Introduction

The latest global cancer data released in 2024 shows that in 2022 [

1],there were 510,500 new cases of pancreatic cancer worldwide, with 467,000 deaths. The fatality rate ranks sixth among all malignant tumors. Asia contributed the most to the global increase in confirmed cases (47.1%) and cancer-related deaths (48.1%).

The human development index (HDI), calculated based on life expectancy, educational level and quality of life, is used to evaluate the development status of a country. Higher HDI is associated with an increased incidence and mortality of pancreatic cancer [

2]. In the United States, pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of death among all cancers [

3] and is expected to become the second leading cause of death by 2030[

4]. In EU countries, the incidence of pancreatic cancer ranks 8th among all malignant tumors, and the cancer-related mortality rate ranks 6th. By 2040, the total incidence of pancreatic cancer is expected to increase by 30%[

5] .

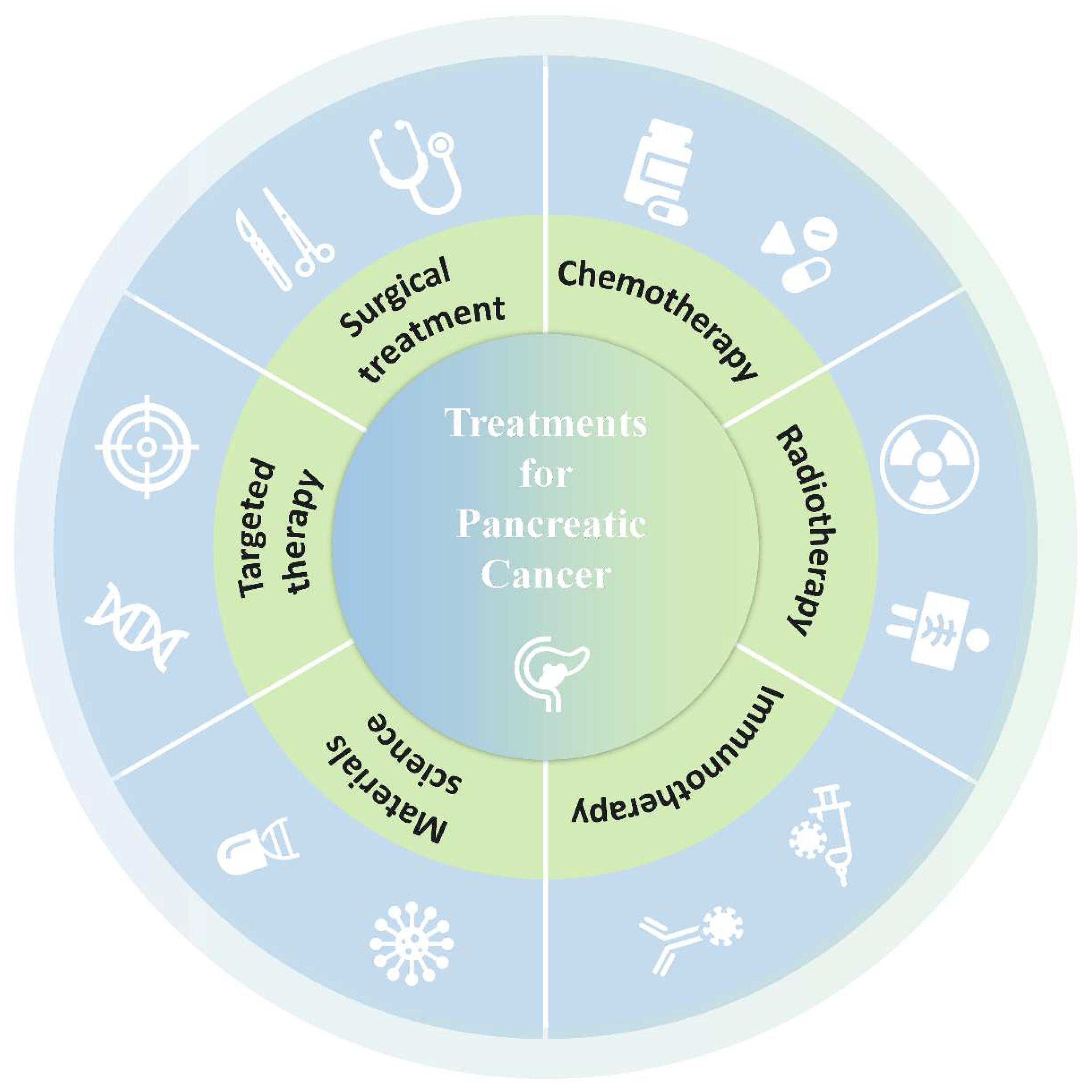

Although the prognosis of pancreatic cancer is poor and our understanding of pancreatic cancer is limited, the updated surgical methods have improved the quality of treatment. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy have also become important adjunctive means for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. With the in-depth study of tumor genomics, targeted therapy and immunotherapy bring new hope to patients. In this review, we will discuss the current treatment methods for pancreatic cancer and the evidence behind them(

Figure 1).

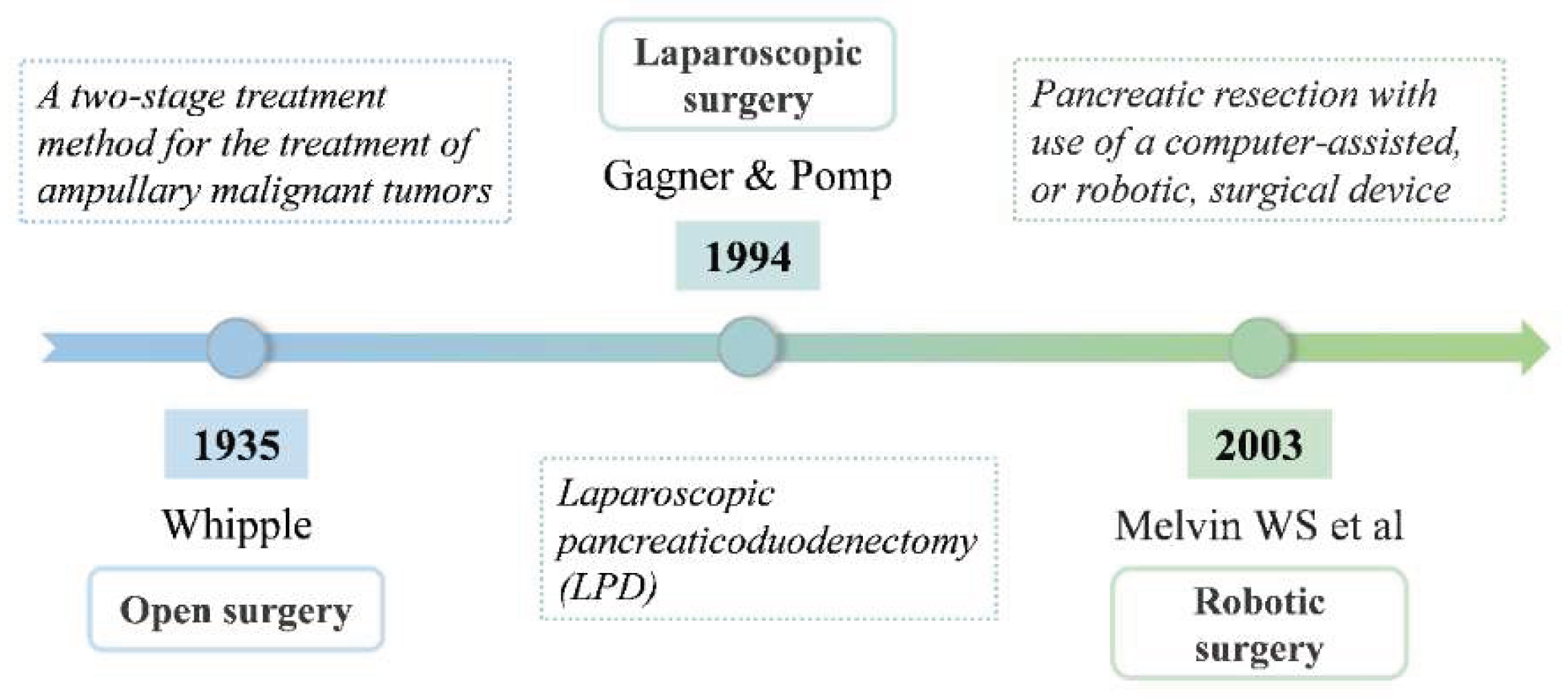

1. Surgical treatment

This section mainly covers open surgery, laparoscopic surgery and robotic surgery for the treatment of pancreatic cancer(

Figure 2).

1.1. Open surgery

The choice of surgical plan for pancreatic cancer is mainly based on the specific location of the tumor in the pancreas. For lesions located in the distal pancreas, distal pancreatectomy is usually performed. However, for malignant tumors in the head of the pancreas, pancreatectomy is required to achieve complete clearance. Whipple first elaborated a two-stage treatment method for the treatment of ampullary malignant tumors in his article published in 1935, and since then established the basis for the complex surgical operation of Pancreaticoduodenectomy [

6].

Early reports of post-operative mortality were as high as 30-45%[

7,

8,

9]. A study of 400 patients with stage I or II pancreatic head cancer randomized them to standard pancreaticoduodenectomy(SPD) or extensive pancreaticoduodenectomy (EPD), which found that patients in the EPD group had lower postoperative mesenteric lymph node recurrence rate and longer disease progression-free survival time[

10]. However, Wang observed 170 patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy with different degrees of lymph node dissection (including 81 with standard dissection and 89 with extended dissection) and showed that more extensive lymph node dissection did not significantly improve the long-term survival of patients[

9]. Instead, it may reduce the odds of overall survival within a year.Today, mortality has vastly improved and is now at an acceptable 1-3% in big high-volume centers [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Nevertheless, short-term morbidity remains a significant issue, such as pancreatic fistulas(PF) and delayed gastric emptying(DGE)[

7]. Some retrospective analyses suggest that a long operation time and intraoperative blood loss greater than 1 liter may increase the risk of PF[

13], however, some large-sample studies have also shown that the length of the operation and the intraoperative blood loss have no significant correlation with the occurrence of PF[

14]. Some scholars' studies have shown that the occurrence of postoperative complications such as PF, peritoneal effusion, abdominal abscess, etc., and the mortality rate in patients without prophylactic placement of abdominal drainage tubes after pancreaticoduodenal surgery are significantly increased [

15]. Multiple meta-analyses have reported that patients without preventive drainage have a higher mortality rate, and patients with a low risk of PF may benefit from the placement of intra-abdominal drainage tubes [

16]. A meta-analysis by Hanna et al on surgical technique found antecolic position of the gastrojejunostomy limb as well as subtotal stomach preserving PD to be associated with lower incidence of DGE [

17]. Overall, PF and DGE after PD remains a challenging issue in need of further study.

1.2. Laparoscopic surgery

In 1994, Gagner and Pomp first reported Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy (LPD) [

18]. Compared with Open pancreaticoduodenectomy (OPD), LPD has a longer learning curve, a longer operation time, and a higher risk of potential complications. However, a study of 146 patients with LPD found an overall mortality rate of only 1.3%, a complication rate of 16%, and an average blood loss of 143 ml [

19]. With the increasing experience of surgeons, the application of LPD has been expanded to cover complex situations such as intestinal vascular resection and reconstruction [

20,

21], and the incidence of complications has decreased. In a randomized clinical trial [

22], a comparative analysis of perioperative conditions and outcomes in 66 patients (34 treated with LPD and 32 with OPD) showed that: Compared with OPD, LPD showed advantages in shortening the length of hospital stay (13.5 days vs 17 days, respectively) and reducing the burden of postoperative complications.

In addition, several meta-analyses[

23,

24] compared 9144 patients who underwent LPD with 15,278 patients who underwent OPD. The study found that there was no significant difference in operative mortality and pancreatic fistula rate between the two groups, but the LPD group performed better in achieving R0 resection and lymph node dissection.Compared with OPD, although the safety of LPD is equivalent, it significantly reduces the amount of intraoperative blood loss, the degree of trauma and the occurrence of postoperative complications [

25]. In addition, this method requires surgeons to perform delicate operations in a limited space, which can improve the surgical accuracy to a certain extent. However, due to the complex operation process, difficult anatomy and high requirements of LPD, as well as the unique leverage effect of laparoscopic instruments, inbendability and the unnatural body posture of the operator, LPD may have a negative impact on the surgical results [

26]. In some cases, these challenges may lead to the difficulty of performing precise procedures or the inability of assistants to provide a clear field of view, thereby increasing the risk of surgery and threatening the safety of patients, which may lead to the loss of the original advantages of minimally invasive, precision, and safety. With the advancement of technology, LPD has become one of the standard treatments in some professional medical institutions, which not only improves the treatment effect of pancreatic tumors, but also allows more patients to benefit from it.

1.3. Robotic surgery

With the clinical application of robotic surgical system, the surgical treatment of pancreatic cancer has ushered in a new development opportunity. Robot-assisted Pancreaticoduodenectomy (RPD) is one of the new technologies, which provides a new treatment option for patients with pancreatic cancer [

27]. With its 3D high-definition vision, bionic robotic arm and intuitive motion control system, Da Vinci surgical system not only makes the surgical process more minimally invasive and accurate [

28], but also improves the surgeon's operating posture and makes it more ergonomic, thus improving the surgical effect to a certain extent. However, due to the limitation of technology and equipment conditions, RPD is currently mainly implemented in hepatobiliary and pancreatic specialties and large medical institutions [

29]. In 2016, Zureikat conducted a multicenter retrospective study comparing the perioperative outcomes of 211 patients treated with RPD and 817 patients treated with traditional open surgery [

30]. The study showed no significant differences in mortality, length of hospital stay, or readmission rates, while RPD has lower blood loss and fewer serious complications, while the operation time is relatively prolonged.

In particular, it is important to point out that the learning period is significantly shorter in RPD compared to LPD. Studies have found that approximately 20 to 80 operations are required to train a surgeon who can master the technique of RPD proficiently [

31], which is only about half of the number of cases required to learn LPD. This is further confirmed by the study of Boone, who suggested that the learning curve of RPD skills is roughly located around 80 cases, which is significantly lower than the requirements of LPD[

32].

1.4. Irreversible electroporation

As a non-thermal ablation technique and an emerging tumor ablation method, Irreversible electroporation(IRE) induces local cell death by generating a high-voltage short pulsed electric field that creates tiny pores in the cell membrane [

33]. The ability of this technique to achieve tumor tissue destruction without causing damage to adjacent blood vessels or common bile duct has been regarded as a potential palliative treatment option for unresectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer [

34,

35].

Since 2009, Martin[

34] took the lead in introducing IRE technology into the clinical treatment of pancreatic cancer, creating a new chapter of IRE for the treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Meta-analysis shows that IRE is relatively safe for the treatment of pancreatic cancer and can benefit patients[

36]. In 2018, a study in Japan included 8 patients who received open abdominal IRE and percutaneous IRE respectively. The median survival period after the operation was 17.5 months[

37]. Subsequently, Denmark conducted 40 IRE operations on 33 patients in 2019, with a median survival period of 18.5 months. These several studies all show that nanoknife can prolong the survival time of patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer[

38]. He et al. holds the view that IRE induced local immunomodulation by increasing specific T cells infiltration. Through enhancing specific immune memory, IRE not only led a complete tumor regression in suit, but also induced abscopal effect, suppressing the growth of the latent lesions[

39].In recent years, many experts have begun to pay attention to the potential benefits of IRE combined with chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy for patients with locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer. A Phase II study in 2025 shows that combined beta-glucan with IRE-ablated tumor cells elicited a potent trained response and augmented antitumor functionality at 12 months post-IRE, which translated into an improved overall survival[

40]. In addition, results suggest that IRE is a promising approach to potentiate the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade in pancreatic cancer [

41]. Based on this, IRE combined with other treatment methods may become a direction for future exploration.

2. Chemotherapy

2.1. Palliative chemotherapy

Due to the lack of specific clinical manifestations in the early stage of the disease and the lack of effective early screening methods, most patients have already progressed to advanced stages when diagnosed, resulting in only about 15% to 20% of cases suitable for surgical intervention.Therefore, systemic chemotherapy has become the main or even the only treatment strategy for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. The commonly used chemotherapy regimens for pancreatic cancer include modified FOLFIRINOX (including 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan and oxaliplatin) combination therapy, gemcitabine alone or in combination with other drugs, etc. Studies [

42] showed that the median survival time of patients treated with FOLFIRINOX regimen was 11.1 months and 6.8 months, respectively, compared with those treated with standard dose of gemcitabine alone. According to other reports [

43], the overall survival time and progression-free survival time of paclitaxel plus gemcitabine combination treatment group were prolonged to 8.5 months and 5.5 months, respectively, when compared with gemcitabine alone treatment group(6.7 months and 3.7 months). Although there is evidence that the modified FOLFIRINOX regimen has better efficacy than gemcitabine, the modified FOLFIRINOX regimen is also associated with a higher risk of toxic effect. Therefore, in actual clinical practice, gemcitabine remains one of the most widely used chemotherapy agents. Therefore, gemcitabine alone is considered to be a more appropriate treatment option for pancreatic cancer patients with poor physical condition.

2.2. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy

For patients with pancreatic cancer, adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended after radical surgery and in the absence of relevant contraindications. Gemcitabine or fluorouracil-based drugs (such as 5-FU, capecitabine) are widely used. For patients in better condition, combination therapy, such as gemcitabine plus capecitabine or mFOLFIRINOX, can also be used. It has been shown that the use of a single agent as adjuvant chemotherapy can confer a survival advantage for patients [

44,

45,

46]. Notably, the combination of gemcitabine and capecitabine significantly prolonged the median survival compared with gemcitabine alone (28 months vs 25.5 months) [

46]. In addition, studies comparing the modified version of FOLFFIRINOx (without irinotecan and 5-FU) with gemcitabine [

47] showed that the modified regimen was superior in improving median survival (54.4 vs 35 months) but was also associated with higher toxic effects. Thus, gemcitabine alone or with capecitabine may be an appropriate alternative for patients who are unable to tolerate the side effects of mFOLFIRINOX.

2.3. Preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy

For patients who are resectable or nearly resectable, the main goal of neoadjuvant/conversion therapy is to improve the R0 resection rate, thereby prolonging the disease-free survival and overall survival of patients. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend neoadjuvant therapy for borderline or locally advanced disease. FUFIRINOX or gemcitabine with nab-paclitaxel [

48]has been proposed as the preferred option. Compared with the method of starting chemotherapy after surgery, neoadjuvant chemotherapy can make drugs act on the targeted area more efficiently without interfering the blood supply of the tumor, which is helpful to deal with the problem of micro-metastasis that may occur during the subsequent surgery[

49]. In addition, it has been observed in many types of cancer that patients show better tolerance to neoadjuvant chemotherapy performed before surgery compared with postoperative chemotherapy, which also indirectly contributes to the improvement of treatment efficacy [

50,

51].

In recent years, a number of studies on patients with borderline resectable or locally advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57] and patients with other types of resectable cancer [

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]have shown that regardless of the neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen, the tumor resectability rate, R0 resection rate and median survival time of patients can be improved. In particular, in terms of the management of resectable cancer, the study by Lutfi [

64] compared the data of patients with early-stage pancreatic cancer (stage I/II) who underwent surgery combined with any form and timing of chemotherapy with those who did not receive chemotherapy, which showed that the addition of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, adjuvant chemotherapy, or a combination of the two in addition to surgery alone, the combination of the two was effective. It can significantly prolong the survival time of patients. Furthermore, a meta-analysis by Versteijne involving 3484 patients with resectable or borderline resectable tumors who received any form of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, showed that, as compared with those who did not receive neoadjuvant therapy, the proportion of patients with resectable or borderline resectable tumors who did not receive neoadjuvant therapy was significantly lower. Patients receiving this treatment had longer median survival (18.8 months vs 14.8 months) [

65].

3. Radiotherapy

3.1. Adjuvant radiotherapy

The core mechanism of radiotherapy is the use of radiation sources such as X-rays, gamma rays and high-energy electron beams to irradiate cancer cells. By triggering ionization and excitation effects, this process can destroy the DNA structure of cancer cells, deprives them of their ability to reproduce, and ultimately achieve the goal of eliminating or inhibiting tumor growth.

A randomized controlled trial of patients with no residual disease at the margin after surgery for pancreatic cancer showed that in the presence of an adjuvant chemoradiotherapy regimen (40Gy in fractions and weekly 5-fluorouracil), Overall survival was significantly better than in controls who did not receive this therapy (median survival, 20 and 11 months, respectively) [

66]. However, there have been reports that chemotherapy may have a negative impact on survival [

67]. Based on the available evidence, the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) recommended in its guidelines that fractionated adjuvant radiotherapy should be considered for cases with high-risk features such as lymph node involvement or positive surgical margins[

68].

3.2. Neoadjuvant radiotherapy

Since the 1990s, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group of the United States has been committed to exploring neoadjuvant radiotherapy methods for pancreatic cancer [

69]. Despite earlier concerns that neoadjuvant radiotherapy may increase the risk of complications such as bleeding during surgery, recent studies have shown no significant increase in the incidence of postoperative complications and mortality in patients receiving this treatment [

70]. Although local radiotherapy has been shown to help shrink tumor volume and reduce its invasive potential for surrounding tissues, there is controversy over whether radiotherapy should be added to systemic chemotherapy as part of a comprehensive treatment regimen after pancreatic cancer surgery.

In order to investigate the application effect of combined radiotherapy before surgery, many studies have compared the difference between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and direct surgery. A 2019 phase II trial showed that preoperative chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX combined with radiotherapy resulted in downstaging and a 61% R0 resection rate in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer [

71]. A multicenter, randomized, phase III trial conducted in the Netherlands (PEROPANC cohort) showed that preoperative chemoradiotherapy in patients with resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer significantly increased the rate of R0 resection (71% vs 40%), although median overall survival was improved (15.7 vs 14.3 months, P=0.096). But this difference did not reach statistical significance. In addition, this method also reduced the incidence of positive lymph nodes, nerve invasion and venous invasion in the surgical area [

72], and five-year survival was also significantly improved in long-term follow-up (20.5% vs 6.5%) [

73]. However, earlier studies reported that although preoperative combined radiotherapy reduced the risk of local recurrence, it did not affect overall survival [

74]. At the same time, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone may be more effective in promoting tumor shrinkage [

75]. For patients with resectable pancreatic cancer, achieving R0 resection is a critical prognostic factor [

76]. In view of the high incidence of micrometastasis at diagnosis, it is particularly important to improve the probability of R0 resection by neoadjuvant radiotherapy.

In view of the lack of sufficient evidence-based medical evidence, the specific efficacy of neoadjuvant radiotherapy in RPC has not been fully determined. Early efforts have focused on evaluating the safety and efficacy of this therapy. The phase I/II clinical trials conducted by Talamonti [

77] and Evans [

78] have shown that preoperative radiotherapy is well tolerated and safe. In addition, the high negative resection margin rate and lymph node dissection rate also show its significant treatment effect. In 2011, Artinyan [

79] indicated that neoadjuvant radiotherapy may be a key prognostic factor after a retrospective analysis of the data of 458 patients who underwent RPC surgery between 1987 and 2006. The study by Cloyd [

80]found that patients who received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) had a higher rate of R0 resection and a lower risk of postoperative local recurrence and lymph node metastasis than those who received chemotherapy alone. For borderline resectable pancreatic cancer (BRPC), neoadjuvant radiotherapy can promote tumor downgrading and increase the likelihood of successful surgery.

A prospective study [

81] showed that among 15 patients who received neoadjuvant CRT, the surgical resection rate was 60%, all patients had negative margins, and 2 of them achieved pathologic complete response (pCR). The median Overall Survival (OS) of the patients in this study was 30 months, and no grade ≥3 adverse events were observed. Another prospective multicenter study named A021101 [

57], which recruited 22 BRPC patients, showed an overall surgical resection rate of 68%, of which 14 patients achieved R0 resection. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that neoadjuvant radiotherapy can reduce tumor stage and improve surgical resectability, but whether it can significantly improve median survival is still controversial. A subgroup analysis of the PREOPANC phase III study [

72] indicated that BRPC patients treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy showed a longer median survival time compared with going straight to surgery. Nagakawa 's analysis of 884 BRPC patients showed that although the neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy group was superior to the chemotherapy alone group in terms of lymph node positive rate, surgical resection rate, and local recurrence rate, there was no statistically significant difference in median survival between the two groups[

82]. Overall, neoadjuvant/conversion chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy offers new hope for patients with pancreatic cancer, especially in BRPC. With the continuous deepening of related research and the advancement of technology, the combined treatment strategy is expected to bring better treatment outcomes to more patients.

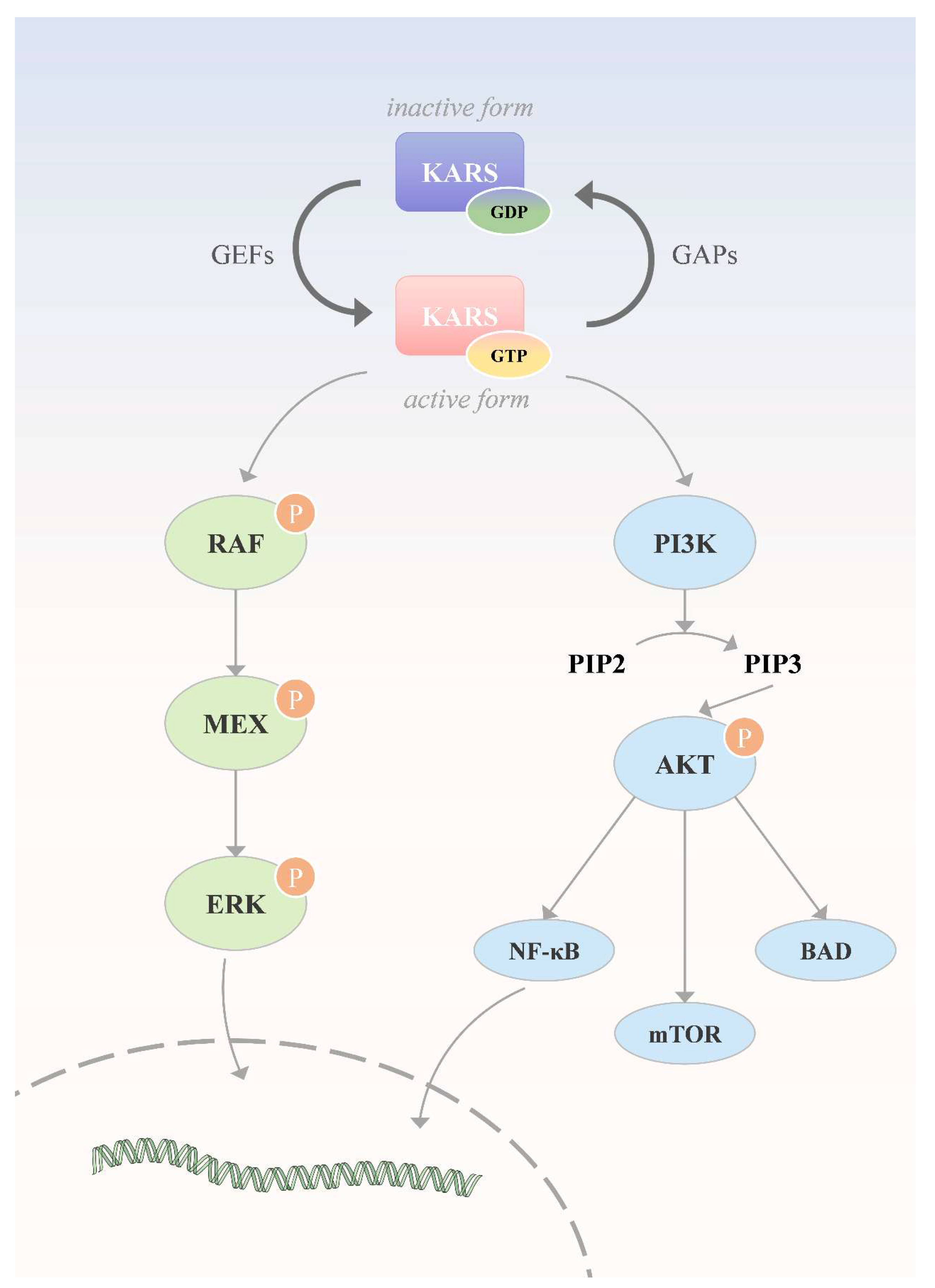

4. Targeted therapy

As early as 2008, studies revealed 12 core signaling pathways in pancreatic cancer [

83]. Subsequently, with the help of advanced sequencing technology, scientists further confirmed the frequent gene mutations in this disease, including several key drivers such as KRAS, TP53, CDKN2A and SMAD4 [

84]. Meanwhile, research on targeted therapies in response to these findings continues to advance(

Figure 3).

4.1. Targeting KRAS mutations

KRAS mutations have been observed in approximately 90% of patients with pancreatic cancer, and these mutations are mainly concentrated in three specific codons G12, G13 and Q61, which can activate the downstream RAF-MEK-ERK pathway and PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway. In 2013, Ostrem [

85] developed an inhibitor specifically targeting the KRAS G12C variant. Then, in a study led by Strickler [

86], the drug, sotorasib, was used in a population of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer harboring the KRAS G12C mutation who were receiving second-line or higher therapy. The study, involving 38 participants, showed an objective response rate of 21%, a median progression-free survival of 4.0 months, and a median overall survival of 6.9 months.

Awad [

87] explored the mechanisms of resistance to KRAS G12C inhibitors in clinical use, noting that cancer cells treated with this class of drugs may develop other forms of KRAS mutations to counter the effects of sotorasib or adalasib. In April 2024, Kenneth P. Olive Mallika Singh published his research results on the strong anticancer potential of RMC-7977 in the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma model in Nature [

88]. As a reversible Tri-complex inhibitor, RMC-7977 can widely act on KRAS, NRAS and multiple RAS variants in mutant and normal states. In addition, significant progress has been made in the research and development of pan-inhibitors and pan-degraders designed for KRAS in recent years [

89,

90].

4.2. Targeting upstream of KRAS

In addition to drugs that act directly on KRAS mutant proteins, numerous therapies targeting molecules in its upstream and downstream signaling pathways are under clinical investigation to enhance anticancer efficacy and overcome resistance. By inhibiting key regulators upstream of KRAS, For example, Srchomology-2domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2, SHP2) and Son of sevenless homolog 1 (SOS1), allowing efficient control of the activity of a wide range of KRAS variants. At present, several SHP2 inhibitors are under development, including RMC-4630 (NCT03634982), TNO155(NCT04330664) and JAB-3312(NCT05288205). In addition, BI-1701963, as a SOS1 inhibitor [

91], has also entered phase I/II clinical trials (NCT04111458). However, the results obtained by using these novel inhibitors alone are not ideal, and all of them fail to achieve the expected therapeutic goals. Therefore, SHP2 inhibitors and SOS1 inhibitors may be more considered as adjunctive therapies in combination with other therapies in the future.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a transmembrane glycoprotein, is overexpressed in most cases of pancreatic cancer. Anti-egfr drugs inhibit tumor cell growth and survival by preventing ligand-induced activation of EGFR tyrosine kinase [

92]. At present, such drugs mainly include Tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) and Monoclonal antibody (mAb) against EGFR. However, there are still many obstacles in the process of using EGFR-TKIs against pancreatic cancer, such as improving drug tolerance, enhancing disease control effect, and identifying which patients are most likely to benefit from EGFR-Tkis.

4.3. Target KRAS downstream

Signaling pathways downstream of KRAS include Mitogen activated protein kinases, MAPKs) pathway (RAF-MEK-ERK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway (PAM pathway). In tumors caused by KRAS gene mutation, RAF, as a serine/threonine-specific protein kinase, plays an indispensable role in the process of cell signaling and its resistance mechanism to anti-therapy [

93].

Currently, several RAF inhibitors, such as sorafenib and dabrafenib, have been approved for the treatment of various solid tumors. In 2024, NCCN guidelines recommend dabraafenib in combination with trametinib as first-line therapy for patients with BRAF V600E mutation-positive metastatic pancreatic cancer. ERK, as the final kinase in the MAPK pathway, contains two types: ERK1 and ERK2. Through phosphorylation, ERK can activate or inhibit a variety of target proteins, thereby blocking the downstream signaling of KRAS and inhibiting the proliferation of tumor cells [

94]. Inhibitors of ERK mainly include reversible ERK1/2 inhibitors, irreversible covalent ERK1/2 inhibitors and heterogeneous ERK1/2 inhibitors. At present, several ERK inhibitors, including GDC-0994[

95] and Ulixertinib (BVD-523) [

96], are in the clinical research stage. However, no drug has been officially approved by the FDA to date.

KRAS promotes tumor development by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Inhibition of this pathway by microrna can effectively regulate the malignant progression of tumors. At present, a variety of inhibitors targeting this pathway, such as PI3K inhibitors, AKT inhibitors and MTOR-specific inhibitors (such as everolimus and temsirolimus), have been widely used and intensively studied in the treatment of different types of cancer.

4.4. Targeting other genes

In addition to the classic KRAS therapy, studies targeting other key genes such as TP53, SMAD4, and CDKN2A are under way. Among them, TP53, as an important tumor suppressor, is usually expressed at low levels in healthy cells, while its activity is significantly enhanced in cancerous tissues. Literature reports show that TP53 gene mutations can be detected in about 70% of pancreatic cancer cases [

97]. In addition, more than one-fifth of pancreatic cancer patients carry SMAD4 gene variants or deletions. This gene is responsible for encoding an intracellular signaling molecule shared by transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) superfamily [

98].

As a tumor suppressor gene, CDKN2A mutation plays a key role in the development of pancreatic cancer. According to statistics, somatic mutations of this gene can be found in about 95% of pancreatic cancer patients. In addition, the presence of this mutation has been observed in some cases with familial inheritance tendency. Theoretically, targeted therapies designed for these specific genes have potential effectiveness, but most of the relevant studies at home and abroad are still in phase II or III clinical trials[

99,

100].

In addition to directly targeting specific gene therapy, anti-interstitial drugs acting on the tumor microenvironment, agents inhibiting angiogenesis and drugs regulating tumor metabolism have also attracted much attention in the field of targeted therapy of pancreatic cancer.

5. Immunotherapy

The core of immunotherapy is to regulate the immune response by using specific immune cells or drugs to improve the ability to recognize and attack cancer cells by activating or enhancing the individual's own immune system to fight cancer. In the field of cancer treatment, a variety of immunotherapies have shown different clinical effects, including the research and application of monoclonal antibodies, the development of tumor vaccines, and the development of Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy.

5.1. Monoclonal antibody therapy

Monoclonal antibody therapy is designed to inhibit the growth and spread of tumor cells through the use of artificially generated specific antibodies.

In the field of pancreatic cancer treatment, immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) is the most widely used monoclonal antibody therapy. Pembrolizumab and Ipilimumab have been included in the treatment of pancreatic cancer [

101]. Although immune checkpoint inhibitors have shown remarkable efficacy in a variety of advanced cancers, However, most pancreatic cancer shows a low response rate to Programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) or Programmed cell death-ligand 1(PD-L1) targeted therapy due to their immunological "cold" characteristics [

102]. As a result, these monoclonal antibody therapies have been found to be effective in only a small proportion of patients in clinical trials. The reasons for this phenomenon may include that the pancreatic tumor microenvironment is rich in immunosuppressive cells, such as myeloid suppressor cells, regulatory T cells and tumor-associated macrophages [

103]. In addition, insufficient expression of human leukocyte antigen is also considered to be one of the key factors limiting the efficacy of ICI and other drugs [

104].

At present, the immunosuppressive microenvironment of pancreatic cancer has brought many obstacles to the development of treatment plans. The existing anti-cancer therapies are still very limited in improving the prognosis of patients.

5.2. Tumor vaccine therapy

As an immunotherapy, tumor vaccines activate the body's immune response by introducing external tumor antigens. Currently, vaccines have been approved for lung cancer, prostate cancer and melanoma. In contrast, vaccines for the treatment of pancreatic cancer are still under development [

105].

Whole-cell vaccines are a type of therapy that uses autologous or allogeneic tumor cells that have been irradiated or otherwise treated to fight cancer. This treatment is designed to inhibit the proliferative capacity of the tumor cells while preserving as much of their immunogenic characteristics as possible to stimulate an immune response against the tumor in the patient. Because whole-cell vaccines can present multiple tumor antigens to the body, they can help to reduce the immune escape caused by the loss of specific antigens and improve the effectiveness of the immune response to varying degrees. A clinical trial (NCT02451982) that investigated the efficacy of combining a whole-cell vaccine with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab and the CD137 agonist urelumab after surgical resection of pancreatic cancer showed that this combination significantly enhanced the efficacy of the whole-cell vaccine. It has improved the prognosis of patients [

106].

Dendritic cells (DCs) play a key role in triggering antigen-induced immune responses due to their excellent antigen-presenting function [

107]. When these cells are endowed with a specific antigen in vitro, as part of a tumor vaccine, they can promote the generation of highly specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes against the antigen in vivo, so as to precisely attack cancerous tissues [

108]. A study based on a mouse model showed that mice inoculated with DCs in advance showed lower tumor development rates and longer life span compared to untreated controls, demonstrating significantly enhanced anticancer efficacy[

109].

According to the central dogma, the sequence of the flow of genetic information is from DNA to RNA and finally to protein [

110]. Currently, the main components of vaccines are usually proteins or peptides. However, if specific genes can be induced to be expressed in vivo, then DNA and RNA can equally be used as vaccines for therapeutic purposes. Compared with other types of vaccines, mRNA vaccines have shown many advantages. First, mRNA can use its nucleic acid sequence as a template to guide protein synthesis and ensure its proper folding and accurate transport within the cell, thus achieving a high degree of targeting [

111]. Secondly, the vaccine can also activate the innate and adaptive immune responses [

112]. In addition, mRNA vaccines have the advantages of good safety, low production cost, and easy preparation [

113]. A clinical study in 2023 demonstrated that RNA vaccines can increase T cells including hh in the blood of pancreatic cancer patients, and compared with those who did not receive the vaccine, the median recurrence-free survival period of those who received the vaccine was longer[

114].

mRNA tumor vaccines have demonstrated in the treatment of pancreatic cancer.It has unique theoretical advantages and initial clinical potential, but further clinical trials are still needed to support its practical application.

5.3. Immune cell therapy

CAR-T cell therapy has been successful in the treatment of a variety of hematological malignancies, and has shown initial results in the field of solid tumors[

115]. However, there are significant differences in clinical efficacy in patients with solid tumors, which are mainly attributed to the lack of tumor antigen specificity, complex tumor microenvironment, and the difficulty of CAR-T cells to effectively penetrate into solid tumors, etc., which makes CAR-T cell therapy face many challenges in the application of solid tumors [

116].

A basic study [

117] showed that CAR-T cells targeting Mesothelin (MSLN) encapsulated in a special gel and applied to a mouse model of adenocarcinoma that could not be completely removed by surgery and was temporarily palliative removed could effectively inhibit tumor recurrence and metastasis, and showed good safety and controllability. This finding opens up new possibilities for immune-cell therapy in patients with solid tumors after cytoreductive or curative surgery. A clinical study in 2021suggested that in a patient with advanced PC, anti-MSLN-7 × 19 CAR-T treatment resulted in almost complete tumor disappearance 240 days post-intravenous infusion.

T cell receptor gene engineered T cells (TCR-T) modify the T cell receptor to recognize membrane and intracellular proteins, and achieve precise recognition and attack against specific epitopes with high target specificity. In 2022, The Lancet published a case study report [

118] on the use of TCR-T therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, which attracted wide attention. In one patient in this study, the infusion of genetically engineered autologous T cells resulted in a significant reduction in the lung tumor and an objective response. Six months later, the volume of his metastatic lung lesions had decreased by 72%. In addition, the re-injected T cells could survive in the body for a long time, accounting for 2.4% of the total number of circulating T cells six months after infusion, and continued to exert immune effects.

Nevertheless, the efficacy of immunotherapy in the treatment of pancreatic cancer has not yet been determined, and more preclinical and clinical trial data are still needed to support whether immunotherapy is effective.

6. Progress of materials science in the treatment of pancreatic cancer

The advances in materials science have opened up a variety of innovative methods and technical approaches for cancer treatment, while exploring the pathogenesis and pathophysiological processes of pancreatic cancer.

Chen [

119] previously developed a spray-on bioreactive immunofibrin gel that could promote the transformation of the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment to a favorable anti-tumor direction and stimulate a systemic immune response, thereby inhibiting local recurrence and systemic progression. Calcium carbonate nanoparticles embedded in the gel matrix not only help to release therapeutic drugs in a controlled manner, but also adjust the acidic and inflammatory environment after surgical resection by removing H+, further enhancing the anti-tumor immune effect. In addition, aCD47 released locally from these nanoparticles blocked the "don't eat me" signal on the cancer cell surface, allowing macrophages to recognize and phagize the cancer cells. Because macrophages and dendritic cells enhance tumor-specific antigen presentation, CD47 blockade also promotes T-cell-mediated killing of cancer cells. In addition, to address clinical challenges such as chemotherapy resistance, researchers have explored a variety of strategies, including chemical modification of drugs or alteration of the route of administration, while a variety of novel drug carriers such as nanoparticles [

120] and liposomes [

121] have been developed. Although animal studies have shown that these innovative products show superior efficacy in cell tests and small animal tumor models, most of them are still in the laboratory research stage. In 2023, Wang designed and prepared a multi-component self-assembled nanobimetic drug with a clear drug composition to address the bottleneck issue of chemotherapeutic drugs' difficulty in penetrating the PCs matrix, which was used for the synergistic delivery of the chemotherapeutic drug camptothecin and the small molecule gas nitric oxide NO to realize the deep penetration of camptothecin in pancreatic cancer to enhance the chemotherapy effect of pancreatic cancer[

122].

In addition, researchers[

123] have developed an outer membrane vesicle (OMV) derived from Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 that binds to the neurobinding peptide NP41 and is loaded with the tropomyosin receptor kinase inhibitor larotrectinib (Lar@NP-OMV). It is used for targeted therapy of tumor-related nerves. By interfering with the neurotrophic factor /Trk signaling pathway, Lar@NP-OMV can effectively intervene in the nerve, thereby reducing neurite growth. In addition, OMV-mediated transformation of M2 tumor-associated macrophages to M1 tumor-associated macrophages further aggravated the damage to the nervous system and enhanced the neural intervention effect induced by Lar@NP-OMV, thereby inhibiting the nerve-triggered proliferation, migration and angiogenesis of pancreatic cancer cells. Using this strategy, Lar@NP-OMV significantly reduced gemcitabine-enhanced nerve penetration and neurite outgrowth in the tumor microenvironment and improved the efficacy of pancreatic cancer chemotherapy.

From the perspective of current research, the development of various new drug delivery systems has effectively improved the therapeutic effect of pancreatic cancer. However, many of them are still at the basic research stage at present. Improving the stability, targeting, safety and controllable drug release of the delivery systems will be the key issues that need to be urgently solved to promote their practical application in the future.

Table 1.

The characteristics of treatment methods for pancreatic cancer.

Table 1.

The characteristics of treatment methods for pancreatic cancer.

| Treatment methods |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| Surgical treatment |

|

|

| Open surgery |

Wide field of vision

Flexible operation |

Obvious pain

High infection rate |

| Laparoscopic surgery |

Minor trauma

Recover quickly

Low infection rate |

Operational restrictions

Long learning curve |

| Robotic surgery |

Least traumatic

Fastest recovery

Precise operation |

Dependence on equipment

Requires specialized training |

| Irreversible electroporation |

Precise ablation

Tissue preservation

Activate anti-tumor immunity |

Technical sophistication

Tumor residue and recurrence |

| Chemotherapy |

|

|

| Palliative chemotherapy |

Excellent symptom control

High treatment flexibility |

Cannot be cured completely

Side effects affect the quality of life

Long-term maintenance treatment |

| Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy |

Clearly extend the lifespan

Well-developed evidence-based plan

Reduced risk of recurrence |

Postoperative tolerance challenge

Highly specific toxicity |

| Preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

Improve the feasibility of the surgery

Reduce postoperative complications |

Insufficient standardization of the plan

Surgical difficulty may increase |

| Radiotherapy |

|

|

| Adjuvant radiotherapy |

Reduce local recurrence

Extend the disease-free survival period |

Poor postoperative tolerance |

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy |

Increase the rate of R0 resection

Reduce the risk of postoperative metastasis |

Disease progression during treatment |

| Targeted therapy |

|

|

| Targeting KRAS mutations |

Regarding specific molecular variations

Immune microenvironment regulation

Possible long-term remission |

Depend on specific biomarkers

High incidence of acquired resistance

High cost

Targeted related side effects |

| Targeting upstream of KRAS |

| Target KRAS downstream |

| Targeting other genes |

| Immunotherapy |

|

|

| Monoclonal antibody therapy |

Precise targeting and efficient killing

The potential for extending lifespan |

Limited efficacy of single drug treatment

Toxicity from combined treatment accumulates

Limited target audience |

| Tumor vaccine therapy |

Long-lasting immune memory

Safety is superior to traditional therapies |

Depend on biomarkers

Complex and costly to prepare

Uncertain therapeutic effect |

| Immune cell therapy |

Significantly improve survival benefits

Breaking through the immunosuppressive microenvironment |

Target-dependent

Immune-related toxicity

The preparation process is lengthy. |

| Progress of materials |

New research directions |

Remain at the research stage |

Discussion

In this review of pancreatic cancer treatment, we examined both traditional and emerging treatment approaches for pancreatic cancer(Table1). Surgery remains the most effective method for treating pancreatic cancer and is evolving towards minimally invasive and refined approaches. For instance, from the earliest open surgery to laparoscopic surgery and then to robotic surgery, clinicians are constantly comparing the risks and benefits of different methods. For unresectable pancreatic cancer, different radiotherapy and chemotherapy methods should be selected based on different conditions. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy are also usually used as adjunctive treatments for surgical treatment. The most mature approach to targeted therapy remains targeting Kras and its upstream and downstream pathways, but new targets are also emerging, such as TP53, SMAD4, and CDKN2A, and some clinical trials are underway. Monoclonal antibodies represented by PD1/PDL1 and cellular immunotherapy represented by CAR-T have shown efficacy in other tumors, while tumor vaccines respond to pancreatic tumors from a new perspective through immune action. In addition, the intersection of materials science and biomedicine offers new ideas for the treatment of pancreatic cancer, whether by enhancing the efficacy of drugs or reducing adverse reactions. In the future, the combination of various means, including the application of new materials, may bring new hope to patients with pancreatic cancer.

Conclusion

In summary, pancreatic cancer remains a disease with dismal outcomes and benefits from new treatments have been modest so far. Nevertheless, outcomes continue to improve, and exciting new treatment avenues have opened in the last few years. The treatment of pancreatic cancer requires comprehensive approaches and individualized considerations.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, it is not a systematic review and the quality of included literature was not formally evaluated. Second, some relevant studies may have been missed. Third, it does not cover all aspects of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of pancreatic cancer.

Ethics Approral and Consent to participate

This is a review of previously published studies. As such, it did not involve the direct recruitment of human participants or the collection of new primary data. Therefore, no new ethical approval was required for this review itself.

Consent for publication

This manuscript does not contain any new individual-level data, identifiable personal details, images, or case reports pertaining to specific individuals. All data presented and analyzed in this systematic review are aggregated findings derived exclusively from previously published studies.Therefore, no additional consent for publication is required for this synthesis.

Availability of data and Materials

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Fundings

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author’s Contributions

R.L. and F.J. and are responsible for collecting and writing the literature, while X.G.and T.Z. are in charge of reviewing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the researchers who conducted the original studies. Without them, this review would not have been possible. Meanwhile, we would like to express our gratitude to the teachers and students from the School of Medicine and the Department of Biomedical and Medical Engineering of Southeast University for their significant assistance in collecting the data and writing this article.

References

- Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. et al. Worldwide Burden of, Risk Factors for, and Trends in Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 160, 744–754 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 70, 7–30 (2020).

- Rahib, L. et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 74, 2913–2921 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Maisonneuve, P. Epidemiology and burden of pancreatic cancer. Presse Medicale Paris Fr. 1983 48, e113–e123 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K., Lu, H., Jiang, Y., Hung, T. T. & Stenzel, M. H. Safety of nanoparticles based on albumin–polymer conjugates as a carrier of nucleotides for pancreatic cancer therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 6, 6278–6287 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Fernández-del Castillo, C. et al. Evolution of the Whipple procedure at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Surgery 152, S56-63 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Gallitano, A., Fransen, H. & Martin, R. G. Carcinoma of the pancreas. Results of treatment. Cancer 22, 939–944 (1968).

- Winter, J. M. et al. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: A single-institution experience. J. Gastrointest. Surg. Off. J. Soc. Surg. Aliment. Tract 10, 1199–1210; discussion 1210-1211 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Wright, G. P., Koehler, T. J., Davis, A. T. & Chung, M. H. The drowning whipple: perioperative fluid balance and outcomes following pancreaticoduodenectomy. J. Surg. Oncol. 110, 407–411 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Hata, T. et al. Effect of Hospital Volume on Surgical Outcomes After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. 263, 664–672 (2016).

- Macedo, F. I. B. et al. The Impact of Surgeon Volume on Outcomes After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: a Meta-analysis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 21, 1723–1731 (2017). [CrossRef]

- He, Y.-G. et al. Association of a Modified Blumgart Anastomosis With the Incidence of Pancreatic Fistula and Operation Time After Laparoscopic Pancreatoduodenectomy: A Cohort Study. Front. Surg. 9, 931109 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ecker, B. L. et al. Risk Factors and Mitigation Strategies for Pancreatic Fistula After Distal Pancreatectomy: Analysis of 2026 Resections From the International, Multi-institutional Distal Pancreatectomy Study Group. Ann. Surg. 269, 143–149 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, L. S. et al. A risk-adjusted analysis of drain use in pancreaticoduodenectomy: Some is good, but more may not be better. Surgery 171, 1058–1066 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. et al. Prophylactic Intra-Peritoneal Drainage After Pancreatic Resection: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 11, 658829 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M. M. et al. Delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J. Surg. Res. 202, 380–388 (2016).

- Gagner, M. & Pomp, A. Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg. Endosc. 8, 408–410 (1994). [CrossRef]

- Gagner, M. & Palermo, M. Laparoscopic Whipple procedure: review of the literature. J. Hepatobiliary. Pancreat. Surg. 16, 726–730 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Croome, K. P. et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with major vascular resection: a comparison of laparoscopic versus open approaches. J. Gastrointest. Surg. Off. J. Soc. Surg. Aliment. Tract 19, 189–194; discussion 194 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, M. L. & Sclabas, G. M. Major venous resection during total laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB 13, 454–458 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Poves, I. et al. Comparison of Perioperative Outcomes Between Laparoscopic and Open Approach for Pancreatoduodenectomy: The PADULAP Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Surg. 268, 731–739 (2018).

- Jiang, Y.-L., Zhang, R.-C. & Zhou, Y.-C. Comparison of overall survival and perioperative outcomes of laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy and open pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 19, 781 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z., Jian, Z., Hou, B. & Jin, H. Surgical and Oncological Outcomes of Laparoscopic Versus Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy in Patients With Pancreatic Duct Adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 48, 861–867 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Chen, K. et al. Minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary disease: a comprehensive review of literature and meta-analysis of outcomes compared with open surgery. BMC Gastroenterol. 17, 120 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Bao, P. Q., Mazirka, P. O. & Watkins, K. T. Retrospective Comparison of Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Versus Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy for Periampullary Neoplasms. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 18, 682–689 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Kornaropoulos, M. et al. Total robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review of the literature. Surg. Endosc. 31, 4382–4392 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Copăescu, C. & Dumbravă, B. Is the Robotic Assisted Hybrid Approach Increasing the MIS efficiency for Pancreaticoduodenectomy? Chir. Buchar. Rom. 1990 118, 302–313 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Hanna, E. M. et al. Robotic hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: lessons learned and predictors for conversion. Int. J. Med. Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. MRCAS 9, 152–159 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Zureikat, A. H. et al. A Multi-institutional Comparison of Perioperative Outcomes of Robotic and Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann. Surg. 264, 640–649 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Napoli, N., Kauffmann, E. F., Vistoli, F., Amorese, G. & Boggi, U. State of the art of robotic pancreatoduodenectomy. Updat. Surg. 73, 873–880 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Boone, B. A. et al. Assessment of quality outcomes for robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy: identification of the learning curve. JAMA Surg. 150, 416–422 (2015).

- Rubinsky, B., Onik, G. & Mikus, P. Irreversible electroporation: a new ablation modality--clinical implications. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 6, 37–48 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. C. G., McFarland, K., Ellis, S. & Velanovich, V. Irreversible electroporation therapy in the management of locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 215, 361–369 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Maor, E., Ivorra, A., Leor, J. & Rubinsky, B. The effect of irreversible electroporation on blood vessels. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 6, 307–312 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Charalambous, P. et al. The efficacy and safety of the open approach irreversible electroporation in the treatment of pancreatic cancer: A systematic review. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Surg. Oncol. Br. Assoc. Surg. Oncol. 46, 1565–1572 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, K. et al. Irreversible Electroporation for Nonthermal Tumor Ablation in Patients with Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: Initial Clinical Experience in Japan. Intern. Med. Tokyo Jpn. 57, 3225–3231 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Flak, R. V. et al. Treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer with irreversible electroporation - a Danish single center study of safety and feasibility. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 54, 252–258 (2019). [CrossRef]

- He, C., Huang, X., Zhang, Y., Lin, X. & Li, S. T-cell activation and immune memory enhancement induced by irreversible electroporation in pancreatic cancer. Clin. Transl. Med. 10, e39 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. C. et al. Irreversible Electroporation and Beta-Glucan-Induced Trained Innate Immunity for Treatment of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Phase II Study. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 240, 351–361 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. et al. Irreversible electroporation reverses resistance to immune checkpoint blockade in pancreatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 10, 899 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Conroy, T. et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 1817–1825 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Von Hoff, D. D. et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 1691–1703 (2013).

- Golan, T. et al. Maintenance Olaparib for Germline BRCA-Mutated Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 317–327 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Carrato, A. et al. Phase I/II trial of sequential treatment of nab-paclitaxel in combination with gemcitabine followed by modified FOLFOX chemotherapy in patients with untreated metastatic exocrine pancreatic cancer: Phase I results. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 1990 139, 51–58 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Neoptolemos, J. P. et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 389, 1011–1024 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Conroy, T. et al. FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine as Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 2395–2406 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Ma, T. et al. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. JNCCN 19, (2021).

- Kolbeinsson, H. M., Chandana, S., Wright, G. P. & Chung, M. Pancreatic Cancer: A Review of Current Treatment and Novel Therapies. J. Investig. Surg. Off. J. Acad. Surg. Res. 36, 2129884 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, D. et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 11–20 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Sauer, R. et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 1731–1740 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Miyasaka, Y. et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy with Gemcitabine Plus Nab-Paclitaxel for Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer Potentially Improves Survival and Facilitates Surgery. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 26, 1528–1534 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.-I. et al. Phase I Study of Nab-Paclitaxel plus Gemcitabine as Neoadjuvant Therapy for Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer. Anticancer Res. 37, 853–858 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Reni, M. et al. A randomised phase 2 trial of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine with or without capecitabine and cisplatin in locally advanced or borderline resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 1990 102, 95–102 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J. E. et al. Total Neoadjuvant Therapy With FOLFIRINOX Followed by Individualized Chemoradiotherapy for Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 4, 963–969 (2018).

- Ferrone, C. R. et al. Radiological and surgical implications of neoadjuvant treatment with FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann. Surg. 261, 12–17 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Katz, M. H. G. et al. Preoperative Modified FOLFIRINOX Treatment Followed by Capecitabine-Based Chemoradiation for Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Trial A021101. JAMA Surg. 151, e161137 (2016).

- Barbour, A. P. et al. The AGITG GAP Study: A Phase II Study of Perioperative Gemcitabine and Nab-Paclitaxel for Resectable Pancreas Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 27, 2506–2515 (2020). [CrossRef]

- OʼReilly, E. M. et al. A single-arm, nonrandomized phase II trial of neoadjuvant gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in patients with resectable pancreas adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. 260, 142–148 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Ielpo, B. et al. Preoperative treatment with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is a safe and effective chemotherapy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Surg. Oncol. Br. Assoc. Surg. Oncol. 42, 1394–1400 (2016). [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S. et al. A pilot phase II multicenter study of nab-paclitaxel (Nab-P) and gemcitabine (G) as preoperative therapy for potentially resectable pancreatic cancer (PC). J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 4038–4038 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Wei, A. C. et al. Perioperative Gemcitabine + Erlotinib Plus Pancreaticoduodenectomy for Resectable Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: ACOSOG Z5041 (Alliance) Phase II Trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 26, 4489–4497 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Sohal, D. et al. SWOG S1505: Results of perioperative chemotherapy (peri-op CTx) with mfolfirinox versus gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (Gem/nabP) for resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA). J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 4504–4504 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, W. et al. Perioperative chemotherapy is associated with a survival advantage in early stage adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. Surgery 160, 714–724 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Versteijne, E. et al. Meta-analysis comparing upfront surgery with neoadjuvant treatment in patients with resectable or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Surg. 105, 946–958 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Kalser, M. H. & Ellenberg, S. S. Pancreatic cancer. Adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection. Arch. Surg. Chic. Ill 1960 120, 899–903 (1985).

- Neoptolemos, J. P. et al. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 1200–1210 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Palta, M. et al. Radiation Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer: Executive Summary of an ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 9, 322–332 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J. P. et al. Phase II trial of preoperative radiation therapy and chemotherapy for patients with localized, resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 16, 317–323 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Araujo, R. L. C. et al. Does neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic head adenocarcinoma increase postoperative morbidity? A systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. J. Surg. Oncol. 121, 881–892 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J. E. et al. Total Neoadjuvant Therapy With FOLFIRINOX in Combination With Losartan Followed by Chemoradiotherapy for Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 5, 1020–1027 (2019).

- Versteijne, E. et al. Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy Versus Immediate Surgery for Resectable and Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: Results of the Dutch Randomized Phase III PREOPANC Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 38, 1763–1773 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Versteijne, E. et al. Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy Versus Upfront Surgery for Resectable and Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: Long-Term Results of the Dutch Randomized PREOPANC Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 40, 1220–1230 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Cloyd, J. M. et al. Impact of hypofractionated and standard fractionated chemoradiation before pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer 122, 2671–2679 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Perri, G. et al. The Sequential Radiographic Effects of Preoperative Chemotherapy and (Chemo)Radiation on Tumor Anatomy in Patients with Localized Pancreatic Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 27, 3939–3947 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Chang, D. K. et al. Margin clearance and outcome in resected pancreatic cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 27, 2855–2862 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Talamonti, M. S. et al. A multi-institutional phase II trial of preoperative full-dose gemcitabine and concurrent radiation for patients with potentially resectable pancreatic carcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 13, 150–158 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. B. et al. Preoperative gemcitabine-based chemoradiation for patients with resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 26, 3496–3502 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Artinyan, A., Anaya, D. A., McKenzie, S., Ellenhorn, J. D. I. & Kim, J. Neoadjuvant therapy is associated with improved survival in resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer 117, 2044–2049 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Cloyd, J. M. et al. Chemotherapy Versus Chemoradiation as Preoperative Therapy for Resectable Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Propensity Score Adjusted Analysis. Pancreas 48, 216–222 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V. K. et al. Preoperative chemoradiation for marginally resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J. Gastrointest. Surg. Off. J. Soc. Surg. Aliment. Tract 5, 27–35 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Nagakawa, Y. et al. Clinical Impact of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Chemoradiotherapy in Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: Analysis of 884 Patients at Facilities Specializing in Pancreatic Surgery. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 26, 1629–1636 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science 321, 1801–1806 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Biankin, A. V. et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature 491, 399–405 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Ostrem, J. M., Peters, U., Sos, M. L., Wells, J. A. & Shokat, K. M. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature 503, 548–551 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Strickler, J. H. et al. Sotorasib in KRAS p.G12C-Mutated Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 33–43 (2023).

- Awad, M. M. et al. Acquired Resistance to KRASG12C Inhibition in Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 2382–2393 (2021). 2393.

- Holderfield, M. et al. Concurrent inhibition of oncogenic and wild-type RAS-GTP for cancer therapy. Nature 629, 919–926 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wasko, U. N. et al. Tumour-selective activity of RAS-GTP inhibition in pancreatic cancer. Nature 629, 927–936 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. et al. Pan-KRAS inhibitor disables oncogenic signalling and tumour growth. Nature 619, 160–166 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, G., Stickler, S. & Rath, B. Targeting of SOS1: from SOS1 Activators to Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras. Curr. Pharm. Des. 29, 1741–1746 (2023).

- Voldborg, B. R., Damstrup, L., Spang-Thomsen, M. & Poulsen, H. S. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and EGFR mutations, function and possible role in clinical trials. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 8, 1197–1206 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Yin, H., Tang, Q., Xia, H. & Bi, F. Targeting RAF dimers in RAS mutant tumors: From biology to clinic. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 14, 1895–1923 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Klomp, J. A. et al. Defining the KRAS- and ERK-dependent transcriptome in KRAS-mutant cancers. Science 384, eadk0775 (2024).

- Chen, Y. et al. The ERK inhibitor GDC-0994 selectively inhibits growth of BRAF mutant cancer cells. Transl. Oncol. 45, 101991 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R. J. et al. First-in-Class ERK1/2 Inhibitor Ulixertinib (BVD-523) in Patients with MAPK Mutant Advanced Solid Tumors: Results of a Phase I Dose-Escalation and Expansion Study. Cancer Discov. 8, 184–195 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Hwang, R. F., Gordon, E. M., Anderson, W. F. & Parekh, D. Gene therapy for primary and metastatic pancreatic cancer with intraperitoneal retroviral vector bearing the wild-type p53 gene. Surgery 124, 143–150; discussion 150-151 (1998).

- Xiong, W. et al. Smad4 Deficiency Promotes Pancreatic Cancer Immunogenicity by Activating the Cancer-Autonomous DNA-Sensing Signaling Axis. Adv. Sci. Weinh. Baden-Wurtt. Ger. 9, e2103029 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. et al. PTPN14 interacts with and negatively regulates the oncogenic function of YAP. Oncogene 32, 1266–1273 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Sinn, M. et al. CONKO-005: Adjuvant Chemotherapy With Gemcitabine Plus Erlotinib Versus Gemcitabine Alone in Patients After R0 Resection of Pancreatic Cancer: A Multicenter Randomized Phase III Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 35, 3330–3337 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Brahmer, J. R. et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 2455–2465 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Feng, M. et al. PD-1/PD-L1 and immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 407, 57–65 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Bayne, L. J. et al. Tumor-derived granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor regulates myeloid inflammation and T cell immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 21, 822–835 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Michelakos, T. et al. Tumor Microenvironment Immune Response in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Patients Treated With Neoadjuvant Therapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 113, 182–191 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Liu, N. et al. Advances in Cancer Vaccine Research. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 9, 5999–6023 (2023).

- Heumann, T. et al. A platform trial of neoadjuvant and adjuvant antitumor vaccination alone or in combination with PD-1 antagonist and CD137 agonist antibodies in patients with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Nat. Commun. 14, 3650 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Worbs, T., Hammerschmidt, S. I. & Förster, R. Dendritic cell migration in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 30–48 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, E. DC-based cancer vaccines. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1195–1203 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, A. et al. Prophylactic dendritic cell vaccination controls pancreatic cancer growth in a mouse model. Cytotherapy 22, 6–15 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Crick, F. Central dogma of molecular biology. Nature 227, 561–563 (1970). [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Zhang, G., Tang, T.-Y., Gao, X. & Liang, T.-B. Personalized pancreatic cancer therapy: from the perspective of mRNA vaccine. Mil. Med. Res. 9, 53 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. et al. mRNA vaccine: a potential therapeutic strategy. Mol. Cancer 20, 33 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Fang, E. et al. Advances in COVID-19 mRNA vaccine development. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 7, 94 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Rojas, L. A. et al. Personalized RNA neoantigen vaccines stimulate T cells in pancreatic cancer. Nature 618, 144–150 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Marofi, F. et al. CAR T cells in solid tumors: challenges and opportunities. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 12, 81 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Maalej, K. M. et al. CAR-cell therapy in the era of solid tumor treatment: current challenges and emerging therapeutic advances. Mol. Cancer 22, 20 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Uslu, U. et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells as adjuvant therapy for unresectable adenocarcinoma. Sci. Adv. 9, eade2526 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Leidner, R. et al. Neoantigen T-Cell Receptor Gene Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 2112–2119 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. et al. In situ sprayed bioresponsive immunotherapeutic gel for post-surgical cancer treatment. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 89–97 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. et al. Targeting Xkr8 via nanoparticle-mediated in situ co-delivery of siRNA and chemotherapy drugs for cancer immunochemotherapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 193–204 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. et al. Dual-functional melanin-based nanoliposomes for combined chemotherapy and photothermal therapy of pancreatic cancer. RSC Adv. 9, 3012–3019 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. et al. Ultrasound-Triggered Piezocatalysis for Selectively Controlled NO Gas and Chemodrug Release to Enhance Drug Penetration in Pancreatic Cancer. ACS Nano 17, 3557–3573 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Qin, J. et al. Targeted intervention in nerve–cancer crosstalk enhances pancreatic cancer chemotherapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 20, 311–324 (2025). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).