Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

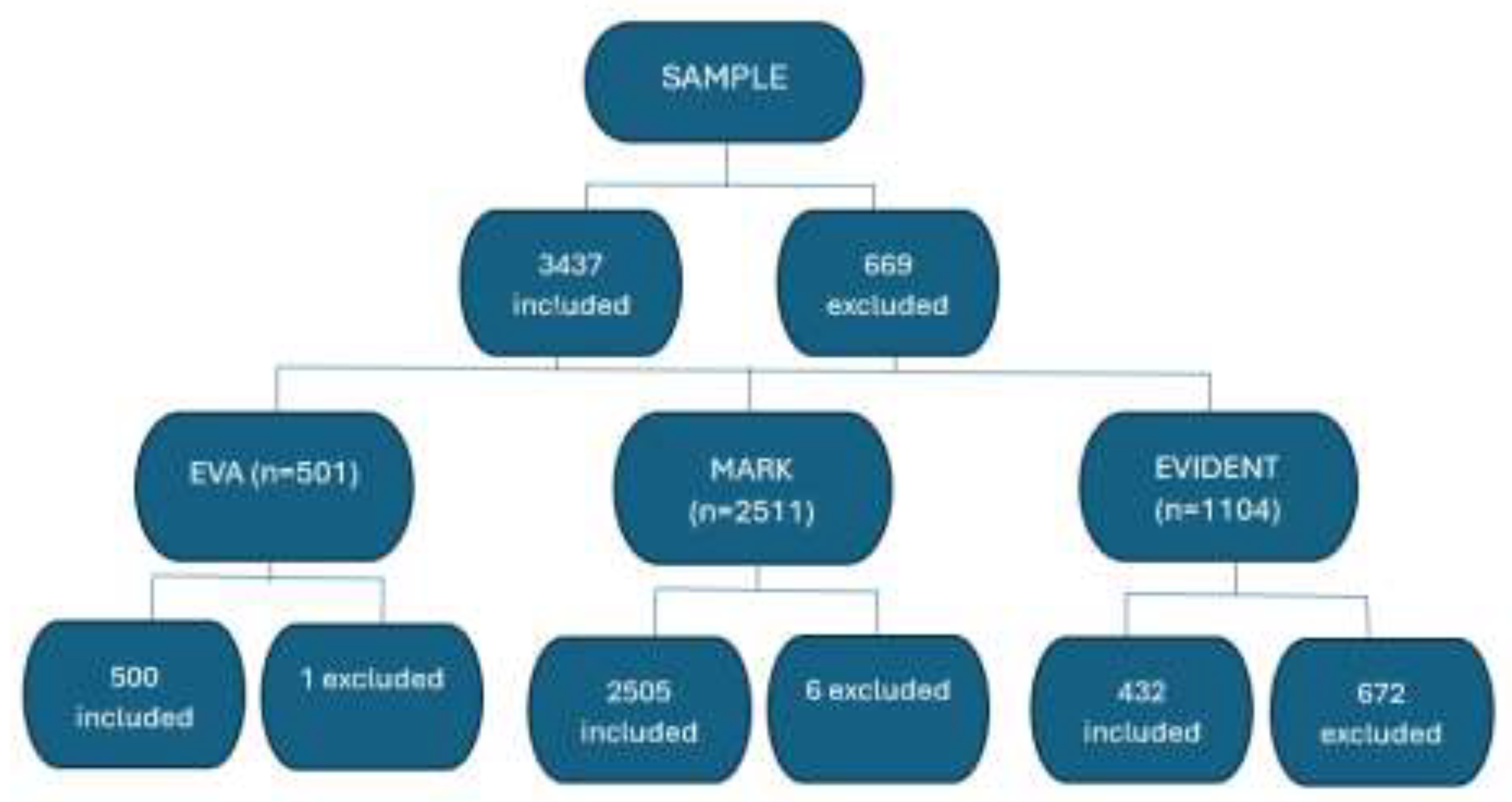

The role of the mediterranean diet (MD) on healthy vascular aging is not fully established. The main objective of this study was to analyze the association between adherence to the MD and vascular aging estimated with ankle brachial pulse wave velocity (ba-PWV) in a Spanish population sample and the differences by sex. Methods: A total of 3437 subjects from the EVA, MARK and EVIDENT studies participated. The ba-PWV was assessed with the Vasera VS-1500® device. Vascular aging was classified as healthy vascular aging (HVA), normal vascular aging (NVA) and early vascular aging (EVA) and adherence to the MD was assessed with the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener questionnaire. Results: Mean age was 60.15±9.55 (60.09±9.71 in women; 60.20±9.43 in men). Overall MD adherence was observed in 48.0% of subjects (40% in women; 54% in men). The mean value of ba-PWV was 14.38±2.71 (women 14.24±2.89; men 14.49±2.56). In multinomial logistic regression a positive association was found overall between HVA and NVA (OR=1.751, 95% CI:1.411-2.174, p<0.001), and between HVA and EVA (OR=1.501, 95% CI:1.295-1.740, p<0.001); in women between HVA and NVA (OR=2. 055, 95% CI:1.456-2.901, p<0.001) and between HVA and EVA (OR=1.413, 95% CI:1.124-1.776; p=0.003), in men between HVA and NVA (OR=1.551, 95% CI:1.175-2.047, p=0.002) and between HVA and EVA (OR=1.549, 95% CI:1.275-1.882; p<0.001). Conclusion: The results of this work indicate that greater adherence to the MD is associated with healthier vascular aging.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Variables and measuring Instruments

2.4.1. Vascular Aging

2.4.2. Mediterranean Diet

2.4.3. Vascular Function

2.4.4. Anthropometric Measurements

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Characteristics of the Subjects in Relation with Vascular Aging and Mediterranean diet

3.3. Association between ba-PWV y MD overall and by sex. Multinomial logistic regression.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mazza, E.; Ferro, Y.; Pujia, R.; Mare, R.; Maurotti, S.; Montalcini, T.; et al. Mediterranean Diet In Healthy Aging. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging 2021, 25, 1076–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorelli, M.; Perrella, A.; Bocchi, L. Detecting Vascular Age Using the Analysis of Peripheral Pulse. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2018, 65, 2742–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Yan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, Z.; Tian, S.; Khan, A.H.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, A.; Zhang, C.; Tian, X.L. Vascular Aging: Assessment and Intervention. Clin Interv Aging. 2023, 18, 1373–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka, E.; Napierała, P.; Podfigurna, A.; Męczekalski, B.; Smolarczyk, R.; Grymowicz, M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas. 2020, 139, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharska-Newton, A.M.; Stoner, L.; Meyer, M.L. Determinants of vascular age: An epidemiological perspective. Clin Chem. 2019, 65, 108–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiñónez-Bareiro, F.; Carnicero, J.A.; Alfaro-Acha, A.; Rosado-Artalejo, C.; Grau-Jimenez, M.C.; Rodriguez-Mañas, L.; et al. Risk of Frailty According to the Values of the Ankle-Brachial Index in the Toledo Study for Healthy Aging. Journal of Frailty and Aging. 2023, 12, 24–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, O.M.; Mendes, I.; Köchl, C.; Mazidi, M.; Ashor, A.W.; Rubele, S.; Minihane, A.M.; Mathers, J.C.; Siervo, M. Mediterranean diet increases endothelial function in adults: A systematic review and meta-Analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Nutr. 2020, 150, 1151–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.B.; Seo, M.W.; Jung, H.C. Effects of Aerobic vs. Resistance Exercise on Vascular Function and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Older Women. Healthcare (Switzerland). 2023, 11, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, Z.S.; Craighead, D.H.; Darvish, S.; Coppock, M.; Ludwig, K.R.; Brunt, V.E.; Seals, D.R.; Rossman, M.J. Promoting healthy cardiovascular aging: emerging topics. J Cardiovasc Aging. 2022, 2, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, S.T.; Batty, G.D.; Pentti, J.; Virtanen, M.; Alfredsson, L.; Fransson, E.I.; et al. Obesity and loss of disease-free years owing to major non-communicable diseases: a multicohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2018, 3, e490–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreo-López, M.C.; Contreras-Bolívar, V.; Muñoz-Torres, M.; García-Fontana, B.; García-Fontana, C. Influence of the Mediterranean Diet on Healthy Aging. Int J Mol Sci. 2023. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Veronese, N.; Di Bella, G.; Cusumano, C.; Parisi, A.; Tagliaferri, F.; et al. Mediterranean diet in the management and prevention of obesity. Exp Gerontol. 2023, 174, 112121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Di Bella, G.; Veronese, N.; Barbagallo, M. Impact of mediterranean diet on chronic non-communicable diseases and longevity. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.B. Diet strategies for promoting healthy aging and longevity: An epidemiological perspective. J Intern Med. 2024, 295, 508–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suardi, C.; Cazzaniga, E.; Graci, S.; Dongo, D.; Palestini, P. Link between viral infections, immune system, inflammation and diet. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 2019, 393, 1958–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keys, A.; Menotti, A.; Aravanis, C.; Blackburn, H.; Djordevic, B.S.; Buzina, R.; et al. The Seven Countries Study: 2,289 Deaths in 15 Years. Prev Med. 1984, 13, 141–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018, 378, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; Gialluisi, A.; Persichillo, M.; Cerletti, C.; et al. Mediterranean diet and mortality in the elderly: A prospective cohort study and a meta-analysis. British Journal of Nutrition. 2018, 120, 841–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, O.M.; Stephan, B.C.M.; Minihane, A.M.; Mathers, J.C.; Siervo, M. Nitric Oxide Boosting Effects of the Mediterranean Diet: A Potential Mechanism of Action. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018, 73, 902–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosti, V.; Bertozzi, B.; Fontana, L. Health Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: Metabolic and Molecular Mechanisms. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018, 73, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, E.J.; Shannon, O.M.; Minihane, A.M.; Adamson, A.; Burns, A.; Hill, T.; et al. NuBrain: UK consortium for optimal nutrition for healthy brain ageing. Nutr Bull. 2020, 45, 223–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, R.; Parramon, D.; García-Ortiz, L.; Rigo, F.; Gómez-Marcos, M.A.; Sempere, I.; et al. Improving interMediAte Risk management. MARK study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2011, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recio-Rodríguez, J.I.; Martín-Cantera, C.; González-Viejo, N.; Gómez-Arranz, A.; Arietaleanizbeascoa, M.S.; Schmolling-Guinovart, Y.; et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone application for improving healthy lifestyles, a randomized clinical trial (EVIDENT II): Study protocol. BMC Public Health. 2014, 14, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Marcos, M.A.; Martínez-Salgado, C.; González-Sarmiento, R.M.A.; Hernández-Rivas, J.; Sánchez-Fernández, P.L.; Recio-Rodríguez, J.I.; et al. Association between different risk factors and vascular accelerated ageing (EVA study): study protocol for a cross-sectional, descriptive observational study. BMJ Open. 2016, 6, e011031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Sánchez, M.; Patino-Alonso, M.C.; Gómez-Sánchez, L.; Recio-Rodríguez, J.I.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, E.; Maderuelo-Fernández, J.A.; et al. Reference values of arterial stiffness parameters and their association with cardiovascular risk factors in the Spanish population. The EVA Study. Revista Española de Cardiología 2020, 73, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Sánchez, M.; Gómez-Sánchez, L.; Patino-Alonso, M.C.; Cunha, P.G.; Recio-Rodríguez, J.I.; Alonso-Domínguez, R.; et al. Vascular aging and its relationship with lifestyles and other risk factors in the general Spanish population: EarlyVascular Ageing Study. J Hypertens 2020, 38, 1110–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, H.; Fitó, M.; Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; et al. A Short screener is valid for assessing mediterranean diet adherence among older spanish men and women. Journal of Nutrition 2011, 141, 1140–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashina, A.; Tomiyama, H.; Takeda, K.; Tsuda, H.; Arai, T.; Hirose, K.; et al. Validity, Reproducibility, and Clinical Significance of Noninvasive Brachial-Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity Measurement. Hypertens Res. 2002, 25, 359–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehm, C.; Allenberg, J.R.; Pittrow, D.; Mahn, M.; Tepohl, G.; Haberl, R.L.; et al. Mortality and vascular morbidity in older adults with asymptomatic versus symptomatic peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 2009, 120, 2053–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancia, G.; Fagard, R.; Narkiewicz, K.; Redon, J.; Zanchetti, A.; Bohm, M.; et al. The task force for the management ofarterial hypertension of the european society ofhypertension (esh) and of the european society of cardiology (esc). J Hypertens. 2013, 31, 1281–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, L.; Wood, A.; Gill, T. Gender differences in adherence and retention in Mediterranean diet interventions with a weight-loss outcome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2024, 25, e13824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berendsen, A.A.M.; van de Rest, O.; Feskens, E.J.M.; Santoro, A.; Ostan, R.; Pietruszka, B.; et al. Changes in dietary Intake and Adherence to the NU-AGE diet following a one-year dietary intervention among European older adults—Results of the NU-AGE randomized trial. Nutrients. 2018, 10, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, A.; Berendsen, A.M.; De Groot, L.C.P.G.M.; Feskens, E.J.M.; Brzozowska, A.; Sicinska, E.; et al. Mediterranean-style diet improves systolic blood pressure and arterial stiffness in older adults: Results of a 1-year european multi-center trial. Hypertension. 2019, 73, 578–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assmann, K.E.; Adjibade, M.; Andreeva, V.A.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Association between Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet at Midlife and Healthy Aging in a Cohort of French Adults. Journals of Gerontology - Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 2018, 73, 347–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcelén-Fraile, M.D.C.; Martín-Baute, M.R.; Ledesma-Cerrato, M.I.; Castellote-Caballero, Y.; González-Martín, A.M.; Hita-Contreras, F.; et al. Effects of a Yoga Program Combined with a Mediterranean Diet on Nutritional Status and Functional Capacity in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients. 2024, 16, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recio-Rodríguez, J.I.; González-Sánchez, S.; Tamayo-Morales, O.; Gómez-Marcos, M.A.; García-Ortiz, L.; Niño-Martín, V.; et al. Changes in lifestyles, cognitive impairment, quality of life and activity day living after combined use of smartphone and smartband technology: a randomized clinical trial (EVIDENT-Age study). BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Global (n=3437) | Women (n=1468) | Men (n=1969) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean Diet | |||||||

| MD (total score) | 5.82±2.03 | 6.03±1.98 | 5.66±2.06 | <0.001 | |||

| Adherence to MD, n (%) | 1650(48.0) | 588(40.1) | 1062(53.9) | <0.001 | |||

| Conventional risk factors | |||||||

| Age, (years) | 60.15±9.55 | 60.09±9.71 | 60.20±9.43 | 0.728 | |||

| SBP, (mmHg) | 133.45±19.53 | 128.72±20.55 | 136.99±17.93 | <0.001 | |||

| DBP, (mmHg) | 82.07±10.97 | 79.64±10.84 | 83.89±10.71 | <0.001 | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2943(85.6) | 1309(89.2) | 1634(83) | <0.001 | |||

| Antihypertensive drugs, n (%) | 1573(45.8) | 654(44.6) | 919(46.7) | 0.217 | |||

| Total cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 216.42±41.11 | 220.54±42.47 | 213.34±39.80 | <0.001 | |||

| LDL cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 133.09±35.18 | 132.53±35.94 | 133.50±34.60 | 0.426 | |||

| HDL cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 52.54±14.50 | 57.27±15.77 | 49.01±12.34 | <0.001 | |||

| Triglycerides, (mg/dl) | 133.38±83.74 | 122.63±68.62 | 141.42±92.67 | <0.001 | |||

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 2487(72.4) | 1076(73.3) | 1411(71.7) | 0.289 | |||

| Lipid–lowering drugs. n (%) | 974(28.3) | 429(29.2) | 545(27.7) | 0.320 | |||

| FPG, (mg/dl) | 101.75±31.82 | 100.24±32.30 | 102.88±31.42 | 0.016 | |||

| HbA1c | 5.94±1.05 | 5.93±1.07 | 5.94±1.04 | 0.680 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 759(22.1) | 306(20.8) | 453(23.0) | 0.131 | |||

| Hypoglycaemic drugs, n (%) | 576(16.8) | 234(15.9) | 342(17.4) | 0.267 | |||

| Weight, kg | 77.52±14.65 | 70.20±13.31 | 82.98±13.15 | <0.001 | |||

| Height, cm | 164.59±9.46 | 157.11±6.67 | 170.17±7.08 | <0.001 | |||

| BMI, (kg/m2) | 28.56±4.53 | 28.47±5.30 | 28.62±3.86 | 0.367 | |||

| WC, cm | 98.65±12.07 | 94.33±12.91 | 101.87±10.30 | <0.001 | |||

| Obesity, n (%) | 1086(31.6) | 495(33.7) | 591(30.0) | 0.021 | |||

| Arterial stiffness | |||||||

| ba-PWV, m/second | 14.38±2.71 | 14.24±2.89 | 14.49±2.56 | 0.007 | |||

| HVA(n=475) | NVA(n=1559) | EVA(n=1403) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean Diet | ||||||

| MD (total score) | 6.20±2.10 | 5.98±2.02 | 5.51±1.99 | <0.001 | ||

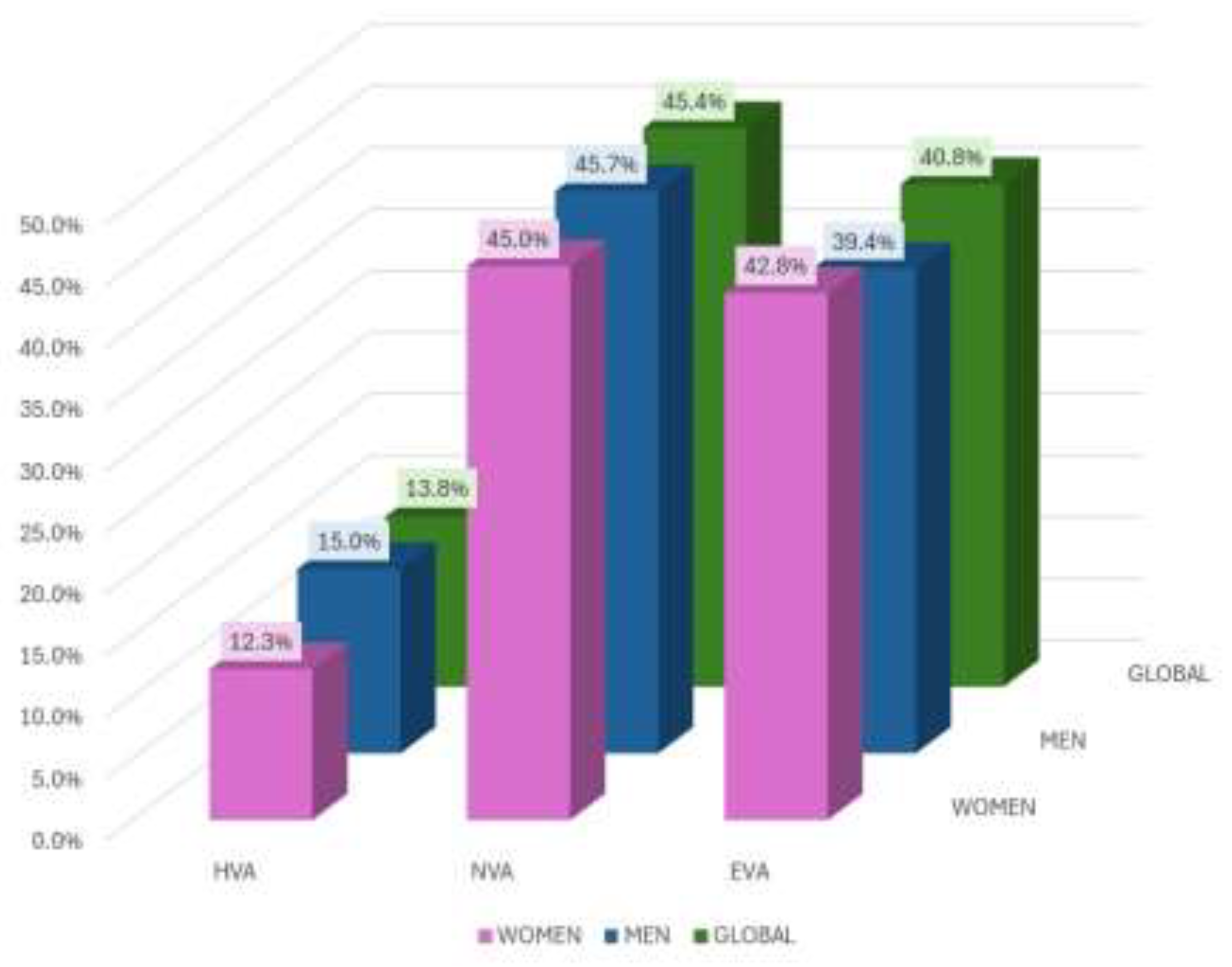

| Adherence to MD, n (%) | 267(56.2) | 805(51.6) | 578(41.2) | <0.001 | ||

| Conventional risk factors | ||||||

| Age, (years) | 59.39±10.34 | 60.33±9.78 | 60.22±8.98 | 0.207 | ||

| SBP, (mmHg) | 121.03±15.38 | 129.98±18.57 | 141.52±18.45 | <0.001 | ||

| DBP, (mmHg) | 76.27±10.19 | 80.23±10.03 | 86.08±10.80 | <0.001 | ||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 455(95.8) | 1382(88.6) | 1106(78.8) | <0.001 | ||

| Antihypertensive drugs, n (%) | 161(33.9) | 708(45.4) | 704(50.2) | <0.001 | ||

| Total cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 211.92±36.34 | 213.49±41.34 | 221.18±41.91 | <0.001 | ||

| LDL cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 131.25±31.60 | 131.13±35.51 | 135.90±35.80 | <0.001 | ||

| HDL cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 54.16±13.52 | 52.99±15.00 | 51.49±14.17 | <0.001 | ||

| Triglycerides, (mg/dl) | 112.48±55.29 | 128.77±77.38 | 145.61±95.84 | <0.001 | ||

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 286(60.2) | 1098(70.4) | 1103(78.6) | <0.001 | ||

| Lipid–lowering drugs. n (%) | 98(20.6) | 458(29.4) | 418(28.8) | <0.001 | ||

| FPG, (mg/dl) | 88.23±11.41 | 99.13±26.61 | 109.06±39.17 | <0.001 | ||

| HbA1c | 5.46±0.36 | 5.86±0.90 | 6.18±1.27 | <0.001 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0(0.0) | 340(21.8) | 419(29.9) | <0.001 | ||

| Hypoglycaemic drugs, n (%) | 0(0.0) | 256(16.4) | 320(22.8) | <0.001 | ||

| Weight, kg | 77.99±14.49 | 77.13±14.86 | 77.93±14.47 | 0.356 | ||

| Height, cm | 166.71±9.44 | 164.64±9.38 | 163.82±9.45 | <0.001 | ||

| BMI, (kg/m2) | 28.02±4.40 | 28.40±4.74 | 28.90±4.31 | <0.001 | ||

| WC, cm | 96.86±11.93 | 98.14±12.56 | 99.83±11.44 | <0.001 | ||

| Obesity, n (%) | 123(25.9) | 484(31.0) | 479(34.1) | <0.001 | ||

| Arterial stiffness | ||||||

| ba-PWV, m/second | 11.60±1.34 | 13.45±1.69 | 16.36±2.57 | <0.001 | ||

| HVA(n=475) | NVA(n=1559) | EVA(n=1403) | p value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n=295) | Women (n=180) | Men (n=899) | Women (n=660) | Men (n=775) | Women (n=628) | Men | Women | ||

| Mediterranean Diet | |||||||||

| MD (total score) | 5.92±2.11 | 6.68±2.01 | 5.85±2.07 | 6.16±1.93 | 5.33±1.99 | 5.72±1.97 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Adherence to MD, n (%) | 170(57.6) | 97(53.9) | 524(58.3) | 281(42.6) | 368(47.5) | 210(43.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Conventional risk factors | |||||||||

| Age, (years) | 60.28±9.30 | 57.93±11.73 | 60.34±9.60 | 60.31±10.04 | 60.02±9.29 | 60.47±8.59 | 0.771 | 0.025 | |

| SBP, (mmHg) | 125.70±14.16 | 113.38±14.23 | 133.37±15.63 | 125.37±21.11 | 145.48±17.95 | 136.63±17.90 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| DBP, (mmHg) | 78.46±9.14 | 72.68±10.80 | 82.06±9.45 | 77.75±10.27 | 88.06±11.13 | 83.63±9.85 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 276(93.6) | 179(99.4) | 781(86.9) | 601(91.1) | 577(74.5) | 529(84.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Antihypertensive drugs, n (%) | 107(36.3) | 54(30.0) | 427(47.5) | 281(42.6) | 385(49.7) | 319(50.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Total cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 214.11±35.88 | 208.32±36.90 | 209.48±40.55 | 218.96±41.82 | 217.52±39.95 | 225.71±43.83 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| LDL cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 135.43±31.75 | 124.35±30.19 | 131.07±34.89 | 131.20±36.36 | 135.60±35.19 | 136.26±36.56 | 0.018 | <0.001 | |

| HDL cholesterol, (mg/dl) | 50.66±11.29 | 59.95±14.87 | 48.69±12.01 | 58.85±16.61 | 48.75±13.05 | 54.85±14.78 | 0.028 | <0.001 | |

| Triglycerides, (mg/dl) | 122.33±60.43 | 96.39±40.98 | 135.16±78.53 | 120.09±79.97 | 156.03±113.67 | 132.84±65.76 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 187(63.4) | 99(55.0) | 639(71.1) | 459(69.5) | 585(75.5) | 518(82.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Lipid–lowering drugs. n (%) | 64(21.7) | 34(18.9) | 266(29.6) | 192(29.1) | 215(27.7) | 203(32.3) | 0.031 | 0.002 | |

| FPG, (mg/dl) | 90.99±11.13 | 85.29±10.99 | 100.86±26.26 | 96.78±26.94 | 109.78±39.49 | 108.17±38.79 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| HbA1c | 5.49±0.35 | 5.42±0.38 | 5.91±0.93 | 5.79±0.84 | 6.15±1.24 | 6.22±1.30 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 220(24.5) | 120(18.2) | 233(30.1) | 186(29.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Hypoglycaemic drugs, n (%) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 165(18.4) | 91(13.8) | 177(22.8) | 143(22.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Weight, kg | 82.81±13.32 | 70.09±12.78 | 82.67±13.06 | 69.59±13.82 | 83.40±13.20 | 70.87±12.90 | 0.505 | 0.228 | |

| Height, cm | 171.74±6.98 | 158.47±6.78 | 170.11±7.02 | 157.19±6.65 | 169.64±7.11 | 156.64±6.61 | <0.001 | 0.006 | |

| BMI, (kg/m2) | 28.05±3.84 | 27.98±5.20 | 28.54±3.93 | 28.22±5.65 | 28.92±3.76 | 28.88±4.91 | 0.003 | 0.028 | |

| WC, cm | 99.98±10.52 | 91.79±12.37 | 101.77±10.71 | 93.18±13.22 | 102.70±9.62 | 96.26±12.47 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Obesity, n (%) | 71(24.1) | 52(28.9) | 272(30.3) | 212(32.1) | 248(32.0) | 231(36.8) | 0.040 | 0.072 | |

| Arterial stiffness | |||||||||

| ba-PWV, m/second | 11.91±1.17 | 11.08±1.45 | 13.59±1.43 | 13.25±1.99 | 16.52±2.49 | 16.18±2.67 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Global | OR | (CI 95%) | p | |

| MD | ||||

| HVA vs NVA | 1.751 | (1.411 to 2.174) | <0.001 | |

| HVA vs EVA | 1.501 | (1.295 to 1.740) | <0.001 | |

| Women | ||||

| MD | ||||

| HVA vs NVA | 2.055 | (1.456 to 2.901) | <0.001 | |

| HVA vs EVA | 1.413 | (1.124 to 1.776) | 0.003 | |

| Men | ||||

| MD | ||||

| HVA vs NVA | 1.551 | (1.175 to 2.047) | 0.002 | |

| HVA vs EVA | 1.549 | (1.275 to 1.882) | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).