 | 104.84 | 8.46 | < 0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 68.08 | 7.78 | 70.15 | 8.11 | 66.44 | 7.11 | < 0.001 |

| PP (mmHg) | 42.86 | 8.45 | 48.47 | 7.90 | 38.39 | 5.81 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.04 | 3.80 | 25.30 | 3.65 | 23.03 | 3.63 | < 0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 79.39 | 11.50 | 85.23 | 10.58 | 74.74 | 9.99 | < 0.001 |

| Arterial stiffness | |||||||

| CAVI | 6.13 | 0.75 | 6.16 | 0.75 | 6.10 | 0.74 | 0.341 |

| cf-PWV (m/s) | 5.60 | 1.29 | 5.95 | 1.18 | 5.33 | 1.30 | < 0.001 |

| ba-PWV (m/s) | 10.80 | 1.01 | 11.20 | 1.05 | 10.48 | 0.84 | < 0.001 |

| . | Abstainers/light drinkers (1st tertile) (n = 142) |

Moderate drinkers (2nd tertile) (n=226) |

Heavy drinkers (3rd tertile) (n=133) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean o n | DS o % | Mean o n | DS o % | Mean o n | DS o % | p Value | |||

| Age (years) | 26.39 | 4.65 | 26.84 | 4.35 | 26.35 | 4.22 | 0.505 | ||

| Lifestyle | |||||||||

| Smokers. n (%) | 30 | (21.12) | 48 | (21.23) | 50 | (37.59) | |||

| Cigarettes/day | 10.37 | 7.26 | 9.06 | 7.17 | 8.26 | 7.51 | 0.463 | ||

| MD (total score) | 7.50 | 1.98 | 7.57 | 1.95 | 7.14 | 2.11 | 0.135 | ||

| METS/min/week | 3002.10 | 2706 | 2459 | 1802 | 2604 | 3151 | 0.121 | ||

| Risk factors | |||||||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 171.11 | 30.89 | 170.70 | 28.62 | 168.22 | 26.25 | 0.660 | ||

| LDL (mg/dL) | 97.30 | 28.47 | 97.33 | 25.12 | 92.77 | 24.41 | 0.235 | ||

| HDL (mg/dL) | 57.51 | 12.54 | 58.85 | 12.90 | 58.20 | 13.14 | 0.621 | ||

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 86.51 | 43.92 | 78.82 | 43.36 | 86.85 | 45.74 | 0.143 | ||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 82.25 | 15.51 | 79.91 | 8.47 | 81.89 | 14.22 | 0.149 | ||

| SBP (mmHg) | 111.26 | 12.30 | 109.64 | 11.41 | 112.82 | 10.77 | 0.039 | ||

| DBP (mmHg) | 68.68 | 7.99 | 67.73 | 7.72 | 68.05 | 7.67 | 0.526 | ||

| PP (mmHg) | 42.58 | 9.12 | 41.91 | 7.86 | 44.77 | 8.43 | 0.007 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.08 | 4.28 | 23.72 | 3.82 | 24.53 | 3.16 | 0.149 | ||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 78.97 | 12.27 | 78.38 | 11.41 | 81.55 | 10.55 | 0.037 | ||

| Arterial stiffness | |||||||||

| CAVI | 6.08 | 0.85 | 6.18 | 0.73 | 6.09 | 0.66 | 0.315 | ||

| cf-PWV (m/s) | 5.63 | 1.19 | 5.62 | 1.01 | 5.55 | 1.74 | 0.839 | ||

| ba-PWV (m/s) | 10.95 | 1.07 | 10.71 | 0.97 | 10.80 | 0.98 | 0.076 | ||

| . | Abstainers/light drinkers (1st tertile) (n = 61) |

Moderate drinkers (2nd tertile) (n=88) |

Heavy drinkers (3rd tertile) (n=73) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean o n | DS o % | Mean o n | DS o % | Mean o n | DS o % | p Value | |

| Age (years) | 26.03 | 4.92 | 27.74 | 4.25 | 27.03 | 4.03 | 0.067 |

| Lifestyle | |||||||

| Smokers. n (%) | 11 | (18.03) | 21 | (23.86) | 23 | (31.51) | |

| Cigarettes/day | 11.27 | 7.23 | 10.43 | 8.61 | 10.35 | 6.52 | 0.940 |

| MD (total score) | 7.20 | 1.91 | 7.00 | 2.19 | 6.73 | 2.03 | 0.413 |

| METS/min/week | 4011 | 3423 | 2704 | 1883 | 2996 | 3890 | 0.037 |

| Risk factors | |||||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 167.92 | 33.45 | 175.10 | 29.62 | 168.49 | 26.22 | 0.244 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 99.74 | 31.32 | 106.62 | 28.37 | 97.77 | 25.40 | 0.120 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 51.87 | 11.57 | 52.78 | 11.68 | 51.77 | 9.12 | 0.813 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 94.15 | 53.17 | 94.57 | 59.16 | 97.97 | 54.08 | 0.906 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 83.72 | 21.96 | 80.10 | 8.03 | 83.94 | 17.79 | 0.244 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 118.94 | 11.83 | 118.73 | 9.86 | 118.21 | 9.52 | 0.911 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 70.05 | 8.27 | 70.93 | 8.11 | 69.29 | 7.98 | 0.442 |

| PP (mmHg) | 48.89 | 8.67 | 47.80 | 7.42 | 48.92 | 7.83 | 0.596 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.92 | 3.92 | 25.59 | 3.96 | 25.25 | 2.97 | 0.542 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 83.20 | 11.46 | 86.19 | 10.57 | 85.76 | 9.72 | 0.209 |

| Arterial stiffness | |||||||

| CAVI | 6.14 | 0.89 | 6.26 | 0.71 | 6.07 | 0.65 | 0.260 |

| cf-PWV (m/s) | 6.10 | 1.32 | 5.91 | 1.06 | 5.88 | 1.22 | 0.528 |

| ba-PWV (m/s) | 11.38 | 1.08 | 11.22 | 1.05 | 11.01 | 1.02 | 0.118 |

| . | Abstainers/light drinkers (1st tertile) (n = 81) |

Moderate drinkers (2nd tertile) (n=138 |

Heavy drinkers (3rd tertile) (n=60) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean o n | DS o % | Mean o n | DS o % | Mean o n | DS o % | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | 26.67 | 4.46 | 26.26 | 4.33 | 25.53 | 4.33 | 0.312 |

| Lifestyle | |||||||

| Smokers. n (%) | 19 | 31.14 | 27 | 30.68 | 27 | 36.99 | |

| Cigarettes/day | 9.84 | 7.42 | 8.00 | 5.76 | 6.48 | 7.95 | 0.289 |

| MD (total score) | 7.73 | 2.01 | 7.93 | 1.70 | 7.65 | 2.11 | 0.553 |

| METS/min/week | 2242.38 | 1661.20 | 2302.70 | 1737.95 | 2128.19 | 1824.36 | 0.809 |

| Risk factors | |||||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 173.54 | 28.78 | 167.89 | 27.71 | 167.90 | 26.50 | 0.310 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 95.41 | 26.12 | 91.31 | 20.75 | 86.54 | 21.77 | 0.080 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 61.81 | 11.55 | 62.68 | 12.17 | 65.93 | 13.12 | 0.123 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 80.69 | 34.52 | 68.70 | 24.37 | 73.47 | 28.11 | 0.012 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 81.13 | 7.58 | 79.78 | 8.76 | 79.43 | 7.54 | 0.395 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 105.47 | 9.09 | 103.84 | 8.08 | 106.26 | 8.32 | 0.133 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 67.64 | 7.66 | 65.70 | 6.73 | 66.53 | 7.06 | 0.147 |

| PP (mmHg) | 37.83 | 6.07 | 38.15 | 5.47 | 39.73 | 6.09 | 0.124 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.45 | 4.44 | 22.52 | 3.20 | 23.65 | 3.19 | 0.063 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 75.78 | 11.96 | 73.41 | 8.88 | 76.42 | 9.22 | 0.081 |

| Arterial stiffness | |||||||

| CAVI | 6.03 | 0.82 | 6.14 | 0.73 | 6.11 | 0.67 | 0.582 |

| cf-PWV (m/s) | 5.27 | 0.95 | 5.44 | 0.94 | 5.14 | 2.16 | 0.295 |

| ba-PWV (m/s) | 10.62 | 0.94 | 10.37 | 0.75 | 10.54 | 0.88 | 0.092 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).